1. Introduction

Silica aerogels are materials that, since their discovery in 1931 [

1,

2], have reached growing attention, and the forecast is a continuous increase in their production and scientific research [

3]. Their outstanding properties are a direct consequence of the structural features; particles and pores, that present nanometric size. Thus, silica aerogels show ultra-low densities in the range of 0.03 to 0.3 g/cm

3 [

4,

5] that, in comparison to the bulk density of solid silica (2.2 g/cm

3) [

6], are understandable by the presence of a huge porosity with values sometimes higher than 97 %. Combining high porosities with nanometric particles also gives rise to high specific surface areas that can reach values over 1200 g/m

2 [

7]. Therefore, these exceptional characteristics lead to unparalleled thermal insulation and optical transparency because of their similar refractive index to air and pores in the nanoscale [

8], which, combined with their lightweight, make them highly suitable for advanced glazing and energy-efficient windows [

9,

10]. Furthermore, their low dielectric constants and high specific surface areas open up innovative applications in electronic devices, adsorption and catalysis [

11,

12].

Nevertheless, thorough control of the porous structure and solid skeleton is needed to tailor the derived properties of aerogels. For this reason, different approaches have been followed in the literature. For instance, modifying the synthesis parameters such as silica precursors [

13], concentrations, solvents [

14], pH [

15], catalysts amount or nature [

16], or ageing time [

17] are frequent strategies for modulating the final structures of the silica aerogels [

18]. Moreover, other techniques such as mechanical reinforcement with fibers [

19], particles [

20], scaffolds [

21,

22,

23] or polymer crosslinking [

24,

25], or by physical modulation of the pore size through compression [

26,

27] are also alternatives to reach the desired properties in aerogels.

Despite these techniques allowing the control of the silica aerogel structures, it has been widely studied that the drying method employed for extracting the solvent used during the synthesis also presents a critical influence on the aerogel structures and, therefore, properties [

28]. In general terms, ambient pressure drying leads to aerogels with a higher density and reduced porosity as a result of strong shrinkages [

29]. These shrinkages are promoted by the capillary forces acting during evaporation of the solvent and condensation reactions of silanol groups, which result in irreversible shrinkages and pore collapse [

30,

31]. Nevertheless, the effect of these forces can be reduced by three methods: i) by exchanging the polar solvent with a low surface tension solvent (apolar); ii) by enhancing the mechanical stability of the gel through strengthening the solid network to a better force-withstand; or iii) by decreasing the presence of hydroxyl groups on the gel surface, that is, by increasing hydrophobicity, to reach the so-called springback effect (SBE) in which the gel undergoes a re-expansion after an initial shrinkage [

32]. This last effect is usually observed in samples with non-polar endgroups. Thus, it is common to perform a surface treatment with silylating agents such as trimethylchlorosilane (TMCS) or hexamethyldisilazane (HMDZ) for promoting hydrophobicity in the aerogel system and the subsequent shrinkage decrease during the drying procedure [

33,

34].

Furthermore, each drying method presents crucial parameters that also determine the microstructure control, as it is the drying temperature in ambient pressure drying, the working pressure and duration in the supercritical dryings [

35,

36], or the freezing rate on freeze-drying [

37]. Focusing on supercritical drying, the drying media also affects the surface properties of the obtained samples, since supercritical drying with hot alcohols usually leads to hydrophobic aerogels since their surface becomes covered by the corresponding alkyl groups through re-esterification, whereas supercritical carbon dioxide extraction provides hydrophilic aerogels [

38].

Thus, the chemical nature of the gel skeleton, governed by the surface functional groups, plays a significant role in the nanoporous structures that will determine the final properties. Owing to the complexity of the drying-textural properties influence, there is a need to understand how to select the proper drying method depending on the aerogel water-affinity to obtain the optimum properties regarding density, specific surface areas and porosity for the desired applications.

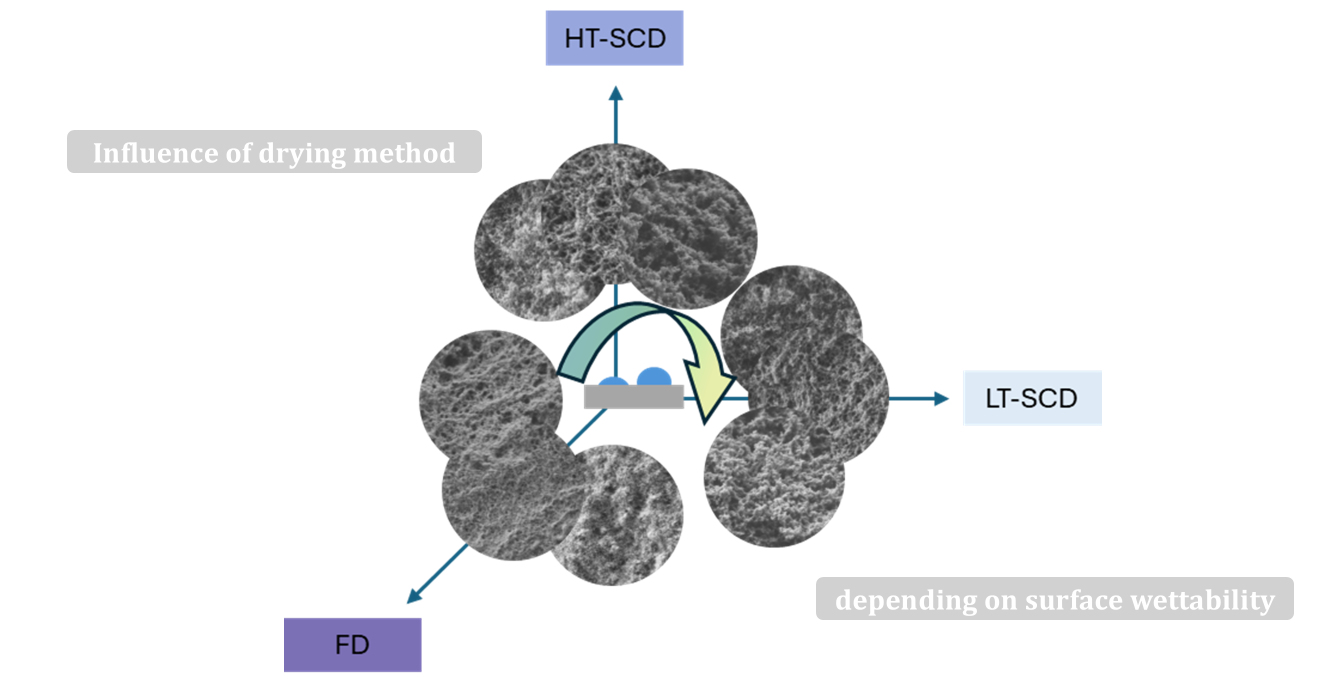

Therefore, in this work, authors selected silica aerogel systems covering different levels of hydrophobicity through modifications in the precursor concentrations (TEOS and MTMS) and dried the samples by three different procedures: freeze-drying, high-temperature supercritical drying (with alcohol), and low-temperature supercritical drying (with CO2). Then, the effect of each process on their structural/textural properties was studied in detail, providing an effective knowledge of the relationship between the water-affinity properties and the influence of each drying method on their porous structures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The silica precursors were TEOS (tetraethyl orthosilicate; Si(OC2H5)4; Acros Organics), and MTMS (trimethoxymethylsilane; CH3Si(OCH3)3; Aldrich). The acid catalyst for the sol-gel chemistry was oxalic acid (C2H2O4; 99%; Fluka Analytical) as a 0.01 M aqueous solution, and the basic catalyst was ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH, 25% NH3 in H2O, Fluka Analytical) as a 2.5 M aqueous solution. Ethanol (EtOH, absolute, C2H5OH), employed as solvent, was supplied by Fluka Analytical. All reagents were used without further purification steps.

2.2. Synthesis of the Silica Aerogels

The corresponding amount of the silica precursor (TEOS; MTMS) was diluted in ethanol (10 mL of solution for each sample). Then, the two-step sol-gel process was initiated by adding the acidic catalyst (oxalic acid 0.01 M) and the mixture was stirred at 27 °C and 300 rpm for 30 min. Then, the sealed solution was placed in an oven for complete hydrolysis at 27 °C for 24 h. After this step, the basic catalyst was quickly dropped into the mixture and stirred at 300 rpm for 15 seconds. Once a permanent gel was obtained, i.e. with no flowing when tilting the container, gel time was taken, and the gels were placed in an oven at 27 °C for 5 days for ageing. Finally, gels were dried by the different methods explained in the following section.

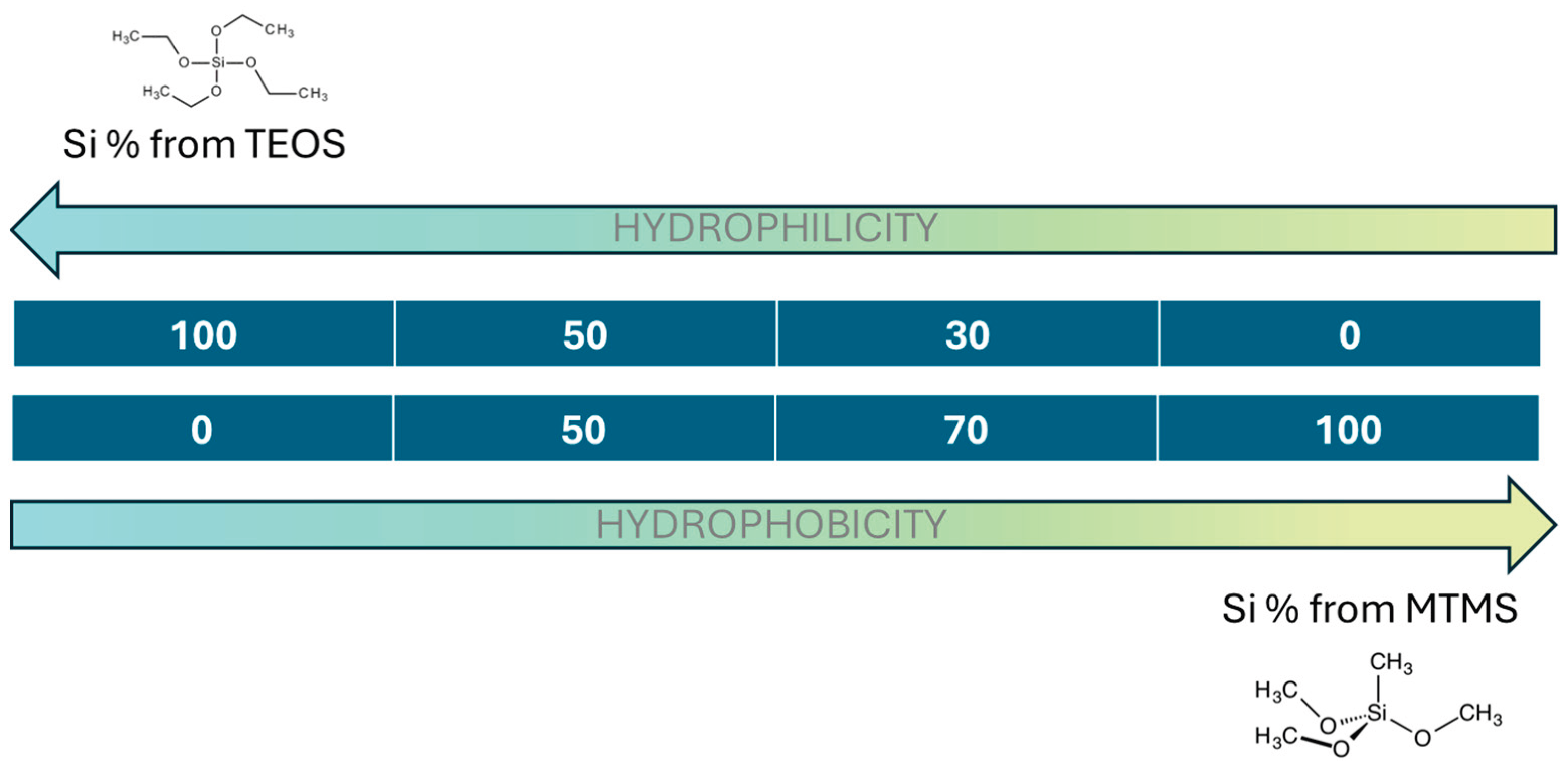

Four different formulations were developed by modifying the amounts of both precursors (TEOS and MTMS). The molar ratio of Si in the network was kept as 100%-TEOS (sample labelled as 100T), 50%TEOS-50%MTMS (labelled as 50T-50M), 30%TEOS-70%MTMS (labelled as 30T-70M) and 100% MTMS (labelled as 100M) as described in

Figure 1. Two replicates were produced for each formulation and drying method.

2.3. Drying Methods

The drying conditions for the low-temperature supercritical drying (LT-SCD) with carbon dioxide were 140 bar and 50 °C, with a previous washing of unreacted species by ethanol at RT. When gels were dried by high-temperature supercritical drying (HT-SCD) ethanol was employed as fluid and the drying conditions were 80 bar and 260 °C. Freeze-drying was also employed as drying technique at 19 Pa and -82 °C with a freeze dryer model FDL-LON-80-TD-MM. Prior to this drying, samples were submitted to a solvent-exchange process by replacing the ethanol from pores with distilled water (4x12 h, RT).

2.4. Characterization Methods

2.4.1. Bulk Density, Solid Density and Porosity

Bulk density was obtained as the ratio between mass and geometrical volume as described in ASTM D1622/ D1622M-14 [

39]. The solid density of the silica aerogels was determined by helium pycnometry with an AccuPyc II 1340, Micromeritics at 19.5 psi. Porosity was calculated by equation 1:

where

ρr is the relative density obtained as the ratio between the bulk density and solid density.

2.4.2. Contact Angle

The sessile drop method was employed to determine the hydrophobicity degree by suspending a 15 µL droplet of ultra-pure water on the sample surface [

40]. The contact angle measurements were carried out by IMAGE/J software from the photographs taken.

2.4.3. Specific Surface Area (SBET) and Pore Size

The specific surface area (

SBET) was measured by nitrogen sorption with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 instrument in the University of Málaga (Spain). Samples were first degassed under vacuum at 25 °C for 24 h and then experiments were carried out at 77 K in the range

P/

P0 = 0.05 – 0.30. The specific surface area was obtained by the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method [

41].

From this value, the mean pore size was calculated using equation 2:

where

Vp is the total pore volume, which was determined as the gaseous volume per unit of mass by subtracting the skeleton volume (1/

ρs) from the total volume (1/

ρB) of the monolith. as described by equation 3:

2.4.4. Morphology Observation by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The nanoporous structure of silica aerogels was assessed using a field-emission scanning electron microscope, FESEM (Compact/VP Compact FESEM, from Zeiss Merlin). Before the visualization, samples were gold-sputtered for suitable electrical conductivity.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Silica Aerogel Samples and Correspondent Hydrophobicity

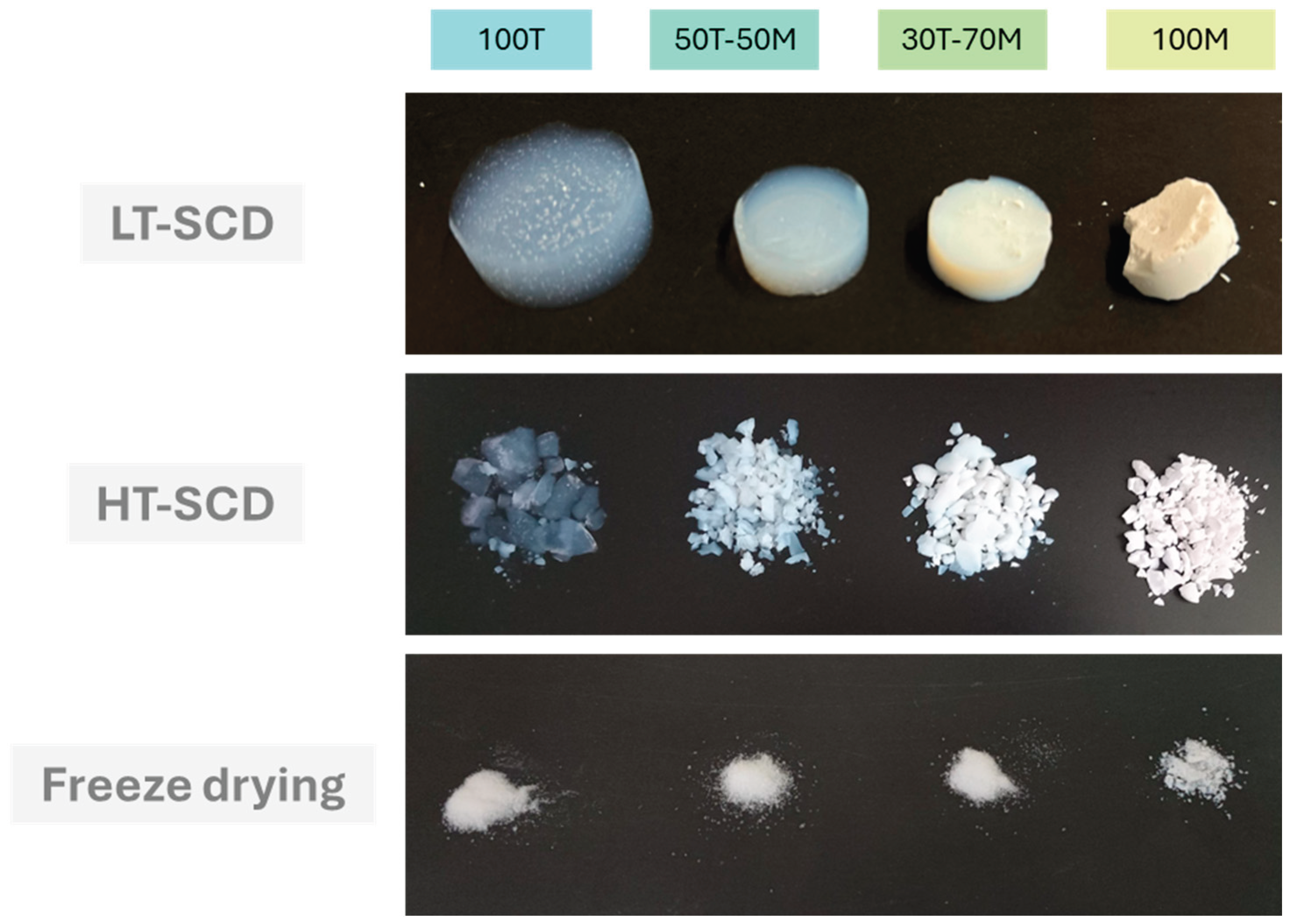

The four different gel formulations were dried by the three methods described in section 2.3. giving rise to 12 different silica aerogel samples, as can be seen in

Figure 2. At first glance, differences in the appearance of all the aerogels can be observed. The aerogels dried by LT-SCD preserve their original shape as a result of the appeased capillary forces present during the ethanol extraction by supercritical CO

2 (scCO

2). On the other hand, gels dried by HT-SCD were broken into small pieces, and the aerogels that were dried by freeze-drying were collected in powder form as a consequence of the mechanical stress caused by the increase of the specific volume of water in the pores during freezing.

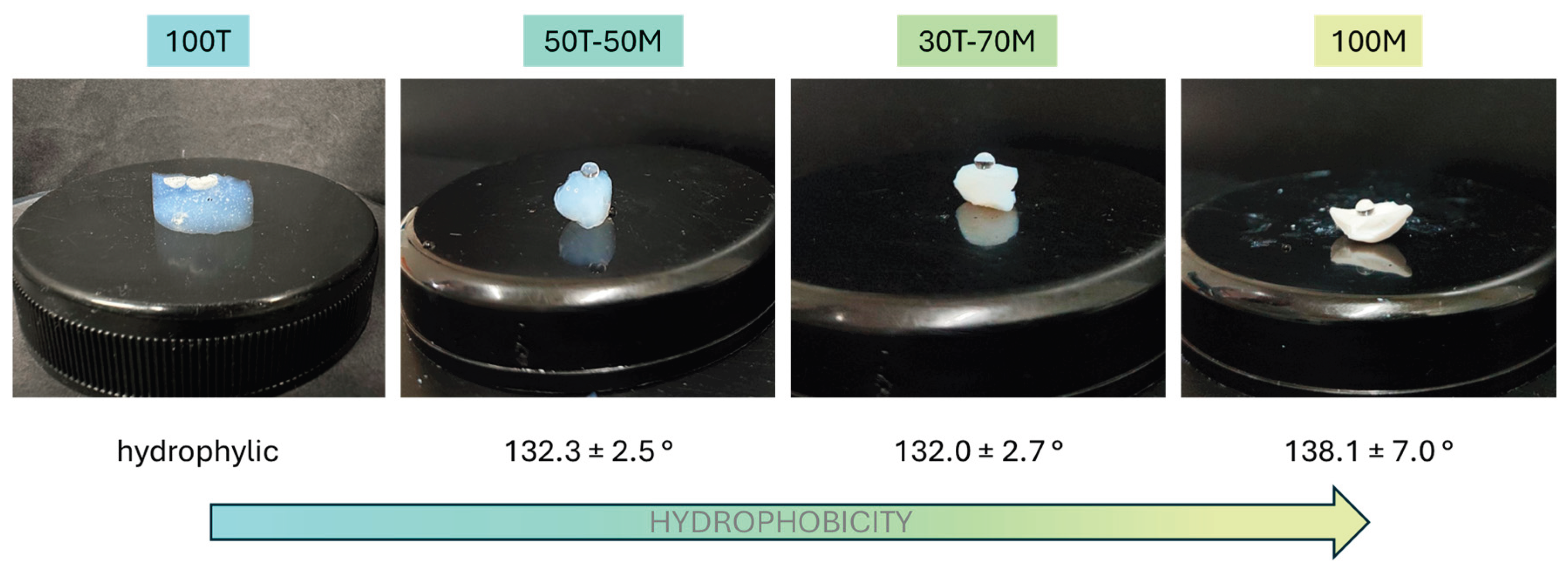

In order to understand the influence of the drying methods on each formulation, the hydrophilic properties of the produced samples (those dried by LT-SCD) must be measured since a strong correlation between the water affinity and drying principle is expected (no re-esterification). In

Figure 3 it can be seen that the 100T sample presents a hydrophilic nature, whereas the contact angles for the rest of aerogels vary between 132 and 138° (being all considered as hydrophobic materials according to the IUPAC classification) showing a direct trend with the silica precursors type; 100T presents the most hydrophilic behavior because of the hydroxyl groups present on its surface, whereas when including a 50% or 70% mol. of Si from MTMS precursor, methyl groups are present in the structure significantly increasing the hydrophobic behavior, but with no remarkable differences between the latter. And, finally, the most hydrophobic sample was produced with 100% of MTMS.

3.2. Effect of Drying on Density and Porosity

All the samples were characterized in terms of density, porosity, specific surface area and mean pore size. The results obtained are gathered in

Table 1. The skeletal densities obtained by helium pycnometry and used for the calculations were: 1.645 g/cm

3 for 100T, 1.353 g/cm

3 for 50T-50M, 1.409 g/cm

3 for 30T-30M, and 1.315 g/cm

3 for 100M.

The values obtained for bulk density and porosity are plotted in

Figure 4 for an enhanced visualization. There exists a clear influence of the drying method on the sample density and, therefore, porosity. In general, the freeze-drying method provides the highest densities (and lowest porosities) as a result of a strong shrinkage associated to the presence of ice microcrystals [

42]. This occurs for all the aerogels except the most hydrophobic ones, 100M sample, which presents a similar density to that obtained by LT-SCD. This can be explained by the higher hydrophobic surface of that sample, which reduces the interaction with water during the freezing and lyophilization processes and may induce a structure less damaged by the ice crystals. Thus, freeze-drying leads to more similar results in density and porosity than those obtained by SCD for samples with a more hydrophobic surface. The porosities reached by freeze-drying for these samples are comprised between 70.6 and 82.1 % (see

Figure 4b). However, when inducing a higher hydrophilicity in the silica aerogels, the differences between this method and supercritical drying are more remarkable.

On the other hand, when comparing between supercritical methods it can be stated that the HT-SCD method leads to lower densities than LT-SCD for higher TEOS contents, probably due to the re-esterification phenomenon that produces hydrophobic pore surfaces [

43]. The density of the 100MTMS sample is significantly higher when being dried by HT-SCD. That is, for hydrophilic samples, HT SCD leads to nanoporous structures with high porosities, whereas when aerogels are more hydrophobic (100 MTMS), the low-temperature process with sc-CO

2 is a more effective drying technique in preserving the gel structure.

3.3. Effect of Drying on the Textural Properties and Porous Structures

Once the influence of the drying procedure on density and porosity was explored, the effect of the drying methods on the nanoporous structures and textural properties should be studied. The scanning electron micrographs are gathered in

Figure 5. As consequence of the clear densification of the particulate skeleton when drying the aerogels by freeze-drying, especially for 30T-70M, 50T-50M and 100T, pore size is reduced for these samples, as it is observed in

Figure 6a. In fact, the percentage reduction in pore size when drying by freeze-drying in comparison to HT and LT SCD follows a clear trend; less hydrophobic samples present higher pore reduction because of the higher surface energy; for instance, for 100T aerogel these reductions are of ca. 80% with respect to both SCD techniques. Nevertheless, these differences are progressively appeased when inducing hydrophobicity until reaching similar pore size values for 100M in comparison to the LT-SCD.

When comparing between freeze-dried samples, aerogels produced with MTMS present a more random and less linked network due to the presence of methyl groups not available for linking, thus, larger pores were expected [

44,

45]. However, it should be noted that, for having all samples with the same synthesis conditions, the procedure to obtain MTMS gels is not optimal [

35], which may have originated higher density gels. Furthermore, there are some synergistic effects related to the hydrophobicity of MTMS structure. On the one hand, the reduced -OH groups present in 100MTMS decrease the interaction between the silica matrix and the ice crystals, therefore minimizing the subsequent shrinkage that happens during sublimation. On the other hand, the inherent flexibility of the MTMS matrix allows for better shrinkage withstanding. Both effects lead to a minimized pore reduction, which is in agreement with the observed trend in

Figure 6a-freeze drying. Moreover, when observing the 100M sample by SEM, it is obvious that it has a more fibrous-like structure than the colloidal-like gels of the other images. This effect may be due to some coarsening of the structural units caused by water aging and/or compression by the ice crystals.

Aerogels dried by LT-SCD and HT-SCD follow a similar trend between them, reaching the largest pores for the most hydrophilic sample (100T). This, even being contrary to what was expected for the chemical nature of the silica network with a high crosslinking through the -OH groups, also agrees with the density values, since a remarkably lower shrinkage was observed for this sample, leading to the presence of larger pores and overall porosity.

Considering the changes observed in the pore size as a consequence of the drying method and hydrophobicity of the silica matrix, the specific surface area of these materials is expected to show also significative modifications. As depicted in

Figure 6b, the formulations containing both precursors (30T-70M and 50T-50M), which present an intermediate wettability, show the higher surface areas with values above 1000 m

2/g when being dried by SCD methods. Nevertheless, these values are slightly reduced when applying freeze-drying.

Despite freeze-drying being concluded to induce high densities in hydrophilic samples (100T), its effect is not remarkable on the specific surface area as a result of the balance between the densification and the pore size reduction. The specific surface area reached for the 100MTMS sample was the same for the three different drying methods, evidencing the influence of the hydrophobic surface.

The obtained results demonstrated that, according to the existence of polar (hydroxyl) or non-polar (methyl) groups on the gels surface, there exists a different surface energy distribution that depends on the drying method [

36]. In the case of freeze-drying (see

Figure 7, bottom), the interaction between water and the polar groups of the silica gel promotes a structural densification, leading to densities from 0.235 to 0.398 g/cm

3. This contributes to reducing porosity with values between 70 and 82 %, as well as inducing pore collapse, reaching the smallest pores (from 7.7 to 29.1 nm). Nevertheless, the effect in the specific surface area is not strongly remarkable, ranging from 479 to 922 m

2/g.

However, for samples dried by SCD (LT and HT) (

Figure 7 upper), it can be observed how the densities reached are lower (normally below 300 g/cm

3), thus showing higher porosities (reaching a maximum of 95 %), especially for those samples presenting a more hydrophilic behavior. Furthermore, despite pores are slightly larger than those obtained by freeze-drying, the specific surface areas are higher, achieving values as high as ca. 1150 m

2/g.

It should be taken into account that the most hydrophobic sample (100MTMS) reaches lower densities when being dried by LT-SCD with a value of 0.215 (g/cm3) than with HT-SCD (0.423 g/cm3), which could be explained by a possible further condensation and cluster formation happening at high temperatures.

4. Conclusions

The synthesis of silica gels with different hydrophobicity degrees has been achieved by modifications in the precursor concentrations (TEOS and MTMS). Then, the effect of the drying method on the final textural properties and morphology (density, porosity, specific surface area and pore size) was studied by following three procedures: freeze-drying, high-temperature supercritical drying with ethanol, and low-temperature supercritical drying with carbon dioxide.

The results reveal that hydrophobicity plays a key role in minimizing structural damage during drying, particularly under freeze-drying conditions, where more hydrophobic samples exhibited reduced shrinkage and better structural preservation. In contrast, HT-SCD led to increased densification in highly hydrophobic gels, likely due to further condensation reactions occurring at elevated temperatures. LT-SCD proved to be the most effective drying method for preserving pore structure in hydrophobic samples, leading to low-density, high-porosity aerogels.

Overall, this work provides critical insights into how the interplay between surface wettability and drying conditions can be leveraged to tailor the properties of silica aerogels, enabling optimized design for targeted applications in thermal insulation, adsorption, or catalysis. The findings also emphasize the importance of considering both the chemical nature of the silica matrix and the thermal conditions of the drying process to achieve aerogels with desirable performance.

Funding

Funded by the European Union, under the Grant Agreement GA101081963 attributed to the project H2OforAll - Innovative Integrated Tools and Technologies to Protect and Treat Drinking Water from Disinfection Byproducts (DBPs). Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. CERES research unit was supported by national funds from FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., and when appropriate co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), under the scope of projects 10.54499/UIDB/00102/2020 and 10.54499/UIDP/00102/2020. Financial assistance from Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MCIU) (Spain) (PID2021-127108OB-I00, TED2021-130965B-I00, and PDC2022-133391-I00), Regional Government of Castilla y León and the EU-FEDER program (CLU-2019-04) are gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by the Regional Government of Castilla y León (Junta de Castilla y León), and by the Ministry of Science and Innovation MICIN and the European Union NextGenerationEU / PRTR. (C17. I1). This research is also part of the JDC2023-051979-I (Beatriz Merillas), financed by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the FSE+. Cláudio M. R. Almeida and Maria Inês Roque acknowledge the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. (FCT, Portugal) for their PhD grants SFRH/BD/150790/2020 and 2024.03908.BDANA, respectively, funded by national funds from MCTES (Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior) and, when appropriate, co-funded by the European Commission through the European Social Fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank María Dolores Marqués Gutiérrez, from the Porous Solids Laboratory of the University of Malaga.

References

- S.S. Kistler: Coherent Expanded Aerogels and Jellies, Nature. 127 (1931) 741.

- S.S. Kistler, Coherent expanded aerogels, J. Phys. Chem. 36 (1932) 52–64. [CrossRef]

- Aerogel Market Size & Share Report, 2020-2028, (2021). https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/aerogel-market.

- L.W. Hrubesh, T.M. Tillotson, J.F. Poco, Characterization of ultralow-density silica aerogels made from a condensed silica precursor, 1990.

- M.A. Aegerter, N. Leventis, M.M. Koebel, Aerogels Handbook, Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2011.

- T. Woignier, J. Phalippou, Skeletal density of silica aerogels, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 93 (1987) 17–21.

- J. Ren, J. Feng, L. Wang, G. Chen, Z. Zhou, Q. Li, High specific surface area hybrid silica aerogel containing POSS, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 310 (2021) 110456. [CrossRef]

- A. Buzykaev, A. Danilyuk, S. Ganzhur, T. Gorodetskaya, E. Kravchenko, A. Onuchin, A. Vorobiov, Aerogels with high optical parameters for Cherenkov counters, Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers, Detect. Assoc. Equip. 379 (1996) 465–467. [CrossRef]

- S.B. Riffat, G. Qiu, A review of state-of-the-art aerogel applications in buildings, Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 8 (2013) 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, J. lei Niu, Application of super-insulating translucent silica aerogel glazing system on commercial building envelope of humid subtropical climates - Impact on space cooling load, Energy. 83 (2015) 316–325. [CrossRef]

- Y.J. Kim, S.H. Yoo, H.G. Lee, Y. Won, J. Choi, K. Kang, Structural Analysis of silica aerogels for the interlayer dielectric in semiconductor devices, Ceram. Int. 47 (2021) 29722–29729. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Dunn, P. Cole, D. Covington, M.C. Webster, R.J. Pugmire, R.D. Ernst, E.M. Eyring, N. Shah, G.P. Huffman, Silica aerogel supported catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, Appl. Catal. A Gen. 278 (2005) 233–238. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, H. Ren, J. Zhu, Y. Bi, Y. Xu, L. Zhang, Facile fabrication of superhydrophobic, mechanically strong multifunctional silica-based aerogels at benign temperature, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 473 (2017) 59–63. [CrossRef]

- P.B. Sarawade, J.-K. Kim, J.-K. Park, H.-K. Kim, Influence of Solvent Exchange on the Physical Properties of Sodium Silicate Based Aerogel Prepared at Ambient Pressure, Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 6 (2006) 93–105. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee, Y.C. Cha, H.J. Hwang, J.W. Moon, I.S. Han, The effect of pH on the physicochemical properties of silica aerogels prepared by an ambient pressure drying method, Mater. Lett. 61 (2007) 3130–3133. [CrossRef]

- K. Nawaz, S.J. Schmidt, A.M. Jacobi, Effect of catalyst used in the sol-gel process on the microstructure and adsorption/desorption performance of silica aerogels, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 74 (2014) 25–34. [CrossRef]

- S. Smitha, P. Shajesh, P.R. Aravind, S.R. Kumar, P.K. Pillai, K.G.K. Warrier, Effect of aging time and concentration of aging solution on the porosity characteristics of subcritically dried silica aerogels, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 91 (2006) 286–292. [CrossRef]

- B. Babiarczuk, D. Lewandowski, K. Kierzek, J. Detyna, W. Jones, J. Kaleta, J. Krzak, Mechanical properties of silica aerogels controlled by synthesis parameters, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 606 (2023) 122171. [CrossRef]

- T. Linhares, V.H. Carneiro, B. Merillas, M.T. Pessoa De Amorim, L. Durães, Textile waste-reinforced cotton-silica aerogel composites for moisture regulation and thermal / acoustic barrier, J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 102 (2022) 574–588. [CrossRef]

- X. Hou, R. Zhang, D. Fang, An ultralight silica-modified ZrO2–SiO2 aerogel composite with ultra-low thermal conductivity and enhanced mechanical strength, Scr. Mater. 143 (2018) 113–116. [CrossRef]

- B. Merillas, A. Lamy-Mendes, F. Villafañe, L. Durães, M.Á. Rodríguez-Pérez, Silica-Based Aerogel Composites Reinforced with Reticulated Polyurethane Foams: Thermal and Mechanical Properties, Gels. 8 (2022) 392. [CrossRef]

- B. Merillas, A. Lamy-Mendes, F. Villafañe, L. Durães, M.Á. Rodríguez-Pérez, Polyurethane foam scaffold for silica aerogels : effect of cell size on the mechanical properties and thermal insulation, Mater. Today Chem. 26 (2022) 101257. [CrossRef]

- X. Ye, Z. Chen, S. Ai, B. Hou, J. Zhang, Q. Zhou, F. Wang, H. Liu, S. Cui, Microstructure characterization and thermal performance of reticulated SiC skeleton reinforced silica aerogel composites, Compos. Part B. 177 (2019) 107409. [CrossRef]

- H. Maleki, L. Durães, A. Portugal, An overview on silica aerogels synthesis and different mechanical reinforcing strategies, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 385 (2014) 55–74. [CrossRef]

- J.P. Randall, M.A.B. Meador, S.C. Jana, Tailoring mechanical properties of aerogels for aerospace applications, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 3 (2011) 613–626. [CrossRef]

- B. Merillas, C.A. García-González, T.E.G. Álvarez-Arenas, M.Á. Rodríguez-Pérez, Towards the Optimization of Polyurethane Aerogel Properties by Densification: Exploring the Structure–Properties Relationship, Small Struct. 2400120 (2024) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- S.F. Plappert, J.M. Nedelec, H. Rennhofer, H.C. Lichtenegger, F.W. Liebner, Strain Hardening and Pore Size Harmonization by Uniaxial Densification: A Facile Approach toward Superinsulating Aerogels from Nematic Nanofibrillated 2,3-Dicarboxyl Cellulose, Chem. Mater. 29 (2017) 6630–6641. [CrossRef]

- G.W. Scherer, Effect of drying on properties of silica gel, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 215 (1997) 155–168. [CrossRef]

- D. Panda, A.K. Sahu, K.M. Gangawane, Effect of molar concentration and drying methodologies on monodispersed silica sol for synthesis of silica aerogels with temperature-resistant characteristics, Mater. Sci. Eng. B. 299 (2024) 117062. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Jones, J. Sakamoto, Aerogels Handbook, in: Aerogels Handb., 2011: pp. 721–746. [CrossRef]

- A. Bisson, A. Rigacci, D. Lecomte, E. Rodier, P. Achard, Drying of Silica Gels to Obtain Aerogels: Phenomenology and Basic Techniques, Dry. Technol. 21 (2003) 593–628. [CrossRef]

- F. Zemke, E. Scoppola, U. Simon, M.F. Bekheet, W. Wagermaier, A. Gurlo, Springback effect and structural features during the drying of silica aerogels tracked by in-situ synchrotron X-ray scattering, Sci. Rep. 12 (2022) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- S. Nagapriya, M.R. Ajith, H. Sreemoolanadhan, M. Mathew, S.C. Sharma, Hydrophobic silica aerogels by ambient pressure drying, Mater. Sci. Forum. 830–831 (2015) 476–479. [CrossRef]

- P.M. Shewale, A.V. Rao, A.P. Rao, Effect of different trimethyl silylating agents on the hydrophobic and physical properties of silica aerogels, Appl. Surf. Sci. 254 (2008) 6902–6907. [CrossRef]

- L. Duräes, M. Ochoa, N. Rocha, R. Patrício, N. Duarte, V. Redondo, A. Portugal, Effect of the drying conditions on the microstructure of silica based xerogels and aerogels, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 12 (2012) 6828–6834. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ru, L. Guoqiang, L. Min, Analysis of the effect of drying conditions on the structural and surface heterogeneity of silica aerogels and xerogel by using cryogenic nitrogen adsorption characterization, Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 129 (2010) 1–10. [CrossRef]

- C. Simón-Herrero, S. Caminero-Huertas, A. Romero, J.L. Valverde, L. Sánchez-Silva, Effects of freeze-drying conditions on aerogel properties, J. Mater. Sci. 51 (2016) 8977–8985. [CrossRef]

- K. Tajiri, K. Igarashi, T. Nishio, Effects of supercritical drying media on structure and properties of silica aerogel, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 186 (1995) 83–87. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1622-08: Standard Test Method for Apparent Density of Rigid Cellular Plastics, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Corona-Treated Polymer Films Using Water Contact Angle Measurements - ASTM D5946-17, 2017.

- E.P. Barrett, L.G. Joyner, P.P. Halenda, The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73 (1951) 373–380. [CrossRef]

- S. V Kalinin, L.I. Kheifets, A.I. Mamchik, A.G.K. Ko, A.A. Vertegel, Influence of the Drying Technique on the Structure of Silica Gels, 35 (1999) 31–35.

- A. Soleimani Dorcheh, M.H. Abbasi, Silica aerogel; synthesis, properties and characterization, J. Mater. Process. Technol. 199 (2008) 10–26. [CrossRef]

- Y. Duan, L. Wang, S. Li, X. Liu, J. Liang, J. Liu, X. Duan, H. Liu, Modulating pore microstructure of silica aerogels dried at ambient pressure by adding N-hexane to the solvent, J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 610 (2023) 122312. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, C. Li, Y. Wang, L. Lin, K.K. Ostrikov, High-Performance Methylsilsesquioxane Aerogels : Hydrolysis, (2023) 1–20.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).