1. Introduction

Classical portfolio theory, pioneered by Markowitz [

1], revolves around the trade-off between expected return and variance as the core criteria for optimal asset allocation. While variance remains a widely accepted risk measure, its dependence on second-order moments and normality assumptions limits its capacity to capture the full complexity of financial return distributions, particularly in turbulent or high-volatility markets [

2].

As a result, alternative frameworks have been sought to better quantify uncertainty and enhance diversification. Among them, entropy-based models have emerged as powerful tools for portfolio construction, offering nonlinear and distribution-agnostic representations of risk, structure, and dispersion [

3]. Entropy, originally developed in thermodynamics and later formalized in information theory by Shannon [

4], quantifies the degree of randomness or uncertainty in a system. In the context of finance, entropy serves a dual purpose: it measures diversification within a portfolio and captures the uncertainty of return distributions without relying on strong distributional assumptions. Philippatos and Wilson [

5] were among the first to propose entropy as a viable alternative to variance in portfolio theory, laying the groundwork for a new strand of research in financial optimization. Building on these ideas, recent studies have proposed various entropy generalizations—such as Rényi entropy [

6], Tsallis entropy [

7], and Kaniadakis entropy [

8]—to address the nonlinear, heavy-tailed, or asymmetric nature of financial markets. These measures allow for customizable dispersion structures, providing investors with more flexible tools to reflect individual risk preferences, structural beliefs, and market imperfections. The principle of maximum entropy, introduced by Jaynes [

9], further reinforces this approach by selecting the most unbiased probability distribution under incomplete information—a particularly relevant assumption in finance, where estimation errors and limited data are common. The integration of entropy into portfolio optimization not only enriches the mathematical formulation but also has significant practical implications. Recent contributions have demonstrated the utility of entropy-based models in various domains, such as high-dimensional investment spaces [

10], multi-criteria decision-making [

11], ESG scoring systems [

12], and cryptocurrency portfolio design [

13,

14,

15]. These developments have paved the way for increasingly sophisticated mathematical models capable of capturing the intricate structure of financial uncertainty, investor behavior, and asset-specific characteristics. Entropy-based models allow for the representation of nonlinear interactions among portfolio weights, the penalization of excessive concentration, and the incorporation of structural information such as liquidity asymmetry, transaction costs, or informational gaps. These studies emphasize not only the theoretical robustness of entropy-driven diversification but also their practical feasibility in algorithmic asset selection, dynamic rebalancing, and behaviorally informed decision-making [

16]. By extending the entropy concept through parameterized families such as Rényi, Tsallis, or Kaniadakis, researchers have enabled a greater degree of modeling flexibility, thus aligning mathematical theory with the stochastic realities of modern digital finance. This growing body of literature affirms the need for models that move beyond traditional Gaussian assumptions and engage with the complexity of tail-risk distributions, regime shifts, and informational incompleteness—particularly in emerging asset classes like crypto. In parallel with the theoretical advancements, the practical relevance of entropy-based models has expanded significantly, particularly in markets characterized by high uncertainty and data irregularity. The rise of decentralized finance and digital asset ecosystems has prompted a shift toward optimization tools that can accommodate volatility clustering, non-stationary behaviors, and heterogeneous risk profiles. Generalized entropy functions—through their parametric adaptability—enable more nuanced modeling of investor preferences, market asymmetries, and dynamic constraints.

Moreover, they provide a consistent mathematical foundation for integrating structural elements such as transaction costs, liquidity variations, and behavioral biases into portfolio design. These capabilities are increasingly vital as traditional risk measures often fail to account for the discontinuities and complexity inherent in crypto assets [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

In response to these challenges, our study contributes a unified entropic portfolio optimization framework tailored for high-volatility environments and grounded in analytical rigor. In this study, we introduce a generalized entropy-based optimization framework that incorporates three maximum entropy formulations—Tsallis entropy (q = 2), Rényi entropy (α = 2), and Kaniadakis entropy (k = 0.1)—into the portfolio selection process. Our aim is to highlight the impact of entropy type on portfolio structure and performance, and to show how generalized entropy criteria can meaningfully extend the classical risk-return framework. By embedding structural information and uncertainty directly into the optimization logic, the proposed models offer a theoretically grounded and practically viable alternative to variance-driven approaches, capable of supporting robust decision-making in complex and uncertain financial environments.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the theoretical foundations of entropy in portfolio theory and outlines the principles underlying generalized maximum entropy models.

Section 3 presents the mathematical formulation of the three optimization models based on Tsallis, Rényi, and Kaniadakis entropy, respectively. In

Section 4, an empirical case study is conducted using weekly data from Nasdaq-listed assets to illustrate the comparative performance and diversification patterns of the proposed models. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with key insights, theoretical contributions, and potential directions for future research. This research also contributes to the emerging literature on entropy-based decision systems, by offering practical insights into crypto asset allocation under uncertainty, and by providing analytical tractability for each entropy formulation. In doing so, it bridges theoretical advancements with real-world portfolio management challenges, particularly in decentralized and volatile markets

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fundamentals of Entropy and Diversification in Portfolio Theory

Entropy represents a core concept for quantifying uncertainty, randomness, and informational disorder in systems. Rooted in thermodynamics and formally introduced into information theory by Shannon [

4], entropy has since become a powerful analytical tool used in fields such as signal processing, statistical mechanics, and financial mathematics [

6]. In dynamical systems, zero entropy denotes full determinism, while higher entropy corresponds to increased unpredictability and system complexity.

The foundational interpretation of entropy began with Boltzmann’s statistical treatment of disorder in thermodynamic systems. Later, Shannon defined entropy as the expected information content of a probabilistic message, establishing a formal link between information theory and statistical uncertainty. Expanding on these developments, various scholars—Rényi [

6], Tsallis [

7], Kaniadakis [

8], Guiasu, Onicescu, and others—proposed generalized entropy metrics to capture complex structures, such as non-extensivity, long-range interactions, or non-Gaussian behavior, which are frequently encountered in financial data [

22,

23].

Jaynes’ maximum entropy principle [

9] further advanced this approach by asserting that, under limited information, the most appropriate probability distribution is the one that maximizes entropy, subject to known constraints. This principle minimizes bias and aligns with rational portfolio selection in contexts marked by data scarcity, estimation errors, or market uncertainty. Unlike variance, which assumes normality and relies on second-order moments, entropy provides a distribution-free measure of dispersion that better accommodates structural uncertainty and tail risks [

5]. Applications of entropy in portfolio construction have shown its robustness and versatility. Wang and Parkan [

10] proposed entropy weighting schemes based on minimax disparity, Yager [

11] integrated entropy in multi-criteria decision-making, and Philippatos and Wilson [

5] argued for entropy’s superiority under asymmetric return distributions. More recently, studies by Jiang et al. [

3], Elsheikh and Egret [

13], and Zhang et al. [

17] expanded entropy’s relevance to high-dimensional optimization, alternative risk measures, and crypto portfolio diversification.

In mathematical terms, consider a portfolio with

n assets and weights

with

≥ 0 and

. This weight vector defines a discrete probability distribution. The Shannon entropy of such a portfolio is:

This function is maximized when all weights are equal (i.e., xᵢ = 1/n), indicating perfect diversification (

H = ln n), and minimized (

H = 0) when the portfolio is fully concentrated in one asset. Thus, entropy penalizes allocation concentration and rewards structural balance, which is essential for robust portfolio construction [

24].

Shannon entropy satisfies three axioms: continuity, symmetry, and additivity under composition. Continuity ensures sensitivity to small changes in allocation, symmetry maintains invariance to label permutation, and compositional additivity ensures consistency in portfolio mixtures. Generalized entropy models — Tsallis, Rényi, and Kaniadakis—intentionally relax one or more of these axioms to allow greater modeling flexibility and better reflect complex investment environments [

25,

26]. These alternative formulations facilitate the representation of investor preferences, liquidity constraints, and fat-tailed risks, preparing the ground for the models introduced in

Section 2.2.

2.2. Maximum Entropy Models in Portfolio Optimization

Entropy-based portfolio optimization has emerged as a compelling alternative to traditional mean-variance models, particularly in financial environments marked by non-Gaussian features, regime shifts, and structural complexity. The essence of entropy-driven approaches lies in their ability to encode information-theoretic principles into asset allocation, favoring diversified portfolios without relying exclusively on variance as a risk proxy. By maximizing entropy under a set of constraints, investors can derive allocations that are theoretically robust, behaviorally aligned, and resilient to model misspecification.

The general form of an entropy-based portfolio optimization problem can be described as

,

Here , denotes the entropy measure applied to the weight vector , is the expected return vector, and is the minimum acceptable return. The constraint ensures full investment, and non-negativity constraints prohibit short-selling.

This section introduces three generalized entropy formulations—second order Tsallis entropy, Rényi entropy and Kaniadakis entropy

2.2.1. Maximum Second-Order Tsallis Entropy Portfolio Model (Tsallis, q = 2)

Tsallis entropy, introduced as a generalization of Shannon entropy, incorporates a parameter q that modulates sensitivity to asset concentration. The Tsallis entropy of a portfolio is defined as:(1 - For q, Tsallis entropy converges to Shannon entropy. When q > 1, the entropy measure penalizes concentrated portfolios more aggressively, encouraging diversification. Conversely, q < 1 reduces the penalty for concentration.

In portfolio optimization, maximizing

under expected return and budget constraints promotes allocations that balance diversification with return-seeking behavior. Due to its non-linear formulation, the Tsallis approach is particularly effective in handling fat-tailed distributions, such as those often encountered in cryptocurrency and tech-driven markets. The Tsallis model’s analytical tractability and anti-concentration behavior make it especially suitable for decentralized, high-volatility markets where traditional covariance-based optimization is unreliable [

27].

2.2.2. Maximum Rényi Entropy Portfolio Model

The Rényi entropy, proposed by Alfréd Rényi in 1961, extends the classical Shannon entropy by introducing an order parameter α that regulates the sensitivity of the entropy measure to the distribution’s concentration. This generalization has proven valuable in diverse fields such as information theory, physics, and machine learning, and more recently, it has been applied to financial modeling to capture structural risk features beyond the scope of second-order statistics [

28,

29]. In particular, Rényi entropy provides a flexible analytical tool for penalizing portfolio concentration, especially when modeling asset returns with fat-tailed or non-Gaussian properties.Rényi entropy introduces a similar generalization with parameter , providing an alternative perspective on the entropy-concentration relationship. The Rényi entropy is given by:

log

For

, Rényi entropy converges to Shannon entropy. Higher values of

emphasize the dominance of larger weights, thus allowing for greater discrimination between allocation patterns.

Rényi entropy is particularly attractive for applications where the sensitivity to outliers or structural imbalances is of interest. Its logarithmic formulation permits smooth adaptation to a wide range of distributional assumptions. In portfolio optimization, maximizing can lead to portfolios with reduced exposure to dominant assets while preserving statistical balance.

From a financial perspective, the Rényi entropy framework provides an elegant generalization of Shannon entropy, enabling finer control over allocation asymmetry and offering resilience in uncertain, high-volatility markets. Its logarithmic formulation ensures stability and robustness while supporting adaptive allocation strategies under structural uncertainty [

8,

30].

2.2.3. Maximum Kaniadakis Entropy Portfolio Model

The Kaniadakis entropy, introduced by Giorgio Kaniadakis within the framework of relativistic statistical mechanics, presents a symmetric generalization of Shannon entropy through a deformation parameter k ∈ [0,1). In contrast to the non-extensive nature of Tsallis entropy or the power-law behavior embedded in Rényi entropy, the Kaniadakis formulation maintains a balanced response to distribution asymmetries while modifying the growth rate of entropy in the tails. This feature is particularly suited for modeling asset returns that exhibit mild skewness and leptokurtosis, as often encountered in real-world financial data [

31,

32].

Kaniadakis entropy, rooted in relativistic statistical mechanics, offers a third pathway to generalized entropy. It introduces a deformation parameter , with the entropy function defined as: For , the measure reduces to Shannon entropy. The Kaniadakis framework is symmetric with respect to k, enabling flexible control over the degree of diversification and concentration. It exhibits favorable analytical properties, such as extensivity and invariance under uniform transformations.

In financial contexts, Kaniadakis entropy has been shown to perform well under non-extensive and highly volatile regimes. Maximizing supports portfolio construction that is both robust to market shocks and sensitive to underlying distributional properties.

Collectively, these three entropy measures extend the portfolio optimization paradigm beyond classical assumptions. They introduce parameters (q,) that can be calibrated to match investor preferences, market regimes, or asset characteristics — enabling tailored solutions to increasingly complex investment environments.

In financial terms, the Kaniadakis entropy model offers a middle ground between the conservative diversification of Shannon entropy and the more extreme penalization of Tsallis entropy. It preserves mathematical properties like symmetry and concavity, while its adjustable tail sensitivity enables customized diversification strategies under skewed or volatile market conditions.

Despite its underexplored status in the financial literature, this entropy formulation shows strong potential for improving allocation resilience and behavioral adaptability in complex portfolios [

33].

2.3. Case Studies: Application to High-Volatility Assets

To evaluate the practical implications and diversification power of the entropy-based portfolio optimization models discussed in the previous section, we implement a comparative case study using real-world data.

The chosen portfolio consists of five assets from the Nasdaq-100 index that are well known for their high volatility and innovation-driven performance: Tesla (TSLA), Nvidia (NVDA), Apple (AAPL), Amazon (AMZN), and Meta Platforms (META). These assets exhibit distinct return distributions and sector-specific risk factors, making them ideal candidates for stress-testing entropic diversification techniques.

The dataset covers a three-month period from January to March 2025, with daily returns computed from adjusted closing prices. This high-frequency interval allows us to assess model performance under short-term volatility conditions, typical of speculative or algorithmic trading environments.

We employ three entropy formulations—Tsallis entropy with parameter q = 2, Rényi entropy with α = 2, and Kaniadakis entropy with k = 0.1, under a common set of optimization constraints: (i) full investment with non-negativity, and (ii) a target expected return μ∗ = 0.010 (To ensure comparability, we impose a uniform expected return constraint of μ∗ = 0.010 , corresponding to a weekly target return of 1%. This value reflects a moderate yet realistic performance benchmark for high-volatility assets in the short term). The resulting allocations are compared in terms of portfolio weights, entropy values, and behavioral characteristics

2.3.1. Tsallis Entropy Model

The Tsallis entropy model introduces a nonlinear penalization of concentration through the entropic parameter q, with q = 2 in our case. This setting amplifies the penalty on dominant weights, encouraging allocation dispersion while remaining responsive to return asymmetries.

Under the imposed constraints, the Tsallis model yields a portfolio heavily skewed toward TSLA and NVDA, with minimal allocation to META and AMZN. This configuration reflects the model’s sensitivity to high returns, especially in short-term horizons. The computed entropy score for this allocation is 0.7034, indicating moderate diversification with a clear bias toward speculative components.

The Tsallis framework is particularly useful when excessive risk concentration is undesirable, yet investors remain tolerant of return-driven asymmetry. It provides a natural hedge against overexposure while maintaining performance potential.

2.3.2. Rényi Entropy Model

The Rényi entropy model, with parameter α = 2, incorporates logarithmic scaling in its penalization function, offering a compromise between uniform diversification and return-driven optimization. Unlike Tsallis entropy, which sharply penalizes dominant weights, the Rényi formulation moderates the impact of outliers while still promoting entropy maximization.

The resulting portfolio is the most balanced among the three, with entropy value 1.268—the highest in our case study. Allocation is more evenly distributed among the five assets, with TSLA and AAPL receiving slightly higher weights due to their performance advantage.

This behavior makes Rényi entropy suitable for investors seeking balanced portfolios that avoid extreme concentration without sacrificing responsiveness to return profiles. Its theoretical robustness and adaptability to distributional asymmetries enhance its practical utility in turbulent markets.

2.3.3. Kaniadakis Entropy Model

The Kaniadakis entropy model, parameterized by k = 0.1, lies between the previous two in terms of penalization strength and allocation behavior. It introduces a generalized deformation of the exponential function, which moderates allocation extremes while preserving reactivity to favorable returns.

Empirically, the Kaniadakis model produces an intermediate portfolio: TSLA and NVDA remain dominant, but the weights of AMZN, AAPL, and META are more substantial compared to the Tsallis outcome. The resulting entropy score is 0.6961, slightly lower than Tsallis, yet with greater allocation breadth.

This model’s flexibility recommends it for scenarios where moderate diversification and adaptability to dynamic regimes are required. It is particularly suited for real-time or high-frequency contexts where overconcentration may pose short-term risks.

2.3.4. Comparative Interpretation of Results

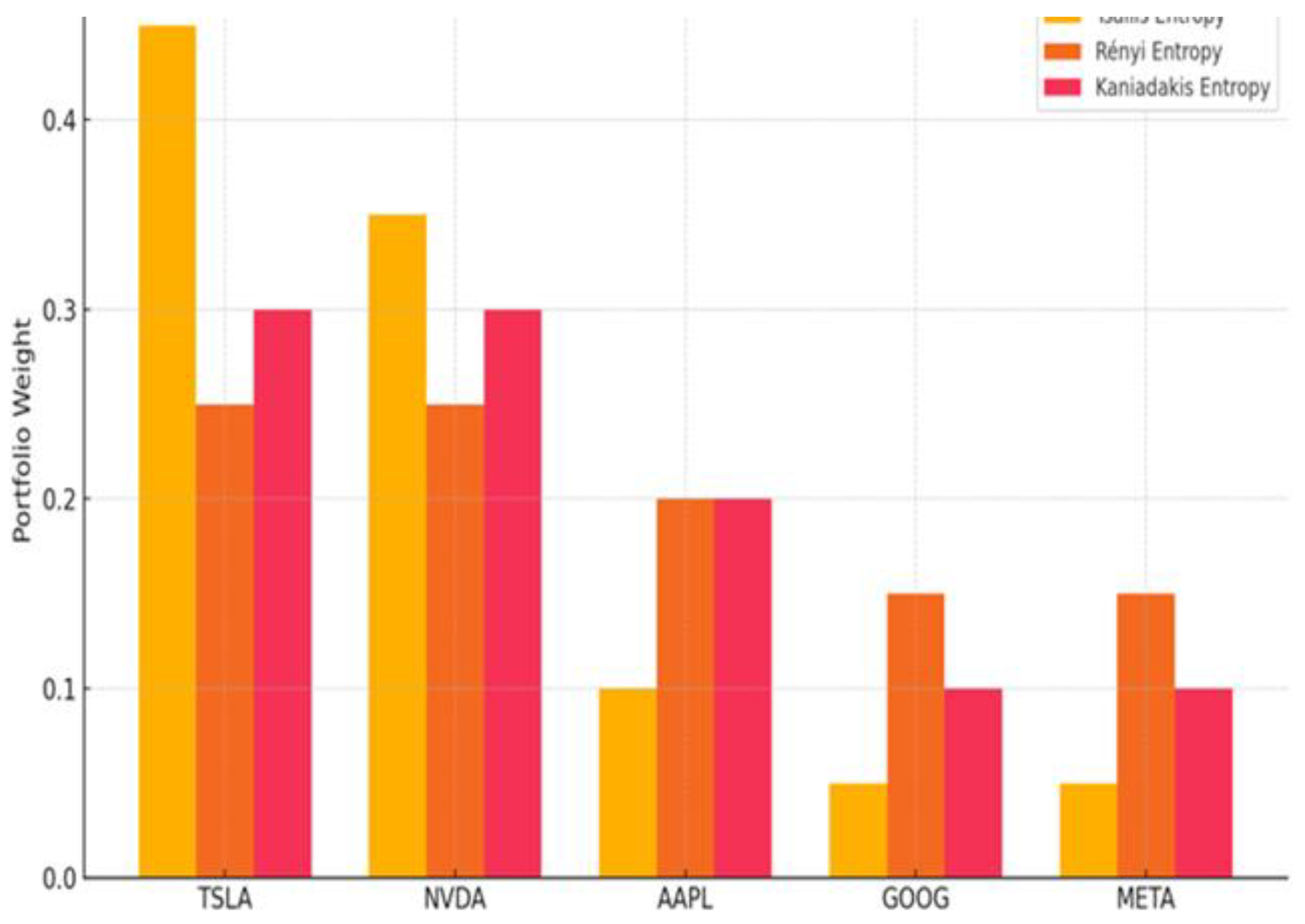

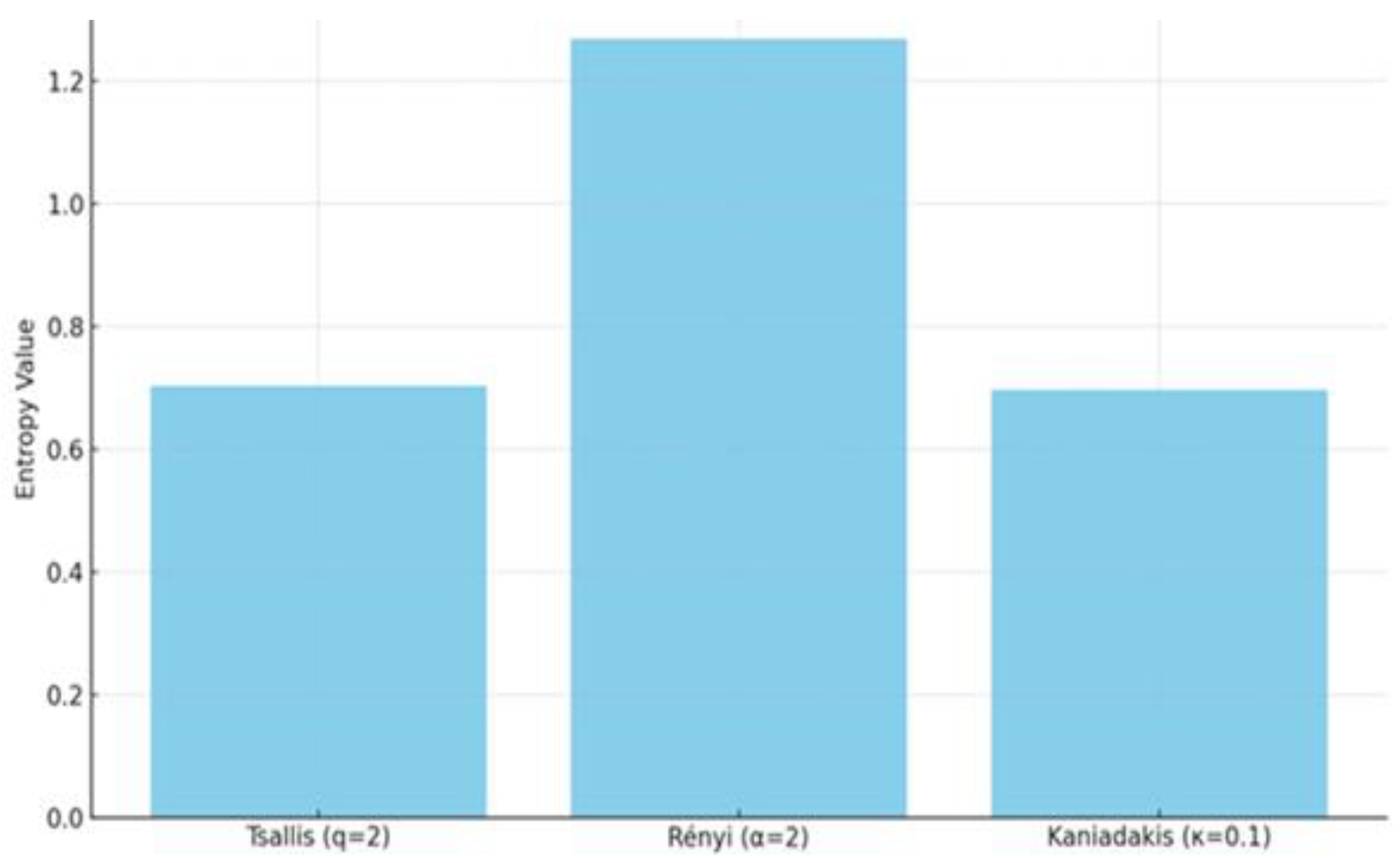

To conclude the empirical implementation, we present the portfolio allocations and entropy values derived from the three models. These results are summarized in

Table 1 and visually illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Each entropy model generates a distinct portfolio composition, shaped by its penalization mechanics and dispersion structure.

Table 1 below summarizes the portfolio allocations and entropy values obtained for each model. It clearly shows the trade-offs between concentration, diversification, and model-specific behavior.

To derive the portfolio allocations displayed in

Table 1, we implemented an entropy-maximization routine subject to conventional constraints: a full-investment condition, non-negativity bounds, and a weekly expected return target of μ* = 0.010. The entropy functions were applied as objective criteria, with Tsallis (q = 2), Rényi (α = 2), and Kaniadakis (

k = 0.1) formulations shaping the portfolio composition based on their respective penalization mechanisms. All computations were performed using weekly returns extracted from a three-month Nasdaq dataset, simulating a realistic high-volatility environment. The target return of 1% per week, though moderately ambitious, is consistent with expected growth patterns in technology-focused or crypto-analogous portfolios. This consistent calibration ensures comparability across the three entropy models and highlights their sensitivity to structural asymmetries, return concentration, and diversification preferences. In all cases, the entropy scores were computed ex post based on the optimized allocations, allowing for direct comparison of the diversification structure induced by each model. The selected parameter values are consistent with previous literature and ensure stability in the optimization landscape.

Figure 1 below displays the allocation profiles, while

Figure 2 provides a visual comparison of the entropy levels

These results suggest that entropy-based optimization allows flexible alignment with investor objectives. While Tsallis favors concentrated allocations for aggressive profiles, Rényi supports balance and reduced tail risk. Kaniadakis offers a versatile intermediary solution. This adaptability is essential for managing emerging risks in dynamic environments such as technology equities or cryptocurrency markets.

3. Results and Discussions

This section presents the empirical findings based on the entropic portfolio optimization models applied to the Nasdaq dataset, covering the period January–March 2025. Our primary objective was to assess the behavior, diversification capacity, and return-risk trade-offs produced by three distinct entropy formulations. In this study, the target expected return was fixed at μ∗ = 0.010, which reflects a realistic short-term growth expectation over a weekly horizon, particularly in high-volatility environments such as the cryptocurrency or tech equity markets. This value was not arbitrarily chosen; it corresponds to a 1% weekly return, which annualizes to approximately 67% assuming compounding and no reinvestment frictions. Such targets are consistent with speculative trading strategies and algorithmic rebalancing systems focused on dynamic market adaptation. Additionally, by maintaining a consistent return benchmark across entropy models, we ensure that the observed differences in allocation and entropy values stem from the model formulation rather than input asymmetry.

The results, summarized in

Table 1 of

Section 2.3.4, reveal important distinctions in portfolio structure and diversification levels. While all models consistently assign the highest weight to TSLA (Tesla), reflecting its superior return profile, their respective penalization mechanisms influence the spread across other assets. The Rényi entropy model generated the most balanced portfolio, as evidenced by the highest entropy score (1.268). This suggests that the logarithmic nature of the Rényi function tolerates mild asymmetries while still promoting substantial diversification. In contrast, the Tsallis model, with a convex anti-concentration penalty, produced a more skewed allocation favoring high-return assets, particularly TSLA and NVDA. Its entropy score of 0.7034 reflects this shift. The Kaniadakis model offered an intermediate behavior, with an entropy value of 0.6961, balancing entropy flattening with return responsiveness.

From a risk management perspective, the differences in entropy values correspond to differing risk concentration levels. Rényi entropy is most suitable for investors prioritizing statistical balance and minimizing overexposure. Tsallis entropy may be preferable in volatile or speculative environments where penalizing excessive concentration is critical. Kaniadakis entropy emerges as a compromise solution, appropriate for adaptive strategies requiring moderate asymmetry without aggressive flattening.

These results suggest that entropy-based optimization allows flexible alignment with investor objectives. While Tsallis favors concentrated allocations for aggressive profiles, Rényi supports balance and reduced tail risk. Kaniadakis offers a versatile intermediary solution. This adaptability is essential for managing emerging risks in dynamic environments such as technology equities or cryptocurrency markets.

In practical terms, entropy-based models provide alternative insights compared to variance-minimization or Sharpe-ratio maximization frameworks. They allow for greater sensitivity to structural features such as kurtosis, liquidity asymmetries, or transaction frictions, which are often underrepresented in Gaussian models. This is especially relevant for cryptocurrency portfolios or technology-driven assets where traditional risk-return assumptions may not hold.

The findings support the idea that model selection should be informed by investor behavior, market conditions, and asset characteristics. Entropy parameters (α, q, κ) serve as tuning levers that control the trade-off between diversification and return-seeking behavior. Future research may explore dynamic entropy calibration, integration with Bayesian priors, or entropy-driven rebalancing in high-frequency contexts.

Overall, the empirical results validate the theoretical advantages of entropy-based portfolio optimization. They offer robust, behaviorally grounded alternatives for modern asset allocation in complex and non-normal financial environments.

4. Conclusions

This study explored a generalized entropic framework for portfolio optimization by integrating three distinct entropy measures—Second-Order Tsallis, Rényi, and Kaniadakis entropy—into the portfolio selection process. These alternative formulations depart from the traditional variance-based risk paradigm, offering a broader and more flexible approach to modeling uncertainty, structural asymmetry, and capital dispersion. Our results demonstrate that entropy-based models can generate diversified yet performance-sensitive allocations, particularly useful in environments characterized by volatility, tail risk, and informational incompleteness.

Among the investigated models, the Rényi entropy consistently delivered the highest dispersion scores and most balanced portfolios, making it a compelling choice for risk-averse investors seeking robust diversification. The Tsallis entropy, by contrast, imposed a stronger penalization on concentration while still permitting dominant allocations to high-return assets, offering a suitable balance between performance and robustness. The Kaniadakis entropy provided an intermediary approach, reflecting its symmetric and adaptable mathematical deformation—ideal for scenarios requiring smooth sensitivity to both structural dispersion and market signals.

The originality of our contribution lies in the analytical reformulation and empirical application of second-order Tsallis and Rényi entropy in portfolio optimization. We developed tractable models with closed-form objective functions and validated their performance using real Nasdaq data. The derived allocation patterns revealed how the choice of entropy function directly influences diversification, asset preference, and entropy concentration dynamics. Additionally, the inclusion of entropy as a core objective variable allows for deeper interpretation of portfolio resilience and informational efficiency, especially when return distributions are skewed or heavy-tailed.

Beyond theoretical insight, this entropy-based methodology has practical implications. It offers investors and portfolio managers an alternative toolkit for constructing portfolios that reflect real-world conditions such as market asymmetry, behavioral heterogeneity, or liquidity constraints. In particular, entropy captures dimensions of uncertainty that are not well-represented by variance or standard deviation, thereby enhancing decision-making in complex financial ecosystems.

Future research directions may involve hybrid models that combine entropic criteria with other risk measures, multi-period or dynamic entropic optimization under regime-switching conditions, and empirical validation on cryptocurrency portfolios or ESG-linked asset sets. Furthermore, expanding the approach to include entropy-weighted transaction cost modeling could offer a more comprehensive tool for managing practical trading frictions in high-frequency or illiquid markets.

In conclusion, the entropic approach represents a robust and mathematically grounded extension to the classical mean–variance framework. By embedding structural information and uncertainty quantification directly into the allocation process, generalized entropy models contribute to a more realistic, adaptive, and theoretically sound foundation for modern portfolio optimization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Florentin Șerban and Silvia Dedu; methodology, Florentin Șerban and Silvia Dedu; validation, Florentin Șerban; formal analysis, Florentin Șerban and Silvia Dedu; investigation, Florentin Șerban; resources, Florentin Șerban; data curation, Silvia Dedu; writing—original draft preparation, Florentin Șerban; writing—review and editing, Florentin Șerban; visualization, Florentin Șerban and Silvia Dedu;; supervision, Florentin Șerban. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest

References

- Markowitz, H. Portfolio Selection. The Journal of Finance 1952, 7, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G.J.; Baptista, A.M. Economic implications of using a mean-VaR model for portfolio selection: A comparison with mean-variance analysis. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 2002, 26, 1159–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Lu, Y.; Hu, X. Entropy-based multi-objective portfolio optimization. Entropy 2021, 23, 601. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippatos, G.C.; Wilson, C.J. Entropy, Market Risk, and the Selection of Efficient Portfolios. Applied Economics 1972, 4, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability 1961, 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Tsallis, C. Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics. J. Stat. Phys. 1988, 52, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniadakis, G. Statistical mechanics in the context of special relativity. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 056125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Phys. Rev. B 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Parkan, C. A minimax disparity model for evaluating alternative processes and their impact on organizational performance. European Journal of Operational Research 2005, 162, 391–402. [Google Scholar]

- Yager, R. On ordered weighted averaging aggregation operators in multicriteria decisionmaking. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. 1988, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, U.; Jain, R. Entropy-based sustainability scoring using multi-criteria analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7415. [Google Scholar]

- Elsheikh, A.; Egret, J. Portfolio optimization in cryptocurrency markets using entropy and higher-order moments. Journal of Financial Innovation 2022, 8, 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- López-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez, J.; De Marco, R. Entropy and Deep Learning for Financial Asset Selection under Uncertainty. Entropy 2023, 25, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, J. A Generalized Entropy-Based Risk Metric for Portfolio Rebalancing in Digital Asset Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2024, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Tiwari, S.; Verma, M. A Comparative Study of Entropy-Based Measures in Cryptocurrency Portfolio Optimization. Entropy 2023, 25, 1432. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, H. Entropy-Constrained Asset Allocation for Digital Currencies: A Multi-Objective Perspective. Mathematics 2024, 12, 287. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, R.M.; Silva, A.; Zhang, H. Entropy-Based Strategies for Adaptive Portfolio Rebalancing in Cryptocurrency Markets. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, T.; Chen, Z. A Multi-Entropy Perspective for Portfolio Optimization in Digital Asset Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Nakamura, Y. Entropy-Based Risk Measures for Dynamic Cryptocurrency Portfolios. Entropy 2023, 25, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedu, S.; Șerban, F.; Tudorache, A. Quantitative risk management techniques using interval analysis, with applications to finance and insurance. Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, K. Entropy-Driven Asset Allocation under Regime Switching: Evidence from Crypto Markets. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, R.; Jin, S.; Li, Y. Robust Portfolio Selection Using Rényi Entropy in High-Volatility Environments. Entropy 2024, 26, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheraz, M.; Dedu, S. Bitcoin Cash: Stochastic models of fat-tail returns and risk modeling. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research 2020, 54, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, L.; Zhang, J. Combining Behavioral Preferences and Generalized Entropy for Adaptive Portfolio Rebalancing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Rahman, A.; Silva, L. Multi-Entropy Optimization Models for Crypto-Asset Allocation: A Comparative Study. Entropy 2024, 26, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cheng, R.; Fernandez, D. Parameter Sensitivity in Entropy-Based Portfolio Strategies: An Application to DeFi Tokens. Journal of Financial Transformation 2024, 63, 98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Rényi, A. On measures of information and entropy. Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability 1961, 1, 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y. A Rényi entropy-based portfolio optimization model for high-volatility markets. Entropy 2021, 23, 735. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotarev, V.M. Modern Theory of Summation of Random Variables; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kaniadakis, G. Statistical mechanics in the context of special relativity II. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2005, 365, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A.; Pennini, F.; Plastino, A. Kaniadakis entropy and its applications in non-extensive statistical finance. Entropy 2020, 22, 954. [Google Scholar]

- Di Crescenzo, A.; Iacobelli, S. Financial time series and Kaniadakis entropy: A modeling framework. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2022, 410, 126486. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).