1. Introduction

Dairy cows are inherently social animals. They actively participate in both affiliative and agonistic social interactions with other cows within the barn. Affiliative behaviors such as grooming and resting in proximity to others serve to reduce stress while strengthening social bonds. On the other hand, agonistic behaviors such as headbutting and displacement tend to result from competition and the establishment of dominance. Social interactions are important because they influence animal welfare, health, and productivity [

1].

Social Network Analysis (SNA) provides a robust framework to explore and quantify these social behaviors. It offers a computational analysis of interaction maps to examine individual social preferences and group level cohesions. SNA is becoming more common in the study of dairy cows alongside other research elements, such as computer vision, deep learning, and artificial intelligence (AI). These advancements help with the unobtrusive monitoring of dairy cows, enabling the collection of interaction data and analysis of social behaviors to be conducted on a larger scale [

2].

Therefore, understanding cow sociality through SNA methods can support the development of practical welfare-oriented strategies for barn management, in turn, improving cow health, longevity, and productivity. However, Hosseininoorbin et al. [

3] points out that existing AI-driven SNA frameworks prioritize proximity metrics over behavioral intentionality (e.g., distinguishing grooming from forced displacement), limiting their capacity to model true social agency in dairy herds. Considering such constraints and the growing importance of AI in monitoring livestock, a comprehensive synthesis of current approaches is necessary. This review focuses on three main areas: (1) understanding affiliative, agonistic, and dominance behaviors of dairy cows and the application of SNA as a metric to capture these behaviors; (2) discussing the impact of computer vision, deep learning, and AI technology on monitoring behavior, predicting actions, and constructing social networks; and (3) outlining gaps in the research pertaining to precision livestock farming, specifically those relating to monitoring dairy cows.

1.1. Literature Search and Selection Methodology

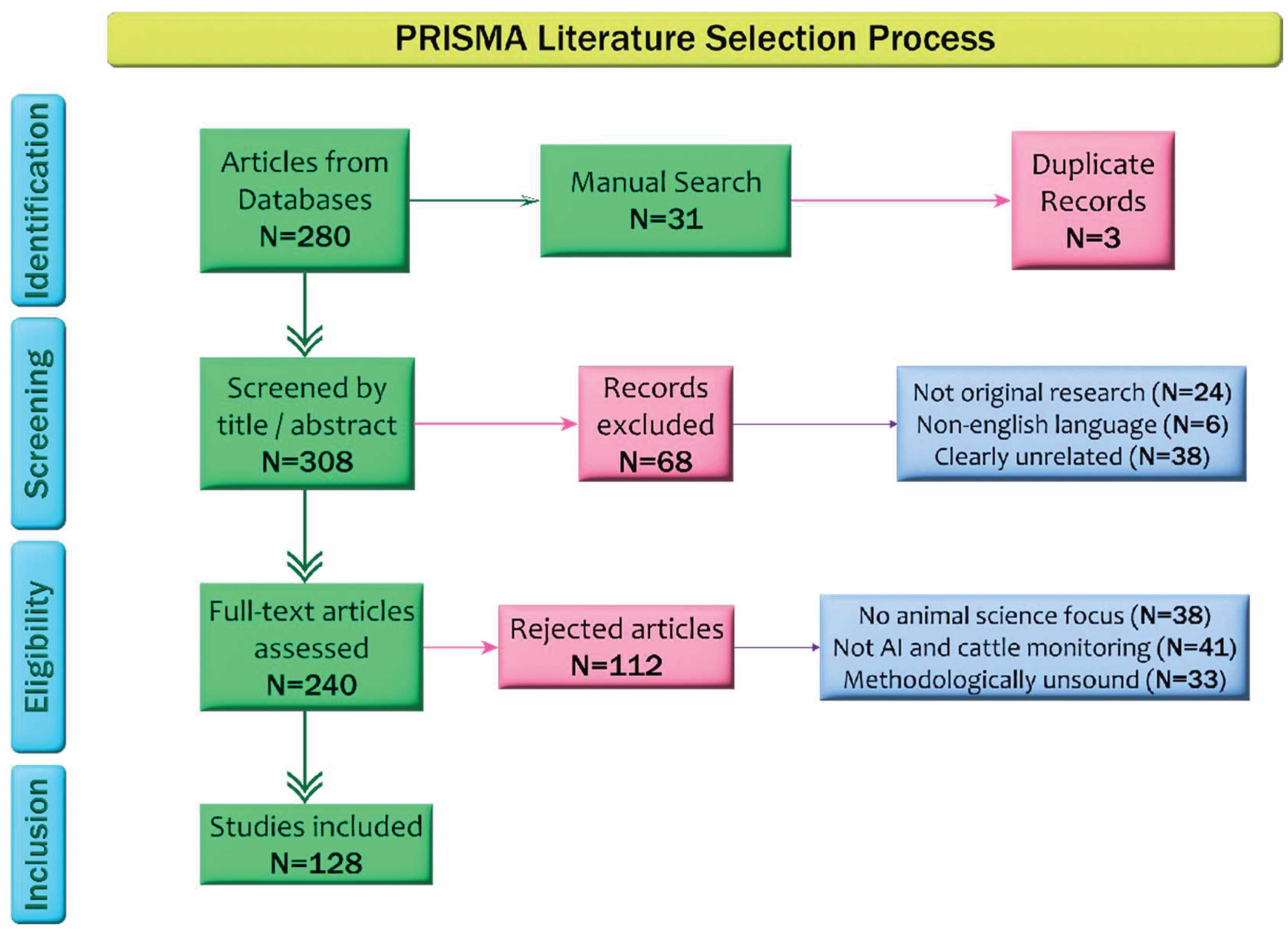

A systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines [

4] to maintain methodological transparency, reproducibility, and academic rigor. The review sought to consolidate literature on SNA of dairy cows, paying particular attention to studies that integrate computer vision, deep learning, and AI technologies for monitoring and behavioral analysis of cattle.

The primary search was conducted using Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar and ScienceDirect. To enhance discovery and mitigate publication bias, Litmaps was used for citation chaining and cluster mapping to find papers that are semantically related but might not be accessible in traditional search listings. The keywords strategy consisted of combining and permuting terms including “Social Network Analysis”, “Social Network Analysis of Dairy Cows”, “Precision Livestock Farming”, “Cow Identification”, “Cow Tracking”, “Cattle Keypoint Detection”, “Cow 3D Tracking”, “Proximity Interactions”, “Herd Health Monitoring”, and “Cow Pose Estimation”.

The review focused on literature published from 2019 to 2025 to capture recent advancements like transformer-based architectures, multi-modal sensing technologies, and edge inference platforms with real-time capabilities. However, there was a selective add of literature outside the temporal scope prior to 2019 under well-defined inclusion criteria. Such older literature was retained only when it was shown to offer foundational concepts in machine learning applicable to current animal monitoring technologies or provided novel AI-based cattle monitoring technologies that have been substantively validated or extensively referenced in contemporary research. This mitigates temporal bias while still meeting the needs of the review’s theoretical underpinnings.

Eligible studies were those conducted in English, published by a peer-reviewed journal, and focused on monitoring dairy cattle behavior, social interactions, or welfare. The selected studies employed SNA methods to quantify behaviors, including affiliative grooming, agonistic displacements, dominance, and proximity-based interactions and implementation of computer vision or deep learning algorithms or sensor technologies such as Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), Ultra-wideband (UWB), and Automated Milking Systems (AMS) for monitoring cattle. This review analyzed empirical simulations as well as conceptual frameworks relevant to SNA and AI in livestock systems. The inclusion criteria extended to theoretical sources only when they served a foundational explanatory role like Alpaydin’s Introduction to Machine Learning [

5] that served to explain supervised learning paradigms that are essential for several of the models present in the included research.

Studies were excluded if they were not original research, had no relation to dairy cattle, lacked any application of AI or social network techniques, or failed to include animal science and animal-level behavioral modeling. Additional exclusions were made for papers that lacked methodological clarity or could not be reproduced due to insufficient reporting.

The screening followed a three stage process. First, a total of 311 records were obtained: 280 from databases, and 31 from manual and Litmaps-aided citation discovery. After removing three duplicates, 308 records remained for title and abstract screening. In this phase, 68 papers were excluded for lack of relevance, originality, or not being in English. Two hundred forty papers proceeded to full-text review. During this stage, 112 additional papers were exclusion candidates: 41 were on topics unrelated to AI and cattle monitoring, 38 did not focus on animal science; 33 were deemed methodologically unsound and unfit.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the systematic literature search process following PRISMA guidelines. It outlines the methodical approach taken to select relevant studies on dairy cow behavior, social network analysis, and AI-based monitoring technologies.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the systematic literature search process following PRISMA guidelines. It outlines the methodical approach taken to select relevant studies on dairy cow behavior, social network analysis, and AI-based monitoring technologies.

In total, 128 papers were deemed eligible for inclusion. These papers cover a range of subtopics such as behavioral analysis with SNA, identity tracking through object detection models, proximity sensing, and inference of social structure through network metrics. A number of included studies utilized modern architectures such as YOLO (You Only Look Once), EfficientDet, CNN-LSTM (Convolutional Neural Networks – Long Short Term Memory) hybrids, and attention modules like CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module). The quality assessment was performed based on reproducibility and clarity benchmarks that involved data transparency, availability of source code or algorithms, and strength of model validation methods (eg: cross-validation, multi-farm validation).

Several strategies were used to minimize bias. No studies were excluded based on result positivity or statistical outcomes, which along with multiple sensing modalities and geographic locations included, ensured the review was not narrowly tailored to a specific context. Also, citation tracing with Litmaps allowed inclusion of strong studies that are often ignored —to construct a more comprehensive corpus.

This approach provided a well-defined yet comprehensive collection of literature regarding the application of SNA in dairy cow monitoring systems in relation to AI and practical farming applications.

1.2. Review Scope and Structure

This review aims to summarize the recent findings and advancements that have been made in the field of SNA of Dairy cows with particular emphasis on Computer Vision, Deep Learning, Neural Networks and A. It starts by explaining social behaviors in dairy cows and the development of sociality. It then explains the application of SNA for quantification of social interactions, followed by detailing the technological improvements in dairy cattle monitoring systems. Further sections provide a detailed account of deep learning, object recognition, identity tracking, and interaction inference. Finally, the review examines the ongoing issues in classifying behaviors and synthesizes the identified research gaps alongside future scopes of work.

2. Social Network Analysis

Understanding social interactions in dairy cattle starts from looking at the basic social behaviors that define their social lives. This section discusses some SNA results retrieved from analyzing affiliative and agonistic behaviors of dairy cows, the development of social roles, as well as network-level patterns such as dominance structures, stability, and the impacts of regrouping. It also explains how A, and especially vision-based systems, improves the monitoring and modeling of these behaviors in real time and connects social behaviors to welfare and productivity outcomes.

2.1. Grooming Relations and Affiliative Behavior

Grooming among cows is a type of interaction which is systematic, structured and non-random. Foris et al. [

6] reported that grooming behaviors are often asymmetrical. However, Freslon et al. [

7] observed that reciprocal grooming was common—suggesting a tendency for cows to groom those who had previously groomed them. It is also interesting to note that cows who heavily invested in grooming others were less likely to be groomed themselves; suggesting high social spenders may bear some costs.

Rocha et al. [

8] drew attention to the existence of stable preferential partnerships as a form of social organization at the herd level, where cows maintained contact with specific partners, sometimes referred to as ’affinity pairs’ in the context of their social groups. In addition, Machado et al. [

1] observed social licking behavior in 95% of the cows, noting that it reached its greatest intensity around 10:00 a.m and was often accompanied by feeding. In addition, proximity and licking events were positively correlated, albeit weakly, which indicates social proximity and contributes to the bonds supporting social cohesion among the group [

9]. Familiarity is important since familiar cows had a higher likelihood of grooming each other than unfamiliar ones [

10], and social grouping influenced their access to resources and general behavioral patterns [

11].

2.2. Development of Sociability During Weaning

The foundation for the development of adult cattle social behavior is laid very early in their lives, during their pre-weaning and weaning phases as calves. Diosdado et al. [

12] observed that calves formed stronger bonds with familiar peers, although these associations proved to be rather unstable over time. Burke et al. [

13] found that weaning increased social centralization, with some calves possessing relatively strong social roles that spanned several weeks.

Heifers raised socially exhibited more expansive and cohesive networks compared to those raised in isolation, as reported by Clein et al. [

14]. This illustrates that early social exposure enables strong social integration post-weaning. Also, Marina et al. [

15] showed that cows that were born close in time to each other, or were otherwise related, were more likely to form long lasting social ties.

2.3. Impact of Grooming and Affiliative Bonds

Affiliative interactions do not serve only for social comfort. They entail a number of more complex effects in cows’ behavior. As an example, Gutmann et al. [

16] remarked that cows placed into unfamiliar groups postpartum demonstrated lower lying times and dyadic synchrony—both of which are considered markers of social stress—which underlines the buffering impact of companionship. Likewise, de Sousa et al. [

9] demonstrated that subordinate individuals were enabled to more efficiently access food due to Egist-Helper relationships with dominants.

2.4. Dominance and Hierarchy Structures

Most researchers agree that dairy cows form a dominance hierarchy which is not strictly linear. Krahn et al. [

17] stated environmental conditions, hunger, reproductive status, and personality traits tend to influence resource access more than the rank of domination. Burke et al. [

13] also showed that heavier and male calves were more central in the networks which indicates their greater social value. Some researchers employ various dominance scoring techniques, but they all seem to face difficulty in establishing consistent rankings due to clear differences in measurement methods and observational contexts [

17]. Current SNA metrics, while descriptively rich, lack validated links to productivity biomarkers—a critical gap for translational precision livestock farming. This illustrates the need for future studies to combine structural network metrics such as centrality or dominance metrics with measurable indicators of welfare, including but not limited to, milk production, lameness, or lying time.

2.5. Influence of Parity, Age, and Health

Social behaviors are slightly influenced by age and reproductive condition. Older cows seem to participate in grooming more often, which may reflect their social rank [

7]. Pregnant cows tended to receive more licking while older individuals both gave and received more licking as noted by Machado et al. [

1], though these behaviors were not significantly associated with the hierarchy of dominance.

Social avoidance behavior due to lameness, parity and lactation stage, as reported by Chopra et al. [

18], did not appear to be consistent, although there was some emerging preference on the socially active individual level. Additionally, Marumo et al. [

19] reported that multiparous cows outperformed primiparous cows in relative social association strength and milk production, though their maximum association strength did not directly correlate with milk yield. Health as a factor impacting sociability was supported by Burke et al. [

20] and Diosdado et al. [

12], who independently reported that sick or socially challenged calves, despite being more socially active, exhibited lower centrality and association strength.

2.6. Individual and Spatial Sociability Patterns

Social behavior differs on an individual basis. Foris et al. [

6] and Rocha et al. [

8] documented individual differences in social behavior that were consistent over time across many individuals. Chopra et al. [

18] also noted that some cows demonstrated stable behavioral patterns over time, indicating underlying sociability traits. Marina et al. [

2] observed that individual positions in a social network, such as centrallity, were more stable over time than group level dynamics. Spatial placement is essential as well. Rocha et al. [

8] and Chopra et al. [

18] showed that cows exhibit greater individual differences in resting areas over feeding areas. Marina et al. [

15] substantiated that there are location-dependent differences in the interaction patterns with other animals in the barn.

2.7. Network Stability

Social networks among cows are not random. Freslon et al. [

7] noted that the social networks of cows are structured and orderly. Pacheco et al. [

21] reported herds of cattle would form affinity relationships and maintain them over an extended period. Burke et al. [

13], as well as Marina et al. [

15], documented some repeatability in the aforementioned roles, together with degree and centrality, which suggests some level of stability within the network over shorter periods.

2.8. Consequences of Regrouping

Regrouping disrupts already existing social systems. Rocha et al. [

8] noted that the addition of new cows to existing networks weakened them for at least two weeks. Even the resident-resident ties began to diminish weakening network strength. However, the underlying cause of this destabilization remains unclear. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if post-regrouping network fragmentation reflects transient stress or permanent social memory impairment in dairy cows. Pacheco et al. [

21] demonstrated that the separation of affinity pairs led to increased variability in milk yield by three-fold, underscoring the extent of impacts in productivity. Smith et al. [

22] noted that unfamiliar cows possessed lower centrality, often remaining on the periphery of social structures even days after introduction, while familiar cows offered little interaction to newcomers, indicating passive rejection.

2.9. Agonistic vs. Affiliative Interactions

Agonistic and affiliative networks are distinct and as such uncorrelated. These relationships remain relatively stable over time, according to Foris et al. [

6]. In contrast, the cows receiving the most preferred mates were shown to display significantly higher rates of both affiliate (3× more licking) and agonistic (1.3× more displacements) behaviors, suggesting emotionally charged bonds, as noted by Machado et al. [

1]. Foris et al. [

10] noted that while grooming networks were sparse and were stable compared to the more volatile displacement networks. Familiarity appeared to have an impact on affiliative behaviors, but agonistic actions were largely unaffected which suggests that competition for resources might be more uniform as opposed to preference for affinity pairs.

The prediction of cow social roles became possible with the rise of computational modeling. Marina et al. [

2] showed STERGM’s (Separable Temporal Exponential Random Graph Models) ability to estimate centrality using network features with moderate predictive power (r = 0.22–0.49) and improved accuracy with triangle-based features. This underscores the growing possibility of short-term behavioral forecasting using graph-based models. As discussed above, SNA illuminates rather sophisticated and subtle social interactions of dairy cows that can be studied and interpreted through quantification. From early-life bonding, affiliative grooming, and the disruptive influence of regrouping, spatial positioning and hierarchy, bovine behavior is intricate yet remarkably individualistic. Individual traits such as centrality, association strength, and closeness as social traits remain stable across varying times and contexts, providing reliable behavioral identifiers, or “fingerprints,” for each animal [

6,

8].

2.10. Bridging AI and Animal Ethology

We have come a long way from when AI and cows were rarely spoken together in the same sentence, until technology brought them together in the dairy industry. Now, with the use of AI such as computer vision and deep learning models, monitoring dairy farms has become more efficient and accurate. Instead of needing field staff to constantly walk about the farm with clipboards collecting data, cows can now be monitored through unobtrusive cameras that have been placed around the barn, feeding time, licking time and even idling can all be tracked giving remarkable insights into the health of the herd as a whole [

23].

A contemporary computerized dashboard enables instant access to numerous performance indicators such as grazing time, feeding, and standing duration, which are very useful KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) to determine comfort and productivity. Withstanding time in alleys being unproductive, lying time directly represents the feed to milk conversion ratio which significantly impacts profitability as well as welfare [

16]. With this technology, assessment of welfare has shifted from periodic manual checks, which were very labor intensive, to something done on a daily basis in real time, enabling automated evaluations that would have been impractical before [

24].

In addition, the cow comfort index, which was only occasionally applied in academic work, has turned into a measurable standard on commercial farms, where it is tracked daily by AI sensors and cameras [

25]. What the Automated milking systems and cameras provide for cattle is often misunderstood as an unwanted intrusion of privacy and the natural setting of the animals. Along with reducing the manual labor needed on the farm, these modern systems give supervisors and operators the ability to intervene less often, but more strategically. Also, modernized barns enable cows to behave freely and naturally, and they have the flexibility to decide when they want to rest, eat, or be milked which bolsters welfare and overall productivity. However, this technological shift also raises important ethical considerations. The pervasive deployment of vision systems in barns necessitates explicit discussion of farmer-cow data consent frameworks and algorithmic transparency to avoid “digital paternalism” in livestock management.

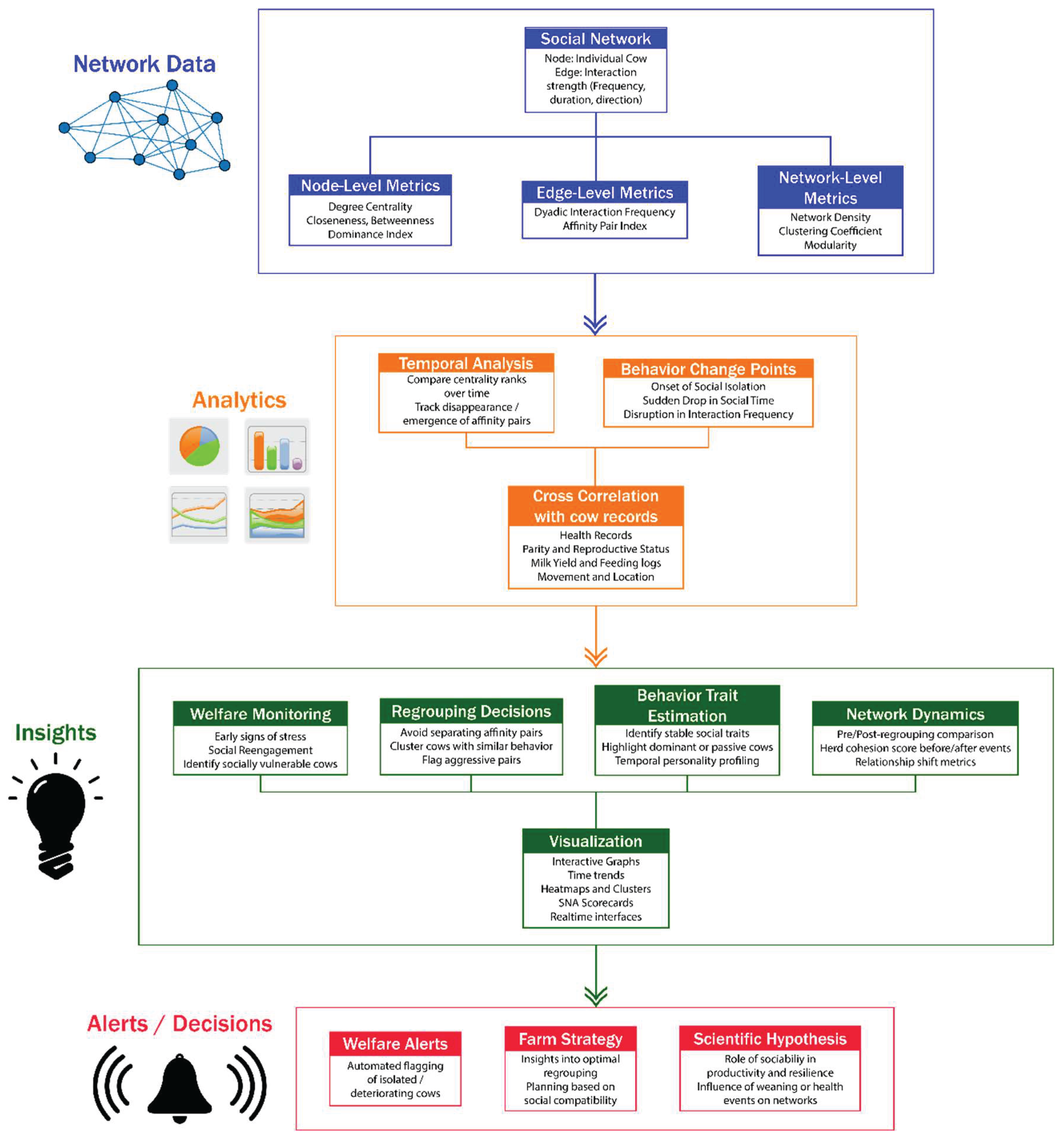

These visual information streams are mapped by SNA into interpretable social metrics. Indicators like degree centrality, betweenness, or association strength, as listed in the table, quantify the level of connectivity and interaction each cow has with the other members of the group, and how central it is to the cohesion of the herd. These are not ungrounded academic abstractions—they constitute practical measures of stress, social isolation, or declining health.

Table 1.

Sociability Metrics for Evaluating Dairy Cow Social Interactions.

Table 1.

Sociability Metrics for Evaluating Dairy Cow Social Interactions.

| Metric |

Definition |

Behavioral Interpretation |

Calculation Method |

Data Requirements |

Limitations |

References |

| Degree Centrality |

Number of direct connections |

Measures social popularity; high = frequent interactions |

∑ edges per node |

Interaction logs |

Ignores interaction quality |

[2,20,26] |

| Betweenness |

Role as a social bridge |

Identifies gatekeepers controlling resource access |

Paths passing through node |

Network topology |

Computationally intensive |

[2] |

| Closeness |

Average path length to others |

Reflects social integration; low = isolated individuals |

1 / ∑ shortest paths |

Full network data |

Sensitive to network size |

[12] |

| Eigenvector Centrality |

Influence within network |

Highlights cows central to cohesive subgroups |

Adjacency matrix eigenvectors |

Weighted interactions |

Favors high-degree nodes |

[12,14,15] |

| Association Strength |

Frequency of pairwise interactions |

Indicates affinity bonds or avoidance |

Interaction count / time |

Continuous tracking |

Context-dependent |

[12] |

| Reciprocity |

Mutual grooming / displacement |

Measures social balance; high = reciprocal relationships |

Mutual interactions / total |

Directed interactions |

Fails in dominance hierarchies |

[7,14] |

| Network Density |

Proportion of realized connections |

Group cohesion; high = tightly knit social structure |

Actual edges / possible edges |

Complete interaction data |

Biased by group size |

[10] |

| Dominance Index |

Asymmetry in agonistic interactions |

Hierarchy stability; high = clear dominance order |

Wins / (wins + losses) |

Agonistic event logs |

Misses subtle competition |

[17] |

| Clustering Coefficient |

Tendency to form triangles |

Subgroup formation; high = cliquish behavior |

Triples of connected nodes |

Local network structure |

Less meaningful in small networks |

[8,18] |

| Reachability |

Access to others via indirect paths |

Social integration; low = marginalized cows |

Binary reachability matrix |

Full network |

Binary simplification |

[22] |

| Synchrony Index |

Temporal alignment of behaviors |

Social bonding; high = coordinated resting/feeding |

Cross-correlation of timelines |

High-resolution tracking |

Requires timestamped data |

[20] |

| Social Differentiation |

Variation in interaction rates |

Individual sociability traits; high = diverse social roles |

Standard deviation of interactions |

Longitudinal data |

Sensitive to observation duration |

[18] |

| Edge Persistence |

Stability of pairwise ties |

Long-term social preferences |

Interactions over time windows |

Multi-session tracking |

Requires repeated measures |

[15] |

| Affinity Pair Score |

Strength of preferential partnerships |

“Friendship” bonds; high = stable grooming/resting pairs |

Dyadic interaction frequency |

Individual-level tracking |

Environment-dependent |

[21] |

| Isolation Index |

Proportion of time alone |

Welfare risk; high = social withdrawal |

Solo time / total time |

Location + interaction data |

Confounded by barn layout |

[18] |

As technology advances, so does intelligence in interpretation of camera footage. Modern computer vision systems can now recognize lying, feeding, and even affiliative behaviors such as grooming—all of which integrate seamlessly into SNA frameworks that aid in daily management. To be precise, SNA has transformed from merely a research tool into a real-time welfare system monitoring the health and well-being of animals. It bridges biology to technology to help answer the fundamental question in dairy science: What makes a cow happy? Because, as experts put it, a happier cow is a healthier cow.

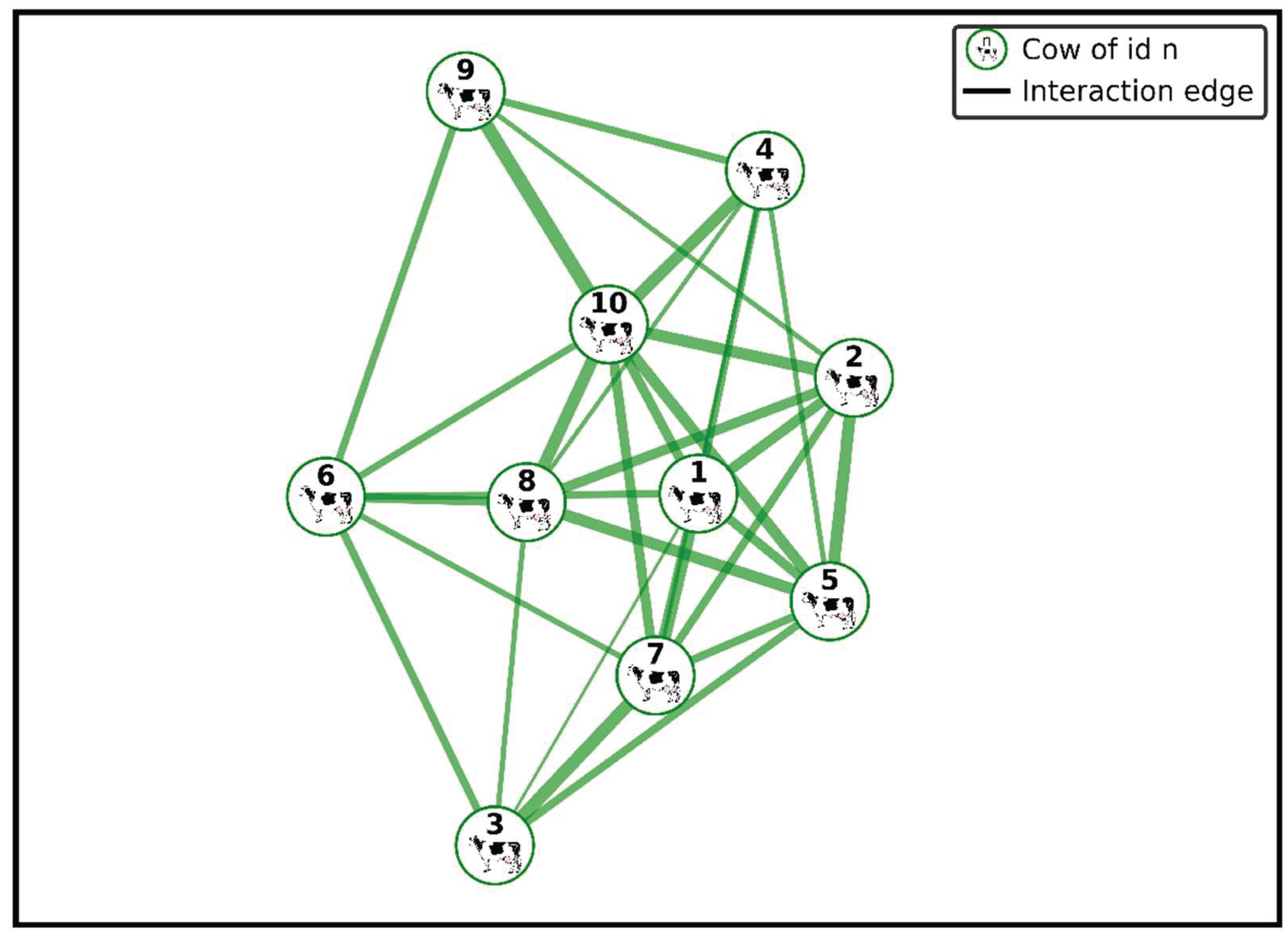

To transform social interactions into actionable insights, one must first build a functional social network for the observed cattle group. Within this framework, social networks constitute graph-structured representations where each individual cow is a node, while social weight interactions between them are denoted as edges. Although directed edges theoretically offer richer relational interplay, most studies today employ undirected networks due to the practical difficulties of determining interaction direction in uncontrolled real-world dairy settings.

Figure 2.

Example of an undirected social network graph depicting interactions among dairy cows. Each node represents an individual cow, and thicker lines indicate stronger or more frequent social interactions, providing insights into herd social dynamics.

Figure 2.

Example of an undirected social network graph depicting interactions among dairy cows. Each node represents an individual cow, and thicker lines indicate stronger or more frequent social interactions, providing insights into herd social dynamics.

3. Cattle Monitoring Systems: Enabling Precision Livestock Farming

The ability to evaluate livestock welfare, behavior, and productivity at scale and automatically is provided by automated Cattle monitoring systems which form a part of Precision Livestock Farming (PLF). Wearable and vision-based systems capable of tracking a multitude of behaviors including feeding, lying, locomotion, and social interactions have become more widespread because of technological advancements [

27]. These systems mark a drastic movement from observation based on manual methods to analytics based on rich data collected in real-time.

3.1. From Manual Observation to Semi-Automation

In the past, behavioral data collection in cattle studies involved a lot of fieldwork, requiring lots of time and personnel trained to observe the subjects. In Machado et al. [

1], a number of trained observers employed a scan sampling method to note licking and agonistic behaviors, checking on them every six minutes and noting their spatial proximity (within four meters). This approach was replicated by Freslon et al. [

7], where human observers performed daily evaluations over a period of six weeks.

Nevertheless, such protocols that are intensive in nature posed issues with accuracy and scaling. This is the reason semi-automated systems came into existence. In Jo et al. [

28], video analysis softwares allowed trained observers to annotate social interactions in terms of the instigator, receiver, and the location which improved data collection in terms of reliability and efficiency.

3.2. Rise of Smart Farms and Automated Data Acquisition

The cattle monitoring industry has changed very quickly because of the need for real-time, automatic, and situationally aware systems. Xu et al. [

29] stressed the possibility of animal detection, identification, and behavior monitoring under ever-changing environments. In this regard, camera traps, drones, and RGB (Red Green Blue)/thermal imaging along with RFID and GPS (Global Positioning System) have made it possible to acquire behavior-rich datasets from across farms and other settings.

Sort gates demonstrate the level of automation that has been achieved in barn logistics. These gates identified cows through RFID and assisted in their movement for milking, feeding, or health checks. In Pacheco et al. [

21], sort gate passage logs were used for affinity pair analysis in order to estimate movement-based affinity pair analysis which revealed hidden social relationships captured through logistical data.

3.3. Sensor-Based Monitoring and Network Inference

Technologies that utilize sensors such as GPS, ultra-wideband RTLS (Real Time Locating System), accelerometers, and pedometers have become critical for continuous high resolution positional tracking. Using radio collar tags for triangulation enabled Rocha et al. [

8] to perform SNA over a herd of one hundred fifty-eight individuals. Spatial coordinates were estimated by Chopra et al. [

18] using weighted neck collars equipped with accelerometers. Marina et al. [

2,

15] also utilized ultra-wideband RTLS tags that can monitor cow positions at 1 Hz.

Proximity-based metrics are widely accepted as social interactions, especially within the realm of sensor-based SNA [

21]. Although interaction types cannot be defined due to lack of proximity, cows being close to one another indicates that there is likely an affinity bond forming [

1]. Also note that agonistic behaviors of affinity pairs are likely due to locational resource competition due to resource scarcity, which is why proximity is often regarded as an important social metric. Wearable sensors come with numerous advantages; however, data drift, calibration, external noise slow the sensor operations down, affecting its long-term reliability in outdoor conditions. Additionally, while RTLS tags excel in low-light or crowded barn environments, their inability to distinguish affiliative behaviors such as licking from agonistic ones like headbutting renders them inferior to pose-aware vision systems in behaviorally complex contexts. This behavioral ambiguity has driven the development of vision-based systems that offer richer contextual interpretation of social interactions.

3.4. Advancing Non-Contact and Vision-Based Monitoring

Recent innovations have led to the development of non-invasive methods camera-based methods for cattle monitoring. These systems allow for greater insight in behavioral studies without physical contact. Shorten et al. [

30] developed a hybrid system integrating computer vision with a weigh scale to estimate milk production and assess udder attributes. Their model achieved 94% accuracy using 3D imaging for estimation of teat configuration and R²=0.92 for yield estimation, showcasing efficiency and scalability in performance monitoring. Similarly, Fuentes et al. [

31] developed the first contactless physiological system based on vital signs estimation using RGB and thermal imaging for heart rate and respiration counting. Their system correctly estimated milk yield and fat% and protein%, R=0.96, with ANNs (Artificial Neural Network) offering a persuasive option to invasive methods especially in uncontrolled real world farm settings.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of typical equipment setups in dairy barns contrasting vision-based monitoring systems (using cameras) and sensor-based systems (using wearable sensors). Highlights the differences in complexity, invasiveness, and setup requirements.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of typical equipment setups in dairy barns contrasting vision-based monitoring systems (using cameras) and sensor-based systems (using wearable sensors). Highlights the differences in complexity, invasiveness, and setup requirements.

3.5. Computer Vision and Deep Learning for Behavior Detection

With recent advances in deep learning, models like YOLOv5, YOLOv7 and Faster R-CNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Network) are now available for real-time cattle detection and tracking [

29]. These systems outperform traditional detection tools in identification of interaction behaviors, behavioral deviations, and spatial distribution. Real-world applications of vision systems are hindered by problems like occlusion, lighting conditions, and even the varying breeds of animals. To add onto this, the absence of labeled datasets is troublesome for supervised learning approaches [

27]. For behavioral inference, pose estimation, mounting, and grooming detection have been implemented using 3D CNNs and LSTMs [

32]. However, many of these systems are focused on precise data collection which makes them prone to errors in uncontrolled and unfamiliar barn conditions.

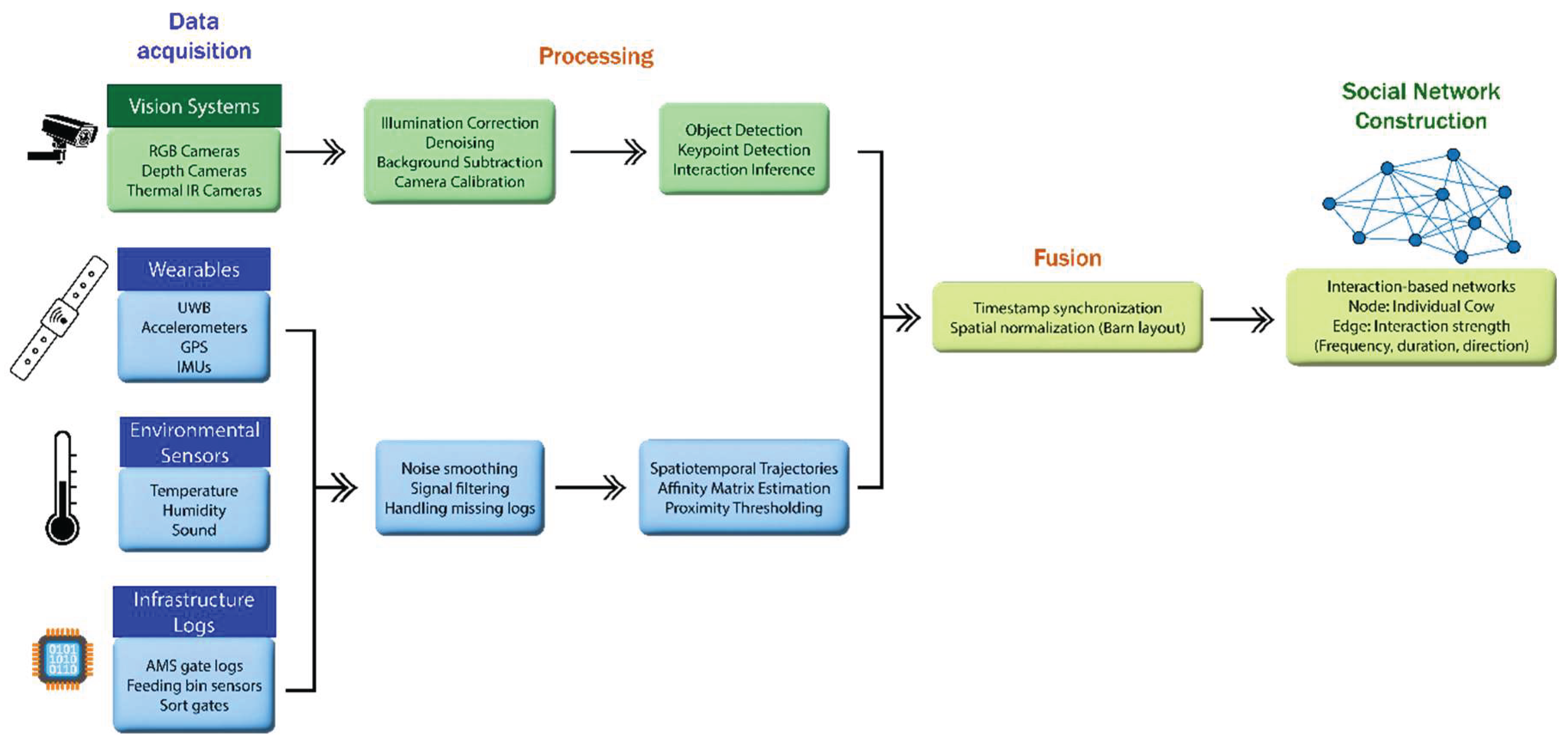

3.6. Sensor Fusion and Systemic Challenges

The integration of vision, audio, and even wearable sensors into a single framework enhances behavioral inference — these systems are known as multi-modality fusion systems [

33]. More sensors which enable recording of cattle behavior must be integrated into wearable devices. Even though the employment of tracking algorithms such as DeepSORT in combination with Kalman filters has advanced tracking robustness in high-density cattle areas, merging multi-sensors is still in its early development stages, and field ready deployments are limited [

34]. Additionally, the processing of some data from sensors (such as Interpolation, smoothing and filtering) is much easier than computer vision which requires a lot of processing to be done (like image preprocessing, object detection, identification and tracking). This sets the computational goal of having efficient and scalable pipelines capable of real-time operation within large farms on-site.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the workflow used to construct and interpret dairy cow social networks from collected data. It shows the step-by-step transformation from raw sensor and visual data into actionable insights for herd management and animal welfare.

Figure 4.

Illustration of the workflow used to construct and interpret dairy cow social networks from collected data. It shows the step-by-step transformation from raw sensor and visual data into actionable insights for herd management and animal welfare.

3.7. Data Annotation, Quality, and Reproducibility

The dataset’s annotation’s availability and quality pose a significant bottleneck in model development. Very little research data is available for benchmarking due to the possibility of human errors in manual annotation [

29]. To address this annotation inconsistency, Ramesh et al. [

35] designed and introduced the SURABHI (Self-Training Using Rectified Annotations-Based Hard Instances) framework, which uses self-training and label rectification to correct annotation inconsistencies using spatial logic combined with confidence thresholds. Their model demonstrated an 8.5% increase in keypoint detection accuracy which proves that temporal self-correction and attention-based filtering can enhance label robustness in complex frames. AI and sensors are now being used to fully automate monitoring of cattle, gradually shifting from outdated manual and semi-automated systems. Although vision-based systems and sensor-based systems each have their own unique advantages, their integration along with better data infrastructure and better annotation holds significant promise for constructing sophisticated, intelligent, and welfare-oriented farm management systems.

Now that the foundational network behaviors and sociability patterns are mapped and established, it is necessary to explore the computational backbone driving these systems. The next section investigates self-organized neural networks which observe, interpret, predict, and quantify cow behaviors, positions, and interactions at a fundamental level vital for the formation of social networks.

4. Deep Learning Algorithms for Computer Vision Tasks

Transforming from manual observation of cattle behaviors to employing computer vision represents a remarkable advancement in monitoring animal welfare. Deep learning (DL) has shown significant promise in cattle detection, posture recognition, and social interaction analysis, particularly using convolutional and recurrent neural architectures. However, implementing deep learning poses significant challenges due to barn environments which are obstructed with complex lighting and unstructured movement combined with confined spaces, causing occlusions and limiting the scope of scalable solutions.

4.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

For image-based cattle data, CNNs are the most commonly utilized deep learning models. CNNs process data with grid-like structure, such as images. They use convolutional layers, which apply filters to input data to detect patterns like edges and textures. Tasks that have spatial detection patterns, such as detection, posture classification, and ID recognition, hinge on CNNs.

Qiao et al. [

36] used an Inception-V3 CNN model on cows’ rear-view video frames, classifying them on a per-cow basis. The backbone model was pretrained on ImageNet. The CNN-only model captured dynamic behavior features without temporal context, leading it to attain a low accuracy of 57%. Considering alongside the findings by Oliveira et al. [

33], it’s evident that most baseline CNN pipelines are unusable under barn conditions, where occlusion, dirt, and lighting variation interfere with visual input. Li et al. al. [

32] noted the effectiveness of CNNs in detecting static postures (lying down or sitting, standing). However, they fall short in recognition of transitions or multiple overlapping behaviors. This shows that CNNs are effective in spatial computation, but are naive for temporal problems.

To address this issue, Qiao et al. [

37,

38] recommend augmenting CNN features with temporal models and alternative SVM (Support Vector Machine) based classifiers to improve performance. Notably, [

37] utilized 2048-dimensional feature vectors extracted from the pooling layers of the CNN, as feature representation which consists of high-dimensional, information rich embeddings. While this improves feature representation, it increases the computational cost and may constrain real-time applications. Chen et al. [

39] modified the Mask R-CNN to lower the computational overhead and achieve precise back segmentation even under occlusion. Mask R-CNN architectures ahve also been adoped for effective pose-variant segmentation. At the same time, [

40,

41] observed the higher detection accuracy achieved by the two-stage CNNs like Faster R-CNN, however they pose difficulties for use in real-time applications due to their trade-offs in speed and scalability.

The extensive use of CNNs in livestock applications is corroborated by [

42,

43], and [

44], who reported high accuracies in animal detection and ID classification with CNN-based systems, utilizing YOLOv8 and VGG16 (Visual Geometry Group). Still, pure CNN systems tend to focus on visually distinct features and struggle with tracking social behaviors as they are poor in identifying subtle behavioral cues, and temporal continuity as mentioned earlier.

4.2. Spatio-Temporal Modeling and Attention Mechanisms

Perplexingly, CNNs processes each frame independently, neglecting the temporal behavior dynamics. This deficiency is addressed by LSTM and BiLSTM (Bi-directional Long Short Term Memory) networks which establish dependencies from one frame to the next. They extend beyond the static spatial feature extraction by learning how spatial patterns evolve over time. As a great example, Qiao et al. [

36] improved identification accuracy from 57% to 91% by using 20-frame sequences, attributed to incorporating LSTM layers to process a series of CNN features, strongly endorsing that temporal modeling is critical. Similarly, Gao et al. [

45] applied a CNN-BiLSTM architecture in real-world barn settings, achieving greater than 93% accuracy despite heavy occlusions. Their high video frame rate processing led to enhanced motion detail but poses a worrying issue for constrained edge devices regarding bandwidth due to limited scalability.

BiLSTM networks, which analyze sequences in both temporal directions, were used by Qiao et al. [

37], who attained 91% accuracy on 30-frame sequences. Their model outperformed both CNN-only and unidirectional LSTM baselines, suggesting motion-sensitive identity cues (e.g., gait, coat pattern flow) can only be captured via bidirectional sequence modeling. Similar approaches by [

46,

43], and [

38] showed that BiLSTM improves behavior classification in cluttered environments, especially when fused with spatial CNN features. To address the issue of noisy frames and partial occlusion, attention mechanisms were introduced. Qiao et al. [

46] embedded an attention layer after BiLSTM, allowing the model to focus on clear, identity-rich frames, achieving up to 96.67% accuracy. Notably, even short clips (1–2 seconds) were sufficient, underscoring attention’s efficiency in low-data settings.

Fuentes et al. [

47] extended the sequence learning paradigm by using ConvLSTM (Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory), which retains spatial structures during temporal modeling. Their system could detect 15 hierarchical behaviors across multiple farms, demonstrating high scalability and robustness in uncontrolled settings. Collectively, these studies suggest that spatio-temporal models with attention are state-of-the-art for livestock behavior detection—but at the cost of higher computational requirements, increased latency, and reduced suitability for real-time deployment unless optimized.

Qiao et al. [

37] applied BiLSTM networks, which analyze sequences in both forward and backward directions, achieving 91% accuracy on 30-frame sequences. Their model surpassed both CNN-only and unidirectional LSTM baselines, indicating that identity motion cues (e.g., gait and coat pattern motion) are effectively captured through bidirectional sequence modeling. Approaches from [

46,

43], and [

38] also reported similar findings where BiLSTM exhibited enhanced behavior classification in cluttered environments, especially in integration with spatial CNN features. To address the problems posed by noisy frames and partial occlusion, attention mechanisms were introducted. An attention mechanism embedding after BiLSTM allows the model to focus on clear, unambiguous identity frames, achieving 96.67% accuracy as stated by Qiao et al. [

46]. Notably, short clips, even as brief as one to two seconds, were efficient, showcasing data efficiency that attention mechanisms provide. Fuentes et al. [

47] expanded the sequence learning framework by utilising ConvLSTM, which preserves spatial structures during temporal modeling. This system was capable of detecting 15 hierarchical behaviors from multiple farms, illustrating strong scalability and robustness in uncontrolled environments.

On the whole, these investigations propose that spatio-temporal attentional models are the best for precision livestock farming behavioral analysis concerning livestock detection — though they make the system computationally more expensive, increase latency, and hence, are not well suited for real-time deployment unless optimized.

4.3. Transfer Learning and Pretraining

To enhance training efficiency and reduce data dependency, numerous researchers utilize transfer learning from models which are pretrained using large-scale datasets such as ImageNet. Qiao et al. [

36] and Qiao et al. [

37] reported significant improvement on the performance of Inception–V3 after fine-tuning it on rear-view cow images. Nevertheless, these pretrained models tend to underperform because of domain mismatch: urban-trained models cannot identify farm-specific features such as tail movement and muddy texture [

38,

33]. Xu et al. [

29] demonstrated an increase in YOLOv7 performance by augmenting with barn-specific images for retraining, showing how crucial domain adaptation is. However, pretraining also poses challenges—specifically the possibility of overfitting to unnatural augmentations that do not accurately represent real barn variability. As such, although transfer learning can be helpful in accelerating the development of a model, it cannot replace the thorough farm data collection and additional model training needed to fully optimize performance.

4.4. YOLO Frameworks for Livestock Applications

The YOLO-based architectures are often preferred due to their real-time detection capabilities enabling on-farm deployments. Their performance, however, commonly suffers under occlusion, lighting variation, and animal overlap unless specially tailored.

Xu et al. [

29] modified YOLOv5/v7 with custom anchor calibration and augmentation strategies enhancing detection performance in cluttered contexts. Qiao et al. [

46] observed how pretrained YOLO models from urban or clear farm scenes were unable to accurately localize cattle in occluded contexts. YOLOv8-CBAM, which Jo et al. [

28] tested, added a Convolutional Block Attention Module which emphasizes important features and surpassed Mask R-CNN as well as YOLOv5 in performance. This architecture reached mAP@0.5 96.8% (Mean Average Precision) while precision stood at 95.2%, proving superior in heavily cluttered real world scenes as compared to Mask R-CNN and YOLOv5.

Other researches [

48,

49,

50] focused on the new variants of Yolo, such as: YOLOv5x, YOLOv4, YOLOv8, all believing in the accuracy-speed ratio offered. Even YOLOv7 however, required attention-engancements (such as Coordinate Attention and ACmix (Attention Convolution Mix)) to process dense, object-rich datasets like VisDrone [

51].

Although versatile, the YOLO models maintain a competitive edge only with an extensive amount of anchor and attention modular tuning. Moreover, unless combined with a robust tracking system, they heavily struggle with identity switch issue, which need to be addressed for social network tracking. The tracking system unless lightweight would hinder the real-time capability of YOLO. In practice, deployment feasibility also hinges on energy efficiency: YOLOv8-CBAM’s 40W power draw per camera significantly limits its scalability in solar-powered or low-resource barns, especially when compared to EfficientDet’s 12W baseline [

52].

4.5. Capabilities, Challenges, and Future Directions

Neural network models have demonstrated strong effectiveness in the following areas:

Detection of Static Postures with CNNs [

32,

33];

Behavior Recognition with LSTM/BiLSTM and ConvLSTM [

36,

43,

45];

Real Time Detection with YOLO and EfficientDet [

53,

54];

Multimodal fusion of RGB, thermal, and spatial data [

28,

31,

55];

Attention-based frame selection to reduce noise [

46,

48].

End-to-end models such as EfficientDet préprocess streams of video, and true to their name, achieving real-time inference with fewer FLOPs (Floating Point Operation)—paving the way for edge device and mobile GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) deployment [

40,

41,

48]. The new self-training framework, SURABHI [

35], strengthens pose estimation by improving annotations produced by machines, automating an important step in low-annotation data situations. Nonetheless, development of efficient neural networks and deploying them for real-time, real-world use has its own set of challenges.

4.5.1. Key Limitations

Some key bottleneck regarding neural networks include:

Absence of public datasets greatly limit reproducibility [

33,

44,

56];

Farm-specific retraining is needed to improve breed, lighting, and occlusion generalization.[

32,

57];

Real Time Detection with YOLO and EfficientDet [

53,

54];

The cost of computation for attention-augmented or multi-camera systems still limits deployment in real-time [

43,

53,

58];

Applicability for complex spatial behaviors is limited as many models are tested using single-view data [

36,

37,

38].

4.5.2. Recommendations

The immediate focus regarding the neural network’s use in monitoring dairy cattle should emphasize the following,

Standardization and sharing of the dataset for benchmarking [

32,

33,

56];

Semi-supervised learning and label revision (for example, SURABHI [

35]) to minimize manual tagging;

Increased[

43,

53,

58] generalizability with Multimodal integration (thermal, RGB, depth) [

28,

46,

55];

Compound scaling and modular attention for edge-optimized architectures [

48,

51,

53];

Crossover in-breed and cross-layout validation to test and validate robustness [

38,

46].

Table 2.

Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures Used in Dairy Cow Monitoring.

Table 2.

Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures Used in Dairy Cow Monitoring.

| Model |

Application |

Performance Metrics |

Computational Cost (TFLOPs) |

Strength |

Limitations |

References |

| YOLOv8-CBAM |

Detection |

mAP@0.5: 96.8%, 95.2% P |

40 W/camera |

Occlusion robustness |

High energy use |

[28] |

| EfficientDet-D4 |

Detection |

mAP@0.5: 94.1%, 12W |

5.6 |

Edge-device optimized |

Struggles with small objects |

[53] |

| BiLSTM + Attention |

Identification |

96.67% accuracy |

28 |

Temporal context modeling |

Requires video sequence |

[59] |

| Mask R-CNN |

Segmentation/ID |

94% IoU, 98.67% ID |

22 |

Precise instance segmentation |

Slow for real-time |

[40,60] |

| Vision Transformer |

Open-set ID |

99.79% CMC@1 |

45 |

Scale-invariant features |

Needs large datasets |

[61] |

| DeepSORT + YOLOv5 |

Tracking |

MOTA: 82.6%, IDF1: 89.4% |

18 |

Occlusion handling |

ID switches in dense groups |

[42,57] |

| ResNet-50 + ArcFace |

Facial ID |

93.14% CMC@1 |

8.2 |

Lightweight embeddings |

Frontal view required |

[62] |

| ConvLSTM |

Hierarchical behavior |

84.4% F1-score |

33 |

Spatio-temporal modeling |

Computationally heavy |

[63] |

| ByteTrackV2 |

Multi-object tracking |

HOTA: 68.9%, IDF1: 76.2% |

14 |

Balances speed/accuracy |

Struggles with erratic motion |

[34] |

| PointNet++ |

3D ID |

99.36% accuracy |

21 |

Depth-invariant features |

Requires RGB-D sensors |

[64] |

| DenseNet-121 |

Facial ID |

97% accuracy |

6.7 |

Feature reuse efficiency |

Overfits small datasets |

[44] |

| STERGM |

Network prediction |

r = 0.49 (centrality) |

N/A |

Dynamic network modeling |

Requires historical data |

[2,15] |

| SURABHI (Self-train) |

Pose estimation |

+8.5% keypoint accuracy |

9.1 |

Reduces annotation effort |

Initial manual labels needed |

[65] |

| Graph Neural Network |

Multi-object tracking |

89% precision |

19 |

Reduces computational cost |

Detection, tracking tradeoff |

[66] |

4.5.3. Emerging Directions

The capabilities of precision livestock farming have been enhanced with new automated systems for behavioral understanding, automated tracking, and scalable health diagnostics benefitting from the innovations in deep learning. But as Arulprakash et al. [

40] shows, no single architecture is proven yet to satisfy generalizability across multiple domains and problems, speed, robustness, and scalability simultaneously in the context of dairy cow monitoring. Advancements in Deep Learning models will stem from innovation in architecture combined with improved infrastructure, including better datasets, smart annotations, and multimodal sensing. Moreover, in practical scenarios, the system’s backbone determines model performance, and dataset quality dramatically compounds the impact. Deep learning models used for dairy welfare and management will gradually shift from analytical tools to components of real-time autonomous AI decision-maker systems, enabling rapid response to monitoring and analytical challenges.

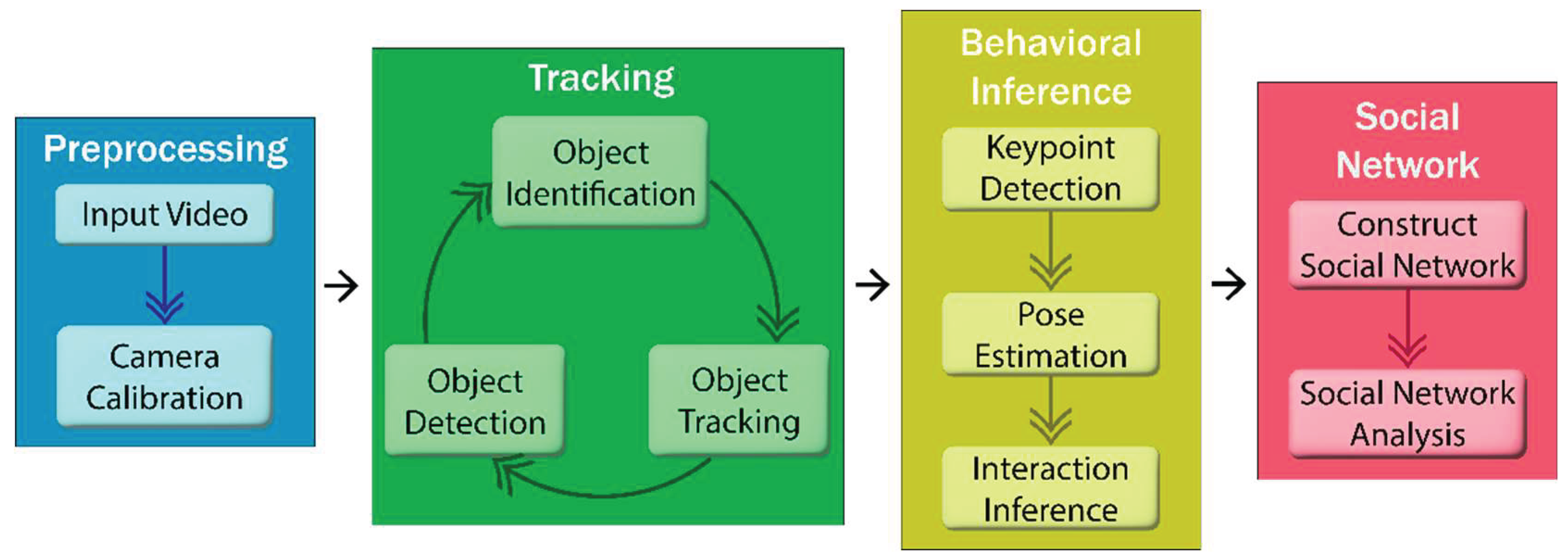

5. Object Detection in Cattle Monitoring

The analysis of cattle social behavior is sequential and hierarchical in nature. It starts with a video capture and ends with an interpretation of interactions among the cattle. The figure below (to be inserted) shows in broad terms the cattle monitoring steps within precision livestock farming.

Figure 5.

Detailed pipeline overview illustrating the end-to-end process of cattle monitoring using computer vision. This pipeline covers object detection, cow identification, tracking, pose estimation, behavior inference, and subsequent analysis for herd management.

Figure 5.

Detailed pipeline overview illustrating the end-to-end process of cattle monitoring using computer vision. This pipeline covers object detection, cow identification, tracking, pose estimation, behavior inference, and subsequent analysis for herd management.

Although the complete pipeline is defined as the best way to tackle the problem, some of the studies might choose to only a smaller subset, such as omitting explicit identification, keypoint detection, or pose estimation based on the data they have, or the goals defined for their problem. Object detection is the first and most foundational in this pipeline. In this regard, it is essential to explore applied computer vision through the lens of object detection for cattle in barn environments facing occlusion, lighting changes, and movement.

5.1. Object Detection: From Static Identification to Context-Aware Sensing

Accurate and robust object detection systems are not only crucial for identifying the presence of cattle but are also fundamental enablers of ID, tracking, pose estimation, and behavior inference. It is desirable for the cattle detection to perform well across a variety of visual distortions including occlusions, low contracst (e.g, black cattle against dark background), and irregular movements. The evolution of object detection architectures from early CNN-based models to more accurate, transformer-enhanced hybrid systems has also seen an increased complexity.

5.1.1. Early CNN-Based Detection and Two-Stage Architectures

Cattle monitoring initially relied on traditional object detection techniques using CNN-based models along with two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN and SSD (Single Shot Detector). These models claimed to achieve reasonable baseline accuracy with simple and controlled scenarios. Li et al. [

32] offered a benchmark of YOLOv3, ResNet, VGG16, and R-CNN in barn settings, capturing strong accuracy but noted significant limitation regarding real-time inference, occlusion generalization, and farm-wide applicability and generalization. Huang et al. [

55] applied an enhanced tail detection model incorporating Inception-v4 and DenseNet block SSDs, reporting outstanding detection metrics (Precision: 96.97%, Recall: 99.47%, IoU: 89.63%). This model bested YOLOv3 and R-CNN’s accuracy and speed while harnessing over 8,000 annotated images. However, tail-based systems are occlusion-sensitive, severely limiting their application for behavior tracking when animals are densely packed or in motion. In the same way, Tassinari et al. [

58] utilized YOLOv4 to detect general presence of cows and classify basic behavioral patterns such as lying, feeding, and walking, providing early indications that computer vision could replace sensor-based systems for continuous cattle monitoring.

Around the same time, Andrew et al. [

67] tested RetinaNet, another two-stage model, for cow detection. It achieved a mAP of 97.7%, with ID accuracies reaching 94%. RetinaNet did outclass YOLOv3 in classification accuracy, but was slower—showing the speed versus accuracy compromise of two-stage detectors.

5.1.2. The Rise of Real-Time Detection: YOLO and Efficiency

Single-stage detectors, particularly variants of YOLO, were adopted to tackle practical considerations around real-time, low-latency inference. Noe et al. [

57] showed that YOLOv5 models provided the best balance of accuracy and speed, with YOLOv7 surpassing detections even more but at a higher cost of computation. Wang et al. [

51] incorporated attention mechanisms such as Coordinate Attention (CA), ACmix, and SPPCSPC (Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Cross Stage Partial Connections) into YOLOv7. These updates increased the model’s mAP by 3–5% while maintaining a real-time frame rate of 30–40 FPS. However, this added computational burden creates difficulties for edge deployment in farms with limited resources or no dedicated GPUs. Dulal et al. [

50] acknowledged that YOLOv5 outperformed Faster R-CNN and DETR (Detection Transformer) in terms of inference time and accuracy, thus further validating YOLO as a real-time cattle detector. This was advanced by Jo et al. [

28] who incorporated CBAM into YOLOv8. This attention-based detector was able to achieve a mAP@0.5 of 96.8%, surpassing Mask R-CNN and YOLOv5 in highly cluttered scenes. However, the energy efficiency and hardware adaptions needed for optimized energy savings would have to be addressed before any practical use of the system.

Guzhva et al. [

68] developed a method for the detection of cow heads and torsos using a rotated bounding box approach increasing their orientation and pose detection capabilities. Spatial clustering facilitated more accurate orientation identification. The use of watchdog mechanisms to prune irrelevant frames showcased a novel method for mitigating computation waste—an essential system design for battery-powered edge devices. Regardless, the influence of lighting and shadow artifacts significantly impacted performance, and thus, the generalizability is limited. Still, this method provides an important extension of moving from presence-based detection towards pose-informed spatial modeling. EfficientDet serves as a scalable detector, leveraging compound scaling with BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) alongside others, and is therefore considered less heavy as compared with YOLO. Tan et al. [

53] claims that EfficientDet surpasses YOLOv3 and RetinaNet in FLOPs Per accuracy making it exceedingly fit for mobile and embedded systems. Its effectiveness in human detection propelled its use beyond the scope of reliance, to non-human domains, farm animals included. Nonetheless, the accuracy it needs to perform under the specific visual constraints of a barn remains largely untested, hence, needing dedicated benchmarking against livestock datasets. Efforts toward 3D cattle detection remain in their infancy, while 2D object detection remains the dominant focus. Zhang et al. [

34] compared PETRv2 (Position Embedding Transformation) and TransFusion-L, both 3D object detectors, with Faster R-CNN for cattle use cases. While these models are pose attentive and offer good depth perception, their exceedingly high resource demand and structured environment dependence renders them unsuitable for large scale deployment in dairy barns.

One limitation that many studies on object detection share is the use of homogeneous datasets, as they tend to overstate precision while underestimating the variability of real-world conditions. Arulprakash et al. [

40] and Zaidi et al. [

41] strongly advocate for cross-domain testing, especially the transition from pristine datasets to unstructured barn settings. They also strongly advocate for hybrid pipelines that combine different detection strategies (e.g., 2D YOLO + 3D PETR + attention modules) and completely cross-determine across breed and illumination and camera angles and views. Mon et al. [

49] presented an elementary multi-stage pipeline consisting of YOLOv5x, VGG16x, and SVM/Random Forest classifiers. However, they also pointed out that their system was highly sensitive to unknown cattle and suffered from ID drift during occlusions, which is a fundamental problem for social network inference that requires reliable identity continuity.

5.2. Rise of Smart Farms and Automated Data Acquisition

Although object detection forms the computational core of cattle monitoring systems, it is clear from recent literature that detection alone is far from being sufficient for enabling intelligent behavioral or socially aware models. Object detectors declare presence of “who is here” but, in the absence of tracking, continuity, pose semantics, and social interactions remain highly opaque. Wang et al. [

51] highlights this drawback by incorporating YOLOv7 detection modules with tracking and behavior recognition systems, thus deepening the understanding of cattle motion and interactions. Jo et al. [

28] builds further on this by adding keypoint detection immediately after YOLOv8, which is followed by pose estimation and behavior analysis, marking an extension of object detection to behavior cognition.

Tracking systems should maintain the cattle’s identity through occlusion and reappearance scenarios across frames. Yi et al. [

69] proposed a single object tracking framework that dynamically combines detection and tracking, where the detector is used to reset identity after a tracking failure. Lyu et al. [

70] builds on this approach to emphasize instance-level re-ID (re-identification) for ensuring continuity in groups for SNA. Unsurprisingly, the focus on integrated and automated systems, is a common thread across different works and multiple. Dendorfer et al. [

63] support the integration of tracking, detection, and pose estimation toward a single predictive engine, where modeling of appearance and trajectory works in parallel. Zaidi et al. [

41] and Arulprakash et al. [

40] make similar claims for hybrid object detection pipelines that combine object detection with scene understanding, pose interpretation and multi-object tracking, thereby enriching system-level intelligence by making it spatial and subject aware. From a behavioral perspective, Gupta et al. [

71] and Wang et al. [

72] advocate the integration of video-based identification systems with open-set re-ID frameworks and tracking, which allows continuous behavior monitoring of both familiar and unfamiliar subjects. Yu et al. [

73] and Mon et al. [

42] have explored identity tracking and extended it further into pose estimation and behavior classification, thereby creating a full pipeline from visual presence to social action inference.

As noted by Tan et al. [

53], even efficiently scalable detectors such as EfficientDet can be extended to pose estimation and multi-object tracking which implies a modular framework for deployment in real world scenarios. Furthermore, Qiao et al. [

36], Qiao et al. [

37] propose the fusion of identification with activity recognition—linking who the cow is and what the cow is doing—which is fundamental for the automated construction of social networks. In sum, the literature strongly supports the view that object detection is not be treated as an isolated task, but rather a first layer and a starting point of a more complex system for automated reasoning, which encompasses the integration with identity persistence, motion continuity, keypoint extraction, and labeling behaviors.

6. Tracking and Identity Integration Based on Prediction

Cattle often disappear behind obstacles, move through crowded barns, and interact closely with one another, resulting in occlusions. A combination of tracking and detection is necessary in order to achieve continuity across space and time. Thus, detection must evolve into systems that can predict, interpolate, and re-identify animals in sophisticated scenarios. As such, the integration of models based on prediction tracking has surfaced as a focal solution for maintaining behavioral interpretation and long-term identity preservation. Notable contributions were made by Chen et al. [

74] with their work on template-matching trackers which update object appearance models via weighted interpolation between two frames. By brute force computing the pairs of all nearby bounding boxes, they severely limited robust tracking under motion blur and partial occlusion. This approach illustrates how ineffective static frame-wise detection is for sustaining identity across varying scenes.

Building on this, Lyu et al. [

70] incorporated pretrained detectors into regression-based trackers with correlation layers and achieved more stable box updates over time. Their model performance improved by ~5% mAP, strongly supporting the value of learned temporal features over simple sequential detection.

In a more structurally sophisticated framework, Wang et al. [

66] incorporated a Graph Neural Network (GNN) to unify detection in multi-object tracking. This system, which was trained in an end-to-end fashion with both classification and contrastive loss, showed improvement in IDF1 and HOTA scores meaning identity association and consistency was better. Noteworthily, GNN’s message-passing paradigm which captures object relationships across time robustly provides a key advantage for this model in interaction-rich barn settings. Notably, Tassinari et al. [

58] came up with a YOLOv4-based displacement tracker. While it offers a functional lower bound, its lack of predictive mechanisms highlights the problem with naive frame-to-frame tracking, especially in action-dense settings.

To conclude, these models help illustrate that moving from detection to predicting tracking is not simply a matter of performance improvement, but rather a shift of paradigm — a fundamental approach and a conceptual necessity. A key shortcoming of systems relying solely on detection is the absence of behavioral modeling in longitudinal approaches, particularly in cluttered or occluded farm environments. However, after considering the latter, it is obvious the models of Wang et al. [

66] and Lyu et al. [

70] demonstrate the great need for and possibility of integrated detection-tracking pipelines.

7. Object Tracking in Cattle Monitoring

Tracking an object is particularly important in collecting data for SNA since it allows accurate identification of cow movements based on time stamps throughout the period of observation. Maintaining a single identity over the course of time is important on detecting proximities, affiliative bonds and even dominance structures. Advances in visual tracking recently experienced a shift from rule-based trackers and sensor fusion approaches to end-to-end trained architectures capable of continuous and real-time monitoring.

7.1. Vision-Based Tracking Systems for SNA

Most traditional approaches to tracking in cattle monitoring systems relied to focus on sensor-vision fusion. For example Ren et al. [

75] used UWB tags integrated with computer vision for cow localization, while interaction detection at feeding points was done through a camera. This approach well served its purpose, but the infrastructure-based nature of its implementation restricts scalability.

On the other hand, Ozella et al. [

76] removed the sensors: object detection was performed at top-down views with EfficientDet and cow identity was maintained through Euclidean tracking. Importantly, lost track re-identification was done through trajectory synchronization with milking parlor exits. This illustrates the potential of vision-only systems for automated long-term monitoring of large herds (240 cows in this case) in real time. Though the method relied on predefined infrastructure (milking parlor exit times) for track reidentification, this is something intrinsic with modernized farms and is thus not impractical.

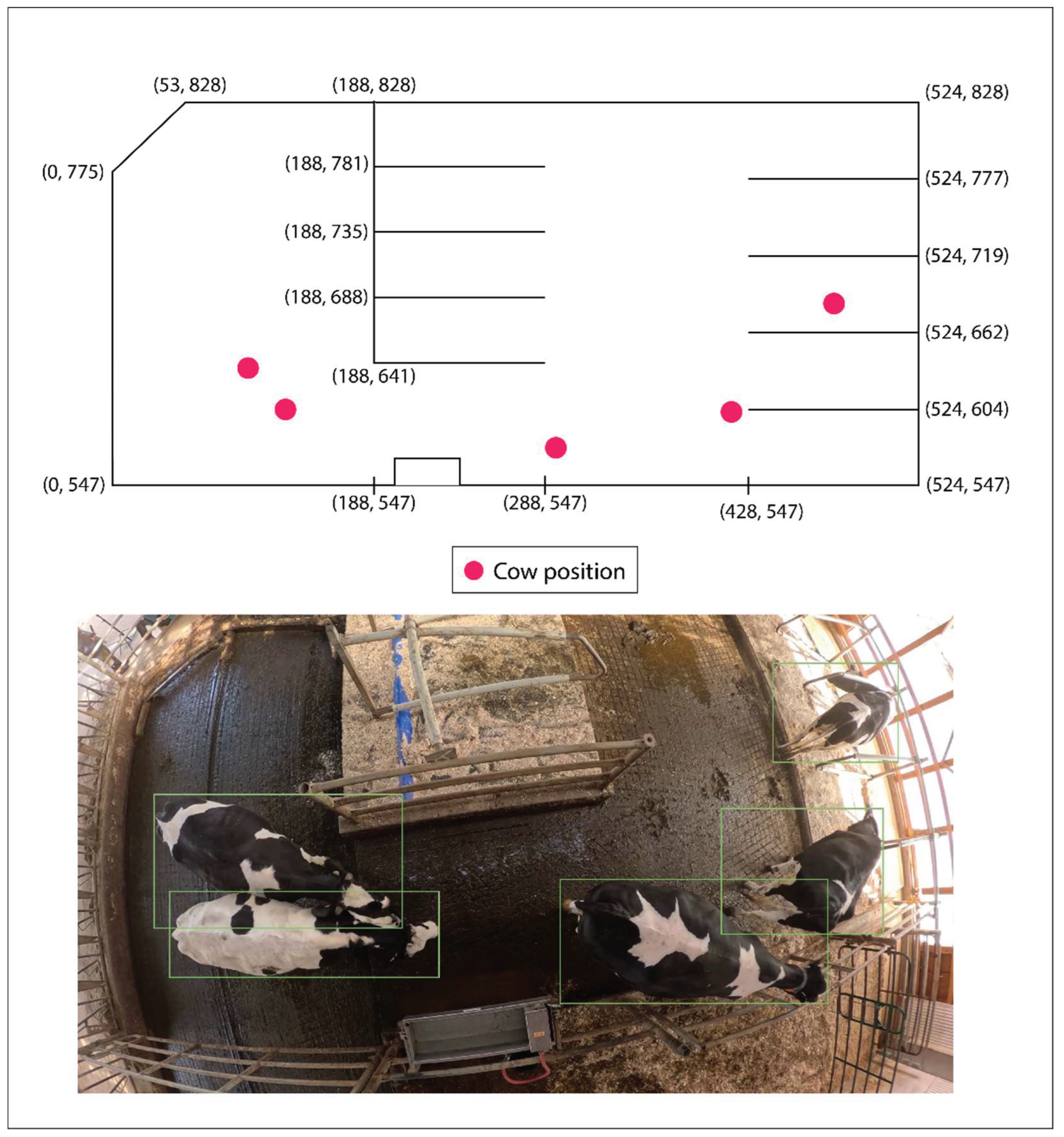

Figure 6.

Example barn layout depicting real-time tracking of a small group of cows. The figure shows how cows’ locations and movements within the barn are monitored continuously, aiding in assessing their social interactions and daily activities.

Figure 6.

Example barn layout depicting real-time tracking of a small group of cows. The figure shows how cows’ locations and movements within the barn are monitored continuously, aiding in assessing their social interactions and daily activities.

Mar et al. [

77] enhanced vision-only systems using a multi-feature tracker that integrated spatial location, appearance features (color, texture), and CNN embeddings. In their pipeline, detection was achieved using YOLOv5 and ID tracking was performed with multi-feature association, gaining 95.6% detection accuracy alongside estimated tracking accuracy of 90%. Nonetheless, performance suffered greatly due to severe occlusion, underscoring a major challenge of MOT (Multi-Object Tracking) systems: identity fragmentation within cluttered scenes.

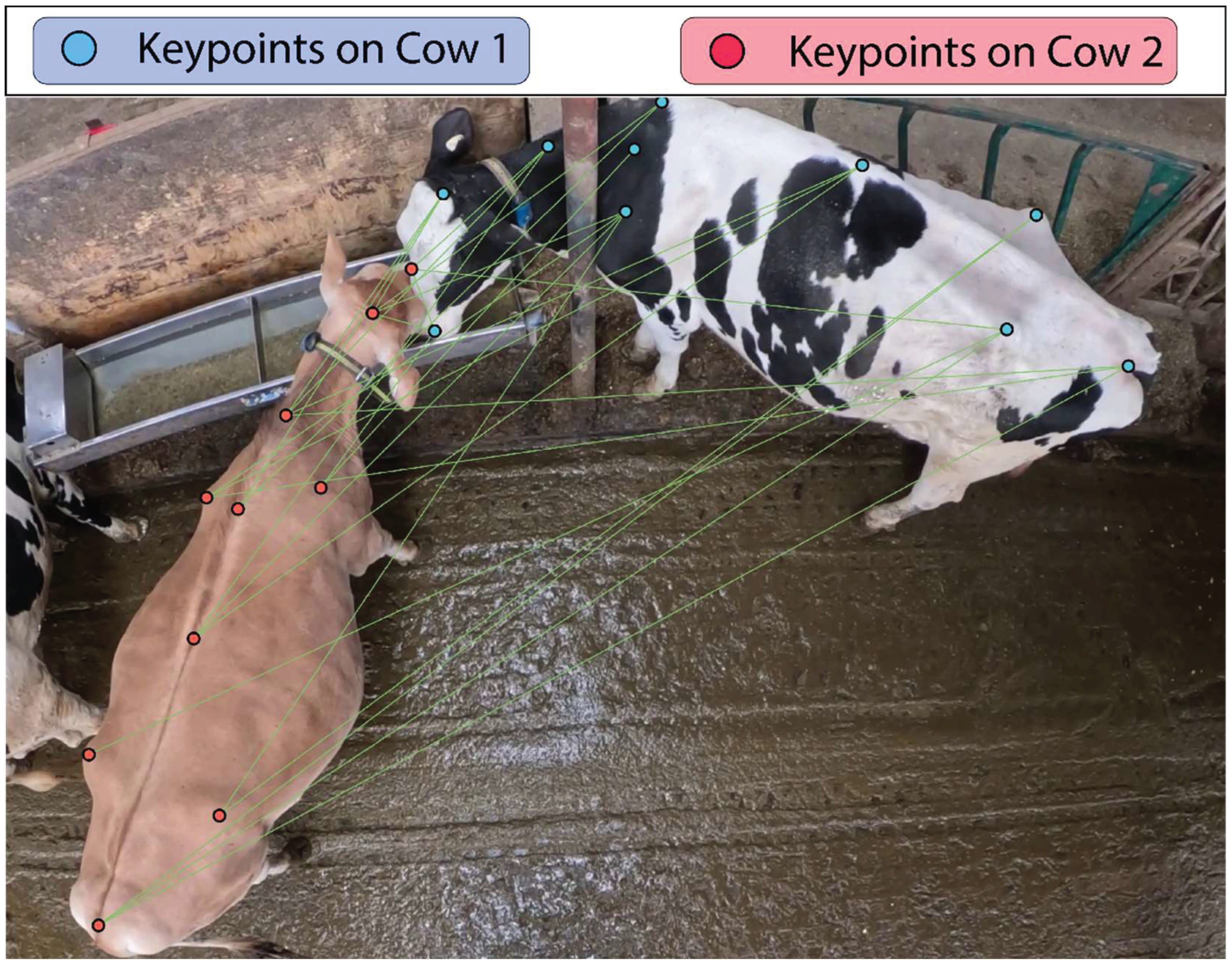

7.2. Orientation, Keypoints, and Interaction-Aware Tracking

Keypoint-guided tracking has been particularly useful for estimating cow posture, social interactions as well as direction of movement in relation to herd. Guzhva et al. [

78] proposed a rotated bounding box detector based on head, tail, and torso localização. From the probabilistic model and orientation information derived from keypoints, next frame locations were predicted. Identity tracking was solved using a greedy NMS algorithm. Moreover, their watchdog filtering logic provided a means to for up to 50% irrelevant footage cut while losing only 4% of the meaningful interactions. This shows that intelligent pre-filtering significantly streamlines the entire annotation process without compromising behavioral data.

7.3. Deep Affinity Networks and Graph-Based Association

Track-by-detection models frequently suffer from fragmented identities caused by occlusions or missed detections. Liu et al.’s [

79] work introduced a design of a Deep Affinity Network (DAN) which learns feature embeddings for detected objects and calculates pairwise affinities for object association across successive frames. The system managed entry, reentry and exit of objects robustly as well, which enabled its use in the crowded barns scenario with complicated trajectory movements.

Wang et al. [

80] built upon this by introducing a graph-based formulation of tracking with min-cost flow optimization. Their innovation, muSSP (Minimum-Update Successive Shortest Path), applied a graph matching approach paired with a minimum-path graph finding algorithm for bounding box position alignment across two successive frames. By avoiding recalculations in parts of the tracking graph with stable associations, a lot of unnecessary computation reduced acting similar to a high-level graph-based optimization on DAN. It achieved between 5—337-fold acceleration over previous methods while still ensuring optimal association quality. This greatly enhances the real-time computational feasibility of large-scale herd monitoring.

7.4. Hybrid Tracking Models: Motion + Detection Fusion

Guzhva et al. [

68] designed and used CNN-based tracking with visual markers in top-down views of barns as he managed to track 23 out of 26 cows for an average of 225 seconds per session, even in mildly crowded scenes. However, occlustions and visual ambiguity posed as major limiting factors particularly in dense scenarios.

Yi et al. [

69] further validated validated the use of CNN-based tracking by creating a hybrid Single-Object Tracker (SOT) which combined CNN-based correlation filter and optical flow motion compensation. Regular motion was dealt with by the tracker, while a cascade classifier embedded detector dealt with more complex scenarios involving drifts or occlusion events. Their design enhances recovery from tracking failures quite well, and it was tested on standard benchmarks OTB-2013/2015 (Object Tracking Benchmark) and VOT2016 (Visual Object Tracking Challenge).

Complementary to this, Tan et al. [

53] pointed out real time detectors like EfficientDet can be adapted for multi-object tracking and pose estimation, which shows how multi-purpose detector frameworks can be redefined to end-to-end tracking systems for track-and-vision integration.

7.5. End-to-End Architectures for Joint Detection and Tracking

Several modern tracking systems tend to prefer joint tackling of detection and association-based problems, also known as tracking-by-deep-learning. Wang et al. [

48] proposed the Joint Detection and Association Network (JDAN) comprised of: An anchor-free detection head An association head with attention-based feature matching JDAN, having been trained on MOT16 and MOT17, outperformed dual-stage baselines on both MOTA and IDF1, offering greater consistency in identity retention and fewer ID switches, even in occluded scenarios. Nonetheless, testing on actual footage from the barn wasn’t done for this model, marking a gap in practical verification as a key limitation.

7.6. State-of-the-Art Models: ByteTrackV2 and Beyond

In scenes of high density which contributes to the failure case scenario of most tracking systems, ByteTrackV2 [

34] has emerged as a benchmark. It retains low-confidence detections that are usually discarded by other pipelines, thus enabling continuity of trajectories under occlusion and motion blur. With both 2D and 3D tracking capabilities, it leads the nuScenes and HiEve benchmarks for performance, effectiveness and accuracy, and even stands as a candidate for realtime deployment in barns. ByteTrackV2’s performance could be enhanced with spatio-temporal modeling by employing transformers.

Also, its active focus on edge devices with low power requirements fits the constraints of on-farm usage. Furthermore, its combination of motion and Kalman filtering provides better continuity for smoother long-term tracking. To resolve identity switches in occluded or crowded barn scenarios, the use of multi-camera fusion with epipolar geometry constraints offers a promising solution. Using the knowledge of barn layout and camera geometry, it is possible to perform preprocessing and consistently triangulate identities across views which helps eliminate fragmentation.

7.7. Tracking Benchmarks: A Caution on Generalizability

Some of the tracking systems tested under more academic conditions used datasets designed for humans, such as MOT17, MOT20, and OTB2015. As pointed out by Dendorfer et al. [

63] and Wang et al. [

48], these seemingly robust trackers, which perform well in their specific benchmarks, perform poorly in barn environments due to: Higher levels of occlusion, Irregular trajectories, Lower contrast (e.g., black cattle [

57]), Non-rigid body deformation. As an example, trackers that relatively excelled on MOT17 suffered a 10-15% accuracy drop on the more dense MOT20 benchmark [

81]. This difference is problematic because it suggests that models trained in a lab aren’t necessarily robust enough to be freely adapted for use in agriculture.

To conclude, AI and sensors are now being used to fully automate monitoring of cattle, gradually shifting from outdated manual and semi-automated systems. Although vision-based systems and sensor-based systems each have their own unique advantages, their integration along with better data infrastructure and better annotation holds significant promise for constructing sophisticated, intelligent, and welfare-oriented farm management systems.

Now that the foundational network behaviors and sociability patterns are mapped and established, it is necessary to explore the computational backbone driving these systems. The next section investigates self-organized neural networks which observe, interpret, predict, and quantify cow behaviors, positions, and interactions at a fundamental level vital for the formation of social networks.

The development of cattle tracking systems indicates a clear shift towards multimodal, predictive, and identity-aware systems. Systems relying on traditional feature matching have been replaced by more advanced and robust architectures like DAN [

79], JDAN [

48], and ByteTrackV2 [

34] that perform better under occlusion and crowding. Models still struggle with identity persistence over time, pose-informed tracking, and cross-farm generalization. Since social behaviour of cattle is highly context dependent, tracking systems need to further integrate: Keypoint and pose estimation [

78], Behavioral prediction [

43], Multi-camera fusion [

46], And end device optimization for barn deployment in real-time.

8. Object Identification in Dairy Cows: Approaches, Architectures, and Advances