Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

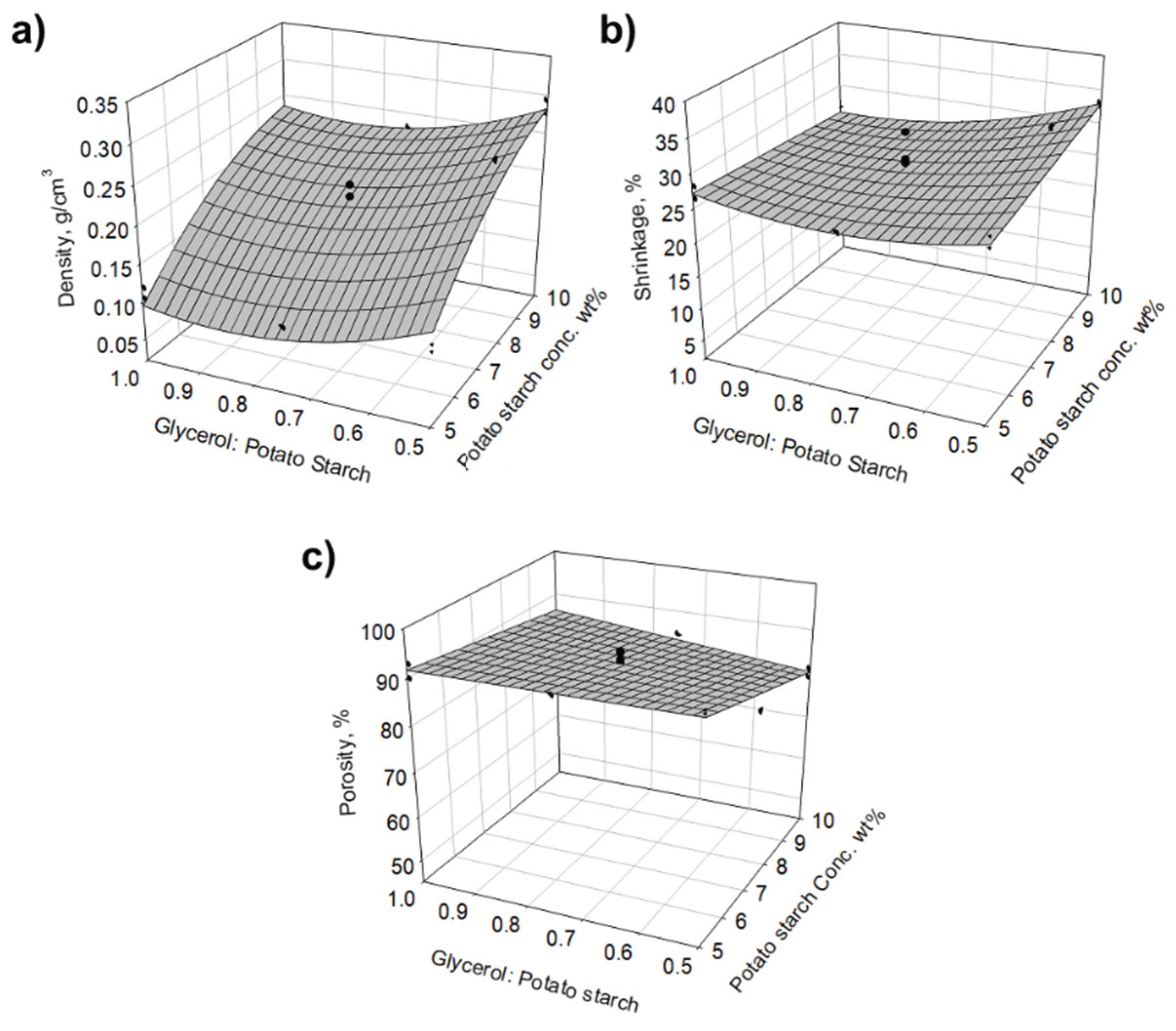

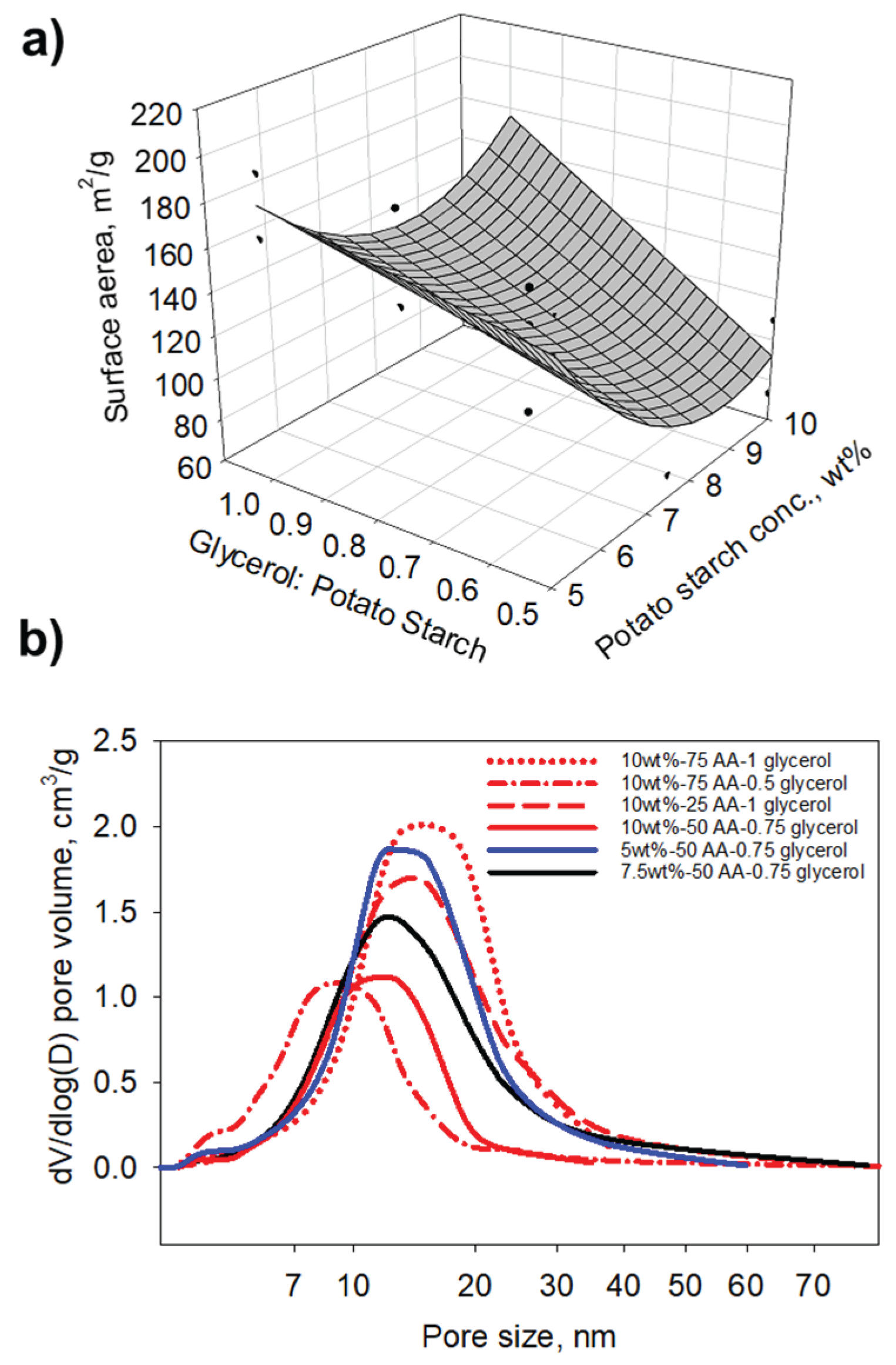

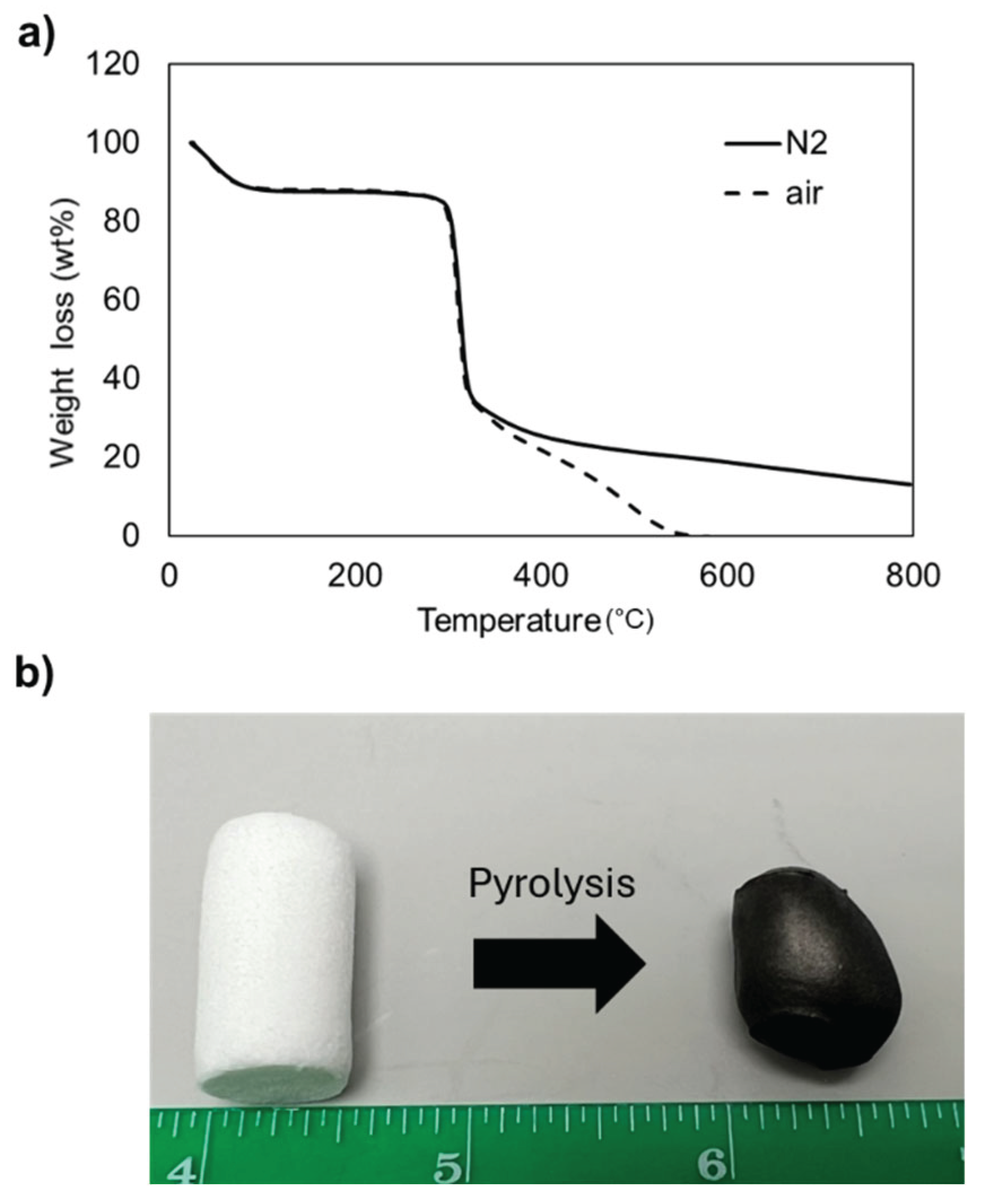

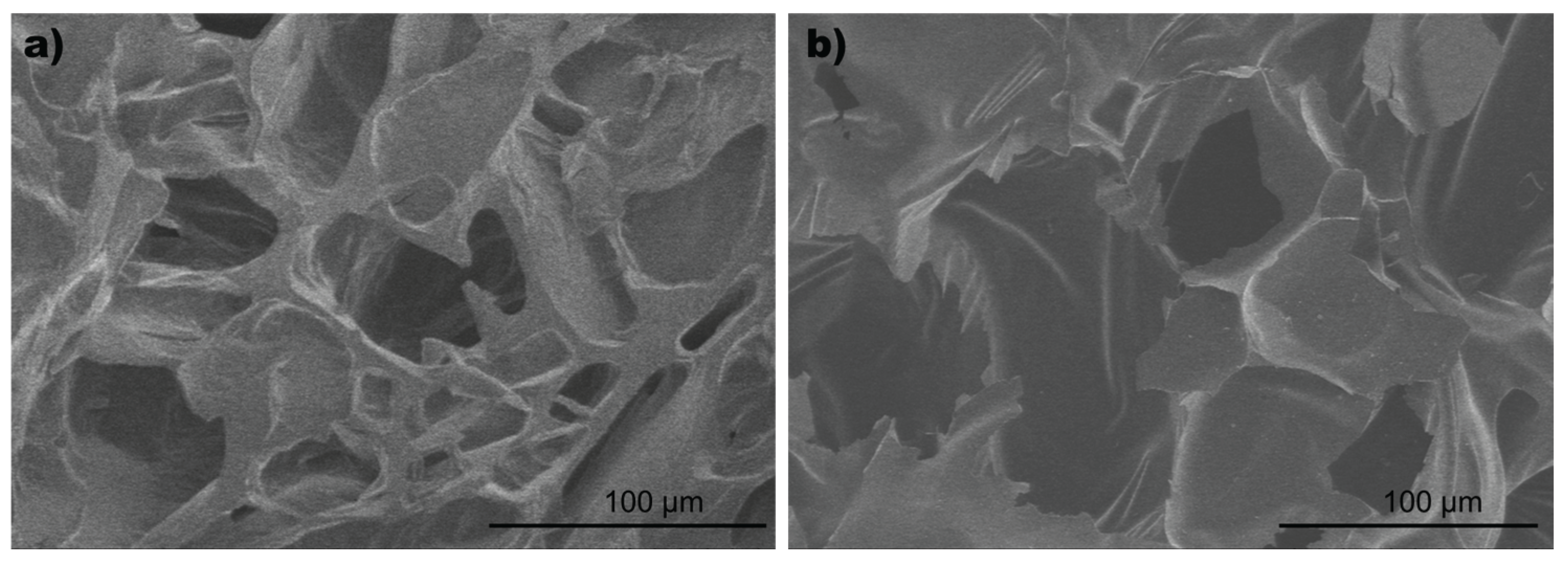

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials Used for Aerogel Formulations

4.2. Method for Fabricating Aerogel Including Supercritical Drying

4.3. Experimental Design and Analysis

4.4. Bulk Density, Shrinkage and Porosity Determination

4.5. Instrument Characterization

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bheekhun, N.; Talib, A. R. A.; Hassan, M. R. Aerogels in aerospace: An overview. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 406065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorchen, A. S.; Abbasi, M. H. Silica aerogel; synthesis, properties and characterization. J. Mater. Proc. Tech. 2008, 199, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. M.; Sagu, J. S.; KG, U. W.; Lobato, K. State-of-the-art materials for high power and high energy supercapacitors: Performance metrics and obstacles for the transition from lab to industrial scale – A critical approach. 2019, 374, 1153–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Meador, M. A. B.; McCorkle, L.; Quade, D. J.; Guo, J.; Hamilton, B.; Cakmak, M.; Sprow, G. Polyimide Aerogels Cross-Linked through Amine Functionalized Polyoligomeric Silsesquioxane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiman, D. A.; Guo, H.; Oosterbaan, K. J.; McCorkle, L.; Nguyen, B.N. Synthesis of Polyamide Aerogels Cross-Linked with a Tri-isocyanate. Gels 2024, 10, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merillas, B.; León, J. M.; Villafañe, F.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M. A. Transparent Polyisocyanurate-Polyurethane-Based Aerogels: KeyAspects on the Synthesis and Their Porous Structures. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 4607–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce III, W. E.; Mesick, N. J.; Ferlemann, P. G.; Siemers III, P. M.; Del Corso, J. A.; Hughes, S. J.; Tobin, S. A.; Kardell, M. Aerothermal Ground Testing of Flexible Thermal Protection Systems for Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerators. 9th International Planetary Probe Workshop, Toulouse, France, 16-22 JUNE 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mi, H.-Y.; Jing, X.; Meador, M. A. B.; Guo, H.; Turng, L.-S.; Gong, S. Triboelectric Nanogenerators Made of Porous Polyamide Nanofiber Mats and Polyimide Aerogel Film: Output Optimization and Performance in Circuits. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 30596–30606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Meador, M.A. B.; Cashman, J. L.; Tresp, D.; Dosa, B.; Scheiman, D. A.; McCorkle, L. S. Flexible Polyimide Aerogels with Dodecane Links in the Backbone Structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 33288–33296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlis,A. ; Guo, H.; Helson, K.; Bennett, C.; Chan, C. Y. Y.; Marriage, T.; Quijada, M.; Tokarz, A.; Vivod, S.; Wollack, E.; Essinger-Hileman, T. Fabrication and characterization of optical filters from polymeric aerogels loaded with diamond scattering particles. Applied Optics 2024, 63, 6036–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Croft, Z.; Guo, D.; Cao, K.; Li, G. Recent development of polyimides: Synthesis, processing,and application in gas separation. J. Poly. Sci. 2021, 59, 943–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- n-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP); Revision to Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Risk Determination; Notice of Availability. Environmental Protection Agency. 87 FR 77596, 2022-27438, 12/19/2022, 77596-77602.

- Wang, Y. , Airborne hydrophilic microplastics in cloud water at high altitudes and their role in cloud formation. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2023, 21, 3055–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Saxena D. C.; A Review on Starch Aerogel: Application and Future Trends. 8th International Conference on Advancements in Engineering and Technology, (ICAET-2020) BGIET, Sangrur, ISBN No: 978-81-924893-5-3.

- Huang, S.; Chao, C.; Yu, J. Coperland, L.; Wang, S. New insight into starch retrogradation: The effect of short-range molecular order in gelatinized starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 120, 106921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiamjariyatam, R.; Kongpensook, V.; Pradipasena, P. ; Effects of amylose content, cooling rate and aging time on properties and characteristics of rice starch gels and puffed products. J. of Cereal Sci. 2014, 61, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Budtova, T. ; Tailoring the morphology and properties of starch aerogels and cryogels via starch source and process parameter. Carbohydrate Polymers 2021, 255, 117344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druel, L.; Bardl, R.; Vorwerg, W.; Budtova, T. Starch aerogels: A member of the family of thermal superinsulating materials. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4232–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; De Marco, I. Supercritical CO2 adsorption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs into biopolymer aerogels. J. CO2 Utilization 2020, 36, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, J. F.; Osella, C. A.; Carrara, C. R.; Sa´ nchez, H. D.; Buera, M. del P. Effect of storage temperature on starch retrogradation of bread staling. Starch/Sta¨rke 2011, 63, 587–593. [CrossRef]

- Staker. J.; White, G. M.; Pasilova, S.; Scheiman, D. A.; Guo, H.; Tovar, A.; Siegel, A. P. Mitigating Shrinkage and Enhancing Structure of Thermally Insulating Starch Aerogel via Solvent Exchange and Chitin Ad-dition. Macromol submitted.

- Hu, L.; He, R.; Lei,H. ; Fang, D. Carbon Aerogel for Insulation Applications: A Review. International Journal of Thermophysics 2019, 40, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazi, H.; Fathi, F.; Dadkhah, A. Hydrophobically modified starch using long-chain fatty acids for preparation of nanosized starch particles. Scientia Iranica 2011, 18, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Corker, J.; Papathanasiou, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Madyan, O. M.; Liao, F.; Fan, M. Critical review on the thermal conductivity modelling of silica aerogel composites. J. of Building Engineering 2022, 57, 104814–104840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Du, D.; Feng, J. Study on Thermal Conductivities of Aromatic Polyimide Aerogels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 12992–12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lu, J.; Xi, S.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Fan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, J.; Zhou, B.; Du, A. Direct 3D print polyimide aerogels for synergy management of thermal insulation, gas permeability and light absorption. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 21272–21284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Waang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Z., Ji, H.; Xu, G.; Xiong, S.; Li, Z.; Ding F. Polyimide Aerogels with Excellent Thermal Insulation, Hydrophobicity, Machinability, and Strength Evolution at Extreme Conditions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 8227–8237. [CrossRef]

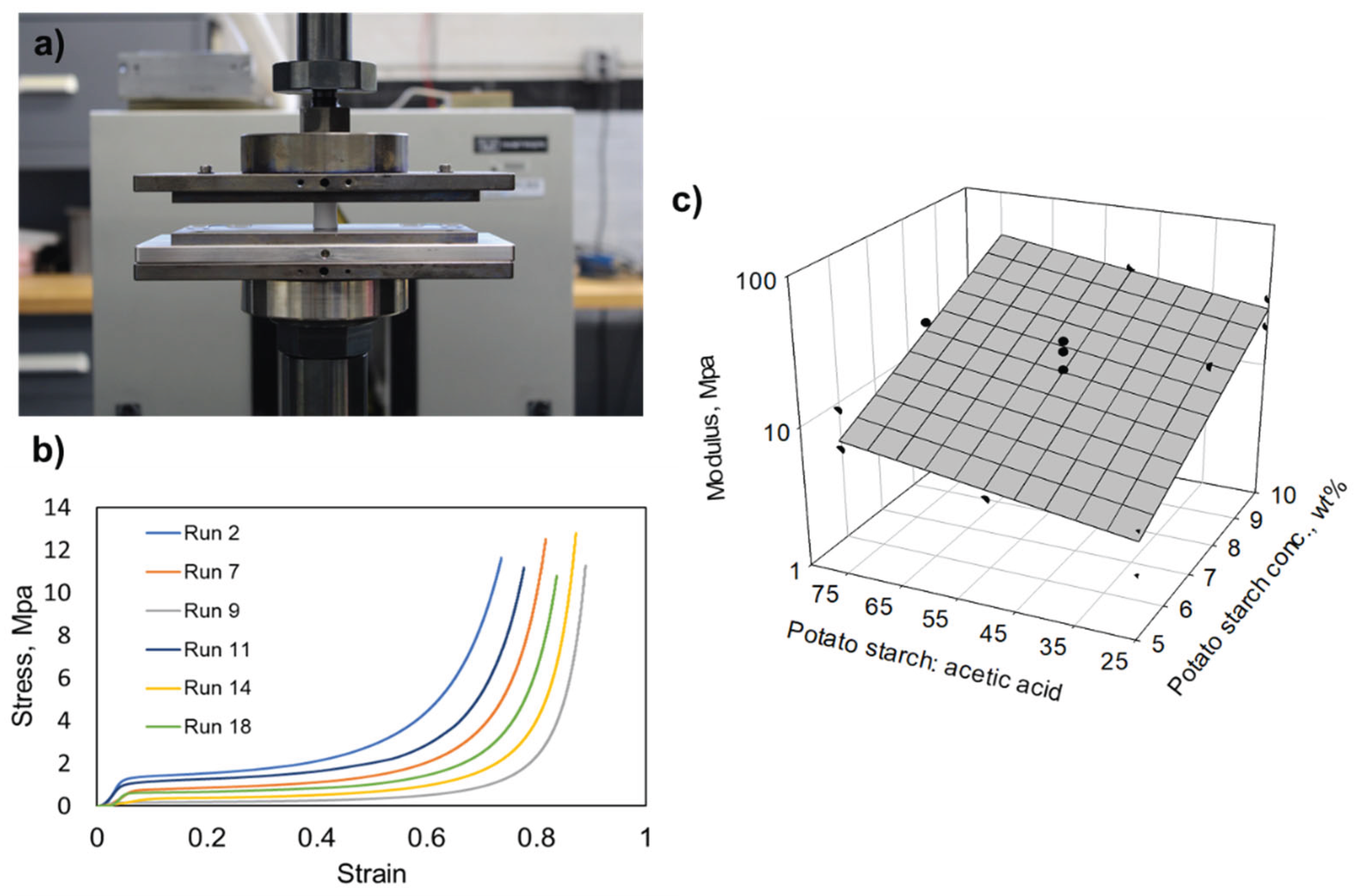

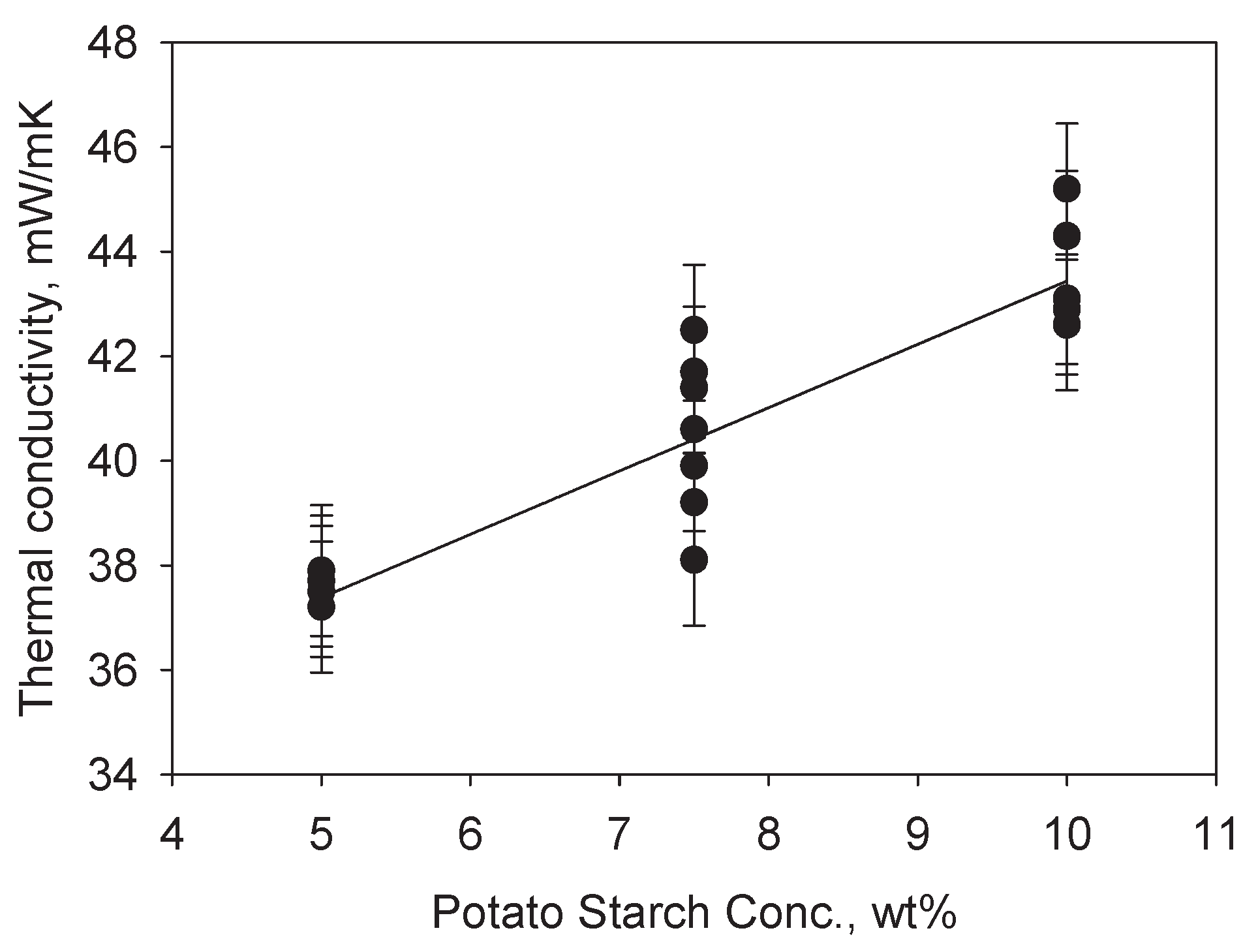

| Run | Potato Starch, wt% | Potato starch: Acetic acid | Glycerol: potato starch |

Density, g/cm3 | Shrinkage, % | Porosity, % | Surface area, m2/g | Young’s modulus, MPa | Thermal conductivity, mW/mK |

| 1 | 10 | 75 | 1 | 0.235 | 26.8 | 84.4 | 172.0 | 12.4 | 42.6 |

| 2 | 10 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.232 | 26.7 | 84.5 | 151.6 | 37.4 | 44.3 |

| 3 | 7.5 | 50 | 0.5 | 0.277 | 36.0 | 77.6 | 70.5 | 13.7 | 38.1 |

| 4 | 7.5 | 75 | 0.75 | 0.216 | 32.2 | 86.0 | 78.3 | 23.9 | 42.5 |

| 5 | 10 | 75 | 0.5 | 0.278 | 33.2 | 78.4 | 109.7 | 37.8 | 45.2 |

| 6 | 7.5 | 50 | 1 | 0.170 | 25.9 | 88.3 | 157.3 | 9.9 | 41.7 |

| 7 | 7.5 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.178 | 28.2 | 86.0 | 109.9 | 15.8 | 41.4 |

| 8 | 7.5 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.174 | 25.4 | 87.9 | 137.6 | 8.1 | 39.9 |

| 9 | 5 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.106 | 25.3 | 91.1 | 160.1 | 5.6 | 37.2 |

| 10 | 5 | 25 | 1 | 0.104 | 26.4 | 92.8 | 170.7 | 2.7 | 37.7 |

| 11 | 10 | 25 | 1 | 0.222 | 24.7 | 84.6 | 163.3 | 30.4 | 43.1 |

| 12 | 7.5 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.163 | 25.3 | 89.7 | 112.4 | 25.1 | 38.1 |

| 13 | 5 | 75 | 1 | 0.118 | 28.1 | 89.5 | 198.6 | 14.5 | 37.5 |

| 14 | 5 | 25 | 0.5 | 0.123 | 28.6 | 91.5 | 159.1 | 5.4 | 37.9 |

| 15 | 7.5 | 50 | 0.75 | 0.200 | 27.6 | 87.3 | 73.4 | 21.2 | 39.2 |

| 16 | 10 | 25 | 0.5 | 0.295 | 32.7 | 80.5 | 175.3 | 19.3 | 42.9 |

| 17 | 5 | 75 | 0.5 | 0.114 | 27.0 | 92.2 | 175.3 | 7.8 | 37.5 |

| 18 | 7.5 | 25 | 0.75 | 0.164 | 24.6 | 89.5 | 138.1 | 24.2 | 40.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).