Submitted:

28 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Non-Coding RNA Coded by the Plant Genomes

BOX1: Different types of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) in plants

2.1. Biogenesis of MicroRNA and Mode of Action in Plants

2.2. Long Non-Coding RNA in Plants

2.2.1. Biogenesis of Long Non-Coding RNA

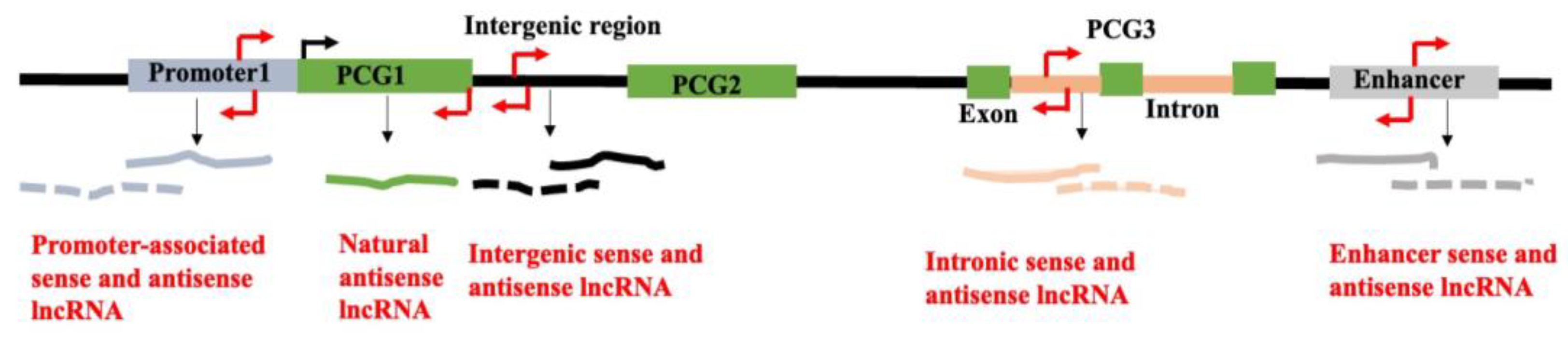

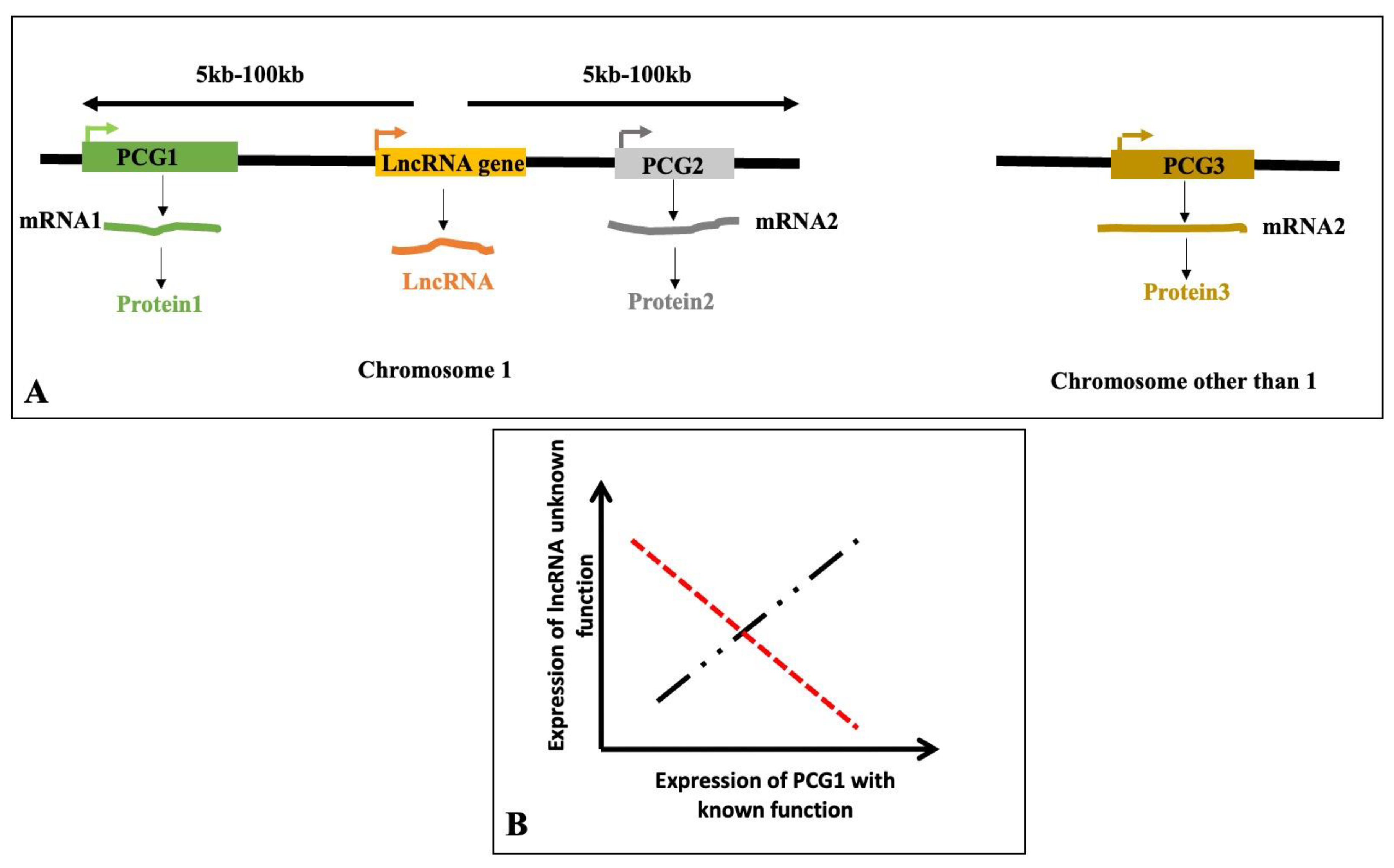

2.3. Classification of lncRNA Based on Their Chromosomal Locations and Direction of Transcription

2.4. Resources for Plant lncRNAs

| Databases | contain | ID |

|---|---|---|

| PLncDB | Information on plant lncRNA in 80 species | https://www.tobaccodb.org/plncdb/ |

| NONCODE | Information on plant as well as animal lncRNA | http://www.noncode.org/ |

| CANTATAdb | Catalog computationally predicted 571,688 lncRNAs in 108 plant species; Papaver somniferum (opium poppy) had the maximum number of lncRNA(24516) followed by Avena sativa (Oat) had 19158 | http://yeti.amu.edu.pl/CANTATA/ |

| GreeNC 2.0 | Over 495 000 annotated lncRNAs from 94 plant and algal species are available in this repository | http://greenc.sequentiabiotech.com/ wiki2/Main_Page |

| PlantNATsDB | 2,146,803 natural antisense transcripts predicted from 70 plant species are catalogued in PlantNATsDB | http://bis.zju.edu.cn/pnatdb/ |

| Plant ncRNA database (PNRD) | More than 25,000 ncRNAs from 150 plant species and 11 distinct kinds are present in PNRD | http://structuralbiology.cau.edu.cn/PNRD |

| LncPheDB | In the database, 203,391 known and predicted lncRNA sequences in 9 species are catalogued. using a unified reference genome annotation | https://www.lncphedb.com/ |

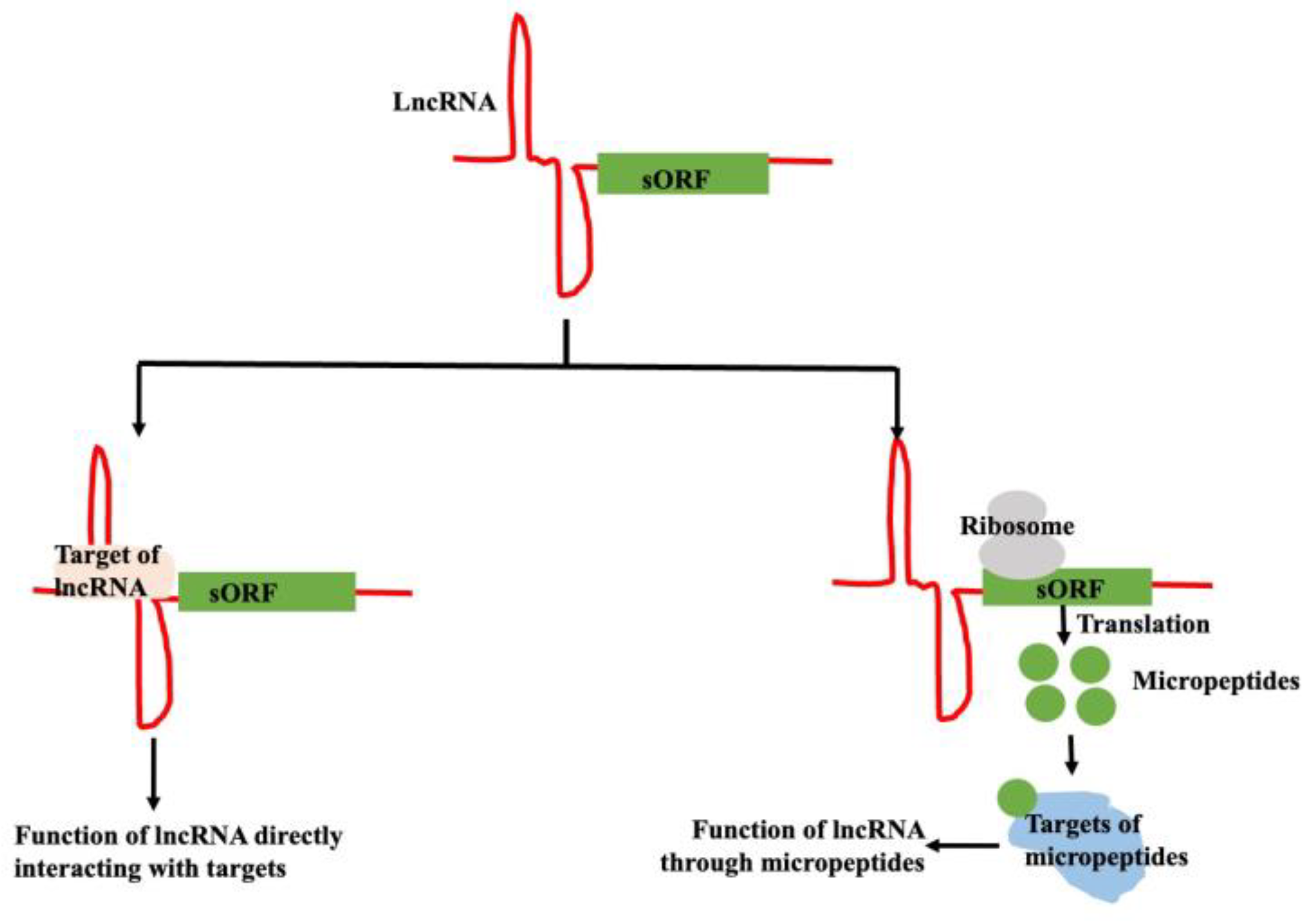

2.5. Micropeptide Coded by the lncRNA in Plants

2.6. Subcellular Localization of Plant lncRNAs

2.7. Tissue-Specific Expression of lncRNAs

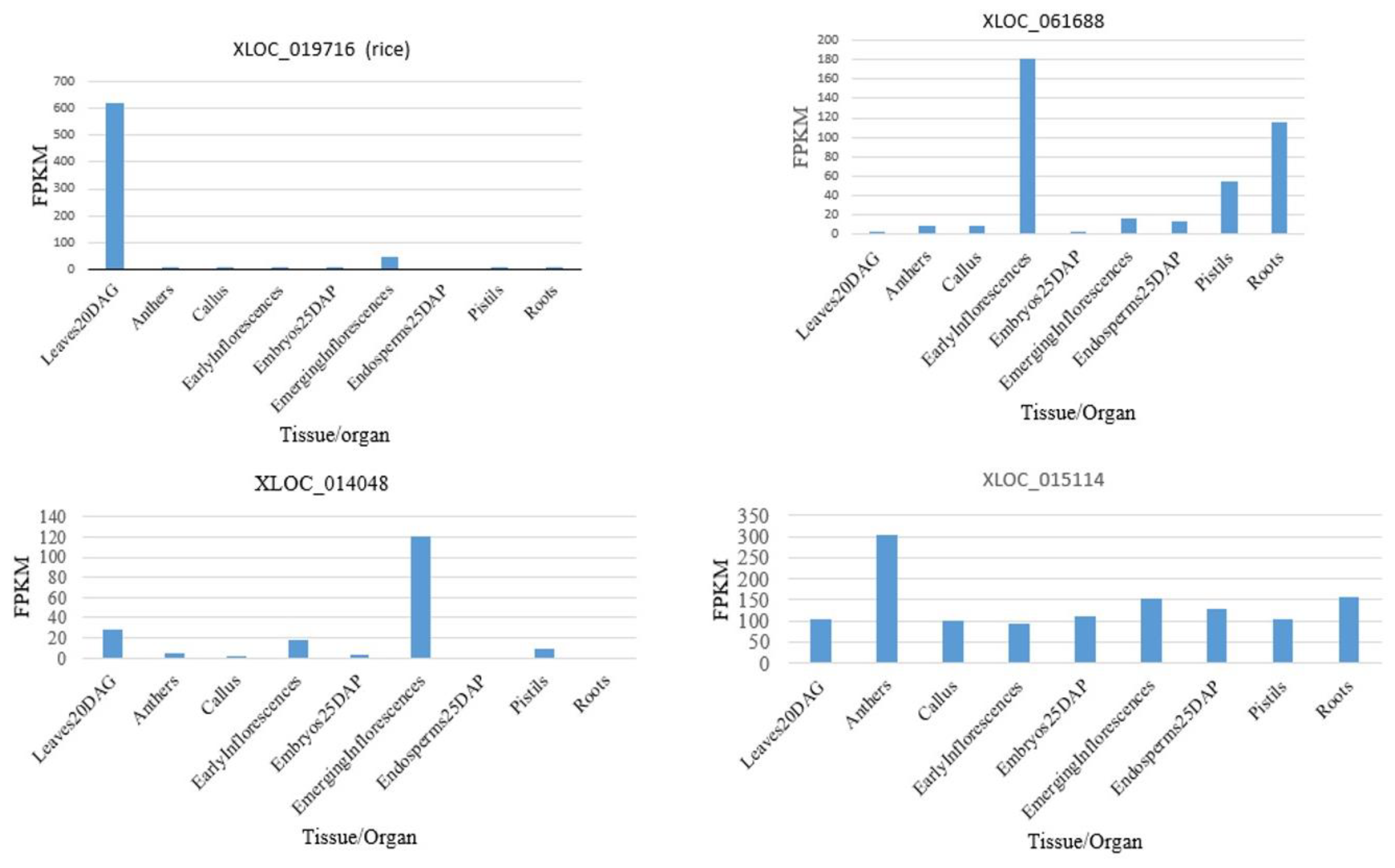

2.8. Epigenetic Regulation of lncRNA in Plants

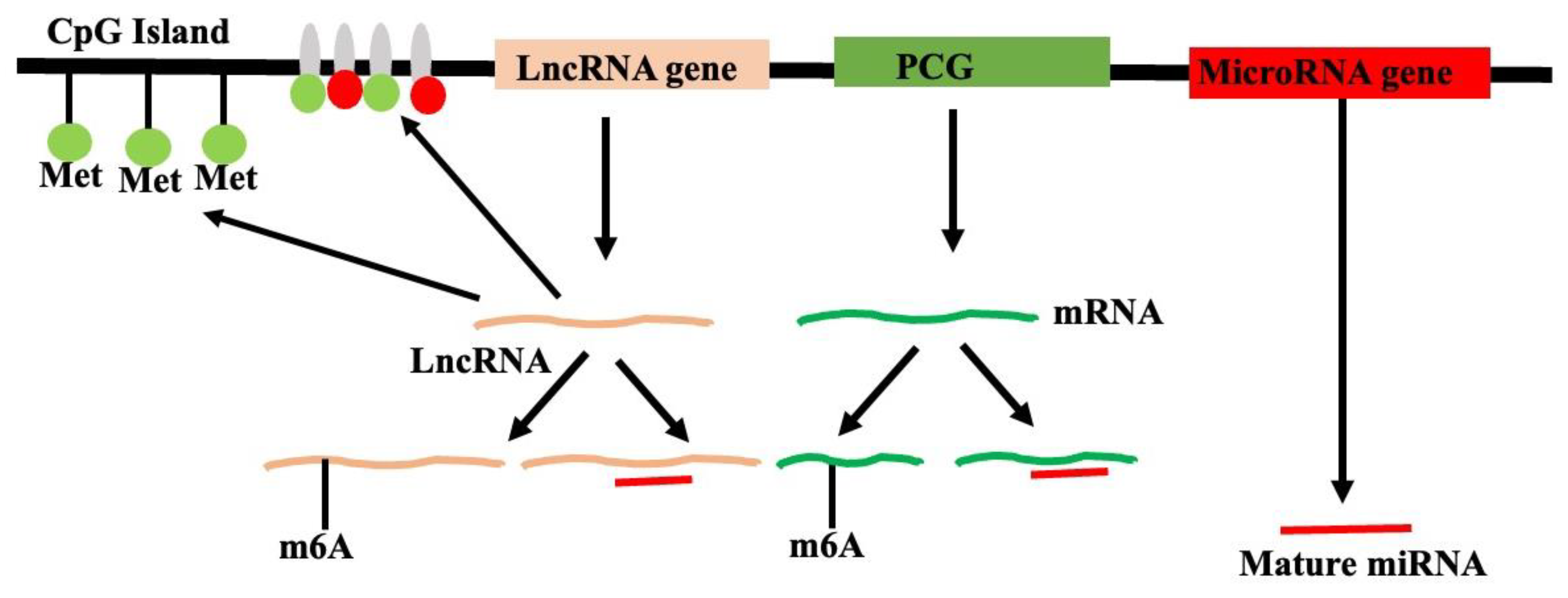

2.8.1. Epigenetic Regulation of lncRNA Expression

2.8.2. LncRNA as Epigenetic Regulators

2.8.3. RNA-Dependent DNA Methylation (RdDM)

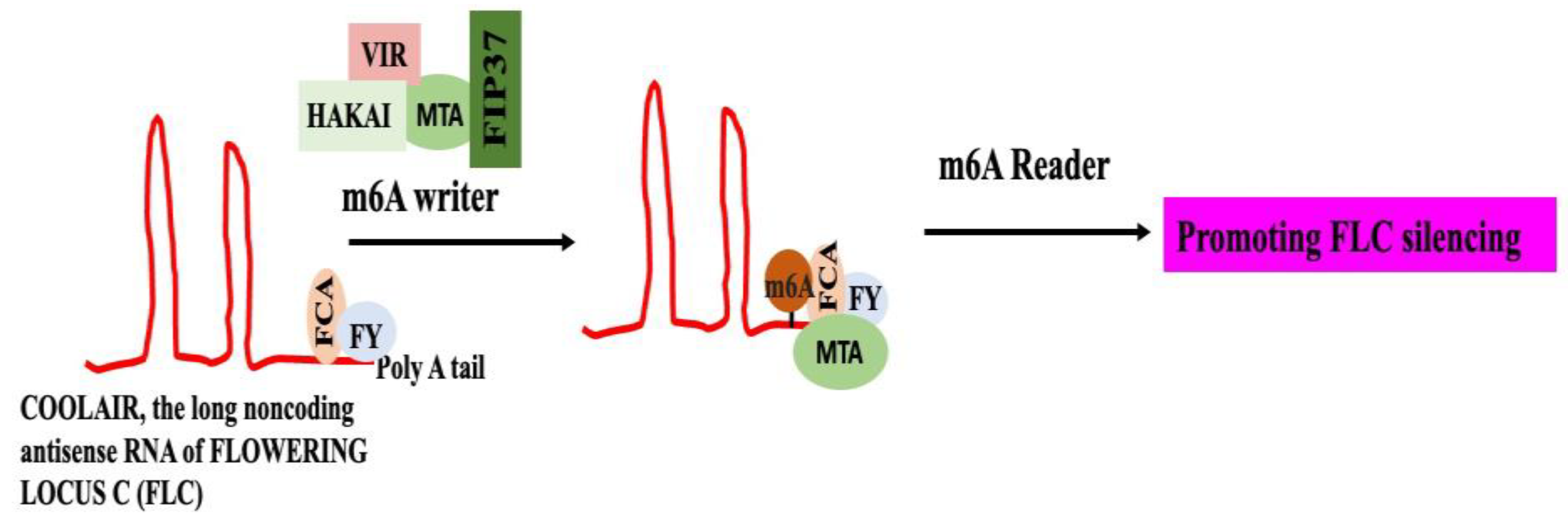

2.8.4. N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) Modification of RNA: Post-Transcriptional Epigenetic Modifications

Functions of Plant lncRNAs

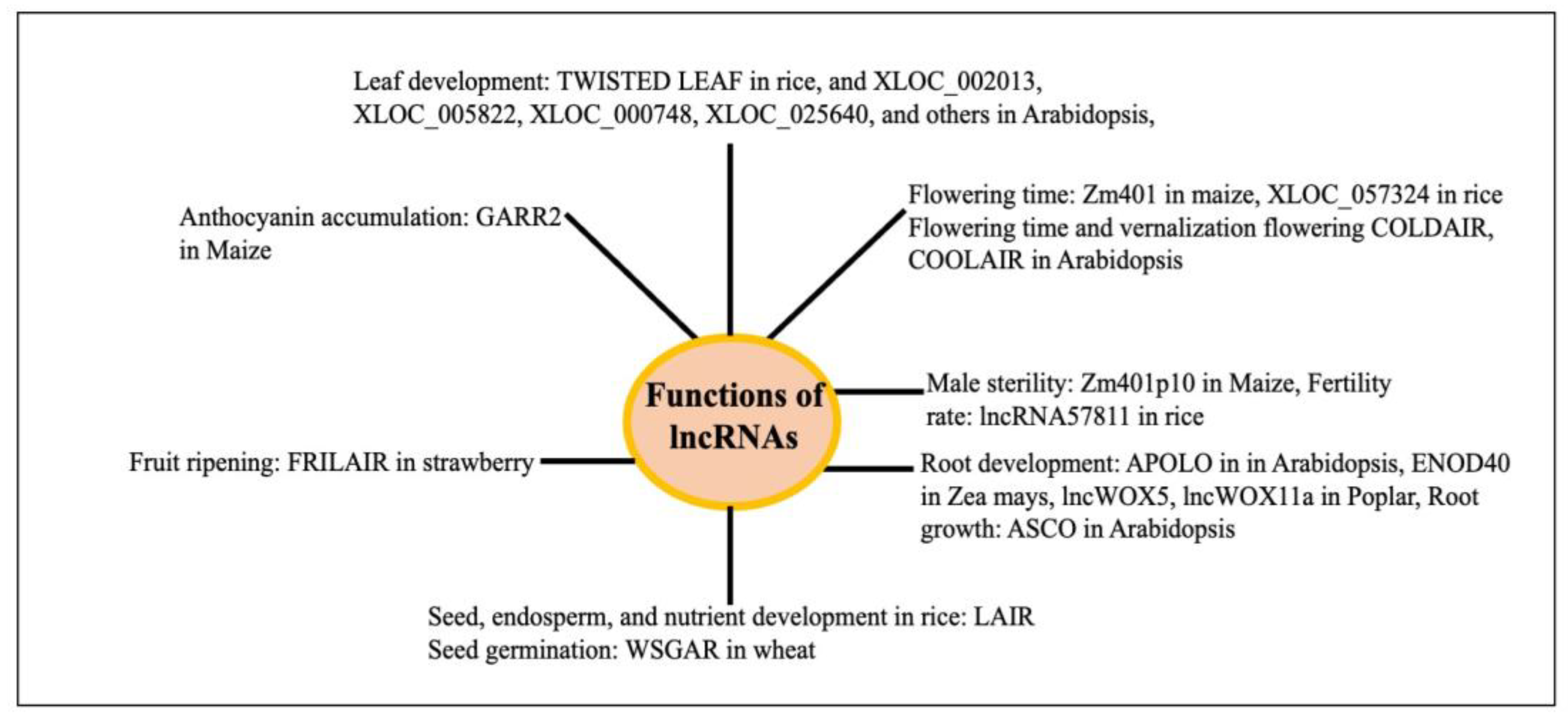

3.1. Physiological Functions of lncRNAs in Plants

Mechanisms of Actions of lncRNAs

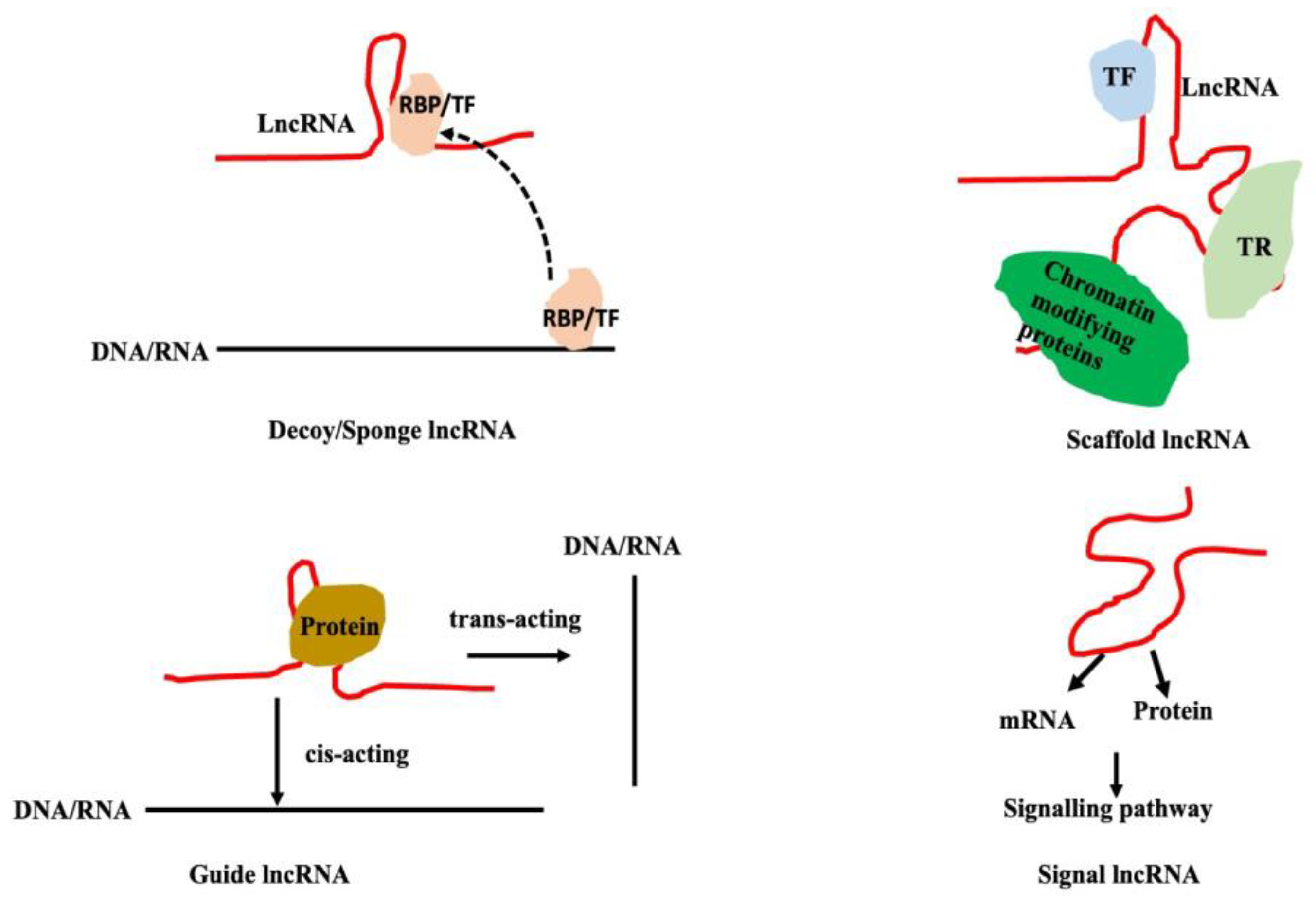

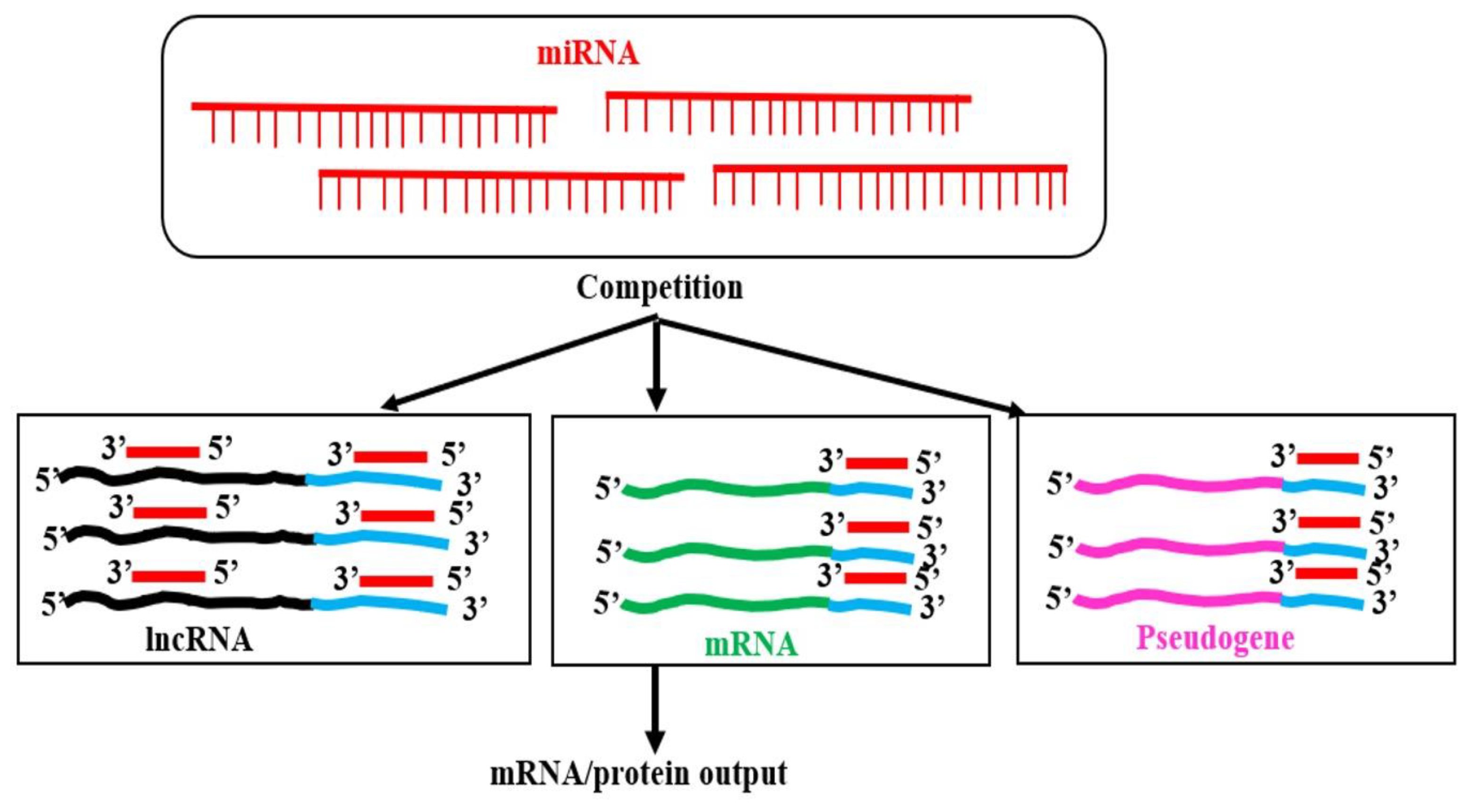

4.1. Long Non-Coding RNA-microRNA Interaction: Decoy/Sponge lncRNAs

4.1.1. LncRNA-Protein Interaction: lncRNAs as Decoy

4.1.2. Long Non-Coding RNA-microRNA Interaction

4.2. Scaffold lncRNAs

4.2.1. LncRNA - DNA/Chromatin Interactions

4.3. Guide lncRNA

4.4. Signal LncRNA

Stress induced lncRNA

5.1. Long Noncoding RNAs in response to abiotic stress

5.2. Role of lncRNA in biotic stress /Plant-Pathogen Interactions mediated through lncRNA

5.2.1. Fungal Pathogens

5.2.2. Viral Pathogens

5.2.3. Bacterial Pathogens

5.2.4. Nematode Pathogens

5.2.5. Insect Pest Interactions

5.3. Immune response mediated through plant lncRNAs

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ncRNA | Non coding RNA |

| PCG | Protein-coding genes |

| lncRNA | Long noncoding RNA |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| CircRNA | Circular RNA |

| rRNAs | ribosomal RNAs |

| tRNAs | transfer RNAs |

| snRNA | small nuclear RNA |

| SnoRNA | small nucleolar RNA |

| siRNAs | small interfering RNAs |

| tRFs | tRNA-derived small RNA fragments |

| phasiRNA | phased siRNA |

| tasiRNA | trans-acting siRNAs |

| easiRNA | epigenetically activated siRNAs |

| scaRNAs | small cajal body associated RNAs |

| PmiREN | Plant miRNA Encyclopedia |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RdDM | RNA-directed DNA methylation |

| shRNAs | short hairpin RNAs |

| PLncDB | Plant Long noncoding RNA Database |

| GreeNC, v2.0 | Green Non-Coding Database |

| PNRD | plant ncRNA database |

| RDR2 | RNA-directed RNA polymerase 2 |

| FRILAIR | Fruit ripening-related long intergenic RNA |

| ceRNAs | competing endogenous RNAs |

| LAIR | LRK Antisense Intergenic RNA |

| APOLO | AUXIN-REGULATED PROMOTER LOOP |

| TYLCV | tomato yellow leaf curl virus |

| SABC1 | Salicylic Acid Biogenesis Controller 1 |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species; MAPK- mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| FLC | FLOWERING LOCUS C |

| COLDWRAP | Cold of winter-induced noncoding RNA from the promoter |

| COLDAIR | Cold Assisted Intronic noncoding RNA |

| LDMAR | Long-day-specific male-fertility-associated RNA |

| ASCO | Alternate splicing competitor long noncoding RNA |

| IPS1 | INDUCED BY PHOSPHATE STARVATION 1 |

| HID1 | HIDDEN TREASURE 1 |

| ASL | ANTISENSE LONG |

| PILNCR1 | Pi-deficiency-induced long-noncoding RNA1 |

| GARRs | GIBBERELLIN-RESPONSIVE lncRNAs |

| TRABA | Trans acting of BGLU24 by lncRNA |

| ELENA1 | ELF18-INDUCED LONG-NONCODING RNA1 |

| ChIRP | Chromatin Isolation by RNA Purification. |

References

- Bernal-Gallardo, J.J.; de Folter, S. Plant genome information facilitates plant functional genomics. Planta 2024, 259, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, T.P. Plant genome size variation: bloating and purging DNA. Brief Funct Genomics 2014, 13, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pray, L.A. Eukaryotic Genome Complexity. Nature Education 2008, 1, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.I.; Alam, M.; Lightfoot, D.A.; Gurha, P.; Afzal, A.J. Classification and experimental identification of plant long non-coding RNAs. Genomics 2019, 111, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, F.; Jegu, T.; Latrasse, D.; Romero-Barrios, N.; Christ, A.; Benhamed, M.; Crespi, M. Noncoding Transcription by Alternative RNA Polymerases Dynamically Regulates an Auxin-Driven Chromatin Loop. Molecular Cell 2014, 55, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, A.; Rinn, J.L.; Schier, A.F. Non-coding RNAs as regulators of embryogenesis. Nat Rev Genet 2011, 12, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, F.; Romero-Barrios, N.; Jégu, T.; Benhamed, M.; Crespi, M. Battles and hijacks: noncoding transcription in plants. Trends in Plant Science 2015, 20, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Mattick, J.S.; Taft, R.J. A meta-analysis of the genomic and transcriptomic composition of complex life. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2061–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Liu, Y.; Xia, R. Long Non-Coding RNAs, the Dark Matter: An Emerging Regulatory Component in Plants. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, A.J.; Yu, C.; Petukhova, N.V.; Kalinina, N.O.; Chen, J.; Taliansky, M.E. Cajal bodies and their role in plant stress and disease responses. RNA Biol 2017, 14, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yan, X.; Gu, C.; Yuan, X. Biogenesis, Trafficking, and Function of Small RNAs in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 825477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajczyk, M.; Jarmolowski, A.; Jozwiak, M.; Pacak, A.; Pietrykowska, H.; Sierocka, I.; Swida-Barteczka, A.; Szewc, L.; Szweykowska-Kulinska, Z. Recent Insights into Plant miRNA Biogenesis: Multiple Layers of miRNA Level Regulation. Plants 2023, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G. Plant microRNAs: an insight into their gene structures and evolution. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2010, 21, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, K.; Liu, P.; Wu, C.A.; Yang, G.D.; Xu, R.; Guo, Q.H.; Huang, J.G.; Zheng, C.C. Stress-induced alternative splicing provides a mechanism for the regulation of microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Cell 2012, 48, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Bing, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J.; Sun, X. PlantCircRNA: a comprehensive database for plant circular RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D1595–D1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.S.; Nogueira, F.T.S. Plant Small RNA World Growing Bigger: tRNA-Derived Fragments, Longstanding Players in Regulatory Processes. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 638911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

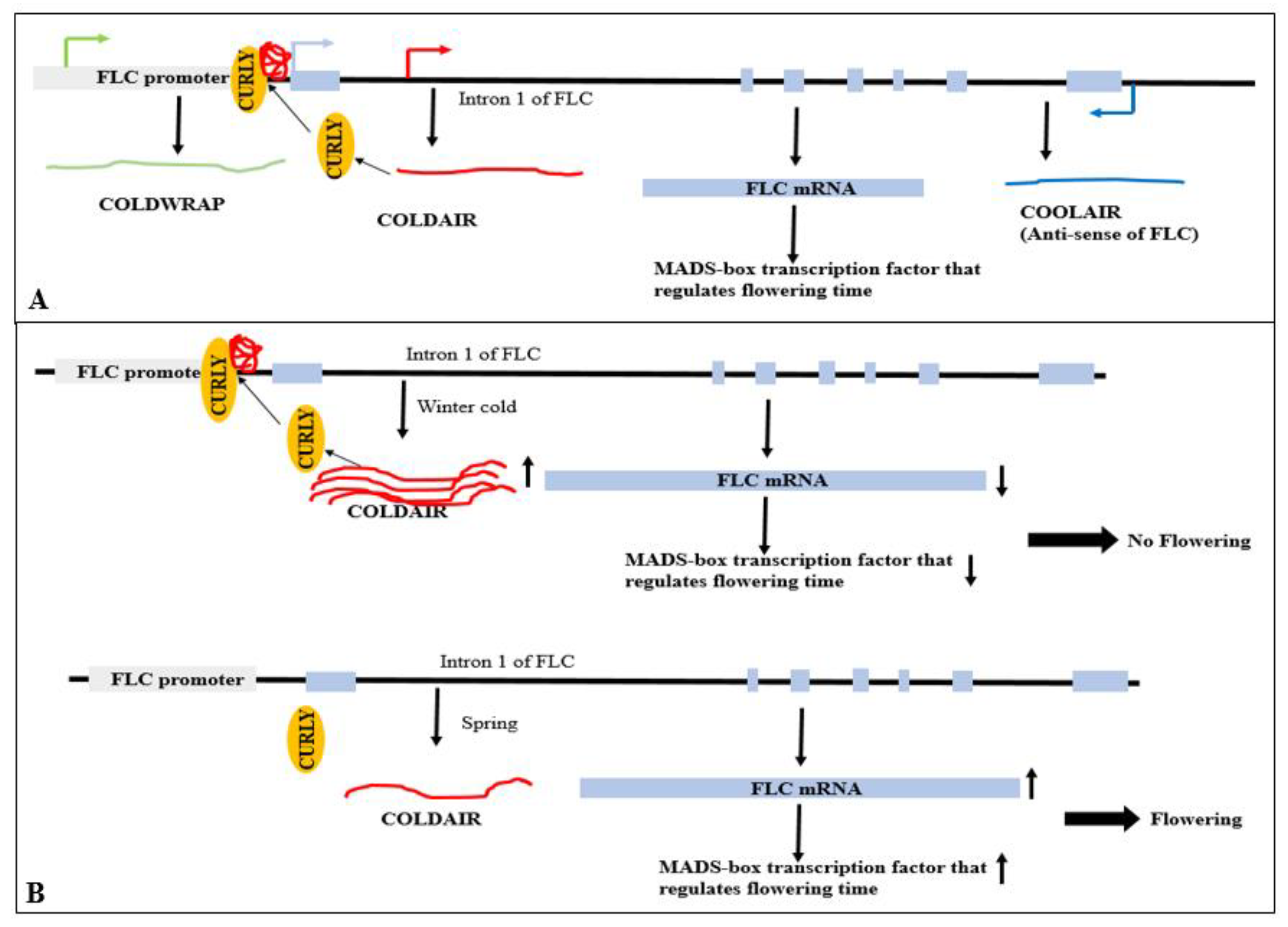

- Kim, D.H.; Sung, S. Vernalization-Triggered Intragenic Chromatin Loop Formation by Long Noncoding RNAs. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2017, 40, 302–312.e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedak, H.; Palusinska, M.; Krzyczmonik, K.; Brzezniak, L.; Yatusevich, R.; Pietras, Z.; Kaczanowski, S.; Swiezewski, S. Control of seed dormancy in <i>Arabidopsis</i> by a <i>cis</i>-acting noncoding antisense transcript. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, E7846–E7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chung, P.J.; Liu, J.; Jang, I.C.; Kean, M.J.; Xu, J.; Chua, N.H. Genome-wide identification of long noncoding natural antisense transcripts and their responses to light in Arabidopsis. Genome Res 2014, 24, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.J.; Nam, A.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwak, J.S.; Song, J.T.; Seo, H.S. Intronic long noncoding RNA, RICE FLOWERING ASSOCIATED (RIFLA), regulates OsMADS56-mediated flowering in rice. Plant Sci 2022, 320, 111278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lu, Q.; Ouyang, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhang, P.; Yao, J.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Q. A long noncoding RNA regulates photoperiod-sensitive male sterility, an essential component of hybrid rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 2654–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, M. Functions of long intergenic non-coding (linc) RNAs in plants. J Plant Res 2017, 130, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Notani, D.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Enhancers as non-coding RNA transcription units: recent insights and future perspectives. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.V.; Chekanova, J.A. Long Noncoding RNAs in Plants. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017, 1008, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, M.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J. Plant non-coding RNAs: The new frontier for the regulation of plant development and adaptation to stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 208, 108435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, W.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y. Unlocking the small RNAs: local and systemic modulators for advancing agronomic enhancement. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir Ul Qamar, M.; Zhu, X.; Khan, M.S.; Xing, F.; Chen, L.L. Pan-genome: A promising resource for noncoding RNA discovery in plants. Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Mathan, J.; Dubey, A.K.; Singh, A. The Emerging Role of Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in Plant Growth, Development, and Stress Response Signaling. Non-Coding RNA 2024, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicki, A.T.; Blevins, T.; Swiezewski, S. Long Noncoding RNAs in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2021, 72, 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Vásquez, J.; Delseny, M. Ribosome Biogenesis in Plants: From Functional 45S Ribosomal DNA Organization to Ribosome Assembly Factors. The Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1945–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.M.; El Allali, A. PltRNAdb: Plant transfer RNA database. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0268904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, S.; Marshallsay, C.; Leader, D.; Brown, J.W.; Filipowicz, W. Small nuclear RNA genes transcribed by either RNA polymerase II or RNA polymerase III in monocot plants share three promoter elements and use a strategy to regulate gene expression different from that used by their dicot plant counterparts. Mol Cell Biol 1994, 14, 5910–5919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, D.; Shanmugam, T.; Garbelyanski, A.; Simm, S.; Schleiff, E. The Existence and Localization of Nuclear snoRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana Revisited. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D. Origination and Function of Plant Pseudogenes. Plant Signal Behav 2019, 14, 1625698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D155–d162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, T.; Ling, Y.; Su, Z. PMRD: plant microRNA database. Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, D806–D813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Kuang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, Y.; He, H.; Wan, M.; Tao, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, J.; Li, L.; et al. PmiREN2.0: from data annotation to functional exploration of plant microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D1475–D1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Liang, S.; Luan, W.; Ma, X. TarDB: an online database for plant miRNA targets and miRNA-triggered phased siRNAs. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinnet, O. Revisiting small RNA movement in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022, 23, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreti, E.; Perata, P. Mobile plant microRNAs allow communication within and between organisms. New Phytol 2022, 235, 2176–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Sainz, E.; Lorente-Cebrián, S.; Aranaz, P.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Martínez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Potential Mechanisms Linking Food-Derived MicroRNAs, Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Barrier Functions in the Context of Nutrition and Human Health. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 586564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Sainz, E.; Milagro, F.I.; Aranaz, P.; Riezu-Boj, J.I.; Lorente-Cebrián, S. MicroRNAs from edible plants reach the human gastrointestinal tract and may act as potential regulators of gene expression. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 2024, 80, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, M.; Tariq, L.; Li, W.; Wu, L. MicroRNA gatekeepers: Orchestrating rhizospheric dynamics. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2025, 67, 845–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T. The regulatory roles of plant miRNAs in biotic stress responses. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2025, 755, 151568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, T.; Selvakumar, D.; Nathan, B.; Shanmugam, V.; Duraisamy, K.; Mannu, J. Deciphering the impact of microRNAs in plant biology: a review of computational insights and experimental validation. Mol Biol Rep 2025, 52, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, L.; Hong, X.; Shi, H.; Li, X. Revealing the novel complexity of plant long non-coding RNA by strand-specific and whole transcriptome sequencing for evolutionarily representative plant species. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.J.; Ma, X.K.; Xing, Y.H.; Zheng, C.C.; Xu, Y.F.; Shan, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Carmichael, G.G.; et al. Distinct Processing of lncRNAs Contributes to Non-conserved Functions in Stem Cells. Cell 2020, 181, 621–636.e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezroni, H.; Koppstein, D.; Schwartz, M.G.; Avrutin, A.; Bartel, D.P.; Ulitsky, I. Principles of long noncoding RNA evolution derived from direct comparison of transcriptomes in 17 species. Cell Rep 2015, 11, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, K.; Yu, R.; Zhou, B.; Huang, P.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J. From “Dark Matter” to “Star”: Insight Into the Regulation Mechanisms of Plant Functional Long Non-Coding RNAs. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yue, C.; Deng, Y.; Tang, Y.Z. Full-length transcriptome analysis of a bloom-forming dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminata (Dinophyceae). Scientific Data 2025, 12, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jung, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Deng, S.; Bernad, L.; Arenas-Huertero, C.; Chua, N.-H. Genome-Wide Analysis Uncovers Regulation of Long Intergenic Noncoding RNAs in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4333–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.B.; Johnston, R.L.; Inostroza-Ponta, M.; Fox, A.H.; Fortini, E.; Moscato, P.; Dinger, M.E.; Mattick, J.S. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNA stability. Genome Res 2012, 22, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, R.S.; Deshotel, M.J.; Johnson, K.; Adler, F.R.; Sieburth, L.E. Arabidopsis mRNA decay landscape arises from specialized RNA decay substrates, decapping-mediated feedback, and redundancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115, E1485–e1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Laurent, G.; Wahlestedt, C.; Kapranov, P. The Landscape of long noncoding RNA classification. Trends Genet 2015, 31, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerner, S.; McGinnis, K.M. Computational Identification and Functional Predictions of Long Noncoding RNA in Zea mays. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e43047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Wang, B.; Yuan, F. Research progress on the roles of lncRNAs in plant development and stress responses. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1138901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Lu, P.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Chua, N.-H.; Cao, P. PLncDB V2.0: a comprehensive encyclopedia of plant long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, D1489–D1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.W.; Wanowska, E. CANTATAdb 3.0: An Updated Repository of Plant Long Non-Coding RNAs. Plant and Cell Physiology 2024, 65, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marsico, M.; Paytuvi Gallart, A.; Sanseverino, W.; Aiese Cigliano, R. GreeNC 2.0: a comprehensive database of plant long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 50, D1442–D1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, L.; Meng, Y.; Chen, L.L.; Chen, M. PlantNATsDB: a comprehensive database of plant natural antisense transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, D1187–D1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, Y.; Xu, W.; Su, Z. PNRD: a plant non-coding RNA database. Nucleic Acids Research 2014, 43, D982–D989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, D.; Li, F.; Ge, J.; Fan, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xing, M.; Guo, W.; Wang, S.; et al. LncPheDB: a genome-wide lncRNAs regulated phenotypes database in plants. aBIOTECH 2022, 3, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sruthi, K.B.; Menon, A.; P, A.; Vasudevan Soniya, E. Pervasive translation of small open reading frames in plant long non-coding RNAs. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 975938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharakan, R.; Sawa, A. Minireview: Novel Micropeptide Discovery by Proteomics and Deep Sequencing Methods. Frontiers in Genetics 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, C.; Johansson, C.; Kondorosi, E.; Kondorosi, A.; Crespi, M. enod40 induces dedifferentiation and division of root cortical cells in legumes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1997, 94, 8901–8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrig, H.; Schmidt, J.; Miklashevichs, E.; Schell, J.; John, M. Soybean ENOD40 encodes two peptides that bind to sucrose synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, N.N.; Moore, S.; Horiguchi, G.; Kubo, M.; Demura, T.; Fukuda, H.; Goodrich, J.; Tsukaya, H. Overexpression of a novel small peptide ROTUNDIFOLIA4 decreases cell proliferation and alters leaf shape in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 2004, 38, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casson, S.A.; Chilley, P.M.; Topping, J.F.; Evans, I.M.; Souter, M.A.; Lindsey, K. The POLARIS gene of Arabidopsis encodes a predicted peptide required for correct root growth and leaf vascular patterning. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1705–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilley, P.M.; Casson, S.A.; Tarkowski, P.; Hawkins, N.; Wang, K.L.C.; Hussey, P.J.; Beale, M.; Ecker, J.R.; Sandberg, G.r.K.; Lindsey, K. The POLARIS Peptide of Arabidopsis Regulates Auxin Transport and Root Growth via Effects on Ethylene Signaling. The Plant Cell 2006, 18, 3058–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauressergues, D.; Couzigou, J.-M.; Clemente, H.S.; Martinez, Y.; Dunand, C.; Bécard, G.; Combier, J.-P. Primary transcripts of microRNAs encode regulatory peptides. Nature 2015, 520, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Badola, P.K.; Bhatia, C.; Sharma, D.; Trivedi, P.K. Primary transcript of miR858 encodes regulatory peptide and controls flavonoid biosynthesis and development in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 2020, 6, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Lin, W.; Ku, Y.-S.; Wong, F.-L.; Li, M.-W.; Lam, H.-M.; Ngai, S.-M.; Chan, T.-F. Analysis of Soybean Long Non-Coding RNAs Reveals a Subset of Small Peptide-Coding Transcripts1 [OPEN]. Plant Physiology 2020, 182, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesenko, I.; Shabalina, S.A.; Mamaeva, A.; Knyazev, A.; Glushkevich, A.; Lyapina, I.; Ziganshin, R.; Kovalchuk, S.; Kharlampieva, D.; Lazarev, V.; et al. A vast pool of lineage-specific microproteins encoded by long non-coding RNAs in plants. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49, 10328–10346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamaeva, A.; Knyazev, A.; Glushkevich, A.; Fesenko, I. Quantitative proteomic dataset of the moss Physcomitrium patens PSEP3 KO and OE mutant lines. Data Brief 2022, 40, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, E.; Li, S.; Orlov, Y.; Ivanisenko, V.; Chen, M. AthRiboNC: an Arabidopsis database for ncRNAs with coding potential revealed from ribosome profiling. Database 2024, 2024, baae123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ouyang, Y.; Ding, W.; Xue, Y.; Zou, Y.; Yan, J.; et al. A Zea genus-specific micropeptide controls kernel dehydration in maize. Cell 2025, 188, 44–59.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, A.K.; Dwivedi, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Lingwan, M.; Dar, M.A.; Bhagavatula, L.; Datta, S. Plant microProteins: Small but powerful modulators of plant development. iScience 2022, 25, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, L.; Van Humbeeck, A.; Niu, H.; Ter Waarbeek, C.; Edwards, A.; Chiurazzi, M.J.; Vittozzi, Y.; Wenkel, S. Exploring the world of small proteins in plant biology and bioengineering. Trends Genet 2025, 41, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Hu, S.; Tang, G.; Chen, J.; Yi, Y.; Xie, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, D.; et al. RNALocate v3.0: Advancing the Repository of RNA Subcellular Localization with Dynamic Analysis and Prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 2025, 53, D284–D292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Jalmi, S.K.; Tiwari, S.; Kerkar, S. Deciphering shared attributes of plant long non-coding RNAs through a comparative computational approach. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 15101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrien, T.; Johnson, R.; Bussotti, G.; Tanzer, A.; Djebali, S.; Tilgner, H.; Guernec, G.; Martin, D.; Merkel, A.; Knowles, D.G.; et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 2012, 22, 1775–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Liao, J.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.P.; Li, Q.F.; Qu, L.H.; Shu, W.S.; Chen, Y.Q. Genome-wide screening and functional analysis identify a large number of long noncoding RNAs involved in the sexual reproduction of rice. Genome Biol 2014, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Eichten, S.R.; Shimizu, R.; Petsch, K.; Yeh, C.T.; Wu, W.; Chettoor, A.M.; Givan, S.A.; Cole, R.A.; Fowler, J.E.; et al. Genome-wide discovery and characterization of maize long non-coding RNAs. Genome Biol 2014, 15, R40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yuan, D.; Tu, L.; Gao, W.; He, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, N.; Lindsey, K.; Zhang, X. Long noncoding RNAs and their proposed functions in fibre development of cotton (Gossypium spp.). New Phytol 2015, 207, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, A.J.; Schmitz, R.J. Gene body DNA methylation in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2017, 36, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.A.; Jacobsen, S.E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Mei, H.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L.; Tao, X.; Feng, S.; Fang, L.; Guan, X. Absence of CG methylation alters the long noncoding transcriptome landscape in multiple species. FEBS Lett 2021, 595, 1734–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ci, D.; Tian, M.; Zhang, D. Stable methylation of a non-coding RNA gene regulates gene expression in response to abiotic stress in Populus simonii. J Exp Bot 2016, 67, 1477–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lyons, D.B.; Kim, M.Y.; Moore, J.D.; Zilberman, D. DNA Methylation and Histone H1 Jointly Repress Transposable Elements and Aberrant Intragenic Transcripts. Molecular Cell 2020, 77, 310–323.e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Sun, D.; Zhou, B.; Li, J. Insights into the Epigenetic Basis of Plant Salt Tolerance. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginno, P.A.; Lott, P.L.; Christensen, H.C.; Korf, I.; Chédin, F. R-loop formation is a distinctive characteristic of unmethylated human CpG island promoters. Mol Cell 2012, 45, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, L.; Fonouni-Farde, C.; Crespi, M.; Ariel, F. Long noncoding RNAs shape transcription in plants. Transcription 2020, 11, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonouni-Farde, C.; Christ, A.; Blein, T.; Legascue, M.F.; Ferrero, L.; Moison, M.; Lucero, L.; Ramírez-Prado, J.S.; Latrasse, D.; Gonzalez, D.; et al. The Arabidopsis APOLO and human UPAT sequence-unrelated long noncoding RNAs can modulate DNA and histone methylation machineries in plants. Genome Biology 2022, 23, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.K. Epigenetic gene regulation in plants and its potential applications in crop improvement. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2025, 26, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmdorfer, G.; Sethuraman, S.; Rowley, M.J.; Krzyszton, M.; Rothi, M.H.; Bouzit, L.; Wierzbicki, A.T. Long non-coding RNA produced by RNA polymerase V determines boundaries of heterochromatin. eLife 2016, 5, e19092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, R.M.; Picard, C.L. RNA-directed DNA Methylation. PLoS Genet 2020, 16, e1009034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, T.; Kang, H. Crosstalk between RNA m(6)A modification and epigenetic factors in plant gene regulation. Plant Commun 2024, 5, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L. Functional interdependence of N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase complex subunits in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 1901–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Cao, S.; Huang, Q.; Xia, L.; Deng, M.; Yang, M.; Jia, G.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Wang, W.; et al. The RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification landscape of human fetal tissues. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, Z.; Duan, H.C.; Fang, X.; Jia, G.; Dean, C. R-loop resolution promotes co-transcriptional chromatin silencing. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Lam, H.M.; Chan, T.F. Nanopore direct RNA sequencing reveals N(6)-methyladenosine and polyadenylation landscapes on long non-coding RNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 2024, 24, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, M.G.; Chen, R.; Zhang, W.H. Identification and characterization of long non-coding RNAs involved in osmotic and salt stress in Medicago truncatula using genome-wide high-throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol 2015, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Rosas, E.; Hernández-Oñate, M.; Fernandez-Valverde, S.L.; Tiznado-Hernández, M.E. Plant long non-coding RNAs: identification and analysis to unveil their physiological functions. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1275399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lai, X.; Yu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Chen, J.; Lang, X.; Feng, H.; Wan, X.; Liu, K. Plant long noncoding RNAs: Recent progress in understanding their roles in growth, development, and stress responses. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2023, 671, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

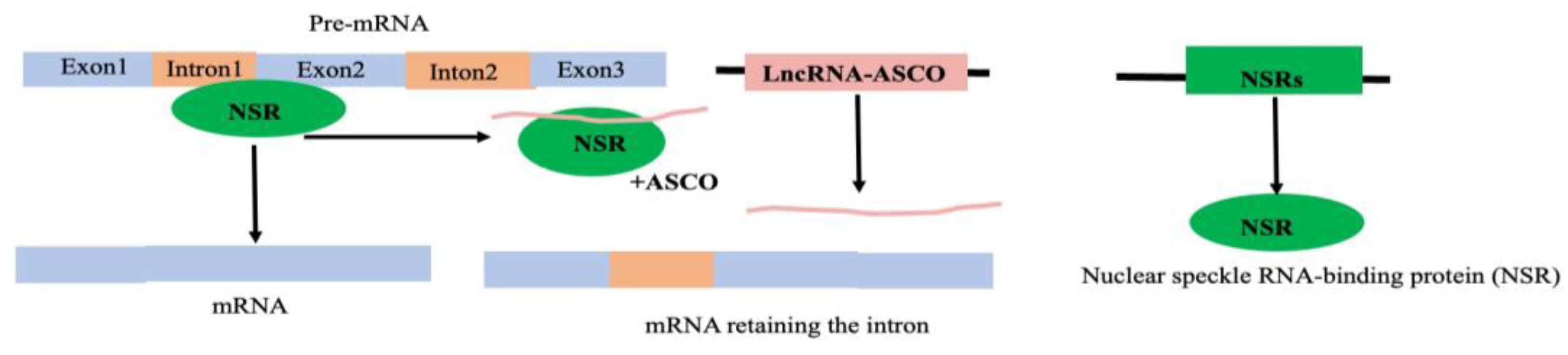

- Bardou, F.; Ariel, F.; Simpson, C.G.; Romero-Barrios, N.; Laporte, P.; Balzergue, S.; Brown, John W.S.; Crespi, M. Long Noncoding RNA Modulates Alternative Splicing Regulators in Arabidopsis. Developmental Cell 2014, 30, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, M. Identification and characterization of ncRNA-associated ceRNA networks in Arabidopsis leaf development. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Kang, B.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.; Xiao, H.; Shen, H.; Yang, W. Transcription of lncRNA ACoS-AS1 is essential to trans-splicing between SlPsy1 and ACoS-AS1 that causes yellow fruit in tomato. RNA Biol 2020, 17, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Qu, Z.; Lei, J.; He, R.; Adelson, D.L.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, D. The long noncoding RNA FRILAIR regulates strawberry fruit ripening by functioning as a noncanonical target mimic. PLoS Genet 2021, 17, e1009461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Liu, X.; Sun, F.; Cao, J.; Huo, N.; Wuda, B.; Xin, M.; Hu, Z.; Du, J.; Xia, R.; et al. Wheat miR9678 Affects Seed Germination by Generating Phased siRNAs and Modulating Abscisic Acid/Gibberellin Signaling. The Plant Cell 2018, 30, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, R.; Bazin, J.; Romero-Barrios, N.; Moison, M.; Lucero, L.; Christ, A.; Benhamed, M.; Blein, T.; Huguet, S.; Charon, C.; et al. The Arabidopsis lncRNA ASCO modulates the transcriptome through interaction with splicing factors. EMBO Rep 2020, 21, e48977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Gao, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, H. Identification and Functional Analysis of Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA) in Response to Seed Aging in Rice. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Pi, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Cui, X.; Liu, H.; Yao, D.; Zhao, R. Update on functional analysis of long non-coding RNAs in common crops. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1389154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Ji, B.; Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Huang, P.; Yu, R.; Zhang, H.; Dou, X.; Chen, Q.; et al. EVLncRNAs 3.0: an updated comprehensive database for manually curated functional long non-coding RNAs validated by low-throughput experiments. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, D98–d106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblihtt, A.R. A long noncoding way to alternative splicing in plant development. Dev Cell 2014, 30, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campalans, A.; Kondorosi, A.; Crespi, M. Enod40, a short open reading frame-containing mRNA, induces cytoplasmic localization of a nuclear RNA binding protein in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, M.D.; Jurkevitch, E.; Poiret, M.; d'Aubenton-Carafa, Y.; Petrovics, G.; Kondorosi, E.; Kondorosi, A. enod40, a gene expressed during nodule organogenesis, codes for a non-translatable RNA involved in plant growth. Embo j 1994, 13, 5099–5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

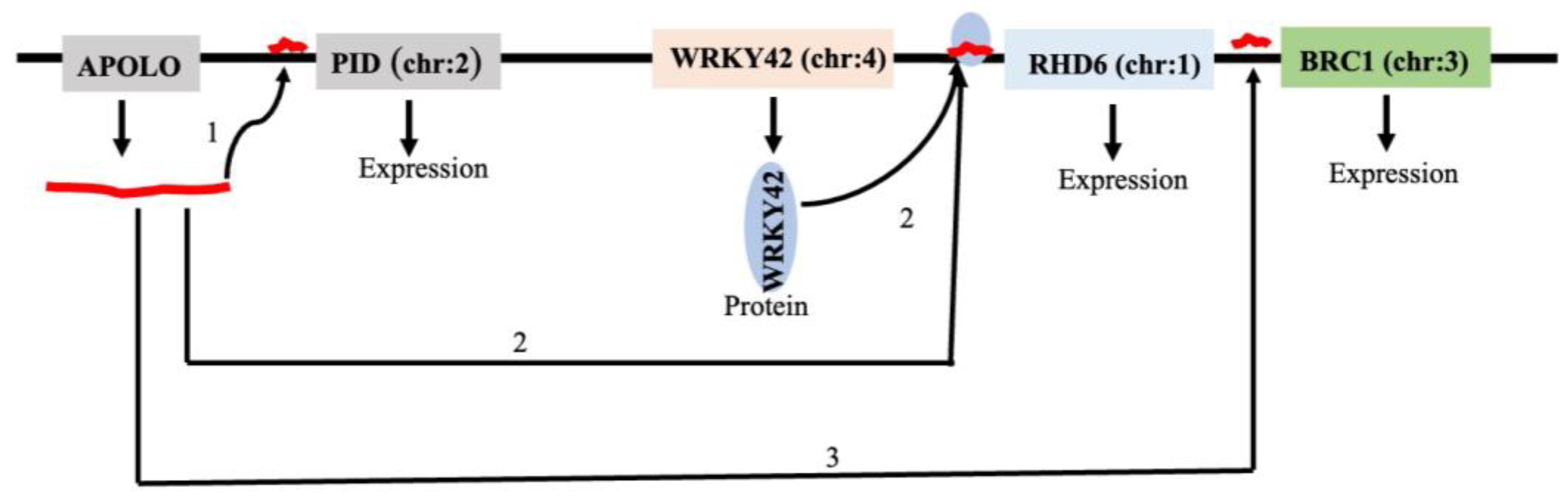

- Ariel, F.; Lucero, L.; Christ, A.; Mammarella, M.F.; Jegu, T.; Veluchamy, A.; Mariappan, K.; Latrasse, D.; Blein, T.; Liu, C.; et al. R-Loop Mediated trans Action of the APOLO Long Noncoding RNA. Molecular Cell 2020, 77, 1055–1065.e1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, S.; Shi, L.; Chen, G.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Guo, G. Interaction between long noncoding RNA and microRNA in lung inflammatory diseases. Immun Inflamm Dis 2024, 12, e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pian, C.; Zhang, G.; Tu, T.; Ma, X.; Li, F. LncCeRBase: a database of experimentally validated human competing endogenous long non-coding RNAs. Database (Oxford) 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhou, R.; Jiang, F.; Li, P.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Wei, H.; Wu, Z. Construction of ceRNA Networks at Different Stages of Somatic Embryogenesis in Garlic. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

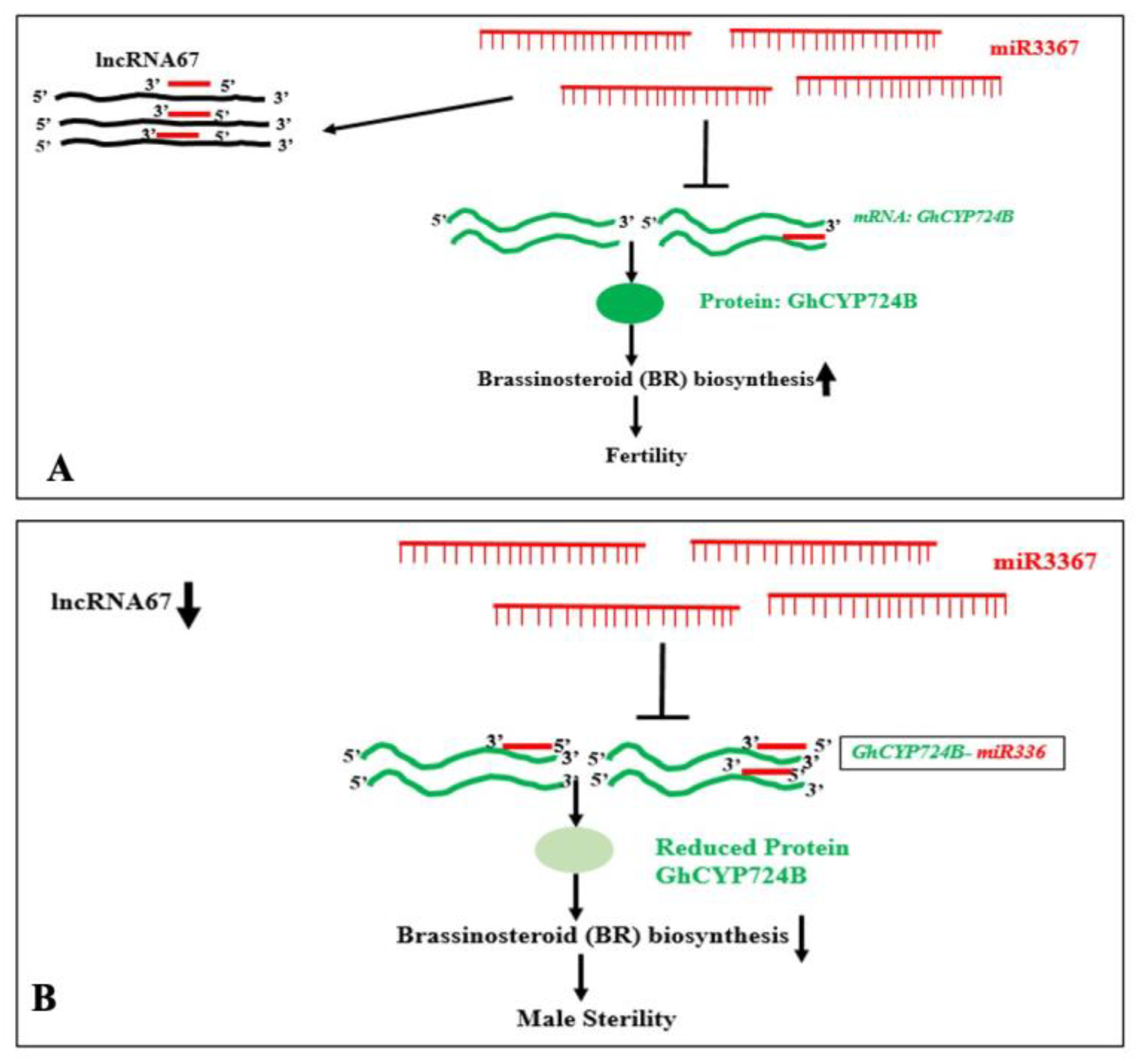

- Guo, A.; Nie, H.; Li, H.; Li, B.; Cheng, C.; Jiang, K.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, N.; Hua, J. The miR3367-lncRNA67-GhCYP724B module regulates male sterility by modulating brassinosteroid biosynthesis and interacting with Aorf27 in Gossypium hirsutum. J Integr Plant Biol 2025, 67, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Q.; Meng, J.; Su, C.; Luan, Y. Mining plant endogenous target mimics from miRNA–lncRNA interactions based on dual-path parallel ensemble pruning method. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2022, 23, bbab440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, D.; Zhang, T.; Duan, A.; Zhang, J.; He, C. Transcriptomic and functional analyses unveil the role of long non-coding RNAs in anthocyanin biosynthesis during sea buckthorn fruit ripening. DNA Res 2018, 25, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakülah, G.; Yücebilgili Kurtoğlu, K.; Unver, T. PeTMbase: A Database of Plant Endogenous Target Mimics (eTMs). PLoS One 2016, 11, e0167698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmena, L.; Poliseno, L.; Tay, Y.; Kats, L.; Pandolfi, P.P. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 2011, 146, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.; Rinn, J.; Pandolfi, P.P. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 2014, 505, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Zorrilla, J.M.; Valli, A.; Todesco, M.; Mateos, I.; Puga, M.I.; Rubio-Somoza, I.; Leyva, A.; Weigel, D.; García, J.A.; Paz-Ares, J. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nature Genetics 2007, 39, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unver, T.; Tombuloglu, H. Barley long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA) responsive to excess boron. Genomics 2020, 112, 1947–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wang, H.; Chi, R.; Qiao, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. The eTM-miR858-MYB62-like module regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis under low-nitrogen conditions in Malus spectabilis. New Phytol 2023, 238, 2524–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

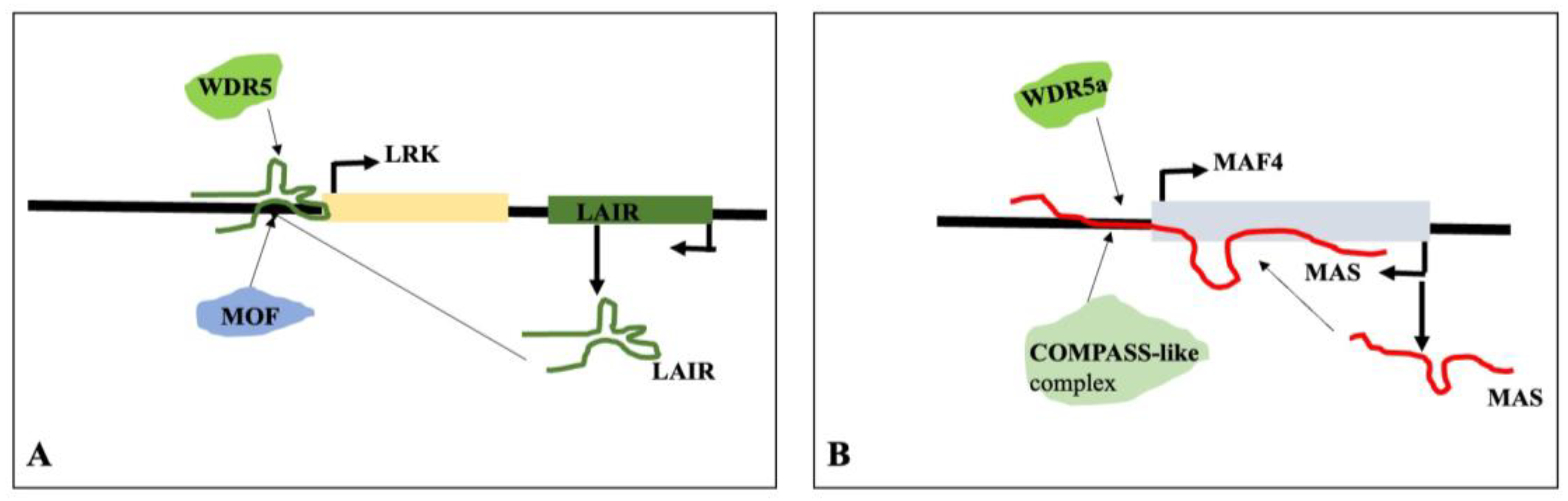

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Sun, F.; Hu, J.; Zha, X.; Su, W.; Yang, J. Overexpressing lncRNA LAIR increases grain yield and regulates neighbouring gene cluster expression in rice. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Lian, B.; Gu, H.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y. Global identification of Arabidopsis lncRNAs reveals the regulation of MAF4 by a natural antisense RNA. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moison, M.; Pacheco, J.M.; Lucero, L.; Fonouni-Farde, C.; Rodríguez-Melo, J.; Mansilla, N.; Christ, A.; Bazin, J.; Benhamed, M.; Ibañez, F.; et al. The lncRNA APOLO interacts with the transcription factor WRKY42 to trigger root hair cell expansion in response to cold. Mol Plant 2021, 14, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, J.M.; Mansilla, N.; Moison, M.; Lucero, L.; Gabarain, V.B.; Ariel, F.; Estevez, J.M. The lncRNA APOLO and the transcription factor WRKY42 target common cell wall EXTENSIN encoding genes to trigger root hair cell elongation. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2021, 16, 1920191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammarella, M.F.; Lucero, L.; Hussain, N.; Muñoz-Lopez, A.; Huang, Y.; Ferrero, L.; Fernandez-Milmanda, G.L.; Manavella, P.; Benhamed, M.; Crespi, M.; et al. Long noncoding RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of auxin-related genes controls shade avoidance syndrome in Arabidopsis. Embo j 2023, 42, e113941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.B.; Sung, S. Vernalization-Mediated Epigenetic Silencing by a Long Intronic Noncoding RNA. Science 2011, 331, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiezewski, S.; Liu, F.; Magusin, A.; Dean, C. Cold-induced silencing by long antisense transcripts of an Arabidopsis Polycomb target. Nature 2009, 462, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, N.M.; Schroeder, S.J. SVALKA: A Long Noncoding Cis-Natural Antisense RNA That Plays a Role in the Regulation of the Cold Response of Arabidopsis thaliana. Noncoding RNA 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

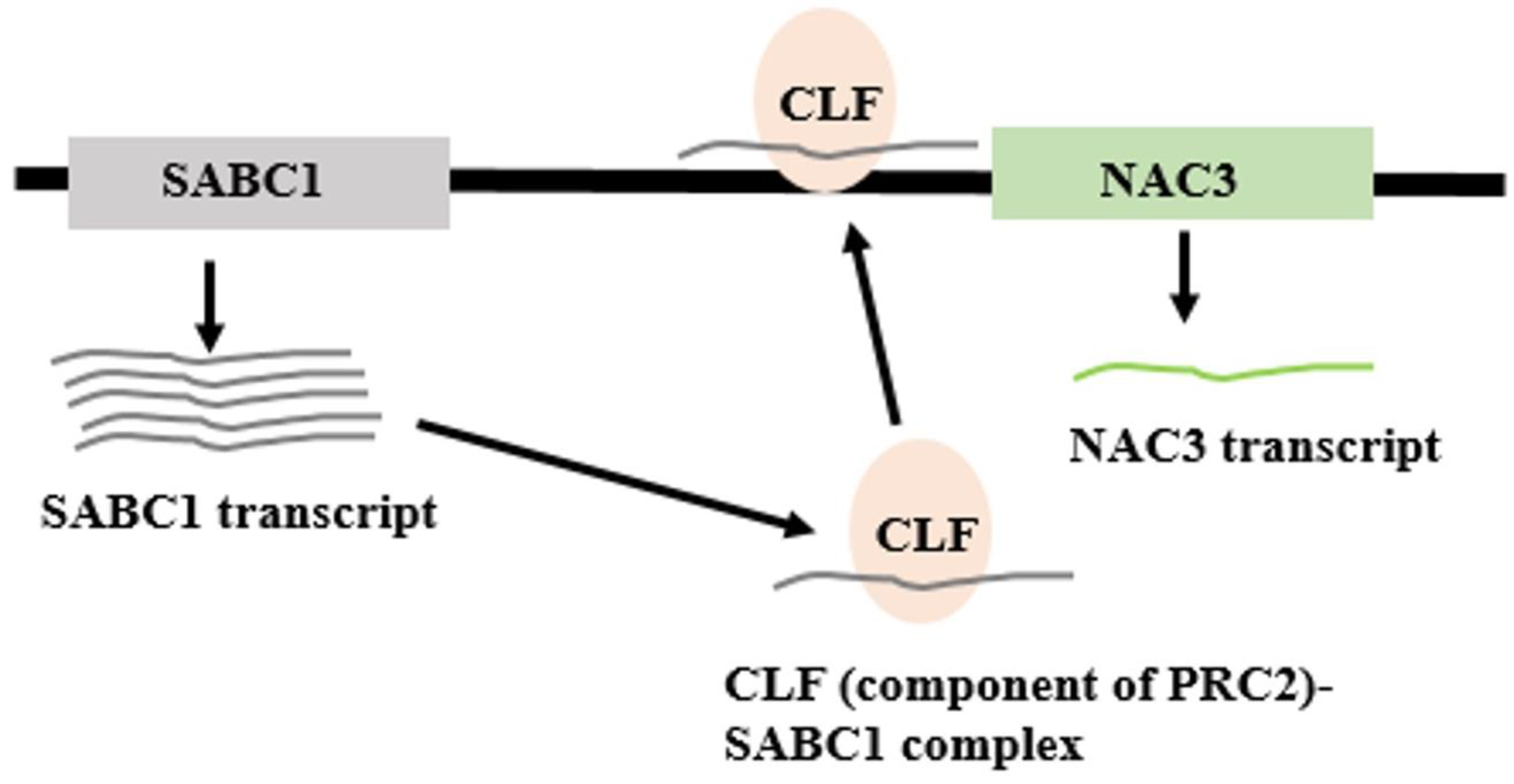

- Liu, N.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Cao, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Mi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ding, C.; et al. A lncRNA fine-tunes salicylic acid biosynthesis to balance plant immunity and growth. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1124–1138.e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, J.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, K.; Wang, W.; Feng, Y.; Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNAs affecting floral bud dormancy in pears in response to cold stress. Tree Physiol 2021, 41, 771–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, Z.; Dong, S.; Li, Z.; Zou, L.; Zhao, P.; Guo, X.; Bao, Y.; Wang, W.; Peng, M. Global identification of full-length cassava lncRNAs unveils the role of cold-responsive intergenic lncRNA 1 in cold stress response. Plant Cell Environ 2022, 45, 412–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Shi, S.; Jiang, N.; Khanzada, H.; Wassan, G.M.; Zhu, C.; Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of long non-coding RNAs affecting roots development at an early stage in the rice response to cadmium stress. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Meng, L.; He, B.; Qi, W.; Jia, L.; Xu, N.; Hu, F.; Lv, Y.; Song, W. Comprehensive Transcriptome Analysis Uncovers Hub Long Non-coding RNAs Regulating Potassium Use Efficiency in Nicotiana tabacum. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 777308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, C.; Yuan, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Lin, H.; Hu, L.; Zhang, T.; Qi, Y.; Gerstein, M.B.; Guo, Y.; et al. Characterization of stress-responsive lncRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana by integrating expression, epigenetic and structural features. Plant J 2014, 80, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ding, Z.; Tan, D.; Han, B.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide discovery and functional prediction of salt-responsive lncRNAs in duckweed. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wei, Q.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Peng, X.; Han, G.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, Y. Identification and characterization of heat-responsive lncRNAs in maize inbred line CM1. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Bharadwaj, C.; Sahu, S.; Shiv, A.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Reddy, S.P.P.; Soren, K.R.; Patil, B.S.; Pal, M.; Soni, A.; et al. Genome-wide identification and functional prediction of salt- stress related long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2021, 27, 2605–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Hu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, F.; Gaut, B.S. Maize transposable elements contribute to long non-coding RNAs that are regulatory hubs for abiotic stress response. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhao, H.; Cui, P.; Albesher, N.; Xiong, L. A Nucleus-Localized Long Non-Coding RNA Enhances Drought and Salt Stress Tolerance. Plant Physiol 2017, 175, 1321–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.-W.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q.; Wu, F. Genome-wide characterization of drought stress responsive long non-coding RNAs in Tibetan wild barley. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2019, 164, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Dai, L.; Ai, J.; Wang, Y.; Ren, F. Identification and functional prediction of cold-related long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) in grapevine. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, M.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y.; Song, N.; Hu, Z.; Qin, D.; Xie, C.; Peng, H.; Ni, Z.; Sun, Q. Identification and characterization of wheat long non-protein coding RNAs responsive to powdery mildew infection and heat stress by using microarray analysis and SBS sequencing. BMC Plant Biol 2011, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Su, X.; Ge, P.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, Y.; Shu, H.; Gao, C.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, G.; et al. Early Response of Radish to Heat Stress by Strand-Specific Transcriptome and miRNA Analysis. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, T.; Yu, X.; Tian, R.; Zhang, W.H. Identification of tissue-specific and cold-responsive lncRNAs in Medicago truncatula by high-throughput RNA sequencing. BMC Plant Biol 2020, 20, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.H.; Stephen, S.; Taylor, J.; Helliwell, C.A.; Wang, M.B. Long noncoding RNAs responsive to Fusarium oxysporum infection in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 2014, 201, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, T.; Ma, N.; Yang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, B. Corrigendum: Genome-wide analysis of tomato long non-coding RNAs and identification as endogenous target mimic for microRNA in response to TYLCV infection. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z. Regulation of Long Noncoding RNAs Responsive to Phytoplasma Infection in Paulownia tomentosa. Int J Genomics 2018, 2018, 3174352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jiang, N.; Hou, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, J.; Luan, Y. Genome-Wide Identification of lncRNAs and Analysis of ceRNA Networks During Tomato Resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Phytopathology 2020, 110, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Luan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Bao, H.; Meng, J. Comparative transcriptome analysis between resistant and susceptible tomato allows the identification of lncRNA16397 conferring resistance to Phytophthora infestans by co-expressing glutaredoxin. The Plant Journal 2017, 89, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Hong, Y.H.; Liu, Y.R.; Cui, J.; Luan, Y.S. Function identification of miR394 in tomato resistance to Phytophthora infestans. Plant Cell Rep 2021, 40, 1831–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Hao, K.; Du, Z.; Zhang, S.; Guo, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; An, M.; Xia, Z.; Wu, Y. Whole-transcriptome characterization and functional analysis of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks responsive to sugarcane mosaic virus in maize resistant and susceptible inbred lines. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 257, 128685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Cao, J.; Gao, J.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Gan, L.; Zhu, C. Genome-wide identification and association analysis for virus-responsive lncRNAs in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Growth Regulation 2022, 98, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y.F.; Feng, Y.Z.; He, H.; Lian, J.P.; Yang, Y.W.; Lei, M.Q.; Zhang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.Q. Transcriptional landscape of pathogen-responsive lncRNAs in rice unveils the role of ALEX1 in jasmonate pathway and disease resistance. Plant Biotechnol J 2020, 18, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Zhao, G.; Lu, X.; Dai, S.; Cui, X.; Yuan, M.; Liu, Z. Integrated analysis of the lncRNA/circRNA-miRNA-mRNA expression profiles reveals novel insights into potential mechanisms in response to root-knot nematodes in peanut. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoei, M.A.; Karimi, M.; Karamian, R.; Amini, S.; Soorni, A. Identification of the Complex Interplay Between Nematode-Related lncRNAs and Their Target Genes in Glycine max L. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 779597. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 779597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Zadegan, S.B.; Sultana, M.S.; Coffey, N.; Rice, J.H.; Hewezi, T. Regulation and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs During Meloidogyne incognita Parasitism of Tomato. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2025, 38, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Saeed, S.; Batchelor, W.D.; Alariqi, M.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, F.; Zou, J.; Xu, Z.; Si, H.; et al. Identification and Functional Analysis of lncRNA by CRISPR/Cas9 During the Cotton Response to Sap-Sucking Insect Infestation. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 784511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Cao, W.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhou, B.; Wang, J. PotatoBSLnc: a curated repository of potato long noncoding RNAs in response to biotic stress. Database 2025, 2025, baaf015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejat, N.; Mantri, N. Emerging roles of long non-coding RNAs in plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2018, 38, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jiang, N.; Meng, J.; Yang, G.; Liu, W.; Zhou, X.; Ma, N.; Hou, X.; Luan, Y. LncRNA33732-respiratory burst oxidase module associated with WRKY1 in tomato- Phytophthora infestans interactions. Plant J 2019, 97, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. Roles of long non-coding RNAs in plant immunity. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19, e1011340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.B.; Lee, Y.S.; Sung, S. Epigenetic regulation by long noncoding RNAs in plants. Chromosome Res 2013, 21, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Species | Common name | recursor miRNA | Mature miRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Arabidopsis | 326 | 430 |

| Oryza sativa | Rice | 604 | 757 |

| Triticum aestivum | Wheat | 122 | 125 |

| Hordeum vulgare | Barley | 69 | 72 |

| Zea mays | Maiz | 174 | 325 |

| Lotus japonicu | Wild legume | 299 | 365 |

| Solanum tuberosum | Potato | 224 | 343 |

| Glycine max | Soybean | 684 | 756 |

| Brassica rapa | Mustard | 96 | 157 |

| Gossypium_hirsutum | Cotton | - | 240* |

| Homo sapiens | Human | 1917 | 2693 |

| Mus musculus | Mouse | 1234 | 2013 |

| Species | Common name | Genome size | LncRNA | Protein-coding gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Arabidopsis | 119 Mb | 13599 | 27,562 |

| Oryza sativa Japonica Group | Rice | 385.7 Mb | 11565 | 29,427 |

| Triticum aestivum | Wheat | 14.6 Gb | 43659 | 1,03,787 |

| Hordeum vulgare | Barley | 4.2 Gb | 25884 | 31,448 |

| Zea mays | Maiz | 2.2 Gb | 32397 | 34,313 |

| Lotus japonicu | Wild legume | 553.7 Mb | 2936 | 32,752 |

| Solanum tuberosum | Potato | 705.8 Mb | 16485 | 28,411 |

| Glycine max | Soybean | 978.4 Mb | 12577 | 47,068 |

| Brassica rapa | Mustard | 352.8 Mb | 17519 | 41,403 |

| Gossypium_hirsutum | Cotton | 2.3 Gb | 53721@ | 67,584 |

| Dinoflagellate Scrippsiella acuminate*** | Cosmopolitan microalga | ~ 51.44 Gb | 78,393 | 116,417[50] |

| Homo sapience | Human | 3.1 Gb | 35934* | 20,078 |

| Mus musculus | Mouse | 2.7 Gb | 36172** | 22,198 |

| Plants | Nucleus | Cytoplasm | Ribosome* | Exosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 66.6% | 31.8% | 0.1% | 1.5% |

| Oryza sativa | 53.7% | 38.2% | 1.1% | 7.0% |

| Zea mays | 45.9% | 44.7% | 1.3% | 8.1% |

| Stage | Pathogen/plant | LncRNAs | Target | Activates/ Inhibits targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROS production | Oomycete/tomato | LncRNA33732 | RBOH | Activates |

| Oomycete/tomato Virus/tobacco |

LncRNA16397 LncRNA LMT1 |

SlGRX AOX-1a |

Inhibits Inhibits |

|

| Calcium Influx | Abiotic stress/ Mulberry | MuLnc1 | MuCML27 | Inhibits |

| MAPKs cascades | Oomycete/Arabidopsis | nalncFL7 | nalncFL7-FL7-HAI1-MAPK3/6 | Activates |

| NLR | Oomycete or water mold /Tomato Oomycete or water mold /Tomato Oomycete or water mold /Tomato |

LncRNA23468 Sl-lncRNA15492 LncRNA08489 |

miR482b miR482a miR482e-3p |

Activates Activates Activates |

| Defense-related genes | Bacteria/Arabidopsis Oomycete/Tomato Flagellin (bacterial PAMP)/Arabidopsis |

ELENA1 LncRNA39026 ASCO |

MED19a SlPR1, SlPR2, SlPR3, SlPR5 NSRs |

Activates Activates Activates |

| Modulate defense-related genes | ||||

| Genes related to Salicyclic Acid (SA) synthesis | Virus/Tobacco Virus/Arabidopsis |

LMT1 SABC1 |

AOX-1a NAC3 |

Inhibits Activates |

| Genes related to Jasmonic Acid (JA)synthesis | Bacteia /Oryza sativa Fungus/Cotton Insect/Tobacco Fungus/Cotton |

ALEX1 LOX3 JAL1 and JAL3 GhlncNAT-ANX2, GhlncNAT-RLP7 |

AZ8, MYC2, PR1a, etc GhLOX3 WIPK, WRKY3, WRKY6, etc. ANX2, RLP7 |

Activates Activates Activates Inhibits |

| Genes related to JA and ethylene synthesis | Oomycete/tomato | LncRNA39896 | SlHDZ34 SlHDZ45 | Inhibits |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).