Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

21 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data

3. Results

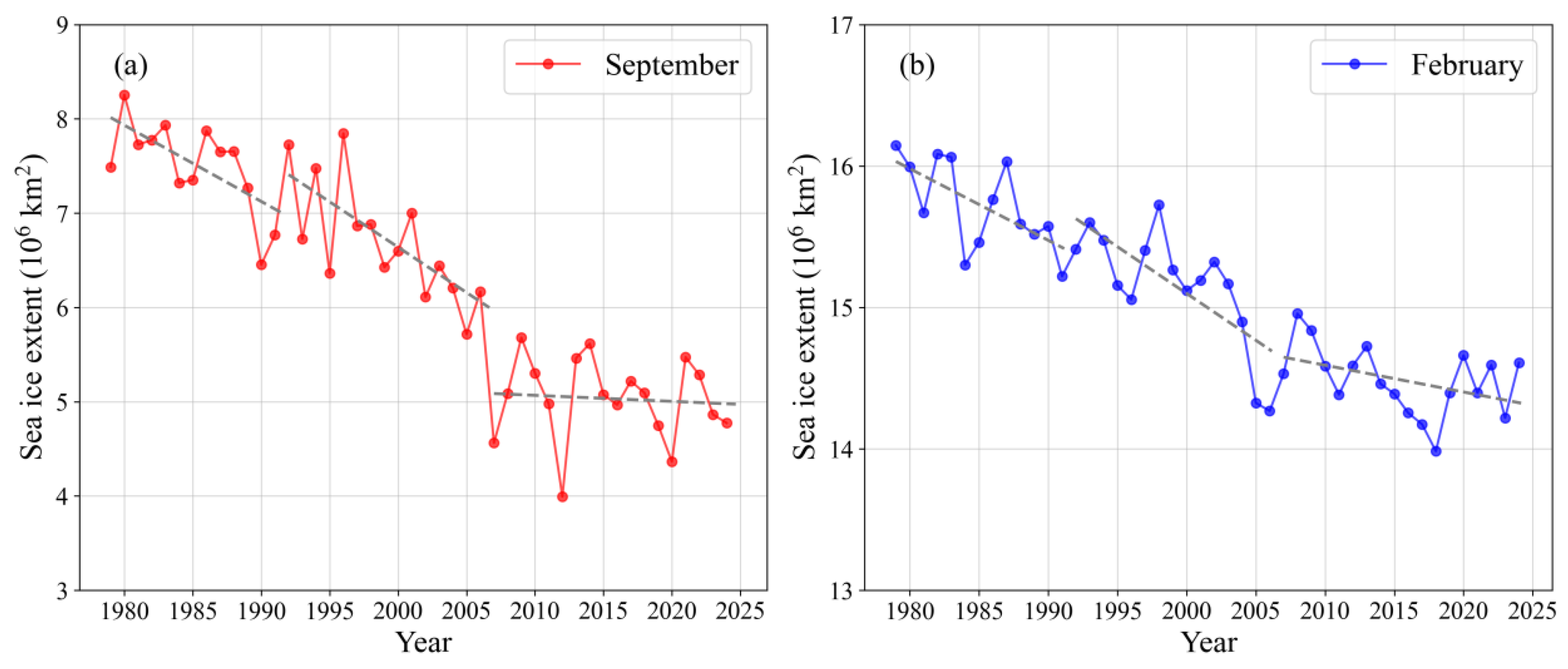

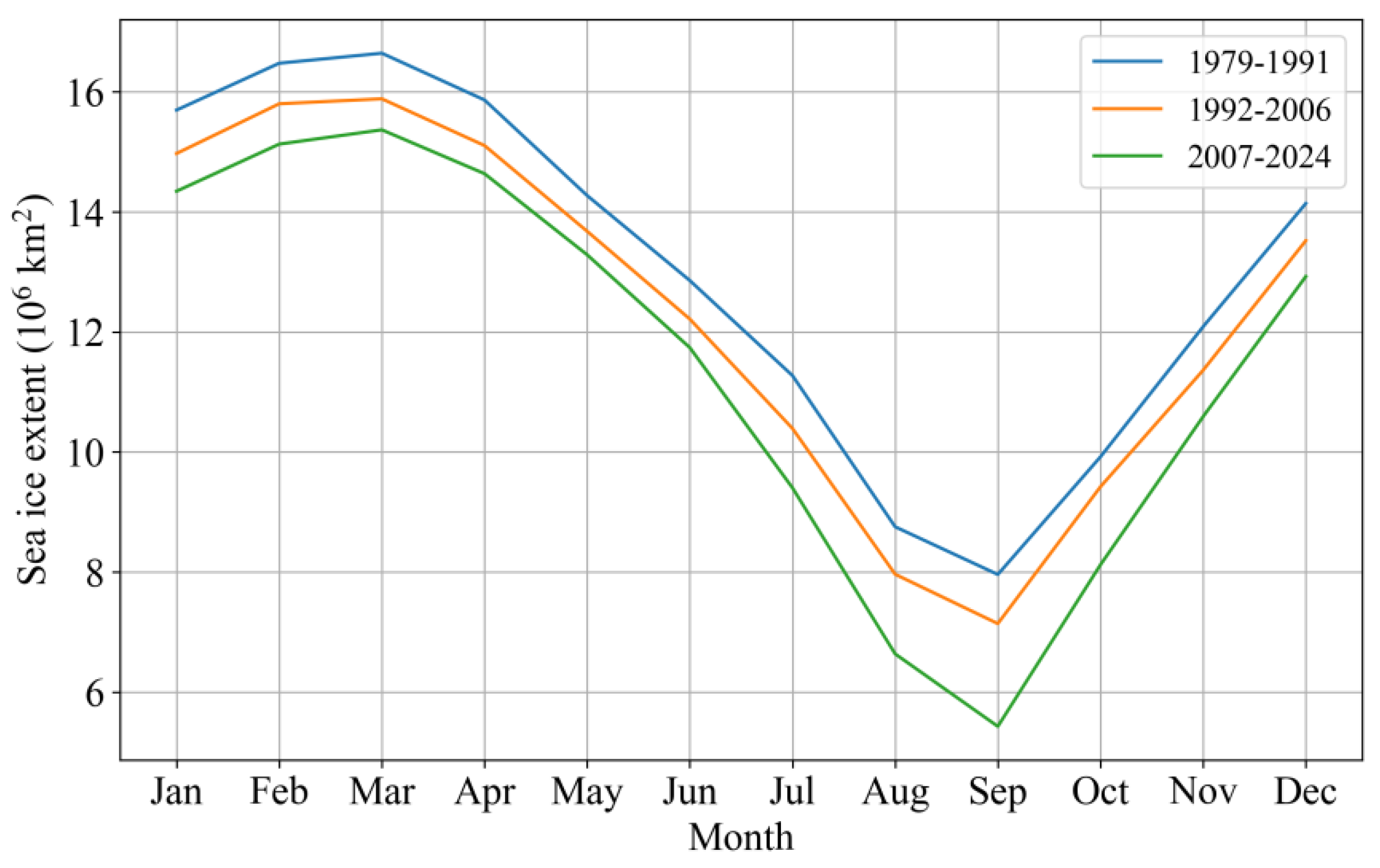

3.1. Pattern of Arctic Sea-Ice State Transitions

3.2. Mechanisms of Sea-Ice Concentration State Transitions

4. Conclusions and Discussion

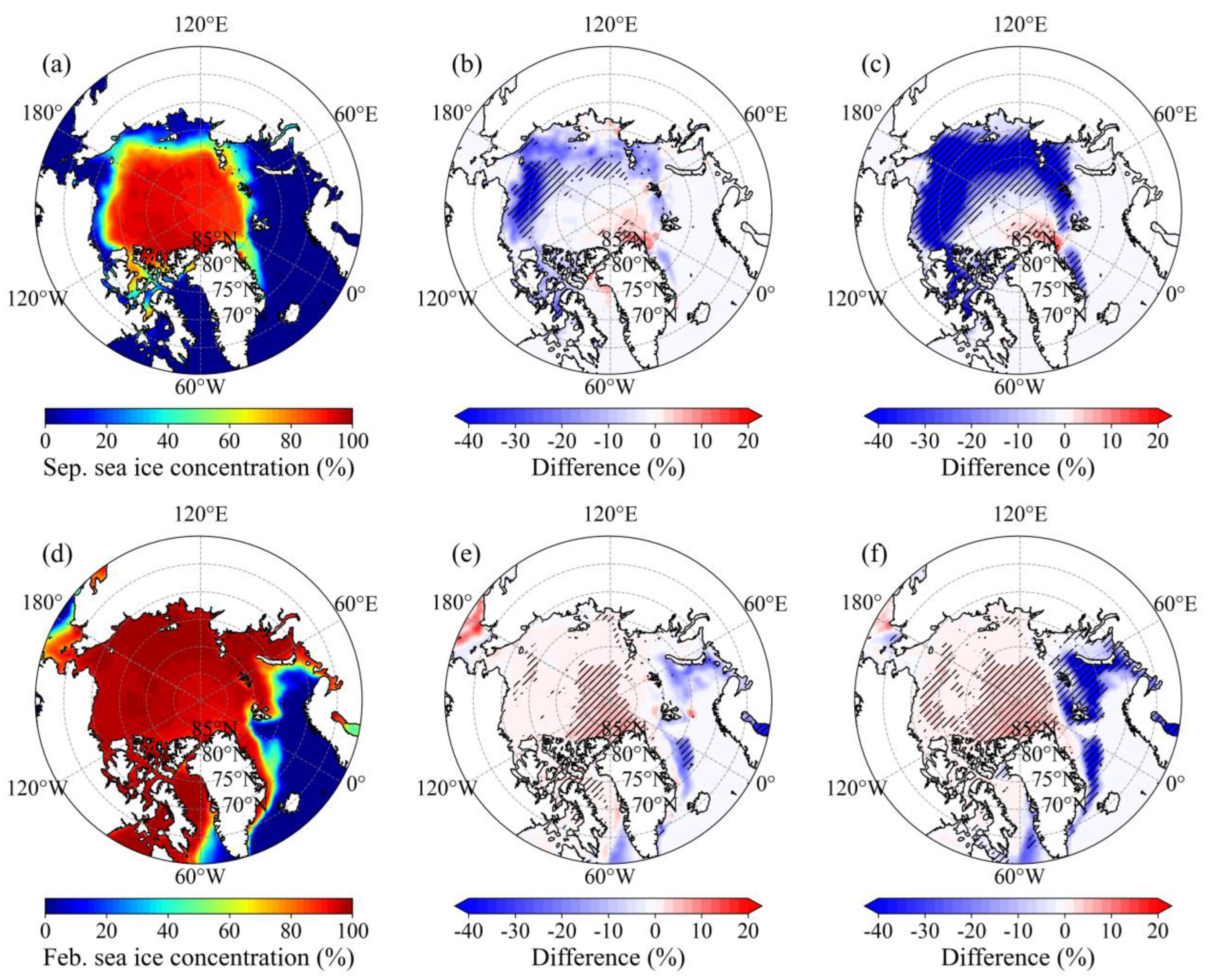

- The stepwise contraction of Arctic SIE across 1979-1991, 1992-2006 and 2007-2024 is primarily attributable to intensified melt within the 70°N-80°N Arctic belt in September and within the Barents and the Greenland seas in February, with the most pronounced SIC reductions occurring during 2007-2024. Over the same intervals, the September SIC north of Greenland and February SIC in the central Arctic Ocean exhibit a modest yet statistically significant increase.

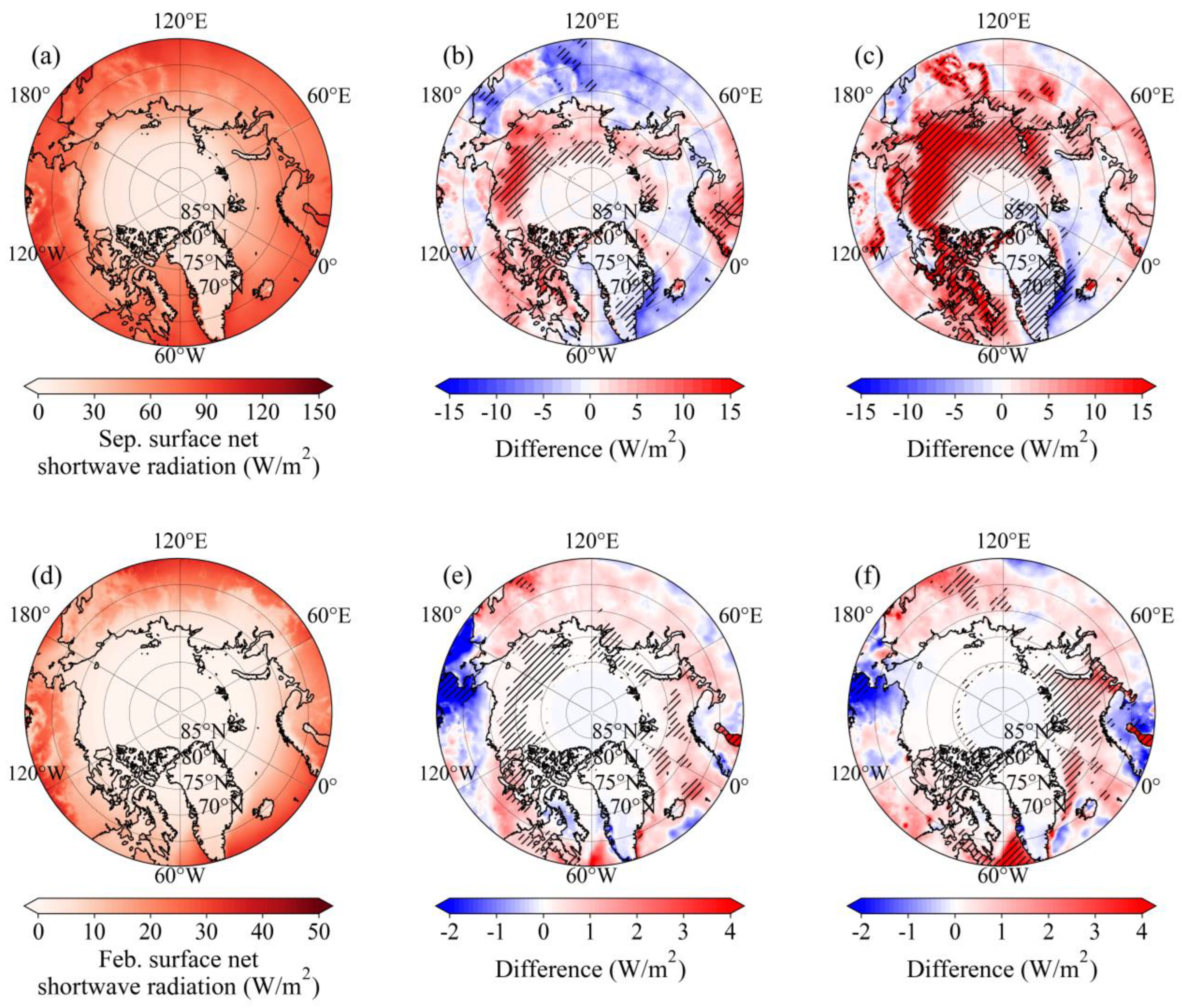

- Concurrent increases in SNSR, T2m, and SST prevail across the 70°N-80°N Arctic belt in summer and Barents and Greenland seas in winter across three periods, with accelerations most pronounced in 2007-2024. These synchronized surface-energy anomalies drive the observed stepwise SIC retreat, culminating in the record ice losses of 2007-2024.

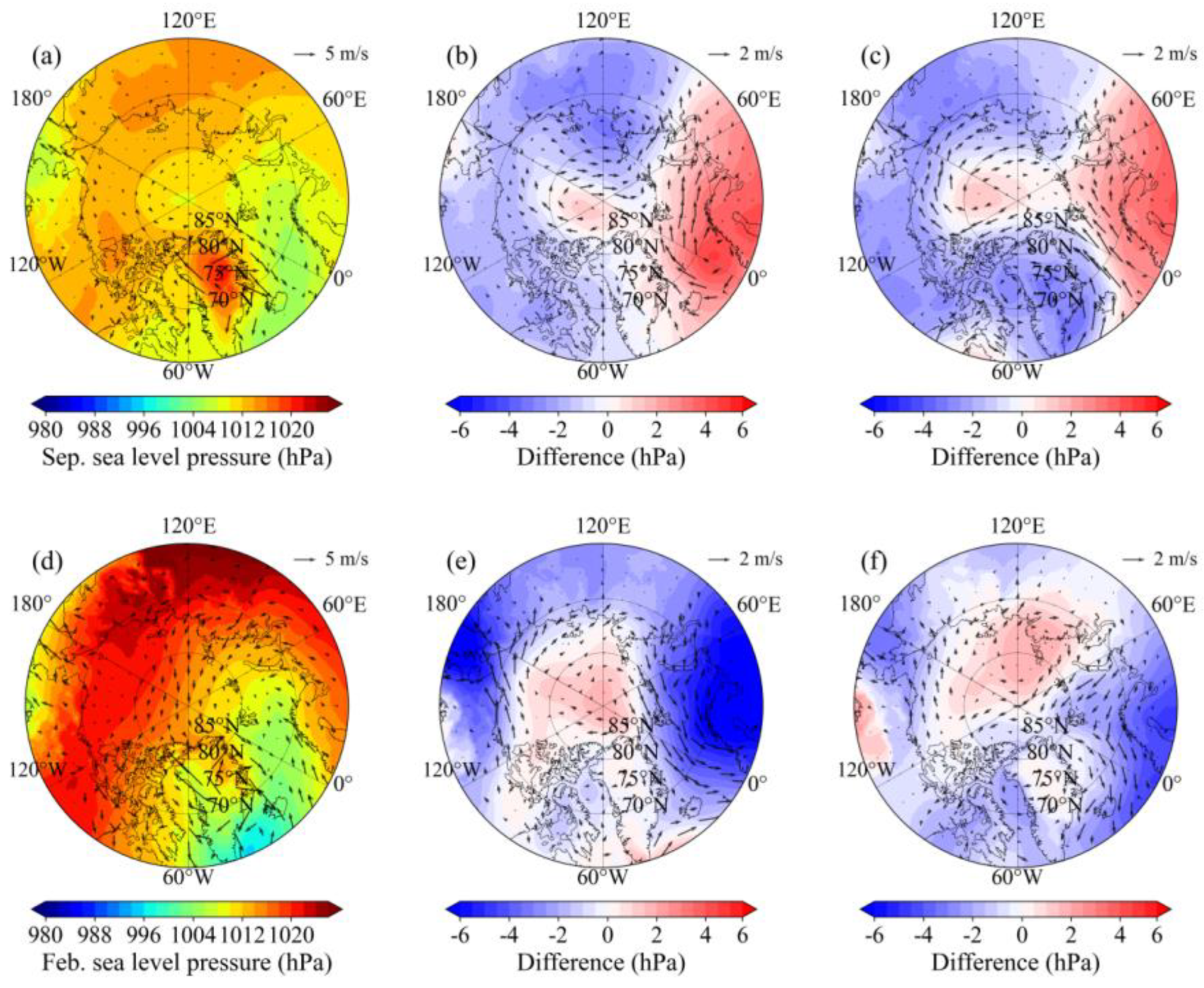

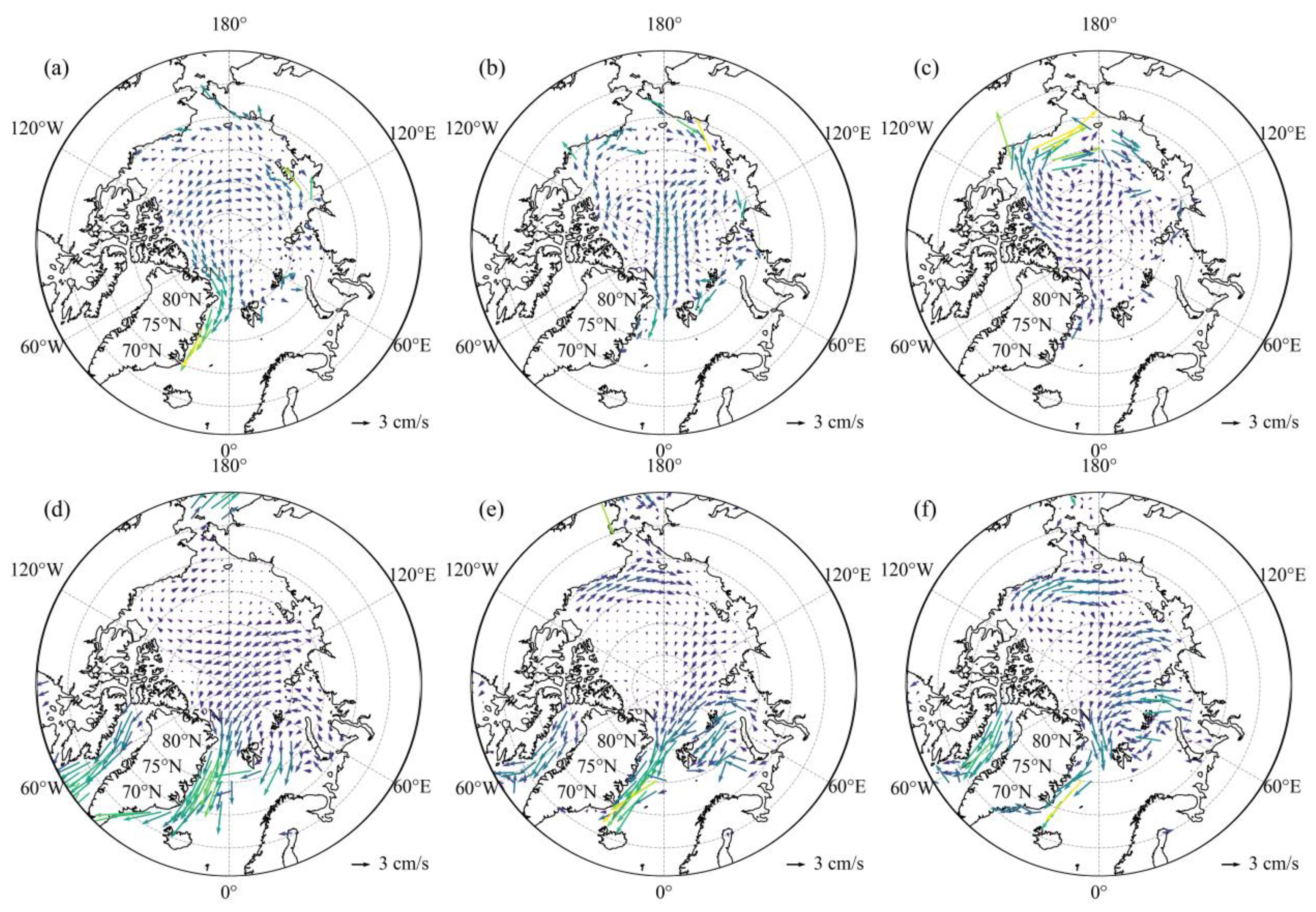

- The SIC increase north of Greenland and in the central Arctic Ocean is inconsistent with weak or opposing thermal anomalies, implicating dynamical drivers. High-pressure anomaly over the central Arctic in 1992-2006 and 2007-2024 intensifies anticyclonic circulation, driving wind-driven ice convergence into these regions and sustaining the observed SIC increase. As the high-pressure centre migrates north of Russia, both convergence and SIC are further amplified in the central Arctic Ocean in 2007-2024.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stroeve, J. C.; Serreze, M. C.; Holland, M. M.; Kay, J. E.; Malanik, J.; Barrett, A. P. The Arctic’s rapidly shrinking sea ice cover: a research synthesis. Clim. change 2012, 110, 1005-1027. [CrossRef]

- Cavalieri, D. J.; Parkinson, C. L. Arctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979-2010. Cryosphere 2012, 6(4), 881-889. [CrossRef]

- Meier, W. N.; Stroeve, J. An updated assessment of the changing Arctic sea ice cover. Oceanography 2022, 35(3/4), 10-19. [CrossRef]

- Maslanik, J. A.; Fowler, C.; Stroeve, J.; Drobot, S.; Zwally, J.; Yi, D.; Emery, W. A younger, thinner Arctic ice cover: Increased potential for rapid, extensive sea-ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34(24). [CrossRef]

- Lei R.; Xie H.; Wang J.; et al. Changes in sea ice conditions along the Arctic Northeast Passage from 1979 to 2012. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2015, 119, 132-144. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R. Arctic sea ice thickness, volume, and multiyear ice coverage: losses and coupled variability (1958-2018). Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13(10), 105005. [CrossRef]

- Sumata, H.; de Steur, L.; Divine, D.V.; Granskog, M. A.; Gerland, S. Regime shift in Arctic Ocean sea ice thickness. Nature 2023, 615, 443-449. [CrossRef]

- Krikken, F.; Hazeleger, W. Arctic energy budget in relation to sea ice variability on monthly-to-annual time scales. J. Climate 2015, 28(16), 6335-6350. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. M.; Dunstone, N. J.; Scaife, A. A.; Fiedler, E. K.; Copsey, D.; Hardiman, S. C. Atmospheric response to Arctic and Antarctic sea ice: The importance of ocean–atmosphere coupling and the background state. J. Climate 2017, 30(12), 4547-4565. [CrossRef]

- Sévellec, F.; Fedorov, A. V.; Liu, W. Arctic sea-ice decline weakens the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7(8), 604-610. [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, G.; Marshall, J.; Timmermans, M. L.; Scott, J. Observations of seasonal upwelling and downwelling in the Beaufort Sea mediated by sea ice. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 2018, 48(4), 795-805. [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Ouyang, Z.; Chen, L.; et al. Climate change drives rapid decadal acidification in the Arctic Ocean from 1994 to 2020. Science 2022, 377(6614), 1544-1550. [CrossRef]

- Stroeve, J.; Serreze, M.; Drobot, S.; et al. Arctic Sea Ice Extent Plummets in 2007. Eos Trans. AGU 2008, 89(2), 13–14. [CrossRef]

- Holland, M. The great sea-ice dwindle. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6(1), 10-11. [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, I. V.; Ingvaldsen, R. B.; Pnyushkov, A. V.; et al. Fluctuating Atlantic inflows modulate Arctic atlantification. Science 2023, 381(6661), 972-979. [CrossRef]

- Kay, J. E.; Holland, M. M.; Jahn, A. Inter-annual to multi-decadal Arctic sea ice extent trends in a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38(15). [CrossRef]

- Notz, D.; Stroeve, J. Observed Arctic sea-ice loss directly follows anthropogenic CO2 emission. Science 2016, 354(6313), 747-750. [CrossRef]

- Swart, N. C.; Fyfe, J. C.; Hawkins, E.; Kay, J. E.; Jahn, A. Influence of internal variability on Arctic sea-ice trends. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5(2), 86-89. [CrossRef]

- Carmack, E.; Polyakov, I.; Padman, L.; et al. Toward quantifying the increasing role of oceanic heat in sea ice loss in the new Arctic. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2015, 96(12), 2079-2105. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Schweiger, A.; L’Heureux, M.; et al. Influence of high-latitude atmospheric circulation changes on summertime Arctic sea ice. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7(4), 289-295. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Schweiger, A.; Baxter, I. Nudging observed winds in the Arctic to quantify associated sea ice loss from 1979 to 2020. J. Climate 2022, 35(20), 6797-6813. [CrossRef]

- Francis, J. A.; Wu, B. Why has no new record-minimum Arctic sea-ice extent occurred since September 2012? Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15(11), 114034. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, I.; Ding, Q. An optimal atmospheric circulation mode in the Arctic favoring strong summertime sea ice melting and ice–albedo feedback. J. Climate 2022, 35(20), 6627-6645. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, X.; Bi, H.; et al. A comparison of factors that led to the extreme sea ice minima in the twenty-first century in the Arctic Ocean. J. Climate 2022, 35(4), 1249-1265. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lei, R.; Zhai, M.; et al. The impacts of anomalies in atmospheric circulations on Arctic sea ice outflow and sea ice conditions in the Barents and Greenland seas: case study in 2020. Cryosphere 2023, 17(11), 4609-4628. [CrossRef]

- Årthun, M.; Eldevik, T.; Smedsrud, L. H.; Skagseth, Ø.; Ingvaldsen, R. B. Quantifying the influence of Atlantic heat on Barents Sea ice variability and retreat. J. Climate 2012, 25(13), 4736-4743. [CrossRef]

- Auclair, G.; Tremblay, L. B. The role of ocean heat transport in rapid sea ice declines in the Community Earth System Model Large Ensemble. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2018, 123(12), 8941-8957. [CrossRef]

- Docquier, D.; Koenigk, T. A review of interactions between ocean heat transport and Arctic sea ice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16(12), 123002. [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, T.; Sørensen, A. M.; Kern, S.; et al. Version 2 of the EUMETSAT OSI SAF and ESA CCI Sea-Ice Concentration Climate Data Records. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 49–78. [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, T.; Sørensen, A. M.; Tonboe, R.; et al. Global Sea Ice Concentration Climate Data Records, Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document. EUMETSAT OSI SAF: Oslo, Norway, 2022.

- Tschudi, M.; W. N. Meier; J. S. Stewart; C. Fowler; J. Maslanik. Polar Pathfinder Daily 25 km EASE-Grid Sea Ice Motion Vectors, Version 4.1. Boulder, Colorado USA, 2024. NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center. Available online: https://nsidc.org/data/nsidc-0116; (accessed on 17 October, 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quarterly journal of the royal meteorological society 2020, 146(730), 1999-2049. [CrossRef]

- Stern, H. L. Regime shift in Arctic Ocean sea-ice extent. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52(8), e2024GL114546. [CrossRef]

- Stroeve, J. C.; Notz, D. Changing state of Arctic sea ice across all seasons. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13(10), 103001. [CrossRef]

- England, M. R.; Polvani, L. M.; Screen, J.; Chan, A. C. Minimal Arctic sea ice loss in the last 20 years, consistent with internal climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52(15), e2025GL116175. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).