1. Introduction

Iron (Fe) and phosphorus (P) deficiencies are among the most critical agronomic challenges for global crop production, especially in calcareous soils. These soils, which occupy approximately 30% of the world’s agricultural land, are particularly prevalent in countries like Spain, where large areas in regions such as Aragón, Castilla-La Mancha, Andalucía, and the Basque Country are affected [

1]. Characterized by a high calcium carbonate (CaCO

3) content and alkaline pH levels above 7.5, calcareous soils limit the bioavailability of essential macro- and micronutrients including Fe, P, Zn, and Cu [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

In these soils, nutrients such as Fe and P exist in forms that are largely inaccessible to plants. Phosphorus tends to precipitate with Ca

2+ or Mg

2+ into insoluble forms or become adsorbed onto soil particles and iron oxides, drastically reducing its mobility and availability to roots [

8,

9]. Similarly, Fe, particularly in its oxidized ferric (Fe

3+) state, precipitates as hydroxides under high pH, resulting in chlorosis and growth inhibition in susceptible crops like rice [

10]. Moreover, the availability of Zn and Cu is also severely restricted in calcareous soils due to pH-induced changes in solubility and competition with other cations such as Ca

2+ [

11,

12].

Rice (

Oryza sativa L.) is particularly vulnerable to nutrient imbalances in such soil conditions. Although rice belongs to the graminaceous group and partially relies on Strategy II Fe acquisition via phytosiderophore secretion, it secretes insufficient amounts of these chelators, making it highly susceptible to Fe deficiency [

13]. Additionally, high soil pH conditions further exacerbate the problem by reducing the efficacy of Fe

3+ chelation and uptake [

14,

15].

In this context, the use of plant growth-promoting yeasts (PGPY) such as

Debaryomyces hansenii has emerged as a sustainable alternative to alleviate nutrient deficiencies. These microorganisms are known to improve plant nutrition by enhancing solubilization of mineral elements, modifying rhizospheric pH, and stimulating plant hormonal pathways [

16,

17]. Specifically,

D. hansenii has been reported to induce Fe deficiency responses in cucumber [

6] and to alleviate arsenic toxicity in rice, thereby promoting growth and nutrient status [

18]. The potential of yeasts to solubilize phosphate through acidification of the medium, typically via secretion of organic acids such as citric acid, has been well documented for species like

Yarrowia lipolytica,

Rhodotorula sp., and

Candida tropicalis [

19,

20]. Similarly, certain strains are capable of releasing Zn and K from insoluble mineral forms [

21,

22], supporting root development and biomass accumulation [

23]. In addition to nutrient solubilization, PGPY strains including

D. hansenii have demonstrated the capacity to synthesize phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellins, cytokinins, and abscisic acid (ABA), which are integral to root proliferation, nutrient uptake, and stress tolerance [

24,

25].

The objective of this study is to evaluate the role of D. hansenii (strain CBS767) in promoting growth, development, and yield of rice cultivated in limestone soil. The study further investigates its capacity to modulate rhizospheric pH, activate acid phosphatase activity, and induce the expression of genes involved in phosphate acquisition. These insights may support the use of D. hansenii as a biofertilizer to enhance rice production under challenging calcareous soil conditions.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Biological Material

Experiments were conducted using rice plants (

Oryza sativa L. var. ‘Puntal’). Seeds were sterilized following the methodology described by Aparicio et al. [

26]. They were sown on a layer of moist perlite at the bottom of a tray, to which 20 mL of a 5 mM CaCl

2 solution was added. The seeds were covered with another layer of moist perlite, and the tray was sealed with a plastic bag to prevent desiccation. Germination was carried out in the dark at 27 °C for 4 days. After germination, the seedlings were transferred to a growth chamber maintained at 25 °C during the day and 22 °C at night, with 70% relative humidity and a 14 h photoperiod at an irradiance of 300 μmol m

−2 s

−1 for 7 days. Subsequently, seedlings were moved to either a hydroponic system or calcareous soil.

To transfer seedlings to the hydroponic system, they were removed from the perlite tray and thoroughly cleaned to remove root residues. The nutrient solution used was R&M [

27], and aeration was continuously provided to avoid anoxia. Plants were kept under these conditions for 22 to 25 days, after which the treatments were applied.

For yeast inoculation, the wild-type genotype CBS767 of

D. hansenii, obtained from the Dutch “Central Bureau von Schimmelcultures” (

https://wi.knaw.nl/) and supplied by the Microbiology group at the University of Córdoba, was used. Yeast cultures were grown in YPD medium consisting of 2% D-glucose, 1% yeast extract, and 2% peptone [

28].

2.2. Inoculation and Experimental Setup in Calcareous Soil

To evaluate the effects of D. hansenii on rice plants under field-like conditions, experiments were conducted in 2 L pots filled with calcareous soil. Seedlings previously grown in perlite trays were transplanted into the pots, and two inoculation methods were tested.

The soil used to fill the pots was obtained from Santa Cruz (Córdoba; 37

◦47’03’’N 4

◦36’35’’W) and sterilized or not at 121 °C for 50 min twice. The physical-chemical properties and phosphorus and iron availability for the plant in the sampled soil are shown in (

Table 1).

In the pot experiments with calcareous soil, the following treatments were applied:

Plants grown in previously sterilized calcareous soil.

Plants grown in non-sterilized calcareous soil.

Plants inoculated by root immersion and grown in sterilized calcareous soil.

Plants inoculated by root immersion and grown in non-sterilized calcareous soil.

Plants inoculated by surface irrigation and grown in sterilized calcareous soil.

Plants inoculated by surface irrigation and grown in non-sterilized calcareous soil.

2.2.1. Root Inoculation

Some plants were inoculated by immersing their roots in a solution containing the desired inoculum concentration before transplanting. Roots were submerged in 1.5 L of a 10

7 cells/mL yeast suspension in deionized water under constant agitation for 30 min, ensuring effective contact between the yeast and the roots [

29].

2.2.2. Irrigation Inoculation

For this method, pots were irrigated with the inoculum suspension (107 cells/mL in deionized water) until field capacity was reached.

2.3. Inoculation in Hydroponic System

The experiments were conducted using rice plants (

Oryza sativa L. var. ‘Puntal’). The seeds were surface-sterilized as described by Aparicio et al. [

26]. Subsequently, the seedlings were grouped in sets of eight and transferred to a hydroponic system. Each group of eight seedlings was placed in plastic lids and held in holes of a thin polyurethane sheet floating on an aerated nutrient solution R&M [

27] containing 2 mM Ca(NO

3)

2, 0.75 mM K

2SO

4, 0.65 mM MgSO

4, 0.5 mM KH

2PO

4, 50 μM KCl, 10 μM H

3BO

3, 1 μM MnSO

4, 0.5 μM CuSO

4, 0.5 μM ZnSO

4, 0.05 μM (NH

4)

6Mo

7O

24, and 45 μM Fe-EDTA for Plants grown in complete nutrient solution. For plants grown in P-deficient nutrient solution 0.5 mM KH

2PO

4 was remplace by 0.5 mM KOH.

For hydroponic experiments, the yeast suspension (107 cells/mL) was directly added to the nutrient solution with and without phosphorus (P). Control treatments without inoculation were included. Plants were sampled at three time points (7, 9 and 11 days post-treatment) to assess acid phosphatase activity and gene expression. Six replicates were performed for each treatment.

The following treatments were applied:

Plants grown in complete nutrient solution.

Plants grown in complete nutrient solution plus inoculum.

Plants grown in P-deficient nutrient solution.

Plants grown in P-deficient nutrient solution plus inoculum.

2.4. Chlorophyll Content (SPAD)

Chlorophyll content was measured using a Minolta SPAD-502 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo [Japan]) portable device. Four readings were taken from the youngest fully extended leaf per plant, averaging the values for representation.

2.5. Growth Promotion and Yield Production

At the end of the growth cycle, rice plants from all treatments were harvested to measure fresh shoot weight. Samples were then dried at 75 °C for 3 days to obtain dry weight and calculate the dry matter percentage:

Rice grain yield was also determined, accounting for moisture percentage uniformity across treatments.

2.6. Elemental Analysis of Leaves

Dried leaves were homogenized using a grinder. Samples were digested with 3 mL of 65% HNO3 and incubated at room temperature for 16 h, followed by heating at 85 °C for 1.5 h. When vapor began to appear, 1 mL of 60% HClO4 was added, and heating continued until white vapor indicated complete digestion. Samples were diluted to 10 mL with deionized water. Elemental analysis (Zn, Fe, Cu, Mn) was performed using flame atomic absorption spectrometry. Phosphorus was determined using the molybdovanadate method.

2.7. Acid Phosphatase Determination

Acid phosphatase activity was evaluated using the BCIP substrate, which turns blue upon enzymatic dephosphorylation. Roots were incubated in 0.01% BCIP solution for 2 h to assess enzyme activity visually [

30].

2.8. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

RNA extraction was carried out using Tri Reagent following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was measured at 260 nm. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and random hexamers. Gene expression was analysed via qRT-PCR, with 40 amplification cycles and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix and using the primers listed in

Table 2.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data normality and variance homogeneity were verified. ANOVA and post hoc Tukey’s or Dunnett’s tests (p < 0.05) were applied to compare treatments. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v9, and the graphs were generated using Microsoft Excel.

4. Discussion

Rice plants cultivated in calcareous soil often face multiple nutrient deficiencies due to the high pH and the specific physicochemical characteristics of these soils. Typically, calcareous soils have a pH above 7.5 and contain significant amounts of calcium carbonate (CaCO

3). The elevated pH can limit the availability of certain nutrients, while high calcium content may interfere with the uptake of others. Among the nutrients whose availability is commonly restricted under these conditions are iron (Fe), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn) [

11], zinc (Zn) [

31], and phosphorus (P) [

32], among others. These deficiencies often result in stunted growth, reduced tillering, and lower grain yields [

33]. Additionally, they can impair grain filling, leading to poorer grain quality and reduced market value [

34]. Nutrient-deficient plants are also more susceptible to pest and disease attacks [

35], which translates into economic losses for farmers [

36].

Numerous studies have shown that beneficial soil microorganisms provide promising strategies to address nutrient deficiencies, especially in problematic soils such as calcareous soils. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) are among the most widely used, as they enhance nutrient uptake by forming extensive hyphal networks that improve the absorption of phosphorus and several micronutrients that are often poorly available in high-pH soils [

37]. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), such as

Pseudomonas spp., produce organic acids and siderophores that chelate micronutrients, thereby increasing their availability in alkaline environments [

38]. Other microbes can release organic acids that slightly lower the soil pH, improving nutrient solubility [

39]. Additionally, microorganisms that trigger induced systemic resistance (ISR) have been shown to enhance iron acquisition by activating deficiency-response mechanisms [

40,

41].

Plant growth-promoting yeasts (PGPY) have gained interest in recent years due to their ability to colonize plant tissues and produce phytohormones, thereby enhancing nutrient availability and soil fertility [

42]. This chapter aimed to explore the potential effects of the yeast

D. hansenii (Dh) on rice plant development in calcareous soil. This yeast is considered halotolerant, capable of growing in environments with high salt concentrations (5–15%) and also under low salinity (< 0.1 M) [

43,

44]. These features make it a strong candidate for application in calcareous soil systems. If its ability to enhance rice development is confirmed, it could be used as a biofertilizer.

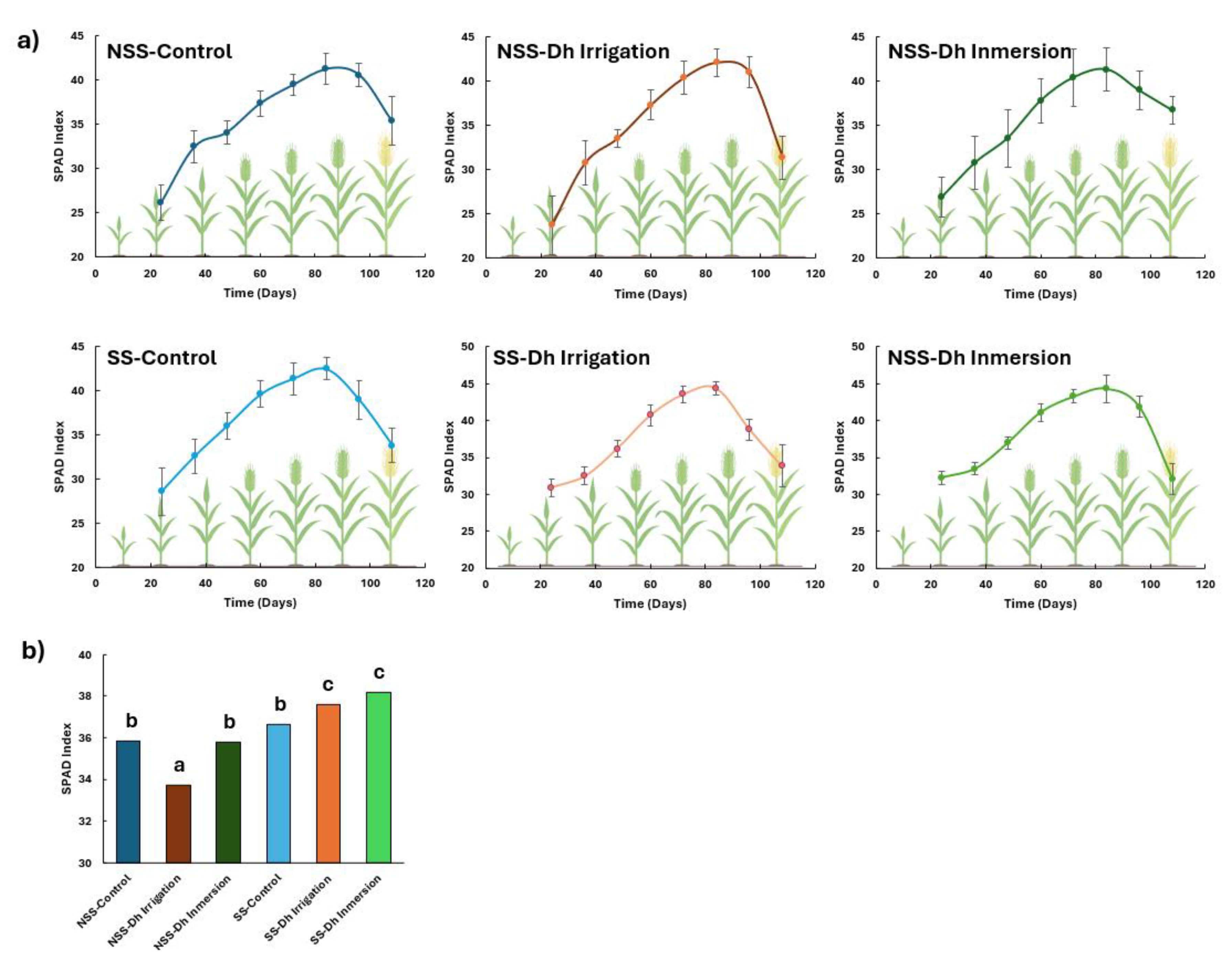

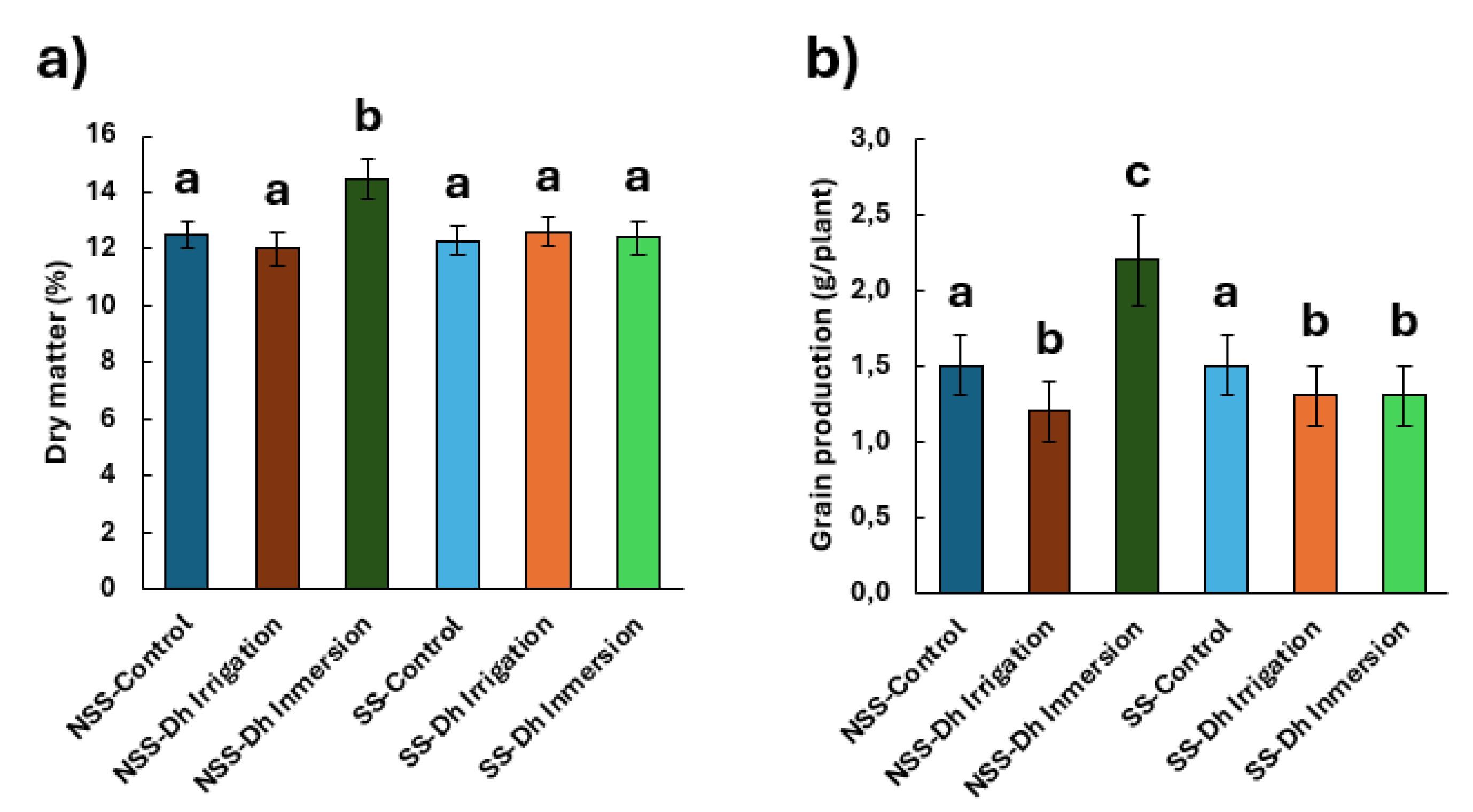

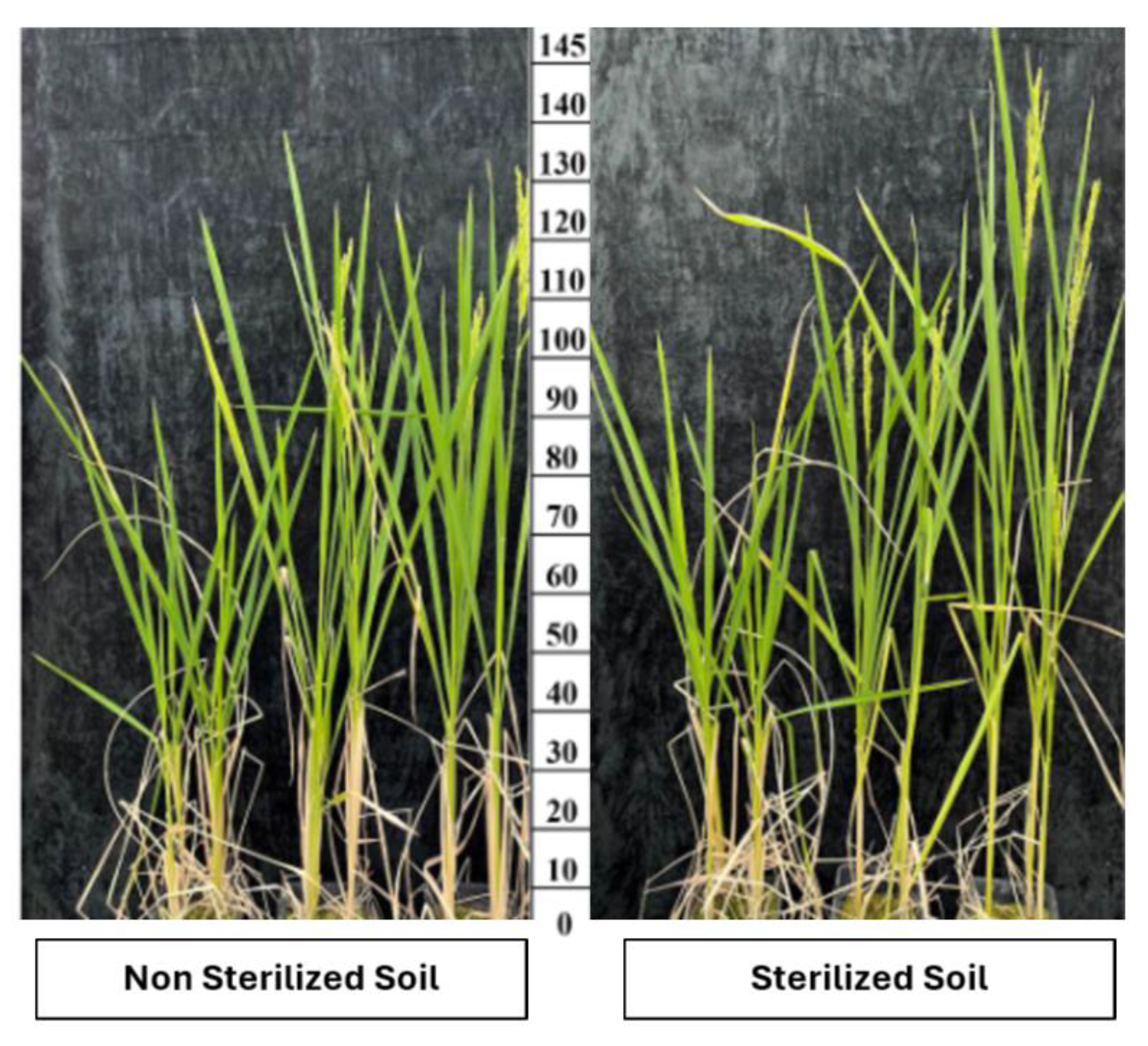

Indeed, our results demonstrated that

D. hansenii promoted rice plant growth by increasing chlorophyll content (SPAD index), plant height, dry matter accumulation, and grain production (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). To our knowledge, no previous studies have directly reported the effect of

D. hansenii on chlorophyll content in rice. However, environmental factors such as light intensity, temperature, and nutrient availability, which can be influenced by microbial inoculants, play key roles in chlorophyll biosynthesis and, consequently, plant development and productivity.

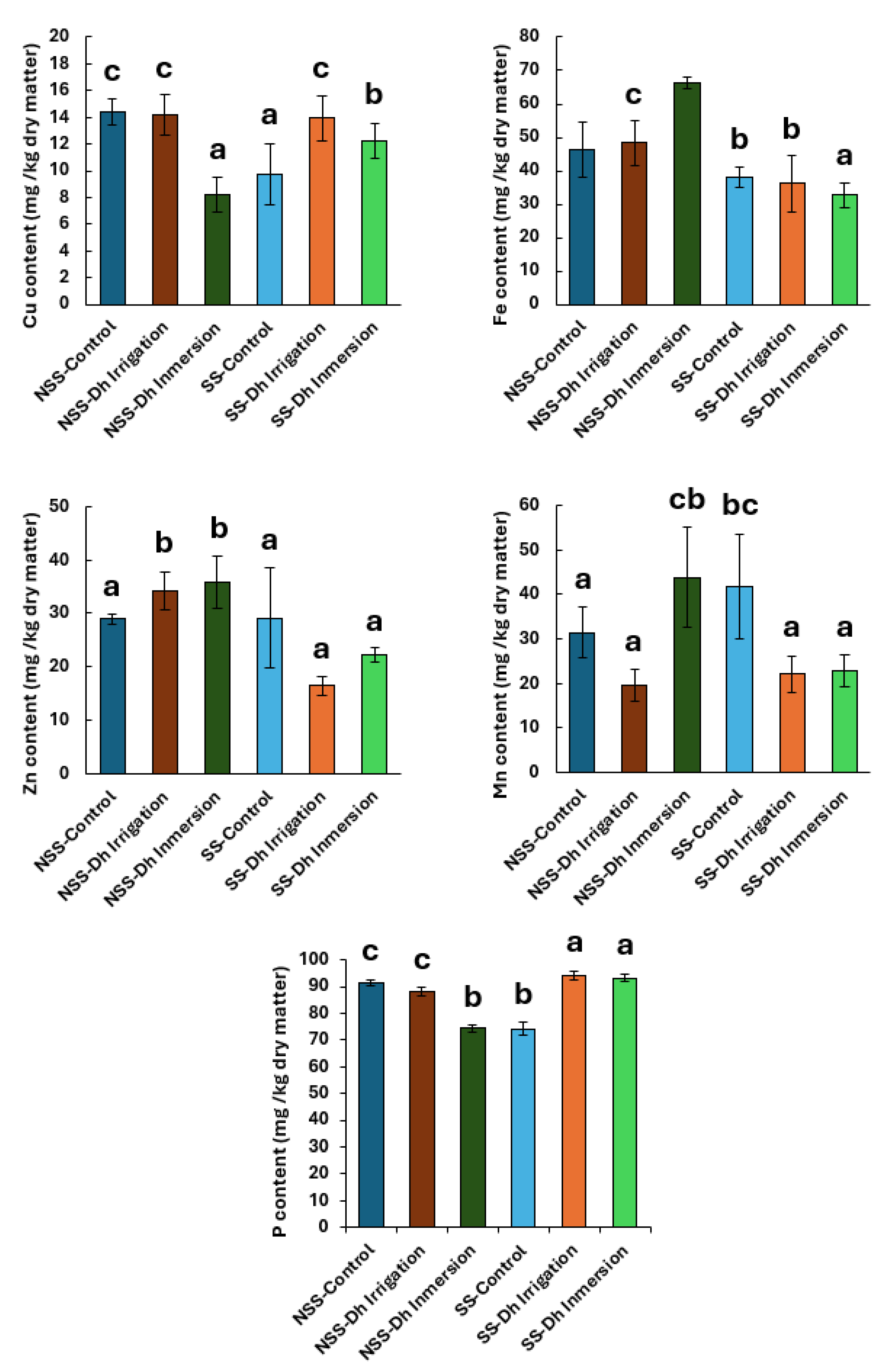

Moreover, increases in foliar concentrations of Cu, Fe, Zn, and Mn were observed in plants inoculated with

D. hansenii under specific cultivation conditions (

Figure 4). Kaur et al. [

18] reported improved growth and nutritional status in rice plants inoculated with

D. hansenii. Similar results have been obtained with other microorganisms in different crops. For example,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Enterobacter spp. promoted the growth of alfalfa under alkaline conditions [

45], while

Agrobacterium,

Bacillus, and

Alcaligenes strains enhanced growth and mineral nutrition in strawberry plants [

46].

Although no clear increase in phosphorus content was detected in inoculated plants (

Figure 4,

D. hansenii significantly induced acid phosphatase activity under both phosphorus-sufficient and -deficient conditions (

Figure 5). It is well established that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance P uptake by increasing acid phosphatase activity in the root zone, thereby aiding in the solubilization of organic phosphorus compounds [

47]. Certain endophytic strains such as

Pantoea and

Colletotrichum have also been shown to produce acid phosphatases and improve phosphorus uptake in plants [

48].

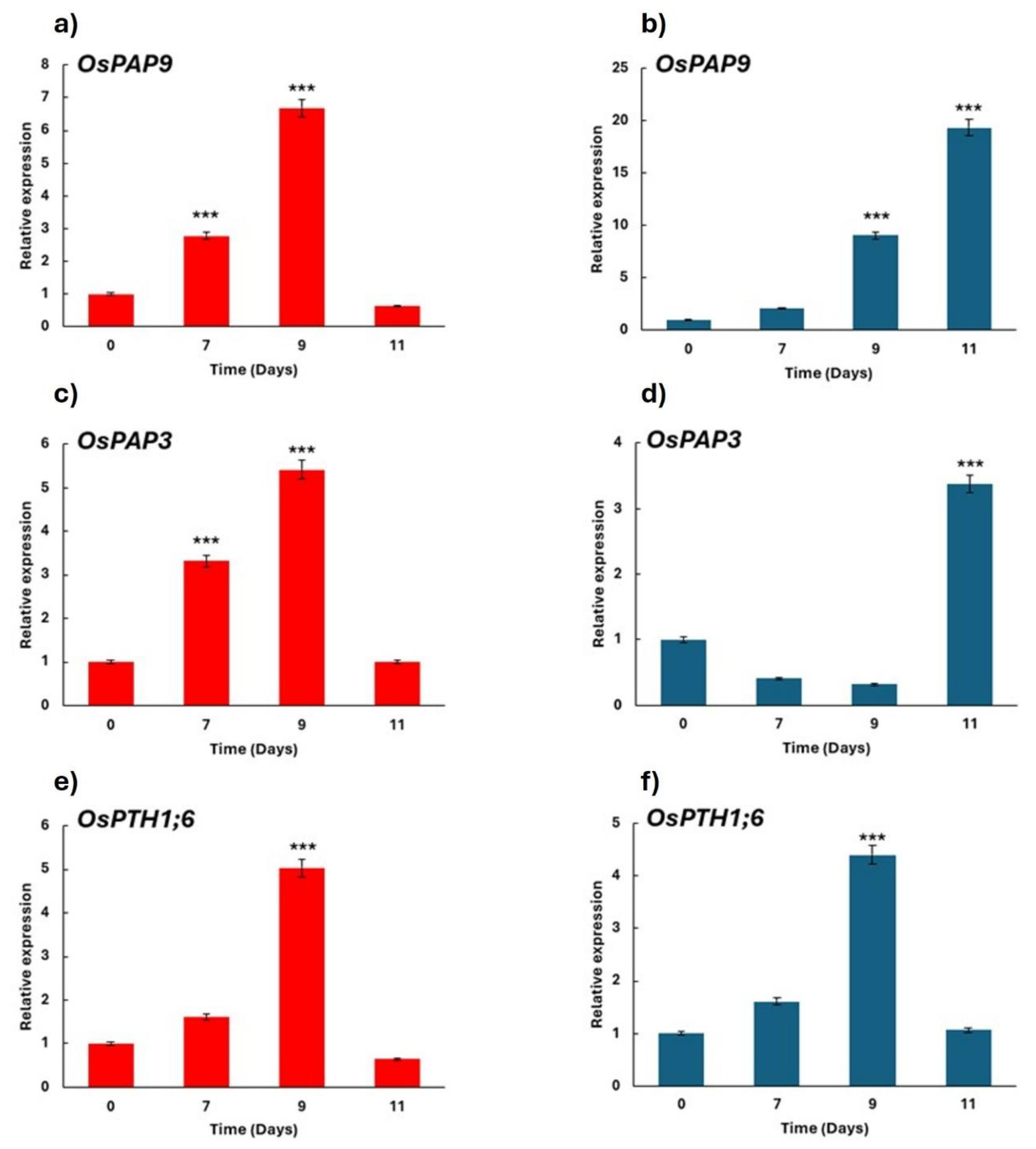

The activation of physiological responses to phosphorus deficiency—such as increased acid phosphatase activity—is regulated at the transcriptional level by specific genes. According to Zhang et al. [

49], only ten

PAP genes in rice are induced under P-deficient conditions. In this study, we examined two of these genes, which showed higher expression levels in plants inoculated with

D. hansenii (Figures 6a–d). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are known to upregulate

PAP genes in symbiosis with rice roots [

50], and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria have also been shown to influence

PAP gene expression in rice [

51]. Additionally, the gene encoding the phosphate transporter analyzed in this study,

OsPTH1;6, was upregulated under both phosphorus-sufficient and deficient conditions (Figures 6), suggesting that this yeast may contribute to enhanced P acquisition in rice.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the yeast D. hansenii demonstrated a clear capacity to promote rice plant growth in calcareous soils, particularly when applied via root immersion. This treatment resulted in significant improvements in physiological parameters such as chlorophyll content (SPAD index), plant height, dry matter accumulation, and grain yield. These benefits were especially evident under non-sterilized soil conditions, suggesting that Dh may act synergistically with the native soil microbiota to enhance plant performance.

In addition to promoting general growth, D. hansenii contributed to an increase in the foliar content of essential micronutrients such as copper, iron, zinc, and manganese—nutrients that are commonly limited in availability in calcareous soils due to their high pH and calcium content. Although the inoculation did not produce a marked increase in phosphorus content in leaf tissue, D. hansenii did significantly enhance the activity of acid phosphatases, a key enzymatic mechanism in phosphorus mobilization. This induction was observed under both phosphorus-sufficient and phosphorus-deficient conditions, indicating that D. hansenii may play a role in improving P availability in the rhizosphere. At the molecular level, Dh upregulated the expression of genes associated with phosphorus acquisition (OsPAP3 and OsPAP9) and phosphorus transport (OsPTH1;6), highlighting its potential influence on nutrient-related gene regulatory networks. These findings collectively support the role of D. hansenii as a plant growth-promoting yeast (PGPY) with significant biotechnological potential. Its ability to thrive under saline and alkaline conditions, along with its demonstrated benefits on plant growth, nutrient uptake, and gene expression, make it a strong candidate for development as a biofertilizer in sustainable rice cultivation strategies.

Figure 1.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on SPAD index in rice plants grown in calcareous soil under controlled greenhouse conditions. Plants were initially maintained in perlite for 15 days, then transferred to 2 L pots containing calcareous soil. The pots were placed in trays with a constant water layer throughout the crop cycle (120 days). SPAD index was recorded every 15 days. a) Temporal evolution of SPAD index during the phenological cycle of rice plants. b) Statistical analysis based on repeated-measures ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are means ± SE (n = 80). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments.

Figure 1.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on SPAD index in rice plants grown in calcareous soil under controlled greenhouse conditions. Plants were initially maintained in perlite for 15 days, then transferred to 2 L pots containing calcareous soil. The pots were placed in trays with a constant water layer throughout the crop cycle (120 days). SPAD index was recorded every 15 days. a) Temporal evolution of SPAD index during the phenological cycle of rice plants. b) Statistical analysis based on repeated-measures ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are means ± SE (n = 80). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments.

Figure 2.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on (a) dry matter percentage and (b) grain yield per plant (g) in rice cultivated in calcareous soil under controlled greenhouse conditions. Experiments were carried out using both sterilized and non-sterilized soils. Treatments included: NSS-Control (non-sterilized soil, control), NSS-Dh Irrigation (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), NSS-Dh Inmersion (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion), SS-Control (sterilized soil, control), SS-Dh Irrigation (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), and SS-Dh Inmersion (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are expressed as means ± standard error (n = 10).

Figure 2.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on (a) dry matter percentage and (b) grain yield per plant (g) in rice cultivated in calcareous soil under controlled greenhouse conditions. Experiments were carried out using both sterilized and non-sterilized soils. Treatments included: NSS-Control (non-sterilized soil, control), NSS-Dh Irrigation (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), NSS-Dh Inmersion (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion), SS-Control (sterilized soil, control), SS-Dh Irrigation (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), and SS-Dh Inmersion (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are expressed as means ± standard error (n = 10).

Figure 3.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on plant height (cm) at 90 days after sowing and treatment application. Experiments were conducted using both sterilized (SS) and non-sterilized calcareous soil (NSS). From left to right, the treatments shown are: Control (C), D. hansenii inoculation via irrigation (Dh Irrigation), and D. hansenii inoculation via root immersion (Dh Inmersion).

Figure 3.

Effect of D. hansenii (Dh) on plant height (cm) at 90 days after sowing and treatment application. Experiments were conducted using both sterilized (SS) and non-sterilized calcareous soil (NSS). From left to right, the treatments shown are: Control (C), D. hansenii inoculation via irrigation (Dh Irrigation), and D. hansenii inoculation via root immersion (Dh Inmersion).

Figure 4.

Micronutrient content of Cu, Fe, Zn, Mn and P in the leaves of rice plants cultivated in calcareous soil and inoculated with the yeast D. hansenii (Dh). Experiments were conducted using both sterilized and non-sterilized calcareous soil. The letters on the X-axis of each graph indicate the different treatments: NSS-Control (non-sterilized soil, control), NSS-Dh Irrigation (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), NSS-Dh Inmersion (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion), SS-Control (sterilized soil, control), SS-Dh Irrigation (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), and SS-Dh Inmersion (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5).

Figure 4.

Micronutrient content of Cu, Fe, Zn, Mn and P in the leaves of rice plants cultivated in calcareous soil and inoculated with the yeast D. hansenii (Dh). Experiments were conducted using both sterilized and non-sterilized calcareous soil. The letters on the X-axis of each graph indicate the different treatments: NSS-Control (non-sterilized soil, control), NSS-Dh Irrigation (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), NSS-Dh Inmersion (non-sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion), SS-Control (sterilized soil, control), SS-Dh Irrigation (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via irrigation), and SS-Dh Inmersion (sterilized soil inoculated with D. hansenii via root immersion). Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences among treatments according to Tukey’s HSD test at p < 0.05. Values are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5).

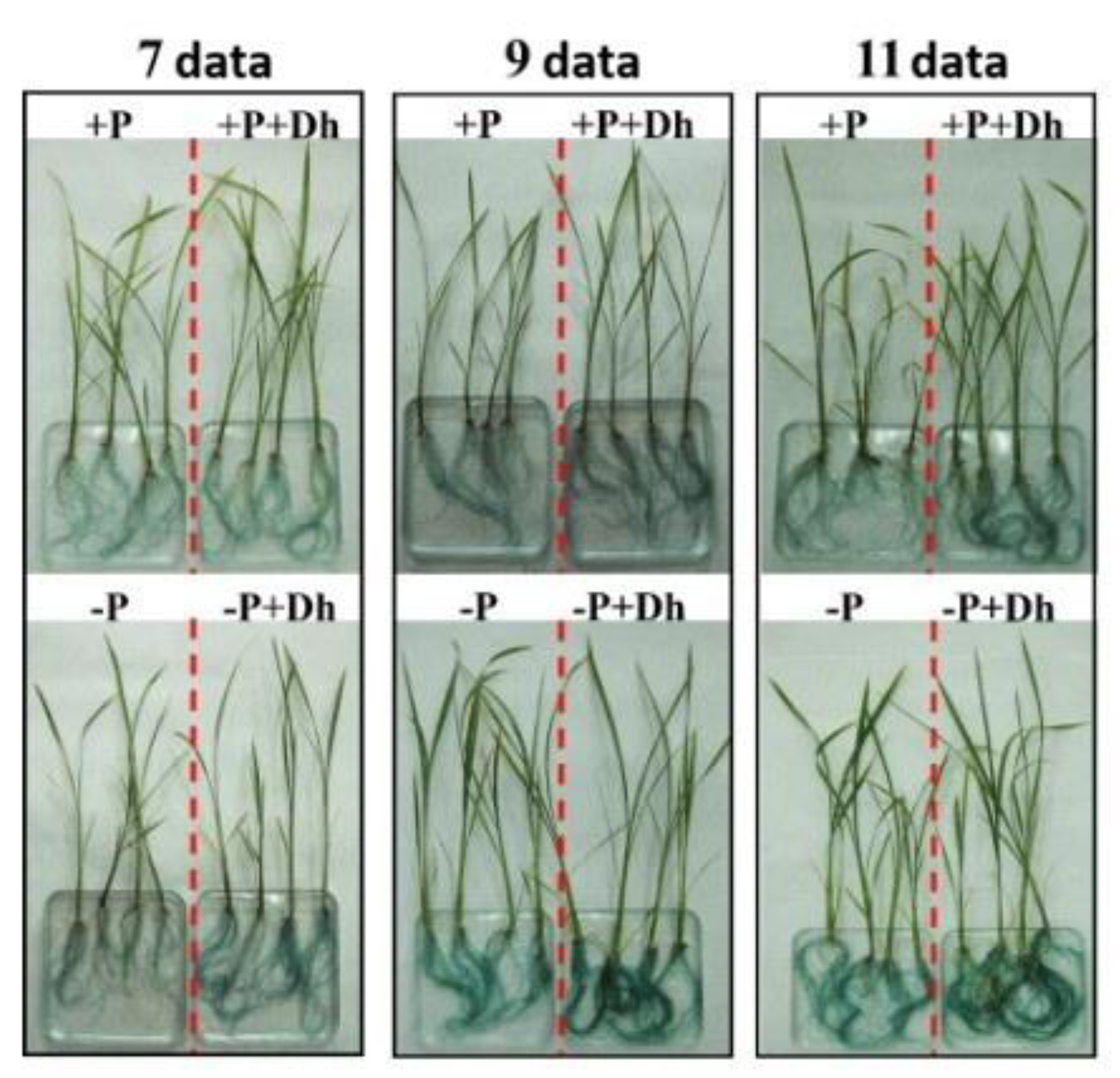

Figure 5.

Effect of the yeast D. hansenii (Dh) on acid phosphatase activity in rice plants. The assays were conducted under hydroponic conditions in a growth chamber. Treatments: +P = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution; +P+Dh = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution plus D. hansenii inoculation; –P = phosphorus-deficient nutrient solution; –P+Dh = phosphorus-deficient nutrient solution plus D. hansenii inoculation. All treatments were applied on the same day. Determinations were carried out at 7, 9, and 11 days after treatment application (data). Six plants were used for acid phosphatase activity assays; however, only two representative plants per treatment are shown to avoid overcrowding the image.

Figure 5.

Effect of the yeast D. hansenii (Dh) on acid phosphatase activity in rice plants. The assays were conducted under hydroponic conditions in a growth chamber. Treatments: +P = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution; +P+Dh = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution plus D. hansenii inoculation; –P = phosphorus-deficient nutrient solution; –P+Dh = phosphorus-deficient nutrient solution plus D. hansenii inoculation. All treatments were applied on the same day. Determinations were carried out at 7, 9, and 11 days after treatment application (data). Six plants were used for acid phosphatase activity assays; however, only two representative plants per treatment are shown to avoid overcrowding the image.

Figure 6.

Effect of the yeast D. hansenii (Dh) on the relative expression of genes associated with acid phosphatase activity for phosphorus acquisition (OsPAP9 and OsPAP3) and phosphorus transport (OsPTH1;6) in rice plant roots. Experiments were conducted under hydroponic conditions in a growth chamber. Determinations were performed at 7, 9, and 11 days after treatment application (data). Treatments: Red = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution, Dark Blue = phosphorus-deficient solution. Data represent mean ± SE of three independent biological replicates and two technical replicates. Asterisks (***) indicate statistically significant differences compared to the control within each time point according to Dunnett’s test (p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Effect of the yeast D. hansenii (Dh) on the relative expression of genes associated with acid phosphatase activity for phosphorus acquisition (OsPAP9 and OsPAP3) and phosphorus transport (OsPTH1;6) in rice plant roots. Experiments were conducted under hydroponic conditions in a growth chamber. Determinations were performed at 7, 9, and 11 days after treatment application (data). Treatments: Red = phosphorus-sufficient nutrient solution, Dark Blue = phosphorus-deficient solution. Data represent mean ± SE of three independent biological replicates and two technical replicates. Asterisks (***) indicate statistically significant differences compared to the control within each time point according to Dunnett’s test (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Physical-chemical properties and phosphorus and iron availability for the plant (average) in the calcareous soil used.

Table 1.

Physical-chemical properties and phosphorus and iron availability for the plant (average) in the calcareous soil used.

| Clay g kg−1

|

Organic Carbon g kg−1 |

CaCO3 g kg−1

|

pH1:2.5 |

EC1:5 dS m−1 |

CEC cmol kg−1

|

POlsen mg kg−1

|

FeDTPA mg kg−1

|

| 370 |

9.3 |

338 |

7.9 |

1.5 |

31.3 |

13.4 |

4.3 |

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Gene |

Forward (5′-3′) |

Reverse (5′-3′) |

| OsPHT1;6 |

CCGCCGCCTCACAAACTGTA |

GAACTGGGCGGTTTTCCTGA |

| OsPAP9 |

ACCTACGTAGAGACAACATCAGGC |

CATATACGTGTTGCCGGTAGTGA |

| OsPAP3 |

TCATACCATGAGGAGTGAGTGATG |

GTCTTCGTTTTGTGAAAATGGC |

| OsACTIN |

TGCATGTAGTACAGTGC CATCCAG |

AATGAGTAACCACGCTCCGTCA |