Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Prostate and Breast Cancer Clinicogenomics

2.2. Cells and Reagents

2.4. Cell Viability Assays

2.5. Transfection Assays

2.6. Doubling Time Assays

2.7. Migration and Invasion Assays

2.8. Western Blot Analysis

2.9. Flow Cytometry

2.10. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Increased STMN1 Is Associated with Increased MET and HGF in mCRPC

3.2. Increased STMN1 and HGF Expression Is Associated with Liver Metastasis and Decreased Overall Survival

3.3. STMN1 and MET Predict Response to Taxane Chemotherapy in Node-Positive BC Patients

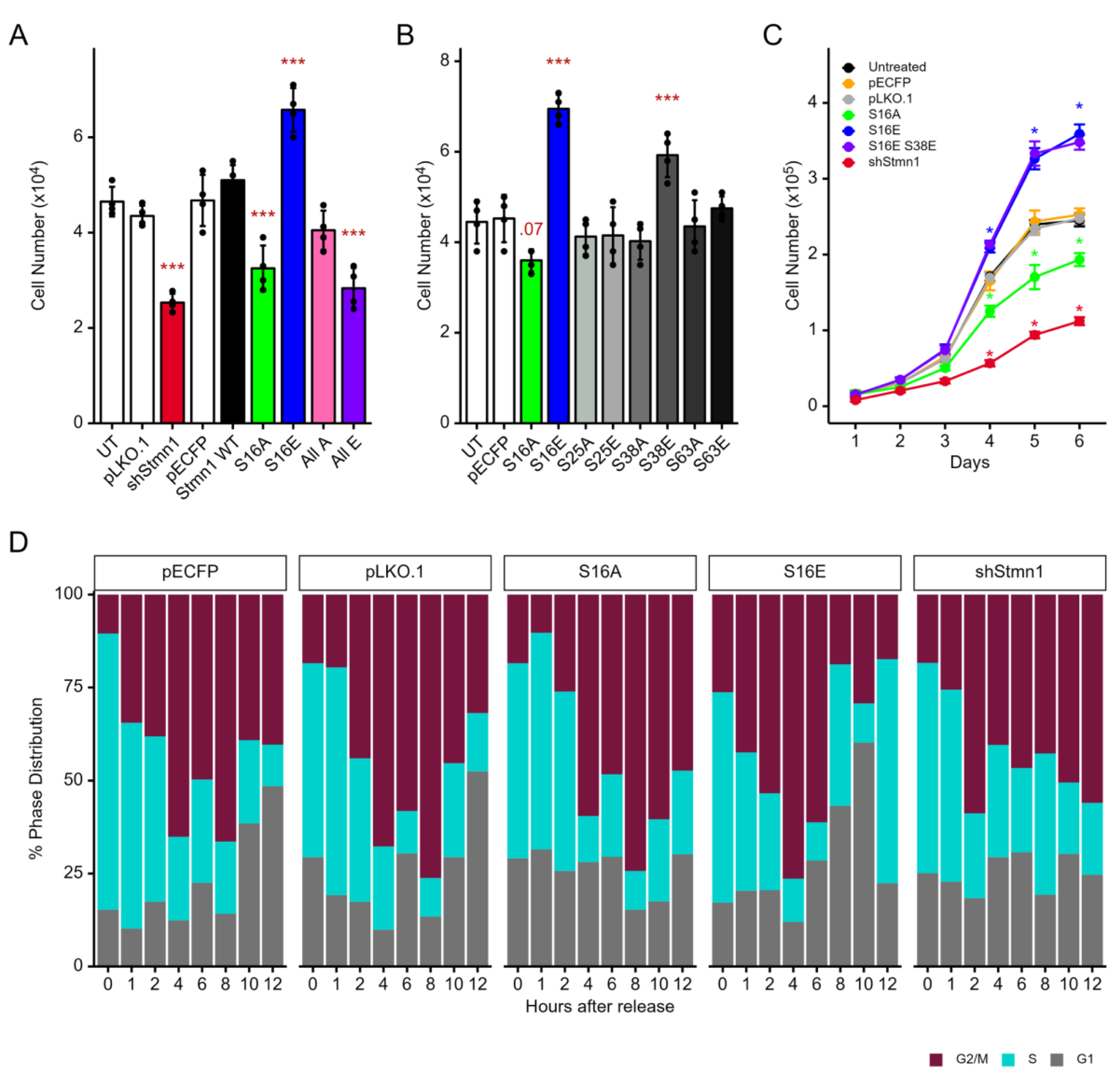

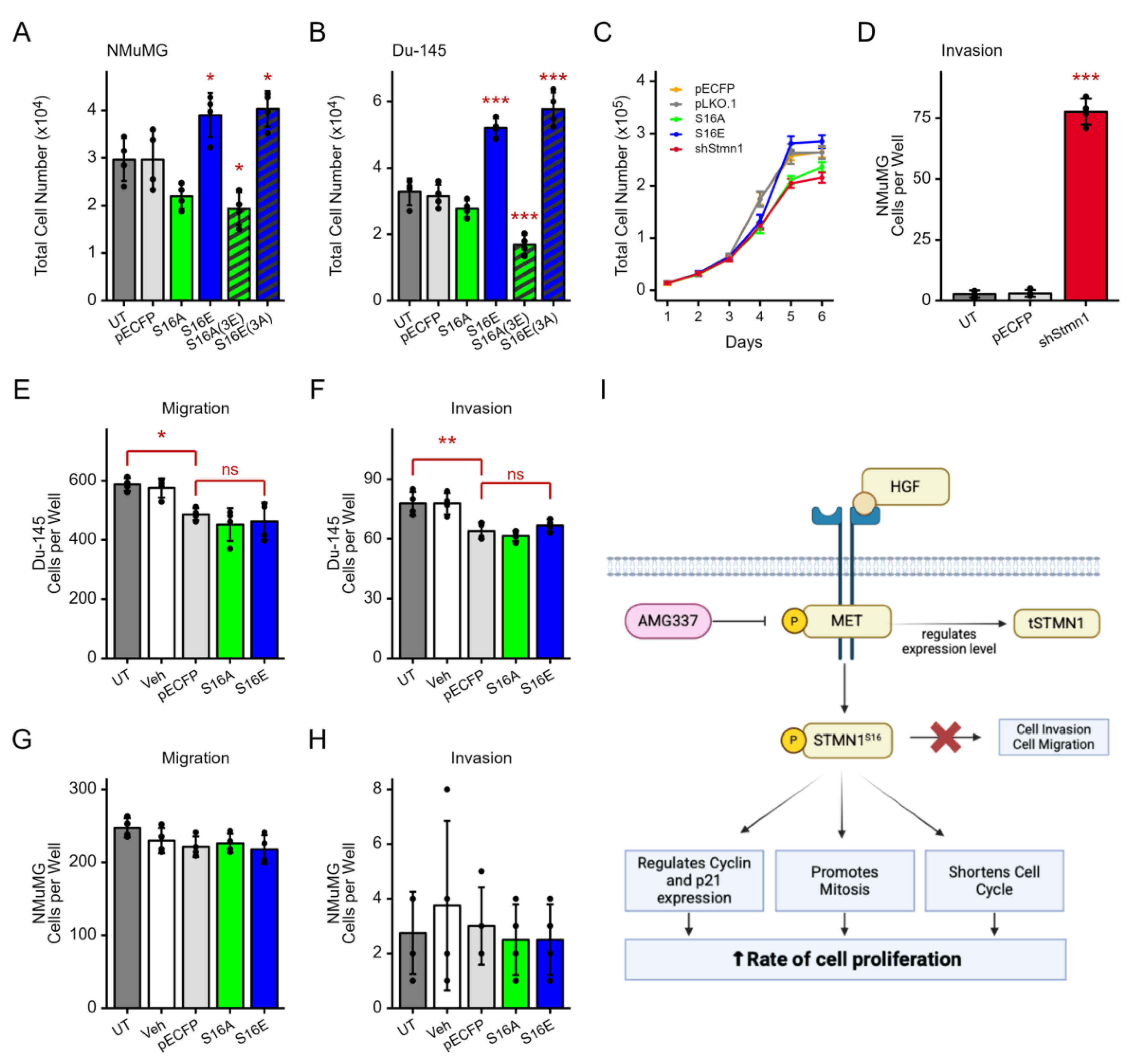

3.4. STMN1S16 Phosphorylation and Cell Proliferation Are Regulated by HGF/MET

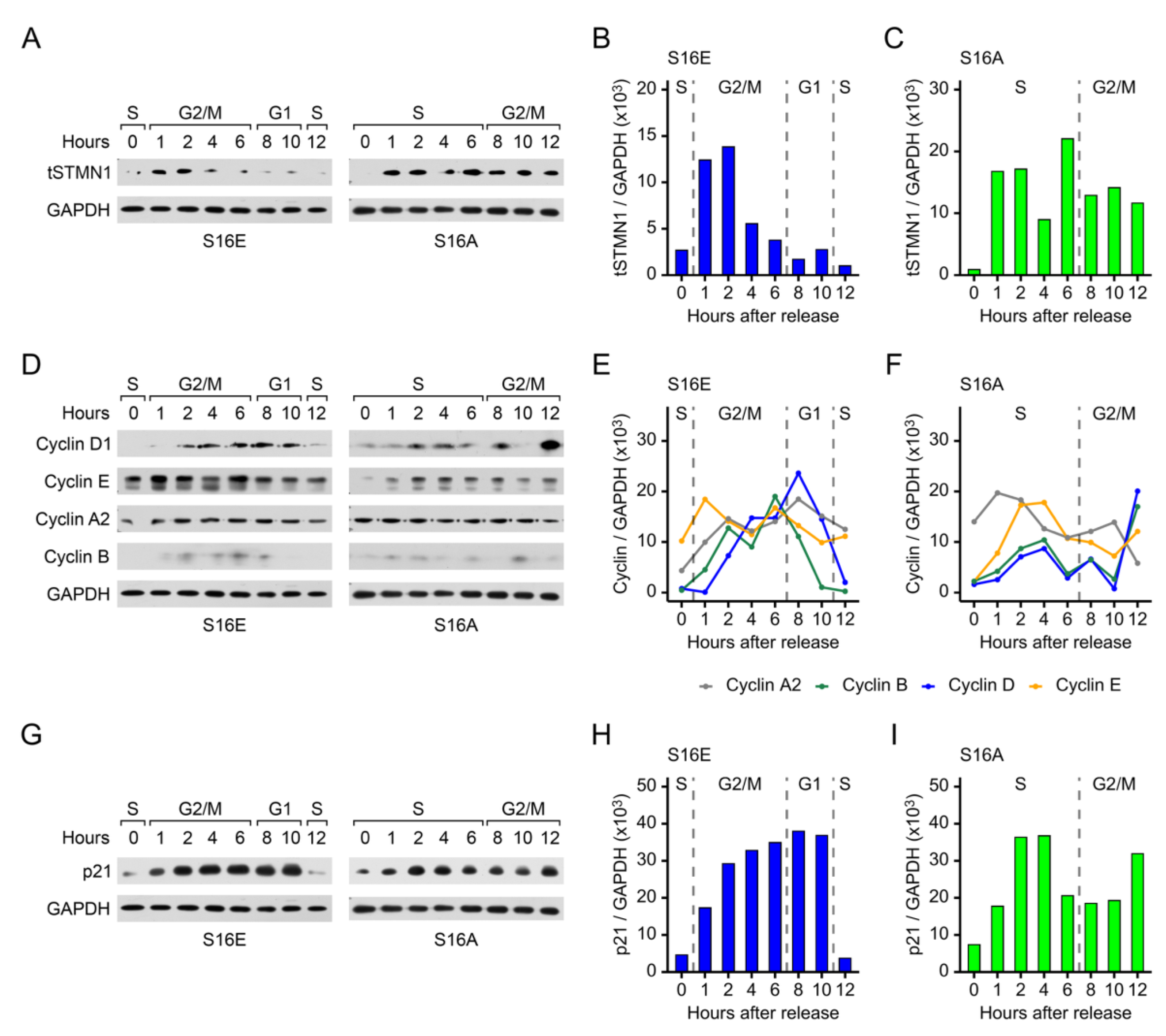

3.5. Both pSTMN1S16 and tSTMN1 Levels Are Modulated by HGF/MET During Cell Cycle Progression

3.6. Cyclins and p21 Are Concomitantly Regulated by pSTMN1S16.

3.8. STMN1S16E and STMN1S16A Modulate tSTMN1, Cyclins, and p21 Levels

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | alanine |

| ADT | androgen deprivation therapy |

| a.k.a. | a.k.a. - also known as |

| ANOVA | ANOVA - analysis of variance |

| AR | AR - androgen receptor |

| BC | BC - breast cancer |

| BPH | BPH - benign prostate hyperplasia |

| CDK1 | cyclin dependent kinase 1 |

| cDNA | copy deoxynucleic acid |

| CTX | C-terminal telopeptide |

| E | glutamic acid |

| ECL | Enhanced Chemiluminescence |

| EMT | epithelial mesenchymal transition |

| Fig | figure |

| FoxM1 | Forkhead Box M1 |

| G1/S/G0/M | phases of cell cycle |

| HGF | hepatocyte growth factor |

| m | metastatic |

| mCRPC | metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| MET | MET proto-oncogene, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase |

| p | phospho |

| p21 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A |

| P53 | tumor protein 53 |

| PCa | prostate cancer |

| pECFP | plasmid enhanced cyan fluorescent protein |

| pLKO.1/shSTMN1 | MISSION® pLKO.1-puro Non-Target shRNA control |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| STMN1 | Stathmin 1 |

| S | serine |

| sh | Short hairpin |

| Sp1 | Sp1 transcription factor |

| t | total |

| VEGFR-2 | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 |

References

- Roy, S.; Saad, F. Metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: a new horizon beyond the androgen receptors. Current opinion in supportive and palliative care 2022, 16, 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Muralidhar, A.; Potluri, H.K.; Jaiswal, T.; McNeel, D.G. Targeted Radiation and Immune Therapies-Advances and Opportunities for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.K.; Bertoli, C.; de Bruin, R.A.M. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2022, 23, 74-88. [CrossRef]

- Sumanasuriya, S.; De Bono, J. Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer-A Review of Current Therapies and Future Promise. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Baldino, N.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Catalano, A. Targeting Breast Cancer: An Overlook on Current Strategies. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yeh, Y.A.; Cheng, S.; Gu, X.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Khater, N.P.; Kasper, S.; Yu, X. Stathmin 1 expression in neuroendocrine and proliferating prostate cancer. Discov Oncol 2025, 16, 19. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Tau and stathmin proteins in breast cancer: A potential therapeutic target. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2022, 49, 445-452. [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.S.; Khuri, F.R. Mode of action of docetaxel - a basis for combination with novel anticancer agents. Cancer treatment reviews 2003, 29, 407-415. [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.K.; Kyprianou, N. Exploitation of the Androgen Receptor to Overcome Taxane Resistance in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Adv Cancer Res 2015, 127, 123-158. [CrossRef]

- Sobel, A. Stathmin: a relay phosphoprotein for multiple signal transduction? Trends Biochem Sci 1991, 16, 301-305.

- Cassimeris, L. The oncoprotein 18/stathmin family of microtubule destabilizers. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002, 14, 18-24.

- Beretta, L.; Dobransky, T.; Sobel, A. Multiple phosphorylation of stathmin. Identification of four sites phosphorylated in intact cells and in vitro by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and p34cdc2. J Biol Chem 1993, 268, 20076-20084.

- Rubin, C.I.; Atweh, G.F. The role of stathmin in the regulation of the cell cycle. J Cell Biochem 2004, 93, 242-250.

- Machado-Neto, J.A.; Rodrigues Alves, A.P.N.; Fernandes, J.C.; Coelho-Silva, J.L.; Scopim-Ribeiro, R.; Fenerich, B.A.; da Silva, F.B.; Scheucher, P.S.; Simoes, B.P.; Rego, E.M.; et al. Paclitaxel induces Stathmin 1 phosphorylation, microtubule stability and apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00405. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, T.; Song, X.; Tian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Yang, X. Siva 1 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion by phosphorylating Stathmin in ovarian cancer cells. Oncology letters 2017, 14, 1512-1518. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Deng, W.W.; Yang, L.L.; Zhang, W.F.; Sun, Z.J. Expression and phosphorylation of Stathmin 1 indicate poor survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and associate with immune suppression. Biomark Med 2018, 12, 759-769. [CrossRef]

- Wik, E.; Birkeland, E.; Trovik, J.; Werner, H.M.; Hoivik, E.A.; Mjos, S.; Krakstad, C.; Kusonmano, K.; Mauland, K.; Stefansson, I.M.; et al. High phospho-Stathmin(Serine38) expression identifies aggressive endometrial cancer and suggests an association with PI3K inhibition. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2013, 19, 2331-2341. [CrossRef]

- Jurmeister, S.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Sandi, C.; Pertega-Gomes, N.; Wadhwa, K.; Lamb, A.D.; Dunning, M.J.; Attig, J.; Carroll, J.S.; Fryer, L.G.; et al. Identification of potential therapeutic targets in prostate cancer through a cross-species approach. EMBO Mol Med 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jiang, P.; Du, W.; Wu, Z.; Li, C.; Qiao, M.; Yang, X.; Wu, M. Siva1 suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of tumor cells by inhibiting stathmin and stabilizing microtubules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011, 108, 12851-12856.

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, S.; Shen, F.; Long, D.; Yu, T.; Wu, M.; Lin, X. In vitro neutralization of autocrine IL-10 affects Op18/stathmin signaling in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2019, 41, 501-511. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, W.; Tang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xue, Y.; Hu, J.; Lin, D. PRL-3 exerts oncogenic functions in myeloid leukemia cells via aberrant dephosphorylation of stathmin and activation of STAT3 signaling. Aging (Albany NY) 2019, 11, 7817-7829. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liao, Y.; Long, D.; Yu, T.; Shen, F.; Lin, X. The Cdc2/Cdk1 inhibitor, purvalanol A, enhances the cytotoxic effects of taxol through Op18/stathmin in non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro. Int J Mol Med 2017, 40, 235-242. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, K. Membrane transport of WAVE2 and lamellipodia formation require Pak1 that mediates phosphorylation and recruitment of stathmin/Op18 to Pak1-WAVE2-kinesin complex. Cell Signal 2009, 21, 695-703. [CrossRef]

- Sahai, E.; Astsaturov, I.; Cukierman, E.; DeNardo, D.G.; Egeblad, M.; Evans, R.M.; Fearon, D.; Greten, F.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Hunter, T.; et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nature reviews. Cancer 2020, 20, 174-186. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, P.A.; Zhu, X.; Zarnegar, R.; Swanson, P.E.; Ratliff, T.L.; Vollmer, R.T.; Day, M.L. Hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor (c-MET) in prostatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1995, 147, 386-396.

- Hass, R.; Jennek, S.; Yang, Y.; Friedrich, K. c-Met expression and activity in urogenital cancers - novel aspects of signal transduction and medical implications. Cell Commun Signal 2017, 15, 10. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, B.S.; Edlund, M. Prostate cancer and the met hepatocyte growth factor receptor. Adv Cancer Res 2004, 91, 31-67. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, B.S.; Gmyrek, G.A.; Inra, J.; Scherr, D.S.; Vaughan, E.D.; Nanus, D.M.; Kattan, M.W.; Gerald, W.L.; Vande Woude, G.F. High expression of the Met receptor in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Urology 2002, 60, 1113-1117. [CrossRef]

- Varkaris, A.; Corn, P.G.; Gaur, S.; Dayyani, F.; Logothetis, C.J.; Gallick, G.E. The role of HGF/c-Met signaling in prostate cancer progression and c-Met inhibitors in clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011, 20, 1677-1684. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Lu, W.; Liu, S.; Yang, Q.; Carver, B.S.; Li, E.; Wang, Y.; Fazli, L.; Gleave, M.; Chen, Z. Crosstalk between nuclear MET and SOX9/beta-catenin correlates with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol 2014, 28, 1629-1639. [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, P.A.; Halabi, S.; Picus, J.; Sanford, B.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Small, E.J.; Kantoff, P.W. Prognostic significance of plasma scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor levels in patients with metastatic hormone- refractory prostate cancer: results from cancer and leukemia group B 150005/9480. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2006, 4, 269-274. [CrossRef]

- Aftab, D.T.; McDonald, D.M. MET and VEGF: synergistic targets in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 2011, 13, 703-709. [CrossRef]

- Raghav, K.P.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Chavez-MacGregor, M.; Meng, X.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Mills, G.B.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Blumenschein, G.R., Jr.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M. cMET and phospho-cMET protein levels in breast cancers and survival outcomes. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2012, 18, 2269-2277. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, C.; Cui, S. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor in breast cancer and its effect on prognosis and sensitivity to chemotherapy. Molecular medicine reports 2015, 11, 1037-1042. [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer discovery 2012, 2, 401-404. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Aksoy, B.A.; Dogrusoz, U.; Dresdner, G.; Gross, B.; Sumer, S.O.; Sun, Y.; Jacobsen, A.; Sinha, R.; Larsson, E.; et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Science signaling 2013, 6, pl1. [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Wu, B.; Jin, K.; Chen, Y. Beyond boundaries: unraveling innovative approaches to combat bone-metastatic cancers. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1260491. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Coleman, I.; Morrissey, C.; Zhang, X.; True, L.D.; Gulati, R.; Etzioni, R.; Bolouri, H.; Montgomery, B.; White, T.; et al. Substantial interindividual and limited intraindividual genomic diversity among tumors from men with metastatic prostate cancer. Nature medicine 2016, 22, 369-378. [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Cyrta, J.; Heller, G.; Prandi, D.; Armenia, J.; Coleman, I.; Cieslik, M.; Benelli, M.; Robinson, D.; Van Allen, E.M.; et al. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2019, 116, 11428-11436. [CrossRef]

- Stopsack, K.H.; Nandakumar, S.; Wibmer, A.G.; Haywood, S.; Weg, E.S.; Barnett, E.S.; Kim, C.J.; Carbone, E.A.; Vasselman, S.E.; Nguyen, B.; et al. Oncogenic Genomic Alterations, Clinical Phenotypes, and Outcomes in Metastatic Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2020, 26, 3230-3238. [CrossRef]

- .

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2016.

- Fekete, J.T.; Gyorffy, B. ROCplot.org: Validating predictive biomarkers of chemotherapy/hormonal therapy/anti-HER2 therapy using transcriptomic data of 3,104 breast cancer patients. International journal of cancer 2019, 145, 3140-3151. [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Ghosh, R.; Vummidi Giridhar, P.; Gu, G.; Case, T.; SM, B.; Kasper, S. Inhibition of Stathmin1 Accelerates the Metastatic Process Cancer research 2012, 72, 5407-5417, doi:doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1158. .

- Ghosh, R.; Gu, G.; Tillman, E.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Fazli, L.; Rennie, P.S.; Kasper, S. Increased expression and differential phosphorylation of stathmin may promote prostate cancer progression. The Prostate 2007, 67, 1038-1052.

- Wang, R.C.; Wang, Z. Synchronization of Cultured Cells to G1, S, G2, and M Phases by Double Thymidine Block. Methods in molecular biology 2022, 2579, 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Wee, P.; Wang, Z. Cell Cycle Synchronization of HeLa Cells to Assay EGFR Pathway Activation. Methods in molecular biology 2017, 1652, 167-181. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Akbani, R.; Ju, Z.; Roebuck, P.L.; Liu, W.; Yang, J.Y.; Broom, B.M.; Verhaak, R.G.; Kane, D.W.; et al. TCPA: a resource for cancer functional proteomics data. Nature methods 2013, 10, 1046-1047. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Akbani, R.; Zhao, W.; Lu, Y.; Weinstein, J.N.; Mills, G.B.; Liang, H. Explore, Visualize, and Analyze Functional Cancer Proteomic Data Using the Cancer Proteome Atlas. Cancer research 2017, 77, e51-e54. [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Karaszewska, B.; Kang, Y.K.; Chung, H.C.; Shankaran, V.; Siena, S.; Go, N.F.; Yang, H.; Schupp, M.; Cunningham, D. A Multicenter Phase II Study of AMG 337 in Patients with MET-Amplified Gastric/Gastroesophageal Junction/Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Other MET-Amplified Solid Tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2019, 25, 2414-2423. [CrossRef]

- le Gouvello, S.; Manceau, V.; Sobel, A. Serine 16 of stathmin as a cytosolic target for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II after CD2 triggering of human T lymphocytes. Journal of immunology 1998, 161, 1113-1122.

- Gradin, H.M.; Marklund, U.; Larsson, N.; Chatila, T.A.; Gullberg, M. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV Gr-dependent phosphorylation of oncoprotein 18. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 3459-3467, doi:Doi 10.1128/Mcb.17.6.3459.

- Chen, G.; Deng, X. Cell Synchronization by Double Thymidine Block. Bio Protoc 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Belletti, B.; Baldassarre, G. Stathmin: a protein with many tasks. New biomarker and potential target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2011, 15, 1249-1266. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Lin, S.J.; Tsai, S.C.; Lin, J.H.; Chen, M.R.; Wang, J.T.; Lee, C.P.; Tsai, C.H. Regulation of microtubule dynamics through phosphorylation on stathmin by Epstein-Barr virus kinase BGLF4. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 10053-10063. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Dutta, A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nature reviews. Cancer 2009, 9, 400-414. [CrossRef]

- Ghule, P.N.; Seward, D.J.; Fritz, A.J.; Boyd, J.R.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Lian, J.B.; Stein, J.L.; Stein, G.S. Higher order genomic organization and regulatory compartmentalization for cell cycle control at the G1/S-phase transition. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 6406-6413. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hitomi, M.; Stacey, D.W. Variations in cyclin D1 levels through the cell cycle determine the proliferative fate of a cell. Cell Div 2006, 1, 32. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Aakre, M.E.; Gorska, A.E.; Price, J.O.; Eltom, S.E.; Pietenpol, J.A.; Moses, H.L. Induction by transforming growth factor-beta1 of epithelial to mesenchymal transition is a rare event in vitro. Breast Cancer Res 2004, 6, R215-231.

- Accornero, P.; Miretti, S.; Bersani, F.; Quaglino, E.; Martignani, E.; Baratta, M. Met receptor acts uniquely for survival and morphogenesis of EGFR-dependent normal mammary epithelial and cancer cells. PloS one 2012, 7, e44982. [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Pu, Y.; Smith, J.; Gao, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, B. Identifying metastatic ability of prostate cancer cell lines using native fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning methods. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 2282. [CrossRef]

- Nafissi, N.N.; Kosiorek, H.E.; Butterfield, R.J.; Moore, C.; Ho, T.; Singh, P.; Bryce, A.H. Evolving Natural History of Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cureus 2020, 12, e11484. [CrossRef]

- Gandaglia, G.; Abdollah, F.; Schiffmann, J.; Trudeau, V.; Shariat, S.F.; Kim, S.P.; Perrotte, P.; Montorsi, F.; Briganti, A.; Trinh, Q.D.; et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: A population-based analysis. The Prostate 2014, 74, 210-216. [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wheeler, S.E.; Clark, A.M.; Whaley, D.L.; Yang, M.; Wells, A. Liver protects metastatic prostate cancer from induced death by activating E-cadherin signaling. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1725-1742. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.J.; Shore, N.D.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; Petrylak, D.P.; Holzbeierlein, J.; Villers, A.; Azad, A.; Alcaraz, A.; Alekseev, B.; Iguchi, T.; et al. Efficacy of Enzalutamide plus Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer by Pattern of Metastatic Spread: ARCHES Post Hoc Analyses. The Journal of urology 2021, 205, 1361-1371. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, S.Y.; Huang, S.F.; Yu, M.C.; Yeh, T.S.; Chen, T.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Chang, C.J.; Sung, C.M.; Lee, Y.L.; Hsu, C.Y. Stathmin1 overexpression associated with polyploidy, tumor-cell invasion, early recurrence, and poor prognosis in human hepatoma. Molecular carcinogenesis 2010, 49, 476-487. [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Xu, M.D.; Gan, L.; Huang, H.; Xiu, Q.; Li, B. Overexpression of stathmin 1 is a poor prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology 2015, 95, 56-64. [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, Y.R.; Zheng, Y.Z.; Ling, H.; Qiao, F.; Li, S.; Hu, X.; Shao, Z.M. Stathmin and phospho-stathmin protein signature is associated with survival outcomes of breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 22227-22238. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, I.; Casimiro, M.C.; Wang, C.; Rosenberg, A.L.; Quong, J.; Minkeu, A.; Allen, K.G.; Danilo, C.; Sotgia, F.; Bonuccelli, G.; et al. Human breast cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) show caveolin-1 downregulation and RB tumor suppressor functional inactivation: Implications for the response to hormonal therapy. Cancer Biol Ther 2008, 7, 1212-1225. [CrossRef]

- Askeland, C.; Wik, E.; Finne, K.; Birkeland, E.; Arnes, J.B.; Collett, K.; Knutsvik, G.; Kruger, K.; Davidsen, B.; Aas, T.; et al. Stathmin expression associates with vascular and immune responses in aggressive breast cancer subgroups. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 2914. [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, K.N. Microtubule-targeted anticancer agents and apoptosis. Oncogene 2003, 22, 9075-9086. [CrossRef]

- Kaposi-Novak, P.; Lee, J.S.; Gomez-Quiroz, L.; Coulouarn, C.; Factor, V.M.; Thorgeirsson, S.S. Met-regulated expression signature defines a subset of human hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype. The Journal of clinical investigation 2006, 116, 1582-1595. [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.R.; Park, H.J.; Wang, Z.; Kiefer, M.M.; Raychaudhuri, P. FoxM1 mediates resistance to herceptin and paclitaxel. Cancer research 2010, 70, 5054-5063. [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Ehemann, V.; Brauckhoff, A.; Keith, M.; Vreden, S.; Schirmacher, P.; Breuhahn, K. Protumorigenic overexpression of stathmin/Op18 by gain-of-function mutation in p53 in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology 2007, 46, 759-768. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Uen, Y.H.; Li, C.F.; Horng, K.C.; Chen, L.R.; Wu, W.R.; Tseng, H.Y.; Huang, H.Y.; Wu, L.C.; Shiue, Y.L. The E2F transcription factor 1 transactives stathmin 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2013, 20, 4041-4054. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammaren, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nature communications 2023, 14, 201. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, N.; Marklund, U.; Gradin, H.M.; Brattsand, G.; Gullberg, M. Control of microtubule dynamics by oncoprotein 18: dissection of the regulatory role of multisite phosphorylation during mitosis. Mol Cell Biol 1997, 17, 5530-5539.

- Tian, X.; Tian, Y.; Moldobaeva, N.; Sarich, N.; Birukova, A.A. Microtubule dynamics control HGF-induced lung endothelial barrier enhancement. PloS one 2014, 9, e105912. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S.; Safferling, K.; Westphal, K.; Hrabowski, M.; Muller, U.; Angel, P.; Wiechert, L.; Ehemann, V.; Muller, B.; Holland-Cunz, S.; et al. Stathmin regulates keratinocyte proliferation and migration during cutaneous regeneration. PloS one 2013, 8, e75075. [CrossRef]

- Alesi, G.N.; Jin, L.; Li, D.; Magliocca, K.R.; Kang, Y.; Chen, Z.G.; Shin, D.M.; Khuri, F.R.; Kang, S. RSK2 signals through stathmin to promote microtubule dynamics and tumor metastasis. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5412-5421. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.C.; Smith, M.R.; Sweeney, C.; Elfiky, A.A.; Logothetis, C.; Corn, P.G.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Small, E.J.; Harzstark, A.L.; Gordon, M.S.; et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced prostate cancer: results of a phase II randomized discontinuation trial. J Clin Oncol 2013, 31, 412-419. [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; De Bono, J.; Sternberg, C.; Le Moulec, S.; Oudard, S.; De Giorgi, U.; Krainer, M.; Bergman, A.; Hoelzer, W.; De Wit, R.; et al. Phase III Study of Cabozantinib in Previously Treated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: COMET-1. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 3005-3013. [CrossRef]

- Verras, M.; Lee, J.; Xue, H.; Li, T.H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. The androgen receptor negatively regulates the expression of c-Met: implications for a novel mechanism of prostate cancer progression. Cancer research 2007, 67, 967-975. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Feng, F.Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, X.; Han, S.; Wilder-Romans, K.; Navone, N.M.; Logothetis, C.; Taichman, R.S.; Keller, E.T.; et al. Mechanistic Support for Combined MET and AR Blockade in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Supko, J.G.; Gray, K.P.; Melnick, Z.J.; Regan, M.M.; Taplin, M.E.; Choudhury, A.D.; Pomerantz, M.M.; Bellmunt, J.; Yu, C.; et al. Dual Blockade of c-MET and the Androgen Receptor in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: A Phase I Study of Concurrent Enzalutamide and Crizotinib. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2020, 26, 6122-6131. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Cun, X.; Ruan, S.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.; Kuang, Q.; Hu, C.; Xiao, W.; He, Q.; Gao, H. Utilizing G2/M retention effect to enhance tumor accumulation of active targeting nanoparticles. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 27669. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).