Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. History

3. Refrigerants

| Group | Type | Attribute | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) | R-134a | Tetrafluoroethane | Good energy efficiency, Widely available | High GWP, contributes to climate change | [58,66,68,69] |

| R-404A | HFC-125, HFC-143a and HFC-134a blend | Cooling capacity, Good performance at low temperatures | High GWP, under acceptance | [59,64,71,72] | |

| R-407C | HFC-32, HFC-125 and HFC-134a blend | Replacement of R-22, Lower GWP | Higher GWP than other solutions | [59,72,73,74,75] | |

| R-410A | HFC-32 and HFC-125 Blend | High Cooling Capacity, Low Noise | High GWP, phased acceptance phase | [59,72,73,74,75] | |

| R-507A | HFC-125 and HFC-143a mixture | Consistent performance at low temperatures | High GWP | [60,62,63,64,65,66] | |

| Hydrocarbons | R-290 | Propane | Significantly lower GWP, Energy efficient | Flammable, requires precautions | [71,78,79,81,83,84] |

| R-600a | Isobutane | Low GWP, Good Performance | Flammable, requires precautions | [58,78,81,85,86] | |

| R-170 | Ethane | Very Low GWP, High Efficiency | Flammable, limited applications | [14,79,80,87] | |

| Ammonia | R-717 | Ammonia | High Efficiency, Low Cost | Toxic, requires safety precautions | [88,89] |

| Carbon Dioxide | R-744 | Carbon Dioxide | Low GWP, non-toxic and non-flammable | High operating pressure, requires special equipment | [60,67,91,92,93,94,95] |

| Hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) | R-1234yf | 2,3,3,3-Tetrafluoropropene | Low GWP | New, limited availability and infrastructure | [86,96,97,98,99,100] |

| R-1234ze | Dia-1,3,3,3-tetrafluoropropene | Low GWP | New, limited availability and infrastructure | [51,96,101,102,103] | |

| Natural Cooling Taps | R-600 | Butane | Low GWP, good cooling properties | Flammable, requires precautions | [42,95] |

| R-744 | Carbon Dioxide | Low GWP, non-toxic and non-flammable | High operating pressure, requires special equipment | [60,67,91,92,93,94,95] | |

| R-717 | Ammonia | High Efficiency, Low Cost | Toxic, requires safety precautions | [88,89] | |

| Special Cooling Taps | R-401A | HFC-125, HFC-143a and HCFC-22 Blend | Used as a replacement for R-22 | High GWP, not a viable solution in the long term | [42] |

| R-421A | Azeotropic mixture to replace R-22 | Lower GWP than R-22 | Limited availability | [42,75,105] | |

| Inert Gas Refrigerant Taps | R-40 | Ethylene | Low GWP, non-toxic | Limited Apps | [104,106] |

| Other Cooling Taps | R-12 | Dichlorodifluoromethane - has been withdrawn due to ozone depletion | Cooling capacity at low temperatures | High GWP, causes ozone depletion | [104,106,107] |

| R-22 | Chlorodifluoromethane – withdrawn due to HFC regulations | Good performance and wide use | High GWP, withdrawn due to HFC regulations | [42,59,72,73,74,75] |

4. Importance and Application of ULT Freezers

| Category | Product Type | Standard Storage Temperature at Extremely Low Temperatures (ULT) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | - Small molecular drugs | -80°C to -20°C | [1,32,112] |

| - Organic (e.g., peptides) | -80°C to -20°C depending on stability | [1,32,112] | |

| Large Molecular / Biological | - Monoclonal antibodies | -80°C to -20°C | [114,126,127] |

| - Recombinant proteins | -80°C to -20°C | [113,114,115,126] | |

| - Therapeutic proteins | -80°C | [113,114,115,126] | |

| -Enzymes | -80°C to -20°C | [12,35,41,48] | |

| -Viruses | -80°C or -196°C | [10,64,68,91] | |

| - Antibodies against RNA lines | -80°C to -20°C | [44,123,132] | |

| Biological samples | - DNA/RNA | -196°C to -80°C | [145,146,147] |

| -Proteins | -80°C to -20°C | [64,68,91,108] | |

| Vaccines | - mRNA vaccines | -80°C to -60°C | [34,117,133] |

| Blood products | - Blood | -80°C or cooling (<4°C) | [2,134,135,136,137,138] |

| -Platelets | 4°C for short-term storage; -80°C for long-term storage | [2,134,135,136,137,138] | |

| Cell Culture | - Cell lines | -196°C to -80°C | [127,139,140,141] |

| - Fetal/stem cells | -196°C to -80°C | [127,139,140,141] | |

| Tissue Samples | - Fresh frozen samples | -196°C to -80°C | [143,144] |

| - Paraffin (formalin) samples | -80°C to -20°C (for long-term storage) | [143,144] | |

| Genetic material | - DNA plasmid | -80°C | [145,146,147] |

| - Oligodynamic | -80°C to -20°C | [145,146,147] | |

| Research samples | - Environment samples | -80°C | [148,149,150] |

| - Clinical samples | -80°C | [148,149,150] | |

| - Experimental observations | -196°C to -80°C | [148,149,150] | |

| Food (Perishables) | - Frozen fruits and vegetables | -40°C to -20°C (for long-term storage; in ultra-low freezers) | [12,35,41,48] |

| - Meat and seafood (frozen) | -30°C to -18°C | [12,35,41,48] | |

| - Dairy products (frozen) | -30°C to -20°C | [12,35,41,48] | |

| - Ready-to-eat frozen meals | -30°C to -18°C | [12,35,41,48] |

5. Advantages and Challenges of ULT Freezers

6. Advanced ULT Freezer Technologies

7. Regulatory Compliance

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamenski, G., Ayazseven, S., Berndt, A., & et al. (2020). Clinical relevance of CYP2D6 polymorphisms in patients of an Austrian medical practice: A family practice-based observational study. Drugs - Real World Outcomes, 7, 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Middelburg, R. A., Borkent, B., Jansen, M., van de Watering, L. M. G., Wiersum-Osselton, J. C., Schipperus, M. R., Beckers, E. A. M., & Briët, E. (2011). Storage time of blood products and transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhang, M., Gehl, A., Fricke, B., Nawaz, K., Gluesenkamp, K., Shen, B., Munk, J., Hagerman, J., & Lapsa, M. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine distribution solution to the last mile challenge: Experimental and simulation studies of ultra-low temperature refrigeration system. International Journal of Refrigeration, 133, 313-325. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q., Deng, B., Wang, Y., Liu, W., & Chen, G. (2023). Small, affordable, ultra-low-temperature vapor-compression and thermoelectric hybrid freezer for clinical applications. Cell Reports Physical Science, 4(101735). [CrossRef]

- Powell, S., Molinolo, A., Masmila, E., & Kaushal, S. (2019). Real-Time Temperature Mapping in Ultra-Low Freezers as a Standard Quality Assessment. Biopreservation and biobanking, 17(2), 139–142. [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, J. U., Saidur, R., & Masjuki, H. H. (2011). A review on exergy analysis of vapor compression refrigeration system. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 15(3), 1593-1600. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J. R., Ribeiro, G. B., & de Oliveira, P. A. (2011). A State-of-the-Art Review of Compact Vapor Compression Refrigeration Systems and Their Applications. Heat Transfer Engineering, 33(4–5), 356–374. [CrossRef]

- PHcbi (2024). Choosing a reliable ULT freezer: What you need to know. Retrieved from: https://www.phchd.com/us/biomedical/blog/choosing-a-reliable-ult-freezer-what-you-need-to-know?mtm_source=google&mtm_medium=cpc&mtm_campaign=21676150519&mtm_cid=21676150519&mtm_kwd=&mtm_content=&gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiAgdC6BhCgARIsAPWNWH3HWD6O4q4oY7PaoZsPUYSWoxC7salpyCivuOlz51WkYJ86su5nsRAaAgMxEALw_wcB [Accessed on 07DEC2024].

- Zhao, H., Hou, Y., & Chen, L. (2009). Experimental study on a small Brayton air refrigerator under −120°C. Applied Thermal Engineering, 29(8–9), 1702–1706. [CrossRef]

- Gondrand, C., Durand, F., Delcayre, F., Crispel, S., & Gistau Baguer, G. M. (2014). Overview of Air Liquide refrigeration systems between 1.8 K and 200 K. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1573(1), 949–956. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M., Zhao, H., Liang, D., Zhu, Y., Liang, Y., & Bao, G. (2020). A review of the cascade refrigeration system. Energies, 13(9), 2254. [CrossRef]

- Saravacos, G., & Kostaropoulos, A. E. (2016). Refrigeration and freezing equipment. In Handbook of food processing equipment (Food Engineering Series). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M. O., Azam, Q., Ahmad, S. T. I., Khan, F., & Wahid, M. A. (2021). Analysis of vapour compression refrigeration system with R-12, R-134a and R-22: An exergy approach. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46(Part 15), 6748-6752. [CrossRef]

- Mota-Babiloni, A., Mastani Joybari, M., Navarro-Esbrí, J., Mateu-Royo, C., Barragán-Cervera, Á., Amat-Albuixech, M., & Molés, F. (2020). Ultralow-temperature refrigeration systems: Configurations and refrigerants to reduce the environmental impact. International Journal of Refrigeration, 111, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.-Y., Ho, C.-Y., & Hsieh, J.-M. (2006). Condensation heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of R-290 (propane), R-600 (butane), and a mixture of R-290/R-600 in the serpentine small-tube bank. Applied Thermal Engineering, 26(16), 2045-2053. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Y., Kim, N.A., Lim, D.G. et al. Process cycle development of freeze drying for therapeutic proteins with stability evaluation. Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation 46, 519–536 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ye, W., Yan, Y., Zhou, Z., & Yang, P. (2024). Parametric analysis and performance prediction of an ultra-low temperature cascade refrigeration freezer based on an artificial neural network. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 55, 104162. [CrossRef]

- Berchowitz, D., & Kwon, Y. (2012). Environmental profiles of stirling-cooled and cascade-cooled ultra-low temperature freezers. Sustainability, 4(11), 2838–2851. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M. Z., Contiero, L., Blust, S., Allouche, Y., Hafner, A., & Eikevik, T. M. (2023). Ultra-low-temperature refrigeration systems: A review and performance comparison of refrigerants and configurations. Energies, 16(21), 7274. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H., Xu, L., Yang, L., Bai, M., & Liu, Z. (2022). Operation performance of an ultralow temperature cascade refrigeration freezer with environmentally friendly refrigerants R290-R170. University of Electronic Science and Technology of China Zhongshan Institute. [CrossRef]

- ISPE. (2016). Good practice guide: Controlled temperature chamber mapping and monitoring. International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

- ISPE. (2019). Commissioning and Qualification. Volume 5, 2nd Edition. International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering.

- Moerman, F., & Fikiin, K. (2016). Hygienic design of air-blast freezing systems. In Handbook of hygiene control in the food industry (2nd ed., pp. 271-316). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Meir, K., Cohen, Y., Mee, B., & Gafney, E. (2014). Biobank networking for dissemination of data and resources: An overview. J Bioreposit Sci Appl Med, 2, 29.

- Paradiso, A. V., Daidone, M. G., Canzonieri, V., & Zito, A. (2018). Biobanks and scientists: Supply and demand. Journal of Translational Medicine, 16(1), 136. [CrossRef]

- Scudellari, M. (2013). Biobank managers bemoan underuse of collected samples. Nature Medicine, 19(3), 253–263. [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, P., & Kumar, A. (2023). A situational based reliability indices estimation of ULT freezer using preventive maintenance under fuzzy environment. International Journal of Mathematical Engineering and Management Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Farley, M., McTier, B., Arnott, A., & Evans, A. (2015). Efficient ULT freezer storage. Social Responsibility & Sustainability: University of Edinburgh. Retrieved November 18, 2024 from https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/efficient_ult_freezer_storage.pdf.

- Hajagos, B. (2021). Life cycle assessment and emission reduction of cascade and Stirling ultra-low temperature freezers [Master’s thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology]. Retrieved November 18, 2024, from https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/183343183/1492306_MasterThesisBenceHajagos.pdf.

- Liu, J., Yu, J., & Yan, G. (2024). Experimental study on Joule-Thomson refrigeration system with R1150/R290/R601a for ultra-low temperature medical freezer. Applied Thermal Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R., Zhang, Y., Liu, X., & Yuan, Z. (2015). A life-cycle assessment of household refrigerators in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 15(95), 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Y., Cui, J. J., Liu, J. Y., & et al. (2018). Gene-gene and gene-environment interaction data for platinum-based chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Scientific Data, 5, Article 180284. [CrossRef]

- Authelin, J.-R., Rodrigues, M. A., Tchessalov, S., Singh, S. K., McCoy, T., Wang, S., & Shalaev, E. (2020). Freezing of biologicals revisited: Scale, stability, excipients, and degradation stresses. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 109(1), 44-61. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhang, M., Gehl, A., & et al. (2022). Dataset of ultralow temperature refrigeration for COVID-19 vaccine distribution solution. Scientific Data, 9, 67. [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Apenten, R. & Vieira, E.R. (2023). Chapter 13 Low-Temperature Preservation. In: Book elementary Food Science. Food Science Text Series. Springer, 5th edition, pp. 289-316. [CrossRef]

- Rees, J. (2013) Refrigeration nation: a history of ice, appliances, and enterprise in America. Retrieved from https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JeoEAQAAQBAJ.

- Gavroglu, K. (2014). Historiographical Issues in the History of Cold. In: Gavroglu, K. (eds) History of Artificial Cold, Scientific, Technological and Cultural Issues. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science, vol 299. Springer, Dordrecht. DOI. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.M. 1997. Safeguarded by your refrigerator: Mary Engle Pennington’s Struggle with the National Association of Ice Industries. In Rethinking home economics: Women and the history of a profession, ed. Sarah Stage and Virginia B. Vincenti, 253–270. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Pennington ME (1912) The hygienic and economic results of refrigeration in the conservation of poultry and eggs. Am J Public Health 2(11):840–848. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18008742.

- Thermo scientific (2024). Top considerations for selecting a ULT Freezer – application. Retrieved December 3, 2024 from: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LPD/Product-Information/Top-Considerations-ULT-Space-Constraints-TNTPCONSPACE-EN.pdf.

- Mallett, C. P. (1993). Frozen food technology. Springer. Retrieved from https://books.google.nl/books?hl=en&lr=&id=rzk9b3NpUzwC&oi=fnd&pg=PA20&dq=+William+Cullen+and+freezing&ots=1fbQor9ixv&sig=AhoQszLuugb-DMaNJxXQiGfpJ8g&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=William%20Cullen%20and%20freezing&f=false.

- Prasad, U. S., Mishra, R. S., & Das, R. K. (2024). Study of vapor compression refrigeration system with suspended nanoparticles in the low GWP refrigerant. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 31, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Thevenot, R. (1979). A history of refrigeration throughout the world. Trans. from French J.C. Fidler. Paris: International Institute of Refrigeration.

- Graham, M., Samuel, G. & Farley, M. Roadmap for low-carbon ultra-low temperature storage in biobanking. J Transl Med 22, 747 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. A. (Ed.). (2008). Frozen food science and technology. Blackwell Publishing. [CrossRef]

- James, C., Purnell, G. & James, S.J. A Review of Novel and Innovative Food Freezing Technologies. Food Bioprocess Technol 8, 1616–1634 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Koritsoglou, K., Christou, V., Ntritsos, G., Tsoumanis, G., Tsipouras, M. G., Giannakeas, N., & Tzallas, A. T. (2020). Improving the Accuracy of Low-Cost Sensor Measurements for Freezer Automation. Sensors, 20(21), 6389. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., & Sun, D.-W. (2006). Innovative applications of power ultrasound during food freezing processes—a review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 17(1), 16-23. [CrossRef]

- Richmond Scientific. (2022). Reducing the energy used by ULT freezers in the lab. Richmond Scientific. https://www.richmondscientific.com/reduce-energy-used-by-ult-freezers-in-the-lab.

- Robertson, J., Franzel, L., & Maire, D. (2017). Innovations in cold chain equipment for immunization supply chains. Vaccine, 35(17), 2252-2259. [CrossRef]

- Legett, R. (2014). Field demonstration of high-efficiency ultra-low-temperature laboratory freezers. Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: US Department of Energy; 2014. Available from: https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2014/11/f19/ult_ demo_ report.pdf.

- Faugeroux, D. (2016). Ultra-low temperature freezer performance and energy use tests. Office of Sustainability: University of California, Riverside. Retrieved from https://sustainability.ucsc.edu/engage/green-certified/green-labs/resources/Green%20Procurement/ucr2016_tempfreezertest.pdf.

- Keri, C. (2019). Chapter 13 - Recycling cooling and freezing appliances. In V. Goodship, A. Stevels, & J. Huisman (Eds.), Waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) handbook (2nd ed., pp. 357-370). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Powell, R. L. (2002). CFC phase-out: Have we met the challenge? Journal of Fluorine Chemistry, 114(2), 237-250. [CrossRef]

- Tica, G., & Grubic, A. R. (2019). Mitigation of climate change from the aspect of controlling F-gases in the field of cooling technology. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 477, 012056. [CrossRef]

- Benhadid-Dib, S., & Benzaoui, A. (2012). Refrigerants and their environmental impact: Substitution of hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC) and hydrofluorocarbon (HFC). Search for an adequate refrigerant. Energy Procedia, 18, 807-816. [CrossRef]

- Muir, E. B. (1990). Commercial refrigeration and CFCs. International Journal of Refrigeration, 13(2), 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Calderazzi, L., & Colonna di Paliano, P. (1997). Thermal stability of R-134a, R-141b, R-13I1, R-7146, R-125 associated with stainless steel as a containing material. International Journal of Refrigeration, 20(6), 381-389. [CrossRef]

- Finberg, E. A., & Shiflett, M. B. (2021). Process designs for separating R-410A, R-404A, and R-407C using extractive distillation and ionic liquid entrainers. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 60(44). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Li, W., Cernicin, V., & Hrnjak, P. (2024). Theoretical and experimental investigation on the effects of internal heat exchangers on a reversible automobile R744 air-conditioning system under various operating conditions. Applied Thermal Engineering, 236(Part B), 121569. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. W. (2004). The effect of blowing agent choice on energy use and global warming impact of a refrigerator. International Journal of Refrigeration, 27(7), 794–799. [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, E. W. (2003). Pseudo-pure fluid equations of state for the refrigerant blends R-410A, R-404A, R-507A, and R-407C. International Journal of Thermophysics, 24, 991–1006. [CrossRef]

- Liopis, R., Sánchez, D., Cabello, R., Catalán-Gil, J., & Nebot-Andrés, L. (2017). Experimental analysis of R-450A and R-513A as replacements of R-134a and R-507A in a medium temperature commercial refrigeration system. International Journal of Refrigeration, 84, 52-66. [CrossRef]

- Liopis, R., Calleja-Anta, D., Sánchez, D., Nebot-Andrés, L., Catalán-Gil, J., & Cabello, R. (2019). R-454C, R-459B, R-457A and R-455A as low-GWP replacements of R-404A: Experimental evaluation and optimization. International Journal of Refrigeration, 106, 133-143. [CrossRef]

- Komarov, S. G., & Stankus, S. V. (2011). Experimental study of speed of sound in gaseous refrigerant R-507A. High Temperature, 49, 150–153. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, V. S., Panwar, N. L., & Kaushik, S. C. (2012). Exergetic analysis of a vapour compression refrigeration system with R134a, R143a, R152a, R404A, R407C, R410A, R502, and R507A. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 14, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Graham, M., Samuel, G., & Farley, M. (2024). Roadmap for low-carbon ultra-low temperature storage in biobanking. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22, 747. [CrossRef]

- Choi, T. Y., Kim, Y. J., Kim, M. S., & Ro, S. T. (2000). Evaporation heat transfer of R-32, R-134a, R-32/134a, and R-32/125/134a inside a horizontal smooth tube. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 43(19), 3651-3660. [CrossRef]

- Ong, K. S., & Haider-E-Alahi, M. (2003). Performance of a R-134a-filled thermosyphon. Applied Thermal Engineering, 23(18), 2373-2381. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-H., & Kim, N.-H. (2021). Condensation heat transfer and pressure drop of low GWP R-404A-alternative refrigerants (R-448A, R-449A, R-455A, R-454C) in a 7.0-mm outer-diameter horizontal microfin tube. International Journal of Refrigeration, 126, 181-194. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. S., Mulroy, W. J., & Didion, D. A. (1994). Performance evaluation of two azeotropic refrigerant mixtures of HFC-134a with R-290 (propane) and R-600a (isobutane). ASME Journal of Energy Resources Technology, 116(2), 148–154. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-M., Gook, H.-H., Lee, S.-B., Lee, Y.-W., Park, D.-H., & Kim, N.-H. (2021). Condensation heat transfer and pressure drop of low GWP R-404A alternative refrigerants (R-448A, R-449A, R-455A, R-454C) in a 5.6 mm inner diameter horizontal smooth tube. International Journal of Refrigeration, 128, 71-82. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K., & Tae, S.-J. (2000). Evaporation heat transfer for R-22 and R-407C refrigerant–oil mixture in a microfin tube with a U-bend. International Journal of Refrigeration, 23(3), 219-231. [CrossRef]

- Cho, K., & Tae, S.-J. (2001). Condensation heat transfer for R-22 and R-407C refrigerant–oil mixtures in a microfin tube with a U-bend. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 44(11), 2043-2051. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H., Bae, S. W., Bang, K. H., & Kim, M. H. (2002). Experimental and numerical research on condenser performance for R-22 and R-407C refrigerants. International Journal of Refrigeration, 25(3), 372-382. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, Í. F., Pico, D. F. M., Santos, D. D. O., & Bandarra Filho, E. P. (2022). A review on the performance and environmental assessment of R-410A alternative refrigerants. Journal of Building Engineering, 47, 103847. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R. P. P. L., Sosa, J. E., Araújo, J. M. M., Pereiro, A. B., & Mota, J. P. B. (2023). Vacuum swing adsorption for R-32 recovery from R-410A refrigerant blend. International Journal of Refrigeration, 150, 253-264. [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Anta, D., Martínez-Ángeles, M., Nebot-Andres, L., Sánchez, D., & Llopis, R. (2024). Optimizing R152a/R600 and R290/R600 mixtures for superior energy performance in vapor compression systems: Promising alternatives to Isobutane (R600a). Applied Thermal Engineering, 247, 123070. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Ji, S., Tan, H., Yang, D., & Cao, Z. (2023). An ultralow-temperature cascade refrigeration unit with natural refrigerant pair R290-R170: Performance evaluation under different ambient and freezing temperatures. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress. [CrossRef]

- Udroiu, C.-M., Mota-Babiloni, A., & Navarro-Esbrí, J. (2022). Advanced two-stage cascade configurations for energy-efficient –80 °C refrigeration. Energy Conversion and Management, 267, 115907. [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.-Y., & Ho, C.-Y. (2005). Evaporation heat transfer and pressure drop characteristics of R-290 (propane), R-600 (butane), and a mixture of R-290/R-600 in the three-lines serpentine small-tube bank. Applied Thermal Engineering, 25(17-18), 2921-2936. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-S., Zawertailo, L., Piasecki, T. M., Kaprio, J., Foreman, M., Elliott, H. R., David, S. P., Bergen, A. W., Baurley, J. W., & Tyndale, R. F. (2018). Leveraging genomic data in smoking cessation trials in the era of precision medicine: Why and how. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 20(4), 414–424. [CrossRef]

- Jones, A., Wolf, A., & Kwark, S. M. (2022). Refrigeration system development with limited charge of flammable refrigerant, R-290. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 34, 101392. [CrossRef]

- Pilla, T. S., Sunkari, P. K. G., Padmanabhuni, S. L., Nair, S. S., & Dondapati, R. S. (2017). Experimental evaluation of mechanical performance of the compressor with mixed refrigerants R-290 and R-600a. Energy Procedia, 109, 113-121. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S., Ko, J., Lee, H., & Jeong, J. H. (2025). Advanced model for a non-adiabatic capillary tube considering both subcooled liquid and non-equilibrium two-phase states of R-600a. International Journal of Refrigeration, 169, 140-151. [CrossRef]

- Ye, G., Ye, M., Yang, J., Wu, X., Yan, Y., Guo, Z., & Han, X. (2024). Investigation on absorption and separation performance of R-32, R-125, R-134a, and R-1234yf refrigerants using EMIM-based ionic liquids. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Wang, N., Carlozo, M. N., Marin-Rimoldi, E., Befort, B. J., Dowling, A. W., & Maginn, E. J. (2023). Machine learning-enabled development of accurate force fields for refrigerants. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 19(14). [CrossRef]

- Midzic Kurtagic, S., Kadric, D., Alispahic, M., Blazevic, R., & Hadziahmetovic, H. (2022). Inventory of refrigerants in use for commercial purposes in BiH. In B. Katalinic (Ed.), Proceedings of the 33rd DAAAM International Symposium (pp. 143-150). DAAAM International. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Cheng-Min; Shen, Bo; Muneeshwaran, M; Nawaz, Kashif; Pickles, Ernest Calvin; and Hartnett, Christopher, "Performance Evaluation Of Various Configurations For Domestic Refrigerators With R-600a" (2024). International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Paper 2656. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc/2656.

- Yang, M.-H., & Yeh, R.-H. (2022). Investigation of the potential of R717 blends as working fluids in the organic Rankine cycle (ORC) for ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC). Energy, 245, 123317. [CrossRef]

- Fabris, F., Fabrizio, M., Marinetti, S., Rossetti, A., & Minetto, S. (2024). Evaluation of the carbon footprint of HFC and natural refrigerant transport refrigeration units from a life-cycle perspective. International Journal of Refrigeration, 159, 17-27. [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, B. B., Kriezi, E. E., Markussen, W. B., Kærn, M. R., Busch, A., & Kristófersson, J. (2025). Framework for prediction of two-phase R-744 ejector performance based on integration of thermodynamic models with multiphase mixture CFD simulations. Applied Thermal Engineering, 258(Part C), 124888. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H., Kim, J.-H., Heo, I.-Y., Yoon, J.-I., Son, C.-H., Nam, J.-W., Kim, H. J., Cha, S.-Y., & Seol, S.-H. (2024). Optimal charge amount for semiconductor chiller applying eco-friendly refrigerant R-744. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 59, 104461. [CrossRef]

- Macrì, C., De León, Á., & Flohr, F. (2024). Comparison of performance and efficiency of different refrigerants at high load conditions and their impact on CO2eq emissions. In CO2 Reduction for Transportation Systems Conference (pp. 1-7). Daikin Chemical Europe GmbH. [CrossRef]

- Söylemez, E. (2024). Energy and Conventional Exergy Analysis of an Integrated Transcritical CO2 (R-744) Refrigeration System. Energies, 17(2), 479. [CrossRef]

- Babushok, V. I., & Linteris, G. T. (2024). Air humidity influence on combustion of R-1234yf (CF3CFCH2), R-1234ze(E) (trans-CF3CHCHF), and R-134a (CH2FCF3) refrigerants. Combustion and Flame, 262, 113352. [CrossRef]

- Leehey, M. H., Kujak, S., & Collins, C. (2024). Chemical stability of HFO and HCO refrigerants. In International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference (Paper 2555). Purdue University. Retrieved January 4, 2025 from https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc/2555.

- Miyawaki, K., & Shikazono, N. (2024). Experimental evaluation of NIR spectroscopic characteristics of liquid R32, R1234yf, and R454C refrigerants. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 156, 107633. [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.-J., & Lee, J.-H. (2024). Heat transfer characteristics of R-1234yf, an eco-friendly alternative refrigerant, in condenser for semiconductor chiller. Applied Thermal Engineering, 239, 122106. [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, S., & Maddali, R. (2024). Effect of system configuration on the performance of a hybrid air conditioning system based on R-1234yf. Applied Thermal Engineering, 236(Part B), 121624. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Lakshmi, B. J., Yang, S.-Y., & Wang, C.-C. (2024). Effect of viscosity grade (POE) on the smooth-tube pool boiling performance with R-1234ze(E) refrigerant. Applied Thermal Engineering, 241, 122328. [CrossRef]

- Robaczewski, C., Leehey, M. H., & DeDeker, Z. (2024). Material compatibility of seal materials with low GWP refrigerants and lubricant. In International Compressor Engineering Conference (Paper 2826). Purdue University. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/icec/2826.

- Six, P., Valtz, A., Zhou, Y., Yang, Z., & Coquelet, C. (2024). Experimental measurements and correlation of vapor–liquid equilibrium data for the difluoromethane (R32) + 1,3,3,3-tetrafluoropropene (R1234ze(E)) binary system from 254 to 348 K. Fluid Phase Equilibria, 581, 114072. [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, A. (2020). The state-of-the-art on refrigerants. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1599, p. 012001). IOP Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Mickoleit, E., Breitkopf, C., & Jäger, A. (2021). Influence of equations of state and mixture models on the design of a refrigeration process. International Journal of Refrigeration, 121, 193-205. [CrossRef]

- Narute, S., Joshi, K., Rane, V., & Kokate, P. (2021). A brief review on development of refrigerants and their applications. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET), 8(7), 4885. http://www.irjet.net.

- Long, N. V. D., Lee, D. Y., Han, T. H., & et al. (2020). Purification of R-12 for refrigerant reclamation using existing industrial-scale batch distillation: Design, optimization, simulation, and experimental studies. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering, 37, 1823–1828. [CrossRef]

- Naskar, R., & Mandal, R. (2023). A competitive study of all natural refrigerants implementation on 1.5-ton domestic air conditioners using Cool Pack software. Industrial Engineering Journal, 52(9), No. 1. ISSN: 0970-2555.

- Petrick, G.M. (2006). The arbiters of taste: producers, consumers, and the industrialization of taste in America, 1900–1960. Doctoral dissertation, University of Delaware.

- McLinden, M. O., & Huber, M. L. (2020). (R)Evolution of refrigerants. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 65(9), 4176–4193. [CrossRef]

- Nederhand, R. J., Droog, S., Kluft, C., Simoons, M. L., de Maat, M. P., & Investigators of the EUROPA trial (2003). Logistics and quality control for DNA sampling in large multicenter studies. Journal of thrombosis and hemostasis: JTH, 1(5), 987–991. [CrossRef]

- Nasarabadi, S., Hogan, M., & Nelson, J. (2018). Biobanking in precision medicine. Current Pharmacology Reports, 4, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- She, R. C., & Petti, C. A. (2015). Procedures for the storage of microorganisms. In J. H. Jorgensen, K. C. Carroll, G. Funke, M. A. Pfaller, M. L. Landry, S. S. Richter, & D. W. Warnock (Eds.), Manual of clinical microbiology (11th ed.). American Society for Microbiology Press. [CrossRef]

- Karim, A. S., & Jewett, M. C. (2018). Cell-free synthetic biology for pathway prototyping. In Methods in enzymology (Vol. 608, pp. 31-57). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Landor, L. A. I., Stevenson, T., Mayers, K. M. J., & et al. (2024). DNA, RNA, and prokaryote community sample stability at different ultra-low temperature storage conditions. Environmental Sustainability, 7, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Bao, J., & Zhao, L. (2016). Experimental research on the influence of system parameters on the composition shift for zeotropic mixture (isobutane/pentane) in a system occurring phase change. Energy Conversion and Management, 113, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G. F. (2021). The Low Down on Ultralow Temperature Freezers. Endocrine News,40+. Retrieved February 9, 2025 from https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A688004802/AONE?u=anon~103b3ad0&sid=googleScholar&xid=d263f033.

- Ajmani, P. S. (2020). Storage of blood. In Immunohematology and blood banking (pp. 1-15). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Sato, K., Tamaki, K., Okajima, H., & Katsumata, Y. (1988). Long-term storage of blood samples as whole blood at extremely low temperatures for methemoglobin determination. Forensic science international, 37(2), 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W., Hu, Z., Muallem, H., & Gulley, M. L. (2012). Quality assurance of RNA expression profiling in clinical laboratories. The Journal of molecular diagnostics: JMD, 14(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Johnson, R., Yu, G., McKenna, D. H., & Hubel, A. (2019). Preservation of cell-based immunotherapies for clinical trials. Cytotherapy, 21(9), 943-957. [CrossRef]

- Shabihkhani, M., Lucey, G. M., Wei, B., Mareninov, S., Lou, J. J., Vinters, H. V., Singer, E. J., Cloughesy, T. F., & Yong, W. H. (2014). The procurement, storage, and quality assurance of frozen blood and tissue biospecimens in pathology, biorepository, and biobank settings. Clinical biochemistry, 47(4-5), 258–266. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S., & Molinolo, A. (2021). Potential use of College of American Pathologists accredited biorepositories to bridge unmet need for medical refrigeration using ultralow temperature storage for COVID-19 vaccine or drug storage. Biopreservation and Biobanking, 19(3). [CrossRef]

- Cabra, J., Castro, D., Colorado, J., Mendez, D., & Trujillo, L. (2017). An IoT approach for wireless sensor networks applied to e-health environmental monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings), IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom), IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom), and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) (pp. 578-583). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, G., & Sims, J. M. (2023). Drivers and constraints to environmental sustainability in UK-based biobanking: Balancing resource efficiency and future value. BMC Medical Ethics, 24(1).

- Isaacs, E., & Schmelz, M. (2017). Come in out of the cold: Alternatives to freezing for microbial biorepositories. Clinical Microbiology Newsletter, 39(4), 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, J. R., Brooks, S. M., Kennedy, Z. C., Pope, T. R., Deatherage Kaiser, B. L., Victry, K. D., Warner, C. L., Oxford, K. L., Omberg, K. M., & Warner, M. G. (2019). Polysaccharide-based liquid storage and transport media for non-refrigerated preservation of bacterial pathogens. PLOS ONE, 14(9), Article e0221831. [CrossRef]

- Grasedieck, S., Schöler, N., Bommer, M., Niess, J. H., Tumani, H., Rouhi, A., Bloehdorn, J., Liebisch, P., Mertens, D., Döhner, H., Buske, C., Langer, C., & Kuchenbauer, F. (2012). Impact of serum storage conditions on microRNA stability. Leukemia, 26(11), 2414–2416. [CrossRef]

- Groelz, D., Sobin, L., Branton, P., Compton, C., Wyrich, R., & Rainen, L. (2013). Non-formalin fixative versus formalin-fixed tissue: a comparison of histology and RNA quality. Experimental and molecular pathology, 94(1), 188–194. [CrossRef]

- Lou, J. J., Mirsadraei, L., Sanchez, D. E., Wilson, R. W., Shabihkhani, M., Lucey, G. M., Wei, B., Singer, E. J., Mareninov, S., & Yong, W. H. (2014). A review of room temperature storage of biospecimen tissue and nucleic acids for anatomic pathology laboratories and biorepositories. Clinical Biochemistry, 47(4–5), 267-273. [CrossRef]

- Shehu, D., Kim, M.-O., Rosendo, J., Krogan, N., Morgan, D. O., & Guglielmo, B. J. (2024). Institutional conversion to energy-efficient ultra-low freezers decreases carbon footprint and reduces energy costs. Biopreservation and Biobanking. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A., Graves, S., & Murray, T. (2001). The Biophile sample process management system — Automated sample access at ultra low temperatures. SLAS TECHNOLOGY: Translating Life Sciences Innovation, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Kasi, P., & Cheralathan, M. (2021). Review of cascade refrigeration systems for vaccine storage. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2054, Article 012041. [CrossRef]

- Bakaltcheva, I., & Reid, T. (2003). Effects of blood product storage protectants on blood coagulation. Transfusion Medicine Reviews, 17(4), 263-271. [CrossRef]

- Greening, D. W., Glenister, K. M., Sparrow, R. L., & Simpson, R. J. (2010). International blood collection and storage: Clinical use of blood products. Journal of Proteomics, 73(3), 386-395. [CrossRef]

- Hess, J. R. (2010). Conventional blood banking and blood component storage regulation: Opportunities for improvement. Blood Transfusion, 8(Suppl 3), s9-15. [CrossRef]

- Radin, J. (2017). Life on ice: A history of new uses for cold blood. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Sperling, S., Vinholt, P. J., Sprogøe, U., Yazer, M. H., Frederiksen, H., & Nielsen, C. (2019). The effects of storage on platelet function in different blood products. Hematology, 24(1), 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Du, C., Xu, J., Song, H., Tao, L., Lewandowski, A., Ghose, S., Borys, M. C., & Li, Z. J. (2019). Mechanisms of color formation in drug substance and mitigation strategies for the manufacture and storage of therapeutic proteins produced using mammalian cell culture. Process Biochemistry, 86, 127-135. [CrossRef]

- Kao, G. S., Kim, H. T., Daley, H., Ritz, J., Burger, S. R., Kelley, L., Vierra-Green, C., Flesch, S., Spellman, S., Miller, J., & Confer, D. (2011). Validation of short-term handling and storage conditions for marrow and peripheral blood stem cell products. Transfusion, 51(5), 1129-1138. [CrossRef]

- Sugrue, M. W., Hutcheson, C. E., Fisk, D. D., Roberts, C. G., Mageed, A., Wingard, J. R., & Moreb, J. S. (2009). The effect of overnight storage of leukapheresis stem cell products on cell viability, recovery, and cost. Journal of Hematotherapy, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Jewell, S. D., Srinivasan, M., McCart, L. M., Williams, N., Grizzle, W. H., LiVolsi, V., MacLennan, G., & Sedmak, D. D. (2002). Analysis of the molecular quality of human tissues: an experience from the Cooperative Human Tissue Network. American journal of clinical pathology, 118(5), 733–741. [CrossRef]

- Mager, S. R., Oomen, M. H. A., Morente, M. M., Ratcliffe, C., Knox, K., Kerr, D. J., Pezzella, F., & Riegman, P. H. J. (2007). Standard operating procedure for the collection of fresh frozen tissue samples. European Journal of Cancer, 43(5), 828-834. [CrossRef]

- Troyer, D. (2008). Biorepository Standards and Protocols for Collecting, Processing, and Storing Human Tissues. In: Liu, B.CS., Ehrlich, J.R. (eds) Tissue Proteomics. Methods in Molecular Biology™, vol 441. Humana Press. [CrossRef]

- International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories (ISBER). (2008). Collection, storage, retrieval, and distribution of biological materials for research. Cell Preservation Technology, 6(1). [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L. E., Bouley, T. A., & McCulloch, C. E. (2010). Genetic research with stored biological materials: Ethics and practice. IRB, 32(2), 7-18. Retrieved April 1, 2025 from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3052851/.

- Zimkus, B. M., & Ford, L. S. (2014). Best practices for genetic resources associated with natural history collections: Recommendations for practical implementation. Collection Forum, 28(1-2), 77–112. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, M. A., & Halbert, G. W. (2005). Maintaining the cold chain shipping environment for Phase I clinical trial distribution. International Journal of Pharmaceutics, 299(1–2), 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Harada, L. M., Rodrigues, E. F., Ferreira, W. de P., Maniçoba da Silva, A., & Kawamoto Júnior, L. T. (2016). Storage management of clinical research supplies of a phase IIB/III, national, multi-centre, double-blind and randomized study. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 13, 430-441. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. C., Qiu, F., Cohen, K., & et al. (2012). Best practices for drug substance stress and stability studies during early-stage development Part I—Conducting drug substance solid stress to support phase Ia clinical trials. Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation, 7, 214–224. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J., Lydon, P., Ouhichi, R., & Zaffran, M. (2015). Reducing the loss of vaccines from accidental freezing in the cold chain: the experience of continuous temperature monitoring in Tunisia. Vaccine, 33(7), 902–907. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Bai, M., Tan, H., Ling, Y., & Cao, Z. (2023). Experimental test on the performance of a −80 °C cascade refrigeration unit using refrigerants R290-R170 for COVID-19 vaccines storage. Journal of Building Engineering, 63(A), 105537. [CrossRef]

- Groover, K., Kulina, L., & Franke, J. (2009). Effect of increasing thermal mass on chamber temperature stability within ultra-low freezers in bio-repository operations. https://biospecimens.cancer.gov/meeting/brnsymposium/2009/docs/posters/poster%2015%20groover.pdf.

- Rogers, J., Carolin, T., Vaught, J., & Compton, C. (2011). Biobankonomics: A taxonomy for evaluating the economic benefits of standardized centralized human biobanking for translational research. JNCI Monographs, 2011(42), 32–38. [CrossRef]

- Labmode. (2023). Nordic Modular ULT Freezer System. Labmode. https://labmode.co.uk/product/nordic-modular-ult-freezer-system/.

- International Organization for Standardisation. (2018). ISO 14067:2018 - Greenhouse Gases-Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardisation.

- Muenz, R. (2021). How to operate and maintain an ultralow temperature freezer. Lab Manager. https://www.labmanager.com/big-picture/lab-ultralow-cold-storage/how-to-operate-and-maintain-an-ultralow-temperature-freezer-24970.

- Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme. (2023). Guide to good manufacturing practice for medicinal products part I (PE 009-17). PIC/S Secretariat. Retrieved April 6, 2025, from https://www.picscheme.org.

- Tsimpoukis, D., Syngounas, E., Bellos, E., Koukou, M., Tzivanidis, C., Anagnostatos, S., & Vrachopoulos, M. G. (2024). Data-driven energy efficiency comparison between operating R744 and R448A supermarket refrigeration systems based on hybrid experimental-simulation analysis. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 53, 102776. [CrossRef]

- McColloster, P. J., & Martin-de-Nicolas, A. (2014). Vaccine refrigeration: thinking outside of the box. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 10(4), 1126–1128. [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P., Pries, J., Wei, S., & Wuttig, M. (2022). The glass transition of water, insight from phase change materials. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 1(14), 100084. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Pan, X., Liao, X., & Xing, Z. (2022). A data-driven energy management strategy based on performance prediction for cascade refrigeration systems. International Journal of Refrigeration, 136, 114-123. [CrossRef]

- Gumapas, L. A. M., & Simons, G. (2013). Factors affecting the performance, energy consumption, and carbon footprint for ultra low temperature freezers: Case study at the National Institutes of Health. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 10(123), 129. [CrossRef]

- Koncept Media. (n.d.). Model K66 HPL [PDF]. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.konceptmedia.hr/admin/dokumenti/docfiles/model-K66-HPL.pdf.

- Stirling Ultracold. (n.d.). SU780XLE operating manual (Version 061824P). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.stirlingultracold.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/SU780XLE_Operating_Manual_Stirling_Ultracold_061824P.pdf.

- Klinge Corporation. (2019). PTI NMF-372 Prod 063 Rev C [PDF]. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://klingecorp.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/PTI-Form-NMF-372-Prod-063-Rev-C.pdf.

- WHO. (2014). Temperature mapping of storage areas. World Health Organization, Technical Report Series, No. 961, 2011 Annex 9.

- WHO. (2015). Temperature mapping of storage areas. World Health Organization, Technical Report Series, No. 961, 2011, Supplement 8.

- Human Tissue Authority. (2023). How licensing works under the Human Tissue Quality and Safety Regulations. Human Tissue Authority. https://www.hta.gov.uk/guidance-professionals/licences-roles-and-fees/licensing/how-licensing-works-under-human-tissue.

- European Commission. (2011). Eudralex - volume 4: Good manufacturing practice (GMP) guidelines. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from URL https://health.ec.europa.eu/medicinal-products/eudralex/eudralex-volume-4_en.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024a). Title 21--Food and drugs, Chapter I--Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, Subchapter A - General, Part 11 Electronic records; electronic signatures. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=11.

- European Commission. (2015). Guidelines of 19 March 2015 on principles of good distribution practice of active substances for medicinal products for human use (Text with EEA relevance) (2015/C 95/01). Retrieved April 10, 2025, from URL https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015XC0321(01).

- European Parliament & Council. (2000). Directive 2000/54/EC of 18 September 2000 on the protection of workers from risks related to exposure to biological agents at work (seventh individual directive within the meaning of Article 16(1) of Directive 89/391/EEC). OJ L 262, 17.10.2000, pp. 21–45. Retrieved April 10, 2025 from http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/54/oj.

- European Medicines Agency. (2016). Guideline on process validation for finished products - information and data to be provided in regulatory submissions (EMA/CHMP/CVMP/QWP/BWP/70278/2012-Rev1,Corr.1). Retrieved April 10, 2025 from https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-process-validation-finished-products-information-data-be-provided-regulatory-submissions_en.pdf.

- European Parliament & Council. (2009). Directive 2009/41/EC of 6 May 2009 on the contained use of genetically modified micro-organisms (Recast) (Text with EEA relevance). OJ L 125, 21.5.2009, pp. 75–97. Retrieved April 09, 2025 from http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/41/oj.

- Evans, A. (2022). ULT Freezer Best Practice: Impacts. Green Light Labs. Retrieved April 09, 2025 from https://www.scientificlabs.co.uk/file/1991/Defrost%20the%20Freezer%20Regularly%20to%20Prevent%20a%20Build-up%20of%20Frost.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024b). Title 21--Food and drugs, Chapter I--Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, Subchapter C - Drugs: General, Part 210 Current good manufacturing practice in manufacturing, processing, packing, or holding of drugs; general. Retrieved from URL The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (2024). Bioprocessing Equipment. Retrieved April 15, 2025 from https://files.asme.org/Catalog/Codes/PrintBook/35606.pdf.

- Kypraiou, C. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Temperature Uniformity and Efficiency in Low Temperature Refrigeration Systems of Hermetic Compressor, Free Piston Engine and Multicompressors (Unpublished master's thesis). Hellenic Open University, Master Thesis.

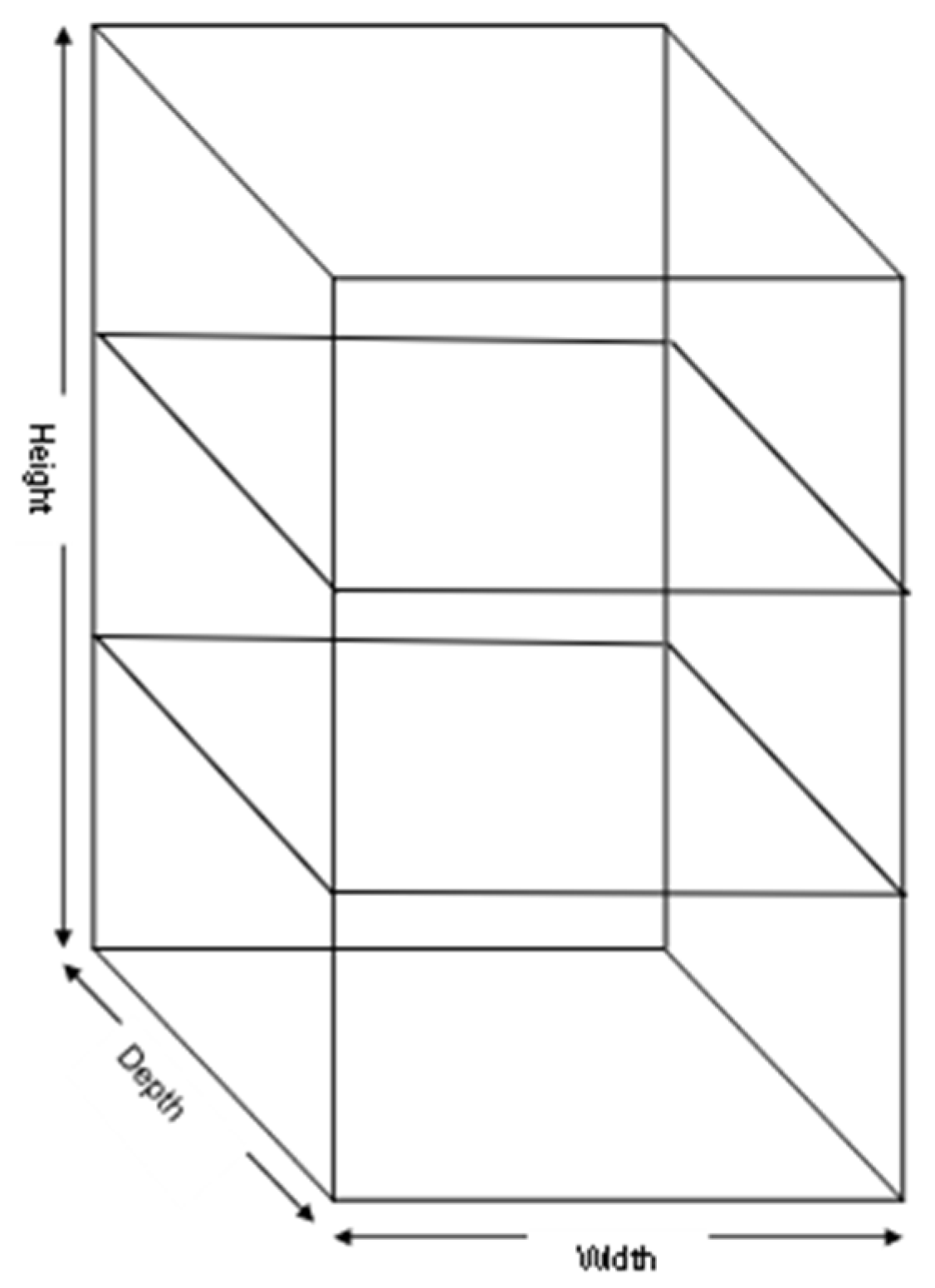

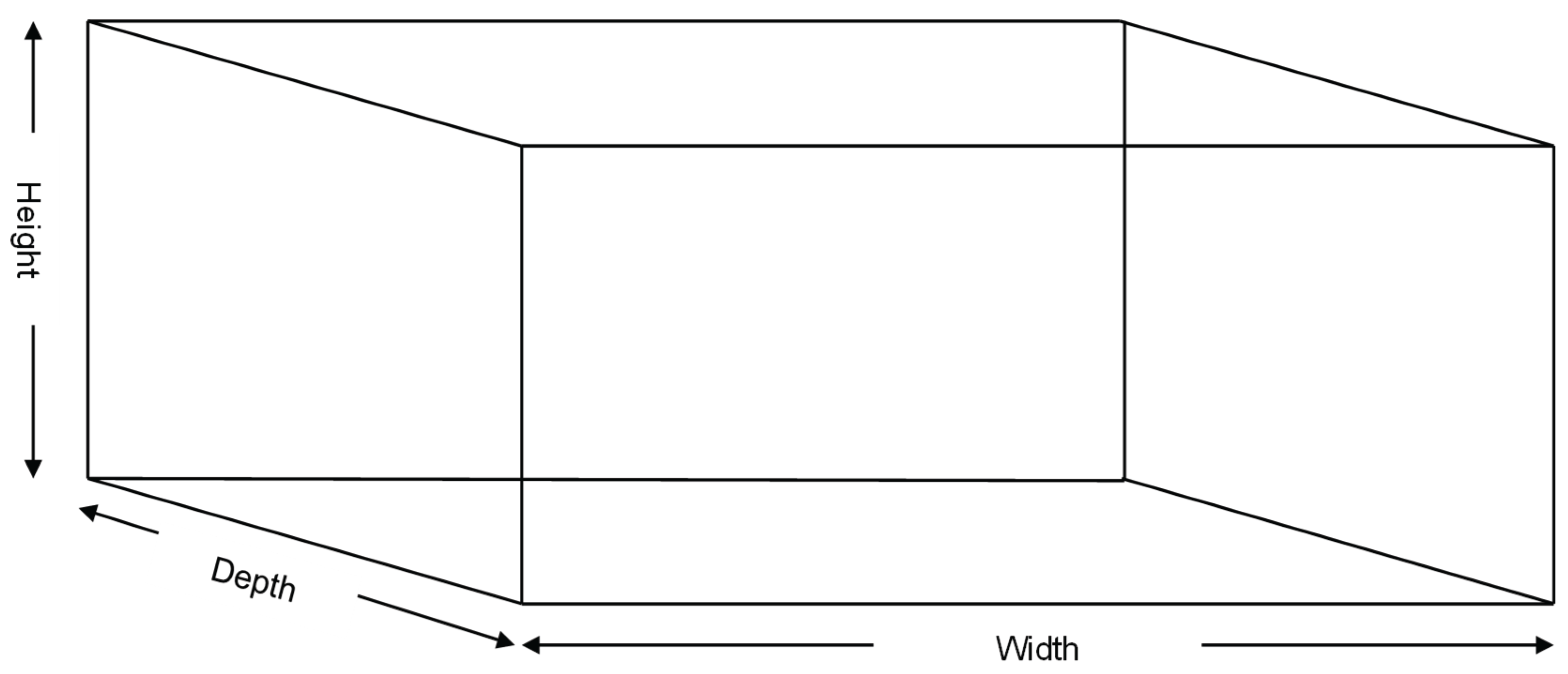

| Features | Hermetic Compressor | Free Piston Engine | Multi-compressors |

|---|---|---|---|

| References | [164,165,166] | [164,165,166] | [164,165,166] |

| Capacity | 706 liters | 780 liters | 59,720 liters |

| Temperature Range | -40°C to -85°C | -20°C to -86°C | 0°C to -60°C |

| Construction Material | AISI 304 Stainless Steel | Blank insulation panels | Special design with two systems |

| Cooling Technology | Hermetic compressors | Free-piston Stirling | Dual cooling system |

| Energy Consumption | Energy Saving Strategies | ~6.67 kWh/d, up to 40% less energy | Requires maintenance for stable operation |

| Connectivity | USB, SIM, Wi-Fi, Ethernet | Remote Monitoring | Limited options |

| Temperature Stability | Superior thermal performance | ± 1 °C | Constant temperature control |

| Operating Safety | Safety thermostats | Lock and PIN for access | Diagnostics and Warnings |

| Maintenance Procedures | Regular programs necessary | Maintenance with GUI and automated monitoring | Regular maintenance and checks with automated diagnostics |

| Useful Life | 10-12 years | 12 years | 10-12 years |

| Refrigerant Safety | HCFC or CFC freeΦR-170 and R-1270 | Uses R-170 (Ethane), eco-friendly | Uses HFCs, requires caution due to flammability |

| Operating Noise | Noise during operation | <48 dB(A) | Noise during operation |

| Environmental policy | Eco-friendly refrigerants | Uses natural refrigerants | Low ozone depletion potential |

| Resistance to Temperature Fluctuations | High | High | High via dual compressors |

| Reliability Price | High reliability | Variable operation with minimal maintenance | Excellent due to redundancy |

| Measurement | 1990x1060x1000 mm | 1994x870x915 mm | 10945x2154x2896 mm |

| Source | Title of the Regulation | Article | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| EU | Eudralex; Volume 4 GMP Guidelines | Volume 4 | [170] |

| Good Distribution Practice of active substances for medicinal products for human use (2015/C 95/01) | 2015/C 95/01 | [172] | |

| Directive 2000/54/EC Protection of Workers from Risks Related to Exposure to Biologic Agents at Work | 2000/54/EC Annex V&VI | [173] | |

| Directive 2009/41/EC on the contained use of genetically modified micro-organisms | 2009/41/EC | [175] | |

| European Medicines Agency scientific guidance documents on biological drug substances | N/A | [174] | |

| US FDA | Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, Electronic Records & Electronic Signatures | Part 11 | [171] |

| Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Processing, Packing or Holding of Drugs; General | Part 210 | [177] | |

| Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceuticals | Part 211 | [17][] | |

| ASME | Bioprocessing Equipment | ASME BPE-2014 | [158] |

| PIC/S | Guide to Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products, Part I | PE-009-9 | [158] |

| Guide to Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products, Part II | PE-009-11 | [158] | |

| ISPE | Baseline Guide: Biopharmaceuticals | Volume 6. 2nd | [21,22] |

| Baseline Guide: Commissioning and Qualification | Volume 5, 2nd | [21,22] | |

| Good Practice Guide -Cold Chain Management | 2011 | [21,22] | |

| Good Practice Guide – Controlled Temperature Chamber Mapping and Monitoring | 2016 | [21,22] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).