Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

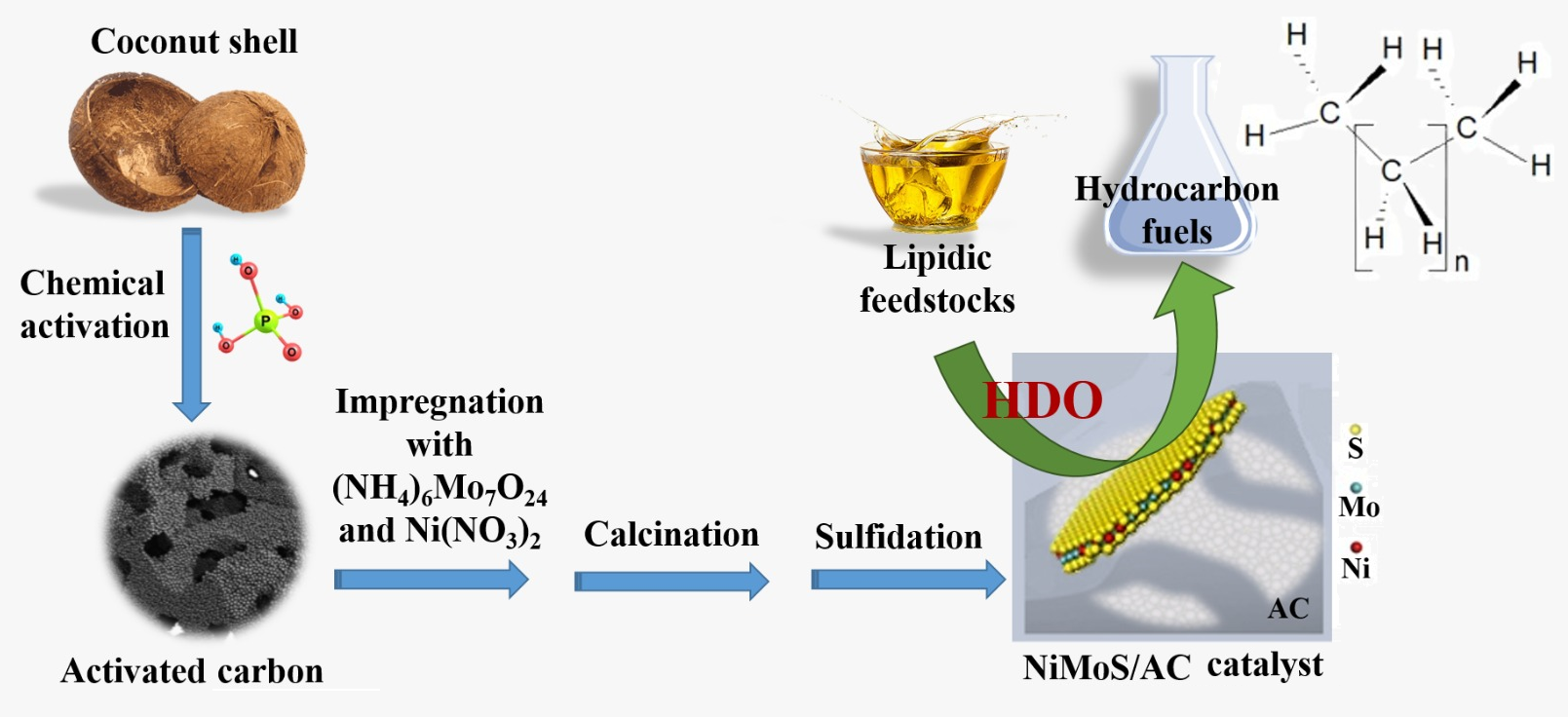

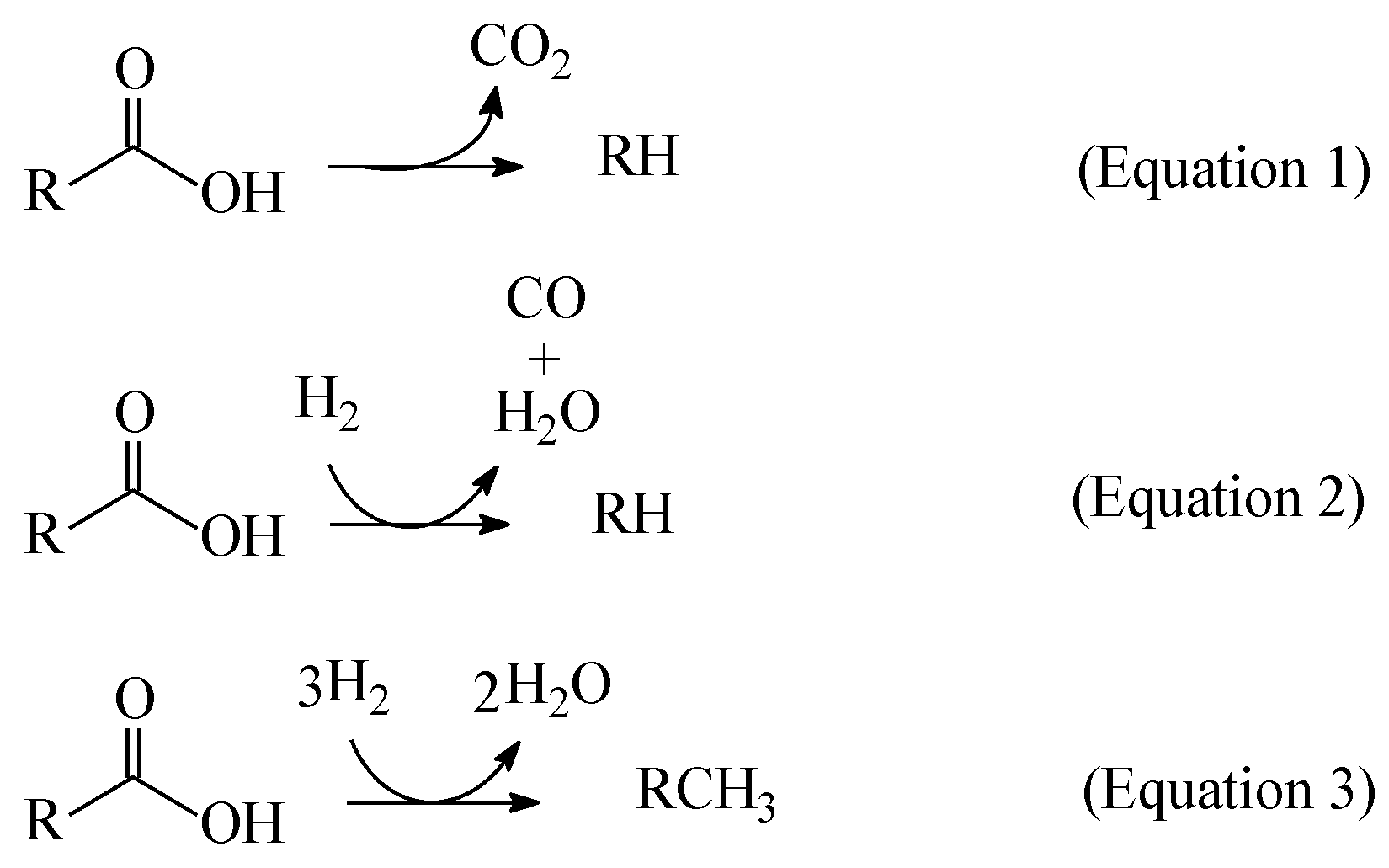

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

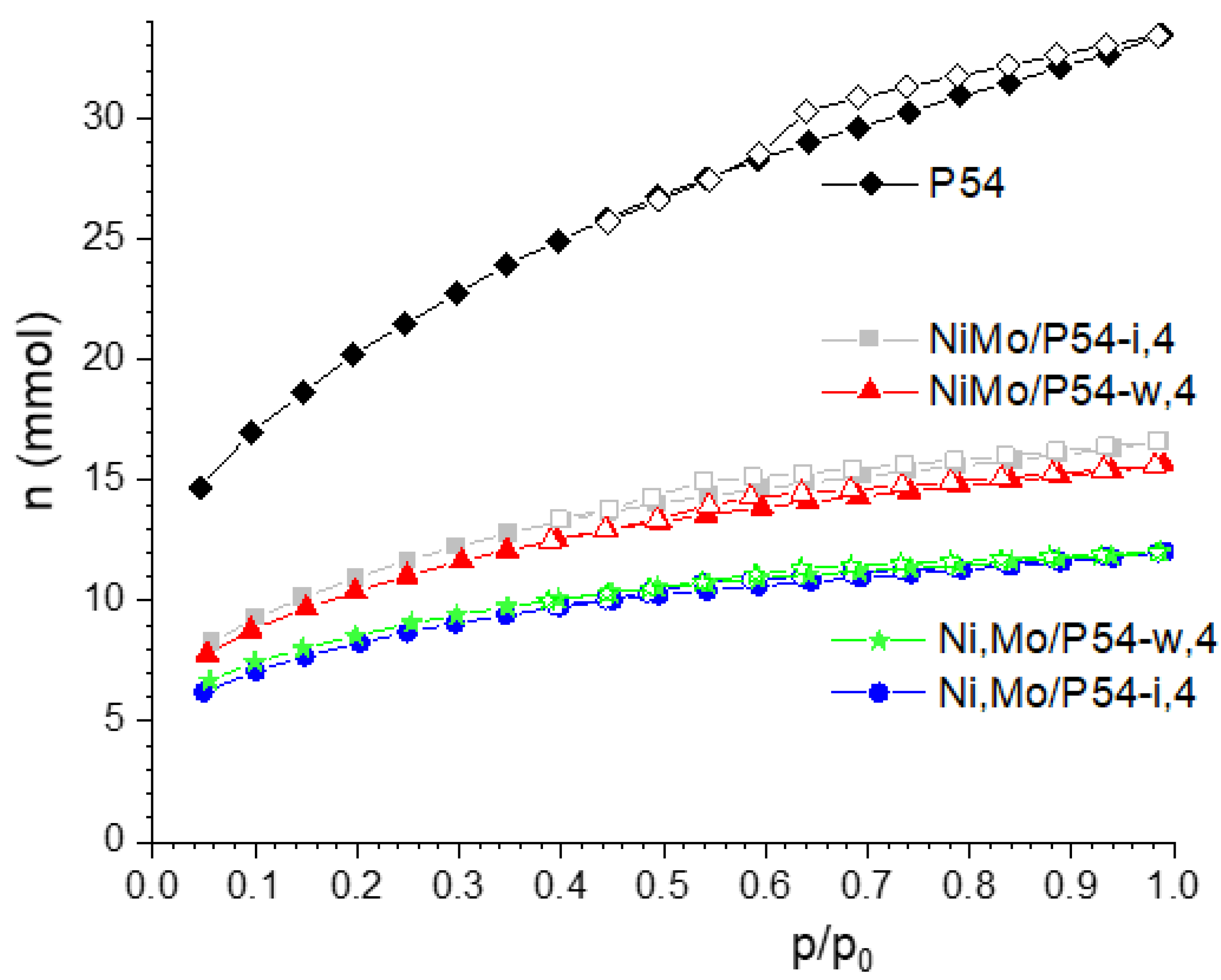

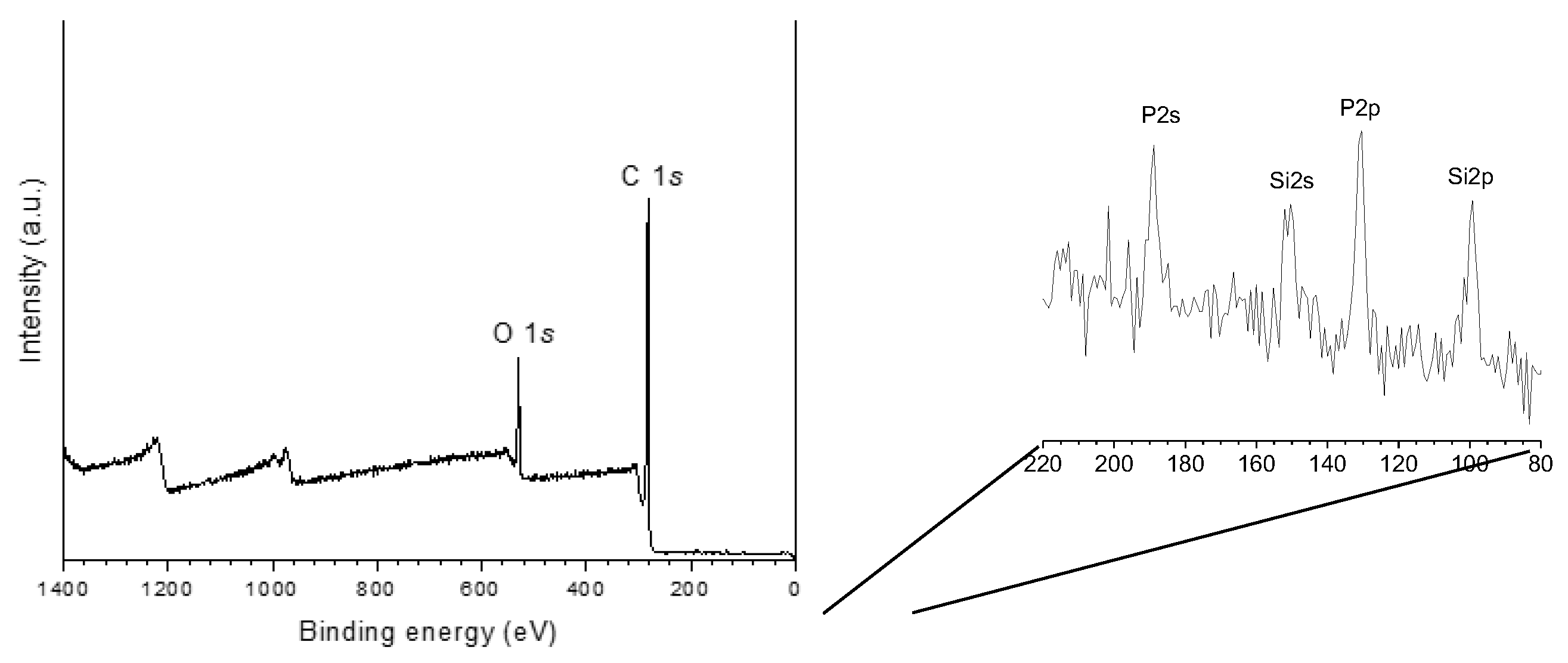

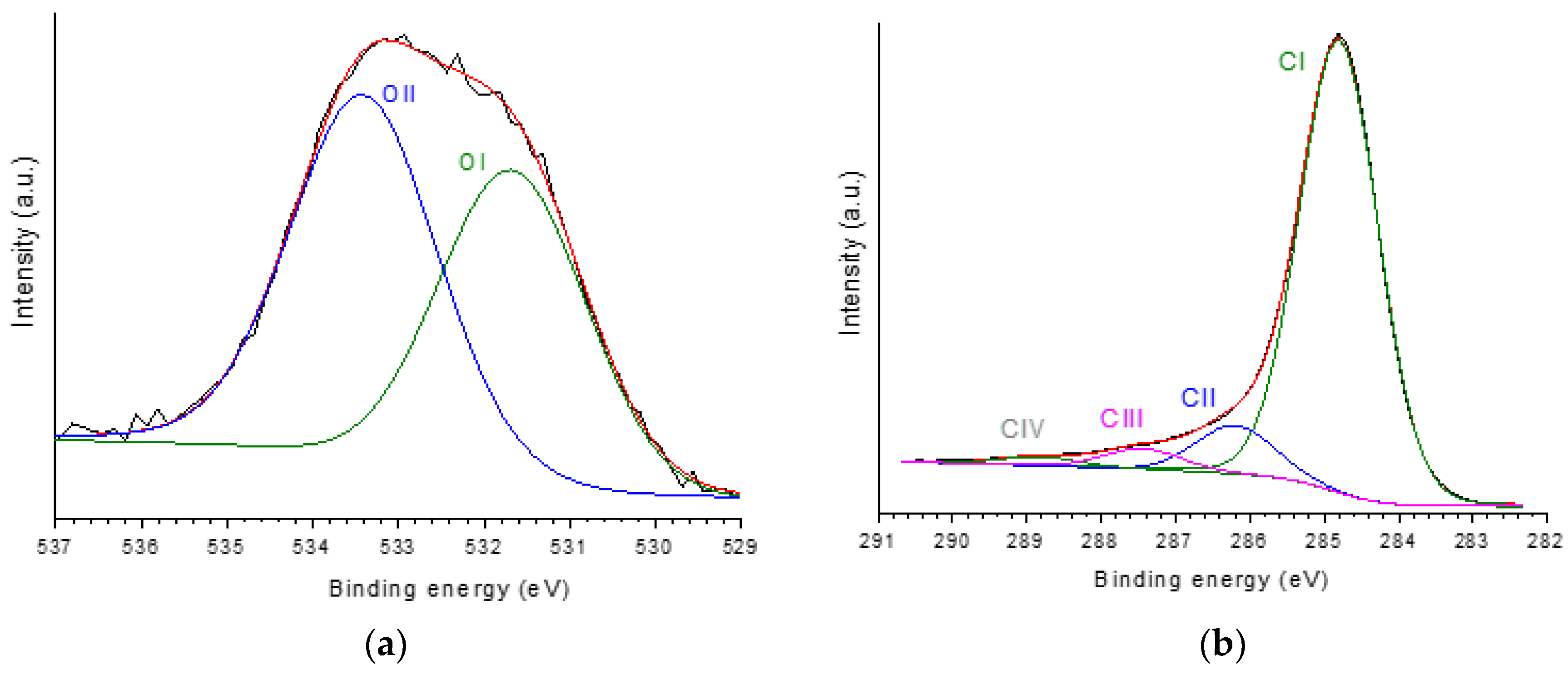

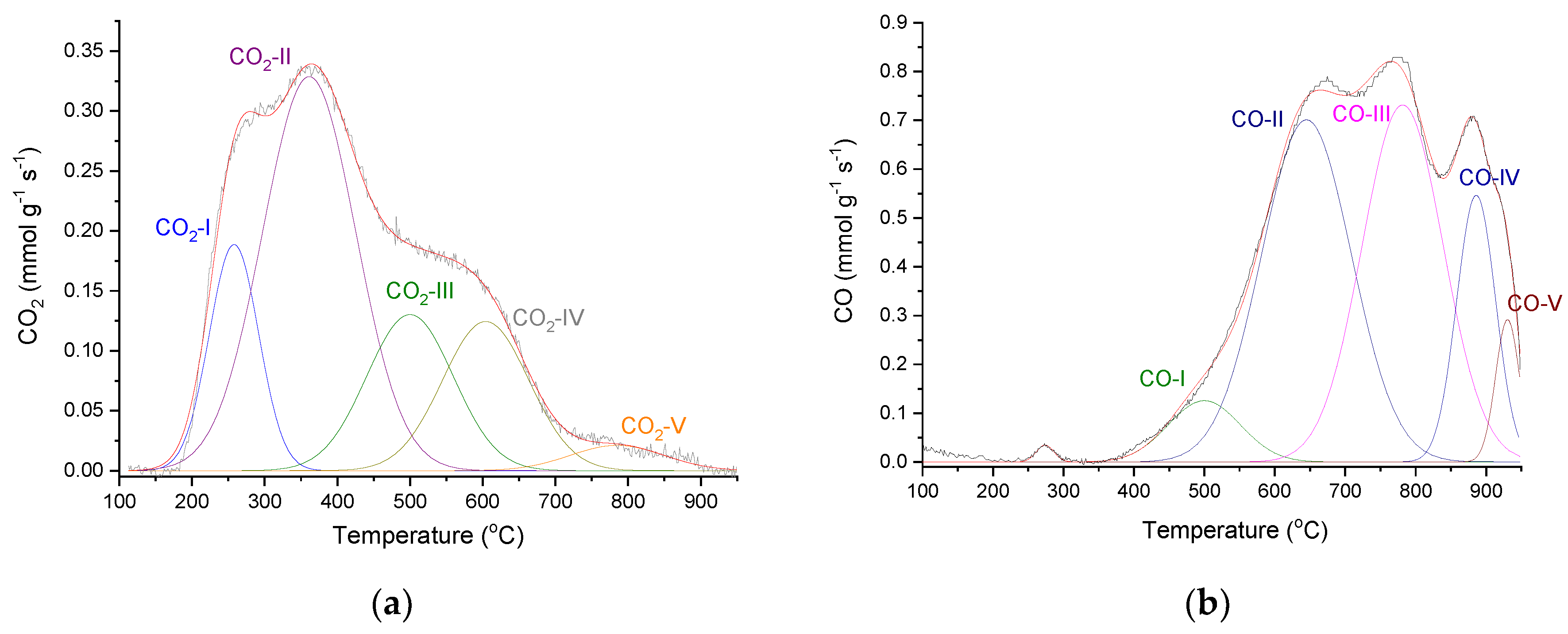

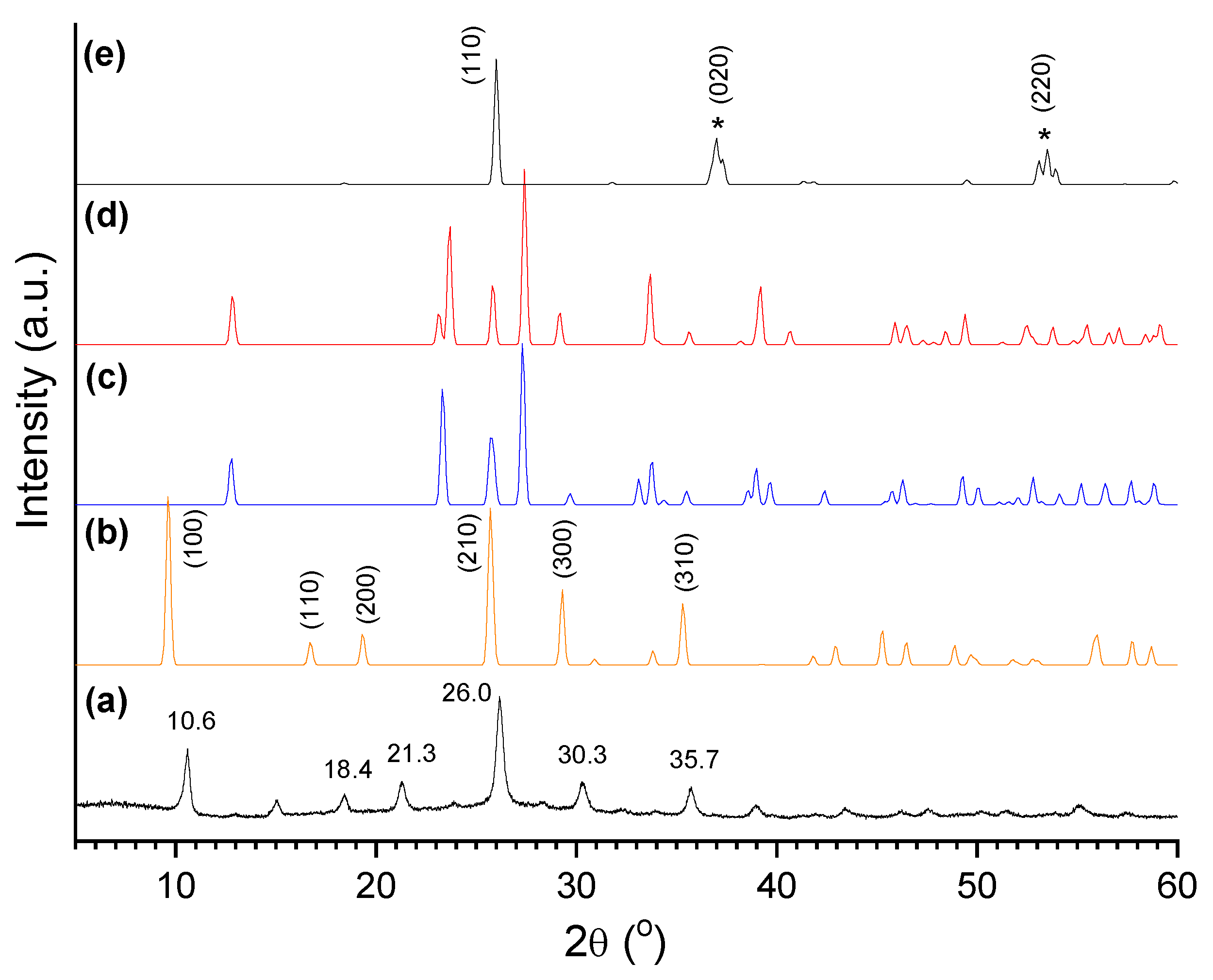

2.1. AC Characterization

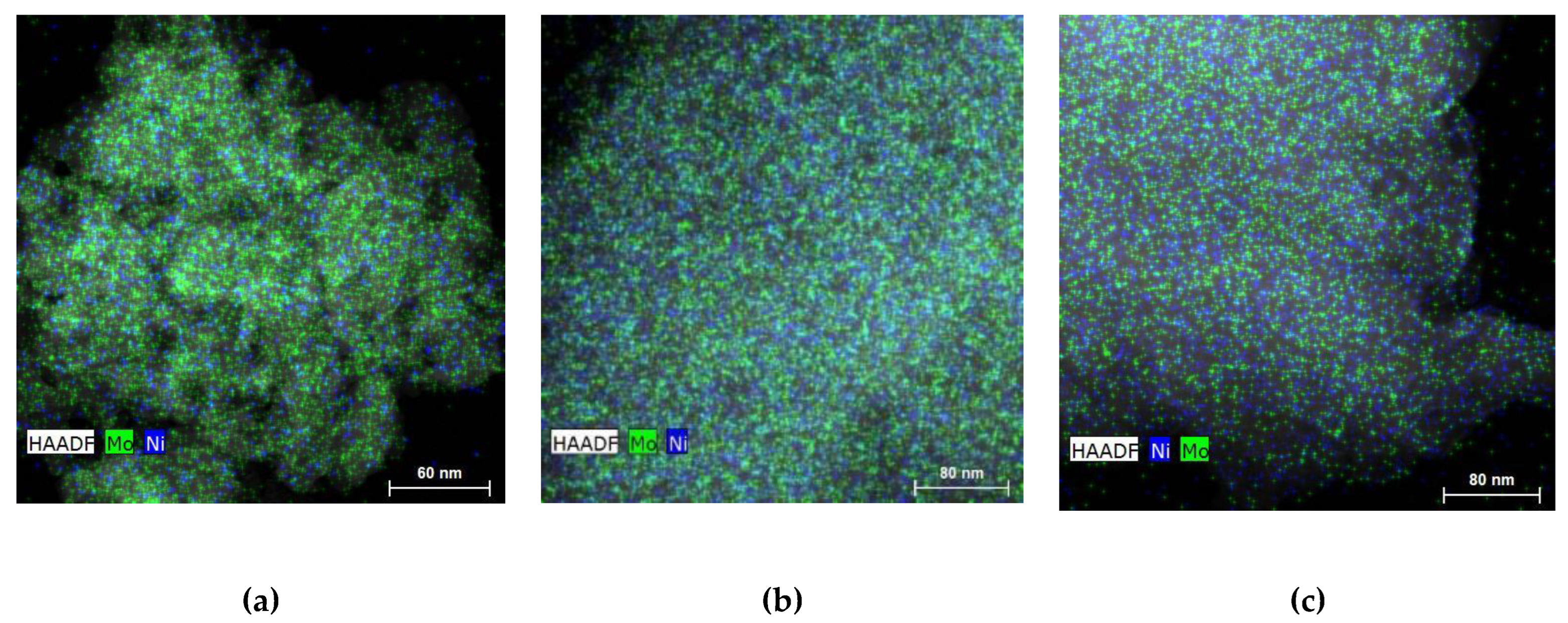

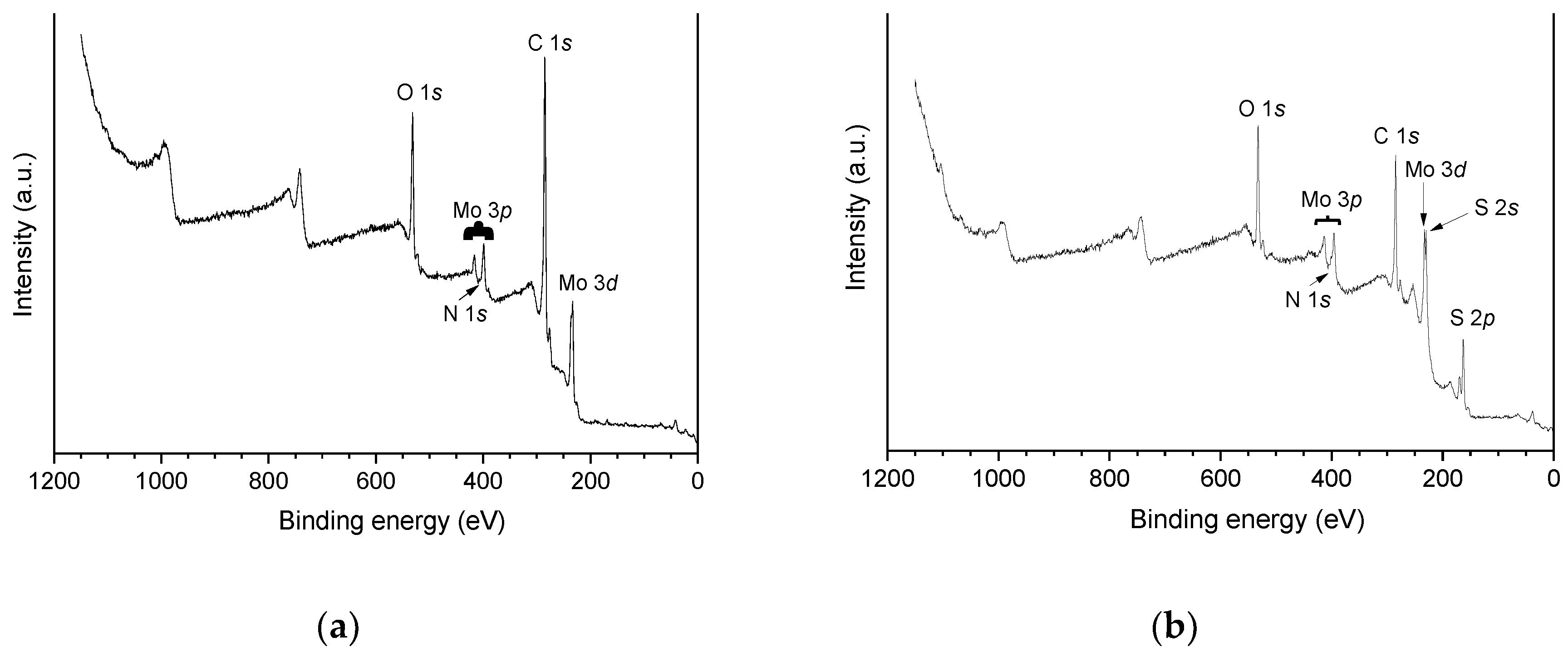

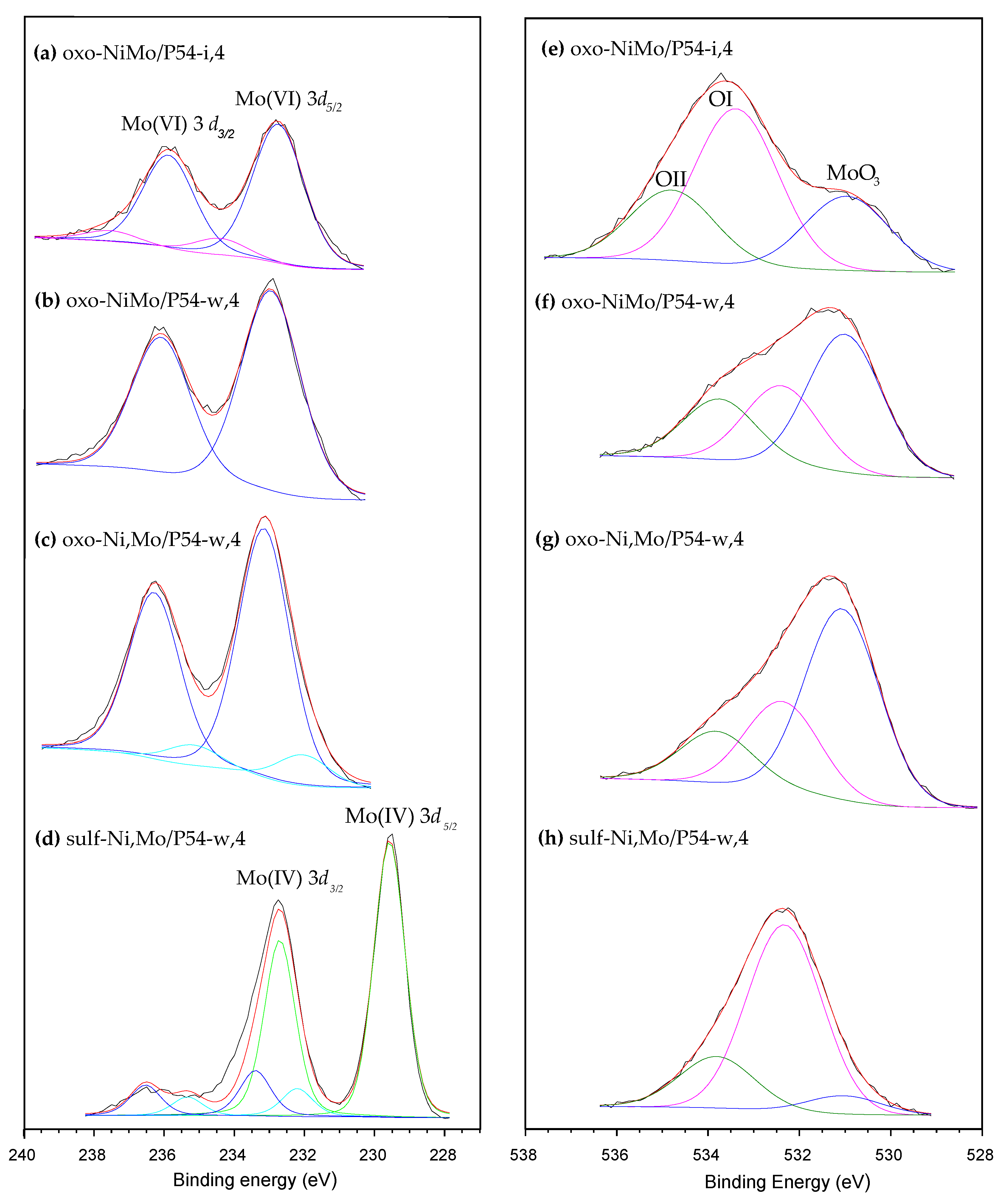

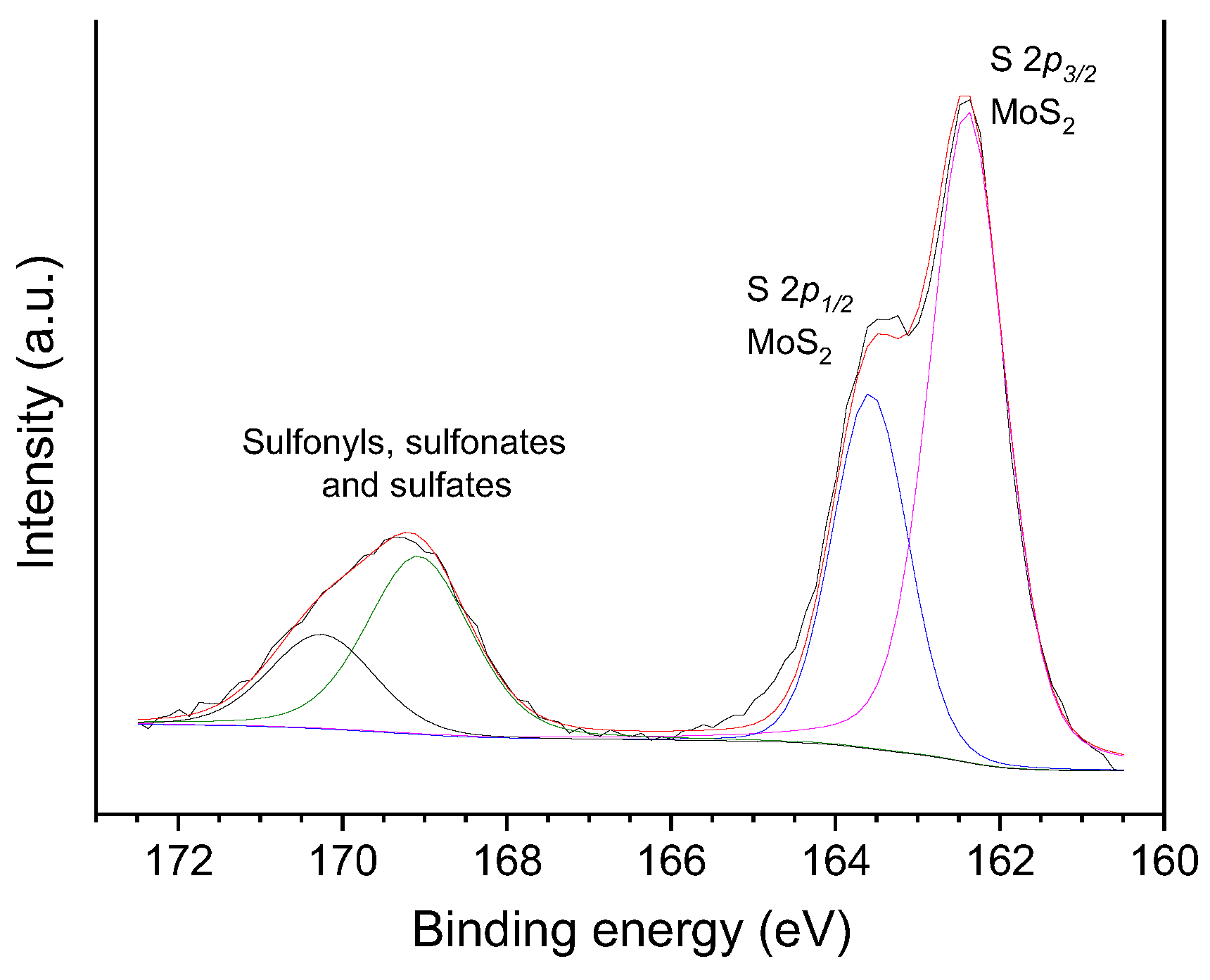

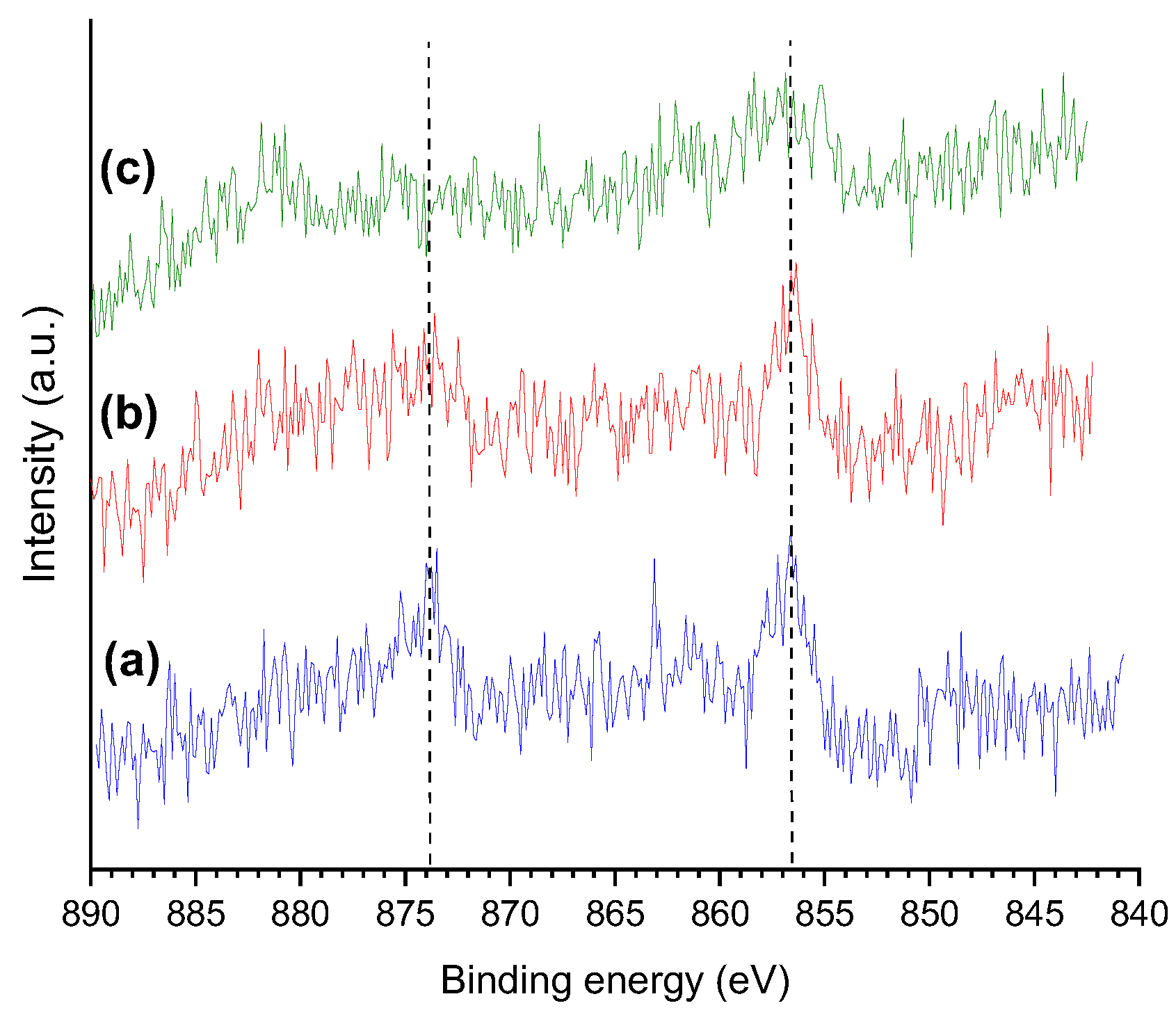

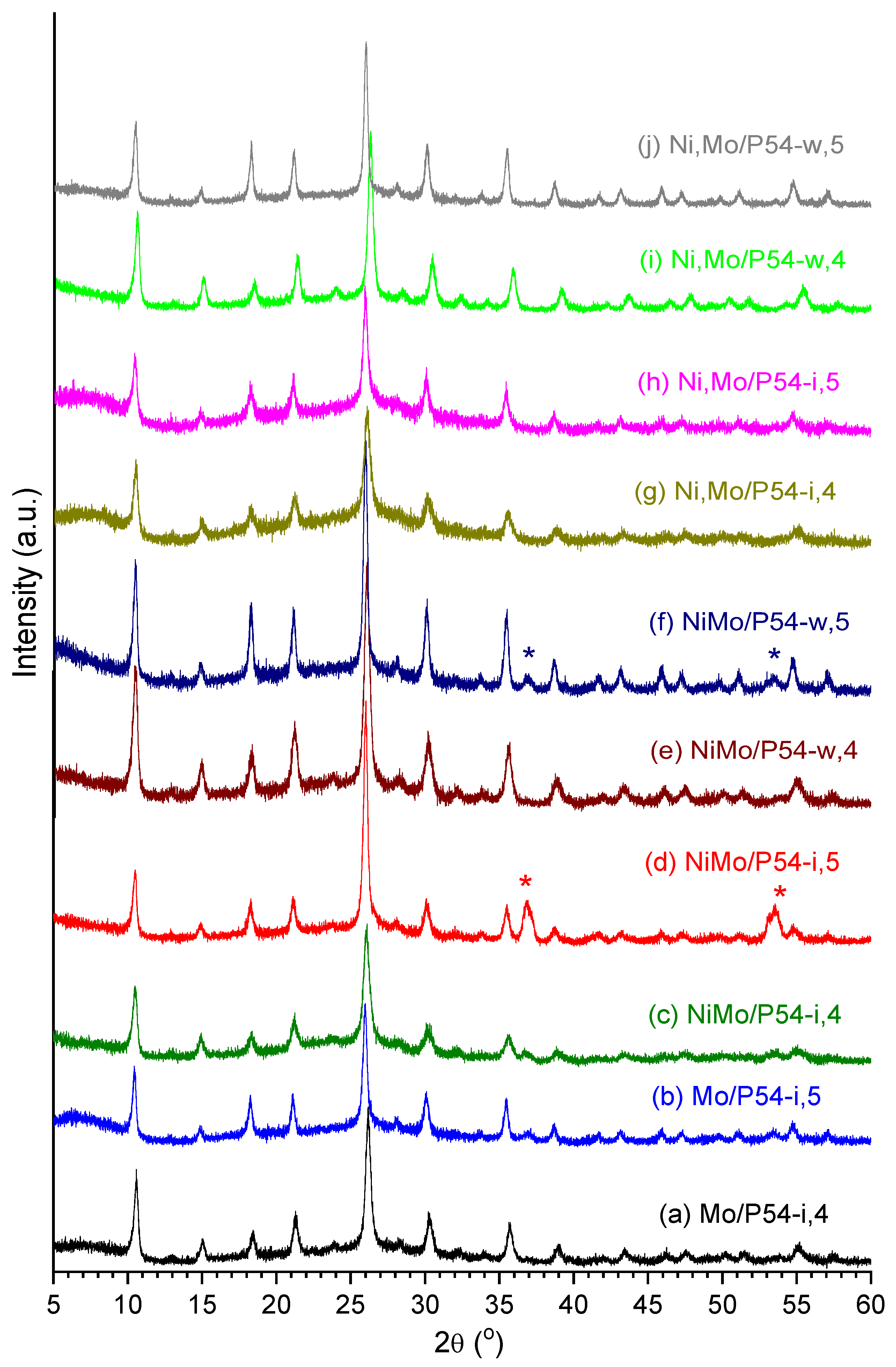

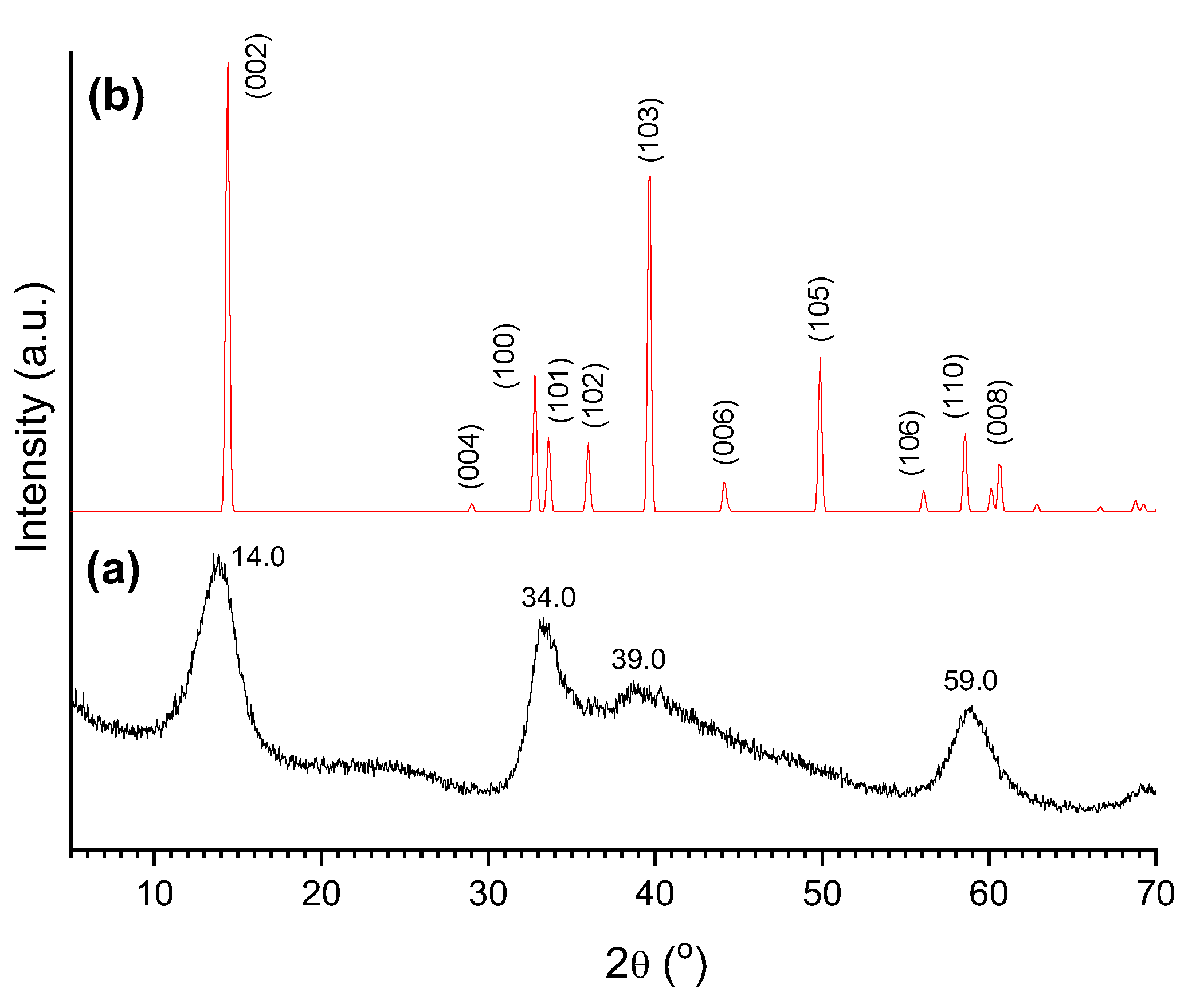

2.2. Catalysts Characterization

2.3. Searching for the Best Conditions to Prepare the Catalysts

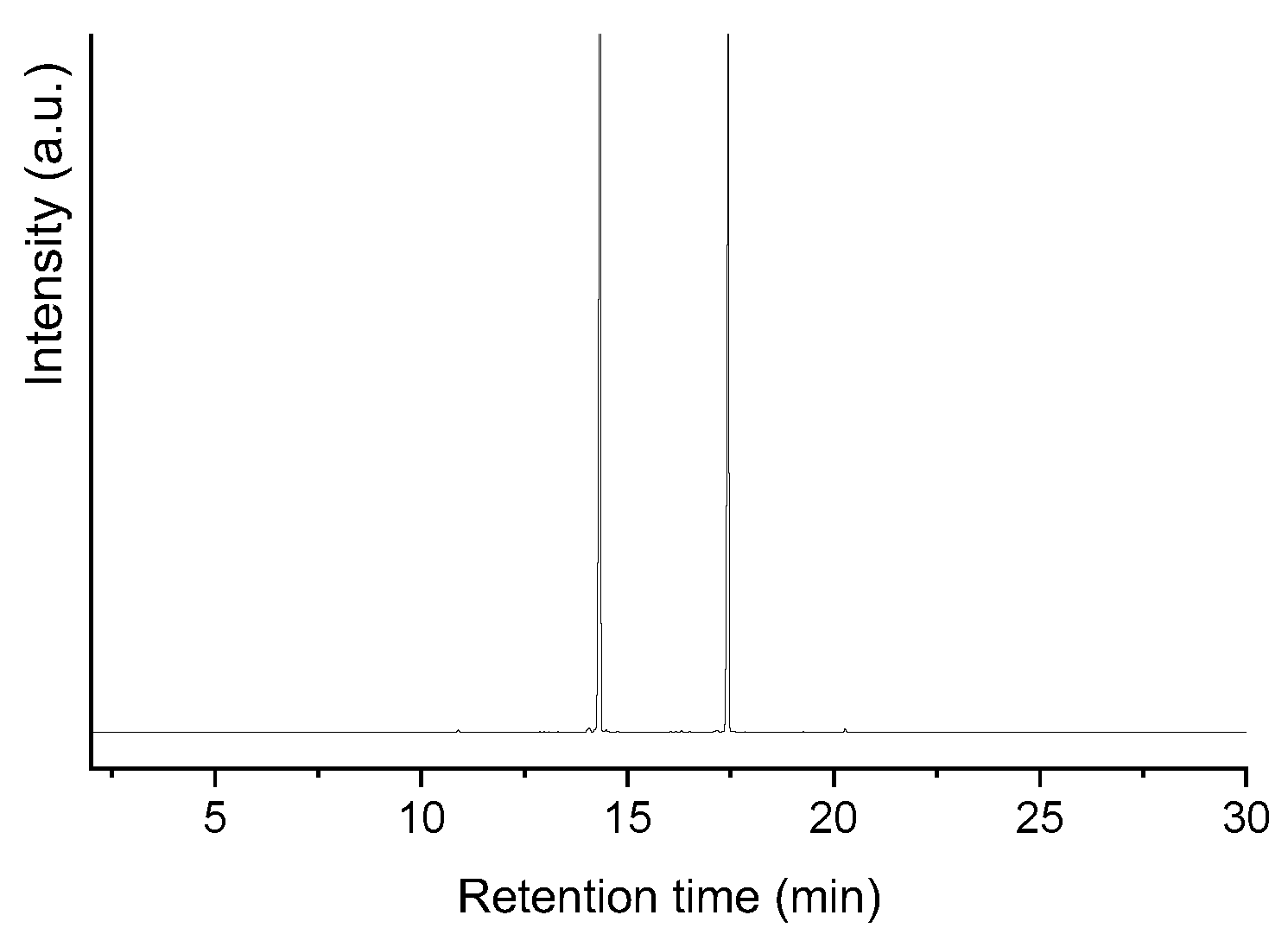

2.3.1. Blank Test

2.3.2. Catalysts Containing Mo as the Only Active Phase

2.3.3. Effects of Ni Incorporation

2.3.3.1. Co-Impregnation of Mo and Ni

2.3.3.2. Sequential Impregnation of Mo and Ni

2.3.4. Effect of Calcination Temperature

2.3.5. The Effect of Sulfiding the Catalyst

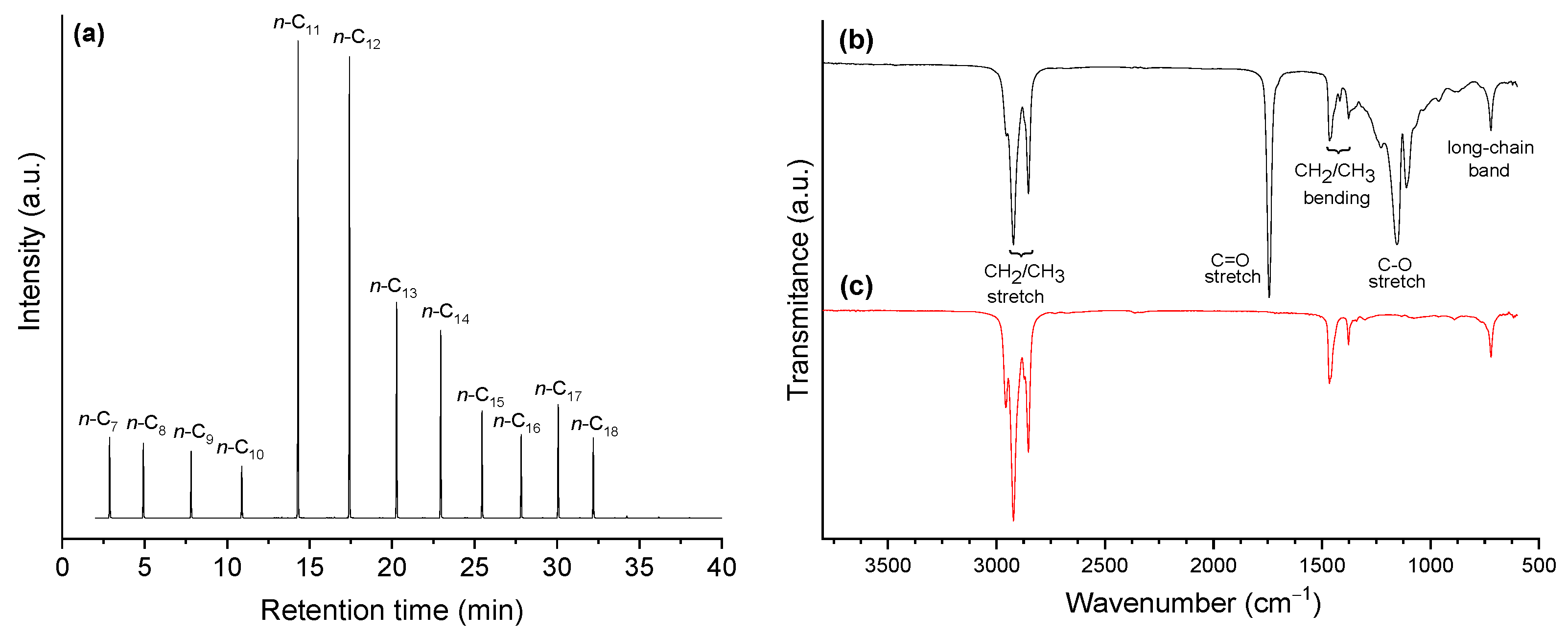

2.4. HDO Tests with Coconut Oil

2.5. Catalyst reusability

2.6. Comparison with a Reference Sulfided NiMo/Al2O3 Catalyst

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Catalysts Preparation

3.2. Catalysts Labels

3.3. Characterization of P54 and Catalysts

3.4. HDO Tests

3.5. Characterization of the Liquid Reaction Products

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | Activated carbon |

| ATR | Attenuated total reflection |

| BE | Binding energy |

| BET | Brunauer, Emmett e Teller |

| DR | Dubinin-Radushkevitch |

| EDX | Energy-dispersive X-ray |

| FEG | Field emission gun |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| HAADF | High-angle annular dark-field |

| HDO | Hydrodeoxygenation |

| HEFA | Hydroprocessing of esters and fatty acids |

| HR | High-resolution |

| HRTEM | High-resolution transmission electron microscopy |

| HVO | Hydrotreated vegetable oil |

| ICP | Inductively coupled plasma |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| JCPDS | Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| OES | Optical emission spectrometry |

| SAF | Sustainable aviation fuel |

| SPK | Synthetic paraffinic kerosene |

| SSA | Specific surface area |

| STEM | Scanning transmission electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| TPD | Temperature-programmed desorption |

| Vmic | Micropores volume |

| Vmes | Mesopores volume |

| XPS | X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Fregolente, P.B.L.; Maciel, M.R.W.; Oliveira, L.S. Removal of water content from biodiesel and diesel fuel using hydrogel adsorbents. Braz J Chem Eng 2015, 32, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregolente, P. B. L.; Wolf Maciel, W. M.; Oliveira, L. S. Removal of Water Content From Biodiesel and Diesel Fuel Using Hydrogel Adsorbents. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, G.; Sharma, M. Cold Flow Behaviour of Biodiesel-A Review. Int. J. Ren. Energy Res. 2013, 3, 827–836. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, R. Ap.; Oliveira, V. da S.; Scabio, A. Oxidative Stability of Biodiesel from Soybean Oil Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters. Sci. Agric. 2005, 62, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Prauchner, M.; D. Brandão, R.; M. de Freitas Júnior, A.; da C. Oliveira, S. Alternative Hydrocarbon Fuels, with Emphasis on Sustainable Jet Fuels. Revista Virtual de Química 2023, 15, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Renewable Bio-Jet Fuel Production for Aviation: A Review. Fuel 2019, 254, 115599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xin, Z.; He, Q. (Sophia); Corscadden, K.; Niu, H. An Overview on Performance Characteristics of Bio-Jet Fuels. Fuel 2019, 237, 916–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M. J.; Machado, P. G.; da Silva, A. V.; Saltar, Y.; Ribeiro, C. O.; Nascimento, C. A. O.; Dowling, A. W. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Technologies, Costs, Emissions, Policies, and Markets: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L. S.; Pereira, M. F. R. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Production through Catalytic Processing of Lignocellulosic Biomass Residues: A Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pérez, M. A.; Serrano-Ruiz, J. C. Catalytic Production of Jet Fuels from Biomass. Molecules 2020, 25, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. A.; Alves, C. T.; Onwudili, J. A. A Review of Current and Emerging Production Technologies for Biomass-Derived Sustainable Aviation Fuels. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amhamed, A. I.; Assaf, A. H. Al; Le Page, L. M.; Alrebei, O. F. Alternative Sustainable Aviation Fuel and Energy (SAFE)- A Review with Selected Simulation Cases of Study. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 3317–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Ma, L. Hydroprocessing of Lipids: An Effective Production Process for Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Energy 2023, 283, 129107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R. R. C.; dos Santos, I. A.; Arcanjo, M. R. A.; Cavalcante, C. L.; de Luna, F. M. T.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; Vieira, R. S. Production of Jet Biofuels by Catalytic Hydroprocessing of Esters and Fatty Acids: A Review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. K.; Han, J. Y.; Lee, H.; Yum, T.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J. Production of Renewable Diesel via Catalytic Deoxygenation of Natural Triglycerides: Comprehensive Understanding of Reaction Intermediates and Hydrocarbons. Appl Energy 2014, 116, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J. E.; Mohamed, A. R.; Kay Lup, A. N.; Koh, M. K. Palm Fatty Acid Distillate Derived Biofuels via Deoxygenation: Properties, Catalysts and Processes. Fuel Proc. Techn. 2022, 236, 107394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.; Kandaramath Hari, T.; Yaakob, Z.; Chandra Sharma, Y.; Sopian, K. Overview on the Production of Paraffin Based-Biofuels via Catalytic Hydrodeoxygenation. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2013, 22, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Parlett, C. M. A.; Fan, X. Recent Developments in Multifunctional Catalysts for Fatty Acid Hydrodeoxygenation as a Route towards Biofuels. Molecular Catalysis 2022, 523, 111492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Z.; Santoso, L.; McCue, A.; Azua Jamari, N. L.; Ninglasari, S. Y.; Gunawan, T.; Fansuri, H. Selectivity of Reaction Pathways for Green Diesel Production towards Biojet Fuel Applications. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 13698–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Kay Lup, A. N.; Qureshi, K. M.; Abnisa, F.; Wan Daud, W. M. A.; Patah, M. F. A. A Review on Deoxygenation of Triglycerides for Jet Fuel Range Hydrocarbons. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 140, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, G.; Miao, C. Green and Renewable Bio-Diesel Produce from Oil Hydrodeoxygenation: Strategies for Catalyst Development and Mechanism. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2019, 101, 568–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H. I.; Bazargan, A.; McKay, G.; Azelee, N. I. W.; Meili, L. Catalytic Deoxygenation of Palm Oil and Its Residue in Green Diesel Production: A Current Technological Review. Chem. Eng. Res. Design 2021, 174, 158–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, N.-S.; Toshtay, K.; Capron, M. Catalytic Applications in the Production of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) as a Renewable Fuel: A Review. Catalysts 2024, 14, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, B. P.; Misra, R. D. Effect of Reaction Pathway and Operating Parameters on the Deoxygenation of Vegetable Oils to Produce Diesel Range Hydrocarbon Fuels: A Review. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2017, 73, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, N.; Sharma, R. V.; Dalai, A. K. Green Diesel Synthesis by Hydrodeoxygenation of Bio-Based Feedstocks: Strategies for Catalyst Design and Development. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2015, 48, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki-Arvela, P.; Martínez-Klimov, M.; Murzin, D. Yu. Hydroconversion of Fatty Acids and Vegetable Oils for Production of Jet Fuels. Fuel 2021, 306, 121673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K. W.; Yusup, S.; Loy, A. C. M.; How, B. S.; Skoulou, V.; Taylor, M. J. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Deoxygenation of Plant Oils and Prototypical Fatty Acid Models Compounds: Catalysis, Process, and Kinetics. Molecular Catalysis 2022, 523, 111469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, L.; Cheng, S.; Julson, J. Review of Heterogeneous Catalysts for Catalytically Upgrading Vegetable Oils into Hydrocarbon Biofuels. Catalysts 2017, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselink, R. W.; Hollak, S. A. W.; Chang, S.; van Haveren, J.; de Jong, K. P.; Bitter, J. H.; van Es, D. S. Reaction Pathways for the Deoxygenation of Vegetable Oils and Related Model Compounds. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 1576–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, X. Y.; Gao, W.; Ong, H. C.; Lee, H. V.; Juan, J. C.; Chen, W. H.; Lee, K. T. Overview on Catalytic Deoxygenation for Biofuel Synthesis Using Metal Oxide Supported Catalysts. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2019, 112, 834–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R. K.; Jaya Prasanna Kumar, D.; Sankannavar, R.; Binnal, P.; Mohanty, K. Hydro-Deoxygenation of Pyrolytic Oil Derived from Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass: A Review. Fuel 2024, 360, 130473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel, S. B.; Donar, Y. O.; Ergenekon, S.; Özoylumlu, B.; Sinağ, A. Green Catalyst for Clean Fuel Production via Hydrodeoxygenation. Turk. J. Chem. 2023, 47, 968–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Getahun, T.; Verma, M.; Villa, A.; Gupta, N. Carbon Based Catalysts for the Hydrodeoxygenation of Lignin and Related Molecules: A Powerful Tool for the Generation of Non-Petroleum Chemical Products Including Hydrocarbons. Ren. Sust. Energy Reviews 2020, 133, 110280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itthibenchapong, V.; Srifa, A.; Kaewmeesri, R.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Faungnawakij, K. Deoxygenation of Palm Kernel Oil to Jet Fuel-like Hydrocarbons Using Ni-MoS 2 / γ -Al 2 O 3 Catalysts. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017, 134, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Rogers, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, G.; Pu, J.; Zheng, H.; Lin, H.; Zheng, Y.; Ng, S. The Effects of Catalyst Support and Temperature on the Hydrotreating of Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) over CoMo Sulfided Catalysts. Catalysts 2019, 9, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão, R. D.; de Freitas Júnior, A. M.; Oliveira, S. C.; Suarez, P. A. Z.; Prauchner, M. J. The Conversion of Coconut Oil into Hydrocarbons within the Chain Length Range of Jet Fuel. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2021, 11, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.-J.; Lee, J. B.; Kim, Y.-J.; Cho, H.-R.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, G.-E.; Park, Y.-D.; Kim, G.-H.; An, J.-C.; Oh, K.; Park, J.-I. The Characteristics of Hydrodeoxygenation of Biomass Pyrolysis Oil over Alumina-Supported NiMo Catalysts. Catalysts 2024, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eller, Z.; Varga, Z.; Hancsók, J. Renewable Jet Fuel from Kerosene/Coconut Oil Mixtures with Catalytic Hydrogenation. Energy & Fuels 2019, 33, 6444–6453. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, V.; Mishra, A.; Anand, M.; Farooqui, S. A.; Sinha, A. K. Catalytic Hydroprocessing of Waste Cooking Oil for the Production of Drop-in Aviation Fuel and Optimization for Improving Jet Biofuel Quality in a Fixed Bed Reactor. Fuel 2023, 333, 126348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenol, O. İ.; Viljava, T.-R.; Krause, A. O. I. Hydrodeoxygenation of Aliphatic Esters on Sulphided NiMo/γ-Al2O3 and CoMo/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst: The Effect of Water. Catalysis Today 2005, 106, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluža, L.; Soukup, K.; Koštejn, M.; Karban, J.; Palcheva, R.; Laube, M.; Gulková, D. On Stability of High-Surface-Area Al2O3, TiO2, SiO2-Al2O3, and Activated Carbon Supports during Preparation of NiMo Sulfide Catalysts for Parallel Deoxygenation of Octanoic Acid and Hydrodesulfurization of 1-Benzothiophene. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bara, C.; Lamic-Humblot, A.-F.; Fonda, E.; Gay, A.-S.; Taleb, A.-L.; Devers, E.; Digne, M.; Pirngruber, G. D.; Carrier, X. Surface-Dependent Sulfidation and Orientation of MoS2 Slabs on Alumina-Supported Model Hydrodesulfurization Catalysts. J. Catal. 2016, 344, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsøe, H. The Role of Co–Mo–S Type Structures in Hydrotreating Catalysts. Appl. Catal. A Gen 2007, 322, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuxen, A.; Gøbel, H.; Hinnemann, B.; Li, Z.; Knudsen, K. G.; Topsøe, H.; Lauritsen, J. V.; Besenbacher, F. An Atomic-Scale Investigation of Carbon in MoS2 Hydrotreating Catalysts Sulfided by Organosulfur Compounds. J. Catal. 2011, 281, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, E.; Delmon, B. Influence of Water in the Deactivation of a Sulfided Catalyst during Hydrodeoxygenation. J. Catal. 1994, 146, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Wei, L.; Zhao, X.; Julson, J. Application, Deactivation, and Regeneration of Heterogeneous Catalysts in Bio-Oil Upgrading. Catalysts 2016, 6, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, X. Hydrodeoxygenation of Model Compounds and Catalytic Systems for Pyrolysis Bio-Oils Upgrading. Catal. Sust. Energy 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordouli, E.; Kordulis, Ch.; Lycourghiotis, A.; Cole, R.; Vasudevan, P. T.; Pawelec, B.; Fierro, J. L. G. HDO Activity of Carbon-Supported Rh, Ni and Mo-Ni Catalysts. Molecular Catalysis 2017, 441, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahene, W. L.; Kivevele, T.; Machunda, R. The Role of Textural Properties and Surface Chemistry of Activated Carbon Support in Catalytic Deoxygenation of Triglycerides into Renewable Diesel. Catal. Commun. 2023, 181, 106737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coumans, A. E.; Hensen, E. J. M. A Real Support Effect on the Hydrodeoxygenation of Methyl Oleate by Sulfided NiMo Catalysts. Catal. Today 2017, 298, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Puente, G.; Gil, A.; Pis, J. J.; Grange, P. Effects of Support Surface Chemistry in Hydrodeoxygenation Reactions over CoMo/Activated Carbon Sulfided Catalysts. Langmuir 1999, 15, 5800–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Hu, A.; Qiu, L.; Wang, W.; Xiang, Y.; Han, W.; Xu, G.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, A. Insight into the Microstructure and Deactivation Effects on Commercial NiMo/γ-Al2O3 Catalyst through Aberration-Corrected Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy. Catalysts 2019, 9, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G. Acid Catalysts in Industrial Hydrocarbon Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 5366–5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauchner, M. J.; Sapag, K.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Tailoring Biomass-Based Activated Carbon for CH4 Storage by Combining Chemical Activation with H3PO4 or ZnCl2 and Physical Activation with CO2. Carbon N Y 2016, 110, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauchner, M. J.; Oliveira, S. da C.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Tailoring Low-Cost Granular Activated Carbons Intended for CO2 Adsorption. Front Chem 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S. C.; Dutra, R. C.; León, J. J. L.; Martins, G. A. V.; Silva, A. M. A.; Azevedo, D. C. S.; Santiago, R. G.; Ballesteros Plata, D.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Prauchner, M. J. Activated Carbon Ammonization: Effects of the Chemical Composition of the Starting Material and the Treatment Temperature. C 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, J. A. R.; Gerkema, E.; van der Kraan, A. M.; Knoester, A. A Real Support Effect on the Activity of Fully Sulphided CoMoS for the Hydrodesulphurization of Thiophene. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1987, 22, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topsøe, H.; Clausen, B. S. Active Sites and Support Effects in Hydrodesulfurization Catalysts. Appl. Catal. 1986, 25, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugulan, A. I.; van Veen, J. A. R.; Hensen, E. J. M. On the Structure and Hydrotreating Performance of Carbon-Supported CoMo- and NiMo-Sulfides. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 142–143, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAN, Z.; XIAO, H.; ZHANG, R.; ZHANG, Z.-S.; Kaliaguine, S. Potential to Use Mesoporous Carbon as Catalyst Support for Hydrodesulfurization. New Carbon Materials 2009, 24, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, N.; Badoga, S.; Soni, K. K.; Dalai, A. K.; Adjaye, J. Hydrotreating of Light Gas Oil Using a NiMo Catalyst Supported on Activated Carbon Produced from Fluid Petroleum Coke. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2014, 8, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzu, M.; Kuriki, Y.; Hamdy, F.; Sakanishi, K.; Sugimoto, Y.; Saito, I. Catalytic Potential of Carbon-Supported NiMo-Sulfide for Ultra-Deep Hydrodesulfurization of Diesel Fuel. Appl. Catal. A. 2004, 265, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukundan, S.; Konarova, M.; Atanda, L.; Ma, Q.; Beltramini, J. Guaiacol Hydrodeoxygenation Reaction Catalyzed by Highly Dispersed, Single Layered MoS2/C. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 4422–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, V.; Buitrago, R.; Lopez, D. P. HDO Del Guaiacol Mediante El Uso de Catalizadores NiMo Soportados Sobre Carbón Activado Obtenido a Partir de La Torta de Higuerilla. Ingeniería e Investigación 2015, 35, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, J.; Acelas, N. Y.; López, D.; Moreno, A. NiMo-Sulfide Supported on Activated Carbon to Produce Renewable Diesel. Univ. Sci. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, K. K.; Ribeiro, L. S.; Pereira, M. F. R. Analysis of Reaction Conditions in Palmitic Acid Deoxygenation for Fuel Production. Catalysts 2024, 14, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauchner, M. J.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Chemical versus Physical Activation of Coconut Shell: A Comparative Study. Microp. Mesop. Mat. 2012, 152, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M. C. Accessing the Robustness of Adventitious Carbon for Charge Referencing (Correction) Purposes in XPS Analysis: Insights from a Multi-User Facility Data Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Ozaki, J. Understanding the Chemical Structure of Carbon Edge Sites by Using Deuterium-Labeled Temperature-Programmed Desorption Technique. Carbon N Y 2020, 161, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düngen, P.; Schlögl, R.; Heumann, S. Non-Linear Thermogravimetric Mass Spectrometry of Carbon Materials Providing Direct Speciation Separation of Oxygen Functional Groups. Carbon N Y 2018, 130, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnasamy, R.; Thangamuthu, R.; Alagan, V. Sheet-like Orthorhombic MoO3 Nanostructures Prepared via Hydrothermal Approach for Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Application. Res. Chem. Interm. 2018, 44, 1647–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, U.; Kumar, S.; Bahnemann, D.; Koch, J.; Tegenkamp, C.; Muneer, M. Harvesting Visible Light with MoO3 Nanorods Modified by Fe(iii) Nanoclusters for Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2018, 20, 4538–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Niehoff, P.; He, X.; Paillard, E.; Eder, D.; Winter, M.; Li, J. Hierarchical Ternary MoO2/MoS2/Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Hybrid Materials for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Storage. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego-Benitez, J. E.; Mendoza-Cruz, R.; Bazán-Díaz, L.; Garcia-Garcia, A.; Arellano-Jimenez, M. J.; Perez-Robles, J. F.; Plascencia-Villa, G.; Velázquez-Salazar, J. J.; Ortega, E.; Favela-Camacho, S. E.; José-Yacamán, M. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of MoS2 Micropyramids. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 12203–12213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ke, Y.; Wang, T.; Cai, J.; Huang, Q.; Lin, S. Green Synthesis of Flowerball-like MoS2/VC Nanocomposite and Its Efficient Catalytic Performance for Oxygen Reduction Either in Alkaline or Acid Media. Catalysts 2022, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 76 Basha, I. K.; Abd El-Monaem, E. M.; Khalifa, R. E.; Omer, A. M.; Eltaweil, A. S. Sulfonated Graphene Oxide Impregnated Cellulose Acetate Floated Beads for Adsorption of Methylene Blue Dye: Optimization Using Response Surface Methodology. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cant, D. J. H.; Syres, K. L.; Lunt, P. J. B.; Radtke, H.; Treacy, J.; Thomas, P. J.; Lewis, E. A.; Haigh, S. J.; O’Brien, P.; Schulte, K.; Bondino, F.; Magnano, E.; Flavell, W. R. Surface Properties of Nanocrystalline PbS Films Deposited at the Water–Oil Interface: A Study of Atmospheric Aging. Langmuir 2015, 31, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C. A. A.; Silva, C. F.; Matos, J. M. E. Síntese, Caracterização e Aplicação Do Trióxido de Molibdênio Na Fotocatálise de Efluente Têxtil Sintético. Cerâmica 2018, 64, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Silva Lucena de Medeiros, S.; Flávia Félix Farias, A.; Maria Garcia dos Santos, I. Synthesis of Molybdenum Trioxide with Different Structures and Microstructures by the Modified Pechini Method: A New Methodological Approach. Revista Virtual de Química 2021, 13, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byskov, L. S.; Hammer, B.; Nørskov, J. K.; Clausen, B. S.; Topsøe, H. Sulfur Bonding in MoS2 and Co-Mo-S Structures. Catal. Letters 1997, 47, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Y.; Richard, F.; Brunet, S. Hydrodeoxygenation of 2-Ethylphenol as a Model Compound of Bio-Crude over Sulfided Mo-Based Catalysts: Promoting Effect and Reaction Mechanism. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 98, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, J. Prauchner, Ruana D. Brandão, Antônio M. de Freitas Júnior, Silvia da C. Oliveira. Combustíveis Derivados do Petróleo: Obtenção, Propriedades e Usos. Revista Virtual de Química. 2023, 15, 43–60 [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar]

- Lokesh, K.; Sethi, V.; Nikolaidis, T.; Goodger, E.; Nalianda, D. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Analysis of Biojet Fuels with a Technical Investigation into Their Impact on Jet Engine Performance. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 77, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojagh, H.; Creaser, D.; Tamm, S.; Arora, P.; Nyström, S.; Lind Grennfelt, E.; Olsson, L. Effect of Dimethyl Disulfide on Activity of NiMo Based Catalysts Used in Hydrodeoxygenation of Oleic Acid. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 5547–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bykova, E. S.; Nadeina, K. A.; Vatutina, Y. V.; Chesalov, Y. A.; Pakharukova, V. P.; Larina, T. V.; Prosvirin, I. P.; Gerasimov, E. Y.; Klimov, O. V.; Noskov, A. S. The Impact of the Water Phase in the Gasoil Fraction on the CoMo Hydrotreating Catalyst’s Performance. Fuel 2024, 365, 131229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Shinozaki, A.; Shi, M.; Qian, E. W. Hydrotreating of Jatropha Oil over Alumina Based Catalysts. Energy & Fuels 2012, 26, 2394–2399. [Google Scholar]

- Kubička, D.; Horáček, J. Deactivation of HDS Catalysts in Deoxygenation of Vegetable Oils. Appl. Catal. A 2011, 394, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezergianni, S.; Dimitriadis, A.; Kalogianni, A.; Pilavachi, P. A. Hydrotreating of Waste Cooking Oil for Biodiesel Production. Part I: Effect of Temperature on Product Yields and Heteroatom Removal. Bior. Tech. 2010, 101, 6651–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žula, M.; Grilc, M.; Likozar, B. Hydrocracking, Hydrogenation and Hydro-Deoxygenation of Fatty Acids, Esters and Glycerides: Mechanisms, Kinetics and Transport Phenomena. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444, 136564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R. P.; Pereira, M. F. R.; Figueiredo, J. L. Characterisation of the Surface Chemistry of Carbon Materials by Temperature-Programmed Desorption: An Assessment. Catalysis Today 2023, 418, 114136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, H. P. Surface Oxides on Carbon and Their Analysis: A Critical Assessment. Carbon N Y 2002, 40, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, X. Application of Boehm Titration for the Quantitative Measurement of Soot Oxygen Functional Groups. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, 7363–7372. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, Z.; Kaixuan, F.; Pingping, W.; Yue, Z.; Yongke, Z. Enhancement of the Adsorption of Bilirubin on Activated Carbon via Modification. Results in Materials 2021, 9, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, J.; Buchheim, J. R.; Scholz, P.; Adelhelm, P. Boehm Titration Revisited (Part II): A Comparison of Boehm Titration with Other Analytical Techniques on the Quantification of Oxygen-Containing Surface Groups for a Variety of Carbon Materials. C 2018, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | SBET (m2 g–1) | Vmic (cm3 g–1) | Vmes (cm3 g–1) | V0.95 (cm3 g–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P54 | 1643 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 1.17 |

| oxo-Mo/P54-i,4 | 516 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.33 |

| oxo-Mo/P54-i,5 | 562 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.37 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-i,4 | 862 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.58 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-i,5 | 830 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.55 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-w,4 | 812 | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.54 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-w,5 | 725 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.48 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-i,4 | 636 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.41 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-i,5 | 535 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.35 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | 655 | 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.42 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-w,5 | 573 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| Sample | Content (wt%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | N | P | S | Si | Mo | Ni | ||

| P54 | 85.9 | 11.9 | - | 1.9 | - | 0.4 | - | - | |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-i,4 | 71.3 | 19.9 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 5.6 | 0.7 | ||

| oxo-NiMo/P54-w,4 | 70.2 | 14.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 12.4 | 1.0 | ||

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | 56.3 | 18.3 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 21.7 | 1.0 | ||

| sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | 29.1 | 17.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 24.0 | 27.7 | 1.0 | ||

| Relative contributions (wt%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | CII | CIII | CIV | OI | OII |

| 85.1 (73.1) | 9.0 (7.7) | 4.0 (3.5) | 1.9 (1.6) | 44.8 (5.3) | 55.19 (6.6) |

| Ash Content (wt%) |

Elemental Analysis | Titration (mmol g–1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acidity | Basicity | ||||||||

| C (wt%) | H (wt%) | N (wt%) | 1H/C | Strong | Medium | Weak | Total | Total | |

| 1.2 | 84.2 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.07 | 1.21 | 1.83 | 0.00 |

| Catalyst | Mo (wt%) | Ni (wt%) | 1 Ni/Mo |

|---|---|---|---|

| oxo-Mo/P54-i,4 | 15.1 | - | - |

| oxo-Mo/P54-i,5 | 18.3 | - | - |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-i,4 | 20.4 | 0.91 | 0.07 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-i,5 | 17.5 | 1.02 | 0.10 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-w,4 | 20.5 | 0.89 | 0.07 |

| oxo-NiMo/P54-w,5 | 15.9 | 0.91 | 0.09 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-i,4 | 16.9 | 0.70 | 0.07 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-i,5 | 15.6 | 1.00 | 0.10 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | 19.5 | 0.88 | 0.07 |

| oxo-Ni,Mo/P54-w,5 | 12.6 | 0.93 | 0.12 |

| Entry | Catalyst | Feedostock | Reaction time (h) |

AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P54 | Lauric acid | 3 | 264.4 |

| 2 | sulf-Mo/P54-i,4 | Lauric acid | 3 | 8.1 |

| 3 | Sulf-Mo/P54-i,5 | Lauric acid | 3 | 7.0 |

| 4 | sulf-NiMo/P54-i,4 | Lauric acid | 3 | 8.6 |

| 5 | sulf-NiMo/P54-i,5 | Lauric acid | 3 | 7.2 |

| 6 | sulf-NiMo/P54-w,4 | Lauric acid | 3 | 0.8 |

| 7 | sulf-NiMo/P54-w,5 | Lauric acid | 3 | 1.1 |

| 8 | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-i,4 | Lauric acid | 3 | 2.0 |

| 9 | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-i,5 | Lauric acid | 3 | 0.8 |

| 9’ | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-i,5 | Lauric acid | 2 | 13.7 |

| 10 | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | Lauric acid | 3 | 0.5 |

| 10’ | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | Lauric acid | 2 | 1.9 |

| 11 | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,5 | Lauric acid | 3 | 0.8 |

| 12 | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | Coconut oil | 3 | 1.1 |

| 12’ | sulf-Ni,Mo/P54-w,4 | Coconut oil | 5 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).