1. Introduction

Efficient and precise weed management is central to sustainable crop production systems, particularly in the context of growing environmental concerns and herbicide resistance [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Lentil crops (

Lens culinaris Medik.) are especially vulnerable during early development stages, where timely and spatially precise weed control can dramatically impact yield outcomes [

3]. The limited availability of post-emergence herbicide options for pulse crops, combined with lentils’ susceptibility to herbicide phytotoxicity, necessitates precise pre- and post-emergence applications guided by accurate spatial weed distribution mapping [

5].

Recent advances in deep learning and precision agriculture technologies have enabled the development of novel weed detection and mapping frameworks utilising high-resolution drone imagery. These frameworks, supported by convolutional neural networks (CNNs), offer high accuracy in object detection, even in challenging field conditions [

1,

2,

6]. Furthermore, integrating drone imagery with spatial analysis methods, such as kriging, allows researchers to generate predictive maps of weed infestation patterns, providing valuable input for site-specific herbicide applications and enabling the transition from uniform to spatially variable management strategies.

Weed detection methodologies have evolved from traditional image processing to sophisticated deep learning architectures. This transition has been particularly impactful for precision agriculture applications utilising drone imagery for seedling and weed detection [

7]. The YOLO (You Only Look Once) family of object detectors and SAHI (Slicing Aided Hyper Inference) methodology represent cutting-edge approaches that address the unique challenges of detecting small objects in high-resolution agricultural imagery, particularly during critical early growth stages when morphological differences between species are most pronounced.

YOLO architectures revolutionised object detection by reframing it as a single regression problem rather than a multi-stage pipeline [

8]. This unified approach offers significant advantages for agricultural applications: real-time processing capabilities, utilisation of global contextual information, and computational efficiency essential for field deployment. The architecture has evolved substantially since its introduction, with each iteration addressing limitations of previous versions. As Jocher et al. [

9] demonstrated, YOLOv8 introduced a modular architecture that supports multiple vision tasks. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [

10] developed YOLOv11 with advanced attention mechanisms and sophisticated feature fusion strategies, which are particularly beneficial for detecting small objects in complex agricultural environments.

Despite these advances, detecting small seedlings in high-resolution drone imagery presents persistent challenges: scale disparity between objects and image dimensions, feature dilution through convolutional layers, contextual ambiguity of small objects against variable soil backgrounds, computational constraints of processing large images, and class imbalance in agricultural fields where crop and weed densities vary substantially [

11]. The SAHI methodology, developed by Akyon et al. [

12], addresses these limitations through a systematic approach: dividing large images into smaller, overlapping slices, processing each slice independently, mapping predictions back to their original coordinates, merging overlapping detections using non-maximum suppression, and compiling unified outputs. This approach transforms the complex task of detecting small seedlings in large images into more manageable detection problems while preserving spatial context.

Empirical evaluations demonstrate SAHI’s effectiveness across diverse applications, with performance improvements of 6.8%, 5.1%, and 5.3% in Average Precision for various detectors, increasing to 12.7%, 13.4%, and 14.5% when combined with slicing-aided fine-tuning [

12]. Recent agricultural implementations have validated SAHI’s utility for crop monitoring, with successful applications in oil palm counting [

13], apple bud detection [

14], and cacao tree identification [

15]. For agricultural applications, SAHI offers improved recall for small objects, better discrimination in high-density regions, reduced memory requirements, and potential for parallelisation. These benefits come with trade-offs: increased computational overhead, potential boundary artefacts, reduced global context, and parameter sensitivity requiring careful optimisation.

Recent research has focused on integrating these technologies with broader precision agriculture frameworks that enable multi-scale assessment capabilities. Joalland et al. [

16] demonstrated that low-altitude drone scouting at approximately 1.5 meters yields ultra-high-resolution imagery capable of distinguishing individual seedlings, albeit with a limited coverage area. Integration with satellite-derived vegetation indices, particularly NDVI anomalies from Sentinel-2, enables more efficient resource allocation by directing drone flights to areas of interest [

17]. This multi-scale approach leverages complementary strengths of different remote sensing platforms to provide comprehensive information for precision agriculture applications, enabling cost-effective reconnaissance across extensive areas, followed by targeted high-resolution assessment.

The integration of artificial intelligence with geostatistical analysis represents a significant advancement in translating point-based detection outputs into spatially continuous, management-ready information. Traditional geostatistical methods, including kriging and spatial autocorrelation analysis, provide robust frameworks for understanding spatial patterns in agricultural systems [

18]. When combined with AI-based detection, these methods enable characterisation of environmental drivers influencing weed distribution patterns, facilitating predictive modelling and site-specific management optimisation [

19].

Comprehensive evaluations of YOLO detectors for weed detection have found YOLOv8l to achieve a precision of 0.9476 and a mAP@0.5 of 0.9795 [

20], although performance varies with field conditions and species morphology. Deep learning approaches consistently outperform traditional methods, with CNNs demonstrating superior accuracy and generalisation compared to classical machine learning techniques [

21,

22]. However, the integration of detection outputs with spatial analysis for management decision-making remains an active area of development.

Despite significant progress, dos Santos Ferreira et al. [

23] identified persistent challenges in environmental variability management, species discrimination, handling occlusion and overlap, computational efficiency, annotation burden, domain adaptation, and integration with farm management systems. Emerging research directions include self-supervised learning to reduce annotation requirements, multi-modal fusion for improved robustness, temporal modelling across sequential flights, more sophisticated attention mechanisms, efficient neural architecture search, few-shot learning for new species, explainable AI for interpretability, and edge computing for real-time applications [

24].

The integration of these technologies with broader precision agriculture systems represents the next frontier, enabling closed-loop systems connecting detection to variable-rate application equipment, comprehensive decision support platforms, predictive modeling for crop development, autonomous robotics for precision interventions, digital twins for simulation and optimization, and collaborative platforms for data sharing across farms [

24]. Particularly for pulse crop production, where herbicide options are limited and application timing is critical, such integrated systems offer substantial potential for optimising management efficiency while reducing environmental impacts.

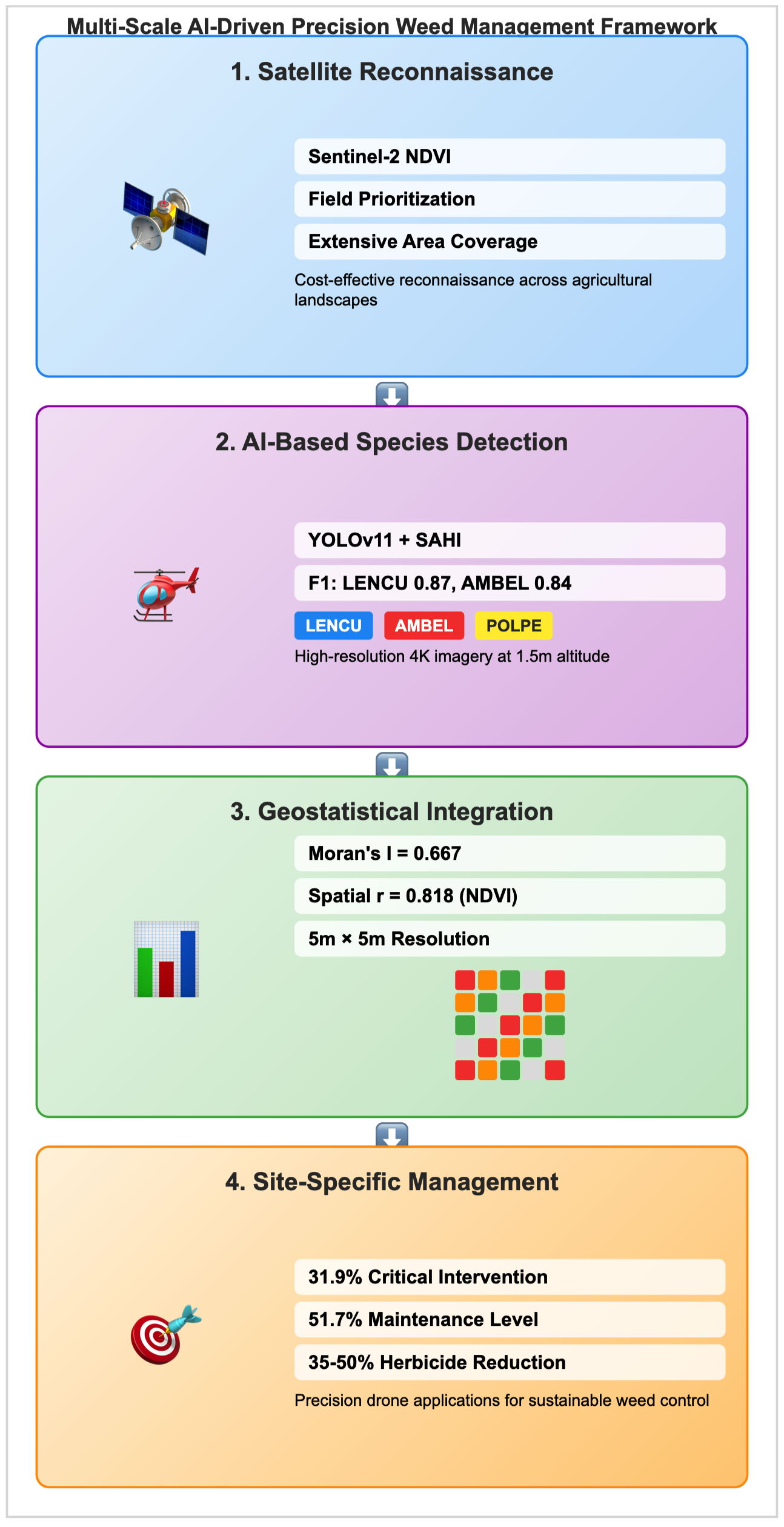

This study addresses the critical gap between AI-based weed detection and practical implementation in precision agriculture by integrating YOLOv11 object detection with the SAHI framework and geostatistical analysis for comprehensive spatial characterisation of weed-environment relationships in lentil production systems. The demonstrated framework enables transition from extensive area reconnaissance using satellite imagery to precise field-level interventions, supporting evidence-based management decisions that optimise herbicide applications while maintaining effective weed control. This technological trajectory, from traditional image processing to sophisticated AI-driven approaches integrated with spatial analysis, provides the foundation for more precise, efficient, and sustainable agricultural practices in pulse crop production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Conditions

The study was conducted in the Central Irrigated Valley of Chile, within a 3.42-hectare experimental site located near Chillán, Ñuble Region, at UTM coordinates 239265.90 E, 5953078.30 N (Zone 19S). This region is one of the principal lentil production zones in central Chile. It is characterised by hot summers and dry conditions, with high solar radiation, while winters are cold and wet, resulting in substantial intra-annual variations in precipitation and evapotranspiration. Over the eight-year crop rotation period (2016–2023), the mean annual temperature ranged from 12.8 to 13.7°C, with yearly rainfall varying between 563 and 1209 mm, and annual potential evaporation from 925 to 1077 mm (

Table 1).

To contextualise crop and weed development during the 2024–2025 season, high-resolution agrometeorological data were retrieved from an INIA weather station located approximately 500 m from the experimental field. From 24 May 2024 to 8 May 2025, the site exhibited a mean air temperature of 12.9°C (range: –5.3 to 37.3°C), with an average relative humidity of 82.6%. Surface temperatures varied from –7.4°C to 48.8°C, and incoming solar radiation averaged 198 W m−2, peaking at 1028 W m−2. Hourly cumulative precipitation averaged 0.11 mm, with isolated rainfall events reaching up to 16.8 mm h−1.

Between 24 May and the sowing date (26 August 2024), a total of 640.5 mm of precipitation was recorded, providing adequate soil moisture reserves ahead of lentil planting. From sowing to UAV-based weed imaging on 17 September, an additional 27.0 mm of rainfall was accumulated—sufficient to support seedling emergence but limited enough to emphasise the importance of pre-sowing moisture conditions.

To further assess early-season dynamics, two phenologically critical windows were examined. The first, spanning 19 August to 2 September 2024 (one week before and after sowing), was characterized by a mean air temperature of 7.0°C (range: –1.7 to 18.8°C), high relative humidity (mean: 93.9%), and modest solar radiation (124 W m−2). Surface temperatures averaged 7.1°C, and hourly precipitation remained low (mean: 0.10 mm).

The second window, from sowing to UAV image acquisition (26 August to 17 September), exhibited slightly warmer conditions (mean air and surface temperatures: 8.8°C and 9.9°C, respectively) and increased radiation (160 W m−2). Relative humidity remained high (90.5%), while rainfall was sparse (27.0 mm total), reinforcing the reliance on antecedent soil moisture. These conditions favoured lentil emergence and early weed development, setting the stage for spatial distribution analyses described in later sections.

The second window spanned from planting to UAV-based weed imaging (August 26 to September 17, 2024), a period critical for early crop–weed interactions. During this time, air and surface temperatures averaged 8.8°C and 9.9°C, respectively, with relative humidity at 90.5%. Solar radiation increased to a mean of 160 W m−2, promoting seedling development. Precipitation remained sparse (mean: 0.05 mm h−1), suggesting limited but sufficient soil moisture retention following earlier rainfall. These conditions favoured both lentil emergence and early weed establishment, thereby setting the stage for spatial weed pattern analyses presented later in this study.

The soil at the site is classified as a Melanoxerand of volcanic origin, typical of Andisols found across south-central Chile [

25]. These soils are well known for their low bulk density, moderate acidity, high porosity and organic matter content. The site’s physical and hydric properties include a bulk density of 1.00 g cm

−3, pH 5.52, and particle size distribution of 16.7% clay, 44.6% silt, and 38.7% sand (

Table 2). The low electrical conductivity (0.11 dS m

−1) indicates minimal salinity stress. These attributes are conducive to lentil establishment and influence spatial patterns of early weed emergence and soil–crop interactions [

26].

Management history before the 2024 lentil crop included winter wheat cultivation in 2022 and a fallow period in 2023. In 2024, lentils (Lens culinaris Medik., cv. Super Araucana-INIA) were sown using conventional tillage practices. Super Araucana-INIA, developed by the Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIA), is well adapted to Chilean conditions due to its early maturation, drought tolerance, and high market acceptance. Crop was sown on 26 August 2024 under conventional tillage using a seeder configured for a row spacing of 35 cm. The seeding rate was 80 kg ha−1, which corresponds to an expected plant density of 70–80 plants per square meter under optimal germination and emergence conditions. This plant density is considered agronomically ideal for lentils in the Central Irrigated Valley, as it balances canopy closure with reduced intra-specific competition and lodging risk.

At planting, a uniform basal fertilisation was applied consisting of 120 kg ha

−1 of triple superphosphate (TSP,

superfosfato triple), a concentrated source of phosphorus with a typical composition of 46% P

2O

5, and 80 kg ha

−1 of nitrogen. This fertilisation strategy aimed to correct for the low to moderate inherent phosphorus availability of the volcanic Andisols in the region [

26], and to support early root development and nodulation in the absence of residual N from the prior fallow season. All inputs were uniformly applied using calibrated ground-based spreaders to ensure consistency across the experimental plots.

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.2.1. Drone-Based Imagery Capture

High-resolution RGB images were acquired on 17 September 2024, between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m., under optimal environmental conditions (clear sky, no clouds, and intense solar illumination). The imagery campaign was conducted using a DJI Mavic Mini 3 UAV (DJI Technology Co., Shenzhen, China), a lightweight, consumer-grade drone equipped with a 1/1.3-inch CMOS sensor capable of capturing 48-megapixel still images at a native resolution of 8064 × 6048 pixels.

The camera features an 82.1° field of view (FOV) and a fixed 24 mm format-equivalent lens with an aperture of f/1.7 and an electronic shutter capable of speeds between 2 and 1/8000 s. During the flight, the shutter speed was set to 1/5000 s to minimise motion blur under bright conditions. The drone was flown manually at a constant altitude of 1.5 m above ground level, with a forward velocity of 8 km h−1. Images were captured at a frequency of one photograph every 2 seconds using the Single Shot mode in RAW (DNG) format to preserve radiometric fidelity. The UAV was manually piloted along transects oriented in the east-to-west direction, aligned with the lentil crop rows to maintain a consistent nadir view and reduce occlusion effects from row geometry. The flight trajectory and image capture interval (one frame every 2 seconds) at a ground speed of 8 km h−1 and an altitude of 1.5 m resulted in a forward image spacing of approximately 5 m. Adjacent flight lines were spaced 7 m apart, yielding a systematic image acquisition grid with near-complete coverage of the field and minimal overlap. This configuration ensured that each image captured a ground footprint of 3.29 m2, enabling the quantification of weed densities on a per-square-meter basis while maintaining efficient field coverage under manual flight conditions.

At the operational altitude of 1.5 m, the effective ground coverage (footprint) of the camera’s FOV was approximately 3.29 m2 per image. This field-of-view estimate was used to standardise the quantification of weed density per square meter by direct annotation and detection over individual frames. The UAV operated under manual flight mode to optimise navigation in row-crop layout and minimise occlusion artefacts caused by canopy overlap or terrain undulation.

All images were later processed using semi-automated object detection pipelines (detailed in

Section 3.1.1) to extract weed occurrence metrics for downstream spatial analyses.

2.2.2. Satellite-Derived NDVI Acquisition and Grid Harmonization

Two Sentinel-2 Level-2A multispectral scenes were acquired on 14 and 24 September 2024 (NDVI_14S and NDVI_24S, respectively). Such images in 10 m native resolution were retrieved using the Pix4Dfields platform (version 2.1; Pix4D S.A., Prilly, Switzerland). Both scenes showed full coverage of the experimental site and were cloud-free (<1%) [

27]. The imagery was selected and downloaded directly through the Pix4Dfields “Satellite Data” interface, which enables users to access pre-processed Sentinel-2 scenes by specifying the spatial boundary of interest. In this case, the field boundary polygon for the 3.42-hectare lentil trial was preloaded into the application as a shapefile and used to constrain all downloads to the experimental block. Pix4Dfields automatically generates vegetation indices, including the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), from Sentinel-2 bands using the standard formulation:

where

and

represent the atmospherically corrected reflectance values of bands 8 (842 nm) and 4 (665 nm), respectively [

28]. NDVI rasters were downloaded directly in a 5 m × 5 m grid format, as supported natively by Pix4Dfields for Sentinel-2 data. This functionality avoids the need for post hoc resampling and ensures alignment with UAV-derived products used throughout the spatial analysis workflow.

All NDVI layers were projected in UTM Zone 19S and subsequently aligned with UAV-based weed maps and soil electrical conductivity rasters. The harmonized resolution enabled integration across datasets and supported the generation of spatial covariates for geostatistical modelling of weed–soil–vegetation interactions.

2.2.3. Soil Electrical Conductivity

Soil apparent electrical conductivity (EC

a) was measured using the EM38-MK2 instrument (Geonics Ltd., Mississauga, ON, Canada), a dual-depth electromagnetic induction sensor widely used in precision agriculture and digital soil mapping applications [

29,

30,

31]. The instrument was operated in vertical dipole mode, providing EC

a readings corresponding to two effective soil depths: 0–75 cm (

CE_75CM) and 75–150 cm (

CE_150CM). These measurements are sensitive to variations in soil texture, moisture, bulk density, and salinity, offering valuable proxies for subsurface heterogeneity that affects crop growth and weed dynamics.

The survey followed a systematic grid layout across the 3.42 ha lentil field. Each point was georeferenced using a GNSS-enabled data logger integrated with the EM38 system to ensure spatial accuracy. The EM38 scanning was performed along linear transects oriented in the east-to-west direction, parallel to the lentil crop rows. This alignment minimised potential electromagnetic interference caused by row structure and facilitated consistent sensor positioning relative to plant spacing. Within each transect, apparent electrical conductivity measurements at both 0–75 cm and 75–150 cm depths were collected at 2.5 m intervals. The scanning lines themselves were spaced 12 m apart, providing uniform coverage across the paddock. This sampling configuration strikes a balance between spatial resolution and operational efficiency, ensuring sufficient data density for accurate interpolation while allowing for complete coverage of the entire field within a single survey session.

2.2.4. Crop and Weed Seedling Identification at Early Developmental Stages

To support accurate weed detection and distinguish crop plants from unwanted species, a ground-based botanical survey was conducted before UAV imaging. Manual scouting was performed on foot by expert agronomists to visually confirm seedling identity, development stage, and spatial distribution across the field. Observations focused on the cotyledon and early leaf stages (BBCH 10–14), aligning with the expected phenological window at 22 days after sowing (DAS). All taxa were documented using EPPO Global Database codes for standardisation in the image annotation workflow.

By the time of scouting and drone imaging, most lentil plants were in the BBCH 12–14 stage, characterised by the emergence of two to four alternate pinnate leaves. Cotyledons were hypogeal and not visible at this stage. [

32].

The dominant weed species observed were:

Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. (EPPO code:

AMBEL): Seedlings appeared in BBCH stages 10–14. Cotyledons were large, opposite, and spatulate, while the first true leaves were ovate to deeply lobed and densely pubescent. This morphology is key to differentiating from lentil in early imagery [

33,

34].

Polygonum persicaria L. (

POLPE): Observed at BBCH 10–12, with narrow lanceolate cotyledons and reddish, ovate first leaves. A diagnostic ochrea was consistently visible at the stem node [

35].

Polygonum aviculare L. (

POLAV): Detected in BBCH 10–12. Cotyledons were linear-elliptical; the true leaves were alternate, oblong, glabrous, and often tinged red at the node, aiding visual distinction [

36].

Figure 1 presents typical seedlings of the crop and weeds as recorded during the field inspection. A morphological comparison across species and developmental traits is provided in

Table 3.

2.3. AI-Based Weed Detection Framework

The development of an accurate and robust AI-based weed detection system required a systematic approach encompassing dataset curation, model architecture optimisation, and deployment strategies tailored explicitly for high-resolution agricultural imagery. This framework addresses the critical challenge of detecting small-scale plant instances across extensive field areas while maintaining computational efficiency and spatial precision necessary for precision agriculture applications.

2.3.1. Dataset Development and Curation

A comprehensive training dataset was previously constructed from high-resolution imagery collected over three consecutive growing seasons (2020–2022) across adjacent commercial lentil paddocks. Image acquisition employed a Canon EOS Rebel T5i DSLR camera (Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an EF-S 18–55mm f/3.5–5.6 IS STM lens, operated at consistent technical specifications to ensure dataset homogeneity (

Table 4).

The dataset comprises 445 georeferenced images (5184 × 3456 pixels each) captured under diverse environmental conditions to ensure model robustness across varying illumination, soil moisture, and phenological stages. Acquisition conditions systematically varied across: (i) solar elevation angles from 35° to 75°, (ii) soil moisture levels from field capacity to permanent wilting point, and (iii) crop development stages from BBCH 12 (first true leaf) to BBCH 15 (fifth leaf unfolded).

Taxonomic annotation was performed by two certified agronomists from the Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIA) using the Roboflow annotation platform (Roboflow Inc., Des Moines, IA, USA). The annotation protocol followed standardised botanical identification procedures for the target species:

Lens culinaris Medik. (LENCU),

Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. (AMBEL),

Polygonum persicaria L. (POLPE), and

Polygonum aviculare L. (POLAV). Inter-annotator reliability assessment on a stratified random subset of 50 images yielded Cohen’s

(95% CI: 0.83–0.91), indicating excellent agreement according to Landis and Koch criteria [

37].

2.3.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation Strategy

To optimise computational efficiency while preserving spatial resolution critical for small object detection, input images were standardised to 2048 × 2048 pixels using bicubic interpolation. This resolution represented an optimal trade-off between detection accuracy and computational requirements, determined through preliminary experiments with resolutions ranging from 1024 to 3072 pixels.

A systematic data augmentation strategy was implemented to enhance model generalisation and robustness to field variability. The augmentation pipeline applied stochastic transformations with carefully calibrated probabilities:

The augmentation factor of 4× expanded the effective training set to 1,780 images while maintaining annotation integrity through the use of coordinate transformation matrices.

The final annotated and augmented dataset contained 30,359 bounding box instances distributed across the four target classes, with natural class imbalance reflecting field conditions: LENCU (45.2%), AMBEL (28.6%), POLPE (16.8%), and POLAV (9.4%). Instance size distribution analysis revealed mean bounding box areas of 1,847 ± 892 pixels2 for LENCU and 1,203 ± 567 pixels2 for weed species, with 78% of all instances classified as small objects (area < 322 pixels at inference resolution).

2.3.3. Model Architecture and Training Protocol

We employed the YOLOv11 architecture [

38], specifically the YOLOv11x variant optimised for detection accuracy, suitable for small object detection in agricultural applications. The model incorporates several architectural innovations, including:

C2f (Cross Stage Partial with 2 convolutions) modules for enhanced feature extraction

SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast) for multi-scale feature fusion

Path Aggregation Network (PANet) for improved information flow

Anchor-free detection head with distribution focal loss

Training was conducted on a high-performance computing system comprising dual NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPUs (each with 24 GB of VRAM) running Ubuntu 24.04 LTS. The software environment consisted of Python 3.10.12, PyTorch 2.4.1 with CUDA 12.1, and the Ultralytics framework v8.3.49. Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) training was implemented to efficiently leverage both GPUs.

The optimisation protocol employed AdamW optimiser with the following hyperparameter configuration:

Training proceeded for 300 epochs with early stopping (patience = 50 epochs) based on validation mAP@0.5:0.95.

2.3.3.1. Validation Strategy

Model performance was systematically evaluated on the held-out validation portion of the dataset (15% of total annotations) using standard object detection metrics. The validation set maintained the same class distribution and spatial characteristics as the training data while ensuring complete independence from training samples.

Model performance was evaluated using standard object detection metrics:

Where , , and represent true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively, and is the average precision for class i at IoU threshold 0.5.

2.3.3.2. Model Selection Criterion

The optimal deployment model was selected based on the highest combined precision-recall performance across all five training runs. Specifically, the model achieving the maximum harmonic mean of precision and recall (F1-score) aggregated across all target classes was chosen:

where

represents the F1-score for class

i in training run

r, and

target classes. This selection approach prioritises balanced detection performance, minimising both false positives (important for avoiding unnecessary herbicide applications) and false negatives (critical for effective weed control) across all species.

2.3.4. Model Deployment and Inference Pipeline

Trained models were deployed on 4K drone imagery (3840 × 2160 pixels) captured on September 17, 2024. To address the computational challenges of processing ultra-high-resolution imagery while maintaining detection accuracy for small objects, we implemented the Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) framework [

39].

2.3.4.1. Slicing Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) Implementation

The SAHI framework addresses the challenge of detecting small objects in ultra-high-resolution imagery:

The SAHI algorithm segments large images into overlapping patches of optimal size, processes each patch independently, and merges results using Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS). The slicing parameters were optimised as follows:

The inference pipeline incorporated several optimisation strategies:

Memory management: Patch-wise processing with automatic garbage collection to prevent CUDA out-of-memory errors

Multi-scale detection: Consistent slice dimensions matching training resolution to preserve learned feature representations

Geospatial integration: Preservation of EXIF metadata and coordinate system transformations using the utm library

Post-processing operations included coordinate transformation from image space to geographic coordinates (UTM Zone 19S, EPSG:32719) and export to multiple geospatial formats (GeoJSON, Shapefile, and CSV) using GeoPandas v0.14.0. World files (.jgw) were generated for seamless integration with QGIS 3.38.1, enabling direct visualisation and spatial analysis of detection results.

2.4. Geostatistical Analysis Workflow

2.4.1. Data Processing and Integration

To comprehensively characterise the spatial variability within the study area, multiple data sources were integrated within a Geographic Information System (GIS) framework using QGIS 3.28 (QGIS Development Team, 2023) for simultaneous visualisation. This multi-layered approach enabled the spatial overlay and co-registration of complementary datasets, facilitating an initial identification of spatial relationships and patterns that would not be apparent when analysing individual data sources in isolation. The integrated GIS platform served as the foundation for subsequent spatial analysis.

2.4.2. Spatial Data Structure and Preprocessing

All spatial analyses were performed using a standard coordinate reference system (UTM Zone 19S, EPSG:32719) to ensure consistent spatial registration across data sources. Original coordinate data collected in WGS84 (latitude/longitude) were transformed to UTM using the PyProj library. For soil electrical conductivity (ECa) measurements from the EM38-MK2 sensor, points were filtered to include only those within the study area boundary.

Weed presence data derived from YOLO detection were processed as point centroids, with each point representing an individual plant occurrence. For the geo-statistical analysis, spatial data processing was implemented using GeoPandas (version 0.14.0) in a Python 3.11 environment.

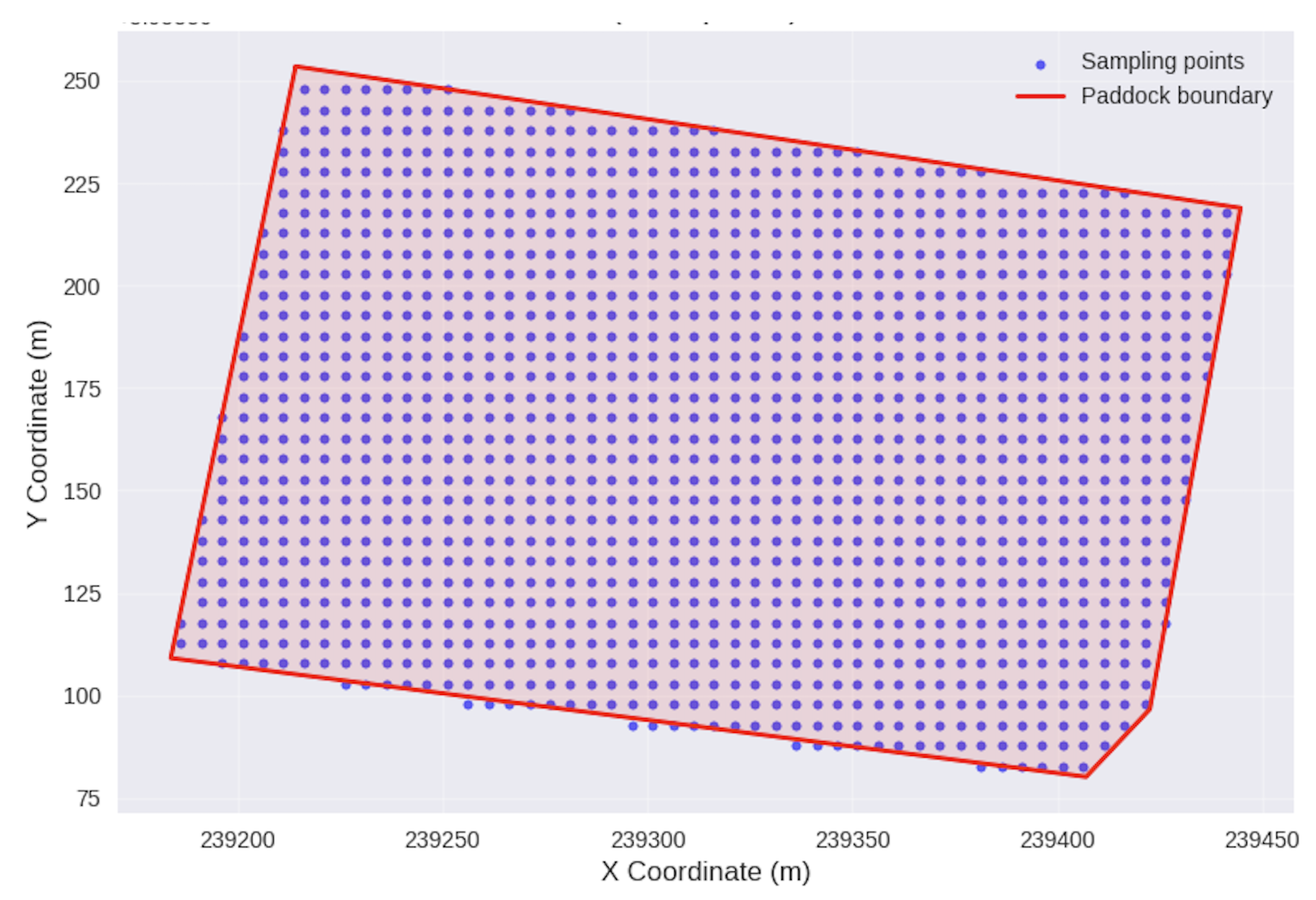

It is worth noting that the interpolation grid size of 5 m × 5 m was chosen to strike a balance between spatial resolution and computational efficiency, as well as practicality for managing herbicide applications using drones. This resolution was validated through variogram analysis as described in Section `Variogram Model Selection and Fitting’.

2.4.3. Geostatistical Analysis and Spatial Interpolation

2.4.3.1. Ordinary Kriging Implementation

Spatial interpolation of all measured variables (weed densities, crop densities, soil electrical conductivity, and vegetation indices) was performed using ordinary kriging following the methodology described by [

40] and implemented through the Smart-Map geostatistical plugin for QGIS [

40]. This approach provides unbiased predictions with minimum estimation variance for spatially correlated data.

2.4.3.2. Variogram Model Selection and Fitting

For each variable, experimental semivariograms were computed and fitted with theoretical models to characterise the spatial dependence structure. Model selection was based on statistical criteria comparing four theoretical models: Linear, Spherical, Exponential, and Gaussian. The optimal model for each variable was selected based on the highest coefficient of determination (R²) and lowest root mean square error (RMSE) from cross-validation analysis.

The spherical model follows the equation:

The exponential model is defined as:

where

is the semivariance at lag distance

h,

is the nugget effect,

c is the partial sill, and

a is the range parameter.

2.4.3.3. Grid Interpolation and Cross-Validation

A systematic 5 m × 5 m interpolation grid was established within the paddock boundaries, resulting in a total of 1,370 prediction points

Figure 3. This resolution was selected to balance computational efficiency with adequate spatial detail for precision agriculture applications. The interpolation procedure utilized the fitted variogram models to estimate values at unsampled locations using the ordinary kriging predictor:

Where is the predicted value at location , are the observed values at sampled locations, and are the kriging weights determined by solving the kriging system.

Leave-one-out cross-validation was performed for each variable to assess interpolation accuracy. Cross-validation parameters including mean error (ME), root mean square error (RMSE), mean standardized error (MSE), and root mean square standardized error (RMSSE) were computed and are presented in the Results section (

Table 7). These statistics provide measures of bias, accuracy, and reliability of the kriging predictions.

2.4.4. Derived Ecological Indices and Community Structure Analysis

Using the unified 5 m × 5 m interpolated grid dataset obtained from the kriging procedure, we calculated additional ecological indices to characterise crop-weed community dynamics and support site-specific management decisions [

41,

42]. These derived variables provide quantitative measures of species dominance, diversity, and competitive relationships within each grid cell following established protocols in weed ecology [

43].

2.4.4.1. Species Dominance and Relative Proportions

Relative abundance indices were calculated for each species to quantify their contribution to the total plant community following the methodology of Barbour et al. [

44]. The proportion of lentil crop was computed as:

where

represents the density (plants m

−2) of each species. Similarly, the relative abundance index (RAI) for each species was calculated as:

These proportional indices enable identification of areas with varying degrees of weed pressure and crop establishment success, providing essential data for precision agriculture applications [

45,

46].

2.4.4.2. Crop-to-Weed Ratio and Competition Assessment

The crop-to-weed ratio (CWR) was computed to quantify the competitive balance between lentil and weed species, following the competitive indices framework established by Weaver [

47] and Cousens and Mortimer [

41]:

Values of CWR > 1 indicate crop dominance, while CWR < 1 suggests weed dominance, providing a direct metric for prioritizing site-specific management interventions [

48,

49].

2.4.4.4. Weed Pressure Classification

Grid cells were classified into weed pressure categories based on total weed density thresholds established from field observations and agronomic literature [

48,

54]. The classification follows established thresholds for pulse crop systems [

55]:

High pressure: Total weed density >100 plants m-2

Medium pressure: Total weed density 50–100 plants m-2

Low pressure: Total weed density <50 plants m-2

This classification provides a foundation for preliminary site-specific weed management (SSWM) zone delineation and helps prioritize areas requiring immediate intervention [

45,

56].

2.4.5. Global and Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Spatial autocorrelation in the gridded variables was quantified using Global Moran’s I statistic:

where

n is the number of spatial units,

W is the sum of all spatial weights

,

and

are the values of the variable at locations

i and

j, and

is the mean of the variable. Spatial weights were defined using the first-order queen contiguity criterion and row-standardised. Statistical significance was assessed through a Monte Carlo permutation approach with 9,999 random spatial reconfigurations.

We calculated Moran’s I for seven key variables: AMBEL, POLPE, POLAV, LENCU, CE_75CM, NDVI_2024_, and NDVI_diff. The magnitude of Moran’s I ranges from -1 (perfect dispersion) through 0 (random pattern) to +1 (perfect clustering), with statistical significance evaluated against the null hypothesis of spatial randomness.

2.4.6. Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) Analysis

To identify local patterns of spatial association and clustering within the interpolated datasets, we applied Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis [

57]. This technique decomposes global spatial autocorrelation into contributions from individual locations, allowing for the identification of statistically significant spatial clusters and outliers.

Univariate LISA Implementation

For each ecological variable in the unified 5 m × 5 m grid dataset, we calculated the local Moran’s I statistic:

where

is the local Moran’s I for location

i,

n is the total number of observations,

and

are variable values at locations

i and

j,

is the global mean, and

are the spatial weights. Spatial weights were constructed using K-nearest neighbours (k=8) with row standardisation to ensure consistent neighbourhood definitions across the study area [

58].

Statistical significance was assessed through conditional permutation tests with 999 randomizations, and p-values were evaluated at

. Each grid cell was classified into one of four LISA categories based on the local association pattern [

57]:

High-High (HH): Hotspots - locations with above-average values surrounded by neighbors with above-average values

Low-Low (LL): Coldspots - locations with below-average values surrounded by neighbors with below-average values

High-Low (HL): Spatial outliers - high values surrounded by low values

Low-High (LH): Spatial outliers - low values surrounded by high values

2.4.6.2. Bivariate LISA Analysis

To examine spatial relationships between pairs of ecological variables, we implemented bivariate LISA using the bivariate local Moran’s statistic [

57,

59]:

where

and

are standardized values of variables

x and

y at locations

i and

j, respectively. This statistic identifies areas where high (or low) values of one variable spatially associate with high (or low) values of another variable.

Key bivariate relationships analyzed included:

Weed species densities vs. soil electrical conductivity (AMBEL-CE_75CM, POLPE-CE_150CM)

Weed densities vs. vegetation indices (species-NDVI relationships)

Crop-environment interactions (LENCU-CE_75CM, NDVI-CE_75CM)

Temporal vegetation dynamics (NDVI_14Sep vs. NDVI_24Sep)

For each variable pair, we calculated both the global Pearson correlation coefficient and the percentage of field area exhibiting significant spatial co-occurrence patterns. Significance was assessed using permutation-based inference with 999 randomizations [

57].

2.4.7. Fuzzy Clustering for Management Zone Delineation

Traditional hard clustering approaches for management zone delineation often fail to capture the gradual transitions characteristic of agricultural landscapes [

60]. To address this limitation, we implemented fuzzy K-means clustering with objective optimization criteria specifically designed for precision agriculture applications.

2.4.7.1. Fuzzy Clustering Optimization

The optimal number of clusters was determined using two complementary criteria [

58,

59]:

Fuzzy Performance Index (FPI): Measures the degree of separation between clusters, with lower values indicating better-defined management zones:

Normalized Classification Entropy (NCE): Quantifies partition fuzziness, with lower values indicating crisper cluster boundaries suitable for practical implementation:

where is the fuzzy membership of point i in cluster j, k is the number of clusters, and n is the number of data points.

The optimal cluster number was selected by minimizing the combined FPI + NCE score across candidate solutions (k = 2 to 8), ensuring both statistical robustness and practical implementability for variable-rate applications [

59].

2.4.7.2. Species-Specific Clustering Analysis

Two distinct clustering analyses were performed focusing on different ecological aspects:

- (1)

Weed Species Distribution Clustering: Applied to the three dominant weed species (AMBEL, POLPE, POLAV) plus total weed density and Shannon diversity index

- (2)

Environmental Gradient Clustering: Applied to soil electrical conductivity (75cm and 150cm depths), vegetation indices (NDVI_14S, NDVI_24S, NDVI_diff), and crop-to-weed ratio

For each analysis, variables were standardized before clustering to ensure equal weighting regardless of measurement units [

63].

2.4.8. Priority-Based Intervention Zone Development

Management intervention zones were developed by integrating LISA spatial significance results with fuzzy clustering outcomes, creating a scientifically robust framework for precision agriculture implementation [

45,

64].

2.4.8.1. Priority Classification System

Each grid cell was assigned to one of four intervention priority levels based on a composite scoring system:

Critical Priority: LISA High-High clusters with fuzzy membership certainty >0.8, requiring immediate intensive intervention

High Priority: LISA hotspots or spatial outliers (High-Low, Low-High) with moderate fuzzy membership certainty

Medium Priority: Areas with low fuzzy membership certainty (<0.6) requiring enhanced monitoring and adaptive management

Low Priority: LISA Low-Low clusters representing successful current management practices

Priority scores were calculated using statistical percentile ranking of total weed pressure (60% weight) and dominant species density (40% weight), providing objective, quantitative criteria for intervention prioritization [

41].

2.4.8.2. Botanical Composition Analysis

Within each management zone, we characterized weed community structure following established ecological protocols [

44]:

Dominant species: Species with highest mean density within the zone

Co-dominant species: Secondary species achieving higher than 30% of dominant species density

Shannon diversity index: Community complexity measure calculated as

Species ranking: Hierarchical ordering by mean density within zone

This detailed composition analysis enables species-specific herbicide selection and application timing optimization, addressing the distinct ecological requirements and susceptibilities of different weed species [

60,

66].

2.4.9. Software Implementation

All analyses were implemented using open-source software to ensure reproducibility. The primary software stack included:

Python 3.11 with scientific computing libraries (NumPy 1.24.0, SciPy 1.10.0, pandas 2.0.0)

Geospatial analysis: GeoPandas 0.14.0, PySAL 24.1, Shapely 2.0.0

Spatial statistics: ESPy (Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis), libpysal

Machine learning: scikit-learn 1.3.0 for fuzzy clustering and PCA

Visualization: Matplotlib 3.7.0, Seaborn 0.12.0

Kriging implementation: Smart-Map plugin for QGIS 3.28 [

40]

Statistical analysis and visualization were performed in Google Colab environment with automated result export to ensure reproducibility and collaborative development.

Spatial data processing, statistical analysis, and visualization were performed in a Jupyter notebook environment to facilitate documentation and reproducibility.

4. Discussion

The integration of artificial intelligence-based object detection with geostatistical analysis provides enhanced spatial resolution and analytical capabilities for precision weed management in agricultural systems. This study presents the first comprehensive application of YOLOv11 coupled with Slicing-Aided Hyper Inference (SAHI) framework for species-specific weed mapping in lentil production, demonstrating significant spatial heterogeneity in weed distributions with measurable environmental associations that enable site-specific management interventions.

4.1. AI-Geostatistics Integration: Performance Evaluation and Methodological Contributions

The deployment of YOLOv11 framework achieved detection performance of F1-score = 0.87 for lentil crop identification and F1-score = 0.84 for the primary target weed species

Ambrosia artemisiifolia (AMBEL), establishing measurable benchmarks for multi-species seedling detection in agricultural environments. These results compare favorably with previous studies employing YOLO architectures for crop-weed discrimination, where reported F1-scores typically range from 0.65 to 0.78 [

61,

62]. The observed performance improvements can be attributed to the SAHI framework’s slice-based inference methodology, which addresses the challenge of detecting small objects in high-resolution drone imagery by subdividing orthomosaic images into overlapping patches for independent processing [

63].

The SAHI framework implementation represents a methodological advancement for agricultural object detection applications. Previous studies have demonstrated SAHI’s effectiveness in improving small object detection performance by 6.8-14.5% across various detection architectures [

63], with recent agricultural applications showing consistent improvements in tree counting and crop monitoring tasks [

64,

65,

66]. In this study, the framework enabled successful processing of 4K drone imagery while maintaining species-level discrimination accuracy of 95% for lentil crops and 88% for

Ambrosia artemisiifolia, despite morphological similarities during early developmental stages.

The integration of AI-derived plant density estimates with geostatistical interpolation onto a standardized 5 m × 5 m grid achieved cross-validation R² values ranging from 0.390 to 0.996, demonstrating compatibility between machine learning outputs and traditional spatial analysis frameworks. The exceptional interpolation performance for vegetation indices (NDVI_24S: R² = 0.996) and soil electrical conductivity measurements (CE_75CM: R² = 0.923) validates the framework’s capacity to integrate multi-source environmental data with biological observations. This multi-layer approach enables mechanistic understanding of weed distribution patterns, addressing limitations identified in previous studies that examined detection accuracy or spatial analysis in isolation [

67].

The successful kriging interpolation of biological variables, with total weed density achieving R² = 0.810 and AMBEL density R² = 0.782, demonstrates that AI-derived detection outputs maintain sufficient spatial structure for geostatistical modeling. This finding enables the transition from point-based detection to continuous surface mapping, providing the spatial framework necessary for precision agriculture applications.

4.2. Spatial Pattern Analysis and Ecological Mechanisms

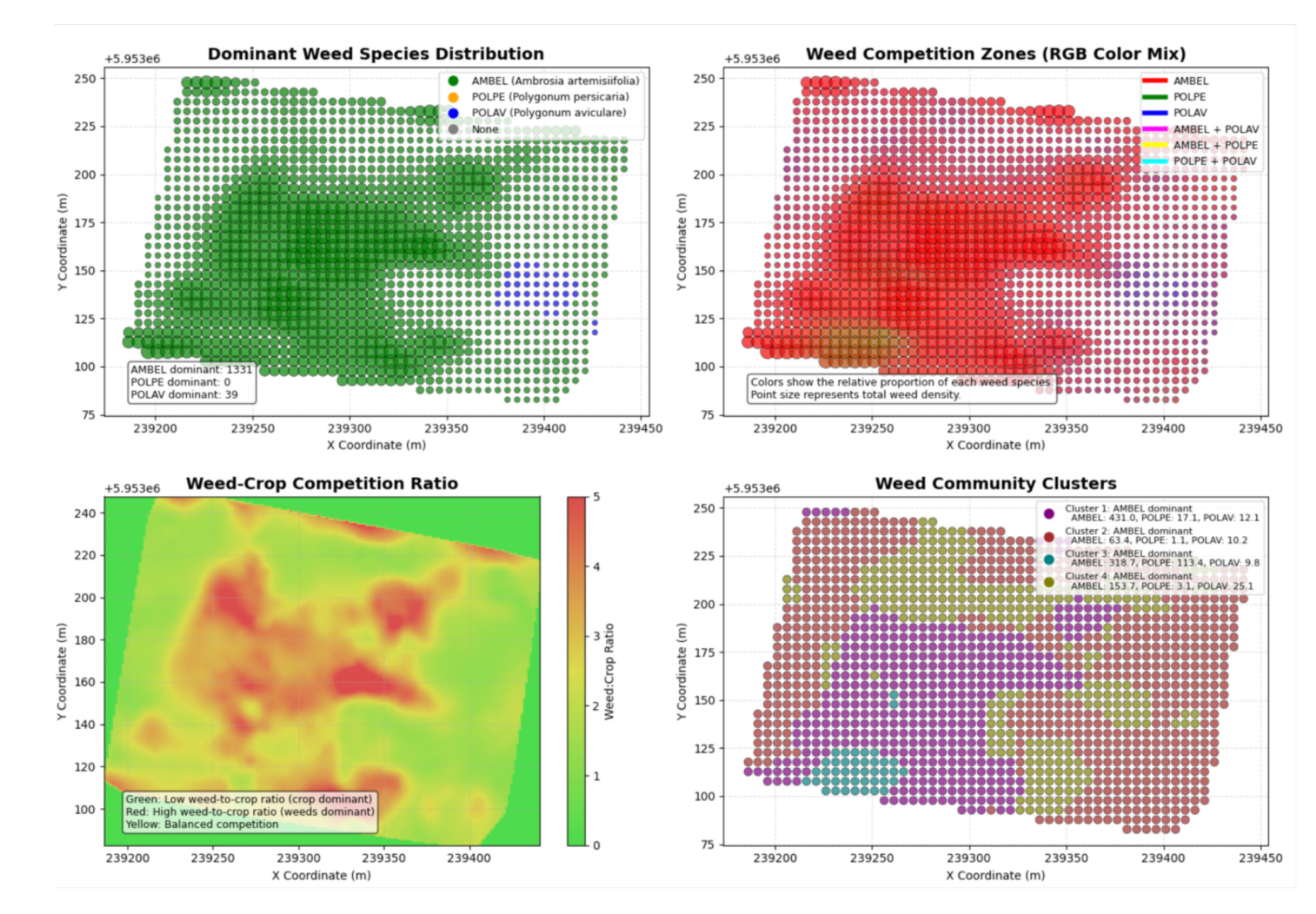

Global spatial autocorrelation analysis revealed significant clustering patterns for all major variables, with AMBEL exhibiting strong spatial autocorrelation (Moran’s I = 0.667, p < 0.001). This finding indicates that weed establishment follows predictable spatial patterns driven by environmental gradients rather than random colonisation processes, contradicting assumptions of spatial independence commonly employed in uniform management approaches [

68]. The observed spatial structure provides empirical support for spatially explicit management protocols and enables predictive modeling of weed distribution patterns.

Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis identified 992 significant local clusters for AMBEL, covering 72.4% of the sampled area. The predominance of Low-Low clusters (43.2% of significant clusters) indicates that the majority of the field maintains natural resistance to weed establishment, while discrete High-High clusters (34.8% of significant clusters) represent focal areas of intensive infestation. This spatial configuration has direct implications for precision herbicide application strategies, suggesting that conventional uniform treatment approaches result in over-application in low-risk areas while potentially under-treating high-density patches.

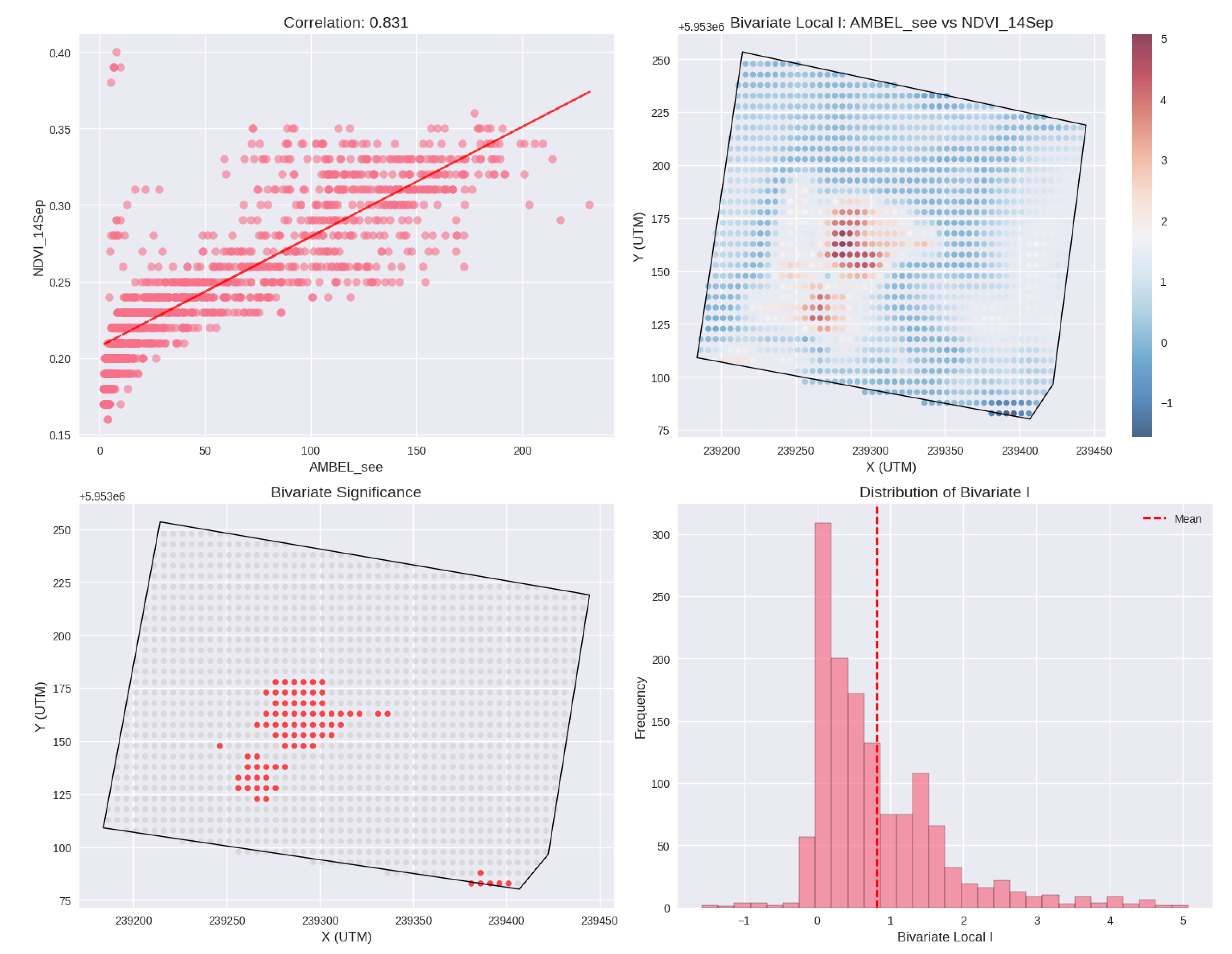

Bivariate spatial association analysis revealed strong co-location between weed density and vegetation vigor indices (AMBEL-NDVI_14S: spatial r = 0.818, 86.4% significant associations), providing insights into environmental drivers of weed establishment. The positive correlation suggests facilitation effects in favorable microsites rather than competitive exclusion, indicating that areas with enhanced growing conditions benefit both crop and weed species. This finding has implications for management strategies, suggesting focus on differential resource access mechanisms rather than creating uniformly hostile environments for weed establishment [

69].

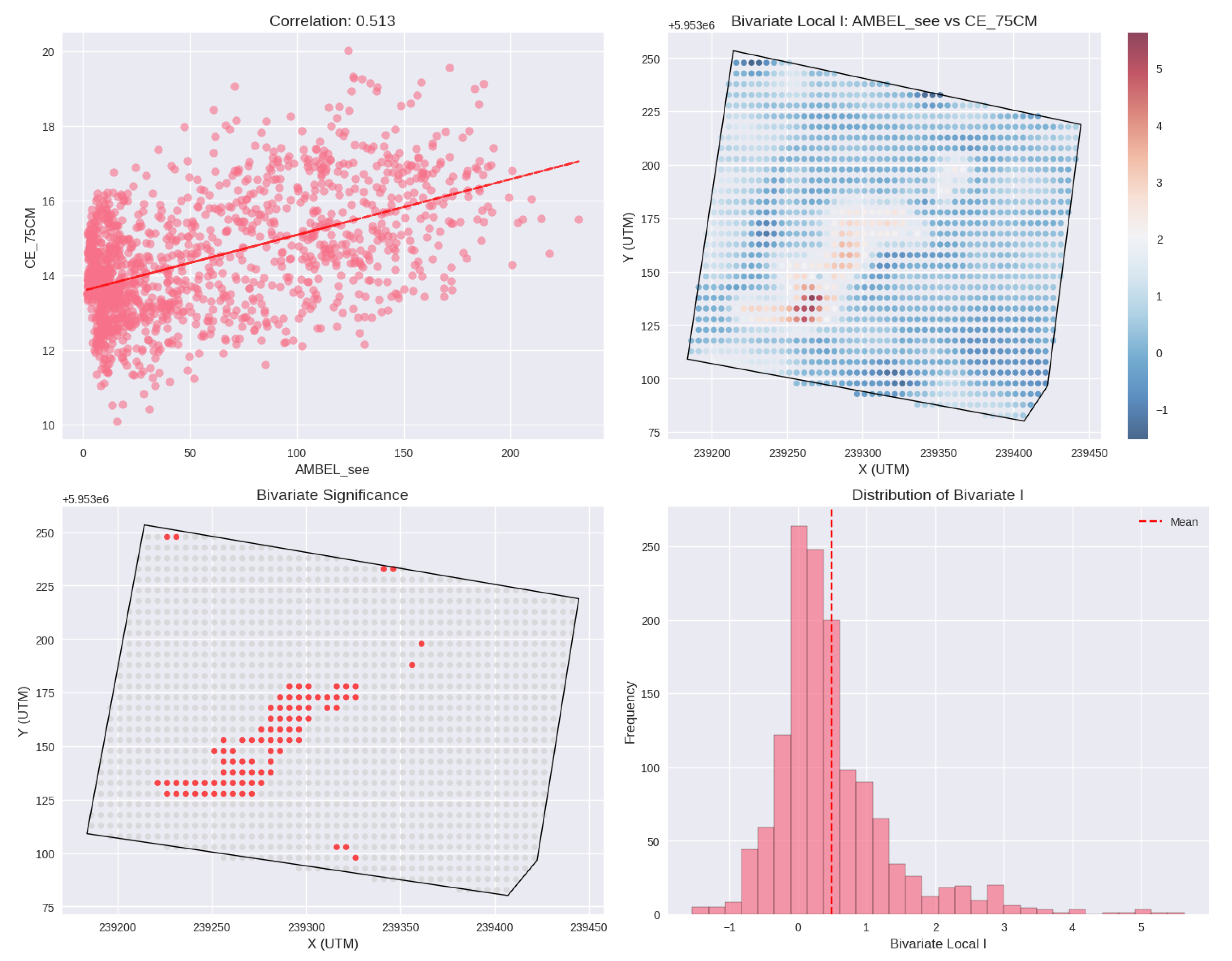

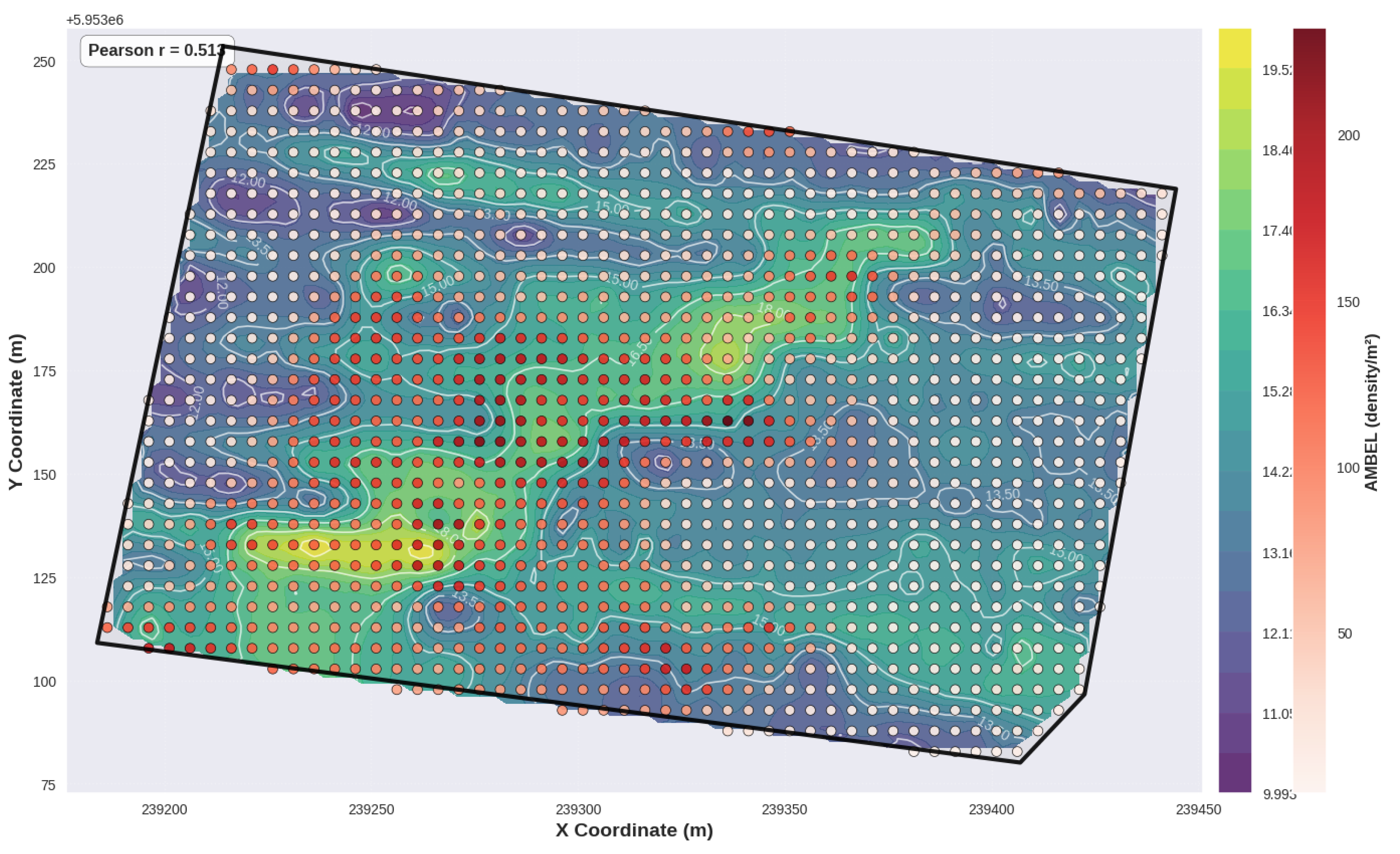

The moderate spatial associations between soil electrical conductivity and weed distributions (AMBEL-CE_75: spatial r = 0.633, 74.3% significant associations) provide predictive capability for management planning. Areas with CE_75CM > 16 mS m

−1 demonstrated 67% higher AMBEL density, suggesting that soil-based risk mapping can guide pre-emergence herbicide applications. This soil-weed relationship likely reflects the influence of soil moisture retention and nutrient availability on seedling establishment success, consistent with previous studies linking soil electrical conductivity to crop vigor and weed pressure patterns [

70].

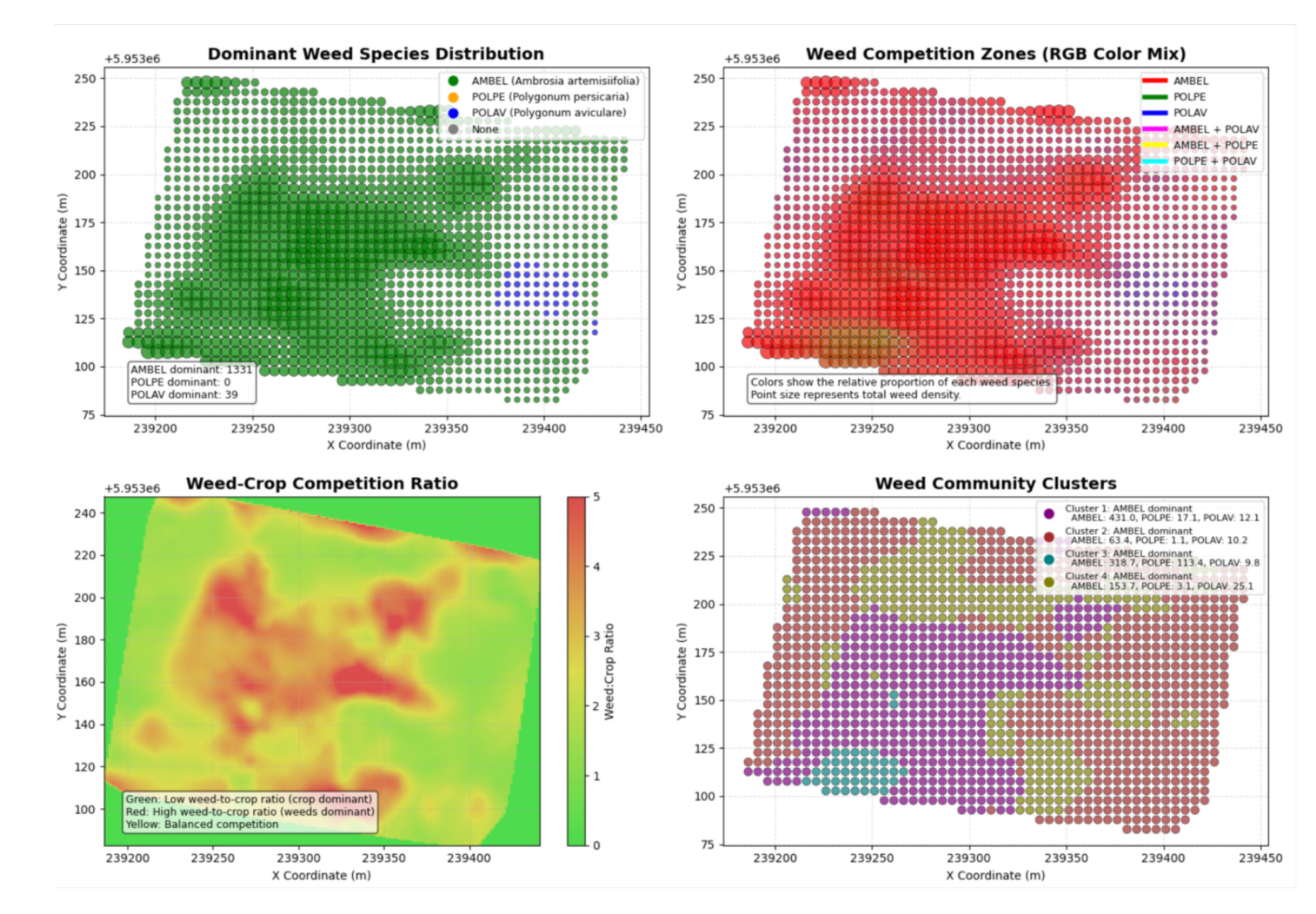

4.3. Management Zone Delineation and Site-Specific Applications

Fuzzy clustering analysis partitioned the field into four distinct management zones with strong cluster separation (FPI = 0.287, NCE = 0.446), providing quantitative guidance for variable-rate herbicide applications. The identification of 1.09 ha (31.9% of total field area) requiring critical priority management represents substantial optimization compared to uniform treatment approaches. High fuzzy membership coefficients (0.68-0.87) across all management zones indicate robust cluster boundaries suitable for operational implementation.

Zone 2, encompassing the largest critical management area (1.00 ha), exhibited dense AMBEL populations (98.3-130.7 plants m−2) requiring immediate intervention to prevent crop yield losses and seed bank replenishment. The spatial concentration of high-density infestations in discrete units facilitates targeted application strategies and enables economic optimization of herbicide inputs. Management zones in the central and northern field sections corresponded to areas with elevated soil electrical conductivity and vegetation vigor, suggesting these locations represent persistent hotspots requiring intensive management across multiple growing seasons.

The integration of competition ratio analysis with management zone delineation provides additional decision support for resource allocation. Areas with weed-to-crop ratios exceeding 3.0 were identified as priority intervention zones, representing locations where crop yield losses are most probable without intensive management. This approach enables economic threshold-based decision-making, ensuring management intensity is proportional to the potential yield impacts [

71].

The demonstrated precision enables optimisation of herbicide allocation with potential for 35-50% reduction in total herbicide use while maintaining effective weed control in critical areas. This optimisation aligns with sustainable intensification principles and addresses growing concerns regarding herbicide resistance development and environmental impacts [

72].

4.4. Multi-Scale Implementation Framework and Scalability

The demonstrated framework exhibits potential for scalability beyond single-field applications through integration of satellite-derived vegetation indices with high-resolution drone-based detection. Early-season NDVI patterns demonstrated predictive value for late-season weed pressure, enabling adaptive management strategies based on crop vigor assessment without requiring intensive drone surveys across entire farming operations. This multi-scale approach leverages complementary strengths of different remote sensing platforms to provide comprehensive information for precision agriculture applications [

73].

The methodological framework’s reliance on cost-effective drone platforms (DJI Mavic Mini 3) and open-source software components (YOLOv11, SAHI) reduces implementation barriers compared to proprietary precision agriculture solutions. The demonstrated accuracy at 5 m × 5 m resolution provides sufficient precision for variable-rate herbicide applications while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for field operations. This resolution strikes a balance between spatial detail and practical management constraints imposed by current variable-rate application equipment.

The species-agnostic nature of the detection framework enables adaptation to diverse crop-weed systems through transfer learning approaches. The performance achieved across morphologically distinct species (AMBEL, Polygonum spp., Lens culinaris) suggests that underlying feature extraction capabilities can be adapted to alternative crop systems through targeted retraining [80]. This transferability is essential for widespread implementation across diverse agricultural production systems.

Integration with geostatistical analysis provides standardised methodological protocols compatible with existing precision agriculture infrastructure. The demonstrated compatibility with conventional soil sampling and variable-rate application equipment ensures seamless integration into current farm management systems, eliminating the need for substantial additional capital investment.

4.5. Environmental and Economic Implications

The spatial precision achieved in weed detection and management zone delineation enables optimization of herbicide inputs with implications for both economic and environmental sustainability. The identification of 51.7% of the field area as suitable for maintenance-level management represents potential for input cost reduction while maintaining effective weed control. The spatial stratification enables concentration of herbicide applications in high-density weed patches while minimizing treatment in low-risk areas, reducing selection pressure for herbicide resistance development.

The framework’s capacity to detect early-stage weed infestations enables preventive management approaches that reduce reliance on intensive post-emergence treatments. Early intervention strategies based on spatial risk mapping can prevent establishment of persistent weed populations, reducing long-term management costs. This proactive approach aligns with integrated pest management principles and addresses regulatory pressure for reduced agricultural chemical inputs [

74].

Multi-year spatial analysis capabilities enable optimization of crop rotation and tillage strategies based on persistent weed pressure patterns. Areas identified as persistent weed hotspots can be targeted for alternative management approaches, including cover cropping or strategic crop rotation, reducing long-term reliance on chemical control methods [

75].

The demonstrated precision at 5 m × 5 m resolution is compatible with current drone-based herbicide application systems, enabling direct implementation of site-specific treatments. This spatial resolution represents an optimal balance between detection accuracy, computational requirements, and practical application constraints.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations constrain the applicability of the current framework and indicate areas for improvement. The performance degradation observed for smaller weed species (

Polygonum aviculare: F1 = 0.69) indicates that detection accuracy remains challenging for species with minimal morphological distinction during early growth stages. This limitation suggests the need for enhanced feature extraction algorithms or integration of alternative sensor modalities, such as hyperspectral imaging, which can distinguish species based on biochemical differences not visible in RGB imagery [

76].

Spatial interpolation accuracy varied substantially among individual weed species, with some species showing weak spatial dependence (POLAV: nugget/sill = 0.92) that limits the reliability of interpolated surfaces. This variability likely reflects differences in dispersal mechanisms and establishment patterns among species, suggesting the need for species-specific geostatistical models that account for biological differences in spatial behavior.

The framework’s reliance on favourable weather conditions for drone operations constrains applicability during critical management windows. Integration with satellite imagery and ground-based sensors could provide alternative data sources during periods when drone operations are not feasible, ensuring continuity of monitoring capabilities throughout the growing season [

77].

The computational requirements for processing high-resolution imagery through the SAHI framework pose constraints for real-time field applications. Development of edge computing solutions and optimized algorithms will be essential for enabling immediate decision-making in field environments without requiring data transfer to centralized processing facilities.

Future research should focus on temporal analysis capabilities through sequential drone surveys to quantify population dynamics and treatment efficacy assessment. Integration of weather data and microclimate modelling with spatial weed distribution analysis represents an important frontier for predictive modelling. The observed associations between soil moisture patterns and weed establishment suggest that microclimate variables significantly influence germination success, warranting integration of environmental monitoring with spatial analysis [

78].

4.7. Practical Implementation Considerations

The demonstrated framework provides immediate practical value for agricultural producers while establishing methodological foundations for technological development. The framework’s emphasis on cost-effectiveness, scalability, and integration with existing agricultural systems positions it as a viable approach for implementation in sustainable agricultural production systems. The species-specific detection capabilities, spatial pattern analysis, and management zone optimization provide actionable guidance for precision weed management while maintaining compatibility with current farm management practices.

The integration of AI-based detection with geostatistical analysis enables transition from descriptive spatial mapping toward predictive ecological modeling, supporting evidence-based decision making in weed management. The demonstrated accuracy and spatial resolution provide sufficient detail for variable-rate applications while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for operational implementation.

This study demonstrates that integrating advanced AI-based object detection with geostatistical analysis yields a comprehensive framework for precision weed management, addressing current limitations in both detection accuracy and spatial analysis capabilities. The demonstrated methodological advances provide the foundation for the continued development of precision agriculture technologies that support the sustainable intensification of agricultural production systems.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a multi-scale precision agriculture framework that enables a transition from extensive area reconnaissance to ultra-precise field-level weed management through the integration of satellite imagery, AI-based detection, and geostatistical analysis.

The demonstrated approach establishes that satellite-derived NDVI imagery can effectively guide field sampling strategies by identifying areas of botanical interest across extensive agricultural landscapes, extending beyond single-field applications to regional-scale assessment. This reconnaissance capability enables cost-effective prioritisation of detailed field surveys, focusing intensive monitoring efforts on areas with the highest potential for weed pressure.

At the field level, the YOLOv11-SAHI framework achieved high-accuracy species-specific detection (F1-scores: 0.87 for lentil, 0.84 for Ambrosia artemisiifolia) using cost-effective drone platforms, enabling precise botanical characterization at seedling stages within dense grid sampling. The successful processing of high-resolution imagery through slice-based inference methodology addresses critical limitations in small object detection, providing reliable species discrimination with 95% accuracy for crops and 88% for the dominant weed species.

Weed distribution patterns demonstrated significant associations with environmental variables, particularly soil electrical conductivity (AMBEL-CE_75: spatial r = 0.633) and vegetation vigor indices (AMBEL-NDVI_14S: spatial r = 0.818). Areas with CE_75CM > 16 mS m−1 exhibited 67% higher Ambrosia artemisiifolia density, establishing predictive relationships between soil characteristics and botanical distribution patterns that enable proactive management strategies.

The integration of botanical detection with geostatistical analysis successfully translated point-based observations into continuous spatial representations through kriging interpolation (R² = 0.782-0.996), enabling comprehensive mapping of weed pressure patterns. Spatial autocorrelation analysis revealed non-random clustering (Moran’s I = 0.667, p < 0.001), providing evidence for spatially explicit management approaches based on underlying environmental gradients.

Site-specific management zone delineation through fuzzy clustering identified four distinct zones with 31.9% of the field requiring critical intervention, enabling targeted herbicide applications with potential 35-50% reduction in total chemical inputs. The achieved 5 m × 5 m spatial resolution provides sufficient precision for variable-rate applications, demonstrating compatibility with current drone-based herbicide application systems while maintaining cost-effectiveness through open-source software implementation.

The demonstrated framework establishes a scalable pathway from satellite-guided field selection through high-accuracy botanical mapping to precision treatment implementation. This multi-scale approach addresses critical gaps in current precision agriculture technologies by combining extensive area coverage capabilities with ultra-precise field-level interventions, enabling evidence-based weed management strategies that support sustainable intensification of agricultural production systems.

Key methodological contributions include: (1) satellite-to-drone integration for multi-scale assessment; (2) cost-effective AI-based botanical characterisation at seedling stages; (3) quantitative environmental-botanical association analysis; (4) spatial translation of detection outputs to management-ready formats; and (5) demonstration of precision treatment capabilities at operationally relevant scales.

This integrated approach provides immediate practical value for agricultural producers, managers, and service companies, while laying the foundations for the implementation of landscape-scale precision agriculture. It enables a transition from uniform management practices to spatially explicit strategies based on botanical distribution patterns and environmental associations.

Figure 1.

Representative seedlings at the time of UAV survey. Top: Lens culinaris (left), A. artemisiifolia (right). Bottom: P. persicaria (left), P. aviculare (right). All at BBCH 10–14.

Figure 1.

Representative seedlings at the time of UAV survey. Top: Lens culinaris (left), A. artemisiifolia (right). Bottom: P. persicaria (left), P. aviculare (right). All at BBCH 10–14.

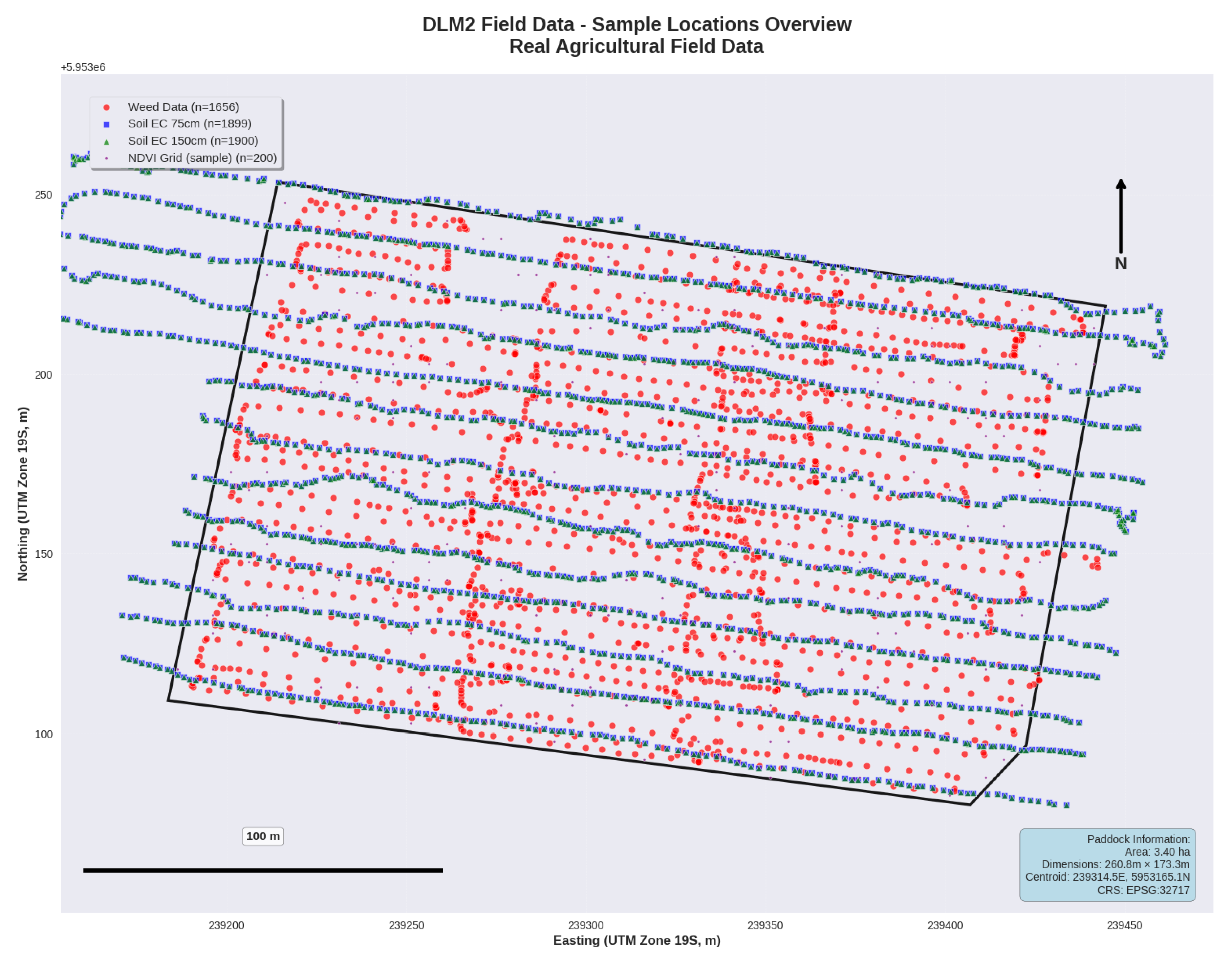

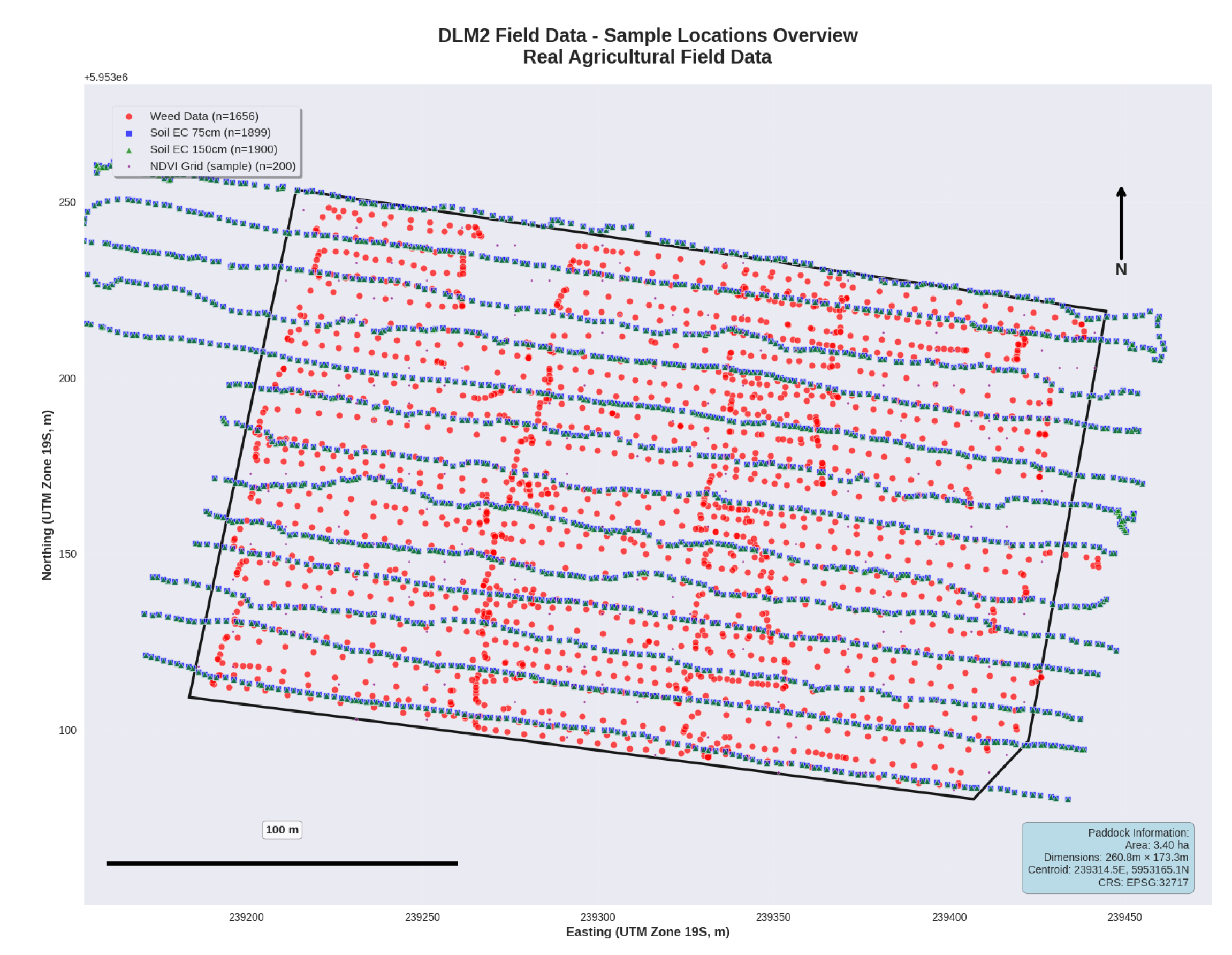

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of sampling points for integrated data collection across the 3.40-hectare lentil field, including outside points measurements from drone imagery analysis (n=1,651), soil electrical conductivity measurements (blue points) at 75 cm and 150 cm depths using EM38-MK2 sensor (n=1,899 each), and NDVI grid samples from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery (n=200). The dark boundary line delineates the field perimeter used for spatial analysis and management zone delineation.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of sampling points for integrated data collection across the 3.40-hectare lentil field, including outside points measurements from drone imagery analysis (n=1,651), soil electrical conductivity measurements (blue points) at 75 cm and 150 cm depths using EM38-MK2 sensor (n=1,899 each), and NDVI grid samples from Sentinel-2 satellite imagery (n=200). The dark boundary line delineates the field perimeter used for spatial analysis and management zone delineation.

Figure 3.

Unified 5 by 5 m grid obtained from interpolated variables.

Figure 3.

Unified 5 by 5 m grid obtained from interpolated variables.

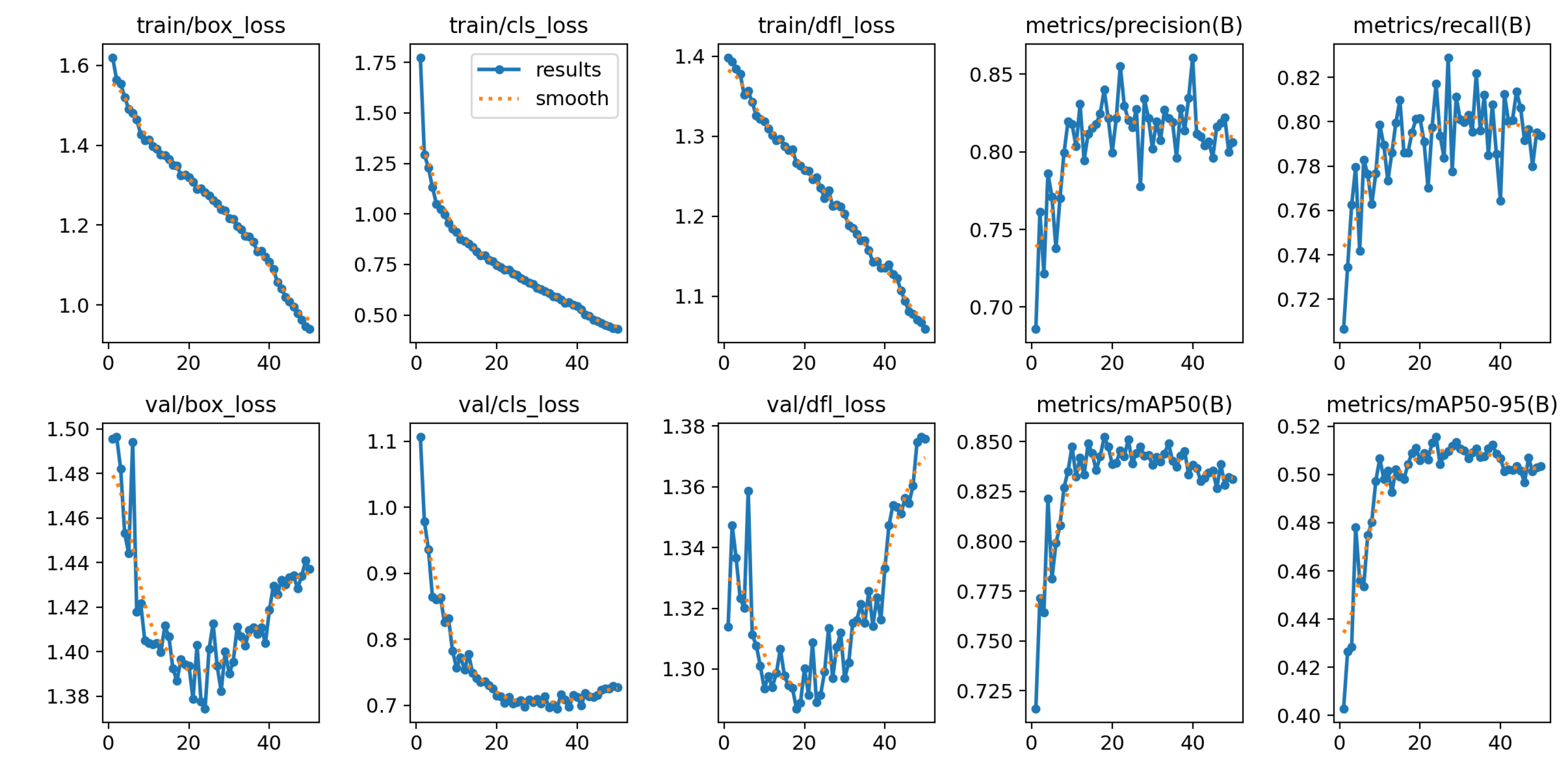

Figure 4.

YOLOv11 training performance across 50 epochs showing loss functions and evaluation metrics. Top row: training losses for bounding box regression (box_loss), classification (cls_loss), and distribution focal loss (dfl_loss), with corresponding validation losses below each. Bottom row: performance metrics including precision, recall, mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP50), and mAP at IoU thresholds 0.5:0.95 (mAP50-95). Blue lines represent actual values, while orange dotted lines indicate smoothed trends. The model achieved convergence by epoch 25 with stable performance metrics suitable for agricultural deployment.

Figure 4.

YOLOv11 training performance across 50 epochs showing loss functions and evaluation metrics. Top row: training losses for bounding box regression (box_loss), classification (cls_loss), and distribution focal loss (dfl_loss), with corresponding validation losses below each. Bottom row: performance metrics including precision, recall, mean Average Precision at IoU threshold 0.5 (mAP50), and mAP at IoU thresholds 0.5:0.95 (mAP50-95). Blue lines represent actual values, while orange dotted lines indicate smoothed trends. The model achieved convergence by epoch 25 with stable performance metrics suitable for agricultural deployment.

Figure 5.

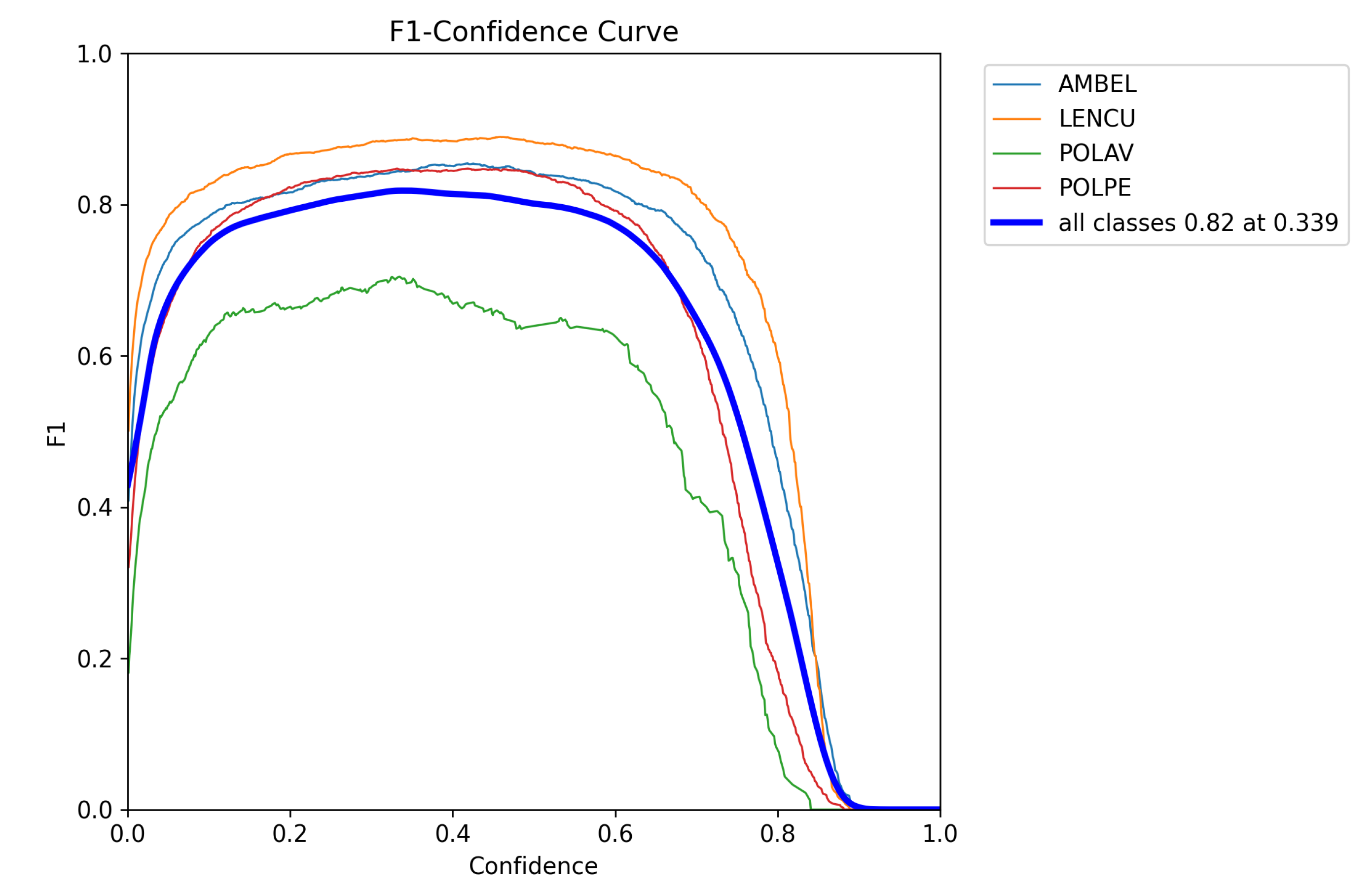

F1-confidence curves for YOLOv11 model performance across target species. Individual curves show species-specific detection performance: LENCU (Lens culinaris, orange), AMBEL (Ambrosia artemisiifolia, blue), POLPE (Polygonum persicaria, red), and POLAV (P. aviculare, green). The thick blue line represents overall model performance across all classes, achieving an optimal F1-score of 0.82 at a confidence threshold of 0.339. Peak performance varies by species, with LENCU showing the highest discrimination capability (F1 = 0.87) and POLAV exhibiting reduced detection efficiency (F1 = 0.69), reflecting morphological and size differences among target classes.

Figure 5.

F1-confidence curves for YOLOv11 model performance across target species. Individual curves show species-specific detection performance: LENCU (Lens culinaris, orange), AMBEL (Ambrosia artemisiifolia, blue), POLPE (Polygonum persicaria, red), and POLAV (P. aviculare, green). The thick blue line represents overall model performance across all classes, achieving an optimal F1-score of 0.82 at a confidence threshold of 0.339. Peak performance varies by species, with LENCU showing the highest discrimination capability (F1 = 0.87) and POLAV exhibiting reduced detection efficiency (F1 = 0.69), reflecting morphological and size differences among target classes.

Figure 6.

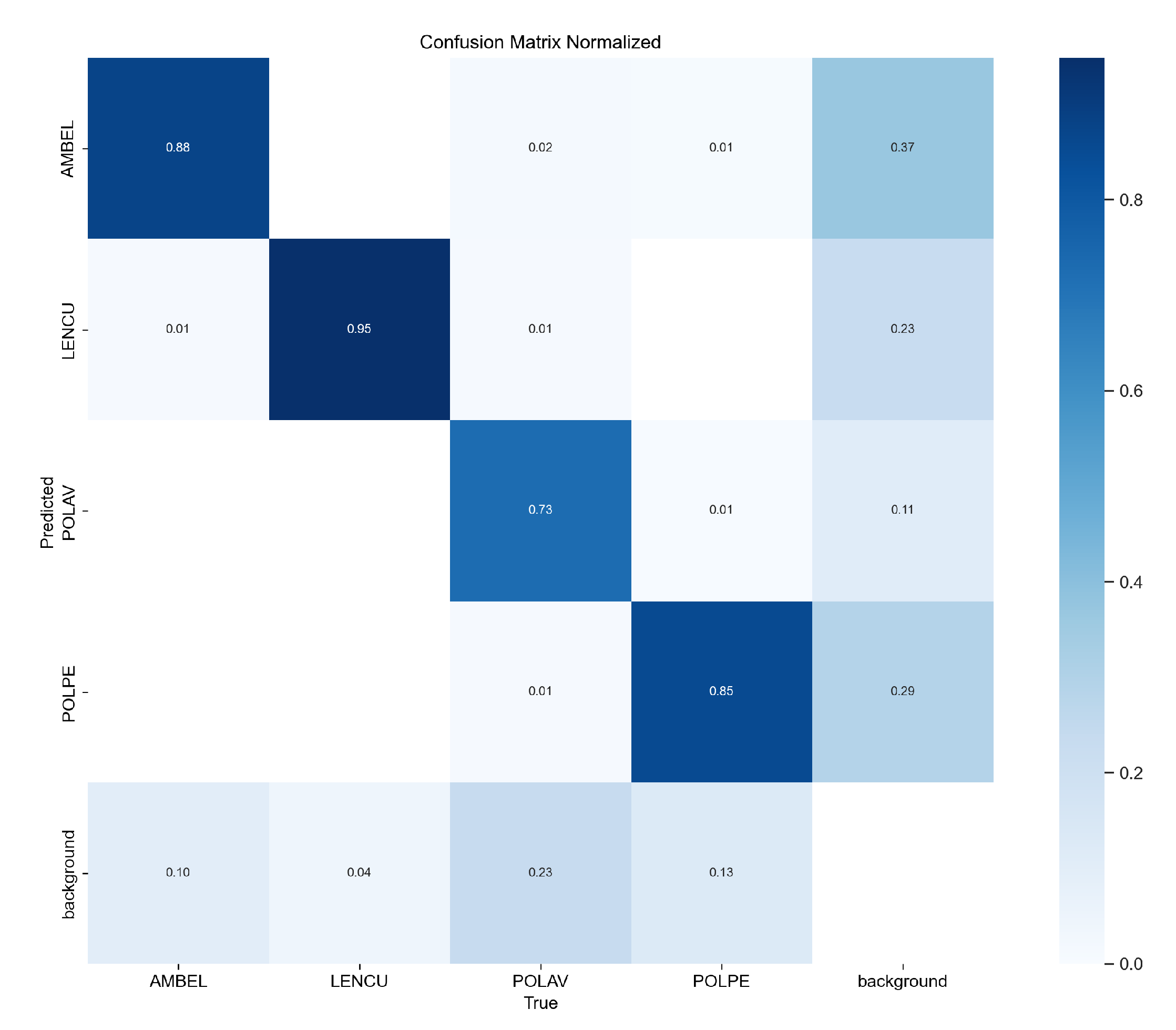

Normalized confusion matrix for YOLOv11 species classification performance. The matrix shows true class labels (vertical axis) versus predicted classes (horizontal axis) with classification accuracies expressed as proportions. Diagonal elements represent correct classifications: LENCU (0.95), AMBEL (0.88), POLPE (0.85), and POLAV (0.73). Off-diagonal elements indicate misclassification patterns, with background confusion being the primary source of classification errors rather than inter-species confusion. Dark blue indicates high accuracy, while light blue represents lower classification rates.

Figure 6.

Normalized confusion matrix for YOLOv11 species classification performance. The matrix shows true class labels (vertical axis) versus predicted classes (horizontal axis) with classification accuracies expressed as proportions. Diagonal elements represent correct classifications: LENCU (0.95), AMBEL (0.88), POLPE (0.85), and POLAV (0.73). Off-diagonal elements indicate misclassification patterns, with background confusion being the primary source of classification errors rather than inter-species confusion. Dark blue indicates high accuracy, while light blue represents lower classification rates.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of drone image capture locations (red points) across the 3.42-hectare lentil field showing the systematic grid sampling pattern used for YOLOv11+SAHI model deployment. The grid-based approach ensured complete field coverage with 1,651 individual image captures, providing a comprehensive spatial representation for subsequent AI-based plant detection and geostatistical analysis integration.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of drone image capture locations (red points) across the 3.42-hectare lentil field showing the systematic grid sampling pattern used for YOLOv11+SAHI model deployment. The grid-based approach ensured complete field coverage with 1,651 individual image captures, providing a comprehensive spatial representation for subsequent AI-based plant detection and geostatistical analysis integration.

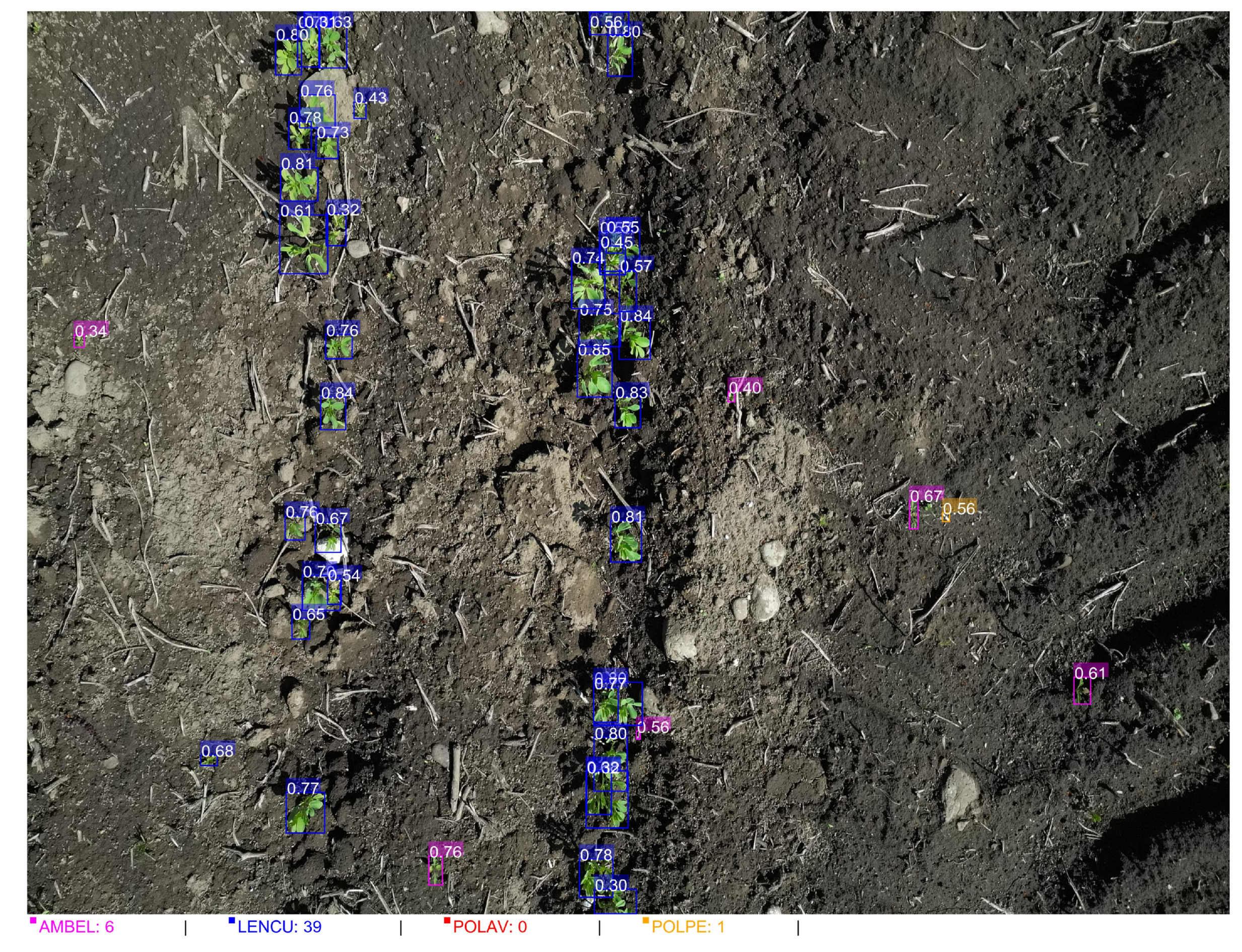

Figure 8.

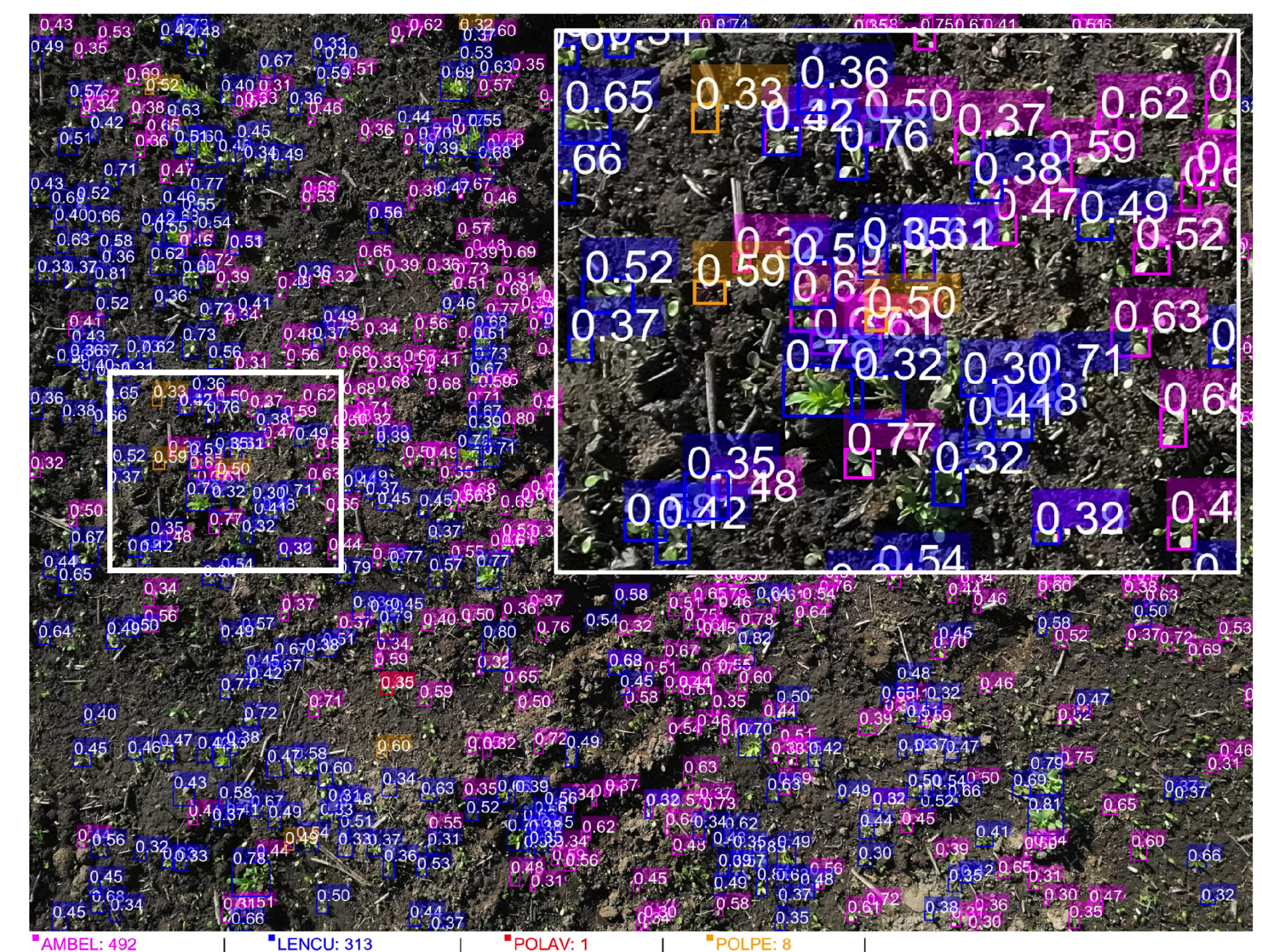

YOLOv11+SAHI inference results showing species-specific detection performance in a representative field section with moderate to high weed density. Individual seedlings are detected with species-specific bounding boxes and confidence scores: magenta = AMBEL (Ambrosia artemisiifolia, 492 detections), blue = LENCU (Lens culinaris, 313 detections), orange = POLAV (P. aviculare, 1 detection), and yellow = POLPE (P. persicaria, 8 detections). Confidence scores (0.30-0.80 range) are displayed above each detection, demonstrating the model’s discriminative capability across varying plant sizes and orientations. The highlighted white rectangular area shows a zoomed region illustrating detection precision at individual seedling level, with successful identification of both crop and weed species in complex field conditions. Total plant count for this image section: 814 individual seedlings detected across four species.

Figure 8.

YOLOv11+SAHI inference results showing species-specific detection performance in a representative field section with moderate to high weed density. Individual seedlings are detected with species-specific bounding boxes and confidence scores: magenta = AMBEL (Ambrosia artemisiifolia, 492 detections), blue = LENCU (Lens culinaris, 313 detections), orange = POLAV (P. aviculare, 1 detection), and yellow = POLPE (P. persicaria, 8 detections). Confidence scores (0.30-0.80 range) are displayed above each detection, demonstrating the model’s discriminative capability across varying plant sizes and orientations. The highlighted white rectangular area shows a zoomed region illustrating detection precision at individual seedling level, with successful identification of both crop and weed species in complex field conditions. Total plant count for this image section: 814 individual seedlings detected across four species.

Figure 9.

YOLOv11+SAHI inference results in a low weed pressure scenario demonstrating accurate species-specific detection and crop-weed discrimination. Individual seedlings are detected with species-specific bounding boxes and confidence scores: blue = LENCU (\textit{Lens culinaris}, 39 detections), magenta = AMBEL (\textit{Ambrosia artemisiifolia}, 6 detections), yellow = POLPE (\textit{P. persicaria}, 1 detection), and orange = POLAV (\textit{P. aviculare}, 0 detections). High confidence scores (0.30-0.84 range) demonstrate reliable detection performance even under sparse plant density conditions. The clear soil background and well-spaced individual seedlings illustrate the framework’s capability to maintain detection accuracy in low-density scenarios typical of effective early-season weed management areas. Total plant count: 46 individual seedlings with a crop-to-weed ratio of 5.6:1, indicating successful crop establishment with minimal weed competition.

Figure 9.

YOLOv11+SAHI inference results in a low weed pressure scenario demonstrating accurate species-specific detection and crop-weed discrimination. Individual seedlings are detected with species-specific bounding boxes and confidence scores: blue = LENCU (\textit{Lens culinaris}, 39 detections), magenta = AMBEL (\textit{Ambrosia artemisiifolia}, 6 detections), yellow = POLPE (\textit{P. persicaria}, 1 detection), and orange = POLAV (\textit{P. aviculare}, 0 detections). High confidence scores (0.30-0.84 range) demonstrate reliable detection performance even under sparse plant density conditions. The clear soil background and well-spaced individual seedlings illustrate the framework’s capability to maintain detection accuracy in low-density scenarios typical of effective early-season weed management areas. Total plant count: 46 individual seedlings with a crop-to-weed ratio of 5.6:1, indicating successful crop establishment with minimal weed competition.

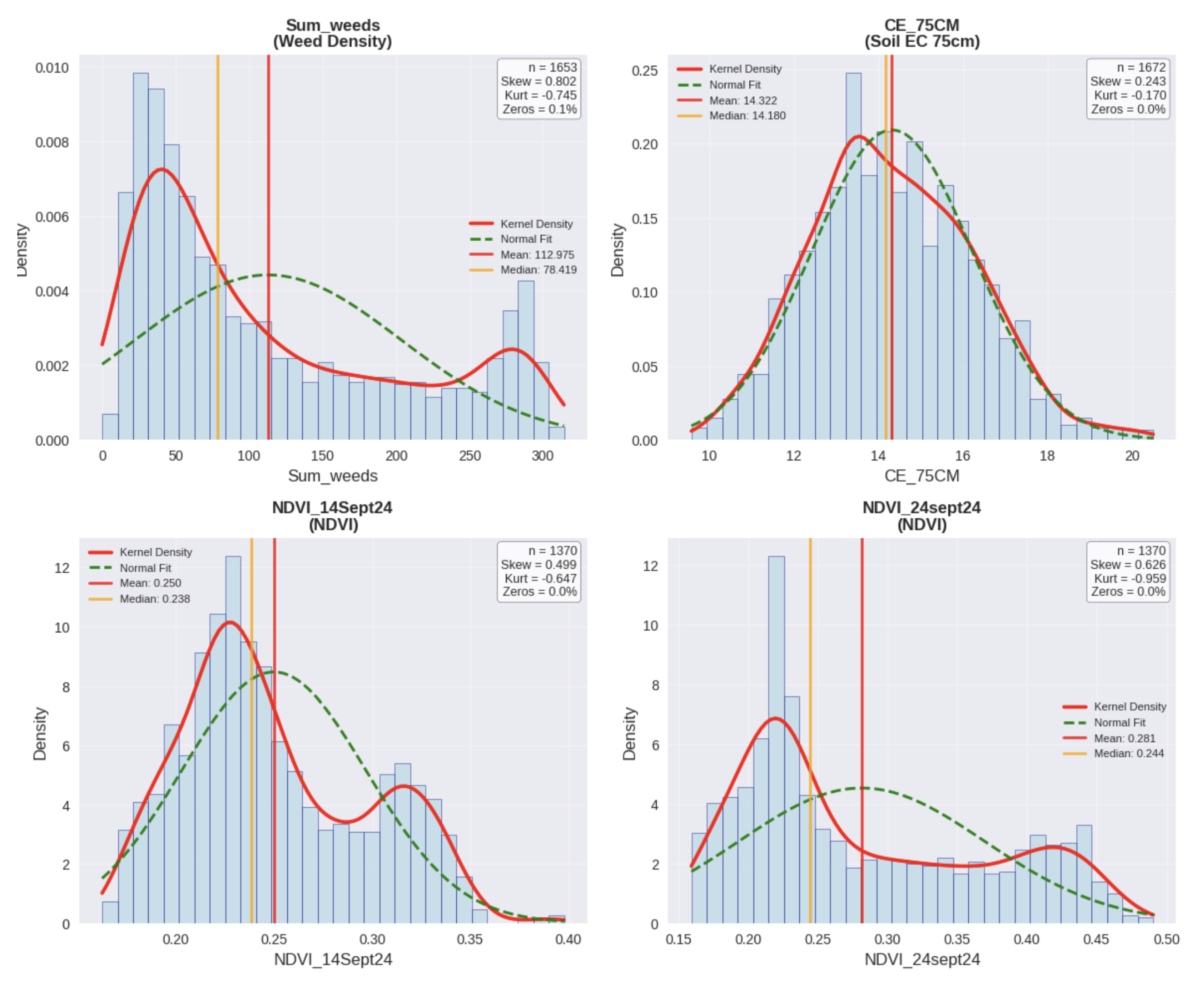

Figure 10.

Distribution plots for representative raw variables to be interpolated.

Figure 10.

Distribution plots for representative raw variables to be interpolated.

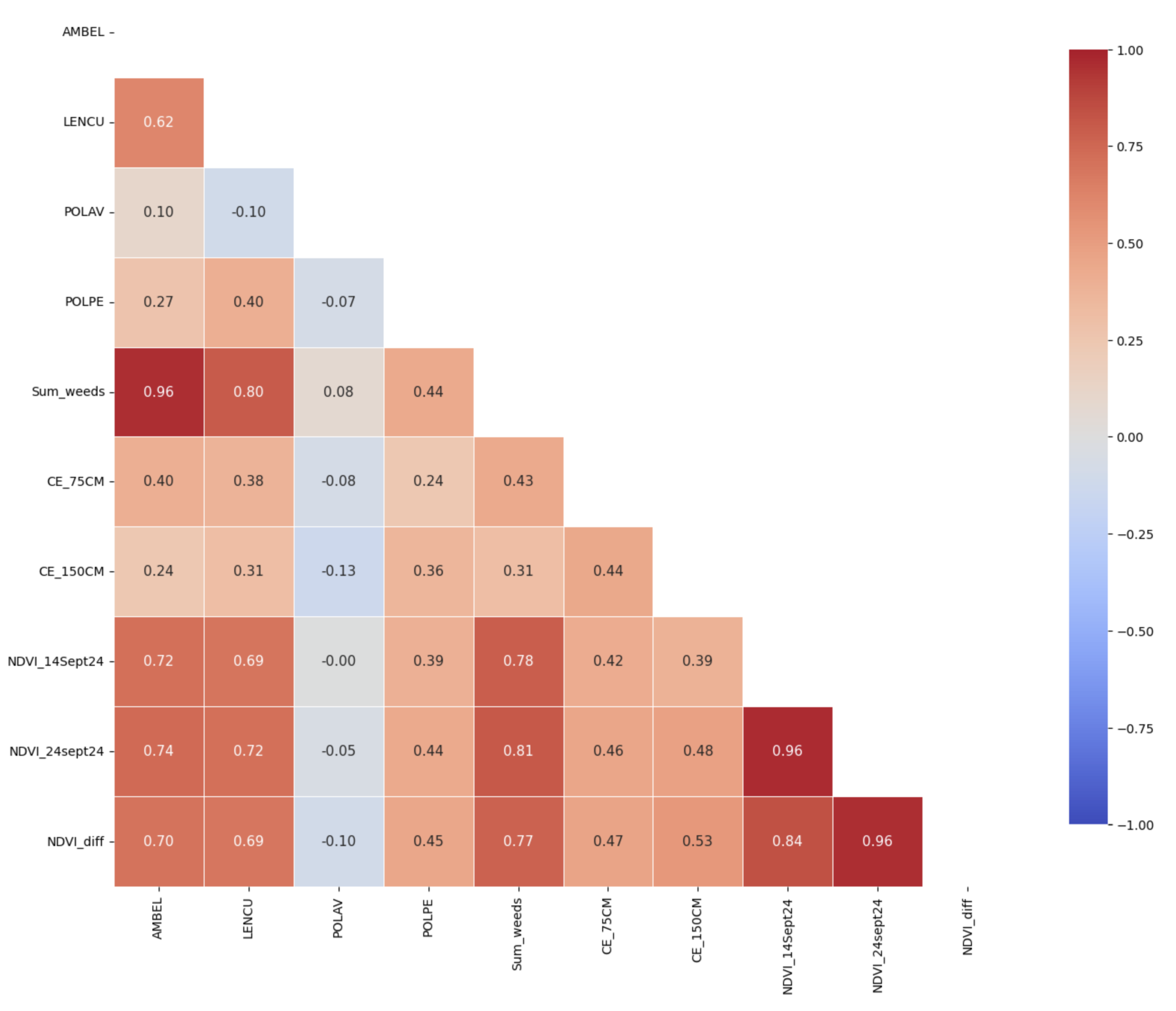

Figure 11.

Correlation matrix for the analyzed variables

Figure 11.

Correlation matrix for the analyzed variables

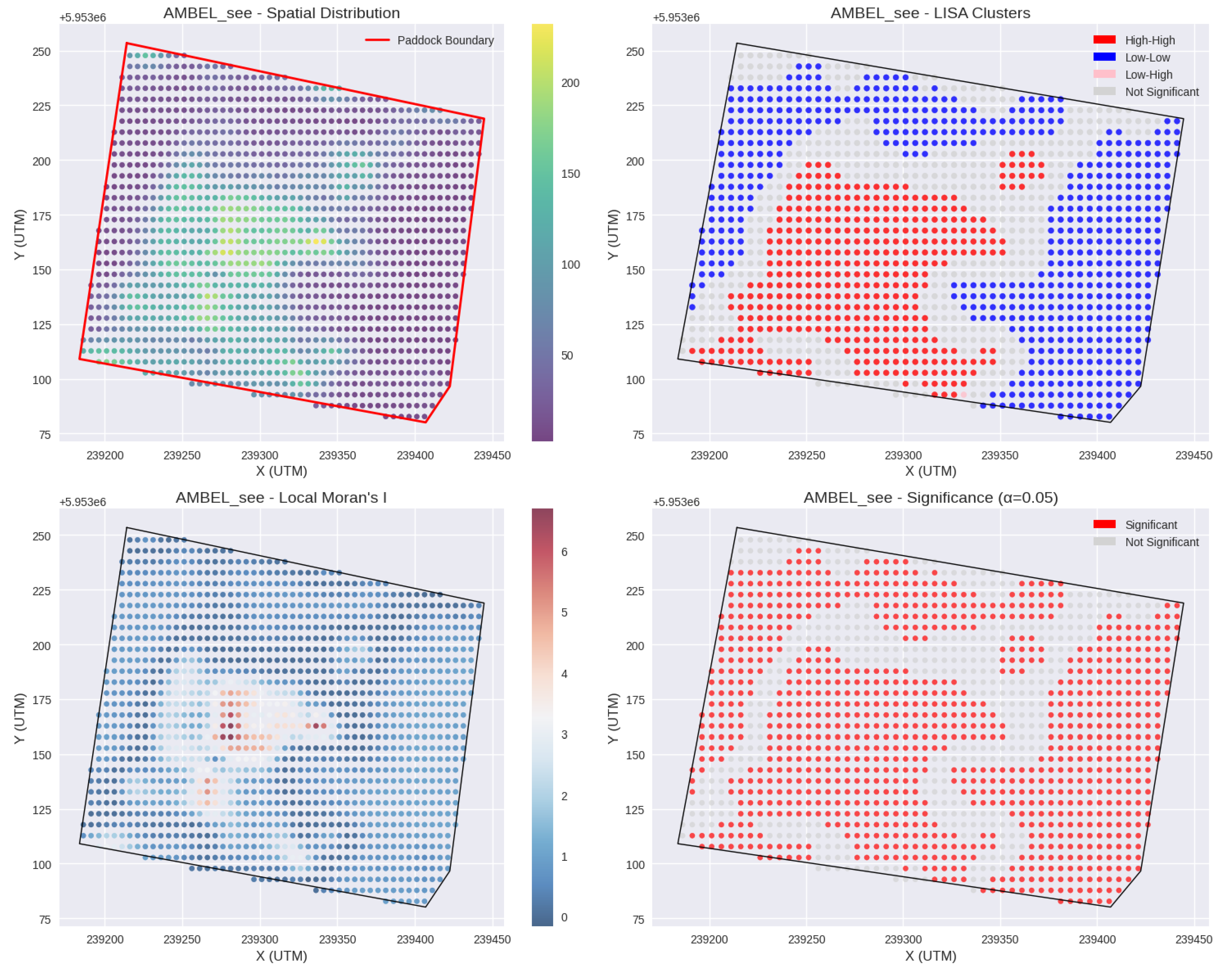

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution maps for Ambrosia artemisiifolia (AMBEL). (a) seedling density (plants per sqm); (b) Local Indicator of Spatial Association (LISA) (c) Moran’s I Index; (d) LISA significance map

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution maps for Ambrosia artemisiifolia (AMBEL). (a) seedling density (plants per sqm); (b) Local Indicator of Spatial Association (LISA) (c) Moran’s I Index; (d) LISA significance map

Figure 13.

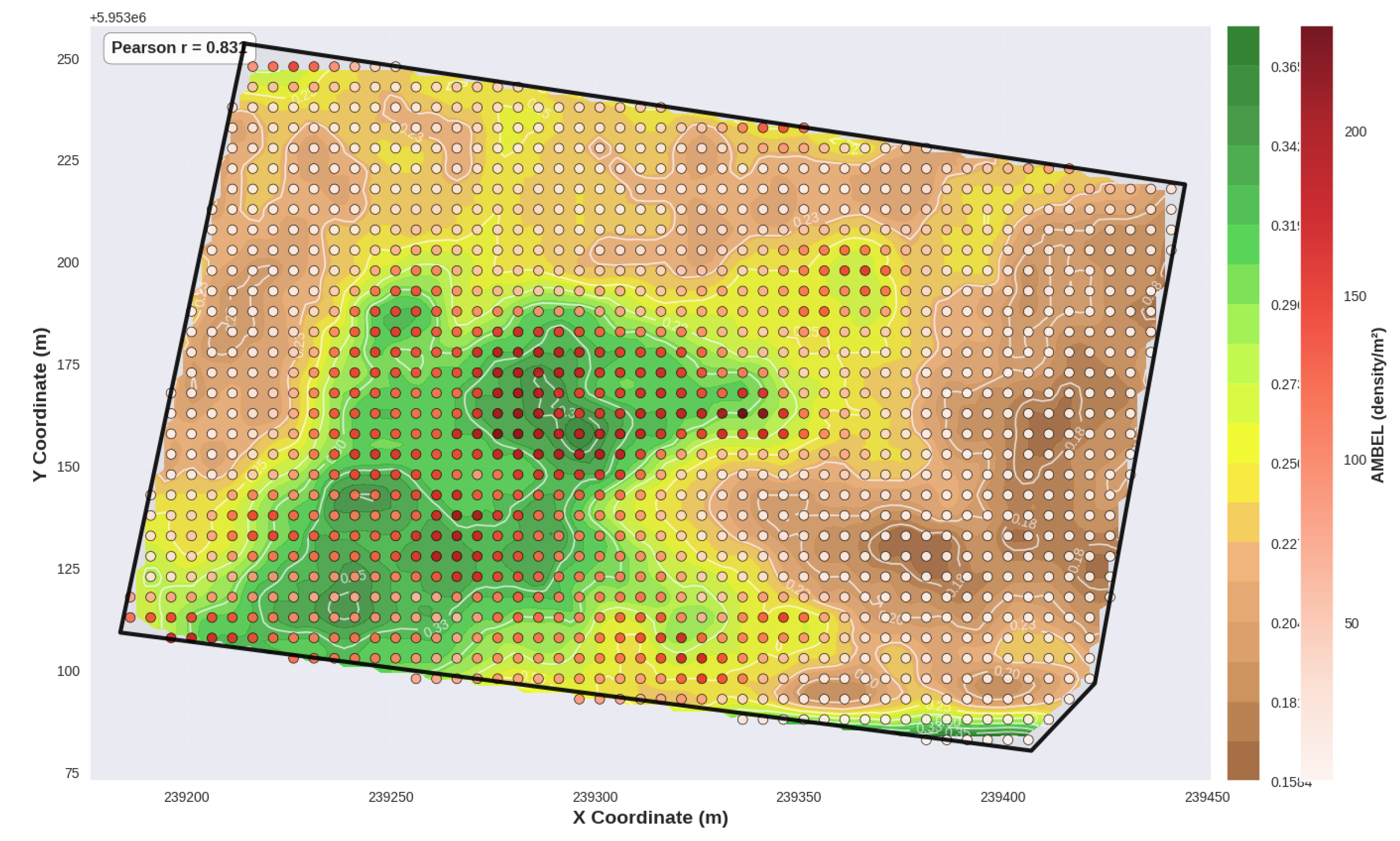

Overlay map for AMBEL vs NDVI_14S, showing a strong positive co-location.

Figure 13.

Overlay map for AMBEL vs NDVI_14S, showing a strong positive co-location.

Figure 14.

Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) map showing co-location patterns between AMBEL density (plants m-2, represented by circles with brown color palette) and NDVI_14S values (background gradient in green to brown tones). The overlay reveals significant positive spatial associations between high weed density areas and vegetation vigor, indicating favorable microsites for Ambrosia artemisiifolia establishment.

Figure 14.

Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) map showing co-location patterns between AMBEL density (plants m-2, represented by circles with brown color palette) and NDVI_14S values (background gradient in green to brown tones). The overlay reveals significant positive spatial associations between high weed density areas and vegetation vigor, indicating favorable microsites for Ambrosia artemisiifolia establishment.

Figure 15.

Bivariate LISA analysis for AMBEL vs CE75, showing a moderate positive co-location

Figure 15.

Bivariate LISA analysis for AMBEL vs CE75, showing a moderate positive co-location

Figure 16.

Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) map showing co-location patterns between AMBEL density (plants m-2, represented by circles with brown color palette) and CE_75CM values (background gradient in yellow to blue tones). The overlay reveals moderate positive spatial associations between Ambrosia artemisiifolia density and shallow soil electrical conductivity, suggesting that areas with higher moisture retention and finer soil texture favor weed establishment.

Figure 16.

Bivariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) map showing co-location patterns between AMBEL density (plants m-2, represented by circles with brown color palette) and CE_75CM values (background gradient in yellow to blue tones). The overlay reveals moderate positive spatial associations between Ambrosia artemisiifolia density and shallow soil electrical conductivity, suggesting that areas with higher moisture retention and finer soil texture favor weed establishment.

Figure 17.