1. Introduction

Comets are “

Space Busses” known to harbor organic molecules relevant to prebiotic chemistry, including hydrogen cyanide (HCN) [

1], ammonia (NH₃) [

2], formaldehyde (H₂CO) [

3], methanol (CH₃OH) [

4], formic acid (HCOOH) [

5], and phosphate-bearing minerals [

6], as confirmed by direct and indirect observational data from space missions such as Rosetta, e.g., ROSINA (Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis), ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array), and COSAC (gas analyzer Cometary Sampling and Composition) to comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko [

7]. The detection of these molecular precursors, also in dust [

8], is of crucial importance: they represent essential building blocks for the synthesis of complex organic molecules such as amino acids, sugars, nucleobases, nucleosides, and nucleotides, i.e., main components required for the emergence of life [

9]. Cometary nuclei likely are over most of their history at temperatures of about 50 K while their surfaces and the outer layers, where most chemistry is active, are subject to extreme thermal cycling ranging from cryogenic temperatures of ~ 50 K in the Oort cloud, to over 300 K at ~ 1 AU, and even above 1000 K for sungrazing comets [

10]. In addition, cometary surfaces are exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, cosmic ray, and sporadic heating during perihelion passages, creating highly energetic but non-equilibrium conditions [

11]. These distinctive conditions enable chemical reactions that might be energetically unfavorable or kinetically inaccessible under standard terrestrial conditions, making comets ideal natural laboratories for prebiotic chemistry [

12]. Within nuclei superficial regions, chemical reactions that are kinetically inaccessible under Earth-like conditions can proceed via photochemical activation and radical-mediated pathways [

13].

Several synthetic pathways for nucleobases and sugars formation under such conditions have been proposed. These include the Strecker synthesis, radical polymerization of formamide (HCONH

2), and HCN-based oligomerization [

14,

15]. Compounds such as glycolaldehyde (HOCH₂-CHO) and formamide have been detected in cometary comae [

16] supporting the astrochemical plausibility of these pathways. The presence of minerals in cometary nuclei [

17], including silicates [

18], metal oxides, sulfides [

19], and phosphates, provides crucial catalytic sites that can strongly influence chemical reactivity and selectivity. The role of comets in delivering prebiotic molecules to Earth, a key aspect of the panspermia hypothesis, has gained increasing attention [

20]. Laboratory experiments simulating cometary impact conditions demonstrate the survival of complex organics encapsulated within icy or mineral matrices during atmospheric entry [

21]. A systematic understanding of the thermodynamic feasibility of these synthetic reactions under cometary conditions is still to be investigated.

In this paper, aiming to assess whether reactions involved in prebiotic synthesis of nucleobases, sugars, nucleosides and nucleotides are energetically viable on cometary surfaces, I report on a thermodynamic analysis performed assuming solid-phase chemistry and neglecting aqueous intermediates unless explicitly justified.

2. Thermodynamic Calculations

To evaluate the thermodynamic feasibility for seven key prebiotic reactions, involved in prebiotic synthesis of nucleobases, sugars, nucleosides, and nucleotides, to occur on cometary nuclei, I estimated the Gibbs free energy variation, ΔG, at temperature, T, spanning from 50 K to 1000 K, mimicking different cometary conditions. Standard enthalpies of formation (ΔH°

f) and molar entropies (S°) for the molecular species involved were collected from experimental databases, e.g., NIST, Cheméo, and from [

22] for adenosine and adenosine 5’-monophosphate. Where unavailable, values were estimated by analogy with structurally related molecules. All molecular states were considered in their condensed form, i.e., solid or liquid, except for carbon monoxide which was treated as gas under standard conditions.

The following thermodynamic equation was applied:

where ΔH and ΔS for each reaction were calculated from the sum of the products minus the sum of the reactants. In cases where only gas-phase values were available, e.g., cyanamide, aminoacetonitrile, the solid-state enthalpy of formation was calculated by subtracting the enthalpy of sublimation (ΔH_sub) from the gas-phase value:

Standard molar entropies were assumed to vary minimally. For AMP aqueous-phase values [

22] were used as an approximation for solid-state properties. All calculations and assumptions are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3. Results

3.1. Formation of Nitrogenous Bases via Strecker Synthesis

In the Strecker Synthesis, hydrogen cyanide (HCN), ammonia (NH₃), and formaldehyde (H₂CO) react to form aminoacetonitrile (NH₂CH₂CN), a relatively stable intermediate under cometary cryogenic conditions:

Under moderate UV irradiation, aminoacetonitrile can undergo polymerization and subsequent cyclization to adenine (C₅H₅N₅), with water as a by-product:

I computed the ΔG for reaction (4) at temperatures from 50 to 1000 K (

Table 2). Our results confirm that this reaction is strongly exergonic across all surface-relevant temperatures, with ΔG decreasing from -402.5 kcal mol

-1 at 50 K to -450.0 kcal mol

-1 at 1000 K. At 200 K the calculated ΔG is -410.0 kcal mol

-1, driven almost entirely by the enthalpic gain associated with aromatic ring formation in adenine. The entropy term (TΔS) is minimal at low temperatures, reinforcing the enthalpy-dominant profile of the reaction. This makes the Strecker-based synthesis of adenine the most thermodynamically favorable pathway among all routes analyzed in this study. Even in deep-space cometary reservoirs (~ 50 K), the reaction remains spontaneous and exergonic, indicating that neither perihelion heating nor catalytic enhancement is required for thermodynamic feasibility. Kinetic constraints remain critical. UV photons are essential not only for initiating polymerization, but also for overcoming activation energy barriers associated with cyclization. As discussed by [

23], radical intermediates mediate the formation of the heterocyclic adenine structure. Overexposure to radiation may lead to photolysis or the formation of non-volatile polymeric byproducts. An important limitation involves the potential transformation of aminoacetonitrile under transient aqueous conditions. Aminoacetonitrile can hydrolyze to glycine (NH₂CH₂COOH), a compound that has been detected in cometary samples [

24]. This alternative pathway competes with adenine formation and may reduce overall yields. Extremely low cometary temperatures slow down unwanted side reactions, prolonging aminoacetonitrile stability and enhancing polymerization [

25]. Mineral surfaces may play a stabilizing role by adsorbing intermediates, limiting hydrolysis, and guiding stereoselective polymerization [

26].

3.2. Formation of Nitrogenous Bases via Radical Synthesis from Formamide

Formamide (HCONH₂), spectroscopically detected in cometary nuclei, can be an alternative precursor for nitrogenous base [

27] formation through radical-driven reactions induced by UV radiation and cosmic rays:

At T = 200 K, ΔG is -32.0 kcal mol

-1, indicating that the reaction is moderately exergonic. The exothermicity derives not only from the formation of aromatic rings in adenine [

28], but also from the release of volatile low-entropy molecules such as CO and H₂O. As temperature increases, the entropy contribution becomes more favorable, and ΔG becomes increasingly negative, reaching -60.0 kcal mol

-1 for T=1000 K (

Table 2). These results suggest that this pathway is thermodynamically viable over the entire surface temperature range of cometary bodies, although less favorable than the Strecker pathway (reaction 4). Under cometary UV exposure, formamide is prone to fragmentation into simpler species such as NH₃, CO₂, or HCN, which reduces the efficiency of nucleobase formation [

29]. Free radicals generated by UV radiation or cosmic rays can initiate uncontrolled polymerization, producing a wide spectrum of oligomers instead of specific nucleobase products. The stability of radical intermediates is sensitive to thermal fluctuations. Without stabilizing mineral surfaces or radiation-shielded microenvironments, e.g., subsurface pockets or pores, formamide-derived pathways to nucleobases may suffer from low selectivity and yield.

3.3. Orò-Type Polymerization

HCN, i.e., one of the most abundant prebiotic molecules observed in cometary comae, is known to undergo spontaneous polymerization under cryogenic conditions, forming a macromolecular material referred to as HCN polymer or polyamino-cyanomethylene [

30]. This solid-state polymer is stable due to a combination of two factors: i) extensive hydrogen bonding, conjugated structure, and ii) entrapment within water ice matrices, which reduce molecular mobility and degradation in cold environments. The breakdown of this polymer under hydrolytic conditions can produce adenine and potentially other purine derivatives, according to the following overall reactions:

These reactions have attracted significant interest as a possible reservoir mechanism, where biologically relevant molecules are synthesized only upon depolymerization triggered by external stimuli, such as thermal input, water, or catalytic surfaces.

At 200 K the ΔG is approximately -98 kcal mol

-1 and the reaction becomes even more favorable at higher temperatures, reaching values near -130 kcal mol

-1 at 1000 K. This derives both from the aromatic stabilization of adenine and from the increased entropy associated with the release of volatile by-products such as NH₃, CO, and H₂O during breakdown. Despite the thermodynamic driving force, the HCN polymer exhibits kinetic inertness at low temperatures, requiring activation energy input for depolymerization [

31]. This aligns with experiments where heating or aqueous conditions are prerequisites for nucleobase release from HCN polymers. While cometary environments are ideal for polymer preservation, it is the transition to warmer planetary settings that may trigger the formation of prebiotic purines through this pathway. Upon delivery to planetary environments, where liquid water, moderate constant heat, and chemical catalysis are available, the breakdown of preserved HCN polymers could contribute significantly to the pool of nitrogenous bases accessible for early biochemical evolution.

3.4. Cyanamide-Based Reactions

Cyanamide (NH

2CN), another plausible cometary molecule, reacts with glycolaldehyde (HOCH

2CHO) to form intermediates leading to nucleobases

The structural stability of 2-aminooxazole, attributed to its ring closure and intramolecular hydrogen bonding, is significant under cryogenic conditions, where reduced molecular motion enhances the persistence of such intermediates. This makes it a promising candidate for long-lived cometary reservoirs of nucleotide precursors. My thermodynamic calculations reveal that this condensation reaction is endergonic at low temperatures. At 200 K the ΔG is approximately +16 kcal mol

-1, indicating that the reaction is not spontaneous under typical surface conditions of cometary bodies. Even at the lowest evaluated temperature (50 K) the ΔG remains positive, and only at elevated temperatures approaching 1000 K the reaction becomes favorable (

Table 2). The formation of 2-aminooxazole on cometary surfaces is thermodynamically hindered under cold conditions, and would require significant energy input to proceed. Possible activation mechanisms include transient thermal events during perihelion passages, UV-driven photochemistry, and mineral surface catalysis in order to stabilize transition states or facilitate proton transfers. Once formed, 2-aminooxazole is expected to be chemically stable, making it a viable intermediate for further condensation reactions with carbonyl-containing molecules, such as formamide or other aldehydes.

3.5. Formation of Pentose Sugars and Nucleosides/Nucleotides

Two primary pathways have been proposed for pentose sugar formation under prebiotic conditions. The first is the classical Formose reaction, where formaldehyde (H₂CO) undergoes autocatalytic polymerization to ribose:

An alternative pathway involves Glycolaldehyde Polymerization, utilizing glycolaldehyde (HOCH₂CHO):

Our thermodynamic analysis confirms that the formation of ribose from formaldehyde is exergonic under cometary surface conditions, with ΔG, calculated at 200 K, is approximately −76 kcal mol

-1 and even more favorable at higher temperatures. Mineral surfaces such as silicates, or apatite (Ca

5(PO

4)

3[F,OH,Cl]) may further facilitate these reactions by adsorbing intermediates and reducing activation barriers, allowing slow accumulation over long periods. Side reactions are abundant. Formaldehyde and glycolaldehyde are chemically versatile to undergo alternative reactions, including the Cannizzaro reaction, where two H₂CO molecules yield formic acid (HCOOH) and methanol (CH

3OH). In addition, the Formose reaction lacks selectivity, tending to produce complex mixtures of sugars and poly-hydroxy oligomers, with little control over chain length or stereochemistry [

32]. Pentose sugars are labile, prone to racemization and degradation, even under cryogenic conditions. While low temperatures can slow degradation, cometary nuclei experience periodic warming, up to ~ 250 K or more during perihelion, which can accelerate decomposition or isomerization, compromising the preservation of ribose in its biologically relevant forms.

The subsequent synthesis of nucleosides proceeds through condensation reactions, e.g.,:

Our thermodynamic calculations show that reaction (11) is mildly endergonic across cometary-relevant temperatures. At 200 K, ΔG is approximately +3.0 kcal mol-1, decreasing slightly at higher temperatures, e.g., +2.0 kcal mol-1 at 300 K, and becoming marginally exergonic only above ~ 600 - 800 K (-1.0 to -3.0 kcal mol-1). These values indicate that the reaction is close to thermodynamic equilibrium.

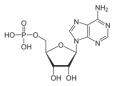

Subsequent phosphorylation, assisted by UV-activated phosphate minerals, leads to nucleotide formation:

Reaction (12), in contrast, is strongly endergonic under all cometary-like conditions. At 200 K the reaction has a ΔG of approximately +66.0 kcal mol-1, and remains energetically unfavorable even at 1000 K (ΔG ≈ +50.0 kcal mol-1). Such high positive values indicate that AMP formation is not thermodynamically viable without substantial energy input. This result is consistent with the biochemistry that modern nucleotide synthesis requires high-energy intermediates and enzymatic catalysis. In prebiotic cometary contexts, only non-equilibrium processes, such as UV-driven phosphate activation, impact-induced heating, or dehydration cycles near perihelion, could provide the energy necessary to overcome the thermodynamic barrier to AMP formation.

4. Discussion

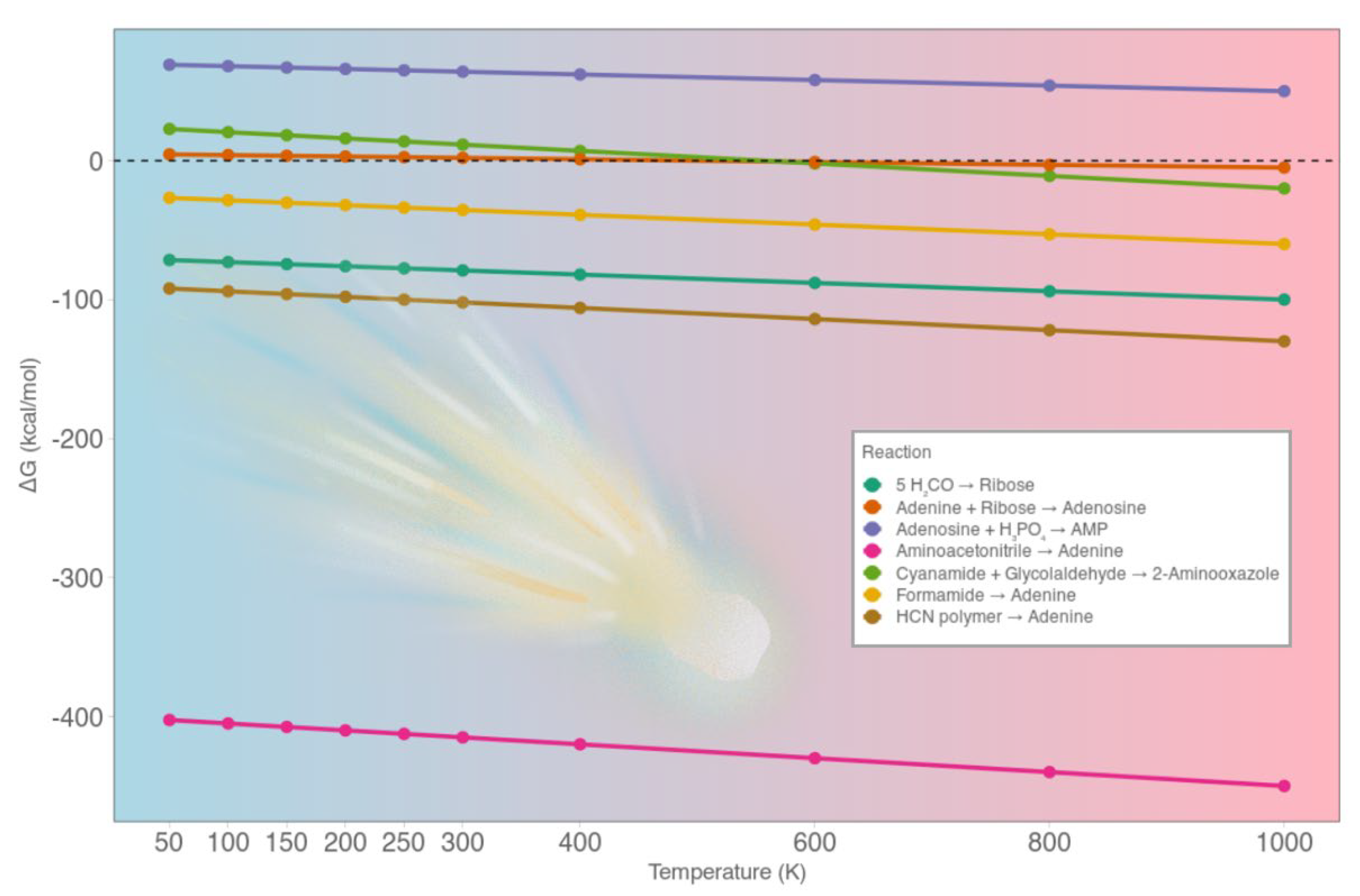

This study provides a thermodynamic evaluation of key reactions leading to nitrogenous bases, sugars, nucleosides, and nucleotides across a wide temperature range (50 - 1000 K) (

Figure 1).

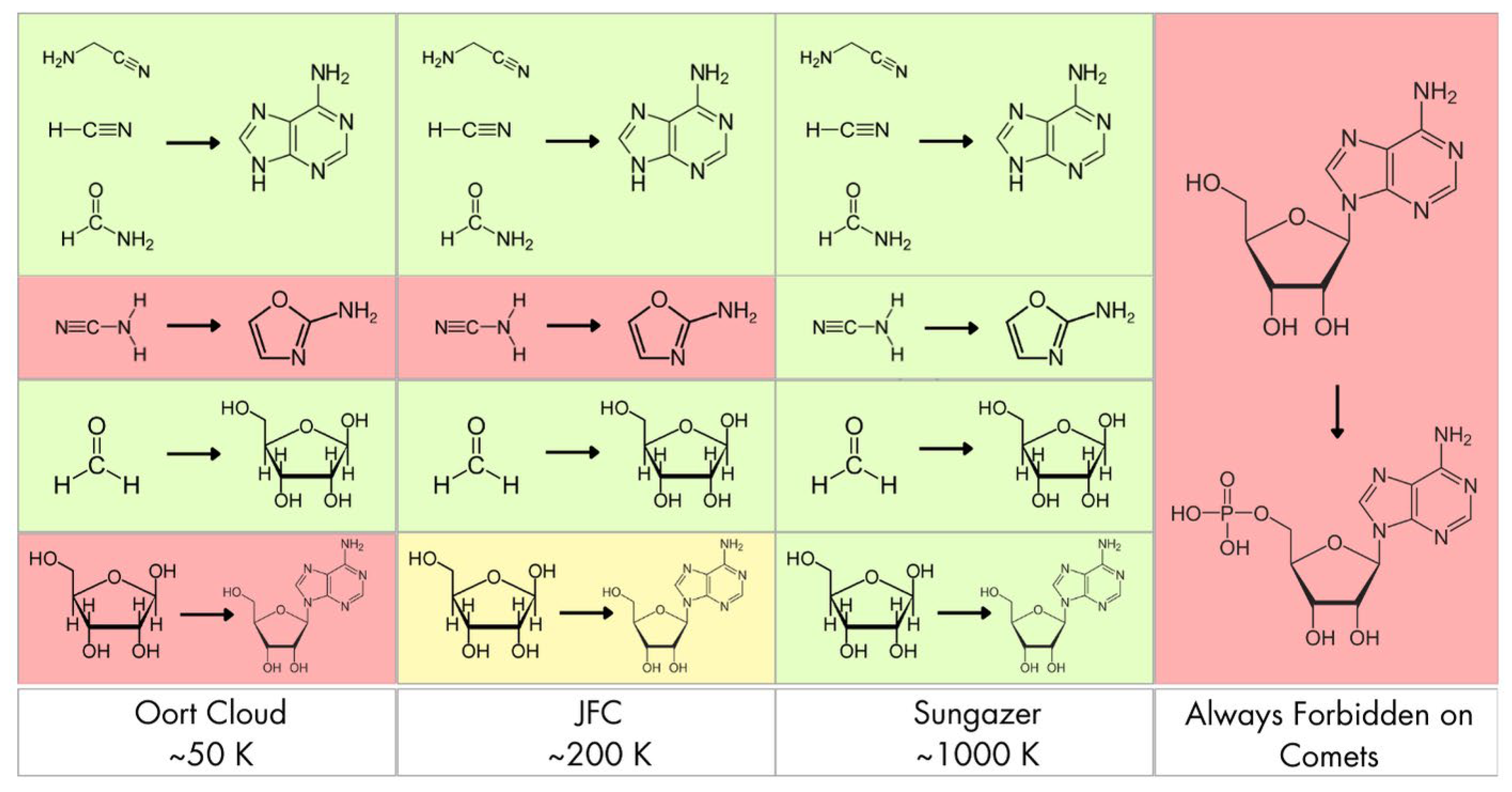

Our results reveal systematic trends that differentiate which types of molecular synthesis are energetically viable under the above mentioned temperatures, compatible with cometary surfaces, and which ones instead require external activation mechanisms or warmer planetary environments. The surface temperature of comets spans orders of magnitude depending on their orbital history and family. Long-period comets originating from the Oort Cloud spend most of their lifetime at cryogenic temperatures (~ 50 K), interrupted by brief warming during solar approaches [

33]. Jupiter Family Comets (JFCs) typically oscillate between 4 - 6 AU and 1 AU, experiencing intermediate thermal cycling (100 – 250 K) [

33]. In contrast, sungrazing comets, such as those in the Kreutz group, can reach surface temperatures exceeding 800 - 1000 K during perihelion [

12]. The thermodynamic feasibility of chemical pathways must therefore be assessed across this full temperature spectrum to reflect actual environmental conditions.

The formation of aromatic nucleobases from simple precursors is consistently thermodynamically favorable across all temperature regimes. The Strecker-type polymerization of aminoacetonitrile to adenine is exergonic (ΔG from -402 kcal mol-1 at 50 K to -450 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K), indicating spontaneous synthesis under even the Oort Cloud conditions. The hydrolysis of HCN polymers to adenine remains highly favorable (ΔG ≈ -92 to -130 kcal mol-1), with increasing exergonicity at higher temperatures due to growing entropy contributions. This suggests that nucleobase accumulation is possible both in the deep freeze of cometary storage and during thermal excursions, with different mechanisms dominating such as the radical polymerization at low T, and the hydrolytic breakdown at higher T, e.g., during perihelion or planetary delivery. The formamide-derived pathway to adenine shows more moderate favorability, transitioning from ΔG ≈ -27 kcal mol-1 at 50 K to ≈ -60 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K. While viable at all temperatures, its efficiency depends on radiation-induced radical chemistry or mineral-assisted activation, particularly in JFCs or during perihelion when radiation flux and moderate heating coincide. Some pathways display a qualitative switch in thermodynamic behavior across the temperature range. This is particularly evident in 2-aminooxazole synthesis from cyanamide + glycolaldehyde, which is endergonic below ~ 600 - 700 K (ΔG ≈ +23 kcal mol-1 at 50 K, +16 kcal mol-1 at 200 K) becoming exergonic at higher temperatures, reaching ΔG ≈ -20 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K. Such temperature sensitivity suggests that pyrimidine precursors could not form during cold storage in Oort Cloud conditions, but might be produced near perihelion or during impact heating. This also highlights the importance of transient heating spikes for enabling select steps in nucleotide assembly, rather than continuous thermal exposure. The autocatalytic polymerization of formaldehyde to ribose via the Formose reaction is exergonic (ΔG from -71.5 kcal mol-1 at 50 K to -100 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K), supporting its thermodynamic on comets. Competing side reactions, e.g., Cannizzaro disproportionation, and selectivity issues reduce the likelihood of accumulating structurally defined pentoses such as ribose. Ribose itself is chemically fragile, especially under warming conditions. While stability is enhanced at low T (Oort Cloud, aphelion of JFCs), perihelion passages or higher temperatures lead to racemization and decomposition, suggesting that sugar synthesis requires cold trapping post-formation, or aqueous reprocessing after delivery. The condensation of adenine and ribose to form adenosine lies near equilibrium (ΔG ≈ +4.5 kcal mol-1 at 50 K to ≈ -5 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K), making it marginally favorable only under strong heating conditions. The slight endergonicity at low T implies that dehydration conditions, e.g., mineral surfaces, UV desorption, or localized heating are essential for driving the reaction. The phosphorylation of adenosine to AMP is, by contrast, thermodynamically prohibited at all temperatures (ΔG from +69 kcal mol-1 at 50 K to +50 kcal mol-1 at 1000 K).

Figure 2.

The plot reports the calculated Gibbs free energy variation (ΔG, kcal mol-1) between 50 and 1000 K for key reaction steps. Temperature increases from left to right according to the color gradient (from blue to red).

Figure 2.

The plot reports the calculated Gibbs free energy variation (ΔG, kcal mol-1) between 50 and 1000 K for key reaction steps. Temperature increases from left to right according to the color gradient (from blue to red).

This supports the idea that cometary environments could not support spontaneous nucleotide formation, and that external energy sources were necessary to achieve nucleotide assembly.

Our findings suggest that comets can serve as chemical incubators for the formation of nitrogenous bases and simple sugars, especially under cold conditions where reactive intermediates are stabilized, and side reactions suppressed. These molecules can accumulate gradually in icy matrices or on mineral surfaces over years. Upon delivery on planetary surfaces, cometary materials experience new environmental regimes: higher constant temperatures (273 - 373 K), pressures of ~ 1 bar, the presence of metallic surfaces, and the presence of liquid water that can activate reactions too slow or thermodynamically hindered in space. Aminoacetonitrile can hydrolyze to glycine, formamide can yield nucleobases more selectively, sugars and nucleobases can condense into nucleosides in aqueous media and phosphate activation may proceed via mineral photochemistry.

5. Conclusions

I performed a quantitative thermodynamic analysis of seven key reactions involved in prebiotic synthesis of nucleobases, sugars, nucleosides, and nucleotides. For each pathway, I computed the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) over a wide temperature range (50 - 1000 K), chosen to reflect the diverse thermal regimes observed across different cometary families: from cryogenic preservation in the Oort Cloud to intense solar heating in sungrazers and perihelion-active Jupiter Family Comets. By systematically mapping ΔG across this spectrum, I capture both cold-trapping potential and temperature-driven reactivity, offering a unified framework for understanding cometary chemistry across evolutionary timescales. Our results reveal strong temperature dependence across all pathways and identify a thermodynamic hierarchy. Several nucleobase-forming reactions are highly exergonic even at cryogenic temperatures e.g., -400 kcal mol-1 at 200 K, while nucleotide assembly remains energetically unfavorable up to 1000 K. These trends help to delineate which molecular classes can be synthesized and accumulated on comets, and which requires post-delivery terrestrial environments for further processing. By integrating cometary temperatures and avoiding ambiguous assumptions, e.g., liquid water phases, this study contributes to clarify the energetic boundaries of prebiotic chemistry in cometary bodies and to the broader understanding of exogenous molecular delivery during the early stages of chemical evolution. Aromatic nucleobase synthesis, e.g., adenine from aminoacetonitrile, formamide, or HCN polymers, is strongly exergonic at all temperatures. These reactions are thermodynamically spontaneous even at 50 K, supporting the idea that cometary environments can enable the synthesis and long-term preservation of nitrogenous bases without requiring solar heating or catalytic input. Sugar synthesis via formaldehyde polymerization (Formose reaction) is also favorable, although side reactions and stereochemical heterogeneity may limit the selective formation of ribose. Ribose stability remains temperature-sensitive, with degradation above ~ 250 K unless buffered by mineral matrices or ice encapsulation. Some reactions, such as 2-aminooxazole formation from cyanamide and glycolaldehyde, exhibit temperature-dependent thermodynamic reversibility, switching from endergonic to exergonic only above ~ 700 K. These results suggest that certain key intermediates in nucleotide synthesis are not accessible under cold storage conditions, but may form during perihelion events or planetary impact heating. Nucleoside formation is near thermodynamic equilibrium at low T (from 50 to 400 K), but becomes exergonic at high temperatures, especially > 700 K. This indicates that modest activation, e.g., UV exposure, mineral dehydration, may be sufficient for progression toward nucleoside assembly in active or post-impact environments. In contrast, phosphorylation to form nucleotides, e.g., AMP, remains strongly endergonic across the entire cometary temperature range, with ΔG consistently above +50 kcal mol-1: unlikely to occur spontaneously on comets, as it requires high-energy input, e.g., from planetary processes.

Cometary environments are well suited for the selective synthesis and preservation of key prebiotic intermediates, including nucleobases and simple sugars, especially under conditions that suppress hydrolysis and oxidative degradation. The completion of nucleotide assembly, required for the emergence of DNA/RNA-based life, would have needed additional energy sources and environmental conditions, likely provided by early Earth or similar planetary environments. This supports a two-phase model of chemical evolution: comets as low-temperature synthetic environments and molecular reservoirs, followed by planetary reprocessing into functional biopolymers.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, L.T.; methodology, L.T.; software, L.T.; validation, L.T.; formal analysis, L.T.; investigation, L.T.; resources, L.T.; data curation, L.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.T.; writing—review and editing, L.T.; visualization, L.T.; supervision, L.T.; project administration, L.T.; funding acquisition, L.T.

Funding

This work was conducted thanks to the following funding: the ASI-INAF agreements I/024/12/0 and 2020-4-HH.0, by the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Astrobiology and Cosmic Physics Laboratory (ACPL) at Parthenope University of Naples for their support in conducting this research, the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF), and all those whose constructive discussions contributed to the formulation of the hypothesis presented in this work, particularly the University of Milan – Bicocca, Prof. Luca De Gioia, and Dr. Federica Arrigoni.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bergman, P.; Lerner, M. S.; Olofsson, A. O. H.; Wirström, E.; Black, J. H.; Bjerkeli, P.; Parra, R.; Torstensson, K. Emission from HCN and CH3OH in Comets - Onsala 20-m Observations and Radiative Transfer Modelling. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 660, A118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biver, N.; Crovisier, J.; Bockelée-Morvan, D.; Szutowicz, S.; Lis, D. C.; Hartogh, P.; Val-Borro, M. de; Moreno, R.; Boissier, J.; Kidger, M.; Küppers, M.; Paubert, G.; Russo, N. D.; Vervack, R.; Weaver, H. Ammonia and Other Parent Molecules in Comet 10P/Tempel 2 from Herschel/HIFI and Ground-Based Radio Observations. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 539, A68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanysek, V.; Wickramasinghe, N. C. Formaldehyde Polymers in Comets. In Astronomical Origins of Life: Steps Towards Panspermia; Hoyle, F., Wickramasinghe, N. C., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2000; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drozdovskaya, M. N.; Schroeder I, I. R. H. G.; Rubin, M.; Altwegg, K.; van Dishoeck, E. F.; Kulterer, B. M.; De Keyser, J.; Fuselier, S. A.; Combi, M. Prestellar Grain-Surface Origins of Deuterated Methanol in Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 500, 4901–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biver, N.; Bockelée-Morvan, D.; Debout, V.; Crovisier, J.; Boissier, J.; Lis, D. C.; Russo, N. D.; Moreno, R.; Colom, P.; Paubert, G.; Vervack, R.; Weaver, H. A. Complex Organic Molecules in Comets C/2012 F6 (Lemmon) and C/2013 R1 (Lovejoy): Detection of Ethylene Glycol and Formamide. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 566, L5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivilla, V. M.; Drozdovskaya, M. N.; Altwegg, K.; Caselli, P.; Beltrán, M. T.; Fontani, F.; van der Tak, F. F. S.; Cesaroni, R.; Vasyunin, A.; Rubin, M.; Lique, F.; Marinakis, S.; Testi, L. ; the ROSINA team. ALMA and ROSINA Detections of Phosphorus-Bearing Molecules: The Interstellar Thread between Star-Forming Regions and Comets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 492, 1180–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goesmann, F.; Rosenbauer, H.; Bredehöft, J. H.; Cabane, M.; Ehrenfreund, P.; Gautier, T.; Giri, C.; Krüger, H.; Le Roy, L.; MacDermott, A. J.; McKenna-Lawlor, S.; Meierhenrich, U. J.; Caro, G. M. M.; Raulin, F.; Roll, R.; Steele, A.; Steininger, H.; Sternberg, R.; Szopa, C.; Thiemann, W.; Ulamec, S. Organic Compounds on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko Revealed by COSAC Mass Spectrometry. Science 2015, 349, aab0689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.; Ferretti, S.; Piccirillo, A. M.; Zakharov, V.; Di Paolo, F.; Rotundi, A.; Ammannito, E.; Amoroso, M.; Bertini, I.; Di Donato, P.; Ferraioli, G.; Fiscale, S.; Fulle, M.; Inno, L.; Longobardo, A.; Mazzotta-Epifani, E.; Muscari Tomajoli, M. T.; Sindoni, G.; Tonietti, L.; Rothkaehl, H.; Wozniakiewicz, P. J.; Burchell, M. J.; Alesbrook, L. A.; Sylvest, M. E.; Patel, M. R. DISC - the Dust Impact Sensor and Counter on-Board Comet Interceptor: Characterization of the Dust Coma of a Dynamically New Comet. Adv. Space Res. 2023, 71, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Pulletikurti, S.; Yerabolu, J. R.; Krishnamurthy, R. Cyanide as a Primordial Reductant Enables a Protometabolic Reductive Glyoxylate Pathway. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewitt, D.; Luu, J.; Li, J. Demise of Kreutz Sungrazing Comet C/2024 S1 (ATLAS). Astron. J. 2025, 169, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousov, D. V.; Pavlov, A. K. Cometary Outbursts in the Oort Cloud. Icarus 2024, 415, 116066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, W. F.; Boice, D. C. Comets as a Possible Source of Prebiotic Molecules. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1991, 21, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotavera, B.; Taatjes, C. A. Influence of Functional Groups on Low-Temperature Combustion Chemistry of Biofuels. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2021, 86, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, P. P.; Stein, T.; Head-Gordon, M.; Lee, T. J. Mechanisms of the Formation of Adenine, Guanine, and Their Analogs in UV-Irradiated Mixed NH3:H2O Molecular Ices Containing Purine. Astrobiology 2017, 17, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. K.; Zhu, C.; La Jeunesse, J.; Fortenberry, R. C.; Kaiser, R. I. Experimental Identification of Aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH)—the Key Intermediate in the Strecker Synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biver, N.; Bockelée-Morvan, D.; Moreno, R.; Crovisier, J.; Colom, P.; Lis, D. C.; Sandqvist, A.; Boissier, J.; Despois, D.; Milam, S. N. Ethyl Alcohol and Sugar in Comet C/2014 Q2 (Lovejoy). Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundi, A.; Rietmeijer, F. J. M.; Ferrari, M.; Della Corte, V.; Baratta, G. A.; Brunetto, R.; Dartois, E.; Djouadi, Z.; Merouane, S.; Borg, J.; Brucato, J. R.; Le Sergeant d’Hendecourt, L.; Mennella, V.; Palumbo, M. E.; Palumbo, P. Two Refractory Wild 2 Terminal Particles from a Carrot-Shaped Track Characterized Combining MIR/FIR/Raman Microspectroscopy and FE-SEM/EDS Analyses. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2014, 49, 550–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuth, J. A.; Johnson, N. M. Crystalline Silicates in Comets: How Did They Form? Icarus 2006, 180, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietmeijer, F. J. M. Sulfides and Oxides in Comets. Astrophys. J. Part 2 - Lett. 1988, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C. P.; Davies, P. C. W.; Worden, S. P. Directed Panspermia Using Interstellar Comets. Astrobiology 2022, 22, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, M. P.; Allamandola, L. J.; Sandford, S. A. Complex Organics in Laboratory Simulations of Interstellar/Cometary Ices. Adv. Space Res. Off. J. Comm. Space Res. COSPAR 1997, 19, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerio-Goates, Juliana; Francis, Michael R.; Goldberg, Robert N.; Ribeiro da Silva, Manuel A. V.; Ribeiro da Silva, Maria D. M. C.; Tewari, Y. B. Thermochemistry of Adenosine. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2001, 33, 929–947. [CrossRef]

- Galimova, G. R.; Medvedkov, I. A.; Mebel, A. M. The Role of Methylaryl Radicals in the Growth of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: The Formation of Five-Membered Rings. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, E.; Kolesniková, L.; Bialkowska, E.; Kisiel, Z.; león, I.; Guillemin, J.; Alonso, J. Glycinamide, a Glycine Precursor, Caught in the Gas Phase: A Laser-Ablation Jet-Cooled Rotational Study. Astrophys. J. 2018, 861, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, D.; Toubin, C.; Peslherbe, G.; Hynes, J. A Theoretical Study of the Formation of the Aminoacetonitrile Precursor of Glycine on Icy Grain Mantles in the Interstellar Medium. J. Phys. Chem. C - J PHYS CHEM C 2008, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, J. P.; Ertem, G.; Agarwal, V. K. The Adsorption of Nucleotides and Polynucleotides on Montmorillonite Clay. Orig. Life Evol. Biosphere J. Int. Soc. Study Orig. Life 1989, 19, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, R.; Crestini, C.; Ciciriello, F.; Pino, S.; Costanzo, G.; Di Mauro, E. From Formamide to RNA: The Roles of Formamide and Water in the Evolution of Chemical Information. Res. Microbiol. 2009, 160, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirásek, M.; Rickhaus, M.; Tejerina, L.; Anderson, H. L. Experimental and Theoretical Evidence for Aromatic Stabilization Energy in Large Macrocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladino, R.; Crestini, C.; Ciciriello, F.; Costanzo, G.; Di Mauro, E. Formamide Chemistry and the Origin of Informational Polymers. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 694–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Bermejo, M.; de la Fuente, J. L.; Pérez-Fernández, C.; Mateo-Martí, E. A Comprehensive Review of HCN-Derived Polymers. Processes 2021, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafañe-Barajas, S. A.; Ruiz-Bermejo, M.; Rayo-Pizarroso, P.; Colín-García, M. Characterization of HCN-Derived Thermal Polymer: Implications for Chemical Evolution. Processes 2020, 8, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitkreuz, C. F.; Burger, J.; Hasse, H. Solubility of Formaldehyde in Mixtures of Water + Methanol + Poly(Oxymethylene) Dimethyl Ethers. Fluid Phase Equilibria 2023, 565, 113658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkotsinas, A.; Guilbert-Lepoutre, A.; Raymond, S. N.; Nesvorny, D. Thermal Processing of Jupiter-Family Comets during Their Chaotic Orbital Evolution. Astrophys. J. 2022, 928, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).