Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa), one of the most commonly diagnosed malignancies in men, is a major global health issue, ranking as the second most prevalent cancer worldwide, with a generally favorable prognosis when detected at an early stage [

1]. Early-stage PCa refers to tumors that are confined to the prostate gland and have not spread to nearby tissues or distant organs [

2]. PCa is prevalent among older men. The increasing utilization of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) testing and the extension of life expectancy have led to a higher incidence of PCa diagnoses in this population [

3]. However, prognosis can vary significantly among patients diagnosed at the same stage. This difference is attributed to factors such as tumor biology, the patient's overall health condition, nutritional status, and inflammatory levels [

4]. In particular, in elderly patients, impaired immune function and malnutrition play a crucial role in cancer progression. The immune system in older patients naturally weakens with the aging process, which can accelerate cancer progression. Additionally, malnutrition can trigger an inflammatory response that may promote tumor growth, negatively affecting the patient’s response to treatment [

5]. The management of prostate cancer in elderly patients should not only be based on clinical staging but also consider these factors in the treatment approach. Therefore, the heterogeneity of the elderly population necessitates a comprehensive assessment to maximize the benefit of medical and/or surgical options. Considering the essential health status data to inform treatment decisions is crucial in ensuring that elderly patients with prostate cancer receive optimal therapy when beneficial, or, when not, appropriate management through active surveillance or best supportive care [

6].

Some patients with early-stage prostate cancer, particularly those who are elderly and have comorbidities, can be managed with active surveillance instead of immediate treatment. Therefore, additional prognostic indicators are necessary to determine whether active surveillance or definitive treatment would be the most appropriate approach for these patients. The Prognostic Nutrition Index (PNI) and Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) are biochemical markers that provide valuable insights into the nutritional and inflammatory status of patients [

7]. These indices are increasingly recognized for their role in predicting clinical outcomes, as they integrate factors such as serum albumin levels and lymphocyte counts, which are indicative of both nutritional status and immune function [

8]. In the literature, several studies have demonstrated that low PNI and GNRI values are associated with poorer prognosis and shorter survival in various cancer types, including colorectal, gastroesophageal, and pancreatic cancers [

9,

10,

11]. Specifically, a reduced PNI has been correlated with elevated mortality rates in cancer patients, as it reflects both malnutrition and systemic inflammation—two key factors that can negatively affect tumor progression and diminish the efficacy of treatment responses [

12]. Similarly, reduced GNRI values have been shown to predict worse survival outcomes in elderly cancer patients, highlighting its potential as an important prognostic marker in oncology [

13]. Furthermore, several studies have explored the feasibility of GNRI as a novel parameter for diagnosing frailty, particularly in surgical patients. Frailty, common among older adults, is associated with a higher risk of postoperative complications, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality [

14]. GNRI, by incorporating both nutritional status and inflammatory markers, has shown promise in identifying frailty, providing valuable information for preoperative risk assessment and personalized treatment strategies [

15]. Both PNI and GNRI have emerged as important biomarkers in clinical practice, particularly in oncology and geriatric care. Their ability to reflect the interplay between nutrition, inflammation, and overall health makes them invaluable tools in predicting patient outcomes and guiding treatment decisions.

However, the prognostic significance of these indices in early-stage PCa has yet to be thoroughly investigated. As personalized treatment approaches in oncology continue to gain prominence, the integration of these indices could provide substantial contributions to clinical decision-making processes. This study aims to investigate the association between the PNI and GNRI with survival outcomes in elderly patients diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer. Our hypothesis posits that low PNI and GNRI values will correlate with reduced survival outcomes, and that these indices may serve as valuable prognostic markers. It is anticipated that the results of this study will offer further insights into risk stratification in the management of prostate cancer, contributing to more refined clinical decision-making and aiding in the development of targeted supportive interventions for high-risk patients.

Material and Method

This retrospective study included 205 patients aged 65 years and older who were diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer between January 2018 and December 2024. Early-stage disease was defined as tumors confined to the prostate gland (clinical stage T1–T2) without regional or distant metastasis. Patients with metastatic disease, incomplete laboratory data, or a prior history of another malignancy were excluded from the study. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data at the time of diagnosis were collected from electronic medical records. These included age, Gleason score, PSA levels, tumor stage, radiotherapy status, body weight, serum albumin levels, and total lymphocyte count.

Nutritional status was assessed using the PNI and the GNRI.

PNI was calculated using the formula: 10 × serum albumin (g/dL) + 0.005 × total lymphocyte count (cells/μL).

GNRI was calculated as: 14.89 × serum albumin (g/dL) + 41.7 × (actual body weight / ideal body weight).

Ideal body weight was estimated using the Lorentz formula [

16]. All measurements were obtained from baseline laboratory and anthropometric data at the time of diagnosis.

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the following clinical parameters:

Age groups (65–75 years vs. 75–85 years)

Gleason score (<8 vs. ≥8)

PSA levels (<10 ng/mL vs. ≥10 ng/mL)

Tumor stage (T1 vs. T2)

Radiotherapy status (received vs. not received)

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and comparisons between survival curves were made using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to identify independent prognostic factors affecting overall survival. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. To determine the optimal cut-off values for PNI and GNRI, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess their discriminatory power. Additionally, clinical factors such as age, baseline PSA, and GNRI were analyzed using ROC curves to establish new threshold values for prognostic factors. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0.

Results

Among the 205 patients included in the study, the median age was 72 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 68–78), with 84 patients (41%) aged 75 years or older.

Figure 3 illustrates the subgroup analysis of patients with early-stage prostate cancer, categorized according to key clinical factors: Age groups (65–75 vs. 75–85 years), Gleason score (<8 vs. ≥8), PSA levels (<10 ng/mL vs. ≥10 ng/mL), tumor stage (T1 vs. T2), and radiotherapy status (received vs. not received). In patients aged 65-75 years, the median survival was 110 months, whereas in patients aged 75-85 years, the median survival decreased to 85 months (p = 0.005). The median survival for patients who received local radiotherapy was 122 months, compared to 94 months in those who did not receive radiotherapy (p = 0.008). Patients with a Gleason score ≥8 had a significantly shorter median survival of 72 months (p < 0.001). Regarding tumor burden, patients with T1 tumors exhibited the longest survival, while those with T2 tumors had shorter survival durations. Specifically, in patients with T1 tumors and low PSA levels, the median survival was 130 months, whereas in patients with T2 tumors or high PSA levels, the median survival was 76 months (p < 0.001). High PSA levels (≥10 ng/mL) were identified as an independent prognostic factor negatively impacting survival (HR = 1.82, 95% CI: 1.30–2.55, p = 0.002). The median survival of patients with low PSA levels was 125 months, whereas in those with high PSA levels, the median survival decreased to 85 months (p < 0.001).

Table 1 displays the patient subgroup analysis, which was conducted based on several key clinical factors. These subgroup analyses were performed to evaluate the survival outcomes and their association with these clinical variables in patients with early-stage prostate cancer.

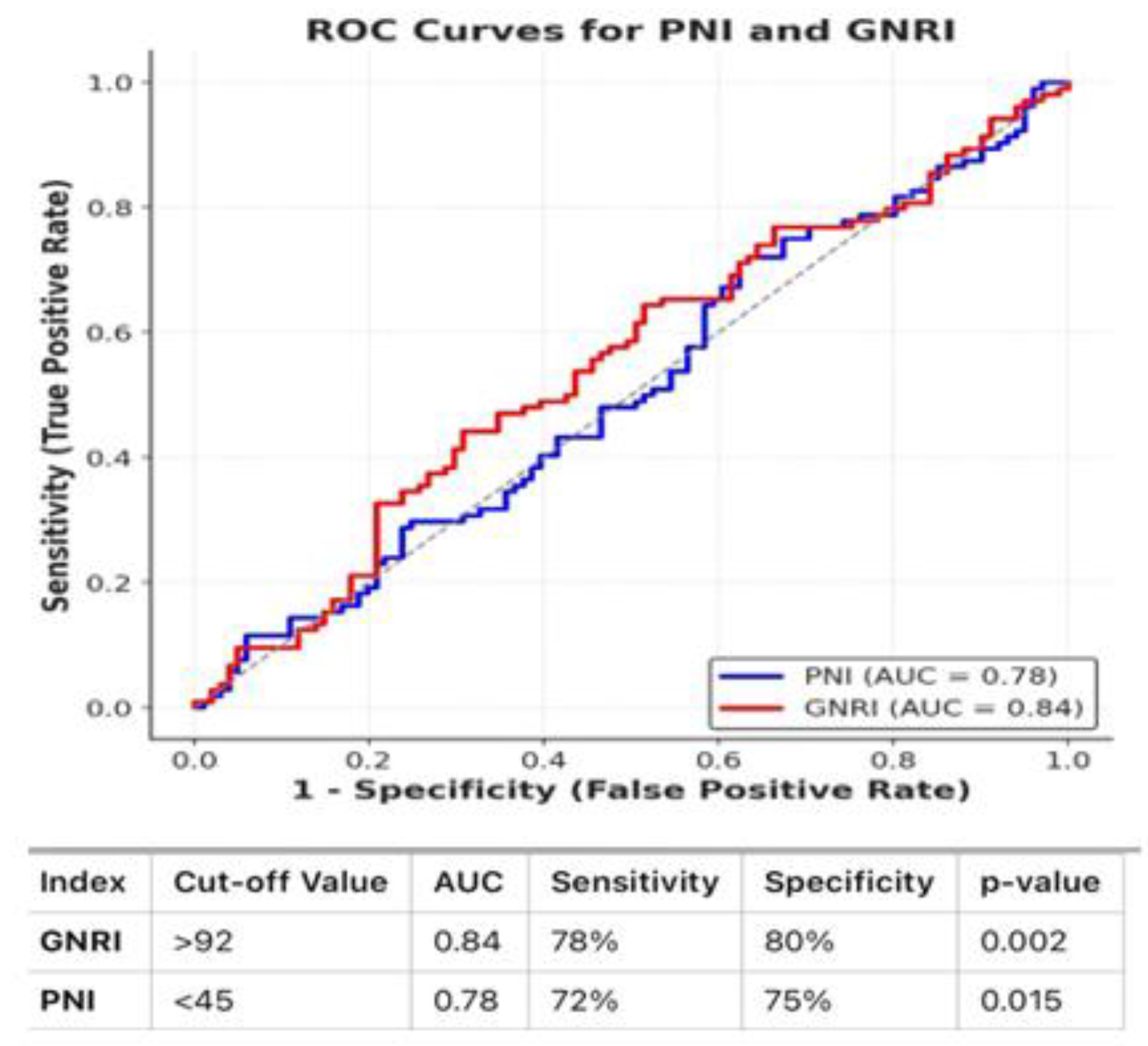

The median PNI and GNRI values were 48.2 (interquartile range [IQR]: 44.5–52.6) and 95.4 (IQR: 89.2–101.8), respectively. The median survival for patients with a low PNI value (<45) was 78 months, while those in the high PNI group (≥45) had a median survival of 115 months (p = 0.015). Similarly, the median survival for patients with low GNRI values was 74 months, whereas the high GNRI group (≥92) had a median survival of 120 months (p = 0.002). The area under the curve (AUC) for PNI was 0.78, with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 75%, while for GNRI, the AUC was 0.84, with a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 80%. Additionally, the Log-Rank test for PNI groups (χ² = 6.89, p = 0.008) and for GNRI groups (Log-Rank test: χ² = 6.72, p = 0.009) demonstrated statistical significance.

Figure 1 presents the ROC curves and AUC values for PNI and GNRI. The PNI ROC curve showed an AUC of 0.78, with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 75%. The GNRI ROC curve demonstrated an AUC of 0.84, with a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 80%.

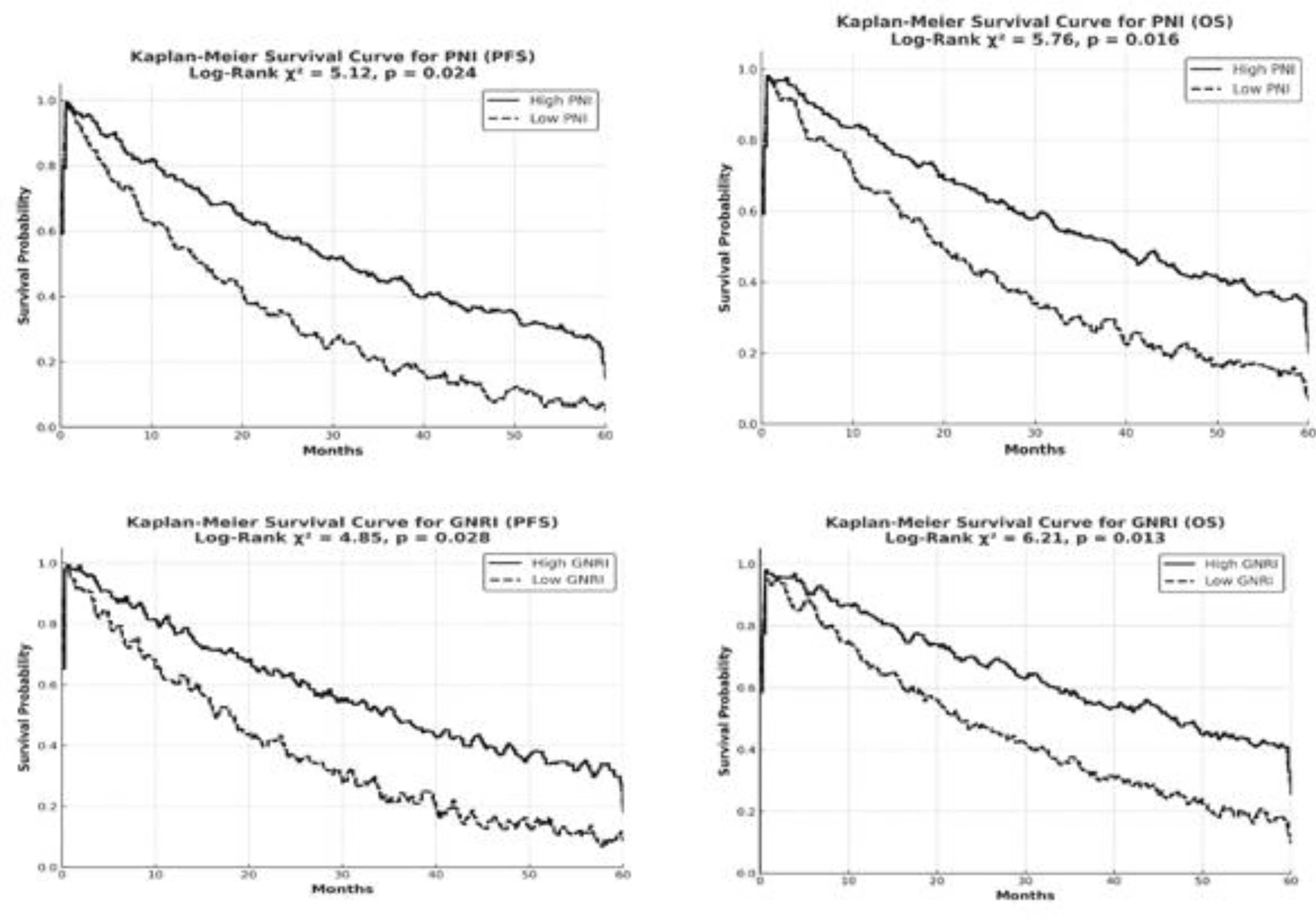

Kaplan-Meier analyses further illustrated the statistical significance of the difference in survival times between the low and high GNRI and PNI groups.

Figure 2 presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank test results for the high and low PNI (≥45/<45) and GNRI (≥92/<92) groups in elderly patients with early-stage PCa. The multivariate analysis confirmed that both PNI and GNRI are independent prognostic factors. Low PNI and low GNRI were identified as independent prognostic factors, with both being associated with a negative impact on survival outcomes. Patients with stage T2 tumor exhibited a 1.75-fold increased risk of mortality compared to those with stage T1 tumor (HR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.23–2.48, p = 0.004). The risk of mortality was found to be significantly higher in patients who did not receive local radiotherapy compared to those who underwent radiotherapy (HR = 1.55, p = 0.015).

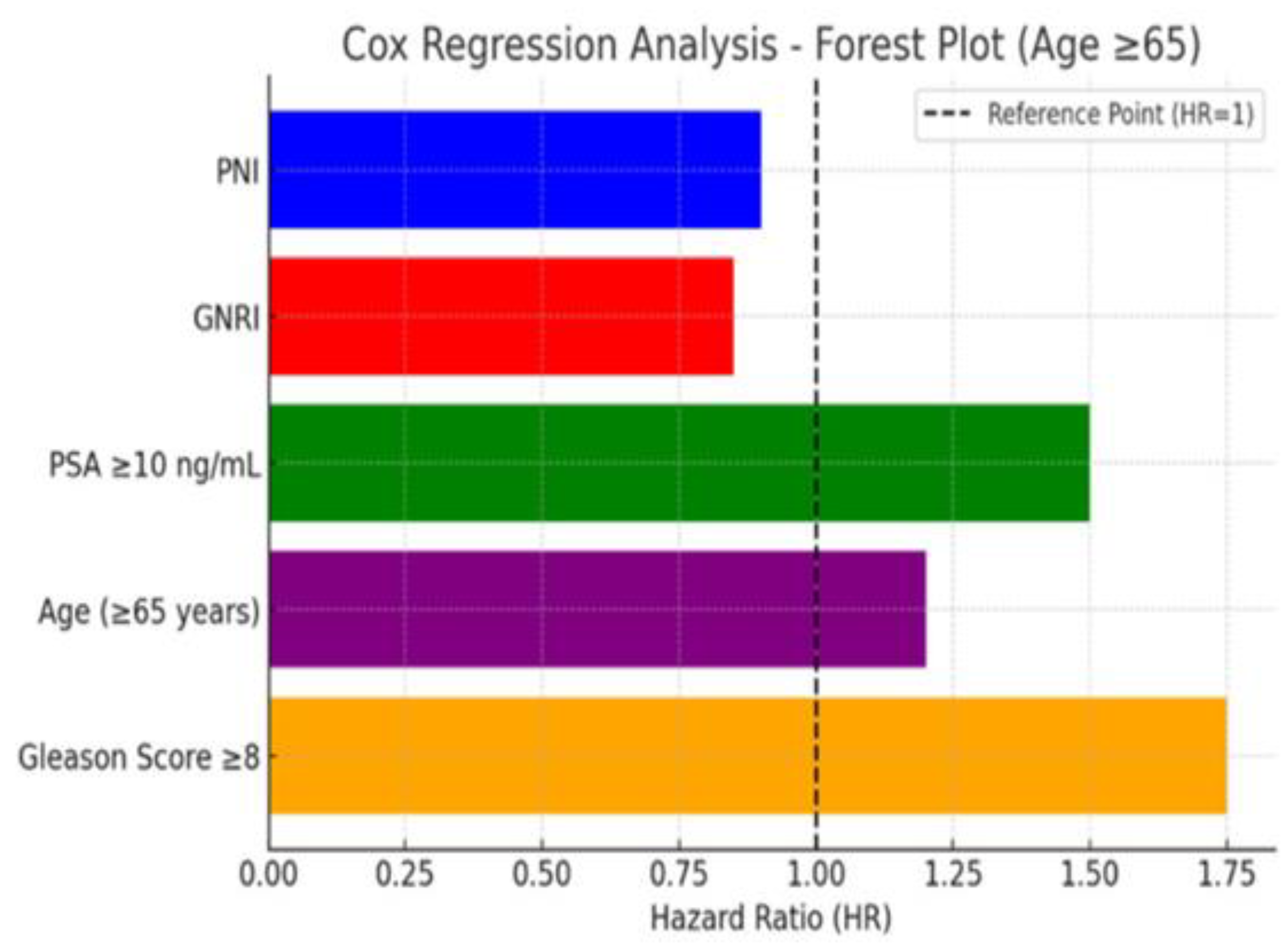

Figure 3 presents the COX regression analysis in the form of a forest plot, illustrating the effect of each variable on survival. Variables with a hazard ratio (HR) greater than 1 are identified as factors that negatively impact survival.

Figure 2.

İllustrates the Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing high (≥45 for PNI, ≥92 for GNRI) and low (<45 for PNI, <92 for GNRI) groups in elderly prostate cancer patients.Higher PNI and GNRI values are associated with longer survival, while lower values predict shorter survival (p = 0.015 for PNI, p = 0.002 for GNRI).The log-rank test confirms significant differences between the groups (χ² = 6.89 for PNI, χ² = 6.72 for GNRI).

Figure 2.

İllustrates the Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing high (≥45 for PNI, ≥92 for GNRI) and low (<45 for PNI, <92 for GNRI) groups in elderly prostate cancer patients.Higher PNI and GNRI values are associated with longer survival, while lower values predict shorter survival (p = 0.015 for PNI, p = 0.002 for GNRI).The log-rank test confirms significant differences between the groups (χ² = 6.89 for PNI, χ² = 6.72 for GNRI).

Figure 3.

COX Regression analysis, forest plot;this graph shows the effect of each variable on survival. Variables with HR > 1 are factors that negatively affect survival.

Figure 3.

COX Regression analysis, forest plot;this graph shows the effect of each variable on survival. Variables with HR > 1 are factors that negatively affect survival.

Discussion

Malnutrition is a significant issue in the geriatric age group and is associated with protein deficiency and energy imbalance, which can lead to cachexia and death [

17]. Prostate cancer, although generally considered a slow-progressing disease in its early stages, requires attention not only to tumor characteristics but also to the patient's overall health condition when making treatment decisions for elderly patients. Elderly patients are often affected by factors such as comorbidities, sarcopenia, and malnutrition [

18]. The relationship between nutritional status and inflammation holds significant importance in cancer prognosis. Malnutrition is a significant issue in the geriatric group that is not sufficiently recognized, and its relationship with disease is increasingly drawing attention [

19]. Low PNI and GNRI values are associated with the weakening of the immune system and an increase in inflammatory processes [

20]. Since albumin and lymphocyte levels indicate the body's immune response and nutritional status, changes in these parameters can affect the course of the disease. This situation can directly affect the response to treatment and survival [

21].

Our study has thoroughly evaluated the prognostic impact of PNI and GNRI on survival in a geriatric patient group diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer. Malnutrition and chronic inflammation are well-known factors that can contribute to poor outcomes in cancer treatment [

22]. Nutritional status, as reflected by indices such as PNI and GNRI, provides valuable information about a patient's ability to withstand the stresses of cancer treatment and their overall recovery potential [

23] Inflammation, often measured through acute phase proteins and cytokines, is linked to cancer progression and metastasis, influencing both tumor biology and the body’s response to therapy [

24]. Our findings indicate that nutritional status and inflammation levels play a significant role in the overall survival (OS) of cancer patients. In particular, our study suggests that patients with poor nutritional status (low PNI and GNRI values) may have a compromised immune system, impaired response to treatment, and a greater risk of complications. This is consistent with the literature that highlights the detrimental effects of malnutrition on cancer patients' survival. A study by Takele et al. have shown that human nutritional status is associated with the inflammatory response and that malnutrition increases serum cytokine levels, altering neutrophil subgroups and function [

25]. In another study, it was stated that low pretreatment PNI is significantly associated with worse OS and progression-free survival (PFS) in PCa patients. This study suggests that low pretreatment PNI may serve as a reliable and effective predictor for the prognosis of PCa patients [

26]. Similarly, in our study, low PNI and low GNRI values were significantly correlated with shorter overall survival (p = 0.015). The relationship between inflammation and survival also emphasizes the need for managing both these factors during cancer care. These results indicate that PNI and GNRI reflect the patients’ overall nutritional status and immune system capacity, and that these parameters can directly affect cancer prognosis [

27]. Deterioration of nutritional status can increase the risk of infection and accelerate the progression of cancer, along with weakening the immune system [

28]. These results, which show how malnutrition and inflammation affect survival, especially in geriatric patients, indicate that PNI and GNRI should be regularly evaluated in clinical practice.Targeted interventions aimed at improving nutritional status and controlling inflammation could enhance overall treatment outcomes, and this may warrant further investigation in future research to develop supportive treatment strategies for patients at high nutritional risk. In our study, PNI and GNRI were identified as independent prognostic factors in multivariate analysis, indicating that they provide additional information beyond traditional factors such as Gleason score and tumor stage in predicting survival. Additionally, the independent prognostic value of PNI and GNRI has been previously reported in other cancer types, such as colorectal cancer, where poor nutritional status and increased inflammation were shown to negatively impact survival rates [

29].

High PSA levels are well-established as an independent poor prognostic factor in prostate cancer, as elevated PSA is often associated with larger tumor burden and aggressive disease behavior [

30]. Patients with PSA ≥10 ng/mL generally have a worse prognosis and may require aggressive treatment [

31]. Patients with T1 and low PSA levels have the best survival rates and this group can be classified as low risk [

32]. Our study has shown that high PSA levels are an independent poor prognostic factor and are associated with worse survival when combined with stage T2 tumor, low PNI, and low GNRI. These findings align with previous studies showing that high PSA levels are a key indicator of aggressive disease, necessitating closer monitoring and more intensive treatment [

33].

When evaluated in terms of tumor burden, patients with T1 tumor burden have the longest survival duration, while patients with T2 tumor burden have shorter survival durations. In patients with T1 tumors and low PSA levels, the median survival was determined to be 130 months, while in patients with T2 tumors or high PSA levels, it was 76 months (p< 0.001). These results indicate that survival decreases and disease prognosis worsens with the increase in tumor burden. Patients with T2 tumor and high PSA levels had the shortest survival, emphasizing the need for intensive monitoring and treatment in this group. Additionally, evaluating PNI and GNRI alongside PSA provides a more comprehensive risk assessment for patient management. In previous studies, high PSA levels have been reported as a poor prognostic factor, but their evaluation in conjunction with nutritional indices (PNI/GNRI) and tumor burden (T1/T2) has been limited. For example, Kaya et al. found that serum albumin levels (a variable associated with GNRI) could be supportive in the diagnosis of the disease [

34]. Some studies have reported that adherence to unhealthy eating patterns, such as a western diet, has been attributed to an increased risk of prostate cancer [

35]. Our study is significant as one of the first retrospective analyses to examine this combination in detail. Serum PSA levels are influenced by many factors [

36,

37]. Our study has shown that local radiotherapy provides a survival advantage even for patients with high PSA levels (p = 0.015), therefore these findings indicate that PSA is not only a diagnostic marker but also a strong prognostic factor in predicting survival. Especially for patients with high PSA levels, the implementation of early and aggressive treatment strategies is recommended.

It has been shown that body mass index (BMI) alone does not have prognostic value in renal cell carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer, and gastric cancer [

9,

38,

39,

40]. Although the prognostic importance of PNI and GNRI has been previously reported in other types of cancer, data on this topic specific to prostate cancer is limited. A study by Wang et al. investigated the prognostic value of the serum albumin/globulin ratio (AGR). The study shows that AGR is an independent prognostic biomarker for PFS and cancer-specific survival. Specifically, patients with a low AGR (<1.45) were found to have worse outcomes [

41]. In another study, it was found that inflammatory markers, particularly C-Reactive Protein (CRP), haptoglobin, and albumin, were associated with prostate cancer severity and prognosis. However, only albumin showed a positive correlation with overall mortality and Gleason 4+3 tumors. Apart from albumin, other inflammatory markers were not associated with prostate cancer death or overall mortality [

42]. As a nutrition-related risk index, GNRI differs from BMI in that it increases the weight of albumin rather than body weight, thus successfully distinguishing between malnourished patients with high BMI and those with low BMI [

43]. Our study is one of the first retrospective analyses to directly show the relationship between these two indices and survival in early-stage prostate cancer patients, highlighting the clinical potential of these indices.In our study, we evaluated the prognostic value of PNI and GNRI based on factors such as age, Gleason score, tumor stage, and receipt of local radiotherapy. Older age is seen as a critical risk factor for prostate cancer [

44]. Considering the results of our study, survival duration significantly decreased with increasing age. A marked decline in survival was observed particularly in the 75–85 age group (p = 0.005). Regardless of whether the patients are in the geriatric age group, a negative relationship between GNRI and the likelihood of prostate cancer has been demonstrated [

45]. Additionally, studies have shown the importance of physical activity in the prevention of prostate cancer [

46]. These results indicate that focusing solely on the biological course of cancer in older patients may be insufficient. It is clear that when developing personalized treatment strategies, age, nutritional status, and overall health profile should be taken into account. These results support the importance of considering PNI and GNRI in treatment decisions.In patients with a high Gleason score and high tumor volume, survival was found to be significantly shorter (p < 0.001). This finding is consistent with previous literature, emphasizing that both tumor grade and volume are critical prognostic indicators in prostate cancer. The Gleason score is one of the most important histopathological parameters determining the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. A high Gleason score indicates that the cancer is progressing more rapidly and that the response to treatment may be more limited [

47]. These results highlight the importance of early detection and risk stratification in prostate cancer management. Incorporating both pathological parameters such as Gleason score and tumor volume into treatment planning can help guide therapeutic decisions and improve patient outcomes, particularly in the geriatric population where treatment tolerance and comorbidities must also be carefully considered.

In our study, the administration of local radiotherapy was correlated with improved survival outcomes relative to patients who did not receive radiotherapy (p = 0.008). In making the decision for radiotherapy, it is observed that factors such as patients' PSA levels, tumor burden, and nutritional status should be taken into consideration. This finding underscores the potential therapeutic benefit of local radiotherapy, even in elderly patients with early-stage prostate cancer. Radiotherapy may contribute not only to local tumor control but also to improved systemic outcomes by reducing tumor burden and possibly modulating the tumor microenvironment [

48]. Moreover, in carefully selected geriatric patients, radiotherapy can offer a curative-intent treatment option with acceptable toxicity profiles, especially when other treatment modalities such as surgery may not be feasible due to comorbidities or functional limitations [

49]. These results support incorporating local radiotherapy into personalized treatment strategies and stress the need for further prospective studies to identify patient subgroups most likely to benefit. They also emphasize that, in assessing cancer prognosis, the patient's overall health should be considered alongside tumor biology.

This study had its advantages; firstly, the results were more convincing when a comprehensive database was used. Secondly, it was important to define malnutrition in the geriatric age group using PNI and GNRI, which are more reliable indicators than a single measure in adults. With a large patient population (n=205), it is one of the first retrospective analyses to demonstrate the prognostic importance of PNI and GNRI in early-stage prostate cancer. Additionally, we controlled for variables as much as possible and evaluated the relationship between GNRI and prostate cancer risk in different populations through stratified analysis. Subgroup analyses have shown how these indices vary in different patient groups. Multivariate analyses have supported that PNI and GNRI are independent prognostic markers from other factors.Our study also has limitations; the retrospective design may lead to potential selection bias. Additionally, despite controlling for several common variables, other unmeasured confounders may have contributed to potential bias. Potential confounders (e.g., comorbidities, systemic inflammation markers like CRP) were not included in the analysis. The PNI and GNRI values of the patients may change over time, but in this study, only the values at the time of diagnosis were evaluated. Longer follow-up periods are needed to examine the impact of changes in nutritional status and inflammatory markers over time on survival. Future prospective studies will be needed to validate the findings of this study.This study shows that PNI and GNRI are independent prognostic markers for survival in elderly patients with early-stage prostate cancer. Low PNI and GNRI values were associated with significantly shorter survival times, highlighting their strong impact on prognosis, particularly when combined with factors like advanced age, high Gleason score, high tumor volume, and disease burden. In contrast, patients in the high GNRI group had significantly higher BMI, serum albumin levels, and better Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), along with a lower average age and initial PSA levels. These characteristics were linked to a slower progression of prostate cancer and longer survival.

In conclusion this study highlights the prognostic value of the PNI and GNRI in elderly patients with early-stage prostate cancer. Both indices were independently associated with overall survival and may serve as valuable tools for risk stratification when used alongside traditional clinical parameters such as PSA and Gleason score. Patients with low PNI and GNRI values should be closely monitored, and supportive nutritional interventions should be considered. Additionally, the survival benefit observed in patients receiving local radiotherapy suggests this factor should be incorporated into individualized treatment planning.

Given the strong interplay between nutritional status, inflammation, and cancer outcomes, integrating inflammatory markers (e.g., CRP, Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR)) with PNI and GNRI could enhance prognostic accuracy. Although GNRI offers a comprehensive assessment of nutritional risk in older adults, its diagnostic utility in prostate cancer requires further validation. Future prospective, multicenter studies should investigate the dynamic changes in PNI and GNRI over time and assess their relevance across different treatment modalities. Interventions targeting nutritional improvement and inflammation modulation may further contribute to better patient outcomes. These findings emphasize the importance of a holistic, patient-centered approach in prostate cancer management.

Author Contributions

PP: AG, AD, Data curation: PP, AG,OÖ; Formal analysis: PP, AG,AD,TC; Investigation, Methodology: PP, AG,OÖ,AD,TC; Project administration: PP, AG,OÖ,BBD; Software: PP, AG,AD; Supervision: PP, AG,BAB Validation: PP, AG,AD,BBD; Writing - original draft: PP, AG,OÖ,AD,BAB Editing the text, making revisions, language corrections: PP, AG,OÖ,BBD,TC; Writing - review & editing: PP, AG,AD,OÖ,BBD. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.