Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Herbicides, Solvents and Reagents

2.2. Soil and Organic Amendments (Agro-Industrial Wastes) Used

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. Analytical Determinations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Adsorption of Herbicides in Amended and Unamended Soils

3.2. Dissipation and Persistence of Herbicides in Amended and Unamended Soils

| Herbicide | Soil | Parameter | |||||

| R2 | C0 | K (d-1) | Sy/x | DT50 (d) | DT90 (d) | ||

| Metobromuron | S | 0.974*** | 0.96 | 0.0124 | 0.04 | 56 | 186 |

| S + OP | 0.962** | 1.07 | 0.0475 | 0.10 | 15 | 48 | |

| S + SG | 0.989*** | 1.03 | 0.0650 | 0.05 | 11 | 35 | |

| S + GW | 0.995*** | 1.00 | 0.0448 | 0.03 | 15 | 51 | |

| S +GP | 0.951** | 1.07 | 0.0425 | 0.11 | 16 | 54 | |

| Chlorbromuron | S | 0.979*** | 0.97 | 0.0073 | 0.02 | 95 | 315 |

| S + OP | 0.966*** | 1.03 | 0.0097 | 0.04 | 71 | 237 | |

| S + SG | 0.972*** | 0.95 | 0.0390 | 0.06 | 18 | 59 | |

| S + GW | 0.959*** | 1.05 | 0.0130 | 0.05 | 53 | 177 | |

| S +GP | 0.978*** | 0.99 | 0.0208 | 0.05 | 33 | 111 | |

3.3. Leaching of Herbicides Through the Soil Columns

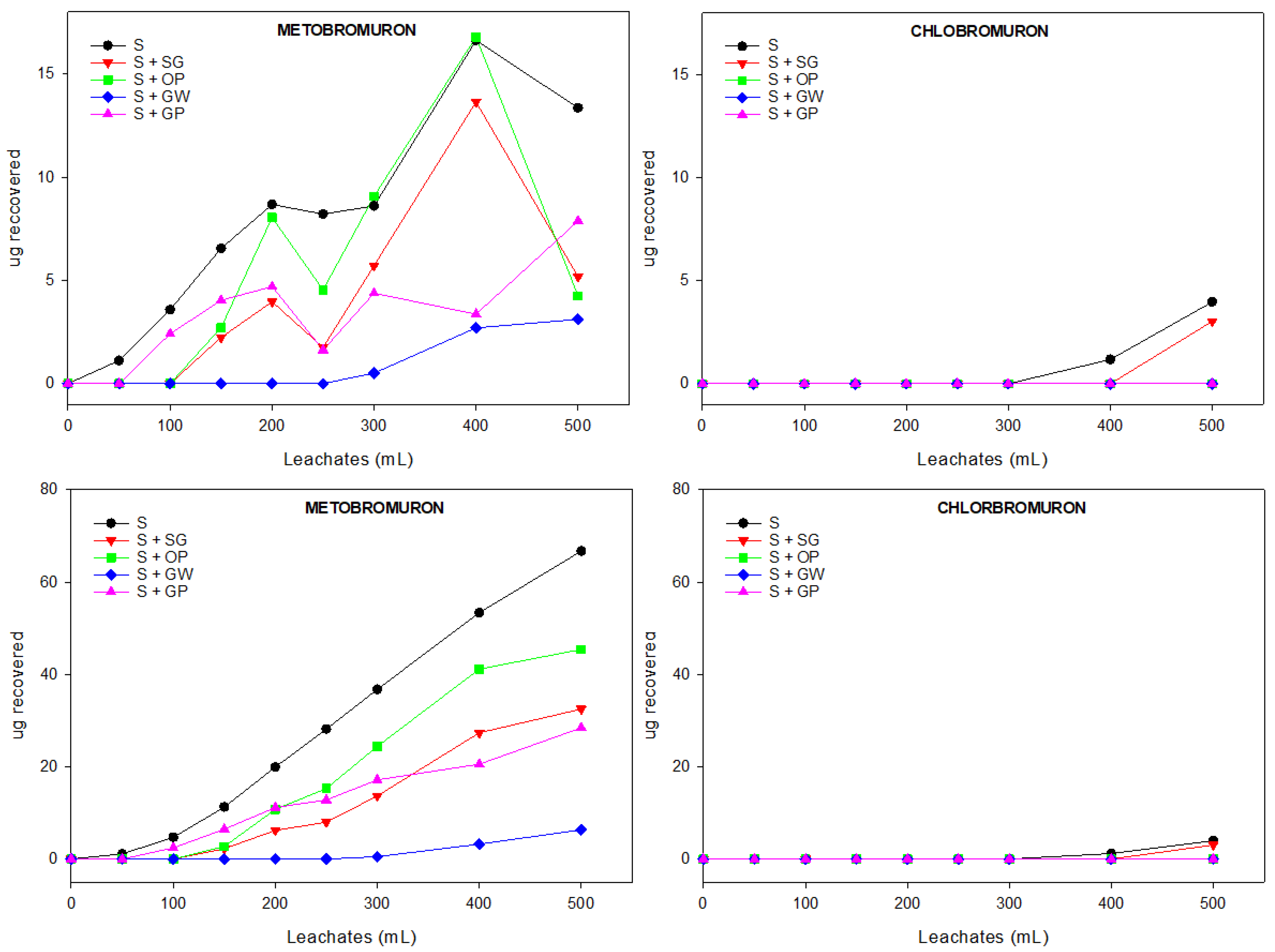

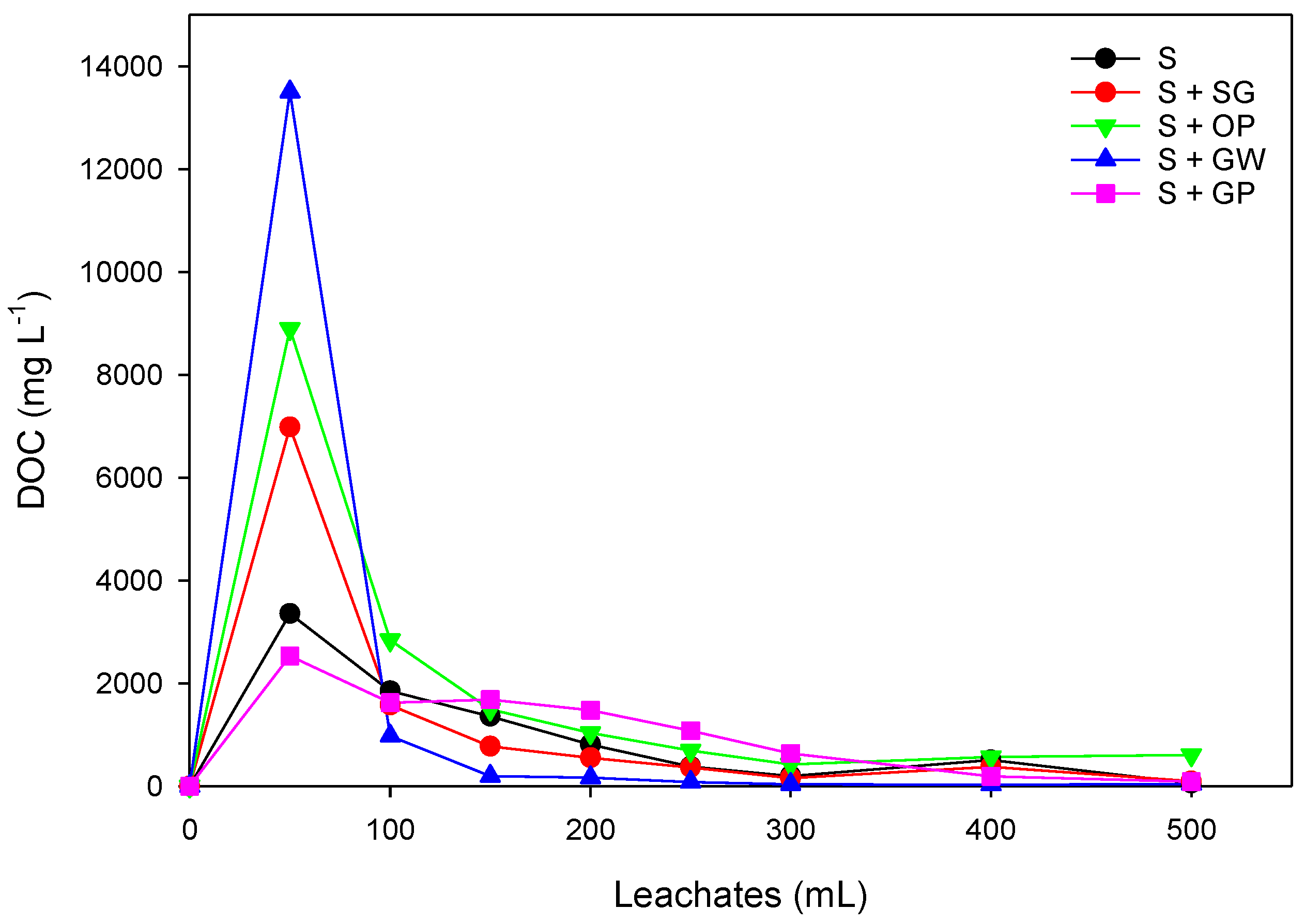

3.3.1. Relative and Cumulative Breakthrough Curves (BTCs) of Herbicides

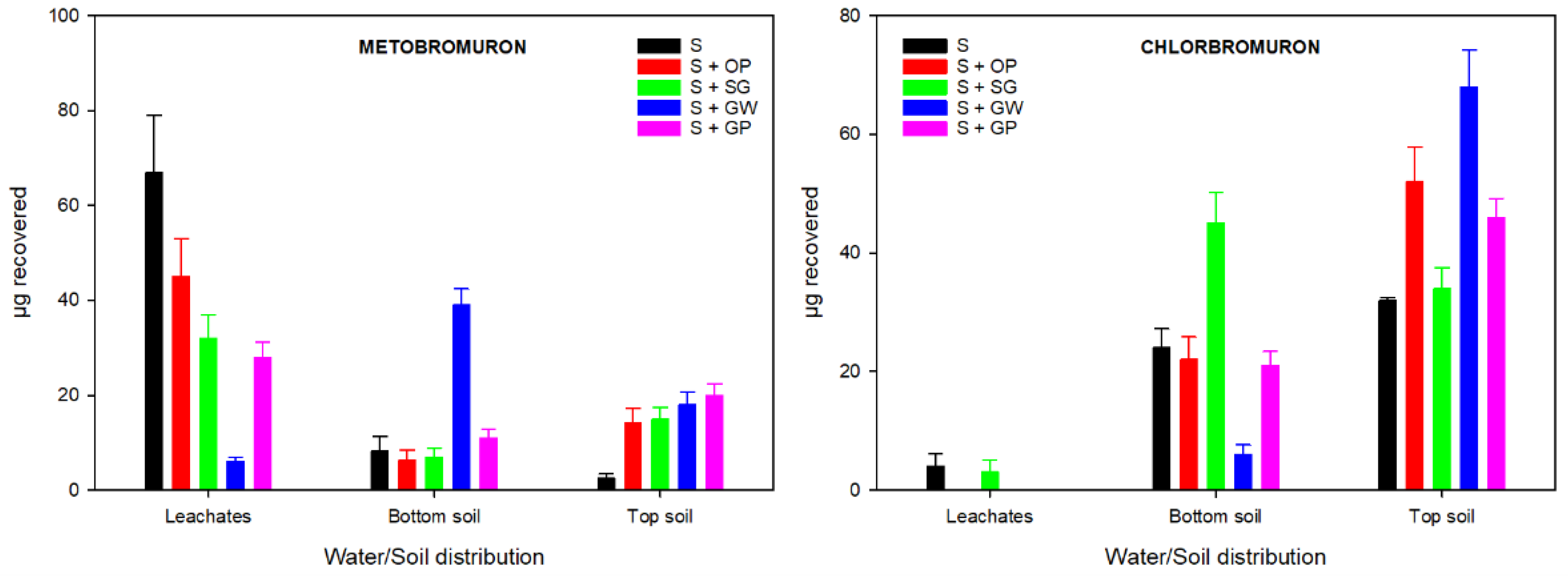

3.3.2. Distribution of Herbicides from Soil and Leachates

3.3.3. Leaching Index Screening

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTCs | Breakthrough curves |

| CB | Chlorbromuron |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| DT | Disappearance time |

| EC | European Comission |

| FOCUS | (FOrum for the Co-ordination of pesticide fate models and their Use) |

| GP | Grape pomace |

| GW | Gazpacho wastes |

| MB | Metobromuron |

| OC | Organic carbon |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| OM | Organic matter |

| OP | Orange peel |

| SFO | Single First Order |

| SG | Spent grains |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| US EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Hertog, S.; Gerland, P.; Wilmoth, J. India Overtakes China as the World’s Most Populous Country. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oerke, E.-C. Crop Losses to Pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junaid, M.; Gokce, A. Global Agricultural Losses and Their Causes. Bull. Biol. Allied Sci. Res. 2024, 2024, 66–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Navarro, G.; Navarro, S. Adapting Agriculture and Pesticide Use in Mediterranean Regions under Climate Change Scenarios: A Comprehensive Review. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 161, 127337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. 2025. Pesticides Use. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Vela, N.; El Aatik, A.; Navarro, S. Environmental Risk of Groundwater Pollution by Pesticide Leaching through the Soil Profile. In Pesticides-use and misuse and their impact in the environment; IntechOpen, 2019 ISBN 1-83880-047-6.

- Navarro, S.; Vela, N.; Navarro, G. An Overview on the Environmental Behaviour of Pesticide Residues in Soils. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2007, 5, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farenhorst, A. Importance of Soil Organic Matter Fractions in Soil-landscape and Regional Assessments of Pesticide Sorption and Leaching in Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauchope, R.D.; Yeh, S.; Linders, J.B.H.J.; Kloskowski, R.; Tanaka, K.; Rubin, B.; Katayama, A.; Kördel, W.; Gerstl, Z.; Lane, M. Pesticide Soil Sorption Parameters: Theory, Measurement, Uses, Limitations and Reliability. Pest Manag. Sci. 2002, 58, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, K.; Sun, C.; Yang, K.; Zheng, J. Differences in Soil Physical Properties Caused by Applying Three Organic Amendments to Loamy Clay Soil under Field Conditions. J. Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbu, C.C.; Okey, S.N. Agro-Industrial Waste Management: The Circular and Bioeconomic Perspective. Agric. Waste-New Insights 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Briceño, G.; Palma, G.; Durán, N. Influence of Organic Amendment on the Biodegradation and Movement of Pesticides. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 37, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, J.; Ruiz, E.; Flores, P.; Hellin, P.; Navarro, S. Leaching Potential of Several Insecticides and Fungicides through Disturbed Clay-Loam Soil Columns. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2010, 90, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, J.; Ruiz, E.; Flores, P.; Hellín, P.; Navarro, S. Reduction of the Movement and Persistence of Pesticides in Soil through Common Agronomic Practices. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoll, J.; Ruiz, E.; Flores, P.; Vela, N.; Hellín, P.; Navarro, S. Use of Farming and Agro-Industrial Wastes as Versatile Barriers in Reducing Pesticide Leaching through Soil Columns. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoll, J.; Garrido, I.; Hellín, P.; Flores, P.; Vela, N.; Navarro, S. Use of Different Organic Wastes in Reducing the Potential Leaching of Propanil, Isoxaben, Cadusafos and Pencycuron through the Soil. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2014, 49, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenoll, J.; Vela, N.; Navarro, G.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Navarro, S. Assessment of Agro-Industrial and Composted Organic Wastes for Reducing the Potential Leaching of Triazine Herbicide Residues through the Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, I.; Vela, N.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, G.; Pérez-Lucas, G.; Navarro, S. Testing of Leachability and Persistence of Sixteen Pesticides in Three Agricultural Soils of a Semiarid Mediterranean Region. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 13, e1104–e1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Benito, J.; Brown, C.D.; Herrero-Hernández, E.; Arienzo, M.; Sánchez-Martín, M.-J.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M. Use of Raw or Incubated Organic Wastes as Amendments in Reducing Pesticide Leaching through Soil Columns. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Hernandez-Bastida, J.; Cazana, G.; Perez-Lucas, G.; Fenoll, J. Assessment of the Leaching Potential of 12 Substituted Phenylurea Herbicides in Two Agricultural Soils under Laboratory Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5279–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Vela, N.; Escudero, J.A.; Navarro, G.; Navarro, S. Valorization of Organic Wastes to Reduce the Movement of Priority Substances through a Semiarid Soil. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Gambín, M.; Navarro, S. Leaching Behaviour Appraisal of Eight Persistent Herbicides on a Loam Soil Amended with Different Composted Organic Wastes Using Screening Indices. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 273, 111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; Vela, N.; Abellán, M.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, S. Use of Index-Based Screening Models to Evaluate the Leaching of Triclopyr and Fluroxypyr through a Loam Soil Amended with Vermicompost. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 104, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lucas, G.; El Aatik, A.; Vela, N.; Fenoll, J.; Navarro, S. Exogenous Organic Matter as Strategy to Reduce Pesticide Leaching through the Soil. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2021, 67, 934–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.K.; Ghanizadeh, H.; Harrington, K.C.; Bolan, N.S. The Leaching Behaviour of Herbicides in Cropping Soils Amended with Forestry Biowastes. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 307, 119466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, B.A.; Xia, K.; Stewart, R.D. Soil Organic Matter Can Delay—but Not Eliminate—Leaching of Neonicotinoid Insecticides; Wiley Online Library, 2022.

- Yavari, S.; Asadpour, R.; Kamyab, H.; Yavari, S.; Kutty, S.R.M.; Baloo, L.; Manan, T.S.B.A.; Chelliapan, S.; Sidik, A.B.C. Efficiency of Carbon Sorbents in Mitigating Polar Herbicides Leaching from Tropical Soil. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2022, 24, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Hernández, E.; Andrades, M.S.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Marín-Benito, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S. Effect of Applying an Organic Amendment on the Persistence of Tebuconazole and Fluopyram in Vineyard Soils. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granetto, M.; Bianco, C.; Tosco, T. The Role of Soil Amendments in Limiting the Leaching of Agrochemicals: Laboratory Assessment for Copper Sulphate and Dicamba. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 474, 143532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, S.; Bhullar, M.S. Modulating Leaching of Mesosulfuron Methyl, Iodosulfuron Methyl and Transformation Products: Effects of Rainfall Intensity, Flow Patterns and Organic Amendments. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 114, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, O.; Temur, C. The Fate of Pesticide in the Environment. J. Biol. Environ. Sci. 2010, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, P.C.; Ojha, A.; Debnath, S.; Sharma, M.; Sridhar, K.; Nayak, P.K.; Inbaraj, B.S. Biogeneration of Valuable Nanomaterials from Agro-Wastes: A Comprehensive Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals: Sustainable Development; 2015.

- Kour, R.; Singh, S.; Sharma, H.B.; Naik, T.S.K.; Shehata, N.; Ali, W.; Kapoor, D.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Singh, J.; Khan, A.H. Persistence and Remote Sensing of Agri-Food Wastes in the Environment: Current State and Perspectives. Chemosphere 2023, 317, 137822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Das, R.; Sangwan, S.; Rohatgi, B.; Khanam, R.; Peera, S.P.G.; Das, S.; Lyngdoh, Y.A.; Langyan, S.; Shukla, A. Utilisation of Agro-Industrial Waste for Sustainable Green Production: A Review. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Benito, J.M.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S. Impact of Spent Mushroom Substrates on the Fate of Pesticides in Soil, and Their Use for Preventing and/or Controlling Soil and Water Contamination: A Review. Toxics 2016, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagi, T. Soil Column Leaching of Pesticides. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. Vol. 221 2013, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Kolupaeva, V.; Belik, A.; Kokoreva, A.; Astaikina, A. Risk Assessment of Pesticide Leaching into Groundwater Based on the Results of a Lysimetric Experiment.; IOP Publishing, 2019; Vol. 368, p. 012023.

- OECD. Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals, Test No. 312. Leaching in Soil Columns. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; Paris, 2004.

- US EPA. Fate, Transport and Transformation Test Guidelines: OPPTS 835.1240 Leaching Studies [EPA 712-C-08-010]. Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency; 2008.

- Araya, G.; Perfetti-Bolaño, A.; Sandoval, M.; Araneda, A.; Barra, R.O. Groundwater Leaching Potential of Pesticides: A Historic Review and Critical Analysis: Groundwater Leaching of Pesticides. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2024, 43, 2478–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, A.E.A.; Dilek, F.B.; Yetis, U. A New Screening Index for Pesticides Leachability to Groundwater. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 231, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. Estimation Programs Interface Suite for Microsoft Windows, v 4.10. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington DC; 2012.

- Lewis, K.A.; Tzilivakis, J.; Warner, D.J.; Green, A. An International Database for Pesticide Risk Assessments and Management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016, 22, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps. 4th Edition. International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS),; Vienna, Austria, 2022.

- OECD. Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals, Test No 106. Adsorption - Desorption Using a Batch Equilibrium Method. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; Paris, 2000.

- OECD. Guidelines for Testing of Chemicals, Test No 307, Aerobic and Anaerobic Transformation in Soil. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; Paris, 2002.

- Boesten, J.; Aden, K.; Beigel, C.; Beulke, S.; Dust, M.; Dyson, J.; Fomsgaard, I.; Jones, R.; Karlsson, S.; Van der Linden, A. Guidance Document on Estimating Persistence and Degradation Kinetics from Environmental Fate Studies on Pesticides in EU Registration. Rep. FOCUS Work Group Degrad. Kinet. EC Doc Ref Sanco100582005 Version 2006, 1, 68–106. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, A.; Langeron, J.; Sayen, S.; Hénon, E.; Couderchet, M.; Guillon, E. Molecular Properties Affecting the Adsorption Coefficient of Phenylurea Herbicides. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 6266–6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, F.; Fernandez-Perez, M.; Johnson, A.; Flores-Cesperedes, F.; Gonzalez-Pradas, E. Limitations on the Role of Incorporated Organic Matter in Reducing Pesticide Leaching. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2001, 49, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilescu, M. Fate of Pesticides in the Environment and Its Bioremediation. Eng. Life Sci. 2005, 5, 497–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Goltz, M.; Close, M. Application of the Method of Temporal Moments to Interpret Solute Transport with Sorption and Degradation. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2003, 60, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoll, J.; Garrido, I.; Hellín, P.; Flores, P.; Vela, N.; Navarro, S. Use of Different Organic Wastes as Strategy to Mitigate the Leaching Potential of Phenylurea Herbicides through the Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 4336–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantigny, M.H. Dissolved and Water-Extractable Organic Matter in Soils: A Review on the Influence of Land Use and Management Practices. Geoderma 2003, 113, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.; Velarde, P.; Cabrera, A.; Hermosín, M.; Cornejo, J. Dissolved Organic Carbon Interactions with Sorption and Leaching of Diuron in Organic-amended Soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsbo, M.; Löfstrand, E.; de Veer, D. van A.; Ulén, B. Pesticide Leaching from Two Swedish Topsoils of Contrasting Texture Amended with Biochar. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2013, 147, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Benito, J.M.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J.; Ordax, J.M.; Draoui, K.; Azejjel, H.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S. Organic Sorbents as Barriers to Decrease the Mobility of Herbicides in Soils. Modelling of the Leaching Process. Geoderma 2018, 313, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.D.P.; Torstensson, L.; Stenström, J. Biobeds for Environmental Protection from Pesticide Use A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6206–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámiz, B.; Celis, R.; Cox, L.; Hermosín, M.; Cornejo, J. Effect of Olive-Mill Waste Addition to Soil on Sorption, Persistence, and Mobility of Herbicides Used in Mediterranean Olive Groves. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, D.I. Groundwater Ubiquity Score: A Simple Method for Assessing Pesticide Leachability. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. Int. J. 1989, 8, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsby, A.G. Site-Specific Pesticide Recommendations: The Final Step in Environmental Impact Prevention. Weed Technol. 1992, 6, 736–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatica, P.; Di Guardo, A. Screening of Pesticides for Environmental Partitioning Tendency. Chemosphere 2002, 47, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadotto, C.A. Screening Method for Assessing Pesticide Leaching Potential. 2002.

- Laskowski, D.A.; Goring, C.A.; McCall, P.; Swann, R. Terrestrial Environment. Environ. Risk Anal. Chem. 1982, 198–240. [Google Scholar]

- Papa, E.; Castiglioni, S.; Gramatica, P.; Nikolayenko, V.; Kayumov, O.; Calamari, D. Screening the Leaching Tendency of Pesticides Applied in the Amu Darya Basin (Uzbekistan). Water Res. 2004, 38, 3485–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Herbicide |  |

Molecular formula |

Molecular mass |

log KOW | SWa | log KOCb | ||

| Exp. | MCI | log KOW | ||||||

| Chlorbromuron | R = Cl | C9H10BrClN2O2 | 293.5 | 3.1 | 35 | 2.70 | 2.53 | 2.58 |

| Metobromuron | R = H | C9H11BrN2O2 | 259.1 | 2.4 | 330 | 2.10 | 2.32 | 2.19 |

| Waste | pH (1:5) | EC (ds m-1) (1:5) | % OM | % OC (OCH) | % N | C/N | % FA | % HA | % ashes |

| SG | 4.53 | 1.17 | 79.63 | 46.19 (1.8) | 5.14 | 8.99 | 3.20 | 1.00 | 3.81 |

| GP | 3.56 | 2.77 | 80.45 | 46.67 (1.3) | 2.03 | 22.99 | 2.10 | 2.45 | 6.56 |

| GW | 5.17 | 2.52 | 85.23 | 49.44 (2.9) | 2.46 | 20.10 | 1.93 | 1.21 | 4.20 |

| OP | 3.14 | 1.42 | 73.61 | 42.7 (2.9) | 1.08 | 39.54 | 4.03 | 0.65 | 3.78 |

| F- | Cl- | NO3- | PO4- | SO4- | K | Ca | Mg | Na | |

| SG | 3446 | 434 | 40 | 5330 | 1632 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| GP | 871 | 93 | 378 | 5162 | 45138 | 0.19 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| GW | 759 | 3956 | 1362 | 12398 | 4762 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.05 |

| OP | 4504 | 2346 | 2550 | 4562 | 5142 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.08 | 0.05 |

| Soil | Log KOC | |

|---|---|---|

| Metobromuron | Chlorbromuron | |

| S | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| S + OP | 2.1 | 2.6 |

| S + SG | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| S + GW | 2.4 | 3.0 |

| S +GP | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Index | Equation | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| GUS [60] | GUS > 2.8: leachable; GUS = 1.8–2.8: transition; GUS < 1.8: non-leachable | |

| Hornsby Index [61] | HI ≤ 10: high; HI ≥ 2000: low | |

| LIN [62] | Comparison (lower values, lower leaching potential) | |

| LIX [63] | LIX = 1: high leachable; LIX = 0.1–1: leachable; LIX = 0–0.1: transition; LIX = 0: non-leachable | |

| LEACH [64] | Comparison (lower values, lower leaching potential) | |

| M. LEACH [65] | Comparison (lower values, lower leaching potential) | |

| GLI [65] | GLI > 1: high; GLI = -0.5-1: medium; GLI < -0.5: low | |

| ELI [22] | ELI ≤ 0.1: Immobile; 0.1 > ELI ≤ 0.6: Transition; 0.6 > ELI ≤1.5: Mobile, 1.5 > ELI ≤2: Very mobile. |

| Soil | Index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GUS | LIX | LEACH | MLEACH | LIN | GLI | HORNSBY | ELI | |

| Metobromuron | ||||||||

| S | 3.674 | 0.374 | 16064 | 2313 | 0.843 | 1401 | 143 | 1.314 |

| S + OP | 2.232 | 0.001 | 2713 | 39.12 | 0.743 | 24.91 | 843 | 0.893 |

| S + SG | 1.872 | 0.001 | 1582 | 23.22 | 0.703 | 15.01 | 1443 | 0.643 |

| S + GW | 1.882 | 0.001 | 1362 | 19.62 | 0.603 | 13.11 | 1673 | 0.122 |

| S +GP | 1.932 | 0.001 | 1452 | 20.92 | 0.603 | 13.91 | 1573 | 0.562 |

| Chlorbromuron | ||||||||

| S | 2.974 | 0.104 | 1983 | 10.53 | -0.432 | 7.71 | 333 | 0.081 |

| S + OP | 2.592 | 0.022 | 1133 | 6.23 | -0.482 | 4.91 | 563 | 0.001 |

| S + SG | 1.632 | 0.001 | 232 | 1.32 | -0.532 | 1.21 | 2783 | 0.061 |

| S + GW | 1.722 | 0.001 | 352 | 1.92 | -0.682 | 1.71 | 1883 | 0.001 |

| S +GP | 1.672 | 0.001 | 272 | 1.52 | -0.632 | 1.41 | 2403 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).