Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approvale

2.2. Phenotypic Measurement and Sample Preparation

2.3. Whole Genome Resequencing

2.4. Copy Number Variation Segmentation and Genotyping

2.5. Genome-wide Association Study

2.6. The Copy Number Variation and Phenotypic Comparison Between Individuals with Significant CNVs and IMCGs were Verified by qPCR

2.7. Candidate Gene Annotation and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3. Results

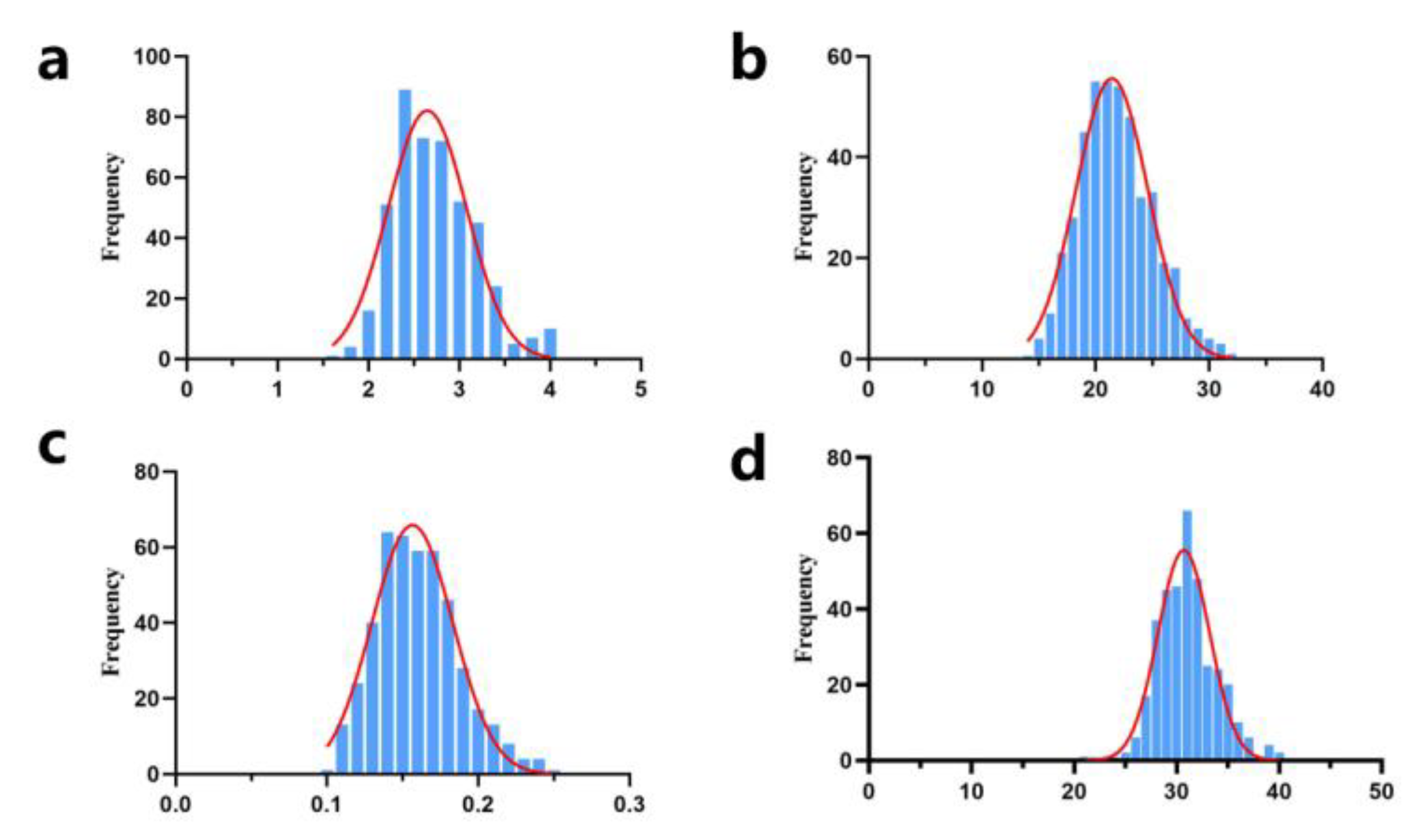

3.1. Phenotypic Statistics of Early Growth Traits in IMCGs

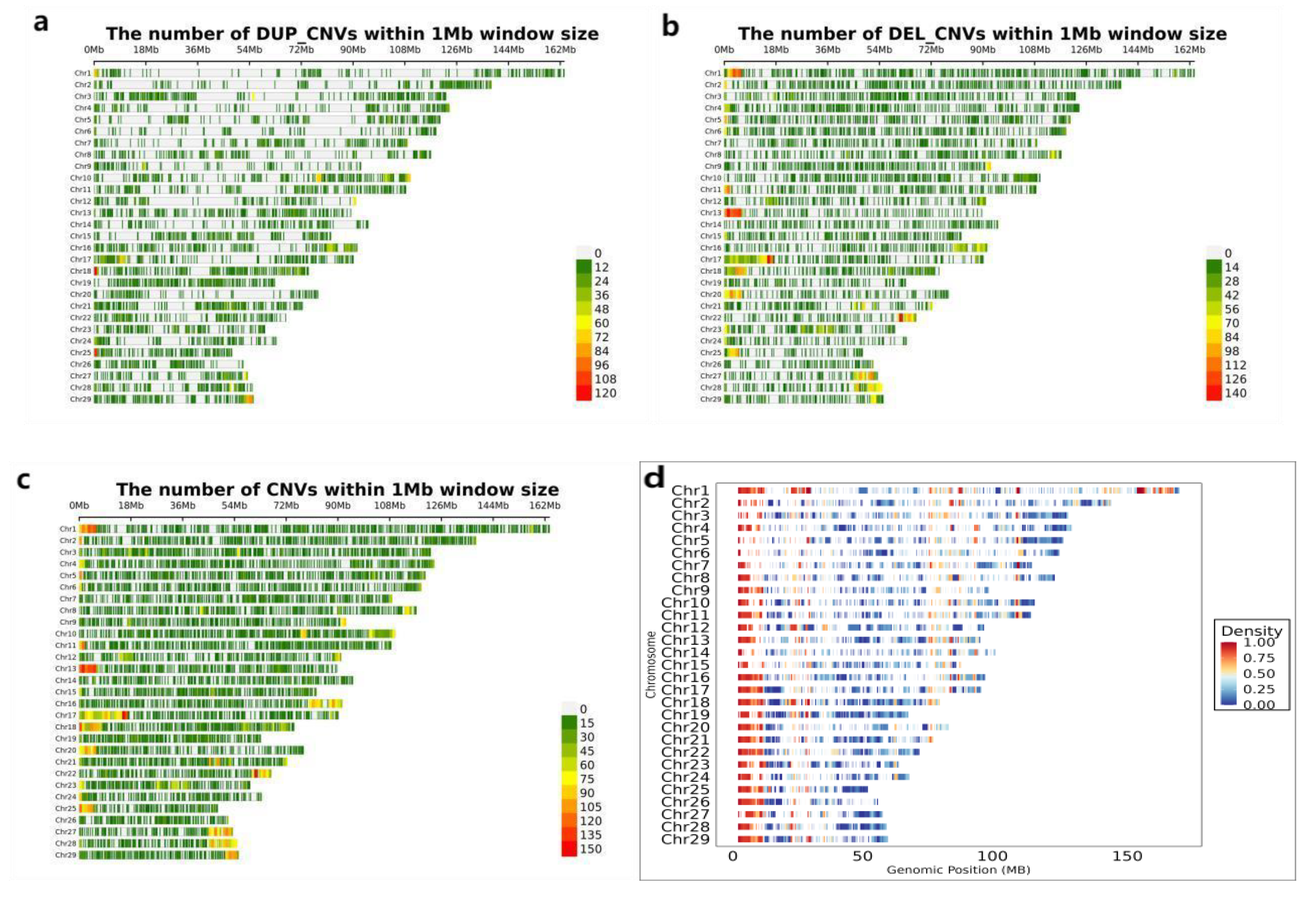

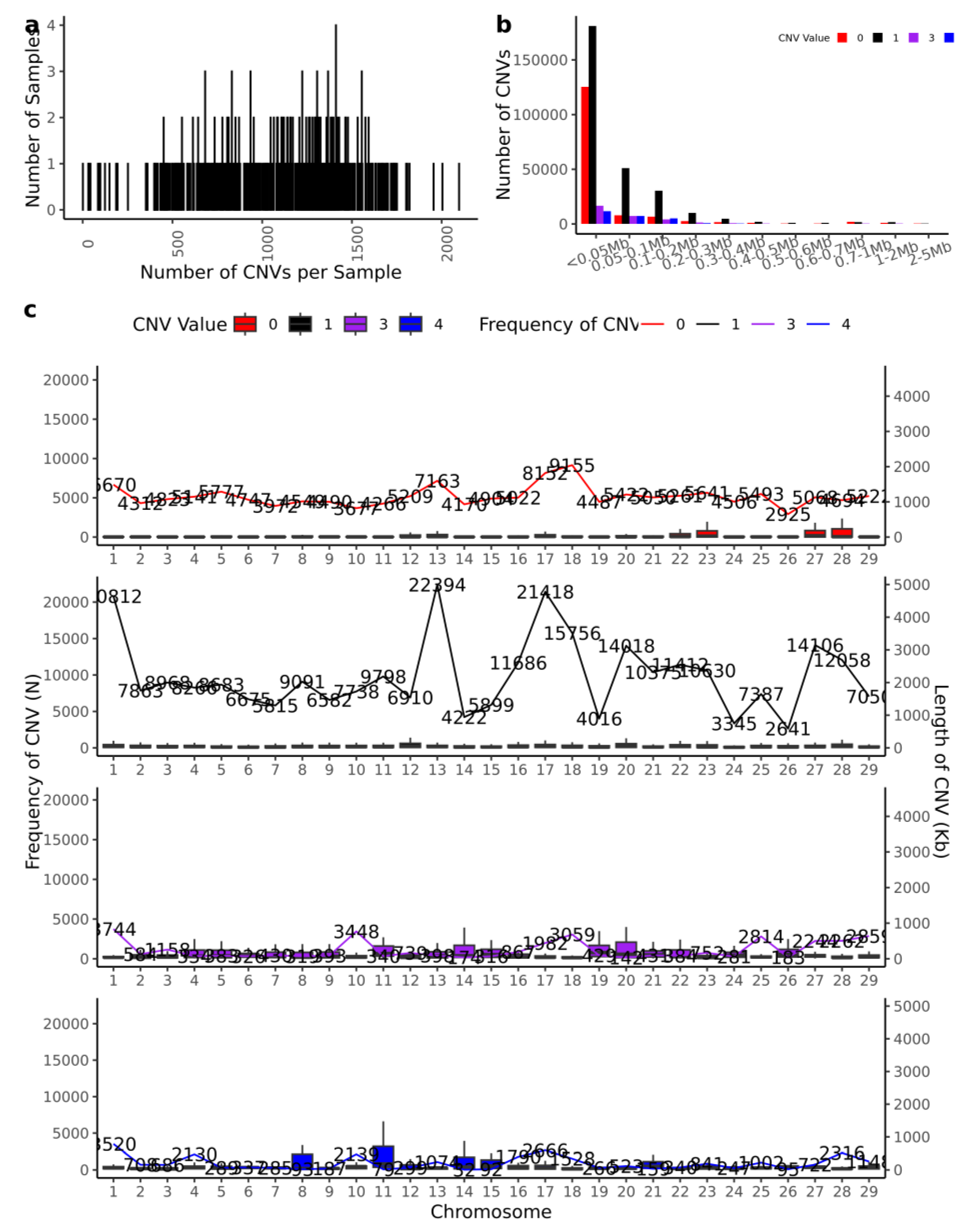

3.2. Detection of Genome-Wide Copy Number Variation in IMCGs

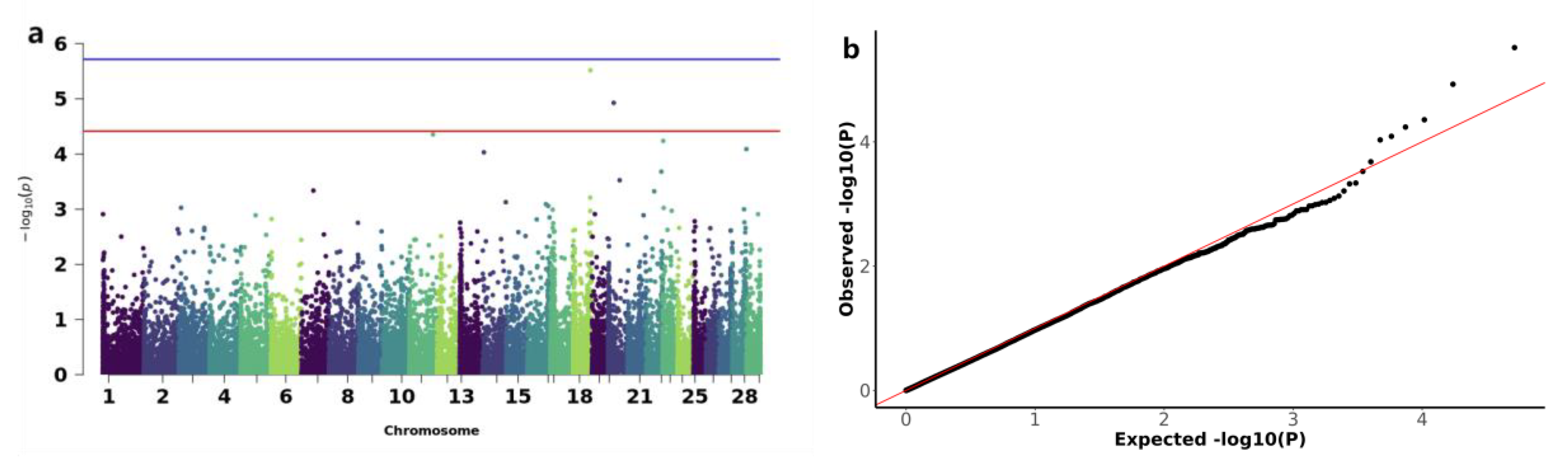

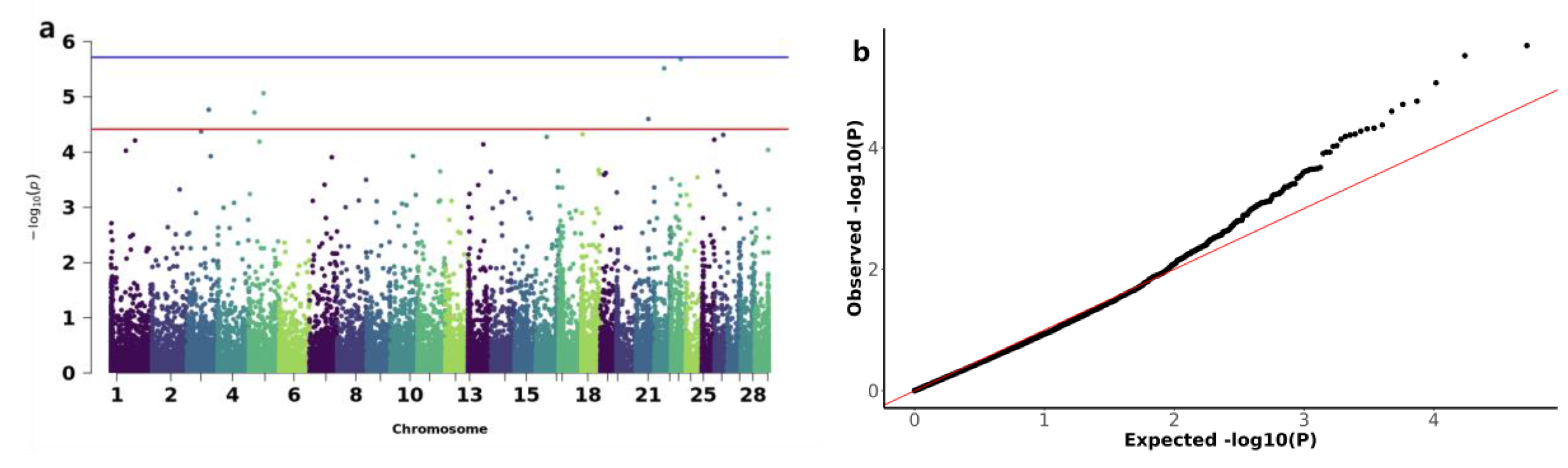

3.3. Genome-Wide Association Study of Copy Number Variations with Early Growth Traits in IMCGs

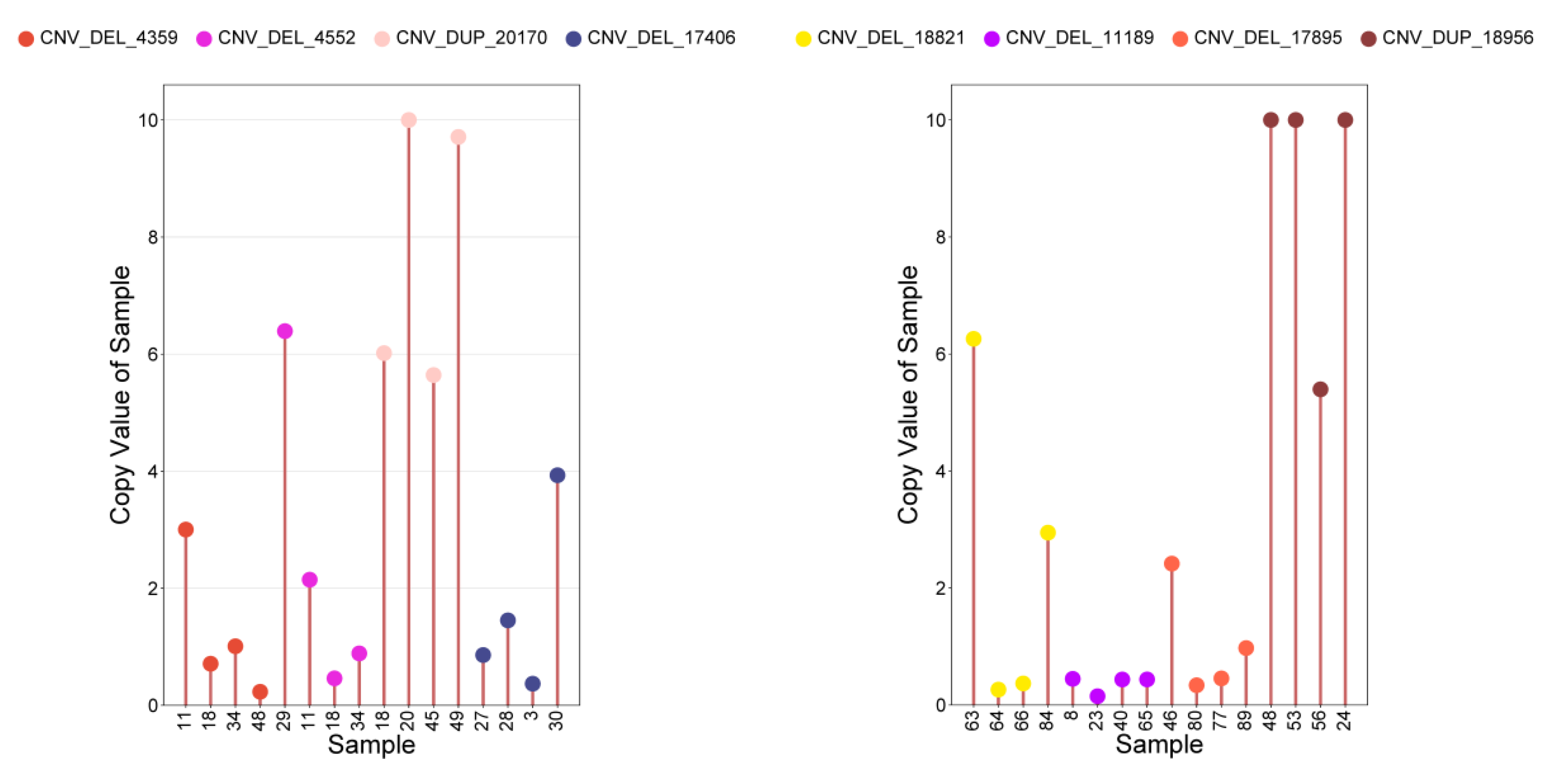

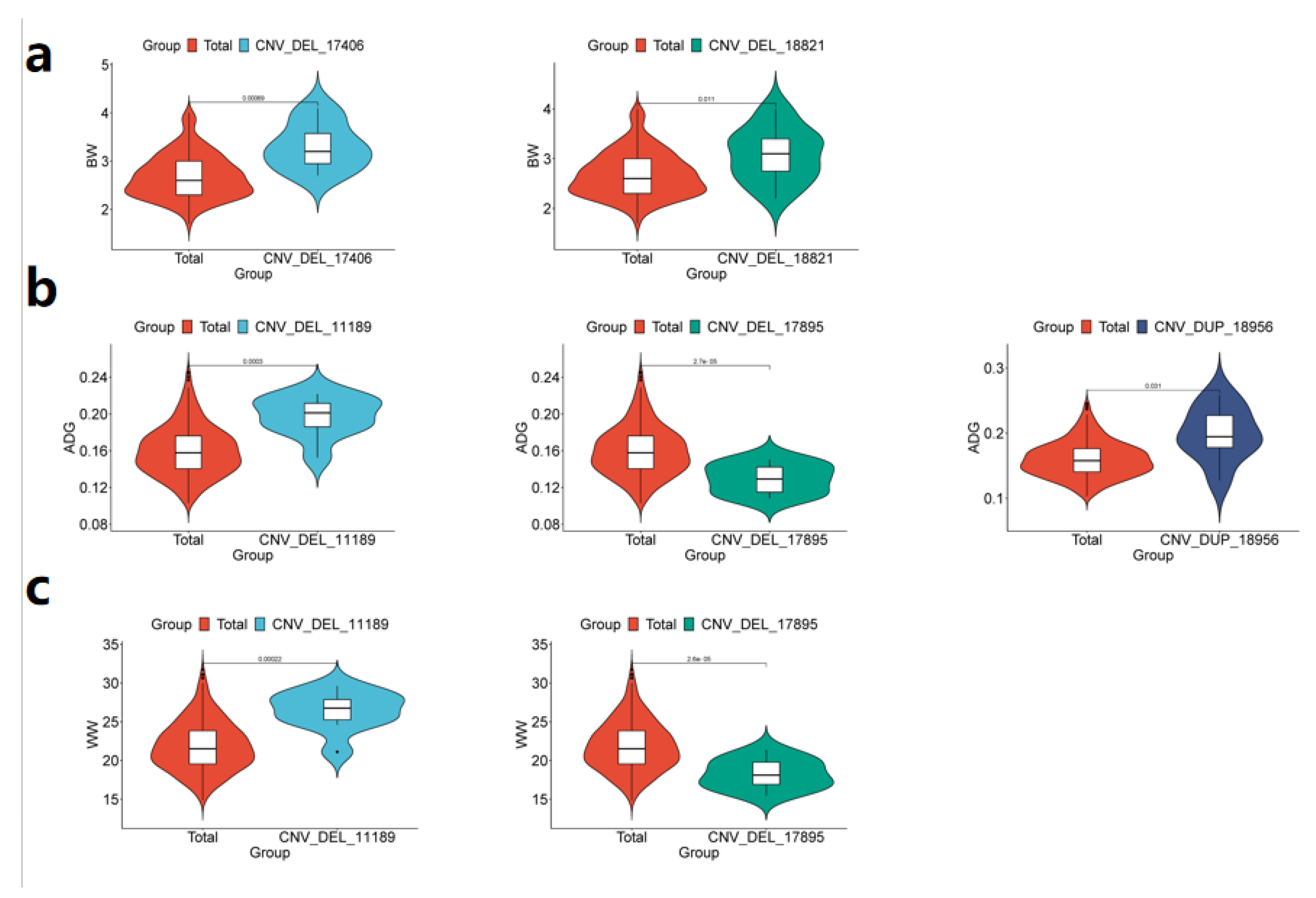

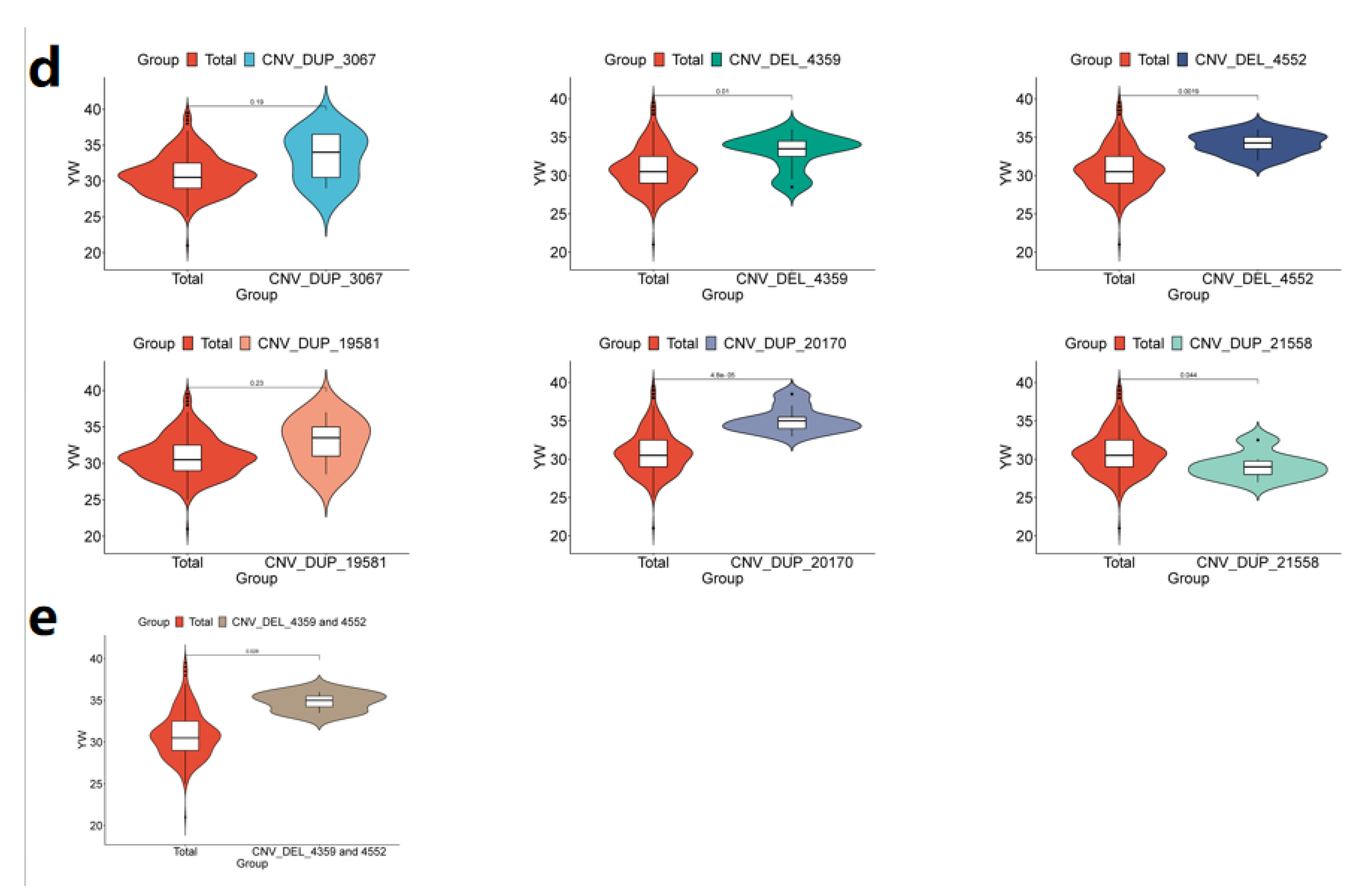

3.4. The Phenotypic Comparison Between the Identified CNVs and Individuals Containing Significant CNVs and IMCGs Populations was Verified by PCR analysis

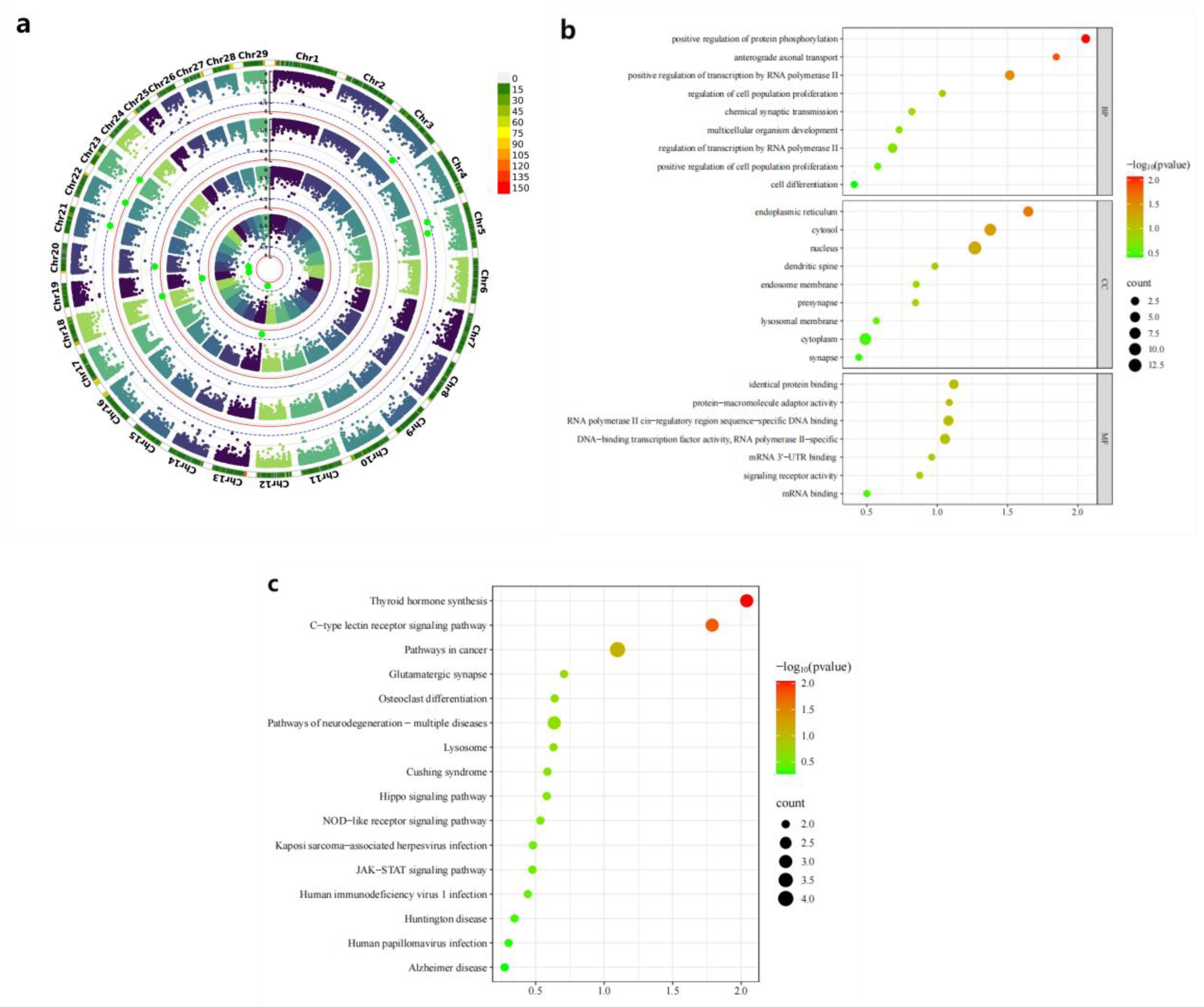

3.5. Functional Analysis of Genes Associated with Trait-related CNVs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| CNVs | Chr | Forward(5'-3') | Reverse(5'-3') |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNV_DEL_4359 | 5 | ACTGCCTGATACTGAGTTTCCA | CACAAATGTTTACAGCAGCGT |

| CNV_DEL_4552 | 5 | TGCAAGGAGGAAGCTAGACC | TGAGCAGAGTTCCATGTCCT |

| CNV_DUP_20170 | 22 | ATCTGGTGGGAGAGTTTGCA | GAGGGGAGGGGACAGTTATG |

| CNV_DEL_17406 | 18 | TCCTCCGAGTGTTCAAACCA | TCCCTATGTGTTTACGGTCT |

| CNV_DEL_18821 | 20 | AAGGAGACAAAGGAGGTGGG | TCAGCAGGGAGAGTGTTTCC |

| CNV_DEL_11189 | 13 | GACAGTGCTGCTACAACTCG | TCCTCTCCAGTGCTGACATG |

| CNV_DEL_17895 | 19 | GCCAGGCTGTGTAAGAAGTG | GGTGTCTTGCGTTGCTTAGG |

| CNV_DUP_18956 | 20 | TGCATGTCTGTGTGTGTGAC | TCCAACCCAGGGATTGAACC |

| ACTB | 1 | CCCTGGAGAAGAGCTACGAG | TAGTTTCGTGAATGCCGCAG |

| Chr | length (kb) | CNVR counts | Length of CNVR (kb) | Coverage (%) | Max size (kb) | Average size (kb) | Min size (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 163599655 | 344 | 66064800 | 40.38 | 5278400 | 192048.84 | 1600 |

| 2 | 138024171 | 267 | 50842400 | 36.84 | 4587200 | 190420.97 | 1600 |

| 3 | 122269964 | 276 | 44209600 | 36.16 | 4652000 | 160179.71 | 1600 |

| 4 | 123500297 | 247 | 39647200 | 32.10 | 2583200 | 160514.98 | 1600 |

| 5 | 120353402 | 254 | 36261600 | 30.13 | 4760800 | 142762.20 | 1600 |

| 6 | 118907578 | 217 | 35036800 | 29.47 | 5974400 | 161459.91 | 1600 |

| 7 | 108857206 | 245 | 36660800 | 33.68 | 3284000 | 149635.92 | 1600 |

| 8 | 117324300 | 216 | 37060000 | 31.59 | 4484000 | 171574.07 | 1600 |

| 9 | 92782956 | 213 | 25237600 | 27.20 | 1817600 | 118486.38 | 1600 |

| 10 | 109890027 | 266 | 41044000 | 37.35 | 1899200 | 154300.75 | 1600 |

| 11 | 108503269 | 225 | 43721600 | 40.30 | 5149600 | 194318.22 | 1600 |

| 12 | 91085198 | 123 | 42136000 | 46.26 | 4960000 | 342569.11 | 1600 |

| 13 | 89647956 | 139 | 40302400 | 44.96 | 5753600 | 289945.32 | 1600 |

| 14 | 95224248 | 181 | 27188000 | 28.55 | 3641600 | 150209.94 | 1600 |

| 15 | 82415014 | 193 | 29837600 | 36.20 | 2164000 | 154598.96 | 1600 |

| 16 | 91491535 | 147 | 38597600 | 42.19 | 6874400 | 262568.71 | 1600 |

| 17 | 90066741 | 158 | 44683200 | 49.61 | 6545600 | 282805.06 | 1600 |

| 18 | 74692390 | 139 | 45996000 | 61.58 | 4545600 | 330906.47 | 1600 |

| 19 | 63059135 | 111 | 41355200 | 65.58 | 9339200 | 372569.37 | 1600 |

| 20 | 78028267 | 118 | 25727200 | 32.97 | 5857600 | 218027.12 | 1600 |

| 21 | 72404257 | 144 | 27694400 | 38.25 | 2244000 | 192322.22 | 1600 |

| 22 | 67135385 | 109 | 29719200 | 44.27 | 6012800 | 272653.21 | 1600 |

| 23 | 59408587 | 102 | 30975200 | 52.14 | 5171200 | 303678.43 | 1600 |

| 24 | 63378952 | 125 | 20003200 | 31.56 | 2479200 | 160025.60 | 1600 |

| 25 | 48079060 | 75 | 26138400 | 54.37 | 6067200 | 348512.00 | 1600 |

| 26 | 51813540 | 104 | 17853600 | 34.46 | 6302400 | 171669.23 | 1600 |

| 27 | 53382197 | 88 | 18271200 | 34.23 | 3536000 | 207627.27 | 1600 |

| 28 | 54948720 | 91 | 26006400 | 47.33 | 4981600 | 285784.62 | 1600 |

| 29 | 55425393 | 97 | 27160800 | 49.00 | 5890400 | 280008.25 | 1600 |

References

- GAUTIER M, LALOE D, MOAZAMI-GOUDARZI K. Insights into the genetic history of French cattle from dense SNP data on 47 worldwide breeds [J]. PLoS One 2010, 5.

- LOZANO A C, DING H, ABE N, et al. Regularized multi-trait multi-locus linear mixed models for genome-wide association studies and genomic selection in crops [J]. BMC Bioinformatics 2023, 24, 399.

- ZHUANG Z, XU L, YANG J, et al. Weighted Single-Step Genome-Wide Association Study for Growth Traits in Chinese Simmental Beef Cattle [J]. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11.

- ZHANG L, LIU J, ZHAO F, et al. Genome-wide association studies for growth and meat production traits in sheep [J]. PLoS One 2013, 8, e66569.

- AL-MAMUN H A, KWAN P, CLARK S A, et al. Genome-wide association study of body weight in Australian Merino sheep reveals an orthologous region on OAR6 to human and bovine genomic regions affecting height and weight [J]. Genet Sel Evol 2015, 47, 66. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Z, PENG M, WEN Y, et al. Copy number variation of EIF4A2 loci related to phenotypic traits in Chinese cattle [J]. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 2147–2156. [CrossRef]

- LIU Y, WANG J, LI S, et al. Research progress of genomic copy number variation in livestock genetics and breeding [ J ]. China Livestock and Poultry Breeding Industry 2024, 20, 35–50.

- POS O, RADVANSZKY J, BUGLYO G, et al. DNA copy number variation: Main characteristics, evolutionary significance, and pathological aspects [J]. Biomed J 2021, 44, 548–559. [CrossRef]

- XU Y, JIANG Y, SHI T, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational landscape underlying phenotypic differences between two widespread Chinese cattle breeds [J]. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0183921.

- BENFICA L F, BRITO L F, DO BEM R D, et al. Genome-wide association study between copy number variation and feeding behavior, feed efficiency, and growth traits in Nellore cattle [J]. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 54.

- WANG K, ZHANG Y, HAN X, et al. Effects of Copy Number Variations in the Plectin (PLEC) Gene on the Growth Traits and Meat Quality of Leizhou Black Goats [J]. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13.

- WANG X, CAO X, WEN Y, et al. Associations of ORMDL1 gene copy number variations with growth traits in four Chinese sheep breeds [J]. Arch Anim Breed 2019, 62, 571–578. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FENG Z, LI X, CHENG J, et al. Copy Number Variation of the PIGY Gene in Sheep and Its Association Analysis with Growth Traits [J]. Animals (Basel) 2020, 10.

- QIU Y, DING R, ZHUANG Z, et al. Genome-wide detection of CNV regions and their potential association with growth and fatness traits in Duroc pigs [J]. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 332.

- XU, Q. Genome-wide association analysis of important traits in Inner Mongolia cashmere goats and design of low-density SNP chip [ D ], 2024.

- WANG Y, DING X, TAN Z, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Piglet Uniformity and Farrowing Interval [J]. Front Genet 2017, 8, 194. [CrossRef]

- CHEN S, ZHOU Y, CHEN Y, et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor [J]. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [CrossRef]

- LI H, DURBIN R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform [J]. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [CrossRef]

- LI, H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data [J]. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2987–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAO Y, JIANG J, YANG S, et al. CNV discovery for milk composition traits in dairy cattle using whole genome resequencing [J]. BMC Genomics 2017, 18, 265.

- ZHOU J, LIU L, LOPDELL T J, et al. HandyCNV: Standardized Summary, Annotation, Comparison, and Visualization of Copy Number Variant, Copy Number Variation Region, and Runs of Homozygosity [J]. Front Genet 2021, 12, 731355. [CrossRef]

- DING R, YANG M, QUAN J, et al. Single-Locus and Multi-Locus Genome-Wide Association Studies for Intramuscular Fat in Duroc Pigs [J]. Front Genet 2019, 10, 619. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- YANG Q, CUI J, CHAZARO I, et al. Power and type I error rate of false discovery rate approaches in genome-wide association studies [J]. BMC Genet 2005, 6 (Suppl S1), S134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. TURNER S. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots [J]. Journal of Open Source Software 2018, 3.

- AHLAWAT S, VASU M, CHOUDHARY V, et al. Comprehensive evaluation and validation of optimal reference genes for normalization of qPCR data in different caprine tissues [J]. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 268.

- QUINLAN A R, HALL I M. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features [J]. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [CrossRef]

- RIVALS I, PERSONNAZ L, TAING L, et al. Enrichment or depletion of a GO category within a class of genes: which test? [J]. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 401–407. [CrossRef]

- BUNIELLO A, MACARTHUR J A L, CEREZO M, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019 [J]. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D1005–d1012. [CrossRef]

- MANOLIO T A, COLLINS F S, COX N J, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases [J]. Nature 2009, 461, 747–753. [CrossRef]

- GRAHAM S E, CLARKE S L, WU K H, et al. The power of genetic diversity in genome-wide association studies of lipids [J]. Nature 2021, 600, 675–679. [CrossRef]

- GHASEMI M, ZAMANI P, VATANKHAH M, et al. Genome-wide association study of birth weight in sheep [J]. Animal 2019, 13, 1797–1803. [CrossRef]

- WANG X, ZHENG Z, CAI Y, et al. CNVcaller: highly efficient and widely applicable software for detecting copy number variations in large populations [J]. Gigascience 2017, 6, 1–12.

- KANG X, LI M, LIU M, et al. Copy number variation analysis reveals variants associated with milk production traits in dairy goats [J]. Genomics 2020, 112, 4934–4937. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHEN C, LIU C, XIONG X, et al. Copy number variation in the MSRB3 gene enlarges porcine ear size through a mechanism involving miR-584-5p [J]. Genet Sel Evol 2018, 50, 72. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GUANG-XIN E, YANG B G, ZHU Y B, et al. Genome-wide selective sweep analysis of the high-altitude adaptability of yaks by using the copy number variant [J]. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 259.

- ZHANG L, WANG F, GAO G, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Body Weight Traits in Inner Mongolia Cashmere Goats [J]. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 752746. [CrossRef]

- LIU Y, KHAN A R, GAN Y. C2H2 Zinc Finger Proteins Response to Abiotic Stress in Plants [J]. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23.

- ITO, M. Function and molecular evolution of mammalian Sox15, a singleton in the SoxG group of transcription factors [J]. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2010, 42, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YAMADA K, KANDA H, TANAKA S, et al. Sox15 enhances trophoblast giant cell differentiation induced by Hand1 in mouse placenta [J]. Differentiation 2006, 74, 212–221. [CrossRef]

- WU X, LI M, LI Y, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 11 (FGF11) promotes non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) progression by regulating hypoxia signaling pathway [J]. J Transl Med 2021, 19, 353. [CrossRef]

- CHO J H, KIM K, CHO H C, et al. Silencing of hypothalamic FGF11 prevents diet-induced obesity [J]. Mol Brain 2022, 15, 75. [CrossRef]

- LEE K W, JEONG J Y, AN Y J, et al. FGF11 influences 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation by modulating the expression of PPARgamma regulators [J]. FEBS Open Bio 2019, 9, 769–780. [CrossRef]

- JIANG T, SU D, LIU X, et al. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Fibroblast Growth Factor 11 (FGF11) Role in Brown Adipocytes in Thermogenic Regulation of Goats [J]. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24.

- ENGLISH J, OROFINO J, CEDERQUIST C T, et al. GPS2-mediated regulation of the adipocyte secretome modulates adipose tissue remodeling at the onset of diet-induced obesity [J]. Mol Metab 2023, 69, 101682. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DRARENI K, BALLAIRE R, BARILLA S, et al. GPS2 Deficiency Triggers Maladaptive White Adipose Tissue Expansion in Obesity via HIF1A Activation [J]. Cell Rep 2018, 24, 2957–2971 e2956. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HUANG X, WANG Z, LI D, et al. Study of microRNAs targeted Dvl2 on the osteoblasts differentiation of rat BMSCs in hyperlipidemia environment [J]. Journal of cellular physiology 2018, 233, 6758–6766. [CrossRef]

- ZHOU Y, SHANG H, ZHANG C, et al. The E3 ligase RNF185 negatively regulates osteogenic differentiation by targeting Dvl2 for degradation [J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 447, 431–436. [CrossRef]

- 48. PAN H, XU R, ZHANG Y. Role of SPRY4 in health and disease [J]. SFront Oncol 2024, 14, 1376873.

- LI N, CHEN Y, WANG H, et al. SPRY4 promotes adipogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells through the MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway [J]. Adipocyte 2022, 11, 588–600. [CrossRef]

- STEEN H C, GAMERO A M. STAT2 phosphorylation and signaling [J]. Jakstat 2013, 2, e25790.

- YANG Y, LUO D, SHAO Y, et al. circCAPRIN1 interacts with STAT2 to promote tumor progression and lipid synthesis via upregulating ACC1 expression in colorectal cancer [J]. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2023, 43, 100–122. [CrossRef]

| Trait | Number | Mean | SD | Max | Min | CV(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | 448 | 2.69 | 0.46 | 4.00 | 1.70 | 17.10 |

| WW | 443 | 21.90 | 3.28 | 31.73 | 14.86 | 14.98 |

| ADG | 443 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.246 | 0.103 | 18.75 |

| YW | 359 | 31.21 | 3.60 | 39.5 | 21 | 11.53 |

| Chr | CNVs counts | DUP_CNVs counts | Length of DUP_CNVs (kb) | Max size (kb) | Average size (kb) | Min size (kb) | DEL_CNVs counts | Length of DEL_CNVs (kb) | Max size (kb) | Average size (kb) | Min size (kb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1503 | 415 | 73980 | 3422 | 178 | 5.6 | 1088 | 93020 | 4050 | 85 | 1.6 | |

| 2 | 817 | 324 | 72388 | 4587 | 223 | 11.2 | 493 | 48960 | 2739 | 99 | 1.6 | |

| 3 | 1036 | 502 | 88685 | 3294 | 177 | 7.2 | 534 | 33659 | 1426 | 63 | 1.6 | |

| 4 | 827 | 328 | 63679 | 2690 | 194 | 9.6 | 499 | 40498 | 2582 | 81 | 1.6 | |

| 5 | 846 | 338 | 96786 | 4485 | 286 | 4.8 | 508 | 26974 | 2286 | 53 | 1.6 | |

| 6 | 633 | 174 | 33754 | 3142 | 194 | 12.8 | 459 | 40347 | 4634 | 88 | 1.6 | |

| 7 | 687 | 330 | 84095 | 3285 | 255 | 11.2 | 357 | 18855 | 1778 | 53 | 1.6 | |

| 8 | 880 | 352 | 64792 | 3549 | 184 | 7.2 | 528 | 12378 | 726 | 35 | 1.6 | |

| 9 | 655 | 214 | 31962 | 2146 | 149 | 8.8 | 441 | 34011 | 1710 | 77 | 1.6 | |

| 10 | 1203 | 705 | 97979 | 2422 | 139 | 8.0 | 498 | 33174 | 1249 | 67 | 0.8 | |

| 11 | 909 | 390 | 117598 | 3729 | 302 | 6.4 | 519 | 27412 | 1414 | 53 | 1.6 | |

| 12 | 720 | 258 | 46924 | 4130 | 182 | 10.4 | 462 | 87199 | 4165 | 189 | 1.6 | |

| 13 | 1310 | 378 | 125859 | 4086 | 333 | 9.6 | 932 | 58391 | 1208 | 63 | 1.6 | |

| 14 | 491 | 209 | 47794 | 4354 | 229 | 8.8 | 282 | 24636 | 3558 | 87 | 1.6 | |

| 15 | 715 | 362 | 70346 | 1770 | 194 | 8.8 | 353 | 22931 | 2049 | 65 | 1.6 | |

| 16 | 1229 | 559 | 121854 | 4996 | 218 | 5.6 | 670 | 2281 | 4857 | 73 | 1.6 | |

| 17 | 1638 | 500 | 106091 | 4653 | 212 | 8.0 | 1138 | 114083 | 2491 | 100 | 1.6 | |

| 18 | 1493 | 629 | 137963 | 4555 | 219 | 7.2 | 864 | 55394 | 1189 | 64 | 1.6 | |

| 19 | 609 | 374 | 113817 | 4564 | 304 | 11.2 | 235 | 10993 | 3342 | 47 | 0.8 | |

| 20 | 811 | 157 | 40919 | 2086 | 261 | 8.0 | 654 | 79986 | 2543 | 122 | 1.6 | |

| 21 | 924 | 405 | 93685 | 2100 | 231 | 9.6 | 519 | 24792 | 1257 | 48 | 0.8 | |

| 22 | 905 | 268 | 70214 | 3579 | 262 | 13.6 | 637 | 63890 | 2682 | 100 | 1.6 | |

| 23 | 880 | 281 | 71557 | 3488 | 255 | 9.6 | 599 | 55915 | 2194 | 93 | 1.6 | |

| 24 | 391 | 192 | 45366 | 4572 | 236 | 9.6 | 199 | 11270 | 2479 | 57 | 1.6 | |

| 25 | 755 | 326 | 91760 | 4768 | 281 | 7.2 | 429 | 27846 | 1980 | 65 | 1.6 | |

| 26 | 359 | 194 | 56654 | 4493 | 292 | 9.6 | 165 | 6951 | 670 | 42 | 1.6 | |

| 27 | 948 | 280 | 46586 | 2906 | 166 | 8.0 | 668 | 51005 | 1039 | 76 | 1.6 | |

| 28 | 1031 | 328 | 74822 | 3056 | 228 | 7.2 | 703 | 64270 | 1950 | 91 | 1.6 | |

| 29 | 798 | 444 | 98039 | 4518 | 221 | 8.8 | 354 | 12378 | 726 | 35 | 0.8 | |

| total | 26003 | 10216 | 2285946 | 224 | 15787 | 1183502 | 75 | |||||

| Trait | CNV ID | Type | Chr | Start(bp) | End(bp) | P-value | Candidate genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW | CNV_DEL_17406 | DEL | 18 | 67870401 | 67903200 | 3.04E-06 | ENK25,ZN845,ZN160,ZN208 |

| CNV_DEL_18821 | DEL | 20 | 22544801 | 22552000 | 1.18E-05 | ||

| WW | CNV_DEL_11189 | DEL | 13 | 3608001 | 4816000 | 7.61E-06 | TRA2B |

| CNV_DEL_17895 | DEL | 19 | 27445601 | 27462400 | 1.76E-05 | KCD11,SOX15,GBRAP,S35G3,TMM95,IPP2,SPEM1,CD68,SPEM2,SAT2,RNK,GPS2,CLD7,MPU1,TM102,BAP18,TNF13,TM256,MOT13,ZBTB4,ASGR1,PHF23,SHBG,CNEP1,PLS3,YBOX2,ACADV,IF5A1,IF4A1,ELP5,EFNB3,GLUT4,FGF11,BCL6B,DVL2,TNF12,TNK1,ACHB,SENP3,NEUL4,ACAP1,TCAB1,ASGR2,P53,FXR2,LOX12,NLGN2,DLG4,RPB1,DYH2 | |

| ADG | CNV_DEL_11189 | DEL | 13 | 3608001 | 4816000 | 7.61E-06 | TRA2B |

| CNV_DEL_17895 | DEL | 19 | 27445601 | 27462400 | 1.76E-05 | KCD11,SOX15,GBRAP,S35G3,TMM95,IPP2,SPEM1,CD68,SPEM2,SAT2,RNK,GPS2,CLD7,MPU1,TM102,BAP18,TNF13,TM256,MOT13,ZBTB4,ASGR1,PHF23,SHBG,CNEP1,PLS3,YBOX2,ACADV,IF5A1,IF4A1,ELP5,EFNB3,GLUT4,FGF11,BCL6B,DVL2,TNF12,TNK1,ACHB,SENP3,NEUL4,ACAP1,TCAB1,ASGR2,P53,FXR2,LOX12,NLGN2,DLG4,RPB1,DYH2 | |

| CNV_DUP_18956 | DUP | 20 | 69328801 | 69360800 | 2.55E-05 | TCTP,TCPE,ACKMT,ROP1L,CMBL,MARH6 | |

| YW | CNV_DUP_3067 | DUP | 3 | 85662401 | 86454400 | 1.71E-05 | RL4,NFIA |

| CNV_DEL_4359 | DEL | 5 | 20603201 | 20628800 | 1.93E-05 | ||

| CNV_DEL_4552 | DEL | 5 | 56564001 | 56606400 | 8.58E-06 | ELOC,SPRY4,APOF,IL23A,RDH16,APOF,GP182,CNPY2,RDH16,ATPB,MIP,RDH16,NACAM,RDH16,GLSL,PAN2,STAT2,PRI1,H17B6,TIM,BAZ2A,RBMS2 | |

| CNV_DUP_19581 | DUP | 21 | 48555201 | 48634400 | 2.51E-05 | TR10C,TR10D,LIPA1 | |

| CNV_DUP_20170 | DUP | 22 | 38884801 | 39041600 | 3.05E-06 | BHE40,ARL8B,SUMF1,ITPR1 | |

| CNV_DUP_21558 | DUP | 23 | 37214401 | 37316800 | 2.08E-06 |

| Trait | Chr | Gene | Significantly enriched pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| BW | 18 | ZN845 | |

| ADG、WW | 13 | SOX15 | cell differentiation、DNA-binding transcription factor activity、RNA polymerase II-specific |

| 19 | FGF11 | positive regulation of protein phosphorylation、cell differentiation | |

| 13 | GPS2 | regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II、Human T-cell leukemia virus 1 infection | |

| 19 | DVL2 | regulation of cell population proliferation、Signaling pathways regulating pluripotency of stem cells、positive regulation of protein phosphorylation | |

| YW | 5 | SPRY4 | cytosol |

| 5 | STAT2 | regulation of cell population proliferation、identical protein binding、Osteoclast differentiation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).