1. Introduction

Land is a limited resource in most countries, necessitating efficient utilization to ensure adequate food security[

1]. To achieve this, national policies must prioritize the optimal allocation of scarce resources, including arable land, water, and fertilizers, as these are critical for maximizing agricultural output and, consequently, enhancing food security. Furthermore, effective land use is integral to fulfilling the four dimensions of food security, which are availability, access, utilization, and stability. In South Africa, however, deficiencies persist across these dimensions due to historical injustices, economic disparities, and environmental challenges. Despite the country’s national food surplus, inequitable land distribution, limited access to agricultural resources, and systemic instability perpetuate food insecurity for a significant portion of the population. Addressing structural inequities in land ownership and strengthening agricultural resilience are thus essential steps toward achieving sustainable food security in South Africa.

Food security is attained when everyone, at any time, has physical, social and economic access to healthy and nutritious food that meets their nutritional needs for an active and healthy life[

2]. Under normal circumstances, food security is directly linked to efficient use of available resources[

3]. Countries with large populations such as India and China always strive to balance food security and other basic human needs, such as building roads, dams, and housing[

4]. These countries provide plausible examples of how to efficiently use land to attain food security. In doing this, these countries employ a combination of technological advances and investment in trying to produce enough food for their citizens[

5] The main goal of these countries is to obtain maximum yield from limited resources, including soil, water, and other nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and solar radiation’[

6]. Solar radiation is essential for plants to break down and produce nutrients that are later consumed by humans as part of their diet[

7].

Food security is one of the main targets of the Constitution of South Africa. To safeguard families from food insecurity and poverty, South Africa has implemented various programs and interventions, such as social security grants, child support grants, school feeding schemes, farmer support programs (such as CASP = comprehensive agricultural support programme), and many others. All of these seek to achieve a reasonable level of food security for the country and individual households. The National Food and Nutrition Policy and National Food and Nutrition Security Strategy have also been developed and adopted by the South African government to protect households from shocks and food insecurity. These are also intended to ensure that all families in South Africa have access to a variety of food from different sources, such as formal and informal markets.

Despite South Africa's strong legislative, constitutional, and regulatory framework for food security and nutrition, a large segment of the population struggles with food insecurity and malnutrition. This is despite South Africa being recognized as one of the most food-secure countries[

8].

The double burden of malnutrition, manifested in stunting, wasting, and obesity, distinguishes South Africa's malnutrition from that of other countries. In South Africa, where there are 65 million people, food security should not be an issue because of the country's population, land size, and ability to produce enough food for both export and domestic consumption. This indicates that South Africa needs to consider different ways of effectively utilizing land and other resources to improve its food security, especially among households.

Due to the economic hardships brought on by a combination of declining agricultural activity, high unemployment rates, and climate change linked floods, households in South Africa struggle to afford food. As a result, many families' diets, especially those of lower socioeconomic status have become less nutrient-dense. These observations led to an evaluation of South Africa's food security as presented in this paper. This being motivated by the fact that the Department of Agriculture has initiated various programs and interventions aimed at improving food security on both household and national scales. However, despite these initiatives, only limited progress has been noted as households continues to struggle with food insecurity.

Food is necessary for survival. The paper argues that a country’s capacity to feed its people depends on how it uses its finite amount of land and other resources. Based on information gathered from households during the National Food and Nutrition Security Survey (NFNSS) of South Africa, this paper highlights the vulnerability of households to hunger and food insecurity. The NFNSS examined the level of food insecurity in households, as well as the efficiency of land use in South Africa. A total of 100 indicators were evaluated. Hence, only household access to land, land tenure, household food production, and other agricultural activities, as well as household capacity for resilience to food shocks and scarcity, are discussed in this paper.

2. Literature Review

The achievement of food security and eradication of hunger are highly valued by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals[

9]. In an era of rapid population growth and rising pressure on agricultural systems to provide sufficient food, Ahmad and Dar10 contended that effective resource use is crucial for both food security and eco-efficient agricultural practices. The practice of increasing agricultural output while using less land, water, nutrients, energy, labor, or capital is known as eco-efficiency10. According to Ahmad and Dar[

10], "endogenous inputs" must be considered if the nation wishes to increase food production using existing land if one wants to use land effectively for food security. As mentioned in the literature, factors other than land are involved in the optimal usage of available resources for agricultural production[

11].

It is well known that South Africa has huge landmasses but limited water resources[

12]. It is one of the driest countries in the world. Some authors predict that as early as 2025, global water demand will increase by 60 %. This suggests that for South Africa to achieve the required levels of food security, it must utilize land and water resources effectively. Ahmad and Dar[

10] advocates for precision farming as a means to achieve this. The capacity to maximize yields while using the least amount of fertilizer and other inputs possible, while maintaining a sustainable environment, is why precision farming has become increasingly popular. It entails the process of adjusting the inputs and procedures with more precision to adjust to the local prevalent conditions for maximizing outputs with minimal input consumption. This process consists of three fundamental steps:

- a)

collecting variability,

- b)

assessing variability,

- c)

and decision-making

This method seeks to promote livelihoods by preventing land degradation, resource depletion, and environmental damage. This idea can be used in other agricultural specialties as well as in animal husbandry. Utilizing additional efficiency-enhancing technologies is part of precision farming. These include the global positioning system, geographical information system, remote sensing, variable-rate application, Internet of Things, and robotics.

In addition to these technical advancements, it has been noted in a number of academic publications that high-tech advancements, such as nanotechnology, can also maximize the utilization of land for high agricultural yield. Many issues faced in agriculture and other related industries can be addressed through nanotechnology as a new instrument[

13]. Owing to the overuse of pesticides and fertilizers, which have a negative impact on the environment, organisms such as bacteria are developing resistance to technological interventions such as pesticides, which also alter the health and potency of the soil[

14]. Because bioactive substances are encapsulated and released at a controlled rate, nanoscience seem to be able to address these concerns.

Punia et al [

15] has added a perspective on the significance of radiation as a resource that crops must be able to use effectively in order to achieve the required yields and directly improve the amount of food that is available for consumption per person. This viewpoint joins other well-known interventions listed in the literature such as Aranda, Pardos, Puértolas, Jiménez and Pardos[16[, [

17], [

1]8, [

19]. Many of the most basic plant growth models have been created to imitate the process of photosynthesis enhancement or the transformation of light energy and carbon dioxide into plant biomass[

20],[

21]. Utilization of radiation consumption efficiency is one of these factors[

22]. The amount of carbon dioxide that the leaf can absorb and the sun's electromagnetic radiation have the greatest effects on the growth rate of each plant[

23]

In South Africa, the effects of climate change on crops, other elements of the ecosystem, and agricultural yield have been well documented. Various options for enhancing agricultural outputs have been presented in different studies on how to incorporate advanced approaches as a way of improving efficiency while mitigating the impacts of climate change[

24].

Of interesting observation by some authors is that crop yields have been shown to have increased two to three times in the past as a result of the usage of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers in agricultural production to meet the rising demands of a growing world population[

25]. In addition to radiation, nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) are two more crucial macronutrients for plant growth and development26 These two nutrients constitute the majority of fertilizer consumption and production in the agricultural sector. N and P endure significant losses as a result of fixation, leaching, and volatilization, and are employed in a number of applications. Numerous strategies, such as split application, coating, and use of nitrification inhibitors to reduce losses, have been devised to address this issue.

The addition of organic amendments, such as nitrogen to the soil, helps to keep the level of nitrogen in the soil stable for a longer time. Phosphatic fertilizers with an acidic residual impact are also desirable in alkaline soils. Other popular techniques for enhancing soil fertility include the use of coated fertilizers, slow-release phosphorus fertilizer modulation, and the solubilization of native phosphorus. In this context, plant growth promoting rhizobacteria should be used to ensure sustainable nitrogen and phosphorus availability, absorption, and utilization by plants.

From this literature review, it can be deduced that the state of food security in South Africa needs to be assessed in the context of the existing land and technological interventions that are within households' reach, especially in light of the growing artificial inputs used by countries such as China to increase the productivity of available land[

26]. In this literature review, various interventions, mostly technological, used to enhance and retain the productivity of available land have been discussed.

3. Materials and Methods

Assessment of the State of Household Food Security in South Africa

We conducted a large-scale national food and nutrition security survey to assess the state of household food security in South Africa. This was started in 2020 and concluded in 2022. The survey was conducted in all nine provinces of South Africa. The formulated objectives of the survey were as follows:

- a)

To provide a baseline assessment of food and nutrition security situations in households in the respective livelihood zones of nine provinces of South Africa.

- b)

To analyze the link between food security and nutrition. Explore reasons for people’s vulnerability.

- c)

Determine recommendations for planning and targeting food and nutrition security interventions.

- d)

To assess the impact of COVID-19 on food security and nutrition at the household level in South Africa.

- e)

To assess the impact of Floods and Drought on food security and nutrition at household level in KZN and Eastern Cape

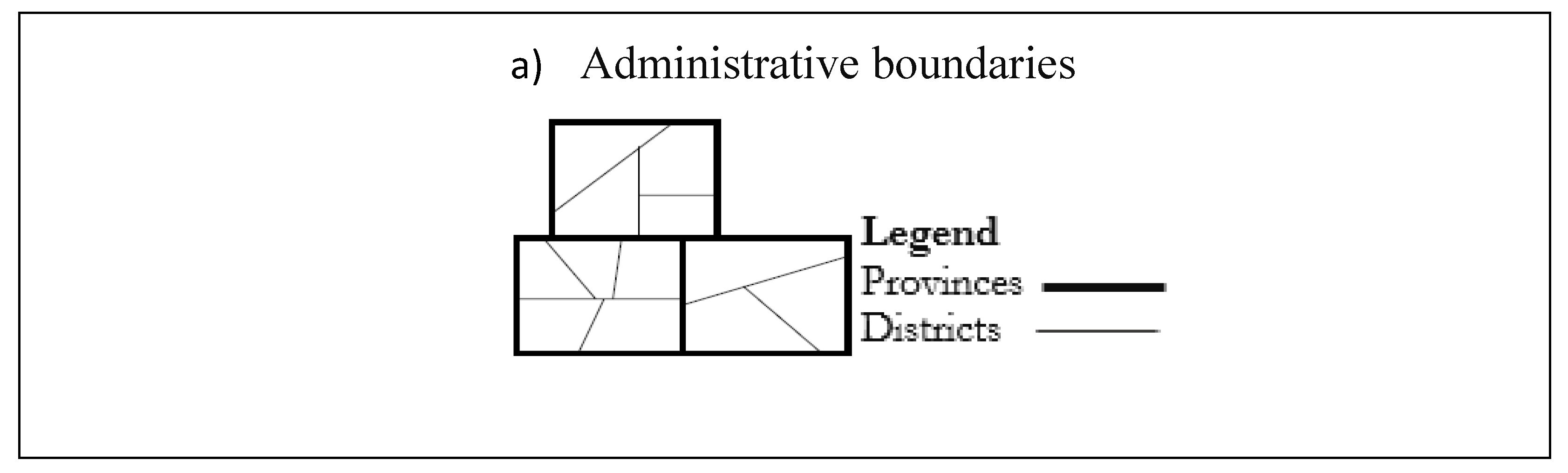

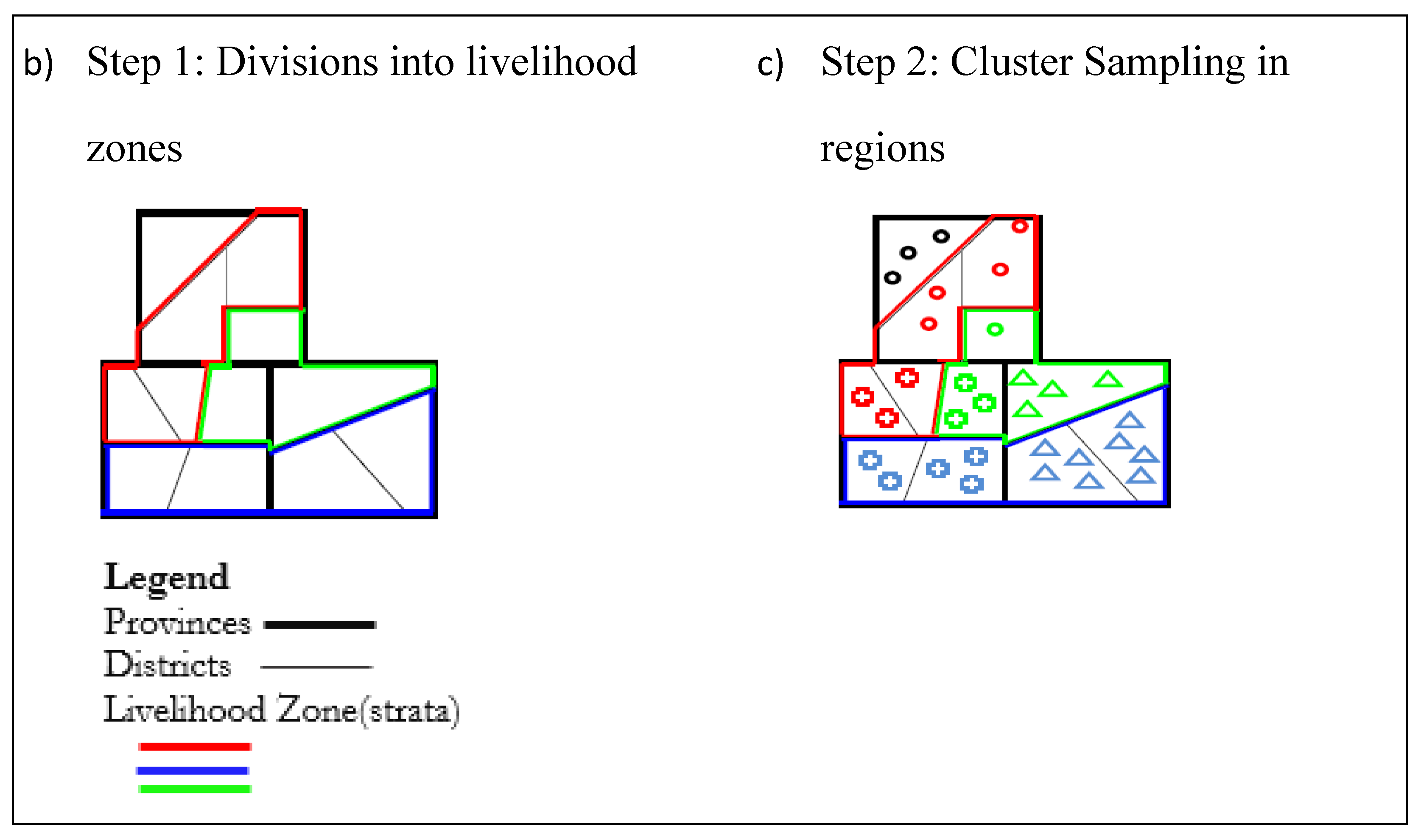

Design of the Study and Sampling

The study design was cross-sectional. It sought to provide representative and precise information at the household level. It comprised two sampling stages. The first stage was the selection of Small Area Layers (SAL) composed of a collection of households (

Figure 1). This was performed using the Probability Proportional to Size. The second stage was a simple random selection of households within each selected small-area layer (

Figure 1). In each small-area layer, a total of 35 households were randomly selected using the Global Positioning System.

The approach is based on the World Food Program Technical Guideline, which defines a cluster based on SALs, cluster size, or the number of household survey teams that can visit successfully in one day, and the number of clusters with the number of households in each indicator, typically, 20–30 clusters per stratum are typical for most assessments.

Determination of the Geographical Strata for Household Sampling

Often, food security and nutrition indicators per geographical area (e.g., district) are used as the basis for drawing the sample for the study. However, food and nutrition insecurity may vary across countries given the heterogeneity of livelihood zones. Administratively, each province has a variable number of districts in which the households are located. They obtain services through municipalities that operate at a level below the district (

Figure 2).

Stratification by administrative boundary and livelihood zones serves two function

- i.

First, administrative boundaries rarely correspond with household characteristics related to food insecurity; thus, estimates for administrative aggregations are likely to mask meaningful differences between subgroups.

- ii.

Second, defining subgroups for stratification using criteria related to vulnerability or food insecurity improves the precision of both subgroups and overall food security estimates.

For district-level estimates, the strata of investigation were the districts, with SALs distributed across livelihood zones within districts (

Figure 1). Given the constraints imposed by time and financial resources, the focus of the survey was restricted to district strata.

Data acquisition from Households

Before the data-gathering process began, a fieldworker operational manual was created. The manual specifies the methods and processes used to collect information from households. The survey targets for participation were the head of the family, primary caregiver, and children in each household. The data collection selection criteria served as a guide for participation. The conditions for inclusion and exclusion in the survey were outlined according to these criteria. For instance, people with mental instability were not included in the survey.

4. Results

Using Research Electronic Data Capturing (REDCAP) technology, a quantitative survey questionnaire was incorporated into one form with 100 variables to be investigated. REDCAP was preferred because it enables data collection in areas with spotty or no internet connectivity. REDCAP-loaded tablets were then used to perform computer-assisted personal interviews to electronically record and collect responses from the participants. Every day, when all questionnaires were completed, real-time transmission of data was sent to the main database. The received data were then cleaned, scraped, and mined. Logical coherence, dependency on the derived variables, and filter instructions were assessed and validated to ensure that the data were of acceptable quality.

After quality assurance has been completed, descriptive statistical analyses were performed. Cross-tabulations, prevalence, and response proportion estimates were determined using the Stata and SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) statistical software. Through weighted analysis, it was concluded that the estimates of the food and nutrition variables were representative of the overall population of the provinces of South Africa. When analyzing the data, the complex multi-level sample design was taken into account, and where non-responses were identified, they were modified accordingly.

Profiles of the Households from Which Data Was Obtained

As revealed by the survey, the average age of the household heads across all provinces was 54 years. More than half of household heads (53.8%) were females. The African population accounted for 98.9% of the survey participants. Respondents aged 65 years or older accounted for 29.1% of the sample population. Youths (i.e., those between the ages of 18-34 years) constituted the lowest percentage (4.0%) of the survey population. In terms of marital status, 44.4 who were married and living together as family members.

Respondents with secondary school education accounted for 28.1% of the population, followed by those with primary school education (28.1 %). Household heads aged between 55 and 65 years constituted the highest proportion of respondents with no schooling (35.6% and 22.8%, respectively). A higher proportion (74.2%) of female household heads were unemployed than male household heads (48.6%). Among the youth, unemployment was acute among those aged 34 years or younger ( 60.3% and 87.7%, respectively).

Access to Land by Households

A dual system of land rights defines households’ access to land in South Africa. This includes a constitutionally protected statute law, largely patrilineal tribal traditions, and custom-based customary law. This distribution across the country is such that in the Free State Province, the highest access to land by households is in the Lejelweputswa (89.7%) and Fezile Dabi (86.5%) districts. The largest portion of privately owned land is located in the district of Xhariep.

In the Gauteng Province, households have limited access to land. Only 50 percent of households have access to land. This is due to the fact that Gauteng is the densely populated province of South Africa. Consequently, most of the land in the province is privately owned.

In most rural areas of Limpopo, access to land is based on the customary law. What has been deduced from the National Food and Nutrition Security Survey is that compared to private land, tribal land is cheap and accessible.

In the Northwest Province, access to land is often between families. At least 65% of households in the three districts of the province had access to adequate land. Only Dr. Kenneth Kaunda had the lowest number of households with access to land (47%).

In Northern Cape Province, few families have access to land. John Taolo Galeshewe district is the only district with a slightly higher percentage of households with access to land. Within the province, ZF Mgcawu had the lowest percentage (16 %) of families with limited access to land. This may be due to the lack of tribal land in the district and the fact that the region has the highest number of outstanding claims, some of which are complex.

Only a small number of households in Western Cape Province have access to land. Overberg, Cape Winelands, and Central Karoo (29% each) have the highest percentage of households with access to land. It should be noted that most of the land in Western Cape Province is privately owned.

Families in the Mpumalanga Province have restricted access to land. Ehlanzeni District has the highest percentage of households with access to land (more than 30%). Only 25% of the population of Gert Sibande, the largest district in the region, has access to land, although the region covers approximately half of the total area (31,841 km2). This is because mining, powers stations and agriculture are the main industries in these areas

In five out of eight districts in the Eastern Cape Province, at least 60% of the households had access to land. The lowest percentage is found in the Cacadu district, where 46% of the households have access to land. Land in the Eastern Cape is primarily held under various land tenure systems. For example, most of the land in the OR Tambo area is owned by the state or tribal jurisdictions. There are various legal land rights in the area, including freehold (in rural and urban areas), occupancy rights (in rural areas), and the right to rent and graze on shared property.

In seven of the 11 districts in the province of Kwazulu-Natal, at least 60% of households had access to land. The eThekwini metropolitan district had the lowest proportion of households with land access. It should be noted that most of the land in Kwazulu-Natal Province is held under two rights: private commercial agriculture, which is the most common type of land ownership with popular use being forestry and sugar cane plantations, and tribal land, which is held on behalf of the King of the Zulus through the Ingonyama Trust.

Land Tenure

According to the 2022 National Food and Nutrition Security Survey, every household in South Africa's nine provinces owns the land on which it is located. Within the districts, there were variations in the percentage of households that owned land (Table 1). The average size of land possibly owned by households is 500 square meters, and the maximum size is typically 1000 square meters. A sizable proportion of households reside in rented or public property. This may be either private or governmental land.

| Province |

No of Districts |

Districts with Highest Percentage of land ownership |

Percentage |

| Free State |

4 |

Mangaung district |

82% |

| Thabo Mafutsanyane district |

|

| Gauteng |

5 |

Ekurhuleni district |

88% |

| Sedibeng district |

87% |

| City of Tshwane district |

83% |

| Mpumalanga |

3 |

Ehlanzeni district |

89% |

| Nkangala district |

86% |

| Limpopo |

5 |

Sekhukhune district |

95% |

| Vhembe district |

93% |

| Northern Cape |

5 |

Namakwa district |

95% |

| JTGDM district |

92% |

| Western Cape |

5 |

Overberg district |

92% |

| Eastern Cape |

6 |

Chris Hani district |

99% |

| OR Tambo district |

98% |

| KwaZulu Natal |

11 |

King Centshwayo district |

91% |

| Ilembe district |

91% |

| North West |

4 |

Bojanala district |

|

| Dr Kenneth Kaunda district |

|

| Dr Ruth Mompati district |

82% |

The amount of land that can be used for agricultural production is minimal to non-existent because of the small proportion of land owned by households. The largest percentage of larger land that can be owned by households is found in the TBVC (Transkei, Boputhatswana, Vhenda, Ciskei) states and former homelands. These are mostly tribal rural places, where land ownership is governed by customary laws. In these areas, despite having access to enormous areas of land by households, agriculture produces only a small amount of food. This demonstrates the lack of efficient land use available to households.

Household Food Production and Other Agricultural Activities

Not many households in South Africa's nine provinces cultivate their own land for food or other purposes. Consequently, the land that households are considered to "possess" is mostly used for residential purposes. Livestock production is a popular agricultural practice in many provinces. Compared to the production of other commodities, such as maize, livestock production seems to occur at a significantly small scale. In addition to livestock rearing, poultry farming is a popular agricultural activity that occurs at a modest scale in households throughout the provinces. Crop output is always supplemented by vegetables, potatoes, and legumes that are grown at subsistence levels.

Cascading this down to the level of provinces, food production and other agricultural activities indicate that at least 30% of the families in the districts of the province of Mpumalanga cultivate food and other agricultural items on their land; however, less than 3 ha of land is reserved for agricultural production. Fruit production is very low in every district of Mpumalanga. The Ehlanzeni region had the highest engagement in fruit production (nearly 10 %). The low household involvement rate in agricultural production can be explained by the abundance of industrial farms in the province. Historically Mpumalanga has produced a lot of citrus fruit, with the Ehlanzeni being the state's biggest orange producer.

For Limpopo, at least 70% of the households cultivate food and other agricultural goods on their land. It should be noted that Limpopo is largely rural, therefore subsistence farming is a common habit among the communities. In the Greater Sekhukhune district, approximately 43% of the households keep livestock. The Capricorn district also has a relatively high percentage of households practicing livestock production. The Vhembe district is predominantly a fruit- and vegetable-producing district with limited livestock rearing.

At least 57% of the households in the Northern Cape province cultivate food and other agricultural goods on their land. With a larger density of homes (75%) and yards between 5,000 and 10,000 square meters, the JTGDM district makes it simpler to utilize land for agricultural production. Households in the Namakwa district, where 41% of those with access to land use for agricultural production came in second. Compared to other provinces, stock farming is more frequent in the Northern Cape Province. Francis Baard is the only district with a lower percentage of livestock production (5%), while ZF Mgcawu (59%) and Namakwa (58%) districts have the greatest percentages of animal production. Challenges of land restitution, delays in land claims, and a general lack of agricultural extension support are major obstacles that limit households in the province from producing food through agricultural activities.

Very few homes in Western Cape Province grow or produce food on their land. In the Garden Route District, families that had access to land and used it for agriculture tended to be more common (30%). With the exception of the Garden Route District, it should be noted that a higher percentage of families (over 75%) indicated that the size of the land (500 m2) at their possession was a limiting factor that hindered them from producing food. There were consequently few options for backyard food production on land that was considered to be the household's "possession." Additionally, livestock production and rearing are low in the province. The only district with a slightly larger percentage of livestock production was the West Coast District (38%), followed by the Garden Route District(28%).

A moderate number of households in the province of Eastern Cape use the land for farming and food production. The two districts that had access to large tracts of land for agricultural development were OR Tambo (47%) and Amathole (41%). The percentage of households engaged in agriculture in Nelson Mandela Bay Metro (19%) was notably low. This is because the metro is urban, the majority of the land is privately owned, and the majority is utilized for industrial activities, including logistics, aviation, and various other industrial activities.

Several households raised cattle. However, this scale was low. Chris Hani, Amathole, and OR Tambo are the districts with a somewhat larger percentage of cattle rearing. These three districts are good for raising livestock because they are rural areas. It is apparent that fewer households raised poultry. Additionally, only a small percentage of households work to grow crops such as grains. This is only applicable to the areas of OR Tambo and Alfred Nzo.

In KwaZulu Natal, a significant number of households use their land for agriculture and food production. King Cetshwayo has the highest percentage of households that use their access to land for farming (81%), followed by uThukela and uMkhanyakude (67% each). Only one metro in the province, eThekwini, has the fewest households (19%) involved in land-based agriculture. This might be a result of the city's urbanization and the fact that heavy industrial activities and other professional services are dominant.

At least 30% of families in the Dr. Kenneth Kaunda and Dr. Ruth Segomotsi Mompati districts of the Northwest province engage in food production and other agricultural activities. However, the average area of land set aside for agriculture is insignificant. As a result, the land that a household is said to "own" is mostly used for residential purposes. A large concentration of mining operations, particularly for the Platinum Group Metals family of minerals, can be found in the province. Additionally, there is a sizable quantity of commercial farming, which directly affects the low levels of household farming activity.

Livestock production was not very high. Despite this, the Ngaka Modiri Molema District engages in extensive cattle farming. As a result, the district has gained a nickname “Texas, South Africa”. Districts with moderate animal farming include Dr. Ruth Segomotsi and Dr. Ngaka Modiri Molema. Households that grow fruit can be found in almost every district in the province. Households in Dr. Kenneth Kaunda District produce the most fruit.

Household Capacity for Resilience to Food Shocks and Scarcity

A combination of floods and the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed households to food shocks and how resilient they are to shock. Both events caused major problems in the food supply chain and the production process. Since families in South Africa depend on commercial supply for most of their food, they are therefore most vulnerable to market fluctuations and shocks. These "market shocks" include rising food prices, cuts in subsidies (for example, when they are not adjusted to match consumer prices), and job losses.

However, environmental effects such as drought often influence food production by reducing crop yields. Mitigating this effect, households compensate for crop losses by spending more on food purchases. Other response feedback includes pressure on expenditures, looking for substitutes, or putting pressure on the government to provide food. Given the high dependency of households on state grants, it is clear that households in South Africa have a low capacity for resilience to food shocks.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

In order for agriculture to effectively provide food and maintain its commercial viability, it is essential to utilize the land available to households[

27]. Food insecurity has been identified as a significant issue in provinces where households possess large amounts of tribal land, such as the Eastern Cape, Free State, Limpopo, and KwaZulu Natal, as well as those where households have limited access to land such as Gauteng, Western Cape, and Northern Cape. Therefore, This reflects that extent of abandonment of land use for agriculture. South Africa needs to educate families on how to supplement food they purchase from supermarkets through the cultivation of food from available land.

A low proportion of young people who have access to land suggests that young people have little participation in agriculture. The long term effect of this is a reduction in agricultural production and a reduced agricultural knowledge among youth. By making investments with the intention of improving this condition, it is crucial to foster young involvement in agriculture. With little participation of young people in agriculture it is obvious that South Africa's condition regarding food security is worrying. A major source of worry is the unsustainable reliance of many families on social subsidies as their sole source of income for food. This is compounded by the high unemployment rate. Numerous households will continues to be at danger of food insecurity. Despite the fact that some households have been found to be able to provide for themselves through agricultural output, it is crucial to bear in mind that unforeseen occurrences like droughts, storms, and floods can result in changes that render households more susceptible to food insecurity[

28].

To improve household nutrition, the potential to produce livestock products, such as milk, cheese, and butter in rural areas should be considered. This is based on the finding that cattle rearing is a common practice throughout the country. According to the 2022 National Food and Nutrition Security Survey, the production of a variety of crops does not increase the food supply for families, especially in rural areas29.

Promotion of domestic food production, where households are assisted to produce their own food to ensure food security, is desirable. Authorities must consider focused investment that seeks to promote household food production. To provide an immediate market for a surplus, the establishment of food banks and local markets worth considering. Furthermore, there is a need to increase agricultural production in each district of the province through focused investments in food production and agro-processing.

As could be deduced from the results, There is a growing competition on land priorities. This was further observed during the phases of data collection for the survey. This poses a threat to the sustained agricultural production. People seem to prefer obtaining large pieces of land and using it to build houses rather than food production. As land is limited, authorities need to develop guidelines for land use, especially in rural areas, where most of the land under tribal authority is not used for agriculture but for settlement. Developing guidelines for the zoning of land in rural areas and its utilization for agricultural production are needed. This will increase and sustain agricultural production in the rural areas of South Africa. This has the potential to allow agriculture to serve as a significant source of income for households.

To improve access to the market by producers, informal traders and small businesses that trade with agricultural products need assistance to improve the quality of their services through quality assurance and extend the lifespan of their products. COVID 19 has irreversibly transformed human perceptions of food and food safety. As a result, people have realized the importance of consuming safe and healthy food, not only to boost their immune system but also to prevent the spread of diseases30. As revealed in this study, people do not have equal access to safe and healthy food. For most poor people, informal traders are their main source of food. For this reason, there is a proposal to integrate food safety and quality standards in the operations of informal traders and small-to-medium enterprises. This will improve the quality of the food items traded and increase the profits of informal traders.

In comparison to one member of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) bloc, it is evident that China is the largest contributor to global food stock. It is the world's top producer of food, which is evident when comparing South Africa's status with that of China. It generates an amazing 1.3 billion metric tons of food yearly, accounting for 30% of the world's total food production. It is the largest agricultural superpower in terms of sheer volume, producing over a third of maize and nearly half of the world's wheat and rice. It has great potential to produce more food at prices lower than the global average because of its enormous land area. However, China also has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the world, with approximately one-third of its population suffering from malnutrition. However, China also has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the world, with approximately one-third of its population suffering from malnutrition.

According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, China is the world's top producer of a wide variety of crops including rice, wheat, potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplants. It also produces a considerable amount of livestock products such as chicken, pork, and eggs. To feed the largest population in the world, China's huge and diverse food production system has proven to be essential. However, to preserve food security, the country must cope with problems such as water scarcity, deteriorated soil, and climate change.

In conclusion, it can be stated that food insecurity in South Africa may also derive from the lack of efficient use of land available to households. This is compounded by a low levels of coping to shocks and disasters, as has been shown in all provinces of South Africa. To ameliorate these effects on households, the best use of available land for food production is urgently needed. This will require the application of a combination of technologies that have been developed by nations such as China, which are able to feed their populations that are much larger than that of South Africa.

References

-

1.Contò, F., Fiore, M., Monasterolo, I. & P. La Sala. (2014). Understanding the role of agriculture for sustainable and inclusive development. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 36(4): 766–774. [CrossRef]

-

2.Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), (1996). The state of world food and agriculture. FAO Agriculture Series. No 29. 352pp.

-

3.Pinstrup-Andersen, P. (2009). Food security: Definition and measurement. Food Security:1, 5–7.

-

4.Balwinder, S., Shirsath, P. B., Jat, M. L., McDonald, A. J., Srivastava, A. K., et al. (2020). Agricultural labor, COVID-19, and potential implications for food security and air quality in the breadbasket of India. Agricultural Systems 185:102954. [CrossRef]

-

5.Mock, N.; Morrow, N.; Papendieck, A. (2013). From complexity to food security decision-support: Novel methods of assessment and their role in enhancing the timeliness and relevance of food and nutrition security information. Global Food Security: 2, 41–49.

-

6.Karlen, D. L., Sadler, E. J., and Camp, C. R. (1987). Dry matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium accumulation rates by corn on norfolk loamy sand. Journal of Agronomy. 79, 649–656. [CrossRef]

-

7.Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Xue, J.; Ming, B.; Xie, R.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Hou, P. (2022) Effect Mechanism of Solar Radiation on Maize Yield Formation. Agriculture, 12, 2170. [CrossRef]

-

8.Stats SA (2019). The extent of Food Security in South Africa. http://www. https://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=12135. Accessed, May 2025.

-

9.Ingram, J., Ericksen, P. and Liverman, D. (2010). Food Security and Global Environmental Change. Earthscan, London, UK.

-

10.Badran A, Murad S, Baydoun E, Daghir N (2017) Water, energy & food sustainability in the middle east. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

-

11.Asrat Guja Amejo, Yoseph Mekaska Gebere, Habtemariam Kassa and Tamado Tawa, (2018). Agricultural productivity, landuse and drought animal power formula derived from mixed crop-livestock systems in southwestern Ethiopia. African Journal of Agricultural Research 13(42): 2362-2381. [CrossRef]

-

12.Thompson, J., & Scoones, I. (2009). Addressing the dynamics of agri-food systems: an emerging agenda for social science research. Environmental Science & Policy, 12(4), 386–397.

-

13.World Bank (2011). Climate-smart agriculture: increased productivity and food security, enhanced resilience and reduced carbon emissions for sustainable development. World Bank, Washington DC.

-

14.van den Driessche P, Watmough J. 2002. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math Biosci. 180:29–48.

-

15.Punia, H. et al. (2020). Solar Radiation and Nitrogen Use Efficiency for Sustainable Agriculture. In: Kumar, S., Meena, R.S., Jhariya, M.K. (eds) Resources Use Efficiency in Agriculture. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

-

16.Aranda, I., Pardos, M., Puértolas, J., Jiménez, M. D., and Pardos, J. A.(2007). Water-use efficiency in cork oak (Quercus suber) is modified by the interaction of water and light availabilities. Tree Physiol. 27, 671–677. [CrossRef]

-

17.Arrigo, K. R. (2005). Marine microorganisms and global nutrient cycles. Nature 437, 349–355. [CrossRef]

-

18.Birk, E. M., and Vitousek, P. M. (1986). Nitrogen availability and nitrogen use efficiency in loblolly pine stands. Ecology 67, 69–79. [CrossRef]

-

19.de Wit, C. T. (1992). Resource use efficiency in agriculture. Agricultural Systems 40, 125–151. [CrossRef]

-

20.Collins, O C and Duffy, K J. (2016). Optimal control of maize foliar diseases using the plants population dynamics, Acta Agriculture Scandinavica, Section B — Soil & Plant Science, 66:1, 20-26. [CrossRef]

-

21.Van Maanen A, Xu XM. (2003). Modelling plant disease epidemics. European Journal Plant Pathology 109:669–682.

-

22.Guo, X. X., Yang, Y. S., Liu, H. F., Liu, G. Z., Liu, W. M., Wang, Y. H., et al. (2020). Effects of solar radiation on root and shoot growth of maize and the quantitative relationship between them. Crop Science 61, 1414–1425. [CrossRef]

-

23.Gao, J., Zhao, B., Dong, S. T., Liu, P., Ren, B. C., and Zhang, J. W. (2017). Response of summer maize photosynthate accumulation and distribution to shading stress assessed by using 13CO2 stable isotope tracer in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1–12. [CrossRef]

-

24.DeMott, W. R., Gulati, R. D., and Siewertsen, K. (1998). Effects of phosphorus deficient diets on the carbon and phosphorus balance of Daphnia magna.Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1147–1161. [CrossRef]

-

25.Hou, P., Gao, Q., Xie, R., Li, S., Meng, Q., Kirkby, E. A., et al. (2012). Grain yields in relation to N requirement: Optimizing nitrogen management for spring maize grown in China. Field Crop. Res. 129, 1–6. [CrossRef]

-

26.Dordas, C. (2009). Dry matter, nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation, partitioning and remobilization as affected by N and P fertilization and source sink relations. European Journal of Agronomy 30, 129–139. [CrossRef]

-

27.Simelane, T. Mutanga, S.S. Hongoro, C. Parker, W. Mjimba V. Zuma, K. Kajombo, R. Ngidi, M. Masamha, B. Mokhele, T. Managa, R. Ngungu, M. Sinyolo, S. Tshililo, F. Ubisi, N. Skhosana, Ndinda, C. Sithole, M. Muthige, M. Lunga, W. Tshitangano, F. Dukhi, N., F. Sewpaul, R. Mkhongi, A. Marinda, E., 2023. National Food and Nutrition Security Survey: National Report: HSRC: Pretoria. ISBN: 978-0-6397-6316-3.

-

28.Wheeler, T.; von Braun, J. (2013). Climate change impacts on global food security. Science:341, 508–513.

-

29.Simelane, T. Mutanga, S.S. Hongoro, C. Parker, W. Mjimba V. Zuma, K. Kajombo, R. Ngidi, M. Masamha, B. Mokhele, T. Managa, R. Ngungu, M. Sinyolo, S. Tshililo, F. Ubisi, N. Skhosana, Ndinda, C. Sithole, M. Muthige, M. Lunga, W. Tshitangano, F. Dukhi, N., F. Sewpaul, R. Mkhongi, A. Marinda, E. (2023). National Food and Nutrition Security Survey: National Report: HSRC: Pretoria. ISBN: 978-0-6397-6316-3.

-

30.Simelane T. (2022). Containing the spread of COVID 19 through food safety and quality standards. Africa Insight 50(2): 122-134.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).