1. Introduction

For more than a hundred years, sea urchins have served as an excellent experimental model for studying fertilization in vitro since their gametes can be obtained in large quantities and easily manipulated and observed in the Petri dish containing seawater, i.e., in experimental conditions closely resembling what happens at sea. However, despite the enormous knowledge and insights gained from this fundamental process, our understanding of the fertilization of this marine organism is not yet complete and remains a work in progress. The reports in the literature describe a generalized scheme of fertilization-associated reactions, including sperm activation and the acquisition of motility triggered by seawater, which increases intracellular pH and the respiration rate, as well as by egg-derived sperm-activating peptides that induce Ca

2+-dependent sperm chemotaxis [

1]. It has also been shown that the components of the egg jelly (jelly coat, JC) surrounding sea urchin eggs trigger the acrosome reaction (AR) in vitro, during which the acrosomal vesicle in the anterior portion of the sperm head undergoes exocytosis, allowing the species-specificity binding of the fertilizing sperm with the egg membrane [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Since the JC preparations of some sea urchin species induced the AR in homologous sperm, it was suggested that the specific induction of the AR was due to the structural uniqueness of the JC in the pattern of sulfation and the glycosidic linkage of the polysaccharides [

1,

9]. The AR leads to the extension of the acrosomal process (AP) following actin polymerization, which exposes bindin at the tip of the sperm head. This adhesive protein interacts with the sperm receptors on the thin vitelline layer (VL) of the egg, which tightly adheres to the microvilli (MV) containing actin emerging from the egg membrane by “vitelline posts” [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Further proteolytic treatments of the unfertilized eggs with enzymes showed that the broken-up of the VL on the egg surface reduced the fertilizability of eggs by disrupting the sperm-binding site on the VL [

14]. Additional studies showed that during the cortical reaction of the fertilized egg, some proteases are released from the cortical granules (CG) undergoing exocytosis and deposited into the perivitelline space (PS), thereby breaking the linkages between the VL and the plasma membrane of the MV. The action of proteases at the time of the separation of the VL from the egg plasma membrane also alters the sperm receptor sites. It facilitates the detachment of supernumerary sperm (slow block to polyspermy) [

15,

16,

17]. In line with this, trypsin inhibitors, which block the elevation of the fertilization envelope (FE) and sperm detachment, lead to polyspermy, which is detrimental to normal development [

16,

18,

19]. Incorporating structural proteins deriving from the extruded CG contents induces the structuralization of the PS and the subsequent hardening of the elevating VL to form the FE, which protects the embryo [

20,

21,

22]. Following fertilization, it was also possible to analyze the nature of the proteins from CG after their exocytosis in seawater from eggs where the VL had been previously disrupted by dithiothreitol (DTT) [

23]. The subsequent events of the fertilization process involving the penetration of the VL by the AP of the activated sperm and fusion between the egg membranes of sperm and egg have been poorly understood due to the rapidity of the process and to the fact that only one of the multiple sperm attached to the VL will fuse with the egg plasma membrane and penetrate it [

19,

24,

25,

26].

According to the prevailing view, the exposed bindin on the sperm AP is essential for the sperm to recognize and bind to its receptors of the egg VL [

27]. However, the fertilization response of

P. lividus eggs has been shown to occur even when the JC and VL have been structurally altered or removed from unfertilized eggs [

26,

28,

29,

30,

31], indicating that these layers are not essential for the activation of sperm. In sea urchin eggs, the fertilization process is characterized by an initial phase involving the depolarization of the egg plasma membrane, which coincides with F-actin-linked Ca²⁺ signals a few seconds after the fusion of the sperm and egg membranes [

32,

33,

34]. These events strictly depend on the morphology of MV containing actin filaments and the structural integrity of cortical granules/vesicles associated with the egg plasma membrane, which is crucial for the proper changes that occur during egg activation [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The sperm-induced Ca

2+ increase before and during the exocytosis of the CG coincides with the visible depolymerization of the F-actin in the outer region of the cytoplasm (ectoplasm) of the egg. During the egg’s contraction, it forms a dimple, which reflects the initial separation of the VL from the egg plasma membrane [

39,

40,

41,

42]. This early Ca

2+-dependent cortical reaction is a prerequisite for the subsequent metabolic activation and embryonic development phase. During this late fertilization phase, starting 5 minutes after insemination, the development of K

+ conductance, MV elongation, and cortical actin polymerization induced by an intracellular pH increase [

19,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48] counteract the c F-actin-linked depolymerization of the egg surface taking place a few seconds after sperm addition [

31,

42]. The cortical actin remodeling at the site of sperm-egg binding involves the formation of a cone of actin filaments (fertilization cone, FC) to engulf the sperm first visualized at the transmission electron microscope in sea urchin eggs preincubated and inseminated in the presence of nicotine to induce polyspermy and thereby to increase the chances of cutting ultrathin sections through the multiple FC [

49,

50]. It is important to note that recent studies have shown that nicotine treatment of

P. lividus eggs induces polyspermic entry by dramatically altering the dynamics of the egg’s F-actin, leading to abnormal sperm penetration in the activated eggs [

51].

Previous studies on the interactions of the fertilizing sperm with the surface of sea urchin eggs also aimed at understanding the role of the glycoprotein components of the sperm receptors in the VL. The results showed that the lectin Concanavalin A (Con A), which can precipitate with numerous polysaccharides [

52], can prevent fertilization at a concentration higher than 0.1 mg/ml in several sea urchin species [

53,

54,

55]. Insight into the nature of the effect of Con A on sea urchin fertilization and incubation of intact

Strongilocentrotus purpuratus eggs with fluorescent Con A revealed its high affinity binding to the VL sites but not the JC. The removal or alteration of the VL by dithiothreitol [

23] reduces the number of Con A binding sites on the plasma membrane (low affinity) of unfertilized eggs [

55]. Following fertilization of eggs deprived of the VL, the increased number of Con A binding sites on the egg plasma membrane was suggested to be due to the insertion of the membranes of the CG following their exocytosis [

54,

56]. These results indicated that the interaction of Con A with the “naked” plasma membrane of

S. purpuratus eggs did not prevent the attachment and fusion of the sperm with the egg and the induction of the cortical reaction [

54,

55]. Subsequently, the great variety of conflicting observations about the effect of Con A on the fertilization process of different sea urchin eggs was argued to be due to the crosslinking of the specific carbohydrate residues of the sperm receptors with which the Con A binds, let alone how the fertilization was conducted [

57].

In the present investigation, to resolve the contradictory results in the literature on the role of the VL glycoprotein in the species-specificity gamete interaction, we exposed P. lividus eggs to different concentrations of Con A and studied their effect on the morpho-functional aspects of the fertilization process. Upon insemination, the initiation of the sperm-induced Ca2+ signal representing the sperm-egg fusion has been employed as criteria with which to judge whether the binding of Con A with the VL carbohydrate residues could affect sperm-egg interaction and egg activation. Our electron microscopy examinations have revealed that 5 minutes of exposure of intact and denuded P. lividus to Con A significantly alters the topography of the egg surface, e.g., the ultrastructure of the VL, microvilli, and cortical granules. These egg surface morphological changes induced by lectin incubation do not prevent the interaction and fusion of the sperm with the egg plasma membrane, nor do they delay the onset of the first sperm-induced Ca2+ signal at the periphery of the egg (cortical flash, CF), but heavily affect the pattern of the Ca2+ response at fertilization. Our use of standard fluorescence and confocal microscopy, along with a fluorescent version of Con A, to investigate the interaction of Con A with the VL of intact eggs and the plasma membrane of denuded eggs has enabled the first visualization of lectin binding to the outer JC.

4. Discussion

Fertilization of sea urchin eggs has been extensively studied across numerous species for over a century, resulting in a vast body of literature. Key findings indicate that fertilization is regulated by three significant interactions between the sperm and the egg. First, when the sperm contacts the outer jelly coat (JC) of the egg, the sperm acrosome reaction (AR) is triggered. This reaction is essential for forming the F-actin-linked acrosomal process (AP) extending from the head of the sperm, which exposes the adhesive protein bindin. Second, the adhesive protein bindin on the AP attaches explicitly to the glycoprotein of the vitelline layer (VL) that tightly covers the microvilli (MV) of the egg membrane. Finally, the fusion of the sperm with the egg membrane transduces the fertilization response, which is regulated by electrical changes of the egg membrane and Ca

2+ signals concomitant with the exocytosis of the cortical granules (CG). The contents of the CG released between the VL and egg plasma membrane separate them by expanding the perivitelline space. The VL develops into the thick FE, which hardens by crosslinking [

56,

69,

70]. It has been shown that upon insemination of sea urchin eggs, both the JC and VL play vital roles in sperm and egg activation. Furthermore, it has been postulated that the early changes of the egg membrane potential (depolarization) at the moment of the gamete fusion serve as an electrically mediated fast mechanism to block the attachment of multiple sperm, thereby preventing polyspermy at fertilization [

71].

Our recent findings, however, have challenged the prevailing view on how sperm fertilizes sea urchin eggs by demonstrating the following key points. First, sperm can activate

P. lividus eggs without undergoing the JC-induced AR. Second, species-specific recognition between gametes may occur at the level of the egg plasma membrane rather than at the VL. These results are evident because denuded eggs, which lack both the VL and JC, undergo polyspermic fertilization through the binding and fusion of multiple sperm [[

26,

30] and

Figure 6]. Finally, the fast block to polyspermy may be mediated structurally rather than electrically. This structural response involves adequately organizing F-actin-linked structures on the surface of unfertilized eggs, playing a crucial role in ensuring that only one sperm successfully activates the egg [

25,

42,

72].

In addition to being the location of the sperm receptor’s extracellular domain, which recognizes the bindin exposed on the AP of the sperm, the VL supposedly plays a crucial role in preventing the binding of multiple sperm through a slow mechanical block to polyspermy. At fertilization, during the release of CG content in the perivitelline space, a protease modifies the structure of the VL, causing the bound sperm to detach. The subsequent complete swelling of the VL over the entire zygote surface, leading to the formation of the FE, mechanically prevents any further interactions with additional sperm [

15,

16,

73,

74].

Contrary to the prevailing view, this study confirms our earlier findings that the VL of unfertilized eggs may hide regions on the egg plasma membrane where multiple sperm could attach, provided that the structural integrity of the VL is compromised [

29,

31]. Our findings regarding the significance of the morpho-functionality of the surface of unfertilized eggs, derived from their optimal physiological conditions, align with earlier observations from sea urchin fertilization studies [

75]. These studies claimed that sea urchin eggs “…….

if in best conditions are never polyspermic ………

Normally monospermic eggs can be rendered polyspermic by experimental treatment…..” [

76], which was corroborated in later studies [

29,

34,

39]. A recent proposal suggests that the intact structure of the VL in unfertilized eggs is crucial for the fertilization process. This glycoprotein structure surrounding microvilli facilitates the fusion of only the fertilizing sperm with the egg membrane at a specific site not masked by the VL [

26].

In addition to using lectins as markers for the surface architecture of normal and malignant cells in culture, Con A has been shown to specifically bind to the carbohydrate residues of the glycocalyx and cell membranes. Research has demonstrated that Con A inhibits various modification events at the surface of fertilized sea urchin eggs, including forming the fertilization envelope when eggs are inseminated after exposure to the lectin. This inhibition has been interpreted as a blockage of fertilization and subsequent cleavage [

14,

53,

54,

57].

In this study, we examined the effects of Con A on the fertilization of P. lividus eggs, aiming to resolve conflicting data in the literature regarding the role of glycoprotein components of the VL in the context of sperm egg recognition and binding. Using fluorescent Con A, our study also explored lectin binding to identify the glycoconjugates on the surface of intact and denuded eggs from which the VL had been stripped off. The results have confirmed Con A binding sites on the VL of intact eggs and, for the first time, on the JC surrounding them. In intact eggs, although the binding of Con A to the VL inhibits its separation across the entire surface of the egg, the sperm still triggered the fertilization Ca2+ signal transduction. This finding contrasts with previous studies reporting that Con A treatment of unfertilized (intact) eggs inhibits the elevation of the FE and, consequently, fertilization. In this study, we analyzed the extent of inhibition by measuring early fertilization events, including the pattern of sperm-induced Ca2+ signals upon fusion between the two gametes and the number of sperm incorporated into the egg. The results indicate that, despite changes in the morphology of the egg surface and cortical region, a modified fertilization response can still be triggered in the eggs that were inseminated after Con A preincubation. This study demonstrates that Con A binding to the extracellular matrix leads to altered cortical responses of the egg at fertilization, manifesting as significantly impaired sperm-induced Ca2+ signals and sperm incorporation. Alteration of the extracellular matrix by Con A binding affects the structure and dynamics of the F-actin comprising the egg’s surface and cortical region, as judged by TEM and confocal microscopy utilizing LifeAct-GFP.

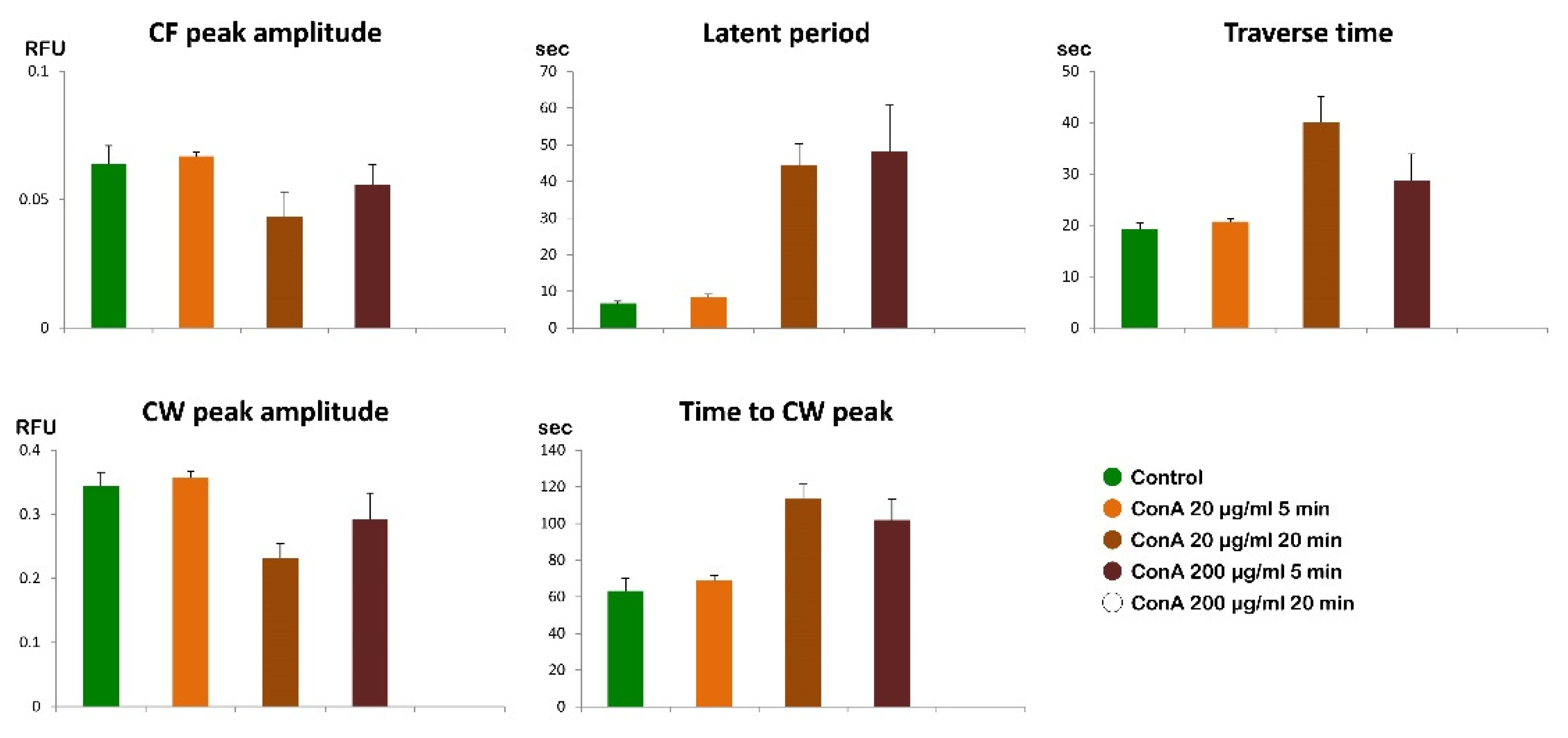

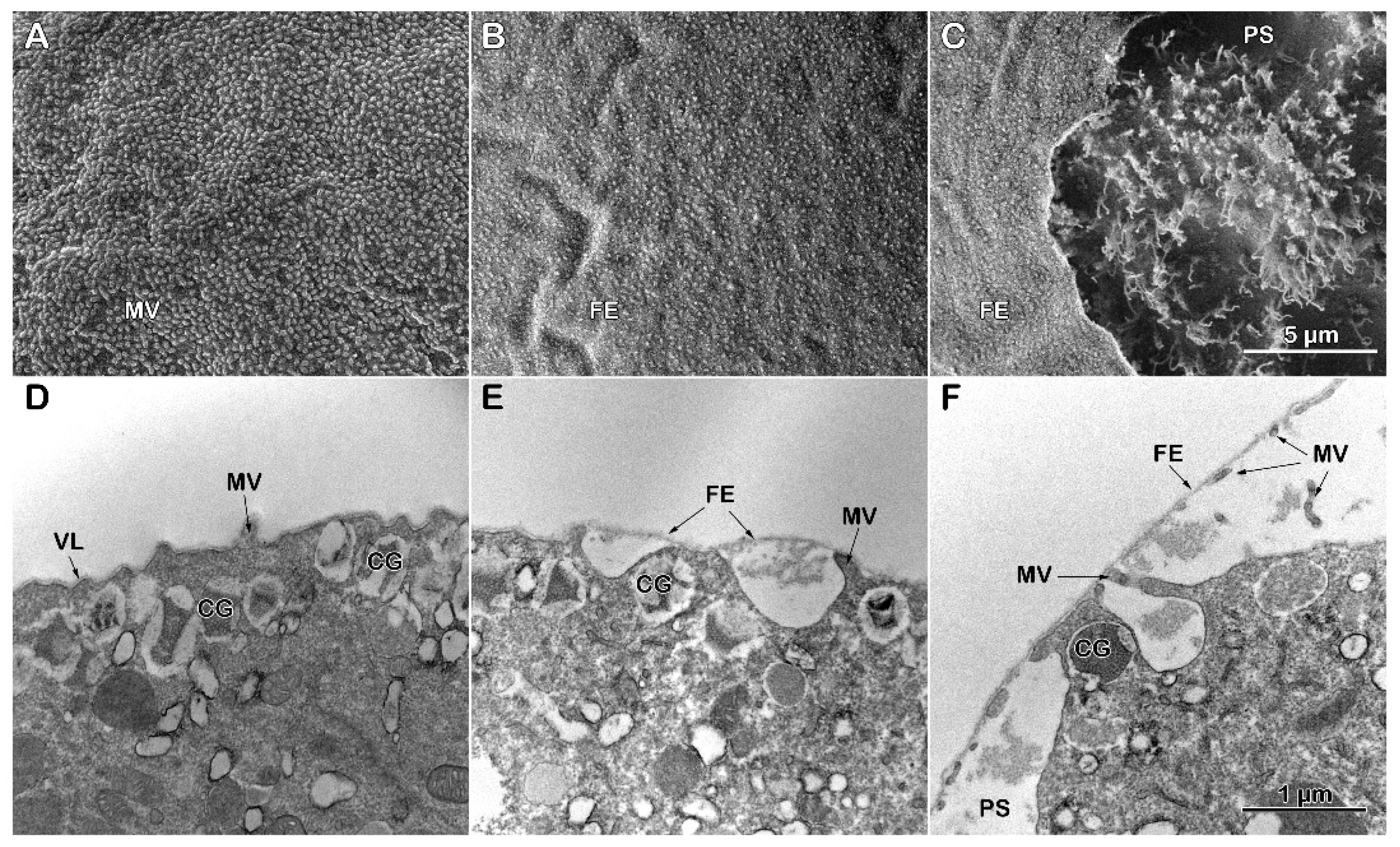

Exposure to Con A causes morphological changes in the VL and the F-actin-containing MV in intact eggs, to which the VL tightly adheres. These structural changes, which prevent the separation of the VL from the egg plasma membrane, are evident in the retention of cast remnants from the tips of the MVs that are still observed five minutes after insemination, as shown in the electron microscopy images (

Figure 5 and

Supplementary Video S2). The Con A treatment affecting proper detachment of the VL from the egg membrane in response to sperm stimulation may be related to the extended latent period experienced by eggs exposed to the lectin before insemination (see the graphs in

Figure 12 and

Supplementary Figure S2 for the measurement parameters of the Ca

2+ signals at fertilization).

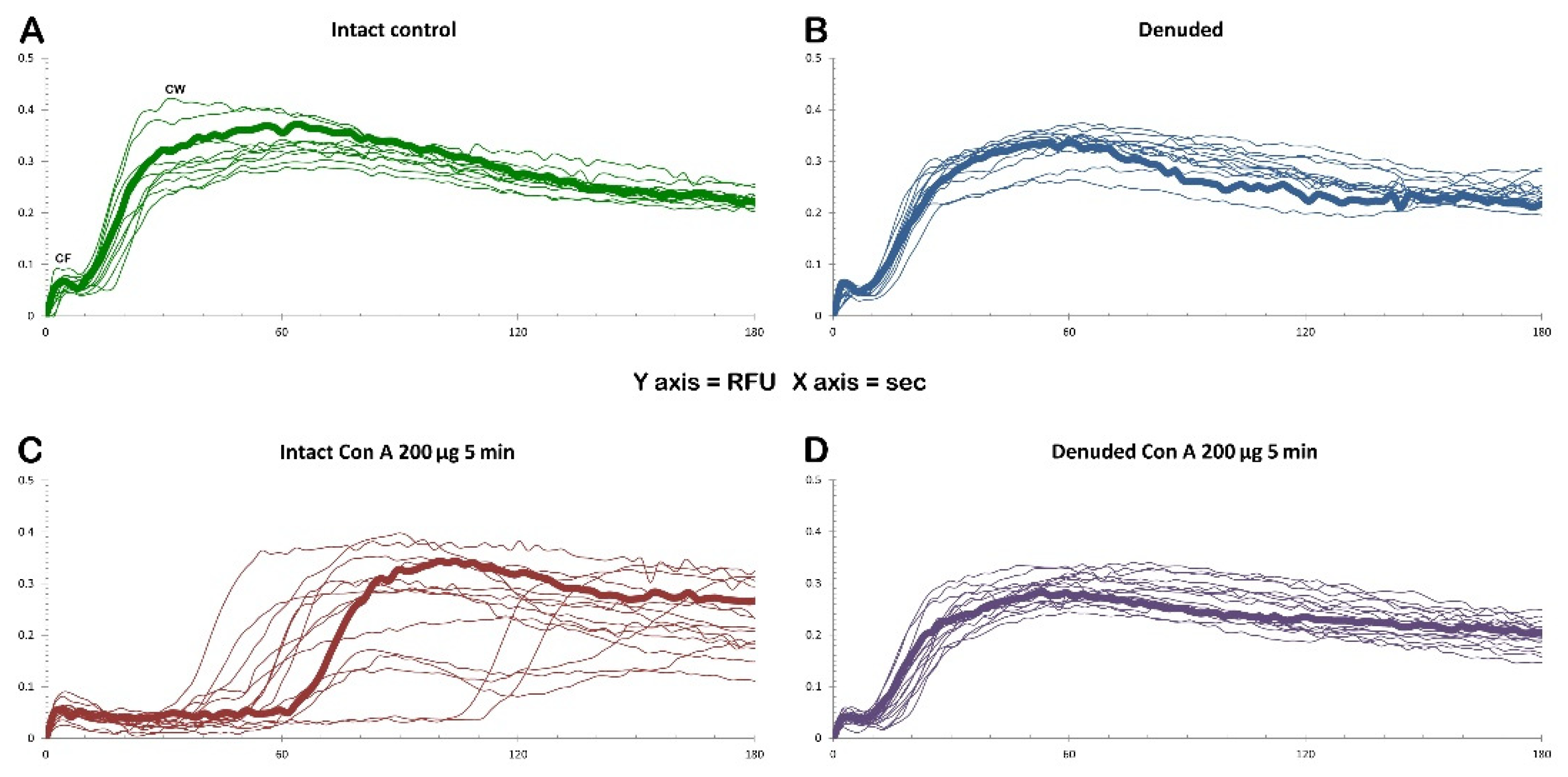

In line with the crucial role of the VL detachment from the egg membrane in regulating the initiation of the CW, we found that Con A pretreatment prolongs the latent period of the Ca

2+ response in the intact eggs but not in the denuded eggs (

Figure 14). Interestingly, a delayed CW onset after the CF is consistently observed in

P. lividus eggs inseminated after incubation with actin drugs such as cytochalasin B and latrunculin A [

34]. These findings are consistent with electrophysiological measurements reported in previous studies. Specifically, during fertilization in the eggs of the sea urchin species used in our experiments, two electrical events occur across the egg plasma membrane in response to the interaction with the fertilizing sperm. The first event is a step-like depolarization a few seconds after insemination, followed by a fertilization potential (FP) with a latent period between these two electrical changes of approximately 11 seconds [

32,

33]. Hence, at fertilization, the actin cytoskeletal changes at the sea urchin egg surface underlie the alteration of the Ca

2+ response (prolonged latent period) in these eggs, and the Ca

2+ response is precisely mirrored by the electrophysiological one [

34,

37,

77]. While it has been postulated that the Ca

2+ influx during the latent period is crucial for the initiation of the CW [

78], it has been suggested that the polymerization status of the F-actin bundles within the MV of the egg is an essential determinant of Ca

2+ influx [

79] with Ca

2+ channels being located in the MV. Disruption of the actin filaments with actin drugs also leads to the ‘spontaneous’ generation of Ca

2+ influx and waves in starfish eggs [

60]. Furthermore, the Con A pretreatment also modified the structure of the CG and how they are associated with the egg membrane (

Figure 5). Because CG are connected to the PM via subplasmalemmal actin filaments and their disassembly contributes to shaping the Ca

2+ wave patterns [

36,

38], the earlier observation that both the actin cytoskeleton at the egg surface and the CG influence the pattern of Ca

2+ signaling in fertilized eggs suggest that the ultrastructural changed in the subplasmalemmal region introduced by Con A may play a crucial role in altering the fertilization Ca

2+ events in these eggs [

34,

38].

Furthermore, the results of this study support our previous findings that the sperm of

P. lividus can fertilize eggs without undergoing acrosome reaction (AR) by the JC, and that the sperm can achieve its goal of fertilizing denuded egg lacking the VL where the sperm receptor should be located [[

26,

29,

30] and

Figure 6]. Additionally, the data of fluorescent Con A binding (

Figure 3 and

Figure 11) demonstrate that the egg membrane contains lower-affinity sites for the lectin when the JC and VL have been removed before insemination, similar to the earlier observations in other sea urchin species [

54]. However, in contrast to the published data, our results show that the fluorescence from the lectin bound to the membrane of denuded eggs after insemination does not reveal an increase in the number of binding sites following the exocytosis of CG, indicating that new membranes are not inserted into the egg membrane after CG exocytosis as previously suggested [

54]. Indeed, under our experimental conditions, we found that treating denuded eggs with Con A flattens the MV on the egg surface and impairs the process of CG exocytosis (

Figure 7). Interestingly, in addition to reducing the number of sperm entry entries, denuded eggs exposed to Con A experienced a statistically significant lower CF and CW amplitude as a result of the CG exocytosis impairment, reinforcing the critical function of the microvillar and CG morphology in transducing the fertilization Ca

2+ response in these sea urchin eggs. It follows that although several signaling pathways have been proposed to explain the complex systems of intracellular Ca

2+ mobilization activated during the fertilization of sea urchin eggs [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87], further studies are needed to uncover the molecular events involved in sperm-induced Ca

2+ signaling.

Our results indicate that fertilization can still occur when sperm interacts with denuded eggs that have undergone significant changes in their MV morphology. These changes include a reduction in both the number and length of the MV (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 6 for a comparison with the control), which is attributed to the stripping of the vitelline layer (VL) [

26,

30]. It would be beneficial to understand whether, even under these conditions, the fertilizing sperm primarily fuses with the egg membrane at the tip of the microvilli, as suggested by previous ultrastructural analyses [

19,

72], or if this interaction occurs at other regions of the egg membrane [

30]. Finally, our results support the notion that lectins inhibit cell migration by regulating F-actin content and distribution [

88]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that connect signaling molecules to the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton could provide a new perspective on the potential of Con A as a cancer cell killer [

89].

Figure 1.

Effect of Concanavalin A (Con A) on fertilization. Intact P. lividus was pretreated with Con A for 5 min before insemination. The bright field image in the upper panel illustrates the progressive elevation of the fertilization envelope (FE) being blocked in the eggs fertilized after Con A treatment. A noticeable dimple (arrow) on the egg surface fails to lead to elevated FE but remains visible even 5 minutes after insemination. The representative epifluorescence images show the fertilizing sperm stained with Hoechst-33342 in the control eggs 5 minutes post-insemination (arrow). The exposure to Con A (> 200 μg/ml) inhibited sperm entry, regardless of whether the eggs were washed; only the female pronucleus is visible in the epifluorescence image (arrowhead).

Figure 1.

Effect of Concanavalin A (Con A) on fertilization. Intact P. lividus was pretreated with Con A for 5 min before insemination. The bright field image in the upper panel illustrates the progressive elevation of the fertilization envelope (FE) being blocked in the eggs fertilized after Con A treatment. A noticeable dimple (arrow) on the egg surface fails to lead to elevated FE but remains visible even 5 minutes after insemination. The representative epifluorescence images show the fertilizing sperm stained with Hoechst-33342 in the control eggs 5 minutes post-insemination (arrow). The exposure to Con A (> 200 μg/ml) inhibited sperm entry, regardless of whether the eggs were washed; only the female pronucleus is visible in the epifluorescence image (arrowhead).

Figure 2.

Effect of Con A on fertilization of denuded P. lividus eggs. The bright field image in the upper panel shows that the vitelline layer did not separate to form the FE due to its prior removal from the unfertilized eggs. As a result, a noticeable dimple did not form on the egg surface, indicating the impact of Con A on fertilization-induced egg contraction. The representative epifluorescence images display multiple sperm stained with Hoechst-33342 in the denuded eggs 5 minutes post-insemination (arrow) and the female pronucleus (arrowhead). This tendency of polyspermy is alleviated by the pretreatment of the denuded eggs with Con A, as shown in the histograms.

Figure 2.

Effect of Con A on fertilization of denuded P. lividus eggs. The bright field image in the upper panel shows that the vitelline layer did not separate to form the FE due to its prior removal from the unfertilized eggs. As a result, a noticeable dimple did not form on the egg surface, indicating the impact of Con A on fertilization-induced egg contraction. The representative epifluorescence images display multiple sperm stained with Hoechst-33342 in the denuded eggs 5 minutes post-insemination (arrow) and the female pronucleus (arrowhead). This tendency of polyspermy is alleviated by the pretreatment of the denuded eggs with Con A, as shown in the histograms.

Figure 3.

Fluorescent Concanavalin A binding on the extracellular matrix (jelly coat, JC and vitelline layer, VL) of intact unfertilized eggs and the membrane of denuded eggs. The peripheral JC of intact eggs was disclosed with Alexa Fluor 633 Con A by using a pinhole setting at 4 AU. On the other hand, the lectin tightly binding to the VL was visualized using a pinhole setting of 1 AU (arrow). A low-affinity lectin binding to the egg membrane was observed using the 1 AU pinhole setting when comparing intact eggs to denuded eggs lacking VL (see also

Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 3.

Fluorescent Concanavalin A binding on the extracellular matrix (jelly coat, JC and vitelline layer, VL) of intact unfertilized eggs and the membrane of denuded eggs. The peripheral JC of intact eggs was disclosed with Alexa Fluor 633 Con A by using a pinhole setting at 4 AU. On the other hand, the lectin tightly binding to the VL was visualized using a pinhole setting of 1 AU (arrow). A low-affinity lectin binding to the egg membrane was observed using the 1 AU pinhole setting when comparing intact eggs to denuded eggs lacking VL (see also

Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the intact P. lividus eggs before and after fertilization. (A) A scanning electron micrograph shows microvilli (MV) regularly distributed on the surface of an unfertilized egg. (B) Five minutes post-insemination, FE forms and elevates over the surface of the activated egg. (C) A transmission electron micrograph reveals the surface of an unfertilized egg with MV covered by the vitelline layer (VL), along with secretory cortical granules (CG) located beneath the egg’s plasma membrane. (D) Five minutes after insemination, elongated MV amid the hyaline layer (HL) fill the perivitelline space (PS) beneath the FE.

Figure 4.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the intact P. lividus eggs before and after fertilization. (A) A scanning electron micrograph shows microvilli (MV) regularly distributed on the surface of an unfertilized egg. (B) Five minutes post-insemination, FE forms and elevates over the surface of the activated egg. (C) A transmission electron micrograph reveals the surface of an unfertilized egg with MV covered by the vitelline layer (VL), along with secretory cortical granules (CG) located beneath the egg’s plasma membrane. (D) Five minutes after insemination, elongated MV amid the hyaline layer (HL) fill the perivitelline space (PS) beneath the FE.

Figure 5.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the fertilization response of intact

P. lividus eggs pretreated with Con A before insemination. (

A) A scanning electron micrograph displays microvilli (MV) distributed on the surface of an unfertilized egg exposed to Con A for 5 minutes before fertilization. (

B) Five minutes after insemination, the FE does not elevate on the surface. (

C) In the perivitelline space (PS) of the fertilized eggs, MV elongation is observed where the FE attached to the MV’s tips was ruptured. (

D) A transmission electron micrograph shows the surface of an unfertilized egg exposed to Con A, highlighting altered MV morphology and secretory cortical granules (CG) located deeper within the egg’s cytoplasm. (

E) Five minutes after insemination, the induction and propagation of CG exocytosis are inhibited in Con A-pretreated eggs, as evidenced by isolated events of the CG exocytosis, which lead to the separation of the vitelline layer precursor of the FE. (

F) Bound to Con A, the VL of the intact eggs fails to detach itself from the MV of the egg membrane at the time of fertilization. Note that, compared to the control shown in

Figure 4 D, the FE is thinner due to the incomplete exocytosis of the CG.

Figure 5.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the fertilization response of intact

P. lividus eggs pretreated with Con A before insemination. (

A) A scanning electron micrograph displays microvilli (MV) distributed on the surface of an unfertilized egg exposed to Con A for 5 minutes before fertilization. (

B) Five minutes after insemination, the FE does not elevate on the surface. (

C) In the perivitelline space (PS) of the fertilized eggs, MV elongation is observed where the FE attached to the MV’s tips was ruptured. (

D) A transmission electron micrograph shows the surface of an unfertilized egg exposed to Con A, highlighting altered MV morphology and secretory cortical granules (CG) located deeper within the egg’s cytoplasm. (

E) Five minutes after insemination, the induction and propagation of CG exocytosis are inhibited in Con A-pretreated eggs, as evidenced by isolated events of the CG exocytosis, which lead to the separation of the vitelline layer precursor of the FE. (

F) Bound to Con A, the VL of the intact eggs fails to detach itself from the MV of the egg membrane at the time of fertilization. Note that, compared to the control shown in

Figure 4 D, the FE is thinner due to the incomplete exocytosis of the CG.

Figure 6.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the denuded P. lividus eggs at fertilization. (A) The surface of an egg after the removal of VL. This treatment decreases the number of microvilli (MV) and alters their morphology. (B) Inseminating denuded eggs leads to polyspermic fertilization, as evidenced by the formation of three fertilization cones (FC, arrows) that incorporate sperm. (C) Magnified image of the fertilization cones in panel B. Note the elongated MV in areas of the egg’s surface where they were present before fertilization amid numerous interspersed holes. Note also that the FE elevation is absent because the VL had been removed before insemination. (D) The transmission electron micrograph shows the lack of the VL and the altered morphology of MV and cortical granules (CG). (E) Five minutes post-insemination, the micrograph shows the absence of the CG due to the exocytosis of their content and MV elongation on the surface. HL= Hyaline layer.

Figure 6.

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs of the denuded P. lividus eggs at fertilization. (A) The surface of an egg after the removal of VL. This treatment decreases the number of microvilli (MV) and alters their morphology. (B) Inseminating denuded eggs leads to polyspermic fertilization, as evidenced by the formation of three fertilization cones (FC, arrows) that incorporate sperm. (C) Magnified image of the fertilization cones in panel B. Note the elongated MV in areas of the egg’s surface where they were present before fertilization amid numerous interspersed holes. Note also that the FE elevation is absent because the VL had been removed before insemination. (D) The transmission electron micrograph shows the lack of the VL and the altered morphology of MV and cortical granules (CG). (E) Five minutes post-insemination, the micrograph shows the absence of the CG due to the exocytosis of their content and MV elongation on the surface. HL= Hyaline layer.

Figure 7.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization of the denuded eggs of P. lividus. (A) The scanning electron micrograph of the denuded eggs exposed to Con A reveals the reduced number of microvilli (MV) and altered surface morphology. (B) Insemination of Con-A-treated denuded eggs results in modified fertilization cones (FC). (C) A higher magnification of the micrograph presented in B shows a significant lack of MV elongation and flattened microvilli (MV) on the egg surface. (D) A transmission electron micrograph of a denuded egg treated with Con A before insemination displays the altered morphology of microvilli (MV), cortical granules (CG), and cytoplasmic ultrastructure. (E) After insemination, the presence of CG beneath the plasma membrane was still evident on the surface of the activated egg five minutes after insemination. Additionally, MV are consistently flattening. Note the absence of FE elevation due to removing the vitelline layer from the unfertilized egg.

Figure 7.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization of the denuded eggs of P. lividus. (A) The scanning electron micrograph of the denuded eggs exposed to Con A reveals the reduced number of microvilli (MV) and altered surface morphology. (B) Insemination of Con-A-treated denuded eggs results in modified fertilization cones (FC). (C) A higher magnification of the micrograph presented in B shows a significant lack of MV elongation and flattened microvilli (MV) on the egg surface. (D) A transmission electron micrograph of a denuded egg treated with Con A before insemination displays the altered morphology of microvilli (MV), cortical granules (CG), and cytoplasmic ultrastructure. (E) After insemination, the presence of CG beneath the plasma membrane was still evident on the surface of the activated egg five minutes after insemination. Additionally, MV are consistently flattening. Note the absence of FE elevation due to removing the vitelline layer from the unfertilized egg.

Figure 8.

Cortical reaction and F-actin changes in intact P. lividus eggs at fertilization. Intact eggs were incubated with or without Con A preincubation before insemination: (A) confocal microscopic images of the control eggs without Con A preincubation before and after insemination, (B) eggs with Con A preincubation (200 μg/ml, 5 min). To visualize the changes in the plasma membrane, F-actin, and the extracellular matrix, the same eggs were first microinjected or incubated with the corresponding fluorescent markers, as was described in the materials and Methods: FM 1-43 (orange color), LifeAct-GFP (green), and Alexa-Con A (red). Note that Con A preincubation inhibited the propagation and FE elevation. It is important to note that the reversible dimple formation (arrow) in control eggs is still visible on the surface of Con A-treated eggs 5 minutes after insemination. The fluorescent sperm were stained with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342.

Figure 8.

Cortical reaction and F-actin changes in intact P. lividus eggs at fertilization. Intact eggs were incubated with or without Con A preincubation before insemination: (A) confocal microscopic images of the control eggs without Con A preincubation before and after insemination, (B) eggs with Con A preincubation (200 μg/ml, 5 min). To visualize the changes in the plasma membrane, F-actin, and the extracellular matrix, the same eggs were first microinjected or incubated with the corresponding fluorescent markers, as was described in the materials and Methods: FM 1-43 (orange color), LifeAct-GFP (green), and Alexa-Con A (red). Note that Con A preincubation inhibited the propagation and FE elevation. It is important to note that the reversible dimple formation (arrow) in control eggs is still visible on the surface of Con A-treated eggs 5 minutes after insemination. The fluorescent sperm were stained with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342.

Figure 9.

Con A pretreatment alters the cortical reaction of denuded P. lividus eggs at fertilization. Denuded eggs were incubated with or without Con A prior to insemination. To visualize the plasma membrane, F-actin, and the extracellular matrix, the same eggs were first microinjected or incubated with the corresponding fluorescent markers, as described in the Materials and Methods: FM 1-43 (orange), LifeAct-GFP (green), and Alexa-Con A (red). (A) Confocal microscopic images of the denuded eggs without Con A pretreatment. (B) Denuded eggs fertilized after 5 min incubation with 200 μg/ml. Blue signals represent sperm stained with Hoechst 33342.

Figure 9.

Con A pretreatment alters the cortical reaction of denuded P. lividus eggs at fertilization. Denuded eggs were incubated with or without Con A prior to insemination. To visualize the plasma membrane, F-actin, and the extracellular matrix, the same eggs were first microinjected or incubated with the corresponding fluorescent markers, as described in the Materials and Methods: FM 1-43 (orange), LifeAct-GFP (green), and Alexa-Con A (red). (A) Confocal microscopic images of the denuded eggs without Con A pretreatment. (B) Denuded eggs fertilized after 5 min incubation with 200 μg/ml. Blue signals represent sperm stained with Hoechst 33342.

Figure 10.

Effect of Concanavalin A (Con A) at a concentration on the fertilization reaction of intact P. lividus eggs microinjected with AlexaFluor 568–phalloidin. In the upper panel, a control egg’s fertilization response shows the FE elevation following the exocytosis of cortical granules and a centripetal movement of actin filaments from the surface toward the center of the zygote. However, preincubation of the eggs with Con A (200 µg/ml, 5 min) inhibited the progressive reorganization of F-actin seen in the intact control eggs. Note the dimple (arrow) on these eggs that remained 5 to 20 min due to the decreased egg surface contractility caused by Con A.

Figure 10.

Effect of Concanavalin A (Con A) at a concentration on the fertilization reaction of intact P. lividus eggs microinjected with AlexaFluor 568–phalloidin. In the upper panel, a control egg’s fertilization response shows the FE elevation following the exocytosis of cortical granules and a centripetal movement of actin filaments from the surface toward the center of the zygote. However, preincubation of the eggs with Con A (200 µg/ml, 5 min) inhibited the progressive reorganization of F-actin seen in the intact control eggs. Note the dimple (arrow) on these eggs that remained 5 to 20 min due to the decreased egg surface contractility caused by Con A.

Figure 11.

(A) The staining of living P. lividus sperm diluted with the fluorescent polyamine BPA-C8-Cy3 in natural seawater (NSW). Note the presence of membrane protrusions on the sperm head, which resemble an acrosomal process (indicated by arrowheads). (B) Intact eggs were stained with Alexa Fluor 633-Con A to visualize JC and the VL. (C) Denuded eggs stained with Con A. The sperm diluted in NSW are able to fertilize both intact and denuded eggs, raising the question about the indispensability of egg jelly-induced AR for fertilization.

Figure 11.

(A) The staining of living P. lividus sperm diluted with the fluorescent polyamine BPA-C8-Cy3 in natural seawater (NSW). Note the presence of membrane protrusions on the sperm head, which resemble an acrosomal process (indicated by arrowheads). (B) Intact eggs were stained with Alexa Fluor 633-Con A to visualize JC and the VL. (C) Denuded eggs stained with Con A. The sperm diluted in NSW are able to fertilize both intact and denuded eggs, raising the question about the indispensability of egg jelly-induced AR for fertilization.

Figure 12.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization Ca

2+ response. Intact

P.

lividus eggs microinjected with calcium dyes were preincubated with various doses of Con A for 5 min before fertilization. The relative fluorescence (RFU) of the Ca

2+ signal was obtained from a time-lapse recording after sperm addition. The moment of the first Ca

2+ signal was set as t = 0.

A) The intact (not treated, control) eggs fertilized in NSW at pH 8.1 exhibited two modes of Ca

2+ responses: the cortical flash (CF) and the subsequent Ca

2+ wave (CW). The time interval between the two events is referred to as the ‘latent period.’ (B-E) When intact eggs are exposed to various concentrations of Con A, there is a significant prolongation of the latent period and an alteration of the patterns of the sperm-induced Ca

2+ response, as shown in the histograms in

Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization Ca

2+ response. Intact

P.

lividus eggs microinjected with calcium dyes were preincubated with various doses of Con A for 5 min before fertilization. The relative fluorescence (RFU) of the Ca

2+ signal was obtained from a time-lapse recording after sperm addition. The moment of the first Ca

2+ signal was set as t = 0.

A) The intact (not treated, control) eggs fertilized in NSW at pH 8.1 exhibited two modes of Ca

2+ responses: the cortical flash (CF) and the subsequent Ca

2+ wave (CW). The time interval between the two events is referred to as the ‘latent period.’ (B-E) When intact eggs are exposed to various concentrations of Con A, there is a significant prolongation of the latent period and an alteration of the patterns of the sperm-induced Ca

2+ response, as shown in the histograms in

Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Histograms summarizing the Ca2+ response in intact (control) and treated Paracentrotus lividus eggs at fertilization. Before insemination, the eggs were incubated with various doses of Con A.

Figure 13.

Histograms summarizing the Ca2+ response in intact (control) and treated Paracentrotus lividus eggs at fertilization. Before insemination, the eggs were incubated with various doses of Con A.

Figure 14.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization Ca

2+ response in intact and denuded

P. lividus eggs.

A) The graphs show the relative fluorescence (RFU, green curves) recorded in the intact (untreated) and denuded (blue lines,

B) eggs in natural seawater (NSW) without Con A preincubation. The moment of the first detectable Ca

2+ response (CF) was set as t=0. (

C) Intact eggs preincubated with 200 μg/ml for 5 min before insemination (purple curves). (

D) Denuded eggs were inseminated after 5 min preincubation with 200 μg/ml (violet curves). Note that the Con A pretreatment significantly prolongs the latent period in the intact eggs at fertilization but not in the denuded eggs. The bolded curves represent the graphs of the Ca

2+ responses of the eggs shown in the

Supplementary Videos.

Figure 14.

Effect of Con A on the fertilization Ca

2+ response in intact and denuded

P. lividus eggs.

A) The graphs show the relative fluorescence (RFU, green curves) recorded in the intact (untreated) and denuded (blue lines,

B) eggs in natural seawater (NSW) without Con A preincubation. The moment of the first detectable Ca

2+ response (CF) was set as t=0. (

C) Intact eggs preincubated with 200 μg/ml for 5 min before insemination (purple curves). (

D) Denuded eggs were inseminated after 5 min preincubation with 200 μg/ml (violet curves). Note that the Con A pretreatment significantly prolongs the latent period in the intact eggs at fertilization but not in the denuded eggs. The bolded curves represent the graphs of the Ca

2+ responses of the eggs shown in the

Supplementary Videos.

Table 1.

Number of egg-incorporated sperm with various concentrations of Con A in the medium.

Table 1.

Number of egg-incorporated sperm with various concentrations of Con A in the medium.

| Sperm entry |

0 |

1 mg/ml Con A |

200 µg/ml Con A |

20 µg/ml Con A |

1 µg/ml Con A |

| Mean ± SD |

1 ± 0 |

0 ± 0* |

0.33 ± 0.23* |

1 ± 0 |

1 ± 0 |

| n |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |