Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

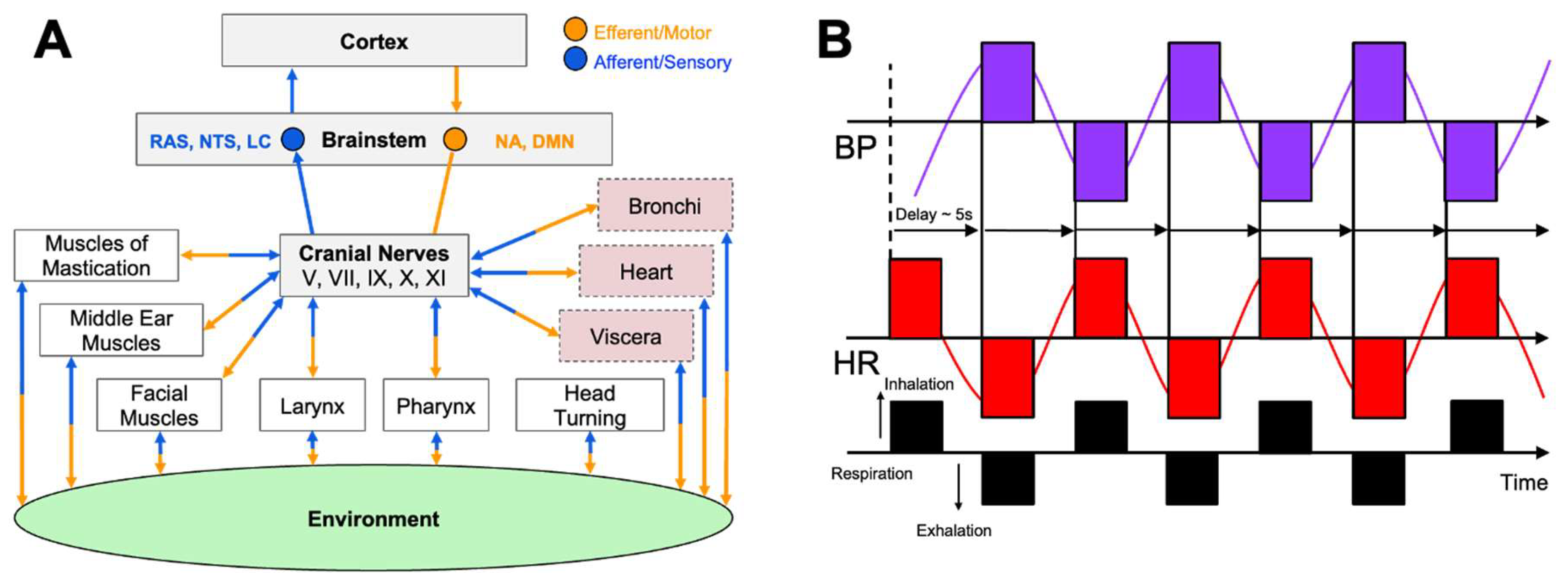

Vagal Physiology and Autonomic Regulation

Vagal Tone, Cognition, and Emotional Resilience

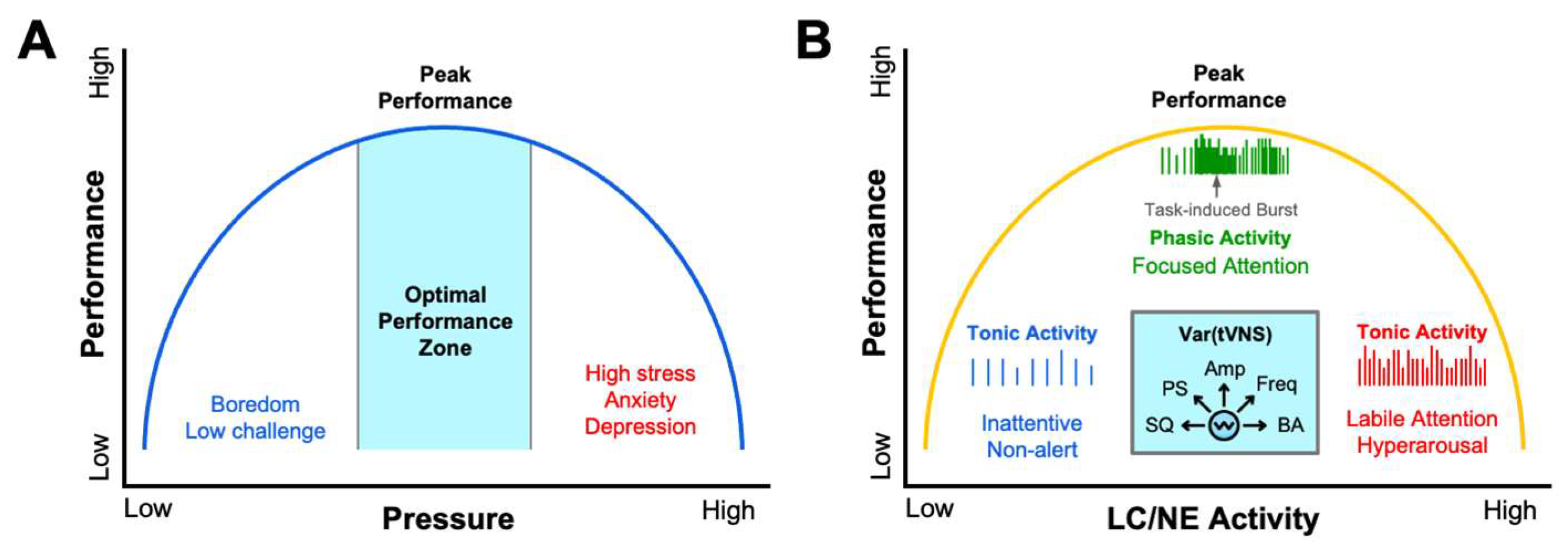

Regulation of Psychophysiological Arousal for Functional Performance

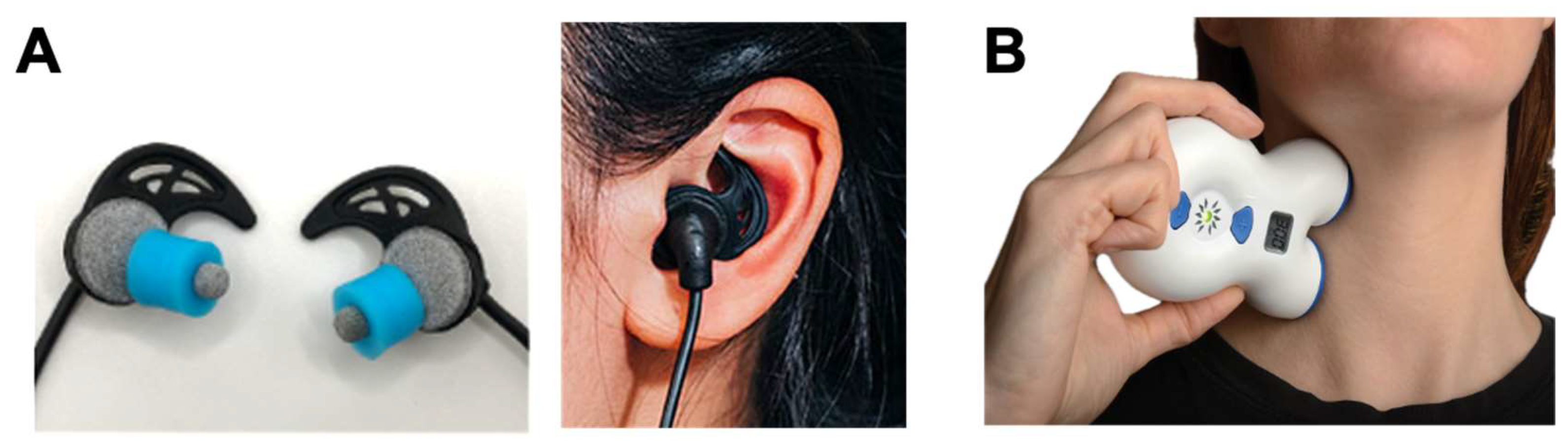

Vagus Nerve Stimulation: From Clinical Neuromodulation to Applied Ergogenics

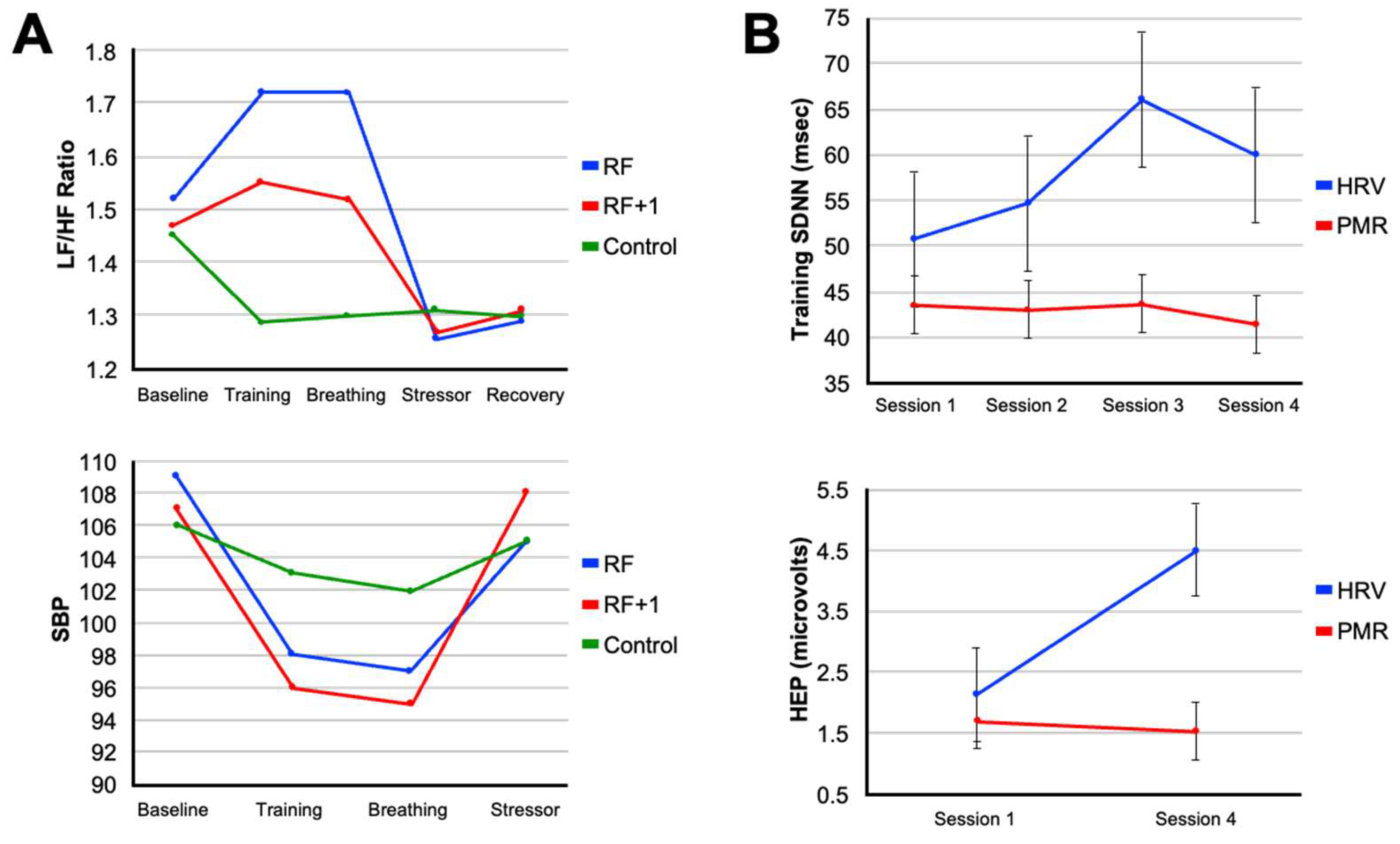

Autonomic Training Strategies: Rhythmic Breathing, HRV biofeedback, and Environmental Exposure

Conclusion and Future Directions

Acknowledgements

Disclosures

References

- H.-R. Berthoud and W. L. Neuhuber, "Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system," (in en), Autonomic Neuroscience, vol. 85, no. 1-3, pp. 1-17, 12/2000 2000. [CrossRef]

- A. Zagon, "Does the vagus nerve mediate the sixth sense?," Trends in Neurosciences, vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 671-673, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao et al., "A multidimensional coding architecture of the vagal interoceptive system," (in en), Nature, vol. 603, no. 7903, pp. 878-884, 2022-03-31 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Gooden, "Mechanism of the human diving response," (in eng), Integr Physiol Behav Sci, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 6-16, Jan-Mar 1994. [CrossRef]

- R. K. Khurana, S. Watabiki, J. R. Hebel, R. Toro, and E. Nelson, "Cold face test in the assessment of trigeminal-brainstem-vagal function in humans," (in eng), Ann Neurol, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 144-9, Feb 1980. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Andersen, "The reflex nature of the physiological adjustments to diving and their afferent pathway," (in eng), Acta Physiol Scand, vol. 58, pp. 263-73, Jun-Jul 1963. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Krygier, J. A. J. Heathers, S. Shahrestani, M. Abbott, J. J. Gross, and A. H. Kemp, "Mindfulness meditation, well-being, and heart rate variability: A preliminary investigation into the impact of intensive Vipassana meditation," (in en), International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 89, no. 3, pp. 305-313, 09/2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- K. A. McLaughlin, L. Rith-Najarian, M. A. Dirks, and M. A. Sheridan, "Low Vagal Tone Magnifies the Association Between Psychosocial Stress Exposure and Internalizing Psychopathology in Adolescents," (in en), Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, vol. 44, no. 2, pp. 314-328, 2015-03-04 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Laborde, E. Mosley, and A. Mertgen, "Vagal Tank Theory: The Three Rs of Cardiac Vagal Control Functioning – Resting, Reactivity, and Recovery," (in en), Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 458, 2018-7-10 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Çalι, A. V. Özden, and İ. Ceylan, "Effects of a single session of noninvasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation on sports performance in elite athletes: an open-label randomized controlled trial," (in eng), Expert Rev Med Devices, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 231-237, Mar 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. I. L. Jacobs, J. M. Riphagen, C. M. Razat, S. Wiese, and A. T. Sack, "Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation boosts associative memory in older individuals," (in en), Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 36, no. 5, pp. 1860-1867, 05/2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Murphy et al., "The Effects of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Functional Connectivity Within Semantic and Hippocampal Networks in Mild Cognitive Impairment," (in en), Neurotherapeutics, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 419-430, 03/2023 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Urbin, C. W. Lafe, T. W. Simpson, G. F. Wittenberg, B. Chandrasekaran, and D. J. Weber, "Electrical stimulation of the external ear acutely activates noradrenergic mechanisms in humans," (in eng), Brain Stimul, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 990-1001, Jul-Aug 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. Sharon, F. Fahoum, and Y. Nir, "Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Humans Induces Pupil Dilation and Attenuates Alpha Oscillations," (in eng), The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 320-330, 2021-01-13 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Frangos, J. Ellrich, and B. R. Komisaruk, "Non-invasive Access to the Vagus Nerve Central Projections via Electrical Stimulation of the External Ear: fMRI Evidence in Humans," (in eng), Brain Stimul, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 624-36, May-Jun 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Czura and K. J. Tracey, "Autonomic neural regulation of immunity," (in eng), J Intern Med, vol. 257, no. 2, pp. 156-66, Feb 2005. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Pavlov and K. J. Tracey, "The vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex—linking immunity and metabolism," (in en), Nature Reviews Endocrinology, vol. 8, no. 12, pp. 743-754, 12/2012 2012. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Pavlov and K. J. Tracey, "Bioelectronic medicine: Preclinical insights and clinical advances," (in eng), Neuron, vol. 110, no. 21, pp. 3627-3644, Nov 2 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Ackland et al., "Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation and exercise capacity in healthy volunteers: a randomized trial," (in en), European Heart Journal, vol. 46, no. 17, pp. 1634-1644, 2025-05-02 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Porges, "The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system," (in en), International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 123-146, 10/2001 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Porges, "The polyvagal theory: New insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system," (in en), Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, vol. 76, no. 4 suppl 2, pp. S86-S90, 02/2009 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. M. Yerkes and J. D. Dodson, "The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation," Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, vol. 18, no. 5, pp. 459-482, 1908. [CrossRef]

- G. Aston-Jones, J. Rajkowski, and J. Cohen, "Role of locus coeruleus in attention and behavioral flexibility," Biological Psychiatry, vol. 46, no. 9, pp. 1309-1320, 1999/11/01/ 1999. [CrossRef]

- G. Aston-Jones and J. D. Cohen, "An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance," (in eng), Annu Rev Neurosci, vol. 28, pp. 403-50, 2005. [CrossRef]

- G. G. Berntson, J. T. Cacioppo, and K. S. Quigley, "Respiratory sinus arrhythmia: autonomic origins, physiological mechanisms, and psychophysiological implications," (in eng), Psychophysiology, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 183-96, Mar 1993. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Butt, A. Albusoda, A. D. Farmer, and Q. Aziz, "The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation," (in en), Journal of Anatomy, vol. 236, no. 4, pp. 588-611, 04/2020 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Carnevali and A. Sgoifo, "Vagal modulation of resting heart rate in rats: the role of stress, psychosocial factors, and physical exercise," (in en), Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 5, 2014-03-24 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Sloan et al., "Effect of mental stress throughout the day on cardiac autonomic control," (in en), Biological Psychology, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 89-99, 3/1994 1994. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Fisher, J. Song, and P. D. Soyster, "Toward a systems-based approach to understanding the role of the sympathetic nervous system in depression," (in en), World Psychiatry, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 295-296, 06/2021 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. J. S. Gerritsen and G. P. H. Band, "Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity," (in en), Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 12, p. 397, 2018-10-9 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Malik, "Heart Rate Variability: Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation, and Clinical Use: Task Force of The European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society for Pacing and Electrophysiology," (in en), Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 151-181, 04/1996 1996. [CrossRef]

- E. Vaschillo, P. Lehrer, N. Rishe, and M. Konstantinov, "Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback as a Method for Assessing Baroreflex Function: A Preliminary Study of Resonance in the Cardiovascular System," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 2002 2002.

- P. M. Lehrer et al., "Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Increases Baroreflex Gain and Peak Expiratory Flow," (in en), Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 796-805, 09/2003 2003. [CrossRef]

- P. M. Lehrer and R. Gevirtz, "Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work?," (in en), Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 5, 2014-07-21 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Kinoshita, S. Nagata, R. Baba, T. Kohmoto, and S. Iwagaki, "Cold-Water Face Immersion Per Se Elicits Cardiac Parasympathetic Activity," (in en), Circulation Journal, vol. 70, no. 6, pp. 773-776, 2006 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Hurwitz and J. J. Furedy, "The human dive reflex: an experimental, topographical and physiological analysis," (in eng), Physiol Behav, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 287-94, 1986. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Ackermann, M. Raab, S. Backschat, D. J. C. Smith, F. Javelle, and S. Laborde, "The diving response and cardiac vagal activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis," (in en), Psychophysiology, vol. 60, no. 3, p. e14183, 03/2023 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Schipke and M. Pelzer, "Effect of immersion, submersion, and scuba diving on heart rate variability," (in eng), Br J Sports Med, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 174-80, Jun 2001. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Hansen, B. H. Johnsen, and J. F. Thayer, "Vagal influence on working memory and attention," (in en), International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 263-274, 6/2003 2003. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Thayer, S. S. Yamamoto, and J. F. Brosschot, "The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors," (in en), International Journal of Cardiology, vol. 141, no. 2, pp. 122-131, 05/2010 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Laborde, E. Mosley, and J. F. Thayer, "Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiological Research – Recommendations for Experiment Planning, Data Analysis, and Data Reporting," (in en), Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 08, 2017-02-20 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Wei, Y. Chen, X. Chen, C. Baeken, and G.-R. Wu, "Cardiac vagal activity changes moderated the association of cognitive and cerebral hemodynamic variations in the prefrontal cortex," (in en), NeuroImage, vol. 297, p. 120725, 08/2024 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Forte and M. Casagrande, "The intricate brain–heart connection: The relationship between heart rate variability and cognitive functioning," Neuroscience, vol. 565, pp. 369-376, 2025/01/26/ 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Arakaki et al., "The connection between heart rate variability (HRV), neurological health, and cognition: A literature review," (in en), Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 17, p. 1055445, 2023-3-1 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Goessl, J. E. Curtiss, and S. G. Hofmann, "The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: a meta-analysis," (in en), Psychological Medicine, vol. 47, no. 15, pp. 2578-2586, 11/2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Wells, T. Outhred, J. A. J. Heathers, D. S. Quintana, and A. H. Kemp, "Matter Over Mind: A Randomised-Controlled Trial of Single-Session Biofeedback Training on Performance Anxiety and Heart Rate Variability in Musicians," (in en), PLoS ONE, vol. 7, no. 10, p. e46597, 2012-10-4 2012. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Segerstrom and L. S. Nes, "Heart rate variability reflects self-regulatory strength, effort, and fatigue," (in eng), Psychol Sci, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 275-81, Mar 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Karavidas et al., "Preliminary Results of an Open Label Study of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for the Treatment of Major Depression," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 19-30, 2007-3-26 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Porges, "The polyvagal perspective," (in en), Biological Psychology, vol. 74, no. 2, pp. 116-143, 2/2007 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. Mosley, S. Laborde, and E. Kavanagh, "The contribution of coping related variables and cardiac vagal activity on the performance of a dart throwing task under pressure," (in en), Physiology & Behavior, vol. 179, pp. 116-125, 10/2017 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. M. De Souza et al., "Vagal Flexibility during Exercise: Impact of Training, Stress, Anthropometric Measures, and Gender," (in en), Rehabilitation Research and Practice, vol. 2020, pp. 1-8, 2020-10-05 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Langdeau, H. Turcotte, P. Desagné, J. Jobin, and L. P. Boulet, "Influence of sympatho-vagal balance on airway responsiveness in athletes," (in eng), Eur J Appl Physiol, vol. 83, no. 4 -5, pp. 370-5, Nov 2000. [CrossRef]

- F. C. M. Geisler, T. Kubiak, K. Siewert, and H. Weber, "Cardiac vagal tone is associated with social engagement and self-regulation," (in en), Biological Psychology, vol. 93, no. 2, pp. 279-286, 5/2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. McCraty, "New Frontiers in Heart Rate Variability and Social Coherence Research: Techniques, Technologies, and Implications for Improving Group Dynamics and Outcomes," (in en), Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 5, p. 267, 2017-10-12 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Gullett, Z. Zajkowska, A. Walsh, R. Harper, and V. Mondelli, "Heart rate variability (HRV) as a way to understand associations between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and affective states: A critical review of the literature," (in en), International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 192, pp. 35-42, 10/2023 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Ortega and C. J. K. Wang, "Pre-performance Physiological State: Heart Rate Variability as a Predictor of Shooting Performance," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 75-85, 3/2018 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Plews, P. B. Laursen, J. Stanley, A. E. Kilding, and M. Buchheit, "Training Adaptation and Heart Rate Variability in Elite Endurance Athletes: Opening the Door to Effective Monitoring," (in en), Sports Medicine, vol. 43, no. 9, pp. 773-781, 9/2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Kiviniemi, A. J. Hautala, H. Kinnunen, and M. P. Tulppo, "Endurance training guided individually by daily heart rate variability measurements," (in en), European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 101, no. 6, pp. 743-751, 2007-10-10 2007. [CrossRef]

- V. Vesterinen et al., "Individual Endurance Training Prescription with Heart Rate Variability," (in en), Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 1347-1354, 07/2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Bellenger, J. T. Fuller, R. L. Thomson, K. Davison, E. Y. Robertson, and J. D. Buckley, "Monitoring Athletic Training Status Through Autonomic Heart Rate Regulation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis," (in en), Sports Medicine, vol. 46, no. 10, pp. 1461-1486, 10/2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Meeusen et al., "Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine," (in eng), Med Sci Sports Exerc, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 186-205, Jan 2013. [CrossRef]

- Y. Le Meur et al., "Evidence of Parasympathetic Hyperactivity in Functionally Overreached Athletes," (in en), Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 45, no. 11, pp. 2061-2071, 11/2013 2013. [CrossRef]

- Van Diest, K. Verstappen, A. E. Aubert, D. Widjaja, D. Vansteenwegen, and E. Vlemincx, "Inhalation/Exhalation Ratio Modulates the Effect of Slow Breathing on Heart Rate Variability and Relaxation," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 39, no. 3-4, pp. 171-180, 12/2014 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Afify, "Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercise on Cardiovascular Parameters Following Noise Exposure in Pre Hypertensive Adults," Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 79-86, %04/%15 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Shaffer and Z. M. Meehan, "A Practical Guide to Resonance Frequency Assessment for Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback," (in en), Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 14, p. 570400, 2020-10-8 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Handforth et al., "Vagus nerve stimulation therapy for partial-onset seizures: a randomized active-control trial," (in eng), Neurology, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 48-55, Jul 1998. [CrossRef]

- T. Kraus, K. Hösl, O. Kiess, A. Schanze, J. Kornhuber, and C. Forster, "BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation," (in en), Journal of Neural Transmission, vol. 114, no. 11, pp. 1485-1493, 11/2007 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Tyler et al., "Transdermal neuromodulation of noradrenergic activity suppresses psychophysiological and biochemical stress responses in humans," (in eng), Sci Rep, vol. 5, p. 13865, Sep 10 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Tyler, S. Wyckoff, T. Hearn, and N. Hool, "The Safety and Efficacy of Transdermal Auricular Vagal Nerve Stimulation Earbud Electrodes for Modulating Autonomic Arousal, Attention, Sensory Gating, and Cortical Brain Plasticity in Humans," bioRxiv, p. 732529, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Croft, Z. M. LaMacchia, J. F. Alderete, A. Maestas, K. Nguyen, and R. B. O’Hara, "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Efficacy, Applications, and Challenges in Mood Disorders and Autonomic Regulation—A Narrative Review," Military Medicine, p. usaf063, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Tyler, "Auricular bioelectronic devices for health, medicine, and human-computer interfaces," (in en), Frontiers in Electronics, vol. 6, p. 1503425, 2025-2-6 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Kelly, C. Breathnach, K. J. Tracey, and S. C. Donnelly, "Manipulation of the inflammatory reflex as a therapeutic strategy," Cell Reports Medicine, vol. 3, no. 7, p. 100696, 2022/07/19/ 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Kim et al., "Safety of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS): a systematic review and meta-analysis," Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 22055, 2022/12/21 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Y. Yap, C. Keatch, E. Lambert, W. Woods, P. R. Stoddart, and T. Kameneva, "Critical Review of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation: Challenges for Translation to Clinical Practice," (in en), Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 14, p. 284, 2020-4-28 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Yuan and S. D. Silberstein, "Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part I," (in en), Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 71-78, 01/2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. D. Silberstein et al., "Non–Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation for the ACute Treatment of Cluster Headache: Findings From the Randomized, Double-Blind, Sham-Controlled ACT1 Study," (in en), Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, vol. 56, no. 8, pp. 1317-1332, 09/2016 2016. [CrossRef]

- C.-H. Liu et al., "Neural networks and the anti-inflammatory effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation in depression," (in eng), Journal of Neuroinflammation, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 54, 2020-02-12 2020. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R. C. Calloway, V. P. Karuzis, N. B. Pandža, P. O'Rourke, and S. E. Kuchinsky, "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Strengthens Semantic Representations of Foreign Language Tone Words during Initial Stages of Learning," Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 127-152, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Olsen, E. Solis, L. K. McIntire, and C. N. Hatcher-Solis, "Vagus nerve stimulation: mechanisms and factors involved in memory enhancement," (in English), Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Review vol. 17, 2023-June-29 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Szeska, K. Klepzig, A. O. Hamm, and M. Weymar, "Ready for translation: non-invasive auricular vagus nerve stimulation inhibits psychophysiological indices of stimulus-specific fear and facilitates responding to repeated exposure in phobic individuals," Translational Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 135, 2025/04/09 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Trifilio et al., "Impact of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on healthy cognitive and brain aging," (in English), Frontiers in Neuroscience, Review vol. 17, 2023-July-28 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Bretherton, L. Atkinson, A. Murray, J. Clancy, S. Deuchars, and J. Deuchars, "Effects of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation in individuals aged 55 years or above: potential benefits of daily stimulation," (in eng), Aging, vol. 11, no. 14, pp. 4836-4857, 2019-07-30 2019. [CrossRef]

- Machetanz, L. Berelidze, R. Guggenberger, and A. Gharabaghi, "Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation and heart rate variability: Analysis of parameters and targets," Autonomic Neuroscience, vol. 236, p. 102894, 2021/12/01/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- Machetanz, L. Berelidze, R. Guggenberger, and A. Gharabaghi, "Brain–Heart Interaction During Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation," (in English), Frontiers in Neuroscience, Original Research vol. 15, 2021-March-15 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gurel et al., "Transcutaneous cervical vagal nerve stimulation reduces sympathetic responses to stress in posttraumatic stress disorder: A double-blind, randomized, sham controlled trial," (in eng), Neurobiol Stress, vol. 13, p. 100264, Nov 2020. [CrossRef]

- Moazzami et al., "Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation modulates stress-induced plasma ghrelin levels: A double-blind, randomized, sham-controlled trial," Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 342, pp. 85-90, 2023/12/01/ 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Sommer, R. Fischer, U. Borges, S. Laborde, S. Achtzehn, and R. Liepelt, "The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) on cognitive control in multitasking," Neuropsychologia, vol. 187, p. 108614, 2023/08/13/ 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Jongkees, M. A. Immink, A. Finisguerra, and L. S. Colzato, "Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (tVNS) Enhances Response Selection During Sequential Action," (in English), Frontiers in Psychology, Original Research vol. 9, 2018-July-06 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, X. Lu, and L. Hu, "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Facilitates Cortical Arousal and Alertness," International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 20, no. 2. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Rufener, U. Geyer, K. Janitzky, H. J. Heinze, and T. Zaehle, "Modulating auditory selective attention by non-invasive brain stimulation: Differential effects of transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation and transcranial random noise stimulation," (in eng), Eur J Neurosci, vol. 48, no. 6, pp. 2301-2309, Sep 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Miyatsu et al., "Transcutaneous cervical vagus nerve stimulation enhances second-language vocabulary acquisition while simultaneously mitigating fatigue and promoting focus," Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 17177, 2024/07/26 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen et al., "Enhancing Motor Sequence Learning via Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (taVNS): An EEG Study," (in en), IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 1285-1296, 3/2024 2024. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen et al., "Effects of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation (tVNS) on Action Planning: A Behavioural and EEG Study," IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, vol. 30, pp. 1675-1683, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-B. Sun et al., "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Improves Spatial Working Memory in Healthy Young Adults," (in English), Frontiers in Neuroscience, Original Research vol. 15, 2021-December-23 2021. [CrossRef]

- U. Borges, L. Knops, S. Laborde, S. Klatt, and M. Raab, "Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation May Enhance Only Specific Aspects of the Core Executive Functions. A Randomized Crossover Trial," (in English), Frontiers in Neuroscience, Original Research vol. 14, 2020-May-25 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jigo, J. B. Carmel, Q. Wang, and C. Rodenkirch, "Transcutaneous cervical vagus nerve stimulation improves sensory performance in humans: a randomized controlled crossover pilot study," Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 3975, 2024/02/17 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Faller, J. Cummings, S. Saproo, and P. Sajda, "Regulation of arousal via online neurofeedback improves human performance in a demanding sensory-motor task," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 116, no. 13, pp. 6482-6490, 2019, doi: doi:10.1073/pnas.1817207116.

- B. Pandža, I. Phillips, V. P. Karuzis, P. O'Rourke, and S. E. Kuchinsky, "Neurostimulation and Pupillometry: New Directions for Learning and Research in Applied Linguistics," Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, vol. 40, pp. 56-77, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mao et al., "Effects of Sub-threshold Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Cingulate Cortex and Insula Resting-state Functional Connectivity," (in English), Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Original Research vol. 16, 2022-April-14 2022. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. A. Johns, N. B. Pandža, R. C. Calloway, V. P. Karuzis, and S. E. Kuchinsky, "Three Hundred Hertz Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (taVNS) Impacts Pupil Size Non-Linearly as a Function of Intensity," (in eng), Psychophysiology, vol. 62, no. 2, p. e70011, Feb 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. J. Tyler et al., "Neurotechnology for enhancing human operation of robotic and semi-autonomous systems," (in English), Frontiers in Robotics and AI, Review vol. Volume 12 - 2025, 2025-May-23 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Hatik, M. Arslan, Ö. Demirbilek, and A. V. Özden, "The effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on cycling ergometry and recovery in healthy young individuals," Brain and Behavior, vol. 13, no. 12, p. e3332, 2023/12/01 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yoshida et al., "Effects of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation on Hemodynamics and Autonomic Function During Exercise Stress Tests in Healthy Volunteers," Circulation Reports, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 315-322, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Gourine and G. L. Ackland, "Cardiac Vagus and Exercise," Physiology, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 71-80, 2019/01/01 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Laborde, E. Mosley, and L. Ueberholz, "Enhancing cardiac vagal activity: Factors of interest for sport psychology," in Progress in Brain Research, vol. 240, S. Marcora and M. Sarkar Eds.: Elsevier, 2018, pp. 71-92.

- T. D. Noakes, A. St Clair Gibson, and E. V. Lambert, "From catastrophe to complexity: a novel model of integrative central neural regulation of effort and fatigue during exercise in humans: summary and conclusions," British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 39, no. 2, p. 120, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, "The flow experience and its significance for human psychology," in Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness, M. Csikszentmihalyi and I. S. Csikszentmihalyi Eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, pp. 15-35.

- M. Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row New York, 1990.

- D. J. Harris, A. K. L., V. S. J., and M. R. and Wilson, "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between flow states and performance," International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 693-721, 2023/12/31 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Peifer, A. Schulz, H. Schächinger, N. Baumann, and C. H. Antoni, "The relation of flow-experience and physiological arousal under stress — Can u shape it?," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 53, pp. 62-69, 2014/07/01/ 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. van der Linden, M. Tops, and A. B. Bakker, "The Neuroscience of the Flow State: Involvement of the Locus Coeruleus Norepinephrine System," (in English), Frontiers in Psychology, Mini Review vol. Volume 12 - 2021, 2021-April-14 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Colzato, G. Wolters, and C. Peifer, "Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) modulates flow experience," (in eng), Exp Brain Res, vol. 236, no. 1, pp. 253-257, Jan 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Anderson, H. S. J., and C. J. and Mallett, "Investigating the Optimal Psychological State for Peak Performance in Australian Elite Athletes," Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 318-333, 2014/07/03 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Steffen, T. Austin, A. DeBarros, and T. Brown, "The Impact of Resonance Frequency Breathing on Measures of Heart Rate Variability, Blood Pressure, and Mood," (in en), Frontiers in Public Health, vol. 5, p. 222, 2017-08-25 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Garcia et al., "Optimization of respiratory-gated auricular vagus afferent nerve stimulation for the modulation of blood pressure in hypertension," (in English), Frontiers in Neuroscience, Original Research vol. Volume 16 - 2022, 2022-December-09 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Szulczewski, M. D'Agostini, and I. Van Diest, "Expiratory-gated transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) does not further augment heart rate variability during slow breathing at 0.1 Hz," Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 323-333, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Szulczewski, "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Combined With Slow Breathing: Speculations on Potential Applications and Technical Considerations," Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 380-394, 2022/04/01/ 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Garcia et al., "Respiratory-gated auricular vagal afferent nerve stimulation (RAVANS) modulates brain response to stress in major depression," Journal of Psychiatric Research, vol. 142, pp. 188-197, 2021/10/01/ 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Sclocco et al., "The influence of respiration on brainstem and cardiovagal response to auricular vagus nerve stimulation: A multimodal ultrahigh-field (7T) fMRI study," Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 911-921, 2019. [CrossRef]

- O. Dergacheva, K. J. Griffioen, R. A. Neff, and D. Mendelowitz, "Respiratory modulation of premotor cardiac vagal neurons in the brainstem," Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, vol. 174, no. 1, pp. 102-110, 2010/11/30/ 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Chaitanya, A. Datta, B. Bhandari, and V. K. Sharma, "Effect of Resonance Breathing on Heart Rate Variability and Cognitive Functions in Young Adults: A Randomised Controlled Study," (in en), Cureus, 2022-2-13 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Jiménez Morgan and J. A. Molina Mora, "Effect of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback on Sport Performance, a Systematic Review," (in eng), Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 235-245, Sep 2017. [CrossRef]

- G. Henriques, S. Keffer, C. Abrahamson, and S. Jeanne Horst, "Exploring the Effectiveness of a Computer-Based Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Program in Reducing Anxiety in College Students," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 101-112, 6/2011 2011. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. K. Kim, and A. Wachholtz, "The benefit of heart rate variability biofeedback and relaxation training in reducing trait anxiety," (in eng), Hanguk Simni Hakhoe Chi Kongang, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 391-408, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Paciorek and L. Skora, "Vagus Nerve Stimulation as a Gateway to Interoception," (in English), Frontiers in Psychology, Perspective vol. Volume 11 - 2020, 2020-July-29 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Villani, M. Tsakiris, and R. T. Azevedo, "Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation improves interoceptive accuracy," Neuropsychologia, vol. 134, p. 107201, 2019/11/01/ 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lagos, E. Vaschillo, B. Vaschillo, P. Lehrer, M. Bates, and R. Pandina, "Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback as a Strategy for Dealing with Competitive Anxiety: A Case Study," (in en), 2008 2008.

- Taublieb, "Mind Gurus " in Enhanced, Produced by Taublieb Films and Jigsaw Productions for ESPN Films, 2018. https://vimeo.com/281118327.

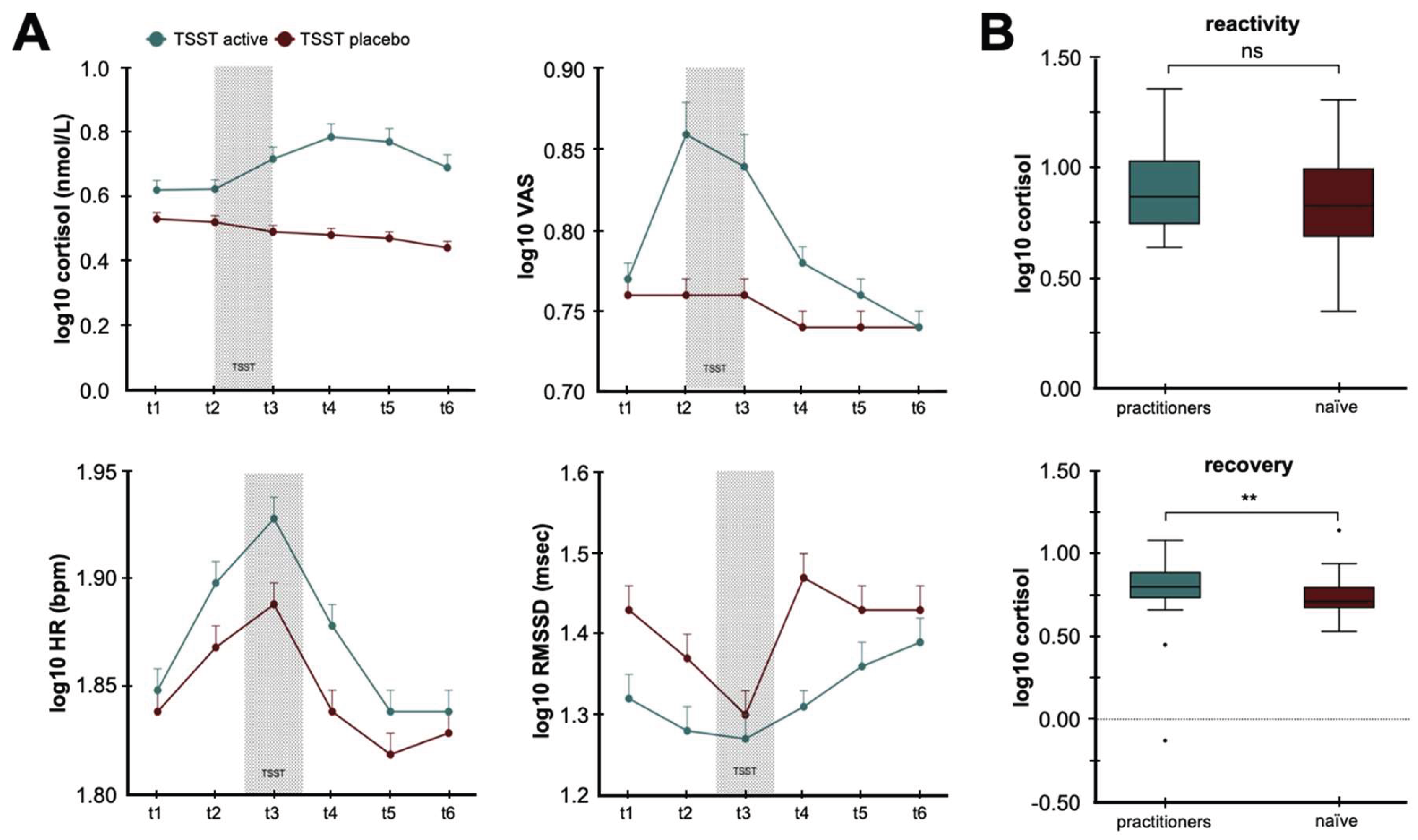

- Gamaiunova, P.-Y. Brandt, G. Bondolfi, and M. Kliegel, "Exploration of psychological mechanisms of the reduced stress response in long-term meditation practitioners," (in en), Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 104, pp. 143-151, 06/2019 2019. [CrossRef]

- Cansler, J. Heidrich, A. Whiting, D. Tran, P. Hall, and W. J. Tyler, "Influence of CrossFit and Deep End Fitness training on mental health and coping in athletes," (in English), Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, Brief Research Report vol. Volume 5 - 2023, 2023-October-02 2023. [CrossRef]

- A.-L. Lumma, B. E. Kok, and T. Singer, "Is meditation always relaxing? Investigating heart rate, heart rate variability, experienced effort and likeability during training of three types of meditation," (in en), International Journal of Psychophysiology, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 38-45, 07/2015 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Van Der Zwan, W. De Vente, A. C. Huizink, S. M. Bögels, and E. I. De Bruin, "Physical Activity, Mindfulness Meditation, or Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for Stress Reduction: A Randomized Controlled Trial," (in en), Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 257-268, 12/2015 2015. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).