Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Evidence Evaluation

2.2. Spatial Analysis Approach

2.3. Selection of Sites Managed for Pheasant Shooting and Comparison Sites

2.4. Satellite Remote Sensing of Outcome Variables

2.5. Biodiversity Data and Rarefaction

- Administrative area = United Kingdom

- Year = 2010-2024

- Basis of record = Human observation OR Preserved specimen

- Taxon rank = Species

- Scientific name = class Aves

- Scientific name = kingdom Plantae

- Scientific name = family Hesperiidae OR Papilionidae OR Pieridae OR Lycaenidae OR Riodinidae OR Nymphalidae

- Plants (URL: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.eh653t )

- Birds (URL: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.px4x77)

- Butterflies (URL: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.dq98b4)

3. Results

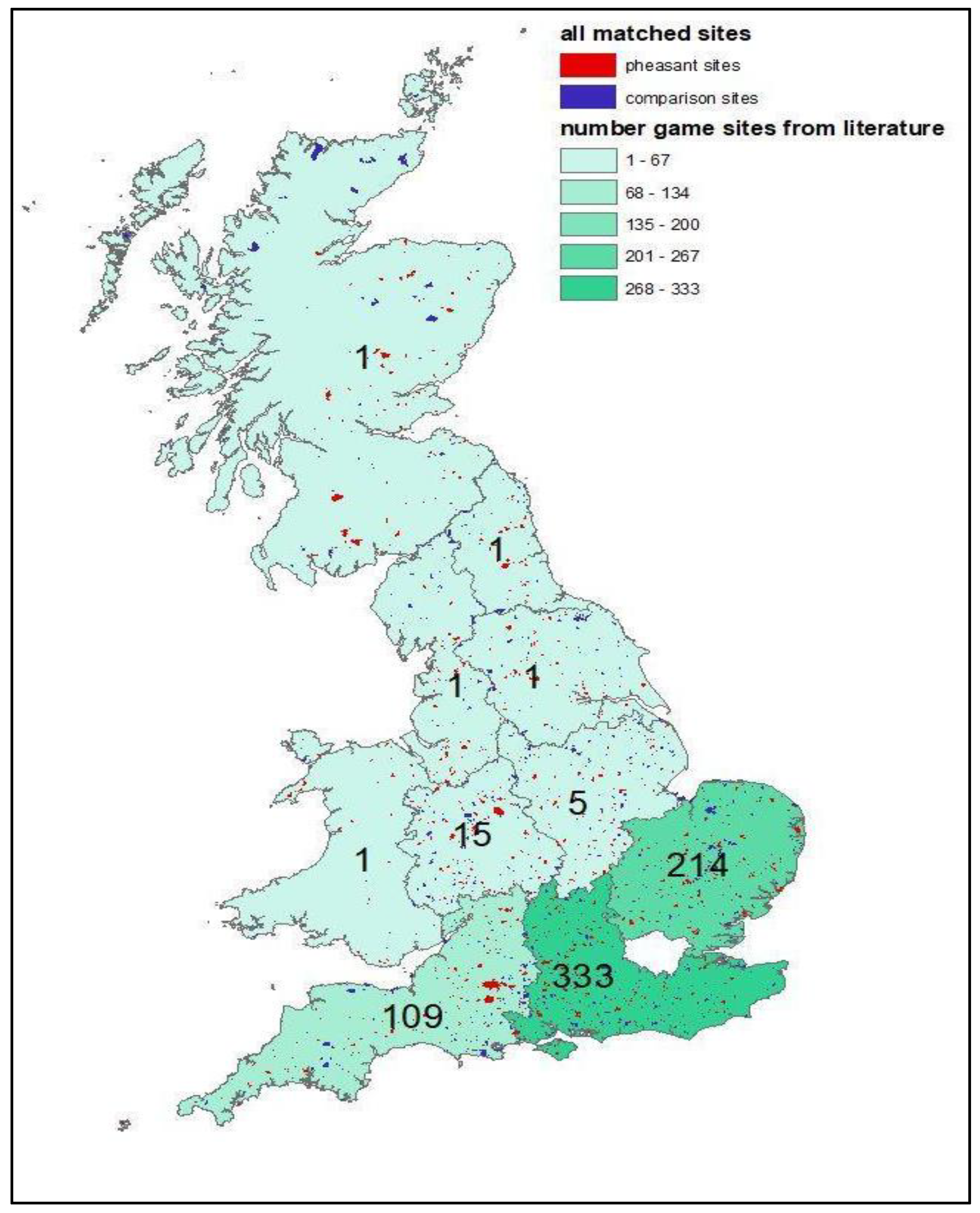

3.1. Location of Studies in the Project

3.2. Systematic Review of Literature

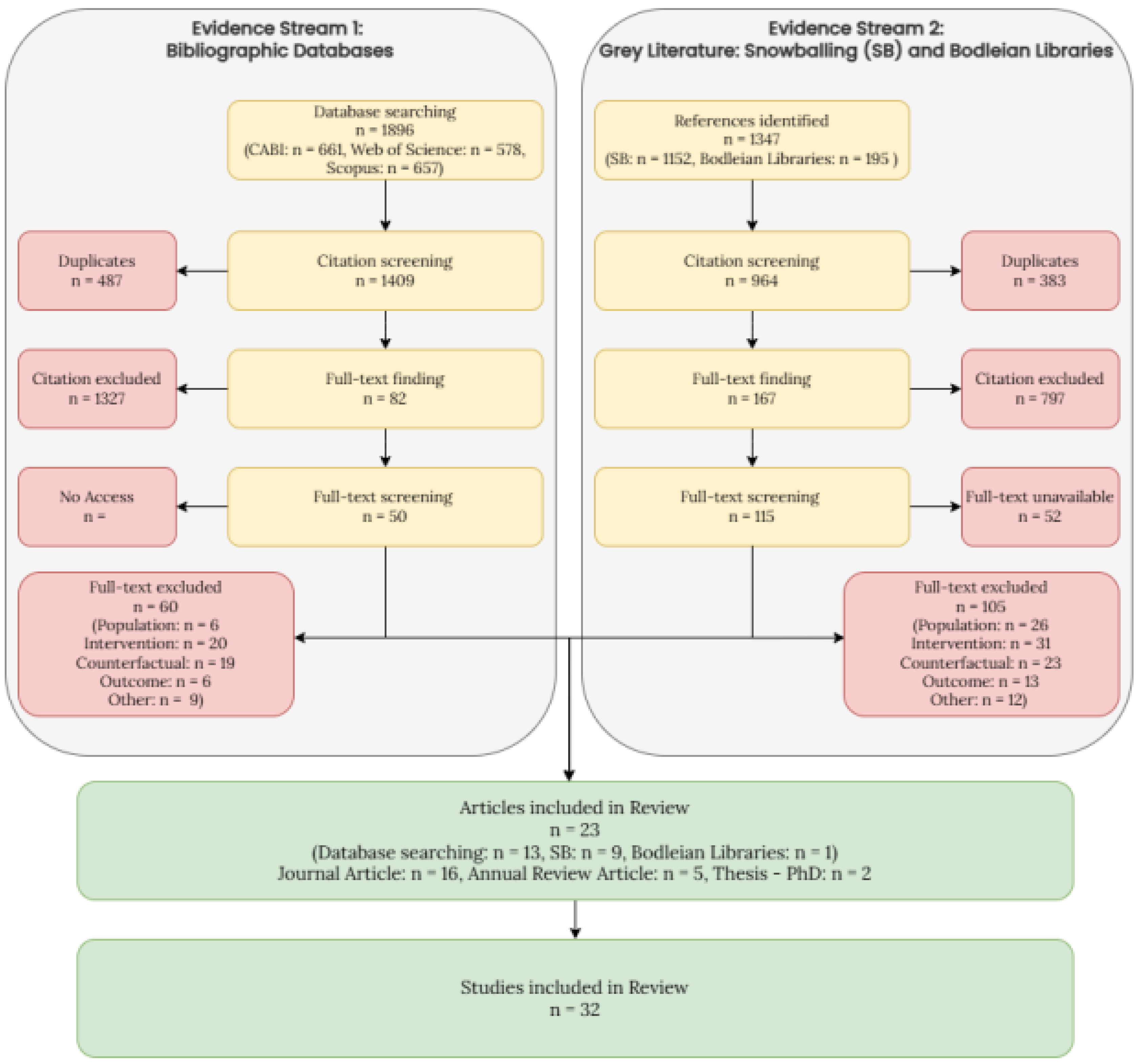

3.2.1. Literature Assessed and Selected

3.2.2. Site Characteristics

3.3.3. Impact of Sites Managed for Pheasant Shooting on Biodiversity

3.2.4. Quality of the Evidence Base

3.3. Remote Sensing

3.3.1. Performance of the Matching Procedure

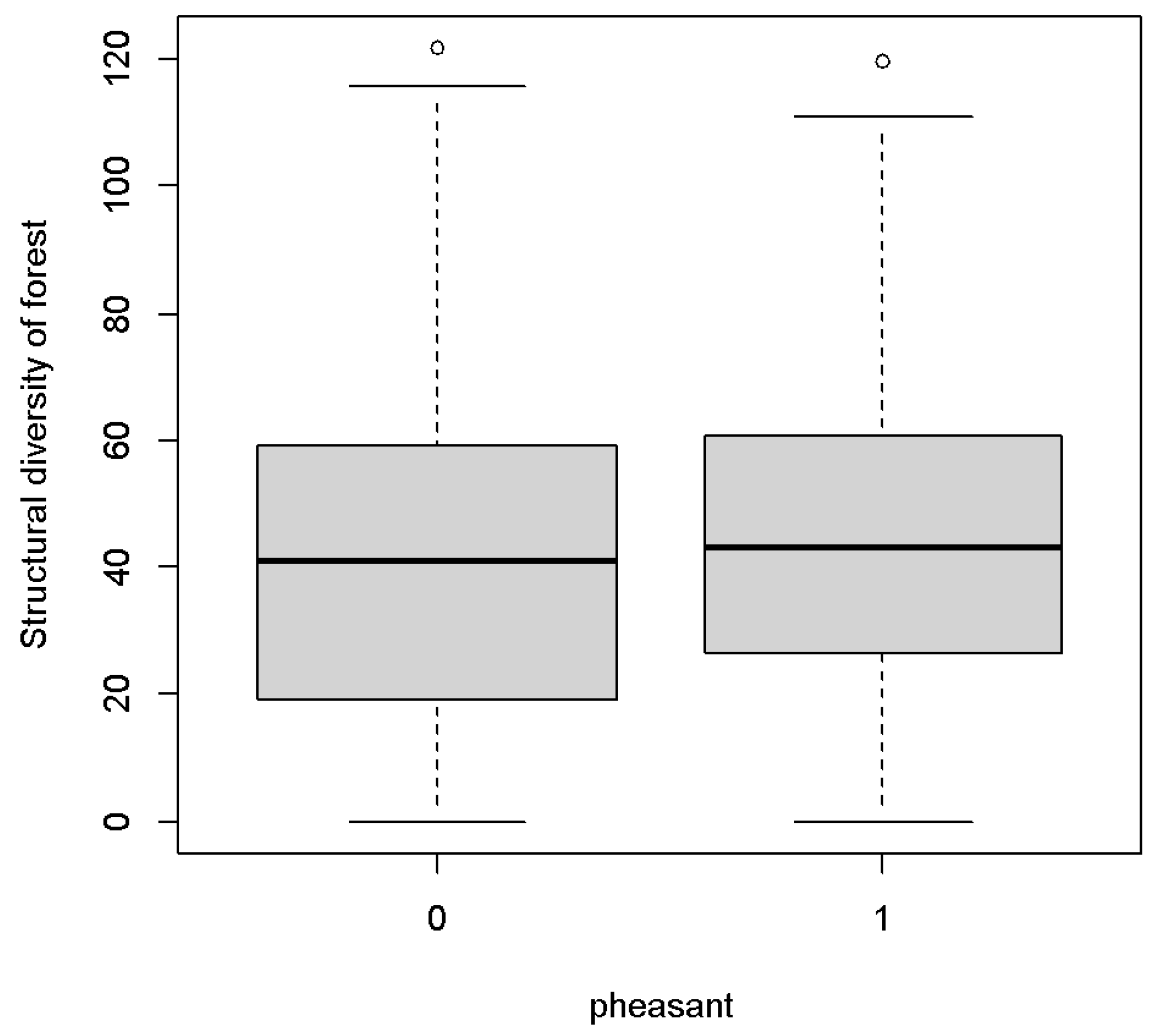

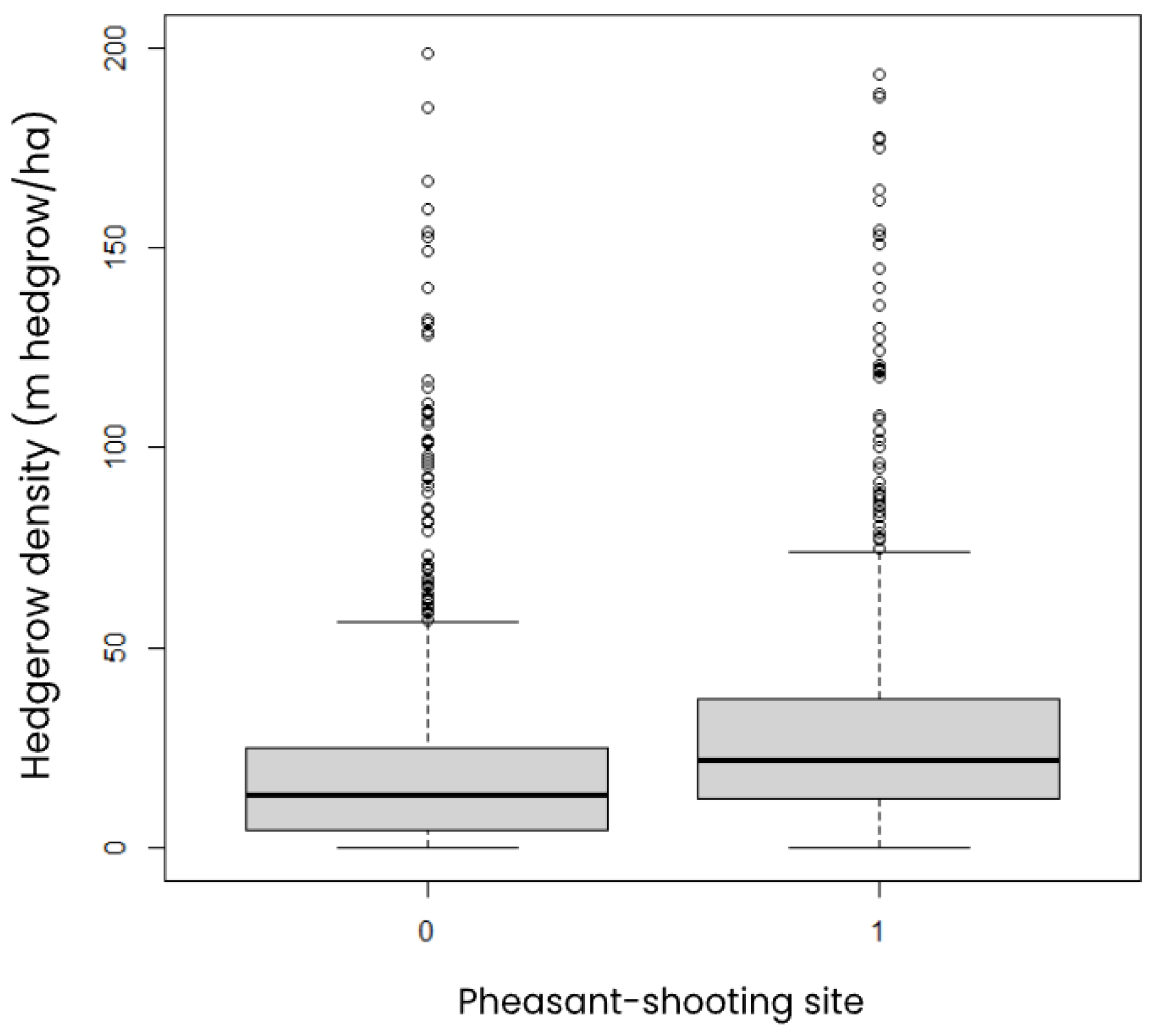

3.3.2. Habitat Quality

3.3.3. Biodiversity (Birds, Plants, Butterflies)

3.3.4. Differences Between Nations Within Great Britain

3.3.5. Effect of Size of Polygon Area

3.4. Limitations

3.4.1. Systematic Evidence Evaluation

3.4.2. Remote Sensing

4. Discussion

6.1. Extent and Composition of Forest, Margins, and Hedgerows

6.2. Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AONB – Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty |

| BASC – British Association for Shooting and Conservation |

| BACI – Before-After-Control-Intervention |

| BTO – British Trust for Ornithology |

| EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment |

| EU – European Union |

| GBIF – Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

| IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| JNCC – Joint Nature Conservation Committee |

| LD – Linear Dichroism |

| MPA – Marine Protected Area |

| NGO – Non-Governmental Organization |

| NVC – National Vegetation Classification |

| RSPB – Royal Society for the Protection of Birds |

| SAC – Special Area of Conservation |

| SPA – Special Protection Area |

| SSSI – Site of Special Scientific Interest |

| UK – United Kingdom |

| WWF – World Wide Fund for Nature |

Appendix A

Systematic Evidence Evaluation Protocol: Assessing the Quality and Quantity of Woodland and Hedgerow Habitats on Areas Managed for Shooting

- What is the existing evidence on the impact of pheasant shooting management on the quality and quantity of woodland and hedgerow habitats in the UK?

- How do management practices, such as pheasant release pens, affect woodland ecology, including biodiversity and habitat composition?

- What woodland and hedgerow management activities can improve or enhance ecological impacts on areas used for pheasant shooting?

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | Estates/land holdings with woodlands in the UK |

| Intervention | Pheasant shooting on the estate. |

| Comparator | Non-pheasant shooting site. |

| Outcome | Ecological impacts on habitat quality (e.g., biodiversity, species richness, habitat structure) and habitat quantity (e.g., extent of woodland and hedgerows). |

| Category | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Population: Woodland and Hedgerow Habitats in the UK | Studies focusing on ecological characteristics (e.g., biodiversity, structural composition, extent) of woodland and hedgerow habitats in the UK managed specifically for game shooting activities (specifically pheasant). | Studies focusing on non-UK habitats or areas where game shooting is not a central land management practice. Studies examining agricultural landscapes without substantial woodland or hedgerow components. |

| Intervention: Land Management Practices Associated with Game Shooting | Studies investigating specific land management practices for game shooting, such as pheasant release pens, woodland management for game species, or shooting-related interventions affecting woodland and hedgerow habitats. | Studies examining unrelated land management activities, such as purely agricultural practices or recreational land uses without a connection to shooting. |

| Comparator: Sites with Different Management Practices | Studies including comparisons with control sites where game shooting management is not conducted or where alternative land uses (e.g., conservation-only, agricultural without shooting) are implemented. | Studies without any form of comparator, including purely descriptive accounts of game shooting sites without comparison to non-shooting or differently managed sites. |

| Outcome: Ecological Impacts on Habitat Quality and Quantity | Studies assessing the impact of game shooting management on habitat quality (e.g., species richness, species abundance, community composition) or habitat quantity (e.g., extent of woodland or hedgerows) in the UK. | Studies focusing exclusively on economic, social, or non-ecological outcomes. Studies lacking an evaluation of woodland or hedgerow impacts on habitat quality. |

| Study Type: Qualitative and Empirical Studies | Qualitative and empirical studies, including peer-reviewed articles, reports, and grey literature (e.g., government reports, NGO publications) evaluating the impact of game shooting on woodland and hedgerow habitats. | Modelling studies using third party data, opinion pieces or anecdotal accounts without full methodological descriptions. |

Appendix B

| Article Number | Citation | Number of Studies |

| 1 | Robertson, P. A. and Woodburn, M. I. A. and Hill, D. A., 1988. The Effects Of Woodland Management For Pheasants On The Abundance Of Butterflies In Dorset, England. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 45(3), 159-167. 10.1016/0006-3207(88)90136-X | 1 |

| 2 | Sage, R. B. and Ludolf, C. and Robertson, P. A., 2005. The ground flora of ancient semi-natural woodlands in pheasant release pens in England. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 122(2), 243-252. 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.07.014 | 1 |

| 3 | Draycott, R. A. H. and Hoodless, A. N. and Sage, R. B., 2008. Effects of pheasant management on vegetation and birds in lowland woodlands. JOURNAL OF APPLIED ECOLOGY. 45(1), 334-341. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01379.x | 2 |

| 4 | Draycott, R. A. H. and Hoodless, A. N. and Cooke, M. and Sage, R. B., 2012. The influence of pheasant releasing and associated management on farmland hedgerows and birds in England. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WILDLIFE RESEARCH. 58(1), 227-234. 10.1007/s10344-011-0568-0 | 2 |

| 5 | Neumann, J. L. and Holloway, G. J. and Sage, R. B. and Hoodless, A. N., 2015. Releasing of pheasants for shooting in the UK alters woodland invertebrate communities. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 191, 50-59. 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.06.022 | 2 |

| 6 | Capstick, L. A. and Sage, R. B. and Hoodless, A., 2019. Ground flora recovery in disused pheasant pens is limited and affected by pheasant release density. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 231, 181-188. 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.12.020 | 1 |

| 7 | Madden, J. R. and Buckley, R. and Ratcliffe, S., 2023. Large-scale correlations between gamebird release and management and animal biodiversity metrics in lowland Great Britain. ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION. 13(5). 10.1002/ece3.10059 | 1 |

| 8 | Capstick, L., Draycott, R., Wheelwright, C., Ling, D., Sage, R. & Hoodless, A, 2019. The effect of game management on the conservation value of woodland rides. Forest Ecology and Management. | 1 |

| 9 | Greenall, T., 2007. Management of gamebird shooting in lowland Britain: Social attitudes, biodiversity benefits and willingness-to-pay. PhD Thesis, University of Kent., 296 pp. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/86403/ | 3 |

| 10 | Hall, A., Sage, R. A., & Madden, J. R., 2021. The effects of released pheasants on invertebrate populations in and around woodland release sites. Ecology and Evolution. 11, 13559–13569. | 1 |

| 11 | Hoodless, A. N. & Draycott, K., 2006. Effects of pheasant management at woodland edges. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 37, 30-31 | 1 |

| 12 | Hoodless, A. N., Lewis, R.,& Palmer, J., 2006. Songbird use of pheasant woods in winter. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 37, 28-29 | 1 |

| 13 | Hoodless, A., & Draycott, R., 2007. Pheasant releasing and woodland rides. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 38, 16-17 | 1 |

| 14 | Stoate, C., 2002. Multifunctional use of a natural resource on farmland: wild pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) management and the conservation of farmland passerines. Biodiversity and Conservation. 11, 561-573 | 1 |

| 15 | Pressland, C.L., 2009. The impact of releasing pheasants for shooting on invertebrates in british woodlands | 1 |

| 16 | Sage, R.B., 2017. Impacts of pheasant releasing for shooting on habitats and wildlife on the south Exmoor estates. Report, Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust | 1 |

| 17 | Sage, R. B. and Putaala, A. and Pradell-Ruiz, V. and Greenall, T. L. and Woodburn, M. I. A. and Draycott, R. A. H., 2003. Incubation success of released hand-reared pheasants Phasianus colchicus compared with wild ones. Wildlife Biology. 9(3), 179-184 | 1 |

| 18 | Sage, R. B. and Woodburn, M. I. A. and Draycott, R. A. H. and Hoodless, A. N. and Clarke, S., 2009. The flora and structure of farmland hedges and hedgebanks near to pheasant release pens compared with other hedges. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 142(7), 1362-1369. 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.01.034 | 1 |

| 19 | Aebischer, N. J. and Bailey, C. M. and Gibbons, D. W. and Morris, A. J. and Peach, W. J. and Stoate, C., 2016. Twenty years of local farmland bird conservation: the effects of management on avian abundance at two UK demonstration sites. BIRD STUDY. 63(1), 10-30. 10.1080/00063657.2015.1090391 | 1 |

| 20 | Sánchez-García, C. and Buner, F. D. and Aebischer, N. J., 2015. Supplementary winter food for gamebirds through feeders: Which species actually benefit?. JOURNAL OF WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT. 79(5), 832-845. 10.1002/jwmg.889 | 4 |

| 21 | Sage, R. and Woodburn, M. and McCready, S. and Coomes, J., 2024. Winter game crop plots for gamebirds retain hedgerow breeding songbirds in an improved grassland landscape. WILDLIFE BIOLOGY. 2024(3). 10.1002/wlb3.01156 | 1 |

| 22 | Blake, D., 1996. What effects do releasing pheasants have on the ground flora of woodland rides?. WPA News. 50, 11-14 | 1 |

| 23 | Swan, G. J., Bearhop, S., Redpath, S. M., Silk, M. J., Padfield, D., Goodwin, C. E., & McDonald, R. A., 2022. Associations between abundances of free-roaming gamebirds and common buzzards Buteo buteo are not driven by consumption of gamebirds in the buzzard breeding season. Ecology and Evolution. 12, e8877. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8877 | 1 |

| Species Studied | Common Name | Taxonomic Group | Status | Increased Presence | Decreased Presence | No Difference | Total | Article Number |

| Abax parallelepipedus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Acupalpus meridianus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Agonum marginatum | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Amara aenea | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Amarasimilata | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Asaphidion curtum | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Asaphidion flavipes | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Badister bipustulatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Bembidion harpaloides | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Bembidion lampros | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Bembidion obtusum | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Calathus fuscipes | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Calathus melanocephalus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Calathus rotundicollis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carabus arvensis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carabus monilis | Necklace Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Priority Species | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carabus nemoralis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carabus problematicus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Carabus violaceus | Violet Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Clivina fossor | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Cychrus caraboides | Snail Hunter Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Dromius agilis | Agile Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Harpalus latus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Harpalus rufipes | Strawberry Seed Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Leistus ferrugineus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Leistus fulvibarbis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Leistus rufomarginatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Leistus spinibarbis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Leistus terminatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Loricera pilicornis | Springtail Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Nebria brevicollis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Nebria salina | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Notiophilus biguttatus | Two-spotted Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Patrobus atrorufus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pieris napi | Green-veined White | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1, 9 |

| Platynus assimilis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus cupreus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus diligens | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus macer | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus madidus | Black Clock Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus melanarius | Black Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus minor | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichusniger | Large Black Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus nigrita | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus oblongopunctatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Pterostichus strenuus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Stomis pumicatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Synuchus vivalis | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Trechus obtusus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Trechus quadristriatus | Ground Beetle | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Bombus lapidaries | Red-tailed Bumblebee | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Bombus lucorum | White-tailed Bumblebee | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Bombus pascuorum | Common Carder Bumblebee | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Bombus terrestris | Buff-tailed Bumblebee | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Maniola jurtina | Meadow Brown | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Pieris brassicae | Large White | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Pieris rapae | Small White | Aboveground Invertebrates | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Pica pica | Eurasian Magpie | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4, 7, 14 |

| Columba palumbus | Common Wood Pigeon | Birds | Bird-Amber | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3, 4, 12 |

| Phylloscopus trochilus | Willow Warbler | Birds | Bird-Amber | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3, 4, 14 |

| Regulus regulus | Goldcrest | Birds | Least Concern | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 3, 4, 12 |

| Sylvia atricapilla | Blackcap | Birds | Least Concern | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3, 4, 14 |

| Sylvia communis | Common Whitethroat | Birds | Least Concern | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3, 4, 14 |

| Erithacus rubecula | European Robin | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4, 12, 14 |

| Fringilla coelebs | Chaffinch | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 4, 12, 14 |

| Prunella modularis | Dunnock | Birds | Bird-Amber | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4, 12, 14 |

| Troglodytes troglodytes | Eurasian Wren | Birds | Bird-Amber | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4, 12, 14 |

| Carduelis cannabina | Common Linnet | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Carduelis carduelis | European Goldfinch | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Carduelis chloris | European Greenfinch | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Corvus corone | Carrion Crow | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4, 7 |

| Parus caeruleus | Eurasian Blue Tit | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Parus major | Great Tit | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Sylvia borin | Garden Warbler | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3, 14 |

| Turdus merula | Common Blackbird | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4, 14 |

| Aegithalos caudatus | Long-tailed Tit | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Anthus trivialis | Tree Pipit | Birds | Bird-Red | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Athene noctua | Little Owl | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Corvus frugilegus | Rook | Birds | Bird-Amber | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Dendrocopos major | Great Spotted Woodpecker | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Emberiza citronella | Yellowhammer | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Falco tinnunculus | Common Kestrel | Birds | Bird-Amber | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Garrulus glandarius | Eurasian Jay | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Hirundo rustica | Barn Swallow | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Motacilla flava | Western Yellow Wagtail | Birds | Bird-Red | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Perdix perdix | Grey Partridge | Birds | Bird-Red | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Phylloscopus collybita | Common Chiffchaff | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Picus viridis | European Green Woodpecker | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Poecile palustris | Marsh Tit | Birds | Bird-Red | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Pyrrhula pyrrhula | Eurasian Bullfinch | Birds | Bird-Amber | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Sylvia curruca | Lesser Whitethroat | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Turdus philomelus | Song Thrush | Birds | Least Concern | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Alauda arvensis | Skylark | Birds | Bird-Red | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| Buteo buteo | Common Buzzard | Birds | Least Concern | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Corvus monedula | Western Jackdaw | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 |

| Emberiza citrinella | Yellowhammer | Birds | Bird-Red | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Regulus ignicapilla | Firecrest | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Sitta europaea | Eurasian Nuthatch | Birds | Least Concern | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 |

| Sciurus carolinensis | Eastern Grey Squirrel | Mammals | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Vulpes vulpes | Red Fox | Mammals | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Hedera helix | Common Ivy | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Hyacinthoides non-scripta | English Bluebell | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Lamium galeobdolon | Yellow Archangel | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Mercurialis perennis | Dog's Mercury | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Rubus fruticosus | Blackberry | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Rumex obtusifolius | Broad-leaved Dock | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Tripleurospermum inodorum | Scentless Mayweed | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

| Urtica dioica | Stinging Nettle | Vascular Plants | Non-Priority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 |

References

- Mason, L.R., Bicknell, J.E., Smart, J. and Peach, W.J., 2020. The impacts of non-native gamebird release in the UK: an updated evidence review. Report 66. RSPB Centre Conserv Sci, Sandy, UK. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345717757_The_impacts_of_non-native_gamebird_release_in_the_UK_an_updated_evidence_review (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Sage, R.B., Hoodless, A.N., Woodburn, M.I., Draycott, R.A., Madden, J.R. and Sotherton, N.W., 2020. Summary review and synthesis: Effects on habitats and wildlife of the release and management of pheasants and red-legged partridges on UK lowland shoots. Wildlife Biology, 2020(4), pp.1-12. [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, J., Smart, J., Hoccom, D., Amar, A., Evans, A., Walton, P., Knott, J. and Lodge, T., 2010. Impacts of non-native gamebird release in the UK: a review. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Bedfordshire.

- Madden, J.R. and Sage, R.B., 2020. Ecological consequences of gamebird releasing and management on lowland shoots in England. Natural England report.(NEER016) https://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/5078605686374400 (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Madden, J.R., Buckley, R. and Ratcliffe, S., 2023. Large-scale correlations between gamebird release and management and animal biodiversity metrics in lowland Great Britain. Ecology and Evolution, 13(5), p.e10059. [CrossRef]

- Pullin, A.S., Cheng, S.H., Cooke, S.J., Haddaway, N.R., Macura, B., Mckinnon, M.C. and Taylor, J.J., 2020. Informing conservation decisions through evidence synthesis and communication. Conservation research, policy and practice, pp.114-28.

- Konno, K. and Pullin, A.S., 2020. Assessing the risk of bias in choice of search sources for environmental meta-analyses. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(5), pp.698-713. [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R., Bernes, C., Jonsson, B.G. Hedlund, K. 2016. The benefits of systematic mapping to evidence-based environmental management. Ambio 45 (2016): 613-620. [CrossRef]

- Collins, A., Coughlin, D., Miller, J. and Kirk, S., 2015. The production of quick scoping reviews and rapid evidence assessments: A how to guide. https://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/512448/ (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Farella M.M; Fisher J.B, Jiao W, Kely K.B, Barnes, M.L. 2022 Thermal remote sensing for plant ecology from leaf to globe. Journal of Ecology 00: 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J., Schnieder, F.D., Santos, M.J., Armstrong, A., Carnaval, A., Dahlin, K.M., Fatoyinbo, L., Hurt, G.C., Schimel, D., Townsend, P.A., Ustin, S.L., Wang, Z., Wilson, A.M. 2022 Integrating remote sensing with ecology and evolution to advance biodiversity conservation. Nature Ecology and Evolution. [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, A.K., Laliberte, E. 2022 Plant beta-diversity across biomes captured by imaging spectroscopy. Nature Communications. 13: 2767. [CrossRef]

- Lines, E.R., Fischer, F.J., Foord Owen, H.J., Jucker, T. 2022 The shape of trees: reimagining forest ecology in three dimensions with remote sensing. Journal of Ecology 00: 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P., Li, X., Hernandez-Serna, A., Tyukavina, A., Hansen, M., Kommareddy, A., Pickens, A., Turubanova, A., Tang, H., Silva, C.E., Armston, J., Dubayah, R., Blair, J.B., Hofton, M. 2020 Mapping global forest canopy height through integration of GEDI and Landsat data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 112165. [CrossRef]

- BASC, 2025. Green shoots mapping. Available online: https://basc.org.uk/conservation-in-action/green-shoots-mapping/ (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Office for National Statistics, 2025. Administrative geographies. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/ukgeographies/administrativegeography&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1748598873027847&usg=AOvVaw3a_Ai2BSGPWAOWIpHGtv05 (accessed 30/05/2025).

- HM Land Registry, 2021. Index polygons spatial data (INSPIRE). Available Online: https://use-land-property-data.service.gov.uk/datasets/inspire/download (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Registers of Scotland, 2025. Land Register of Scotland, Available online: https://www.ros.gov.uk/our-registers/land-register-of-scotland (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Ordnance Survey, 2025. OS Open Built Up Areas. Available online: https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/products/os-open-built-up-areas (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Hansen, M.C. et al., 2013. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342, 850-853. [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G., et al. 2007. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, Rev. Geophys., 45, RG2004. [CrossRef]

- Ho, D., Imai, K., King, G. and Stuart, E.A., 2011. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. Journal of statistical software, 42, pp.1-28. [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.R., Buckley, R. and Ratcliffe, S., 2023. Large-scale correlations between gamebird release and management and animal biodiversity metrics in lowland Great Britain. Ecology and Evolution, 13(5), p.e10059. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, M., Beer, C., Cartus, O., Schmullius, C., Shvidenko, A., McCallum, I., Wegmüller, U. and Wiesmann, A., 2011. Retrieval of growing stock volume in boreal forest using hyper-temporal series of Envisat ASAR ScanSAR backscatter measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment, 115(2), pp.490-507. [CrossRef]

- Scholefield, P.A., Morton, R.D., Rowland, C.S., Henrys, P.A., Howard, D.C. and Norton, L.R., 2016. Woody linear features framework, Great Britain v. 1.0. NERC Environmental Information Data Centre (Dataset).

- Oksanen, J., Simpson, G.L., Blanchet, F.G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P.R., O'Hara, R.B., Solymos, P., Stevens, M.H.H., Szoecs, E. and Wagner, H., 2022. vegan: Community ecology package (2.6-4). CRAN.

- Macarthur R.H., & Wilson, E. O. (1967). The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt19cc1t2 (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Rosenzweig, M.L. 1995. Species diversity in space and time. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Long, P.R., Benz, D., Macias-Fauria, M., Seddon, A.W.R., Holland, P.W.A., Martin, A.C., Hagemann, R., Frost, T.K., Simpson, A.C., Power, D.J., Slaymaker, M.A., Willis, K.J. 2017 LEFT – a web-based tool for the remote measurement and estimation of ecological value across global landscapes. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9: 571-579.

- Draycott, R.A.H., Hoodless, A.N., Cooke, M., and Sage, R. B., 2012. The influence of pheasant releasing and associated management on farmland hedgerows and birds in England. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF WILDLIFE RESEARCH. 58(1), 227-234. [CrossRef]

- Hoodless, A., & Draycott, R., 2007. Pheasant releasing and woodland rides. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 38, 16-17.

- Stoate, C., 2002. Multifunctional use of a natural resource on farmland: wild pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) management and the conservation of farmland passerines. Biodiversity and Conservation. 11, 561-573. [CrossRef]

- Sage, R.B., 2018. Impacts of pheasant releasing for shooting on habitats and wildlife on the south Exmoor estates. Report, Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust.

- Robertson, P. A. and Woodburn, M. I. A. and Hill, D. A., 1988. The Effects Of Woodland Management For Pheasants On The Abundance Of Butterflies In Dorset, England. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 45(3), 159-167. [CrossRef]

- Draycott, R. A. H. and Hoodless, A. N. and Sage, R. B., 2008. Effects of pheasant management on vegetation and birds in lowland woodlands. JOURNAL OF APPLIED ECOLOGY. 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Hoodless, A. N., Lewis, R.,& Palmer, J., 2006. Songbird use of pheasant woods in winter. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 37, 28-29.

- Hoodless, A. N. & Draycott, K., 2006. Effects of pheasant management at woodland edges. The Game Conservancy Trust Review. 37, 30-31.

- Greenall, T., 2007. Management of gamebird shooting in lowland Britain: Social attitudes, biodiversity benefits and willingness-to-pay. PhD Thesis, University of Kent., 296 pp. Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/86403/ (accessed 30/05/2025).

- Hall, A., Sage, R. A., & Madden, J. R., 2021. The effects of released pheasants on invertebrate populations in and around woodland release sites. Ecology and Evolution. 11, 13559–13569.

- Sage, R. B. and Ludolf, C. and Robertson, P. A., 2005. The ground flora of ancient semi-natural woodlands in pheasant release pens in England. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 122(2), 243-252. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.L., Holloway, G.J., Sage, R.B. and Hoodless, A.N., 2015. Releasing of pheasants for shooting in the UK alters woodland invertebrate communities. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 191, 50-59.

- Capstick, L. A. and Sage, R. B. and Hoodless, A., 2019. Ground flora recovery in disused pheasant pens is limited and affected by pheasant release density. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. [CrossRef]

- Capstick, L., Draycott, R., Wheelwright, C., Ling, D., Sage, R. & Hoodless, A, 2019. The effect of game management on the conservation value of woodland rides. Forest Ecology and Management. [CrossRef]

- Pressland, C.L., 2009. The impact of releasing pheasants for shooting on invertebrates in british woodlands.

- Livoreil, B., Glanville, J., Haddaway, N.R., Bayliss, H., Bethel, A., de Lachapelle, F.F., Robalino, S., Savilaakso, S., Zhou, W., Petrokofsky, G. and Frampton, G., 2017. Systematic searching for environmental evidence using multiple tools and sources. Environmental Evidence, 6(1), pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Päivinen, R., Petrokofsky, G., Harvey, W.J., Petrokofsky, L., Puttonen, P., Kangas, J., Mikkola, E., Byholm, L. and Käär, L., 2023. State of forest research in 2010s–a bibliographic study with special reference to Finland, Sweden and Austria. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 38(1-2), 23-38.

- Altman, D.G. Mathematics for kappa. Pract. Stat. Med. Res. 1991, 1991, 406–407.

- Frampton, G.K., Livoreil, B. and Petrokofsky, G., 2017. Eligibility screening in evidence synthesis of environmental management topics. Environmental Evidence, 6, pp.1-13. 10.1186/s13750-017-0102-2.

- Stanbury, A., Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Balmer, D., Brown, A., Douse, A., Lindley, P., McCulloch, N., Noble, D. and Win, I., 2021. The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain. British Birds, 114, pp.723-747.

| Region | No. sites managed for shooting - Remote sensing | No. comparison sites - Remote sensing |

No. sites managed for shooting - Literature review | No. comparison sites - Literature review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Midlands England | 117 | 117 | 5 | 5 |

| East of England | 152 | 152 | 214 | 119 |

| Northeast England | 42 | 42 | 1 | 1 |

| Northwest England | 79 | 79 | 1 | 1 |

| Scotland | 98 | 98 | 1 | 1 |

| Southeast England | 213 | 213 | 333 | 299 |

| Southwest England | 183 | 183 | 109 | 80 |

| Wales | 51 | 51 | 1 | 1 |

| West Midlands England | 118 | 118 | 15 | 15 |

| Yorkshire Humber England | 78 | 78 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 1131 | 1131 | 681 | 523 |

| Taxonomic Groups Studied | Count of studies |

| Birds | 21 |

| Aboveground invertebrates | 10 |

| Vascular plants | 8 |

| Mammals | 6 |

| Soil invertebrates | 3 |

| Herptiles | 1 |

| Bryophytes | 1 |

| Non-vascular plants | 1 |

| Fungi | 0 |

| Variable | Region | Mean pheasant sites | Mean comparison sites | t | p | n (each group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | East Midlands England | 242 | 236 | -0.185 | 0.8526 | 117 |

| East of England | 254 | 254 | 0.0061 | 0.9951 | 152 | |

| Northeast England | 320 | 227 | -1.0544 | 0.2952 | 42 | |

| Northwest England | 295 | 146 | -2.6965 | 0.0077 | 79 | |

| Scotland | 495 | 335 | -1.5405 | 0.1251 | 98 | |

| Southeast England | 228 | 231 | 0.13319 | 0.8941 | 213 | |

| Southwest England | 277 | 207 | -1.1246 | 0.2618 | 183 | |

| Wales | 47 | 230 | -4.984 | 0.0001 * | 51 | |

| West Midlands England | 258 | 234 | -0.5002 | 0.6176 | 118 | |

| Yorkshire Humber England | 270 | 216 | -0.9042 | 0.3673 | 78 | |

| Elevation (m) | East Midlands England | 90 | 106 | 1.2901 | 0.1987 | 117 |

| East of England | 50 | 50 | 0.09639 | 0.9233 | 152 | |

| Northeast England | 142 | 143 | 0.037499 | 0.9702 | 42 | |

| Northwest England | 101 | 115 | 0.89397 | 0.3727 | 79 | |

| Scotland | 161 | 156 | -0.25507 | 0.799 | 98 | |

| Southeast England | 82 | 88 | 1.3539 | 0.1765 | 213 | |

| Southwest England | 115 | 120 | 0.59739 | 0.5507 | 183 | |

| Wales | 105 | 93 | -0.81658 | 0.4161 | 51 | |

| West Midlands England | 113 | 127 | 1.4657 | 0.1444 | 118 | |

| Yorkshire Humber England | 107 | 124 | 0.95971 | 0.3387 | 78 | |

| Forest 2010 (proportion) | East Midlands England | 0.08 | 0.13 | 2.0952 | 0.03732 | 117 |

| East of England | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09091 | 0.9276 | 152 | |

| Northeast England | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.74704 | 0.4572 | 42 | |

| Northwest England | 0.14 | 0.27 | 3.7205 | 0.0002 * | 79 | |

| Scotland | 0.18 | 0.14 | -1.9579 | 0.051 | 98 | |

| Southeast England | 0.11 | 0.19 | 2.7658 | 0.00661 | 213 | |

| Southwest England | 0.15 | 0.25 | 3.7327 | 0.0002 * | 183 | |

| Wales | 0.15 | 0.3 | 3.3726 | 0.0011 * | 51 | |

| West Midlands England | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.8982 | 0.37 | 118 | |

| Yorkshire Humber England | 0.11 | 0.19 | 2.7658 | 0.006 | 78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).