1. Introduction

Plasma membranes, the defining feature of cellular life, serve as the critical interface between the cell and its environment. These complex structures, composed primarily of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, not only provide a physical barrier that delineates the cell but also play a pivotal role in numerous cellular processes. They regulate the transport of substances in and out of the cell, facilitate cell-to-cell communication, and provide a platform for biochemical reactions [

1]. Within this intricate membrane landscape, certain protein families have adapted to interact specifically with the lipid components of the membrane, mediating crucial functions of the cell. One such protein family is annexins [

2].

Annexins constitute a protein family found in almost every eukaryote investigated to date, including animals, plants, and fungi. Annexins are known for two main properties: the ability to bind negatively charged phospholipids, and to complex with calcium ions. In the annexin structure, we can specify the disordered head region and the conserved core region containing a 70 amino acid repeat sequence known as the annexin repeat or fold [

2,

3,

4]. Interestingly, annexin homologs have recently also been discovered in bacteria [

5], expanding our understanding of the distribution of these proteins beyond eukaryotes. This discovery suggests that annexins may play a more universal role in cellular processes than previously thought.

The basic functions of annexins revolve around their interaction with membranes and calcium ions [

4,

6]. They are involved in various processes such as forming structures on lipid membranes that can work as anchoring points [

7], which is relevant to changes in cell morphology. Annexins were also shown to be involved in the trafficking and organization of vesicles [

8,

9], and potentially in calcium ion channel formation [

10,

11,

12,

13] and unconventional protein secretion (UPS) [

14,

15].

The impact of annexins on phenotype and disease states, particularly cancer, is a growing area of research. High annexin-A1 expression levels correlate with poor prognosis for survival in various cancers with limited treatment options, including triple-negative breast, pancreatic, colorectal, and prostate cancers [

16]. This highlights the importance of annexins in our understanding of cellular processes and their potential as therapeutic targets [

17,

18,

19].

The existing literature on annexin orthologues across the Eukaryotic tree of life is vast. For this reason, in this review, we refer primarily to the current state of research on the annexin protein family spanning several Eukaryotic taxa. The focus of this study is on membrane interactions – modes of interaction, possible structures formed on or at the membrane and further functional implications resulting from those interactions.

2. Annexins: The Basics

Annexins were initially referred to as synexins [

20], a term derived from the ability of annexin A7 to facilitate the fusion of lipid membranes [

21]. As time progressed, various annexins were identified and named differently. For example, annexin A1 was known as lipocortin [

22,

23], and annexin A2 was referred to as calpactin [

24,

25]. Eventually, the term ‘annexin’ was introduced to denote the superfamily, and this nomenclature is now established. However, inconsistencies in naming conventions persist in literature, particularly for abbreviations. To maintain consistency in this review, we will adhere to the official nomenclature previously proposed [

3]. The abbreviation ‘Anx’ will be used for ‘annexin’, followed by a letter indicating the origin: ‘A’ for vertebrates, ‘B’ for invertebrates, ‘C’ for fungi, ‘D’ for plants, and ‘E’ for protists.

Annexin structure can be coarsely separated into the N-terminal head and the C-terminal core region [

2,

3,

26]. The N-terminal region in most cases, is disordered (mostly based on

in silico structural predictions). It can determine annexins’ ability to interact with other proteins or lipids which translate into its regulatory functions. The core region is structurally conserved across all annexins and is built of four to ten repeats, consisting of five alpha-helixes, four of which are parallel to each other and one perpendicular to them. These repeats form a curved rhombic shape with concave and convex sides. The convex side is identified by two characteristic properties of annexins: interaction with Ca

2+ and lipids [

2,

27]. On the other hand, the concave side takes part in interaction with the N-terminal and protein complex formation [

2,

3].

Annexin calcium-dependent membrane binding properties are characterized by two types of interactions. Primary binding is defined as a calcium-mediated electrostatic interaction with phospholipid polar heads [

27]. On the other hand, secondary binding is based on hydrophobic interactions [

27]. The specific mechanism of membrane binding varies among different annexins and is influenced by factors such as membrane lipid composition, presence of Ca

2+ ions and pH [

2,

4,

28,

29]. Annexins can form various structures on the surface of a membrane, ranging from simple aggregates to complex networks, depending on the specific annexin and the conditions of the membrane [

7,

30,

31]. These structures are speculated to contribute to the ability of annexins to regulate membrane dynamics and to participate in various cellular processes.

Following membrane binding, annexins can insert themselves into the membrane. This process is thought to involve a conformational change in annexin structure, allowing penetration of the lipid bilayer [

2,

13,

32]. The exact mechanism of membrane insertion is still a subject of ongoing research, but is considered to play a crucial role in annexin function and subcellular location.

3. Annexin-Membrane Interactions: Modes and Functions

3.1. Annexins and Membrane Repair

3.1.1. Mammalian Cell Systems

One of the most important membrane-related functions of annexins is membrane integrity and continuity. Among the annexins described in mammalian cells, AnxA1 and AnxA5 are primarily responsible for membrane repair [

33,

34]. AnxA1, in particular, has been identified as crucial in membrane wound healing. This cytosolic protein, when activated by micromolar Ca

2+, binds to membrane phospholipids, thereby promoting membrane aggregation and fusion. It has been demonstrated that the resealing process can be inhibited by an AnxA1 function-blocking antibody, a small peptide competitor, and a dominant-negative AnxA1 mutant protein incapable of Ca

2+ binding [

34]. Furthermore, it has been observed that AnxA1 becomes concentrated at disruption sites marked by a resealing event. This evidence underscores the significant role for annexin, particularly AnxA1, in membrane repair and wound healing [

34].

In addition to the role of AnxA1, AnxA5 has also been shown to promote membrane repair. AnxA5 is a protein that self-assembles into two-dimensional arrays on membranes upon Ca

2+ activation. Compared to wild-type mouse perivascular cells, AnxA5-null cells exhibit a severe membrane repair defect. This defect can be rescued by the addition of AnxA5, which binds exclusively to disrupted membrane areas. Interestingly, an AnxA5 mutant that lacks the ability to form 2D arrays is unable to promote membrane repair. This suggests that the formation of 2D arrays by AnxA5 is a critical step in the membrane repair process. It is proposed that, triggered by the local influx of Ca

2+, AnxA5 proteins bind to torn membrane edges and form a 2D array, thus promoting membrane resealing. This discovery introduces a previously unrecognized step in the membrane repair process, further highlighting the significant roles of annexins, particularly AnxA1 and AnxA5, in membrane repair and wound healing [

33].

3.1.2. Plant Cell Systems

In the context of plants, a study on Arabidopsis AnxD5 has shed light on its role in maintaining pollen cell membrane integrity. AnxD5, the most abundant member of the annexin family in pollen, was observed to have a transient association with the pollen membrane during

in vitro hydration. When the pollinated stigma was sprayed with deionized water to simulate rainfall, AnxD5 accumulated at the pollen membrane. This suggests that AnxD5 is involved in restoring pollen membrane integrity under stress conditions. Furthermore, treatments with calcium or magnesium, which caused rupture or shrinkage of the pollen, also induced AnxD5 recruitment to the pollen membrane [

35]. These findings support the model that plant annexins, like their metazoan counterparts, are involved in the maintenance of membrane integrity.

3.1.3. Other Cell Systems

There is limited information available on annexins from different kingdoms. In the context of the fungus

Cryptococcus neoformans, no alterations resulting from the deletion of AnxC1 could be observed [

36]. Conversely, in Dictyostelium, the response to membrane damage was found to be slower following the deletion of annexins AnxC1 and AnxC2 [

37].

3.2. Annexins as Calcium Ion Channels

3.2.1. Mammalian Cell Systems

One of the initial proposed roles of annexins was mediating calcium ion transport through the lipid membrane, an observation based on conductance studies on recombinant human AnxA5 containing a mutation of Glu95 to Ser (E95S). These studies were performed using artificial liposomes containing Phosphatidylserine (PS). The results of these studies were further substantiated by additional electrophysiological and structural investigations. The mutation E95S resulted in a lower single-channel conductance for calcium and a strongly increased conductance for sodium and potassium, indicating that Glu95 is a crucial constituent of the ion selectivity filter. Despite only minor differences in the crystal structures of mutant and wild-type AnxA5 around the mutation site, the mutant showed structural differences elsewhere, including the presence of a calcium-binding site in domain III unrelated to the mutation. Analysis of the membrane-bound form of AnxA5 by electron microscopy revealed no significant differences between the wild type and mutant, suggesting that the observed changes in ion conductance were primarily due to the specific mutation rather than overall structural alterations [

12].

3.2.2. Plant Cell Systems

Research around calcium ions transport was also conducted on plant annexins. A few examples of these annexins include ZmAnxD33/35 (Annexins 33 and 35 from

Zea mays) [

38], CaAnxD24 (Annexin 24 from

Capsicum annuum) [

39], MtAnxD1 (Annexin 1 from

Medicago truncatula) [

40], and AtAnxD1 (Annexin 1 from Arabidopsis) [

41]. These annexins can form calcium-permeable transport channels, regulate cytosolic calcium levels, and ZmAnxD33/35 can allow both extracellular calcium and potassium through when applied to the cytosolic side of a planar lipid bilayer. Interestingly, the conductance created by ZmAnxD33/35 was blocked by the cation channel blocker Gd

3+, indicating the creation of a trans-bilayer conductance. This conductance was found to be voltage-regulated and influenced by the presence of malondialdehyde, a substance produced in membranes during stress responses [

38]. Moreover, MtAnxD1 showed single-channel behavior, with varying single-channel conductance based on the amount of annexin present [

40]. This behavior mirrors that of animal annexins in lipid bilayers, thus highlighting the potential for these proteins in adjusting cellular responses to various stimuli and underscoring the necessity for additional research to fully comprehend their exact functions and roles in plant physiology.

3.2.3. The Debate Around Annexins as Ion Channels

Despite the data referenced above, the formation of channels by annexins remains a subject of debate [

42]. The key question is how a peripherally-associated membrane protein can facilitate the conduction of Ca

2+. Furthermore, there are inconsistencies between the diameter of the central pore and the observed conductance values.

Two main models present the mechanism of Ca

2+ transport by annexins. The first model, based on theoretical calculations, suggests that AnxA5 could disrupt the lipid organization in the bilayer at the site of Ca

2+-dependent attachment to such an extent that it effectively creates a pore in the membrane, thereby allowing Ca

2+ entry [

43]. The second model, which is backed by limited experimental data, is based on extensive mutagenesis of the Hydra AnxB12. Combined with spin-labeling experiments, structural analysis of AnxB12 mutants revealed that the protein undergoes a significant conformational change at a mildly acidic pH, accompanied by membrane insertion [

29]. Despite the thermodynamic implications of such a structural transformation, a hypothetically membrane-inserted annexin would possess seven transmembrane domains, thus adopting the structure of a more conventional channel.

3.3. Annexins and Protein Trafficking

3.3.1. Mammalian Cell Systems

As previously mentioned, the name annexin originates from its function to connect/bind together proteins or membranes [

2,

20]. Moreover, characteristic names for each annexin were coined based on the observed interaction [

2]; for example, lipocortin (AnxA1) binds steroid-inducible lipase inhibitors [

22,

23], calpactin (AnxA2) complexes Ca

2+, phospholipids and actin [

25], and synexin (AnxA7) interacts with chromatin granules [

21].

Annexins are reported to be responsible for tethering other molecules thereby promoting interactions and serving as regulatory units in cellular processes. For instance, AnxA1 acts as a bridge linking multivesicular bodies to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

44,

45]. The tyrosine-phosphorylated (pTyr) form of AnxA1 provides a docking site for tyrosine phosphatase 1B, which is located in the ER, enabling the interaction of this enzyme with the activated epidermal growth factor receptor located on the membrane of multivesicular bodies [

45]. Additionally, the same annexin via regulation of membrane interaction between the ER and multivesicular bodies is necessary to initiate the transport of cholesterol from the ER to endosomes [

44].

Annexin-related trafficking is not limited to membrane-membrane interaction. Both AnxA11 and potentially AnxA7 are involved with lysosomes and RNA granules as they are transported to the distal regions of the axon [

46]. Some annexins have been found to be responsible for the trafficking of foreign molecules in cells, such as AnxA2, which was found to organize the transport of synthetic antisense oligonucleotides from early to late endosomes [

8]. AnxA1 and AnxA2 have distinct roles in the retrograde trafficking of Shiga toxin to the

trans-Golgi network. Specifically, these proteins play a role in the uptake and intracellular transport of the bacterial Shiga toxin and the plant toxin ricin [

9].

3.3.2. Plant Cell Systems

The impact of annexins on trafficking and interaction with the membrane was noted in a study where researchers employed Brefeldin A, a compound known for its ability to disrupt endomembrane trafficking, which in turn inhibits pollen germination [

47]. AnxD5 was revealed as a putative “linker” between Ca

2+ signaling, the actin cytoskeleton, and the membrane. These elements are all essential for pollen development and pollen tube growth. The study further demonstrated that AnxD5 is associated with the phospholipid membrane, and it is stimulated by Ca

2+ in vitro. Interestingly, pollen germination and pollen tube growth of plants overexpressing AnxD5 showed increased resistance to Brefeldin A treatment, and this effect was also regulated by calcium ions. This suggests that AnxD5 promotes endomembrane trafficking modulated by calcium, thereby playing a vital role in angiosperm pollen development, germination, and pollen tube growth.

3.3.3. Other Cell Systems

Information about specific functions in organisms other than plants and mammals remains limited. One example is annexin from the slime mold

Physarum polycephalum [

48]. In a study by T. Shirakawa et al., it was demonstrated that

P. polycephalum annexin can bind to two different classes of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases [

48]. The authors speculate that this interaction may impact the protein translation machinery and could also be involved in membrane fusion or other dynamic membrane processes. Impact on trafficking was also observed in

Caenorhabditis elegans deletion mutants for AnxB1 (nex-1) [

49], including disruption of apoptotic cell engulfment [

49].

3.4. Membrane Traversal

Annexins are a versatile family of proteins that are postulated to regulate a variety of cellular processes. These range from the regulation of protein activity [

50], to the control of polysaccharide synthesis [

51]. However, one property of annexins related to membranes merits mention – unconventional protein secretion (UPS) [

15]. In contrast to conventional secretion, where proteins with a signal peptide are directed to the ER, then to the Golgi apparatus and are either secreted or transported to other secretory compartments, UPS is the secretion of proteins without a signal peptide or any other feature associated to canonical secretion, with the entire process circumventing the Golgi apparatus. The absence of a specific secretory sequence significantly complicates the detection and investigation of this phenomenon.

Annexins have been reported as UPS substrates. However, the exact mechanism of how annexins are secreted remains unclear and is the subject of ongoing research, mostly on AnxA1. One hypothesis involves transporters as mediators of annexin UPS. AnxA1 was reported to be transported from the cytosol across the plasma membrane into the extracellular space by type II secretion mediated by an ATP binding cassette (ABC)-transporter [

52]. These ATP-dependent membrane transporters are known to transport a variety of cargo, including ions, heavy metals, amino acids, and sugars [

53]. Furthermore, some bacterial ABC transporters are known to secrete larger molecules, including proteins, suggesting the possibility that ABC transporters may also be responsible for the secretion of leaderless proteins in mammalian cells. However, the evidence supporting this hypothesis is indirect and somewhat limited. For instance, one study found that glucocorticoid-stimulated AnxA1 externalization in pituitary folliculo-stellate cells was inhibited by glyburide, an ABC transporter inhibitor. This lent further support to a role for the ATP binding cassette A1 (ABCA1) transporter in the secretion of AnxA1 [

54]. Another study reported that AnxA1 secretion was inhibited by two ATPase inhibitors, vanadate and pervanadate [

55]. However, in this study, glyburide did not inhibit AnxA1 secretion, suggesting that the mechanism for AnxA1 secretion may differ depending on the stimulant and the cell line used. While these studies provide some evidence for the role of ABC transporters in AnxA1 secretion, there is no direct evidence to show that ABCA1 or any other ABC transporter is responsible for AnxA1 secretion.

An alternative hypothesis proposes a direct interaction between annexins and a target membrane, leading to either membrane disruption or annexin insertion/traversal in/of the membrane. This process is akin to the mechanism described in the subsection on ion channels, which ultimately results in transport across the membrane [

12,

38,

40]. In this scenario, UPS of annexins could come about as a result of oligomerization and structural changes, allowing for the transport of these proteins across the membrane without the need for a secretory signal peptide. However, it is important to note that this is still a hypothesis, and further research is needed to fully understand the mechanisms involved in the UPS of annexins and their potential interactions with the membrane. This area of study holds significant promise for enhancing our understanding of protein secretion and cellular processes, especially in the context of annexin function in tissue and cellular homeostasis.

Evidence supporting UPS of annexins in plants is scarce. However, there is a study that indirectly suggests the potential role of annexins in such processes [

56]. Fernandez et al. compared two potato cultivars with different resistance levels to the oomycete

Phytophthora infestans, and it was found that the resistant cultivar had a higher basal content of apoplastic hydrophobic proteins compared to the susceptible cultivar. Interestingly, annexin p34-like protein was one of the proteins that accumulated in both cultivars in response to

P. infestans infection. This suggests that annexin-like proteins could be part of the plant’s defense mechanism against pathogens. They might be involved in the secretion of resistance proteins into the apoplast, a process that could potentially be an example of UPS. However, more direct evidence is needed to confirm the role of annexins in this process.

Another example emerges from the world of protists. Annexins from the intestinal protist parasite

Giardia lamblia (

syn. intestinalis, duodenalis) were termed alpha-giardins before their status as annexin orthologues was determined [

57]. Some members of the 21-dtrong protein family were previously identified as putative UPS cargo, being found outside of the cell in the absence of any

bona fide signal sequence for secretion [

58,

59,

60]. A recent investigation localized these UPS-related alpha-giardins to the cytosol of the cell, as well as in close proximity to the membrane of the parasite’s peripheral endocytic compartments (PECs), membrane-bound endo-lysosomal organelles which were previously speculated to play a role in protein release [

14,

61,

62]. Further evidence from immunoprecipitation-based approaches and reconstruction of protein interactomes shows that these alpha-giardins build a protein complex at PECs which includes other UPS substrates. This opens up the possibility that alpha-giardins might act as both substrates

and mediators of UPS in Giardia, in virtue of their ability to bind and possibly destabilize membranes to aid traversal [

14].

4. Regulation of Annexin Function and Membrane Interaction

4.1. The Role of the N-Terminal Head Region

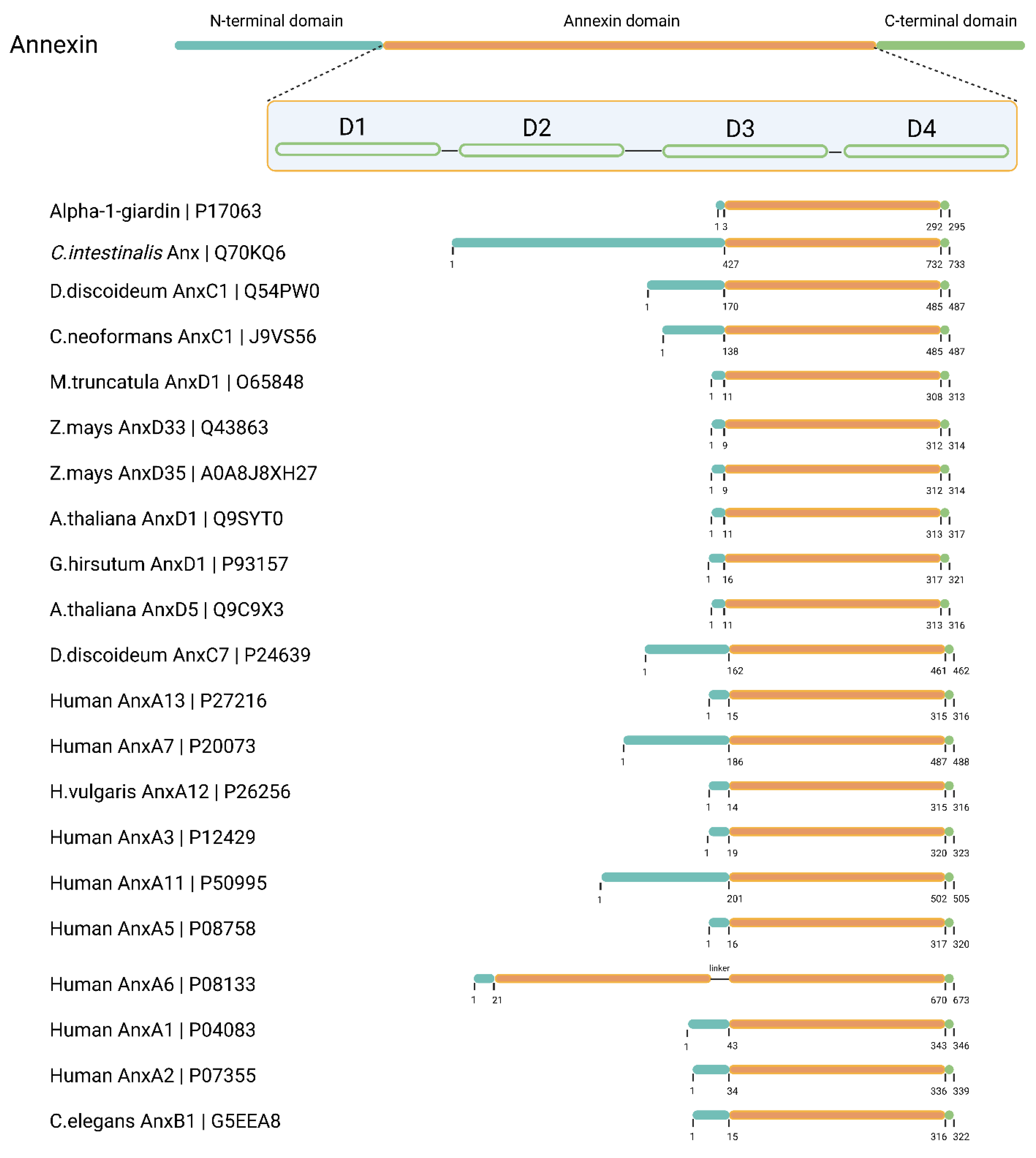

Annexins exhibit an overall conserved signature core structure. In contrast, the N-terminal head region exhibits significant variability and a generally disordered structure. However it is this feature that plays important roles in determining a given annexin’s function and protein interaction partners and, in its diversity, reflects the versatile role for annexins in cells.

Annexin heads can vary from only a few residues in length, as in AnxA3, AnxD1 or alpha-1-giardin to over 100 residues as in AnxA11, AnxC1, or

Ciona intestinalis annexin (UniProtID: Q70KQ6) [

3]. A documented example of this is the N-terminus of AnxA7. When it is removed, well-known AnxA7 functions such as calcium-dependent membrane binding, aggregation, and fusion, are all abolished or severely diminished [

63,

64].

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of the annexin structure, focusing on the diversity of N-terminal head domains. The figure highlights the annexins discussed in this review. Sequence information and predicted domain organization were extracted from UniProt and visualized schematically. D: annexin signature domains 1-4.

Figure 1.

A graphical representation of the annexin structure, focusing on the diversity of N-terminal head domains. The figure highlights the annexins discussed in this review. Sequence information and predicted domain organization were extracted from UniProt and visualized schematically. D: annexin signature domains 1-4.

The N’-terminal head domain is the main site of interaction with other protein partners. The S100 proteins, which are dimeric EF-hand calcium-binding proteins, are known to modulate the functions of annexins through their interactions [

65]. S100A10, a member of the S100 protein family, forms a tight complex with AnxA2, putatively enhancing its affinity for phospholipid membranes and promoting membrane fusion events [

66]. This interaction is crucial for various cellular processes, including exocytosis and endocytosis. Other annexins, such as AnxA6, have also been found to interact with S100 proteins, suggesting a broader role for these interactions in cellular processes [

67,

68]. Protein-protein interactions encompass the oligomerization of annexins. Specifically, AnxA13, an annexin unique to the human intestine, employs an alternative folding mechanism in its head domain to achieve dimerization. This process significantly influences its ability to bind to membranes[

69].

The N-terminal domain of annexins is not only involved in protein-protein interactions but also in post-translational modifications. For example, phosphorylation of the N-terminal domain of AnxA2 regulates interaction with S100A4 and S100A10 [

70]. Given the extensive diversity and ubiquitous presence of the annexin protein family and its head domains across various organisms, we still have a considerable journey ahead in uncovering all aspects of annexin regulation involving the N-terminus.

4.2. Calcium-Dependent Regulation and Notable Exceptions

Generally, calcium ions play a pivotal role in the regulation of annexins. The calcium-binding sites in annexins are located on the convex side of the protein, in the so-called type II calcium-binding motifs [

11]. The binding of calcium ions to specific sites on the annexin molecule changes the side’s overall charge and triggers a conformational change, enabling the annexin to bind to phospholipids present in the cell membrane [

11]. This calcium-induced binding is reversible and highly sensitive to changes in calcium concentration [

71]. Most annexin molecules contain multiple calcium-binding motifs, allowing for a modulable response to varying levels of calcium concentration. It follows that the sensitivity of annexins to calcium is not uniform across the family. Different annexins have different calcium sensitivities, which means they can be selectively activated or deactivated depending on the specific calcium concentration in the cell. This allows for a fine-tuned regulation of annexin functions in response to cellular calcium signals [

71,

72].

While calcium binding is a well-known characteristic of annexins, there are notable exceptions linked to pH. At lower pH, annexins interact with lipids, change their conformation, and insert themselves into the lipid membrane. This has been demonstrated

in vitro with AnxA5 and A13b, which undergo a conformational change at mildly acidic pH resembling that observed after calcium binding. This conformational change seems to be an intermediate state for the calcium-independent binding of AnxA5 to phosphatidylserine (PS)-liposomes at pH 4 and induces leakage from PS vesicles [

73,

74]. Interaction with negatively charged phospholipid vesicles at slightly low pH has also been described for AnxA4 [

75], which induces leakage from these vesicles, and for AnxA6, suggesting that this insertion is a prerequisite for the formation of calcium channels [

13]. A pH-driven calcium-independent insertion into PS-rich monolayers has also been observed in AnxA1 and has been suggested for AnxA5 [

10,

76]. In addition, studies carried out with AnxB12 from Hydra have revealed that annexins can be inserted into the lipid bilayer in acidic pH [

28]. Electron paramagnetic resonance analysis showed that this region refolded and formed a continuous amphipathic α-helix after calcium-independent binding to membranes at mildly acidic pH [

29]. These observations suggest the presence of a proton-dependent switch in annexins that harbors the information to induce membrane insertion.

The most notable exceptions are those of annexins that can bind to lipids independently of either Ca

2+ or pH. Two plant annexins - AnxD24 (AnxCa32) from

Capsicum annuum and AnxD1 from

Gossypium hirsutum have been studied in detail for their ability to bind liposomes in a calcium-independent fashion and at neutral pH, albeit at lower efficiency[

77]. This binding is regulated by three conserved surface-exposed residues on the convex side of the proteins, which play a crucial role in membrane binding.

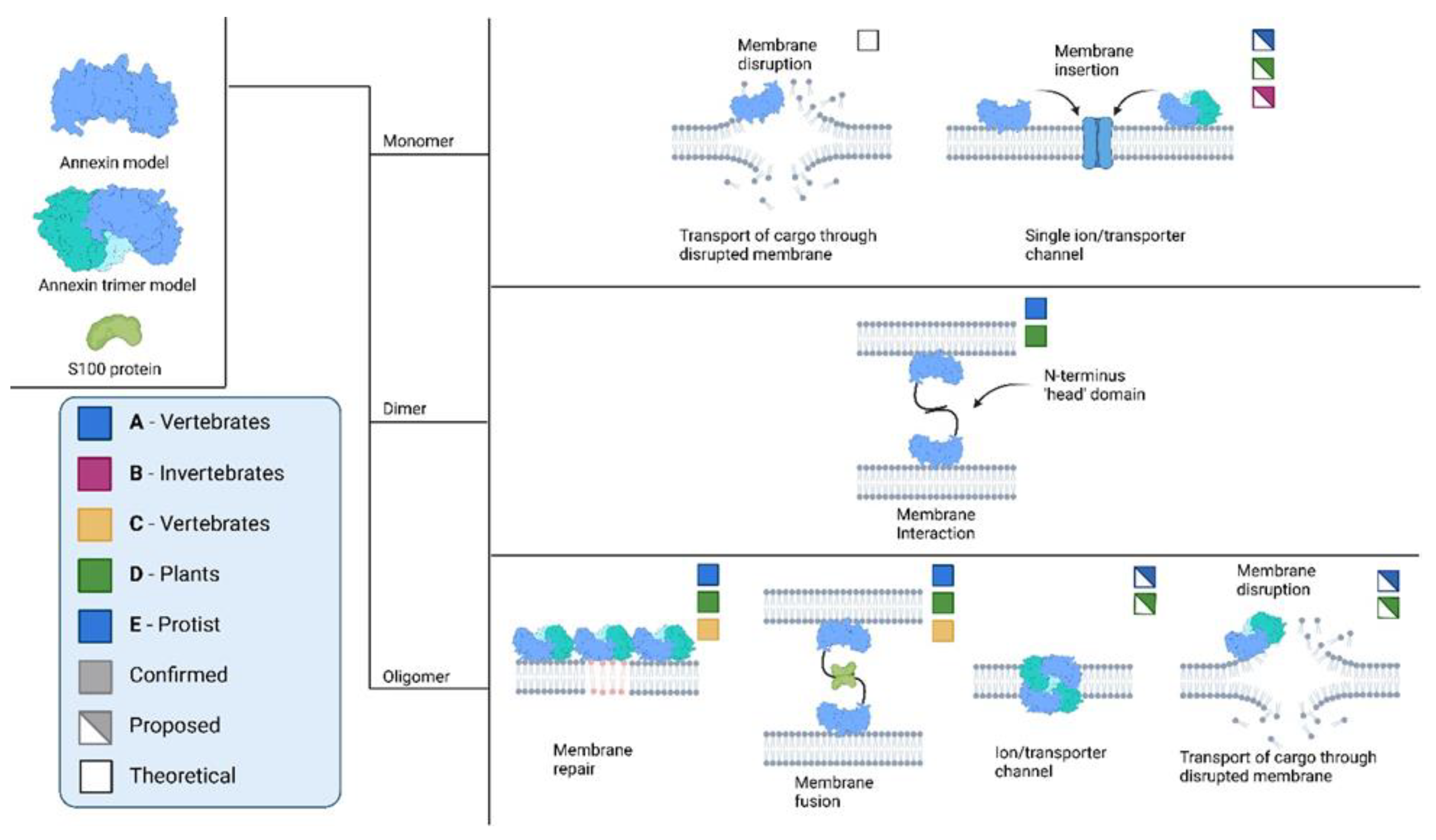

4.3. Oligomerization

Annexins often organize in oligomers, and their properties can fluctuate based on their oligomeric state. Both oligomerization involving the N-terminus head and oligomerization involving the core could occur, based on limited experimental evidence.

In the scenario involving the head domain, there are two possible outcomes. The first is the formation of homodimers through interaction with N-terminal domains, as demonstrated in AnxA4 and AnxA5 [

78]. The second outcome involves interaction with N-terminal domains and additional interaction with S100 proteins, resulting in tetramers or octamers, as seen in AnxA1 and AnxA2 [

31,

79,

80]. In the case of AnxA2, this protein forms oligomers upon binding to membranes containing negatively charged phospholipids. This seems to be facilitated by lateral protein-protein interactions, as evidenced by the compromised oligomer formation observed in AnxA2 mutants with amino acid substitutions in residues predicted to be involved in these interactions. Despite these mutations, AnxA2 still retains its ability to bind to negatively charged membranes in the presence of Ca

2+ [

81,

82]. This suggests that while lateral protein-protein interactions play a significant role in the formation of AnxA2 clusters at the membrane, they are not the sole determinant of membrane binding.

The second type of interaction between proteins is interaction within the core domain leading to the formation of trimers. Primarily it was described in crystal structures of AnxA5 [

30]. Using electron microscopy, AnxA5 was shown to organize in trimers at the membrane [

83]. Oligomerization in annexins depends on post-translational modifications presence of negatively charged lipids and calcium concentration [

35,

83]. These diverse interaction scenarios highlight the complex nature of annexin oligomerization and how this might be yet another level of regulation of annexin function in the cell.

Figure 2.

Possible and confirmed interactions of annexins across various biological kingdoms. Information extracted and adapted from several sources (Berendes et al., 1993; Harder and Gerke, 1993; Demange et al., 1994; Langen et al., 1998; Garbuglia et al., 2000; Oling, Bergsma-Schutter and Brisson, 2001; Gerke and Moss, 2002; Dempsey, Walsh and Shaw, 2003; Moss and Morgan, 2004; Naidu et al., 2005; McNeil et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2007; Ayala-Sanmartin et al., 2008; Laohavisit et al., 2009; Illien et al., 2010; Bouter et al., 2011; Kodavali et al., 2013; Eden et al., 2016; Ecsédi et al., 2017; Popa, Stewart and Moreau, 2018; Reviakine, 2018; Maryam et al., 2019; McCulloch et al., 2019; Lin, Chipot and Scheuring, 2020; Lichocka et al., 2022).

Figure 2.

Possible and confirmed interactions of annexins across various biological kingdoms. Information extracted and adapted from several sources (Berendes et al., 1993; Harder and Gerke, 1993; Demange et al., 1994; Langen et al., 1998; Garbuglia et al., 2000; Oling, Bergsma-Schutter and Brisson, 2001; Gerke and Moss, 2002; Dempsey, Walsh and Shaw, 2003; Moss and Morgan, 2004; Naidu et al., 2005; McNeil et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2007; Ayala-Sanmartin et al., 2008; Laohavisit et al., 2009; Illien et al., 2010; Bouter et al., 2011; Kodavali et al., 2013; Eden et al., 2016; Ecsédi et al., 2017; Popa, Stewart and Moreau, 2018; Reviakine, 2018; Maryam et al., 2019; McCulloch et al., 2019; Lin, Chipot and Scheuring, 2020; Lichocka et al., 2022).

5. Open Questions and Future Research Directions

Annexins, a diverse family of proteins, are present across a vast range of organisms and serve versatile functions. This short review demonstrates their remarkable versatility in action, properties, and interactions and underlines their crucial role in several essential cellular processes.

However, annexin diversity is truly underappreciated and under characterized. The majority of functional characterizations concern mammalian and plant annexins, with very limited investigation of B, C and E annexin types beyond cursory analysis of their membrane binding preferences. Mechanisms of annexin regulation are only partially understood, even in the field of mammalian annexins, with virtually no understanding of annexin regulatory mechanisms in other systems. Given the annexins are likely one of the most ancient eukaryotic protein families, with clear bacterial counterparts, it is possible to speculate that their core ability to bind membranes has evolved for adaptive deployment across different and often very diverged Eukaryotic taxa. Protist parasitic species such as G. lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica and Trypanosoma present significantly reduced and/or unique subcellular endomembrane compartments. Therefore, these species, and their free-living relatives, might be key to understanding conserved and perhaps ancestral features of annexin function and regulation which might be overshadowed in more complex cellular settings. For example, Giardia’s annexin orthologues, the alpha-giardins, almost all present extremely short N-termini, raising questions on how such short stretches could possibly mediate both homo and hetero-interaction, complex formation, post-translational modifications etc. and, perhaps even more intriguingly, how this might be adaptive to a parasitic lifestyle.

In conclusion, the annexin protein family constitutes an excellent candidate for a comprehensive investigation of diversity, functionality, regulation and protein/membrane interaction, given its almost ubiquitous distribution across Eukaryotes and its involvement in essential cellular processes. Thanks to the wealth of genomic sequences derived from both targeted and shot-gun genome sequencing approaches, it is now possible to explore annexin sequence diversity in unprecedented ways. Furthermore, using a wider range of genetically tractable experimental models to explore functional conservation and divergence, the evolutionary cell biology of this ancient and important protein family might finally come of age.

Author Contributions

All authors co-wrote, reviewed and finalized this manuscript. DW generated all figures with BioRender.com

Funding

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants PR00P3_179813 and 310030_219372, awarded to CF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, and in the writing of the manuscript.

References

- Gatenby RA (2019) The Role of Cell Membrane Information Reception, Processing, and Communication in the Structure and Function of Multicellular Tissue. Int J Mol Sci 20:3609. [CrossRef]

- Gerke V, Moss SE (2002) Annexins: From Structure to Function. [CrossRef]

- Moss SE, Morgan RO (2004) The annexins. Genome Biol 5:219. [CrossRef]

- Rescher U, Gerke V (2004) Annexins - Unique membrane binding proteins with diverse functions. J Cell Sci 117:2631–2639.

- Kodavali PK, Dudkiewicz M, Pikuła S, Pawłowski K (2014) Bioinformatics Analysis of Bacterial Annexins – Putative Ancestral Relatives of Eukaryotic Annexins. PLoS One 9:e85428. [CrossRef]

- Liemann S, ANITA LEWIT-BENTLEY A (1995) Annexins: a novel family of calcium-and membrane-binding proteins in search of a function.

- Mo Y, Campos B, Mealy TR, Commodore L, Head JF, Dedman JR, Seaton BA (2003) Interfacial basic cluster in annexin V couples phospholipid binding and trimer formation on membrane surfaces. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278:2437–2443. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Sun H, Tanowitz M, Liang X, Crooke ST (2016) Annexin A2 facilitates endocytic trafficking of antisense oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res gkw595. [CrossRef]

- Tcatchoff L, Andersson S, Utskarpen A, Klokk TI, Skånland SS, Pust S, Gerke V, Sandvig K (2012) Annexin A1 and A2: Roles in Retrograde Trafficking of Shiga Toxin. PLoS One 7:e40429. [CrossRef]

- Isas JM, Cartailler J-P, Sokolov Y, Patel DR, Langen R, Luecke H, Hall JE, Haigler HT (2000) Annexins V and XII Insert into Bilayers at Mildly Acidic pH and Form Ion Channels. Biochemistry 39:3015–3022. [CrossRef]

- Huber R, Schneider M, Mayr I, Römisch J, Paques E-P (1990) The calcium binding sites in human annexin V by crystal structure analysis at 2.0 A resolution Implications for membrane binding and calcium channel activity. FEBS Lett 275:15–21. [CrossRef]

- Berendes R, Voges D, Demange P, Huber R, Burger A (1993) Structure-Function Analysis of the Ion Channel Selectivity Filter in Human Annexin V. Science (1979) 262:427–430. [CrossRef]

- Golczak M, Kicinska A, Bandorowicz-Pikula J, Buchet R, Szewczyk A, Pikula S (2001) Acidic pH-induced folding of annexin VI is a prerequisite for its insertion into lipid bilayers and formation of ion channels by the protein molecules. The FASEB Journal 15:1083–1085. [CrossRef]

- Balmer EA, Wirdnam CD, Faso C (2023) A core UPS molecular complement implicates unique endocytic compartments at the parasite–host interface in Giardia lamblia. Virulence 14:. [CrossRef]

- Popa SJ, Stewart SE, Moreau K (2018) Unconventional secretion of annexins and galectins. Semin Cell Dev Biol 83:42–50. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali HN, Crichton SJ, Fabian C, Pepper C, Butcher DR, Dempsey FC, Parris CN (2024) A therapeutic antibody targeting annexin-A1 inhibits cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene 43:608–614. [CrossRef]

- Yan Z, Cheng X, Wang T, Hong X, Shao G, Fu C (2022) Therapeutic potential for targeting Annexin A1 in fibrotic diseases. Genes Dis 9:1493–1505. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Shao G, Hong X, Shi Y, Zheng Y, Yu Y, Fu C (2023) Targeting Annexin A1 as a Druggable Player to Enhance the Anti-Tumor Role of Honokiol in Colon Cancer through Autophagic Pathway. Pharmaceuticals 16:70. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Yu L, Hu B, Chen L, Jv M, Wang L, Zhou C, Wei M, Zhao L (2021) Advances in cancer treatment: a new therapeutic target, Annexin A2. J Cancer 12:3587–3596. [CrossRef]

- Geisow MJ, Walker JH, Boustead C, Taylor W (1987) Annexins—New family of Ca2+-regulated-phospholipid binding protein. Biosci Rep 7:289–298. [CrossRef]

- Creutz CE, Pazoles CJ, Pollard HB (1978) Identification and purification of an adrenal medullary protein (synexin) that causes calcium-dependent aggregation of isolated chromaffin granules. J Biol Chem 253:2858–66.

- Huang K-S, Wallner BP, Mattaliano RJ, Tizard R, Burne C, Frey A, Hession C, McGray P, Sinclair LK, Chow EP, Browning JL, Ramachandran KL, Tang J, Smart JE, Pepinsky RB (1986) Two human 35 kd inhibitors of phospholipase A2 are related to substrates of pp60v-src and of the epidermal growth factor receptor/kinase. Cell 46:191–199. [CrossRef]

- Flower RJ (1986) Background and discovery of lipocortins. Agents Actions 17:255–262. [CrossRef]

- Saris CJM, Tack BF, Kristensen T, Glenney JR, Hunter T (1986) The cDNA sequence for the protein-tyrosine kinase substrate p36 (calpactin I heavy chain) reveals a multidomain protein with internal repeats. Cell 46:201–212. [CrossRef]

- Glenney JR, Tack B, Powell MA (1987) Calpactins: two distinct Ca++-regulated phospholipid- and actin-binding proteins isolated from lung and placenta. J Cell Biol 104:503–511. [CrossRef]

- Gerke V, Gavins FNE, Geisow M, Grewal T, Jaiswal JK, Nylandsted J, Rescher U (2024) Annexins—a family of proteins with distinctive tastes for cell signaling and membrane dynamics. Nat Commun 15:1574. [CrossRef]

- Bitto E, Li M, Tikhonov AM, Schlossman ML, Cho W (2000) Mechanism of Annexin I-Mediated Membrane Aggregation. Biochemistry 39:13469–13477. [CrossRef]

- Ladokhin AS, Haigler HT (2005) Reversible Transition between the Surface Trimer and Membrane-Inserted Monomer of Annexin 12. Biochemistry 44:3402–3409. [CrossRef]

- Langen R, Isas JM, Hubbell WL, Haigler HT (1998) A transmembrane form of annexin XII detected by site-directed spin labeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95:14060–14065. [CrossRef]

- Oling F, Bergsma-Schutter W, Brisson A (2001) Trimers, dimers of trimers, and trimers of trimers are common building blocks of annexin A5 two-dimensional crystals. J Struct Biol 133:55–63. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Sanmartin J, Zibouche M, Illien F, Vincent M, Gallay J (2008) Insight into the location and dynamics of the annexin A2 N-terminal domain during Ca2+-induced membrane bridging. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1778:472–482. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer JC, Laohavisit A, Macpherson N, Webb A, Brownlee C, Battey NH, Davies JM (2008) Annexins: multifunctional components of growth and adaptation. J Exp Bot 59:533–544. [CrossRef]

- Bouter A, Gounou C, Bérat R, Tan S, Gallois B, Granier T, d’Estaintot BL, Pöschl E, Brachvogel B, Brisson AR (2011) Annexin-A5 assembled into two-dimensional arrays promotes cell membrane repair. Nat Commun 2:270. [CrossRef]

- McNeil AK, Rescher U, Gerke V, McNeil PL (2006) Requirement for Annexin A1 in Plasma Membrane Repair. Journal of Biological Chemistry 281:35202–35207. [CrossRef]

- Lichocka M, Krzymowska M, Górecka M, Hennig J (2022) Arabidopsis annexin 5 is involved in maintenance of pollen membrane integrity and permeability. J Exp Bot 73:94–109. [CrossRef]

- Maryam M, Fu MS, Alanio A, Camacho E, Goncalves DS, Faneuff EE, Grossman NT, Casadevall A, Coelho C (2019) The enigmatic role of fungal annexins: the case of Cryptococcus neoformans. Microbiology (N Y) 165:852–862. [CrossRef]

- Pervin MstS, Itoh G, Talukder MdSU, Fujimoto K, Morimoto Y V., Tanaka M, Ueda M, Yumura S (2018) A study of wound repair in Dictyostelium cells by using novel laserporation. Sci Rep 8:7969. [CrossRef]

- Laohavisit A, Mortimer JC, Demidchik V, Coxon KM, Stancombe MA, Macpherson N, Brownlee C, Hofmann A, Webb AAR, Miedema H, Battey NH, Davies JM (2009) Zea mays Annexins Modulate Cytosolic Free Ca2+ and Generate a Ca2+-Permeable Conductance. Plant Cell 21:479–493. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann A, Proust J, Dorowski A, Schantz R, Huber R (2000) Annexin 24 from Capsicum annuum. Journal of Biological Chemistry 275:8072–8082. [CrossRef]

- Kodavali PK, Skowronek K, Koszela-Piotrowska I, Strzelecka-Kiliszek A, Pawlowski K, Pikula S (2013) Structural and functional characterization of annexin 1 from Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 73:56–62. [CrossRef]

- Gorecka KM, Thouverey C, Buchet R, Pikula S (2007) Potential Role of Annexin AnnAt1 from Arabidopsis thaliana in pH-Mediated Cellular Response to Environmental Stimuli. Plant Cell Physiol 48:792–803. [CrossRef]

- Reviakine I (2018) When a transmembrane channel isn’t, or how biophysics and biochemistry (mis)communicate. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1860:1099–1104. [CrossRef]

- Demange P, Voges D, Benz J, Liemann S, Göttig P, Berendes R, Burger A, Huber R (1994) Annexin V: the key to understanding ion selectivity and voltage regulation? Trends Biochem Sci 19:272–276. [CrossRef]

- Eden ER, Sanchez-Heras E, Tsapara A, Sobota A, Levine TP, Futter CE (2016) Annexin A1 Tethers Membrane Contact Sites that Mediate ER to Endosome Cholesterol Transport. Dev Cell 37:473–483. [CrossRef]

- Eden ER, White IJ, Tsapara A, Futter CE (2010) Membrane contacts between endosomes and ER provide sites for PTP1B–epidermal growth factor receptor interaction. Nat Cell Biol 12:267–272. [CrossRef]

- Liao Y-C, Fernandopulle MS, Wang G, Choi H, Hao L, Drerup CM, Patel R, Qamar S, Nixon-Abell J, Shen Y, Meadows W, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TPJ, Nelson M, Czekalska MA, Musteikyte G, Gachechiladze MA, Stephens CA, Pasolli HA, Forrest LR, St George-Hyslop P, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Ward ME (2019) RNA Granules Hitchhike on Lysosomes for Long-Distance Transport, Using Annexin A11 as a Molecular Tether. Cell 179:147-164.e20. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Yuan S, Wei G, Qian D, Wu X, Jia H, Gui M, Liu W, An L, Xiang Y (2014) Annexin5 Is Essential for Pollen Development in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 7:751–754. [CrossRef]

- Shirakawa T, Nakamura A, Kohama K, Hirakata M, Ogihara S (2005) Class-Specific Binding of Two Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases to Annexin, a Ca2+- and Phospholipid-Binding Protein. Cell Struct Funct 29:159–164. [CrossRef]

- Arur S, Uche UE, Rezaul K, Fong M, Scranton V, Cowan AE, Mohler W, Han DK (2003) Annexin I Is an Endogenous Ligand that Mediates Apoptotic Cell Engulfment. Dev Cell 4:587–598. [CrossRef]

- Hayes MJ, Shao D, Bailly M, Moss SE (2006) Regulation of actin dynamics by annexin 2. EMBO J 25:1816–1826. [CrossRef]

- Andrawis A, Solomon M, Delmer DP (1993) Cotton fiber annexins: a potential role in the regulation of callose synthase. The Plant Journal 3:763–772. [CrossRef]

- Kuchler K, Thorner J (1992) Secretion of Peptides and Proteins Lacking Hydrophobic Signal Sequences: The Role of Adenosine Triphosphate-Driven Membrane Translocators*. Endocr Rev 13:499–514. [CrossRef]

- Wilkens S (2015) Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. F1000Prime Rep 7:. [CrossRef]

- Chapman LP, Epton MJ, Buckingham JC, Morris JF, Christian HC (2003) Evidence for a Role of the Adenosine 5′-Triphosphate-Binding Cassette Transporter A1 in the Externalization of Annexin I from Pituitary Folliculo-Stellate Cells. Endocrinology 144:1062–1073. [CrossRef]

- Wein S, Fauroux M, Laffitte J, de Nadaı̈ P, Guaı̈ni C, Pons F, Coméra C (2004) Mediation of annexin 1 secretion by a probenecid-sensitive ABC-transporter in rat inflamed mucosa. Biochem Pharmacol 67:1195–1202. [CrossRef]

- Fernández MB, Pagano MR, Daleo GR, Guevara MG (2012) Hydrophobic proteins secreted into the apoplast may contribute to resistance against Phytophthora infestans in potato. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 60:59–66. [CrossRef]

- Bauer B, Engelbrecht S, Bakker-Grunwald T, Scholze H (1999) Functional identification of α-giardin as an annexin of Giardia lamblia. FEMS Microbiol Lett 173:147–153. [CrossRef]

- Davids BJ, Palm JED, Housley MP, Smith JR, Andersen YS, Martin MG, Hendrickson BA, Johansen F-E, Svärd SG, Gillin FD, Eckmann L (2006) Polymeric Immunoglobulin Receptor in Intestinal Immune Defense against the Lumen-Dwelling Protozoan Parasite Giardia. The Journal of Immunology 177:6281–6290. [CrossRef]

- Dubourg A, Xia D, Winpenny JP, Al Naimi S, Bouzid M, Sexton DW, Wastling JM, Hunter PR, Tyler KM (2018) Giardia secretome highlights secreted tenascins as a key component of pathogenesis. Gigascience 7:. [CrossRef]

- Ma’ayeh SY, Liu J, Peirasmaki D, Hörnaeus K, Bergström Lind S, Grabherr M, Bergquist J, Svärd SG (2017) Characterization of the Giardia intestinalis secretome during interaction with human intestinal epithelial cells: The impact on host cells. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11:e0006120. [CrossRef]

- Moyano S, Musso J, Feliziani C, Zamponi N, Frontera LS, Ropolo AS, Lanfredi-Rangel A, Lalle M, Touz MC (2019) Exosome Biogenesis in the Protozoa Parasite Giardia lamblia: A Model of Reduced Interorganellar Crosstalk. Cells 8:1600. [CrossRef]

- Midlej V, de Souza W, Benchimol M (2019) The peripheral vesicles gather multivesicular bodies with different behavior during the Giardia intestinalis life cycle. J Struct Biol 207:301–311. [CrossRef]

- Naidu DG, Raha A, Chen X-L, Spitzer AR, Chander A (2005) Partial truncation of the NH2-terminus affects physical characteristics and membrane binding, aggregation, and fusion properties of annexin A7. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1734:152–168. [CrossRef]

- Chander A, Naidu DG, Chen X-L (2006) A ten-residue domain (Y11–A20) in the NH2-terminus modulates membrane association of annexin A7. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 1761:775–784. [CrossRef]

- Rintala-Dempsey AC, Rezvanpour A, Shaw GS (2008) S100–annexin complexes – structural insights. FEBS J 275:4956–4966. [CrossRef]

- Harder T, Gerke V (1993) The subcellular distribution of early endosomes is affected by the annexin II2p11(2) complex. J Cell Biol 123:1119–1132. [CrossRef]

- Chang N, Sutherland C, Hesse E, Winkfein R, Wiehler WB, Pho M, Veillette C, Li S, Wilson DP, Kiss E, Walsh MP (2007) Identification of a novel interaction between the Ca2+ -binding protein S100A11 and the Ca 2+ - and phospholipid-binding protein annexin A6. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 292:C1417–C1430. [CrossRef]

- Garbuglia M, Verzini M, Hofmann A, Huber R, Donato R (2000) S100A1 and S100B interactions with annexins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1498:192–206. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch KM, Yamakawa I, Shifrin DA, McConnell RE, Foegeding NJ, Singh PK, Mao S, Tyska MJ, Iverson TM (2019) An alternative N-terminal fold of the intestine-specific annexin A13a induces dimerization and regulates membrane-binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry 294:3454–3463. [CrossRef]

- Ecsédi P, Kiss B, Gógl G, Radnai L, Buday L, Koprivanacz K, Liliom K, Leveles I, Vértessy B, Jeszenői N, Hetényi C, Schlosser G, Katona G, Nyitray L (2017) Regulation of the Equilibrium between Closed and Open Conformations of Annexin A2 by N-Terminal Phosphorylation and S100A4-Binding. Structure 25:1195-1207.e5. [CrossRef]

- Trotter PJ, Orchard MA, Walker JH (1995) Ca2+ concentration during binding determines the manner in which annexin V binds to membranes. Biochemical Journal 308:591–598. [CrossRef]

- Raynal P, Pollard HB (1994) Annexins: the problem of assessing the biological role for a gene family of multifunctional calcium- and phospholipid-binding proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes 1197:63–93. [CrossRef]

- Turnay J, Lecona E, Fernández-Lizarbe S, Guzmán-Aránguez A, Fernández MP, Olmo N, Lizarbe MA (2005) Structure–function relationship in annexin A13, the founder member of the vertebrate family of annexins. Biochemical Journal 389:899–911. [CrossRef]

- Sopkova J, Vincent M, Takahashi M, Lewit-Bentley A, Gallay J (1998) Conformational Flexibility of Domain III of Annexin V Studied by Fluorescence of Tryptophan 187 and Circular Dichroism: The Effect of PH. Biochemistry 37:11962–11970. [CrossRef]

- Zschörnig O, Opitz F, Müller M (2007) Annexin A4 binding to anionic phospholipid vesicles modulated by pH and calcium. European Biophysics Journal 36:415–424. [CrossRef]

- Rosengarth A, Wintergalen A, Galla H-J, Hinz H-J, Gerke V (1998) Ca2+ -independent interaction of annexin I with phospholipid monolayers. FEBS Lett 438:279–284. [CrossRef]

- Dabitz N, Hu N-J, Yusof AM, Tranter N, Winter A, Daley M, Zschörnig O, Brisson A, Hofmann A (2005) Structural Determinants for Plant Annexin−Membrane Interactions. Biochemistry 44:16292–16300. [CrossRef]

- Kaetzel MA, Mo YD, Mealy TR, Campos B, Bergsma-Schutter W, Brisson A, Dedman JR, Seaton BA (2001) Phosphorylation Mutants Elucidate the Mechanism of Annexin IV-Mediated Membrane Aggregation. Biochemistry 40:4192–4199. [CrossRef]

- Illien F, Finet S, Lambert O, Ayala-Sanmartin J (2010) Different molecular arrangements of the tetrameric annexin 2 modulate the size and dynamics of membrane aggregation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1798:1790–1796. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey AC, Walsh MP, Shaw GS (2003) Unmasking the Annexin I Interaction from the Structure of Apo-S100A11. Structure 11:887–897. [CrossRef]

- Matos ALL, Kudruk S, Moratz J, Heflik M, Grill D, Ravoo BJ, Gerke V (2020) Membrane Binding Promotes Annexin A2 Oligomerization. Cells 9:1169. [CrossRef]

- Grill D, Matos ALL, de Vries WC, Kudruk S, Heflik M, Dörner W, Mootz HD, Ravoo BJ, Galla HJ, Gerke V (2018) Bridging of membrane surfaces by annexin A2. Sci Rep 8:. [CrossRef]

- Lin Y-C, Chipot C, Scheuring S (2020) Annexin-V stabilizes membrane defects by inducing lipid phase transition. Nat Commun 11:230. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).