Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mean—Second Order Tssalis Entropy—Variance Model to Porfolio Optimization

2.2. Case Studies

3. Results and Discussions

Limitations

- -

- Incorporating dynamic, forward-looking estimators for return and volatility using machine learning or regime-switching models;

- -

- Extending the entropy component to higher-order measures or adaptive entropy estimators that reflect changing market structures;

- -

- Embedding behavioral preferences and adaptive risk-aversion mechanisms into the objective function;

- -

- Exploring integration with decentralized finance (DeFi) instruments, NFT-backed assets, or hybrid portfolios combining digital and traditional securities;

- -

- Testing the model over longer time horizons or across multiple regimes to assess robustness under varying market conditions.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7, 77–91.

- Hamza, F.; Janssen, J. (1996). Linear approach for solving large-scale portfolio optimization problems in a lognormal market. Proceedings of the 6th AFIR, Nuremberg, Germany.

- Markowitz, H. (1991). Foundations of portfolio optimizations. The Journal of Finance, 2, 469–471.

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, G. (2009). Information entropy-based fuzzy optimization model of electricity purchasing portfolio. IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PES '09), 1–6.

- Konno, H.; Yamazaki, H. (1991). A mean absolute deviation portfolio optimization model and its applications to Tokyo stock market. Management Science, 37, 519–531. [CrossRef]

- Speranza, M. G. (1993). Linear programming models for portfolio optimization. Finance, 14, 107–123. https://iris.unibs.it/handle/11379/4732 . [CrossRef]

- King, A. J.; Jensen, D. L. (1992). Linear-quadratic efficient frontiers for portfolio optimization model. Applied Stochastic Models and Data Analysis, 8, 195–207.

- King, A. J. (1993). Asymmetric risk measures and tracking models for portfolio optimization under uncertainty. Annals of Operations Research, 45, 165–178. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, H.; Todd, P.; Xu, G.; Yamane, Y. (1993). Computation of mean–semi-variance efficient sets by the critical line algorithm. Annals of Operations Research, 45, 307–318.

- Yoshimoto, A. (1996). The mean-variance approach to portfolio optimization subject to transaction costs. Journal of the Operations Research Society of Japan, 39(1), 99–117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y. (2021). A novel approach for determining OWA operator weights based on maximum entropy and linear programming. Information Sciences, 580, 620–635.

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423.

- Yager, R. R. (1995). Measures of entropy and fuzziness related to aggregation operators. Information Sciences, 82, 147–166. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Parkan, C. (2005). A minimax disparity model for portfolio selection. European Journal of Operational Research, 163(1), 115–131.

- Philippatos, G. C.; Wilson, C. J. (1972). Entropy, market risk, and the selection of efficient portfolios. Applied Economics, 4, 209–220.

- Simonelli, M. R. (2005). Indeterminacy in portfolio selection. European Journal of Operational Research, 163, 170–176.

- Zhou, R. X.; Cai, R.; Tong, G. Q. (2013). Applications of entropy in finance: A review. Entropy, 15, 4909–4931. https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/15/11/4909 . [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; He, S.; Li, X. (2008). A maximum entropy model for large-scale portfolio optimization. International Conference on Risk Management & Engineering Management (ICRMEM '08), 610–615.

- Dedu, S.; Șerban, F.; Tudorache, A. (2014). Quantitative risk management techniques using interval analysis, with applications to finance and insurance. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods, 9, 1–15.

- Dedu S., Fulga C. (2011). Value-at-Risk estimation comparative approach with applications to optimization problems. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 45(4), 5–20.

- Liu, P.; Li, X. (2023). A novel approach to fuzzy multi-objective programming with Pareto optimality. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 467, 45–60.

- He, X.; Jiang, H. (2020). A Maximum Entropy Model for Large-Scale Portfolio Optimization. Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Financial Engineering, 45–52.

- Ke, J.; Zhang, C. (2008). Study on the optimization of portfolio based on entropy theory and mean-variance model. IEEE International Conference on Service Operations and Logistics, and Informatics (SOLI 2008), 2668–2672. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240643459.

- Sheraz M., Dedu S. (2020). Bitcoin Cash: Stochastic models of fat-tail returns and risk modeling. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 54(3), 43–58.

- Lutgens, F.; Schotman, P. (2010). Robust portfolio optimisation with multiple experts. Review of Finance, 14, 343–383. https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/14/2/343/1569756 . [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. R.; Lee, W. Y. (2011). Portfolio rebalancing model using multiple criteria. European Journal of Operational Research, 209, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Zopounidis, C.; Doumpos, M. (2020). Multi-criteria decision aid in financial decision making: Methodologies and literature review. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 27(1–2), 1–24. [CrossRef]

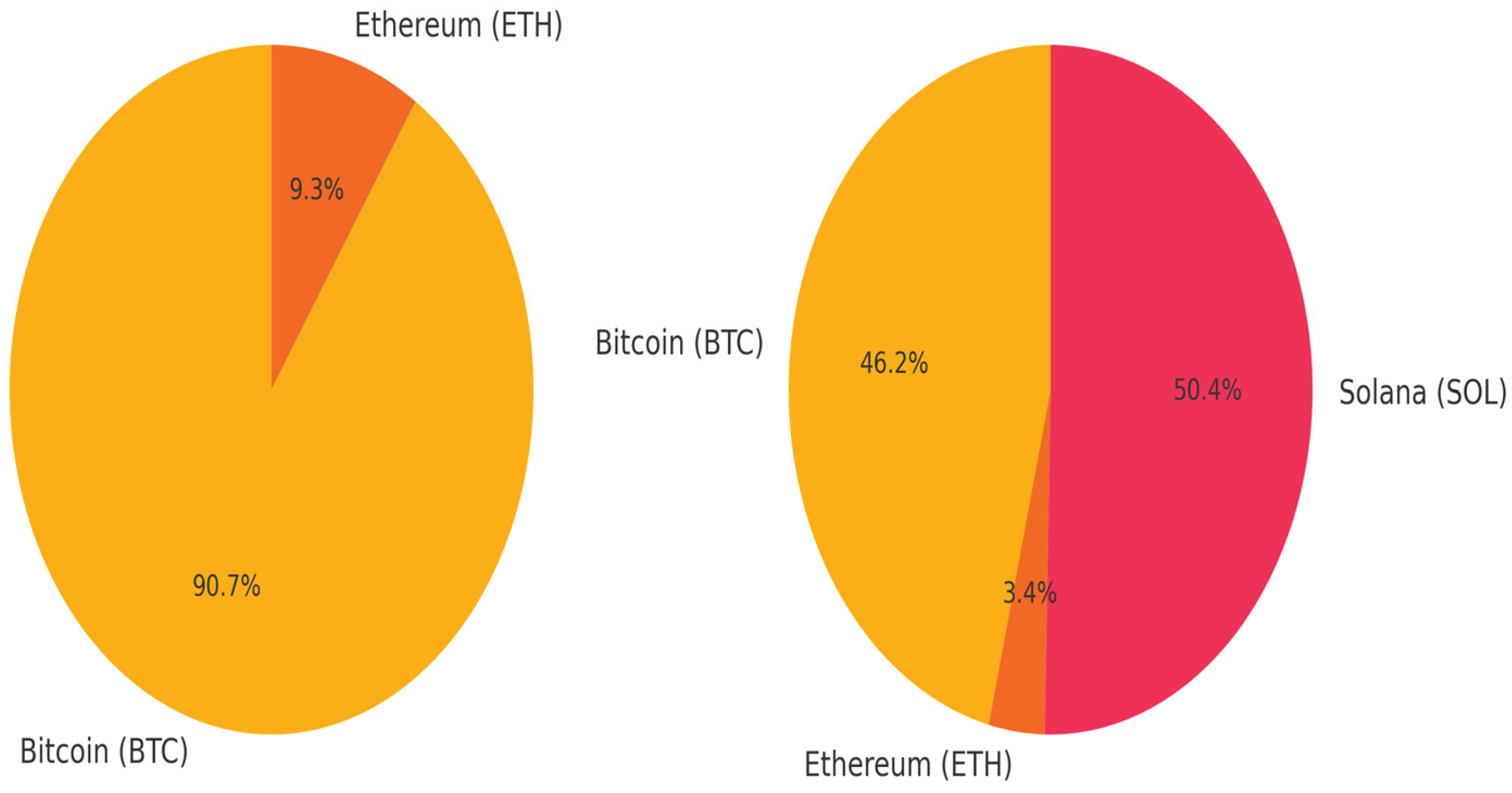

| Asset | μ (Return) | σ² (Variance) | xᵢ (Weight) |

| Bitcoin (BTC) | 0.0565 | 0.033 | 0.9074 |

| Ethereum (ETH) | 0.0133 | 0.775 | 0.0926 |

| Bitcoin (BTC) | 0.0565 | 0.033 | 0.462 |

| Ethereum (ETH) | 0.0133 | 0.775 | 0.0344 |

| Solana (SOL) | 0.0755 | 0.105 | 0.5036 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).