1. Introduction

Soil health is the sustained capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that supports plant, animal, and human life while connecting agricultural and soil science to policy, stakeholder needs, and sustainable supply chain management [

1]. Maintaining soil health is critical for ensuring the long-term sustainability of agriculture, safeguarding the environment, and promoting the well-being of populations. However, maintaining soil health faces several challenges, particularly regarding nutrient management and the replenishment of organic matter (OM) [

2]. One potential solution to address these challenges, including the concept of circular economy, is the utilization of SS in agriculture [

3]. SS is a complex matrix due to its challenging nature and diverse composition [

4]. According to the most recent information from Eurostat, in 2021, approximately 15 million tons of sludge (dry matter) were produced in the EU-28. [

5].

The exponential growth of the population and rapid urbanization have led to the generation of significant volumes of semisolid waste residues [

6]. The widespread acceptance of utilizing these residues in agriculture, referred to as SS application, highlights its effectiveness as a commonly practiced approach [

6], [

7]. Applying SS to soil offers a viable solution for meeting the demand for renewable nutrient sources while mitigating the negative impact of chemical fertilizers. The presence of organic constituents within SS can improve soil properties and fertility by acting as a soil conditioner. This can result in enhancements such as increased water-holding capacity, improved porosity, reduced bulk density, and enhanced stability of soil aggregates [

8]. SS applications have also boosted crop yield and improved plant characteristics. For instance, the application of significant amounts of dried SS to soils (ranging from 10% to 40%) has demonstrated enhanced yield biomass in

Brassica juncea L. [

9]. A study by Eid et al. (2021) demonstrated that applying SS positively influenced tomato plants' growth compared to those cultivated in non-amended soils. Various SS application rates (10, 20, 30, and 40gr/kg) significantly increased shoot and root lengths and leaf area compared to the control group. All SS doses demonstrated a notable improvement in OM percentage and electrical conductivity (EC), with a minor decrease in pH values observed compared to soils that did not receive treatment. Notably, 30gr/kg SS application significantly increased 48.5% in soil OM and 93.5% in EC relative to the non-amended soil. This specific dose led to a remarkable increase of 158% in nitrogen (N) levels and 51.5% in potassium (K) levels compared to the control soil [

6]. Research by Mohamed et al. demonstrated that SS also had beneficial effects on the morphological and eco-physiological parameters of sunflower (

Helianthus annuus L.) seedlings, as well as the soil chemical characteristics in Meknès-Saïs, Morocco [

10].

While the significance and effectiveness of SS for soil application in agriculture are undeniably evident, it is imperative to exercise caution and implement stringent in this practice [

6]. As an unavoidable byproduct resulting from the operation of municipal wastewater treatment plants, the sustainability of using sludge in agriculture has been a matter of contention, primarily due to its potential adverse effects on human and environmental health [

11]. In the EU, the application of SS as an agricultural amendment is subject to compliance with the quality requirements stipulated in the Council Directive (86/278/EEC)

1, which regulates the utilization of SS in agriculture. All EU MS are required to monitor sludge applications to prevent the accumulation of HMs in soil from exceeding specified limits. Having been in effect since 1986, the Directive has remained unchanged without experiencing significant revisions. However, heading towards a revised version of the Directive, the working document SWD-2023 - final {158} was officially disclosed in May 2023. This was initiated and developed under the auspices of the EU Green Deal, the Updated Bio-economy Strategy, and the EU Circular Economy Action Plans adopted in 2015 and 2020. Noteworthy is that the use of SS, compost, and other organic waste as organic soil amendments is a fundamental strategy to comply with the Landfill Directive 2018/850 and with the “end-of-waste” policy in Europe.

Regarding the pollutants identified in SS, HMs tend to accumulate in SS, where they are dissolved, precipitated, coprecipitated with metal oxides, absorbed, or assimilated with biological residues [

12]. HMs are divided into two groups. The first one, including cadmium, lead, and mercury, is characterized by high toxicity to humans and animals but lower toxicity for the growth and development of plants. In excess, the metals of the second group, i.e., copper, zinc, and nickel, are more toxic to plants than to animal and human organisms [

13]. The translocation of HMs into the food chain accounts for 90% of human contact, with the remaining 10% resulting from inhalation and dermal exposure [

14].

Besides the presence of the HMs, which seem well studied, the presence of MPs in soils has become increasingly evident in recent years [

15]. MPs pose significant challenges to soil health, disrupt the balance of ecosystems, and can have implications for Food Safety, as they can be easily transported to plants [

16,

17]. Those contaminants are ubiquitously found in various ecosystems, such as soil, rivers, wetlands, marine, and mountains, due to continuous discharge by human activities and inadequate management [

18]. Currently, much less is known about MP pollution in terrestrial ecosystems [

19], however, between 360 and 1980 tons of MPs in the EU could reach municipal wastewater treatment plants annually [

20]. The European Green Deal develops a zero-pollution vision for 2050 and the subsequent Zero Pollution Action Plan (ZPAP) [

21]. ZPAP will address emerging pollutants such as MPs and micropollutants, including pharmaceutical pollutants. However, pollution from such contaminants is not regulated, and the last updated working document (SWD-2023) – {final 158} does not yet consider the MPs, despite the risk that SS land applications could create a pathway for MPs to enter and accumulate in agricultural soils.

Considering SS's complexity, extent, and multi-level involvement in various environmental and social parameters, implementing and updating relevant directives and legislation is imperative and of immediate priority. One of this article's objectives is to review the applicable legislation within the European framework and at the MS national level. Additionally, the article seeks to examine and document the relevant legislative frameworks, particularly their limitations, control and environmental protection procedures, and regulations designed to ensure pollution-free European soil. Finally, this study aims to identify and monitor the updated SWD-2023 - final {158} working document, highlighting its deficiencies and gaps and outlining potential enhancements and suggestions for future improvement.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review of the applicable legislation was developed in two stages. The first refers to the SS socio-economic and environmental impacts on the primary Agriculture sector by searching international databases, including the Web of Science2, Google Scholar3, and Scopus4. The second stage included the SS legislative frameworks by searching each EU MS’s official national Ministerial (responsible for SS laws and regulations) web pages and the Eurostat. The software used for bibliographic management was Zotero for Windows (v6.0.36)5 for duplication search. The primary keywords selected for the database search were Sewage Sludge, Soil Health, and Heavy Metals Policies. These were linked with other words such as EU legislation, food safety, microplastics, compost, incineration, bioenergy, contamination, antibiotics and sludge treatment.

Approximately 600 research papers addressing the first stage of this methodology were considered eligible. These were assessed by evaluating the title, abstract, and relevant data to remove irrelevant studies. Following an assessment of the data's quality, methodology, and relevance to this current study, 63 research papers were deemed suitable for this review. All research papers are from 2014 to 2024 to obtain the most up-to-date data, innovations, and trends on the subject examined.

The methodology's second part includes statistical analysis conducted using R (version 4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) [

22]. Data manipulation and visualization were performed with packages such as dplyr and ggplot2, respectively. Summary statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated for pollutant concentrations, with visualizations highlighting regional variations. All maps visualization, editing, and preparation were created using the free and open-source Qgis software (version 3.43)

6.

3. Results

3.1. Council Directive 86/278/EEC

The 86/278/EEC Directive establishes thresholds for hazardous surface water and soil substances that receive sludge applications. However, since its inception in 1986, the Directive has remained unchanged, resulting in its obsolescence. The Council Directive has banned untreated sludge and introduced specific regulations for the sampling and examining sludge and soil to prevent adverse consequences [

23]. It stipulates the necessity of maintaining thorough documentation concerning (i) the quantities of sludge generated, (ii) the quantities utilized in agriculture, (iii) the composition and characteristics of the sludge, (iv) the treatment processes involved, and (v) the locations and guidelines of sludge application

7. As an illustration, per Article 8 of the Directive, if soil pH levels dip below 6, it is crucial to consider the amplified mobility and availability of HMs to the crops when utilizing sludge.

The regulation outlined in Regulation (EU) 2019/1009 directly confronts the issue of SS composting. It establishes strict restrictions on the amount of SS allowed in fertilizing products across the EU. Consequently, fertilizing products that incorporate composts and digested materials sourced from SS will be prohibited from being commercially available in the EU market, with the CE marking beyond July 2022.

Additionally, the FAO's report on wastewater treatment and its utilization in agriculture offers further insights in addition to the regulations set forth by the EU. Specifically, in Section 6 (Agricultural use of Sewage Sludge), point 6.2 (Sludge Application) [

24], the authors present the maximum allowable concentrations of potentially toxic elements (PTE) in the soil after the application of SS [

25]. This document outlines the maximum permissible concentrations of potentially toxic elements in the soil following the application of SS and specifies the maximum addition annual rates.

The report 'Developing Human Health-Related Chemical Guidelines for Reclaimed Water and SS Applications in Agriculture', produced by Chang et al. for the WHO, presents a detailed analysis of the maximum allowable concentrations of pollutants in the receiving soils. Notably, this report presents threshold values for specific elements, including Silver (Ag), Boron (B), Beryllium (Be), Titanium (Ti), and Vanadium (V), which were not part of the FAO document and Council Directive [

26].

Table 1. illustrates the permissible concentrations of toxic pollutants and the differences observed between WHO, FAO and the Council Directive.

Concerns regarding potential environmental hazards stemming from obsolete EU legislations have prompted certain MS to enact stricter regulations surpassing EU directives' boundaries. Consequently, there has been an increase in the number of pollutants being monitored. The varying strategies employed by EU MS in the agricultural application of SS contribute to differences in the permissible limits for these pollutants [

27].

Table 2. lists the applicable legislations of all 28 MS that define, delimit, and concern SS use processes.

As illustrated in

Table 3, a dominant finding concerns the joint recognition and institutionalization of legislation by almost all MS for seven HMs when SS is amended. Cadmium, nickel, lead, zinc, mercury, copper, and chromium are among them. During this study, Bulgaria was the only exception that had yet to enact relevant legislation. The next studied statutory HM that has been adapted and incorporated into the legislation of several MS, such as Germany, France, the Netherlands and Italy, is arsenic. Individual quantitative characteristics also identified by the review of MS legislations concern the state with the highest number of HMs incorporated into relevant legislation, locating Germany with 14 recognized HMs, Italy and the United Kingdom with 10, and France with 9. In contrast, the countries with the lowest number of HMs regulated are Poland, with 5; Estonia, Spain and Sweden, with 6. Qualitative characteristics include the finding that several Mediterranean MS constitute the group with the smallest number of HMs that comply with their legislations. Greece, Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, and Portugal count 7 HMs in contrast to MS of central and northern Europe, which include more than 8 in their legislations, such as the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia.

It is essential to highlight that, aside from the considerable diversity in the number of HMs included in MS regulations, there is also a substantial disparity in the acceptable threshold limits of HMs in SS when intended for agricultural use. The degree of variation in each case of HMs varies, with the common factor being the noticeable differences presented in

Table 4. As an illustration, in the case of Cadmium, Finland limits the minimum statutory value to 0.5 mg/kg

-1 (dry matter). In comparison, Cyprus specifies the maximum value at 40 mg/kg

-1 (dry matter) in its national legislation. Likewise, the statutory value for Chromium in Austria is established at 70 mg/kg

-1 (dry matter). In contrast, according to their legislation, Slovakia, Portugal, and Cyprus have set a maximum value of 1,000 mg/kg

-1 (dry matter). One potential common point of approach may be the observation that the strictest limits have been established by MS of the European north, including Finland, Belgium, Germany, Austria, and Ireland. Another intriguing aspect is the absence of defined permissible values for Copper and Zinc in Poland. On the other hand, HMs such as Thallium, Beryllium, Vanadium, and Molybdenum are officially included in the legislative framework of Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Hungary, and Italy.

Here, different ways of approaching and calculating the data can be found, as in several cases, these are calculated as an average of two years, five years, or even a decade. Many MS have not submitted relevant data regarding this specific indicator, making it impossible to draw safe conclusions. Sweden, Finland, Austria, the Netherlands and Belgium belong to the group with the strictest framework of permissible limits annually. The range of deviations in the legislation is also reflected in the vast range of prices per case of HMs when it is indicated that the values for Nickel start from 60 grams per hectare for the Netherlands and reach 3 kilograms per hectare for the United Kingdom, Romania, Spain and Portugal.

Table 5 presents the availability of data derived from Eurostat regarding the annual permissible limits.

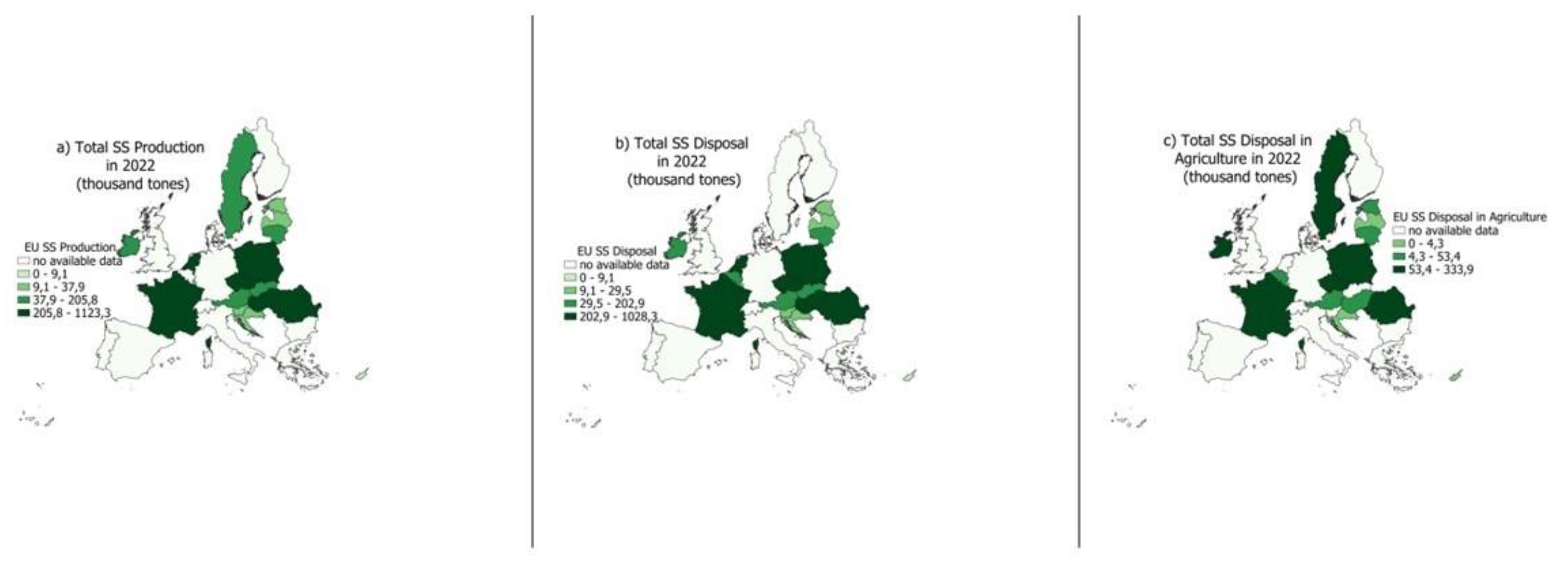

According to the latest Eurostat data for 2022

8, most MS have submitted data regarding the production and disposal of SS. However, 10 MS have not released official data. France and Poland recorded the largest production and disposal of SS, with 1,123.31 and 580.66 thousand tons of production, respectively. The highest SS amounts amended in broader agriculture (out of the total output) were recorded in Poland with a percentage of 27.1%, France at 29.7%, Sweden at 52.3%, the Czech Republic at 35%, and Romania at 30%. It is diametrically opposite, as shown in

Table 6. Malta, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Slovenia don’t select agricultural disposal as an option.

Figure 1. shows the relevant data on sludge production and agricultural utilization in the MS.

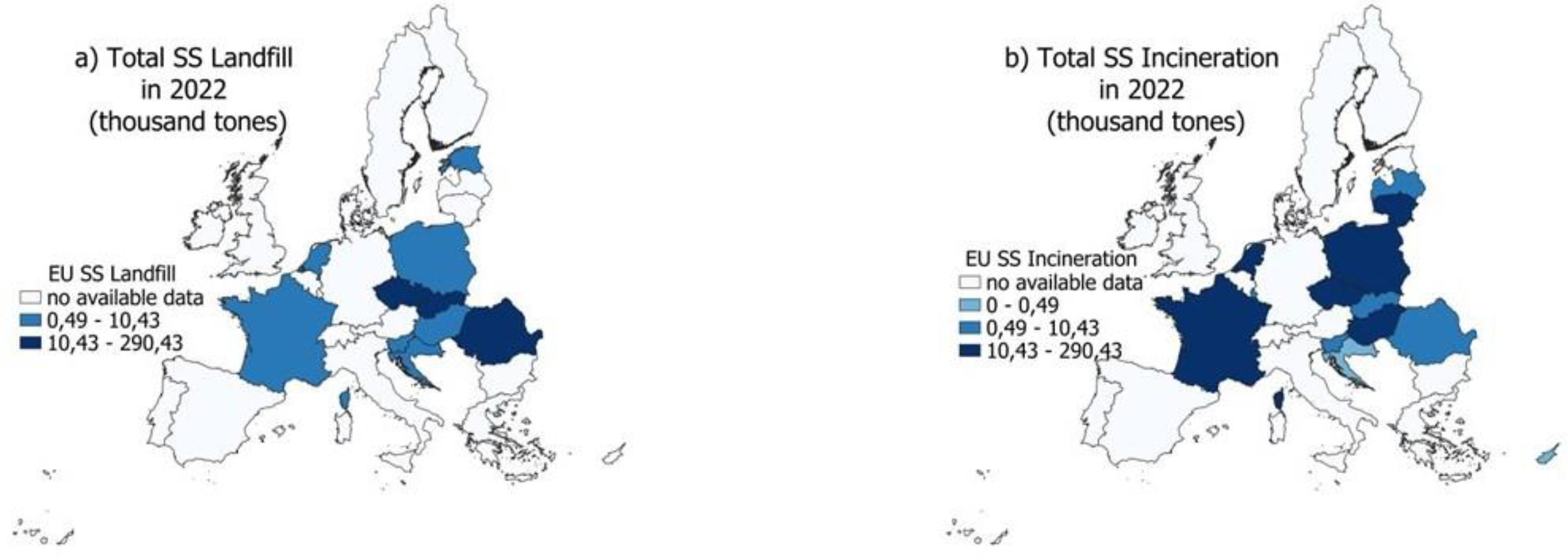

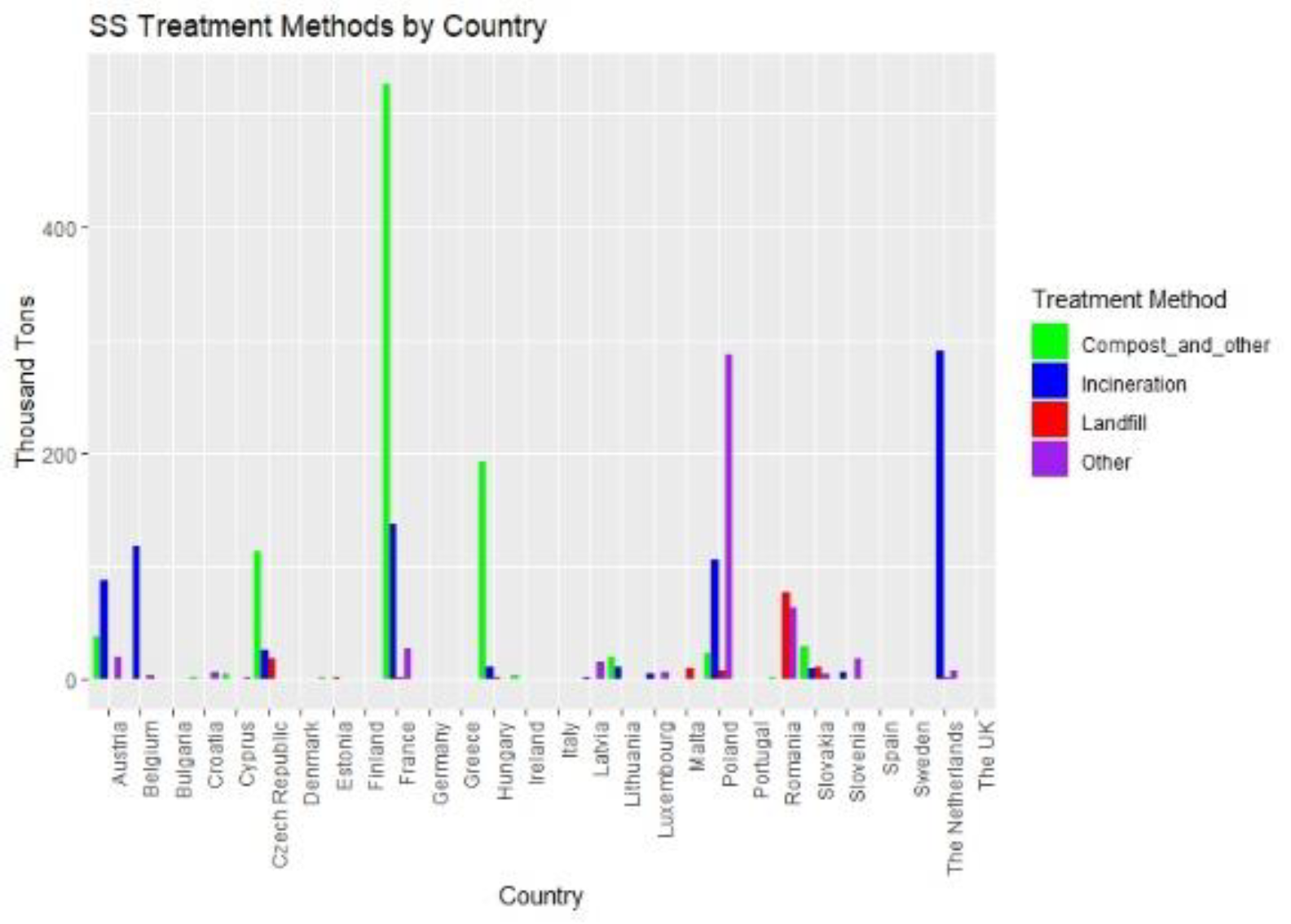

In 2022, the officially recorded data also shows a lack of information on SS treatment methods for the same 10 MS mentioned above. Spain, Denmark, Greece, Germany, and Portugal have not offered quantitative data. At the EU level, incineration treatment and composting are the prevailing methods. The Netherlands, France, Poland, and Belgium are the top countries in the thermal treatment of SS, while Croatia, Ireland, Cyprus, Malta, and Latvia rank the lowest. Landfill management is viewed as a less suitable option due to its small size, but it remains the dominant choice for Malta. Hungary heavily favours composting/other applications, which comprise around 77% of the country’s production, whereas France accounts for about 47%.

Table 7 and

Figure 2. present and visualize the volumes of SS's thermal, landfill and compost treatment for 2022. In

Table 7, the Total (MV) indicates the cumulative count of missing values related to treatment methods across the EU-28.

3.2. Statistical Analyses Results

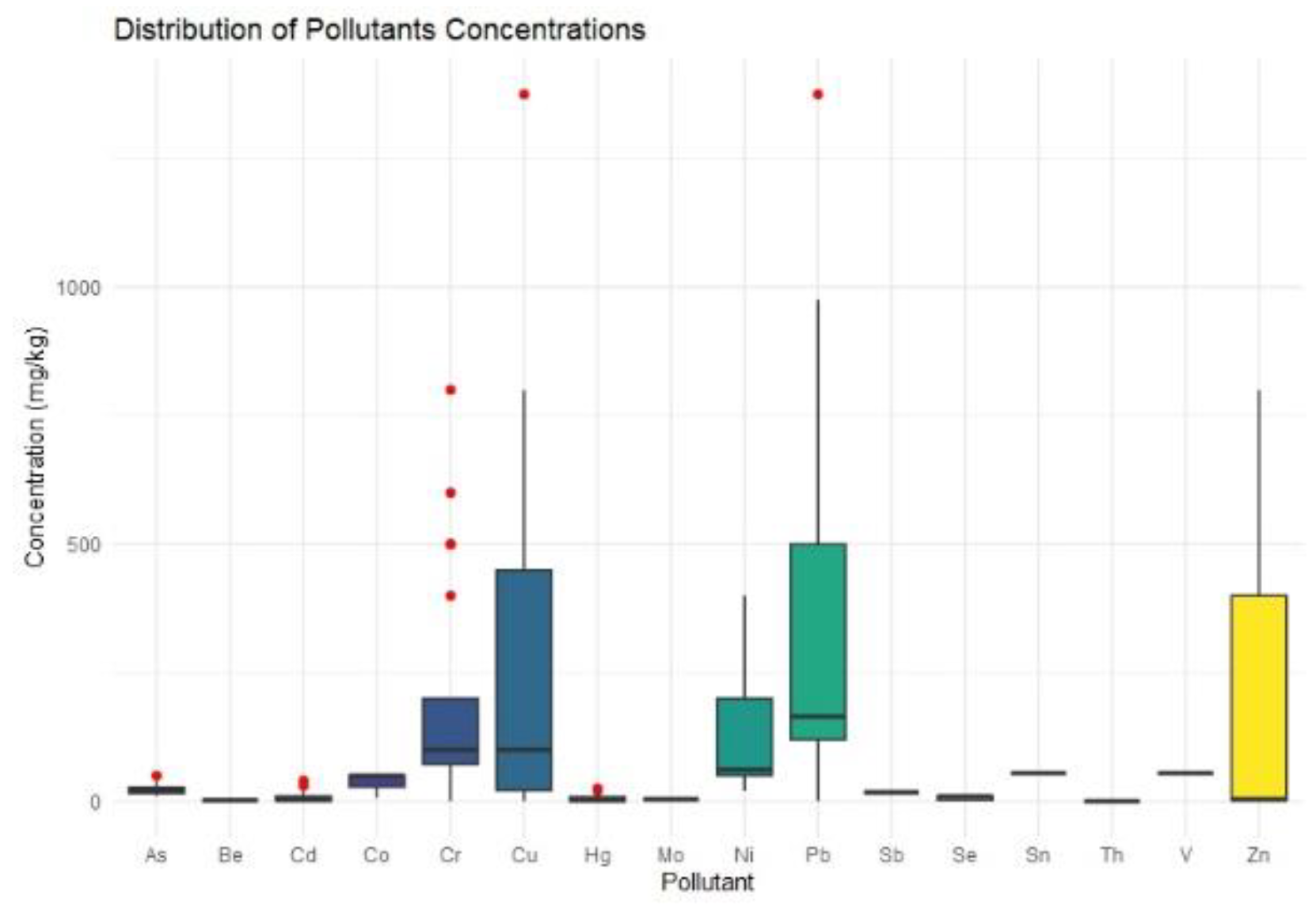

Statistical variables were created in the R-integrated suite to collect and extract precise data for all HMs.

Table 8 presents the primary statistical data obtained.

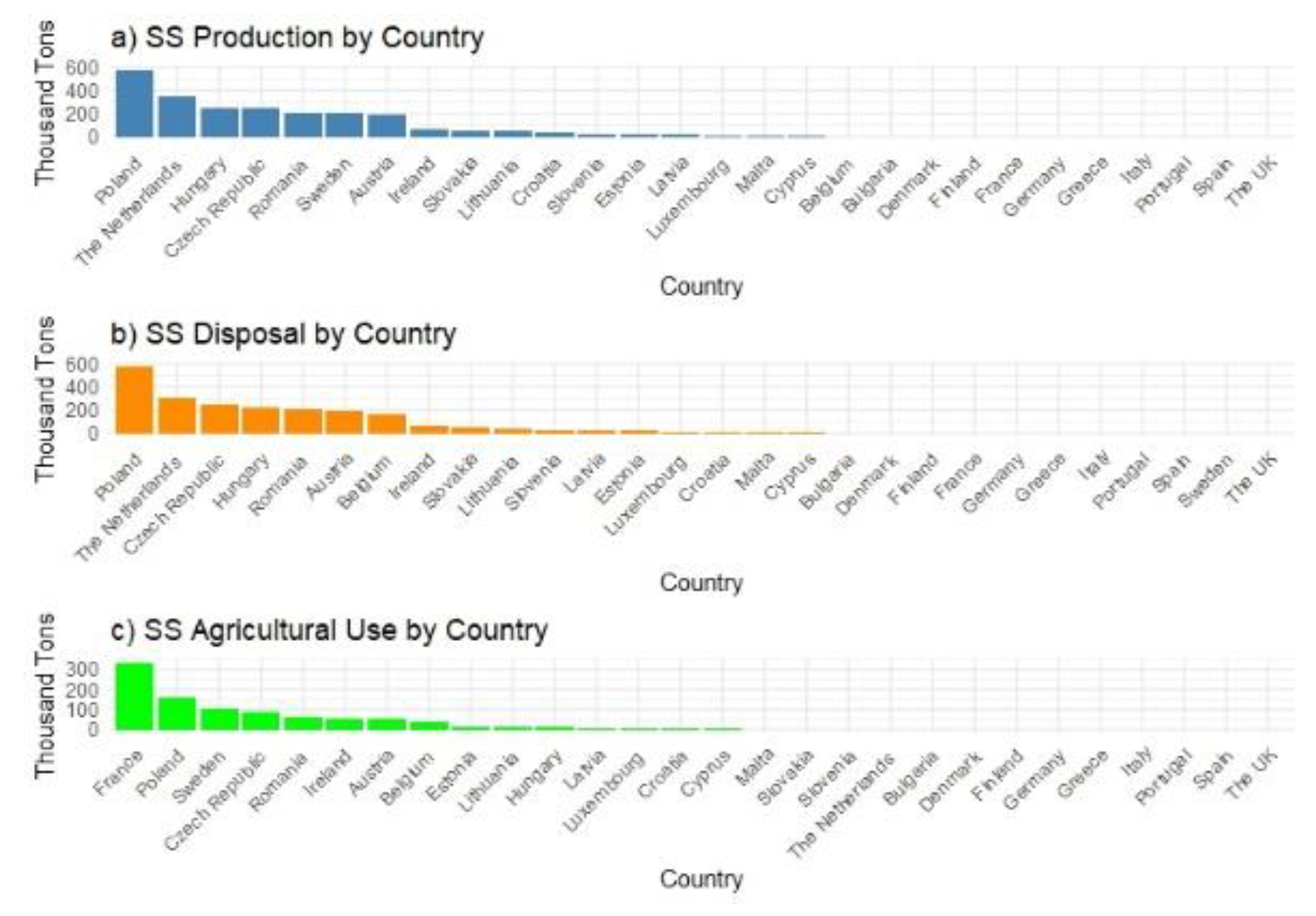

Figure 3. illustrates the distribution of SS production and disposal across the 28 MS and highlights the share of the total output applied in the agricultural primary sector. Poland, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, and Hungary are the leading states in terms of production and disposal. At the same time, France, Poland, and Sweden demonstrate the most considerable proportions of SS usage in agriculture.

In

Figure 4. the Boxplot illustrates the distribution and value ranges of HMs as dictated by the legislation of the 28 MS. The analysis reveals that Copper, Chromium, Lead, and Zinc possess the most significant value ranges. In contrast, all the remaining HMs exhibit minimal value variation, resulting in nearly identical values. Moreover, it is noteworthy that a substantial presence of outlier values characterizes Chromium.

The bar graph in

Figure 5 quantitatively illustrates the distribution of SS treatment strategies among MS. France and Hungary predominantly utilize composting for SS management. In contrast, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, and Poland favour incineration, whereas Romania primarily resorts to landfill.

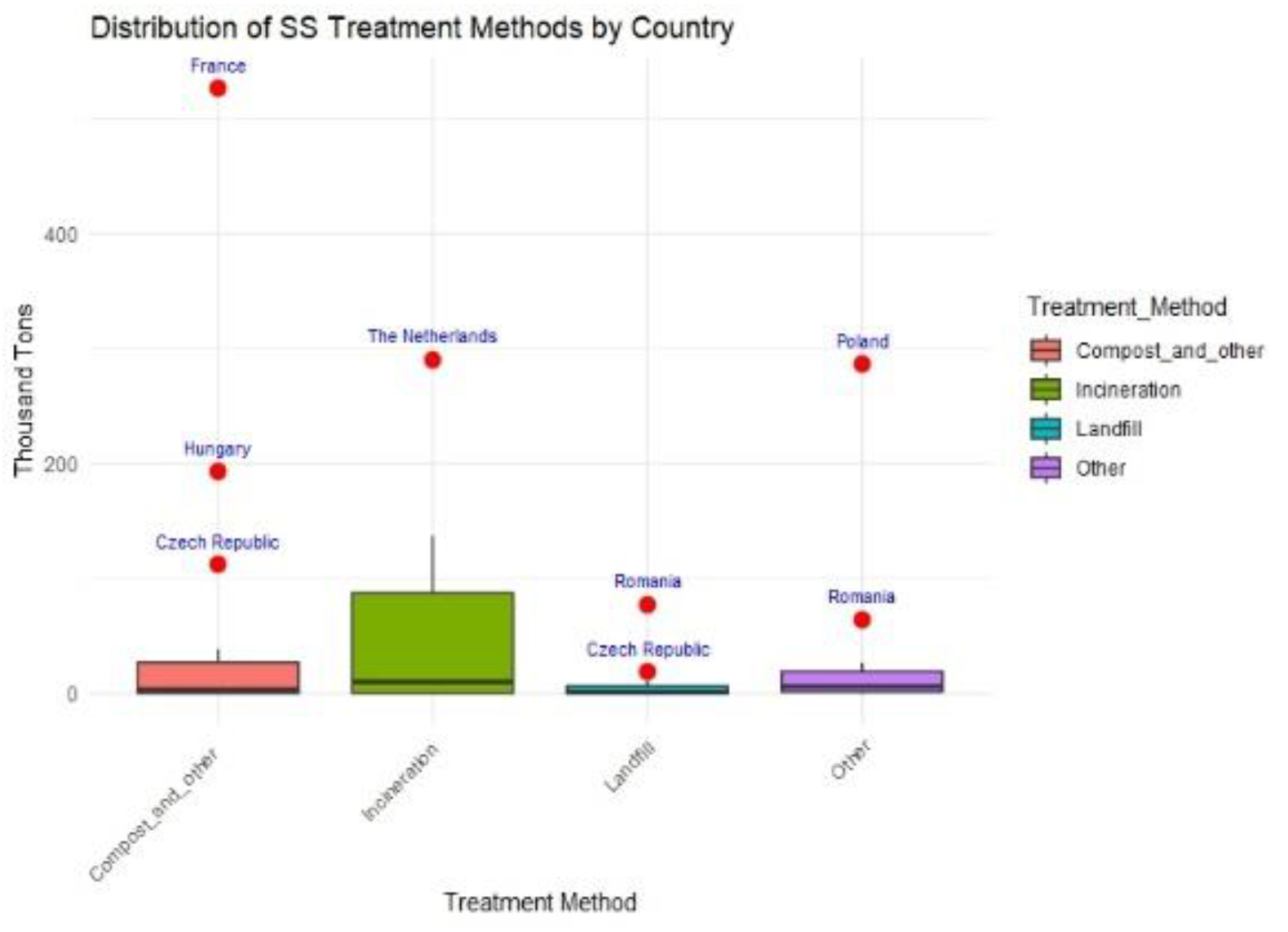

Figure 6. Again, presented in Boxplots, each treatment method's range of distributed values per MS is illustrated. A pronounced wide range of quantitative differentiation exists among MS, particularly in the incineration option, where opposing choices are starkly reflected in landfill preferences. Additionally, France's status as an outlier in composting options and the Netherlands' unique position in incineration options warrant attention.

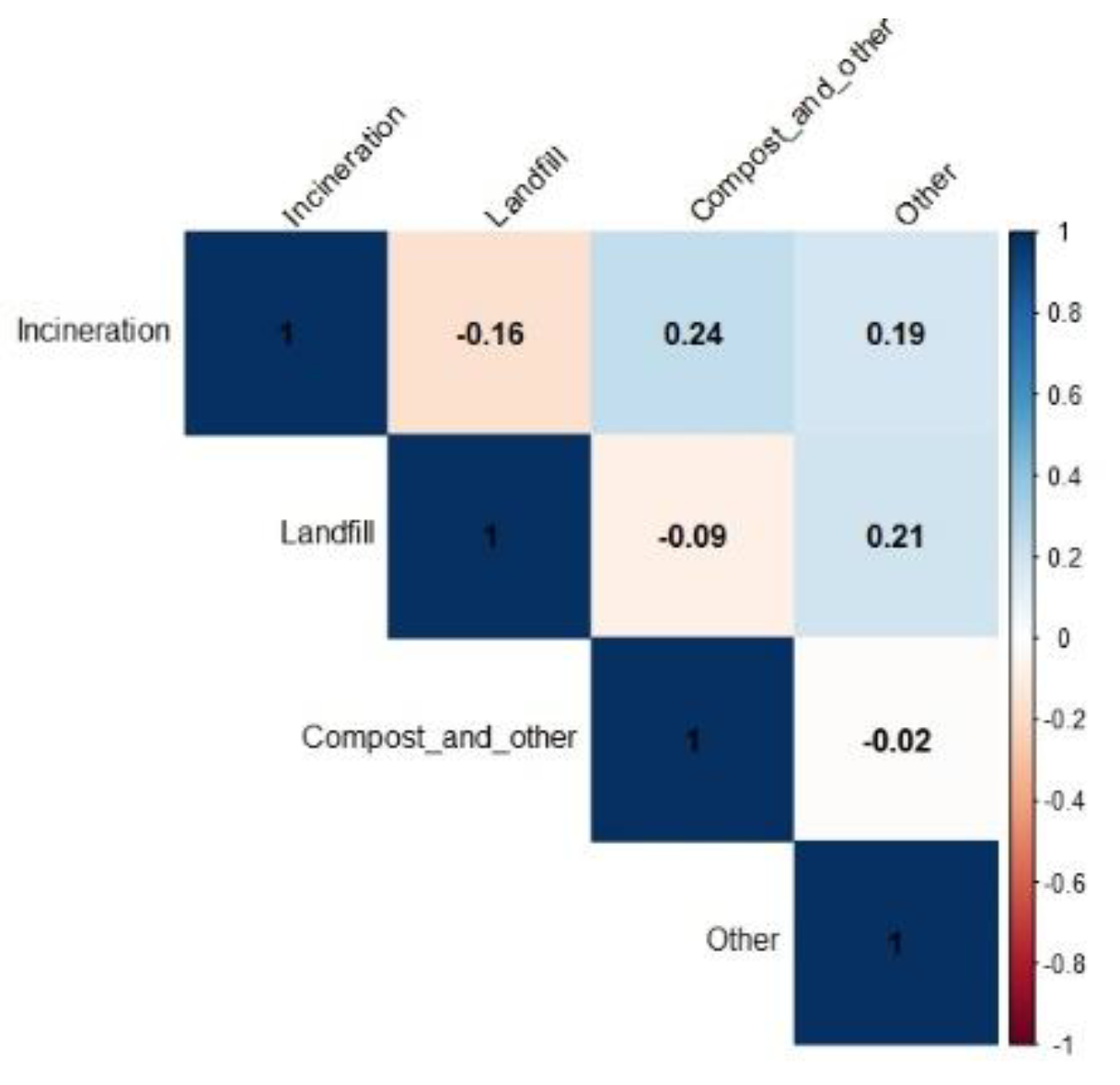

The analysis presented in

Figure 7. reveals the correlations among various SS treatment approaches. The highest positive correlation was identified between incineration and composting, yielding a correlation coefficient of r=0.24. The overall results indicate that the treatment methods show minimal correlations, suggesting a lack of significant frequency among the treatments. Furthermore, a slight negative correlation is observed between incineration and landfill, with a coefficient of r=-0.16, indicating negligible correlational tendencies.

4. Discussion

Water, energy, and food safety have ignited global environmental challenges in the last decades, primarily due to the increasing population. Global food safety will focus on finding new nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium sources to address the fast-growing population and improve crop yields. Apart from soil enrichment with OM [

28], the addition of SS could represent a renewable source of phosphorus. Currently, the EU Commission has included both white phosphorus (P4) and phosphate rock among the 20 Critical Raw Materials (CRM), as reported in the “Report on Critical Raw Materials for the EU” released in 2023 [

29]. Hence, SS utilization is an opportunity for industries across the agriculture chain to restore phosphorus in European soils and minimize our reliance on chemicals. Despite the above, the levels of HMs and MPs in crop products, particularly in developing countries, raised serious concerns about human health [

30]. Therefore, strict guidelines and regulatory oversight are necessary to prevent contamination of agricultural soils and ensure the safe use of SS and biosolids in food production and soil enhancement. The EU is instituting the Directive on Soil Monitoring and Resilience

11 to promote secure soil health and avert further soil degradation. This directive integrates various soil health descriptors to monitor soil conditions throughout the MS. Among those descriptors include the levels of extractable phosphorus, the concentrations of HMs like arsenic, antimony, cadmium, cobalt, chromium (both total and hexavalent), copper, mercury, lead, nickel, thallium, vanadium, and zinc, along with a selection of organic contaminants specified by the MS.

Analyzing trends in the management and application of SS in the EU proves to be challenging because of differences in terminology, inconsistencies in data collection, and varying national objectives and limitations imposed by individual EU MS. Ambiguities in terminology can give rise to diverse interpretations and inaccurate conclusions. For example, Eurostat's definition of 'agriculture' may diverge from its interpretation in the Council Directive. Furthermore, Eurostat's 'composting and other processes' classification may not correspond with its representation within the wider agricultural sector. Moreover, MS may classify the sludge used for plant cultivation in compost production differently, for example, as ‘reuse in compost’ or ‘other’. Another case outlined in the SWD-2023 working document pertains to Eurostat's data on SS production and disposal routes, which discusses SS dry matter. At the same time, the Council Directive lacks a specific definition of dry matter. Additionally, it has been observed that Eurostat offers limited insight into SS disposal. The information in the data and literature reviewed is limited regarding the comprehensive understanding of sludge management processes in different countries. For instance, there is a notable absence of readily accessible data on the quantities of SS undergoing anaerobic digestion treatment as an intermediate step before the final disposal outcomes are documented. The high level of inconsistency and lack of coherence in the datasets provided by MS necessitates further examination and resolution through consensus, synthesis, and collaboration among stakeholders, relevant parties, national authorities, and EU decision-making bodies.

Additionally, there is an inconsistency and absence of data provided by EU MS regarding SS production, disposal, agricultural use, and other relevant aspects. Countries like Spain, Portugal, Greece, Germany and Italy have not offered clear documentation and data until 202112. Specifically, as of the reference year 2018, 4 MS and 3 MS regions still need to supply data on the total amounts of SS production. Furthermore, for the indicator 'SS used in agriculture,' 3 MS and 3 MS regions have also lacked data, preventing definitive identification of trends within the EU. Ultimately, it appears paradoxical when examining the SS matter, as it becomes evident that despite the EU Members establishing, for example, the acceptable thresholds of HMs in soils, these limits can vary significantly in certain instances. Upon examining the values outlined in the individual state legislations, it is evident that there is no indication of uniformity and homogeneity. Significant inhomogeneity also exists in the case of the annual permitted HMs limits that are deposited in soils by SS. This discrepancy suggests that soil within the EU will inevitably exhibit varying levels of health in the future. Additionally, as shown from data obtained from Eurostat, the treatment methods of SS again vary across the EU. The interpretation of Soil contamination – Soil Health varies throughout the EU, resulting in diverse approaches to comprehending, controlling, and alleviating the adverse impacts of SS on soils.

Since the SS amendment involves a multi-prism of pollutants posing risks in the triangle Soil – Food – Human Health, to our best knowledge, it is necessary as an initial step to balance and set the SS issue in a proper and robust foundation to avoid different ‘’translations’’ and analyses of the SS matter. Moreover, the upcoming revisions or additions in a holistic legislation framework must include standardized methods for sampling, contamination prevention, validation, quality control procedures, and reproducible analytical methods for analyzing at least a significant part of the common soil pollutants in SS, such as the MPs. To enhance the accuracy and validity of future analytical research and data on MPs, it is recommended to establish certified reference materials for MPs in soil, certified MP particle standards (with different polymer types, sizes, shapes, and degrees of ageing), and labelled polymer standards with and without chemicals (e.g., absorbed and additive chemicals) as an initial target. Equal consideration should be given to advancing reliable, precise and widely accepted in-situ techniques for quickly detecting MPs in soil. Furthermore, the suggested future legislative framework should incorporate automated purification protocols to decrease labor intensity, background contamination, and potential errors.

5. Conclusions

SS is abundant in nutrients, which makes it potentially valuable as a fertilizer or soil conditioner. However, HMs in it restrict or even make it impossible to use. The EU regulates the use of SS in agriculture through Directive 86/278/EEC. Despite that, the Directive is limited in scope, addressing only a few specific organic pollutants and HM elements. Environmental pollutants, such as MPs, antibiotics, and pharmaceuticals, present in biosolids have not been adequately investigated or regulated widely to mitigate the risk of their release into the environment and their adverse impact on ecosystems.

A comprehensive review and assessment of the European legislative frameworks concerning SS have been conducted at the national level of the EU 28 MS, considering the permissible levels of all HMs specified in their relevant regulations and directives. The study highlights significant diversity in the legislative frameworks across the EU-28. All MS adopted different strategies in establishing regulations for applying SS in agricultural fields. Noteworthy differences exist in the limit levels for SS usage in the agriculture sector. The study reveals a lack of consensus regarding the optimal treatment strategies for SS, establishing a standardized definition of MPs, determining acceptable values, and specifying the types of HMs covered in relevant legislations. Hence, the authors express scepticism regarding the practicality of these limited values in addressing health concerns at a broader level across the EU.

Furthermore, the study explored the involvement of the SWD-2023 {final 158} working document in incorporating recommendations and guides for phosphorus recovery and any initial efforts to oversee and regulate MPs. Endeavours are pinpointed here to reduce and define regulatory thresholds for MPs, specifically within the domains of Cosmetics and Medical procedures. In countries like France, the UK, Sweden, and Italy, national legislation prohibits the sale of any substance in the MP state that is 5 mm or more minor in size [56]. In Luxembourg, the concentration is calculated to be equal to or exceeding 0.01 percent, denoting the ratio between the mass of the MP and the total mass of the sample material that includes the MP. The diverse velocities in EU-28 are also evident in the context of the phosphorus recovery strategies, which in plenty of MS is not even included in their legislations, whereas is currently being formulated in Sweden. The German strategy is a reference point for developing the Swedish strategy. Despite legislation on phosphorus recovery in the Netherlands since 2015, implementation has proven to be challenging.

Hitherto, we conclude that regulatory autonomy exists within the EU; however, to achieve harmonization in such a sensitive environmental matter and to embrace a harmonized holistic approach that accounts for the distinct soil and climatic features of each MS is imperative. Furthermore, it is essential to recognize that Soil pollution is a shared challenge within the EU and requires a more standardized legal framework for effective management. Part of a future potential recommendation and suggestion could be to create separate SS management processes tailored to each treatment plant or even in greater scales referring to local regions.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D.K. and I.V.; methodology, D.K.; software, D.K., Z.P. and I.V; validation, I.V.; formal analysis, Z.P.; investigation, D.K.; resources, D.K.; data curation, Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K and I.V.; visualization, D.K., Z.P. and I.V.; supervision, I.V.; project administration, I.V. and D.H.; funding acquisition, I.V. and D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

“H2020 EXCELSIOR, grant number 857510 funded this research”

Data Availability Statement

This study did not create or analyze new data, and data sharing does not apply to this article.

Acknowledgements

1. The authors acknowledge the 'EXCELSIOR': ERATOSTHENES: Excellence Research Centre for Earth Surveillance and Space-Based Monitoring of the Environment H2020 Widespread Teaming project (

www.excelsior2020.eu). The 'EXCELSIOR' project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 857510, from the Government of the Republic of Cyprus through the Directorate General for the European Programmes, Coordination and Development and the Cyprus University of Technology.2. The authors acknowledge the 'GreenCarbonCY': Transitioning to Green agriculture by assessing and mitigating Carbon emissions from agricultural soils in Cyprus. The GreenCarbonCy project has received funding from the European Union - Next Generation, the Recovery and Resilience Plan "Cyprus_tomorrow", and the Research & Innovation Foundation of Cyprus under the Restart 2016-2020 Program with contract number CODEVELOP-GT/0322/0023.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Notes

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

References

- I. Martin, “Main drivers on food security takled in Commission Document,” European Compost Network. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.compostnetwork.info/main-drivers-on-food-security-takled-in-commission-document/.

- M. Rastogi et al. “Soil Health and Sustainability in the Age of Organic Amendments: A Review,”. IJECC 2023, 13, 2088–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Bagheri, T. Bauer, L. E. Burgman, and E. Wetterlund. “Fifty years of sewage sludge management research: Mapping researchers’ motivations and concerns,”. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 325, 116412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites in sewage sludge and soil: A review on their distribution and environmental risk assessment - ScienceDirect.” Accessed: Aug. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221415882100012X.

- L. Ivanová et al. “Pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs - A new threat to the application of sewage sludge in agriculture,”. Sci Total Environ 2018, 634, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Eid et al., “Sewage sludge enhances tomato growth and improves fruit-yield quality by restoring soil fertility,” Plant, Soil and Environment 2021, 67. [CrossRef]

- F. Mercl, Z. Košnář, L. Pierdonà, L. M. Ulloa-Murillo, J. Száková, and P. Tlustoš. “Changes in availability of Ca, K, Mg, P and S in sewage sludge as affected by pyrolysis temperature,”. Plant, Soil and Environment 2020, 66, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Kominko, K. Gorazda, and Z. Wzorek. “The Possibility of Organo-Mineral Fertilizer Production from Sewage Sludge,”. Waste Biomass Valor 2017, 8, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. I. Dar, I. D. Green, M. I. Naikoo, F. A. Khan, A. A. Ansari, and M. I. Lone, “Assessment of biotransfer and bioaccumulation of cadmium, lead and zinc from fly ash amended soil in mustard-aphid-beetle food chain,”. Sci Total Environ 2017, 584–585, 1221–1229. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohamed, K. Mounia, A. Aziz, H. Ahmed, B. Rachid, and A. Lotfi. “Sewage sludge used as organic manure in Moroccan sunflower culture: Effects on certain soil properties, growth and yield components,”. Science of The Total Environment 2018, 627, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Cheng, L. Wu, Y. Huang, Y. Luo, and P. Christie, “Total concentrations of heavy metals and occurrence of antibiotics in sewage sludges from cities throughout China,”. Journal of Soils and Sediments 2014, 14. [CrossRef]

- J. Latosińska, R. Kowalik, and J. Gawdzik, “Risk Assessment of Soil Contamination with Heavy Metals from Municipal Sewage Sludge,”. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- S. Delibacak, L. Voronina, and E. Morachevskaya. “Use of sewage sludge in agricultural soils: Useful or harmful,”. EURASIAN JOURNAL OF SOIL SCIENCE (EJSS) 2020, 9, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N. Loutfy, M. Fuerhacker, P. Tundo, S. Raccanelli, A. G. El Dien, and M. T. Ahmed. “Dietary intake of dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs, due to the consumption of dairy products, fish/seafood and meat from Ismailia city, Egypt,”. Science of The Total Environment 2006, 370, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. He, Y. Wei, C. Yang, and Z. He. “Interactions of microplastics and soil pollutants in soil-plant systems,”. Environmental Pollution 2022, 315, 120357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A. Dreshaj, B. Millaku, A. Gashi, E. Elezaj, and B. Kuqi. “Concentration of Toxic Metals in Agricultural Land and Wheat Culture ( Triticum Aestivum L. ),”. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I. Azeem et al., “Uptake and Accumulation of Nano/Microplastics in Plants: A Critical Review,”. Nanomaterials 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- H. Jia, D. Wu, Y. Yu, S. Han, L. Sun, and M. Li. “Impact of microplastics on bioaccumulation of heavy metals in rape (Brassica napus L.),”. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao et al. “A critical review on the interactions of microplastics with heavy metals: Mechanism and their combined effect on organisms and humans,”. Sci Total Environ 2021, 788, 147620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Nizzetto, M. Futter, and S. Langaas, “Are Agricultural Soils Dumps for Microplastics of Urban Origin,” Environmental Science and Technology 2016, ASAP,. [CrossRef]

-

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Towards a monitoring and outlook framework for the zero pollution ambition Accompanying the document Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Pathway to a Healthy Planet for All EU Action Plan: “Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil.” 2021. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52021SC0141.

- “R: The R Foundation.” Accessed: Oct. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.r-project.org/foundation/.

- N. Nunes, C. Ragonezi, C. S. S. Gouveia, and M. Â. A. Pinheiro de Carvalho. “Review of Sewage Sludge as a Soil Amendment in Relation to Current International Guidelines: A Heavy Metal Perspective,”. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6. Agricultural use of sewage sludge.” Accessed: Aug. 29, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.fao.org/4/T0551E/t0551e08.htm.

- M. Pescod, “Wastewater treatment and use in agriculture - FAO irrigation and drainage paper 47,” 1992. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Wastewater-treatment-and-use-in-agriculture-FAO-and-Pescod/e6e5fa11aa40cb1cc282c844005aa2421b557a21.

- A. Chang, G. Pan, A. Page, and T. Asano, “Developing Human Health-related Chemical Guidelines for Reclaimed Waster and Sewage Sludge Applications in Agriculture,” Jan. 2001.

- H. Hudcová, J. Vymazal, and M. Rozkošný, “Present restrictions of sewage sludge application in agriculture within the European Union,”. Soil and Water Research 2018, 14. [CrossRef]

- E. Epstein, Land Application of Sewage Sludge and Biosolids. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (European Commission), M. Grohol, and C. Veeh, Study on the critical raw materials for the EU 2023: final report. Publications Office of the European Union, 2023. Accessed: Jul. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2873/725585.

- Y. Lee, J. Cho, J. Sohn, and C. Kim. “Health Effects of Microplastic Exposures: Current Issues and Perspectives in South Korea,”. Yonsei Medical Journal 2023, 64, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

1. The authors acknowledge the 'EXCELSIOR': ERATOSTHENES: Excellence Research Centre for Earth Surveillance and Space-Based Monitoring of the Environment H2020 Widespread Teaming project (www.excelsior2020.eu). The 'EXCELSIOR' project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 857510, from the Government of the Republic of Cyprus through the Directorate General for the European Programmes, Coordination and Development and the Cyprus University of Technology.2. The authors acknowledge the 'GreenCarbonCY': Transitioning to Green agriculture by assessing and mitigating Carbon emissions from agricultural soils in Cyprus. The GreenCarbonCy project has received funding from the European Union - Next Generation, the Recovery and Resilience Plan "Cyprus_tomorrow", and the Research & Innovation Foundation of Cyprus under the Restart 2016-2020 Program with contract number CODEVELOP-GT/0322/0023.

1. The authors acknowledge the 'EXCELSIOR': ERATOSTHENES: Excellence Research Centre for Earth Surveillance and Space-Based Monitoring of the Environment H2020 Widespread Teaming project (www.excelsior2020.eu). The 'EXCELSIOR' project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 857510, from the Government of the Republic of Cyprus through the Directorate General for the European Programmes, Coordination and Development and the Cyprus University of Technology.2. The authors acknowledge the 'GreenCarbonCY': Transitioning to Green agriculture by assessing and mitigating Carbon emissions from agricultural soils in Cyprus. The GreenCarbonCy project has received funding from the European Union - Next Generation, the Recovery and Resilience Plan "Cyprus_tomorrow", and the Research & Innovation Foundation of Cyprus under the Restart 2016-2020 Program with contract number CODEVELOP-GT/0322/0023.