1. Introduction

Portfolio optimization is a foundational problem in modern finance, focused on the allocation of an investor’s wealth across a selection of assets in order to balance expected returns against risk exposure. The classical solution is encapsulated in the mean–variance framework proposed by Markowitz [

1], which relies on historical returns, along with the variances and covariances of asset returns, to construct efficient portfolios based on first- and second-order moments. Typically, the objective is to maximize expected return for a given level of risk or, conversely, to minimize risk for a target level of return.

In response to the limitations of this framework—most notably its reliance on normally distributed returns and its sensitivity to estimation errors—numerous alternative models have been proposed. These include refinements of the risk measure itself. For example, Speranza [

2] introduced a linear programming model based on semi-absolute deviation, focusing on downside fluctuations, while semi variance-based approaches were advanced by King [

3] and King and Jensen [

4] to more accurately capture downside risk. Other researchers have explored substituting variance with alternative risk metrics, such as Value-at-Risk (VaR). Alexander and Baptista [

5] examined a mean–VaR portfolio selection model, highlighting its conceptual differences from the mean–variance framework and its consistency with mean–CVaR results [

6]. Hamza and Janssen [

7] expanded the scope of optimization by incorporating transaction costs using an asymmetric risk function and separable programming.Earlier studies by Pogue [

8], Rudd and Rosenberg [

9], and Yoshimoto [

10] addressed real-world frictions—such as taxes, short selling, and transaction costs—through nonlinear cost functions and other advanced optimization techniques. Despite these advances, empirical evidence shows that even sophisticated models often do not outperform naive diversification strategies such as the equally weighted 1/N portfolio, especially under conditions of estimation uncertainty and limited data availability [

11,

12].

Within this broader context, diversification remains a key determinant of portfolio performance. In recent years, entropy has emerged as a powerful tool for enhancing and measuring diversification. As a quantitative measure of uncertainty or disorder, entropy offers a flexible, distribution-free alternative to variance as a risk proxy. Shannon’s seminal work in information theory [

13] laid the mathematical foundation for entropy as a measure of information content. This concept has since been adapted to financial modeling by Yager [

14], Wang and Parkan [

15], and Philippatos and Wilson [

16,

17], who introduced entropy-based methods for decision-making and portfolio optimization. These studies highlight entropy’s capacity to capture risk dispersion and diversification effects that may be overlooked by variance-based metrics, particularly in markets characterized by heavy tails, asymmetric distributions, or noisy data.

Empirical applications have further reinforced entropy’s relevance. Simonelli [

18] showed that entropy-based models outperform traditional deviation-based approaches in capturing portfolio uncertainty. Jiang et al. [

19] and Ke and Zhang [

20] extended these insights to high-dimensional asset universes, incorporating entropy into robust optimization frameworks. Zhou [

21] emphasized the growing importance of entropy in finance, noting its applications in areas ranging from energy procurement to digital asset management. In the cryptocurrency domain, recent studies have applied entropy-based techniques to manage risk under extreme volatility [

22]. For instance, Rodriguez-Rodriguez and Miramontes [

23] used Shannon entropy in an econophysical framework to evaluate diversification in crypto portfolios.

Building on this extensive body of research, the present paper introduces three entropy-enhanced models for portfolio optimization: the maximum Shannon entropy model, the Tsallis entropy model with nonextensivity parameter q = 2, and the maximum weighted Shannon entropy model. These approaches extend the mean–variance paradigm by embedding nonlinear, information-theoretic measures of uncertainty into the allocation process. Analytical solutions are derived using the method of Lagrange multipliers, ensuring mathematical rigor and interpretability.

To assess their practical effectiveness, we implement a series of empirical case studies involving four major cryptocurrencies—Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Solana (SOL), and Binance Coin (BNB)—using weekly return data from January to March 2025. The findings demonstrate that entropy-based optimization promotes improved diversification, reduces concentration risk, and yields more robust allocations—particularly within high-volatility environments such as the cryptocurrency market.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the theoretical formulation of the proposed entropy-based portfolio models.

Section 3 presents and interprets the numerical results.

Section 4 concludes with a summary of findings and future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamentals of Portfolio Entropy

Entropy in Portfolio Theory and Information Science

Entropy is a foundational concept that quantifies the degree of randomness, uncertainty, or disorder within a system. Initially developed in thermodynamics and later formalized in information theory by Shannon [

13], entropy has since evolved into a central quantitative tool with widespread applications, including in economics and finance [

24]. In the context of dynamical systems, zero entropy indicates a perfectly deterministic state, while higher entropy values reflect increasing uncertainty and structural complexity [

12].

The theoretical underpinnings of entropy have been shaped by several landmark contributions. Boltzmann was the first to relate entropy to molecular disorder, providing the physical interpretation still used today. Shannon then defined entropy in the information-theoretic sense—as the expected information content of a message—thereby establishing a direct connection between statistical uncertainty and informational efficiency. These ideas were extended by scholars such as Wiener, Khinchin, Faddeev, Rényi, Tsallis, Guiasu, and Onicescu [

25], who developed mathematical generalizations of entropy applicable across diverse scientific domains, including finance.

A major theoretical advancement came from Jaynes [

26], who introduced the principle of maximum entropy. This principle asserts that, under conditions of incomplete information, the probability distribution that maximizes entropy is the most objective and unbiased estimate, avoiding the introduction of artificial assumptions. Jaynes's formulation has since become a cornerstone of modern probabilistic inference and decision-making under uncertainty.

In contemporary portfolio management, entropy has gained increasing recognition as a robust and flexible alternative to variance-based risk metrics. Unlike variance, which relies on second-order moments and normality assumptions, entropy provides a more general and nonlinear measure of dispersion and uncertainty, particularly useful when return distributions are skewed, heavy-tailed, or incomplete.

Empirical and theoretical contributions to this field underscore the versatility of entropy. Yager [

14] applied the maximum entropy principle in multi-criteria decision frameworks, illustrating its capacity to guide choices under uncertainty. Wang and Parkan [

15] introduced entropy weighting into performance evaluation via a minimax disparity model. Philippatos and Wilson [

16,

17] were pioneers in proposing entropy as a substitute for variance in portfolio theory, especially under non-normal return distributions.

Recent developments further confirm entropy's utility in large-scale and high-volatility settings. Jiang et al. [

19] developed entropy-constrained portfolio optimization strategies tailored for high-dimensional investment spaces. Ke and Zhang [

20] extended the classical mean–variance model by integrating Shannon entropy as an additional constraint. Elsheikh and Egret [

27] combined entropy with higher-order return moments to better capture distributional asymmetries, while Li et al. [

22] proposed a multi-objective portfolio framework that incorporates entropy-based dispersion control.

Moreover, Zhou et al. [

28] demonstrated that portfolios optimized using entropy criteria exhibit enhanced balance and resilience compared to those built on variance alone, highlighting entropy's potential as a cornerstone of modern risk management in uncertain and turbulent financial environments

Collectively, these developments reinforce entropy's role as a generalizable, mathematically grounded methodology for quantifying uncertainty, enhancing diversification, and guiding portfolio construction.

Empirical Interpretation of Portfolio Entropy

In the context of portfolio optimization, entropy offers a quantitative measure of both diversification and uncertainty in capital allocation. Consider a portfolio composed of n assets, where each asset iii is assigned a non-negative weight ≥ 0 and the weights collectively satisfy the constraint. The resulting weight vector can therefore be interpreted as a discrete probability distribution over the investment universe. Under this probabilistic interpretation, the Shannon entropy of the portfolio is given by: . This function quantifies the degree of balance or dispersion in the allocation:

- When the portfolio is entirely concentrated in a single asset (e.g., , all others zero),then entropy reaches its minimum value, H(x) = 0, indicating no diversification.

- When capital is equally distributed across all assets (i.e. ), entropy attain its maximum value, H(x) = ln n , reflecting maximal diversification.

As such, Shannon entropy as a proxy for portfolio robustness. It penalizes concentrated positions while favoring balanced allocations, thereby promoting structural resilience—particularly important in high-volatility environments such as cryptocurrency markets, where return distributions deviate from normality and informational completeness is limited.

Axiomatic Approach to Portfolio Entropy

Shannon entropy is uniquely defined by a set of three fundamental axioms, which can be naturally adapted to the context of portfolio theory:

Continuity: Small variations in portfolio weights result in small changes in entropy. This ensures that the entropy function behaves smoothly and does not produce abrupt discontinuities in response to marginal rebalancing.

Symmetry: The entropy of a portfolio is invariant under any reordering of assets. In other words, asset labels do not influence the entropy value—only their relative weights matter.

Additivity under Composition: For two sub-portfolios A and B, selected with respective probabilities , the total entropy of the combined portfolio satisfies: .This axiom, sometimes referred to as "recursivity" or "compositional additivity," formalizes how diversification across mixed strategies aggregates into total portfolio uncertainty.

Together, these axioms uniquely lead to the Shannon entropy formula: Alternative entropy measures like Tsallis and Rényi do not satisfy all these axioms, especially the third (additivity). As a result, Shannon entropy remains the only entropy function that preserves full axiomatic coherence under classical assumptions of diversification logic. This property justifies its central role in both information theory and portfolio optimization.

2.2. Maximum entropy models to portfolio optimization

2.2.A. Maximum Shannon Entropy Portfolio Model

The maximum entropy principle, initially proposed by Jaynes (1957), suggests that among all possible distributions consistent with known constraints, the one that maximizes entropy represents the least biased estimate. In portfolio selection, this principle translates into finding the allocation that maximizes diversification, as measured by entropy, while satisfying risk-related constraints.

Let the portfolio be represented by the weight vector with ≥ 0 and . The Shannon entropy of the portfolio is: To reflect the investor’s risk tolerance, we introduce a variance constraint expressed using the covariance matrix .

The optimization problem becomes:

Maximize

subject to

≥ 0

Using the method of Lagrange multipliers (Zheng et al. [

27]), the Lagrangian is:

Using the Lagrange multipliers method, we obtain:

(, , …, xₙ , λ, γ)

Taking the partial derivative with respect to we obtain the first-order condition:

or

=

i= 1, 2,…n or

This expression highlights how the optimal allocation depends nonlinearly on the weighted sum of covariances between each asset and the rest of the portfolio.

Solving this system under the constraints yields the entropy-maximizing portfolio. The result is a distribution-free solution that balances maximum diversification with controlled risk exposure, making it highly suitable for volatile and information-sparse markets such as cryptocurrencies.

2.2.B. Maximum Second-Order Entropy Portfolio Model (Tsallis, q = 2)

The Tsallis entropy is a generalized entropy measure introduced by Constantino Tsallis as an extension of the classical Shannon entropy to accommodate non-extensive systems. In financial optimization, Tsallis entropy provides a nonlinear diversification criterion that penalizes concentration more aggressively than the Shannon formulation. This feature is particularly useful in markets characterized by heavy tails, strong correlations, and nonlinear dependencies, such as cryptocurrency assets.

The general form of the Tsallis entropy is given by: For q = 2 the expression simplifies to: (x) = This function reaches its maximum when the allocation is uniform (i.e., = 1/n) and declines as weights become more concentrated. The Tsallis entropy is concave for 0 < q<2 and quasi-concave for q > 1, making it suitable for optimization.

The portfolio optimization problem under Tsallis entropy is formulated as:

Maximize

(x) =

subject to

≥ 0

Using the method of Lagrange multipliers the Lagrangian is:

(, , …, xₙ , λ, γ)+

Taking the partial derivative with respect to we obtain the first-order condition:

or

i= 1,2,…n

This formulation shows that each optimal weight xix_ixi depends nonlinearly on its covariance-weighted interaction with other assets. The Tsallis entropy model imposes a stronger penalty on dominant weights than Shannon entropy, encouraging more balanced allocations—especially useful in markets with tail risk, asymmetry, or hidden correlations, such as cryptocurrencies.

2.2.C. Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy Portfolio Model

The classical Shannon entropy assumes equal informational significance for each component of the distribution. However, in financial contexts, different assets may carry distinct levels of importance due to factors such as investor preferences, market influence, ESG scores (a standardized ratings that assess a company’s performance across environmental, social, and governance dimensions). These metrics are increasingly integrated into investment decisions, as they reflect long-term sustainability, ethical responsibility, and risk exposure related to non-financial factors, or liquidity. To capture this asymmetry, Guiasu introduced a weighted entropy formulation [

15], allowing each asset to be assigned a weight

hat reflects its informational or strategic relevance. The weighted Shannon entropy is defined as:

The optimization problem becomes:

Maximize

subject to

≥ 0

Using the method of Lagrange multipliers, the Lagrangian is::

(, , …, xₙ , λ, γ)

Taking the partial derivative with respect to we obtain the first-order condition:

or

=i= 1, 2,…n or

This nonlinear expression indicates that optimal allocations are influenced not only by the covariance structure, but also by the informational relevance wkw_kwk. Assets with higher weights are penalized more heavily for concentrated exposure, thereby encouraging capital reallocation toward structurally less dominant components.

In our empirical analysis, we consider the case for all i, representing uniform importance. However, this model is highly flexible and can integrate data-driven or subjective prioritization strategies. As such, it provides a rigorous yet customizable framework for entropy-based optimization, particularly suitable when investor confidence or strategic relevance varies across assets.

2.3. Case Studies

To assess the practical performance of the proposed entropy-based portfolio models, we conduct a comparative analysis using real-world market data. The portfolio includes four major cryptocurrencies—Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Solana (SOL), and Binance Coin (BNB)—selected for their market capitalization, liquidity, and strategic relevance.

Following recent findings that support entropy-based approaches under high volatility [

28,

29], we evaluate three models: Maximum Shannon Entropy, Maximum Tsallis Entropy (q = 2), and Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy.

The dataset spans from January 5 to March 29, 2025, and consists of 13 weekly observations for each asset. This time frame was selected deliberately as a stress-test window, reflecting heightened volatility in the cryptocurrency market and offering a realistic scenario for assessing the structural stability of entropy-based models.

Methodology Summary

Extraction of weekly return data from public sources (CoinMarketCap, Binance)

Computation of the expected return vector and covariance matrix

Implementation in MATLAB using fmincon nonlinear solver

Imposition of a fixed portfolio variance constraint: = 0.0015.

The variance constraint was set to 0.0015 to reflect a conservative risk tolerance aligned with typical levels of volatility observed in balanced cryptocurrency portfolios

Each model yields:

Optimal asset weights

Entropy value specific to the model

Confirmed variance

Visualized diversification patterns

This empirical setup enables a structural comparison of how different entropy formulations influence portfolio composition under identical constraints, offering insights into their robustness and suitability for high-volatility assets.

2.3.1. Maximum Shannon Entropy Model

This model determines the most diversified portfolio allocation under a variance constraint. The problem is formulated as:

Maximize

subject to

≥ 0

Results:

| Asset |

Weight (%) |

| BTC |

24.13 |

| ETH |

6.68 |

| SOL |

23.59 |

| BNB |

24.60 |

Interpretation: The allocation is near-uniform, as expected from the Shannon criterion. ETH receives a lower weight due to its higher volatility. This model promotes structural balance and is robust under volatility, offering diversified exposure regardless of expected returns.

2.3.2. Maximum Tsallis Entropy Model

This model incorporates non-extensivity via the Tsallis entropy with q = 2

The problem is formulated as:

Maximize (x) =

subject to

≥ 0

Results:

| Asset |

Weight (%) |

| BTC |

18.77 |

| ETH |

19.22 |

| SOL |

33.42 |

| BNB |

28.59 |

Interpretation: Compared to Shannon, the Tsallis model yields a more asymmetric allocation, favoring assets like SOL and BNB. The higher sensitivity to concentration leads to reduced exposure in BTC and ETH. This model is ideal for markets with nonlinear dependencies and tail risks.

2.3.3. Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy Model

This model integrates asset-specific informational weights:

Weights used:

| Asset |

|

| BTC |

0.30 |

| ETH |

0.25 |

| SOL |

0.20 |

| BNB |

0.25 |

The optimization problem is formulated as:

maximize

subject to

≥ 0

Results:

| Asset |

Weight (%) |

| BTC |

30.12 |

| ETH |

26.34 |

| SOL |

19.17 |

| BNB |

24.37 |

Interpretation: The allocation reflects embedded preferences: BTC receives a higher share due to its importance, while SOL is penalized.

3. Results and Discussions

This section presents and interprets the empirical results obtained by applying the three entropy-based portfolio optimization models to a cryptocurrency portfolio composed of Bitcoin (BTC), Ethereum (ETH), Solana (SOL), and Binance Coin (BNB). All models were implemented under identical constraints, including a fixed variance threshold (

= 0.0015.) and a target return of 0.4, to allow for direct comparison of their diversification behavior and allocation structure.

Table 1 summarizes the optimal weights and entropy values resulting from each model. Notably, all configurations satisfy the imposed risk constraint and produce distinct diversification profiles. The Shannon entropy model yields a nearly uniform allocation, promoting structural balance. The Tsallis model produces a more asymmetrical structure, penalizing dominant weights and favoring assets with complementary statistical properties. The Weighted Shannon model reflects informational priorities by assigning higher weights to BTC and ETH, in line with their presumed strategic importance.

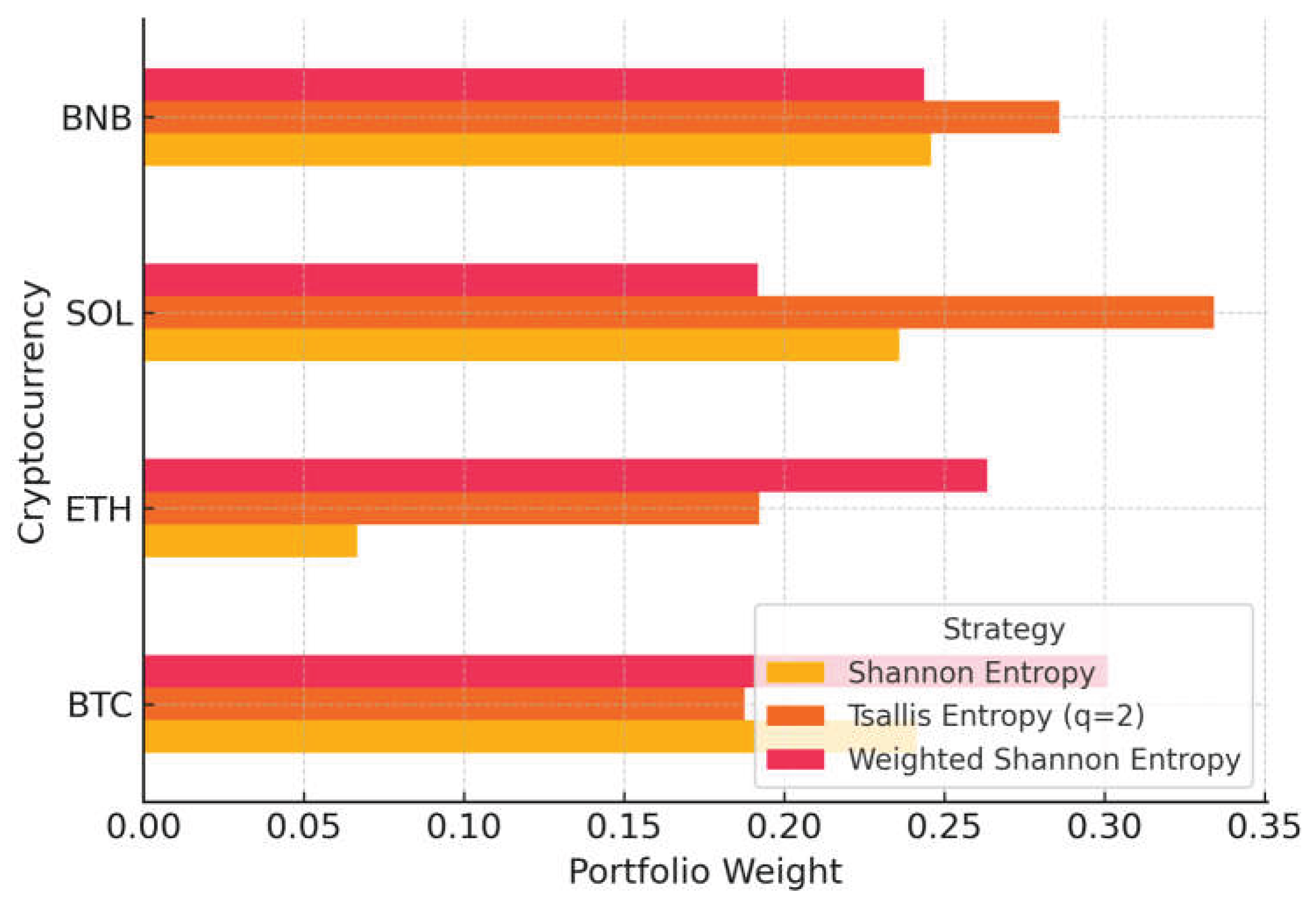

Figure 1 illustrates these allocations graphically, providing a clear visual comparison of capital distribution across the three models.

From a theoretical perspective, entropy-based portfolio optimization diverges significantly from traditional mean–variance approaches. While variance minimization focuses on the statistical dispersion of returns through the expression entropy maximization operates on the principle of distributional balance, formalized as . These objectives, though distinct, are complementary: the former targets risk concentration, while the latter promotes structural diversification. In high-uncertainty environments, entropy serves as a regularization mechanism—stabilizing allocations even in the absence of precise return estimates. This conceptual distinction highlights the added value of entropy within the broader landscape of portfolio theory, particularly when classical assumptions regarding return predictability or normality are violated

3.1. Maximum Shannon Entropy Model

The Maximum Shannon Entropy model generates a near-uniform allocation across the portfolio, as shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. This behavior is consistent with the model’s objective of maximizing diversification by treating all assets as equally informative and structurally equivalent. In the observed results, each asset receives approximately 24–25% of the total capital, with the exception of ETH, which is assigned a notably lower weight (6.68%). This deviation is likely due to its higher volatility, which increases the marginal cost of including it under the imposed variance constraint.

The resulting entropy value of 1.3869 closely approximates the theoretical maximum ln4≈1.3863, confirming that the allocation achieves full diversification under the entropy criterion. This outcome validates Shannon entropy as a suitable measure of portfolio balance, especially when the investment environment is characterized by distributional uncertainty and the absence of strong informational priors. The model performs particularly well in high-volatility settings by diffusing capital away from dominant risk concentrations.

3.2. Maximum Tsallis Entropy Model

The Maximum Tsallis Entropy model introduces a nonextensive statistical framework by using a generalized entropy function with q=2q = 2q=2. Compared to the Shannon model, Tsallis entropy imposes a stronger penalization on concentrated allocations, which results in a more asymmetric portfolio distribution. As presented in

Table 1, the model shifts significant capital toward SOL (33.42%) and BNB (28.59%), while BTC and ETH receive more modest shares—18.77% and 19.22%, respectively.

This behavior reflects the model’s increased sensitivity to dominant weights, which are more heavily penalized as their magnitude grows. The entropy value of 0.7414 is substantially lower than that of the Shannon model, indicating a more selective form of diversification. Rather than aiming for uniformity, Tsallis entropy prioritizes structural balance through concentration avoidance, which makes it particularly well-suited for environments with tail risks, fat-tailed return distributions, and nonlinear inter-asset dependencies—characteristics often found in cryptocurrency markets.

By discouraging overexposure to any single asset, the model enhances robustness in highly unstable environments and favors allocations that hedge against extreme downside scenarios. This quality makes the Tsallis entropy model a compelling alternative for risk-aware investors operating in data-sparse, volatile markets.

3.3. Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy Model

The Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy model extends the classical Shannon formulation by incorporating asset-specific informational weights, allowing the allocation process to reflect subjective preferences, strategic relevance, or external criteria such as ESG ratings or market influence. In this study, the weights were assigned as follows: BTC (0.30), ETH (0.25), BNB (0.25), and SOL (0.20), simulating a scenario where BTC and ETH are considered more significant from an informational or strategic perspective.

As seen in

Table 1, the resulting allocation favors BTC (30.12%) and ETH (26.34%) over SOL (19.17%), despite the latter having received a larger share under the Tsallis entropy model. The entropy value achieved (1.3125) remains close to the maximum observed in the uniform case (Shannon model), indicating that the portfolio retains a high degree of diversification while integrating preferential structure.

This hybrid behavior—balancing diversification with informational priority—makes the weighted entropy model highly adaptable to real-world investment scenarios, where decisions are rarely based solely on statistical distribution but often influenced by qualitative insights or investor confidence. The framework’s flexibility also allows for dynamic updates as new data or strategic objectives emerge.

Overall, the weighted model offers a powerful compromise: it maintains entropy's mathematical rigor while enhancing interpretability and customization in portfolio construction. This makes it especially attractive in institutional settings or algorithmic strategies that require both diversification and the incorporation of expert judgment.

4. Conclusions

This study proposed a unified and theoretically rigorous framework for entropy-based portfolio optimization, offering a viable alternative to the traditional mean–variance paradigm. By addressing well-documented shortcomings—such as the sensitivity of variance-based models to distributional assumptions and the inability to accommodate systemic uncertainty—this research contributes a more generalizable and robust methodology for diversification and risk management.

Three distinct entropy-based formulations were analyzed and implemented:

The Maximum Shannon Entropy Model, which promotes uniform diversification through an information-theoretic lens;

The Second-Order (Tsallis) Entropy Model, which captures nonlinear interdependencies and offers flexibility in managing heavy-tailed return distributions;

The Maximum Weighted Shannon Entropy Model, which integrates structural beliefs and asset-specific informational weights into the optimization process.

All models were derived using Lagrangian optimization techniques, ensuring full compliance with risk-return constraints and enabling implementation in both static and algorithmic investment settings. Empirical validation was conducted through multiple case studies using weekly return data from Q1 2025 for four major cryptocurrencies (BTC, ETH, SOL, and BNB). The results confirmed the enhanced diversification, reduction of concentration risk, and robustness to volatility achieved by entropy-based methods—particularly within the challenging environment of digital asset markets.

Table 2 summarizes the entropy values and confirmed variance levels across the three models, reinforcing their structural distinctions and empirical consistency.

Among the findings:

The Shannon model achieved near-maximum entropy under tight risk controls;

The Tsallis model produced distinct allocations by strongly penalizing large weights.;

The weighted model enabled customized allocation via informational weights.

These mechanisms enabled a strategic trade-off between maximizing return potential, minimizing systemic concentration, and preserving allocation flexibility. This combination offers a compelling enhancement to traditional portfolio theory. In conclusion, this study elevates entropy from a theoretical abstraction to a core structural element in modern portfolio design. Thanks to its distribution-free nature, axiomatic consistency, and computational viability, entropy-based modeling proves particularly advantageous in contexts with non-normal returns, incomplete data, and unstable market regimes.

Future research directions may explore:

Dynamic entropy optimization in multi-period settings;

The inclusion of real-world frictions (e.g., transaction costs or taxation);

Validation of entropy-based strategies across broader asset classes, emerging markets

By doing so, the operational scope and practical relevance of entropy-based portfolio construction in quantitative finance will continue to expand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Florentin Șerban and Sivia Dedu; methodology, Florentin Șerban and Sivia Dedu; validation, Florentin Șerban; formal analysis, Florentin Șerban and Sivia Dedu; investigation, Florentin Șerban; resources, Florentin Șerban; data curation, Silvia Dedu; writing—original draft preparation, Florentin Șerban; writing—review and editing, Florentin Șerban; visualization, Florentin Șerban and Sivia Dedu;; supervision, Florentin Șerban. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Markowitz, H. Portfolio Selection. Journal of Finance 1952, 7, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Speranza, M.G. Linear programming models for portfolio optimization. Finance 1993, 14, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.F. Semivariance and stochastic dominance: Implications for utility theory and portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 1993, 48, 871–883. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.F.; Jensen, G.R. A comparison of mean–semivariance and mean–variance portfolio selection models. Journal of Portfolio Management 1992, 18, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Konno, H.; Yamazaki, H. Mean-absolute deviation portfolio optimization model and its applications to Tokyo stock market. Management Science 1991, 37, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.J.; Baptista, A.M. Economic implications of using a mean-VaR model for portfolio selection: A comparison with mean-variance and mean-conditional value-at-risk. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 2002, 26, 1159–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K.; Janssen, J. A separable programming approach to portfolio selection with transaction costs and constraints. Annals of Operations Research 1998, 85, 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pogue, G.A. An extension of the Markowitz portfolio selection model to include variable transactions' costs, short sales, leverage policies and taxes. Journal of Finance 1970, 25, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, A.; Rosenberg, B. Risk and Return in the Capital Asset Pricing Model: Evidence Using Linear Programming. Journal of Finance 1979, 34, 415–434. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto, A. The mean–variance approach to portfolio optimization subject to transaction costs. Journal of the Operations Research Society of Japan 1996, 39, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMiguel, V.; Garlappi, L.; Uppal, R. Optimal versus naive diversification: How inefficient is the 1/N portfolio strategy? Review of Financial Studies 2009, 22, 1915–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMiguel, V.; Garlappi, L.; Nogales, F.J.; Uppal, R. A generalized approach to portfolio optimization: Improving performance by constraining portfolio norms. Management Science 2009, 55, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. A new methodology for ordinal multiobjective decisions based on fuzzy sets. Decision Sciences 1982, 13, 589–600. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.M.; Parkan, C. A minimax disparity approach for fuzzy multi-criteria decision making with entropy weights. Computers & Operations Research 2006, 33, 1289–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Philippatos, G.C.; Wilson, C.J. Entropy, market risk, and the selection of efficient portfolios. Applied Economics 1972, 4, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippatos, G.C.; Wilson, C.J. The use of entropy measures in finance: A note. Journal of Finance 1974, 29, 195–196. [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli, R. Portfolio selection using Shannon entropy. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2002, 314, 762–768. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, R.; Nie, X.; Zhang, B. Entropy-based portfolio optimization in large-scale settings. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 181, 115149. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Y.; Zhang, L. A mean–variance–entropy portfolio model with Shannon entropy constraints. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2023, 450, 128127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R. Entropy-based financial risk measures: A review. Entropy 2020, 22, 1025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y. Entropy-based multi-objective portfolio optimization with higher moment constraints. Quantitative Finance 2023, 23, 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez, N.; Miramontes, O. Shannon Entropy: An Econophysical Approach to Cryptocurrency Portfolios. Entropy 2022, 24, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, K. Comparative analysis of entropy-based and variance-based portfolio optimization. Entropy 2020, 22, 1357. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Physical Review 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsheikh, A.; Egret, J. Portfolio selection under entropy and higher-order moments: A new hybrid optimization model. Annals of Operations Research 2021, 303, 511–532. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. An entropy-based framework for optimal electricity procurement. Energy Economics 2024, 127, 106887. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M.K.; Bouri, E.; Saeed, T. Cryptocurrencies and portfolio diversification: A risk-based entropy approach. Research in International Business and Finance 2022, 60, 101627. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, P. Robust cryptocurrency portfolio optimization using entropy measures under extreme volatility. Financial Innovation 2022, 8, 34. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).