Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

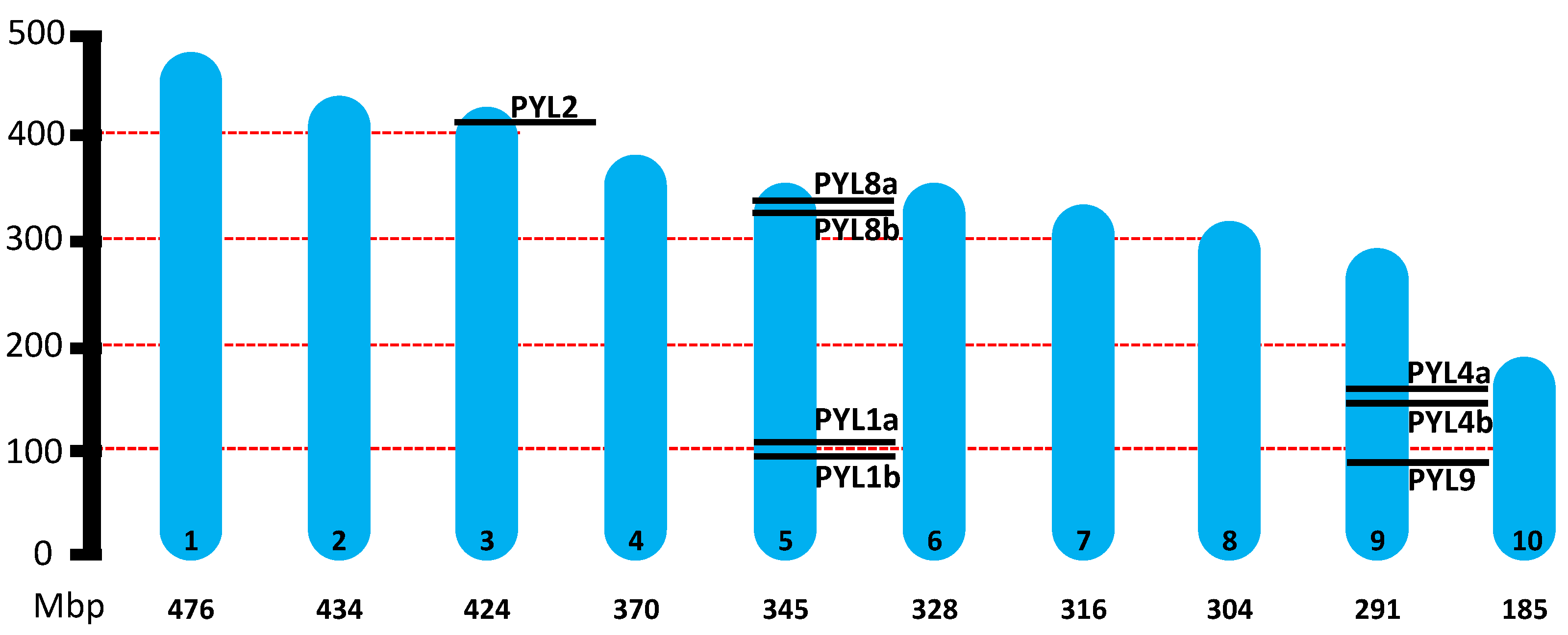

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of PYLs in H. lupulus

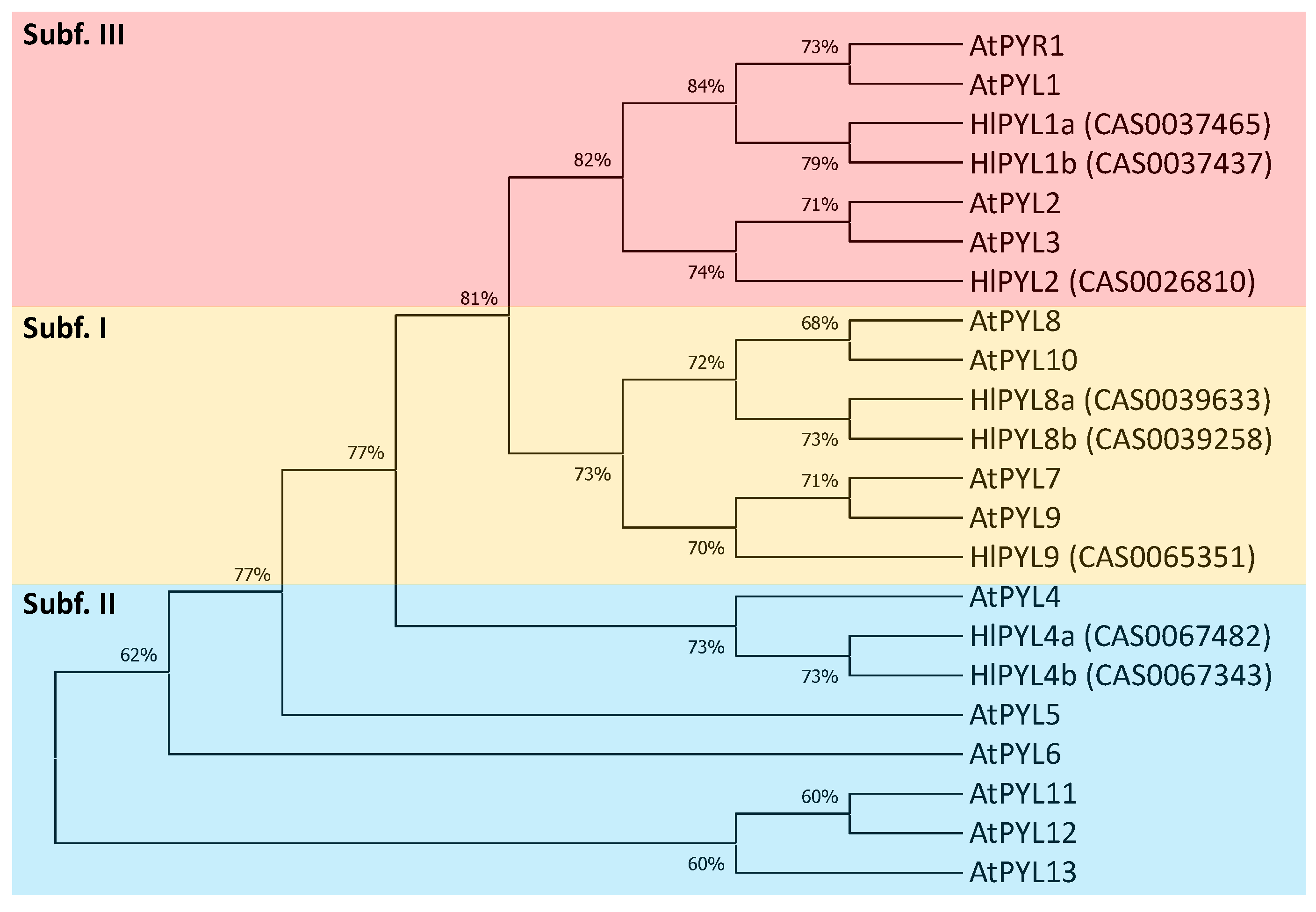

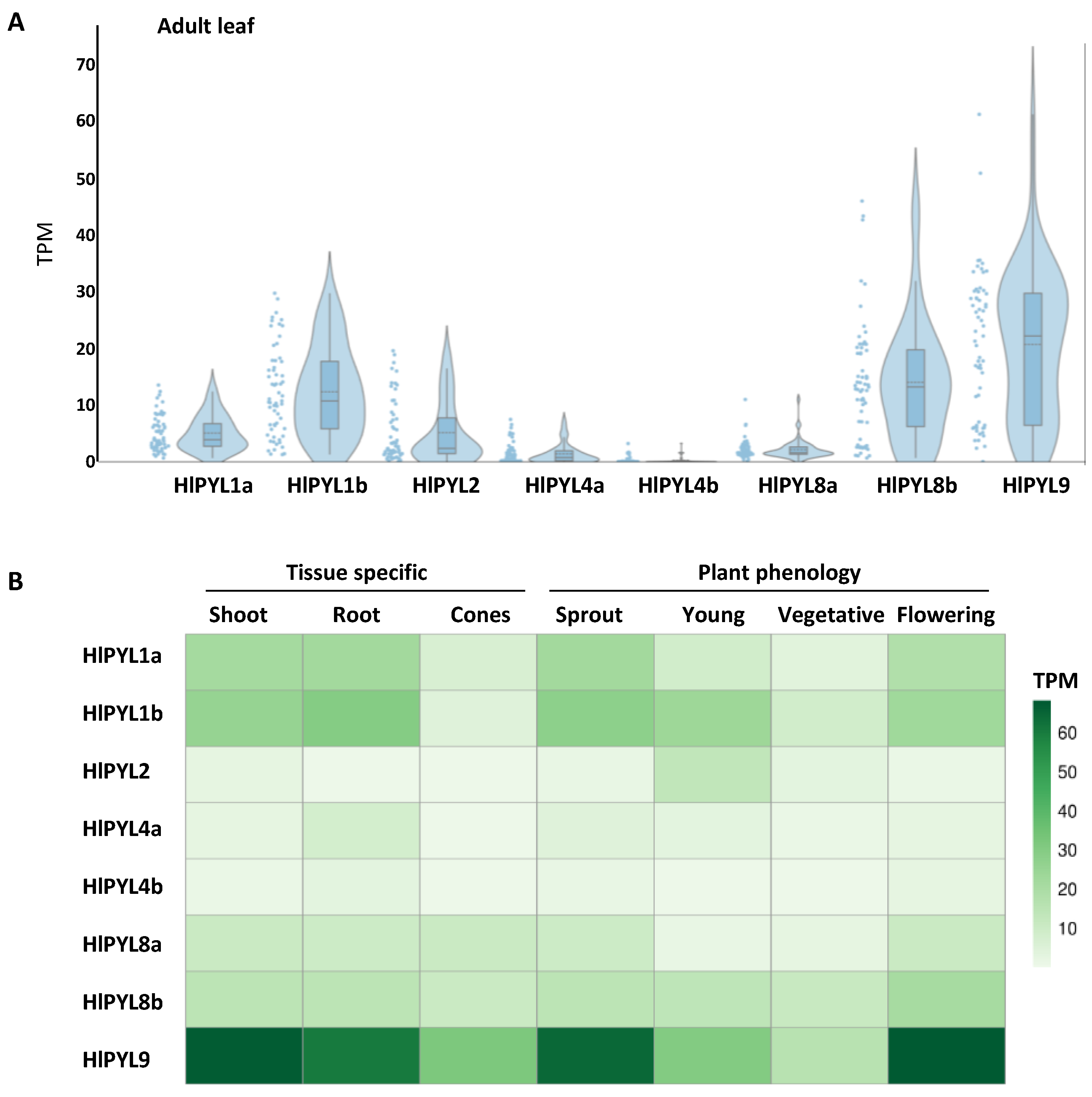

2.2. Phylogeny, Gene Structure Analysis and Tissue-Specific Expression Pattern of HlPYLs

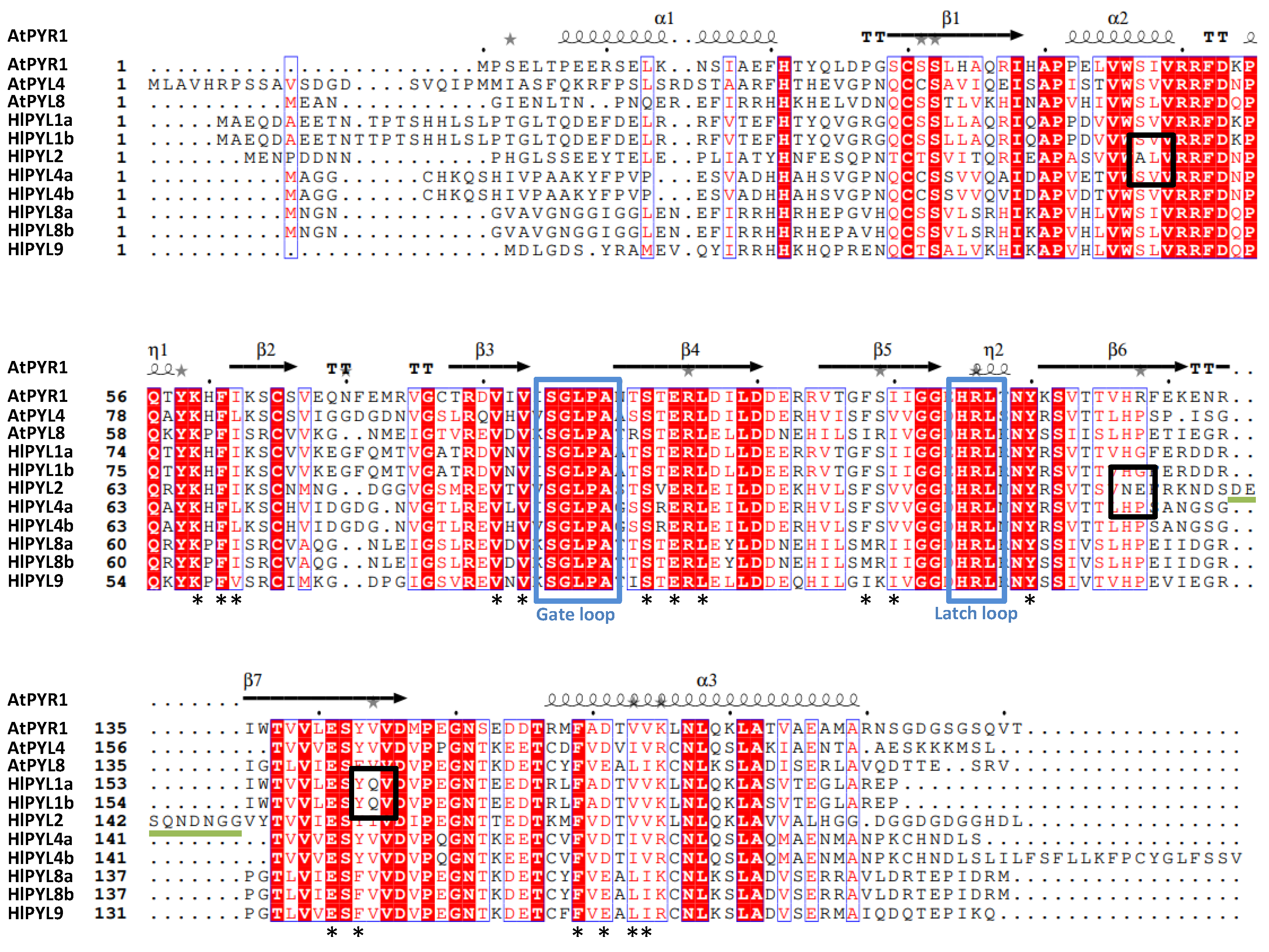

2.3. Conserved Motif, Protein Alignments and 3D Topology Analysis of PYLs in Hop

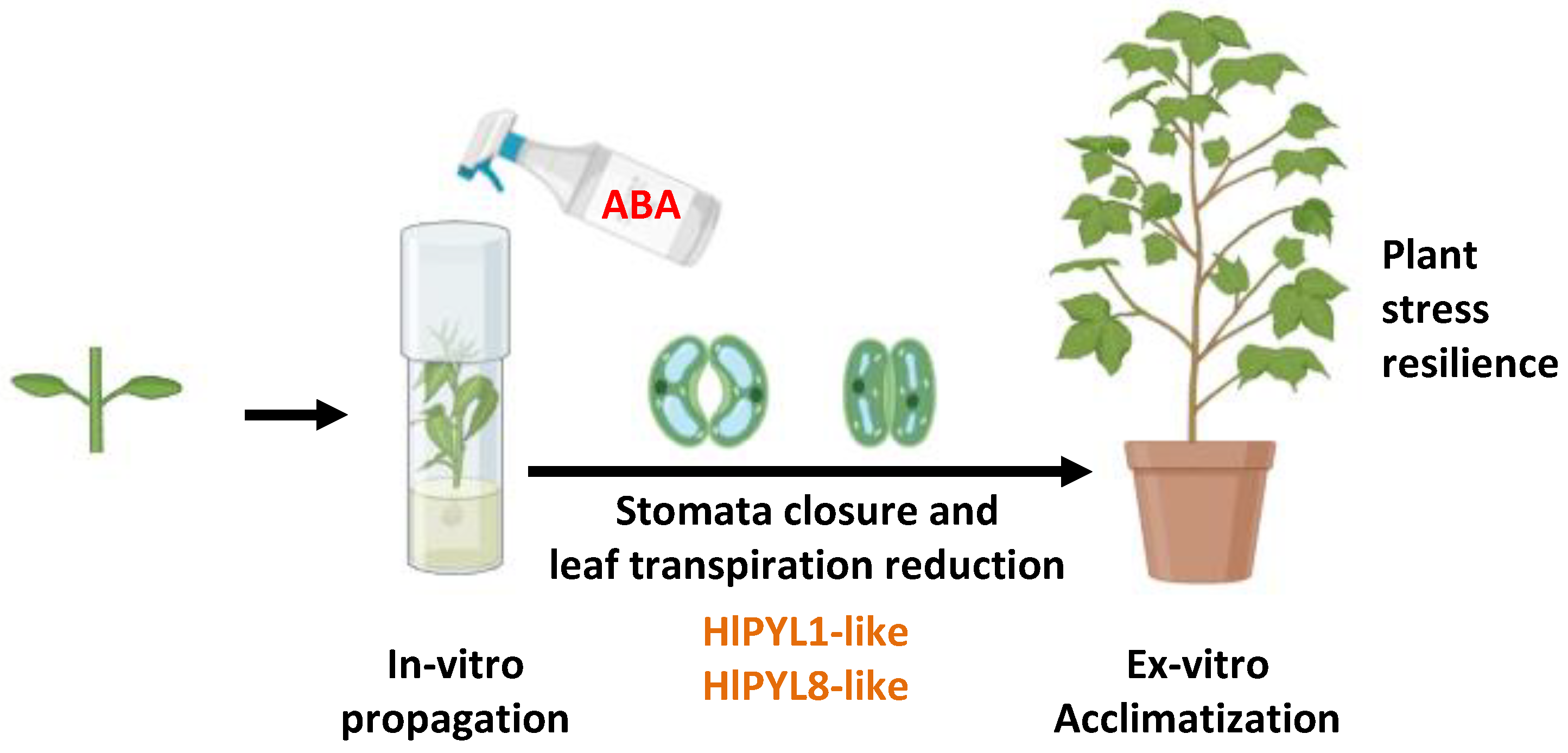

2.4. ABA Effects in Plant Ex-Vitro Acclimatization and Transpiration

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genome-Wide Identification of PYL Genes in Humulus lupulus L.

4.2. Phylogenetic and Gene Structure Analysis of HlPYLs

4.3. Analysis of ABA Receptor Expression in Hop Public Transcriptomic Data

4.4. Conserved Motifs Analysis, Protein Alignments and Homology Modeling of HlPYLs 3D Structure

4.5. Plant Material, ABA Treatment and Acclimatization to Ex-Vitro Conditions

4.6. Leaf Transpiration and Stomatal Aperture Assays

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zanoli, P.; Zavatti, M. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of Humulus lupulus L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 116, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uwe Koetter, M.B. Hops (Humulus lupulus): A review of its historic and medicinal uses. HerbalGram 2010, 87, 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli, D.; Brighenti, V.; Marchetti, L.; Reik, A.; Pellati, F. Nuclear magnetic resonance and high-performance liquid chromatography techniques for the characterization of bioactive compounds from Humulus lupulus L. (hop). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 3521–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neve, R. A. Hops. (Chapman and Hall, 1991).

- Roland, A.; Viel, C.; Reillon, F.; Delpech, S.; Boivin, P.; Schneider, R.; Dagan, L. First identifcation and quantifcation of glutathionylated and cysteinylated precursors of 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol and 4-methyl-4-mercaptopentan-2-one in hops (Humulus lupulus). Flavour Fragr. J. 2016, 31, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettberg, N.; Biendl, M.; Garbe, L. A. Hop aroma and hoppy beer favor: Chemical backgrounds and analytical tools—A review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2018, 76, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lafontaine, S.; Scott Varnum, S.; Roland, A.; Delpech, S.; Dagan, L.; Vollmer, D.; Kishimoto, T.; Shellhammer, T. Impact of harvest maturity on the aroma characteristics and chemistry of Cascade hops used for dry-hopping. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faragó, J.; Psenácová, I.; Faragová, N. The use of biotechnology in hop (Humulus lupulus L.) improvement. Nova Biotech. 2009, 9, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agehara, S.; Acosta-Rangel, A.; Gallardo, M.; Vallad, G. Selection and Preparation of Planting Material for Successful Hop Production in Florida: HS1381, 9/2020. EDIS: Gainesville, FL, 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sario L, Zubillaga MF, Moreno CFZ, Pizzio GA, Boeri PA. Micropropagation of Mapuche hop and evaluation of synthetic seed storage conditions. PCTOC. 2025, 160, 1–12.

- Pospíšilová, J.; Synková, H.; Haisel, D.; Baťková, P. Effect of abscisic acid on photosynthetic parameters during ex-vitro transfer of micropropagated tobacco plantlets. Biol. Plant. 2009, 53, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M. C.; Pinto, G.; Santos, C. Acclimatization of micropropagated plantlets induces an antioxidative burst: a case study with Ulmus minor Mill. Photosynthetica, 2011, 49, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osório, M. L.; Gonçalves, S.; Coelho, N.; Osório, J.; Romano, A. Morphological, physiological and oxidative stress markers during acclimatization and field transfer of micropropagated Tuberaria major plants. PCTOC. 2013, 115, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, M. L.; Espadas, F. L.; Coello, J.; Maust, B. E.; Trejo, C.; Robert, M. L.; Santamaria, J. M. The role of abscisic acid in con-trolling leaf water loss, survival and growth of micropropagated Tagetes erecta plants when transferred directly to the field. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 1861–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, J. M.; Davies, W. J.; Atkinson, C. J. Stomata of micropropagated Delphinium plants respond to ABA, CO2, light and water potential, but fail to close fully. J. Exp. Bot. 1993, 44, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, S.R.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Finkelstein, R.R.; Abrams, S.R. Abscisic Acid: Emergence of a Core Signaling Network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Praat, M.; Pizzio, G.A.; Jiang, Z.; Driever, S.M.; Wang, R.; Van De Cotte, B.; Villers, S.L.Y.; Gevaert, K.; Leonhardt, N.; Nelissen, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Vanneste, S.; Rodriguez, P.L.; van Zanten, M.; Vu, L.D.; De Smet, I. Stomatal opening under high X temperatures is controlled by the OST1-regulated TOT3–AHA1 module. Nature Plants 2025, 11, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srecec, S.; Kvaternjak, I.; Kaucic, D.; Mariæ, V. Dynamics of Hop Growth and Accumulation of α–acids in Normal and Extreme Climatic Conditions. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2004, 69, 59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mozny, M.; Tolasz, R.; Nekovar, J.; Sparks, T.; Trnka, M.; Zalud, Z. The impact of climate change on the yield and quality of Saaz hops in the Czech Republic. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2009, 149, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakawuka, P.; Peters, T. R.; Kenny, S.; Walsh, D. Efect of defcit irrigation on yield quantity and quality, water productivity and economic returns of four cultivars of hops in the Yakima Valley Washington State. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 98, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, P.; Pokorný, J.; Ježek, J.; Krofta, K.; Patzak, J.; Pulkrábek, J. Infuence of weather conditions, irrigation and plant age on yield and alpha-acids content of Czech hop (Humulus lupulus L.) cultivars. Plant, Soil Environ. 2020, 66, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahtane, H.; Kim, W.; Lopez-Molina, L. Primary seed dormancy: a temporally multilayered riddle waiting to be unlocked. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Liang, J.; Sui, J.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yi, M.; Gazzarrini, S.; Wu, J. ABA and Bud Dormancy in Perennials: Current Knowledge and Future Perspective. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Smet, I.; Signora, L.; Beeckman, T.; Inzé, D.; Foyer, C.H.; Zhang, H. An abscisic acid-sensitive checkpoint in lateral root development of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003, 33, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.F.; Chai, Y.M.; Li, C.L.; Lu, D.; Luo, J.J.; Qin, L.; Shen, Y.Y. Abscisic Acid Plays an Important Role in the Regulation of Strawberry Fruit Ripening. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Wani, S.H.; Razzaq, A.; Skalicky, M.; Samantara, K.; Gupta, S.; Pandita, D.; Goel, S.; Grewal, S.; Hejnak, V.; Shiv, A.; El-Sabrout, A.M.; Elansary, H.O.; Alaklabi, A.; Brestic, M. Abscisic Acid: Role in Fruit Development and Ripening. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 817–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, K.; Upadhyay, N.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, G.; Singh, J.; Mishra, R.K.; Kumar, V.; Verma, R.; Upadhyay, R.G.; Pandey, M.; et al. Abscisic Acid Signaling and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants: A Review on Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombesi, S.; Nardini, A.; Frioni, T.; Soccolini, M.; Zadra, C.; Farinelli, D.; Poni, S.; Palliotti, A. Stomatal closure is induced by hydraulic signals and maintained by ABA in drought-stressed grapevine. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falchi, R.; Petrussa, E.; Braidot, E.; Sivilotti, P.; Boscutti, F.; Vuerich, M.; Calligaro, C.; Filippi, A.; Herrera, J.C.; Sabbatini, P. Analysis of Non-Structural Carbohydrates and Xylem Anatomy of Leaf Petioles Offers New Insights in the Drought Response of Two Grapevine Cultivars. IJMS 2020, 21, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.; Alshehadah, E.; Slaman, H. Abscisic Acid (ABA) and Salicylic Acid (SA) Content in Relation to Transcriptional Patterns in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) under Salt Stress. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 8, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Lamers, J.; Zhang, Y.; van Zelm, E.; Leong, C.K.; Meyer, A.J.; de Zeeuw, T.; Verstappen, F.; Veen, M.; Deolu-Ajayi, A.O.; Gommers, C.M.M.; Testerink, C. Abscisic acid signaling gates salt-induced responses of plant roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025, 122, e2406373122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, R.; Berli, F.J.; Bottini, R.; Piccoli, P. Acclimation mechanisms elicited by sprayed abscisic acid, solar UV-B and water deficit in leaf tissues of field-grown grapevines. Plant Physiol. and Biochem. 2015, 91, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murcia, G.; Fontana, A.; Pontin, M.; Baraldi, R.; Bertazza, G.; Piccoli, P.N. ABA and GA3 regulate the synthesis of primary and secondary metabolites related to alleviation from biotic and abiotic stresses in grapevine. Phytochem. 2017, 135, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzio, G.A.; Mayordomo, C.; Illescas-Miranda, J.; Coego, A.; Bono, M.; Sanchez-Olvera, M.; Martin-Vasquez, C.; Samantara, K.; Merilo, E.; Forment, J.; Estevez, J.C.; Nebauer, S.G.; Rodriguez, P.L. Basal ABA signaling balances transpiration and photosynthesis. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, G.; Abraham, E.; Cseplo, A.; Rigó, G.; Zsigmond, L.; Csiszár, J.; Ayaydin, F.; Strizhov, N.; Jásik, J.; Schmelzer, E.; Koncz, C.; Szabados, L. Duplicated P5CS genes of Arabidopsis play distinct roles in stress regulation and developmental control of proline biosynthesis. Plant J. 2008, 53, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Basak, P.; Majumder, A.L. Significance of galactinol and raffinose family oligosaccharide synthesis in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, F.; Klahn, S.; Hagemann, M. Salt-Regulated Accumulation of the Compatible Solutes Sucrose and Glucosylglycerol in Cyanobacteria and Its Biotechnological Potential. Front Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambara, E.; Marion-Poll, A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Davies,W.J. Increased Synthesis of ABA in Partially Dehydrated Root Tips and ABA Transport from Roots to Leaves. J. Exp. Bot. 1987, 38, 2015–2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Davies, W.J. Changes in the concentration of ABA in xylem sap as a function of changing soil water status can account for changes in leaf conductance and growth. Plant Cell Environ. 1990, 13, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzi, M.; Lado, J.; Rodrigo, M.J.; Zacarías, L.; Arbona, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Root ABA Accumulation in Long-Term Water-Stressed Plants is Sustained by Hormone Transport from Aerial Organs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 2457–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdam, S.A.M.; Brodribb, T.J. Mesophyll Cells Are the Main Site of Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis in Water-Stressed Leaves. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Partida, R.; Rosario, S.; Lozano-Juste, J. An Update on Crop ABA Receptors. Plants 2021, 10, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Fung, P.; Nishimura, N.; et. al. Abscisic acid inhibits type 2C protein phosphatases via the PYR/PYL family of START proteins. Science 2009, 324, 1068–1071. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Szostkiewicz, I.; Korte, A.; Moes, D.; Yang, Y.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 2009, 324, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Saez, A.; Rubio, S.; Antoni, R.; Dupeux, F.; Park, SY.; Márquez, JA.; Cutler, SR.; Rodriguez, PL. ; Modulation of drought resistance by the abscisic acid receptor PYL5 through inhibition of clade A PP2Cs. The Plant Journal 2009, 60, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, T.; Sugiyama, N.; Mizoguchi, M.; Hayashi, S.; Myouga, F.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Ishihama, Y.; Hirayama, T.; Shinozaki, K. Type 2C protein phosphatases directly regulate abscisic acid-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17588–17593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, F.; Rubio, S.; Rodrigues, A.; Sirichandra, C.; Belin, C.; Robert, N.; Leung, J.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Laurière, C.; Merlot, S. Protein Phosphatases 2C Regulate the Activation of the Snf1-Related Kinase OST1 by Abscisic Acid in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3170–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coego, A.; Julian, J.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Pizzio, G.A.; Alrefaei, A.; Rodriguez, P. Ubiquitylation of ABA Receptors and Protein Phosphatase 2C Coreceptors to Modulate ABA Signaling and Stress Response. IJMS 2021, 22, 7103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A. Abscisic Acid Machinery Is under Circadian Clock Regulation at Multiple Levels. Stresses 2022, 2, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A.; Rodriguez, P.L. Dual regulation of SnRK2 signaling by Raf-like MAPKKKs. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1260–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A. Genome-Wide Identification of the PYL Gene Family in Chenopodium quinoa: From Genes to Protein 3D Structure Analysis. Stresses 2022, 2, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A. Abscisic Acid Perception and Signaling in Chenopodium quinoa. Stresses 2023, 3, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, Y.P.; Chen, P.; Ren, J.; Ji, K.; Li, Q.; Li, P.; Dai, S.J.; Leng, P. Transcriptional regulation of SlPYL, SlPP2C, and SlSnRK2 gene families encoding ABA signal core components during tomato fruit development and drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 15, 5659–5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, U.; Biton, I.; Zheng, C.; Schwartz, A.; Ben-Ari, G. Characterization of potential ABA receptors in Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bono, M.; Ferrer-Gallego, R.; Pou, A.; Rivera-Moreno, M.; Benavente, J.L.; Mayordomo, C.; Deis, L.; Carbonell-Bejerano, P.; Pizzio, G.A.; Navarro-Payá, D.; Matus, J.T.; Martinez-Zapater, J.M.; Albert, A.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Rodriguez, P.L. Chemical activation of ABA signaling in grapevine through the iSB09 and AMF4 ABA receptor agonists enhances water use efficiency. Physiol Plant. 2024, 176, e14635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Wei, X.; Gao, R.; Huo, F.; Nie, X.; Tong, W.; Song, W. Genome-wide identification of PYL gene family in wheat: Evolution, expression and 3D structure analysis. Genomics 2021, 113, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hao, Q.; Li, W.Q.; Yan, C.Y.; Yan, N.E.; Yin, P. Identification and characterization of ABA receptors in Oryza sativa. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, F.F.; Jian, H.J.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, X.P.; Ding, Y.R.; Du, H.; Lu, K.; Li, J.N.; Liu, L.Z. Genome-wide analysis of the PYL gene family and identification of PYL genes that respond to abiotic stress in Brassica napus. Genes 2018, 9, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Maquilon, I.; Coego, A.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Messerer, M.; de Ollas, C.; Julian, J.; Ruiz-Partida, R.; Pizzio, G.; Belda-Palazón, B.; Gomez-Cadenas, A.; et al. PYL8 ABA receptors of Phoenix dactylifera play a crucial role in response to abiotic stress and are stabilized by ABA. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 757–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzio, G.A.; Mayordomo, C.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Garcia-Carpintero, V.; Vazquez-Vilar, M.; Nebauer, S.G.; Kaminski, K.P.; Ivanov, N.V.; Estevez, J.C.; Rivera-Moreno, M.; et al. PYL1- and PYL8-like ABA Receptors of Nicotiana benthamiana Play a Key Role in ABA Response in Seed and Vegetative Tissue. Cells 2022, 11, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, ST.; Sudarsanam, R.; Henning, J.; Hendrix, D. HopBase: a unified resource for Humulus genomics. Database 2017, bax009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgitt-Cobb, L.K.; Kingan, S.B.; Wells, J.; Elser, J.; Kronmiller, B.; Moore, D.; Concepcion, G.; Peluso, P.; Rank, D.; Jaiswal, P.; Henning, J.; Hendrix, D.A. A draft phased assembly of the diploid Cascade hop (Humulus lupulus) genome. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Lorenzo-Orts, L.; Pons, C.; Sarrion-Perdigones, A.; Fernandez, M.A.; Peirats-Llobet, M.; Forment, J.; Moreno-Alvero, M.; Cutler, S.R.; et al. Tomato PYR/PYL/RCAR abscisic acid receptors show high expression in root, differential sensitivity to the abscisic acid agonist quinabactin, and the capability to enhance plant drought resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4451–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Betrán, E.; Thornton, K.;Wang,W. The origin of new genes: Glimpses from the young and old. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 11, 865–875.

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Alvero, M.; Yunta, C.; Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Benavente, J.L.; Arbona, V.; Menéndez, M.; MartinezRipoll, M.; Infantes, L.; Gomez-Cadenas, A.; et al. Structure of Ligand-Bound Intermediates of Crop ABA Receptors Highlights PP2C as Necessary ABA Co-receptor. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1250–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sario, L.; Boeri, P.; Matus, J.T.; Pizzio, G.A. Plant Biostimulants to Enhance Abiotic Stress Resilience in Crops. IJMS, 2025, 26, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A. Potential Implications of the Phytohormone Abscisic Acid in Human Health Improvement at the Central Nervous. System. Ann. Epidemiol. Public Health 2022, 5, 1090. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, C. , Xiao, L., Hua, K., Zou, C., Zhao, Y., Bressan, R.A. et al. Mutations in a subfamily of abscisic acid receptor genes promote rice growth and productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 6058–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquna, A.; Peterson, F.C.; Park, S.Y.; Lozano-Juste, J.; Volkman, B.F.; Cutler, S.R. Potent and selective activation of abscisic acid receptors in vivo by mutational stabilization of their agonist-bound conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20838–20843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Duan, C.; Chen, P.; Li, Q.; Dai, S.; Sun, L.; Ji, K.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; et al. The expression profiling of the CsPYL, CsPP2C and CsSnRK2 gene families during fruit development and drought stress in cucumber. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1874–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzio, G.A.; Rodriguez, L.; Antoni, R.; Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Yunta, C.; Merilo, E.; Kollist, H.; Albert, A.; Rodriguez, P.L. The PYL4 A194T mutant uncovers a key role of PYR1-LIKE4/PROTEIN PHOSPHATASE 2CA interaction for abscisic acid signaling and plant drought resistance. Plant Physiol. 2013, 163, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Poree, F.; Schaeufele, R.; Helmke, H.; Frackenpohl, J.; Lehr, S.; von Koskull-Döring, P.; Christmann, A.; Schnyder, H.; et al. Abscisic Acid Receptors and Coreceptors Modulate Plant Water Use Efficiency and Water Productivity. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbona, V.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Manzi, M.; González-Guzmán, M.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Gómez-Cadenas, A. Depletion of Abscisic Acid Levels in Roots of Flooded Carrizo Citrange (Poncirus Trifoliata L. Raf. × Citrus Sinensis L. Osb.) Plants Is a Stress-Specific Response Associated to the Differential Expression of PYR/PYL/RCAR Receptors. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 93, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M. C.; Correia, C.; Moutinho-Pereira, J.; Oliveira, H.; Santos, C. Study of the effects of foliar application of ABA during acclimatization. PCTOC 2014, 117, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.; Orduña, L.; Fernández, JD.; Vidal, Á.; de Martín-Agirre, I.; Lisón, P.; Vidal, EA.; Navarro-Payá, D.; Matus, JT. The Plantae Visualization Platform: A comprehensive web-based tool for the integration, visualization, and analysis of omic data across plant and related species. bioRxiv Bioinformatics. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. Clustvis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motif Search. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/tools/motif/ (accessed on October 1st 2023).

- Benkert, P.; Biasini, M.; Schwede, T. Toward the estimation of the absolute quality of individual protein structure models. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studer, G.; Rempfer, C.; Waterhouse, A.M.; Gumienny, G.; Haas, J.; Schwede, T. QMEANDisCo—Distance constraints applied on model quality estimation. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1765–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Pizzio, G.A.; Antoni, R.; Vera-Sirera, F.; Merilo, E.; Bassel, G.W.; et al. Arabidopsis PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors play a major role in quantitative regulation of stomatal aperture and transcriptional response to abscisic acid. The Plant Cell. 2012, 24, 2483–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Gene name | Genome location (start..stop) | ORF length (bp) | Protein size (aa) |

| HUMLU_CAS0037465 | HlPYL1a | CH5/Scaffold 24 (101098846..101099927) | 600 | 200 |

| HUMLU_CAS0037437 | HlPYL1b | CH5/Scaffold 24 (97872371..97873468) | 603 | 201 |

| HUMLU_CAS0026810 | HlPYL2 | CH3/Scaffold 1533 (420945668..420946409) | 615 | 204 |

| HUMLU_CAS0067482 | HlPYL4a | CH9/Scaffold 49 (153780561..153781466) | 579 | 192 |

| HUMLU_CAS0067343 | HlPYL4b | CH9/Scaffold 49 (147637069..147638078) | 633 | 211 |

| HUMLU_CAS0039633 | HlPYL8a | CH5/Scaffold 24 (335968664..335971620) | 579 | 192 |

| HUMLU_CAS0039258 | HlPYL8b | CH5/Scaffold 24 (323689689..323692723) | 579 | 192 |

| HUMLU_CAS0065351 | HlPYL9 | CH9/Scaffold 49 (93847944..93850402) | 558 | 185 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).