Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

29 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experiment Location

2.2. Obtaining and Cultivating Isolates of Metarhizium Anisopliae

2.3. Insecticides Used and Concentrations Tested

2.4. Preparing Culture Media with Insecticides

2.5. Evaluation of Mycelial Growth

2.6. Evaluation of Conidia Production

2.7. Evaluation of Conidia Germination

2.8. Biological Index (BI) - Fungicide Compatibility

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Insecticides on Germination

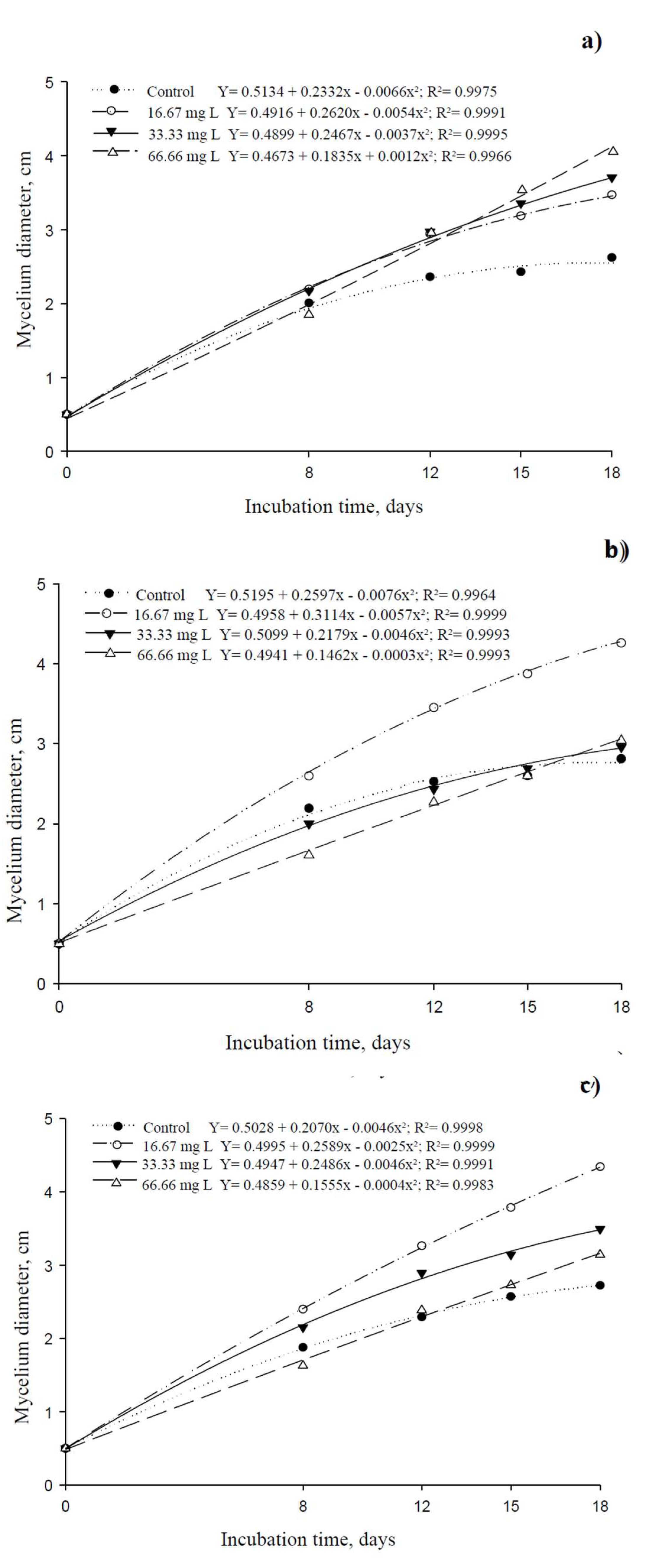

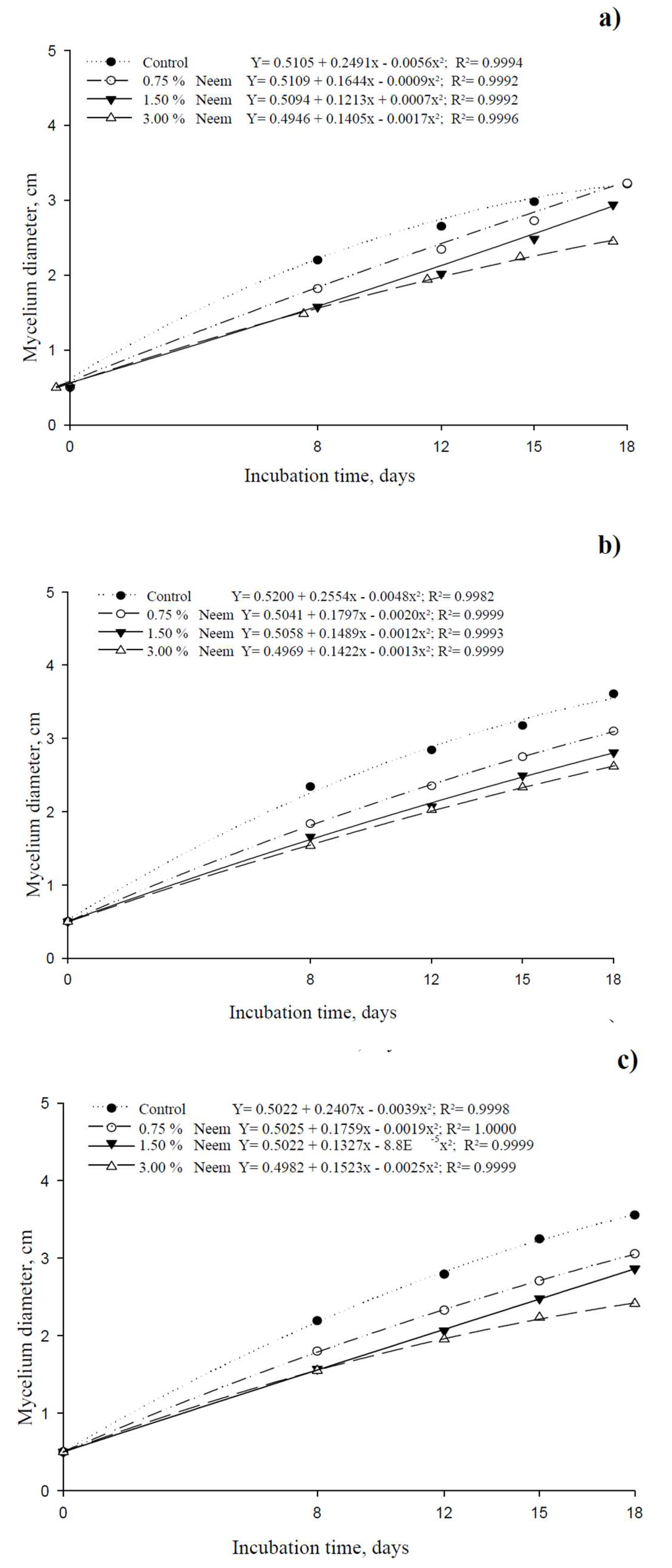

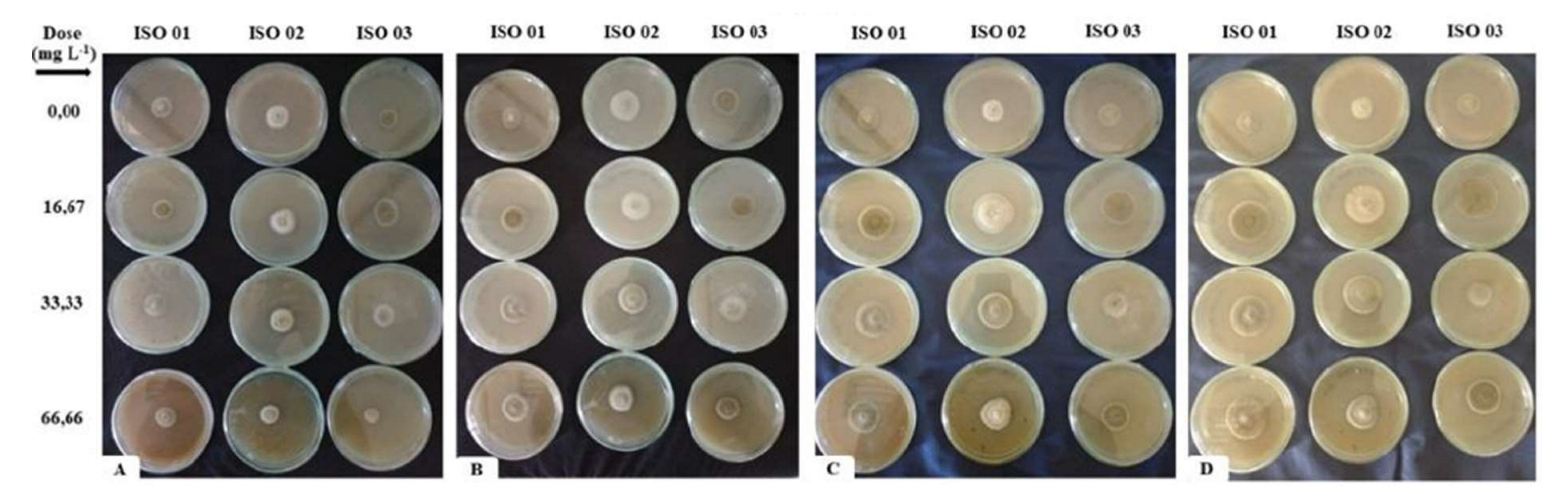

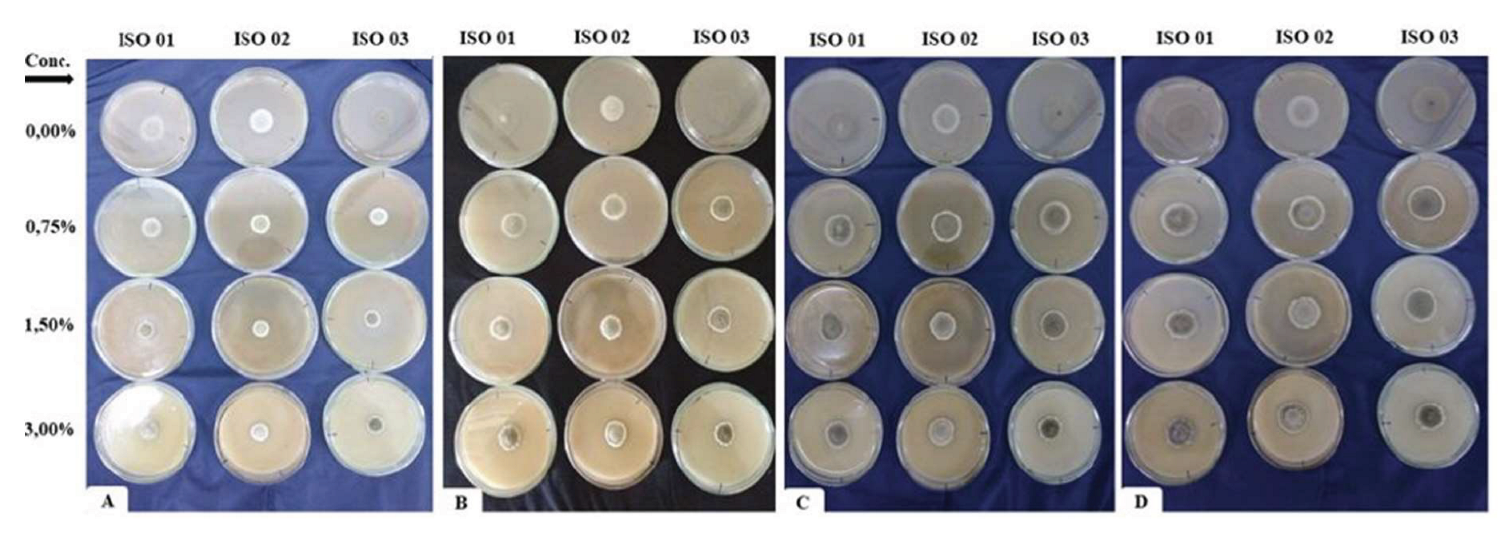

3.2. Effect of Insecticides on Vegetative Growth

3.3. Effect of Insecticides on Sporulation

3.4. Compatibility Based on the Biological Index (BI)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nanini:, F.; Souza, P.G.C.; Soliman, E.P.; Zauza, E.A.V.; Domingues, M.M.; Santos, F.A.; Wilcken, C.F.; da Silva, R.S.; Corrêa, A.S. Genetic Diversity, Population Structure and Ecological Niche Modeling of Thyrinteina Arnobia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae), a Native Eucalyptus Pest in Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende-Teixeira, P.; Dusi, R.G.; Jimenez, P.C.; Espindola, L.S.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V. What Can We Learn from Commercial Insecticides: Efficacy, Toxicity, Environmental Impacts, and Future Developments. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 300, 118983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo, S. da S.; Soares, M.A.; Zanuncio, J.C.; Leite, G.L.D.; Pires, E.M.; Cruz, M. do C.M. da Host Plants of Thyrinteina arnobia (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) affect the development of parasitoids Palmistichus elaeisis (Humenoptera: Eulophidae). Rev. Árvore 2015, 39, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.O.; Abreu, J.A.; Christ, L.M.; Rosa, A.P.S.A. Efficacy of Insecticides against Spodoptera Frugiperda (Smith, 1797). 2019, 11, 494–503. 11.

- Gandini, E.M.M.; Costa, E.S.P.; Dos Santos, J.B.; Soares, M.A.; Barroso, G.M.; Corrêa, J.M.; Carvalho, A.G.; Zanuncio, J.C. Compatibility of Pesticides and/or Fertilizers in Tank Mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, M. Integrated Pest Management: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Developments. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, A.L.; Sylvestre, M.; Tölke, E.D.; Tavares, J.F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G. Plant-Derived Pesticides as an Alternative to Pest Management and Sustainable Agricultural Production: Prospects, Applications and Challenges. Molecules 2021, 26, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, O.C.; Pomari-Fernandes, A.; Bueno, R.C.O.D.F.; Bueno, A.D.F.; Cruz, Y.K.S.D.; Sanzovo, A.; Ferreira, R.B. The use of Soybean Integrated Pest Management in Brazil: A Review. Agron. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 1, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.R.B.D.; Farias, J.R.; Bernardi, D.; Horikoshi, R.J.; Omoto, C. Genetic Basis of Spodoptera Frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Resistance to the Chitin Synthesis Inhibitor Lufenuron. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022.

- Suarez-Lopez, Y.A.; Aldebis, H.K.; Hatem, A.E.-S.; Vargas-Osuna, E. Interactions of Entomopathogens with Insect Growth Regulators for the Control of Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Biol. Control 2022, 170, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuncio, J.C.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Cruz, A.P. da; Moreira, A.M. Eficiência de Bacillus thuringiensis e de Deltametrina, em aplicação aérea, para o controle de Thyrinteina arnobia STOLL, 1782 (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) em Eucaliptal no Pará. Acta Amaz. 1992, 22, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velíšek, J.; Jurčíková, J.; Dobšíková, R.; Svobodová, Z.; Piačková, V.; Máchová, J.; Novotný, L. Effects of Deltamethrin on Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 23, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cycoń, M.; Żmijowska, A.; Piotrowska-Seget, Z. Enhancement of Deltamethrin Degradation by Soil Bioaugmentation with Two Different Strains of Serratia marcescens. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Xun, H.; Sun, J.; Tang, F. Comparative Analysis of the Terpenoid Biosynthesis Pathway in Azadirachta indica and Melia azedarach by RNA-Seq. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S. Progress on Azadirachta indica Based Biopesticides in Replacing Synthetic Toxic Pesticides. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuncio, J.C.; Mourão, S.A.; Martínez, L.C.; Wilcken, C.F.; Ramalho, F.S.; Plata-Rueda, A.; Soares, M.A.; Serrão, J.E. Toxic Effects of the Neem Oil (Azadirachta indica) Formulation on the Stink Bug Predator, Podisus nigrispinus (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesena, N.; Schneider, M.I. Selectivity Assessment of Two Biorational Insecticides, Azadirachtin and Pyriproxyfen, in Comparison to a Neonicotinoid, Acetamiprid, on Pupae and Adults of a Neotropical Strain Eretmocerus mundus Mercet. Chemosphere 2018, 206, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannag, H.K.; Capinera, J.L.; Freihat, N.M. Effects of Neem-Based Insecticides on Consumption and Utilization of Food in Larvae of Spodoptera Eridania (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Insect Sci. 2015, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, K. Impact of extracts of Azadirachta indica and Datura inoxia on the esterases and phosphatases of three stored grains insect pests of economic importance. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 54, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, Md.A.; Song, J.; Lim, U.T.; Choi, J.J.; Hossain, Md.A. Bioassay of Plant Extracts Against Aleurodicus Dispersus (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae). Fla. Entomol. 2017, 100, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, L.A.N.D.; Pessoa, M.C.P.Y.; Moraes, G.J.D.; Marinho-Prado, J.S.; Prado, S.D.S.; Vasconcelos, R.M.D. Quarantine Facilities and Legal Issues of the Use of Biocontrol Agents in Brazil. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2016, 51, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.R.; Paixão, M.A.S.D.; Cruz, I. Viabilidade Econômica de Biofábrica de Trichogramma pretiosum Para Uso Contra Pragas Agrícolas Da Ordem Lepidoptera. Rev. IPecege 2018, 4, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, F.; Jacquemyn, H.; Delvigne, F.; Lievens, B. From Diverse Origins to Specific Targets: Role of Microorganisms in Indirect Pest Biological Control. Insects 2020, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettiol, W. Pesquisa, desenvolvimento e inovação com bioinsumos. In Bioinsumo na Cultura da Soja; Embrapa: Brasília - DF - Brazil, 2022; ISBN 978-65-87380-96-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, A.; Rao, Q.; Bakhsh, A.; Husnain, T. Entomopathogenic Fungi as Biological Controllers: New Insights into Their Virulence and Pathogenicity. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2012, 64, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.Y.; Bae, S.M.; Woo, S.D. Screening and Characterization of Antimicrobial Substances Originated from Entomopathogenic Fungi. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2016, 19, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubeen, N.; Khalid, A.; Ullah, M.I.; Altaf, N.; Arshad, M.; Amin, L.; Talat, Q.; Sadaf, A.; Farwa Effect of Metarhizium anisopliae on the Nutritional Physiology of the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2022, 32, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Frutos, R.; Brownbridge, M.; Goettel, M.S. Insect Pathogens as Biological Control Agents: Back to the Future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deka, B.; Baruah, C.; Babu, A. Entomopathogenic Microorganisms: Their Role in Insect Pest Management. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2021, 31, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biological Control in Latin America and the Caribbean: Its Rich History and Bright Future; Bueno, V. H.P., Luna, M.G., Colmenarez, Y.C., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78924-243-0. [Google Scholar]

- Potrich, M.; Alves, L.F.A.; Haas, J.; Silva, E.R.L.D.; Daros, A.; Pietrowski, V.; Neves, P.M.O.J. Seletividade de Beauveria bassiana e Metarhizium anisopliae a Trichogramma pretiosum Riley (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2009, 38, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, A.F.; Ekowati, N.; Ratnaningtyas, N.I. Compatibility of insecticides with entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. Scr. Biol. 2017, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.P.; Pessoa, L.G.A.; Loureiro, E.D.S.; Oliveira, M.P. Compatibility of insecticides used for the whitefly control on soybean with Beauveria bassiana. Rev. Agric. NEOTROPICAL 2018, 5, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, F.N.; Pratissoli, D.; Santos Junior, H.J.G.; Costa, A.V.; Bestete, L.R.; Borges Filho, R.C. Compatibilidade in Vitro Entre Beauveria bassiana e o Óleo de Mamona. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Agrár. - Braz. J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, J.; Kushwaha, D.; Rai, A.B.; Singh, B. Interaction Effects between Entomopathogenic Fungi and Neonicotinoid Insecticides against Lipaphis erysimi in Vegetable Ecosystem. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.B. Controle Microbiano de Insetos; 2nd, *!!! REPLACE !!!* (Eds.) P: Sérgio Batista Alves: FEALQ, 1998.

- Neves, P.M.O.J.; Hirose, E.; Tchujo, P.T.; Moino Jr, A. Compatibility of Entomopathogenic Fungi with Neonicotinoid Insecticides. Neotrop. Entomol. 2001, 30, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, C.; Fargues, J. Temperature and Moisture Requirements for Conidial Germination of an Isolate of Beauveria bassiana, Pathogenic to Rhodnius Prolixus. Mycopathologia 1997, 138, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi-Zalaf, L.; Alves, S.; Lopes, R.; Silveira Neto, S.; Tanzini, M. Interação de Microrganismos Com Outros Agentes de Controle de Pragas e Doenças. Controle Microbiano Pragas Na América Lat. Avanços E Desafios 2008, 2, 270–302. [Google Scholar]

- SAEG Sistema Para Análises Estatísticas 2007.

- Shang, H.; He, D.; Li, B.; Chen, X.; Luo, K.; Li, G. Environmentally Friendly and Effective Alternative Approaches to Pest Management: Recent Advances and Challenges. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parjane, N.; Kabre, G.; Mahale, A.; Shejale, B.; Nirgude, S. Compatibility of Pesticides with Metarhizium anisopliae. J Entomol Zool Stud 2020, 8, 633–636. [Google Scholar]

- Atrchian, H.; Mahdian, K. Compatibility of Metarhizium anisopliae (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) with Selective Insecticides against Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 3009–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Razzaq, F.; Razzaq, A.; Gogi, M.D.; Fernández-Grandon, G.M.; Tayib, M.; Ayub, M.A.; Sufyan, M.; Shahid, M.R.; Qayyum, M.A.; et al. Compatibility and Synergistic Interactions of Fungi, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Insecticide Combinations against the Cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Band, S.; Kabre, G.; Dhurve, N. Effect of Chemical Pesticides on Growth Characteristics of Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschnikoff) Sorokin. Int. J. Adv. Biochem. Res. 2024, 8, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khun, K.K.; Ash, G.J.; Stevens, M.M.; Huwer, R.K.; Wilson, B.A. Compatibility of Metarhizium Anisopliae and Beauveria Bassiana with Insecticides and Fungicides Used in Macadamia Production in Australia. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, V.; Poehling, H.-M. In Vitro Effect of Pesticides on the Germination, Vegetative Growth, and Conidial Production of Two Strains of Metarhizium anisopliae. Fungal Biol. 2012, 116, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holka, M.; Kowalska, J. The Potential of Adjuvants Used with Microbiological Control of Insect Pests with Emphasis on Organic Farming. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Jaronski, S.T. The Production and Uses of Beauveria bassiana as a Microbial Insecticide. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzoukas, S.; Kitsiou, F.; Natsiopoulos, D.; Eliopoulos, P.A. Entomopathogenic Fungi: Interactions and Applications. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.C.; Reddy, N.P.; Devi, U.K.; Kongara, R.; Sharma, H.C. Growth and Insect Assays of Beauveria bassiana with Neem to Test Their Compatibility and Synergism. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sain, S.K.; Monga, D.; Kumar, R.; Nagrale, D.T.; Hiremani, N.S.; Kranthi, S. Compatibility of Entomopathogenic Fungi with Insecticides and Their Efficacy for IPM of Bemisia Tabaci in Cotton. J. Pestic. Sci. 2019, 44, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tixier, C.; Bogaerts, P.; Sancelme, M.; Bonnemoy, F.; Twagilimana, L.; Cuer, A.; Bohatier, J.; Veschambre, H. Fungal Biodegradation of a Phenylurea Herbicide, Diuron: Structure and Toxicity of Metabolites. Pest Manag. Sci. 2000, 56, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, M.A.; Alves, S.B.; Lopes, R.B.; Faion, M.; Padulla, L.F.L. Toxicity of pesticides against Baeuveria bassiana (BALS.) VUILL. Arq. Inst. Biológico 2002, 69, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yada, G.M.; Shiraishi, I.S.; Dekker, R.F.H.; Schirmann, J.G.; Barbosa-Dekker, A.M.; De Araujo, I.C.; Abreu, L.M.; Daniel, J.F.S. Soil and Entomopathogenic Fungi with Potential for Biodegradation of Insecticides: Degradation of Flubendiamide in Vivo by Fungi and in Vitro by Laccase. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Á.B. da; Brandão da Silva, T.F.; Coimbra dos Santos, A.; Mesquita Paiva, L.; Luna-Alves Lima, E.Á. Fungitoxic effect of neem oil on Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum and Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae. 2009, 22, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose, E.; Neves, P.M.O.J.; Zequi, J.A.C.; Martins, L.H.; Peralta, C.H.; Moino Jr., A. Effect of Biofertilizers and Neem Oil on the Entomopathogenic Fungi Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. and Metarhizium anisopliae (Metsch.) Sorok. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2001, 44, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depieri, R.A.; Martinez, S.S.; Menezes Jr., A. O. Compatibility of the Fungus Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. (Deuteromycetes) with Extracts of Neem Seeds and Leaves and the Emulsible Oil. Neotrop. Entomol. 2005, 34, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.P.; Monteiro, A.C.; Pereira, G.T. Crescimento, Esporulação e Viabilidade de Fungos Entomopatogênicos Em Meios Contendo Diferentes Concentrações Do Óleo de Nim (Azadirachta indica). Ciênc. Rural 2004, 34, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregonesi, A.F.; Mochi, D.A.; Monteiro, A.C. Compatibilidade de Isolados de Beauveria bassiana a Inseticidas, Herbicidas e Maturadores Em Condições de Laboratório. Arq. Inst. Biológico 2016, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.M.; Marques, E.J.; Oliveira, J.V.D.; Alves, S.B. Selection of isolates of entomopathogenic fungi for controlling Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) and their compatibility with insecticides used in tomato crop. Neotrop. Entomol. 2010, 39, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.A.D.; Quintela, E.D.; Mascarin, G.M.; Barrigossi, J.A.F.; Lião, L.M. Compatibility of Conventional Agrochemicals Used in Rice Crops with the Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Sci. Agric. 2013, 70, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damin, S.; Vilani, A.; De Freitas, D.; Krasburg, C.; Alves De Queiroz, J.; Yumi Kagimura, F.; Becker Onofre, S. Ação de Fungicidas Sobre o Crescimento Do Fungo Entomopatogênico Metarhizium Sp. Rev. Acadêmica Ciênc. Anim. 2011, 9, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo Jr, J.M.D.; Marques, E.J.; Oliveira, J.V.D. Potencial de Isolados de Metarhizium anisopliae e Beauveria bassiana e Do Óleo de Nim No Controle Do Pulgão Lipaphis erysimi (Kalt.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2009, 38, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Insecticide |

Dose/ Conc. |

ISO 01 | ISO 02 | ISO 03 | ||||||

| Vegetative growth (cm) |

Sporulation 106 cnds mL |

Germination (%) |

Vegetative growth (cm) |

Sporulation 106 cnds mL |

Germination (%) |

Vegetative growth (cm) |

Sporulation 106 cnds mL |

Germination (%) |

||

|

Deltamethrin (mg L-1) |

Control | 2.62bA | 18.24aA | 83.35abA | 2.81bA | 1.76aB | 72.44aA | 2.73bA | 21.92aA | 86.87aA |

| 16.67 | 3.47abA | 28.00aA | 88.62aA | 4.26aA | 3.60aB | 78.45aA | 4.34aA | 23.52aA | 73.51aA | |

| 33.33 | 3.71abA | 16.16aA | 85.12abA | 2.96bA | 8.00aA | 86.07aA | 3.49abA | 18.48aA | 41.89bB | |

| 66.66 | 4.07aA | 29.12aA | 67.18bA | 3.04bB | 9.92aB | 56.59aA | 3.14bB | 25.68aA | 41.68bA | |

| Neem (%) | Control | 3.21aA | 18.32aA | 83.35aA | 3.61aA | 6.48aA | 72.44aA | 3.56aA | 12.24aA | 86.87aA |

| 0.75 | 3.23aA | 15.04aA | 42.36bA | 3.10abA | 6.96aA | 52.05aA | 3.06abA | 13.44aA | 33.9bcA | |

| 1.5 | 2.94aA | 27.04aA | 71.67aA | 2.81abA | 12.88aA | 45.58aA | 2.86abA | 28.48aA | 56.8abA | |

| 3 | 2.45aA | 5.36aB | 36.02bA | 2.62bA | 28.16aA | 27.68aA | 2.41bA | 6.48aB | 23.86cA | |

| Insecticide | Conc. | ISO 01 | ISO 02 | ISO 03 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | Classif. | BI | Classif. | BI | Classif. | ||

|

Deltamethrin (mg L-1) |

Control | 100 | - | 100 | - | 100 | - |

| 16.67 | 139 | C | 170 | C | 129 | C | |

| 33.33 | 115 | C | 257 | C | 101 | C | |

| 66.66 | 150 | C | 301 | C | 109 | C | |

| Neem (%) | Control | 100 | - | 100 | - | 100 | - |

| 0.75 | 88 | C | 94 | C | 92 | C | |

| 1.5 | 115 | C | 128 | C | 144 | C | |

| 3 | 53 | MT | 225 | C | 57 | MT | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).