Submitted:

09 May 2023

Posted:

12 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

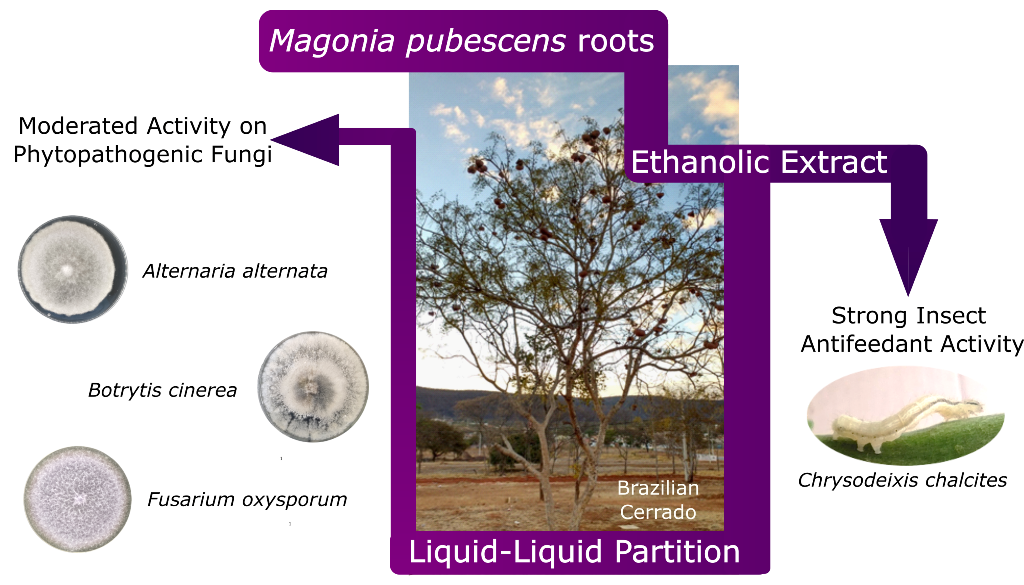

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Plant Extract Preparation

2.4. Liquid–liquid Partition Procedure

2.5. In Vitro Test-assay on Mycelium

2.6. Leaf-Disk Bioassay

3. Results and Discussion

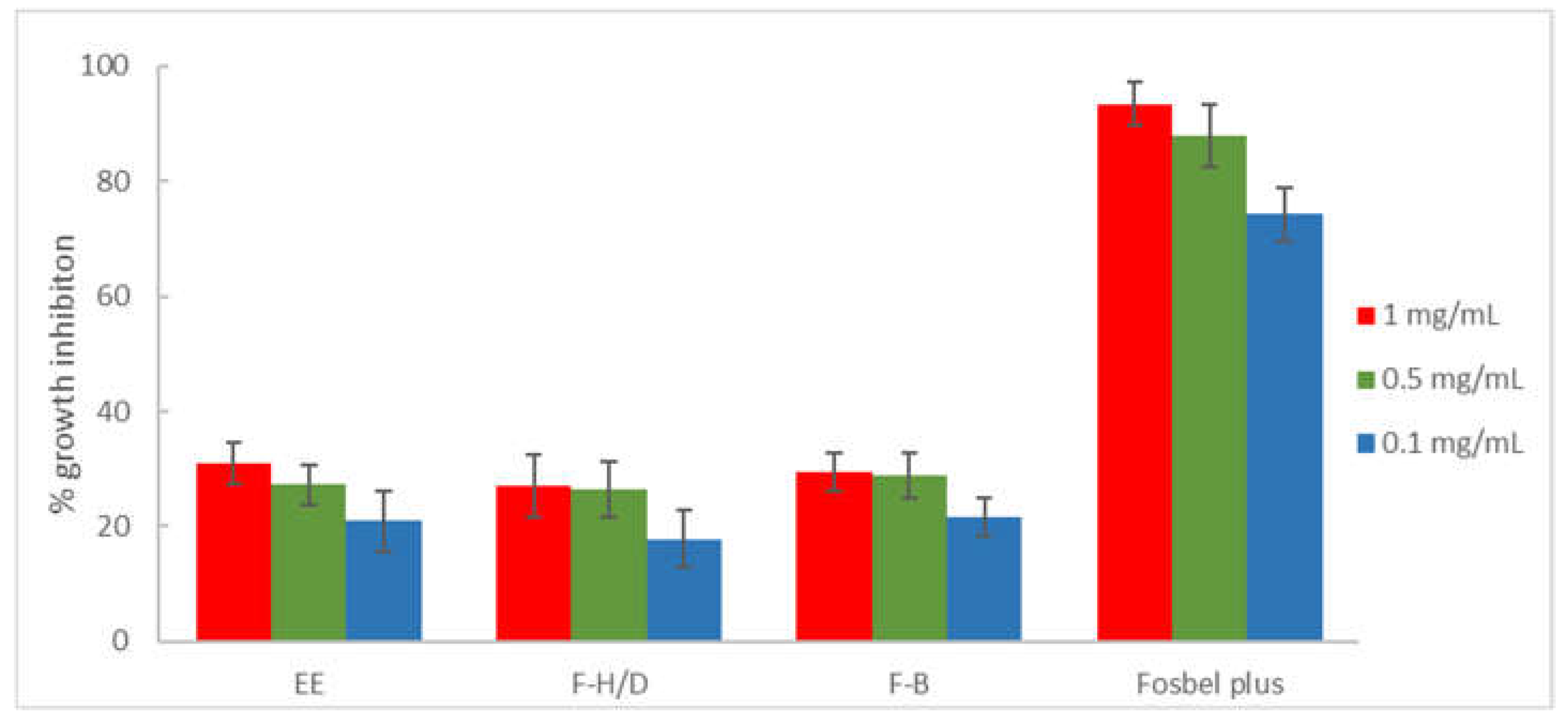

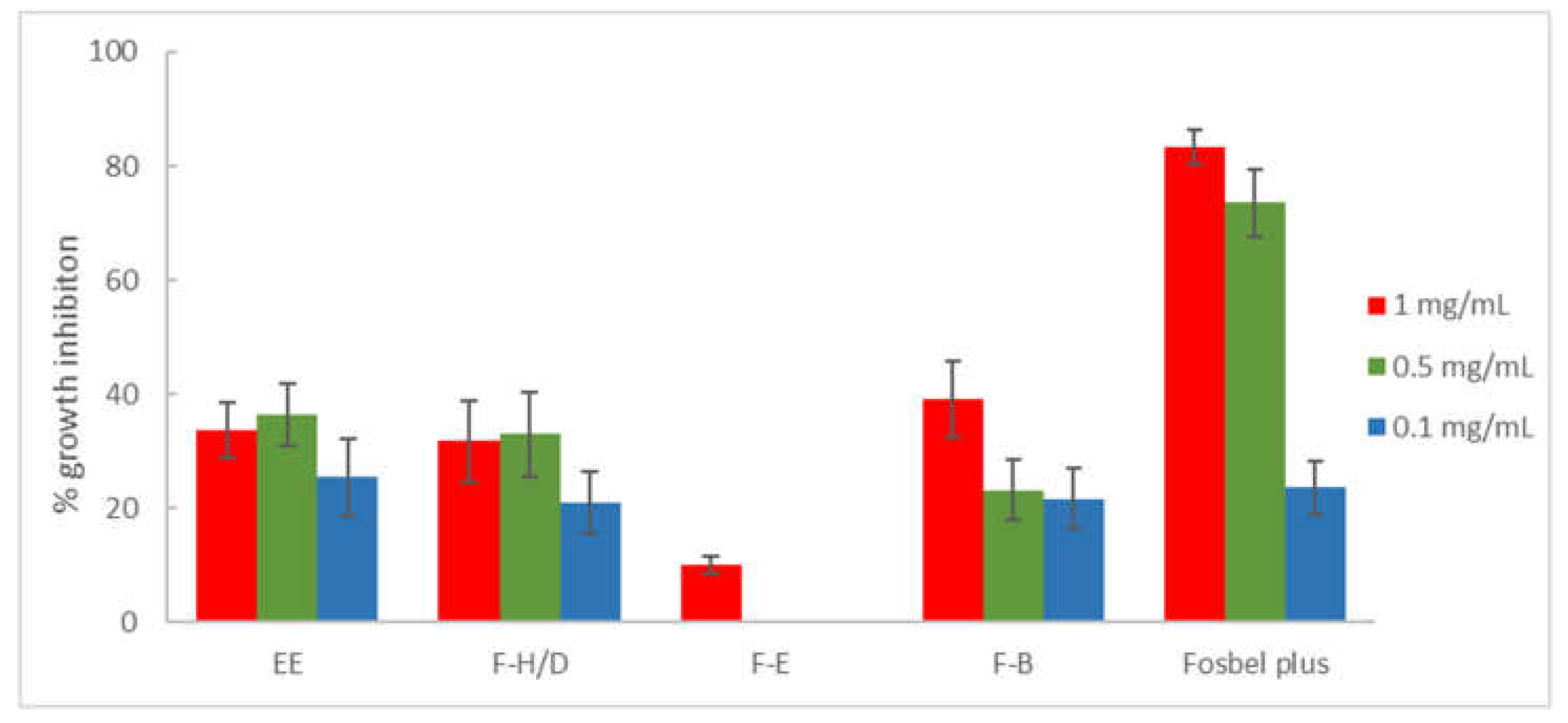

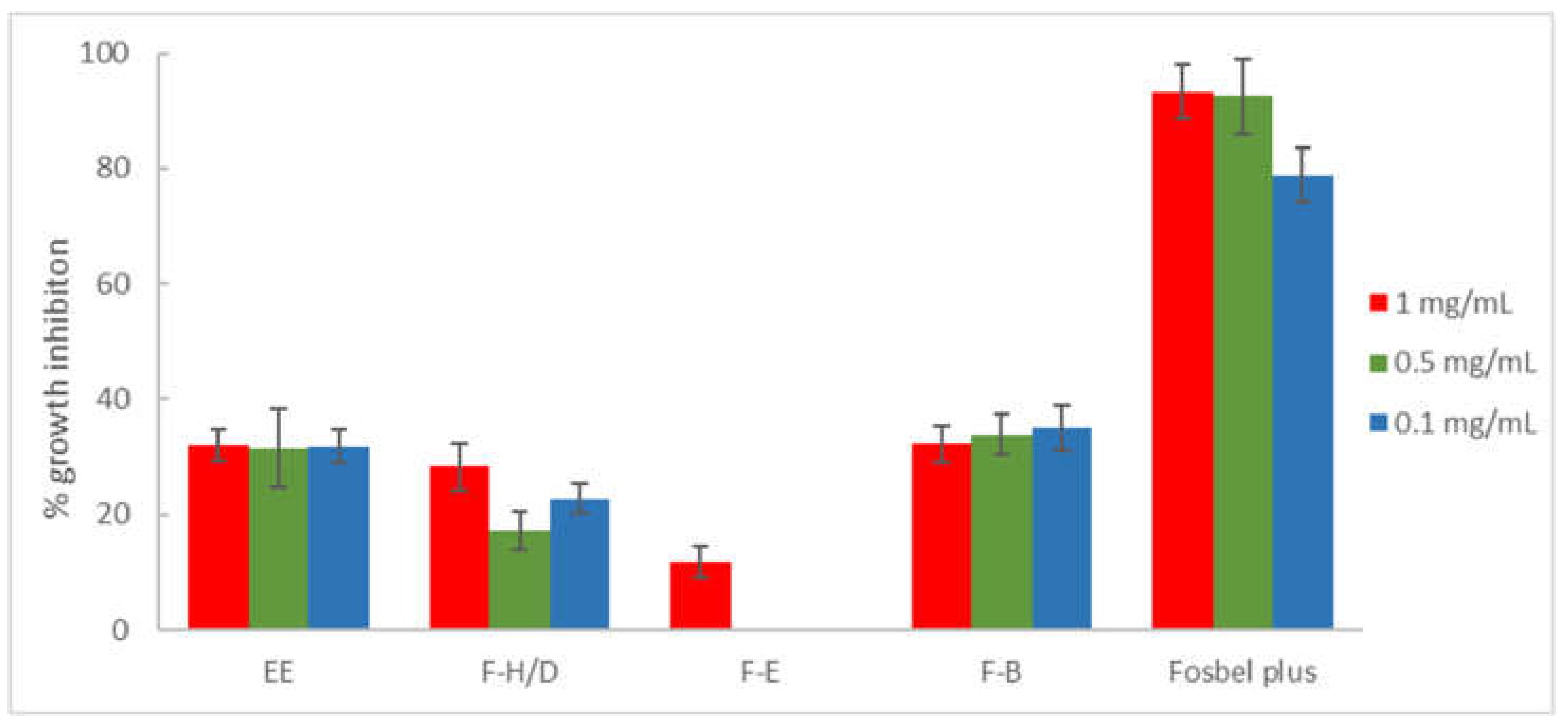

3.1. Antifungal In Vitro Test-assay on Mycelium

3.2. Insect Antifeedant Activity against Chrysodeixis chalcites

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2050: A third more mouths to feed. Available online: https://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/35571/icode/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Pandian, S.; Ramesh, M. Development of pesticide resistance in pests: A key challenge to the crop protection and environmental safety. Pesticides in Crop Production: Physiological and Biochemical Action, 1st ed.; Srivastava, P.K., Singh, V.P., Singh, A., Tripathi, D.K., Singh, S., Prasad, S.M., Chauhan, D.K., Eds.; Willey: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, N.; Pace, B.; Grieco, F.; Chimienti, M.; Tyibilika, V.; Santoro, V.; Capozzi, V.; Colelli, G.; Spano, G.; Russo, P. Botrytis cinerea and table grapes: a review of the main physical, chemical, and bio-based control treatments in post-harvest. Foods 2020, 9, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A. J.; Soares, J. M. S.; Nascimento, F. S.; Santos, A. S.; Amorim, V. B. O.; Ferreira, C. F.; Haddad, F.; Santos-Serejo, J. A.; Amorim, E. P. Improvements in the resistance of the banana species to Fusarium Wilt: A systematic review of methods and perspectives. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenderoth, M.; Garganese, F.; Schmidt-Heydt, M.; Soukup, S. T.; Ippolito, A.; Sanzani, S. M.; Fischer, R. Alternariol as virulence and colonization factor of Alternaria alternata during plant infection. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, D. M. Q.; Martins, S. D. S.; Guterres, D. C.; Martins, M. D.; Araújo, L.; Guimaraes, L. M. S.; Alfenas, A. C.; Furtado, G. Q. Diversity, prevalence and phylogenetic positioning of Botrytis species in Brazil. Fungal Biol. 2020, 124, 940–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Würz, D. A.; Rufato, L.; Bogo, A.; Allebrandt, R.; Bem, B. P.; Marcon-Filho, J. L.; Brighenti, A. F.; Bonin, B. F. Effects of leaf removal on grape cluster architecture and control of Botrytis bunch rot in Sauvignon Blanc grapevines in Southern Brazil. Crop Prot. 2020, 131, 105079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, J. N.; Beger, G.; Pereira, W. V.; De Mio, L. L. M.; Duarte, H. S. S. Gray mold in strawberries in the Paraná state of Brazil is caused by Botrytis cinerea and its isolates exhibit multiple-fungicide resistance. Crop Prot. 2021, 140, 105415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitolina, G. M.; Silva-Junior, G. J.; Feichtenberger, E.; Pereira, R. G.; Amorim, L. First report on quinone outside inhibitor resistance of Alternaria alternata causing Alternaria brown spot in tangerines in São Paulo, Brazil. Plant Health Prog. 2019, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#rankings/countries_by_commodity (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Deltour, P.; França, S. C.; Heyman, L.; Pereira, O. L.; Höfte, M. Comparative analysis of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum populations associated with banana on a farm in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitolina, G. M.; Silva-Junior, G. J.; Feichtenberger, E.; Pereira, R. G.; Amorin, L. Distribution of Alternaria alternata isolates with resistance to quinone outside inhibitor (QoI) fungicides in Brazilian orchards of tangerines and their hybrids. Crop Prot. 2021, 141, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CABI. Chrysodeixis chalcites datasheet; 2022 [cited 2022 August 22]. Database: Invasive Species Compendium [Internet]. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/13243.

- Del Pino, M.; Cabello, T.; Hernández-Suárez, E. Age-stage, two-sex life table of Chrysodeixis chalcites (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) at constant temperatures on semi-synthetic diet. Environ. Entomol. 2020, 49, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, T.; Simón, O.; Kaydan, M. B.; Tange, D. A.; Rodríguez, A. M. G.; Díaz, A. P.-B.; Murillo, P. C.; Suárez, E. H. Effects of several UV-protective substances on the persistence of the insecticidal activity of the Alphabaculovirus of Chrysodeixis chalcites (ChchNPV-TF1) on banana (Musa acuminata, Musaceae, Colla) under laboratory and open field conditions. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0250217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Cepero, J.J. Análisis de residuos y gestión integrada de plagas en platanera. Phytoma España 2015, 271, 48–52. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, J. R. S.; Da Silva, R. S.; Ramos, R. S.; Picanço, M. C. Distribution and invasion risk assessments of Chrysodeixis includens (Walker, [1858]) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) using CLIMEX. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionisio, M.A.; Calvo, F.J. Integrated Management of Chrysodeixis chalcites Esper (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) based on Trichogramma achaeae releases in commercial banana crops in the Canary Islands. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, G. D.; Parlakidis, P.; Mavropoulos, T.; Vryzas, Z. Particularities of fungicides and factors affecting their fate and removal efficacy: A review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M. B. Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century–fulfilling their promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheuk, F.; Basiouni, S.; Shehata, A. A.; Dick, K.; Hajri, H.; Lasram, S.; Yilmaz, M.; Emekci, M.; Tsiamis, G.; Spona-Friedl, M.; May-Simera, H.; Eisenreich, W.; Ntougias, S. Status and prospects of botanical biopesticides in Europe and Mediterranean countries. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, A. L.; Sylvestre, M.; Tölke, E. D.; Tavares, J. F.; Barbosa-Filho, J. M.; Cebrián-Torrejón, G. Plant-derived pesticides as an alternative to pest management and sustainable agricultural production: prospects, applications and challenges. Molecules 2021, 26, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, W. R.; Barreto, M. C.; Seca, A. M. L. Aqueous and ethanolic plant extracts as bio-insecticides— Establishing a bridge between raw scientific data and practical reality. Plants 2021, 10, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, J. G. S.; Almeida, A. S.; Pinto-Zevallos, D.; Barreto, I. C.; Cavalcanti, S. C. H.; Nunes, R.; Teodoro, A. V.; Xavier, H. S.; Filho, J. M. B.; Guan, L.; Neves, A. L. A.; Duringer, J. M. From plant scent defense to biopesticide discovery: Evaluation of toxicity and acetylcholinesterase docking properties for Lamiaceae monoterpenes. Crop Prot. 2023, 164, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellonzi, T. K.; Dutra, F. V.; Souza, C. N.; Rezende, A. A.; Gasparino, E. C. ; Pollen types of Sapindaceae from Brazilian forest fragments: apertural variation. Acta Bot. Bras. 2020, 34, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofidiya, M. O.; Jimoh, F. O.; Aliero, A. A.; Afolayan, A. J.; Odukoya, O. A.; Familoni, O. B. ; Evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial properties of six Sapindaceae members. J. Med. Plan. Res. 2012, 6, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, M. C.; Scalon, S. P.; Sari, A. P. ; Biometria de frutos e sementes e germinação de Magonia pubescens St. Hil (Sapindaceae); Rev. Bras. Sementes 2009, 31, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.D.; Carneiro, F.M.; Fernandes, A.S.; Morais, J.M.; Borges, L.L.; Chen-Chen, L.; de Almeida, L.M.; Bailão, E.F.L.C. Toxic potential of Cerrado plants on different organisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesquita, M. L.; Paula, J. E.; Pessoa, C.; Moraes, M. O.; Costa-Lotufo, L. V.; Gourgnet, R.; Michel, S.; Tillequin, F.; Espindola, L. ; Cytoxic activity of Brazilian Cerrado plants used in traditional medicine against cancer cell lines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 123, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, W.; Oliveira, G. M.; Silva, I. G. Toxicidade do extrato etanólico de Magonia pubescens sobre larvas de Aedes aegypti. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2003, 36, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, J. M. Ação leishmanicida de extratos de plantas no desenvolvimento de promastigotas de Leishmania amazonensis e estudo do perfil metabólico utilizando a técnica de cromatografia líquida de alta eficiência (CLAE). Master’s thesis, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, M. M.; Santos, K. T.; Royo, V. A.; Fonseca, F. S.; Menezes, E. V.; Mercadante-Simões, M. O.; Oliveira, D. A.; Junior, A. F. J. Antioxidant activity, total flavonoids and volatile constituents of Magonia pubescens A. St.-Hil. Med. Plants Res. 2015, 9, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, A. R. A.; Camargo, K. C.; Simões, M. O. M.; Ferraz, V. P.; Pereira, M. T.; Evangelista, F. C. G.; Sabino, A. P.; Duarte, L. P.; Alcântara, A. F. C.; Sousa, G. F. Chemical composition of Magonia pubescens essential oils and gamma-radiation effects on its constituents and cytotoxic activity in leukemia and breast cancer model. Chem. Biodiversity 2021, 18, e2100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, J. C.; Coelho, M. F.; Albuquerque, M. C.; Azevedo, R. A. Seedling emergence of Magonia pubescens St. Hil. Sapindaceae a function of temperature. Amaz. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2011, 54, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L. B.; Silva, J. C.; Pavan, B. E.; Pereira, F. F.; Maggioni, K.; Andrade, L. H.; Candido, A. C. S.; Peres, M. T. L. P. Insecticide irritability of plant extracts against Sitophilus zeamais. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 978–983. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M. J.; Mercadante-Simões, M. O.; Ribeiro, L. M. Secondary-cell-wall release: a particular pattern of secretion in the mucilaginous seed coat of Magonia pubescens. Am. J. Bot. 2020, 107, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupchan, S.M. Recent advances in the chemistry of terpenoid tumor inhibitors. Pure Appl. Chem. 1970, 21, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosoveanu, A.; Hernandez, M.; Iacomi-Vasilescu, B.; Zhang, X.; Shu, S.; Wang, M.; Cabrera, R. Fungi as endophytes in Chinese Artemisia spp.: Juxtaposed elements of phylogeny, diversity and bioactivity. Mycosphere 2016, 7, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosbel-Plus. Available online: https://www.infoagro.com/agrovademecum/fito_m.asp?nreg=22421 (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Liu, T.-X.; Zhang, Y. Side effects of two reduced-risk insecticides, indoxacarb and spinosad, on two species of Trichogramma (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae) on cabbage. Ecotoxicol. 2012, 21, 2254–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajonero, J. G.; Parra, J. R. P. Selection and suitability of an artificial diet for Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) based on physical and chemical characteristics. J. Insect Sci. 2017, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simón, O.; Bernal, A.; Williams, T.; Carnero, A.; Hernández-Suárez, E.; Muñoz, D.; Caballero, P. Efficacy of an alphabaculovirus-based biological insecticide for control of Chrysodeixis chalcites (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on tomato and banana crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escoubas, P.; Lajide, L.; Mitzutani, J. An improved leaf-disk bioassay and its application for the screening of Hokkaido plants. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1993, 66, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Coloma, A.; Terrero, D.; Perales, A.; Escoubas, P.; Fraga, B. M. Insect antifeedant ryanodane diterpenes from Persea indica. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, K.; Sun, G.; Yang, L.; Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Yin, P.; Huang, S.; Gao, F.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L. Design, synthesis and insecticidal activity and mechanism research of chasmanthinine derivatives. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample2 | Choice Feeding assay | Non-choice Feeding assay | Antifeedant category |

|---|---|---|---|

| EE3 | 92.14 | 95.16 | strong insect antifeedant |

| F-H/D3 | 60.52 | -27.67 | weak insect antifeedant |

| F-E3 | -108.09 | 61.10 | appetite suppressor |

| F-B | -6.69 | 60.71 | appetite suppressor |

| F-W3 | -74.57 | 44.73 | inactive |

| C4 | 97.95 | 99.04 | strong insect antifeedant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).