Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

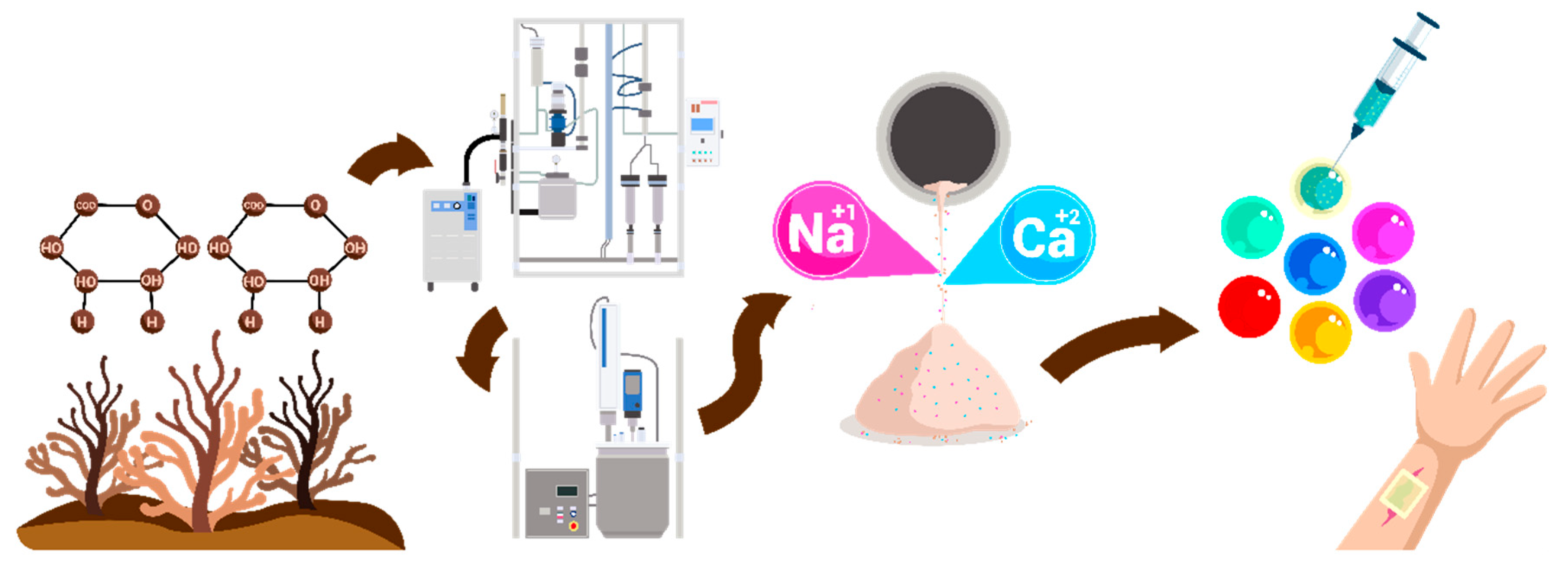

2. Alginates

2.1. Sources of Alginates and Compositional Variability

2.2. Conventional Alginate Extraction Methods

2.3. Purification Techniques for Pharmaceutical-Grade Alginates

2.4. Challenges and Future Perspectives in Alginate Extraction and Purification

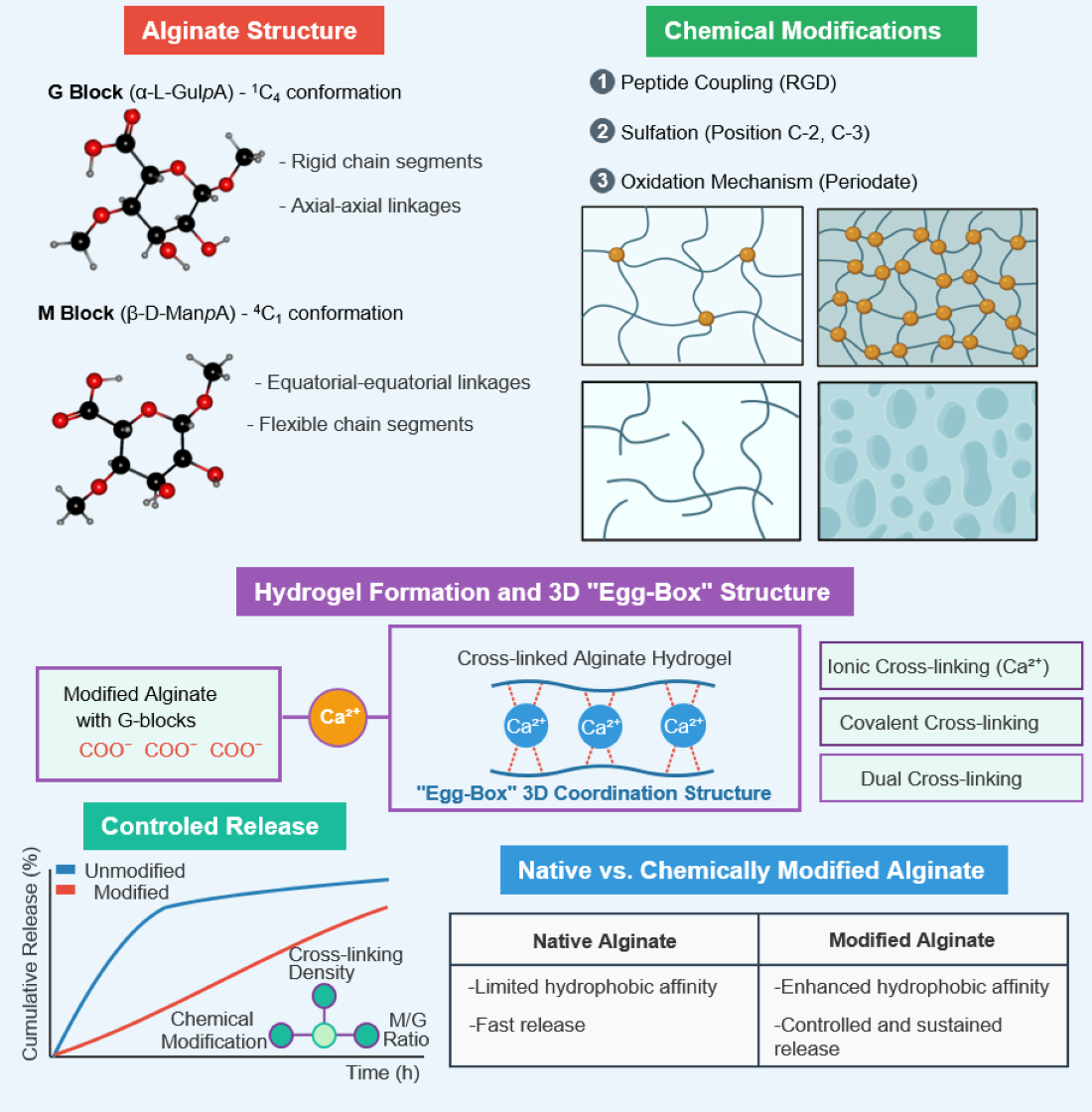

3. Physicochemical Properties of Alginate

4. Functional Properties of Alginates

4.1. Gelling Properties

4.2. Rheological Properties

4.3. Porosity and Permeability Properties

4.4. Water Retention, Syneresis and Swelling Properties

4.5. Release Properties

4.6. Biodegradability and Biocompatibility Properties

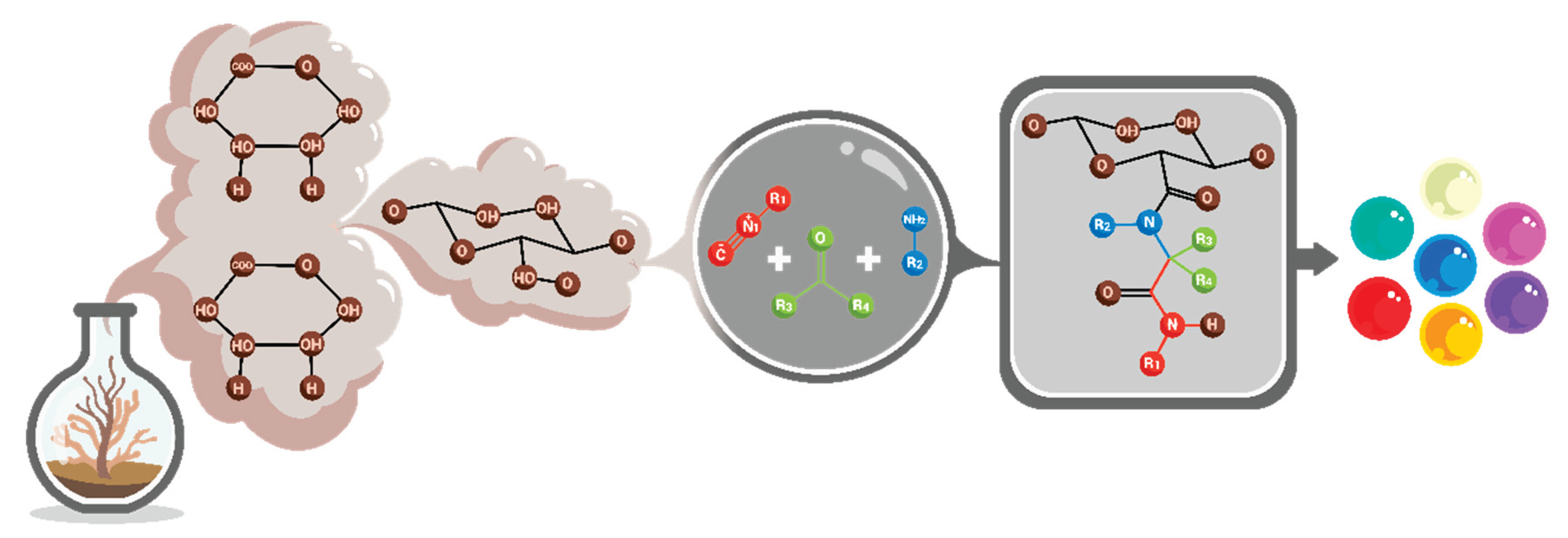

5. Alginate Modification Methods

5.1. Physical Modification

5.2. Chemical Modification

5.3. Enzymatic Modification

6. Application of Chemically Modified Alginate in Drug Release

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| M | β-D-mannuronic acid |

| G | α-L-guluronic acid |

| HCl | hydrochloric acid |

| H2SO4 | sulfuric acid |

| NaOH | sodium hydroxide |

| Na2CO3 | sodium carbonate |

| CaCl2 | calcium chloride |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| MW | molecular weight |

| HPSEC | High-Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography |

| G’ | viscous modulus |

| G” | elastic modulus |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| CNC | cellulose nanocrystal |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ADA | aldehyde alginate |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

References

- Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Cortés-Camargo, S.; Velázquez-Gutiérrez, S.K.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Recent Approaches in Alginate-Based Carriers for Delivery of Therapeutics and Biomedicine. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Camargo, S.; Román-Guerrero, A.; Alvarez-Ramirez, J.; Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Velázquez-Gutiérrez, S.K.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Microstructural Influence on Physical Properties and Release Profiles of Sesame Oil Encapsulated into Sodium Alginate-Tamarind Mucilage Hydrogel Beads. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2023, 5, 100302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Soratur, A.; Kumar, S.; Venmathi Maran, B.A. A Review of Marine Algae as a Sustainable Source of Antiviral and Anticancer Compounds. Macromol 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draget, K.I.; Taylor, C. Chemical, Physical and Biological Properties of Alginates and Their Biomedical Implications. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, M.M.A.; Borges, J.; Correia, F.J.S.; Calado, R.; Rodrigues, J.M.M.; Patrício, S.G.; Mano, J.F. Green Approaches for Extraction, Chemical Modification and Processing of Marine Polysaccharides for Biomedical Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, X.; McClements, D.J.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C.; Li, G. Plant-Based Delivery Systems for Controlled Release of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Active Ingredients: Pea Protein-Alginate Bigel Beads. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 154, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, A.; Florowska, A.; Wroniak, M. Binary Hydrogels: Induction Methods and Recent Application Progress as Food Matrices for Bioactive Compounds Delivery—A Bibliometric Review. Gels 2023, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Gutiérrez, S.K.; Alpizar-Reyes, E.; Guadarrama-Lezama, A.Y.; Báez-González, J.G.; Alvarez-Ramírez, J.; Pérez-Alonso, C. Influence of the Wall Material on the Moisture Sorption Properties and Conditions of Stability of Sesame Oil Hydrogel Beads by Ionic Gelation. LWT 2021, 140, 110695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Dong, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, H.; He, Y.; Ren, D.; Li, X.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, L. Highly Crystalline Cellulose Microparticles from Dealginated Seaweed Waste Ameliorate High Fat-Sugar Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia in Mice by Modulating Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Park, K. Environment-Sensitive Hydrogels for Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 53, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombotz, W.R.; Wee, S.F. Protein Release from Alginate Matrices. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertah, M.; Belfkira, A.; Dahmane, E. montassir; Taourirte, M.; Brouillette, F. Extraction and Characterization of Sodium Alginate from Moroccan Laminaria digitata Brown Seaweed. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, S3707–S3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Q.; Azhar, M.A.; Munaim, M.S.A.; Ruslan, N.F.; Ahmad, N.; Noman, A.E. Recent Advances in Edible Seaweeds: Ingredients of Functional Food Products, Potential Applications, and Food Safety Challenges. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, C.; Ravishankar, G.A.; Rao, A.R. Potential Products from Macroalgae: An Overview. Sustain. Glob. Resour. Seaweeds Vol. 1 Bioresour. Cultiv. Trade Multifarious Appl. 2022, 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bixler, H.J.; Porse, H. A Decade of Change in the Seaweed Hydrocolloids Industry. J. Appl. Phycol. 2010, 23, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A.; Volesky, B.; Mucci, A. A Review of the Biochemistry of Heavy Metal Biosorption by Brown Algae. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4311–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.J. A Guide to the Seaweed Industry. 2003.

- Arvizu-Higuera, D.L.; Rodríguez-Montesinos, Y.E.; Murillo-Álvarez, J.I.; Muñoz-Ochoa, M.; Hernández-Carmona, G. Effect of Alkali Treatment Time and Extraction Time on Agar from Gracilaria vermiculophylla. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ordóñez, E.; Rupérez, P. FTIR-ATR Spectroscopy as a Tool for Polysaccharide Identification in Edible Brown and Red Seaweeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carmona, G.; McHugh, D.J.; Arvizu-Higuera, D.L.; Rodríguez-montesinos, Y.E. Pilot Plant Scale Extraction of Alginate from Macrocystis pyrifera. 1. Effect of Pre-Extraction Treatments on Yield and Quality of Alginate. J. Appl. Phycol. 1998, 10, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nøkling-Eide, K.; Langeng, A.-M.; Åslund, A.; Aachmann, F.L.; Sletta, H.; Arlov, Ø. An Assessment of Physical and Chemical Conditions in Alginate Extraction from Two Cultivated Brown Algal Species in Norway: Alaria esculenta and Saccharina latissima. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Carmona, G.; McHugh, D.J.; López-Gutiérrez, F. Pilot Plant Scale Extraction of Alginates from Macrocystis pyrifera. 2. Studies on Extraction Conditions Andmethods of Separating the Alkaline-Insoluble Residue. J. Appl. Phycol. 1999, 11, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidsrød, O.; Haug, A. Dependence upon Uronic Acid Composition of Some Ion-Exchange Properties of Alginates. Acta Chem Scand 1968, 22, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Díaz, D.; Navaza, J.M. Rheology of Aqueous Solutions of Food Additives: Effect of Concentration, Temperature and Blending. J. Food Eng. 2003, 56, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.A.; Do Yoon, S.; Lee, C.-M. A Drug Release System Induced by near Infrared Laser Using Alginate Microparticles Containing Melanin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, S.E.; Hatamipour, M.S.; Yegdaneh, A. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Alginic Acid from Sargassum Angustifolium Harvested from Persian Gulf Shores Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Shi, C.; Zi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhong, J. A Review on the Chemical Modification of Alginates for Food Research: Chemical Nature, Modification Methods, Product Types, and Application. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Fernández, N.; Domínguez, H.; Torres, M.D. Advances in the Biorefinery of Sargassum Muticum: Valorisation of the Alginate Fractions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 138, 111483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A.; Aljabali, A.A.; Mishra, V.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Alginate: Enhancement Strategies for Advanced Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Ballester, N.M.; Bataille, B.; Soulairol, I. Sodium Alginate and Alginic Acid as Pharmaceutical Excipients for Tablet Formulation: Structure-Function Relationship. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 270, 118399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-Khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, S.; Karim, S.; Aslam, S.; Jahangeer, M.; Nelofer, R.; Nadeem, A.A.; Qamar, S.A.; Jesionowski, T.; Bilal, M. Alginate-based Bio-nanohybrids with Unique Properties for Biomedical Applications. Starch-Stärke 2024, 76, 2200100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.N. Chemical Modification of Alginate. Seaweed Polysacch. 2017, 111–155. [Google Scholar]

- Borazjani, N.J.; Tabarsa, M.; You, S.; Rezaei, M. Effects of Extraction Methods on Molecular Characteristics, Antioxidant Properties and Immunomodulation of Alginates from Sargassum Angustifolium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawzy, M.A.; Gomaa, M.; Hifney, A.F.; Abdel-Gawad, K.M. Optimization of Alginate Alkaline Extraction Technology from Sargassum Latifolium and Its Potential Antioxidant and Emulsifying Properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Gheda, S.F.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J. Analysis by Vibrational Spectroscopy of Seaweed Polysaccharides with Potential Use in Food, Pharmaceutical, and Cosmetic Industries. Int. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2013, 2013, 537202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Vicini, S.; Alloisio, M.; Castellano, M. Sodium Alginate Solutions: Correlation between Rheological Properties and Spinnability. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 8034–8046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, A.C.; Téllez-Jurado, L.; Rodríguez-Lorenzo, L.M. Alginate Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering, from Injectables to Bioprinting: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Cao, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J. Molecular Weight Distribution, Rheological Property and Structural Changes of Sodium Alginate Induced by Ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Vicini, S.; Alloisio, M.; Castellano, M. Rheological Properties of Sodium Alginate Solutions in the Presence of Added Salt: An Application of Kulicke Equation. Rheol. Acta 2020, 59, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-Khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentati, F.; Delattre, C.; Ursu, A.V.; Desbrières, J.; Le Cerf, D.; Gardarin, C.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P.; Pierre, G. Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Water-Soluble Polysaccharides from the Tunisian Brown Seaweed Cystoseira compressa. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K.; Kurakula, M.; Hoda, M.N. Alginate Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery. In Alginates in Drug Delivery; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 129–152.

- Ray, P.; Maity, M.; Barik, H.; Sahoo, G.S.; Hasnain, M.S.; Hoda, M.N.; Nayak, A.K. Alginate-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery Applications. In Alginates in drug delivery; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 41–70.

- Rostami, Z.; Tabarsa, M.; You, S.; Rezaei, M. Relationship between Molecular Weights and Biological Properties of Alginates Extracted under Different Methods from Colpomenia peregrina. Process Biochem. 2017, 58, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellimi, S.; Younes, I.; Ayed, H.B.; Maalej, H.; Montero, V.; Rinaudo, M.; Dahia, M.; Mechichi, T.; Hajji, M.; Nasri, M. Structural, Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Sodium Alginate Isolated from a Tunisian Brown Seaweed. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsa, P.V.; Aswathy, K.N.; Viswanad, V. Alginates in Drug Delivery Systems. In Natural biopolymers in drug delivery and tissue engineering; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 25–55.

- Sarkar, N.; Maity, A. Modified Alginates in Drug Delivery. In Tailor-made polysaccharides in drug delivery; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 291–325.

- Goh, C.H.; Heng, P.W.S.; Chan, L.W. Alginates as a Useful Natural Polymer for Microencapsulation and Therapeutic Applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belalia, F.; Djelali, N.-E. Rheological Properties of Sodium Alginate Solutions. Rev Roum Chim 2014, 59, 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, T.E.; Sletmoen, M.; Draget, K.I.; Stokke, B.T. Influence of Oligoguluronates on Alginate Gelation, Kinetics, and Polymer Organization. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 2388–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojorges, H.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Martínez-Sanz, M.; Rodrigo, M.D.; Vilaplana, F.; López-Rubio, A.; Fabra, M.J. Structural and Functional Properties of Alginate Obtained by Means of High Hydrostatic Pressure-Assisted Extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 299, 120175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidarra, S.J.; Barrias, C.C.; Granja, P.L. Injectable Alginate Hydrogels for Cell Delivery in Tissue Engineering. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 1646–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, S.H.; Bansal, N.; Bhandari, B. Alginate Gel Particles–A Review of Production Techniques and Physical Properties. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, J.; Pereira, A.M.; Bidarra, S.J.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Granja, P.L.; Coelho, J.F.; Barrias, C.C.; Seiça, R. ECM-Enriched Alginate Hydrogels for Bioartificial Pancreas: An Ideal Niche to Improve Insulin Secretion and Diabetic Glucose Profile. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2019, 17, 2280800019848923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Dutta, S.; Nayak, A.K.; Nanda, U. Zinc Alginate-Carboxymethyl Cashew Gum Microbeads for Prolonged Drug Release: Development and Optimization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 70, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, L.; Di, Y.; Wang, L.; Di, L. A Gellan Gum/Sodium Alginate-Based Gastric-Protective Hydrogel Loaded with a Combined Herbal Extract Consisting of Panax Notoginseng, Bletilla striata and Dendrobium officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.K.; Das, B.; Maji, R. Calcium Alginate/Gum Arabic Beads Containing Glibenclamide: Development and in vitro Characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2012, 51, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baú, R.Z.; Dávila, J.L.; Komatsu, D.; d’Avila, M.A.; Gomes, R.C.; de Rezende Duek, E.A. Influence of Hyaluronic Acid and Sodium Alginate on the Rheology and Simvastatin Delivery in Pluronic-Based Thermosensitive Injectable Hydrogels. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 88, 104888. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, T.; Flores, C.; Salgado-Lugo, H.; Peña, C.F.; Galindo, E. Alginate and γ-Polyglutamic Acid Hydrogels: Microbial Production Strategies and Biomedical Applications. A Review of Recent Literature. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 66, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrah, R.M.; Potes, M.D.A.; Vitija, X.; Durrani, S.; Ghaith, A.K.; Mualem, W.; Zamanian, C.; Bhandarkar, A.R.; Bydon, M. Alginate Hydrogels: A Potential Tissue Engineering Intervention for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 113, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Sharma, M.; Devi, M. Hydrogels: An Overview of Its Classifications, Properties, and Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 147, 106145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Roy, S.; Hasnain, M.S.; Nayak, A.K. Grafted Alginates in Drug Delivery. In Alginates in drug delivery; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 71–100.

- Putro, J.N.; Soetaredjo, F.E.; Santoso, S.P.; Irawaty, W.; Yuliana, M.; Wijaya, C.J.; Saptoro, A.; Sunarso, J.; Ismadji, S. Jackfruit Peel Cellulose Nanocrystal–Alginate Hydrogel for Doripenem Adsorption and Release Study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 257, 128502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zongrui, T.; Yu, C.; Wei, L. Grafting Derivate from Alginate. In Biopolymer Grafting; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 115–173.

- Raghav, N.; Vashisth, C.; Mor, N.; Arya, P.; Sharma, M.R.; Kaur, R.; Bhatti, S.P.; Kennedy, J.F. Recent Advances in Cellulose, Pectin, Carrageenan and Alginate-Based Oral Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 244, 125357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.; Sugiyama, M.; Annaka, M.; Hara, Y.; Okano, T. Microscopic Implication of Rapid Shrinking of Comb-Type Grafted Poly (N-Isopropylacrylamide) Hydrogels. Polymer 2003, 44, 4405–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.-H.; Pan, X.-R.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, L.-Y.; Xie, W.-G.; Long, Z.-H.; Zheng, H. Preparation and Characterization of Crosslinked Carboxymethyl Chitosan–Oxidized Sodium Alginate Hydrogels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 122, 2331–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.K.T.; Matia-Merino, L.; Chiang, J.H.; Quek, R.; Soh, S.J.B.; Lentle, R.G. The Physico-Chemical Properties of Chia Seed Polysaccharide and Its Microgel Dispersion Rheology. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 149, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, B.; Rompf, J.; Silva, R.; Lang, N.; Detsch, R.; Kaschta, J.; Fabry, B.; Boccaccini, A.R. Alginate-Based Hydrogels with Improved Adhesive Properties for Cell Encapsulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 78, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimmestad, M.; Steigedal, M.; Ertesvåg, H.; Moreno, S.; Christensen, B.E.; Espín, G.; Valla, S. Identification and Characterization of an Azotobacter vinelandii Type I Secretion System Responsible for Export of the AlgE-Type Mannuronan C-5-Epimerases. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5551–5560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.B.; Struszczyk-Swita, K.; Li, X.; Szczęsna-Antczak, M.; Daroch, M. Enzymatic Modifications of Chitin, Chitosan, and Chitooligosaccharides. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saikia, C.; Gogoi, P.; Maji, T.K. Chitosan: A Promising Biopolymer in Drug Delivery Applications. J Mol Genet Med S 2015, 4, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialik-Wąs, K.; Pluta, K.; Malina, D.; Majka, T.M. Alginate/PVA-Based Hydrogel Matrices with Echinacea Purpurea Extract as a New Approach to Dermal Wound Healing. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2021, 70, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherbiny, I.M. Enhanced pH-Responsive Carrier System Based on Alginate and Chemically Modified Carboxymethyl Chitosan for Oral Delivery of Protein Drugs: Preparation and in-vitro Assessment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 80, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriza, J.; Rodríguez-Romano, A.; Nogueroles, I.; Gallego-Ferrer, G.; Cabezuelo, R.M.; Pedraz, J.L.; Rico, P. Borax-Loaded Injectable Alginate Hydrogels Promote Muscle Regeneration in vivo after an Injury. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 123, 112003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paswan, M.; Chandel, A.K.S.; Malek, N.I.; Dholakiya, B.Z. Preparation of Sodium Alginate/Cur-PLA Hydrogel Beads for Curcumin Encapsulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 128005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezamdoost-Sani, N.; Khaledabad, M.A.; Amiri, S.; Khaneghah, A.M. Alginate and Derivatives Hydrogels in Encapsulation of Probiotic Bacteria: An Updated Review. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, S.G.; Post, V.; Foster, A.L.; Lavigne, R.; Wagemans, J.; Trampuz, A.; Moreno, M.G.; Metsemakers, W.-J.; Grijpma, D.W.; Richards, R.G. Alginate Chitosan Microbeads and Thermos-Responsive Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel for Phage Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 79, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tang, W.; Huang, X.-J.; Hu, J.-L.; Wang, J.-Q.; Yin, J.-Y.; Nie, S.-P.; Xie, M.-Y. Structural Characteristic of Pectin-Glucuronoxylan Complex from Dolichos lablab L. Hull. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 298, 120023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljawish, A.; Chevalot, I.; Jasniewski, J.; Scher, J.; Muniglia, L. Enzymatic Synthesis of Chitosan Derivatives and Their Potential Applications. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2015, 112, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, H.; Yang, S.; Zhao, W.; Che, L.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, K.; Qian, Z. Progress in the Application of 3D-Printed Sodium Alginate-Based Hydrogel Scaffolds in Bone Tissue Repair. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 152, 213501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhawiti, A.S.; Elsayed, N.H.; Almutairi, F.M.; Alotaibi, F.A.; Monier, M.; Alatwi, G.J. Construction of a Biocompatible Alginate-Based Hydrogel Cross-Linked by Diels–Alder Chemistry for Controlled Drug Release. React. Funct. Polym. 2023, 187, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghauri, Z.H.; Islam, A.; Qadir, M.A.; Ghaffar, A.; Gull, N.; Azam, M.; Mehmood, A.; Ghauri, A.A.; Khan, R.U. Novel pH-Responsive Chitosan/Sodium Alginate/PEG Based Hydrogels for Release of Sodium Ceftriaxone. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 277, 125456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Dantas, M.J.; F. dos Santos, B.F.; A. Tavares, A.; Maciel, M.A.; Lucena, B. de M.; L. Fook, M.V.; de L. Silva, S.M. The Impact of the Ionic Cross-Linking Mode on the Physical and In Vitro Dexamethasone Release Properties of Chitosan/Hydroxyapatite Beads. Molecules 2019, 24, 4510. [CrossRef]

- Hadef, I.; Omri, M.; Edwards-Lévy, F.; Bliard, C. Influence of Chemically Modified Alginate Esters on the Preparation of Microparticles by Transacylation with Protein in W/O Emulsions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Sosa, A.; Mercado-Rico, J.; Usala, E.; Cataldi, G.; Esteban-Arranz, A.; Penott-Chang, E.; Müller, A.J.; González, Z.; Espinosa, E.; Hernández, R. Composite Nano-Fibrillated Cellulose-Alginate Hydrogels: Effect of Chemical Composition on 3D Extrusion Printing and Drug Release. Polymer 2024, 298, 126845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, B. Preparation of Oxidized Sodium Alginate with Different Molecular Weights and Its Application for Crosslinking Collagen Fiber. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1650–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, Z.; Ehsani, M.; Zandi, M.; Foudazi, R. Controlling Alginate Oxidation Conditions for Making Alginate-Gelatin Hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yao, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.-M.; Wang, H.-X. Investigation on the Quality Diversity and Quality-FTIR Characteristic Relationship of Sunflower Seed Oils. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 27347–27360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlov, Ø.; Skjåk-Bræk, G. Sulfated Alginates as Heparin Analogues: A Review of Chemical and Functional Properties. Molecules 2017, 22, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazemi, Z.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Kiani, S.; Daemi, H.; Ashtiani, M.K.; Baharvand, H. Effect of Chemical Composition and Sulfated Modification of Alginate in the Development of Delivery Systems Based on Electrostatic Interactions for Small Molecule Drugs. Mater. Lett. 2020, 263, 127235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffleur, F.; Küppers, P. Adhesive Alginate for Buccal Delivery in Aphthous Stomatitis. Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 477, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, N.C.; Hallam, D.; Karimi, A.; Mellough, C.B.; Chen, J.; Steel, D.H.; Lako, M. 3D Culture of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells in RGD-Alginate Hydrogel Improves Retinal Tissue Development. Acta Biomater. 2017, 49, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, E.D.; Morais, M.R.; Pêgo, A.P.; Barrias, C.C.; Araújo, M. The Interplay between Chemical Conjugation and Biologic Performance in the Development of Alginate-Based 3D Matrices to Mimic Neural Microenvironments. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 323, 121412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Q. Electrolyte and pH-Sensitive Amphiphilic Alginate: Synthesis, Self-Assembly and Controlled Release of Acetamiprid. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32193–32199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.A.; Kim, H.-W. Core–Shell Designed Scaffolds of Alginate/Alpha-tricalcium Phosphate for the Loading and Delivery of Biological Proteins. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abasalizadeh, F.; Moghaddam, S.V.; Alizadeh, E.; Akbari, E.; Kashani, E.; Fazljou, S.M.B.; Torbati, M.; Akbarzadeh, A. Alginate-Based Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Vehicles in Cancer Treatment and Their Applications in Wound Dressing and 3D Bioprinting. J. Biol. Eng. 2020, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q.; Zhou, J.; An, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S. Modification, 3D Printing Process and Application of Sodium Alginate Based Hydrogels in Soft Tissue Engineering: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 232, 123450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, T.N.; Laowattanatham, N.; Ratanavaraporn, J.; Sereemaspun, A.; Yodmuang, S. Hyaluronic Acid Crosslinked with Alginate Hydrogel: A Versatile and Biocompatible Bioink Platform for Tissue Engineering. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 166, 111027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreller, T.; Distler, T.; Heid, S.; Gerth, S.; Detsch, R.; Boccaccini, A.R. Physico-Chemical Modification of Gelatine for the Improvement of 3D Printability of Oxidized Alginate-Gelatine Hydrogels towards Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Mater. Des. 2021, 208, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Song, F.; Wang, X.-L.; Wang, Y.-Z. Development of Soy Protein Isolate/Waterborne Polyurethane Blend Films with Improved Properties. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2012, 100, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.; Bidarra, S.J.; Alves, P.M.; Valcarcel, J.; Vazquez, J.A.; Barrias, C.C. Coumarin-Grafted Blue-Emitting Fluorescent Alginate as a Potentially Valuable Tool for Biomedical Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.T.; Palvai, S.; Brudno, Y. Click Cross-Linking Improves Retention and Targeting of Refillable Alginate Depots. Acta Biomater. 2020, 112, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, V.; Sood, A.; Kumari, S.; Kumaran, S.S.; Jain, T.K. Hydrophobically Modified Sodium Alginate Conjugated Plasmonic Magnetic Nanocomposites for Drug Delivery & Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 25, 101470. [Google Scholar]

- Somo, S.I.; Langert, K.; Yang, C.-Y.; Vaicik, M.K.; Ibarra, V.; Appel, A.A.; Akar, B.; Cheng, M.-H.; Brey, E.M. Synthesis and Evaluation of Dual Crosslinked Alginate Microbeads. Acta Biomater. 2018, 65, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Rajput, M.; Barui, A.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Pal, N.K.; Chatterjee, J.; Mukherjee, R. Dual Cross-Linked Honey Coupled 3D Antimicrobial Alginate Hydrogels for Cutaneous Wound Healing. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 116, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.D.; Naghieh, S.; McInnes, A.D.; Ning, L.; Schreyer, D.J.; Chen, X. Bio-Fabrication of Peptide-Modified Alginate Scaffolds: Printability, Mechanical Stability and Neurite Outgrowth Assessments. Bioprinting 2019, 14, e00045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of Alginate | Extraction Method | Purification Method | Characteristics of Alginate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laminaria digitata | Alkaline extraction | Precipitation with ethanol, dialysis | M/G ratio: 0.45, Molecular weight: 200-400 kDa, Viscosity: 200-400 mPa·s (1% solution) | [21] |

| Macrocystis pyrifera | Acid extraction | Precipitation with CaCl2, ultrafiltration | M/G ratio: 1.2, Molecular weight: 100-200 kDa, Viscosity: 100-200 mPa·s (1% solution) | [22] |

| Ascophyllum nodosum | Alkaline extraction | Precipitation with ethanol, activated carbon treatment | M/G ratio: 0.6, Molecular weight: 150-250 kDa, Viscosity: 150-250 mPa·s (1% solution) | [23] |

| Lessonia trabeculata | Alkaline extraction | Membrane filtration, dialysis | M/G ratio: 0.8, Molecular weight: 300-500 kDa, Viscosity: 500-700 mPa·s (1% solution) | [19] |

| Sargassum muticum | Enzymatic extraction | Precipitation with isopropanol, ion exchange | M/G ratio: 0.9, Molecular weight: 80-120 kDa, Viscosity: 50-100 mPa·s (1% solution) | [24] |

| Ecklonia cava | Acid extraction | Ultrafiltration, diafiltration | M/G ratio: 1.1, Molecular weight: 50-100 kDa, Viscosity: 20-50 mPa·s (1% solution) | [25] |

| Method | Description | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Addition of Aloe vera to a hydrogel composed of sodium alginate/polyvinyl alcohol. | Aloe vera improves the release properties of active substances because the material obtained has a rigid three-dimensional structure and is thermally stable. | [74] |

| Chemical | Mixture of sodium alginate and chitosan for the oral delivery of protein drugs | Development of hydrogel microspheres with protein-trapping capacity, sustained drug delivery profiles and controlled biodegradation. | [75] |

| Physical | Injectable alginate hydrogels by simultaneous stimulation of borax transporter and fibronectin-binding integrins for in vivo muscle regeneration | Increased formation of focal adhesions, increased area of cell expansion and improves myofiber fusion; enhanced and accelerated muscle regeneration was promoted. | [76] |

| Chemical | Sodium alginate hydrogel/Cur-PLA microspheres for the encapsulation of curcumin, a hydrophobic compound with limited bioavailability. | The new material is hemocompatible, cytocompatible and antimicrobial, improved swelling capacity and prolonged curcumin delivery time. It proved to be an option for improving curcumin bioavailability and its effective oral delivery. | [77] |

| Physical | Alginate hydrogels and their derivatives in the encapsulation of probiotic bacteria. | Increased protection of probiotics, increased bioavailability which improves their survival and transport to different parts of the body. Improved stability of probiotic bacteria under extreme temperature and dehydration conditions. | [78] |

| Other | Potential of HA-pNIPAM and alginate-chitosan thermo-sensitive hydrogels as phage delivery systems for the treatment of infections. | Modified alginate showed the most consistent and sustained delivery of bacteriophages over a 21-day period, highlighting the potential of these materials for both rapid, controlled and extended local delivery of bacteriophages. | [79] |

| Chemical | Fabrication of alginate fibers with polyether glycol (PEGDE) for improved mechanical performance | Significantly improved mechanical and thermal properties of alginate fibers. A PEGDE content of 15% in the modified fibers provides maximum tensile strength and elongation at break. | [80] |

| Enzymatic | Potential of enzymatically functionalized chitosan derivatives for medical and pharmaceutical applications, such as scaffold materials, coatings and gels. | Enzymes improved the properties of chitosan and create new materials with potential applications in fields such as tissue engineering, the food industry and bioelectronics. | [81] |

| Other | 3D printing for the manufacture of hydrogel scaffolds based on sodium alginate for cancellous and periosteal bone repair. | 3D printing improved the crosslinking efficiency, mechanical strength and biological properties of the hydrogel scaffolds, while maintaining the inherent properties of sodium alginate. | [82] |

| Chemical modification of alginate | Pharmaceutical and Biomedical application | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGD peptide -modified sodium alginate | Carboxy coupling of carbodiimide and sodium alginate to introduce peptides as alginate side chains. | Used in scaffolds for prosthesis since it allows improve cell union, survival, and proliferation. | [99] |

| Hyaluronic acid - modified alginate hydrogel | Amine-hyaluronic acid (HA-NH2) was crosslinked with the aldehyde-alginate (Alg-CHO) through a covalent link. | Used as bioink in 3D-bioprinter for tissue engineering since it allows the development of cartilage tissue. | [100] |

| Oxidized alginate dialdehyde - gelatine hydrogel (ADA-GEL) | Alginate was oxidized using (meta)periodate as an oxidizing agent then was added to a gelatine solution for hydrogel formation. | Used as bioink in 3D-bioprinter for tissue engineering since it allows the development of cartilage tissue in scaffolds. | [101] |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid-modified alginate nanoparticles (GA-ALG NPs) | Alginate was modified by adding glycyrrhetinic acid, a metabolite of glycyrrhic acid (triterpenoid saponin glucoside) that has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. | GA-ALG NPs allowed the controlled release of the anticancer agent doxorubicin DOX, which is effective but toxic. NPs favored the effectiveness and specificity of the drug applied to a liver tumor. | [102] |

| Coumarin grafted blue-emitting fluorescent alginate derivative | Alginate was modified by aqueous conjugation through a coupling with carbodiimide and then an alkyne–azide “click” reaction. | The fluorescent modified alginate hydrogel allows in vitro and in vivo screening since it is biocompatible. | [103] |

| Azide-modified alginate crosslinked with tBCN depots | Alginate strands were modified using multi-arm cyclooctyne cross-linkers. The tetrabicyclononyne agents covalently cross-link azide-modified alginate hydrogels by “click” reaction. | These hydrogels are used in tissue engineering and drug administration through refillable depots since they are stable, haven high drug retention and maintain their structural integrity. | [104] |

| Nanocomposites coated with hydrophobically modified alginate | Alginate was modified with thiol and was grafted with amine-terminated poly butyl methacrylate (PBMA-NH2). | The magnetic plasmonic nanocomposites were coated with the modified alginate hydrogel to increase the encapsulation efficiency of cancer drugs (Paclitaxel), in photothermal cancer treatments and in tomography. | [105] |

| Crosslinked alginate microbeads | Alginate was modified with 2-aminoethyl methacrylate hydrochloride (AEMA) to add groups, when photoactivated, produce covalent bonds. | The modified alginate provides greater stability in cellular microbeads and can be used in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. | [106] |

| Dual cross-linked honey coupled alginate hydrogels | Sodium alginate had a double cross-linking (ionic and covalent) with CaCl2 and maleic anhydride and was embedded with honey. | The structurally modified sodium alginate coupled with honey hydrogel can be used in cutaneous wound healing due to its antimicrobial property. | [107] |

| Peptide-conjugated sodium alginate | Alginate was conjugated with peptides such as: arginine-glycine-aspartate (RGD) or tyrosine-isoleucine-glycine-serine-arginine (YIGSR). | Neuronal cells were bio-printed using an alginate-peptide composite as scaffold which improved their support and cellular regeneration. | [108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).