Introduction

Humans have always used herbal treatments as medicines. Although people from all walks of life have utilized herbs in past times, India contained some of the oldest, most diverse, and most rich customs when it comes to using medicinal plants (Bhatt 1998-2099). Since The demand for medicinal herbs is growing daily in the current environment, pharmaceutical companies are working to investigate medicinal substances for possible therapeutic benefits (Neekhra et al. 2017). Herbal medicines form a key part of cure in traditional medical systems such as Ayurveda, Rasa, Siddha, Unani, and Naturopathy. Recently, there has been a modified in global trend from synthetic to natural drug, which we can perceive ‘Back to nature’. Medicinal herbs have been recognized for millennia and are highly valued all over the world as an abundant source of therapeutic agent for treatment of disease and ailment. India is the world's leading producer of herbal medicines and is appropriately referred to as the "Botanical Garden of the World." In this regard, India holds a special place in the globe, as it is home to numerous acknowledged indigenous medical systems, including Siddha, Ayurveda Homeopathic, Unani, Yoga, and Naturopathy, which were used to treat the physical wellness of its citizens. Traditional medicine has the longest history in India. India's medical literature offers extensive information on the customs and traditional characteristics of medicinally valuable natural substances. Most of the human food and medicine comes from plants. There are currently around 7000 plant species that are regarded as edible and can be grown by hand or discovered in the wild. The presence of diverse phytochemicals in plants helps them to provide a range of health benefits (Rastogi et al.,1990). In comparison to macronutrients like proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates, these phytochemicals which are functional are chemical constituents that are usually secondary metabolites which are found in lesser quantities. To improve general health, many nations encourage the consumption of medicinal plants as functional or everyday foods. Food and medicine share a same source in Eastern nations, and both are crucial for preserving and enhancing health as well as preventing and treating illnesses (Mohammed et al., 2022). The plant Streblus asper, sometimes known as "monkey grass" or "wild tea," is widely used in traditional medicine, especially in Southeast Asia, to cure a variety of illnesses. Among its many therapeutic applications, one of the most promising fields of research is its potential for hepatoprotection, or the protection of the liver from damage. Liver is being one of the body’s most essential organs is highly susceptible to injury from environmental toxins, viral infections, alcohol consumption, and other factors. As such, substances with hepatoprotective properties are of great interest in the management of liver disorders. This review will discuss the hepatoprotective properties of S. asper, including its bioactive compounds, mechanisms of action, and the scientific evidence supporting its use in liver health. This little tree is native to tropical nations including Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India. Sheora, Koi, Berrikka, Bar-inka, Rudi, toothbrush tree and Siamese rough bush are some of its many names (Rastogi and Dhawan,1990). It is an enlarged tree or stiff shrub with pubescent or tomentose branchlets. Rhomboid, Rigid, ovate, elliptic, or obovate, and unpredictably serrated, the leaves measure 2 to 4 inches, while the petiole measures 1/12 inch. The peduncles are short and scabrid, the flowers are tiny, and the heads of male are globose, single or 2-nate, and occasionally androgynous. The peduncles of female blooms are longer. Pisiform fruit with golden perianths (Somashikharetal et al.,2013) The physical characteristics of Streblus asper, a monoecious or dioecious tree, are covered below: Bark: The surface of the bark is dark brown and scabrous. When young, the lenticels are noticeable, and have short branchlets, hairs stiff. The caducous stipules are tiny (Gilbert.,2003). Leaves: The leaves are either sessile or petiolate in a short time. The base of the leaf is obtuse to cordate; the border is whole or irregularly crenate, the apex is blunt to briefly acuminate, and the leaf blade is elliptic-obovate to elliptic, leathery in texture, and scabrous (Hooker.,1885). The midvein is surrounded by four to seven secondary veins. Flowers: The male flowers encircle a single, sessile female flower in the centre of bisexual inflorescences. Male inflorescences can be single or paired, capitate, with a glabrous peduncle measuring 8–10 mm. Bracts are sparse and narrowly elliptic at the base of the inflorescence, with two bracteoles at the base of the calyx that are larger than the bracts. Female inflorescences have bracteoles at the base of the calyx and are pedunculated with one or two bracts at the base of the peduncle (Kritikar and Basu.,1975). Male flowers are subsessile; pistillode is conic to cylindric. In the female flowers, the calyx lobes are pubescent; the ovary is globose; style is apically branched, 6–12 mm in fruit. Fruits: The drupes are yellow, globose, about 6 mm in diameter, indehiscent, and, when young, encased in expanded calyx lobes. They lack a fleshy base. It may be discovered in the drier regions of India, ranging from Rohikund, as well as eastward and southward. Traditional/Ethnomedicinal Uses a popular ethnomedical plant that is also used in Ayurveda is Streblus asper. It is also well known to be used in Indian traditional folk medicine. These phytochemicals are divided into several groups, including medical, functional foods, nutraceuticals, and botanicals, depending on their uses and advantages. To improve general health, several nations encourage the use of medicinal plants as functional foods or daily foods (Kumar et al.,2011). Food and medicine have a same source in Eastern nations, and both are crucial for preserving and enhancing health as well as preventing and treating illnesses. The juice of root S. asper has been used by the Marma tribe in Bangladesh to promote delayed menstruation and cure irregular menstruation (Rastogi et al. 2006). The leaves of the plant are also reported to be chewed with salt as an anthelmintic (Alam 1992). According to earlier bioactivity tests, the 50% ethanol extract of its leaves exhibited bactericidal activity (Bhandary et al. 1995). According to Some lab tests, S. asper demonstrates a broad spectrum of biological and pharmacological properties that could support the plant's traditional medicinal applications. The extraction and identification of several potential beneficial chemical compounds, such as cytotoxic cardiac glycosides (stebloside and mansonin) (Fiebig et al.,1985) has further bolstered the benefits of the traditional use of S. asper (Kumar et al. 2011). For example, medicinal plants are used as functional foods for medical and therapeutic reasons as well as everyday meals in nations like China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia. Over the last several decades, Europe has also brought in a variety of exotic fruit kinds and other species from other continents. Natural products have provided around half of the novel chemical compounds that have been developed in the last 20 years. As a result, the industry has focused its efforts on identifying and defining the active principles as well as elucidating the connection between structure and activity (Bhandary et al.,1995). A few plant species that are recognized for provide Typical health advantages are examined by investigators to identify the different pharmacological potential of the plants. The most advantages of medicinal plants, particularly in the fields of pharmacology and medicine, continue to draw more and more attention. For millennia, people have acknowledged the healing effects of medicinal plants (Kumar et al.,2011). High-grade dried herbal products that nearly match the quality of common raw herbal materials have been more and more sought after in recent years. Herb quality is influenced by several elements, including colour. Numerous health issues, including high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes, heart disease and aging, are exacerbated by free radicals.Traditionally, S. asper has been used to treat hypertension and heart disease. This plant's seeds are beneficial for piles, diarrhoea, epitaxies, and other conditions. In leukoderma, the paste-like seed is placed externally. This plant's root was used to treat epilepsy, inflammatory swelling, and boiling wounds; its juice had an astringent and antiseptic action. People are becoming more concerned with leading healthy lives, and there is a growing need for safe and natural food preservatives (Chawla et al.,1990).

As a result, researchers are becoming more interested in finding possible natural antioxidants. The phytochemical makeup and antioxidant capacity of the ethanol and water extracts of S. asper leaves prepared by different drying methods are mostly unknown. The plant is now in danger of becoming extinct because of the destructive collection of plant parts for medical purposes and the destruction of its natural habitat caused by deforestation. Furthermore, low rates of seed germination and poor rooting capacity of the vegetative cuttings hinder the large replication of this tree species using traditional vegetative propagation techniques. Numerous endangered and uncommon plant species are cultivated in vitro because they do not respond well to conventional methods of multiplication (Kumar et al.,2013). Plant growth regulators' qualitative and quantitative properties, as well as the medium composition, are critical factors in micropropagation. As a result, improving these conditions is necessary before beginning any in vitro work. Since there are no publications on S. asper in vitro propagation, we were motivated to create a micropropagation methodology for this endangered and significant medicinal woody plant species. The herb, known as "sora" in Assam, is said to be able to prevent any tooth-related problems when used as a dental stick. It has also been linked to the long-lasting teeth of the state's elderly population since ancient times. Researchers have discovered that the plant is abundant in triterpenoids, cardiac glycosides, and phytosterols. There are many applications for the tree. It is one of the possible sources for papermaking in Thailand. With its delicious edible fruits, tea and cleaning leaves, medicinal seeds, animal feed, decorative potential, valuable timber, and fuel in the form of firewood and charcoal, Streblus asper is a resource that may be used for a variety of purposes, mostly in Vietnam. It has long been used to treat colic, cholera, diarrhoea, menorrhea, dysentery, epilepsy, cancer, and inflammatory swelling (Fiebig et al.,1985). The bark of stem has been used to isolate α-amyrin acetate, lupeol, β-sitosterol, lupeol acetate, α-amyrin, and diol, mansonin and strebloside. However, the antidiabetic benefit of S. asper stem bark is not supported by scientific research (Rastogi et al.,2006). The leaf extract has antibacterial properties, insecticidal activity against mosquito larvae, and a protective impact against oral and dental illness. There are a lot of cardiac glycosides in S. asper. Human cancer cell lines are toxic to several cardiac glycosides. There have been reports of cytotoxic activity in two cardiac glycosides of this plant, strebloside and mansonin and volatile oil. Phytoconstituents of s.asper: Streblus asper is recognized for its rich content of cardiac glycosides, compounds with notable pharmacological properties. Reichstein and his team successfully isolated over 20 cardiac glycosides from the root bark of S. asper, structurally characterizing 15 of them using degradative techniques. These include kamloside,asperoside, strebloside, strophalloside, indroside, strophanolloside, glucogitodimethoside, sarmethoside, glucostrebloside, gitomethoside, and sarmethoside. Experimental studies have further expanded this repertoire, identifying additional glycosides such as glucokamloside, cannodimemoside, and 16-O-acetylglucogitomethoside. Recent research has also led to the isolation of three new cardiac glycosides—strophanthidin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-6-deoxy-β-D-allopyranoside, 5βH-16β-acetylkamaloside, and mansonin-19-carboxylic acid—from the roots of S. asper. These compounds have demonstrated significant cytotoxic activities against various human cancer cell lines, with some exhibiting superior selectivity compared to standard chemotherapeutic agents like cisplatin. Additionally, certain glycosides have shown melanogenesis-inhibitory effects, indicating potential applications in treating hyperpigmentation disorders

S. asper's Taxonomical Categorization

Kingdom: Plantae (Plants)

Phylum: Tracheophyta (Vascular plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons)

Order: Rosales

Family: Moraceae (Mulberry family)

Genus: Streblus

Species: Streblus asper Lour.

Bioactive Compounds in Streblus asper

Streblus asper contains a variety of bioactive compounds that may contribute to its hepatoprotective effects. The plant's leaves, stems, and roots are rich in flavonoids, alkaloids, phenolic acids, and tannins. These compounds possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties, all of which can potentially support liver health (Rastogi et al.,1990) The polyphenolic compounds available in this species are known for their potent antioxidant properties. They help neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative stress, a key factor in liver cell damage and the progression of liver diseases such as fatty liver, cirrhosis, and hepatitis. Alkaloids in S. asper have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective properties. These compounds may modulate the immune response and reduce liver inflammation, which is a common feature in liver diseases (Das et al.,1991). These compounds contribute to the plant’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, helping to protect liver cells from damage and supporting liver regeneration. Several bio active compounds in S. asper have liver protecting properties as, making them beneficial for treating liver disorders such as fatty liver disease, liver fibrosis, hepatitis, and liver toxicity (Neekhra et al.,2017) (Meena et al., 2024).

Table 1.

Phytochemical constituents of Streblus asper.

Table 1.

Phytochemical constituents of Streblus asper.

| Plant parts use |

compounds |

Ethnomedicinal uses |

References |

| Root |

3′-Hydroxy-isostrebluslignaldehyde,

7′R,8′S)-4,4′-dimethoxystrebluslignanol

3,3′-methylene-bis-(4-hydroxybenzaldehyde)

cerotic acid glycoside,

Hexacosenyllactones,

nonadecanyl salicylate glycoside, n-octacosanoic acid

|

Ulcer, epilepsy, obesity |

(Aeri et al., 2012)

(Nie et al., 2016)

(Aeri et al., 2015) |

| Stem |

Alkaloids |

Toothache, Pyorrhoea |

Ibrahim et al., (2013) |

| Leaves |

silymarin |

Liver damage, Jaundice, fatty liver, dry cough |

|

| Stem bark |

Lupeol, lupeol acetate,

α-amyrin acetate, α-amyrin, β-sitosterol, mansonin

Lup-20(29)-en-3-β-ol |

Dysentery, diarrhoea, Filariasis, wounds |

(Kandali and Konwar, 2012)

(Barua et al., 1968) |

| Milkyjuice /latex |

|

Astringent, antiseptic, pneumonia, sore feet |

Karan et al., (2011) |

| Fruits |

|

Epistaxis, epilepsy, diarrhoea |

Limsong et al., (2004) |

| Seed |

|

Epistaxis, epilepsy, diarrhoea |

NISCOM., 1992 |

Table 2.

Phyto-compounds detected in advanced instrumentation/spectral analysis.

Table 2.

Phyto-compounds detected in advanced instrumentation/spectral analysis.

| Compounds |

GCMS |

LCMS |

FTIR |

NMR |

TLC |

| Glycosides |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Steroids |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Phenolic compouds |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Flavonoids |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Saponins |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Alkaloids |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Terpenoids |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Tanins |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cyanogenic glycosides |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Ethnomedicinal Uses-

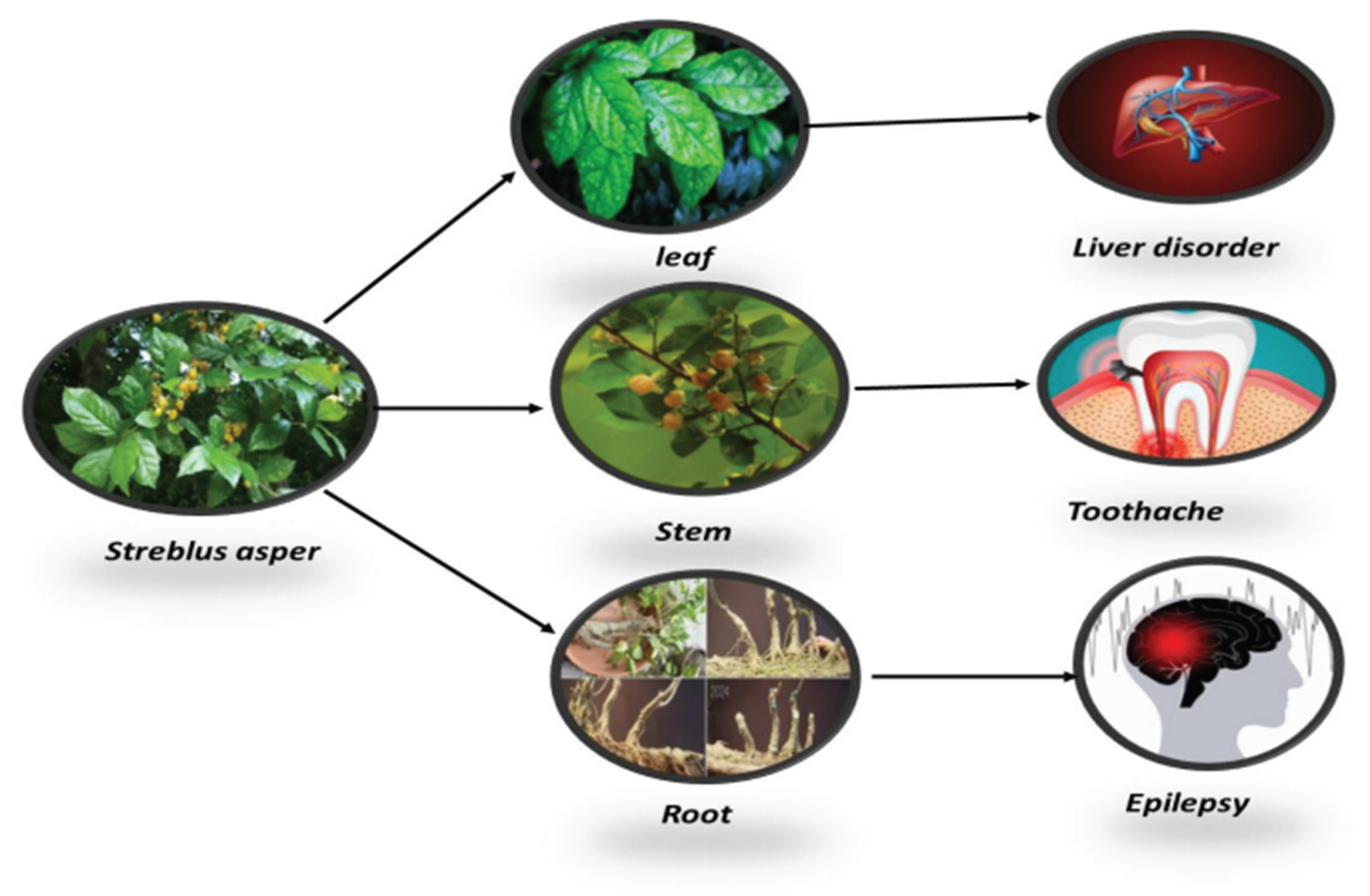

Streblus asper is one well-known ethnomedicinal herb that is used as well in Ayurveda. Its application in Indian folk medicine is also well known. In addition to treating fever, diarrhoea, and dysentery, it is also used to clean wounds and treat cardiac diseases, epilepsy, oedema, leprosy, elephantiasis, and tuberculous glands (Aeri

et al.,2012). Its bark has also been shown to trigger an immunological reaction. The stem is used to treat toothaches and pyorrhoea, The leaf is mostly used for treating liver diseases and damage, while the root itself can be used to treat epilepsy. (

Figure 1). In addition to treating sinusitis, oedema, ulcers, and heart problems, the root also functions as an antidote to snakebite and influences the myocardium. The latex may be used to painful heels, chapped hands, and glandular swellings as an astringent and antiseptic. The leaves lower labour pain, controls blood pressure, and cures fever. The seed is also used to cure diarrhoea, epistaxis, and piles (Alam 1992). The twigs were eaten to clean teeth and treat pyorrhoea (Krititsaneepaiboon), and they were used as toothbrushes.

S. asper is utilized as traditional medicine by several tribal cultures to cure a variety of conditions, including impotence, rheumatic pain, elephantiasis, toothache, dental caries, oedema, diarrhoea, dysuria, and burn infection prevention. In folk medicine, different components of

S. asper are used to cure various illnesses (Chatterjee

et al., 1992). The bark extract has been used to treat gingivitis, fever, diarrhoea, and toothaches. It has been shown that the leaf extract possesses insecticidal properties against mosquito larvae. To strengthen teeth and gums, the plant's branch has been used as a toothbrush. The root has been used to cure obesity and epilepsy, as well as to treat bad ulcers, sinusitis, and snake bites locally. The milky liquid has been used as a painkiller for neuralgia, as an antiseptic and antibacterial for chapped hands and painful heels, and as a treatment for pneumonia and swelling of the cheeks (Aeri

et al.,2012). Leaves and fruits have been used to treat eye conditions. Seeds have helped with diarrhoea, piles, and epistaxis. The solution of stem bark helps with chyluria, lymphedema, and other filariasis symptoms. It has also been used to treat stomach-aches, urinary problems, piles, oedema, and wounds.

Potential Effects of Streblus asper on Liver Disorders

Based on some studies, Streblus asper could have hepatoprotective advantages, which means it could help in protecting the liver from the effects of oxidative and toxic damage. The plant contains compounds that could reduce inflammation and support liver regeneration. The hepatoprotective properties of Streblus asper are considered to result from the ability to alter liver function, lower inflammation, and resist oxidative damage (Chen et al.,2012). These effects can help prevent or mitigate liver injury caused by a variety of factors, including alcohol abuse, toxins, and viral infections.

Scientific Evidence Supporting Hepatoprotection

Although much of the evidence for S. asper's hepatoprotective properties comes from traditional uses and in vitro studies, several Animal models have provided significant data on the potential therapeutic effects of this plant on liver health. A study which has been released in the journal of Ethnopharmacology investigated the hepatoprotective effect of S. asper leaf extract in rats with induced liver damage (Li et al.,2008) The results showed that the extract significantly reduced liver enzyme levels (ALT, AST) and improved liver histology, indicating a reduction in liver damage and inflammation. Additionally, the extract was found to enhance the antioxidant status of the liver, further supporting its potential as an antioxidant agent. Another study demonstrated that S. asper extract may promote liver regeneration following serious liver damage (Anand et al., 2022).

In this investigation, rats treated with S. asper extracts exhibited increased hepatocyte proliferation, suggesting that the plant may have a role in stimulating the repair of liver tissue. Studies have also explored the molecular mechanisms behind the hepatoprotective effects of S. asper. Research has shown that the plant can modulate expression of genes linked in oxidative stress and inflammation, further supporting its role in reducing liver damage and promoting healing (Kumar et al.,2020). While the available evidence suggests that Streblus asper has significant potential as a hepatoprotective agent, further, to fully understand its modes of action, additional study is required bioactive components Efficacy usefulness in clinical studies including humans. Most of the studies conducted thus far have been on whether in the laboratory or in animal models, and randomized controlled trials in humans to establish its therapeutic potential in liver disorders. Streblus asper shows promise as a natural remedy for liver diseases due to its antioxidant, hepatoregenerative and anti-inflammatory properties (Das et al.,2021). With more rigorous clinical studies, it may become a valuable adjunct or alternative treatment in managing liver disorders. However, as with any herbal remedy, before introducing it to their treatment plan, individuals should speak with their healthcare professionals (Rahman et al., 2014)

Traditional Use in Liver Disorders

In traditional medicine, Streblus asper is used for treating jaundice, liver enlargement, and other liver-related conditions (Fiebig et al., 1985; Das & Beuria, 1991). The leaves or extracts are Usually consumed in powdered or tea form. The plant is considered valuable in older medical systems like Ayurveda and ancient Chinese Medicine (TCM) for its claimed medicinal properties, which include supporting the liver's function and healing ailments including jaundice, liver enlargement, and overall liver weakness. The use of Streblus asper for liver disorders is primarily based on its reputed hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, and detoxifying properties. According to traditional knowledge, the plant is often prepared as a tea, decoction, or powder made from its leaves, bark, or roots, which are believed to help in liver purification, inflammation of the liver reduction, and liver function enhancement. One of the most common disorders treated with Streblus asper is jaundice, which is defined as yellowing of the skin and eyes because of increased bilirubin levels. In such cases, it is thought to enhance bile secretion and facilitate the detoxification of the liver, promoting the reduction of bilirubin and easing symptoms of jaundice (Gaitonde et al., 1964). Similarly, the plant’s leaves are often used in the treatment of liver enlargement, where it is believed to reduce swelling and discomfort associated with liver congestion. The anti-inflammatory properties of S. asper Particularly essential when considering chronic liver illnesses, such as cirrhosis and hepatitis, because inflammation is an essential component in the development of the illness. By reducing inflammation, S. asper may prevent further damage to liver cells, promoting healing and regeneration of damaged tissue. Additionally, traditional healers often prescribe the plant to enhance liver detoxification, especially in cases of alcohol-induced liver damage, where the liver’s capacity to process and eliminate toxins may be compromised. The plant’s role in detoxification is believed to stem from its antioxidant properties, may reduce oxidative stress, a common cause for numerous liver illnesses, and neutralize harmful free radicals. Another aspect of traditional use is the belief that Streblus asper can help balance the liver's "Qi" (energy) in TCM, suggesting its use not only for physical symptoms but also for restoring overall vitality and wellness (Nag et al.,2022). While these traditional uses are rooted in centuries of practice and anecdotal evidence, modern research into the plant’s bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids has begun to provide a scientific foundation for these practices. Some studies have shown that Streblus asper may possess hepatoprotective and antioxidant properties, supporting the traditional belief in its ability to help protect and heal the liver. However, while these early findings are promising, clinical evidence in humans remains limited, and much of the knowledge surrounding S. asper's efficacy in liver disorders still stems from its historical use rather than rigorous scientific validation. It is important to note that traditional practices often incorporate Streblus asper alongside other herbs or treatments, and its effectiveness is typically evaluated as part of a holistic approach rather than as a standalone remedy (Fiebig et al.,1985).As with any traditional medicine, modern healthcare professionals advise caution and recommend further investigation into the plant’s safety and efficacy, particularly for individuals receiving additional medications or those with preexisting liver issues. Despite the lack of extensive clinical trials, the continued use of Streblus asper in traditional medicine speaks to its enduring reputation as a liver tonic, with its applications reflecting a deep understanding of herbal medicine and its role in maintaining liver health across cultures. As interest in natural remedies grows, further research into it can provide valuable insight regarding its potential as a treatment option for liver disease, crossing the gap between accepted wisdom and modern medicine (Kumar et al.,2020).

Commercial Effect-

There have been reports of the commercial usage of various S. asper components and products, which enhances the plant's worth beyond its therapeutic qualities. On Dysdercus cingulatus, it was shown that the S. asper stem bark extract had insecticidal properties and was able to act as a biopesticide. Slate and papermaking are two applications for fibre derived from S. asper bark (Meena et al.,2024). The S. asper leaves, together with mulberry and palm, were the main ingredients in several traditional Lanna medicinal plant recipes from various regions of Thailand. Wood is utilized as fuel and to construct cartwheels and yokes in southern India. Curiously, the tree's twigs were used to protect homes from lightning by becoming lodged in and around thatched roofs (Neekhra et al., 2017) High nutritional value vermicompost comprising phosphorus, Nitrogen, salt, calcium, and sulphur may be made from the dried leaves of S. asper. A parasitic epiphytic plant Cuscutare flexa Roxb. has been utilized extensively as a food that performs a purpose, is hosted by S. asper. Its twigs generate a milk-clotting protease that resembles rennin and may be used in the manufacturing of cheese. Because it is stable at alkaline pH levels, it may also be used in the cheese business. Because S. asper leaves are full of fibre, facilitating the production of milk, and because plant leaves can be used as a protein source, they can be fed to ruminants (Li et al.,2008) The leaves of S. asper are more advantageous than green grass and may be fed to cattle as a wholesome feed. When administered orally to ruminants such as goats or cows, the fruit juices of S. asper may have cooling or refrigerant properties.

Properties of Pharmacology

Numerous researchers have documented S. asper's diverse biological activity in a range of in vitro and in vivo test settings. Anti- filarial, Cardiotonic, anticancer, antibacterial, antiallergic, and antimalarial properties have been reported for various sections of this plant (Karan et al., 2011).The following provides a more thorough description of them.

Cardiotonic Effect

Indigenous medicine frequently uses the medicinal plant Streblus asper particularly in Southeast Asia and India. Studies have explored its potential cardiotonic effects, which refer to its ability to enhance the contractility of the heart muscle, like digitalis-like drugs. Some phytochemicals in this plant, such as flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids, may enhance cardiac contractility by influencing calcium ion channels in cardiac myocytes (Ibrahim et al.,2013). It may inhibit Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase, like cardiac glycosides, leading to increased intracellular calcium and stronger heart contractions. The plant has been shown to exhibit vasodilation and reduce blood pressure, possibly benefiting heart function (Miao et al.,2018) The whole ethanolic extract of S. asper root bark was found to have unique impacts on the uterus of guinea pigs, isolated rabbit intestine, isolated frog heart, and blood pressure. When injected intravenously to white mice, an ab-unsaturated lactone was found to have an LD50 of 4.8 mg kg. Investigations on isolated frog heart have shown that it has a positive ionotropic effect at 10-5 dilutions and a systolic response at 10-4 dilutions. The chemical's in vitro spasmodic activity on the smooth muscles of the rabbit intestine and guinea pig uterus was noticed at high enough dilutions (NISCOM.,1992). Pharmacological research has shown that the medication has a clear effect on the heart (Gaitonde et al.,1964).

Anti-Filarial Effect

Extracts of Streblus asper have been tested against filarial parasites like Brugia malayi and Setaria Cervi. The plant’s phytochemicals interfere with parasite motility and metabolic functions, leading to their death. Due to its natural anti- filarial properties, Streblus asper could be explored for developing new anthelmintic drugs. The extracts can Inhibit microfilaria development, suggesting potential use in filariasis treatments. S. asper is believed to induce oxidative stress in filarial worms, disrupting their cellular metabolism (Singh et al.,1998). It may also modulate the host immune system to target the parasites effectively. In rats, Litomosoides carinii significantly inhibited by the crude S. asper stem bark aqueous extract. According to the research, the extract's two cardiac glycosides—strebloside and asperoside—are what give it its anti-filarial properties (Pandey et al.,1990). Asperoside, the more potent microfilaricide of the two glycosides, was efficacious against L. carinii in cotton rats given 50 mg kg 1 orally, Comparing the controls with tumours, mice fed with plant extract exhibited a better survival rate. Numerous growth metrics were significantly and dose-dependently reduced by the plant extract (Baranwal et al.,1978).

Anti-Cancer Effect

The conventional application of Streblus asper in folk medicine and is now being explored for its anticancer properties. Research suggests that its bioactive compounds exhibit cytotoxic effects against various cancer cell lines. S. asper extracts have been found to cause cancer cells to go through programmed cell death, or apoptosis, by triggering mitochondrial and caspase pathways. Bioactive compounds like flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids present in S. asper have shown cytotoxic effects on cancer cells, slowing their growth and proliferation. Some studies suggest that S. asper inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion, reducing the ability of tumours to spread Certain phytochemicals in S. asper have been identified to stop splitting of cancer cells at checkpoints, preventing tumour progression. Phytol, α-farnesene, trans farnesyl acetate, caryophyllene, and trans-trans-α-farnesene were found to be 45.1%, 6.4%, 5.8%, 4.9%, and 2.0% of the volatile oil in fresh S. asper leaves that were hydro distilled. Significant anti-cancer effects were demonstrated by this oil in P388 (mouse lymphocytic leukaemia) cells (ED50 << 30 μg/mL). When combined with cyclophosphamide (CTX), the leaf and floral extract of S. asper dramatically increased the anticancer activity in P388 cells. A cardiac glycoside called (+)-Strebloside was extracted from S. asper's stem bark. By blocking Na+/K+-ATPase, triggering caspase signalling, and destroying PARP (Poly) ADP-ribose polymerase, cell cycle progression occurs during the G2 phase. it was discovered to decrease the growth of ovarian cancer cells. Furthermore, via activating ERK pathways, (+)-strebloside also effectively suppresses the production of mutant p53.It also inhibits the NF-κB activity of human ovarian cancer cells (Ren et al., 2017). It has been demonstrated that the hydroxy groups C-5 and C-14, the C-3 sugar unit, and the C-10 formyl groups are what cause (+)-strebloside to be cytotoxic to cancer cells. In addition, another cardiac glycoside is strophanthidin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→46-deoxy-β-D-allopyranoside).5βH-16β-acetylkamaloside and -acetylkamaloside, together with mansonin-19-carboxylic acid that was obtained from the root of S. asper, showed significant cytotoxicity in A549 cells (IC50:0.01). S. asper leaves' methanolic extracts and fractions showed antiproliferative activity against the human cancer cell lines A-549, Hep-G2, and K-562, according to (Rawat et al., 2018). Similarly, there was significant anti-tumour activity in the methanolic extract of S. asper stem bark. Through antioxidant action, according to (Kumar et al. 2013), it prolonged the survival of Swiss albino mice given an injection of Ehrlich ascites cancer in albino Swiss mice with Dalton's ascitic lymphoma, the ethyl acetate portion of the methanolic extract of S. asper bark most likely had an antitumor activity. Mice were injected with lymphoma cells intraperitoneally, and the following day, nine parameters, including tumour weight and volume, were implanted with extract from plants (200 and 400 mg/kg). The haemoglobin count, white blood cells, and red blood cells were among the tissue antioxidant, biochemical, and haematological parameters that the plant extract corrected (Rastogi et al.,1990)

Antineoplastic Effect

S. asper extracts have been shown to activate apoptotic pathways by increasing caspase activity and mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cancer cell death (Rastogi et al.,1990). The plant’s bioactive compounds interfere with cell cycle progression, preventing uncontrolled cell division in neoplastic cells. It has been shown that Streblus asper possesses anticancer properties. It was shown that S. asper stem bark extracts in methanol and dichloromethane were KB cytotoxic. Strebloside and mansonin, two cytotoxic cardiac glycosides were identified, is played considerable activity in the KB cell culture system, with comparable ED50 values of 0.035 and 0.042 mg/ml. If an isolate's ED50 is less than 4 mg/ml, (Fiebig et al.,1985). It is considered active in this system. Using P388 (mouse lymphocytic leukaemia) cells for cytotoxicity primary evaluation analyses, the volatile oil extracted from fresh S. asper leaves demonstrated significant antineoplastic activity (ED50 <30 mg/ml); however, it exhibited no discernible antioxidant properties in a DPPH radical scavenging experiment (IC50 values > 100 mg/ml) (Phutdhawong et al.,2004).

Anti-Allergic Effect

Allergic reactions are primarily triggered by histamine release from mast cells. Studies suggest that extracts from Streblus asper may inhibit mast cell degranulation, reducing histamine release and alleviating allergy symptoms. Allergies often cause inflammation in the skin, airways, or gastrointestinal tract. S. asper contains flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids that exhibit strong anti-inflammatory activity, potentially reducing allergic inflammation (Prasant et al.,2021). Some compounds in S. asper may help regulate immune responses, preventing excessive reactions to allergens. It may modulate cytokine production, which plays a role in allergic conditions like asthma and dermatitis. Significant anti-allergic action was shown by Streblus asper in pharmacological models. Mast cell stabilizing potential and anti-PCA (passive cutaneous anaphylaxis) in rats were studied. The typical medication in this paradigm is the anti-allergic medication disodium cromoglycate (DSCG). Mice treated with 60–74% of Streblus asper (50–100 mg/kg, p.o.) had anti-PCA activity (Palmbo et al.,2011). In addition, it demonstrated dose-dependent (50–200 mg/kg, p.o.) anti-PCA effectiveness (56–85%) in rats. Rats given 10 mg/kg of mast cell stabilizing activity injection for four days demonstrated 62% protection against degranulation brought on by comp. 48/80. In rats that were already sensitive to egg albumin, S. asper showed 67% protection against degranulation caused by the protein. These results were like DSCG’s (Amarnath et al.,2002).

Antimicrobial Effect

S.asper exhibits strong antimicrobial properties due to its bio active compounds, which act against bacteria, fungi and viruses. It inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis, disrupts bacterial enzymes and DNA replication. Also work against pathogen fungus, damages fungal cell membranes. Inhibits ergosterol synthesis, essential for fungal survival (Limsong et al.,2004). To determine the bactericidal activity of S. asper leaf extract, numerous investigations were carried out. Ethanol extracts from the stems and leaves of this plant have been found to inhibit the development of streptococcus variants (Triratana et al.,1987) (Wongkham et al.,2001) (Taweechaisupapong et al.,2005).

Neuroprotective Effect

Refers to protecting neurons from damage or degeneration, which can occur in various neurodegenerative illnesses, which include Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and others. decreases inflammation, oxidative stress, or apoptosis of neurons (cell death). Example: By preventing neuronal damage, antioxidants such as resveratrol can have neuroprotective properties. Anti Parkinson effect S.asper has shown neuroprotective potential, which may be beneficial for Parkinson's illness. This neurodegenerative condition is brought on by the death of dopaminergic neurons in the brain’s substantia, leading to motor dysfunction and cognitive impairment. That can counteract oxidative stress, a major contributor to the degradation of dopaminergic neurons (Rastogi et al., 1990). The anti-Parkinson effectiveness of S. asper leaf extract is demonstrated by the MPTP-induced sickness model in C57BL/6 mice and H2O2-produced ROS in SK-N-SH cells. The results shown that leaf extract reverses the functional effects and has antioxidant capability. Cognitive and motor abilities were seen in C57BL/6 mice given MPTP. In HT22 neuron in the hippocampus the ethanolic extracts of S. asper leaves demonstrated beneficial benefits against glutamate-induced toxicity in a dose-dependent way (Singsai et al., 2015). Additionally, Glutamate, a stimulating amino acid whose excessive activation results in cell death and neurological dysfunction, caused oxidative stress that the extract was able to reduce. Furthermore, the extract may lower intracellular ROS concentration in a dose-dependent pattern, shielding the cells from ROS-mediated cytotoxicity. Interestingly, the mRNA and protein analysis verified that These initiatives were caused by the Nrf2-mediated mechanism within the cells. Additionally, the extract's basic and neutral fractions demonstrated a dose-dependent cholinesterase inhibitory effect, suggesting a possible decrease in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Effect: Streblus asper leaf extract at 200, 400, and 800 mg/kg enhanced memory test scores in zebrafish with scopolamine-induced memory impairments, a model for Alzheimer's disease. Specifically, treated fish exhibited increased latency times in inhibitory avoidance tests, indicating enhanced fear memory retention (Palmbo et al.,2011) These results suggest that the extract may attenuate memory impairments related to Alzheimer's disease.

Anti Diabetic Effect

Streblus asper has been studied for its antidiabetic potential due to its capacity to improve insulin sensitivity while decreasing blood sugar levels. In diabetic rats, methanol and aqueous extracts of S. asper bark and leaves drastically lowered blood glucose levels. The extract from the bark was particularly potent, reducing glucose levels by up to 70% in 21 days. Studies show that compounds in S. asper enhance insulin secretion and sensitivity, aiding glucose uptake in cells. Diabetes increases oxidative stress, leading to complications. S. asper extracts contain flavonoids and phenolics that act as antioxidants, protecting pancreatic beta cells (Rahman et al.,2014) Treatment with S. asper extracts reduced bad cholesterol (LDL) and increased good cholesterol. The petroleum ether extract of S. asper leaves in diabetic rats showed anti-diabetic properties and possible regulation of peripheral glucose use. After 30 days of the extract's treatment, diabetic rats' The blood sugar levels during fasting were lowered, and their action of gluconeogenic and glycolytic enzymes, Insulin levels and glycogen content were recovered. The existence of apiol, that provides the petroleum ether extract its anti-diabetic qualities, was discovered by analysis (Choudhury et al., 2012).

Antioxidant Effect

Streblus asper, a plant native to Southeast Asia, has demonstrated significant antioxidant properties in various preclinical studies. These features are due to its rich phytochemical composition which includes lignans, flavonoids, and phenolics, which support its capacity to scavenge free radicals and regulate enzymes linked to oxidative stress (Rastogi et al., 1990).Ethanolic extracts of S. asper leaves and bark have shown potent antioxidant activity in DPPH assays has IC₅₀ values that were like that of common antioxidants like ascorbic acid, with 1 µg/mL for leaves and 10 µg/mL for bark. In vitro studies using neuronal cell lines (e.g., SK-N-SH) demonstrated that S. asper extracts could reduce the amounts of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced on by oxidative stressors like hydrogen peroxide, suggesting potential neuroprotective effects an imbalance between the body's antioxidants and free radicals leads to oxidative stress (Phutdhawong et al., 2004). Free radicals can harm liver cells, which can result in conditions include liver fibrosis, cirrohosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The antioxidants in it, particularly the flavonoids and phenolic compounds, scavenge free radicals and lower lipid peroxidation, which is a major cause of damage to liver cells (Ibrahim et al.,2013) Antioxidant chemicals, which are thought to be present in streblus asper, are crucial in shielding the liver from oxidative damage brought on by free radicals. In diseases where oxidative stress is a contributing component, such as cirrhosis or fatty liver disease, this could be helpful.

Anti-Inflammatory Effects

In animal models ((for example, rats with paw edema brought on by carrageenan), ethanolic extracts of Streblus asper leaves significantly reduced inflammation in a way that is depending on dosage. Strong therapeutic potential was shown by the extract's effects, which were comparable to those of common anti-inflammatory medications like diclofenac. In vitro studies using RAW 264.7 macrophage cells have demonstrated that Extracts from S. asper inhibit the expression of important inflammatory genes (Sripanidkulchai et al.,2009), such as Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), an enzyme that produces prostaglandins, which are important mediators of pain and inflammation. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) – Produces nitric oxide, which contributes to inflammation and tissue damage. Chronic inflammation is a hallmark of many liver diseases, including viral hepatitis and liver fibrosis. It has been shown that S. asper lowers the activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are essential to liver inflammation, including TNF-α and IL-6. S. asper can lessen inflammation and limit the severity of liver damage by regulating the immune response (Okoro et al.,2021) One of the most exciting potential benefits of Streblus asper is its ability to promote liver cell regeneration. Studies suggest that S. asper extracts can stimulate the production of growth factors involved in the repair and regeneration of liver tissue, thus aiding in the recovery from liver damage. Higher levels of liver enzymes like aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are frequently seen in conjunction with liver damage. Damage to the liver cells causes these enzymes to be released into the bloodstream. According to certain research, S. asper extracts can lower ALT and AST levels, which may have a protective effect on liver cells (Prakash et al., 1992) (Shikov et al., 2017).

Anti-Ulcer Effect

Streblus asper has shown promising anti-ulcer properties in experimental studies. Its gastroprotective effects are attributed to its ability to reduce gastric acid secretion, enhance mucosal defence mechanisms, and exhibit antioxidant activity (Chen et al.,2017). Extracts of S. asper have been reported to reduce gastric acid output, preventing excessive acidity that can lead to ulcer formation. The plant's bioactive substances, which enhance the gastric mucosal barrier, include flavonoids and tannins (Nile et al.,2016) (Shah et al., 2022). It promotes mucus production, which protects the stomach lining from ulcerogenic agents like alcohol, stress, and NSAIDs. Animal studies have demonstrated that extracts of S. asper provide significant protection against experimentally induced gastric ulcers. These studies show a reduction in ulcer index, improved healing rates, and restoration of gastric mucosal integrity (Rastogi et al.,1990).

Anti-Hepatitis Effect

Streblus asper has been traditionally used in herbal medicine for liver-related ailments. Hepatoprotective suggests it helps protect liver cells from harm brought on by viruses, toxins, or other stresses, such as hepatitis viruses (Rawat et al.,2018) Free radicals are obtained, and oxidative stress—a major contributor to liver cell damage—is decreased especially during hepatitis. Reduces inflammation of liver tissues, which can help mitigate damage in viral hepatitis. Some studies suggest that compounds in S. asper may help in modulating immune responses, potentially beneficial in viral infections like hepatitis (Chen et al.,2012). In animal models, Streblus asper extracts have shown: Reduced liver enzyme levels which are elevated during liver damage.Improved histopathology of liver tissues, suggesting a reversal or prevention of liver damage. Some studies have explored its effects against chemically induced hepatitis, such as with carbon tetrachloride (CCl₄) in rats (Prakash et al.,1992) .

Anti-Aging Effect

It has been shown that Streblus asper's leaves, bark, and roots contain potent antioxidants called flavonoids, phenolic compounds, and alkaloids. Free radicals are chemicals that lead to oxidative stress and hasten cellular aging; antioxidants assist in their neutralization. By reducing oxidative damage, the plant may promote cell longevity, avoid age-related disorders, and postpone the aging of the skin (Prasansuklab et al., 2017) (Nag et al.,2022). By increasing the survival of the nematode larvae through the Mitogen-mediated activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and the transcription factor SKN-1 (ortholog of mammalian Nrf-2), the ethanolic extract of S. asper leaves showed anti-aging activity in the simulated nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (Prasanth et al., 2021).

Anti-Depressant Effect

The medicinal herb S. asper has several pharmacological activities, including potential antidepressant effects. While not as extensively studied as conventional antidepressants, some preclinical studies have suggested that extracts of Streblus asper may exert antidepressant-like activity (Choudhury et al.,2012). Modulation of neurotransmitters: It may influence serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine pathways, which are commonly targeted by antidepressant drugs. Its antioxidant effects could decrease the brain's oxidative stress, which has been connected to depression. In rodent models, tests like the Tail Suspension Test (TST) and Forced Swim Test (FST) have been performed to assess behaviour like that of antidepressants. In these tests, it has been demonstrated that methanolic or ethanolic leaf extracts of Streblus asper significantly shorten immobility time, indicating an antidepressant effect (Nazeen et al.,1989).

Insecticidal Effect

Streblus asper, an indigenous South and Southeast Asian medicinal herb, has demonstrated strong insecticidal properties due to its bioactive compounds like flavonoids, tannins, saponins, and alkaloids. Extracts from the leaves or bark can kill the larvae of mosquitoes like Aedes aegypti and Culex quinquefasciatus, which are vectors for dengue and filariasis (Atal.,1969). The plants compounds interfere with insect molting and growth, preventing them from reaching adulthood. Reduces Feeding: It has an antifeedant effect, making insects avoid plants or grains treated with its extract. Nervous System Disruption: Some compounds may affect the insect’s nervous system, though this is still under study. Streblus asper stem bark extracts on Dysdercus cingulatus showed an LC50 value of 5.56 μg for crude methanol extract. Water, n-BuOH, n-hexane, and chloroform were used to fractionate the methanolic extract; each of these showed progressively higher orders of insecticidal activity. The most effective insecticidal action was shown by the fractions of chloroform, chloroform/EtOAc (1:1), and EtOAc which were partially purified using silica gel column chromatography and tested for insecticidal activity. An LC50 value of 1.8 μg suggested that the chloroform fraction had the strongest insecticidal activity. The greater levels of polyphenolic chemicals in the fractions were thought to be responsible for their insecticidal effect (Hashim.,2003).

Discussion

S. asper, commonly referred to as squint or misalignment of the eyes, is primarily an ocular condition, but it can have profound effects on other aspects of good health, leading to a variety of complications in different organ systems. While the connection may not be immediately apparent, S. asper is associated with various diseases, including toothache, liver damage, and jaundice, each of which can be exacerbated by or linked to the underlying visual misalignment (Ibrahim et al.,2013). In individuals with S. asper, the brain must work harder to process visual information, often resulting in eye strain, headaches, and a misalignment in body posture, all of which can contribute to the onset of a toothache (Neekhra et al.,2017). The persistent tension in the head and neck region due to visual stress can lead to muscle spasms in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), which is the joint connecting the jaw to the skull. This can result in jaw discomfort and mimic the sensation of a toothache, even if there are no direct dental issues (Chen et al.,2012). In some cases, the uneven alignment caused by S. asper could also influence the development of dental issues over time, such as misaligned teeth or uneven bites, further exacerbating the potential for jaw and tooth pain (Rastogi et al.,1990). Furthermore, S. asper can be linked to stress and anxiety, which are known contributors to liver damage. Chronic stress, often a byproduct of living with a misaligned vision that disrupts normal daily activities, triggers the body’s fight-or-flight response, leading to the overproduction of stress hormones like cortisol (Rastogi and Dhawan.,1990) (Limsong et al.,). Long-term exposure to these stress hormones can have detrimental effects on the liver, which is responsible for detoxifying the body (Gaitonde et al., 1964) (Li et al.,2008). This prolonged stress can lead to liver dysfunction, inflammation, or even more severe conditions such as fatty liver disease. Additionally, the strain from constant visual imbalance may result in lifestyle choices that exacerbate liver health, including poor dietary habits or irregular sleep patterns, further affecting liver function. The connection between S. asper and jaundice is similarly rooted in the systemic impact of prolonged stress and liver dysfunction when the liver is unable to properly process and eliminate bilirubin, it can lead to jaundice, which is characterized by a yellowing of the skin and eyes caused by a buildup of bilirubin (Das and Beuria.,1991). In individuals with chronic stress or liver damage caused by untreated S. asper, the liver’s inability to process waste products efficiently can result in the accumulation of bilirubin, leading to jaundice. This can create a cycle where visual misalignment, and the stress associated with it not only cause ocular strain but also lead to systemic health issues affecting the liver and jaundice (Barua et al., 1968). The misalignment of the eyes can also be an indicator of broader neurological or developmental issues, which might affect other organs and their functions, including the liver (Rawat et al.,2018) ;(Shah et al., 2022). Moreover, in some cases, individuals with untreated strabismus may neglect their health or fail to seek appropriate treatment for symptoms, including those that could affect the liver, leading to the progression of liver damage or jaundice. Overall, S. asper, while initially seen as an isolated ocular disorder, can have a far-reaching impact on overall health, influencing not just visual well-being but contributing to complications in areas such as dental health, liver function, and the development of jaundice, all of which highlight the interconnectedness of bodily systems. This emphasizes the importance of early diagnosis and treatment for Strabismus Asper to not only prevent vision-related issues but to also mitigate the risk of secondary health problems that could arise from the chronic stress and strain it places on the body.

Conclusion

Streblus asper shows considerable promise as a natural remedy for liver disorders, supported by both traditional usage and preliminary scientific findings. The plant's long-standing application in treating liver-related conditions such as jaundice, liver enlargement, and inflammation, coupled with its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, underscores its potential hepatoprotective benefits. Traditional medicine systems have utilized various parts of the plant, including its bark, roots, and leaves in different forms like teas and decoctions, suggesting a broad cultural acceptance and trust in its therapeutic efficacy. Scientific studies, particularly those involving animal models, have begun to substantiate these traditional claims, highlighting Streblus asper's ability assist in reducing inflammation, encourage liver regeneration, and shield the liver from oxidative damage. However, despite these promising results, there remains a need for more robust research to validate the plant's hepatoprotective properties, particularly through well-designed human clinical trials. Much of the current evidence comes from in vitro studies and animal experiments, which while informative, cannot fully replicate the complexity of human liver diseases. Additionally, the bioactive compounds responsible for the plant’s therapeutic effects are still not fully identified, and understanding these components in greater detail could provide insights into their ways of action and possible advantages when combined with additional therapies. The future scope of research on Streblus asper lies in several key areas. First, to establish its safety, utility, and appropriate dosage for treating issues with the liver, extensive clinical trials in humans are necessary. These studies would help establish clear therapeutic guidelines and allow for the integration of S. asper into evidence-based clinical practice. Secondly, isolating and identifying the specific bioactive compounds in Streblus asper could lead to the development of standardized extracts or formulations for consistent therapeutic use. Further pharmacological research would also help clarify its mechanisms of action at the molecular level, including how it modulates oxidative stress, inflammation, and liver regeneration. Additionally, studies exploring potential interactions with other drugs or herbal remedies could provide valuable insights into its safe integration into multi-modal treatment plans. The increasing interest in plant-based therapies for liver diseases, combined with the growing acceptance of integrative medicine, provides an exciting opportunity for Streblus asper to play a role in modern hepatology. However, continued collaboration between traditional healers, ethnobotanists, pharmacologists, and clinical researchers is vital to bridge the gap between historical knowledge and contemporary medical practice. If further studies confirm the therapeutic potential of Streblus asper, it may prove to be a helpful tool in the treatment of liver diseases, offering a secure and simple substitute for the medications used today.

References

- Aeri, V., Alam, P., Ali, M., & Ilyas, U. K. (2012). Isolation of new aliphatic ester linked with δ-lactone cos-11-enyl pentan-1-oic-1, 5-olide from the Roots of Streblus asper Lour. Indo Global J. Pharm. Sci, 2(2), 114-120.

- Alam, M. K. (1992). Medical ethnobotany of the Marma tribe of Bangladesh. Economic Botany, 330-335. [CrossRef]

- Amarnath Gupta, P. P., Kulshreshtha, D. K., & Dhawan, B. N. (2002, January). Antiallergic activity of Streblus asper. In Proceedings of the XXXIV Annual conference of the Indian Pharmacological Society. Nagpur (pp. 211-26).

- Anand, U., Tudu, C. K., Nandy, S., Sunita, K., Tripathi, V., Loake, G. J.,... & Proćków, J. (2022). Ethnodermatological use of medicinal plants in India: From ayurvedic formulations to clinical perspectives–A review. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 284, 114744. [CrossRef]

- Anbari, K., Hasanvand, A., Andevari, A. N., & Abbaszadeh, S. (2019). Concise overview: A review on natural antioxidants and important herbal plants on gastrointestinal System. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology, 12(2), 841-847. [CrossRef]

- AX, V. (1964). Chemical and pharmacological study of root bark of Streblus asper Linn. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 18, 191-199.

- Baranwal, A. K., Kumar, P., & Trivedi, V. P. (1978). A preliminary study of Streblus asper Lour. (shakhotak) as an anti-lymphoedematous agent. Nagarjun, 21, 22-4.

- Bhatt, N. (1998). Ayurvedic drug industry (challenges of today and tomorrow). In Proceeding of the first national symposium of ayurvedic drug industry organised by (ADMA). Ayurvedic, New Delhi sponsored by Department of Indian System of Medicine of HOM, Ministry of Health, Govt of India.

- Chamariya, R., Raheja, R., Suvarna, V., & Bhandare, R. (2022). A critical review on phytopharmacology, spectral and computational analysis of phytoconstituents from Streblus asper Lour. Phytomedicine Plus, 2(1), 100177. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R. K., Fatma, N., Murthy, P. K., Sinha, P., Kulshrestha, D. K., & Dhawan, B. N. (1992). Macrofilaricidal activity of the stembark of Streblus asper and its major active constituents. Drug Development Research, 26(1), 67-78. [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A. S., Kapoor, V. K., Mukhopadhyay, R., & Mandeep Singh, M. S. (1990). Constituents of Streblus asper.

- Chen, G. G., & Lai, P. B. (Eds.). (2012). Novel apoptotic regulators in carcinogenesis.

- Chen, H., Li, J., Wu, Q., Niu, X. T., Tang, M. T., Guan, X. L.,... & Su, X. J. (2012). Anti-HBV activities of Streblus asper and constituents of its roots. Fitoterapia, 83(4), 643-649. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. L., Ren, Y., Ren, J., Erxleben, C., Johnson, M. E., Gentile, S.,... & Burdette, J. E. (2017). (+)-Strebloside-induced cytotoxicity in ovarian cancer cells is mediated through cardiac glycoside signaling networks. Journal of natural products, 80(3), 659-669. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M. K., Venkatraman, S., & Upadhyay, L. (2012). Phytochemical analysis and peripheral glucose utilization activity determination of Steblus asper. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine, 2(2), S656-S661. [CrossRef]

- Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (India). (1959). The Wealth of India: Raw Materials (Vol. 5). Council of Scientific and Industrial Research.

- DAS, A. K., PARUL, R., ISLAM, M. M., GHOSH, A. C., & ALAM, M. J. (2021). Investigation of analgesic, antioxidant, and cytotoxic properties of the ethanolic extract of streblus asper (roots). Asian J Pharm Clin Res, 14(5), 126-131. [CrossRef]

- Das, M. K., & Beuria, M. K. (1991). Anti-malarial property of an extract of the plant Streblus asper in murine malaria. [CrossRef]

- Deep SK, Patra B, Baral A, Nayak Y, Pradhan SN (2022). Impact of global climate change on extremophilic diversity. Journal of east china university of science and technology. 65 (3): 842-853.

- Deep SK, Patra B, Mohanta AK, Ekka RK, Sethi BK, Behera PK, Pradhan SN. (2023). Role of Critical contaminants in ground water of Kalahandi district of Odisha and their health risk assessment. Ann. For. Res. 66(1): 3963-3981.

- Fiebig, M., Duh, C. Y., Pezzuto, J. M., Kinghorn, A. D., & Farnsworth, N. R. (1985). Plant anticancer agents, XLI. Cardiac glycosides from Streblus asper. Journal of natural products, 48(6), 981-985. [CrossRef]

- Gochhi SK, Patra B, Dey SK. (2023). Comparative study of bioactive components of betel leaf essential oil using GCMS analysis. Gradiva review journal. 9(9): 08-20.

- Hashim, M. S., & Devi, K. S. (2003). Insecticidal action of the polyphenolic rich fractions from the stem bark of Streblus asper on Dysdercus cingulatus. Fitoterapia, 74(7-8), 670-676. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N. M., Mat, I., Lim, V., & Ahmad, R. (2013). Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of Streblus asper leaves from various drying methods. Antioxidants, 2(3), 156-166. [CrossRef]

- Kandali, R., & Konwar, B. K. (2012). Isolation and Characterization of Active Compound from Stem Bark of Streblus asper. Indian Journal of Agricultural Biochemistry, 25(2), 157-159.

- Karan, S. K., Mishra, S. K., Pal, D. K., Singh, R. K., & Gunjan Raj, G. R. (2011). Antidiabetic effect of the roots of Streblus asper in alloxan-induced diabetes mellitus.

- Khanikor, S. B., Boruah, G., Salam, R., Tashi, L., & Kumari, S. (2024). Antioxidant and Antimicrobial effects of the Streblus asper Lour.

- Khemka A, Patra B, Pradhan SN (2020) Revisiting the migrants health and prosperity in Odisha: A sustainable perspective. Covid 19, Migration and sustainable development. ISBN 978-93-89224-65-8, Kunal book publishers and distributors. Editors: Sudhakar Patra, Kabita Kumari Sahu, Shakuntala Pratihary, Ambika Prasad Nanda.

- Kumar, G., Kanungo, S., & Panigrahi, K. (2020). Antimicrobial effects o f Streblus Asper leaf extract: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Pharmacol. Clin. Res, 8, 555740.

- Kumar, R. B., Kar, B., Dolai, N., & Haldar, P. K. (2013). Study on developmental toxicity and behavioral safety of Streblus asper Lour. bark on zebrafish embryos.

- Kumar, R. S., Kar, B., Dolai, N., Bala, A., & Haldar, P. K. (2012). Evaluation of antihyperglycemic and antioxidant properties of Streblus asper Lour against streptozotocin–induced diabetes in rats. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease, 2(2), 139-143. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Huang, Y., Guan, X. L., Li, J., Deng, S. P., Wu, Q.,... & Yang, R. Y. (2012). Anti-hepatitis B virus constituents from the stem bark of Streblus asper. Phytochemistry, 82, 100-109. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhang, Y. J., Jin, B. F., Su, X. J., Tao, Y. W., She, Z. G., & Lin, Y. C. (2008). 1H and 13 C NMR assignments for two lignans from the heartwood of Streblus asper. Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry, 46(5), 497-500.

- Limsong, J., Benjavongkulchai, E., & Kuvatanasuchati, J. (2004). Inhibitory effect of some herbal extracts on adherence of Streptococcus mutans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 92(2-3), 281-289.

- Mahanto R, Behera D, Patra B, Das S, Lakra K, Pradhan SN, Abbas A, Ali SK.(2024). Plant based natural products in cancer therapeutics. Journal of drug Targeting. [CrossRef]

- Meena, A. K., Ilavarasan, R., Perumal, A., Ojha, V., Singh, R., Srikanth, N., & Dhiman, K. S. (2024). Comparative study of stem bark and small branches of Streblus asper and anti-carcinogenic and anti-diabetic activity. International Journal of Ayurveda Research, 5(3), 179-191. [CrossRef]

- Miao, D., Zhang, T., Xu, J., Ma, C., Liu, W., Kikuchi, T.,... & Zhang, J. (2018). Three new cardiac glycosides obtained from the roots of Streblus asper Lour. and their cytotoxic and melanogenesis-inhibitory activities. RSC advances, 8(35), 19570-19579.

- Mohammed, R. M. O., Huang, Y., Guan, X., Huang, X., Deng, S., Yang, R.,... & Li, J. (2022). Cytotoxic cardiac glycosides from the root of Streblus asper. Phytochemistry, 200, 113239. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta AK, Patra B, Sahoo C (2022) Practice and Challenges for municipal solid waste management in Balasore district, Odisha. Chinese Journal of geotechnical Engineering. 44(11): 1-9..

- Mohanta AK, Sahoo C, Jena R, Sahoo S, Bishoyi SK, Patra B, Dash SR, Pradhan B. 2024. Effect of inappropriate solid waste on microplastic contamination in Balasore district and its aquatic environment. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 120 (48), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta YK, Biswas K, Mishra AK, Patra B, Mishra B, Panda J, Avula SK, Varma RS, Panda BP, Nayak D. (2024). Amelioration of gold nanoparticles mediated through Ocimum oil extracts induces reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial instability against MCF-7 breast carcinoma. Royal society of Chemistry. 14, 27816-27830. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta YK, Mishra AK, Nayak D, Patra B, Bratovcic A, Avula SK, Mohanta TK, Murugan K, Saravanan M (2022) Exploring dose dependent cytotoxicity profile of Gracilaria edulis mediated green synthesized silver nanoparticles against MDA-MB-231 breast carcinoma. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 3863138. [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, AK, Patra B, Deep SK, Ali AKI, Pradhan SN, Sahoo C. (2022) Recent advancements in utilization of municipal solid waste for the invention of bioproducts: the framework for low income countries. Journal of east china university of science and technology. 65 (3): 422-465.

- Nag, M., Paul, R. K., Biswas, S., Roy, D., Saha, R., Boral, P.,... & Boral, P. (2022). Extraction and Identification of Phytoconstituent obtained from Streblus as per Lour Root Bark as an Antibacterial Agent. NeuroQuantology, 20(8), 3751-3764.

- Nayak D, Patra B, Behera B (2024). Medicinal Plants of Fakir Mohan University, Odisha. BK Books & Publications. ISBN: 9788196631536.

- Nazneen, P., Singhal, K. C., Khan, N. U., & Singhal, P. (1989). Potential antifilarial activity of Streblus asper against Setaria cervi (nematoda: filarioidea). Indian J Pharmacol, 21, 16.

- Nie, H., Guan, X. L., Li, J., Zhang, Y. J., He, R. J., Huang, Y.,... & Li, J. (2016). Antimicrobial lignans derived from the roots of Streblus asper. Phytochemistry Letters, 18, 226-231. [CrossRef]

- Okoro, N. O., Odiba, A. S., Osadebe, P. O., Omeje, E. O., Liao, G., Fang, W.,... & Wang, B. (2021). Bioactive phytochemicals with anti-aging and lifespan extending potentials in Caenorhabditis elegans. Molecules, 26(23), 7323. [CrossRef]

- Palombo, E. A. (2011). Traditional medicinal plant extracts and natural products with activity against oral bacteria: potential application in the prevention and treatment of oral diseases. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011(1), 680354. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P. N., & Das, U. K. (1990). Therapeutic assessment of Shakhotaka Ghana Vati on Slipada (Filariasis). J Res Ayur Siddha, 11, 31-37.

- Patra B, Gautam R, Priyadarsini E, Paulraj R, Pradhan SN, Muthupandian S, Meena R (2019). Piper betle: Augmented synthesis of gold nanoparticles and its invitro cytotoxicity assessment on HeLa and HEK293 cells. Journal of Cluster Science. 31:133-145. [CrossRef]

- Patra B & Dey SK (2016). A Review on Piper betle L. Journal of Medicinal plants Studies. 4(6): 185-192.

- Patra B (2015). Labanyagada: The Protected red sandal forest of Gajapati district, Odisha, India. International Journal of Herbal Medicine. 3(4): 35-40.

- Patra B, Biswal AK, Behera B (2024). Phytodiversity of Fakir Mohan University, Odisha. FMU Publications. ISBN: 9789361284076.

- Patra B, Das N, Shamim MZ, Mohanta TK, Mishra B, Mohanta YK. (2023) Dietary natural polyphenols against bacterial and fungal infections: An emerging gravity in health care and food industry. Bioprospecting of tropical medicinal plants. Springer nature. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Deep S, Pradhan SN. (2021) Different Bioremediation Techniques for Management of Waste Water: An overview. Recent Advancements in Bioremediation of Metal Contaminants. IGI Global publishing house. DOI: 10.4018/978-1-7998-4888-2, https://www.igi-global.com/book/recent-advancements-bioremediation-metal-contaminants/244607 (Taylor Francis group), Editors: Satarupa Dey, Biswaranjan Acharya.

- Patra B, Deep SK, Rosalin R, Pradhan SN (2022). Flavored food additives on leaves of piper betle L.: A human health perspective. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Dey SK & Das MT (2015). Forest management practices for conservation of Biodiversity: An Indian Perspective. International Journal of Environmental Biology. 5 (4): 93-98.

- Patra B, Gautam R, Das MT, Pradhan SN, Dash SR, Mohanta AK. (2024). Microplastics associated contaminants from disposable paper cups and their consequence on human health. Labmed Discovery. 1(2), 100029. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Meena R, Rosalin R, Singh M, Paulraj R, Ekka RK, Pradhan SN (2022). Untargeted metabolomics in piper betle leaf extracts to discriminate the cultivars of coastal odisha, India. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Mohanty PP, Biswal AK. (2025). Improved Seed Germination Technique for Prosopis Cineraria (L.) Druce: A Rare Sacred Plant of Hindus. Qeios, 2632-3834.

- Patra B, Pal R, Paulraj R, Pradhan SN, Meena R. (2020) Minerological composition and carbon content of soil and water amongst Betel vineyards of coastal Odisha, India. SN Applied Sciences. 2: 998.

- Patra B, Paulraj R, Muthupandian S, Meena R, Pradhan SN (2021). Modern Nanomaterials Extraction and Characterisation Techniques in plant samples and their biomedical potential. Handbook of Research on Nano-Strategies for Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance and Cancer. Pages 400, DOI: 10.4018/978-1-7998-5049-6.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN (2018). A Study on Socio-economic aspects of Betel Vine Cultivation of Bhogarai area of Balasore District, Odisha. Journal of Experimental Science. 9: 13-17.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN (2023) Contamination of Honey: A Human Health Perspective. Health Risks of food additives – Recent developments and Trends in Food Sector (ISBN 978-1-83768-189-1) Intechopen Publishers.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN, Das MT & Dey SK (2018). Eco-physiological Evaluation of the Betel Vine Varieties Cultivated in Bhogarai area of Balasore District, Odisha, India for disease management and increasing crop yield. International Journal of Recent Scientific Research. 9(4): 25822-25828.

- Patra B, Pradhan SN, Paulraj R. (2024) Strategic Urban Air Quality Improvement: Perspectives on public health. Air quality and human health. Springer nature. In: Padhy, P.K., Niyogi, S., Patra, P.K., Hecker, M. (eds) Air Quality and Human Health. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Patra B, Sahu A, Meena R, Pradhan SN (2021) Estimation of genetic diversity in piper betle L. Based on the analysis of morphological and molecular markers. Letters in Applied NonoBioScience. 10(2): 2240-2250.

- Patra B, Sahu D & Misra MK (2014). Ethno-medicobotanical studies of Mohana area of Gajapati district, Odisha. India. International Journal of Herbal Medicine.2(4): 40-45.

- Phutdhawong, W., Donchai, A., Korth, J., Pyne, S. G., Picha, P., Ngamkham, J., & Buddhasukh, D. (2004). The components and anticancer activity of the volatile oil from Streblus asper. Flavour and fragrance journal, 19(5), 445-447. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, K., Deepak, D., Khare, A., & Khare, M. P. (1992). A pregnane glycoside from Streblus asper. Phytochemistry, 31(3), 1056-1057. [CrossRef]

- Prasansuklab, A., Meemon, K., Sobhon, P., & Tencomnao, T. (2017). Ethanolic extract of Streblus asper leaves protects against glutamate-induced toxicity in HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells and extends lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Prasanth, M. I., Brimson, J. M., Sheeja Malar, D., Prasansuklab, A., & Tencomnao, T. (2021). Streblus asper Lour. exerts MAPK and SKN-1 mediated anti-aging, anti-photoaging activities and imparts neuroprotection by ameliorating Aβ in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 6(3), 211-227.

- Rahman, E. T., Raihan, S. Z., Al Mahmud, Z., & Qais, N. (2014). Analgesic activity of methanol extract and its fractions of Streblus asper (Lour.) roots. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research3, 4, 18-24.

- Rastogi, R. P., & Dhawan, B. N. (1990). Anticancer and antiviral activities in Indian medicinal plants: a review. Drug development research, 19(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S., Kulshreshtha, D. K., & Rawat, A. K. S. (2006). Streblus asper Lour. (Shakhotaka): a review of its chemical, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal properties. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 3(2), 217-222.

- Rawat, P., Kumar, A., Singh, T. D., & Pal, M. (2018). Chemical composition and cytotoxic activity of methanol extract and its fractions of Streblus asper leaves on human cancer cell lines. Pharmacognosy magazine, 14(54), 141. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y., Chen, W. L., Lantvit, D. D., Sass, E. J., Shriwas, P., Ninh, T. N., Chai, H. B., Zhang, X., Soejarto, D. D., Chen, X., Lucas, D. M., Swanson, S. M., Burdette, J. E., & Kinghorn, A. D. (2017). Cardiac glycoside constituents of Streblus asper with potential antineoplastic activity. Journal of Natural Products, 80(3), 648-658. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjay P. A REVIEW ON CHEMICAL AND PHARMACOLOGICAL PROFILES OF SHAKHOTAKA (STREBLUS ASPER LOUR.).

- Shah, K., Chhabra, S., & Singh Chauhan, N. (2022). Chemistry and anticancer activity of cardiac glycosides: A review. Chemical Biology & Drug Design, 100(3), 364-375.

- Shahed-Al-Mahmud, M., Shawon, M. J. A., Islam, T., Rahman, M. M., & Rahman, M. R. (2020). In vivo anti-diarrheal activity of methanolic extract of Streblus asper leaves stimulating the Na+/K+-ATPase in Swiss albino rats. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry, 35, 72-79.

- Shikov AN, Tsitsilin AN, Pozharitskaya ON, Makarov VG, Heinrich M. Traditional and current food use of wild plants listed in the Russian Pharmacopoeia. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2017 Nov 21; 8:841. [CrossRef]

- Singsai, K., Akaravichien, T., Kukongviriyapan, V., & Sattayasai, J. (2015). Protective Effects of Streblus asper Leaf Extract on H2O2-Induced ROS in SK-N-SH Cells and MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease-Like Symptoms in C57BL/6 Mouse. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015(1), 970354.

- Sripanidkulchai, B., Junlatat, J., Wara-aswapati, N., & Hormdee, D. (2009). Anti-inflammatory effect of Streblus asper leaf extract in rats and its modulation on inflammation-associated genes expression in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 124(3), 566-570. [CrossRef]

- Swain SK, Barik SK, Das MT, Pradhan SN, Deep SK, Dash SR, Jena R, Patra B. (2023). Multi scale structure and nutritional properties of different millet varieties and their potential health effects. Gradiva review journal. 9(8): 588-607.

- Taweechaisupapong, S., Choopan, T., Singhara, S., Chatrchaiwiwatana, S., & Wongkham, S. (2005). In vitro inhibitory effect of Streblus asper leaf-extract on adhesion of Candida albicans to human buccal epithelial cells. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 96(1-2), 221-226. [CrossRef]

- Triratana, T., & Thaweboon, B. (1987). The testing of crude extracts of Streblus asper (Koi) against Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus salivarius. The Journal of the Dental Association of Thailand, 37(3), 119-125.

- Verma A, Maurya A, Patra B, Gaharwar US, Paulraj R (2019). Extraction of polyaromatic hydrocarbons from the leachate of major landfill sites of Delhi. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education. 16(6):1080-1083.

- Wongkham, S., Laupattarakasaem, P., Pienthaweechai, K., Areejitranusorn, P., Wongkham, C., & Techanitiswad, T. (2001). Antimicrobial activity of Streblus asper leaf extract. Phytotherapy Research, 15(2), 119-121. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).