John Searle (1984) argues that if one claims that he is talking about mind, four things must be discussed: Subjectivity, causality, intentionality, and consciousness. Here we consider rationality as a major indicator of subjectivity. In artificial intelligence, we assume as our working hypothesis that mind can be embodied in AI; call it artificial mind. In Yang (2025), we discussed artificial consciousness. In this paper, we are going have a complete discussion of the four properties.

1. Intentionality as Fermions

In business or diplomacy, a letter of intent must have some contents. In philosophy, intentionality is used to characterize mental acts, which cannot be null; hence, intentionality is contentive. Some authors use the terms intentionality and consciousness almost interchangeably (Dennett, 1991). This is a rough usage in cognitive science. Nevertheless, in philosophy of mind, there is a distinction between the two concepts (Aquila, 1977). As Aquila said, Menong regards consciousness as a kind of irreducible directedness, being through intentional contents, towards some possible object without requiring the existence of that possible object. Note the difference that the consciousness only goes through some intentional contents but the intention always carries certain contents. In this sense, we say, consciousness can be treated as contentless while intentionality is contentive. In mathematical terms, consciousness can be characterized as an isovector, which has the direction with zero length, while intention is a vector with both direction and nonzero length.

The contentive property of intentionality is important from functional perspectives in modeling. In Yang (2025b), we have the following postulates and working definitions,

Postulate 1. An artificial intelligence task carries the AI-task Charge. The AI dynamics is a sourced analysis, and hereby the source is the task charge.

Postulate 2. We assume as our working hypothesis that machine intelligence exists. Furthermore, we assume artificial intelligence consists of human intelligence and machine intelligence.

Definition 1. Artificial Demand as the intelligence demand (: human component) and as the intelligence supply . For an any given task , we have,

, and .

Now, the question is: How do the intelligence terms connect to a task , and further, what does an “AI task” mean?

Consider a testing item prepared for the standard education test, say, the SAT. Before using this item in a real test, it is only an item lying in the item bank. Only when the item is given to examinees, who intend to solve this item, it becomes a task. Thus, the task is an intentional function of item.

In other words, the intention is a function connecting a task and its corresponding item. It can be rewritten as:

.

From the above we can see that artificial intension in AI is contentive. In philosophy of mind, intention is characterized as a mental action. In other words, artificial intention is charged. Thus, the artificial intelligence can be redefined as

By the above analyses, we can have,

Proposition 1. Artificial intention is contentive. In terms of physics, it is massive.

Proposition 2. As it argued earlier, artificial consciousness is contentless. In terms of physics, it is massless.

Now, we are getting close to the definitions which can be described in terms of statistic physics,

Definition 4. Artificial intention is massive, so it is classified as an artificial Fermion.

Definition 5. Artificial consciousness is massless, so that it is classified as artificial Boson.

Why are Definitions 4 and 5 sensitive and significant to artificial intelligence? Because there is a basic theoretic issue behind it. In statistic physics, fermions are regarded as material particles, such as electrons and positrons. Fermions have spin of ½. Bosons are regarded as force carriers, such as photon and gluon. Bosons have spin of 1. This is also an issue in statistical artificial intelligence.

2. Causality and World-Line

The causality of artificial intelligence can be perfectly characterized by the world-line through the light cone in special theory of relativity. Our descriptions of the world-line follow Penrose (2004).

The mathematical background of special relativity is the Minkowski space, also known as the four-dimensional spacetime. In Minkowski spacetime, each point stands for an event. It introduces the notion of interval as shown below,

where, the gauge

,

is the absolute time, and

is the speed of consciousness (in a three-dimensional space). The term

can be regarded as the energy term.

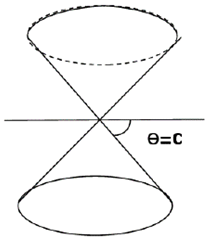

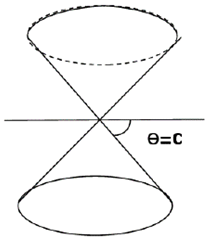

By applying the notion of interval, we can introduce the notion of light cone with absolute time, drawn in the figure below.

Any events within the cone, i.e., , are called timelike events; any events outside the cone, i.e., , are called spacelike events; and any events on the surface of the cone, i.e., , are called null events.

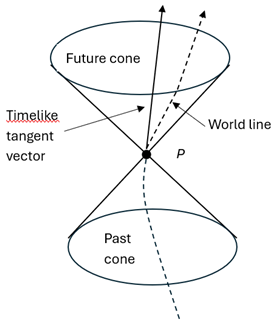

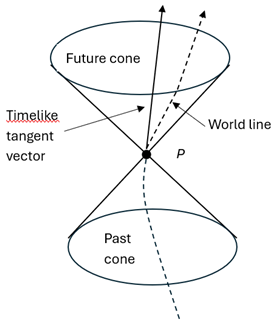

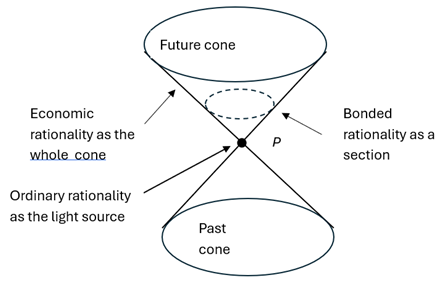

Note that the light cone has two parts to it, the past cone and the future cone. We can think of the past cone as representing the history of a flash of light that is imploding on p, so that all the light converges simultaneously at one event p. Correspondingly, the future cone represents the history of a flash of light of an explosion taking place at the event p. This is shown in the figure (Penrose, 2004, p403) below.

In the light cone, the dashed line represents the path from the past cone, through the present event p, to the future cone. In special theory of relativity, world lines reflect causality. In physics, causality describes the relationship between events where one event (the cause) directly influences or leads to another event (the effect).

The AI-causality along a world line is clear. Assume an agent is trying to solve a task; this is the present event, represented as p. The early training and learning processes for this agent is represented by the events along the world line in the past cone. These past events have effects on the events along the world line in the future cone, which reflects the processes of solving a task by the agent. This is the causality from the early training and learning of an agent to its performance in solving a task.

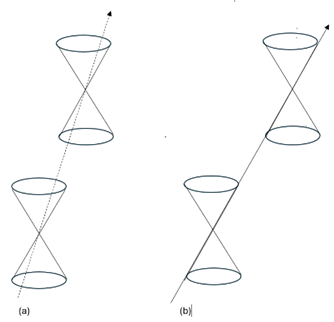

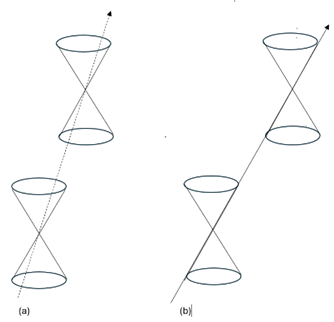

As we argued in Yang (2025) and earlier in the present paper, artificial intention is contentive (massive) and the artificial consciousness is contentless (massless); the following figures show their relations to the world line.

Figure (a) shows the case of artificial intention. The world line of the intention, which is massive, is a time-like curve through the inside of the cone. Figure (b) shows the case of artificial consciousness. The world line of consciousness, which is massless, have tangents on the null cones, which move through the surface events of the light cone.

3. Subjectivity and Agent Differences

People have a conflict regarding toward artificial intelligence. On one hand, they want to create more and more powerful artificial agents; on the other hand, they fear if artificial agents can develop super-subjectivity they would lose human control. Both of these mentalities are likely to be illusory views about subjectivity.

When the author gives lectures in the classroom, the students are required to take lecture notes, which are collected weekly. For the same lecture, using the same language (English), individual students write different lecture notes. This example tells us that mind is individually oriented. People share many things, but they don’t share their minds. The same can be said about artificial agents. We assume as a working hypothesis below,

Postulate 3. Artificial subjectivities exist, which is not observed as a collection but reflected by agent-differences.

Definition 6. For an artificial agent, if she can engage a task individually and intend (behaviorally or mentally) to solve that task in a particular way that is different from other agents or other type agents, this agent has acquired subjectivity.

Individual differences of agents are shown as two timelike world lines in the cone below

4. Illumination and Proper Consciousness Cone

In Yang (2025), we discussed the individualized momentum cone based on proper consciousness. In order to show the whole picture of the special relativistic model of mind, we repeat this part here. The light varies in the degree of its illumination, the same is the artificial consciousness. There are individual differences of artificial agents. For different agents and for the same task the degree of illumination of consciousness can be stronger or weaker. This difference is characterized by the notion of proper consciousness, akin to the proper time (or clock time) in special theory of relativity. Let be the proper consciousness for an agent , the momentum is defined as follows,

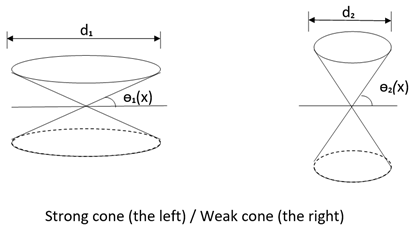

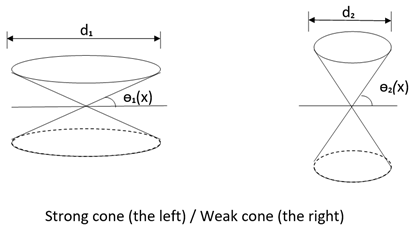

For any individual agent, it has its proper consciousness cone. Based on the degree of different illuminations of the artificial consciousness, we characterize the individual cones as strong cones or weak cones (see the figures below).

The cone can become wide and flat or tall and slender. Drawing a horizontal line through the apex of the upper and lower cones, the angle between this line and the cone is called the cone's phase. The flatter the cone, the smaller the phase; the taller the cone, the larger the phase. The width of the cone's top opening is called the "capacity degree". The mechanism of cone shape change is that the stronger the proper consciousness, the smaller the phase, and the higher the capacity degree, forming a strong cone. Conversely, the weaker the proper consciousness, the larger the phase, and the lower the capacity degree, forming a weak cone (see the diagram above). It can be seen that the proper consciousness is proportional to the capacity degree. In short, for an individual agent, the weaker the illumination of being conscious of an item, the lower their psychological capacity to solve it, and vice versa.

5. Artificial Rationality

Rationality is a major indicator of subjectivity. Rationality theory is particularly important to artificial intelligence for a special reason. Artificial intelligence as a domain has three perspectives: technology, science, and business. Rationality is not only concerned with the business part, but also embodied in the technology and science parts; so that it is called artificial rationality. Rationalities can be defined in the framework of decision theory. This section is largely based on Yang (2022/2024). From gauge field theoretic perspectives, artificial rationality of agents can be analyzed at three levels, which are introduced below.

First, the global level is about artificial economic rationality, which has four conditions: full knowledge, full capacity, full scale, and full logic. These are briefly described as follows.

Condition 1: Full Knowledge. In a decision structure, there can be numerous choices, each choice can lead to many outcomes, and each outcome has its own desirability and feasibility. All this information is describable, resulting in a vast amount of knowledge. Regardless of how massive the information is, the economic rational agent knows all of it. This is a purely syntactic requirement.

Condition 2: Full Capacity. The utility function of a decision problem can be quite complex, and the computational demands can be substantial. However, regardless of the computational complexity required by the utility semantics, the economic rational agent has the full capacity to perform the calculations. This is a purely semantic requirement.

Condition 3: Full Scale. The economic rational agent ensures that the utility function is a one-to-one correspondence mapping between choices and their mathematical expectations. Thus, the economic rational agent can establish a strict full order among the set of choices. This is a requirement by the representation theorem of decision theory.

Condition 4: Full Logic. Psychology of decision making tells us that people are sensitive to the way choices are presented, known as the framing effect. Full logic requires that the economic rational agent is not influenced by the framing effect and makes judgments about logically equivalent choices without differentiation; in other words, being indifferent to any logically equivalent contents.

It is not hard to imagine that any particular artificial agents who meet all four requirements of the economic rational agent will eventually amass all market wealth. A test question is: How many economic rational men are there in the market? Clearly, if there are two or more economic rational men competing, it will lead to an economic rationality paradox. Alternatively, if there is only one economic rational agent, this individual will eventually capture all the market wealth, which is evidently not a realistic scenario for any particular artificial agent. There is only one thing that can satisfy the four conditions simultaneously: the whole domain of artificial intelligence.

Any individual market agents can only be a member of it but not a part of it. Individual market agents are belonging to the market, but not included as part of the market (Yang, 2022/2024). To mix up the membership and the inclusion will meet Russel paradox. In other words, for the global subjectivity, all the individual agent subjectivities are in the symmetric position. This is called the global symmetry of AI-world.

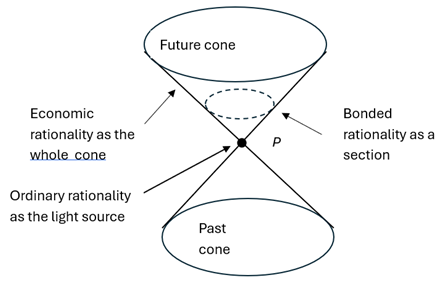

From the geometric perspective, economic rationality is characterized by the whole light cone.

Second, the local level is about the artificial bounded rationality. At the local level, individual agent subjectivities are compatible with each other. Here the subjectivity becomes a function of individual subjectivities. The local gauge symmetry can be achieved through appropriate gauge transformations (Zee, 2003). In AI (LLMs), artificial agents need to make decisions. For example, the embedding procedure is a decision-making process. For a given transformer and for a verbal task, all the verbal components are transformed into a vector space. Then, these vectors will be embedded to 1 or 0. But which vectors should be embedded to 1 and which to 0, the agent needs to set up a threshold and makes decisions. This is exactly what the businessmen are supposed to do.

Bounded rationality was originally proposed by H. Simon (1979) who is considered as one of the founding fathers of artificial intelligence and a Nobel laurate in economic sciences (1978). A great deal of empirical research was done by D. Kahneman (Nobel laurate, 2002) and others. The Nobel lecture by Kahneman was titled: Advances Under the Umbrella of Bounded Rationality.

From a semantic perspective, businessmen (also called agents or managers) are not only realistic but also wise. Agents understand that there is no free lunch and one cannot take all the advantages. They know that achieving something requires a cost, with both gains and losses, and it is important to complete the transaction as fairly as possible. This represents a form of practical rationality. The key concept in managerial semantics is the "threshold." Managers weigh the pros and cons and then set a threshold. If all consequences generated by a choice exceed the set threshold, they prefer that choice and embed it to 1; otherwise, embed it to 0. If the resulting preferred choice is not unique, they may increase the threshold until a unique preferred choice is obtained, thereby solving the decision problem. Again, this is exactly what an artificial agent does. At the local level, the local gauge symmetry among artificial agents can be achieved by gauge transformations in gauge field theory.

From the geometric perspective, the bounded rationality is characterized by a section of the light cone.

The third level is about artificial ordinary rationality. Ordinary rationality is a principled theory (Yang, 2022/2024), which holds eight principles including: subjective certainty, high selectivity, taking null action, sunk cost, hesitation, face, emotion, and better life. These principles are construed into artificial agents and embodied in their behavior. There are three key meta properties, summarized as follows:

Property 1: The state of ordinary rationality is a grand state of minimum energy. Quantum mechanics posits that vacuum is not empty but contains minimum energy. This is known as a vacuum with a non-zero expectation value. This is a metaproperty shared by artificial agents.

Property 2: Ordinary rational agent is an inertial system with zero spin. Ordinary agents keep their basic capacities as an inertial system just as the vacuum is an inertial system in quantum field theory. T. D. Lee (1988) once said that an inertial system that spins zero and breaks all symmetries.

Property 3: Ordinary rational agent is a "degenerate state." This is a remarkable observation, as it fits the description so precisely that it is hard to imagine otherwise. In physics, a particle in a degenerate state is one where the state of the particle can’t be isolated and observed alone. Observing this particle state will also involve observing other related particle states; thus, its eigenstates have a spectrum of values.

These three fundamental properties correspond to the three basic properties of the Higgs field in theoretical physics: the minimum energy vacuum state, the inertial system, and the degenerate state. Therefore, the Higgs field is a model of ordinary rationality.

From a geometric perspective, ordinary rationality is characterized by the light source point. We can see that economic rationality, bounded rationality, and ordinary rationality can be characterized by one cone as shown below.

6. Conclusion Remarks

We make the following conclusion remarks.

Remark 1. This paper proposes a special relativistic model of the mind as well as rationality and artificial intelligence. The model is based the geometric characters of light cone. It characterizes ten properties: consciousness, intentionality, causality, subjectivity, individualized proper strong momentum as well as proper weak momentum, economic rationality, bounded rationality, ordinary rationality, and agents lost their social identity.

Remark 2. Mind is a category; its objects are different minds, human or artificial, real or imaginative, and strong or weak. Mind is a structure; human mind and artificial mind may share this structure but they are not identical. When the mind is treated as a monad, all the objects that are mental can be mapped (morphism) to the monad.

Remark 3. Artificial mind can be seen as an adjoint operator on human mind. We predict that many human-mindlike artificial structures in AI world will be discovered. Human mind provides a useful map for us to find these AI-structures.

Remark 4. Mind is individually oriented. There are individual differences between individual minds and between artificial agents. Mind is a variable ranging over different kinds of minds, from human minds to AI-agents’ artificial minds. From a gauge field theoretic viewpoint, minds are local fields.

Remark 5. There were two debates are related to this paper (Searle, 1997), one is between Searle and Penrose, and another between Searle and Dennett. The present author is with all three. Thus, the approach we are taking could be called the “Artificial Searle-Penrose-Dennett”.

References

- Aquila, R. (1977). Intentionality: A Study of Mental Acts. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Dennett, D. (1991). Consciousness Explained. Little Brown Co.

- Lee, T. D. (1988). Symmetries, Asymmetries, and the World of Particles, University of Washington Press.

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Random House, Inc. New York.

- Searle, J. (1984). Minds, Brains, and Programs. Harvard University Press.

- Searle, J. (1997). The Mystery of Consciousness. The New York Review of Books.

- Simon, H. (1979). Rational decision making in business organizations. American Economic Review. Vol. 69, No. 4.

- Yang, Y. (2022). The Contents, Methods, and Significance of Economic Dynamics: Economic Dynamics and Standard Model (I). Science, Economics, and Society, Vol 40. (Chinese version).

- Yang, Y. (2024). The Contents, Methods, and Significance of Economic Dynamics: Economic Dynamics and Standard Model (I). Preprint. (English version). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. (2025). Consciousness Cone and Artificial Intelligence: A Special Relativity Approach. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Zee, A. (2003). Quantum Field Theory in a Nutshell. Princeton University Press.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).