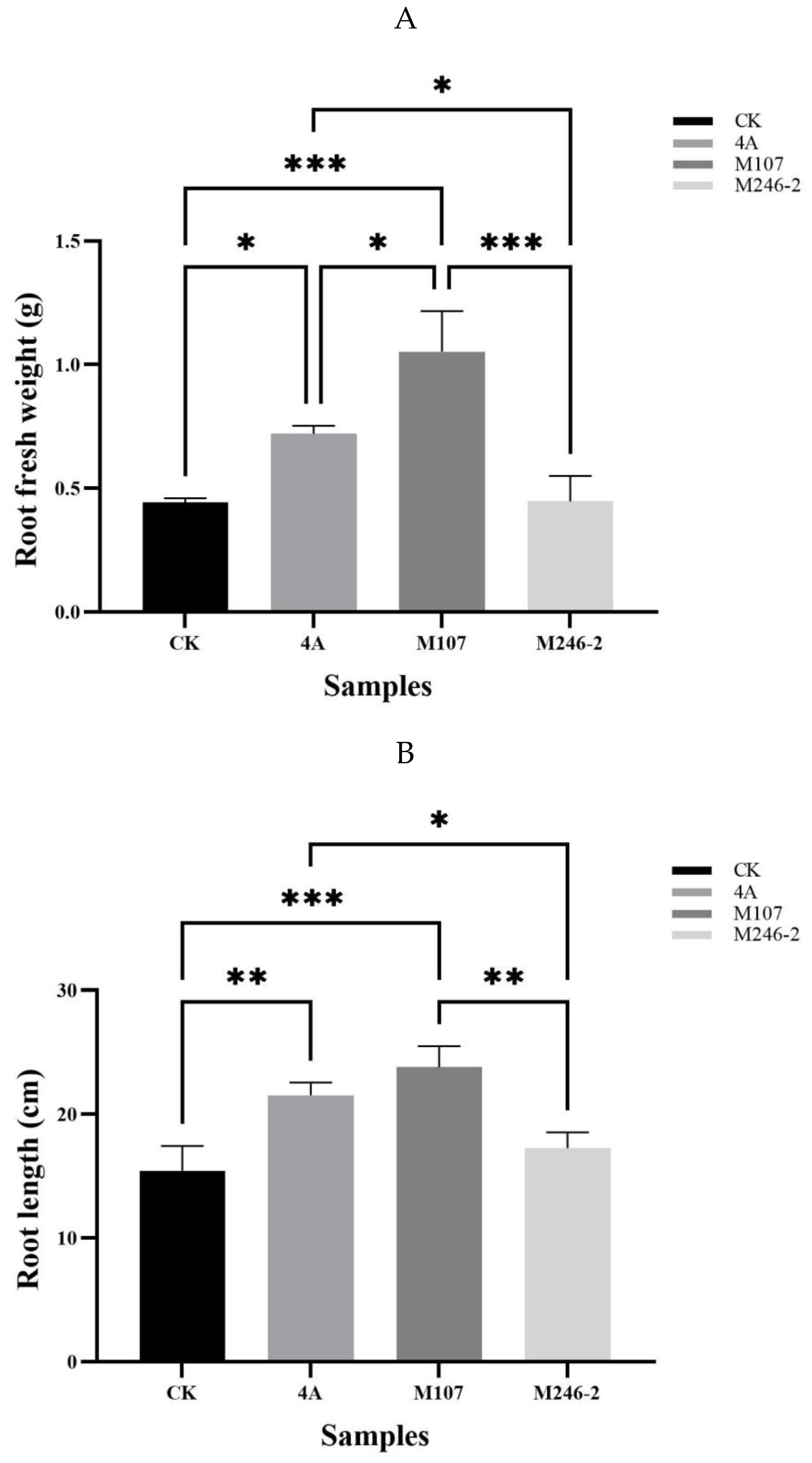

3.3. Biomass Evaluation of the Cucumber Seedlings Treated with Different NFB Bacterial Cells

The root fresh weight in M107 treatment group was the highest, with significant differences compared to the WT GXGL-4A treatment group (

P<0.05), and extremely significant differences compared to the M24-2 and CK treatment groups (

P<0.001). Compared with the CK group, the WT GXGL-4A treatment group showed a significant increase in root fresh weight (

P<0.05), while there was no significant difference in this biomass between the M246-2 and CK groups (

P>0.05)

(Figure 4A). In terms of root length, the NFB treatment groups showed a significant or extremely significant increase compared to the CK group (M246-2-treated,

P<0.05; GXGL-4A-treated,

P<0.01; M107-treated,

P<0.001). There was a significant difference between the M107 treatment group and the GXGL-4A treatment group (

P<0.05), and a highly significant difference between the M107-treated group and the M246-2-treated group (

P<0.01). (

Figure 4B). The treatment with NFB can significantly enhance the height of cucumber seedlings, and there were significant (

P<0.01) or extremely significant differences (

P<0.001) between groups (

Figure 4C). Similarly, NFB fertilization can greatly increase the stem fresh weight of cucumber seedlings (

P<0.001). The M107 treatment group showed a significant improvement compared to the GXGL-4A treatment group (

P<0.01), and an extremely significant enhancement in comparison with the M246-2-treated group (

P<0.001) (

Figure 4D).

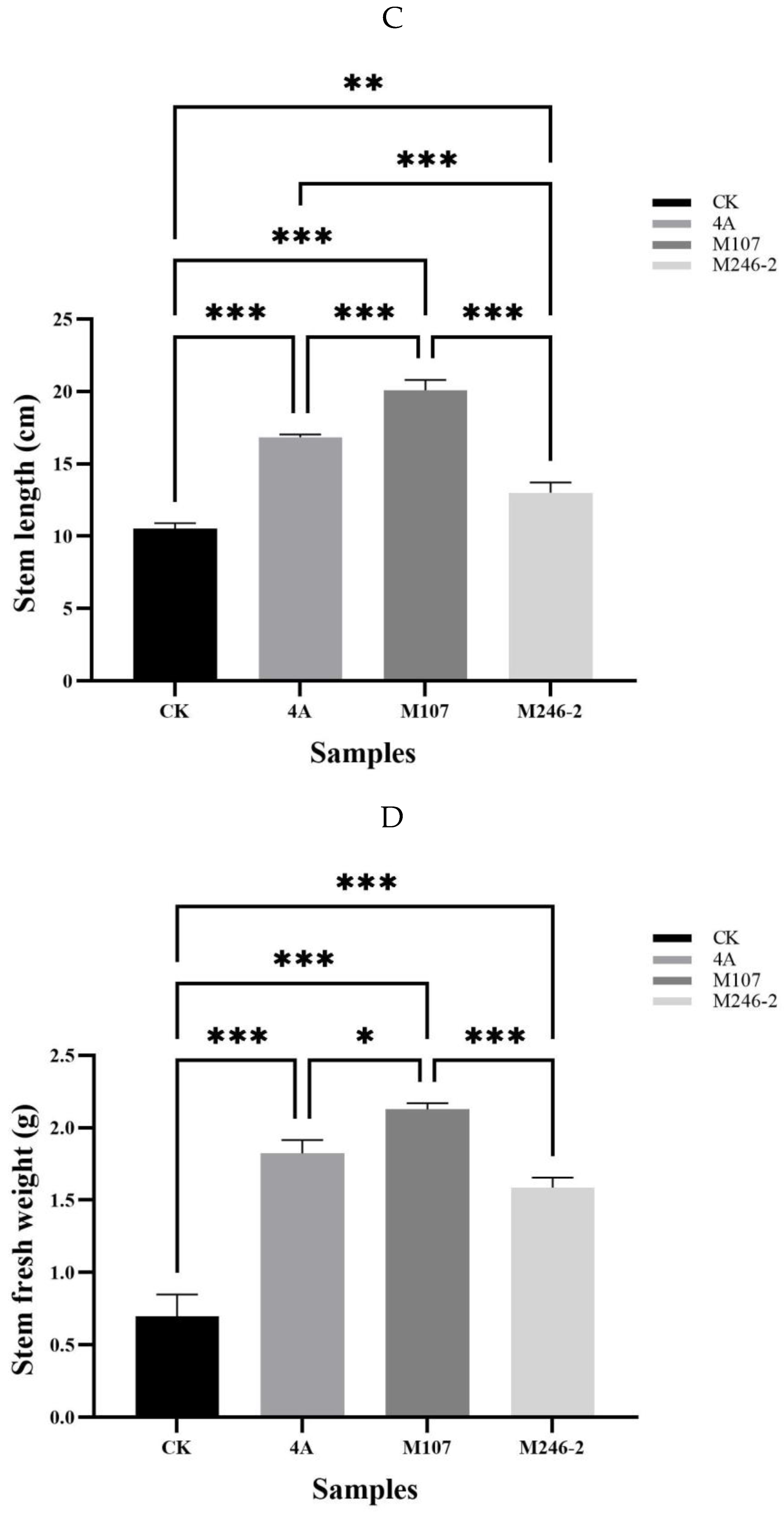

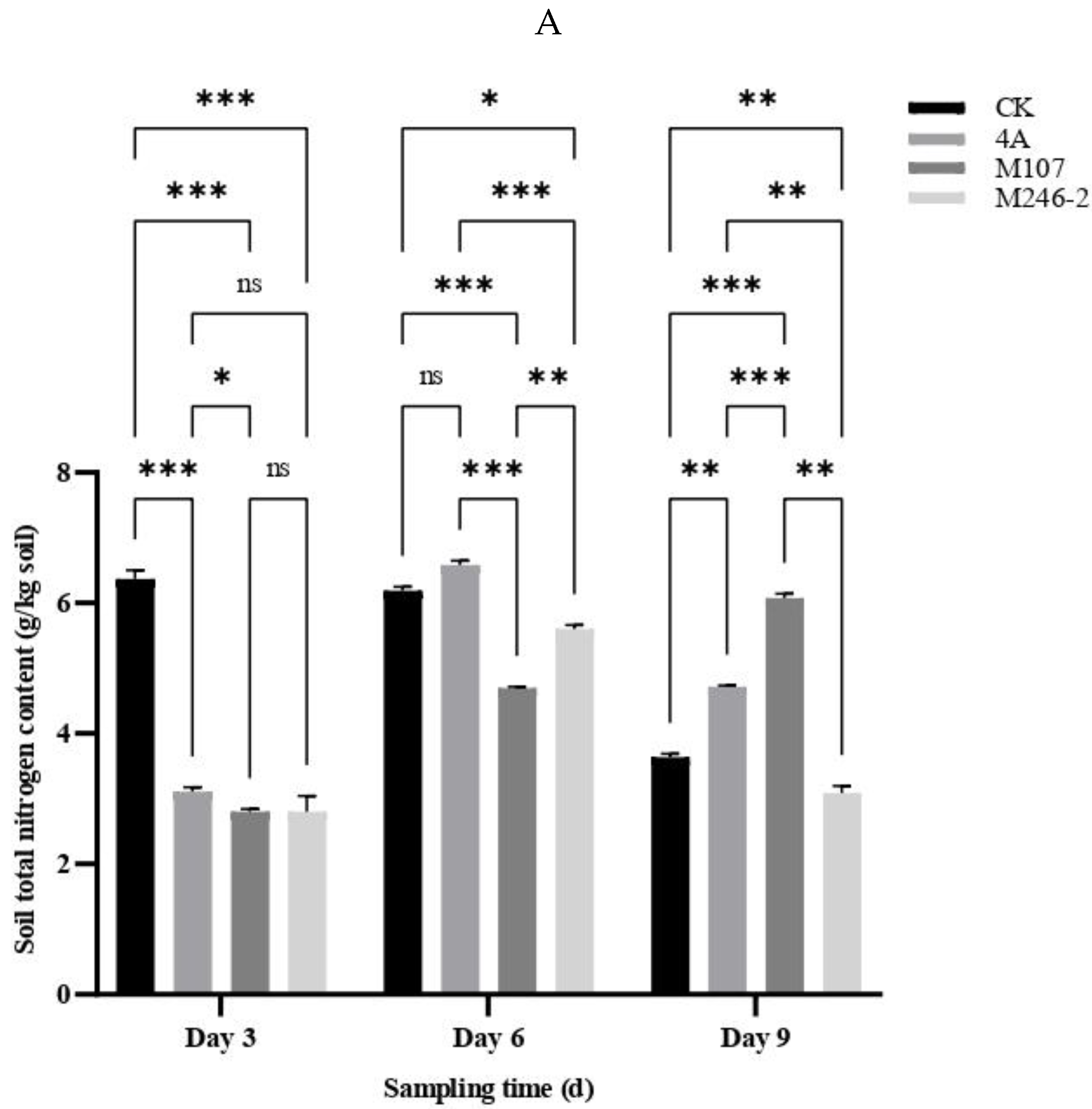

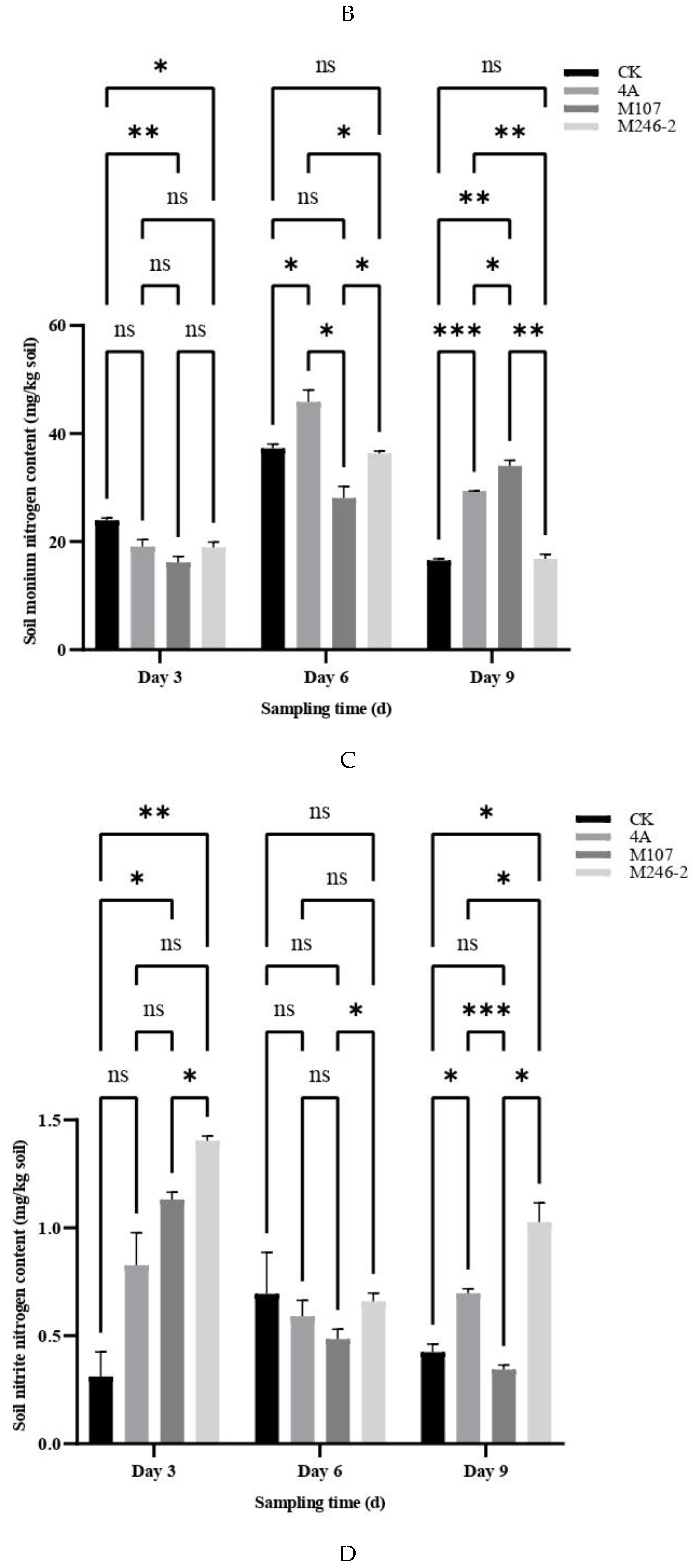

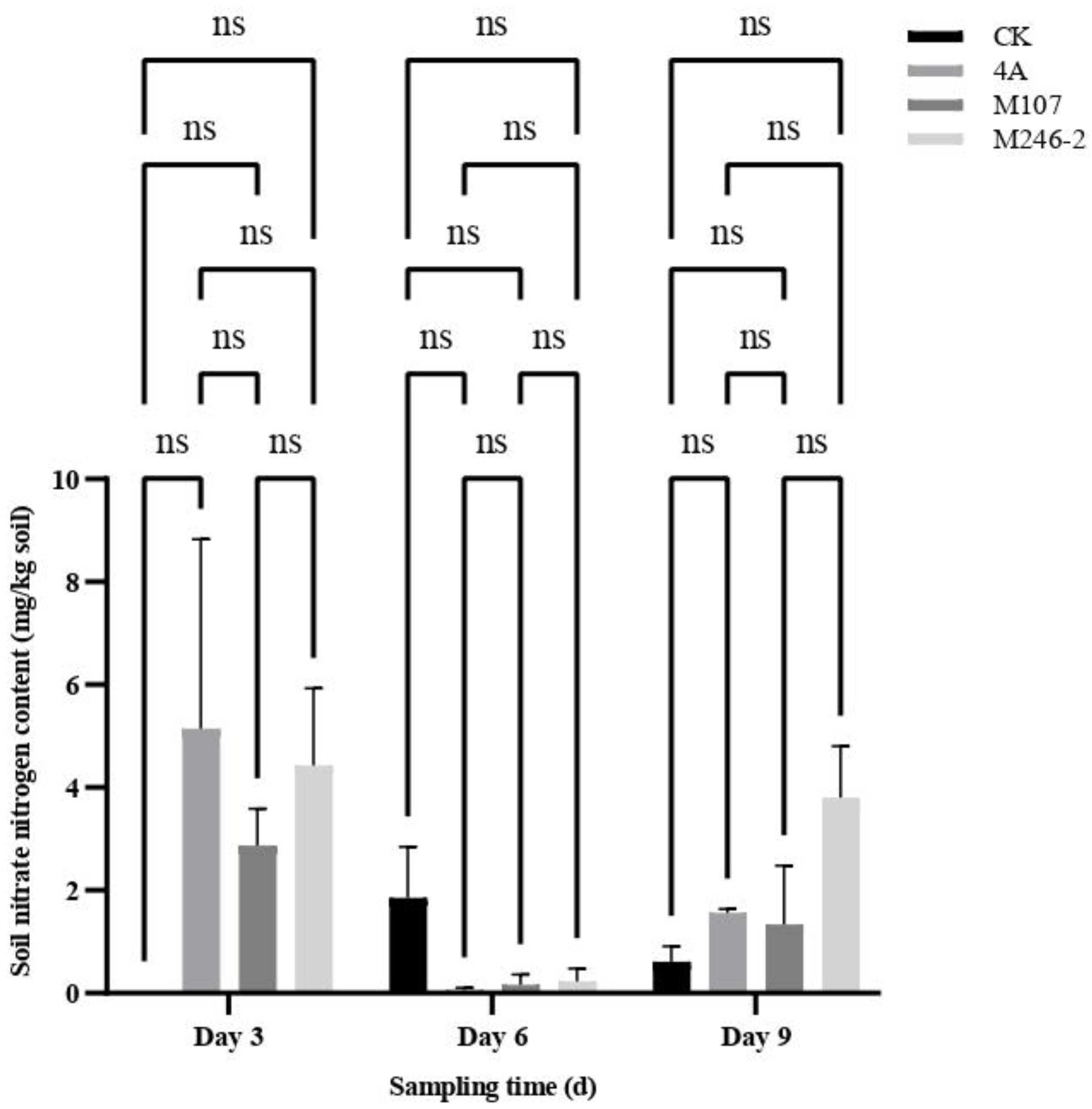

3.4. Nitrogen Contents of the Cucumber Rhizosphere Soil

The contents of total nitrogen (TN), ammonium nitrogen (NH

4+−N) and nitrite nitrogen (NO

2-−N) in the cucumber rhizosphere soil had a significant difference between groups at three sampling time points after NFB fertilization, while the contents of nitrate nitrogen (NO

3-−N) had no significant difference. The results indicated that the application of the NFB strains as biofertilizers improved the soil nitrogen contents. The TN contents of soil in the control group (CK group) gradually decreased, while in the GXGL-4A treatment group (4A group), it increased. The TN contents of soil in the M107 treatment group (M107 group) rose continually during the determination period, and eventually were significantly higher than those of the CK and 4A groups on Day 9. Meanwhile, the TN content of soil in the M246-2 treatment group (M246 group) was significantly lower than those of the other three groups (

P<0.05) (

Figure 5A). The NH

4+−N contents of soil in the groups CK, 4A and M246-2 exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing (

Figure 5B). The NO

3-−N contents in M246-2 group were significantly higher than those of the other three groups on Day 3 and Day 9 (

P<0.05). On Day 3, the soil NO

3-−N content in the CK group was significantly lower than those of the 4A, M107 and M246-2 groups (

P<0.05), suggesting that NFB fertilization can rapidly increase the NO

3-−N contents in the soils of cucumber rhizosphere (

Figure 5C). There were no significant differences in the contents of soil nitrate nitrogen between groups (

Figure 5D).

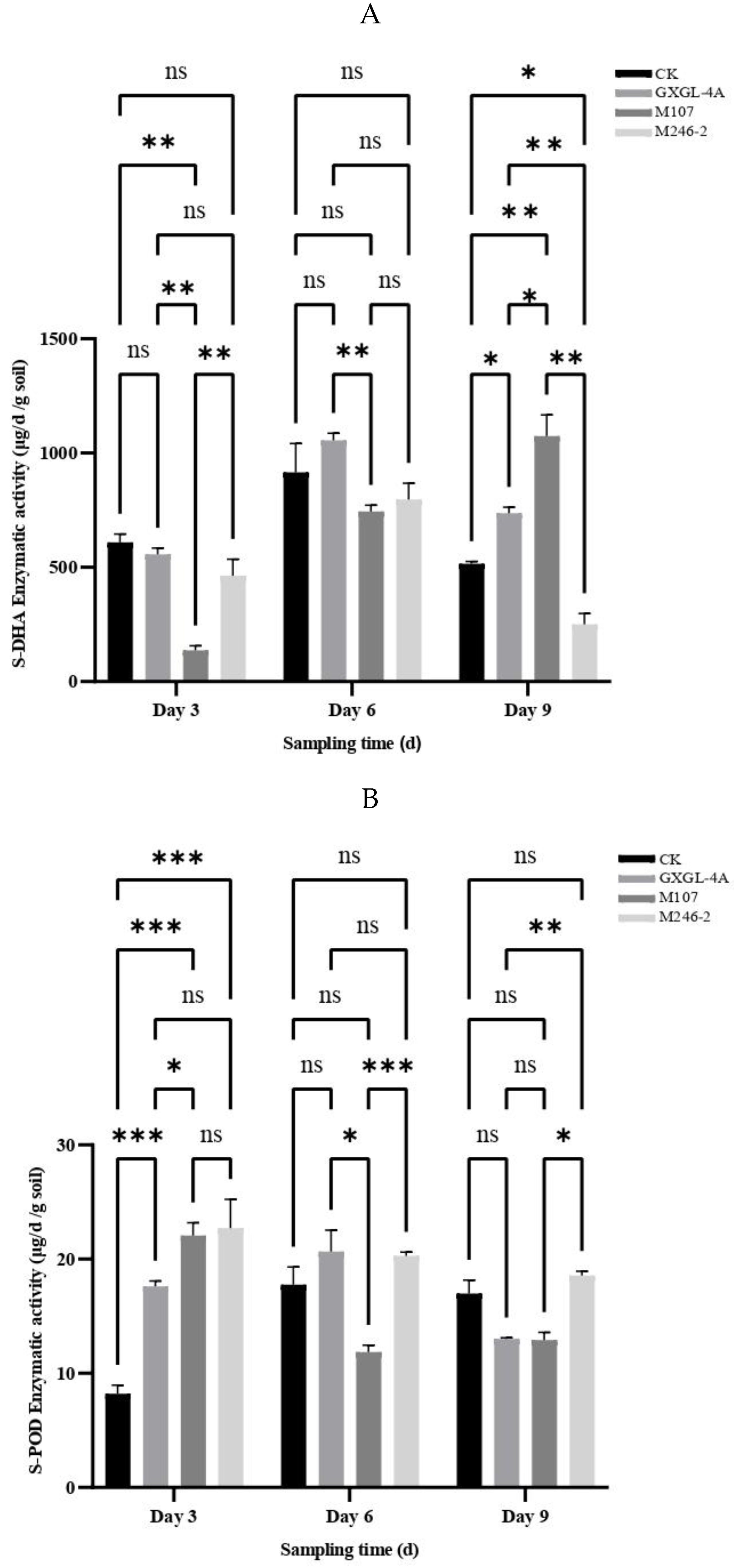

3.5. Enzymatic Activity in the Cucumber Rhizosphere Soil After NFB Fertilization

The enzymatic activities of soil dehydrogenase (S-DHA) and peroxidase (S-POD) were determined. As for S-DHA, on Day 3 after the NFB treatment, the enzymatic activity of M107 treatment group was the lowest, and the differences compared with other groups reached a highly significant level (

P<0.01). Subsequently, the enzyme activity in this group continued to increase, and on Day 6, there was no significant difference compared to the other groups except for still being significantly lower than the GXGL-4A treatment group. On the 9th day after treatment (i.e. Day 9), the enzyme activity in the M107 treatment group was the highest, significantly or extremely significantly higher than other groups (

P<0.01 or

P<0.001)

(Figure 6A). NFB treatment greatly improved the activity of S-POD. On Day 3 after NFB fertilization, the S-POD activity of each NFB treatment group was significantly higher than that of the control group (i.e. CK group) (

P<0.001). Although the M246-2 treatment group had the highest enzyme activity, there was no significant difference compared to the GXGL-4A treatment group and the M107 treatment group (

P>0.05). On Day 6, The difference in S-POD enzyme activity between different NFB treatment groups reached a significant (

P<0.05) or extremely significant level (

P<0.001)

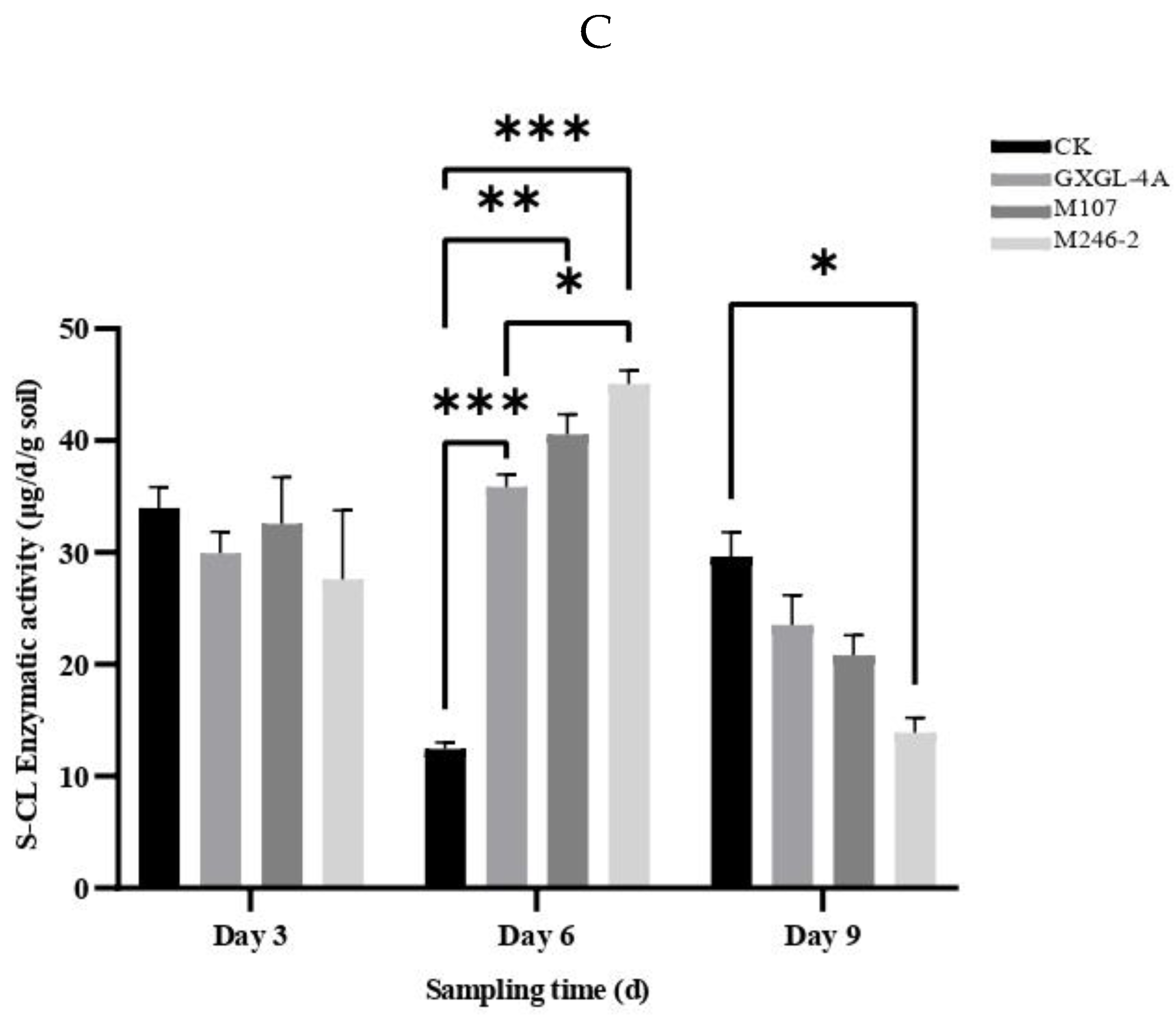

(Figure 6B). On Day 3, the S-CL activities of all groups had no significant difference. On Day 6, the S-CL activities in the GXGL-4A and M107 treatment groups were significantly higher than that in the CK group (

P<0.05). On Day 9, although there was an increase in the M246-2 treatment group, it was still significantly lower than that of the M107 treatment group and maintained a highly significant difference compared to the CK group (

P<0.001). The S-CL activity of CK group exhibited a trend of first decreasing and then increasing throughout the entire experimental period, but the NFB treatment groups showed an opposite trend. Overall, NFB fertilization has a promoting effect on the S-CL activity of cucumber rhizosphere soil, and this effect is particularly distinct on Day 6

(Figure 6C).

3.7. α-Diversity Analysis

As shown in

Table 1, among all treatments on Day 3, the bacterial community richness indices (Sobs, Chao and Ace) and the community diversity index (Shannon) of the three treatment groups (4A, M107 and M246-2) were significantly higher than those of the CK group, indicating that the bacterial community abundance and diversity significantly increased after NFB fertilization (

P<0.05). On Day 6, the bacterial community richness in the M107 treatment group was significantly higher than that in the 4A treatment group (

P<0.05), and there was no significant difference in bacterial community diversity among groups (

P>0.05). On Day 9, the bacterial community richness and community diversity in M107 treatment group were significantly lower than those in the CK and M246-2 groups (

P<0.05), but had no significant difference compared with the 4A-treated group (

P>0.05). With the extension of sampling time, the Sobs, Chao and Ace indices of the CK group gradually increased, suggesting that the richness of the bacterial communities in this group continually enhanced. The community richness and diversity of the 4A and M246-2 groups decreased first, and then increased, while that of the M107 group decreased gradually. Fertilization with the M107 bacterial cells could significantly reduce the abundance and diversity of bacterial communities in the cucumber rhizosphere soil.

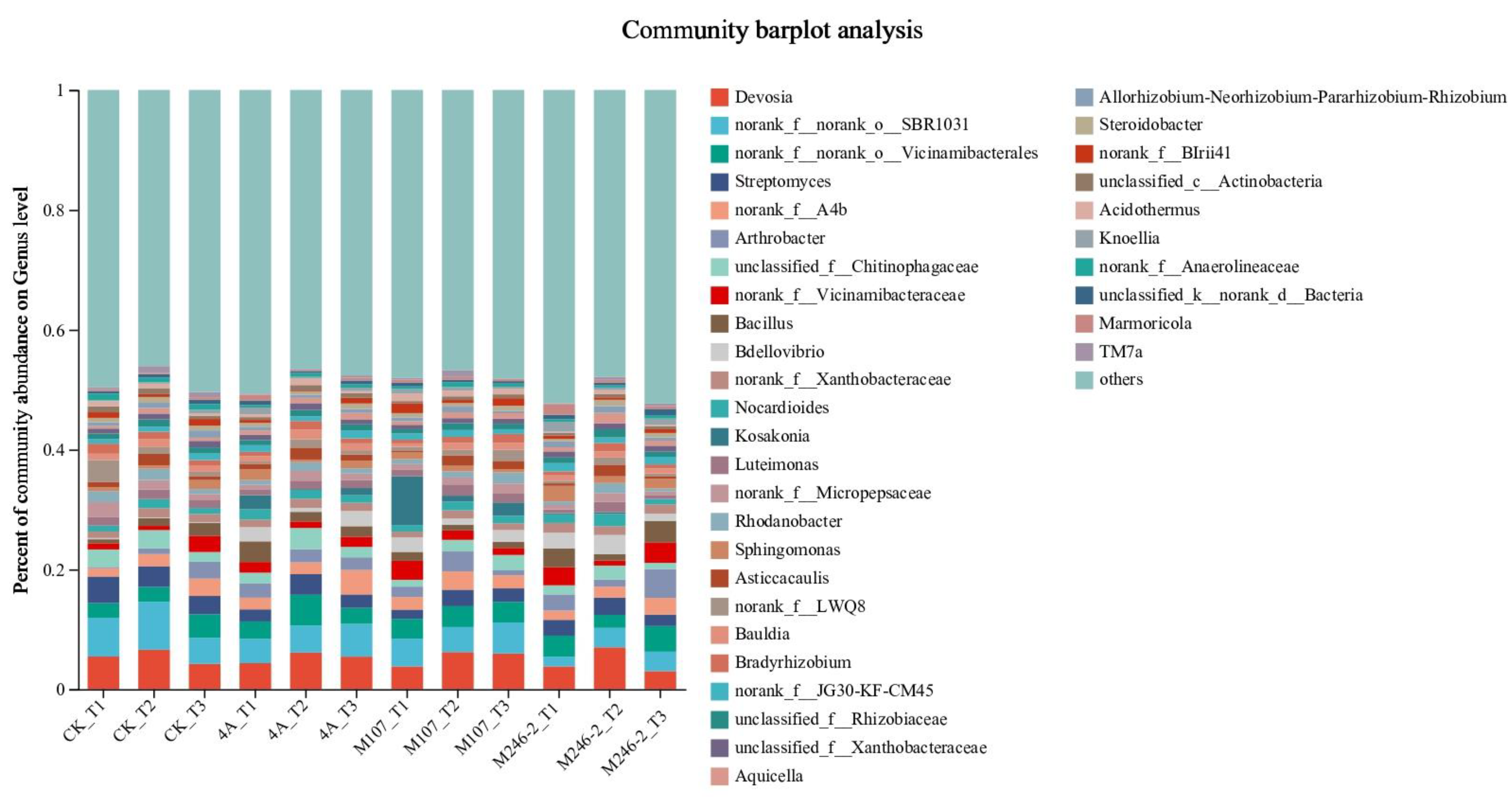

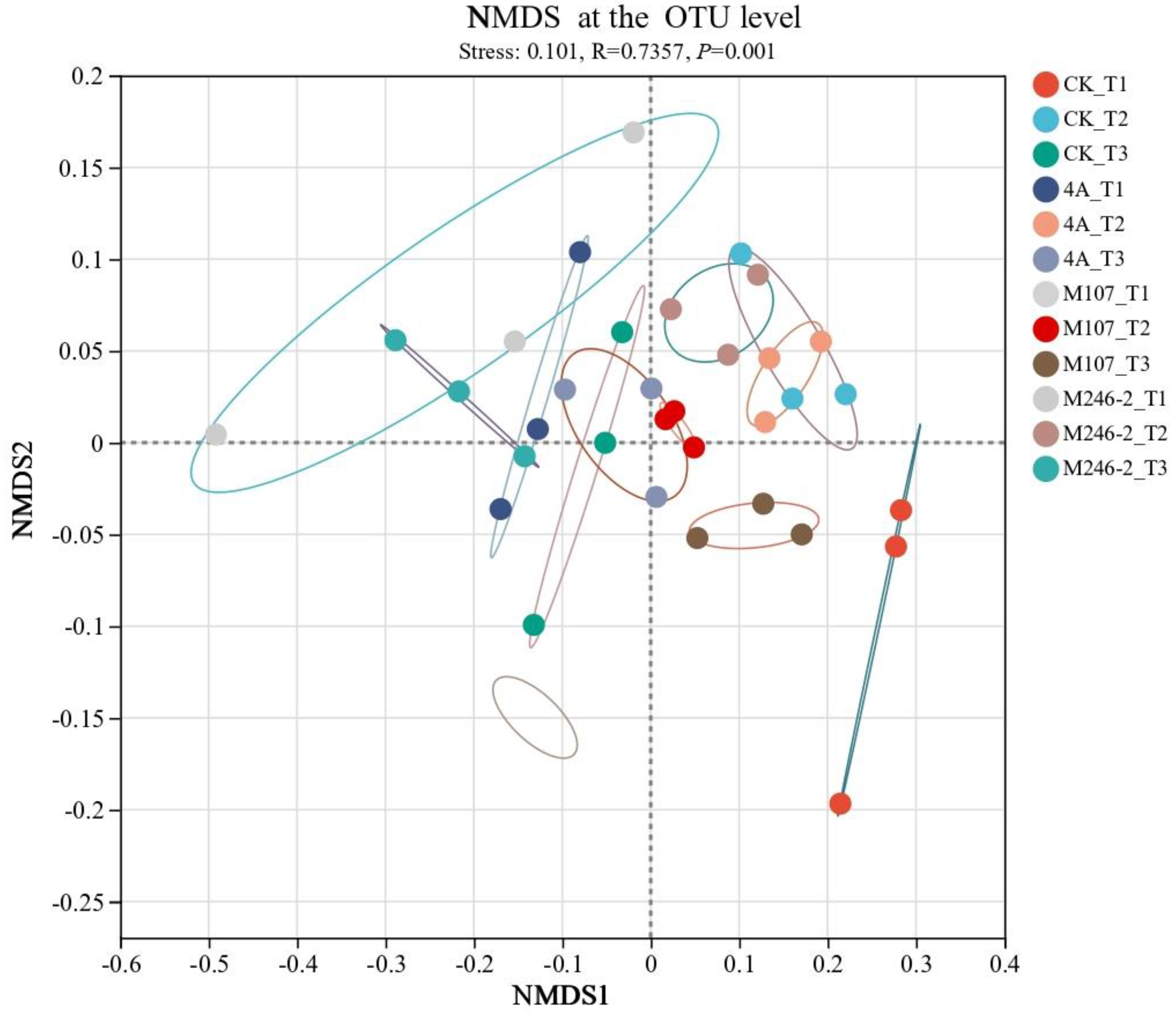

3.9. Difference Analysis of the Bacterial Community Structure in Cucumber Rhizosphere Soil

The difference in the soil bacterial community structure in cucumber rhizosphere was conducted by non-metric multidimensional scale (NMDS) analysis at the OTU level. The results revealed that the bacterial community structure in cucumber rhizosphere soil significantly altered after the application of NFB strains. Grouping of all the tested soil samples based on sampling time points was correct and reliable (stress: 0.101, R=0.7357 and

P=0.001). The compositions of bacterial communities in the soils on Day 9 after GXGL-4A application varied significantly compared with that on Day 6 and Day 3. In the M107 group, the bacterial population structure modified on Day 3 after fertilization compared to that on Day 6 and Day 9 after fertilization (

Figure 9).

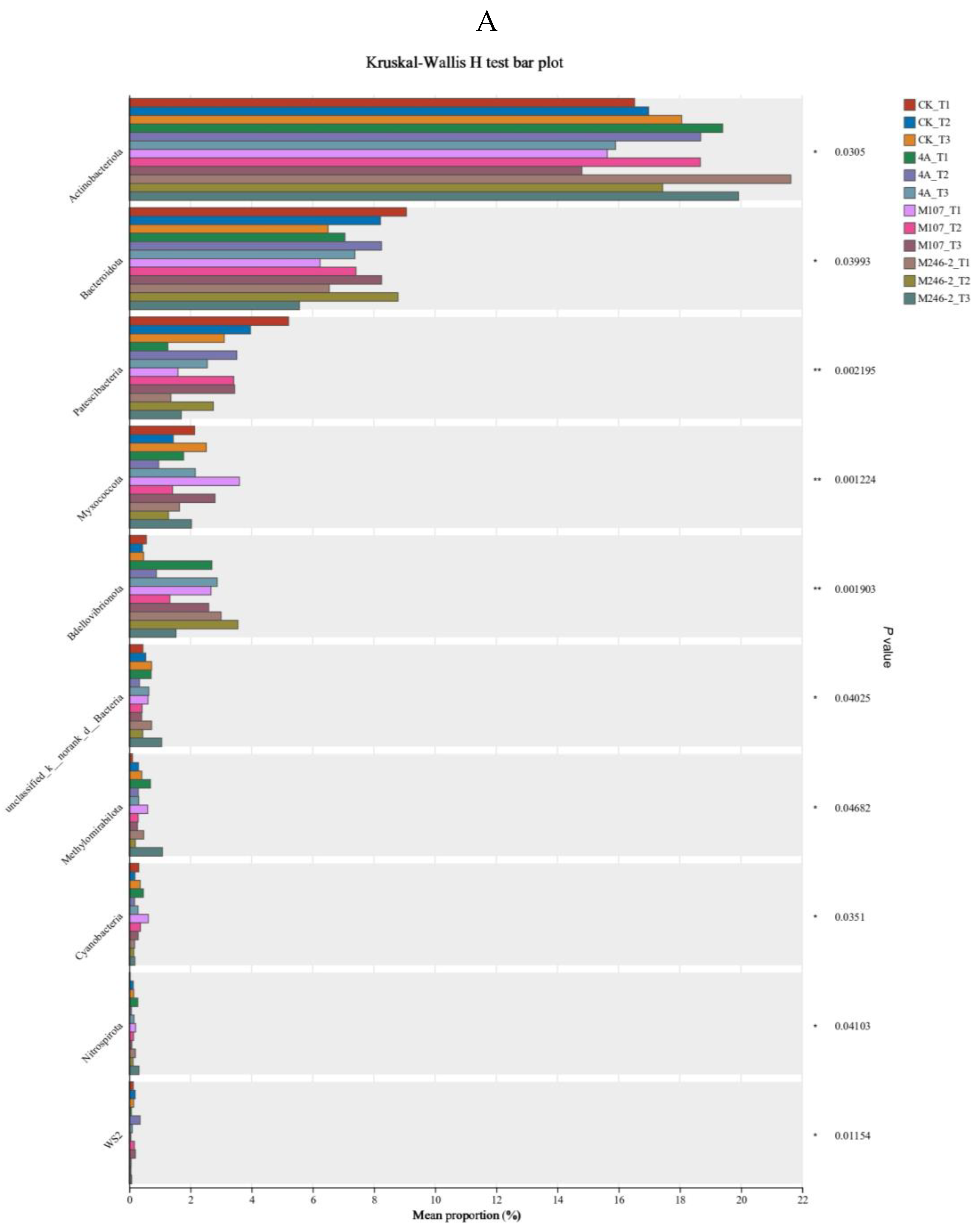

There were significant differences in the composition and structure of microbiota among different soil groups. The results revealed that Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Patescibacteria and Myxococcota were the dominant phyla of soil samples. Streptomyces, norank_f__A4b, Arthrobacter, unclassified_f__Chitinophagaceae and norank_f__Vicinamibacteraceae were the dominant genera in soil samples (

Figure 10A).

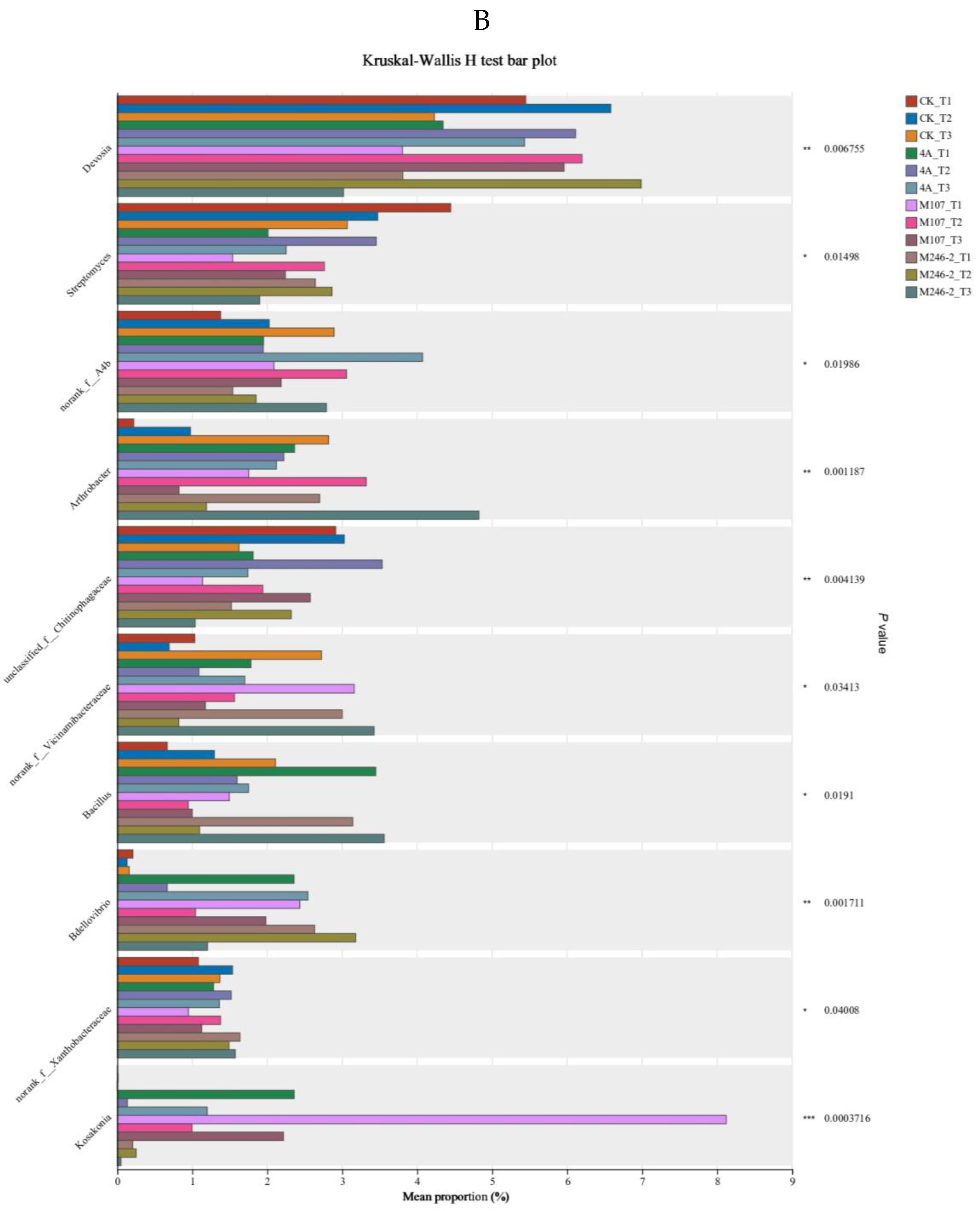

Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to evaluate the relative abundance difference of the Kosakonia genus in the GXGL-4A, M107 and M246-2 treatment groups through multi-species difference analysis (

Figure 10B). The relative abundance of Kosakonia in GXGL-4A- and M107-treated groups was statistically extremely significant (

P<0.01), while no significant difference was found between GXGL-4A and M246-2 treated groups on Day 3 and Day 6 after fertilization. On Day 9, the relative abundance of Kosakonia in GXGL-4A and M246-2 treatment groups was statistically significant (

P<0.01), but there was no significant difference between the GXGL-4A and M107 treatment groups.

The abundance of Kosakonia in each group was analyzed. The result indicated that the abundance of the genus Kosakonia varied in three sampling time points after the application of NFB bacterial cells. On Day 3, the abundance of Kosakonia in the M107 treatment group was always higher than that in the GXGL-4A treatment group, and the relative abundance of the M246-2 treatment group was the lowest. The abundance ratio of GXGL-4A treatment group was 2.359%, while that of M107 treatment group was 8.123% (Figure S1A). Before Day 6, the abundance of Kosakonia in the M107 treatment group was significantly higher than that in 4A and M246-2 groups (P<0.05) (Figure S1B). On Day 9, the abundance of Kosakonia in M246-2 group was significantly lower than that in GXGL-4A treatment group (P<0.05), and in the GXGL-4A treatment group, the abundance of Kosakonia increased first, and then decreased (Figure S1C).

3.10. Environmental Factor Correlation Analysis

The effect of NFB fertilization on the rhizosphere soil bacterial flora was evaluated using 16S rRNA gene high-throughput sequencing. The results indicated that the application of NFB not only affected the content of nitrogen and enzyme activity in the cucumber rhizosphere soil, but also significantly reshaped the microbial community composition and diversity. Through environmental factor correlation analysis, at the genus level, it was found that GXGL-4A and mutant strains M107 and M246-2 affect the abundance and composition of microbial communities by altering the total nitrogen (TN) level of the soil. The alteration in TN content is considered a primary and important factor. Among the top fifty dominant genera in terms of abundance, only 9 genera such as Hephaestia, Hyphomicrobium, and Steridobacterium showed no correlation with all the tested environmental factors, while the abundance of the remaining 41 genera was significantly correlated with multiple environmental factors. Total nitrogen (TN), soil dehydrogenase (S-DHA), and soil ammonium nitrogen (NH4+−N) are the three key environmental factors, which show significant or extremely significant correlations with the abundance of most dominant genera in the rhizosphere soil. Secondly, nitrate nitrogen (NO3-−N) and nitrite nitrogen (NO2-−N) are important environmental factors that are significantly or extremely significantly correlated with the abundance of many dominant genera, and are mostly negatively correlated. The activities of soil peroxidase (S-POD) and cellulase (S-CL) had negligible effect on the abundance of soil dominant microbial flora. In particular, the activity of S-CL was significantly positively correlated with the species abundance of only three genera Pseudolabrys, Luteimonas and Nocardioides in the top fifty genera (Figure S2).

3.12. Discussion

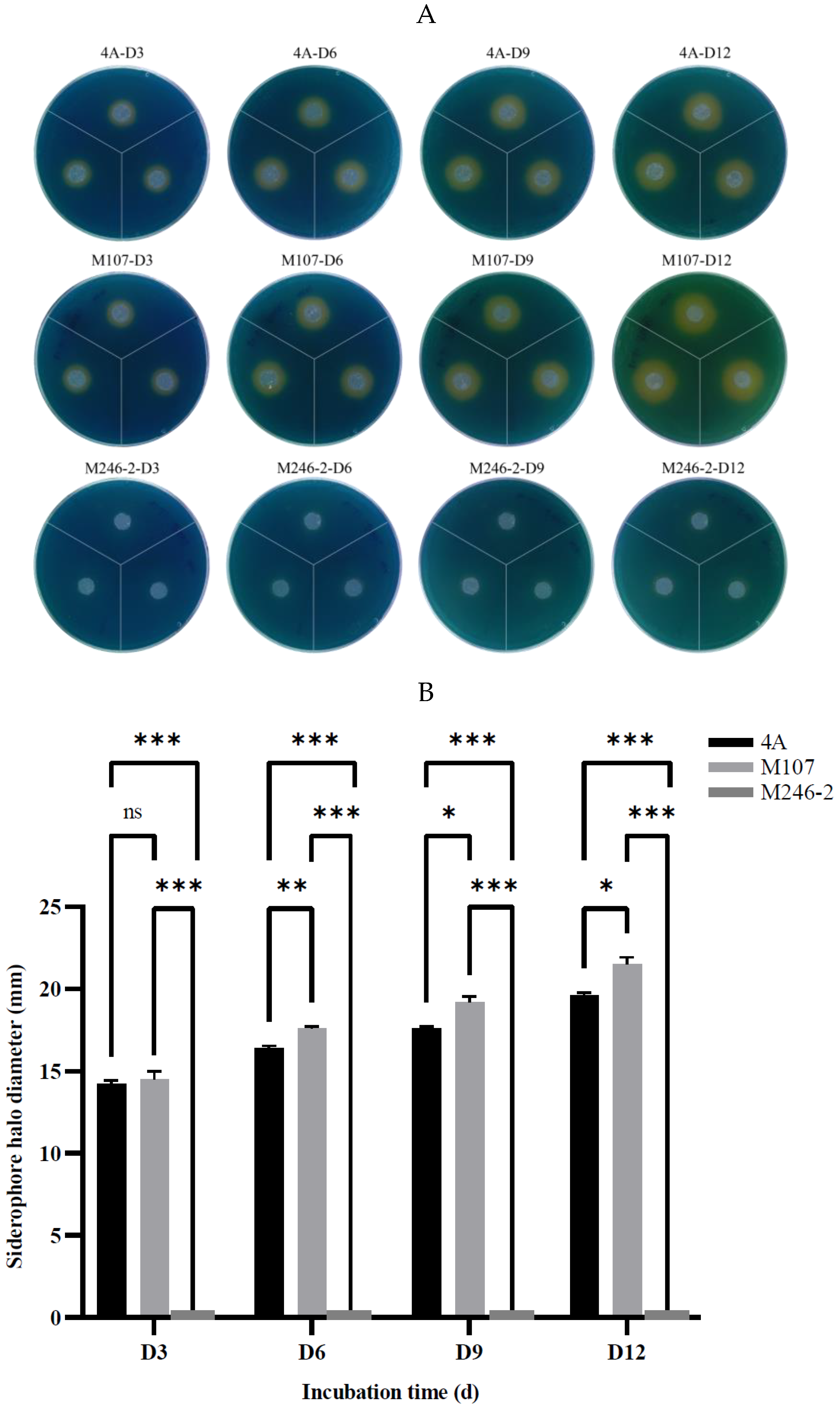

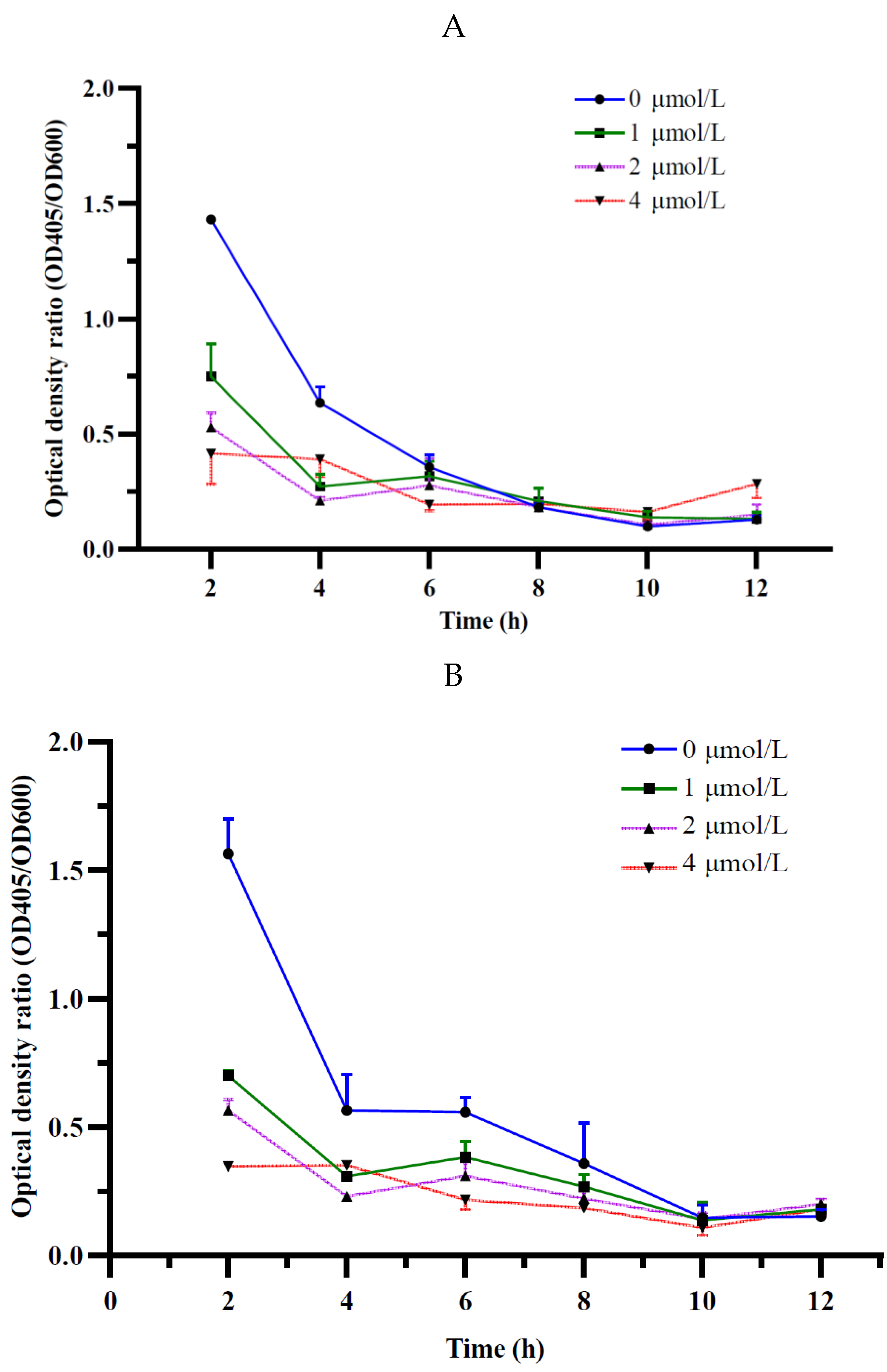

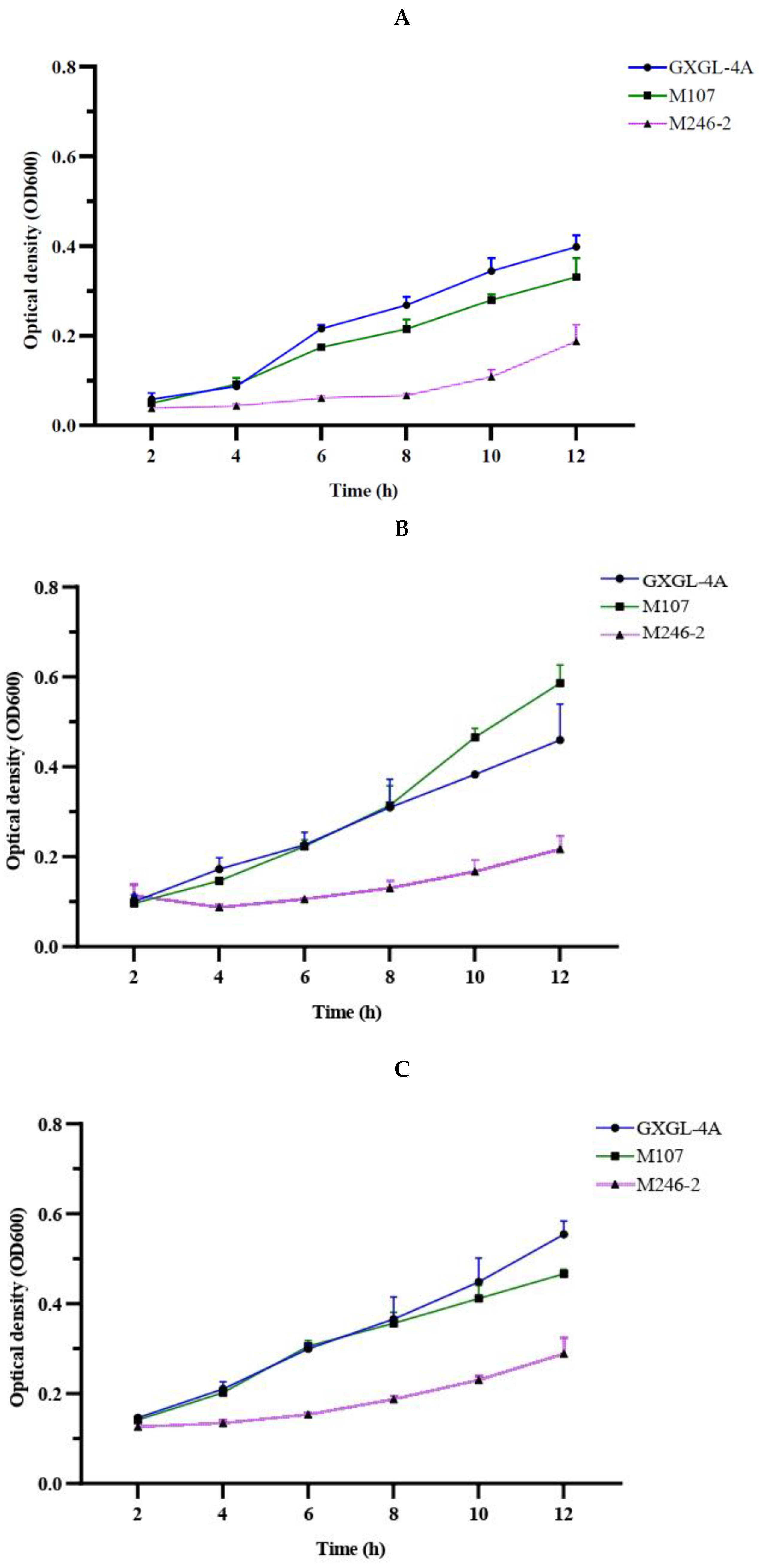

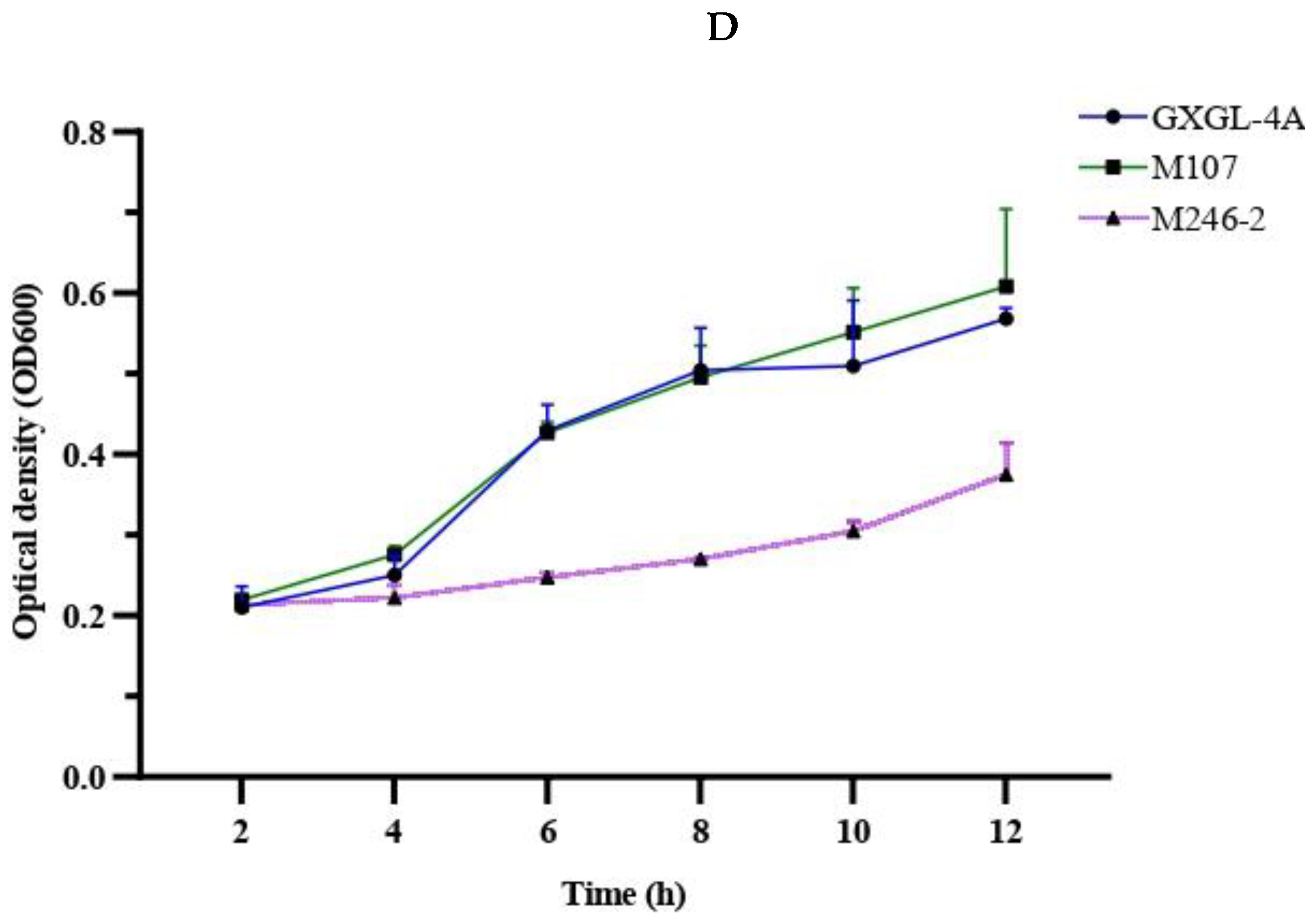

A siderophore-deficient mutant M246-2 was obtained from the Tn5 mutant library of K. radicincitans GXGL-4A using CAS assay method in this study, and except for it, the WT GXGL-4A and high siderophore-yielding mutant M107 showed strong CAS reactivity, indicative of siderophore production. Siderophores produced by these NFB strains are essential for iron acquisition, and consequently modulate the relative growth rates of bacterial cells. In general, the siderophore-deficient mutant M246-2 grew the slowest in media supplied with limited iron (0-4 µmol/L) compared to other strains. Biofertilizers have been widely used in agricultural production because they can effectively promote plant growth. Reasonable addition of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) can also regulate soil nutrients and prevent plant diseases by hindering the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria [23]. It has been confirmed that biological fertilizer can affect the rhizosphere microbial community and plant growth, but the effect of NFB as biofertilizer on the bacterial community of cucumber rhizosphere soil is unclear [24]. Currently, the development of high-throughput sequencing technology and bioinformatics technology makes it possible to study the bacterial community structure quickly and easily in different habitats. The 16S rRNA gene sequencing is a common tool in microbiome investigation and it is still being improved to increase the sensitivity and applicability in environmental bacterial population diversity analysis, which is driving the rapid progress of modern agricultural research [25].

Previous study reported that Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus licheniformis treatments increased the α-diversity of maize rhizosphere soil bacterial community, and different fertilization treatments affected the abundance and diversity of soil bacterial community [26]. Our study results were consistent with this report. The application of NFB strains significantly modified the bacterial community in the rhizosphere soil of cucumber. There was a significant difference in α-diversity between the GXGL-4A and M107 treatment groups (P<0.05), indicating that the synthesis capability of siderophore by the NFB GXGL-4A may affect the reshaping of the bacterial community in cucumber rhizosphere soils by a short-term fertilization. However, there was no significant difference in soil bacterial community between the GXGL-4A and M246-2 treatment groups. Fertilization with the mutant M107 significantly reduced the abundance and diversity of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil compared to the other groups.

There were a higher abundance in the genera Arthrobacter, Bacillus and Kosakonia in the rhizosphere soil after the applications of GXGL-4A、M107 and M246-2 bacterial cells. Many bacterial strains in the genus Arthrobacter can degrade nitroglycerin, benzene derivatives, polycyclic aromatic compounds, halogenated alcohols, halogenated hydrocarbons, N-heterocyclic compounds, pesticides and herbicides [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Thus, NFB fertilization theoretically could promote plant growth through the way of degradation of toxic compounds in soil.

A variety of strains in the genus of Kosakonia can increase plant growth activity by producing auxin, siderophore and increasing phosphorus [33]. In our study, the relative abundance of Kosakonia was different in diverse groups. At the same sampling time point, the relative abundance of Kosakonia in M07 group was significantly higher than that in GXGL-4A-treated group, and similarly the abundance of Kosakonia in GXGL-4A treatment group was significantly higher than that in M246-2 fertilization group (P<0.05). Therefore, we speculated that the activity of siderophore production is closely related to the survival status of a certain bacterium in soil.

Soil enzymatic activity reflects the strength of soil substance transformation (e.g., C, N and P), and is suitable for evaluating the effect of fertilization. S-CL and S-DHA enzymatic activities can well tag soil fertility [34]. In this work, the enzymatic activities of S-CL and S-DHA in cucumber rhizosphere soil were measured at three sampling time points (i.e., Day 3, Day 6, and Day 9 after NFB fertilization). Soil-cellulase (S-CL) is an important enzyme in the carbon cycle of soil [35,36]. In general, the S-CL enzyme activity of the three NFB treatment groups showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. On Day 6 after NFB treatment, the S-CL enzyme activity was the highest, and the three S-CL enzyme activities of NFB treatment groups were significantly higher than that of the CK group (P>0.05).These results indicated that after the application of NFB, the S-CL enzyme activity in the rhizosphere soil was greatly increased, which accelerated the decomposition of cellulose in the soil to provide sufficient carbon source for the absorption and utilization of cucumber seedlings, which was conducive to promoting their vegetative growth. S-DHA activity has been used as a sensitive indicator to monitor respiratory and biochemical processes in soil microbial communities [37]. In the present study, the enzymatic activities of GXGL-4A and M107 treatment groups increased sharply on Day 3 and Day 9 after treatment of NFB bacteria respectively, which was significantly higher than that of the other two groups, suggesting that soil respiration strength was significantly enhanced, and the nitrogen cycling in soil was improved. After the treatment by the bacterial cells of siderophore-producing mutants, the tested soil enzyme activities significantly varied, which affecting the nitrogen cycle of cucumber rhizosphere soil. These modifications in soil enzyme activity are a short-term trend, and we consider that this is a vital component of complex regulation of soil microenvironment.

Soil inorganic nitrogen content has a direct impact on crop growth yield and quality, so it is regarded as an evaluation index for nutrient management in the field [38]. In this study, the three NFB biofertilizers could significantly increase the contents of TN, NH4+−N, and NO2-−N in cucumber rhizosphere soils in a short term. One mechanism is that NFB bacteria may help host plants produce root secretions that, in turn, absorb beneficial bacterial communities, thereby increasing the levels of dissolved nutrients in the soil. In addition, a growing body of research indicates that the microbial composition is largely determined by environmental factors [39,40]. The differences in siderophore-producing abilities of the NFB mutants affect the iron absorption capabilities of bacteria themselves and the rhizosphere soil microbiota, modulate the utilization efficiency of soil microorganisms for nitrogen and iron nutrients, and thus reshape the rhizosphere soil bacterial communities.