1. Introduction

Intense global efforts have been devoted to the development of hydrocarbon biofuels, which comprise a very interesting alternative for diversifying the world’s energetic matrix and making it more sustainable. Hydrocarbon biofuels have properties and performance similar to those of petrofuels, can utilize existing supply infrastructure (tanks, pipelines, pumps, etc.), can be used without engine modification, and can be blended with conventional fuels in any proportion, therefore complying with the “drop-in” concept. These issues are especially relevant for the production of SAF (sustainable aviation fuel), due to the inherent risks of the aviation sector, although diesel-like hydrocarbon biofuels have also been increasingly produced [1–8].

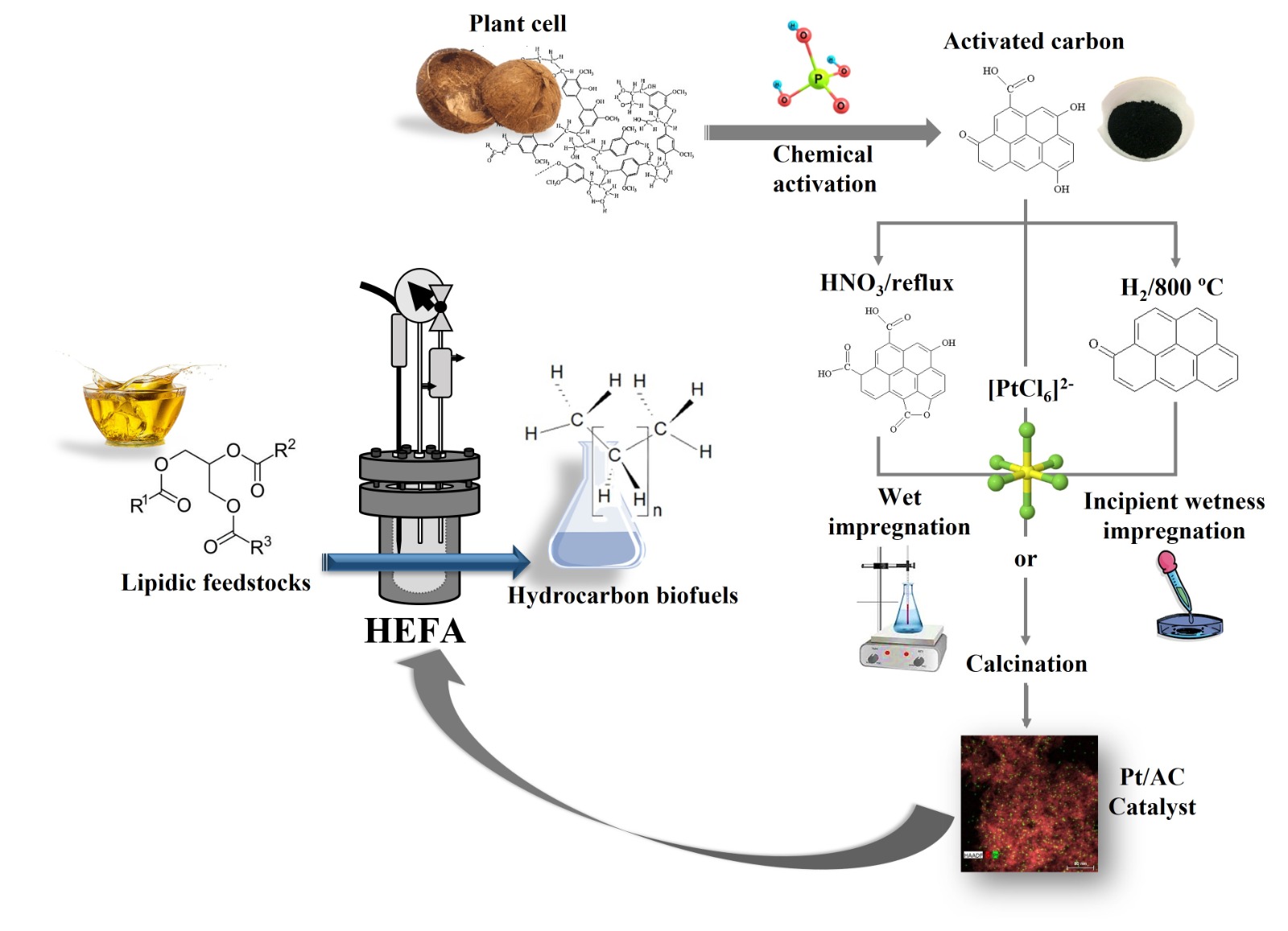

Nowadays, HEFA (hydroprocessing of esters and fatty acids) is the most advanced technology available to produce hydrocarbon biofuels. The key step in HEFA is the deoxygenation of fatty chains resulting from the split of acylglycerides that constitute lipidic feedstocks (vegetable, animal, and algal oils and fats). This is achieved through a process similar to that employed in the hydroprocessing of petroleum and derivatives: thermal treatment at temperatures between around 300 and 400 °C, under elevated H2 pressure (~20–100 bar), in the presence of a heterogeneous catalyst [1–18]. The procedure is thus usually called HDO (hydrodeoxygenation). The possibility of retrofitting petroleum refinery production facilities is a major advantage of HEFA.

HDO of lipidic feedstocks and other O-rich mixtures (e.g., lignocellulose-derived bio-oils) can be carried out in the presence of the same catalysts employed in the hydroprocessing of petroleum and derivatives: sulfides of group 6 transition metals (Mo or W), promoted by a transition metal with a higher number of electrons d (Ni or Co), deposited on porous oxide supports (mainly γ-Al2O3) [9–24]. However, published papers have shown that these catalysts are not ideal for the hydroprocessing of O-rich mixtures. From a support perspective, there is a problem that inorganic materials such as γ-Al2O3 can be hydrolyzed by the abundant water formed during the process, which can provoke catalyst deactivation [25]. In turn, from the point of view of the metal-containing phase, the problem is that the water formed (and possibly other oxygenated molecules such as CO2) causes the replacement of sulfur by oxygen, which gradually reduces the HDO catalyst activity [9–12,26–29]. Some authors have overcome this problem by co-feeding sulfiding agents such as dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) or H2S [9–12,27–30]. In addition, sulfided catalysts can cause the contamination of the produced biofuel by sulfur (leached from the catalyst or present in co-fed sulfiding agents) [11,14,27,28], and this is a real trouble because, contrary to petroleum derivatives, biofuels are naturally nearly sulfur-free.

In the described scenario, the present work aimed to develop sulfur-free heterogeneous catalysts with improved activity and stability in the HDO of lipidic feedstocks. To reach this goal, homemade activated carbon (AC) was used as the support and metallic Pt as the active phase.

The choice for using AC as a support is mainly justified because this material presents high chemical and thermal stability in both acidic and basic media (which includes resistance to hydrolysis) [14,31,32]. Furthermore, ACs: have low acidity, which contributes to reduce hydrocracking and coke formation [31,33,34]; present larger surfaces areas than inorganic supports; have pore size distribution and surface chemistry that can be tailored according to the envisaged application [35–38]; can be obtained from cheap and abundant precursors such as biomass residues, coal and petroleum coke; facilitate the recovery of the metallic phase from spent catalysts by burning the carbon [14,31].

Concerning the metallic phase, Pt (as well as other noble metals) has a well-known ability to activate a wide range of reactions such as hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, hydrogenolysis, and oxygen electroreduction. Pt supported on the surface of acidic porous solids has been employed to promote the hydroisomerization of n-alkanes to iso-alkanes [39–42], which has allowed to improve the cold properties of hydrocarbon fuels, making them more appropriate to the aviation sector [1]. Furthermore, Pt deposited on different inorganic supports (e.g., γ-Al2O3, SiO2, Nb2O5, ZrO2, TiO2, and several zeolites) has been used to promote deoxygenation (in the absence of H2) and HDO, as reported in several reviews [9–18,43,44]. Outstandingly, Chen et al. [46] employed Pt deposited on SAPO-11 zeolite to promote the hydroconversion of Jatropha oil into a hydrocarbon mixture with a high iso-alkane content (that is to say, HDO and hydroisomerization took place in a one-step process).

Nevertheless, there are scarce works devoted to the use of Pt supported on ACs (Pt/ACs) in the HDO of lipidic feedstocks. Among these few works, Jin et al. [47] reported high a conversion of palm oil into alkanes (> 90%) during the hydroprocessing, in a fixed bed reactor (T = 300 °C, 30 bar of H2, and LHSV = 1.5 h‒1), over Pt (1 wt%) supported on the surface of a N-dopped AC. In addition to the excellent performance, the catalyst showed high stability. The authors concluded that the nitrogen incorporated into the carbon favoured the interaction with carbonyls, thus boosting decarboxylation reactions. In turn, Makcharoen et al. [48] investigated the effects of various operating parameters on the hydroprocessing of crude palm kernel oil (CPKO) over an ACsupported Pt catalyst (5 wt% of Pt) in a fixed bed reactor. The best result, with a yield of 58.3% in biojet fuel, was obtained at operating conditions of 420 °C, 34.5 bar, H2 flow 17.5 mL min‒1, CPKO flow 0.02 mL min‒1, and H2-to-oil molar ratio 28.0.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that the high cost of Pt requires optimizing its catalytic activity. However, despite the huge number of studies on the use of Pt/AC catalysts, there are currently no definitive conclusions about the methods and conditions that lead to an optimal catalytic activity, which can be attributed to the complexity of the system and the large number of variables to be taken into account. In general, high catalyst activity is considered to be directly related to a high dispersion of the metallic phase on the surface of a solid with appropriate porosity. The dispersion depends on factors such as the properties of the support (surface area and surface chemistry), the employed impregnation procedure, the nature of the metal precursor, the polarity of the solvent, the pH of the impregnating solution, and the conditions employed in the reduction of the impregnated metal. In turn, appropriate porosity means a pore size distribution that, while providing a high surface area for metal dispersion, ensures the accessibility of reactants and products to and from the catalytic active sites within the pores network.

The described scenario sparked our interest in further investigating the use of Pt/AC catalysts in the HDO of lipidic feedstocks, with a particular focus on finding optimal conditions for obtaining catalysts with improved performance. We investigated the influence of the support surface chemistry (ACs with varying content of acidic functional groups were synthesized and employed), impregnation methodology (incipient wetness impregnation versus wet impregnation), and acidicification of the impregnating solution with HCl.

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of the Unmodified AC P54

An AC sample was synthesized by chemical activation of a dried endocarp of coconut shell with H3PO4, as detailed in Subsection 3.1. A high phosphorus/shell ratio of 0.54 in mass was used to ensure the obtaining of a mesoporous rich material [49] (the obtained AC was thus termed P54). It is worth mentioning that mesopores improve the accessibility of reactants and products to and from the catalytic active sites inside the pores network [26,50,51].

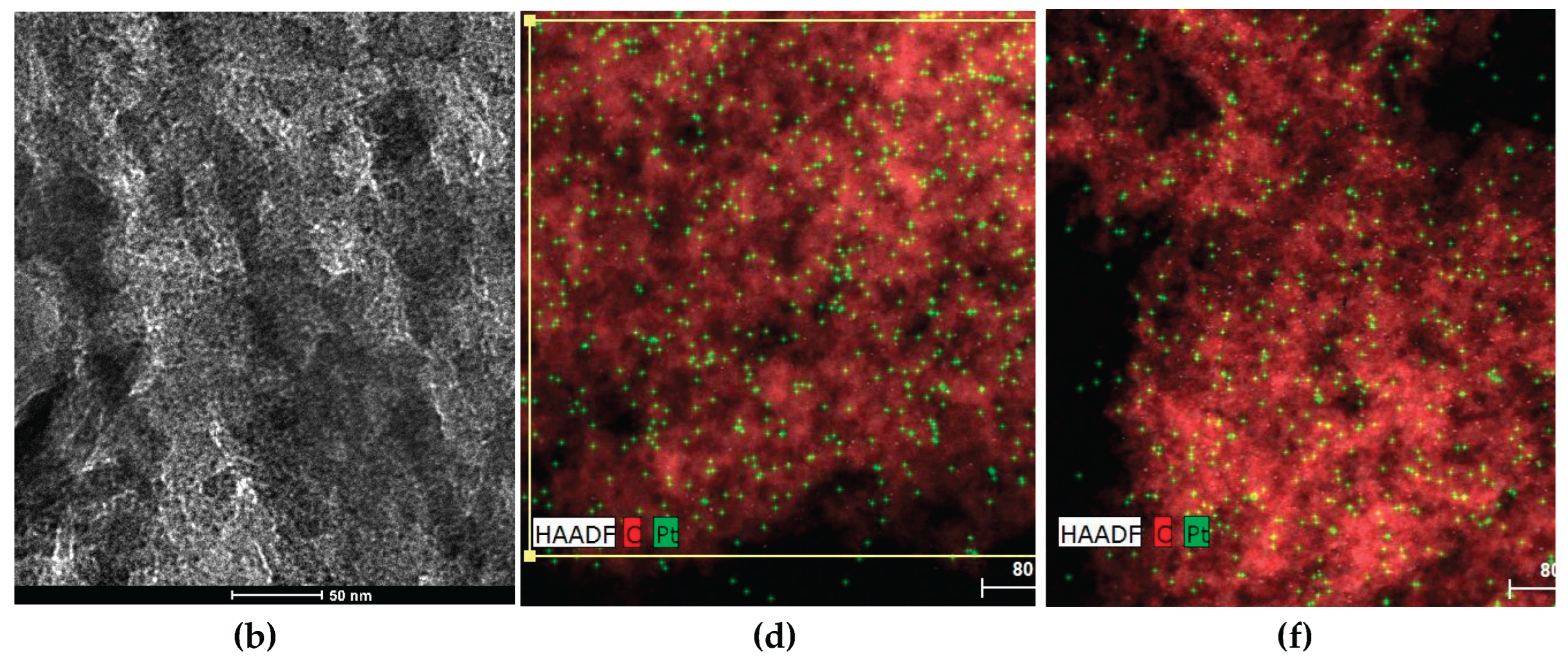

HR-TEM (high-resolution-transmission electron microscopy) micrographs in

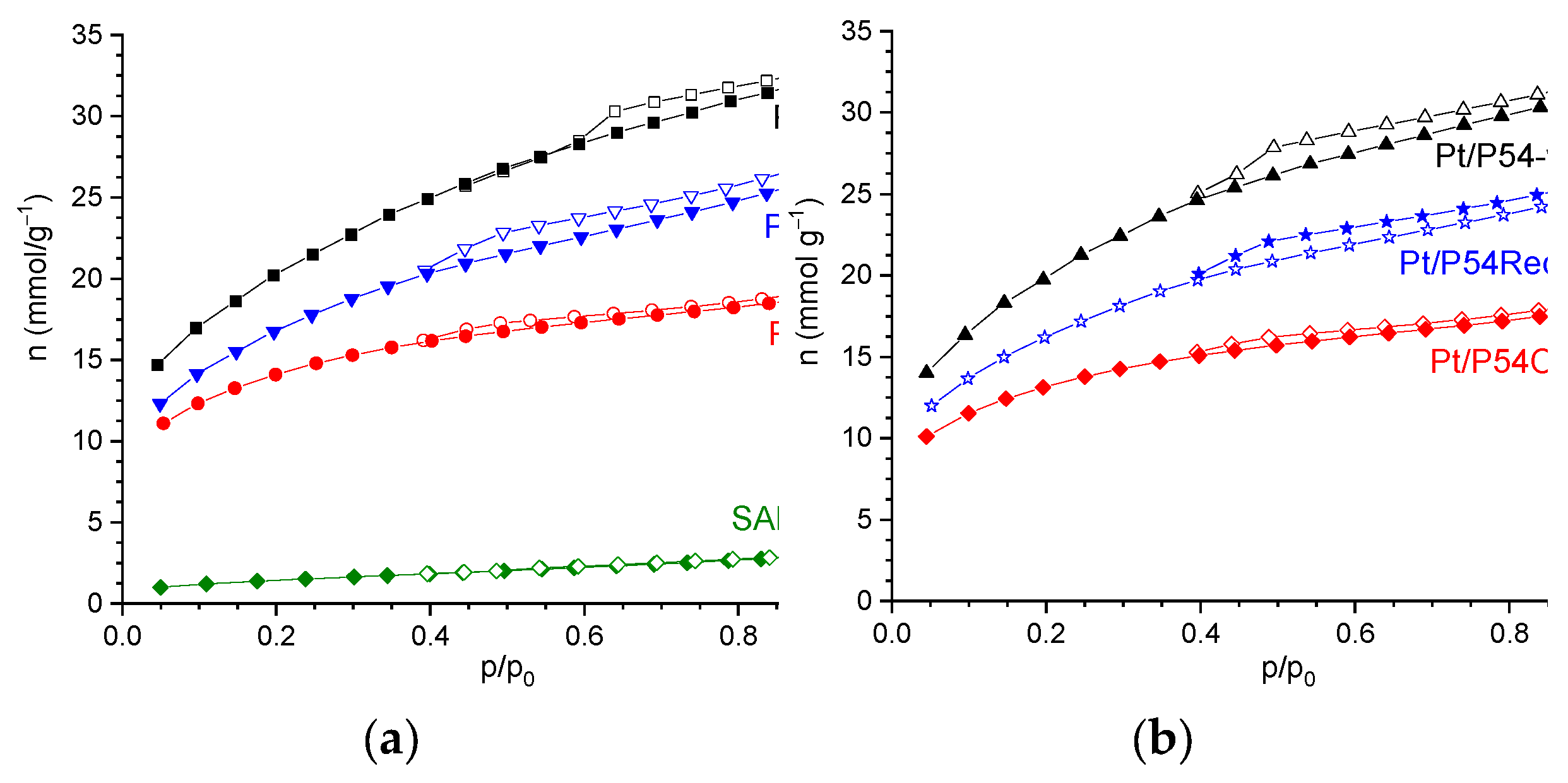

Figure 1a and 1b reveal that the AC P54 has a rough surface and extensive porosity. This porosity was probed through N

2 adsorption-desorption experiments at –196 °C. The isotherm of P54 (

Figure 2a) can be considered a hybrid of types I (b) and IV according to IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) classification [52], which are typical of microporous and mesoporous solids, respectively. These findings are confirmed by the textural data displayed in

Table 1, where the V

mic (volumes of micropores) and V

mes (volume of mesopores) of P54 were 0.72 and 0.55 cm

3 g

–1, respectively, which resulted in a high specific surface area of 1643 m

2 g

–1.

The XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) analysis of P54 revealed the presence of carbon, oxygen, phosphorus, and silicon in proportions of 85.9, 11.9, 1.9, and 0.4 wt%, respectively (

Figure S1a;

Table 2). Phosphorus remained from the activation with H

3PO

4.

The HR-XPS C 1

s core level spectrum of P54 (

Figure S2a) was decomposed into four contributions assigned mainly to unfunctionalized and adventitious carbons (CI peak; 284.8 eV); C–O (CII; 286.2 eV); C=O (CIII; 287.4 eV); COO

- (CIV; 288.8 eV) [53]. In turn, the HR-XPS O 1

s core level spectrum was decomposed into two peaks (

Figure S2d) assigned mainly to O double-bounded (OI; 531.7 eV) and single-bounded to C (OII; 533.4 eV) (see pertinent discussion in reference [36]). The relative contribution of each contribution is reported in

Table 3.

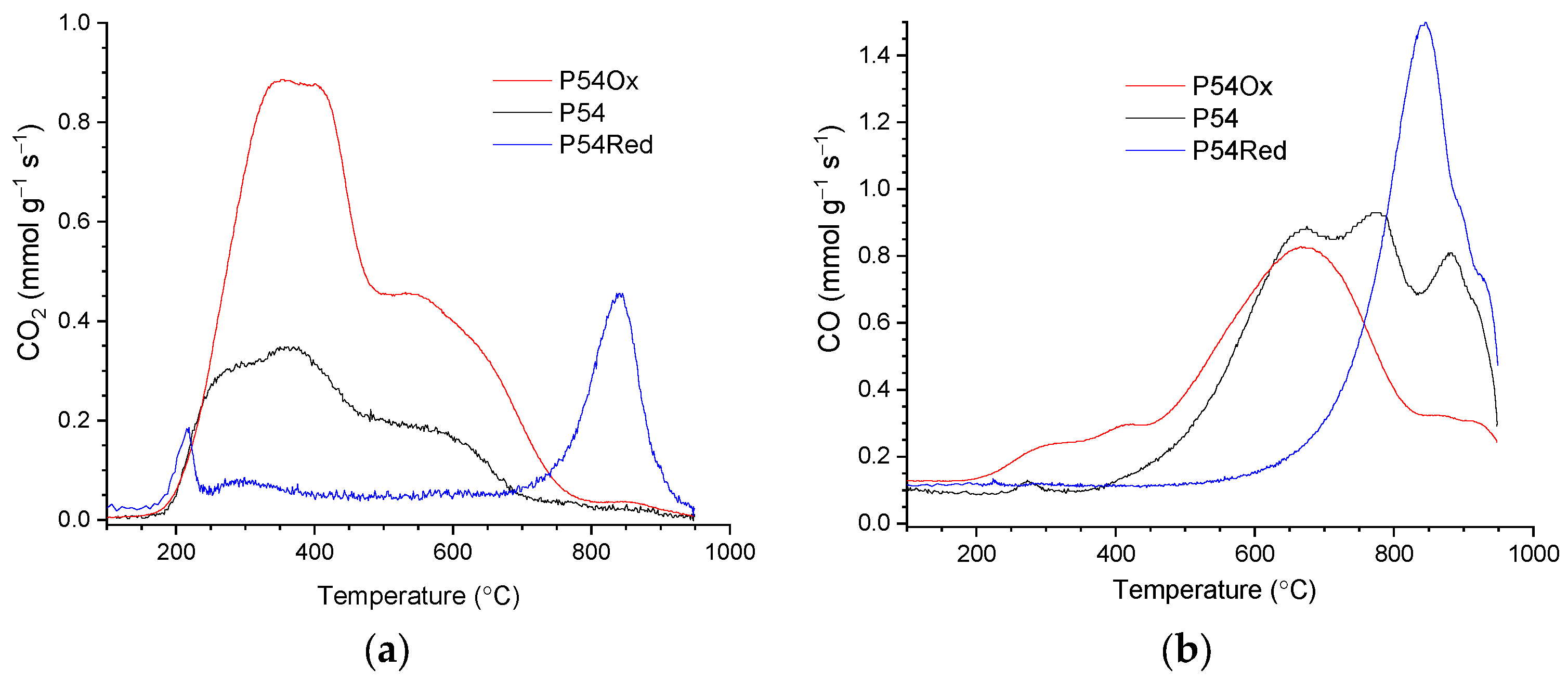

P54 presented intense CO

2 and CO emissions during TPD/MS (temperature-programmed desorption/mass spectrometry) analysis (

Figure 3a and 3b, respectively), which was consistent with its relatively high O content (

Table 2). Deconvolution of the CO

2 and CO-TPD profiles of P54 was presented in previous work (Figure 4 in reference [26]). The CO

2 profile was decomposed into five contributions centered at 260, 363, 500, 606, and 794 °C. The first three contributions were assigned to stronger carboxylic acids, weaker carboxylic acids, and anhydrides, respectively, whereas the other two were attributed to lactones. The CO-TPD profile was also decomposed into five contributions, which were assigned to: anhydrides, which release CO

2 and CO simultaneously (500 °C); phenol/ether (650 and 780 °C); ketones/quinones (886 and 930 °C).

The titration data (

Table 4) revealed that P54 has high contents of strong (0.55 mmol g

−1) and weak (1.21 mmol g

−1) acidic groups, besides a low content of medium acidity groups (0.07 mmol g

−1). These results are consistent with the TPD/MS analysis because, as depicted elsewhere, it has been assumed that strong acids comprise carboxylic acids and anhydrides, whereas weak and medium strength acids correspond mainly to phenols and lactones, respectively. In turn, the content of basic groups was zero.

The chemical composition of the prepared ACs was also probed by elemental analysis (EA). The resulting C, H, and N contents for P54 were 84.2, 1.4, and 0.3 wt%, respectively, with a H/C atomic ratio of 0.20 (

Table 4).

2.2. P54 Modification

The original AC P54 was subjected to two different treatments: (i) thermal treatment up to 800 °C in a H2 atmosphere aiming to remove acidic oxygenated groups; (ii) treatment with HNO3 solution aiming to increase the content of acidic oxygenated groups (Subsection 3.2). The modified ACs (termed P54Red and P54Ox, respectively) and the unmodified AC P54 were subsequently employed as support in the synthesis of the Pt-based catalysts. Therefore, it was possible to investigate the influence of surface chemistry on the properties of the obtained catalysts.

2.2.1. Thermal Treatment Under H2 Atmosphere

In a previous work [36], a commercial AC sample was heated to 800 °C in an inert atmosphere (N2) aiming to remove acidic oxygenated groups. However, a certain amount of these groups was detected even in the treated material. The explanation for this behavior lies in the fact that, after heat treatment in an inert atmosphere, carbon atoms with incomplete valences and unpaired electrons remain, which react with atmospheric oxygen and water vapor to generate new acidic oxygenated groups [54,55]. Therefore, in the present work, in an attempt to stabilize these reactive carbon atoms, P54 was heat-treated in a H2-reducing atmosphere.

The treatment up to 800 °C resulted in considerable weight loss (12.4 wt%) and reductions in porosity (V

mic and V

mes decreased from 0.72 and 0.55 cm

3 g

−1 to 0.60 and 0.32 cm

3 g

−1, respectively;

Table 1) and specific surface area (from 1643 to 1367 m

2 g

–1;

Table 1). The weight loss can be mainly attributed to the release of CO

2 and CO due to the decomposition of oxygenated acidic groups, in a similar way as observed during the TPD analysis of P54 (

Figure 3). Furthermore, the release of H

2O, H

2, and CH

4 has minor contributions, as reported elsewhere [36]. In turn, the reduction in porosity and specific surface area can be related to the aromatization process that takes place during thermal treatment, which promotes material shrinkage and, consequently, pore contraction [36–38]. This aromatization can be confirmed by the observed decrease in the H/C ratio (from 0.20 to 0.08;

Table 4).

Concerning the TPD profiles of the sample obtained after the reductive thermal treatment with H

2 (P54Red), they presented only slight CO

2 and CO emissions until the temperature approached 800 °C (

Figure 3). In turn, relatively intense CO and CO

2 peaks with roughly similar profiles were observed at higher temperatures, with a maximum at around 840 °C. The CO peak is assigned to carbonyl groups, while the less intense CO

2 peak is assumed to be, in fact, mainly the result of a partial oxidation of CO on the AC surface, as previously discussed in reference [36]. In accordance with the TPD profiles, the HR-XPS C 1

s peak of carboxylic groups (CIV peak) disappeared after the treatment, while the intensity of the peak relative to carbonylic groups (CIII) slightly increased (

Figure 2Sb;

Table 3).

Consistent with the TPD analyses, the titration data (

Table 4) showed that the reductive treatment caused a pronounced reduction in the content of acidic groups (from 1.83 to 1.15 mmol g

‒1), as well as some increase in the content of basic groups (from zero to 0.23 mmol g

‒1), which are frequently associated with pyrone-like structures and π-electrons on the basal planes of carbons [36,50]. Due to the pronounced removal of acidic oxygenated groups, the oxygen content decreased from 11.9 to 8.0 wt% (XPS data;

Table 2).

2.2.2. Oxidative Treatment with HNO3

Figure 3a shows that the intensity of all CO

2 emissions pronouncedly increased after the treatment of P54 with HNO

3, which evidences that additional carboxylic acids, anhydrides, and lactones were created on the AC surface. Concerning CO emissions (

Figure 3b), they few changed up to around 700 °C (phenol/ether groups), but strongly decreased at higher temperatures, which can be attributed to the oxidative attack of HNO

3 to carbonyl groups [36]. Consistent with the TPD analyses, the contents of strong (i.e. mainly carboxylic acids plus anhydrides) and medium strength acids (i.e. mainly lactones) increased (from 0.55 to 1.26 and from 0.07 to 0.42 mmol g

−1, respectively;

Table 4), while the content of medium strenght acids (phenols) few changed. Furthermore, there was also an increase in the relative intensity of the peak at around 288.8 eV in the HR-XPS C 1s core level spectrum (CIV peak), which is assigned to carboxylic carbons (

Figure 2Sc;

Table 3). As a consequence of the insertion of acidic oxygenated groups, the O content (determined by XPS) pronouncedly increased (from 11.9 to 32.4 wt%;

Table 2).

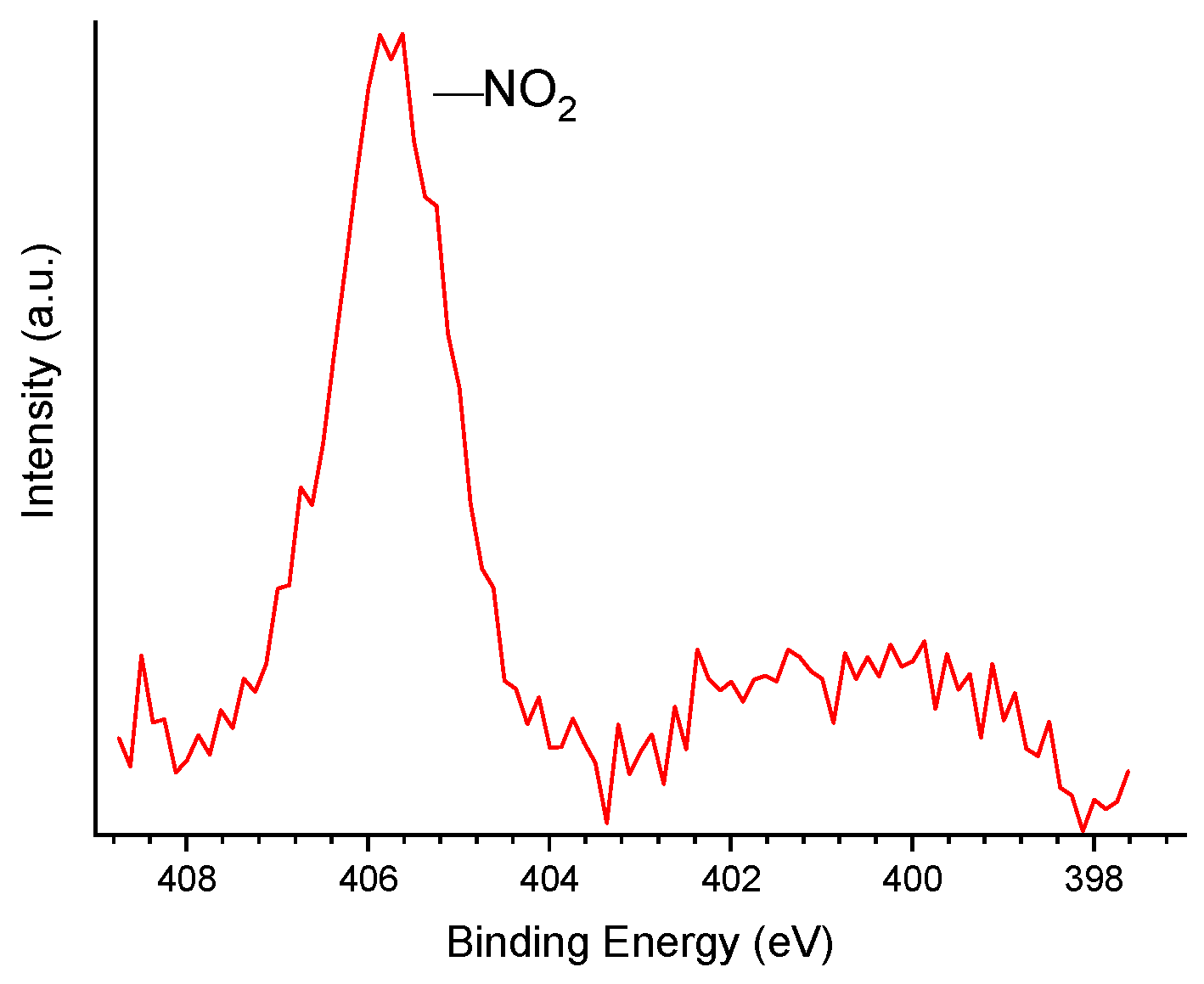

The treatment with HNO

3 also promoted an increase in the N content on the surface, from 0.0/0.3 to 2.4/1.6 wt% (XPS (

Table 2)/EA (

Table 4)). The HR-XPS N 1s core level spectrum (

Figure 4) reveals that N was inserted as nitro groups (‒NO

2), which gave rise to a peak centered at 405.7 eV (see pertinent discussion in reference [36]).

The treatment with HNO

3 reduced the porosity (V

mic and V

mes decreased from 0.72 and 0.55 cm

3 g

−1 to 0.51 and 0.17 cm

3 g

−1, respectively;

Table 1) and specific surface area (from 1643 to 1129 m

2 g

–1;

Table 1). This usual behavior can be attributed to two factors: (i) the formation of acidic oxygenated groups that can block the entrance of narrow pores; (ii) the collapse of pore walls by oxidation [36,56,57].

2.3. Catalysts Preparation and Characterization

Unmodified (P54) and modified (P54Red and P54Ox) ACs were used as supports for the preparation of Pt-based catalysts employing incipient wetness impregnation or wet impregnation, with or without the acidification of the impregnating solution with HCl. The obtained catalysts were labeled as follows: the metal symbol (Pt); the AC employed as support is then indicated after a slash; separated by a hyphen, the letter “w” or “i” indicates if wet or incipient wetting impregnation was used; finally, if the impregnating solution was acidified with HCl, this is indicated by “ac” preceded by a comma. Thus, just as an example, the Pt/P54Red-w,ac catalyst corresponds to the one prepared by the deposition of Pt on the surface of P54Red by wet impregnation with a H2PtCl6 solution acidified with HCl.

The ICP/OES (inductively coupled plasma/optical emission spectrometry) analyses showed that Pt was effectively deposited on the surface of the AC supports (

Table 5), although the Pt proportion depended on the employed AC and the impregnation conditions. The Pt content varied in the range from 0.42 to 1.00 wt%.

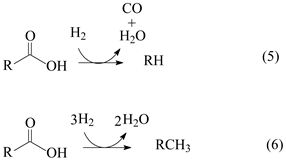

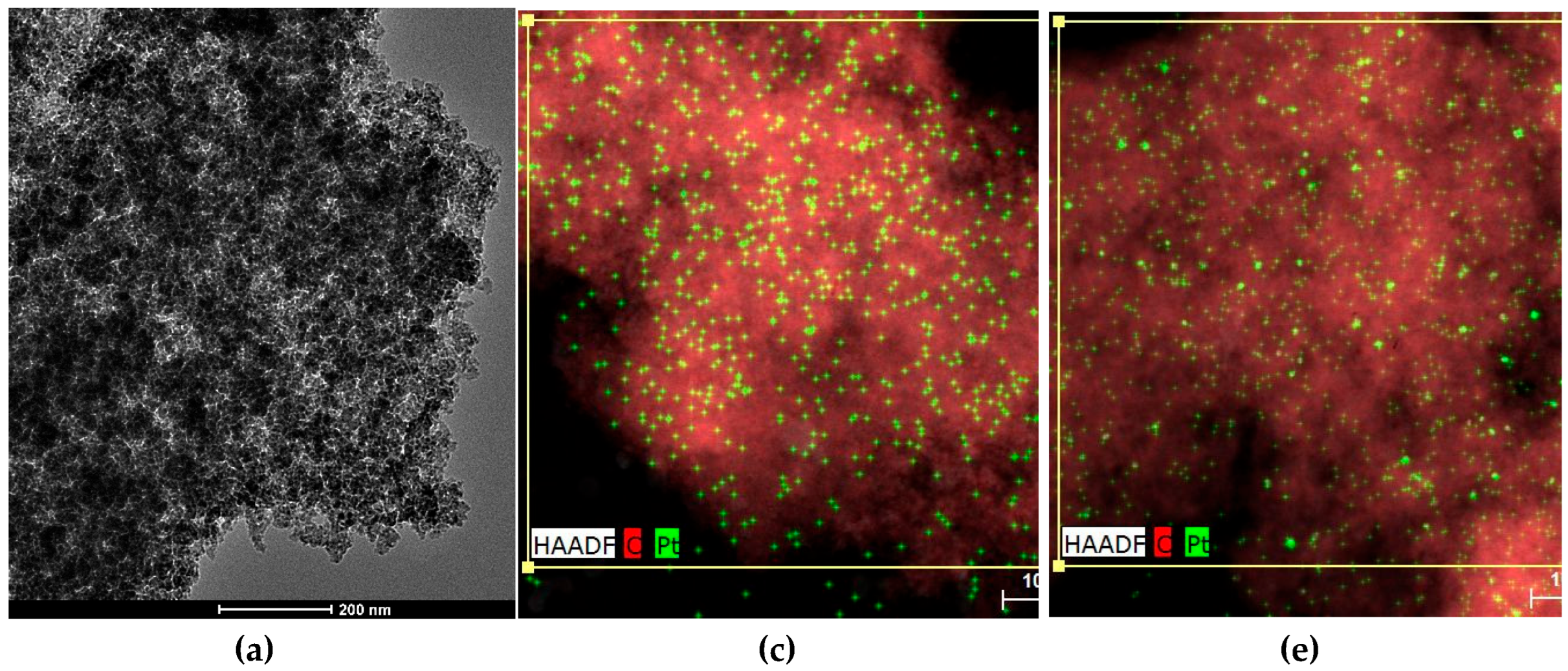

EDX (energy-dispersive X-ray) elemental mapping images show small Pt aggregates with dimensions of a few nanometers uniformly distributed over the support surface, as illustrated for some selected catalysts in Figures 1c–1f. The corresponding average particle sizes (see the corresponding histograms of Pt particle size distribution in

Figure S3) ranged from 2.7 to 6.8 nm (

Table 6).

The comparison of the isotherms of the prepared catalysts (

Figure 2b) with those of the original supports (

Figure 2a), and the data of pore morphology (

Table 1) reveals that Pt deposition did not provoke significant reductions in porosity and specific surface area.

Table 2 reports the XPS elemental composition of some selected catalysts. Remarkably, the surface Pt contents were systematically lower than those determined using ICP/OES. Since XPS probes the few uppermost layers of the external surface, while ICP/OES is a bulk technique, these results suggest that most of the Pt was deposited inside the pores.

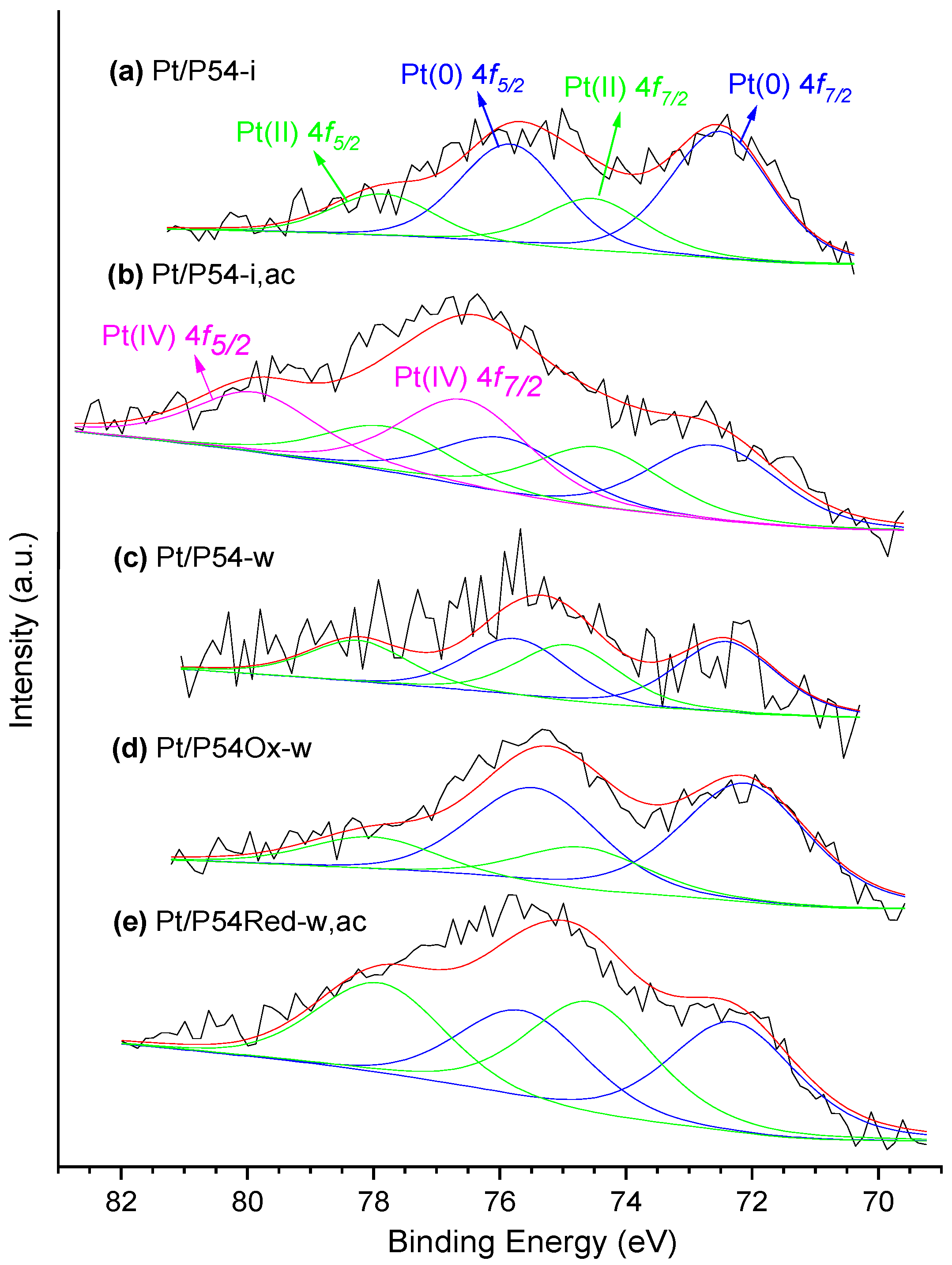

The HR-XPS Pt 4

f core level spectra of the prepared catalysts displayed a shallow envelope in the range of around 70–81 eV (

Figure 5). In a general way, the envelopes were deconvoluted into two doublets Pt 4

f7/2-Pt 4

f5/2 [58,59]: one of them, assigned to Pt(0), with the peaks centered in the range of 72.2–72.6 eV and 75.5–75.9 eV; the other one, assigned to PtO, presented the respective peaks in the range of 74.0–74.7 eV and 77.8–78.3 eV. In the specific case of the Pt/P54-i,ac sample, a third doublet with peaks at 76.6 and 79.9 eV was verified, which was assigned to PtO

2.

At this point, it is worth making a parenthesis to highlight that the ratio of metallic Pt (Pt(0) / (Pt(II) + Pt(IV)) showed a direct correlation with the average Pt particle size (

Table 6). This behavior can be taken as evidence that, as already reported by Singh et al. [58], Pt atoms on the external surface of the particles can be oxidized by air at ambient conditions, so that the smaller the particles, the lower the proportion of metallic Pt.

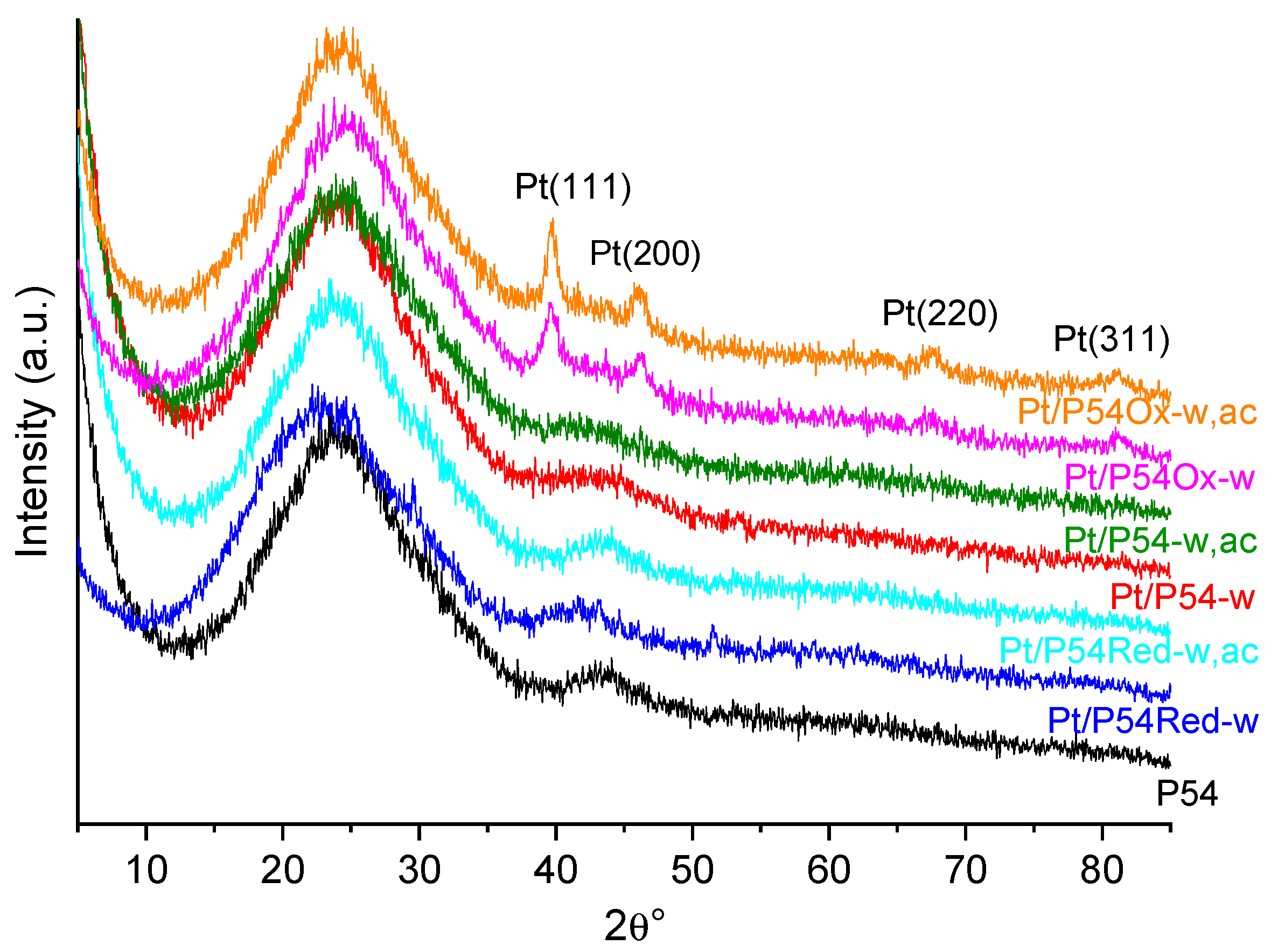

Figure 6 displays the XRD (X-ray diffraction) profiles of some selected catalysts and, for the sake of comparison, of the bare AC P54. Except for Pt/P54Ox-w, the diffractograms of the other catalysts present a similar profile to that of P54, with only two broad peaks due to the (002) and (100) diffraction planes at 2θ approximately 24 and 43°, which are characteristic of amorphous carbon. On the other hand, the diffractogram of Pt/P54Ox-w presents four additional peaks at 36.7, 46.1, 67.5, and 81.1°, which were assigned to the (111), (200), (220), and (311) diffraction planes of Pt(0), respectively [58]. These results were attributed to the presence of larger Pt particles on the surface of the catalysts prepared using the AC pre-treated with HNO

3 (P54Ox) as support. Indeed, the elemental mapping images in

Figure 4 make clear that Pt/P54Ox-w has a lower number of larger Pt particles compared to the other catalysts, and Pt/P54Ox-w presents the largest average particle size reported in

Table 6, 6.8 nm. Remarkably, this value was the only one substantially above the X-ray scattering coherence length of Pt (in the range of around 4.0–4.5 nm, as determined by Schmies et al. [60]), which explain why Pt/P54Ox-w was the only sample to present the peaks corresponding to metallic Pt in

Figure 6.

2.4. Searching for Optimal Conditions for Catalyst Preparation

In a first phase of this work, a comprehensive study was performed to determine the optimal preparation conditions for catalysts intended for the HDO of lipidic feedstocks. Taking into account that the split of the triacylglyceride molecules that constitute lipidic feedstocks results in a complex mixture of fatty acids, this study was carried out using a model compound, lauric acid (Subsection 2.4). This facilitated the characterization of the obtained products and the understanding of the reaction pathways. Subsequently, the catalyst that presented the highest HDO activity in the tests with lauric acid was employed in the hydroprocessing of a real lipidic feedstock, coconut oil (Subsections 2.5 and 2.6). It is worth mentioning that our research group has usually employed coconut oil in this kind of study [21,26] because it is mainly composed of fatty chains that match the carbon chain length range of jet fuels and, as mentioned in the Introduction Section, aviation is the sector for which hydrocarbon biofuels are most interesting. In addition, since most of the coconut oil fatty chains are C12 [61], lauric acid was chosen as the model compound.

The acidic index (AI) of the obtained liquid mixtures was used as the key parameter to evaluate the catalysts activity for lauric acid HDO. It is valid to stress that the lower the AI of the obtained product, the higher the lauric acid conversion and, therefore, the higher the catalyst activity. The AI was also employed to evaluate the catalyst activity in coconut oil HDO, which was possible because the triglycerides molecules are first converted into the respective fatty acids [21].

2.4.1. Blank Tests

Two 8 h blank tests with lauric acid were carried: in the first, no support or catalyst was added to the reaction system; (ii) in the second, only the bare AC P54 was added (Entries 1 and 2 in

Table 7). The obtained products presented AIs of 233.8 and 220.8, respectively, which were only a few lower than the theoretical value calculated for lauric acid (280.0). These results reveal that the thermal effect and the bare AC have little influence by themselves on the HDO process at 375 °C.

2.4.2. Effects of the Impregnation Methodology

To evaluate the effects of the impregnation methodology on the properties and activity of the resulting catalysts, Pt was deposited onto the surface of unmodified AC P54 using either incipient wetness impregnation (Pt/P54-i) or wet impregnation (Pt/P54-w), initially without HCl addition to the impregnating solution. Both catalysts obtained presented relatively high HDO activity: the products obtained after 8 h tests for lauric acid HDO using Pt/P54-i and Pt/P54-w presented AIs of 13.0 and zero, respectively (Entries 3 and 4 in

Table 7). The higher activity of the catalyst prepared by wet impregnation can be attributed to its: (i) higher Pt content, which was 0.65 wt% for Pt/P54-w and 0.42 for Pt/P54-i (

Table 5); (ii) higher Pt dispersion, which can be evidenced by the smaller average Pt particles size of Pt/P54-w (3.9 nm) compared with Pt/P54-i (5.2 nm) (

Table 6).

The higher Pt dispersion presented by Pt/P54-w could be explained as follows. During impregnation, it is believed that Pt-containing species are promptly adsorbed on the more easily accessible support surface; that is to say, on the external surface and the surface of the wider pores. Thus, if incipient wetness impregnation is employed, the material would be dried and calcined with most of the Pt deposited on these surfaces. In this scenario, the solute diffusion into the pores network would be controlling the process, giving rise to a relatively low metal dispersion. On the other hand, if wet impregnation is employed, the prolonged contact time between the support surface and the abundant impregnating solution would reverse the initial adsorption on the more easily accessible surface, so that the Pt-containing species could penetrate into smaller pores. In this scenario, the process would be under thermodynamic control, with a higher metal dispersion being achieved. This hypothesis is corroborated by the fact that, compared to Pt/P54-i, Pt/P54-w presented a higher Pt content determined by ICP/OES (a bulk technique), but a lower Pt content determined by XPS (a technique that probes the external surface). The Pt contents determined by ICP/OES were 0.65 and 0.42 wt% for Pt/P54-w and Pt/P54-i, respectively (

Table 5), while the corresponding values determined by XPS were 0.1 and 0.5 wt% (

Table 2).

In turn, the lower Pt content of Pt/P54-i could be explained by the fact that, during incipient wetness impregnation, part of the impregnating solution invariably spills from the material, thus carrying some of the metal with it, which ends up being deposited on the vessel walls (mainly on the bottom wall). On the other hand, if wet impregnation is employed, practically all metal-containing species would be adsorbed during the 24 h stirring step, so that only a small portion of metal would be lost by deposition on the vessel walls during the drying step.

2.4.3. Effects of the Pre-Treatment of the Support with HNO3

To evaluate the effects of pre-treating the support with HNO3, P54Ox was impregnated with the H2PtCl6 solution, initially without HCl addition. Since wet impregnation rendered the best catalysts in previous tests with the unmodified P54 support (Subsection 2.4.2), this impregnation methodology was used in this case and subsequently.

Despite its higher Pt content (determined by ICP/OES;

Table 5), Pt/P54Ox-w presented much lower HDO activity than Pt/P54,w. The AI of the products obtained in 5 h tests for lauric acid HDO using Pt/P54Ox-w and Pt/P54-w were 73.8 and 1.2, respectively (Entries 6 and 5 in

Table 7).

The higher Pt loading on Pt/P54Ox-w (compared with Pt/P54-w) is consistent with the idea that, as suggested by van Dam and van Bekkum [62], the lone electron pairs on the oxygen atoms and the π-electrons from the carbon basal planes would act as active sites for anchoring Pt-containing complexes, because these electrons would coordinate to Pt. In this sense, the higher Pt loading on Pt/P54Ox-w would be explained by the much higher content of acidic oxygenated functional groups on the support P54Ox.

In turn, the lower activity of Pt/P54Ox-w can be attributed to the lower Pt dispersion in this catalyst, diagnosed by the presence of larger Pt particles (see Subsection 2.3). This lower Pt dispersion can be understood by taking into account the abundance of carboxylic acids over P54Ox. As shown in Subsection 2.1, carboxylic acids decompose below ~400 °C, which means that they decompose in the reduction step during catalyst preparation. Therefore, as suggested by de Miguel et al. [59] and Coloma et al.[63], the Pt-species anchored to these groups would acquire mobility, thus favoring Pt sintering.

At this point, it is worth mentioning that it could be stated that the lower Pt dispersion over the Pt/P54Ox-w,ac catalyst could be due to the high concentration of negatively charged groups on the support surface, due to the deprotonation of the abundant acid groups. Thus, the negatively charged surface would undergo electrostatic repulsion with the Pt-containing anions, which would favor Pt sintering. However, this phenomenon would be likely to occur in basic media, as reported by Okhlopkova [50], but not at the acidic pH of a H2PtCl6 solution, where the deprotonation of the acidic surface groups is unfavorable.

2.4.4. Effects of the Thermal Pre-Treatment of the Support in H2 Atmosphere

To evaluate the effects of the thermal treatment of the support in H

2 atmosphere, P54Red was impregnated with the H

2PtCl

6 solution using the wet methodology, initially without HCl addition. The obtained catalyst (Pt/P54Red-w) exhibited a slightly lower HDO activity than its counterpart catalyst prepared with the unmodified AC Pt/P54-w. The AIs of the products obtained after 5 h in the test for lauric acid HDO using Pt/P54Red-w and Pt/P54-w were 2.6 and 1.2, respectively (Entries 7 and 5 in

Table 7).

The high HDO activity displayed by Pt/P54Red-w, despite its much lower content of oxygenated functional groups compared to the unmodified AC P54 (see Subsection 2.2.1), can be considered as evidence that basic sites such as carbonyl groups and π-electrons are active sites for the anchoring of Pt-containing species. Furthermore, as initially proposed by Van Dam and van Bekkum [62] and later confirmed by Sepúlveda-Escribano et al. [64] and de Miguel et al. [65], O-poor surfaces (as it is the case for P54Red) are prone to be oxidized by [PtCl

6]

2- ions (Equation (1)), such that the resulting phenolic groups would also contribute to the anchoring of the formed [PtCl

4]

2- ions.

Remarkably, phenol groups did not decompose in the reduction step during catalyst preparation, so that the Pt dispersion on Pt/P54Red-w would be favored. Furthermore, we believe that, for steric reasons, the coordination of the resulting square planar complex [PtCl

4]

2- (Equation (2)) is favored compared to that of the octahedral complex [PtCl

6]

2- (Equation (3)).

2.4.5. Effects of Acidifying the Impregnating Solution with HCl

To investigate the effects of acidifying the impregnating solution with HCl, the syntheses of all catalysts were repeated, but with HCl added to the H2PtCl6 solution. The effects of this operation depended on the support used and the impregnation methodology, as depicted in the sequence.

For the catalysts prepared by incipient wetness impregnation, HCl addition to the impregnating solution significantly increased the HDO activity. The 8 h test for lauric acid HDO with the catalyst prepared with HCl addition (Pt/P54-i,ac) rendered a product with AI 1.9 (Entry 8 in

Table 7), while the product obtained using the counterpart catalyst prepared without HCl addition (Pt/P54-i) presented an AI of 13.0 (Entry 3 in

Table 7). These results can be attributed to: (i) the higher Pt content of Pt/P54-i,ac (the Pt contents of Pt/P54-i and Pt/P54-i,ac (determined by ICP/OES) were 0.42 and 0.58 wt%, respectively;

Table 5); the higher Pt dispersion over Pt/P54-i,ac, as revealed by the smaller average Pt particle size of Pt/P54-i,ac (3.0 nm) compared with that of Pt/P54-i (5.2 nm) (

Table 6). A likely explanation for these findings is that, since Cl

‒ is a product of all reactions in Equations (1)–(3), HCl addition to the impregnating solution would shift the equilibria to the left side, thus disfavoring the coordinative adsorption mechanism. Therefore, we believe that the adsorption of Pt-containing species is slowed down, so that they would penetrate deeper into the pores network, leading to a higher Pt dispersion. Furthermore, this scenario would end up reducing the Pt lost for the vessel’s walls, which would justify the higher Pt loading measured by ICP/OES for Pt/Pt54-i,ac compared to Pt/Pt54-i (

Table 5).

On the other hand, in the case of catalysts prepared by wet impregnation, HCl addition to the impregnating solution was detrimental to the HDO activity when using the unmodified AC P54 or the oxidized AC P54Ox as support. The 5 h tests for lauric acid HDO using Pt/P54-w,ac and Pt/P54-w rendered products with AI 7.0 and 1.2, respectively (Entries 10 and 5 in

Table 7); in turn, when using Pt/P54Ox-w,ac and Pt/P54Ox-w, the corresponding values were 81.0 and 73.6 (Entries 11 and 6 in

Table 7). These results can be interpreted as follows. If, on one hand, during incipient wetness impregnation, the addition of HCl is important to disfavor the rapid adsorption of Pt-containing species on the most accessible surface and therefore to allow a deeper penetration of Pt into the pores network, on the other hand, wet impregnation leads by itself to an appropriate diffusion of the Pt-containing species, as depicted in Subsection 2.4.2. Therefore, in the cases of P54 and P54Ox ACs, the only effect of adding HCl to the impregnating solution is to weaken the interactions of the Pt-containing species with the support surface (see pertinent considerations in the previous paragraph), so that Pt sintering is favored during the subsequent reduction step, resulting in a lower Pt dispersion.

Contrary to what was observed with the more acidic ACs P54 and P54Ox, in the case of the reduced AC P54Red, the addition of HCl to the H

2PtCl

6 solution resulted in a catalyst with improved HDO activity. The AIs of the products obtained in the 5 h tests for lauric acid HDO using Pt/P54Red-w,ac and Pt/P54Red-w were 0.4 and 2.6, respectively (Entries 12 and 7 in

Table 7). The high HDO activity presented by Pt/P54Red-w,ac can be attributed to its high Pt dispersion, as evidenced by the large number of small Pt particles in the EDX elemental mapping image in

Figure 1f. Accordingly, Pt/P54Red-w,ac presented the smallest average Pt particle size (2.7 nm) in

Table 6. We believe that the improvement of Pt dispersion promoted by the addition of HCl to the impregnating solution when the more basic AC P54Red was employed as support can be explained as follows: the low pH of the impregnating solution would favor the protonation of basic sites, resulting in a positively charged surface that would promote strong attractive electrostatic interaction with the Pt-containing anions, thus disfavoring Pt sintering and increasing Pt dispersion.

At this point, it is worth highlighting that Regalbuto’s research group published several works in which they consider electrostatic interaction as the main mechanism for the adsorption of Pt-containing species (see, just as examples, references [66,67]. However, we believe this to be true only in the specific cases of: (i) predominantly basic ACs impregnated with anionic Pt-containing species (e.g., PtCl62‒) in acid pH; (ii) acidic ACs being impregnated with cationic Pt-containing species (e.g., Pt(NH3)42+) in basic medium. In the first case (corresponding to the preparation of Pt/P54Red-w,ac in the present work), the basic sites would be protonated, and the positively charged surface would thus promote electrostatic adsorption of Pt-containing anions. In the second case, the acidic sites would be deprotonated, and the negatively charged surface would thus promote electrostatic adsorption of the Pt-containing cations. In other scenarios, we believe that the coordinative mechanism portrayed in Equations (1)–(3) plays the main role in the adsorption of Pt-containing species. Otherwise, it would not be possible to explain why acidification of the impregnating solution led to a decrease in the activity of the resulting catalysts in cases where the more acidic catalyst ACs P54 and P54Ox were used.

2.4.6. Effect of in Situ Re-Reduction

Since, even after having been submitted to the reduction step, the prepared catalysts presented a considerable content of oxidized Pt due to the action of the atmospheric air (see Subsection 2.3), we initially adopted the procedure of performing an in-situ catalyst re-reduction step before the HDO tests, as described in Subsection 3.5. However, we later decided to evaluate the pertinence of performing this re-reduction. For that, the 5h time test for Lauric Acid HDO using the catalyst Pt/P54Red-w,ac was repeated, but without proceeding to the re-reduction step. Somewhat surprisingly, the results revealed that the re-reduction step is not only unnecessary, but it even slightly reduces the catalyst HDO activity. The suppression of the re-reduction step resulted in a product with AI zero, while the value verified for the product obtained in the equivalent test employing the re-reduction step had been 0.4 (Entries 13 and 12 in

Table 7, respectively). These findings evidence that the H

2 atmosphere and the relatively high temperature (375 °C) employed during the HDO tests are enough to rapidly reduce the layer of oxidized Pt formed on the surface of the Pt nanoparticles while, on the other hand, the performance of a re-reduction step at 400 °C supposedly provokes some Pt sintering, thus decreasing the of the catalyst activity.

Since the re-reduction step proved to be detrimental to the catalysts activity, it was suppressed in the subsequent HDO tests with coconut oil.

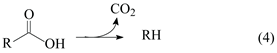

2.4.7. Composition of the Product of Lauric Acid HDO

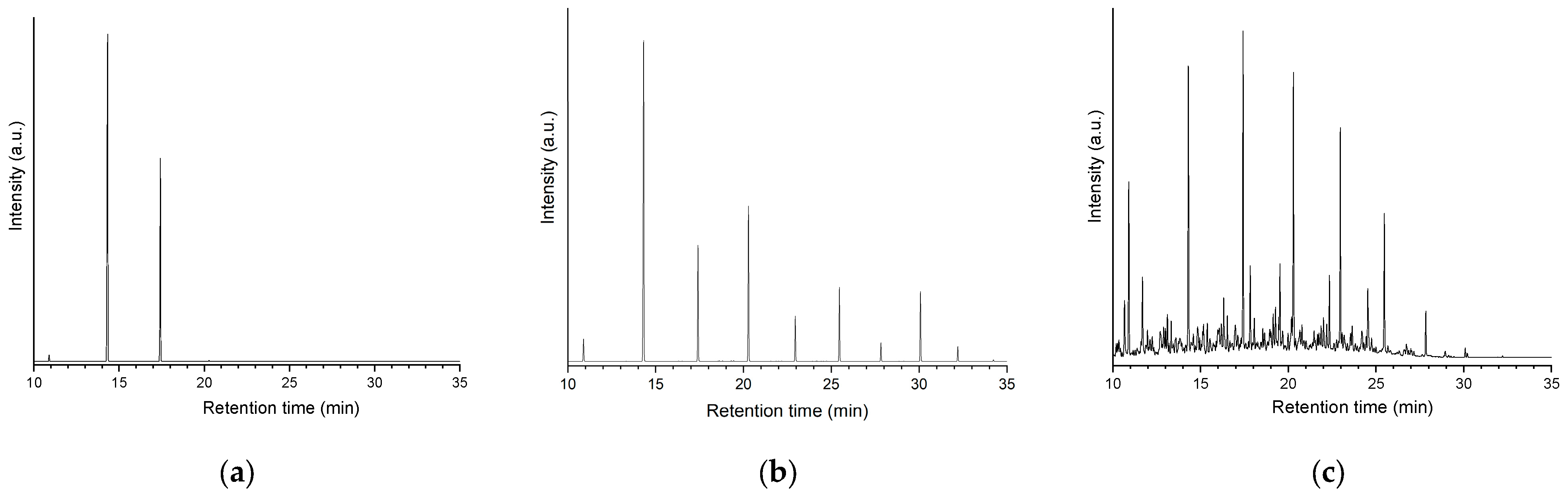

Figure 7a shows the GC/FID (gas chromatography/ flame ionization detector) chromatogram of the product obtained after the 5 h lauric acid HDO test using the Pt/P54Red-w,ac catalyst. This chromatogram presents only two significative peaks assigned to

n-undecane (

n-C

11) and

n-dodecane (

n-C

12). The former resulted from decarboxylation (DCX) and decarbonylation (DCN) reactions (Equations (4) and (5)), while the latter resulted from hydrogenation/dehydration reactions (Equation (6)). The relative areas for the

n-C

11 and

n-C

12 peaks were 64.4 and 35.6%, respectively.

The absence of peaks corresponding to shorter and branched chains reveals that cracking and isomerization reactions were not relevant, which is in agreement with the low acidity of the ACs support used (as displayed elsewhere [21], the acidity of the support plays an essential role in hydrocracking and hydroisomerization reactions), which reveals that DCX and DCN were the predominant pathways.

2.5. HDO Tests with Coconut Oil

Pt/P54Red-w,ac was the catalyst that presented the highest activity for lauric acid HDO and, for this reason, was employed in the HDO tests with coconut oil. Unlike the tests with lauric acid, the product obtained in the 5 h test with coconut oil exhibited residual acidity, resulting in an AI of 1.4 (Entry 14 in

Table 7). This result can be attributed to the fact that the triacylglyceride molecules in the oil must first be cleaved into propane and the corresponding fatty chains before the latter are deoxygenated. As expected, this additional reaction step, which involves a bulky molecule (the triacylglycerides), slows the conversion to alkanes. Therefore, aiming to provide a complete deoxygenation, the reaction time for coconut oil HDO was increased to 7 h. Indeed, this longer reaction time rendered a product with AI zero (Entry 15 in

Table 7). Accordingly, the chromatogram of the obtained product (

Figure 7b) presented only peaks corresponding to alkanes (basically

n-alkanes), which covered a large chain length range, emphasizing

n-C

11 and

n-C

12. These results are consistent with the coconut oil composition [61] and the HDO pathways presented in Equations (4)–(6).

As can be seen, the intensity of the peaks corresponding to alkanes with an odd number of carbons is always considerably higher than the intensity of the peaks relating to alkanes with even number of carbons, which is consistent with the predominance of the DCX and DCN pathways over the hydrogenation/dehydration pathway, as already verified in the tests with lauric acid (Subsection 2.4.7).

It is worth noting that, as expected (see the pertinent discussion an the beginning of Subsection 2.4), the alkanes present in the product of coconut oil HDO using Pt/P54Red-w,ac are in the same chain length range as in the petroleum-based commercial jet fuel QAV-1 (supplied by Petrobras Oil Company, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil) (compare Figures 7b and 7c). However, it is worth noting that, unlike the coconut oil HDO product, the chromatogram of QAV-1 has a marked presence of peaks other than those corresponding to linear alkanes (i.e., branched isomers, naphthenics, and aromatics).

It would be desirable to compare the HDO activity of the catalysts prepared in the present work with that of other usual HDO catalysts. However, comparison with studies reported in the literature is rather difficult due to the wide range of reaction systems, feedstocks, and reaction conditions employed. Notwithstanding, we have previously reported [26] results concerning the use of two sulfided Mo-based catalysts in HDO tests using the same feedstock and reaction system as in the present work, as well as relatively similar reaction conditions (for example, the same catalyst/feedstock ratio, 0.05 in mass, but a somewhat lower reaction temperature). Both catalysts contained Ni as a promoter. One of them (sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4) was prepared by our team using the unmodified AC P54 as support; the other one (NiMoS/Al

2O

3) was a commercial catalyst supplied by Petrobras Oil Company (Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil), which had γ-Al

2O

3 as support. After 3 h of coconut oil HDO at 340 °C, sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 and NiMoS/Al

2O

3 rendered products with AI 1.1 and 6.3, respectively (Entries 17 and 18;

Table 7). In turn, the Pt-based catalyst Pt/P54Red-w,ac, prepared in the present work, rendered, after 3 h, a product with a considerably higher AI of 15.4, despite the higher temperature used (375 °C) (Entry 16 in

Table 7).

The above results can lead one to infer that Pt is less efficient than MoS2 for HDO. However, it is necessary to have in mind that Pt/P54Red-w,ac presented less than 1 wt% of loaded Pt, whereas sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 and NiMoS/Al2O3 presented almost 20 wt% of Mo, besides the Ni added as a promoter (the characterizations of sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 and NiMoS/Al2O3 are reported in references [26] and [21], respectively). At this point, it is worth highlighting that it is usual to employ much higher metal content in Mo-based catalysts than in Pt-based ones (see, just as a few examples, references [20,21,68,69] and [12,39,40,46,47] for Mo and Pt-based catalysts, respectively). The main reason is the high cost of Pt, which makes it mandatory to optimize the catalytic activity per mass unit of employed metal. It is achieved by employing low amounts of Pt per unit of support surface area, so that the metal dispersion is improved.

We also tested another Pt-based catalyst prepared by our team using a commercial SAPO-11 zeolite as support. This catalyst was previously characterized and employed to promote the hydroisomerization of

n-alkanes [21]. However, it showed a quite low HDO activity, so that the product obtained in a 5 h test for coconut oil HDO presented an AI of 153.8 (Entry 19 in

Table 7). We suspect that the main reason for the low HDO activity presented by Pt/SAPO-11 is related to the low available porosity of the SAPO-11 support (for comparison with the prepared ACs, the N

2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of SAPO-11 are presented in

Figure 1a). However, further investigation into this matter is required to draw more certain conclusions, which is, however, beyond the scope of the present work.

2.6. Catalyst Reusability

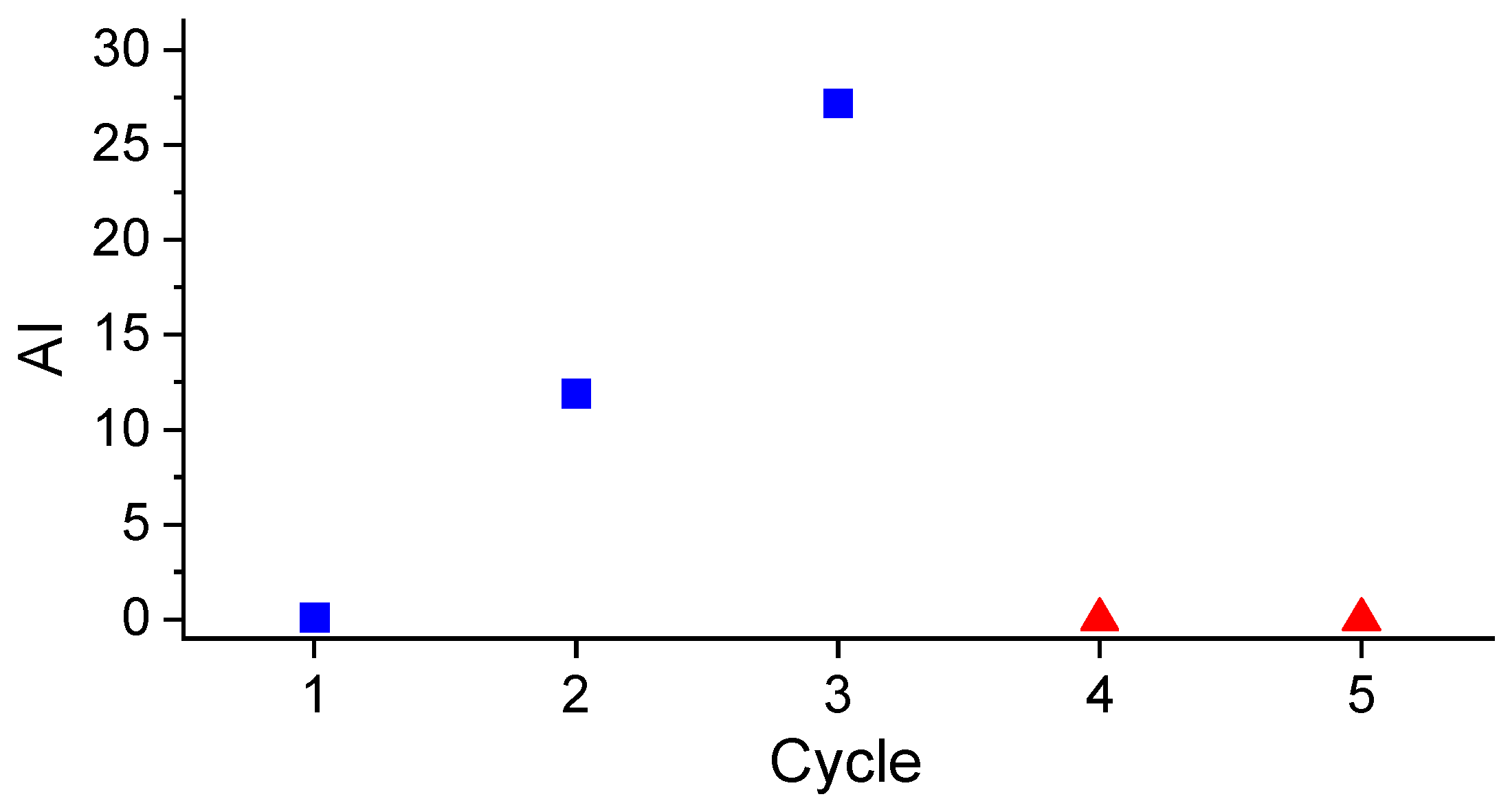

The reusability of Pt/P54Red-w,ac was investigated using the same catalyst sample in consecutive coconut oil HDO cycles. After each cycle, the spent catalyst was recovered from the liquid product by filtration and dried overnight at 100 °C. Small catalyst losses (about 2–4%) were compensated by adding equivalent amounts of fresh catalyst.

Figure 8 shows that there was a considerable and continuous activity loss throughout successive reaction cycles if no in situ re-reduction was carried out: the AI of the products obtained after the first, second, and third cycles were zero, 11.9, and 27.2, respectively. On the other hand, when an in-situ re-reduction step was inserted before a new cycle (as was the case in the fourth and fifth cycles), the catalyst activity was recovered. These results evidence that, during each cycle, the oxygenated reaction products (i.e., CO

2 and H

2O) cause Pt oxidation. This oxidation, occurring under the sever reaction conditions of temperature and pressure, would be deeper than the surface oxidation that occurs due to catalyst exposure to atmospheric air at ambient temperature and pressure, so the reaction conditions would not be sufficient to quickly recover catalyst activity at the beginning of a new reaction cycle. Therefore, an in-situ re-reduction step was necessary to bring the catalyst activity close to that presented by the fresh catalyst.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. P54 Preparation

A dried endocarp of coconut shell (Cocos nucifera L.) original from the region of Federal District, Brazil, was used as raw material in the synthesis of the AC P54. The endocarp was crushed and sieved, and the fraction in the range of 40–80 mesh (0.177–0.400 mm) was chemically activated with H3PO4 (85%; Vetec, Speyer, Germany) following a procedure described elsewhere [49]. Briefly, the shell was impregnated with an aqueous solution containing the desired amount of H3PO4 and carbonized up to 450 °C under an inert atmosphere (N2). Then, the carbonized material was washed with deionized water to remove the chemicals and dried at 110 °C overnight.

3.2. P54 Modification

P54 was treated with a 1.0 mol L−1 HNO3 solution. For that, 20 g of P54 were added to a beaker jar containing 200 mL of the acidic solution. The mixture was kept under reflux (~75 °C) and magnetic stirring for 1 h. After cooling, the solid was separated by filtration, washed with deionized water until a stable pH of around 6 and dried at 110 °C overnight.

P54 was also thermally treated up to 800 °C (2 h; 5 °C min‒1) under a H2 atmosphere (~100 mL min‒1) in a horizontal tubular furnace.

3.3. Preparation of the Pt-based Catalysts

Pt was deposited on the ACs from an aqueous solution of hexachloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6 ⋅ 6H2O; ≥ 99.9%; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) by two different methodologies: incipient wetting impregnation and wet impregnation. In the former, the impregnating solution was added dropwise over the AC, so that it diffused through the pores by capillarity. The solution volume (determined through preliminary tests on aliquot samples) corresponded to that beyond which the catalyst outside began to look wet. Then, the material was dried overnight at 110 °C. In turn, in the wet impregnation, an excess of impregnating solution was used (around 13 mL per gram of AC). The system was closed and kept under stirring for 48 h at 50 °C. After that, the excess water was evaporated by opening the system. Finally, the material was dried overnight at 110 °C.

The impregnating solutions contained H2PtCl6 in a concentration corresponding to 1.0 wt% of Pt relative to the support. In some tests, the solution was acidified with HCl equivalent to 8 times the number of mols of Pt. After impregnation, the material was reduced under H2 atmosphere (~100 mL min‒1) at 400 °C (2 h).

3.4. Characterization of ACs and Catalysts

The textural properties were characterized by adsorption/desorption isotherms of N2 (–196 °C) obtained on a volumetric automatic system Quantachrome NovaWin 2200e (Boynton Beach, Florida, USA). Specific surface area and Vmic were determined by applying the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Dubinin–Radushkevich (DR) equations, respectively. The volume of liquid N2 adsorbed at p/p0 0.95 was termed V0.95, which was considered as the sum of Vmic and Vmes. Thus, Vmes was determined by subtracting Vmic from V0.95.

The ACs had their contents of C, H and N determined by EA using a Parkin Elmer analyzer model EA 2400 Series II equipped with an AD6 ultra-microbalance (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The ash content was determined on a dry basis by heating the material at 600 °C for 6 h in a muffle furnace open to ambient air. The bulk content of Pt was determined by ICP/OES on an Agilent 5100 equipment (Santa Clara, California, USA).

TPD/MS analyses were carried out on an automated reaction system model AMI-90R coupled to a Dymaxion quadrupole mass spectrometer (Altamira Instruments, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA). The sample (~100 mg) was placed in a U-tube of quartz under Ar flow (10 cm3 min‒1; atmospheric pressure). The system was initially heated to 110 °C (10 °C min‒1; 30 min) to release physically adsorbed molecules. Then, the temperature was raised to 950 °C (10 °C min‒1). The emitted gases were monitored with the mass spectrometer. CO and CO2-profiles were fitted assuming a Gaussian distribution for each peak. Peak areas were correlated to the amount of gas through a daily routine calibration that consisted of the injection of a given volume of pure gas using a calibrated loop [70].

XPS measurements were performed on a Physical Electronics 5700 spectrometer using the Mg-Kα line (1253.6 eV) generated by a PHI model 04-548 Dual Anode X-rays Source (Chanhassen, Minnesota, USA) operating at 300 W (10 keV and 30 mA). The pressure inside the vacuum chamber was 5 × 10‒7 Pa. A Perkin Elmer 10-360 hemispherical analyzer (Eden Prairie, Minnesota, USA) with a multi-channel detector was employed. The samples were analyzed at an angle of 45° to the surface plane. BEs were referred to the C 1s line of adventitious carbon at 284.8 eV and determined with the resolution of ±0.1 eV. The spectra were fitted assuming a Gaussian-Lorentzian distribution for each peak.

HR-TEM was carried out with a TALOS F200x instrument operating in STEM (scanning transmission electron microscopy) mode, equipped with a HAADF (high-angle annular dark-field) detector, at 200 kV and 200 nA. The elemental mapping was carried out on an EDX Super-X system provided with 4 X-ray detectors and an X-FEG (field emission gun) beam (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, EUA).

XRD diffractograms were obtained on a Rigaku instrument model Miniflex 300 (Akishima-shi, Tokyo, Japan) using a Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm).

The contents of acidic and basic groups in the ACs were determined through a procedure adapted from the Boehm titration methodology, as detailed elsewhere [36].

3.5. HDO tests

Lauric acid (99.0%, Sigma Aldrich) and extra virgin coconut oil (98%; dr. Orgânico, Brazil) were used without further purification as feedstocks in the HDO tests. The tests were carried out in a cylindrical stainless-steel reactor with an internal volume of ~100 cm3 (a scheme of the reactor was presented elsewhere [21]). For in situ re-sulfidation, 0.500 g of catalyst was charged into the reactor and the system, after purged and pressurized with H2 at 20 bars, was heated to 400 °C for one hour. After that, the system was cooled down to room temperature, 10.0 g of feedstock were charged into the reactor under a N2 flow, the system was purged and pressurized again with H2 at 20 bars, and heated to 375 °C. The heating took around 45 min, and the time the temperature reached 375 °C was considered as the reaction time zero. Then, after the desired HDO reaction time, the system was cooled down to room temperature, and the liquid product was dried with Na2SO4 and separated by centrifugation. For the experiments in which re-sulfidation was not carried out, the first heating cycle was suppressed.

3.6. Characterization of the Reaction Products

The liquid reaction products were qualitatively analyzed by GC/MS (gas chromatography/mass spectrometry) using a Shimadzu GC-17a chromatograph interfaced with a QP5050A spectrometer (Kyoto, Japan). For quantitative analyses, GC/FID chromatograms were recorded on a Shimadzu GC-2010 equipment (Kyoto, Japan). A Rtx-5MS polydimethylsiloxane column (30 m, 25 mm) was used in both GC/MS and GC/FID analyses.

The AI of the reaction products was determined according to the AOCS methodology Cd-3d-63-O.

4. Conclusions

An AC was produced from chemically activating a dried coconut shell endocarp with H3PO4. This AC was: thermally treated up to 800 °C in a reductive atmosphere of H2 to remove oxygenated acidic functional groups; and treated with a refluxing HNO3 solution to increase the oxygenated acid functional group content. The unmodified and modified ACs were employed as support in Pt-based catalysts aimed at the synthesis of hydrocarbon biofuels via hydroprocessing of lipidic feedstocks. A systematic study on the effects of the preparation conditions on the properties and performance of the obtained catalysts was carried out for the first time.

Compared to incipient wetness impregnation, wet impregnation allowed better diffusion of Pt-containing species through the pores network of the supports, thus producing higher Pt dispersions and, consequently, more active catalysts.

The oxygenated functional groups and π-electrons on the carbon basal planes acted as active sites for the coordination of Pt-containing species. However, the presence of carboxylic acids is unfavorable, as these groups decompose during the Pt reduction step, allowing the Pt to become mobile and sinter. For this reason, catalysts prepared using the AC pre-treated with HNO3 as support presented low Pt dispersion and, therefore, poor HDO activity.

Acidification of the impregnating solution with HCl led to an alternative adsorption mechanism when using a more basic AC as support: the low pH of the impregnating solution favored the protonation of basic sites, resulting in a positively charged surface that promoted strong attractive electrostatic interaction with the Pt-containing anions, thus disfavoring Pt sintering and increasing Pt dispersion.

In this context, the catalyst with the highest HDO activity was the one prepared using the AC submitted to a thermal pre-treatment in a H2 atmosphere as support, and depositing Pt through wet impregnation of a H2PtCl6 solution acidified with HCl. The obtained catalyst promoted a complete deoxygenation of lauric acid and coconut oil, yielding products constituted mainly by n-alkanes. Catalyst stability was achieved by keeping the Pt in reduced form throughout the process.

The obtained results evidenced that Pt/AC catalysts have great potential to be used in the production of hydrocarbon biofuels through the hydroprocessing of lipidic feedstocks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org: Figures S1–S3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.J.P., E.R.-C., and P.A.Z.S.; funding acquisition, M.J.P., P.A.Z.S., and E.R.-C.; supervision, M.J.P.; formal analysis, M.J.P., A.M.d.F.J., R.D.B., R.C.D., P.A.Z.S., J.J.L.L., M.S.T., J.G., D.B.-P., and E.R.-C.; investigation, A.M.d.F.J., R.D.B., R.C.D., M.S.T., and D.B.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.P.; writing—review and editing, A.M.d.F.J., R.D.B., E.R.-C., and D.B.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.B.-P. and E.R.-C. thank the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, project PID2021-126235OB-C32 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and FEDER funds, and project TED2021-130756B-C31 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe” by the European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR. All authors thank CAPES (Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education, Brazil; Finance Code 001) for the financial support for this research.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Activated carbon |

| BET |

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| DR |

Dubinin–Radushkevitch |

| EDX |

Energy-dispersive X-ray |

| FEG |

Field emission gun |

| FID |

Flame ionization detector |

| GC |

Gas chromatography |

| HAADF |

High-angle annular dark-field |

| HDO |

Hydrodeoxygenation |

| HEFA |

Hydroprocessing of esters and fatty acids |

| HR |

High-resolution |

| ICP |

Inductively coupled plasma |

| IUPAC |

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| MS |

Mass spectrometry |

| OES |

Optical emission spectrometry |

| SAF |

Sustainable aviation fuel |

| SSA |

Specific surface area |

| STEM |

Scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| TEM |

Transmission electron microscopy |

| TPD |

Temperature-programmed desorption |

| Vmic

|

Micropores volume |

| Vmes

|

Mesopores volume |

| XPS |

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

References

- Prauchner, M.J.; Brandão, R.D.; de Freitas Júnior, A.M.; Oliveira, S.C. Alternative Hydrocarbon Fuels, with Emphasis on Sustainable Jet Fuels. Rev. Virtual de Química 2023, 15, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburto, J.; Castillo-Landero, A. Development of Advanced Sustainable Processes for Aviation Fuel Production. In Sustainable Aviation Fuels. Sustainable Aviation; Aslam, M., Mishra, S., Aburto Anell, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham: Switzerland, 2025; pp. 181–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Renewable Bio-Jet Fuel Production for Aviation: A Review. Fuel 2019, 254, 115599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.J.; Machado, P.G.; da Silva, A.V.; Saltar, Y.; Ribeiro, C.O.; Nascimento, C.A.O.; Dowling, A.W. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Technologies, Costs, Emissions, Policies, and Markets: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.S.; Pereira, M.F.R. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production through Catalytic Processing of Lignocellulosic Biomass Residues: A Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, M.A.; Serrano-Ruiz, J.C. Catalytic Production of Jet Fuels from Biomass. Molecules 2020, 25, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A.; Alves, C.T.; Onwudili, J.A. A Review of Current and Emerging Production Technologies for Biomass-Derived Sustainable Aviation Fuels. Energies 2023, 16, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amhamed, A.I.; Al Assaf, A.H.; Le Page, L.M.; Alrebei, O.F. Alternative Sustainable Aviation Fuel and Energy (SAFE)- A Review with Selected Simulation Cases of Study. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3317–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Parlett, C.M.A.; Fan, X. Recent Developments in Multifunctional Catalysts for Fatty Acid Hydrodeoxygenation as a Route towards Biofuels. Mol. Catal. 2022, 523, 111492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, G.; Miao, C. Green and Renewable Bio-Diesel Produce from Oil Hydrodeoxygenation: Strategies for Catalyst Development and Mechanism. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 568–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, L.; Cheng, S.; Julson, J. Review of Heterogeneous Catalysts for Catalytically Upgrading Vegetable Oils into Hydrocarbon Biofuels. Catalysts 2017, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Ma, L. Hydroprocessing of Lipids: An Effective Production Process for Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Energy 2023, 283, 129107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.R.C.; dos Santos, I.A.; Arcanjo, M.R.A.; Cavalcante, C.L.; de Luna, F.M.T.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Vieira, R.S. Production of Jet Biofuels by Catalytic Hydroprocessing of Esters and Fatty Acids: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.E.; Mohamed, A.R.; Kay Lup, A.N.; Koh, M.K. Palm Fatty Acid Distillate Derived Biofuels via Deoxygenation: Properties, Catalysts and Processes. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 236, 107394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, N.-S.; Toshtay, K.; Capron, M. Catalytic Applications in the Production of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) as a Renewable Fuel: A Review. Catalysts 2024, 14, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, N.; Sharma, R.V.; Dalai, A.K. Green Diesel Synthesis by Hydrodeoxygenation of Bio-Based Feedstocks: Strategies for Catalyst Design and Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 48, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Martínez-Klimov, M.; Murzin, D.Y. Hydroconversion of Fatty Acids and Vegetable Oils for Production of Jet Fuels. Fuel 2021, 306, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucantonio, S.; Di Giuliano, A.; Rossi, L.; Gallucci, K. Green Diesel Production via Deoxygenation Process: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itthibenchapong, V.; Srifa, A.; Kaewmeesri, R.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Faungnawakij, K. Deoxygenation of Palm Kernel Oil to Jet Fuel-like Hydrocarbons Using Ni-MoS2/γ-Al2O3 Catalysts. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017, 134, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumans, A.E.; Hensen, E.J.M. A Real Support Effect on the Hydrodeoxygenation of Methyl Oleate by Sulfided NiMo Catalysts. Catal. Today 2017, 298, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, R. D.; de Freitas Júnior, A. M.; Oliveira, S. C.; Suarez, P. A. Z.; Prauchner, M. J. The Conversion of Coconut Oil into Hydrocarbons within the Chain Length Range of Jet Fuel. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2021, 11, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.-J.; Lee, J. B.; Kim, Y.-J.; Cho, H.-R.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, G.-E.; Park, Y.-D.; Kim, G.-H.; An, J.-C.; Oh, K.; Park, J.-I. The Characteristics of Hydrodeoxygenation of Biomass Pyrolysis Oil over Alumina-Supported NiMo Catalysts. Catalysts 2024, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Mishra, A.; Anand, M.; Farooqui, S. A.; Sinha, A. K. Catalytic Hydroprocessing of Waste Cooking Oil for the Production of Drop-in Aviation Fuel and Optimization for Improving Jet Biofuel Quality in a Fixed Bed Reactor. Fuel 2023, 333, 126348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, O.İ.; Viljava, T.-R.; Krause, A.O.I. Hydrodeoxygenation of Aliphatic Esters on Sulphided NiMo/γ-Al2O3 and CoMo/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst: The Effect of Water. Catal. Today 2005, 106, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, E.; Delmon, B. Influence of Water in the Deactivation of a Sulfided Catalyst during Hydrodeoxygenation. J. Catal. 1994, 146, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Júnior, A.M.; Brandão, R.D.; Garnier, J.; Tonhá, M.S.; Mussel, W.d.N.; Ballesteros-Plata, D.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Prauchner, M.J. Activated Carbons as Supports for Sulfided Mo-Based Catalysts Intended for the Hydroprocessing of Lipidic Feedstocks. Catalysts 2025, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K.W.; Taylor, M.J.; Osatiashtiani, A.; Beaumont, S.K.; Nowakowski, D.J.; Yusup, S.; Bridgwater, A.V.; Kyriakou, G. Monometallic and bimetallic catalysts based on Pd, Cu and Ni for hydrogen transfer deoxygenation of a prototypical fatty acid to diesel range hydrocarbons. Catal. Today 2020, 355, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordouli, E.; Kordulis, C.; Lycourghiotis, A.; Cole, R.; Vasudevan, P. T.; Pawelec, B.; Fierro, J. L. G. HDO Activity of Carbon-Supported Rh, Ni and Mo-Ni Catalysts. Mol. Catal. 2017, 441, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordulis, C.; Bourikas, K.; Gousi, M.; Kordouli, E.; Lycourghiotis, A. Development of nickel based catalysts for the transformation of natural triglycerides and related compounds into green diesel: a critical review, Appl. Catal. B: Envir. 2016, 181, 156–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubička, D.; Horáček, J. Deactivation of HDS Catalysts in Deoxygenation of Vegetable Oils. Appl. Catal. A 2011, 394, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.; Luong, J.H.T. Carbon Materials as Catalyst Supports and Catalysts in the Transformation of Biomass to Fuels and Chemicals. ACS Catal. 2014, 10, 3393–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, M.S.; Asikin-Mijan, N.; Khalit, W.N.A.W.; Arumugam, M.; Izham, S.M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Effective catalytic deoxygenation of palm fatty acid distillate for green diesel production under hydrogen-free atmosphere over bimetallic catalyst CoMo supported on activated carbon. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 208, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, X. Hydrodeoxygenation of Model Compounds and Catalytic Systems for Pyrolysis Bio-Oils Upgrading. Catal. Sust. Energy 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahene, W. L.; Kivevele, T.; Machunda, R. The Role of Textural Properties and Surface Chemistry of Activated Carbon Support in Catalytic Deoxygenation of Triglycerides into Renewable Diesel. Catal. Commun. 2023, 181, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Coloma, F.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F. Platinum Catalysts Supported on Carbon Blacks with Different Surface Chemical Properties. Appl. Catal. A: General 1998, 173, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.C.; Dutra, R.C.; León, J.J.L.; Martins, G.A.V.; Silva, A.M.A.; Azevedo, D.C.S.; Santiago, R.G.; Ballesteros Plata, D.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Prauchner, M.J. Activated Carbon Ammonization: Effects of the Chemical Composition of the Starting Material and the Treatment Temperature. C – J. Carb. Res. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauchner, M. J.; Sapag, K.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Tailoring Biomass-Based Activated Carbon for CH4 Storage by Combining Chemical Activation with H3PO4 or ZnCl2 and Physical Activation with CO2. Carbon 2016, 110, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauchner, M. J.; Oliveira, S. da C.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Tailoring Low-Cost Granular Activated Carbons Intended for CO2 Adsorption. Front Chem 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.; Andrade, M.; Ania, C.O.; Martins, A.; Pires, J.; Carvalho, A.P. Pt/carbon materials as bi-functional catalysts for n-decane hydroisomerization, Microp. Mesop. Mat. 2012, 163, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soualah, A.; Lemberton, J.L.; Pinard, L.; Chater, M.; Magnoux, M.; Moljord, K. Hydroisomerization of long-chain n-alkanes on bifunctional Pt/zeolite catalysts: Effect of the zeolite structure on the product selectivity and on the reaction mechanism, Appl. Catal. A: General 2008, 336, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, J.K.; Główka, M.; Boberski, P.; Postawa, K.; Jaroszewska, K. The importance of hydroisomerization catalysts in development of sustainable aviation fuels: Current state of the art and challenges. J. Ind. Engin. Chem. 2025, (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Shaofeng, G.; Ning, C.; Shinji, N.; Eika, W.Q. Isomerization of n-alkanes derived from jatropha oil over bifunctional catalysts, J. Mol. Cat. A: Chemical, 2013, 370, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, N.K.L.; Faisal, A.; Wan, M.A.W.D.; Mohamed, K.A. A review on reactivity and stability of heterogeneous metal catalysts for deoxygenation of bio-oil model compounds, J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 56, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Angelika, S.O.; Prakashbhai, R.B. Recent progress of metals supported catalysts for hydrodeoxygenation of biomass derived pyrolysis oil, J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119957. [Google Scholar]

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Murzin, D.Y. Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin-Derived Phenols: From Fundamental Studies towards Industrial Applications. Catalysts 2017, 7, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Shaofeng, G.; Hisakazu, S.; Toshitaka, W.; Eika, W.Q. Effects of Si/Al ratio and Pt loading on Pt/SAPO-11 catalysts in hydroconversion of Jatropha oil, Appl. Catal. A: General 2013, 466, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Pastor-Pérez, L.; Villora-Pico, J.J.; Pastor-Blas, M.M.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Gu, S.; Charisiou, N.D.; Papageridis, K.; Goula, M.A.; Reina, T.R. Catalytic Conversion of Palm Oil to Bio-Hydrogenated Diesel over Novel N-Doped Activated Carbon Supported Pt Nanoparticles. Energies. 2020, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montakan, M.; Amaraporn, K.; Nattee, A.; Attasak, J. Biojet fuel production via deoxygenation of crude palm kernel oil using Pt/C as catalyst in a continuous fixed bed reactor, Energ. Conv. Manag. 2021, 12, 100125. [Google Scholar]

- Prauchner, M.J.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Chemical versus Physical Activation of Coconut Shell: A Comparative Study. Micro. Meso. Mat. 2012, 152, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhlopkova, L.B. Properties of Pt/C catalysts prepared by adsorption of anionic precursor and reduction with hydrogen. Influence of acidity of solution, Appl. Catal. A: General 2009, 355, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, N.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Lambert, S.; Cabiac, A.; Delahay, G.; Colomer, J.; Marien, J.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Pirard, J. Highly dispersed platinum catalysts prepared by impregnation of texture-tailored carbon xerogels, J. Catal. 2006, 240, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C. Accessing the Robustness of Adventitious Carbon for Charge Referencing (Correction) Purposes in XPS Analysis: Insights from a Multi-User Facility Data Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrı́guez-Reinoso, F.; Molina-Sabio, M. Textural and chemical characterization of microporous carbons. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 76–77, 271–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, J.A.; Phillips, J.; Xia, B.; Radovic, L.R. On the modification and characterization of chemical surface properties of activated carbon: In the search of carbons with stable basic properties. Langmuir 1996, 12, 4404–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivo-Vilches, J.F.; Bailón-García, E.; Pérez-Cadenas, A.F.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Maldonado-Hódar, F.J. Tailoring the surface chemistry and porosity of activated carbons: Evidence of reorganization and mobility of oxygenated surface groups. Carbon 2014, 68, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudani, N.; Souissi-najar, S.; Ouederni, A. Influence of nitric acid concentration on characteristics of olive stone based activated carbon. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 21, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Miyabayashi, K. Novel continuous flow synthesis of Pt NPs with narrow size distribution for Pt@carbon catalysts. RSC Adv., 2020, 10, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, S.R.; Vilella, J.I.; Jablonski, E.L.; Scelza, O.A.; Lecea, C.S.; Linares-Solano, A. Preparation of Pt catalysts supported on activated carbon felts (ACF), Appl. Catal. A: General 2002, 232, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmies, H.; Bergmann, A.; Drnec, J.; Wang, G.; Teschner, D.; Kühl, S.; Sandbeck, D.J.S.; Cherevko, S.; Gocyla, M.; Shviro, M.; Heggen, M.; Ramani, V.; Dunin-Borkowski, R.E.; Mayrhofer, K.J.J.; Strasser, P. Unravelling Degradation Pathways of Oxide-Supported Pt Fuel Cell Nanocatalysts under In Situ Operating Conditions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K.W.; Yusup, S.; Loy, A.C.M.; How, B.S.; Skoulou, V.; Taylor, M.J. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Deoxygenation of Plant Oils and Prototypical Fatty Acid Models Compounds: Catalysis, Process, and Kinetics. Mol. Catal. 2022, 523, 111469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, H.E.; Bekkum, H. Preparation of Platinum on Activated Carbon. J. Catal. 1991, 349, 335–349. [Google Scholar]

- Coloma, F.; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Fierro, J.L.G.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Gas phase hydrogenation of crotonaldehyde over Pt/activated carbon catalysts. Influence of the oxygen surface groups on the support. Appl. Catal. A General 1997, 1997 150, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Escribano, A.; Coloma, F.; Rodrı́guez-Reinoso, F. Platinum catalysts supported on carbon blacks with different surface chemical properties, Appl. Catal. A: General, 1998, 173, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, S.R.; Scelza, O.A.; Román-Martı́nez, M.C.; Lecea, C.S.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. States of Pt in Pt/C catalyst precursors after impregnation, drying and reduction steps, Appl. Catal. A: General, 1998, 170, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Barnes, S.; Regalbuto, J.R. A fundamental study of Pt impregnation of carbon: Adsorption equilibrium and particle synthesis, J. Catal. 2011, 279, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuser, G.S.; Banerjee, R.; Metavarayuth, K. Understanding Uptake of Pt Precursors During Strong Electrostatic Adsorption on Single-Crystal Carbon Surfaces. Top Catal 2018, 61, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojagh, H.; Creaser, D.; Tamm, S.; Arora, P.; Nyström, S.; Lind Grennfelt, E.; Olsson, L. Effect of Dimethyl Disulfide on Activity of NiMo Based Catalysts Used in Hydrodeoxygenation of Oleic Acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 5547–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, J.; Acelas, N.Y.; López, D.; Moreno, A. NiMo-Sulfide Supported on Activated Carbon to Produce Renewable Diesel. Univ. Sci. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.P.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Figueiredo, J.L. Characterisation of the Surface Chemistry of Carbon Materials by Temperature-Programmed Desorption: An Assessment. Catal. Today 2023, 418, 114136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

HR-TEM micrographs of the (a),(b) bare AC P54 and EDX elemental mapping images of (c) Pt/P54-i, (d) Pt/P54-i,ac, (e) Pt/P54Ox-w, and (f) Pt/P54Red-w.

Figure 1.

HR-TEM micrographs of the (a),(b) bare AC P54 and EDX elemental mapping images of (c) Pt/P54-i, (d) Pt/P54-i,ac, (e) Pt/P54Ox-w, and (f) Pt/P54Red-w.

Figure 2.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the (a) prepared ACs and a commercial SAPO-11 zeolite, as well as of (b) some selected prepared catalysts (closed and open symbols correspond to the adsorption and desorption branches, respectively).

Figure 2.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of the (a) prepared ACs and a commercial SAPO-11 zeolite, as well as of (b) some selected prepared catalysts (closed and open symbols correspond to the adsorption and desorption branches, respectively).

Figure 3.

(a) CO2 and (b) CO-TPD profiles of the prepared ACs.

Figure 3.

(a) CO2 and (b) CO-TPD profiles of the prepared ACs.

Figure 4.

High resolution N 1s core level spectrum of P54Ox.

Figure 4.

High resolution N 1s core level spectrum of P54Ox.

Figure 5.

High resolution Pt 4f core level spectra of some selected catalysts.

Figure 5.

High resolution Pt 4f core level spectra of some selected catalysts.

Figure 6.

X-ray diffractograms of some selected catalysts and the bare AC P54.

Figure 6.

X-ray diffractograms of some selected catalysts and the bare AC P54.

Figure 7.

GC/FID chromatograms of the product obtained after the tests of (a) lauric acid (5 h) and (b) coconut oil (7 h) HDO using the catalyst Pt/P54Red-w,ac (without in situ re-reduction); (c) the commercial petroleum-based jet fuel QAV-1.

Figure 7.

GC/FID chromatograms of the product obtained after the tests of (a) lauric acid (5 h) and (b) coconut oil (7 h) HDO using the catalyst Pt/P54Red-w,ac (without in situ re-reduction); (c) the commercial petroleum-based jet fuel QAV-1.

Figure 8.

AI verified throughout successive cycles of coconut oil HDO. In situ catalyst re-reduction was carried out only after the fourth and fifth cycles.

Figure 8.

AI verified throughout successive cycles of coconut oil HDO. In situ catalyst re-reduction was carried out only after the fourth and fifth cycles.

Table 1.

Textural properties of the bare ACs and prepared catalysts.

Table 1.

Textural properties of the bare ACs and prepared catalysts.

| Sample |

1 SSA (m2 g–1) |

Vmic (cm3 g–1) |

Vmes (cm3 g–1) |

V0.95 (cm3 g–1) |

| P54 |

1643 |

0.72 |

0.55 |

1.17 |

| P54red |

1367 |

0.60 |

0.32 |

0.92 |

| P54Ox |

1129 |

0.51 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

| Pt/P54-i |

1604 |

0.60 |

0.55 |

1.15 |

| Pt/P54-w |

1616 |

0.60 |

0.54 |

1.14 |

| Pt/P54Ox-w |

994 |

0.40 |

0.26 |

0.67 |

| Pt/P54Red-w |

1314 |

0.49 |

0.47 |

0.96 |

| Pt/P54-i,ac |

1646 |

0.62 |

0.56 |

1.19 |

| Pt/P54-w,ac |

1591 |

0.61 |

0.53 |

1.14 |

| Pt/P54Ox-w,ac |

935 |

0.39 |

0.22 |

0.61 |

| Pt/P54Red-w,ac |

1280 |

0.48 |

0.43 |

0.92 |

Table 2.

Surface elemental chemical composition of the bare unmodified and modified ACs, as well as some selected catalysts prepared in the present work, as determined by XPS.

Table 2.

Surface elemental chemical composition of the bare unmodified and modified ACs, as well as some selected catalysts prepared in the present work, as determined by XPS.

| Sample |

Content (wt%) |

| C |

O |

N |

P |

Si |

Pt |

| P54 |

85.9 |

11.9 |

- |

1.9 |

0.4 |

- |

| P54red |

89.3 |

8.0 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

0.7 |

- |

| P54Ox |

61.0 |

32.4 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

0.6 |

- |