1. Introduction

The global transition to EVs is a critical strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable transportation. According to the International Energy Agency, EV sales reached 14 million units in 2023, necessitating a robust charging infrastructure [

1]. Rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations present a promising avenue for leveraging renewable energy to meet the growing demand for EV charging while reducing dependence on fossil fuel-based grids. However, integrating these systems into distribution networks introduces challenges that include power quality degradation, grid instability, and variability in solar generation due to environmental factors [

2]. Existing EV charging infrastructures are categorised into three distinct types: grid-connected chargers, standalone solar chargers, and hybrid systems [

3]. Grid-connected systems often exacerbate peak load demands, leading to voltage fluctuations and harmonic distortions. Standalone solar chargers, while sustainable, suffer from intermittency and limited scalability. Hybrid systems combining solar power and ESS show promise but require sophisticated management to optimise power flow and maintain grid stability [

4]. Despite advancements in present systems, there is a lack of real-time environmental adaptability and efficient power conversion. Environmental factors, such as solar irradiance, temperature, and shading, significantly impact solar generation; yet, most systems rely on static models that fail to account for dynamic conditions [

5]. Moreover, conventional DC-DC converters used in these systems often operate inefficiently under varying load conditions, resulting in increased power losses and reduced system reliability. To solve these challenges, there is a need for intelligent control systems that integrate IoT-based monitoring, advanced control algorithms, and high-efficiency power electronics to ensure a stable, scalable, and sustainable EV charging infrastructure.[

6].

Recent Trends in RES-Integrated Modern Grids

Gumus et al. [

7] examined the challenges associated with the incorporation of Renewable Energy Sources (RES) into the grid. The unpredictable nature of power generation from these sources has an adverse impact on grid frequency and voltage. Additionally, reverse power flow issues may arise in distribution systems. High installation and maintenance costs further limit the widespread adoption of these technologies. To address these challenges, the implementation of advanced algorithms with real-time forecasting capabilities, enabled by IoT, is necessary for accurate generation prediction. The use of smart grids with local control mechanisms can enhance the stability and reliability of the grid. Moreover, hybrid systems that combine solar, wind, and battery storage can significantly improve overall system stability.

Kiasari et al. [

8] explored the challenges associated with battery storage systems, particularly the degraded battery performance over time, which adversely affects the reliability of the overall system. This degradation can lead to reduced efficiency and increased maintenance costs. To address these issues, the development and implementation of advanced battery management systems (BMS) are crucial. These systems are designed to meticulously control the charge and discharge cycles, thereby extending battery life and enhancing performance. Advanced BMS can also incorporate real-time monitoring and predictive analytics to identify and mitigate potential issues. Furthermore, integrating these systems with IoT technologies can provide enhanced data collection and analysis, leading to more informed decision-making and improved operational efficiency. The adoption of such advanced management systems is essential for ensuring the long-term viability and reliability of battery storage solutions.

Oliveira et al. [

9] investigated the impact of integrating nonlinear EV loads and the unpredictable nature of RES on the power quality. These integrations can lead to voltage sags and swells, harmonic distortion, and frequency instability, which pose significant challenges to maintaining a stable and reliable power grid. To mitigate these issues, the use of multilevel inverters (MLIs) with advanced modulation techniques was proposed to reduce harmonic distortion effectively. Additionally, the deployment of Flexible AC Transmission Systems (FACTS) devices, including active filters such as shunt and series compensators, can address power quality issues by providing dynamic voltage support and mitigating harmonics. These technologies are essential for enhancing the overall stability and reliability of the power grid in the face of increasing integration of EV loads and RES.

Ullah et al. [

10] examined the challenges posed by the large-scale integration of EVs into the power grid. Sudden EV charging can strain transformers, leading to thermal overloads and reduced equipment lifespan. Additionally, the unpredictable load profiles of EVs further complicate demand forecasting and load balancing. To address these issues, bidirectional charging and blockchain-based control systems were proposed to enhance grid stability. Bidirectional charging enables both Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) and Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) technologies. However, V2G and G2V technologies face several challenges. These include the need for communication protocols, interoperability standards, and the management of battery degradation due to frequent charge-discharge cycles. To overcome these challenges, advanced algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) methods are being developed to optimise V2G operations, ensuring efficient energy management. Furthermore, the integration of blockchain technology can enhance the security and overall performance of the transmission system by facilitating real-time monitoring and control of energy flows. By addressing these challenges, the effective implementation of V2G and G2V technologies can significantly improve grid resilience and reliability.

This study introduces an IoT-based CBMS for rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations. The CBMS integrates IoT algorithms for real-time environmental monitoring and adaptive energy management, coupled with advanced DC-DC bidirectional converters for efficient power distribution. The system aims to enhance grid stability and provide a sustainable solution for EV charging infrastructure.

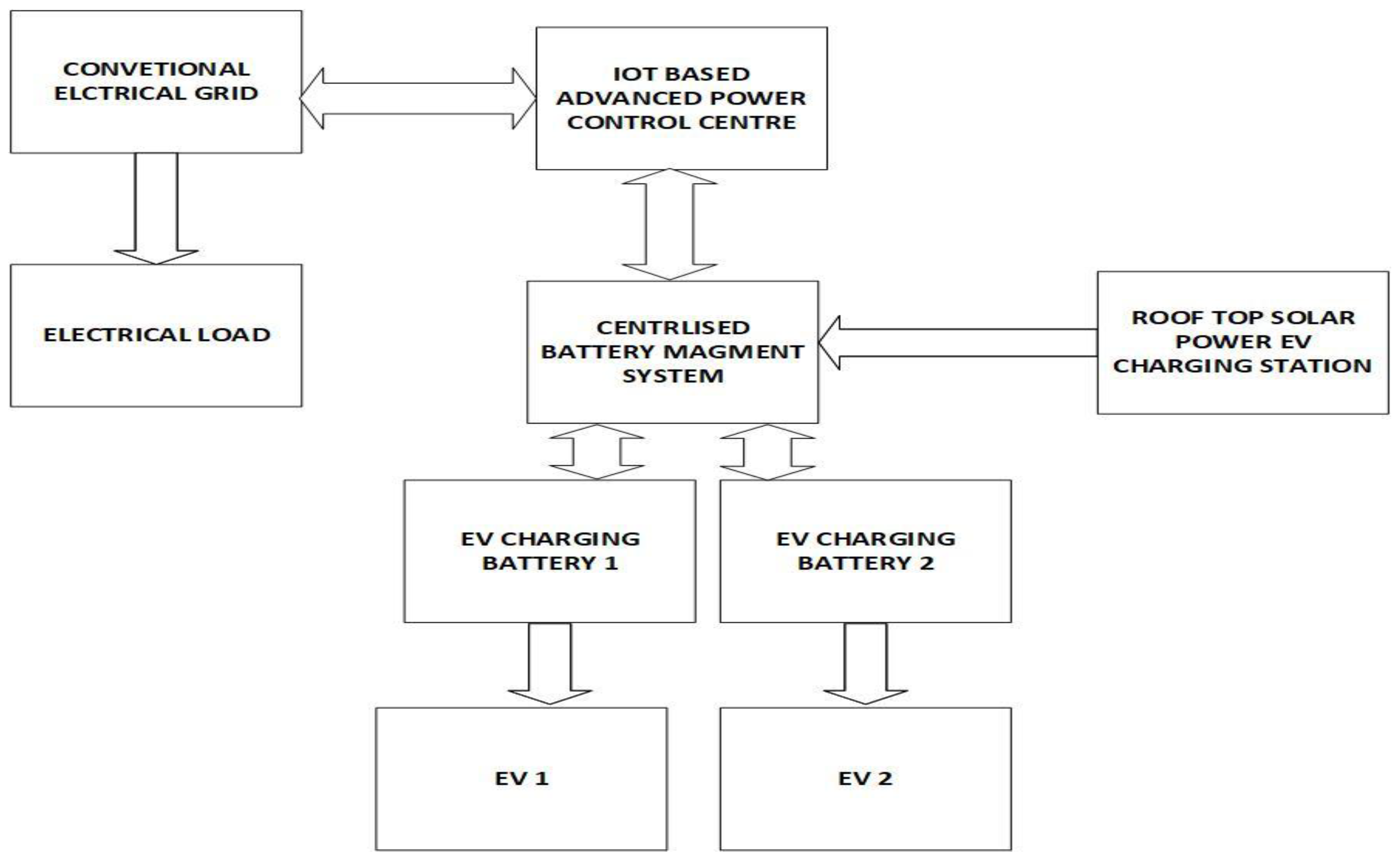

Figure 1 shows the block diagram of the proposed IoT-based CBMS strategies for EV charging stations, which help optimise Power flows and balance grid demand. It utilises advanced control algorithms, real-time monitoring, and decision-making to improve grid efficiency and stability.

2. Challenges of Renewable Energy Integration

Solar PV systems depend on weather conditions. This makes their power output inconsistent and unpredictable. These fluctuations can cause voltage and frequency instability in the grid, making it harder to balance electricity supply and demand. For example, a sudden drop in solar irradiance, such as when clouds pass, can reduce power output by up to 70% within minutes, putting stress on grid operations [

11]. Inverter-based RES have replaced traditional synchronous generators. This makes it more vulnerable to rapid frequency changes because solar inverters do not naturally support frequency stability like conventional generators [

12]. The decentralised nature of Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) such as rooftop solar and battery storage, introduce further complexities. Bidirectional power flows from DERs can lead to voltage imbalances, reverse power flows, and transformer overloading into distribution networks. For example, uncoordinated EV charging during peak hours can increase demand by 20–30%, potentially causing voltage sags and equipment stress [

13]. Addressing challenges such as ESS, the integration of RES, and power quality are essential for the effective implementation of modern grids as solutions. ESS enhance grid capacity by storing surplus power generated from RES and releasing it during periods of high demand or low availability. This capability stabilises the grid, reduces the impact of RES variability, and ensures a reliable power supply [

14]. The integration of RES into the grid is important for transitioning to a sustainable energy future. Advanced forecasting and distributed energy management systems can enhance the prediction and control of renewable energy sources (RES) output, thereby balancing supply and demand in real-time. This integration not only enhances grid stability but also reduces reliance on fossil fuels, contributing to decarbonisation efforts [

15]. Improvements in power quality, such as mitigating harmonic distortions and voltage fluctuations, are crucial for maintaining grid efficiency and reliability. Poor power quality can damage equipment and reduce efficiency [

16]. Addressing these challenges is important because they are interconnected and affect the overall performance and sustainability of smart grids. By resolving issues related to battery storage, RES integration, and power quality, a more resilient, efficient, and sustainable energy system can be developed, supporting the global push toward decarbonisation and enhancing the reliability of power supply for consumers.

A combination of RES generation and a battery storage system can maximise RES utilisation and system performance. RES mainly depend on environmental factors such as geographic location, solar irradiation, temperature, wind speed, daily weather patterns, season, time of the year, and shading. They are also dependent on the technical factors like efficiency of power electronics converters and maximum power point tracking (MPPT) [

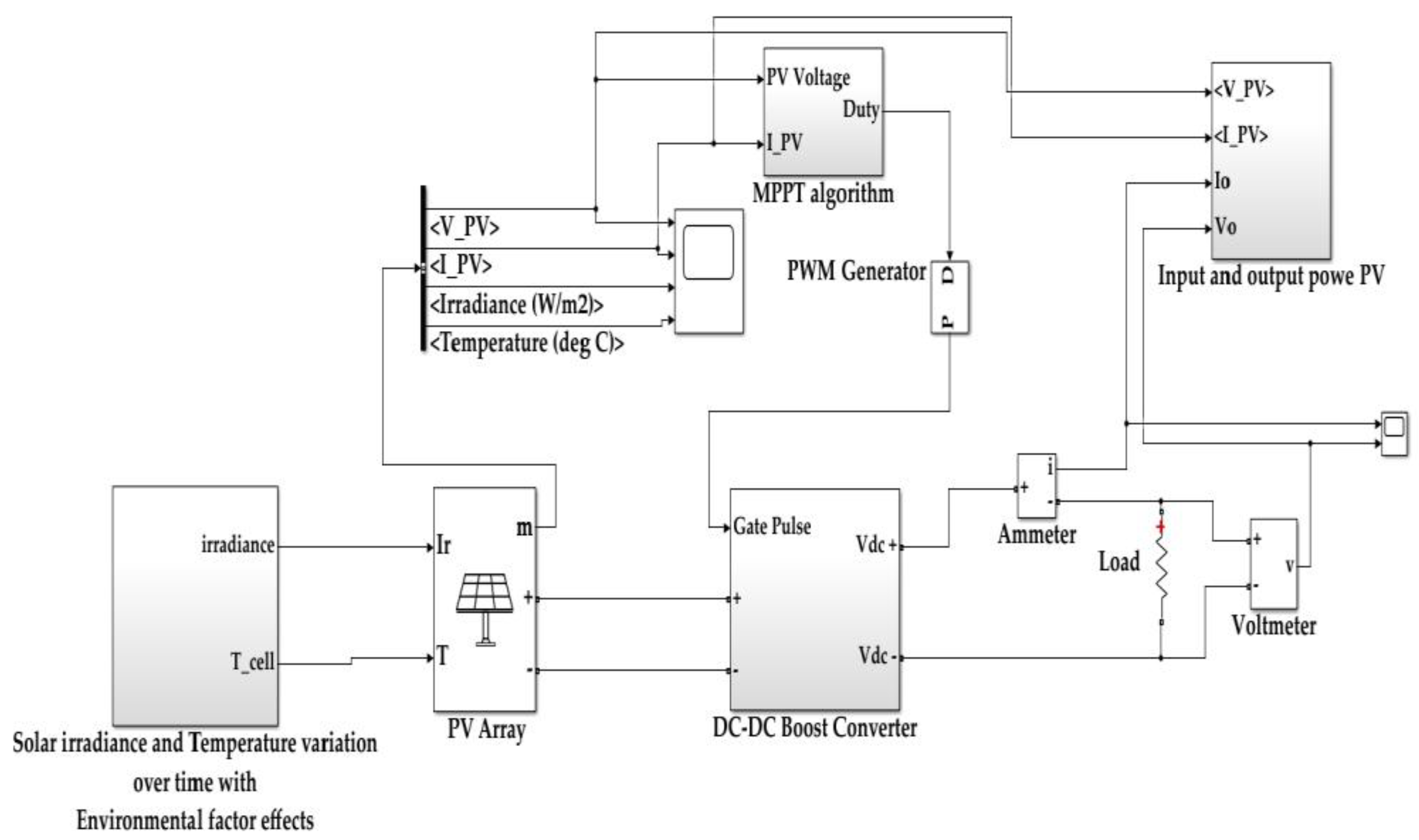

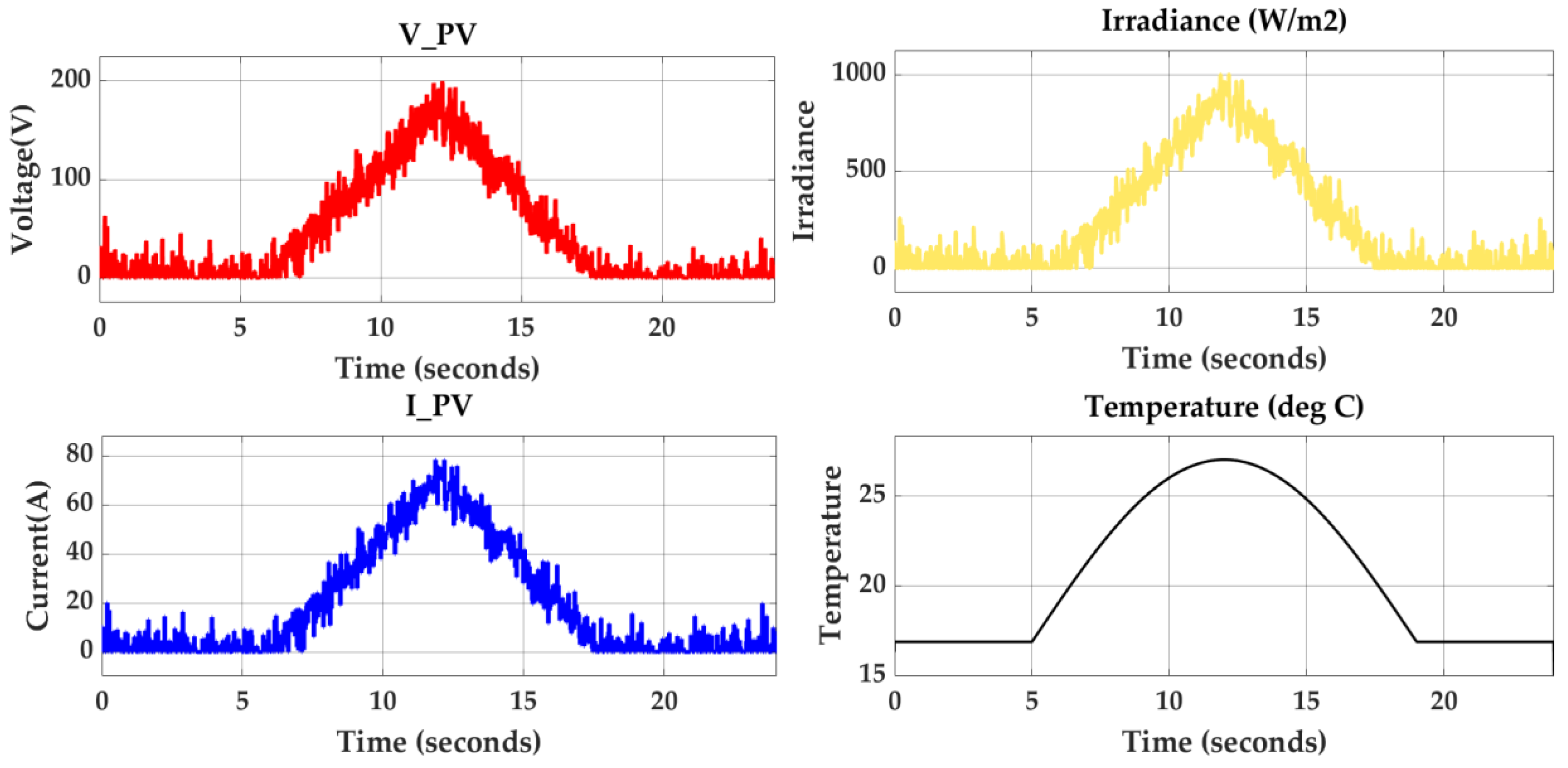

17]. This study demonstrates how solar generation systems respond to the above factors. To study the variation, a MATLAB 2024b simulation of 20 KW solar generation is developed.

Figure 2 shows the simulation diagram of the system.

Table 1 shows the simulation parameters used for solar generation.

2.1. Solar Irradiance [18]

Solar irradiance is the power per unit area received from the sun in the form of electromagnetic radiation. The amount of solar irradiance directly influences the amount of power generated by a solar cell. Higher irradiance means more photons are available to be converted into electrical energy, increasing the output power. Rainfall can reduce irradiance and leave behind water droplets or dirt streaks on panels, causing optical losses. Snow that falls on panels acts as a physical barrier to sunlight. Unless it melts or slides off, it can lead to complete generation loss.

The relation between power and solar irradiation can be expressed as:

where,

Latitude affects both the duration of daylight and the angle at which the sun's rays strike the Earth. Regions at higher latitudes typically experience less sunlight, and areas at lower latitudes more sunlight. Seasonal variations can also impact daily power generation due to changes in daylight and solar angles.

2.2. Ambient Temperature (T) [19]

Ambient temperature is the temperature of the environment surrounding the solar panel. As the temperature increases, the voltage of the PV module decreases, reducing cell efficiency. To describe the impact of temperature on the efficiency of the PV module, a temperature coefficient is defined. Wind speed affects the cooling of panels, modifying the cell temperature. The output voltage of a PV module at a specific temperature can be estimated as

where,

denotes the open circuit voltage at ambient temperature

, and

and

These are the open-circuit voltage and temperature at Standard Test Conditions (STC), respectively. At 250 °C and a temperature

. coff of 0.33, the above equation can be written as:

Relative humidity (RH) causes light scattering and transmission loss. Air quality issues, such as aerosols and dust, increase atmospheric attenuation, reducing irradiance. Soiling from dust on panels also reduces transmission. Combining these factors, the comprehensive PV output equation considering all the environmental effects is expressed as [

20]

where,

Ls, Sf: Soiling and shading losses,

k⋅RH: Humidity-related losses.

Figure 3 shows how these factors affect the solar generation.

DC-DC converters are important for integrating RES with ESS. They can control the variable nature of solar power by efficiently transferring power between solar panels and batteries [

21]. Non-isolated three-port converters are especially useful because they reduce the number of components and improve system efficiency. Additionally, advanced configurations such as multi-port converters with differential power processing capabilities allow for effective regulation of active power among PV, batteries, and the grid [

22]. These can improve power flow and reduce losses. The need for such converters is underscored by the growing demand for reliable and efficient energy solutions in smart grids and EVs, where reducing switching losses and increasing power transfer efficiency are high. Thus, DC-DC converters are essential for achieving sustainable energy integration in modern systems [

23].

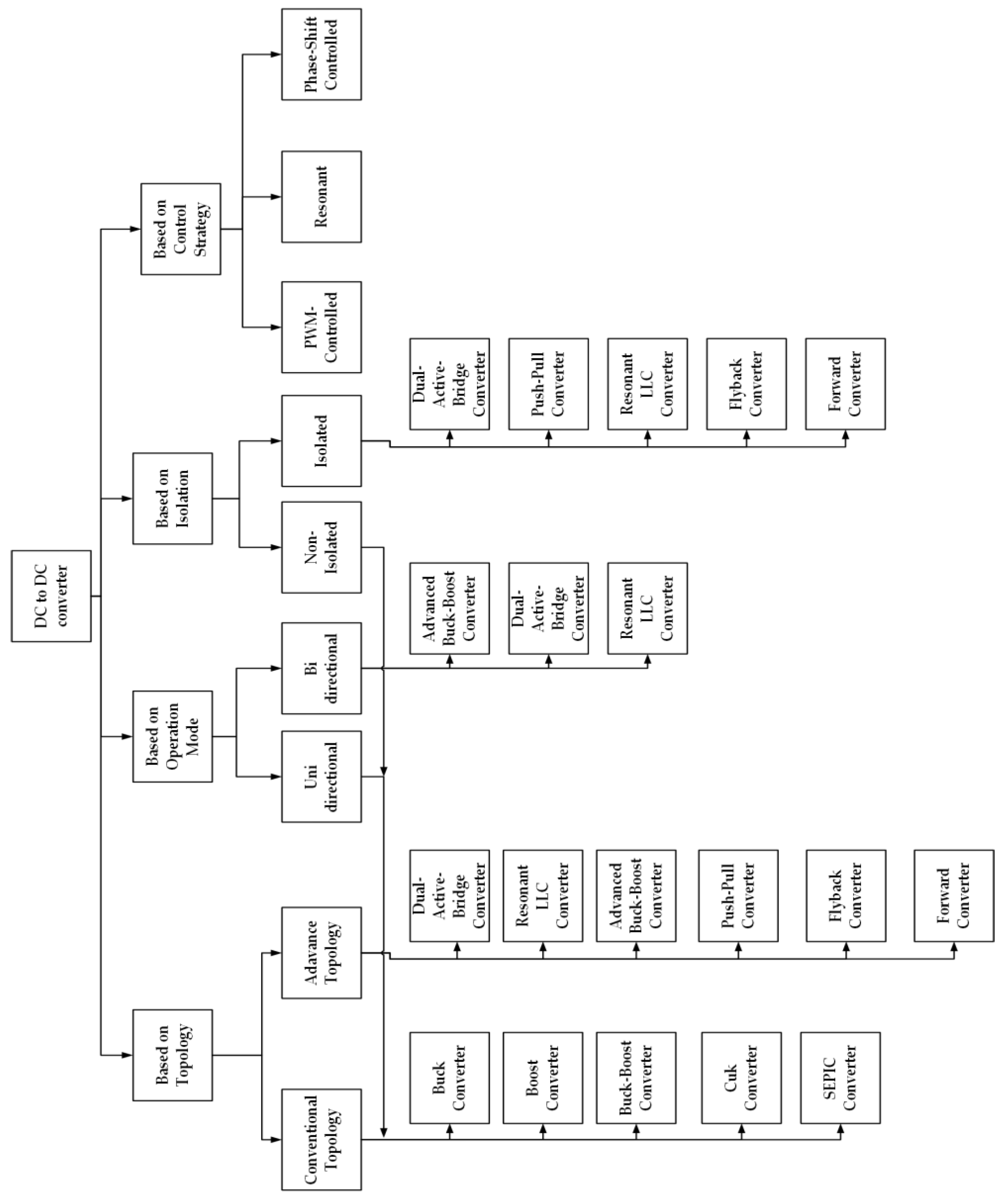

3. Role of DC-DC Converters

DC-DC converters are power electronic devices that are essential for converting a DC input voltage to a desired DC output voltage. They play a crucial role in various applications such as RES, EV, and consumer electronics. These converters utilise components such as inductors and capacitors to store and transfer power. Configurations such as buck, boost, and buck-boost topologies each offer unique advantages and applications [

24]. The basic structure of a DC-DC converter typically includes inductors and capacitors for energy storage and filtering, along with switching elements that regulate the voltage conversion process. These converters are widely used in applications ranging from consumer electronics to industrial systems and EVs, due to their compact size, control flexibility, cost and efficiency [

25]. The operation of these converters involves switching a DC voltage source to produce a stable output voltage, with the average output controlled by adjusting the switching time. Advanced designs with control circuits and feedback control are required to maintain output stability despite fluctuations in the input voltage [

26]. Additionally, some converters utilise resonant components and transformers to enhance performance and efficiency, particularly in applications that require voltage isolation or transformation. Overall, DC-DC converters are integral to the efficient operation of a wide array of electronic devices and systems, facilitating the adaptation of power supply levels to meet specific operational requirements [

27].

Figure 4 shows the classification of various types of DC-to-DC converters.

DC-to-DC converters are integral to the efficient operation of rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations, facilitating power transfer among PV panels, ESS and EV loads. These converters address challenges such as variable solar generation, diverse voltage requirements, and power quality issues, while supporting advanced features like bidirectional power flow and integration with IoT-CBMS. Recent advancements in DC-to-DC converter technologies have focused on improving efficiency, reducing total harmonic distortion (THD), and enabling V2G functionality, which are critical for enhancing grid efficiency and power quality in modern power systems [

30].

Advanced DC-to-DC converters such as Buck, Boost, Buck-Boost, and Dual-Active-Bridge (DAB) topologies play an important role in managing power flow, voltage fluctuation, and power conversion across different operating conditions [

31] . Recent advancements in these converters, enhanced by wide-bandgap (WBG) semiconductors like GaN and SiC, offer high efficiency, compact design, and high-frequency operation, making them ideal for dynamic conditions [

32]. The integration of these converters with Artificial Intelligence (AI)/Machine Learning (ML)-based control strategies and Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) algorithms enables the real-time optimisation of energy harvesting from photovoltaic (PV) sources, while ensuring a stable output under fluctuating solar irradiance and load conditions. Furthermore, bidirectional converter designs support V2G functionality, enabling EVs to act as distributed power generation sources, which can contribute to grid stability and demand response [

33] .

Despite these advancements, challenges such as maintaining efficiency at high duty cycles, electromagnetic interference (EMI) suppression, and ensuring interoperability with grid standards remain [

34]. Addressing these issues through modern converter design and IoT-enabled energy management is essential for using the full potential of RES-integrated EV charging stations in future smart grid development [

35].

In rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations, where the energy flow is unidirectional (from the PV array to the battery), the boost converter emerges as a highly efficient and practical solution. This converter is particularly well-suited when the PV voltage consistently exceeds the battery charging voltage, a common scenario in rooftop installations. The boost converter’s ability to step up voltage with minimal component complexity makes it not only cost-effective but also highly reliable for long-term deployment. Its simple design reduces switching losses and simplifies control, which is especially advantageous in systems where operational stability and efficiency are important [

36]. Moreover, the boost converter integrates with MPPT algorithms, enabling dynamic adjustment of the duty cycle to ensure optimal energy harvesting from the solar array. This synergy between MPPT and the boost topology enhances the overall efficiency of the system. Compared to the more complex bidirectional or buck-boost converters, the boost converter avoids unnecessary overhead, making it ideal for applications where energy flows in a single direction [

37].

For bidirectional Battery-to-Grid (B2G) applications in EV charging infrastructure, the DAB converter is widely recognised as the most effective DC-DC topology due to its inherent bidirectional power flow capability, galvanic isolation, and high efficiency. The DAB converter enables seamless energy transfer between the EV battery and G2V and V2G/B2G modes with minimal switching losses [

38]. Its high-frequency transformer provides electrical isolation, enhancing safety and allowing flexible voltage matching between the battery and grid terminals. Moreover, DAB topology supports soft-switching techniques such as Zero Volt Switching (ZVS), which significantly reduces switching losses and electromagnetic interference, making it ideal for high-power, high-efficiency applications. Its ability to operate efficiently across a wide voltage range is particularly advantageous in EV systems where battery voltage varies significantly during operation. Recent studies have highlighted the DAB converter’s superior performance in renewable and grid-interactive systems, citing its modularity, control flexibility, and suitability for dynamic grid conditions [

39].

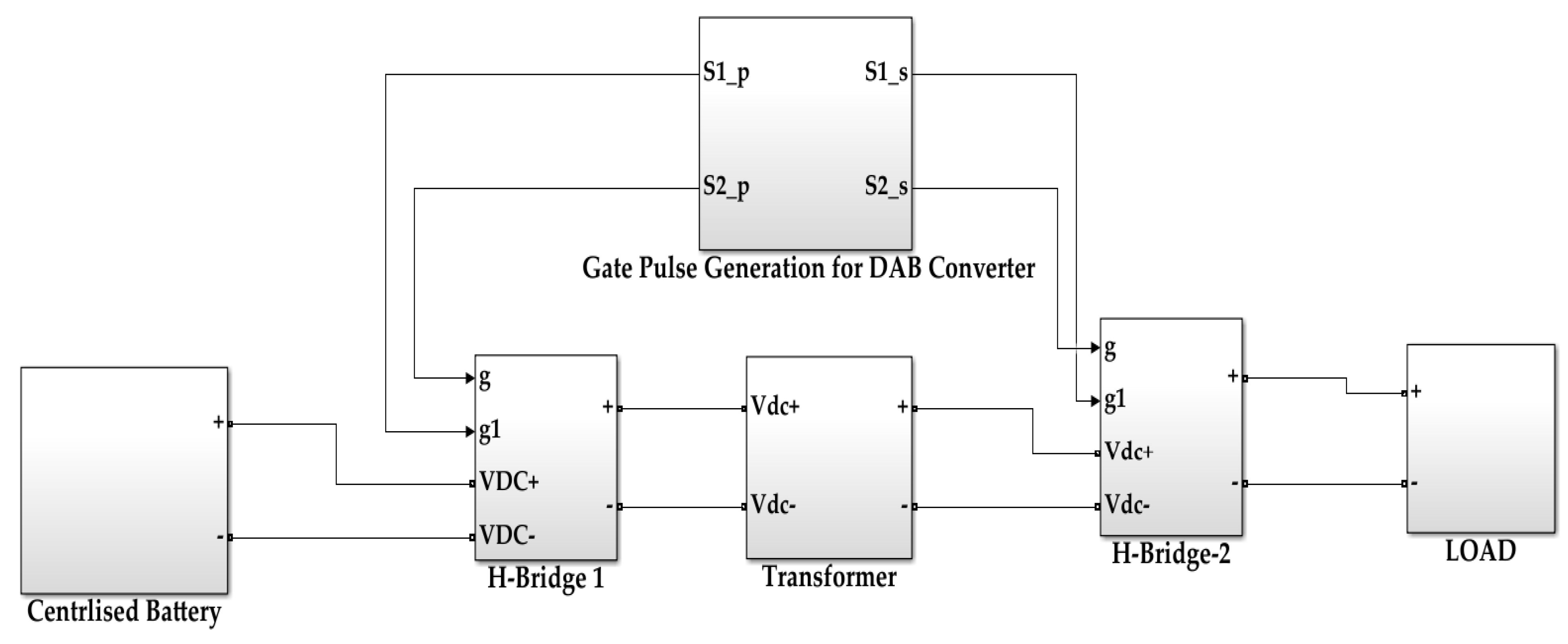

3.1. Dual-Active-Bridge (DAB) Converter

The DAB converter stands out as a powerful solution for enabling both G2V charging and V2G discharging. Its ability to handle power flow in both directions, while maintaining electrical isolation and high efficiency, makes it a key component in smart EV charging infrastructure. The DAB converter consists of two full-bridge inverters connected via a high-frequency transformer. One bridge interfaces with the DC link of a grid-tied inverter, while the other connects to the EV battery [

40]. The transformer provides electrical isolation and voltage matching, while the bidirectional nature of the bridges enables seamless power flow in both directions. A DC link capacitor stabilises the voltage, and a controller controls the phase shift between the bridges to regulate power transfer [

41].

In this study, a DAB converter is simulated. The converter has an input voltage range of 400–800 V DC (from the grid side) and an output voltage range of 200–400 V DC (for the EV battery side). The converter operates at a switching frequency of 50 kHz and supports power ratings from 60 kW. The transformer turns ratio is selected based on the voltage levels and desired power transfer efficiency.

Figure 5 shows the simulation diagram of the DAB converter, and

Figure 6 shows the DC output voltage of the DAB converter.

Design of the leakage inductance output capacitor and ZVS switching is done as follows [

42]:

,

.

ZVS condition: To achieve ZVS, the peak inductor current must be sufficient to discharge the switch output capacitance before turn-on. The peak current is given by [

43]:

The minimum inductance required for ZVS is:

.

4. IoT-Based CBMS Algorithm

ESS are increasingly vital for modern power grids, especially as RES become more popular. ESS, such as batteries and supercapacitors, are necessary for stabilising the DC voltage bus and providing system stability, which is essential for controlling the variability in renewable energy generation [

44]. Advanced control methods, such as G2V and V2G systems, further optimise the allocation of EV charging stations and RES, ensuring that energy distribution aligns with the unpredictable nature of both RES generation and EV charging demands [

45].

4.1. Key Roles of ESS in Modern Power Grids:

Grid Flexibility and Stability: ESS help manage the variability and intermittency of renewables, such as wind and solar, ensuring stable and reliable grid operation. They provide fast frequency response, voltage regulation, and real-time balancing of supply and demand, which are essential for modern grids with high renewable penetration [

46]. To maintain grid stability, ESS must respond quickly to fluctuations in renewable generation. The SOC (State of Charge) equation helps monitor available energy in real time [

47] and is

,

.

This equation helps monitor battery energy levels in real time during both charging (G2V) and discharging (V2G) modes.

Peak Shaving and Load Leveling: By storing excess energy during low demand and releasing it during peak periods, ESS reduce the need for expensive grid expansion and helps manage peak loads efficiently [

33]. The power flow between the CBMS and the grid is calculated as [

48]:

Current from/to the CBMS

Power Quality Improvement: ESS contributes to voltage regulation, power factor correction, and reduction of grid congestion, thereby enhancing overall power quality and operational efficiency [

49].

The integration of RES with ESS in an EV charging station offers a promising solution for reducing dependency on the conventional power grid. By utilising solar power generation and storing it in batteries, EV charging stations can operate independently during periods of peak demand or grid outages[

50]. This not only enhances the overall power transfer capability of the system but also reduces the stress on the grid. RES-based ESS systems can be effective in various conditions, such as peak shaving, frequency regulation, and voltage support, contributing to improved grid stability and efficiency [

51].

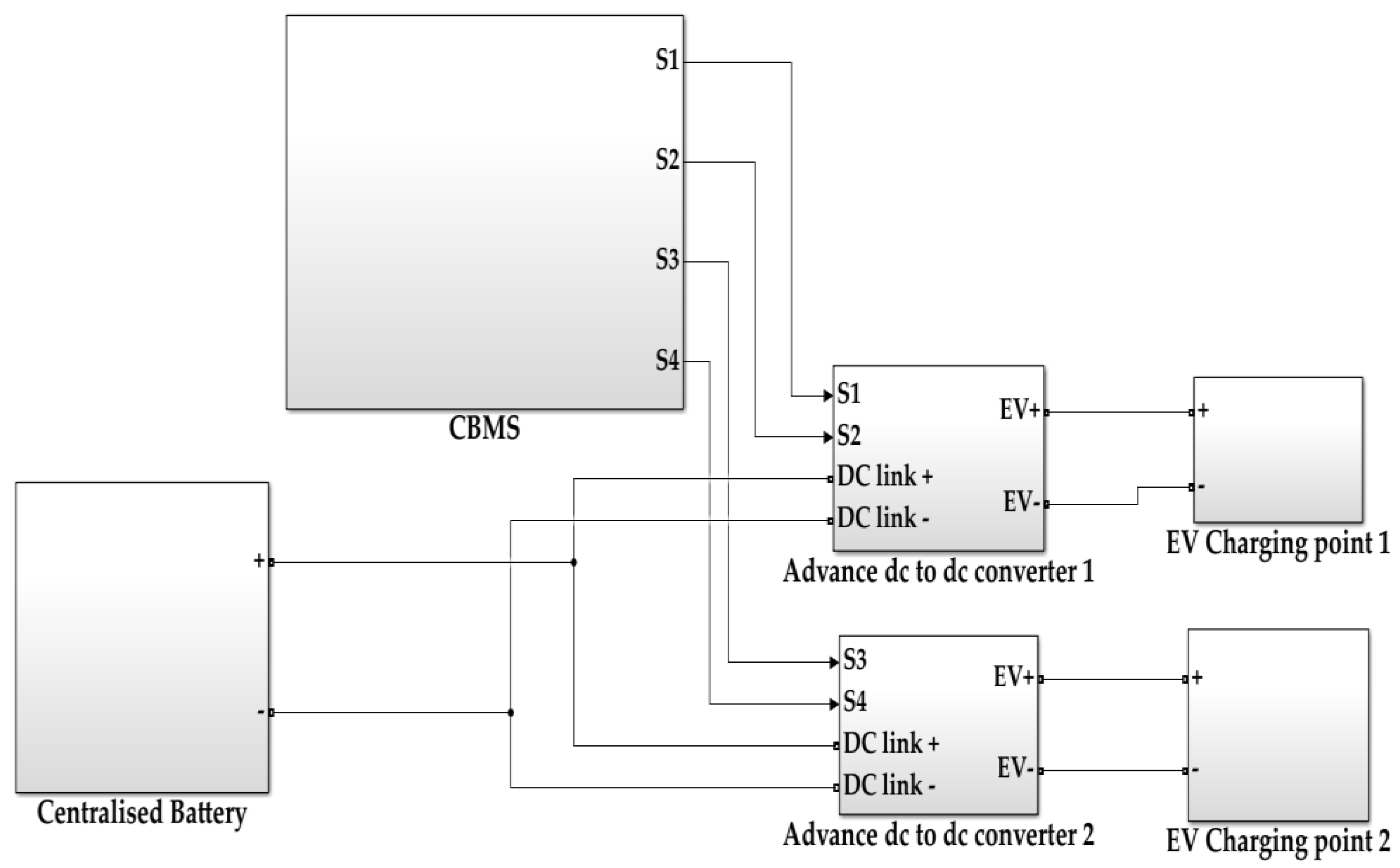

Figure 7 shows the MATLAB simulation diagram of a RES-based CBMS system for an EV charging station. In this setup, solar PV is harvested and stored in a centralised ESS. The CBMS oversees the health, charge/discharge cycles, and thermal conditions of the entire battery bank. When two EVs are connected to the station, the CBMS dynamically allocates power to each charging point based on real-time demand, battery state-of-charge (SoC), and grid availability. This centralised control ensures balanced energy distribution, prevents overloading, and increases the use of renewable energy, even during peak hours. CBMS enables peak shaving by supplying stored energy during high-demand periods, reducing dependency on the grid. The CBMS serves as the central brain of the system, ensuring that both electric vehicle (EV) charging points and the grid operate efficiently and sustainably. IoT-based CBMS can forecast energy demand, optimise charging schedules, and control variable renewable energy sources (RES) inputs. The system’s reliability is thus enhanced.

4.2. Control Algorithm

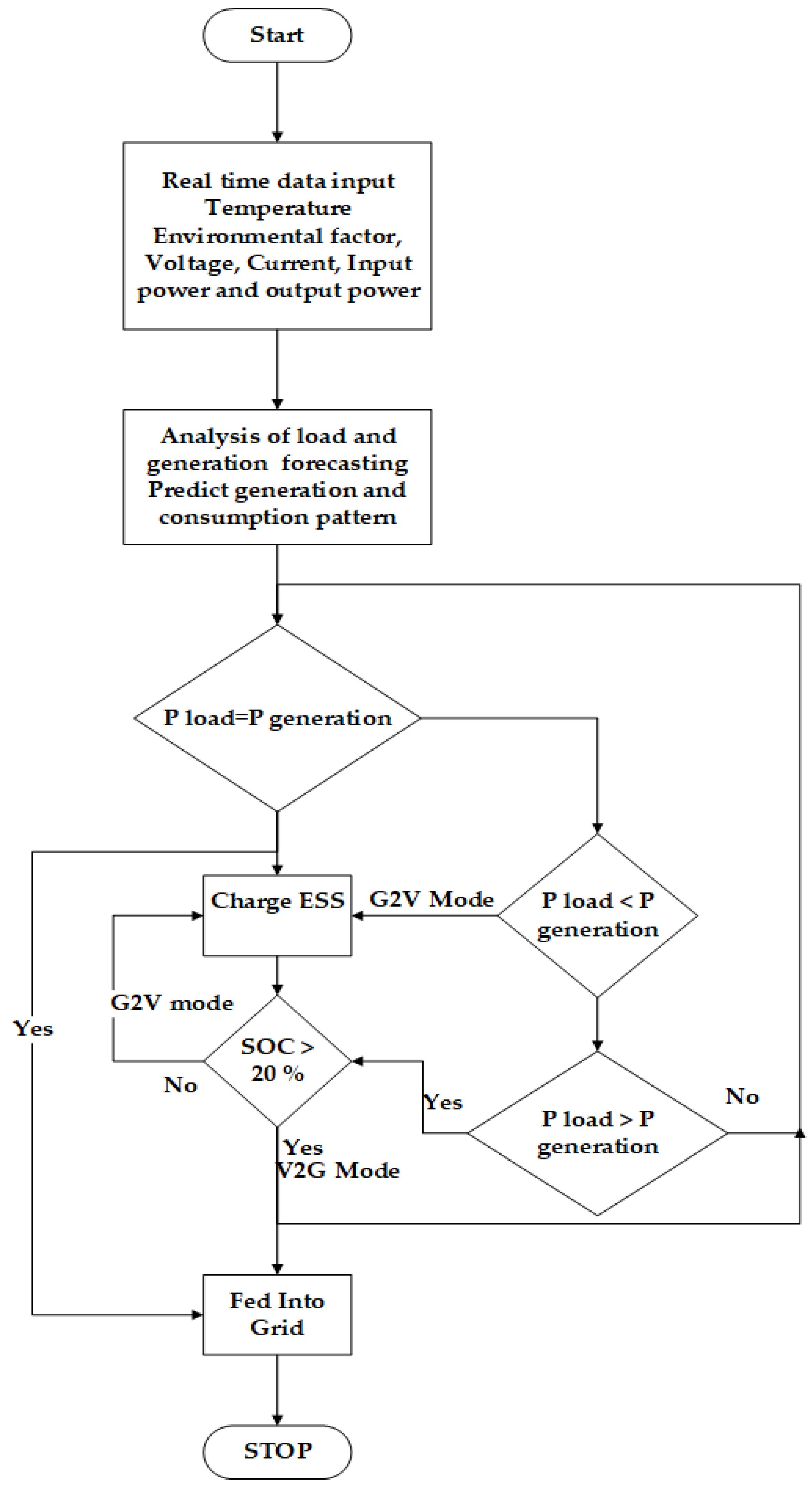

This algorithm enables real-time monitoring, load forecasting, and storage management, improving overall grid performance. To understand the control algorithm, it is divided into two distinct parts.

Figure 8 illustrates real-time monitoring and load forecasting, which helps in understanding the variable generation of RES. Real-time monitoring and load forecasting offer numerous advantages, particularly in the context of RES. These features enhance predictive accuracy, providing precise forecasts of power generation and consumption patterns, which is important for integrating variable RES into the grid. Improved grid stability is another significant benefit, as accurate load and generation forecasts help mitigate the fluctuations inherent in RES, ensuring consistent power delivery. Additionally, these algorithms optimise resource allocation, reducing operational costs and enhancing the efficiency of energy distribution. The continuous monitoring capabilities enable proactive maintenance by detecting potential issues early, thereby reducing unexpected system failures and extending the longevity of the power infrastructure. Furthermore, these features make the algorithm scalable, flexible, and adaptable to various grid sizes and configurations, which is ideal for hybrid energy systems.

Figure 8 also illustrates the energy storage and management features of the algorithm, which are crucial for maintaining power supply and demand, controlling EV charging, and facilitating V2G and G2V interactions within the smart grid. This helps with the bidirectional flow of energy to enhance grid stability and flexibility, making it easier to integrate RES and manage peak demand periods by optimising the use of ESS.

4. Results and Discussion

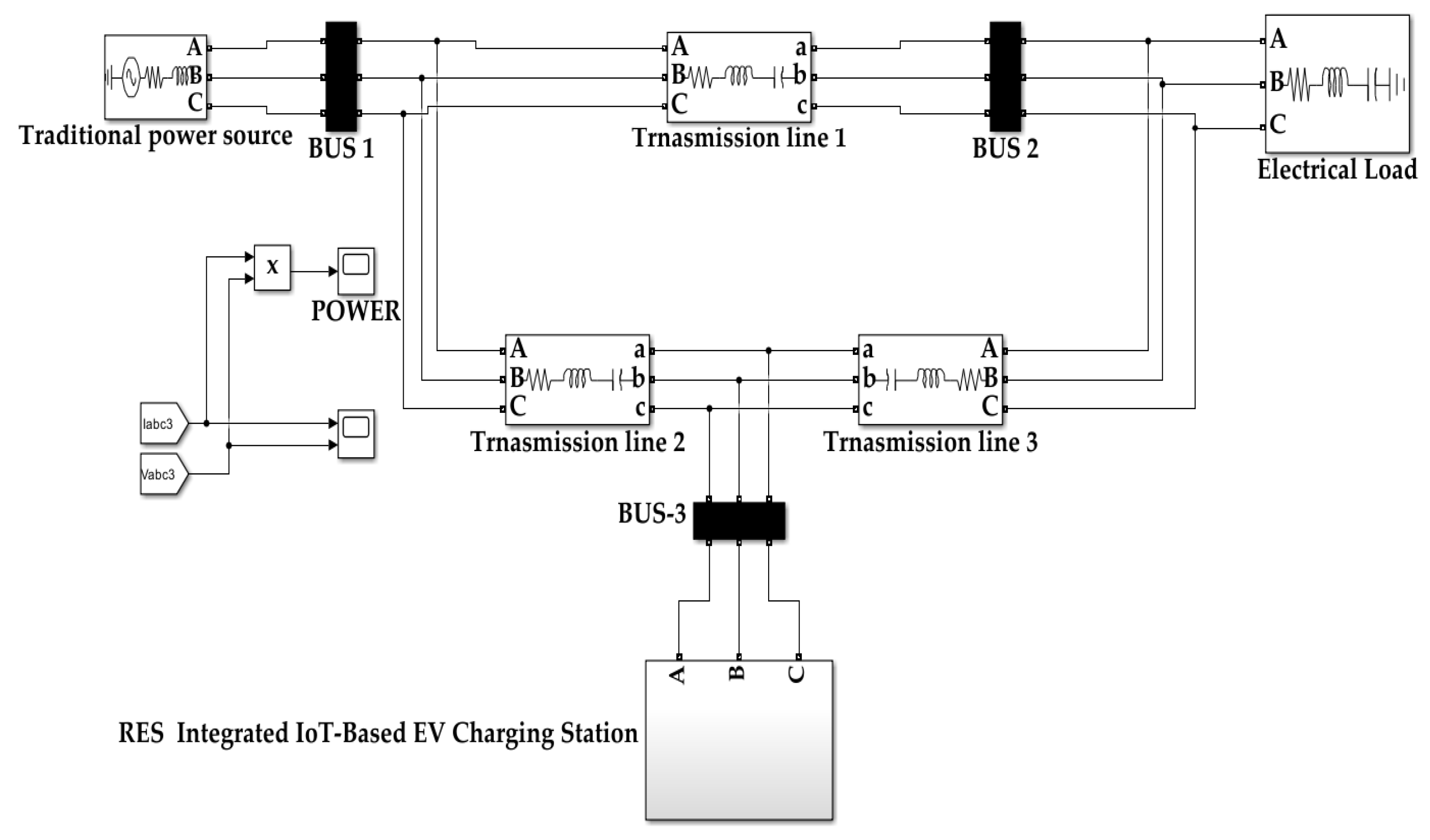

Figure 9 shows the simulation diagram of the proposed system. The proposed system is organised into three different buses.

BUS 1: This bus is connected to conventional power generation sources such as thermal or hydroelectric plants. It serves as the primary power input for the system, especially during periods when renewable generation is insufficient or unavailable.

BUS 2: This Bus connects with residential, commercial, or industrial loads. The load bus operates independently of the EV charging infrastructure.

BUS3: This bus is connected to a RES-based EV charging station that is integrated with a CBMS. It manages the flow of energy between ESS and multiple EV charging points. The CBMS monitors key parameters, such as SOC and THD, during both charging and discharging. This bus supports G2V and V2G operations. It also enables bidirectional power flow and improves grid flexibility.

Two types of modes are simulated – the first is Mode 1 for the case G2V to G2B, when the grid is in surplus, and the second is Mode 2 for the case V2G/B2G, when the grid demand is high. These two modes are described below.

Mode 1: Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) / Grid-to-Battery (G2B):

In this mode, the system operates under conditions where excess power is available from the conventional grid (Bus 1). The CBMS plays an important role in managing this surplus by charging both centralised battery storage and battery-connected EV charging points. This mode enhances renewable energy utilisation, reduces grid stress during low demand, and supports cost-effective EV charging. It also prepares the system for future discharge during peak demand.

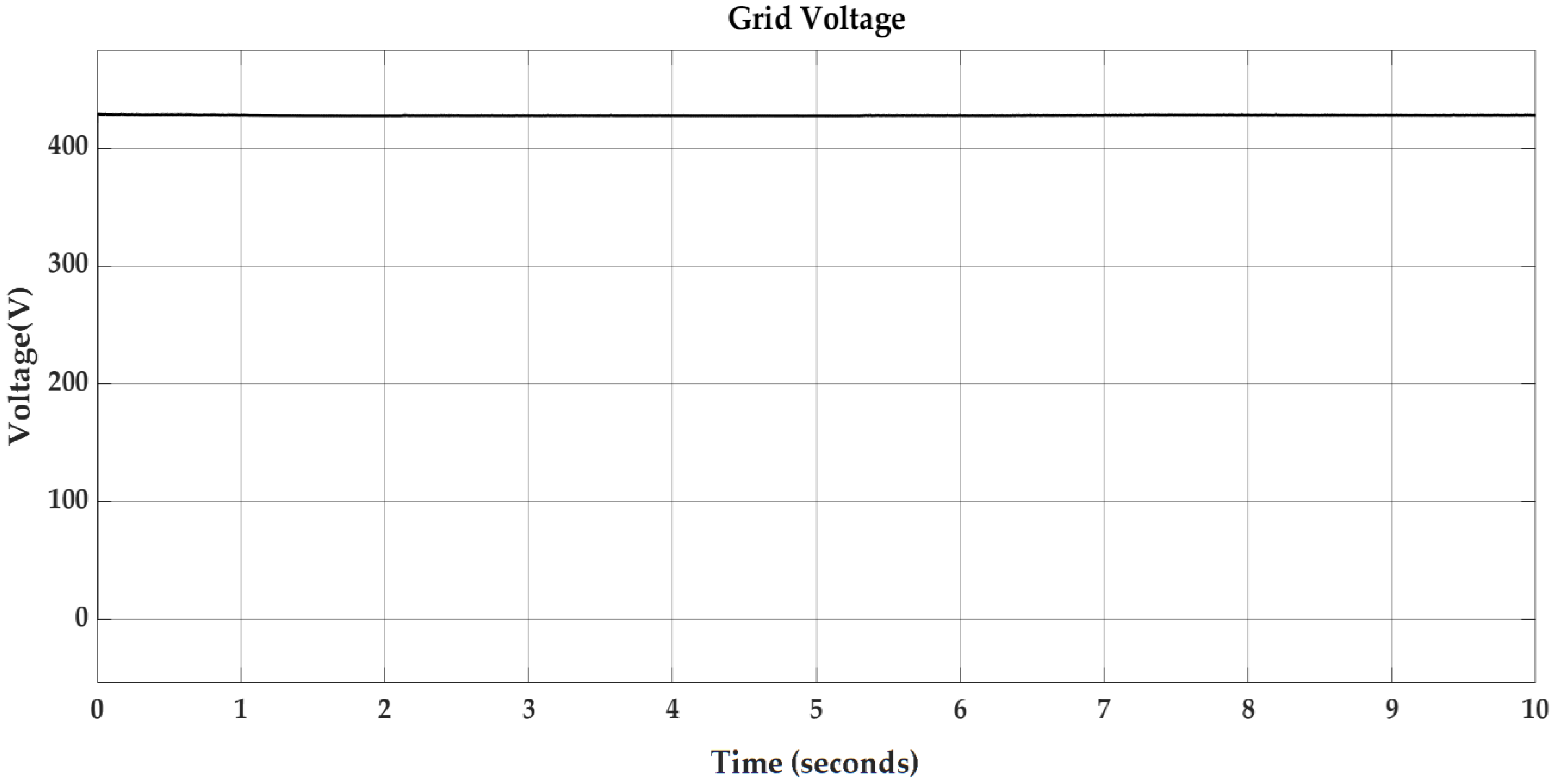

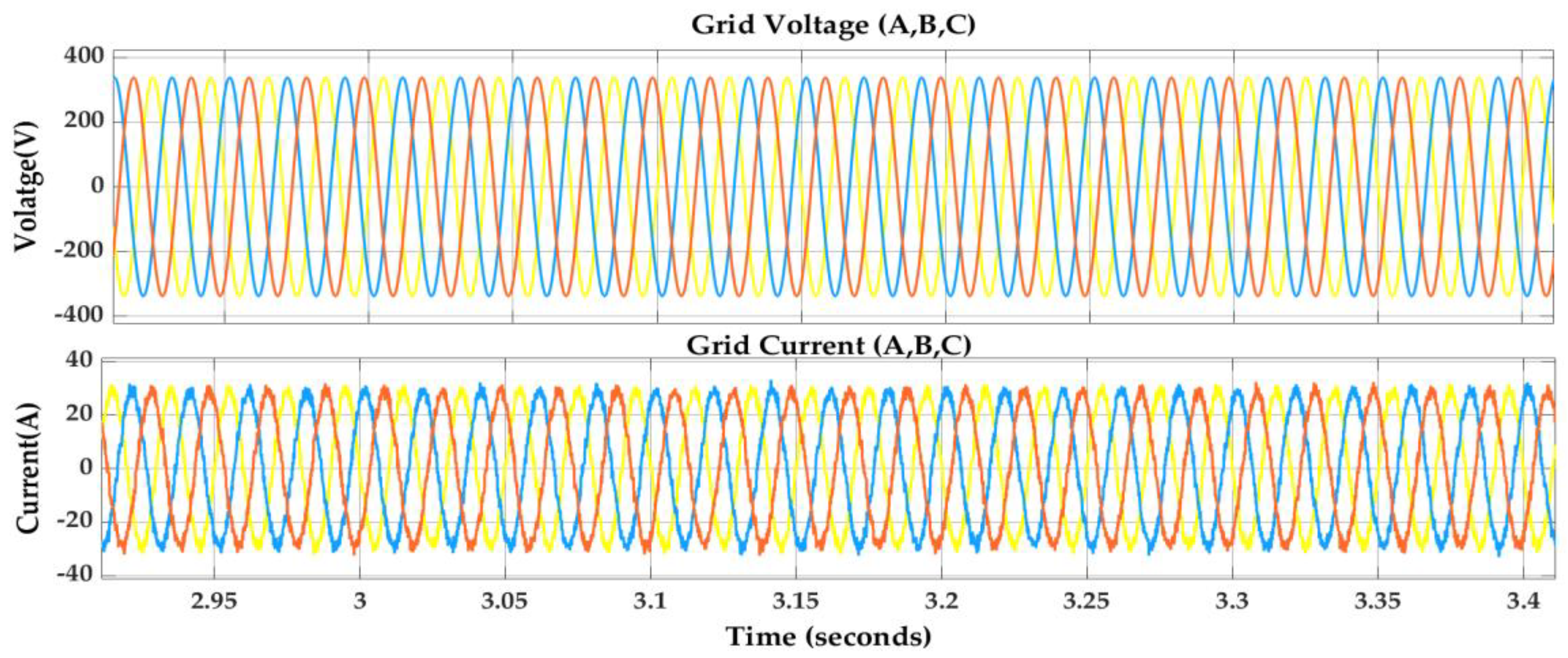

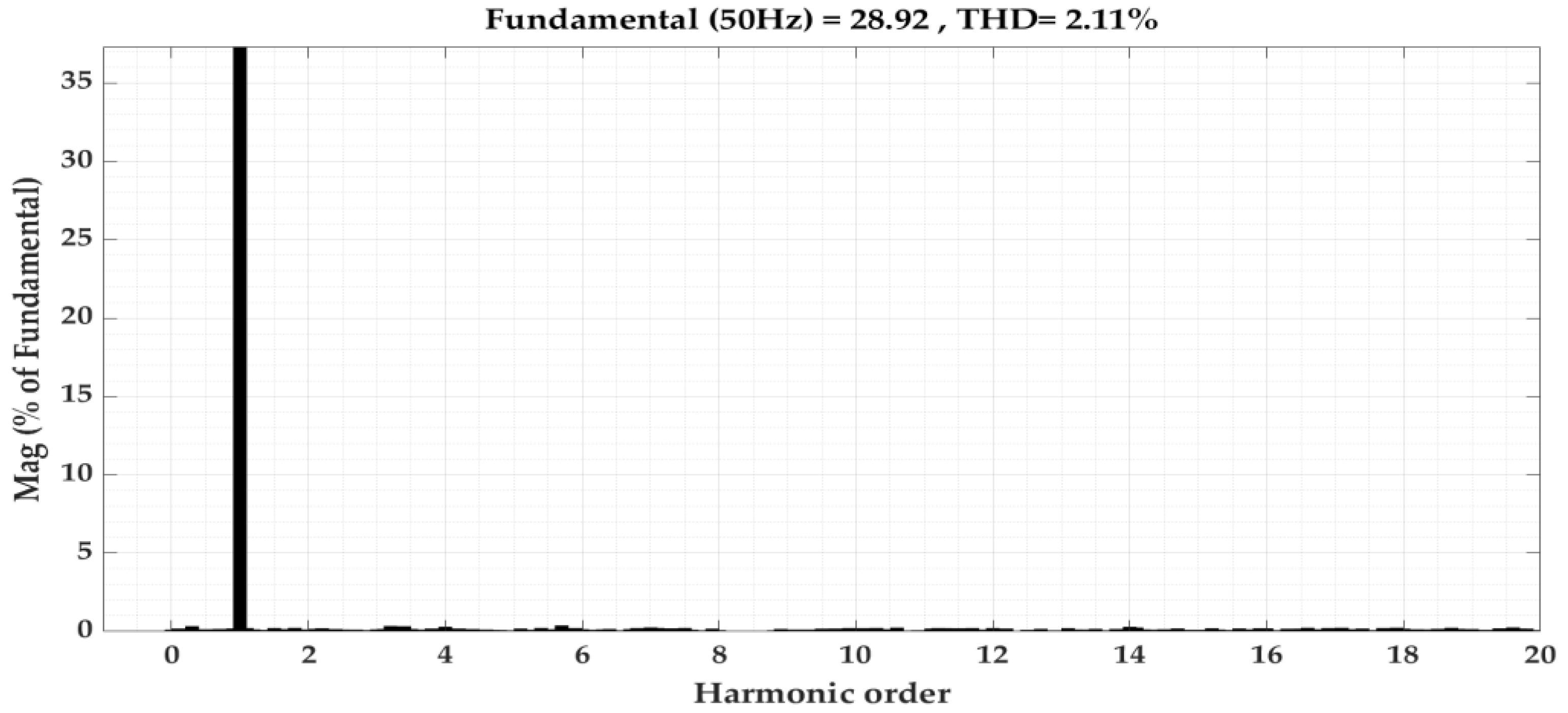

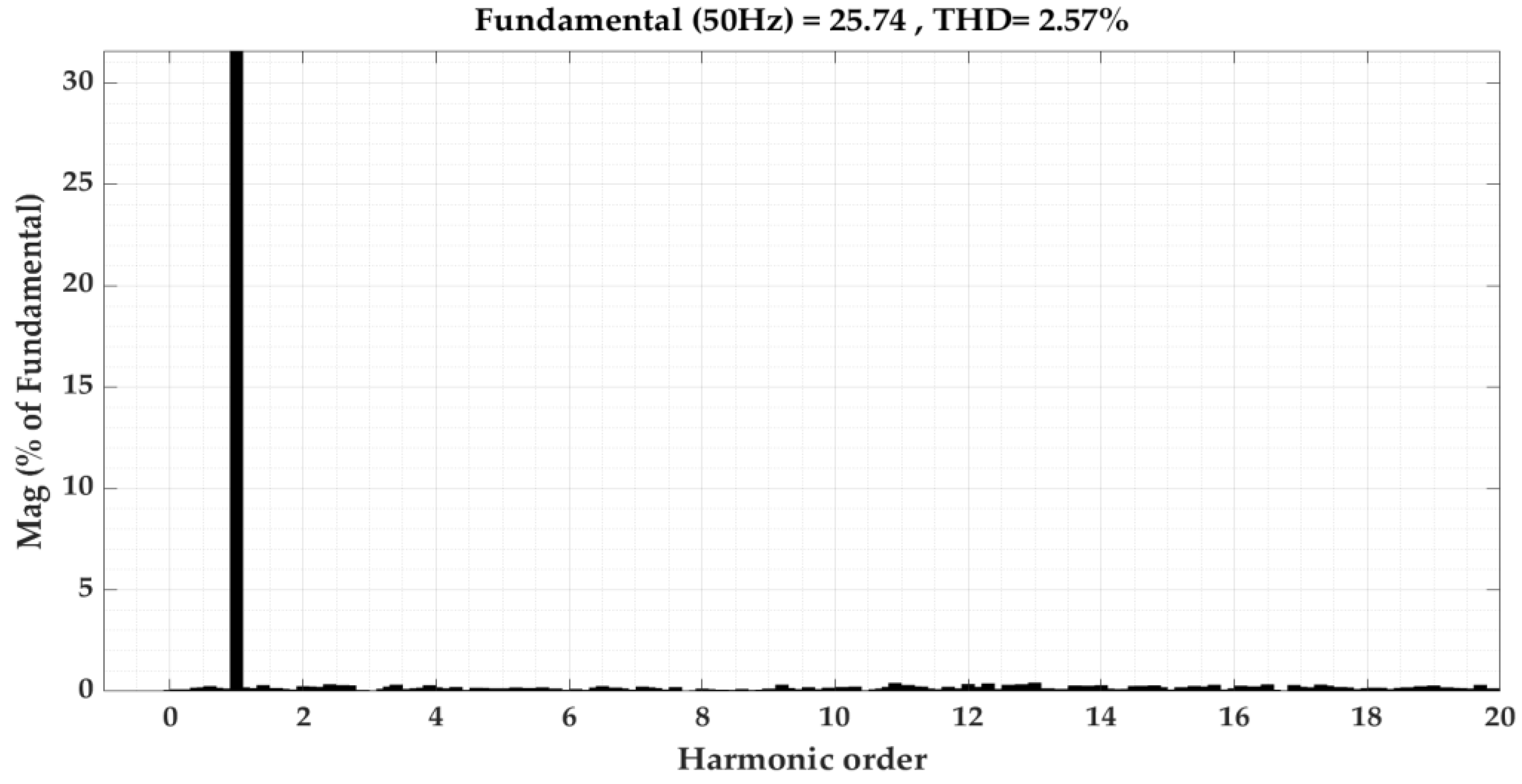

Figure 10 shows that the voltage and current waveforms on the grid side are sinusoidal, confirming proper power flow and synchronisation with the grid. FFT analysis of grid current, shown in

Figure 11, demonstrates low harmonic distortion, validating the effectiveness of the LC filter.

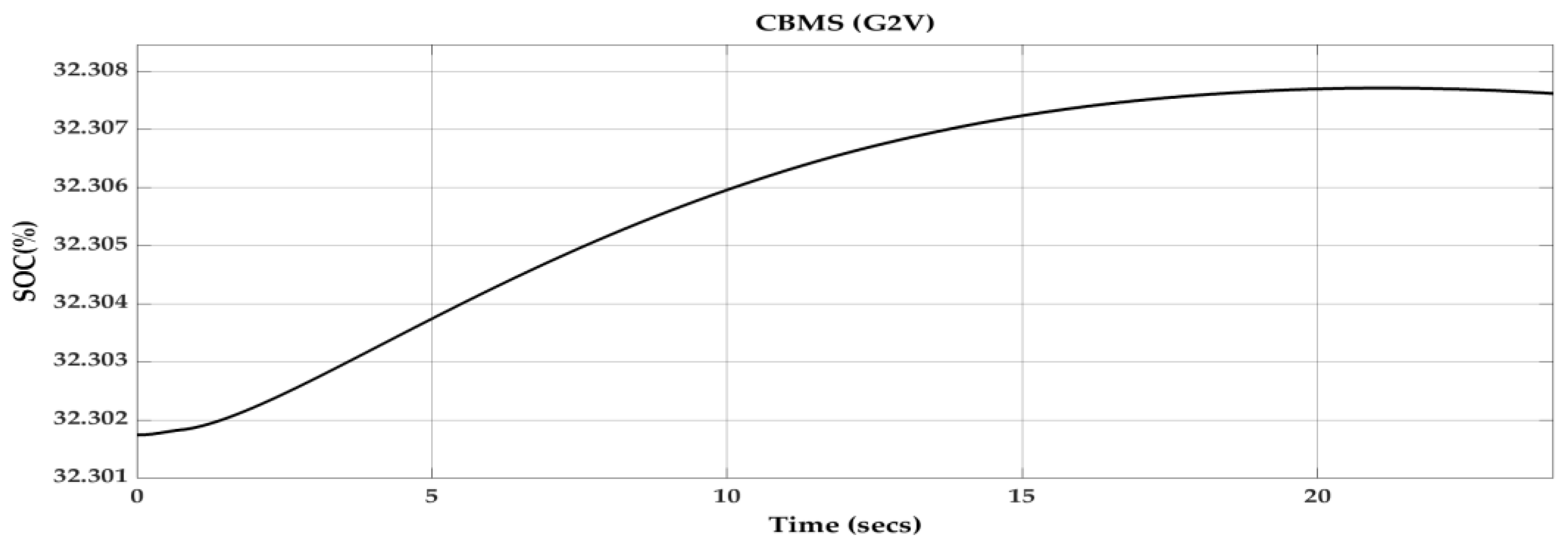

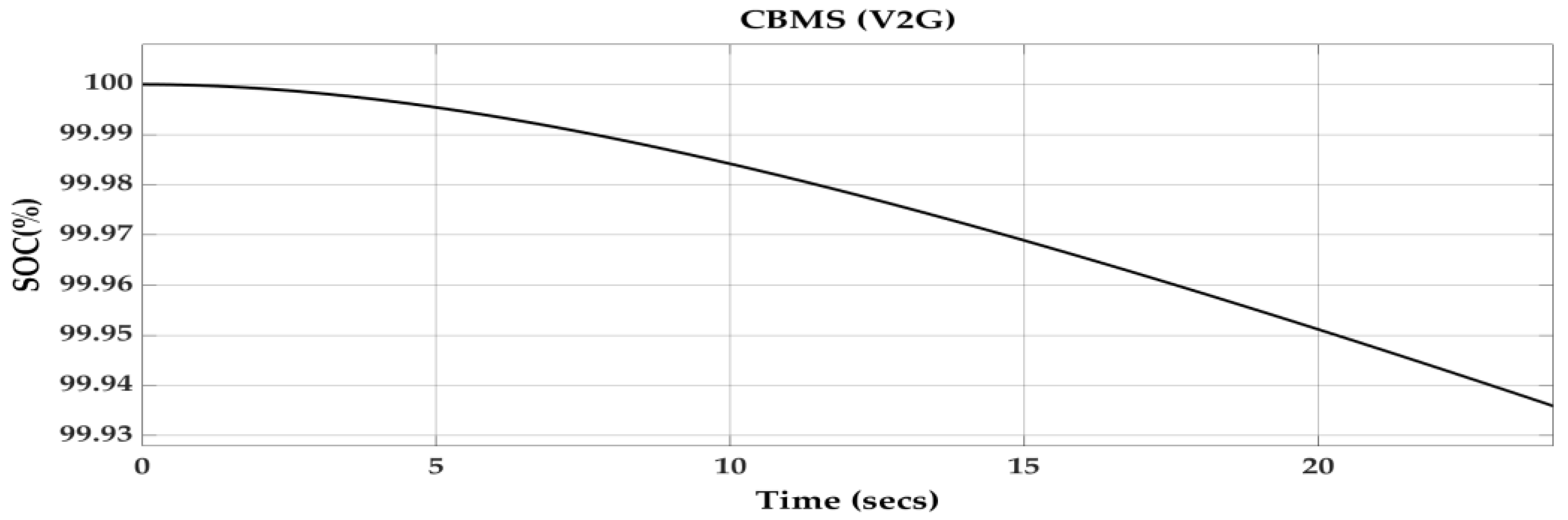

Figure 12 shows the SOC profile with the battery charging in G2V mode.

Mode 2: Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) / Battery-to-Grid (B2G)

This mode is activated when the grid requires additional power, such as during peak demand or emergencies. The system responds by discharging energy from the centralised battery and EVs back to the grid. This mode transforms EVs and battery storage into peak power plants. It is also beneficial for improving grid resilience and enabling smart grid functionality. This mode makes the system adaptive, intelligent, and sustainable, aligning with global goals for clean energy, electrified transport, and grid transformation.

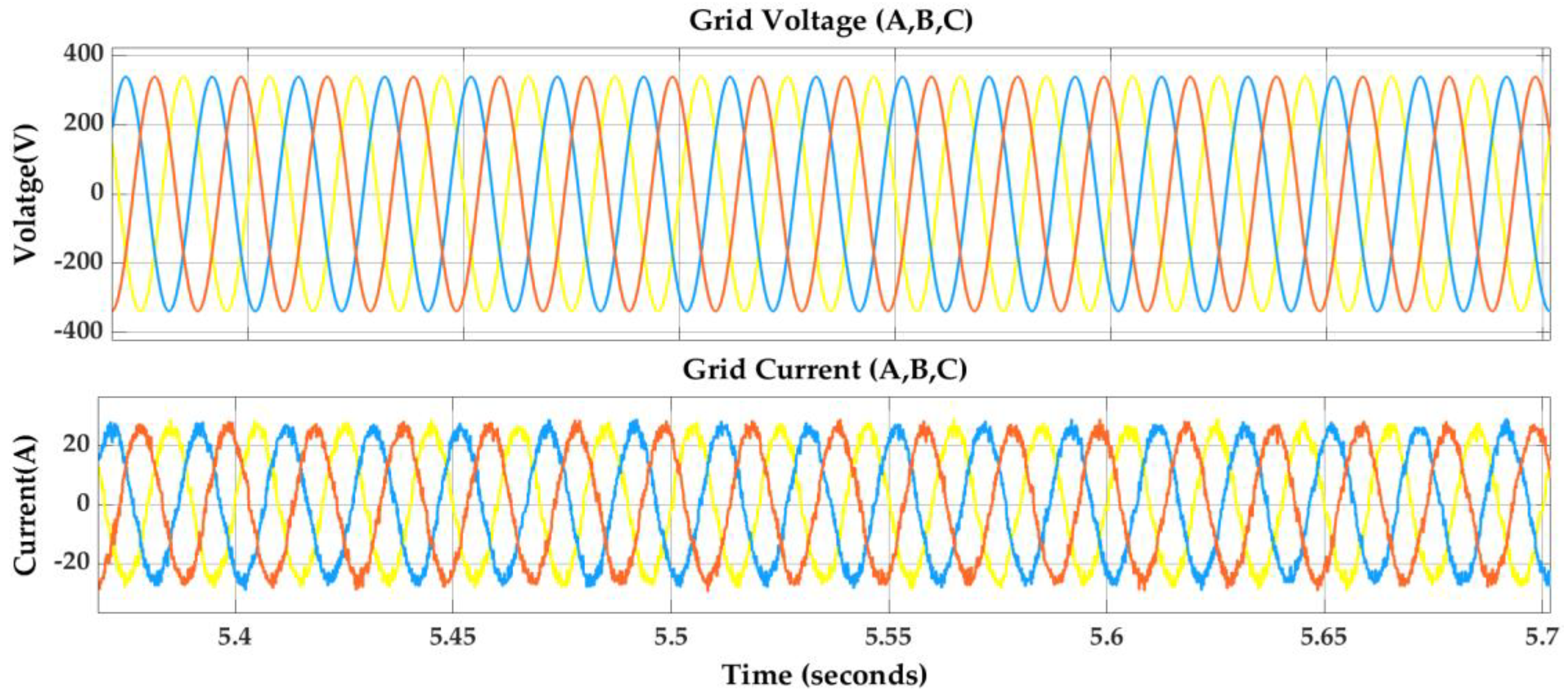

Figure 13 shows that the voltage and current waveforms on the grid side are sinusoidal, confirming proper power flow and synchronisation with the grid.

Figure 14 shows the FFT analysis of the grid current, revealing low harmonic distortion, validating the effectiveness of the LC filter in meeting grid power quality standard

s. Figure 15 shows the SOC profile during V2G mode, indicating a gradual decrease that represents battery discharging to support grid demand.

5. Future Directions

Future research can focus on several areas to enhance the proposed system. Integrating AI and ML into the IoT-based CBMS can improve real-time forecasting and energy management. This could lead to more accurate predictions of solar generation and EV charging demands. Further testing the system in real-world conditions will validate the simulation results and identify practical challenges. Additionally, exploring new DC-to-DC converter designs, such as multi-port converters, could further improve efficiency and reduce costs. Addressing EMI in high-frequency converters will enhance system reliability. Finally, developing standardised communication protocols for V2G and G2V operations will ensure interoperability and scalability, supporting wider adoption of solar-powered EV charging stations.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that IoT-based CBMS and advanced DC-to-DC converters significantly improve the performance of rooftop solar-powered EV charging stations. The IoT-based CBMS enables real-time monitoring and adaptive energy management, optimising power flow and reducing grid stress. Advanced converters, like the DAB and boost topologies, ensure efficient energy transfer and support bidirectional V2G and G2V operations. MATLAB simulations of a 20-kW solar system confirm that these technologies enhance grid stability and power quality by mitigating issues like voltage fluctuations and harmonic distortion. The proposed system reduces reliance on fossil fuels and supports sustainable energy solutions. By addressing challenges like solar variability and battery degradation, this work contributes to the development of reliable and efficient smart grids for EV charging.

Author Contributions

Shanikumar Vaidya managed the conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, and writing of the original draft. Krishnamachar Prasad contributed to the methods and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Jeff Kilby reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- IEA (2024), Share of renewable electricity generation by technology, 2000-2028, IEA, Paris. (2024); Available from: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/share-of-renewable-electricity-generation-by-technology-2000-2028, Licence: CC BY 4.0.

- Purkait, P., Basu, and S.R. Nath, Renewable Energy Integration to Electric Power Grid: Opportunities, Challenges, and Solutions, in Challenges and Opportunities of Distributed Renewable Power, S. De, A.K. Agarwal, and P. Kalita, Editors. 2024, Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore. p. 37-100.

- Brenna, M.; Foiadelli, F.; Leone, C.; Longo, M. Electric Vehicles Charging Technology Review and Optimal Size Estimation. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2020, 15, 2539–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Mohanty, S. Grid connected electric vehicle charging and discharging rate management with balance grid load. Electr. Eng. 2022, 105, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, G.; Vaithilingam, C.A.; Naidu, K.; Oruganti, K.S.P. Energy-efficient converters for electric vehicle charging stations. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Yap, P.-S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, environmental, and economic consequences of integrating renewable energies in the electricity sector: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, B., Integration of Renewable Energy Sources to Power Networks and Smart Grids, in Renewable Energy Based Solutions, T.S. Uyar and N. Javani, Editors. 2022, Springer International Publishing: Cham. p. 81-103.

- Kiasari, M.; Ghaffari, M.; Aly, H.H. A Comprehensive Review of the Current Status of Smart Grid Technologies for Renewable Energies Integration and Future Trends: The Role of Machine Learning and Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.A.d. and M.H.J. Bollen, Deep learning for power quality. Electric Power Systems Research, 2023. 214.

- Ullah, Z.; Hussain, I.; Mahrouch, A.; Ullah, K.; Asghar, R.; Ejaz, M.T.; Aziz, M.M.; Naqvi, S.F.M. A survey on enhancing grid flexibility through bidirectional interactive electric vehicle operations. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 5149–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlilo, N.; Brown, J.; Ahfock, T. Impact of intermittent renewable energy generation penetration on the power system networks – A review. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2021, 6, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R. and F.M. Fernandez. Grid inertia based frequency regulation strategy of photovoltaic system without energy storage. in 2018 International CET Conference on Control, Communication, and Computing (IC4). 2018. IEEE.

- Bamukunde, J. and S. Chowdhury, A study on mitigation techniques for reduction and elimination of solar PV output fluctuations. 2017 IEEE AFRICON, 2017: p. 1078-1083.

- Prasad, D.; Dhanamjayulu, C. A Review of Control Techniques and Energy Storage for Inverter-Based Dynamic Voltage Restorer in Grid-Integrated Renewable Sources. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataray, T.; Nitesh, B.; Yarram, B.; Sinha, S.; Cuce, E.; Shaik, S.; Vigneshwaran, P.; Roy, A. Integration of smart grid with renewable energy sources: Opportunities and challenges – A comprehensive review. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidimukkala, N., N. Das, and S. Islam, Power Quality Improvement of a Solar Powered Bidirectional Smart Grid and Electric Vehicle Integration System, in 2022 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC). 2022. p. 1-6.

- Simpa, P.; Solomon, N.O.; Adenekan, O.A.; Obasi, S.C. The safety and environmental impacts of battery storage systems in renewable energy. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 22, 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furkan, D. and M. Mehmet Emin, Critical factors that affecting efficiency of solar cells. smart grid and renewable energy, 2010. 2010.

- Mustafa, R.J.; Gomaa, M.R.; Al-Dhaifallah, M.; Rezk, H. Environmental Impacts on the Performance of Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosenuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.A.; Selvaraj, J.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Malek, A.B.M.A.; Nahar, A. Global prospects, progress, policies, and environmental impact of solar photovoltaic power generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.K., M. Kumar, A. Kumari, and J. Kumar. Bidirectional DC-DC Buck-Boost Converter for Battery Energy Storage System and PV Panel. 2021. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Gheisarnejad, M.; Khooban, M.H. IoT-Based DC/DC Deep Learning Power Converter Control: Real-Time Implementation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 13621–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ourahou, M.; Ayrir, W.; EL Hassouni, B.; Haddi, A. Review on smart grid control and reliability in presence of renewable energies: Challenges and prospects. Math. Comput. Simul. 2020, 167, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, N.H., T.M.N.T. Mansur, F.A. Hamid, and R. Ali, Performance Analysis of DC-DC Buck Converter for Renewable Energy Application. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2018. 1019(1): p. 012020.

- Shukla, U., S. Yadav, N. Tiwari, and A. Priyadarshini. Comprehensive Review on AC-DC, DC-DC, DC-AC-DC Converters Used for Electric Vehicles and Charging Stations. 2024. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Joseph, A., S. Sreehari, and A.M. George. A review of DC DC converters for renewable energy and EV charging applications. in 2022 Third International Conference on Intelligent Computing Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT). 2022. IEEE.

- Akhtar, M.F.R.S. Raihan, N.A. Rahim, and M.N. Akhtar, Recent Developments in DC-DC Converter Topologies for Light Electric Vehicle Charging: A Critical Review. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(3).

- Lencwe, M.J.; Olwal, T.O.; Chowdhury, S.D.; Sibanyoni, M. Nonsolitary two-way DC-to-DC converters for hybrid battery and supercapacitor energy storage systems: A comprehensive survey. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 2737–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Vu, H.-N.; Hasan, M.M.; Tran, D.-D.; El Baghdadi, M.; Hegazy, O. DC-DC Converter Topologies for Electric Vehicles, Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles and Fast Charging Stations: State of the Art and Future Trends. Energies 2019, 12, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchala-Ávila, C.; Arévalo, P.; Ochoa-Correa, D. A Systematic Review of Model Predictive Control for Robust and Efficient Energy Management in Electric Vehicle Integration and V2G Applications. Modelling 2025, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Zhang, X.; Khan, M.; Mastoi, M.S.; Munir, H.M.; Flah, A.; Said, Y. A comprehensive review of wind power integration and energy storage technologies for modern grid frequency regulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, L. and J. Zhang, Performance Analysis of DC-DC Converters Using GaN HEMT, Si, and SiC MOSFET Technologies. Authorea Preprints, 2025.

- Nwulu, N., Neelima, G. Dinesh, and K. Natarajan, A Fuzzy-Based Method for Improving the Quality of Power in a Grid-Connected System Using a Solar Pv-Fed Multilevel Inverter. E3S Web of Conferences, 2024. 547.

- Rajender, J.; Dubey, M.; Kumar, Y.; Somanna, B.; Alshareef, M.; Namomsa, B.; Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Abdelwahab, S.A.M. Design and analysis of a high-efficiency bi-directional DAB converter for EV charging. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkelawy, M.; Saeed, A.M.; Atta, Z.A.; Sayed, M.M.; Hamouda, M.A.; Almasri, A.M.; Seleem, H.E. Transforming Conventional Vehicles into Electric: A Comprehensive Review of Conversion Technologies, Challenges, Performance Enhancements, and Future Prospects. Pharos Eng. Sci. J. 2025, 2, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athiveerapandian, A., R.V.K.K. Kiran, and T. Ebinesan, Programmable buck-boost converter for EV charging application. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2024. 3044(1).

- Jagadeesh, I.; Indragandhi, V. Comparative Study of DC-DC Converters for Solar PV with Microgrid Applications. Energies 2022, 15, 7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Saggu, T.S.; Letha, S.S.; Bakhsh, F.I. V2G based bidirectional EV charger topologies and its control techniques: a review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, D. and G. Xu, Three-Level Bidirectional DC–DC Converter with an Auxiliary Inductor in Adaptive Working Mode for Full-Operation Zero-Voltage Switching, in High-Frequency Isolated Bidirectional Dual Active Bridge DC–DC Converters with Wide Voltage Gain. 2019, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p.

- Rana, R.; Saggu, T.S.; Letha, S.S.; Bakhsh, F.I. V2G based bidirectional EV charger topologies and its control techniques: a review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidya, S. and A. Shukla, Comprehensive Analyses of Control Techniques in Dual Active Bridge DC–DC Converter for G2V Operations, in Recent Advances in Power Electronics and Drives. 2024. p. 135-151.

- Srivastava, K.; Maurya, R.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, S.K. EV battery charging infrastructure in remote areas: Design, and analysis of a two-stage solar PV enabled bidirectional STC-DAB converter. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Mannen, and T. Isobe, Full-load Range ZVS Achievement by Using Both Burst Mode and PWM With Variable Frequency Modulation for DAB Converters, in 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE). 2024. p. 2648-2655.

- Pires, V.F., A. Roque, D.M. Sousa, and E. Margato. Management of an electric vehicle charging system supported by RES and storage systems. in 2018 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM). 2018. IEEE.

- Ali, A.; Shaaban, M.F.; Awad, A.S.A.; Azzouz, M.A.; Lehtonen, M.; Mahmoud, K. Multi-Objective Allocation of EV Charging Stations and RESs in Distribution Systems Considering Advanced Control Schemes. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 72, 3146–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, V.S.; Gaidhane, P. A resilient approach for optimizing power quality in grid integrated solar photovoltaic with asymmetric 15-level inverter. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srihari, G.; Naidu, R.S.R.K.; Falkowski-Gilski, P.; Divakarachari, P.B.; Penmatsa, R.K.V. Integration of electric vehicle into smart grid: a meta heuristic algorithm for energy management between V2G and G2V. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1357863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sood, S.K.; Saini, M. Internet of Vehicles (IoV) Based Framework for electricity Demand Forecasting in V2G. Energy 2024, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. and L. Singh. A Comprehensive Study of Power Quality Improvement Techniques in Smart Grids with Renewable Energy Systems. 2024. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Shao, H.; Henriques, R.; Morais, H.; Tedeschi, E. Power quality monitoring in electric grid integrating offshore wind energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguieg, Z.; Bouyakoub, I.; Mehedi, F. Optimizing power quality in interconnected renewable energy systems: series active power filter integration for harmonic reduction and enhanced performance. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 7755–7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).