1. Introduction

The project subtitle

Into the Blue encompasses multiple concepts central to the project goals. Firstly,

Into the Blue refers to “going into the unknown”, a highly relevant concept given the uncertain future of our Arctic. The Arctic is warming almost four times as fast as the rest of the planet. As a result, the Greenland Ice Sheet has been melting for 27 years in a row, and now accounts for 25% of global sea level rise [

1]. Despite global efforts to keep climate warming below 2˚C, almost every emission scenario leads at least temporarily to a warmer than modern global and Arctic climate; a climate that is unknown to humans and in fact unknown on Earth over the last 100,000 years. We also use

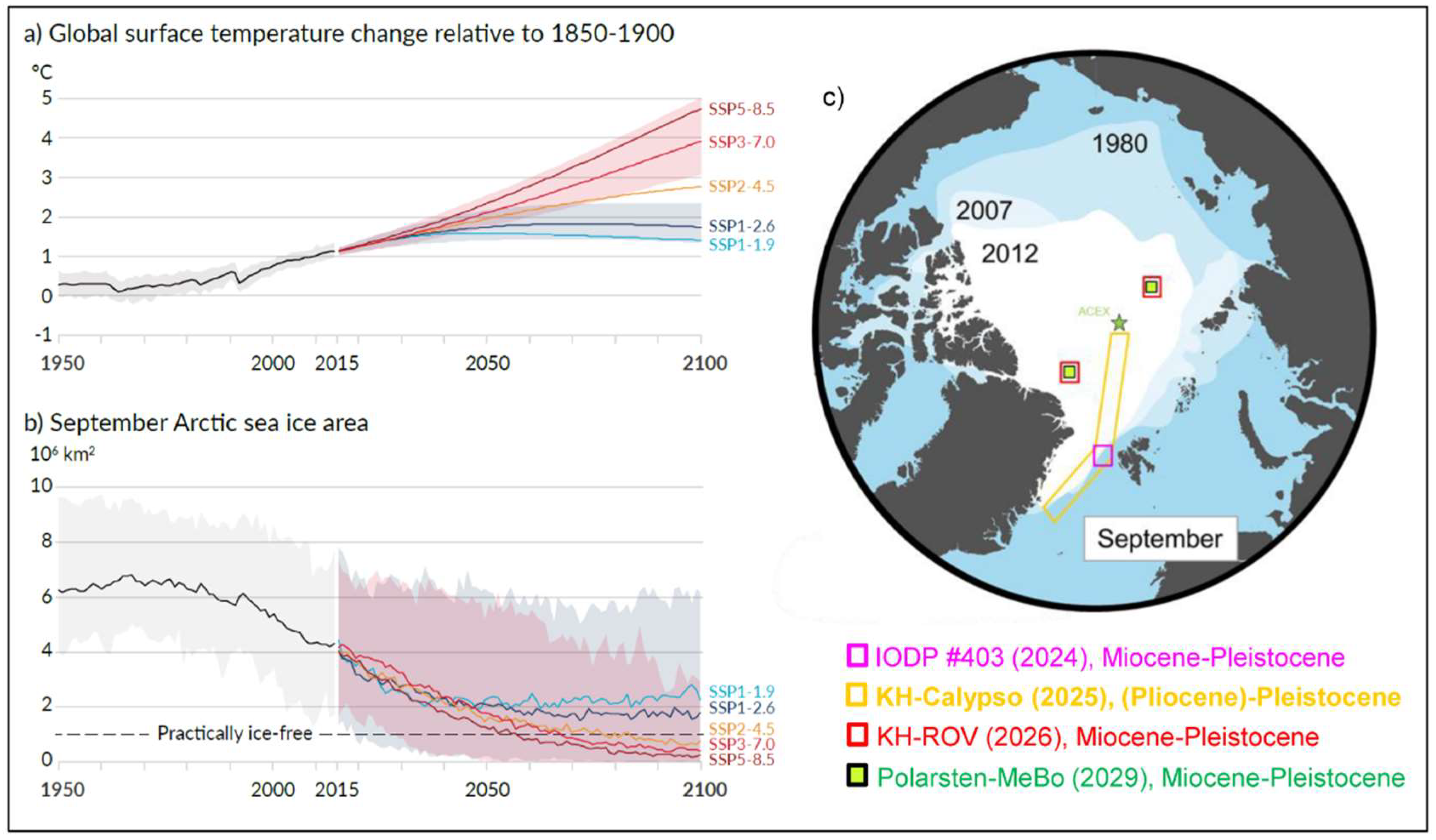

Into the Blue to describe ongoing changes in the Arctic Ocean. Projections indicate that the Arctic Ocean will become sea ice free during summers by the mid-century, even under medium greenhouse gas emissions [

2,

3] (

Figure 1a,b). The Arctic Ocean is transitioning from white to blue, with a host of associated ecosystem changes. We know that major changes are already happening in the Arctic climate, ecosystems and beyond, yet the consequences for our planet and society remain incompletely understood and poorly constrained [

4].

A key challenge for humanity is to document and understand how a blue Arctic will both respond to and drive an increasingly warmer future climate. This “Arctic challenge” of global significance can only be addressed by elucidating the

modus operandi of time intervals that were warmer than present (“greenhouse conditions”) in our planet’s history. We cannot currently do this because we lack (1) Arctic records of past warm climate in our planet’s history and (2) climate models adapted to include all components of the climate system (i.e., cryosphere feedbacks) at appropriate resolution [

2].

Over Earth’s youngest geological history, we have periods like the Last Interglacial (~125,000 years ago), the mid Pliocene warm period (mPWP; ~3 million years ago), and the mid Miocene Climate Optimum (~17 million years ago) when the climate was warmer than today. These periods with a globally warmer than present climate hold information about how the ocean and cryosphere looked like and operated, however, we still lack the key geological archives covering these time periods from the Arctic that can reveal the mechanisms responsible for Arctic change and its amplification under greenhouse climate states.

To date, only one deep-time Arctic greenhouse record is available - but this is incomplete (ACEX,

Figure 1c) [

5,

6,

7].

The most recent iteration of climate models involved in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) tends to underestimate the observed Arctic amplification [

8,

9]. Furthermore, there are considerable uncertainties regarding the projected sea ice decline and the Arctic amplification, compounded by the relatively coarse spatial resolution of these models, mostly at 1° [

10]. Solving this “

Arctic Challenge” requires in-depth knowledge beyond state-of-the-art from both empirical and numerical experts on how the cryosphere evolved under past warm climate conditions. Our ERC Synergy Grant project

Into the Blue represents a concerted research effort to fill this knowledge gap, aiming to document, understand and assess the impact of Arctic warming under a range of climate forcings and feedback mechanisms.

Paleoclimate dynamics provide context for present and future changes, quantify natural variability, and offer insights into mechanisms under different forcings. A crucial approach involves comparing model outputs with data reconstructions and observations, utilizing methods such as out-of-sample evaluation and emergent constraints [

11,

12]. To adequately tackle the range of possible climates, quantitative data on the magnitude and pace of natural fluctuations in the ocean, across landmasses, and within the cryosphere are essential. New Arctic climate records obtained within

Into the Blue will facilitate the unique testing of two Earth system (NorESM and AWI-ESM) and ice sheet models (UiT ISM, PISM, CISM) out of the range of present-day climate [

13,

14].

A new generation of storm-and-eddy resolving ESMs, already being developed under the EU’s Horizon 2020 nextGEMS project (2021-2025) (

https://nextgems-h2020.eu/, accessed on March 1, 2025), will be validated with new climate records for selected warmer-than-present states. The AWI-ESM is presently capable of running global coupled simulations in a multi-scale approach in the ocean and sea ice with state-of-the-art supercomputers [

15,

16], defining a new step in creating value for society.

Figure 1.

The “Arctic Challenge” (a) Global surface temperature change relative to 1850-1900 under five greenhouse gas (GHG) scenarios [

2], (b,c) Arctic Ocean with summer (September) sea ice evolution and only one past greenhouse record (Eocene) available (International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) “ACEX – Arctic Coring Expedition”). Illustrated in

Figure 1c is also new material for

Into the Blue to be recovered during scheduled expeditions. IODP #403 = International Ocean Discovery Expedition 403 in 2024 [

17]. KH = RV “Kronprins Haakon”, ROV = Remotely Operating Vehicle, Polarstern-MeBo = RV “Polarstern” with MARUM-MeBo remotely operational seafloor drilling system.

Figure 1.

The “Arctic Challenge” (a) Global surface temperature change relative to 1850-1900 under five greenhouse gas (GHG) scenarios [

2], (b,c) Arctic Ocean with summer (September) sea ice evolution and only one past greenhouse record (Eocene) available (International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) “ACEX – Arctic Coring Expedition”). Illustrated in

Figure 1c is also new material for

Into the Blue to be recovered during scheduled expeditions. IODP #403 = International Ocean Discovery Expedition 403 in 2024 [

17]. KH = RV “Kronprins Haakon”, ROV = Remotely Operating Vehicle, Polarstern-MeBo = RV “Polarstern” with MARUM-MeBo remotely operational seafloor drilling system.

2. Research Questions and Objectives

Into the Blue opens new horizons in Arctic climate science via the first concerted effort to address the “Arctic Challenge”. The central research question in our project will address is “Why and what were the global ramifications of a “blue” Arctic during past warmer-than-present-climates?”, with the primary hypothesis that the Arctic represents a critical planetary modulator that will immanently become ice-free: a key climate system transition beyond which unprecedented amplification of global warming can occur.

Specifically, Into the Blue aims to answer the following scientific questions:

- a.

How does the Arctic cryosphere change in warm climates?

- b.

What drives Arctic cryosphere change?

- c.

What are the impacts of cryosphere change in a warm Arctic?

Into the Blue will address these questions by retrieving and analysing new, ground-breaking Arctic climate records (

Figure 1c) from different key greenhouse states of the last ~17 Ma, and combining these with a cutting-edge Earth System and Ice Sheet Model (ESM/ISM) modelling framework through three inter-connected, cross-disciplinary scientific objectives, where we aim to

- a.

quantify Arctic cryosphere (sea ice, land ice) change during different past warm climate intervals, with different atmospheric carbon dioxide (pCO2) levels and boundary conditions, via the collection and analysis of novel Arctic geological archives

- b.

understand the dynamics of a warm Arctic cryosphere and ocean through new simulations using the latest ESMs/ISM

- c.

determine the impact of cryosphere change in a warm Arctic on ocean biosphere, climate extremes the society by integrating novel empirical data and ESM/ISM modelling outputs.

By addressing the “Arctic Challenge” we aim to (1) provide vital insights and understanding on how the Arctic and Earth’s climate transitions to a high pCO2 world; (2) inform about the impacts of a blue Arctic on ocean ecosystem, climate extremes and global consequences; (3) deliver key Arctic knowledge for improved future climate projections. These principal questions and objectives appertain to just how complex and challenging past Arctic greenhouse climate reconstructions and simulations are, and why the scientific rewards are so outstanding once all obstacles are solved.

3. Current State of Scientific Knowledge

There is overall agreement that the Arctic Ocean and adjacent area have undergone rapid and drastic environmental changes on recent, historical and geological time scales [

7,

18,

19,

20]. The most dramatic changes observed in the recent past are the unprecedented reduction in both summer and winter sea ice extent [

21] (

Figure 1b,c) and enhanced loss of the Greenland Ice Sheet, which now accounts for over 25% of observed global sea level rise [

1]. Northern Hemisphere warming is indicated by coupled ice-ocean models as the main driver of these cryosphere changes [

2,

22], however there is disagreement across different empirical datasets about the influence of atmospheric warming

versus oceanic heat transport on sea ice decline and glacial mass loss [

2,

18,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In-situ observations in the northern Barents Sea [

25,

27] suggest that enhanced oceanic heat transport by the North Atlantic Current (NAC) can cause weakened stratification, increased vertical mixing, and reduced sea ice in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic, collectively termed “Atlantification” [

27,

28,

29,

30]. Proxy reconstructions of heat and volume transport indicate also “Atlantification” in the Arctic Ocean during the Last Interglacial and the mPWP [

28,

29]. Warming of the subpolar North Atlantic has further increased ocean temperatures in the proximity of marine-terminating Greenland outlet glaciers [

31,

32], yet the processes connecting enhanced ocean heat transport to grounding line thinning and glacial retreat remain poorly understood [

33,

34,

35]. In contrast, variations in large-scale atmospheric circulation are a key driver of changes in surface mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet [

36,

37], which is now estimated to account for nearly 70% of total mass loss [

38]. Moreover, models indicate that enhanced atmospheric polar energy transport is accompanied by weaker ocean heat transport in future CO

2 scenarios [

24]. With new Arctic geological records combined with cutting-edge Earth System and Ice Sheet Model (ESM/ISM) modelling framework,

Into the Blue offers a new chance to understand the sensitivity of Arctic warming to a range of forcings and feedbacks during times warmer-than-present.

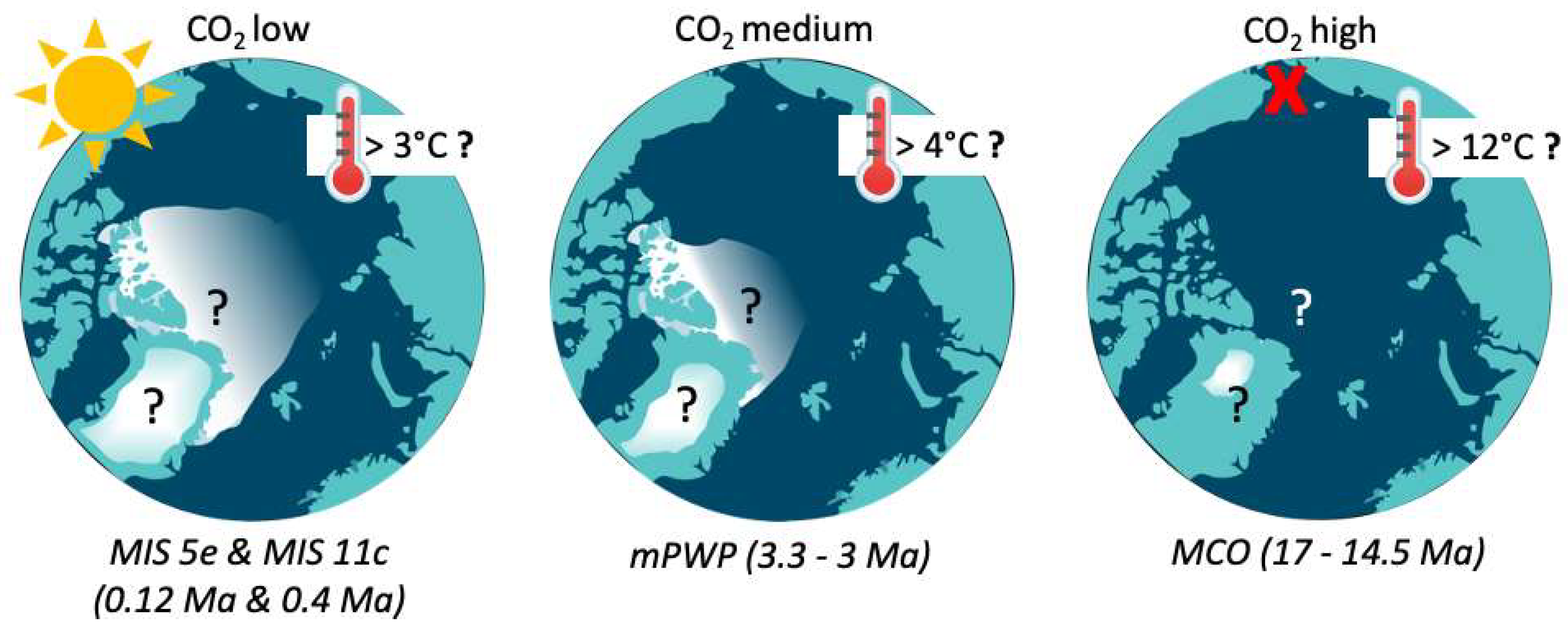

Into the Blue will analyse the characteristics and dynamics of greenhouse intervals in Pleistocene interglacials, and Pliocene–Miocene time intervals with respectively low (~280 parts per million by volume (ppmv)), medium (~400 ppmv) and high (500+ ppmv) atmospheric carbon dioxide (

pCO

2) levels [

39,

40] ((

Figure 1c,

Figure 2).

The Pleistocene interglacials (MIS 11c and 5e), where geological/oceanographical settings are most comparable to today, were influenced by substantial changes in insolation that led to warmer high northern latitudes [

41,

42,

43]. There is no consensus on how exactly the Arctic looked during this period, since empirical and numerical studies yield interpretations of fundamentally different Arctic environments. These interpretations range from warmer-than-present conditions, reduced or absent summer Arctic sea ice, smaller-than-present ice sheets, and an expansion of boreal forests to the Arctic Ocean shoreline [

43,

44], to colder-than-present sea surface conditions in the Arctic-Atlantic gateway (i.e., Fram Strait) and perennial sea ice cover in the central Arctic Ocean, at least for MIS 5e [

45,

46].

The mid Pliocene Warm Period (mPWP) is frequently studied as an analogue for future climate, with empirical data from around the world indicating atmospheric CO

2 concentrations around 400 ppmv [

47], a global surface ocean that is 2-3 ˚C warmer than present and mean surface air temperatures >4

oC higher than today [

48]. Estimates from the Arctic Ocean are however, lacking or equivocal [

49,

50]. Recently produced proxy and modelling data indicate increased ocean warming at higher latitudes, more intense “Atlantification” [

30] and reduced sea ice extent (including ice-free summers) in the Eurasian Arctic during the mPWP [

29,

48], but these are based on few studies, of which none are from the Arctic Ocean proper.

In 2025, global CO

2 concentration exceeded 420 ppmv and is still increasing. As a consequence, the

Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum (MCO), with atmospheric

pCO

2 >500 ppmv and boundary conditions different from today (i.e., ocean gateways,

Figure 2) [

40,

51], has become a key target interval for the science community seeking to understand a greenhouse world (e.g., PAGES PlioMioVar Working Group [

52,

53]. The absence of Arctic geological records, however, means that knowledge about this warm interval is very restricted and remains a challenge for climate models [

54,

55,

56,

57]. It has been suggested that the late Miocene Arctic Ocean was >9 °C warmer than present with only seasonal sea ice cover [

58], however, data from the MCO are lacking. The onset of perennial sea ice cover occurs likely after the MCO [

51,

59]. Hence, for the MCO, we know nothing about how the Arctic cryosphere responded to high global CO

2 concentrations, values we can expect under business-as-usual emissions by the end of the 21st Century.

While we may understand the forcing for the Pliocene and Pleistocene interglacials, for each period we lack information to answer the following questions: How warm was the Arctic? How did the warming proceed and how fast? How did Arctic warming impact the Arctic cryosphere and what are the associated feedbacks to climate? How did Arctic warming and cryosphere changes impact the marine ecosystem?

4. Research Strategy and Tasks

Into the Blue research strategy is shaped by an overarching cross-disciplinary approach to quantify, understand, and assess the impact of cryosphere change in Arctic greenhouse climates. This will be achieved by bringing together the complementary Arctic geoscience and modelling expertise, including paleoglaciology, paleoceanography, paleoclimate and paleogenomics, of research environments in Norway (UiT The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø and NORCE Norwegian Research Centre in Bergen) and Germany (AWI, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven). Together, the

Into the Blue team will recover new and unique Arctic sediment archives (

Figure 1c) and apply novel methods alongside classical techniques for empirical and numerical assessment. Key for the synergies between empirical and modelling activities will be the close integration of the ESMs and ISM with empirical data observations. The project is designed to promote cross-fertilization between disciplines who traditionally work separately and to deliver a balance between high and low risk research, both with high reward. To reap these rewards, we have formed three research tasks and aim to create synergies by employing complementary expertise in proxy and modelling research. The main objectives are: quantifying a warm Arctic in a low, medium, and high

pCO

2 world (Task 1); understanding the dynamics of a warm Arctic cryosphere and ocean (Task 2); and determining the impacts of cryosphere change in a warm Arctic on ocean biosphere and society (Task 3).

Task 1 – Quantifying a Warm Arctic in a Low, Medium and High pCO2 World

In Task 1 we will establish a robust chronostratigraphic framework using a suite of geochronological approaches including geophysical (seismics, paleomagnetism, cosmogenic nuclides), geological (lithology) and biological methods (distribution of ancient life in sediments). Subsequently, we apply a multi-disciplinary paleoceanographic toolbox to reconstruct surface water masses and ocean currents, sea surface temperature and salinity, ocean heat transport, sea ice extent and ice sheet variability using established and novel techniques.

Guided by newly recovered Arctic records,

Into the Blue will thoroughly evaluate existing global climate and ice sheet model simulations, focusing on extracting information on Arctic atmosphere, ocean, sea ice and ice sheets. New reference simulations using the latest versions of NorESM and AWI-ESM [

16,

60] will be performed, following the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP,

https://wcrp-cmip.org/, last access: 22 February 2025) and Paleoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project (PMIP,

https://pmip.lsce.ipsl.fr/, last access: 22 February 2025), which contextualize regional and global changes within a broader international framework. For certain periods of interest, we also aim to apply other gateway and ice sheet configurations in close agreement with the geological boundary conditions.

Task 2 – Understanding the Dynamics of a Warm Arctic Cryosphere and Ocean

In Task 2, we apply various numerical models (ESMs, ISM) to assess the sensitivity and feedbacks of the Arctic ocean-cryosphere system in a warmer world. The main aim is to evaluate the processes leading to or resulting from large-scale past greenhouse climates in the Arctic. These new results will provide invaluable out-of-sample tests for the tools used to simulate future climate and environmental changes suitable for integration to IPCC and policy frameworks (Task 3). We will use the paleoclimatic information from Task 1 to assess further the impact of insolation, CO

2 and tectonic changes on Arctic climate by applying a suite of in-house ESMs (NorESM, AWI-ESM) [

60,

61]. Further, we evaluate uncertainties of changing ice sheets in a warmer world with in-house UiT-ISM. We also study polar amplification of the system with respect to model resolution and CO

2. A mechanistic understanding of ocean-sea ice changes through different phases of Arctic gateways during greenhouse climate states will be evaluated.

Task 3 – The Impacts of a Changed Arctic on Ocean Biosphere and the Society

In Task 3, we will assess how warming in the Arctic impacts the biosphere, but also regional climate outside of the Arctic. We tightly integrate results from Task 1 with a paleogenetics approach, to investigate how a warm Arctic Ocean, with less sea ice and increased Atlantic water inflow, impacts benthic and planktic biodiversity and the biological carbon pump. It is unclear if a warmer Arctic will strengthen or weaken the biological carbon pump, a crucial question to answer as the biological carbon pump is an important modulator of our global atmospheric CO2 concentrations.

Further, we use results from Task 1 and 2 to evaluate potential tipping points in the Arctic realm for past, present, and future. Predicting the future spread of possible Arctic climates, the risks of climate extremes and rapid warming transitions is of high socio-economic relevance. Several studies based on observations and model simulations do find a robust connection between extremes in northern continents and Arctic sea-ice loss [

48,

62]. Despite intense efforts to understand Arctic-midlatitudes climate teleconnections, the effect of climate extremes, such as a blue Arctic Ocean and a deglaciated Greenland, has not been understood in depth and is explored in Task 3.

5. Implementation Strategy

Arctic Field Work

The archives needed for the success of “

Into the Blue” are high-resolution records of key past warm intervals in the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene interglacials. These will be collected via dedicated research expeditions in the Arctic as well as participation in international campaigns like the Integrated Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expedition #403, off Northwest Svalbard, in June 2024 [

17] (

Figure 1c). In 2025, a dedicated

Into the Blue long Calypso piston coring cruise targeting Pleistocene “super-interglacials” from the western Fram Strait to the central Arctic Ocean is planned with the Norwegian research vessel

Kronprins Haakon (

Figure 1c). In 2026, a second central Arctic Ocean expedition is planned with the research vessel

Kronprins Haakon and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to collect samples of exposed Miocene and Pliocene sequences on Lomonosov Ridge [

58]. If the latter expedition is successful, the scientific gain will be high because both the Miocene and Pliocene are, with a few scattered exceptions, “unknown” terrain in the central Arctic and holds the potential of moving our knowledge significantly beyond the state-of-the-art. Towards the end of

Into the Blue, we aim to realize a remotely-operated shallow coring operation (MeBo) at the seafloor on Lomonosov Ridge, central Arctic Ocean, onboard German icebreaker

Polarstern, following a dedicated seismic pre-site survey expedition (LAMEX I) in 2026. There are considerable risks with the feasibility of this last operation (geopolitical, technical, sea ice and weather conditions) but if realized, the recovered material will without a doubt be a gamechanger for understanding the past (warm) Arctic.

Laboratory Facilities

The host institutions (UiT, NORCE, AWI)) have state-of-the-art geological, geochemical and paleogenetic laboratories, essential to work towards the scientific breakthroughs aimed for within

Into the Blue. AWI hosts a world leading organic geochemical analytical infrastructure specifically for sea ice-related biomarker analyses [

20,

63]. NORCE has geological laboratories and a state-of-the-art ancient DNA laboratory. Within the new “PlasmaLab” at UiT (

https://ic3.uit.no/news/plasmalab-ic3), a new mass spectrometer for ultra-high-precision high-sensitivity isotope ratio measurements will be installed at UiT to reconstruct changes in ocean circulation, heat transport and carbon storage. The instrumentation is crucial for applying novel proxies to Arctic climate research as recent success of

Into the Blue team members has shown [

64]. For the Arctic chronological framework,

Into the Blue will work closely with the team of chronology specialists involved in the IODP expedition #403 and the wider scientific community.

Numerical Modelling

Capabilities for Earth System as well as Ice Sheet Modelling have been developed with documented success [

14,

56,

65,

66,

67]. Importantly, recent developments for all numerical models applied within

Into the Blue have considerably improved the computational efficiency that will open new frontiers on how the Arctic climate system responds to past and future climate and environmental extremes. A breakthrough for the new simulations will be the integration of new Earth system components like ice sheets [

13,

68], tides [

10,

69], high-resolution of the spatial domain [

11,

16], and validation of new climate proxy data from Task 1. Crucial parameters (sea surface temperatures, sea-ice, glacial ice, ocean circulation, heat transport) will provide an optimal baseline for data-model intercomparison studies. If Task 1 faces unexpected challenges to provide observational data from a single proxy, we will rely on our multi-proxy data set of different physical parameters that will inform the modelled results. The timeliness of the data-model integration lies in revolutionary breakthroughs in ESM/ISMs evolution over recent decades facilitated by the considerable increase in computational capacity. The models are in-house combined with community developments and ready to produce high gains for

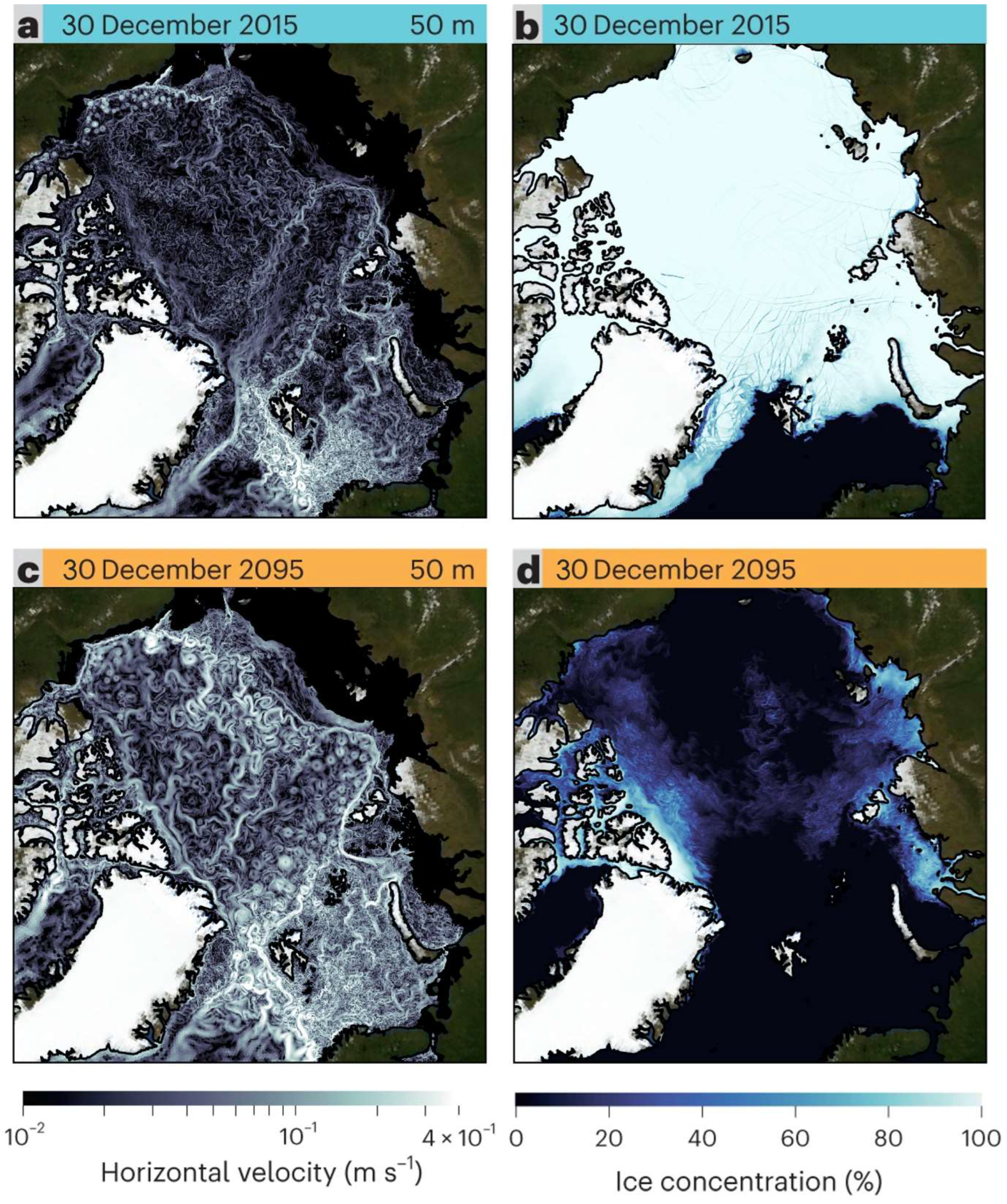

Into the Blue. In particular, the eddy- and storm resolving model (

Figure 3) is expected to open new frontiers on how the Arctic responds in a high CO

2 world by evaluating the impact on past and future climate and environmental extremes [

70,

71].

6. Expected Outcomes and Impact

The

Into the Blue ERC Synergy project, with a duration of 72 months started on November 1st 2024, and will play a central role in international Arctic research ahead of the International Polar Year in 2032/2033. We will raise interest and increase knowledge about changing polar environments by connecting and engaging scientists, the wider public, stakeholders and educators, to ensure maximum impact and legacy. The impact and understanding of amplified polar climate warming on the Earth climate system has reached a global dimension with a vast scientific interest documented [

8,

18,

72,

73,

74].

Into the Blue provides a boost of new samples, data, ages, geological interpretation, and climate models which will become publicly available in the best (open access) journals to stimulate discussion within academia and provide a new, solid baseline to address pressing scientific challenges in the field of Arctic climate change. The new material will be made available to the research community to apply the most sophisticated and novel methodologies for new research questions beyond the lifetime of

Into the Blue and will underpin future cryosphere-inclusive IPCC assessments. New Arctic climate records derived from

Into the Blue will facilitate unique testing of Earth system (NorESM, AWI-ESM) and ice sheet (UiT ISM, PISM, CISM) models out of the “comfort zone of present-day climate” [

13,

14]. A new generation of storm-and-eddy resolving ESMs will be validated with new climate records for selected warmer-than-present states. The AWI-ESM is presently capable of running global coupled simulations at multiple scales in the ocean and over sea-ice with sufficient data on state-of-the-art supercomputers, defining a new step in creating value for society. “

Into the Blue” aims to make the following research impacts:

- a.

Into the Blue will document a blue Arctic under warmer background conditions than today thereby expanding horizons beyond scientific relevance on the impact of climate extremes, such as an ice-free Arctic Ocean and reduced Greenland Ice Sheet for nature and society.

- b.

Into the Blue will use marine sedaDNA for sea ice, biodiversity and ecosystem reconstructions in past warm intervals. It will allow to understand how a blue Arctic impacts the ecosystem and the biological pump, information crucial for Arctic habitat conservation and potential ecosystem services.

- c.

Into the Blue is a concerted research project for the Arctic that provides solutions on the processes and dynamics that connect ocean, ice, life, and climate in a high pCO2 world, information essential to underpin cryosphere-inclusive IPCC assessment.

- d.

Into the Blue will be first in explicitly representing essential polar processes for the warm past and potential warm future. Our eddy- and storm-resolving model is expected to open new frontiers on how the system responds to human activities in a high CO2 world by evaluating the impact on past and future climate and environmental extremes.

Taken together, a key challenge for humanity is how a blue Arctic will respond to and drive an increasingly warmer future climate. To date, we lack a concerted research framework to assess this critical knowledge gap along with the key datasets to study the mechanisms underlying the rapid transition to a blue Arctic in response to global warming. ERC Synergy Grant Project Into the Blue will solve this “Arctic Challenge” with a synergistic approach to retrieve and study, ground-breaking new Arctic records together with Earth System Models and Ice Sheet Models. This will mark a step-change in Arctic climate research, providing unique scientific gains of how the cryosphere (sea ice and glacial ice) evolves under past “greenhouse” (warmer-than-present) climate states.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., G.L., S.D.S., P.M.L., M.E., M.W., J.M.; Original draft preparation, J.K., G.L., S.D.S.; Writing—review and editing, J.K., G.L., S.D.S., P.M.L., M.E., M.W., J.M; funding acquisition, J.K., G.L., S.D.S., P.M.L., M.E., M.W., J.M.

Funding

This manuscript is based on a research proposal submitted to and currently funded by the European Research Council (ERC) Synergy Grant scheme through grant no. 101118519.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Tore Guneriussen, Theresa Mikalsen, and Matthias Forwick (UiT), Aud Larsen, and Ryan Weber (NORCE), and Tordis Hellmann and Imke Fries (AWI) for administrative support, comments and assistance. We also warmly thank all Into the Blue team members and collaborators.

References

- Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, X.B.; Church, J.A.; Watson, C.S.; King, M.A.; Monselesan, D.; Legresy, B.; Harig, C. The increasing rate of global mean sea-level rise during 1993-2014. Nature Climate Change 2017, 7, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: 2021.

- Heuzé, C.; Jahn, A. The first ice-free day in the Arctic Ocean could occur before 2030. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T.; Canosa, I.V.; Harper, S. The rapidly changing Arctic and its societal implications. WIREs Climate Change 2021, 12, e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijs, A.; Schouten, S.; Pagani, M.; Woltering, M.; Brinkhuis, H.; Damste, J.S.S.; Dickens, G.R.; Huber, M.; Reichart, G.J.; Stein, R.; et al. Subtropical arctic ocean temperatures during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum. Nature 2006, 441, 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkhuis, H.; Schouten, S.; Collinson, M.E.; Sluijs, A.; Damste, J.S.S.; Dickens, G.R.; Huber, M.; Cronin, T.M.; Onodera, J.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Episodic fresh surface waters in the Eocene Arctic Ocean. Nature 2006, 441, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.; Backman, J.; Brinkhuis, H.; Clemens, S.C.; Cronin, T.; Dickens, G.R.; Eynaud, F.; Gattacceca, J.; Jakobsson, M.; Jordan, R.W.; et al. The Cenozoic palaeoenvironment of the Arctic Ocean. Nature 2006, 441, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, M.; Karpechko, A.Y.; Lipponen, A.; Nordling, K.; Hyvärinen, O.; Ruosteenoja, K.; Vihma, T.; Laaksonen, A. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979. Communications Earth & Environment 2022, 3, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Zhang, X.; Francis, J.; Jung, T.; Kwok, R.; Overland, J.; Ballinger, T.; Bhatt, U.; Chen, H.; Coumou, D. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nature Climate Change 2020, 10, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Årthun, M.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, F. Arctic Ocean Amplification in a warming climate in CMIP6 models. Science advances 2022, 8, eabn9755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, G.; Butzin, M.; Eissner, N.; Shi, X.; Stepanek, C. Abrupt climate and weather changes across time scales. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2020, 35, e2019PA003782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, G.; Pfeiffer, M.; Laepple, T.; Leduc, G.; Kim, J.-H. A model–data comparison of the Holocene global sea surface temperature evolution. Climate of the Past 2013, 9, 1807–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, L.; Danek, C.; Gierz, P.; Lohmann, G. AMOC Recovery in a Multicentennial Scenario Using a Coupled Atmosphere-Ocean-Ice Sheet Model. Geophysical Research Letters 2020, 47, e2019GL086810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, H.; Hubbard, A.; Bradwell, T.; Schomacker, A. The configuration, sensitivity and rapid retreat of the Late Weichselian Icelandic ice sheet. Earth-Science Reviews 2017, 166, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streffing, J.; Semmler, T.; Zampieri, L.; Jung, T. Response of Northern Hemisphere weather and climate to Arctic sea ice decline: Resolution independence in Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) simulations. Journal of Climate 2021, 34, 8445–8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streffing, J.; Sidorenko, D.; Semmler, T.; Zampieri, L.; Scholz, P.; Andrés-Martínez, M.; Koldunov, N.; Rackow, T.; Kjellsson, J.; Goessling, H. AWI-CM3 coupled climate model: description and evaluation experiments for a prototype post-CMIP6 model. Geoscientific Model Development 2022, 15, 6399–6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchi, R.G.; St. John, K.E.K.; Ronge, T.A.; and the Expedition 403 Scientists. Expedition 403 Preliminary Report: Eastern Fram Strait Paleo-Archive; International Ocean Discovery Program: 2024.

- Slater, T.; Lawrence, I.R.; Otosaka, I.N.; Shepherd, A.; Gourmelen, N.; Jakob, L.; Tepes, P.; Gilbert, L.; Nienow, P. Review article: Earth’s ice imbalance. The Cryosphere 2021, 15, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R. The Late Mesozoic-Cenozoic Arctic Ocean Climate and Sea Ice History: A Challenge for Past and Future Scientific Ocean Drilling. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2019, 34, 1851–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knies, J.; Cabedo-Sanz, P.; Belt, S.T.; Baranwal, S.; Fietz, S.; Rosell-Mele, A. The emergence of modern sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. Nature Communications 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnard, C.; Zdanowicz, C.M.; Fisher, D.A.; Isaksson, E.; de Vernal, A.; Thompson, L.G. Reconstructed changes in Arctic sea ice over the past 1,450 years. Nature 2011, 479, 509–U231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notz, D.; Stroeve, J. Observed Arctic sea-ice loss directly follows anthropogenic CO2 emission. Science 2016, 354, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; 2019; p. 179.

- Huang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Tan, X. On the pattern of CO2 radiative forcing and poleward energy transport. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2017, 122, 10–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asbjørnsen, H.; Årthun, M.; Skagseth, Ø.; Eldevik, T. Mechanisms Underlying Recent Arctic Atlantification. Geophysical Research Letters 2020, 47, e2020GL088036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Holding, J.M.; Carmack, E.C. Understanding Regional and Seasonal Variability Is Key to Gaining a Pan-Arctic Perspective on Arctic Ocean Freshening. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, S.; Ingvaldsen, R.B.; Furevik, T. Arctic warming hotspot in the northern Barents Sea linked to declining sea-ice import. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielhagen, R.F.; Werner, K.; Sorensen, S.A.; Zamelczyk, K.; Kandiano, E.; Budeus, G.; Husum, K.; Marchitto, T.M.; Hald, M. Enhanced Modern Heat Transfer to the Arctic by Warm Atlantic Water. Science 2011, 331, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, W.; Smik, L.; Koseoglu, D.; Lathika, N.; Tarique, M.; Thamban, M.; Haywood, A.; Belt, S.T.; Knies, J. Reduced Arctic sea ice extent during the mid-Pliocene Warm Period concurrent with increased Atlantic-climate regime. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2020, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, I.V.; Pnyushkov, A.V.; Alkire, M.B.; Ashik, I.M.; Baumann, T.M.; Carmack, E.C.; Goszczko, I.; Guthrie, J.; Ivanov, V.V.; Kanzow, T. Greater role for Atlantic inflows on sea-ice loss in the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Science 2017, 356, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.; Kanzow, T.; von Appen, W.-J.; von Albedyll, L.; Arndt, J.E.; Roberts, D.H. Bathymetry constrains ocean heat supply to Greenland’s largest glacier tongue. Nature Geoscience 2020, 13, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.M.; Thomas, R.H.; De Young, B.; Ribergaard, M.H.; Lyberth, B. Acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbræ triggered by warm subsurface ocean waters. Nature geoscience 2008, 1, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowton, T.; Sole, A.; Nienow, P.; Slater, D.; Wilton, D.; Hanna, E. Controls on the transport of oceanic heat to Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier, East Greenland. Journal of Glaciology 2016, 62, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straneo, F.; Hamilton, G.S.; Stearns, L.A.; Sutherland, D.A. Connecting the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Ocean: A case study of Helheim glacier and Sermlik Fjord. Oceanography 2016, 29, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M.; Rignot, E.; Fenty, I.; An, L.; Bjørk, A.; van den Broeke, M.; Cai, C.; Kane, E.; Menemenlis, D.; Millan, R.; et al. Ocean forcing drives glacier retreat in Greenland. Science Advances 2021, 7, eaba7282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, E.; Fettweis, X.; Mernild, S.H.; Cappelen, J.; Ribergaard, M.H.; Shuman, C.A.; Steffen, K.; Wood, L.; Mote, T.L. Atmospheric and oceanic climate forcing of the exceptional Greenland ice sheet surface melt in summer 2012. International Journal of Climatology 2014, 34, 1022–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhasse, A.; Fettweis, X.; Kittel, C.; Amory, C.; Agosta, C. Brief communication: Impact of the recent atmospheric circulation change in summer on the future surface mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet. The Cryosphere 2018, 12, 3409–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderlin, E.M.; Howat, I.M.; Jeong, S.; Noh, M.J.; van Angelen, J.H.; van den Broeke, M.R. An improved mass budget for the Greenland ice sheet. Geophysical Research Letters 2014, 41, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berends, C.J.; de Boer, B.; Dolan, A.M.; Hill, D.J.; van de Wal, R.S.W. Modelling ice sheet evolution and atmospheric CO2 during the Late Pliocene. Climate of the Past 2019, 15, 1603–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, J.W.B.; Zhang, Y.G.; Liu, X.; Foster, G.L.; Stoll, H.M.; Whiteford, R.D.M. Atmospheric CO2 over the Past 66 Million Years from Marine Archives. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2021, 49, 609–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.A.; Langen, P.L.; Vinther, B.M. The last interglacial climate: comparing direct and indirect impacts of insolation changes. Climate Dynamics 2017, 48, 3391–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzedakis, P.C.; Hodell, D.A.; Nehrbass-Ahles, C.; Mitsui, T.; Wolff, E.W. Marine Isotope Stage 11c: An unusual interglacial. Quaternary Science Reviews 2022, 284, 107493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Members, C.-L.I.P. Last Interglacial Arctic warmth confirms polar amplification of climate change. Quaternary Science Reviews 2006, 25, 1383–1400. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, T.M.; Keller, K.J.; Farmer, J.R.; Schaller, M.F.; O’Regan, M.; Poirier, R.; Coxall, H.; Dwyer, G.S.; Bauch, H.; Kindstedt, I.G.; et al. Interglacial Paleoclimate in the Arctic. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2019, 34, 1959–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuravleva, A.; Bauch, H.A.; Spielhagen, R.F. Atlantic water heat transfer through the Arctic Gateway (Fram Strait) during the Last Interglacial. Global and Planetary Change 2017, 157, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.; Fahl, K.; Gierz, P.; Niessen, F.; Lohmann, G. Arctic Ocean sea ice cover during the penultimate glacial and the last interglacial. Nature communications 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, O.; Foster, G.L.; Schmidt, D.N.; Mackensen, A.; Kawamura, K.; Pancost, R.D. Alkenone and boron-based Pliocene pCO2 records. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2010, 292, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nooijer, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, C.; Nisancioglu, K.H.; Haywood, A.M.; Tindall, J.C.; et al. Evaluation of Arctic warming in mid-Pliocene climate simulations. Clim. Past 2020, 16, 2325–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, E.L.; Ford, H.L.; Ho, S.L.; Tindall, J.C.; Haywood, A.M.; Alonso-Garcia, M.; Bailey, I.; Berke, M.A.; Littler, K.; Patterson, M.O. Lessons from a high-CO 2 world: an ocean view from∼ 3 million years ago. Climate of the Past 2020, 16, 1599–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, H.J.; Robinson, M.M.; Haywood, A.M.; Hill, D.J.; Dolan, A.M.; Stoll, D.K.; Chan, W.-L.; Abe-Ouchi, A.; Chandler, M.A.; Rosenbloom, N.A.; et al. Assessing confidence in Pliocene sea surface temperatures to evaluate predictive models. Nature Climate Change 2012, 2, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinthorsdottir, M.; Coxall, H.K.; de Boer, A.M.; Huber, M.; Barbolini, N.; Bradshaw, C.D.; Burls, N.J.; Feakins, S.J.; Gasson, E.; Henderiks, J.; et al. The Miocene: the Future of the Past. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2021, n/a, e2020PA004037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, H.L. Expanding PlioVAR to PlioMioVAR; Copernicus Meetings: 2022.

- Knorr, G.; Lohmann, G. Climate warming during Antarctic ice sheet expansion at the Middle Miocene transition. Nature Geoscience 2014, 7, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, N.; Huber, M.; Müller, R.D.; Seton, M. Modeling the Miocene climatic optimum: Ocean circulation. Paleoceanography 2012, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldner, A.; Herold, N.; Huber, M. The challenge of simulating the warmth of the mid-Miocene climatic optimum in CESM1. Clim. Past 2014, 10, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, G.; Knorr, G.; Hossain, A.; Stepanek, C. Effects of CO2 and ocean mixing on Miocene and Pliocene temperature gradients. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2022, 37, e2020PA003953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starz, M.; Jokat, W.; Knorr, G.; Lohmann, G. Threshold in North Atlantic-Arctic Ocean circulation controlled by the subsidence of the Greenland-Scotland Ridge. Nature Communications 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, R.; Fahl, K.; Schreck, M.; Knorr, G.; Niessen, F.; Forwick, M.; Gebhardt, C.; Jensen, L.; Kaminski, M.; Kopf, A.; et al. Evidence for ice-free summers in the late Miocene central Arctic Ocean. Nature Communications 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, A.A.; Andreeva, I.A.; Vogt, C.; Backman, J.; Krupskaya, V.V.; Grikurov, G.E.; Moran, K.; Shoji, H. A shift in heavy and clay mineral provenance indicates a middle Miocene onset of a perennial sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. Paleoceanography 2008, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorenko, D.; Goessling, H.F.; Koldunov, N.; Scholz, P.; Danilov, S.; Barbi, D.; Cabos, W.; Gurses, O.; Harig, S.; Hinrichs, C. Evaluation of FESOM2. 0 coupled to ECHAM6. 3: preindustrial and HighResMIP simulations. Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems 2019, 11, 3794–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaideanu, P.; Stepanek, C.; Dima, M.; Schrepfer, J.; Matos, F.; Ionita, M.; Lohmann, G. Large-scale sea ice–Surface temperature variability linked to Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Plos one 2023, 18, e0290437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contzen, J.; Dickhaus, T.; Lohmann, G. Long-term temporal evolution of extreme temperature in a warming Earth. Plos one 2023, 18, e0280503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Stein, R. High-resolution record of late glacial and deglacial sea ice changes in Fram Strait corroborates ice–ocean interactions during abrupt climate shifts. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 2014, 403, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, C.S.; Ezat, M.M.; Roberts, N.L.; Bauch, H.A.; Spielhagen, R.F.; Noormets, R.; Polyak, L.; Moreton, S.G.; Rasmussen, T.L.; Sarnthein, M. Active Nordic Seas deep-water formation during the last glacial maximum. Nature Geoscience 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, H.; Hubbard, A.; Andreassen, K.; Auriac, A.; Whitehouse, P.L.; Stroeven, A.P.; Shackleton, C.; Winsborrow, M.; Heyman, J.; Hall, A.M. Deglaciation of the Eurasian ice sheet complex. Quaternary Science Reviews 2017, 169, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Knorr, G.; Jokat, W.; Lohmann, G. Opening of the Fram Strait led to the establishment of a modern-like three-layer stratification in the Arctic Ocean during the Miocene. arktos 2021, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Knorr, G.; Lohmann, G.; Stärz, M.; Jokat, W. Simulated thermohaline fingerprints in response to different Greenland-Scotland Ridge and Fram Strait subsidence histories. Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology 2020, 35, e2019PA003842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Lohmann, G.; Gierz, P.; Gowan, E.J.; Knorr, G. Coupled climate-ice sheet modelling of MIS-13 reveals a sensitive Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Global and Planetary Change 2021, 200, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Song, P.; Chen, X.; Lohmann, G. Glacial AMOC shoaling despite vigorous tidal dissipation: Vertical stratification matters. Climate of the Past 2024, 20, 2001–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Danilov, S.; Koldunov, N.; Liu, C.; Müller, V.; Sidorenko, D.; Jung, T. Eddy activity in the Arctic Ocean projected to surge in a warming world. Nature Climate Change 2024, 14, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, R.; Wolf, K.K.; Hoppe, C.J.; Wu, L.; Lohmann, G. The changing nature of future Arctic marine heatwaves and its potential impacts on the ecosystem. Nature Climate Change 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibert, W.; Matthiessen, J.; Stimac, I.; Wollenburg, J.; Stein, R. Glacial episodes of a freshwater Arctic Ocean covered by a thick ice shelf. Nature 2021, 590, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, R.; McNabb, R.; Berthier, E.; Menounos, B.; Nuth, C.; Girod, L.; Farinotti, D.; Huss, M.; Dussaillant, I.; Brun, F. Accelerated global glacier mass loss in the early twenty-first century. Nature 2021, 592, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, J.E.; Hubbard, A.; Bahr, D.B.; Colgan, W.T.; Fettweis, X.; Mankoff, K.D.; Wehrlé, A.; Noël, B.; van den Broeke, M.R.; Wouters, B.; et al. Greenland ice sheet climate disequilibrium and committed sea-level rise. Nature Climate Change 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).