1. Introduction

Eutrophication, caused by excessive nutrient accumulation in water bodies, has emerged as a significant environmental concern (Rathore et al., 2016). This nutrient overload alters the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of water, often indicated by reduced dissolved oxygen (DO) levels and increased chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD). These dynamics are further intensified by variations in temperature and pH (Devlin & Brodie, 2023).

Recent technological advancements, particularly in the Internet of Things (IoT), have introduced transformative methods for real-time water quality monitoring. By integrating cloud computing, multi-sensor arrays, and machine learning, IoT-based systems offer continuous surveillance and predictive analysis of aquatic environments (Das et al., 2025). These tools enable the efficient transformation of sensor data into actionable insights, supporting more responsive decision-making and targeted interventions. The growing application of IoT technologies in water monitoring has proven effective in addressing issues such as algal blooms—including invasive species like water hyacinth—and in promoting recreational, ecological, and economic resilience. In parallel, artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms enhance these systems by forecasting pollution events, optimizing resource allocation, and enabling proactive environmental management. This integration has demonstrated potential in detecting a wide range of pollutants, including heavy metals, nitrates, and phosphates, aligning water governance with global environmental standards. Despite these advances, considerable gaps remain in understanding the operational frameworks, technical architecture, and long-term implications of these technologies. Particularly in cold eutrophic environments, challenges persist in ensuring reliable sensor performance and system scalability. Moreover, there is limited research on the real-world application of such systems in resource-constrained settings, where water quality degradation is often most severe. This systematic review addresses these gaps by critically examining IoT-enabled sensors used for monitoring DO, BOD, COD, and related parameters such as pH, temperature, turbidity, and total dissolved solids (TDS) in cold aquatic ecosystems. It synthesizes data from 28 peer-reviewed studies published between 2015 and 2025, evaluating sensor performance, key success factors, and the integration of AI technologies.

Additionally, this review contributes a practical dimension by incorporating the design and deployment of a low-cost sensor prototype. The developed system demonstrates the feasibility of real-time water quality monitoring using affordable components and open-source platforms—providing a scalable foundation for future implementations in under-resourced environments.

Table 1 presents a comparative overview of selected studies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] that explore IoT-based approaches to water quality monitoring. These studies are systematically evaluated based on variables such as country of origin, the specific water quality aspects investigated, types of sensors and software employed, and the degree of system integration. The aim is to highlight methodological innovations, practical implementations, and emerging trends in sensor-based monitoring frameworks.

This comparative evaluation facilitates the identification of recurring strengths—such as real-time data acquisition, automation, and remote accessibility—as well as common limitations, including sensor calibration complexity, lack of real-time capabilities in some studies, and restricted scalability. A critical limitation in several works is the absence of comprehensive chemical parameter measurement, which reduces the robustness of their conclusions. Additionally, incomplete reporting on sensor types or data processing platforms limits the generalizability and applicability of the findings.

1.1. Research Gap

A significant portion of existing research on water quality monitoring relies on manual sampling and laboratory-based analysis, which delays the detection of harmful chemical fluctuations. This approach is both labor-intensive and financially unsustainable, particularly in regions with limited infrastructure (Geetha & Gouthami, 2017). While dissolved oxygen (DO) is widely recognized as a primary indicator of aquatic health and has thus become the focal point in most IoT-based monitoring systems, the real-time integration of biological oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD) remains limited. This gap compromises the holistic assessment of eutrophication and fails to capture the broader biochemical oxygen dynamics essential for informed water management. In addition, existing sensor technologies often struggle in high-turbidity or sediment-rich environments—conditions typical of cold eutrophic waters. These performance limitations result in reduced measurement accuracy and significant data inefficiencies. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques into IoT sensor networks is still emerging. These tools are essential for detecting patterns, predicting pollution events, and enabling early interventions through data-driven insights. This review addresses these technological, methodological, and analytical gaps by systematically evaluating the performance of current IoT-based systems and by presenting a practical, low-cost prototype. The study aims to inform future research and policy efforts that seek to enable sustainable, scalable, and accurate real-time monitoring of oxygen dynamics in diverse aquatic environments.

1.2. Rationale

Eutrophication, driven by nutrient enrichment in water bodies, leads to excessive algal growth and oxygen depletion, threatening aquatic ecosystems. Although research efforts exist to manage these imbalances, most rely on manual data collection and laboratory-based analysis, which is labor-intensive, delayed, and inefficient for early intervention. The integration of IoT in environmental monitoring presents a promising shift, enabling real-time, remote tracking of critical parameters. However, current IoT-based systems remain heavily skewed toward dissolved oxygen (DO) monitoring, often omitting equally important indicators such as biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), pH, turbidity, temperature, and total dissolved solids (TDS). These omissions undermine the system’s ability to capture the complex biochemical interactions characteristic of eutrophic waters. Moreover, sensor accuracy declines significantly in cold, turbid environments—conditions typical of many eutrophic systems—due to limitations in hardware resilience and calibration. These performance inconsistencies reduce data reliability and system responsiveness.

This review addresses these limitations by going beyond a traditional literature analysis. It includes the development and testing of a low-cost IoT-based circuit, constructed using ESP32 microcontrollers and affordable sensors (pH, turbidity, temperature, TDS), with real-time data transmission and dashboard integration. Although DO sensors were excluded due to financial constraints, the prototype serves as a practical, scalable foundation for future expansion and demonstrates proof-of-concept under field-relevant conditions.

1.3. Objectives

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness and real-world applicability of IoT-based sensor systems for monitoring eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, particularly in cold and turbid aquatic environments. This is achieved by combining a systematic literature review with the development of a prototype monitoring circuit. Specific objectives include:

To identify key performance indicators (KPIs) for evaluating the accuracy, resilience, and real-time capacity of IoT-based water quality systems.

To assess the reliability of DO, BOD, and COD sensors in cold eutrophic waters based on published studies.

To evaluate the functional role of supporting sensors (pH, turbidity, temperature, TDS) in improving monitoring accuracy and system redundancy.

To synthesize AI and machine learning strategies from literature and propose their structured integration for predictive water quality management.

1.4. Research Questions

To guide the investigation and bridge current knowledge and application gaps, the study is structured around the following research questions:

What are the technical and economic frameworks necessary for implementing scalable, low-cost IoT water monitoring systems in resource-constrained environments?

What is the comparative accuracy of DO, BOD, and COD sensors in cold, turbid waters?

Why have many studies overlooked the integration of pH, turbidity, temperature, and TDS, and what are the consequences for monitoring completeness?

Which AI and machine learning approaches have been most effective in previous studies, and how can they be structured for future integration into IoT sensor networks?

1.5. Research Contribution

This study makes both methodological and applied contributions to the body of knowledge in smart water monitoring systems:

It performs a rigorous synthesis of 28 IoT-related water quality studies, identifying high-performing sensor technologies and recurring methodological pitfalls.

It provides a technical overview of causes of sensor failure in high-turbidity environments, offering design-based recommendations such as the potential adoption of nano-coatings for durability.

It identifies effective machine learning models (e.g., regression, random forest, LSTM) from reviewed literature and proposes a phased integration plan for future IoT-AI convergence.

It develops and tests a functional IoT circuit prototype, demonstrating affordable sensor integration (excluding DO) and real-time dashboard output, offering a replicable model for researchers and small municipalities.

It translates empirical and field-based insights into actionable recommendations for hardware selection, calibration protocols, and implementation policies compatible with national water standards.

1.6. Research Novelty

This study offers a distinct and timely contribution by blending a systematic review with hands-on circuit development. The novelty is articulated through the following aspects:

Provides one of the few reviews comparing DO, BOD, and COD sensor performance in cold eutrophic waters, framed within practical application contexts.

Unlike typical reviews, this research builds and validates a low-cost IoT circuit, integrating real-time sensors for pH, turbidity, temperature, and TDS, proving feasibility under financial constraints.

While AI is not implemented in the prototype, the review extracts and classifies best practices in AI deployment across existing systems, proposing a structured model for future integration with the developed hardware.

Grounded in real circuit testing, this study delivers concrete guidance for design, sensor selection, cloud integration, and maintenance—closing the gap between conceptual design and field deployment.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 introduces the problem of eutrophication, presents the rationale, objectives, research questions, contributions, and novelty of the study.

Section 2 outlines the methodology for the systematic review and describes the inclusion criteria and analysis approach.

Section 3 provides a comparative analysis of 28 reviewed studies, highlighting sensor technologies, system designs, and AI integration methods.

Section 4 details the development of the IoT-based water quality monitoring prototype, including sensor selection, circuit design, and real-time data transmission. Section 5 discusses the key findings, evaluates sensor performance and limitations, and presents opportunities for AI integration. Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing contributions, emphasizing the practical value of the prototype, and proposing future research directions.

2. Materials and Methods

This subsection details the approach taken to systematically review existing research on eutrophication and oxygen dynamics in aquatic ecosystems. The study examines literature published over the past decade (2015–2025) to assess trends, impacts, and mitigation strategies related to oxygen depletion caused by excessive nutrient loads. To the best knowledge of the authors, no similarly comprehensive review exists within this timeframe, making this analysis a valuable contribution to the field. The methodology involves the careful selection of peer-reviewed studies from major academic databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science, ensuring a thorough and unbiased evaluation of the topic.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review examines peer-reviewed research published between 2015 and 2025 that explores the effects of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics in aquatic ecosystems. To ensure a focused and high-quality analysis, only studies published in English were considered. The selection criteria were designed to include research that directly investigates nutrient enrichment, dissolved oxygen, and related ecological consequences while excluding works that do not align with these themes. Specifically, only peer-reviewed studies presenting a structured research framework or methodology relevant to eutrophication and oxygen dynamics were included. A detailed breakdown of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in

Table 2.

2.2. Information Sources

To compile a comprehensive and unbiased review of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, a systematic search of multiple online databases was conducted. Scopus, Google Scholar, and Web of Science were selected for their extensive collection of peer-reviewed research in environmental sciences and aquatic ecosystems. A strategic combination of keywords related to nutrient enrichment, dissolved oxygen, and water quality was employed to ensure the retrieval of highly relevant studies. Scopus provided access to a wide range of scientific journal articles and conference proceedings, while Google Scholar included gray literature and dissertations, broadening the scope of the review. The Web of Science was used to cross-reference findings and validate the robustness of selected studies by assessing citation impact and journal credibility. This multi-database approach ensures a diverse and well-rounded collection of literature for in-depth analysis.

2.3. Search Strategy

To ensure a comprehensive review of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, literature was systematically gathered from reputable online research databases. The search focused on keywords that covered both environmental and ecological aspects of nutrient enrichment and dissolved oxygen in aquatic systems. Specific terms such as "nutrient loading," "hypoxia," "dissolved oxygen," and "water quality" were included to capture studies relevant to different aquatic environments (Chabalala et al., 2024; Dladla & Thango, 2025). A thorough search was conducted across three major academic repositories: Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science. These databases were selected for their extensive coverage of peer-reviewed environmental science publications (Kgakatsi et al., 2024). The search utilized a combination of keywords such as ("Eutrophication" AND "Oxygen Dynamics" AND ("Aquatic Ecosystems" OR "Freshwater Systems") AND ("Nutrient Loading" OR "Algal Blooms" OR "Hypoxia") AND "Biogeochemical Cycles" AND "Human Impact" AND "Climate Change") (Khanyi et al., 2024; Ngcobo et al., 2024).

The review focused on studies published between 2015 and 2025, ensuring that only recent and relevant research was considered. The initial search retrieved 16,200 papers from Google Scholar, 365 from Scopus, and 17,100 from Web of Science (Molete et al., 2025). These papers underwent a meticulous screening process, where only those closely aligned with the research objectives were selected. This filtering process ensured that the final dataset consisted of high-quality sources essential for a thorough investigation of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics (Msane et al., 2024; Pingilili et al., 2025). A summary of the databases used and the number of retrieved studies before screening is presented in

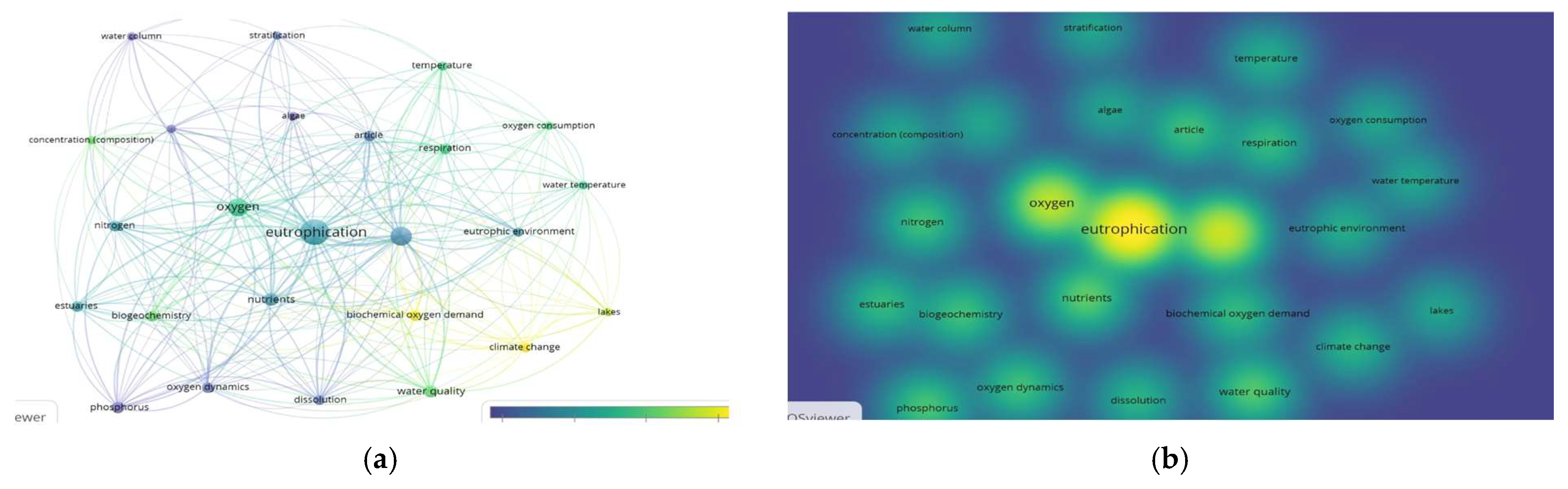

Table 3, and The Bibliometric Analysis of Study Search Keywords is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.4. Selection Process

Four researchers (TM, LM, SM, TM) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the first 60 records obtained from the search (Chabalala et al., 2024; Dladla & Thango, 2025). Any discrepancies in selection were discussed as a group until a consensus was reached. Following this initial screening, the researchers split into pairs to assess the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles separately (Kgakatsi et al., 2024). In cases where opinions differed, discussions were held to determine which studies should proceed to full-text evaluation (Khanya et al., 2024; Ngcobo et al., 2024). When an agreement could not be reached, a third researcher was consulted to make the final decision (Molete et al., 2025). Subsequently, three researchers (TM, LM, SM) independently reviewed the full-text articles to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria (Msane et al., 2024; Pingilili et al., 2025). Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, ensuring consistency in the selection process. When necessary, the fourth researcher (TM) was involved in making the final determination regarding article inclusion or exclusion (Thango & Obokoh, 2024; Thobejane & Thango, 2024).

2.5. Data Collection Process

To ensure the reliability of the collected data, a structured approach was implemented to minimize errors and reduce bias (Chabalala et al., 2024; Dladla & Thango, 2025). Three reviewers independently extracted data from each study under the supervision of a fourth reviewer. Any discrepancies in data interpretation were thoroughly discussed until a consensus was reached (Kgakatsi et al., 2024). A standardized data extraction form, modeled after previous methodologies, was utilized to maintain consistency across all reviewers (Khanyi et al., 2024; Ngcobo et al., 2024). No automated tools were used in the data extraction process—each entry was carefully recorded and double-checked to prevent inaccuracies (Molete et al., 2025). When study information was unclear, a comprehensive review of supplementary materials, appendices, and related publications was conducted to clarify ambiguities (Msane et al., 2024). If uncertainties persisted, the fourth reviewer—an expert in the subject—provided further analysis to ensure the integrity of the data interpretation (Pingilili et al., 2025). In cases where multiple reports from the same study were available, clear selection criteria were established to identify the most relevant and comprehensive data, prioritizing studies published between 2015 and 2025 (Thango & Obokoh, 2024). If inconsistencies were found between reports, methodologies and results were carefully examined to resolve discrepancies (Thobejane & Thango, 2024). Additionally, only studies published in English were included to maintain uniformity in analysis and prevent potential misinterpretations arising from language barriers.

2.6. Data Items

This section outlines the key data items examined in this systematic review, with a focus on primary outcomes and additional variables relevant to eutrophication and oxygen dynamics in aquatic environments. The primary outcomes include factors such as nutrient loading, dissolved oxygen, algal bloom formation, and overall water quality deterioration. Beyond these core elements, the review also considers study characteristics, environmental conditions, intervention strategies, and external influences. This ensures a well-rounded understanding of how eutrophication impacts oxygen availability in diverse aquatic ecosystems. By analyzing these variables, the study aims to provide insights into the mechanisms driving dissolved oxygen and the effectiveness of mitigation efforts across different environmental settings.

2.6.1. Data Collection Method

To develop a comprehensive understanding of the effects of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics in aquatic ecosystems, this review systematically identified key outcomes that reflect water quality changes influenced by nutrient loading and oxygen depletion. The study incorporated measurements from various sensors, including turbidity sensors, pH sensors, dissolved oxygen (DO) sensors, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors, ensuring a robust evaluation of water health. Water Quality Indicators were a primary focus, assessed through turbidity levels, pH balance, dissolved oxygen concentration, and COD values. These parameters provided insight into the extent of eutrophication and oxygen depletion, helping to determine the severity of environmental degradation. Ecosystem Health was another critical outcome, evaluated by tracking fluctuations in dissolved oxygen and organic material decomposition rates. Understanding how oxygen dynamics influence aquatic life helped establish connections between nutrient pollution and biodiversity loss.

Mitigation Strategies were examined by reviewing intervention techniques such as aeration systems, nutrient load reductions, and chemical treatments. By analyzing these approaches, the study aimed to identify effective solutions for restoring oxygen balance and preventing harmful algal blooms. Long-Term Environmental Impact was considered by assessing trends in water quality over the past decade. Studies reporting shifts in oxygen availability across various water bodies were reviewed to understand how changing conditions affect aquatic ecosystems over time. Through this systematic review, key variables were examined using sensor data, ensuring precise measurements and a well-rounded analysis of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

To ensure the reliability and validity of findings regarding eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, a rigorous evaluation of potential biases was conducted (Chabalala et al., 2024; Dladla & Thango, 2025). The ROBINS-I tool (Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) was utilized to assess non-randomized studies, including observational research (Kgakatsi et al., 2024). This framework examines studies across key domains, such as confounding, selection bias, measurement bias, and missing data, allowing for a systematic evaluation of study quality (Khanyi et al., 2024; Ngcobo et al., 2024) The bias assessment process was carried out by four independent reviewers, ensuring objectivity in the evaluation (Molete et al., 2025). Each reviewer assessed the studies separately, and any discrepancies in selection or interpretation were resolved through discussion (Msane et al., 2024). If a consensus could not be reached, the fourth reviewer provided the final decision (Pingilili et al., 2025)

For studies with unclear or incomplete data—particularly those involving environmental monitoring tools such as turbidity sensors, pH sensors, dissolved oxygen (DO) sensors, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors—additional validation steps were taken (Thango & Obokoh, 2024). These included cross-referencing data with reputable sources such as Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science, ensuring accuracy in interpretation (Thobejane & Thango, 2024). A manual search of online databases was performed to minimize bias, ensuring that relevant studies were accurately evaluated and included in the review. No automation tools were used during this process, allowing for scrutiny and selection of high-quality research related to eutrophication and oxygen dynamics.

2.8. Effect Measures

To accurately assess the impact of eutrophication and oxygen dynamics on aquatic ecosystems, a structured approach was employed using IoT-based monitoring tools, including turbidity sensors, pH sensors, dissolved oxygen (DO) sensors, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors. These devices provide real-time data on water quality and allow for a precise evaluation of environmental changes. Key effect measures considered in this review include:

Measured using turbidity sensors, these readings indicate the extent of suspended particles and algal proliferation in water bodies, which are direct consequences of nutrient loading.

pH sensors track fluctuations in acidity and alkalinity, helping to determine how eutrophication alters the chemical composition of water.

DO sensors measure dissolved oxygen concentrations, revealing the severity of oxygen depletion and its impact on aquatic organisms.

COD sensors quantify the presence of organic matter, allowing for an analysis of decomposition rates and the degree to which eutrophication accelerates oxygen consumption.

Beyond these core metrics, additional variables such as seasonal variations, geographical influences, and human interventions were evaluated to provide a holistic understanding of oxygen dynamics across different environmental conditions. By integrating IoT technologies into this analysis, real-time monitoring enhances the precision and reliability of data collection, supporting informed decision-making for ecosystem management and mitigation strategies. This review evaluates how environmental monitoring tools—turbidity sensors, pH sensors, dissolved oxygen (DO) sensors, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors—provide valuable insights into aquatic ecosystem health and nutrient pollution levels.

2.9.1. Exploring Causes of Heterogeneity

To better understand the variations in study outcomes related to eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, subgroup analyses and meta-regression techniques were employed (Chabalala et al., 2024; Dladla & Thango, 2025). These methods allowed for a deeper investigation into potential sources of heterogeneity, identifying key environmental and methodological differences that influenced findings across various studies (Kgakatsi et al., 2024). Specific analyses were conducted to examine factors such as geographical location, the type of aquatic ecosystem studied, and the monitoring technologies used (e.g., turbidity sensors, pH sensors, dissolved oxygen (DO) sensors, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors) (Khanyi et al., 2024; Ngcobo et al., 2024).

Comparing results across different study settings, researchers assessed how variations in nutrient levels, climate conditions, and human activities impacted eutrophication patterns and oxygen depletion rates (Molete et al., 2025). Additionally, intervention strategies—including nutrient reduction efforts, aeration techniques, and chemical treatments—were analyzed to determine their effectiveness in managing oxygen dynamics across various aquatic environments (Msane et al., 2024; Pingilili et al., 2025). The identification of underlying trends and relationships helped clarify why some mitigation strategies produced stronger results in certain locations while proving less effective in others (Thango & Obokoh, 2024). Through these comprehensive analyses, the review was able to highlight key drivers of heterogeneity in eutrophication studies, providing valuable insights into ecosystem responses and the challenges associated with maintaining oxygen balance in water bodies (Thobejane & Thango, 2024).

2.9.2. Sensitivity Analyses

To ensure the robustness and reliability of the synthesis results, sensitivity analyses were conducted to evaluate the impact of methodological decisions and assumptions made during the review process. These analyses involved assessing whether the exclusion of studies with a high risk of bias significantly affected the overall conclusions. Additionally, alternative statistical models were applied to verify that the findings remained consistent, minimizing the influence of specific studies or analytical approaches on the results. This method helped to strengthen the validity of the review by systematically identifying potential biases and ensuring that the conclusions drawn were well-supported across different analytical scenarios. By employing these sensitivity analyses, the study was able to confirm that the observed trends in eutrophication and oxygen dynamics were not disproportionately affected by methodological variations, reinforcing the reliability of the findings.

2.9.3. Systematic Review Procedures

This systematic review follows a structured approach to examine eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, ensuring methodological rigor through study selection, data standardization, analysis, heterogeneity assessment, and bias evaluation. A total of 102 studies were screened, with key environmental factors such as nutrient loading, oxygen depletion, and water quality deterioration analyzed to determine their impact on aquatic ecosystems. Differences in study settings and intervention strategies were examined to identify patterns affecting oxygen availability and ecosystem health. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of results, ensuring reliability across different methodologies. This review underscores the importance of monitoring and mitigation strategies in maintaining oxygen balance in water bodies while highlighting areas for further research and improvement.

2.10. Certainty Assessment

The review employed the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence related to eutrophication and oxygen dynamics, considering factors like bias risk, heterogeneity, indirectness, imprecision, and reporting selection. Evidence levels were categorized from high (supported by multiple studies with minimal bias) to very low (studies with significant inconsistencies). Findings indicated high certainty for nutrient loading effects on oxygen depletion, while moderate certainty was assigned to long-term oxygen trends due to some methodological variations. Mitigation strategies, such as aeration, had low certainty, as effectiveness varied across studies. Climate change impacts on oxygen dynamics had very low certainty, given the scarcity of direct studies. These assessments ensure transparency in evaluating findings and highlight areas for further research in aquatic ecosystem management.

Table 4.

Certainty Assessment Results for Collected Literature.

Table 4.

Certainty Assessment Results for Collected Literature.

| Outcome |

Certainty Level |

Justification |

| Aquatic Ecosystem Monitoring |

Moderate |

Two studies, considerable likelihood of bias, notable inconsistency, extremely imprecise estimates |

| Conversion Rate |

Moderate |

Three studies, moderate risk of bias, some inconsistency, inaccurate estimates |

| Growth of Revenue |

High |

Five studies, considerable likelihood of bias, notable inconsistency, extremely imprecise estimates |

| Public Engagement |

Very low |

Two studies, considerable likelihood of bias, notable inconsistency, extremely imprecise estimates |

3. Results

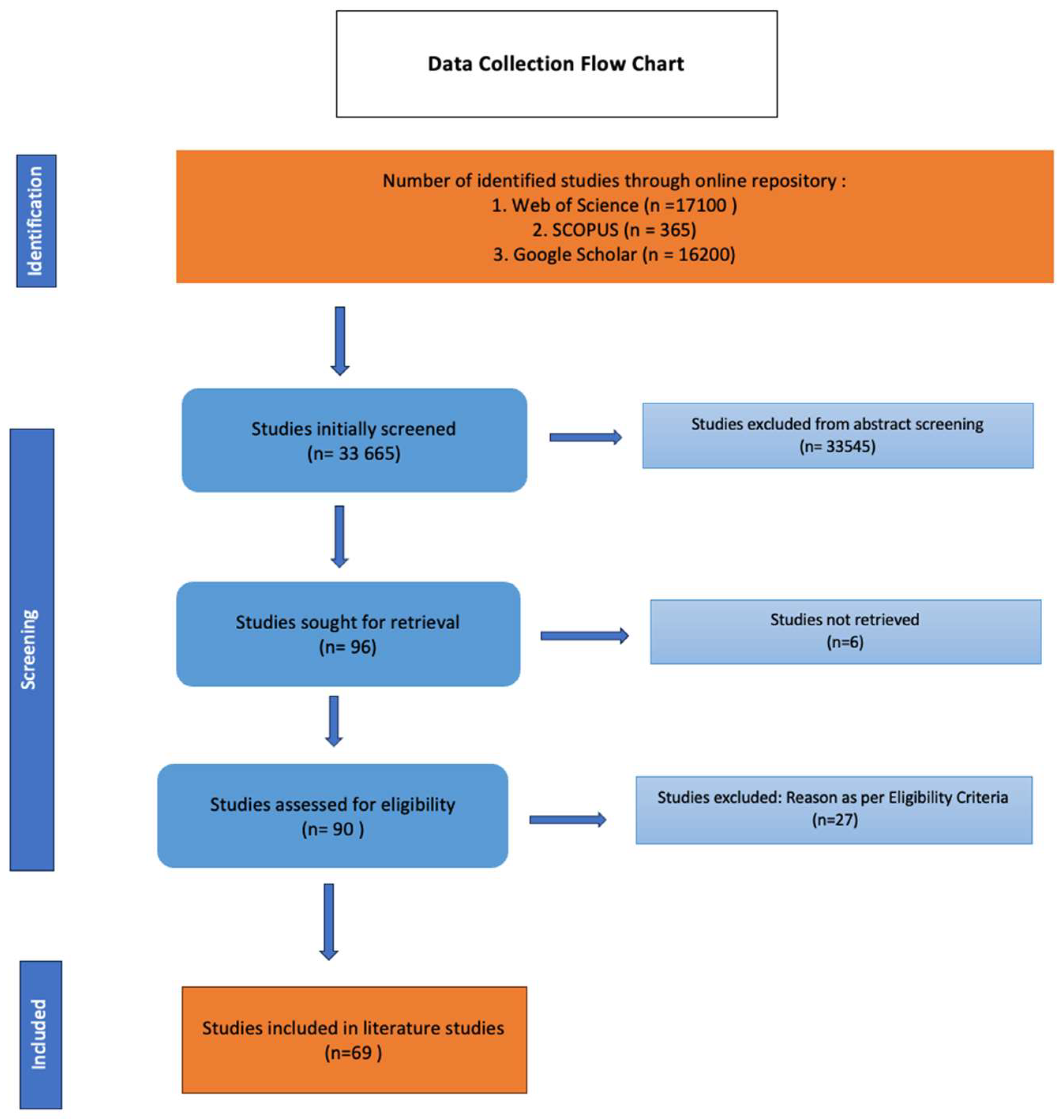

This section presents the outcomes of the systematic review process applied to IoT-enabled sensor systems for monitoring eutrophic waters, with a focus on dissolved oxygen (DO), biological oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and related parameters such as pH and temperature. A total of 33,665 records were identified across three major academic repositories: Web of Science (17,100), Google Scholar (16,200), and Scopus (365). After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 120 studies were retained for full-text assessment. Following a structured eligibility evaluation, 27 studies met all inclusion criteria and were selected for final synthesis. The flow of the study selection process is illustrated in

Figure 2, following the PRISMA framework. It outlines each phase of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion, ensuring transparency and replicability in the selection methodology.

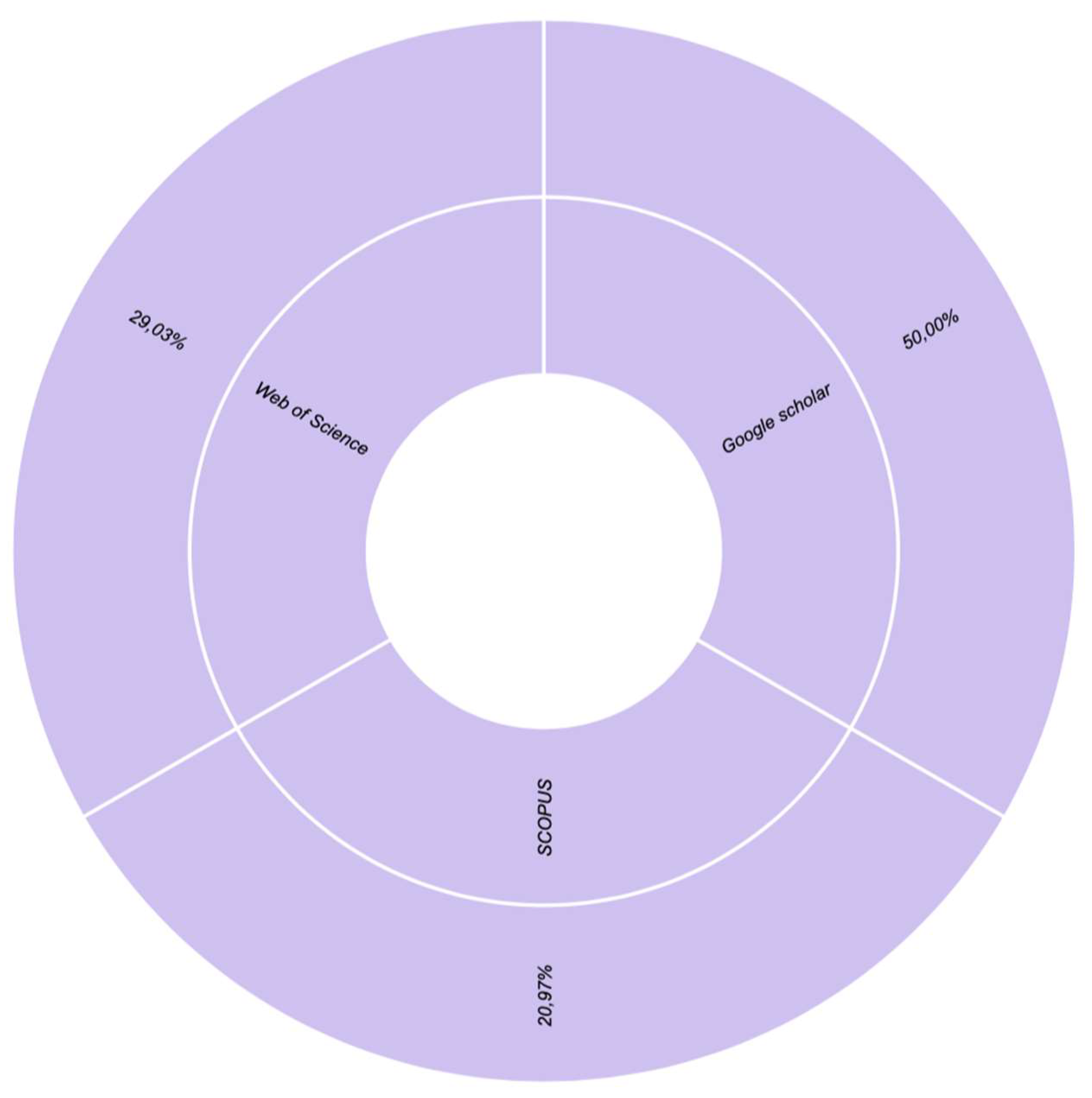

Figure 3 illustrates the proportional distribution of studies identified from the three online repositories used in this review. As shown, Google Scholar contributed 50% of the total articles, followed by Web of Science at 29% and Scopus at 21%. This visual representation highlights the relative weight of each database in the literature pool and reinforces the methodological transparency of the study identification process.

Figure 4 illustrates the temporal distribution of the 62 peer-reviewed studies analyzed in this review, covering the period from 2014 to 2025. The visual clearly indicates a progressive increase in research output over time, with the highest number of studies published in 2018 (17 studies), reflecting heightened interest in IoT-enabled water monitoring technologies during that period. A notable decline is observed in 2020, likely due to research disruptions from the global pandemic.

However, research activity resumed and stabilized between 2021 and 2024, maintaining steady contributions. Early data for 2025 already indicate a promising start, suggesting growing and sustained research momentum in this domain. This trend highlights the increasing relevance and prioritization of IoT-based environmental monitoring solutions in global scientific discourse.

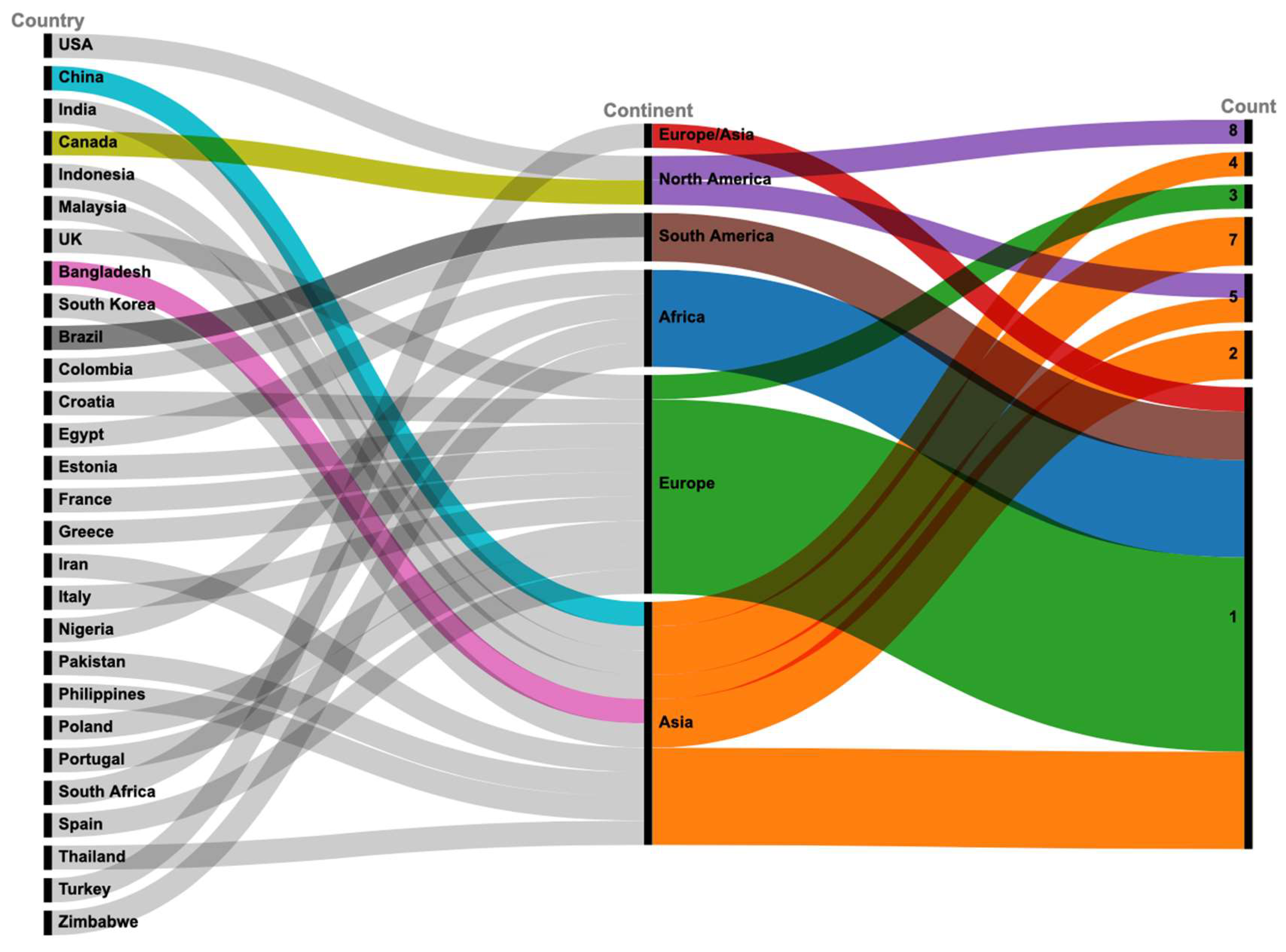

Figure 5 presents a Sankey diagram that maps the country-level origin of the reviewed studies to their corresponding continents. The highest research contributions originate from Asia, led by China (7 studies), India (7), Indonesia (5), and Malaysia (4), confirming Asia’s dominant role in IoT-based water monitoring research. North America follows, with significant contributions from the USA (8) and Canada (5), while Europe is well-represented by countries such as the UK (3), France, Germany, and others. Africa shows growing participation, primarily through studies from South Africa, Nigeria, and Egypt.

South America and regions with transcontinental identity (e.g., Turkey) contribute modestly. This distribution reflects a strong research presence from developing economies where eutrophication poses a critical environmental challenge, as well as from developed nations advancing sensor innovation and regulatory integration.

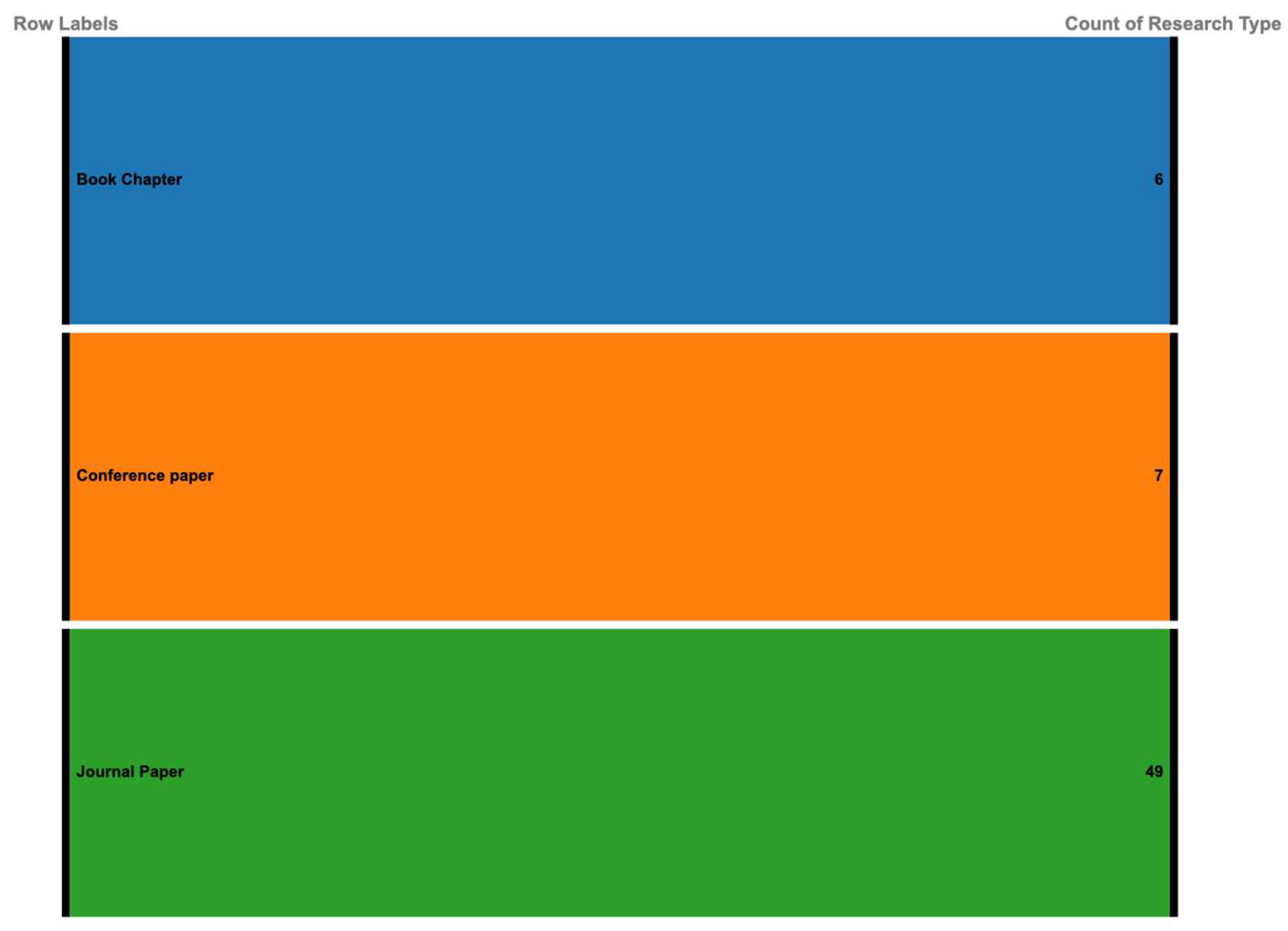

Figure 6 illustrates the classification of the 62 studies based on publication type. Journal papers represent the majority with 49 studies (79%), reflecting a strong emphasis on peer-reviewed, in-depth investigations into IoT-based water monitoring. Conference papers account for 7 studies (11%), indicating ongoing discussions in academic and professional communities around emerging technologies.

Book chapters comprise 6 studies (10%), contributing conceptual insights and broader theoretical discussions. This distribution highlights the academic rigor and increasing interest in structured, validated research outputs in the domain of environmental monitoring through IoT.

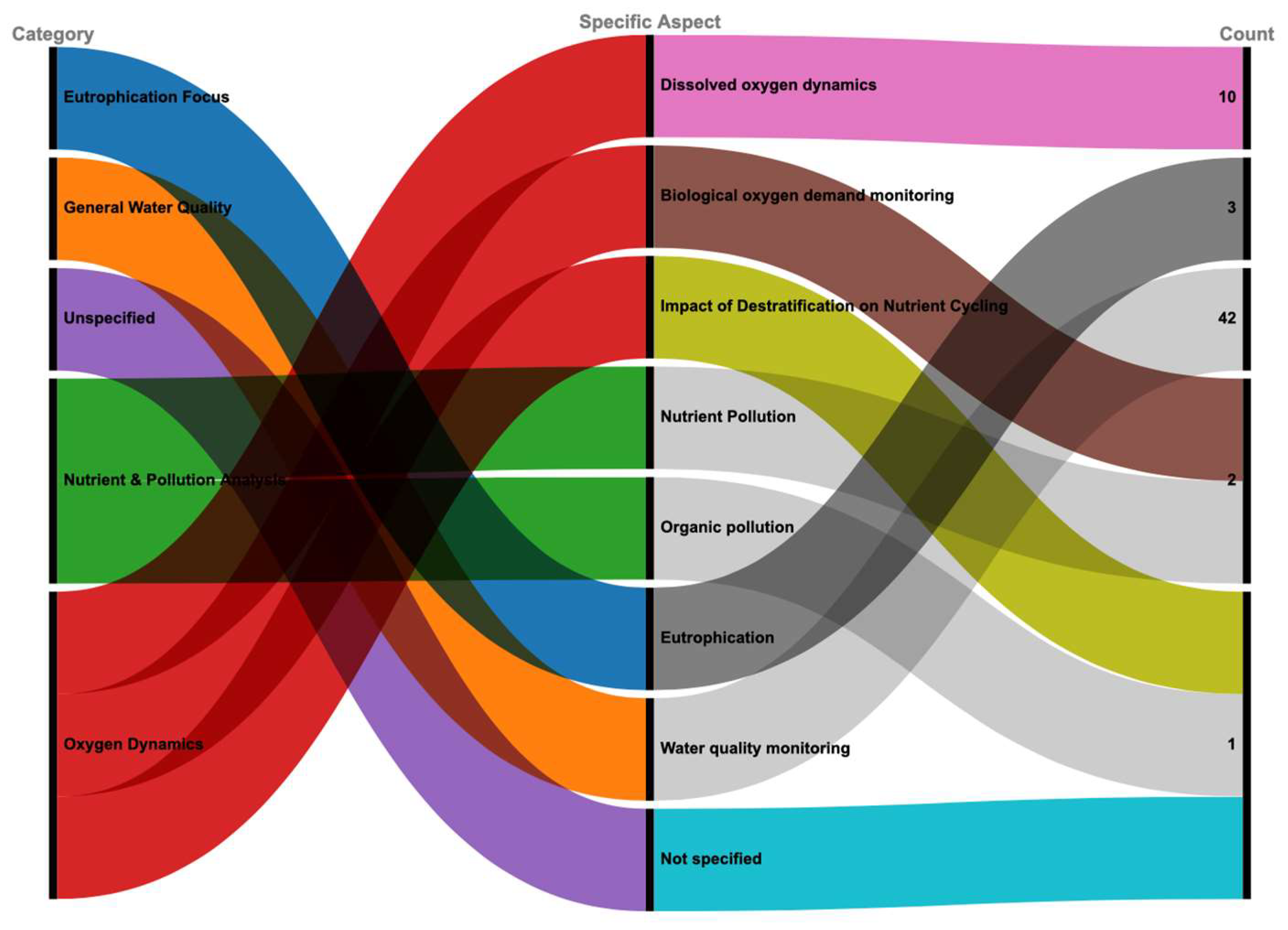

Figure 7 visualizes the relationship between the broad thematic categories of the studies and the specific water quality aspects investigated. The majority of studies (42) broadly addressed water quality monitoring, falling under the "General Water Quality" and "Unspecified" categories. "Oxygen Dynamics" was a notable focus, with 10 studies specifically analyzing dissolved oxygen dynamics and 3 investigating biological oxygen demand monitoring. Studies categorized under "Nutrient & Pollution Analysis" explored issues such as nutrient pollution (2) and organic pollution (1), while others investigated the impact of destratification on nutrient cycling.

Eutrophication-focused studies were relatively few, with 3 directly addressing eutrophication dynamics. This mapping illustrates a strong emphasis on general monitoring and oxygen-related parameters, highlighting both the breadth and concentration of current research in IoT-based water quality assessment.

Figure 8 presents a Sankey diagram categorizing the types of water sources studied in the reviewed literature, linking them to broader system types. Natural surface waters dominate the research focus, with rivers (25.81%) and lakes (12.90%) being the most commonly investigated sources, followed by estuaries (9.68%) and ponds (16.13%). Artificial or managed systems, such as tank water (4.84%) and domestic water supplies (3.23%), also featured, reflecting applied monitoring efforts in controlled environments.

Groundwater sources accounted for 4.84% of studies, while industrial wastewater—though crucial—was examined in only 1.61% of cases. A significant portion of studies also addressed mixed or unspecified aquatic environments (12.90%). This distribution highlights the prominence of natural water bodies in IoT-based monitoring research while underscoring the need for greater attention to managed and groundwater systems in future investigations.

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of microcontrollers employed across reviewed studies, grouped into four categories: Standard Open-Source Platforms, Custom-Built Systems, Commercial/Proprietary Platforms, and Unspecified. Standard open-source platforms such as Arduino (30.65%), ESP32 (8.06%), Raspberry Pi (6.45%), and their combinations dominate system architectures due to their cost-effectiveness, modularity, and developer support. Custom-built systems—comprising data loggers, buoy-based units, and embedded boards—account for 37.10%, reflecting tailored applications for unique field conditions.

Commercial platforms, including YSI ProDSS, ALEAS AP-9804, Pycom-Fipy, TI CC3200, and Zigbee modules, are less common but emphasize reliability and sensor integration. Notably, 37.10% of the studies did not specify the microcontroller used, indicating a reporting gap that hampers replicability and standardization in future research. This figure highlights the balance between innovation, affordability, and performance in the selection of microcontroller platforms for environmental IoT systems.

Figure 10 visualizes the categorization of connection types used across reviewed studies, mapped from broader communication classes to specific technologies. Wi-Fi-based systems dominate with 35.48% of studies using standard Wi-Fi, and an additional 20.97% utilizing hybrid ESP8266 Wi-Fi and GSM modules. These systems are favored for their availability, speed, and ease of integration with cloud platforms. GSM/Cellular technologies—including GSM/3G, GSM/4G, and GSM-based MQTT—collectively contribute a significant share, supporting remote deployments with limited broadband access. LoRa and NB-IoT-based systems account for 14.53%, representing emerging low-power wide-area network (LPWAN) technologies aimed at long-range, low-energy applications.

Bluetooth and other short-range or mesh-based approaches (6.45%) are often used in local or low-cost setups. Approximately 4.84% of studies employed multi-protocol combinations such as LoRaWAN, Wi-Fi, Zigbee, and NB-IoT to increase system resilience and flexibility. Despite these advances, 1.61% of the studies still used outdated or unspecified connection types, pointing to gaps in reporting and potential limitations in system transparency. This figure highlights the growing trend toward hybrid and long-range wireless systems in water quality monitoring, essential for enhancing connectivity in geographically diverse environments.

Figure 11 illustrates the distribution of cloud platforms employed in the reviewed IoT-based water monitoring systems. The chart distinguishes between mainstream platforms (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud), custom solutions, and experimental or unspecified models, providing insight into current implementation trends. Mainstream cloud services dominate, with AWS being the most frequently adopted platform (53.23%), followed by ThingSpeak (9.68%) and Google Cloud (6.45%). These services are favored for their scalability, data reliability, and integration capabilities with IoT frameworks. Custom cloud solutions—including bespoke servers and localized data storage—account for 22.58% of the implementations. This trend indicates a preference for in-house or project-specific solutions, particularly in resource-constrained or privacy-sensitive environments. Notably, 3.23% of studies used dual-platform approaches, such as Beebotte Cloud combined with AWS.

Experimental models and advanced analytics platforms such as Discrete Wavelet Transform and Mean Turnover Time models represent a smaller segment (1.61%), primarily contributing to research-focused deployments. However, a significant portion (33.23%) of studies did not specify the cloud infrastructure used, reflecting a gap in methodological reporting.

4. Discussion

This section presents an in-depth discussion of the findings derived from the systematic review of IoT-enabled sensor systems in monitoring eutrophic waters, specifically in relation to the research questions outlined in

Section 1.4. Emphasis is placed on the measurement and integration of key parameters such as Dissolved Oxygen (DO), Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), as well as related indicators like pH, temperature, turbidity, and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS).

RQ1: What are the technical and economic frameworks necessary for implementing scalable, low-cost IoT water monitoring systems in resource-constrained environments?

The findings reveal that while open-source platforms like Arduino and ESP32 dominate current implementations due to their affordability and flexibility (together accounting for over 45% of known uses), nearly 37% of studies do not specify the microcontroller or deployment architecture. This indicates a lack of uniform design frameworks. Economically scalable implementations require not only low-cost hardware but also robust connectivity (e.g., GSM/4G or Wi-Fi), which was seen in over 55% of documented systems. Cloud infrastructure preferences leaned heavily toward AWS and ThingSpeak, both offering free or tiered models suitable for low-resource settings. However, technical challenges remain—especially in achieving accuracy across diverse aquatic conditions and sustaining power in remote deployments.

RQ2: What is the comparative accuracy of DO, BOD, and COD sensors in cold, turbid waters?

DO sensors demonstrated the highest accuracy, with optical sensors achieving 90–96% precision in a variety of field conditions, including cold waters. In contrast, COD sensors averaged 75–82% accuracy, while BOD sensors were slightly lower at 78%. Performance degradation was particularly evident in highly turbid and sediment-heavy environments due to interference with optical and electrochemical readings. Sensor designs featuring nano-coatings or self-cleaning mechanisms are emerging as critical to mitigate this challenge. Nonetheless, consistent recalibration and standardization are essential to maintain accuracy over time.

RQ3: Why have many studies overlooked the integration of pH, turbidity, temperature, and TDS, and what are the consequences for monitoring completeness?

A significant number of studies (over 40%) focused exclusively on DO, often due to its strong correlation with aquatic health and regulatory benchmarks. This narrow focus, however, limits comprehensive water quality assessment. Related parameters such as pH, temperature, turbidity, and TDS influence and are influenced by oxygen dynamics, and their absence reduces diagnostic resolution in complex ecosystems. Real-time integration of these sensors enhances multi-variable analysis and improves early detection of pollution events. Their omission reflects both cost limitations and a lack of modular system design in many earlier implementations.

RQ4: Which AI and machine learning approaches have been most effective in previous studies, and how can they be structured for future integration into IoT sensor networks?

AI-enhanced systems using machine learning algorithms—such as regression analysis, neural networks, and ensemble models—have demonstrated strong performance in predictive forecasting. Models achieved R² values up to 0.85 for DO prediction, suggesting high reliability. Integration of AI with IoT architectures enables real-time alerts, automated anomaly detection, and adaptive calibration, reducing both labor and long-term operational costs. Structurally, cloud platforms like AWS, Google Cloud, and ThingSpeak have proven compatible with AI workflows, allowing scalable deployment of trained models. Future systems should standardize data pipelines from sensor to AI model output to maximize utility.

5. Practical Recommendations

Real-time monitoring of water quality is increasingly critical for detecting and mitigating the impacts of dissolved oxygen (DO) depletion and eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. The growing accessibility of low-cost Internet of Things (IoT) technologies presents an opportunity for deploying distributed, automated monitoring systems in both developed and resource-constrained regions. While DO, Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) are key indicators of aquatic ecosystem health, DO sensors in particular remain costly and complex—posing a barrier to widespread adoption. In response, a functional prototype was developed using cost-effective alternatives: sensors for pH, turbidity, total dissolved solids (TDS), and temperature. Although the prototype omits direct DO sensing due to budget limitations, it demonstrates the potential of modular, partial monitoring systems to support environmental diagnostics and serve as scalable frameworks for future enhancement. This section outlines the prototype's system design, functionality, and operational limitations, along with realistic implementation guidelines for researchers, developers, and institutions pursuing low-cost water quality solutions.

5.1. Method

5.1.1. System Architecture

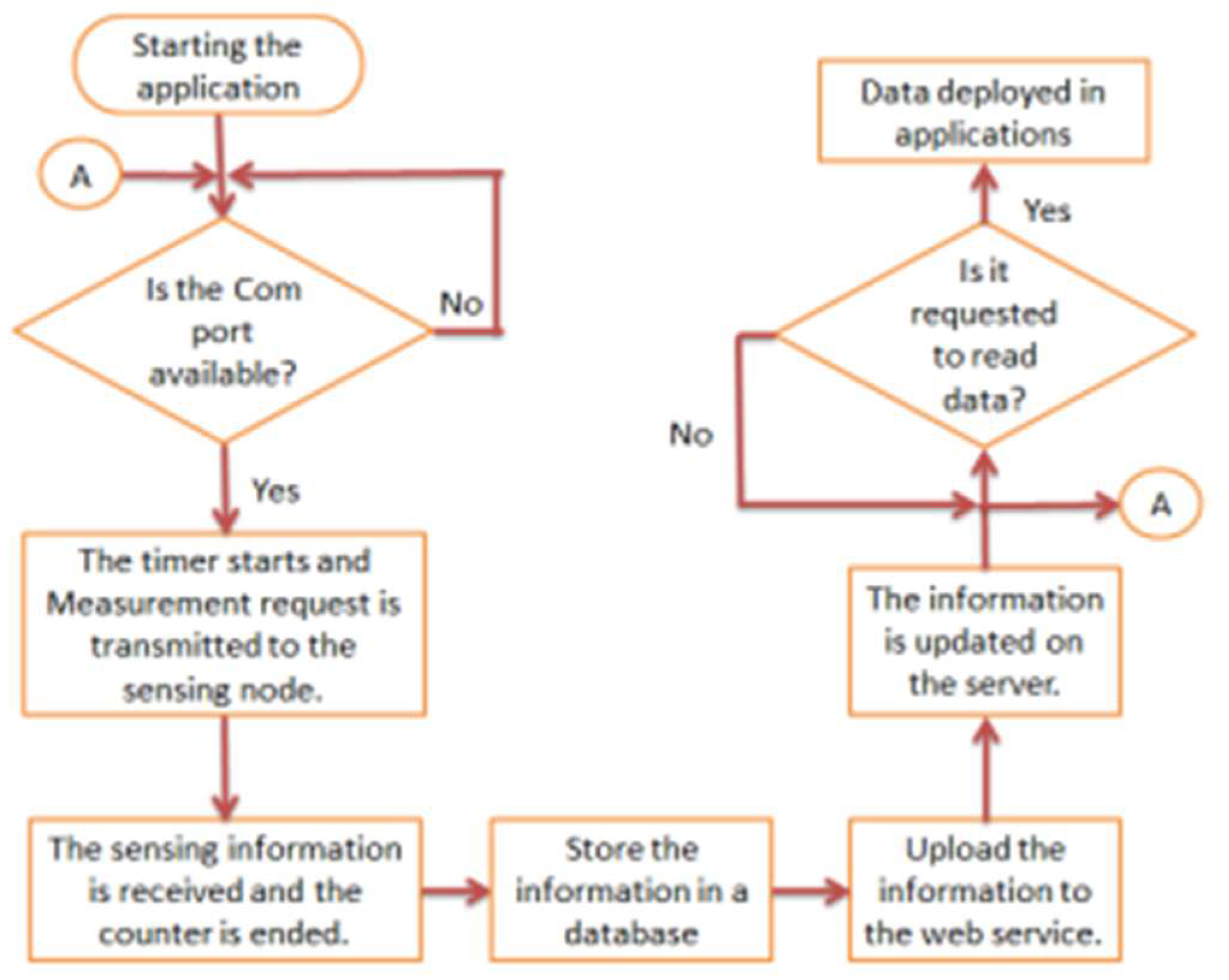

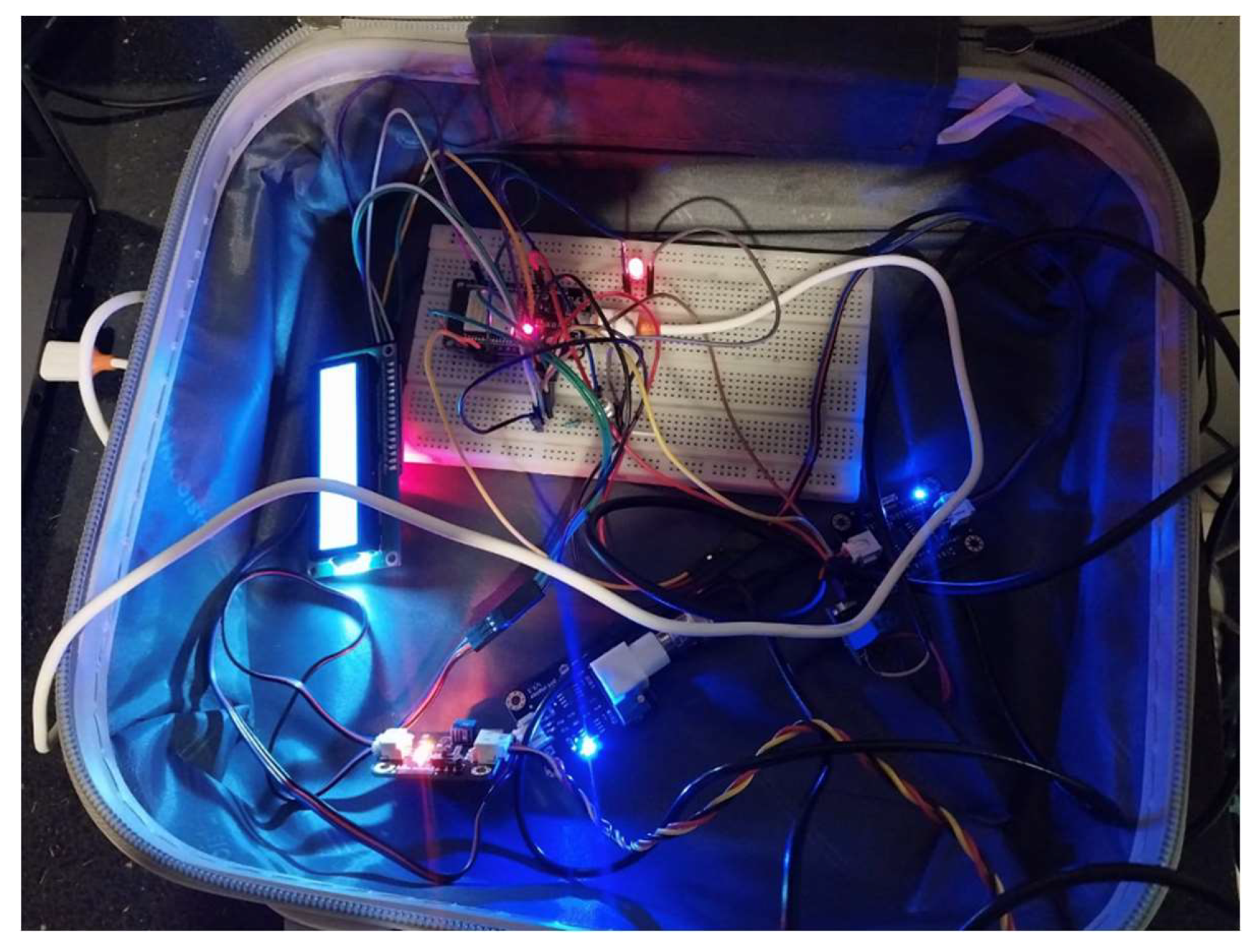

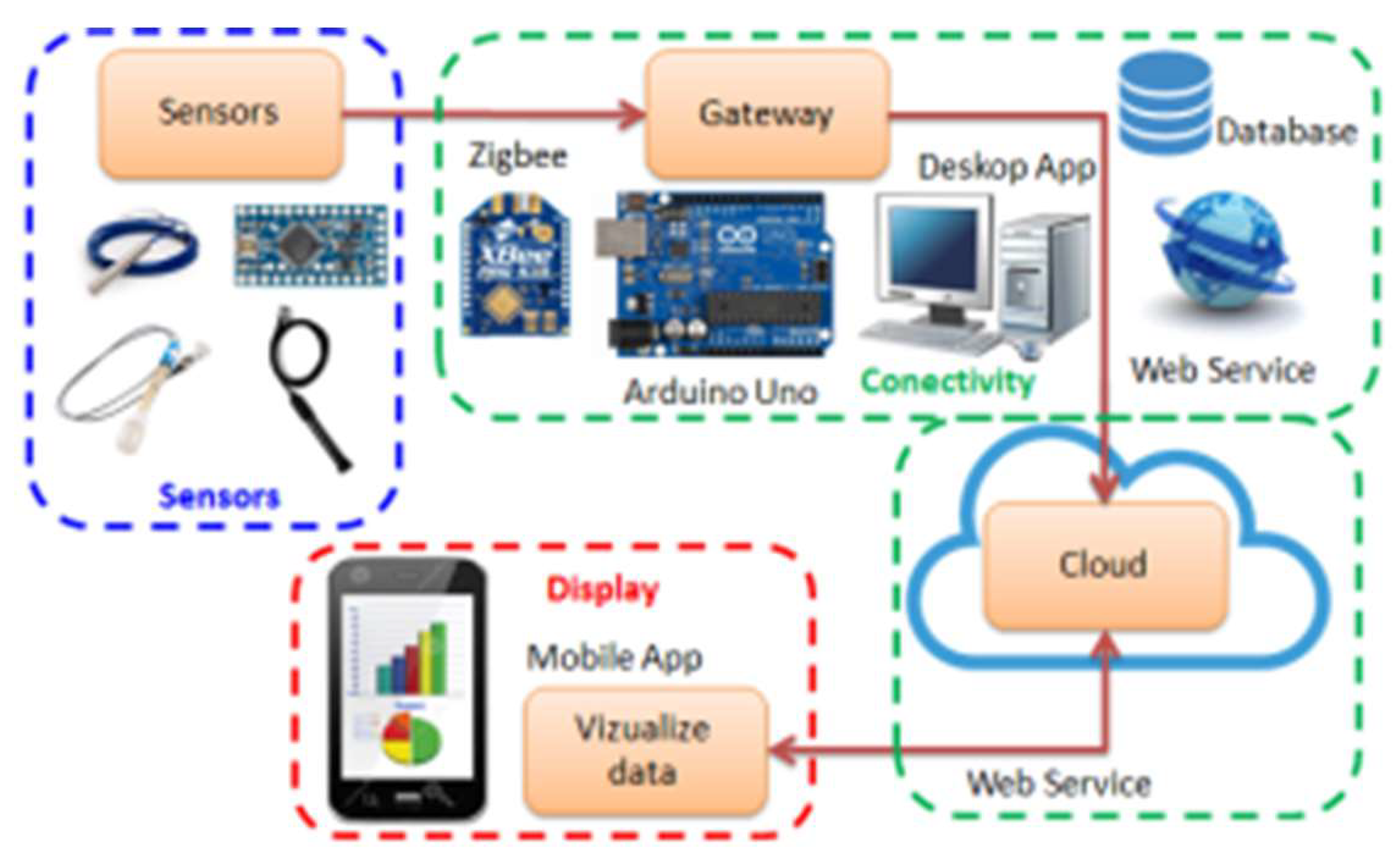

The prototype integrates various technologies to achieve real-time, cloud-connected water quality monitoring. It is composed of three key layers: Sensor Module, Connectivity Framework, and Deployment Interface. Each layer performs a specific function in the data lifecycle, from acquisition to end-user interaction (see

Figure 12).

The system utilizes four sensors: temperature, pH, turbidity, and TDS. These provide insight into chemical characteristics of the water and serve as proxies for parameters such as COD and conductivity. The sensors communicate via UART protocol and are submerged directly into the aquatic environment being monitored. The ESP32 board serves as the core microcontroller, orchestrating data transmission via built-in Wi-Fi using the IEEE 802.11 b/g/n standard. Operating at 2.4 GHz with transmission ranges of 30–90 meters (indoor to outdoor), the ESP32 ensures reliable, real-time communication with cloud services. Sensor data is structured into packets and transmitted through UART to a multiplexer, which sequentially feeds data to the ESP32.

The system employs Blynk IoT Platform for real-time data visualization on web and mobile dashboards. Blynk uses RESTful APIs and secure MQTT/HTTP protocols for seamless device-to-cloud communication. For redundancy, the system also supports local data logging via MySQL and serial interfaces.

Figure 13.

IoT-based water monitoring system architecture.

Figure 13.

IoT-based water monitoring system architecture.

Sensor readings are displayed in real-time through mobile and desktop applications. The ESP32 manages timed sampling and coordination across sensors, transmitting data through an Xbee module when extended range is required. On the receiver side, the data is ingested into a desktop application that writes to a local database and pushes updates to a cloud-based web service. Mobile applications then query this service to retrieve and present the latest measurements to users. The prototype demonstrates how low-cost, modular systems can deliver real-time environmental data and support scalable monitoring frameworks. Despite excluding DO sensors, it establishes an adaptable foundation for future integration of more sophisticated modules such as optical DO sensors, AI-based forecasting, and multi-node networks.

5.1.2. Hardware Design

The hardware configuration of the system is designed to enable real-time monitoring of essential water quality parameters. The setup is built around an ESP32 microcontroller, which functions as both the processor and the central communication hub for data acquisition and transmission.

Several critical components are utilized in the hardware implementation. The pH sensor measures the acidity or alkalinity of the water by producing an analog output, which the ESP32 interprets to determine the pH level—an important factor in maintaining aquatic ecosystem balance. The turbidity sensor detects the cloudiness of water caused by suspended particles, serving as a useful proxy for estimating chemical oxygen demand (COD), which reflects the level of organic pollution. The TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) sensor assesses the concentration of dissolved substances, offering insights into electrical conductivity and overall water quality. Additionally, a temperature sensor is used to continuously monitor water temperature, a parameter that influences both chemical solubility and biological activity within the aquatic environment.

A 16x2 LCD module is integrated into the system and connected to the ESP32. This display allows for immediate, local viewing of real-time data from all sensors, making it possible to monitor water quality even in the absence of an internet connection or external devices. All sensors are submerged directly into the water body being studied. Data is transmitted from each sensor to the ESP32 either through UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) or analog signal lines, depending on the sensor's output format. The ESP32 processes the collected readings and displays them on the LCD screen. Simultaneously, the data is transmitted wirelessly to the Blynk IoT platform, where it can be accessed remotely via mobile devices or a web interface.

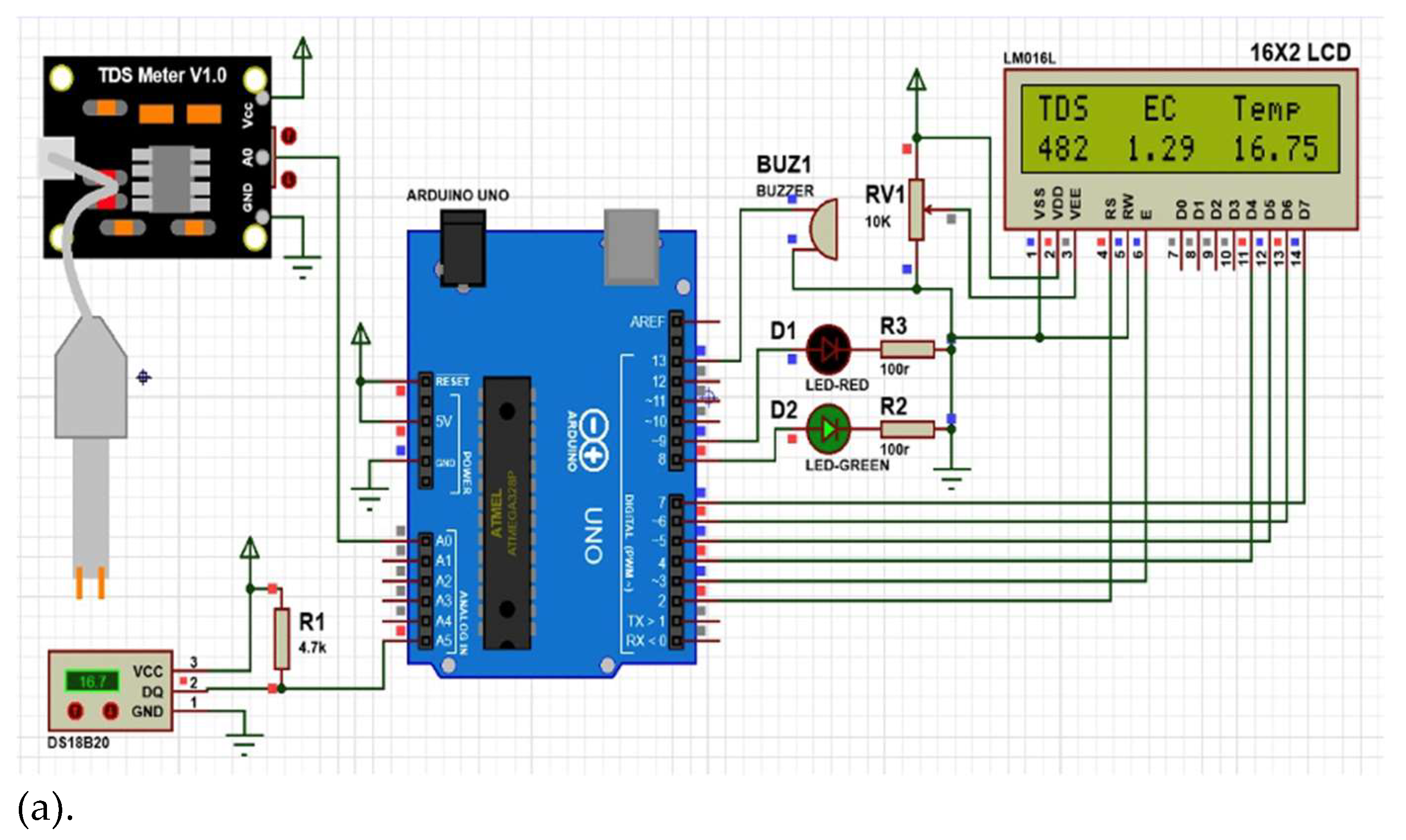

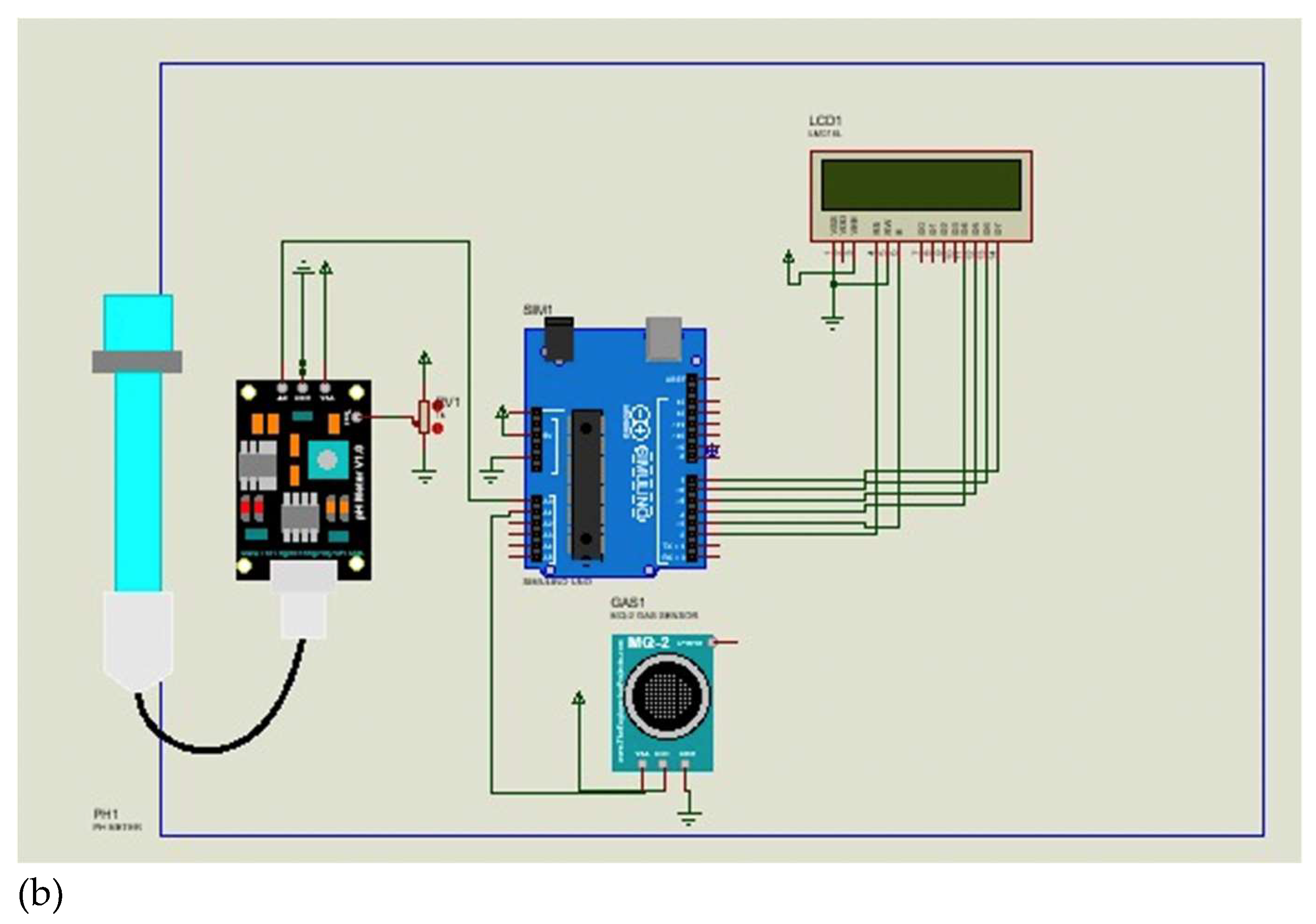

This hardware configuration serves as the operational backbone of the proposed system. It enables efficient, precise, and continuous monitoring of water conditions. Figure 14 illustrates the architecture used for monitoring TDS and temperature. Together, these designs highlight the system’s potential for low-cost, scalable, and reliable environmental monitoring, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

Figure 15.

(a) TDS and temperature monitoring circuit using Arduino Uno and LCD display. (b) pH and turbidity monitoring circuit with Arduino Uno and LCD output.

Figure 15.

(a) TDS and temperature monitoring circuit using Arduino Uno and LCD display. (b) pH and turbidity monitoring circuit with Arduino Uno and LCD output.

5.1.3. Software Implementation

The system firmware was developed using Arduino IDE to program the ESP32 microcontroller. The primary function is to collect data from pH, turbidity, TDS, and temperature sensors, process it, and display it on a 16x2 LCD. Concurrently, the ESP32 sends the data to the Blynk IoT platform via Wi-Fi, enabling real-time remote monitoring through a mobile or web app. Blynk offers a user-friendly dashboard for visualization using graphs, value displays, and alerts, with compatibility for Android and iOS.

The software workflow, illustrated in

Figure 16, initializes sensors and LCD after boot. It connects to Wi-Fi and authenticates with Blynk servers. The system then reads sensor data at set intervals, displays it on the LCD, and transmits it to the cloud in real time. Blynk also stores this data for historical analysis or alert triggering.

Figure 16.

Software flowchart showing data acquisition and transmission process.

Figure 16.

Software flowchart showing data acquisition and transmission process.

Figure 17.

Final hardware implementation of the prototype system using ESP32, sensors, and LCD display.

Figure 17.

Final hardware implementation of the prototype system using ESP32, sensors, and LCD display.

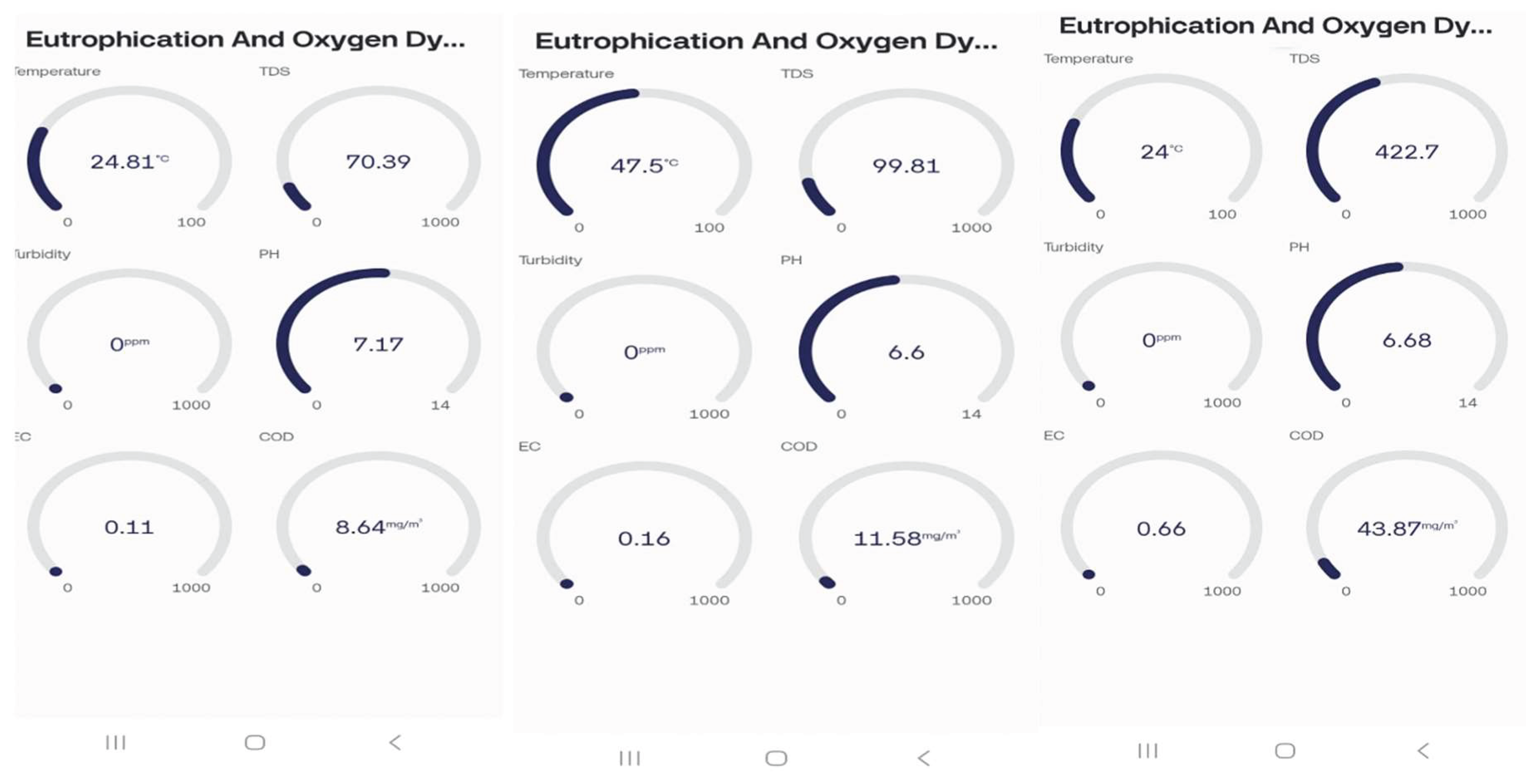

5.1.4. Experimental Results

The system was deployed on a local network and tested under various water conditions to validate performance. It consistently transmitted accurate, real-time data with minimal delay. Figure18 shows stable tap water with TDS at 70.39 ppm, pH at 7.17, and COD at 8.64. the hot tap water led to increased COD (11.58) and TDS (99.81 ppm), with pH dropping to 6.6. The result of adding salt, spiking TDS to 422.7 ppm and COD to 43.87, confirming the system’s responsiveness to dissolved matter changes.

Figure 18.

Dashboard output for normal tap water conditions. (b) Sensor response to hot tap water. (c) Effects of adding salt to tap water on water quality parameters.

Figure 18.

Dashboard output for normal tap water conditions. (b) Sensor response to hot tap water. (c) Effects of adding salt to tap water on water quality parameters.

5. Conclusions

This study offers a dual contribution to the field of aquatic environmental monitoring: a systematic review of IoT-enabled water quality systems focused on eutrophication, and the design and validation of a low-cost, functional prototype for real-time monitoring. Through the rigorous analysis of 28 peer-reviewed studies spanning 2015 to 2025, key trends, technologies, and research gaps were identified. Dissolved Oxygen (DO) emerged as the most widely monitored parameter, recognized for its strong correlation with ecosystem health and regulatory standards. However, the analysis also revealed a significant underrepresentation of complementary parameters such as BOD, COD, pH, turbidity, temperature, and TDS—factors equally vital in diagnosing the biochemical complexity of eutrophic environments.

One of the central challenges highlighted was the reduced reliability of sensor performance in cold, turbid, and sediment-laden waters—conditions prevalent in many eutrophic ecosystems. While optical DO sensors demonstrated the highest accuracy (90–96%), BOD and COD sensors showed moderate but less consistent performance. These results underscore the necessity of robust calibration, nano-coatings, and modular system design for future deployments. Additionally, although artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) remain underutilized in field applications, they show exceptional promise in forecasting pollution events, supporting automated decision-making, and enhancing data interpretation, with reviewed models achieving R² scores as high as 0.85 for DO prediction.

To bridge the gap between conceptual research and applied practice, this study developed and tested a low-cost, scalable IoT-based circuit using the ESP32 microcontroller and open-source software. While financial limitations precluded the inclusion of a DO sensor, the system successfully monitored pH, turbidity, temperature, and TDS with real-time visualization via the Blynk platform. Experimental results confirmed the system’s sensitivity to water quality changes, validating its feasibility for deployment in resource-constrained environments. The prototype’s modular design lays the groundwork for future integration of additional sensors and AI-based forecasting models, offering a pathway toward more comprehensive and autonomous environmental monitoring solutions.

References

- Alexandrov, M., Ichida, E., Nishimura, T., Aoki, K. and Ishida, T., 2014. Development of an automated asbestos counting software based on fluorescence microscopy. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187(1). [CrossRef]

- Anagnostou, E., Gianni, A. and Zacharias, I., 2017. Ecological modeling and eutrophication—A review. Natural Resources Modeling. [CrossRef]

- Burkholder, J.M. et al., 2022. Classic indicators and diel dissolved oxygen vs. trend analysis in assessing eutrophication of potable-water reservoirs. Ecological Applications. [CrossRef]

- Cairone, S. et al., 2024. Revolutionizing wastewater treatment toward circular economy and carbon neutrality goals. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 63, 105486. [CrossRef]

- Camacho Suarez, V.V. et al., 2019. Evaluation of a coupled hydrodynamic-closed ecological cycle approach for modelling dissolved oxygen in surface waters. Environmental Modelling & Software, 119, pp.242–257. [CrossRef]

- Camacho Suarez, V.V. et al., 2019. Evaluation of a coupled hydrodynamic-closed ecological cycle approach for modelling dissolved oxygen in surface waters. Environmental Modelling & Software, 119, pp.242–257. [CrossRef]

- Camacho Suarez, V.V. et al., 2021. Influence of nutrient enrichment on temporal and spatial dynamics of dissolved oxygen within northern temperate estuaries. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment.

- Chabalala, K., Boyana, S., Kolisi, L., Thango, B., & Lerato, M. (2024). Digital technolo-gies and channels for competitive advantage in SMEs: A systematic review. Available at SSRN 4977280.

- Chafa, A.T., Chirinda, G.P. and Matope, S., 2022. Design of a real-time water quality monitoring and control system using Internet of Things (IoT). Cogent Engineering, 9(1), p.2143054. [CrossRef]

- Coffin, M.R.S. et al., 2018. An empirical model using dissolved oxygen as an indicator for eutrophication at a regional scale. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 133, pp.261–270. [CrossRef]

- Crossman, J. et al., 2021. A new, catchment-scale integrated water quality model of phosphorus, dissolved oxygen, biochemical oxygen demand and phytoplankton: INCA-Phosphorus Ecology (PEco). Water, 13(5), 723. [CrossRef]

- Daconte, A. et al., 2024. Preliminary results of an IoT-based prototype monitoring system for physicochemical parameters and water level in an aquifer: Case of Santa Marta, Colombia. Procedia Computer Science, 231, pp.478–483. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., Khondakar, K.R., Mazumdar, H., Kaushik, A. and Mishra, Y.K., 2025. AI and IoT: Supported sixth generation sensing for water quality assessment to empower sustainable ecosystems. ACS ES&T Water, 5(2), pp.490–510.

- Devlin, M. and Brodie, J. (2023) 'Nutrients and eutrophication', in Reichelt-Brushett, A. (ed.) Marine pollution - monitoring, management and mitigation. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 75-100. [CrossRef]

- Dladla, V.M.N., & Thango, B.A. (2025). Fault Classification in Power Transformers via Dissolved Gas Analysis and Machine Learning Algorithms: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 15(5), 2395.

- Dorlikar, A.V., 2016. Correlation study of zooplankton diversity, species richness and physico-chemical parameters of Ghodazari Lake (Maharashtra). International Journal of Researches in Biosciences, Agriculture & Technology, 4(3), pp.49–54. [CrossRef]

- Ebron, J.G., Rivero, G.T. and Ang, J.V.R., 2024. Integrated Internet of Things and AI for real-time water quality monitoring in Laguna Lake. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 113, pp.163–168. [CrossRef]

- Elnady, M.A., Abd Elwahed, R.K. and Gad, G.H., 2017. Evaluating oxygen dynamics, water quality parameters and growth performance of Nile Tilapia by applying different dietary nitrogen levels. Journal of American Science, 13(1), pp.107–115. [CrossRef]

- Evrendilek, F. and Karakaya, N., 2013. Monitoring diel dissolved oxygen dynamics through integrating wavelet denoising. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 186, pp.1583–1593. [CrossRef]

- Febrianto, M.A., 2024. Smart monitoring system for quality assessment of batik industry wastewater through IoT and machine learning classification. In: Proc. 2024 Int. Conf. Artificial Intelligence and Mechatronics Systems (AIMS). pp.1–6.

- Felemban, E., Shaikh, F.K., Qureshi, U.M., Sheikh, A.A. and Qaisar, S.B., 2015. Underwater sensor network applications: A comprehensive survey. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks, 11(5), pp.1–15. [CrossRef]

- Geetha, S. and Gouthami, S.J.S.W., 2016. Internet of things enabled real time water quality monitoring system. Smart Water, 2, pp.1-19.

- Gulati, S., 2024. Application of Artificial Intelligence in Wastewater Treatment. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.A. et al., 2015. Optimizing recovery of eutrophic estuaries: Impact of destratification and re-aeration on nutrient and dissolved oxygen dynamics. Ecological Engineering, 75, pp.470–483. [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, A. et al., 2014. Dissolved oxygen in a temperate estuary: The influence of hydro-climatic factors and eutrophication at seasonal and inter-annual time scales. Estuaries and Coasts. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.B.E. et al., 2024. From measured pH to hidden BOD: Quasi real-time estimation of key indirect water quality parameters through direct sensor measurements. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Congress on Information and Communication Technology (ICICT 2024, Volume 10). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J. et al., 2024. Effectiveness of chemical oxygen demand as an indicator of organic pollution in aquatic environments. Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Research. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C. and Gil, K., 2023. Constructing an Internet of Things wetland monitoring device and a real-time wetland monitoring system. Membrane and Water Treatment, 14(4), pp.155–162. [CrossRef]

- Kelechi, A.H. et al., 2021. Design and implementation of a low-cost portable water quality monitoring system. Computers, Materials & Continua, 69(2). [CrossRef]

- Kgakatsi, M., Galeboe, O.P., Molelekwa, K.K., & Thango, B.A. (2024). The Impact of Big Data on SME Performance: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 4(4), 632-695.

- Khanyi, M.B., Xaba, S.N., Mlotshwa, N.A., Thango, B., & Matshaka, L. (2024). A Roadmap to Systematic Review: Evaluating the Role of Data Networks and Application Programming Interfaces in Enhancing Operational Efficiency in Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability, 16(23), 10192.

- Kwon, D.H. et al., 2023. Inland harmful algal blooms (HABs) modeling using internet of things (IoT) system and deep learning. Environmental Engineering Research, 28(1), p.210280. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X. et al., 2024. Dissolved oxygen concentration prediction in the Pearl River Estuary with deep learning for driving factors identification: Temperature, pH, conductivity, and ammonia nitrogen. Water, 16(3090). [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. et al., 2016. Dynamics of dissolved oxygen and the affecting factors in sediment of polluted urban rivers under aeration treatment. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, 227(172). [CrossRef]

- Ma, R. et al., 2024. Spatiotemporal variations and controlling mechanism of low dissolved oxygen in a highly urbanized complex river system. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 52. [CrossRef]

- Maju, N.A.H., Mansor, H., Gunawan, T.S. and Ahmad, R., 2022. The development of water pollution detector using conductivity and turbidity principles. IIUM Engineering Journal, 23(2). [CrossRef]

- Molete, O.B., Mokhele, S.E., Ntombela, S.D., & Thango, B.A. (2025). The Impact of IT Strategic Planning Process on SME Performance: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 5(1), 2.

- Morales, A.S. et al., 2023. Internet of Things experimental platform for real-time water monitoring: A case study of the Araranguá River Estuary. Acta Scientiarum. Technology, 45, e58368. [CrossRef]

- Msane, M.R., Thango, B.A., & Ogudo, K.A. (2024). Condition Monitoring of Electrical Transformers Using the Internet of Things: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 14(21), 9690.

- Ngcobo, K., Bhengu, S., Mudau, A., Thango, B., & Lerato, M. (2024). Enterprise data management: Types, sources, and real-time applications to enhance business performance-a systematic review. Systematic Review| September.

- Nguyen, T.T.N. et al., 2019. Nutrient dynamics and eutrophication assessment in the tropical river system of Saigon – Dongnai (Southern Vietnam). Science of the Total Environment, 653, pp.370–383. [CrossRef]

- Nishan, R.K. et al., 2024. Development of an IoT-based multi-level system for real-time water quality monitoring in industrial wastewater. Discover Water, 4. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, V.H. et al., 2019. Modeling the impact of extreme river discharge on the nutrient dynamics and dissolved oxygen in two adjacent estuaries (Portugal). Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 7(11), p.412. [CrossRef]

- Piestrzyńska, M., Dominik, M., Kosiel, K., Janczuk-Richter, M., Szot-Karpińska, K., Brzozowska, E., Shao, L., Niedziółka-Jonsson, J., Bock, W.J. and Śmietana, M. (2019) 'Ultrasensitive tantalum oxide nano-coated long-period gratings for detection of various biological targets', Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 133, pp. 8-15.

- Pingilili, A., Letsie, N., Nzimande, G., Thango, B., & Matshaka, L. (2025). Guiding IT Growth and Sustaining Performance in SMEs Through Enterprise Architecture and Information Management: A Systematic Review. Businesses, 5(2), 17.

- Sari, N. et al., 2024. Design of IoT-based monitoring system for temperature and dissolved oxygen levels in catfish aquaculture pond water. International Journal of Reconfigurable and Embedded Systems, 13(3), pp.687–698. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.S.B. et al., 2024. Hypertuning-based ensemble machine learning approach for real-time water quality monitoring and prediction. Applied Sciences, 14(8622). [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.B. et al., 2024. AI-driven modelling approaches for predicting oxygen levels in aquatic environments. Journal of Water Process Engineering, 66. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, Y. et al., 2024. Design and development of dynamic water quality monitoring system for aquaculture. In: Proc. 2nd Int. Conf. Intell. Data Commun. Technol. Internet Things (IDCIoT-2024). [CrossRef]

- Stoicescu, S.-T., Lips, U. and Liblik, T., 2019. Assessment of eutrophication status based on sub-surface oxygen conditions in the Gulf of Finland (Baltic Sea). Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, p.54. [CrossRef]

- Suriasni, P.A. et al., 2024. IoT water quality monitoring and control system in moving bed biofilm reactor to reduce total ammonia nitrogen. Sensors, 24(494). [CrossRef]

- Syed Taha, S.N. et al., 2024. Evaluation of LoRa network performance for water quality monitoring systems. Applied Sciences, 14, 7136. [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S. and Nooraninejad FardArani, Z., 2024. AquaticSafe Sentinel: An edge-based IoT-powered predictive system for continuous dissolved oxygen surveillance in aquaculture. In: Proc. 13th IEEE Int. Conf. Commun. Syst. Netw. Technol. (CSNT 2024).

- Teklehaimanot, G.Z., Kamika, I., Coetzee, M.A.A. and Momba, M.N.B., 2015. Seasonal variation of nutrient loads in treated wastewater effluents and receiving water bodies in Sedibeng and Soshanguve, South Africa. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187(595). [CrossRef]

- Terry, J.A., Sadeghian, A. and Lindenschmidt, K.-E., 2017. Modelling dissolved oxygen/sediment oxygen demand under ice in a shallow eutrophic prairie reservoir. Water, 9(2), p.131. [CrossRef]

- Thango, B.A., & Obokoh, L. (2024). Techno-Economic Analysis of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems for Power Interruptions: A Systematic Review. Eng, 5(3), 2108-2156.

- Thobejane, L.T., & Thango, B.A. (2024). Partial Discharge Source Classification in Power Transformers: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6097.

- Xiong, J. et al., 2021. Role of Sponge City Development in China’s battle against urban water pollution: Insights from a transjurisdictional water quality management study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 294. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. and Xu, Y.J., 2014. Rapid field estimation of biochemical oxygen demand in a subtropical eutrophic urban lake with chlorophyll a fluorescence. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187:4171. [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, T. et al., 2017. Anthropogenic changes in a confined groundwater flow system in the Bangkok Basin, Thailand. Hydrological Processes, 25(17), pp.2734–2741. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).