Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Biological Material

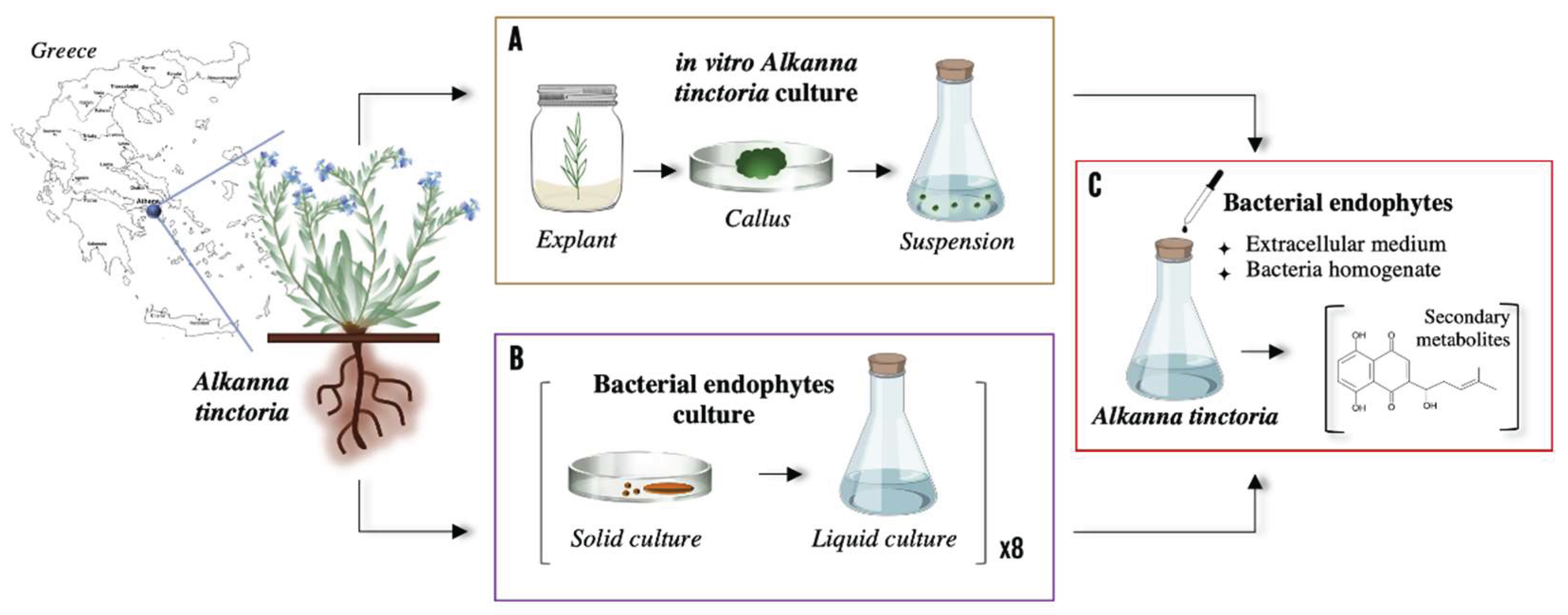

2.2.1. Alkanna Tinctoria Cells Suspension

2.2.2. Bacterial Endophytes

2.3. Co-Culture Experimental Set up

2.3.1. Preparation of Bacterial Endophyte Components

2.3.2. Co-culture Experiment

2.4. Extraction of Secondary Metabolites

2.5. UHPLC-HRMS Analysis

2.5.1. LC System & Chromatographic Conditions

2.5.2. High Resolution Mass Spectrometry Conditions

2.6. UHPLC-HRMS Data Processing

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

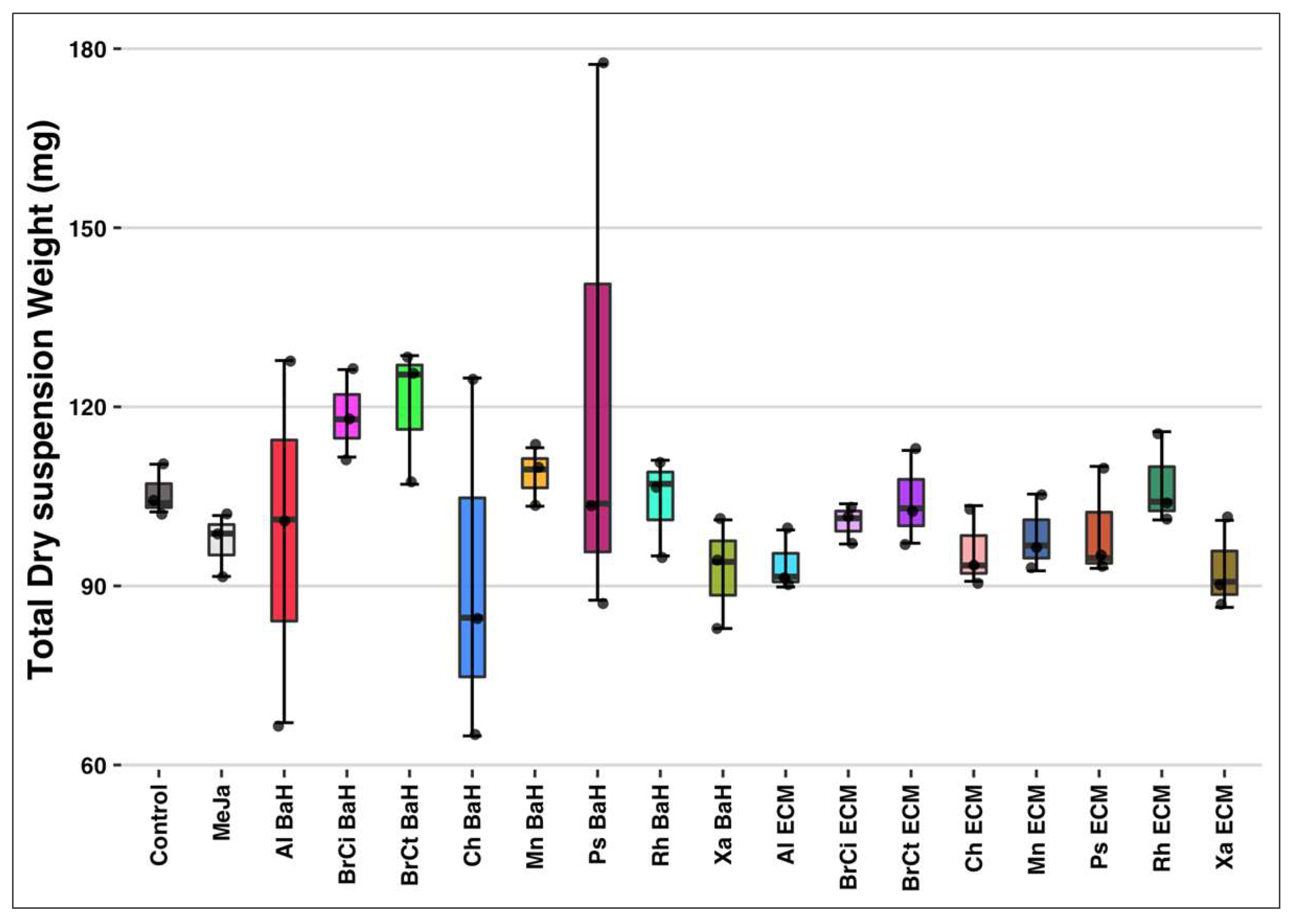

3.1. Total Suspension Dry Weight

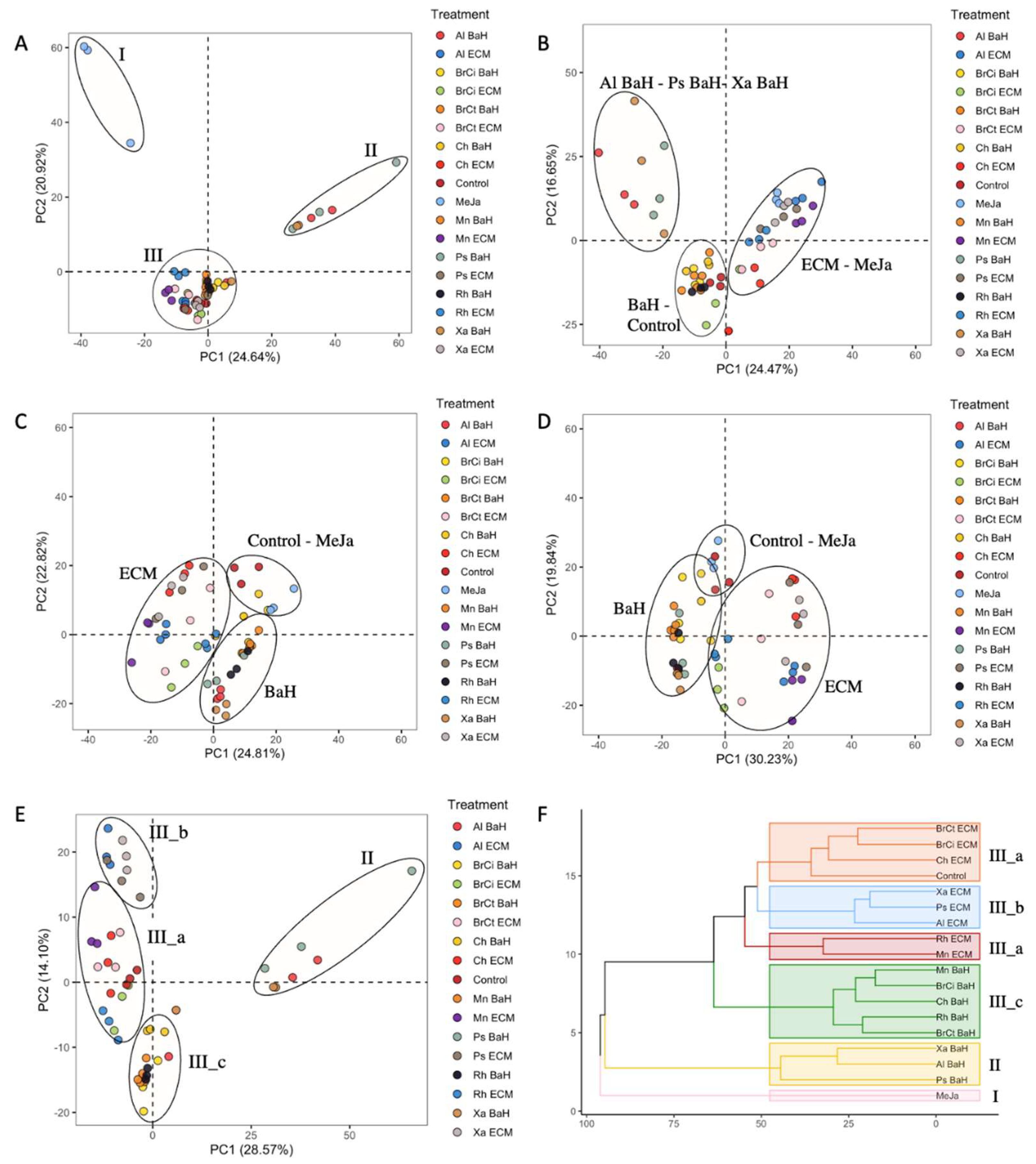

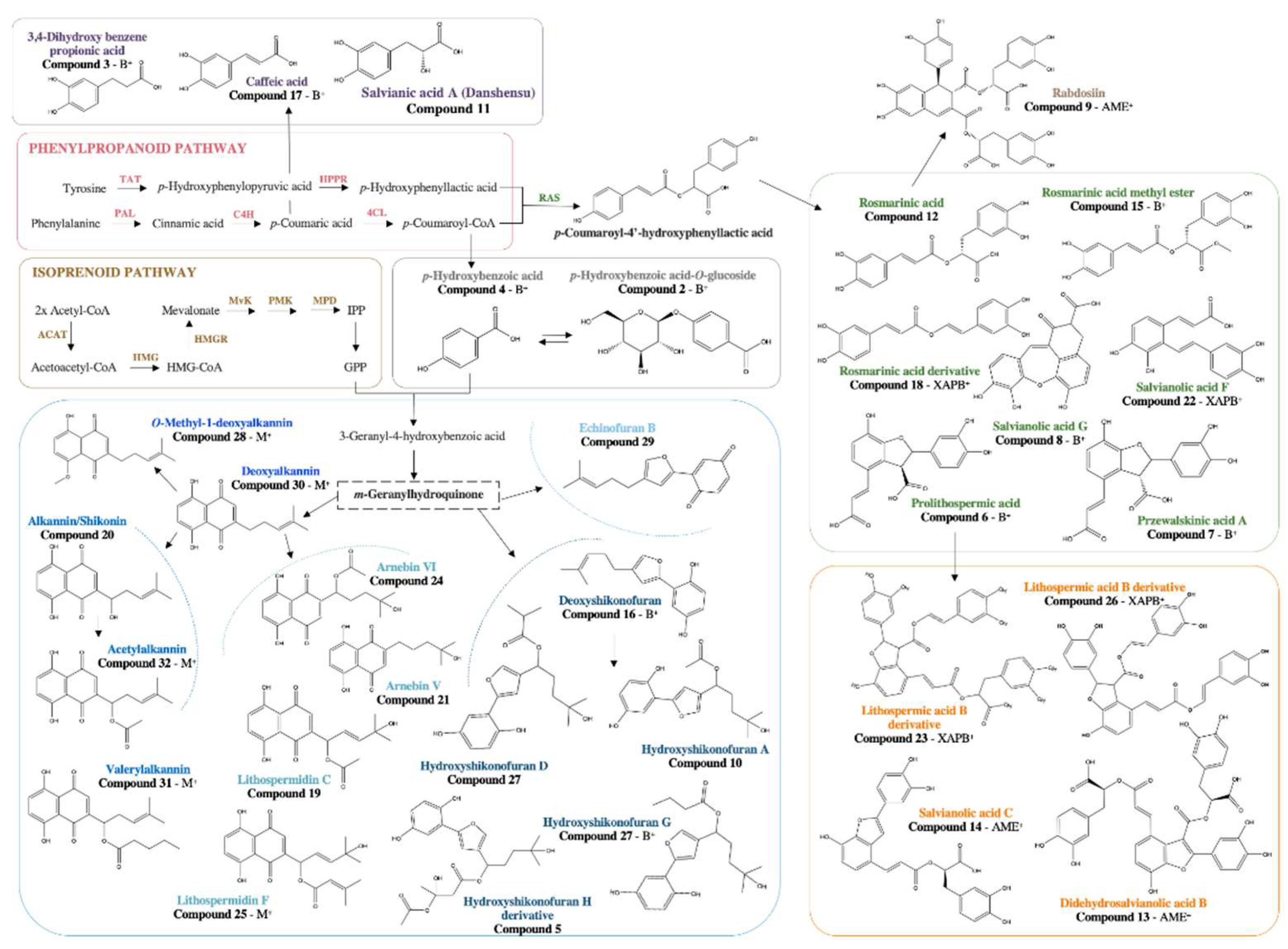

3.2. Alkanna Tinctoria Metabolome Analysis Using UHPL-HRMS Untargeted Metabolomics

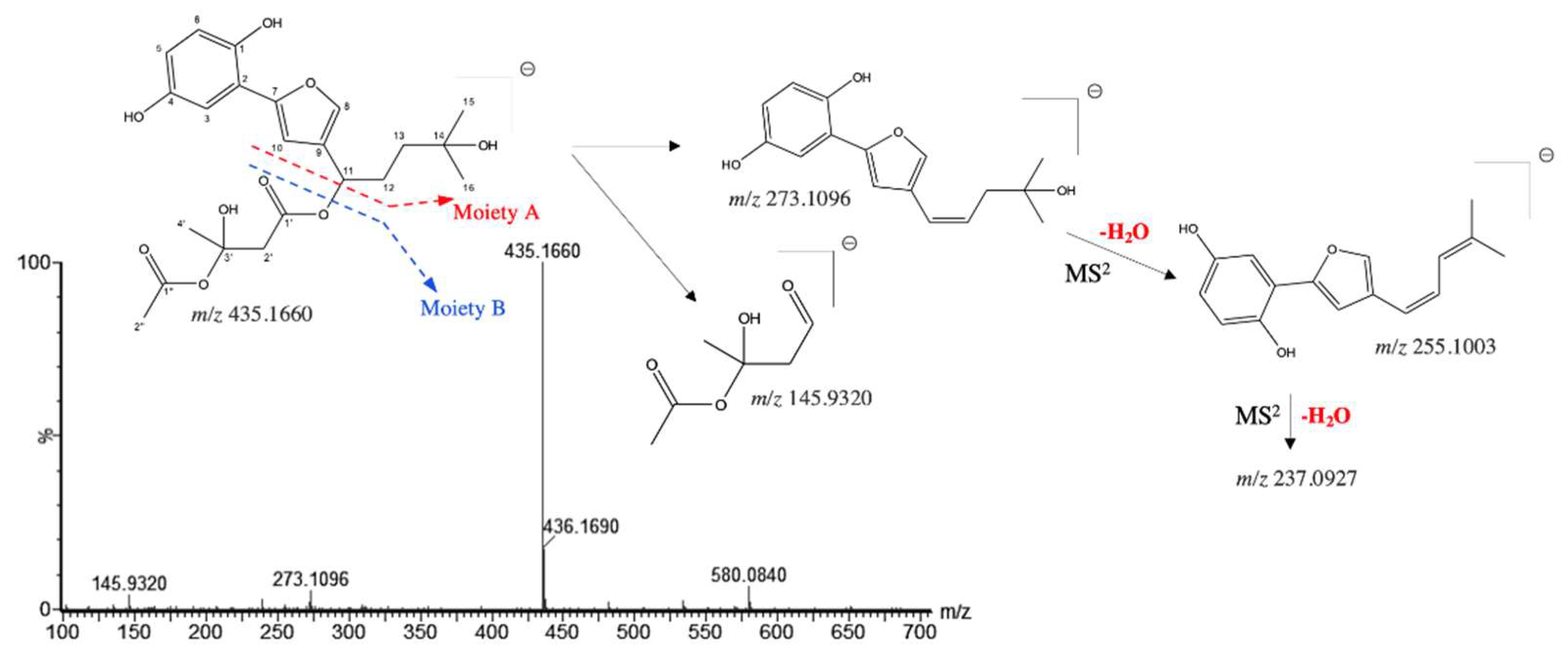

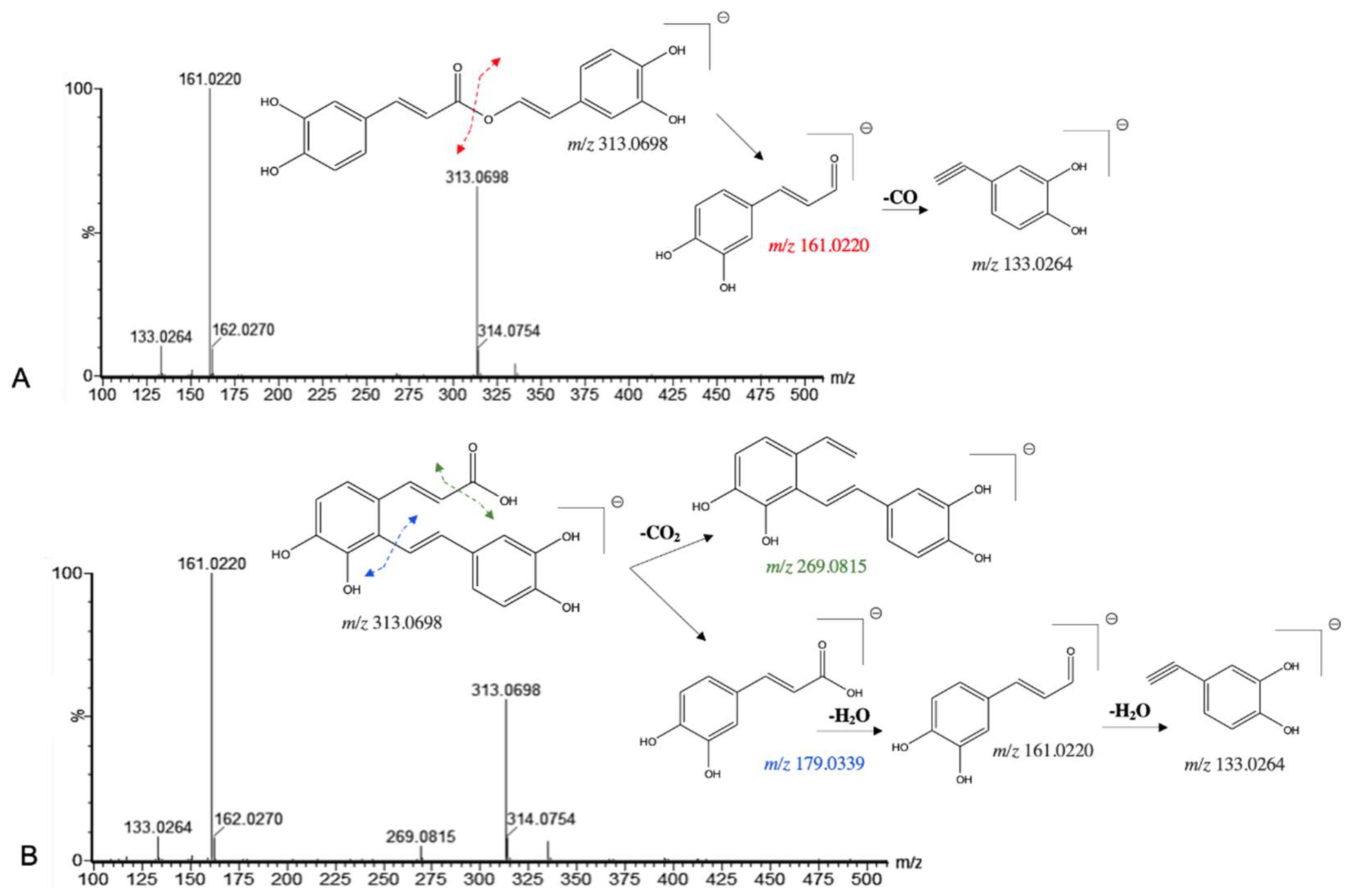

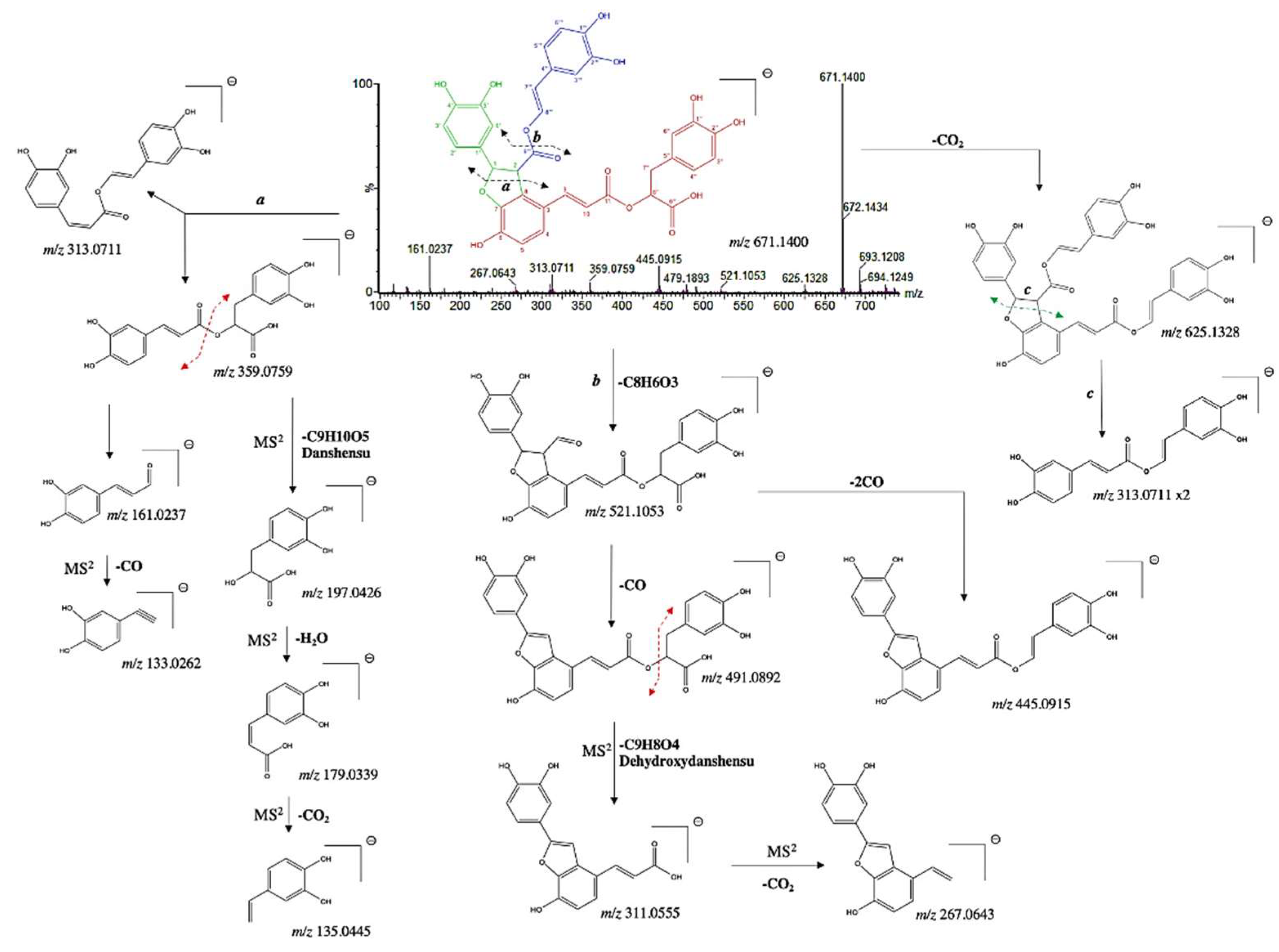

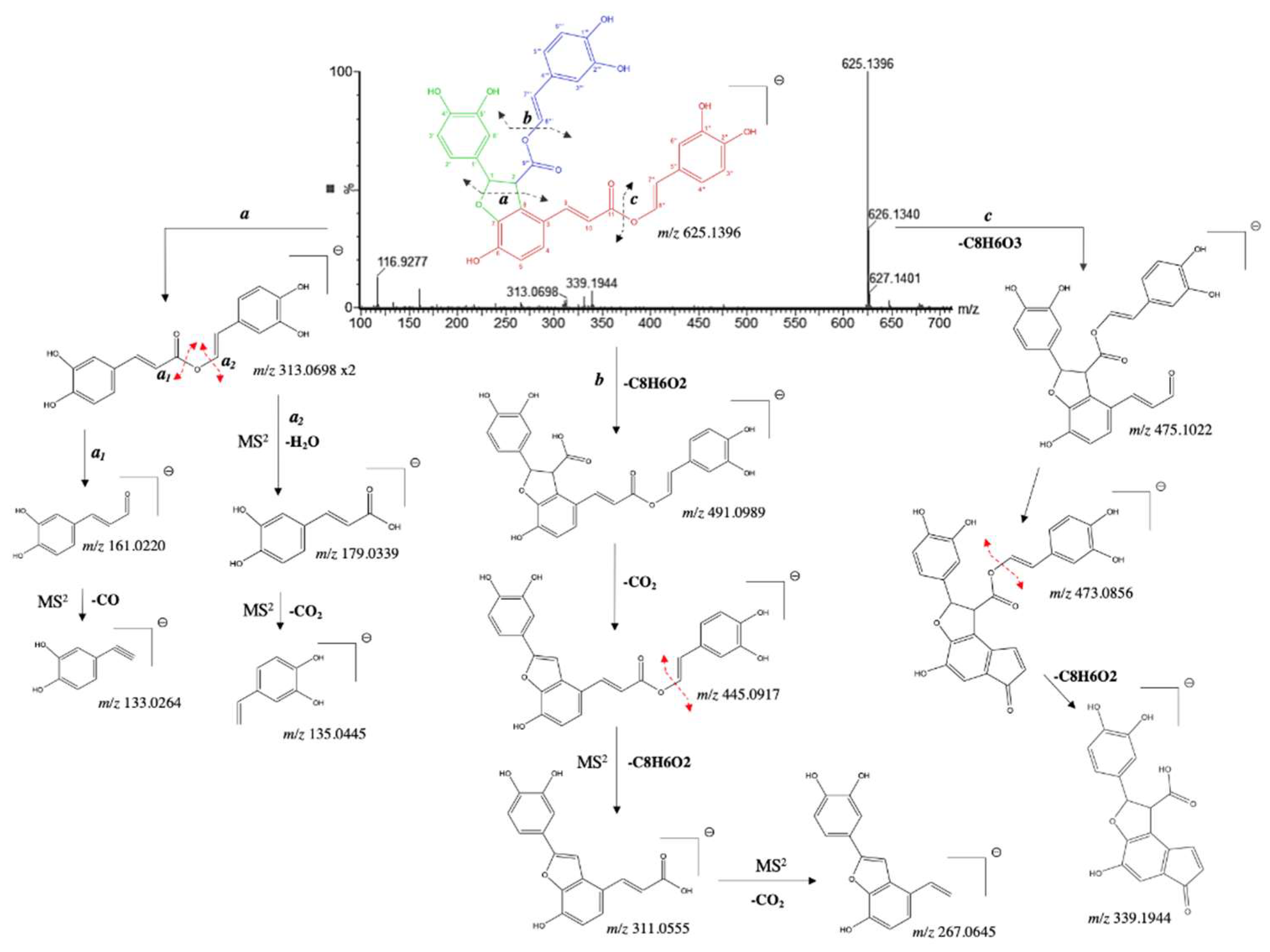

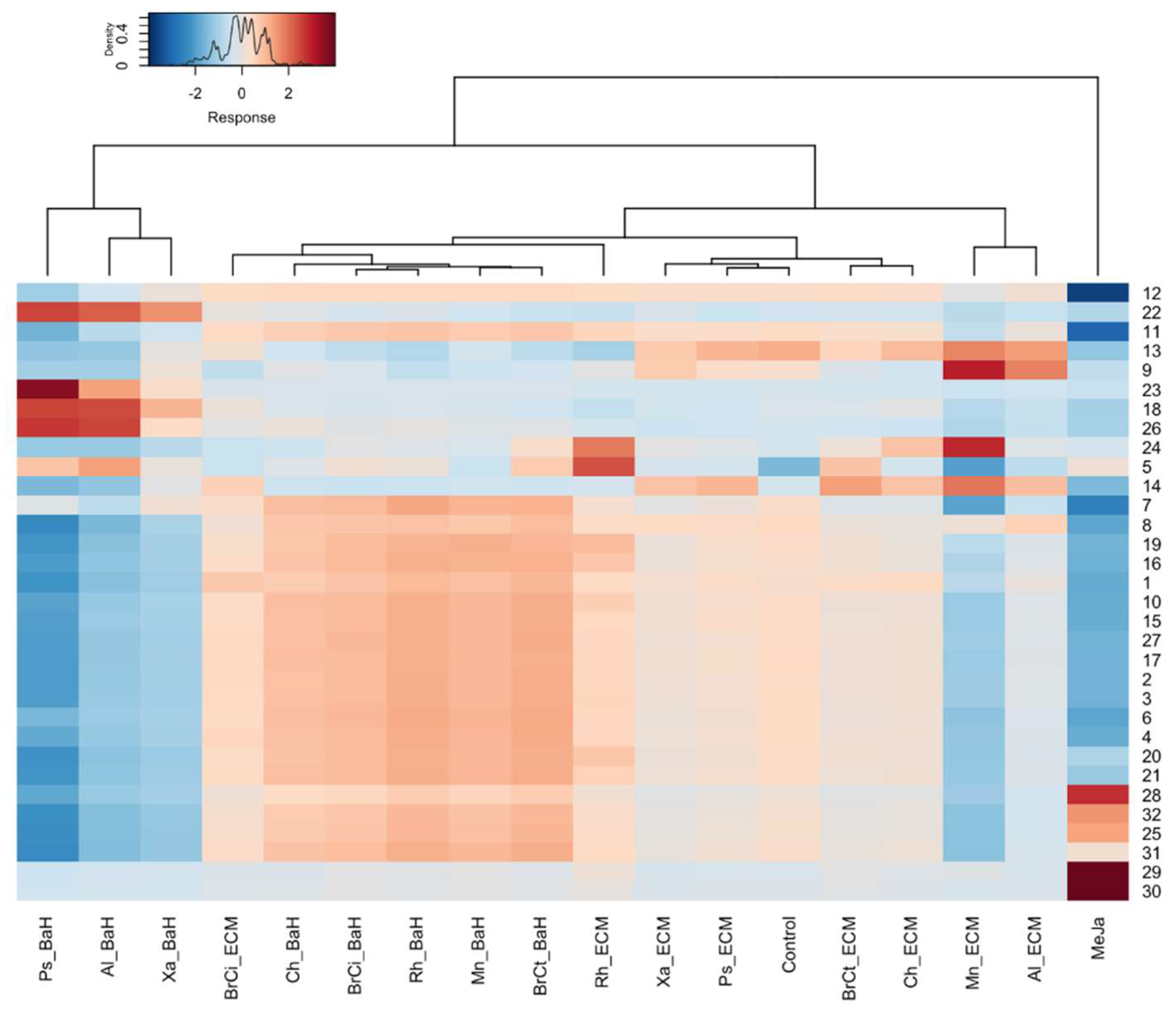

3.3. Putative Identification of Induced Secondary Metabolites

4. Discussion

4.1. Suitability of In Vitro Bacterial Endophyte-Plant co-Culture for the Production of Bioactive Secondary Metabolites

4.2. Impact of Bacterial Endophytes on Secondary Metabolism of Alkanna Tinctoria In Vitro Culture System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4CL | 4-courmaric acid coenzyme A-ligase |

| ACAT | Acetyl-CoA acetyl transferase |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| Al | Allorhizobium sp. |

| BaH | Biomass homogenate |

| BAP | 6-benzylaminopurine |

| BrCi | Brevibacillus sp. |

| BrCt | Brevibacterium sp. |

| C4M | Cinnamic acid-4-hydrolase |

| Ch | Chitinophaga sp. |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ECM | Bacterial endophyte culture supernatant |

| EtoAC | Ethyl acetate |

| EtOH abs | Ethanol absolute |

| HMGR | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoAsynthase |

| HNQ | Hydroxynaphthoquinones |

| HPPR | Hydroxyphenylpyruvate reductase |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| LC/MS | Liquid Chromatography / Mass Spectrometry |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| Mn | Micromonospora sp. |

| MPD | Mevalonate-PP decarboxylase |

| MS/MS | Mass Spectrometry/ Mass Spectrometry |

| MvK | Mevalonate kinase |

| PAL | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PMK | Phosphomevalonate kinase |

| Ps | Pseudomonas sp. |

| RAS | Rosmarinic acid synthase |

| Rh | Rhizobium sp. |

| SM | Secondary metabolite |

| T-DW | Total Suspension Dry Weight |

| TAT | Tyrosine aminotransferase |

| UHPLC-HRMS | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry |

| Xa | Xanthomonas sp. |

References

- Taulé, C.; Vaz-Jauri, P.; Battistoni, F. Insights into the Early Stages of Plant-Endophytic Bacteria Interaction. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2021, 37, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamkhi, I.; Benali, T.; Aanniz, T.; El Menyiy, N.; Guaouguaou, F.-E.; El Omari, N.; El-Shazly, M.; Zengin, G.; Bouyahya, A. Plant-Microbial Interaction: The Mechanism and the Application of Microbial Elicitor Induced Secondary Metabolites Biosynthesis in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 167, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compant, S.; Cambon, M.; Vacher, C.; Mitter, B.; Samad, A.; Sessitsch, A. The Plant Endosphere World – Bacterial Life within Plants. Environmental Microbiology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Chen, W.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Zhu, B. Beneficial Relationships Between Endophytic Bacteria and Medicinal Plants. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 646146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brader, G.; Compant, S.; Mitter, B.; Trognitz, F.; Sessitsch, A. Metabolic Potential of Endophytic Bacteria. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2014, 27, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, H.; Yin, Z.; Lian, M.; Yin, C. Endophytic Bacteria Isolated from Panax Ginseng Improves Ginsenoside Accumulation in Adventitious Ginseng Root Culture. Molecules 2017, 22, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankova-Tsvetkova, E.P.; Molle, E.D.; Stanilova, M.I.; Grigorova, I.D.; Traykova, B.D. Alkanna Tinctoria: An Approach toward Ex Situ Cultivation. Ecologia Balkanica 2020, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, V.P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Ballis, A.C. Alkannins and Shikonins: A New Class of Wound Healing Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 3248–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Sharma, M.; Meghwal, P.; Sahu, P.; Singh, S. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Shikonin Derivatives from Arnebia Hispidissima. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, N.; Petrosyan, M.; Trchounian, A. The Activity of Alkanna Species in Vitro Culture and Intact Plant Extracts against Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. Curr Pharm Des 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, J.; Sun, G.; Meng, Q.; Li, S. DMAKO-20 as a New Multitarget Anticancer Prodrug Activated by the Tumor Specific CYP1B1 Enzyme. Mol Pharm 2019, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankawa, U.; Ebizuka, Y.; Miyazaki, T.; Isomura, Y.; Otsuka, H. Antitumor Activity of Shikonin and Its Derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1977, 25, 2392–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhou, W.; Xiao, S.; Meng, Q.; Li, S. Antitumor Activity of DMAKO-05, a Novel Shikonin Derivative, and Its Metabolism in Rat Liver Microsome. AAPS. Pharm. Sci. Tech. 2015, 16, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Lim, L.; Loh, S.; Ying Lim, K.; Upton, Z.; Leavesley, D. Application of “Macromolecular Crowding” in Vitro to Investigate the Naphthoquinones Shikonin, Naphthazarin and Related Analogues for the Treatment of Dermal Scars. Chem Biolo Interact 2019, 310, 108747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rat, A.; Naranjo, H.D.; Krigas, N.; Grigoriadou, K.; Maloupa, E.; Alonso, A.V.; Schneider, C.; Papageorgiou, V.P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Tsafantakis, N.; et al. Endophytic Bacteria From the Roots of the Medicinal Plant Alkanna Tinctoria Tausch (Boraginaceae): Exploration of Plant Growth Promoting Properties and Potential Role in the Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 633488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-Y.; Ng, J.; Shi, M.; Wu, S.-J. Enhanced Secondary Metabolite (Tanshinone) Production of Salvia Miltiorrhiza Hairy Roots in a Novel Root-Bacteria Coculture Process. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2007, 77, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Le, S.; Mazet, J. FactoMineR: Multivariate Exploratory Data Analysis and Data Mining. 2020, R package version 2.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. 2021, R package version 3.3.

- Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2021, R package version 1. -3.

- Bertrand, S.; Bohni, N.; Schnee, S.; Schumpp, O.; Gindro, K.; Wolfender, J.-L. Metabolite Induction via Microorganism Co-Culture: A Potential Way to Enhance Chemical Diversity for Drug Discovery. Biotechnol Adv 2014, 32, 1180–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-T.; Murthy, H.N.; Park, S.-Y. Methyl Jasmonate Induced Oxidative Stress and Accumulation of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Cell and Organ Cultures. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartabia, A.; Tsiokanos, E.; Tsafantakis, N.; Lalaymia, I.; Termentzi, A.; Miguel, M.; Fokialakis, N.; Declerck, S. The Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungus Rhizophagus Irregularis MUCL 41833 Modulates Metabolites Production of Anchusa Officinalis L. Under Semi-Hydroponic Cultivation. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 724352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Q.; Dong, X.; Liu, X.-G.; Gao, W.; Li, P.; Yang, H. Rapid Separation and Identification of Multiple Constituents in Danhong Injection by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Electrospray Ionization Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Chin J Nat Med 2016, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Li, A.; Chen, C.; Ouyang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, H. Systematic Identification of Shikonins and Shikonofurans in Medicinal Zicao Species Using Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Quadrupole Time of Flight Tandem Mass Spectrometry Combined with a Data Mining Strategy. J Chromatogr A 2015, 1425, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibrom Gebreheiwot Bedane; Sebastian Zühlke; Michael Spiteller Bioactive Constituents of Lobostemon Fruticosus: Anti-Inflammatory Properties and Quantitative Analysis of Samples from Different Places in South Africa. South African journal of botany 2020, 131, 174–180. [CrossRef]

- Bodalska, A.; Kowalczyk, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Fecka, I. Analysis of Polyphenolic Composition of a Herbal Medicinal Product-Peppermint Tincture. Molecules 2019, 25, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Bai, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Qiu, X. Chemical Analysis and Multi-Component Determination in Chinese Medicine Preparation Bupi Yishen Formula Using Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography With Linear Ion Trap-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry and Triple-Quadrupole Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I.; Kuźma, Ł.; Lisiecki, P.; Kiss, A. Accumulation of Phenolic Compounds in Different in Vitro Cultures of Salvia Viridis L. and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential. Phytochemistry Letters 2019, 30, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.-H.; Guo, H.; Ye, M.; Lin, Y.-H.; Sun, J.-H.; Xu, M.; Guo, D.-A. Detection, Characterization and Identification of Phenolic Acids in Danshen Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection and Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 2007, 1161, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Bhushan, S.; Sharma, M.; Ahuja, P.S. Biotechnological Approaches to the Production of Shikonins: A Critical Review with Recent Updates. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2016, 36, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahjouri, S.; Movafeghi, A.; Zare, K.; Kosari-Nasab, M.; Nazemiyeh, H. Production of Naphthoquinone Derivatives Using Two-Liquid-Phase Suspension Cultures of Alkanna Orientalis. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2016, 1, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mita, G.; Gerardi, C.; Miceli, A.; Bollini, R.; De Leo, P. Pigment Production from in Vitro Cultures of Alkanna Tinctoria Tausch. Plant Cell Rep 1994, 13, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, C.; Uranbey, S.; Ahmed, H.A.; Özcan, S.; Tugay, O.; Başalma, D. Callus Induction and Regeneration of Alkanna Orientalis Var. Orientalis and A. Sieheana. Bangladesh Journal of Botany 2019, 48, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Varela Alonso, A.; Koletti, A.E.; Rodić, N.; Reichelt, M.; Rödel, P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Paun, O.; Declerck, S.; Schneider, C.; et al. Dynamics of Alkannin/Shikonin Biosynthesis in Response to Jasmonate and Salicylic Acid in Lithospermum Officinale. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 17093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanek, H.; Bergier, K.; Saniewski, M.; Patykowski, J. Effect of Jasmonates and Exogenous Polysaccharides on Production of Alkannin Pigments in Suspension Cultures of Alkanna Tinctoria. Plant Cell Rep 1996, 15, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela Alonso, A.; Naranjo, H.D.; Rat, A.; Rodić, N.; Nannou, C.I.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Declerck, S.; Rödel, P.; Schneider, C.; et al. Root-Associated Bacteria Modulate the Specialised Metabolome of Lithospermum Officinale L. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, M. Rosmarinic Acid: New Aspects. Phytochemistry Reviews 2013, 12, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Phylum | Bacterial Genus | Strain | Bacterial Material Plant Modulator Type | Concentration | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroidota | Chitinophaga sp.* | R-73072 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Ch BaH |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Ch ECM | |||

| Pseudomonadota (class Gammaproteobacteria) | Xanthomonas sp.* | R-73098 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Xa BaH |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Xa ECM | |||

| Pseudomonas sp.* | R-71838 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Ps BaH | |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Ps ECM | |||

| Actinomycetota | Micromonospora sp.* | R-75348 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Mn BaH |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Mn ECM | |||

| Pseudomonadota (class Alphaproteobacteria | Allorhizobium sp.* | R-72379 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Al BaH |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Al ECM | |||

| Rhizobium sp. | R-72160 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | Rh BaH | |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | Rh ECM | |||

| Bacillota | Brevibacillus sp. | R-71971 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | BrCi BaH |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | BrCi ECM | |||

| Brevibacterium sp. | R-71875 | Bacteria Homogenate | 0.04% | BrCt BaH | |

| Extracellular medium | 4% | BrCt ECM |

| No°#break# | Rt (min) | Proposed Phytochemicals | Precursor ion [M-H]- | m/z Calcd. | Mass Error (ppm) | Chemical Formula | MS/MS Fragment ions m/z | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.434 | Gluconic acid | 195.0503 | 195.0505 | -1.0 | C6H12O7 | 177.0793, 160.8910, 129.0183 | [22] |

| 2 | 0.547 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid-O-glucoside | 299.0758 | 299.0767 | -3.0 | C13H16O8 | 137.0228 | [23] |

| 3 | 0.890 | 3,4-dihydroxy benzene propionic acid | 181.0490 | 181.0501 | -6.1 | C9H10O4 | 162.9812, 134.9859, 117.9341 | [23] |

| 4 | 1.053 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 137.0247 | 137.0239 | 5.8 | C7H6O3 | 134.9865 | [22] |

| 5 | 1.830 | 3'-hydroxy-14-hydroxyshikonofuran H* | 435.1660 | 435.1655 | 1.1 | C22H28O9 | 273.1096, 255.1003, 145.9320 | [24] |

| 6 | 2.194 | Prolithospermic acid | 357.0609 | 357.0610 | -0.3 | C18H14O8 | 313.0686, 269.8307, 159.8919 | [23] |

| 7 | 2.344 | Przewalskinic acid A | 357.0595 | 357.0610 | -4.2 | C18H14O8 | 313.0686, 269.0803, 178.9772 | [23] |

| 8 | 3.377 | Salvianolic acid G | 339.0506 | 339.0505 | 0.3 | C18H12O7 | 321.0781, 295.0620, 280.8622 | [23] |

| 9 | 3.378 | Rabdosiin | 717.1457 | 717.1456 | 0.1 | C36H30O16 | 537.1082, 519.0881, 475.1022, 339.0496 | [25] |

| 10 | 3.405 | Hydroxyshikinofuran A | 333.1325 | 333.1338 | -3.9 | C18H22O6 | 273.1096, 255.0654 | [24] |

| 11 | 3.663 | Salvianic acid A | 197.0449 | 197.0450 | -0.5 | C9H10O5 | 179.0340 ,135.0443, 123.0437 | [23] |

| 12 | 3.663 | Rosmarinic acid | 359.0774 | 359.0767 | 1.9 | C18H16O8 | 197.0448, 179.0340, 161.0240, 133.0288 | [23] |

| 13 | 3.834 | Didehydrosalvianolic acid B | 715.1301 | 715.1299 | 0.3 | C36H28O16 | 337.0334, 319.1210, 293.8187 | [26] |

| 14 | 4.034 | Salvianolic acid C | 491.0968 | 491.0978 | -2.0 | C26H20O10 | 311.0545, 293.8111, 267.0631, 231.8548 | [23] |

| 15 | 4.090 | Rosmarinic acid methyl ester | 373.0919 | 373.0923 | -1.1 | C19H18O8 | 179.0339, 135.0445 | [23] |

| 16 | 4.298 | Deoxyshikonofuran | 257.1169 | 257.1178 | -3.5 | C16H18O3 | 173.0292, 159.8986, 116.9277 | [24] |

| 17 | 4.325 | Caffeic acid | 179.0345 | 179.0344 | 0.6 | C9H8O4 | 135.8987 | [23] |

| 18 | 4.468 | 8'-decarboxy-rosmarinic acid* | 313.0698 | 313.0712 | -4.5 | C17H14O6 | 179.0334, 161.0240, 133.0286, 123.0416 | [27] |

| 19 | 4.518 | Lithospermidin C | 345.0980 | 345.0974 | 1.7 | C18H18O7 | 285.0727, 267.0626, 257.1180, 249.1110, 238.8891, 227.0691 | [24] |

| 20 | 4.589 | Alkannin/Shikonin | 287.0915 | 287.0919 | -1.4 | C16H16O5 | 218.8601, 190.9279, 189.9296, 173.0238, 161.0230 | [24] |

| 21 | 4.625 | Arnebin V | 289.1090 | 289.1076 | 4.8 | C16H18O5 | 245.1179, 179.0702, 151.0398 | [24] |

| 22 | 4.654 | Salvianolic acid F | 313.0698 | 313.0712 | -4.5 | C17H14O6 | 269.0815, 203.0359, 161.0220, 133.0264, 123.0429 | [28] |

| 23 | 4.803 | 8'''-decarboxy-salvianolic B* | 671.1400 | 671.1401 | -0.1 | C35H28O14 | 625.1328, 563.0319, 521.1053, 491.0969, 359.0759, 313.0711, 267.0643, 179.0338, 161.0237 | [29] |

| 24 | 4.853 | Arnebin VI | 347.1132 | 347.1131 | 0.3 | C18H20O7 | 288.0997, 181.0493, 151.0395 | [24] |

| 25 | 5.052 | Lithospermidin F | 385.1277 | 385.1287 | -2.6 | C21H22O7 | 303.1212, 267.0644, 257.1188, 238.8907 | [24] |

| 26 | 5.352 | 8''-8'''-didecarboxy-salvianolic acid B* | 625.1343 | 625.1346 | -0.5 | C34H26O12 | 339.1976, 313.0691, 238.8904, 149.0232, 133.0278, 116.9272 | [29] |

| 27 | 5.458 | Hydroxyshikonofuran D/G | 361.1636 | 361.1551 | -4.2 | C20H26O6 | 273.1121, 255.0974, 237.1086, 174.8651 | [24] |

| 28 | 5.765 | O-Methyl-1'-deoxyalkannin | 285.1118 | 285.1127 | -3.2 | C17H18O4 | 267.1491, 217.8558, 189.8500 | [24] |

| 29 | 5.808 | Echinofuran B | 255.1013 | 255.1021 | -3.1 | C16H16O3 | 173.0234, 159.0435, 116.9277, 100.9343 | [24] |

| 30 | 5.815 | Deoxyalkannin (Arnebin VII) | 271.0972 | 271.0970 | 0.7 | C16H16O4 | 238.8911, 202.0260, 175.8447, 174.8634 | [24] |

| 31 | 6.107 | Valerylshikonin | 371.1488 | 371.1495 | -1.9 | C21H24O6 | 271.0966, 241.0714, 225.7941, 100.9306 | [24] |

| 32 | 6.357 | Acetylalkannin | 329.1003 | 329.1025 | -6.7 | C18H18O6 | 271.0941, 241.0745, 225.7967, 223.7977 | [24] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).