1. Introduction

Mechanochemistry makes uses of mechanochemical energy to promote chemical reactions (André et al., 2021). Despite its applicability in a variety of fields, as for greener synthetic approaches (Liu et al., 2022), mechanochemistry could be also applied to the degradation of organic molecules (Kaupp, 2009; Zhou et al., 2023). Many compounds contain a mechanophore, which is a portion of a molecule that follows a known degradation pattern (Li et al., 2015), which could aid in the elucidation of degradation mechanisms, e.g. applied to biomolecules.

In modern biology, ribonucleosides are the building blocks of several biomolecules, as for ribonucleic acid (RNA) present in all living organisms and their stability is directly related to the N-glycosidic bond. Acid/base-catalysed hydrolysis, thermal, and photodegradation of ribonucleosides, with nucleobase preservation, exemplify N-glycosidic bond reactivity (Cataldo, 2018; Rios et al., 2015; Wang and You, 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Some inorganic ions could also promote the degradation of ribose, as carbonate, while other ions, such as borate, could protect it (Amaral et al., 2008; Franco and da Silva, 2021; Ricardo et al., 2004). It’s known that D-ribose interacts with many different metal ions (Bandwar and Rao, 1997; Yang et al., 2002), which could induce ribose, and consequently, ribonucleoside degradation, although there is not a direct evidence for this statement.

Herein, we propose a novel approach for the degradation of biomolecules, such as ribonucleosides, into their respective more stable entities (for this case, nucleobases), based on mechanochemical induced reactions by metals and inorganic ions (nickel and carbonate ions for this particularly studies). This can be applied as model to analyse content of extra-terrestrial samples with organic molecules, as well as to eliminate some compounds in terrestrial material.

2. Materials and Methods

In this experimental work, all the reagents were handled without further purification: guanosine (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), uridine (Alfa Aesar, 99%), guanine (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%), uracil (Alfa Aesar, 99%), sodium carbonate (J. T. Baker, 99.7%), nickel chloride hexahidrate (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) and sodium chloride (NaCl, Panreac, 99.5%)

2.1. Milling Process

Reactants were pre-ground using mortar and pestle, dried and then ground in a Retsch MM400 ball mill, operated at 29 Hz, for a total time of 6 h (four cycles of 1.5 h). Two 7 mm balls were added to each 10 mL stainless steel reactor. The neat-grinding studies were conducted with: 1) mixture of ribonucleoside (guanosine or uridine) nickel chloride, NiCl2.6H2O and sodium carbonate, Na2CO3, in a 1:4:4 proportion, respectively (samples were dried prior to mechanochemical treatment); 2) mixture of ribonucleoside (guanosine or uridine) and sodium chloride, NaCl, in a 1:4 proportion to verify the contribution of this salt for the degradation of ribonucleosides.

2.2. HPLC analysis

The samples were also analysed on a UltiMate™ 3000 Standard (SD) HPLC, composed of a quaternary pump LPG-3400SD, an autosampler WPS-300SL and a column oven TCC-3000SD coupled in-line to diode-array detector, DAD-3000. Aliquots were injected into the column via a Rheodyne injector with a 100 μL loop, in the in-line split-loop mode. Separations were conducted with a Luna C18 100 Ǻ (250 x 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm) at 40 ºC, using a flow rate of 0.3 mL.min-1, a mobile phase of formic acid 0.1% at pH 4.00 (eluent A) and acetonitrile (eluent B), using two different conditions: Run 1 – 99% A and 1% B (0-25 min), 95% A and 5% B (25-55 min), 99% A and 1% B (55-60 min); Run 2 - 100% A (0-10 min), 99% A and 1% B (10-20 min), 98% A and 2% B (20-30 min), 95% A and 5% B (30-50 min) and 100% A (50-60 min). The previous conditions are optimised for all canonical nucleobase and nucleoside separation.

2.3. NMR spectroscopy analysis

1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy spectra were acquired in a 400 MHz Avance III Bruker Ultra Shield spectrometer, equipped with a 5 mm BBO probe, at room temperature, by using a mixture of water and deuterium oxide (D2O, Eurisotop, 99.9%, δ = 4.79) or dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DMSO-d6, Eurisotop, 99.8%, δ = 2.5) as solvents. The spectra were analysed on TopSpin 3.6.4 software (academic license). In all samples, sonochemistry with Transsonic T460 Elma ultrasound equipment was used due to solubilisation constrains.

2.4. Theoretical Calculations

All theoretical calculations were of the density functional theory (DFT) type, carried out using GAMESS-US version R3. B3LYP (Schmidt et al., 1993) functional was used in ground state calculations, while the range separated CAMB3LYP was used in the excited state TDDFT calculations. A 6-31G** basis set was used in either DFT or TDDFT calculations. The saddle points for transition states were optimised using Hessians calculated by the Couple Perturbed Hartree Fock Method and the negative eigenvalue following algorithm. The optimised geometries were checked for the appropriate number of zero/negative eigen values.

3. Results

3.1. Mechanochemical degradation studies of guanosine and uridine

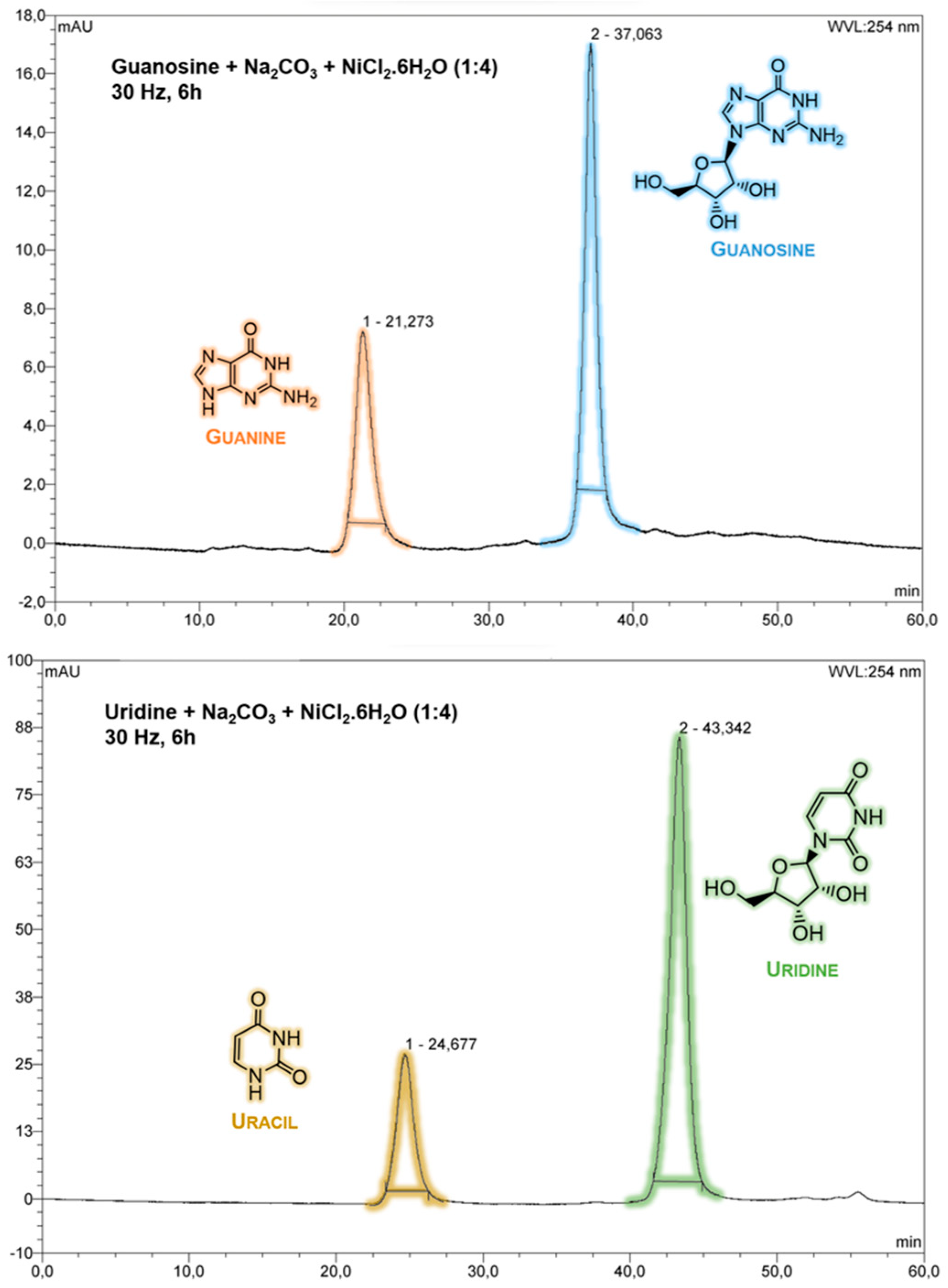

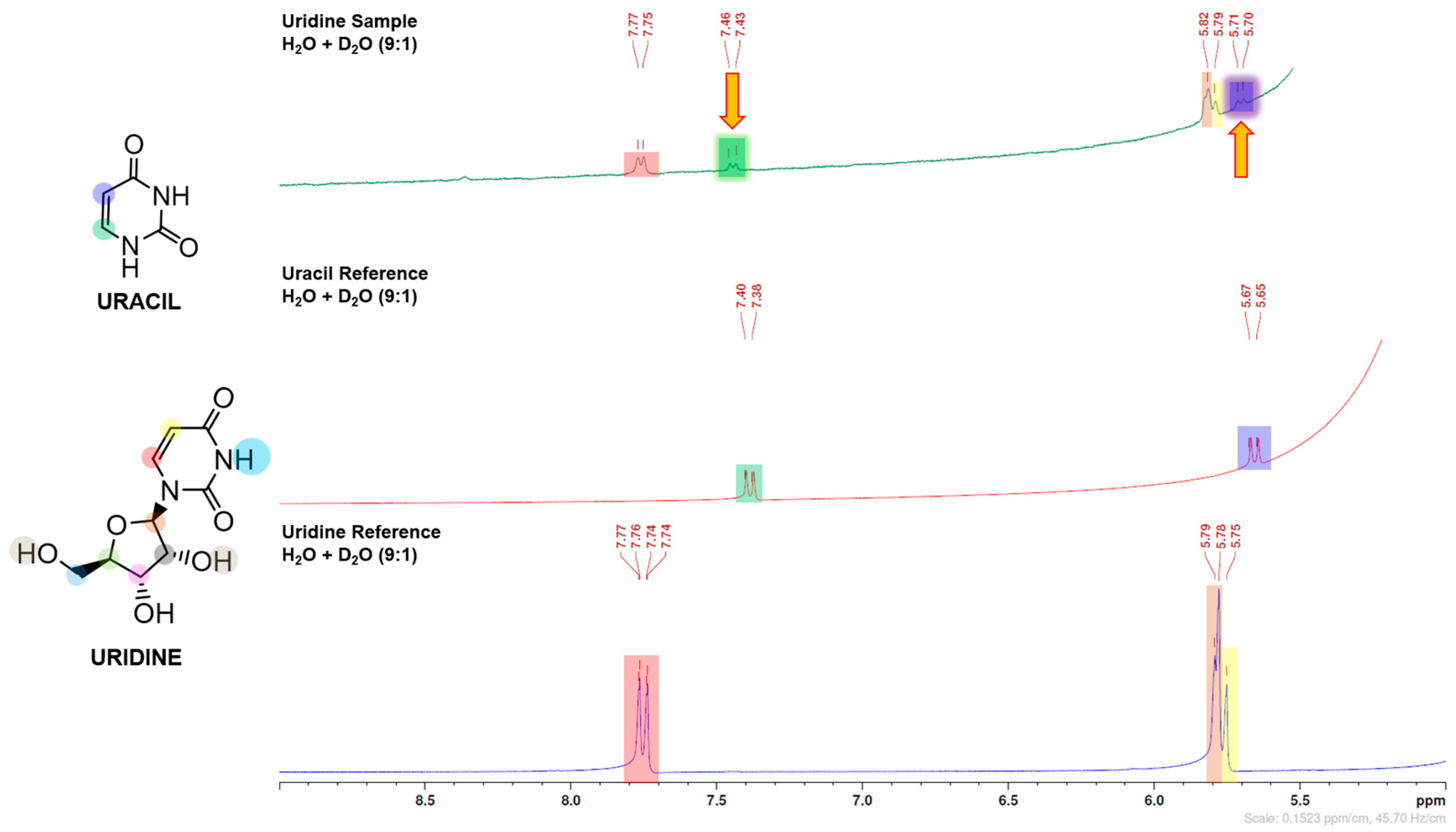

In this work, purine (guanosine) and pyrimidine (uridine) canonical ribonucleosides were studied. After mechanochemical treatment, the samples containing nickel(II) and carbonate changed from a light green colour to a very dark brown, (S1) and from HPLC and NMR data, there was direct evidence of ribonucleoside degradation with nucleobase preservation (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2)

A low resolution spectrum of the guanosine sample containing nickel(II) and carbonate was acquired by 13C NMR using DMSO-d6 as solvent, due, probably to the slight solubility of guanine. Nevertheless, a small signal seems to indicate the presence of nucleobase. This spectrum is not show due to its low quality.

3.2. Ribonucleoside reactivity and degradation mechanism by DFT calculations.

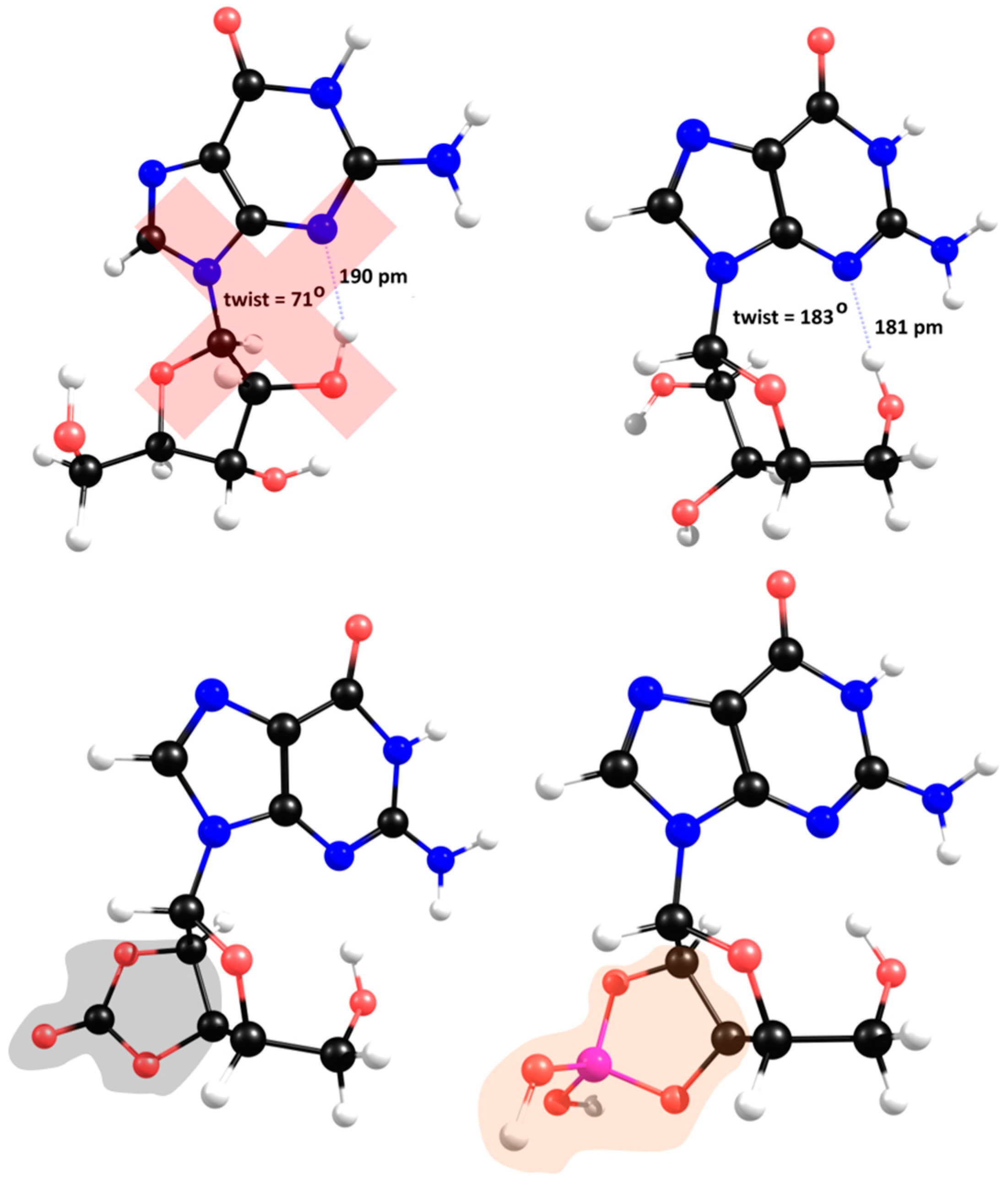

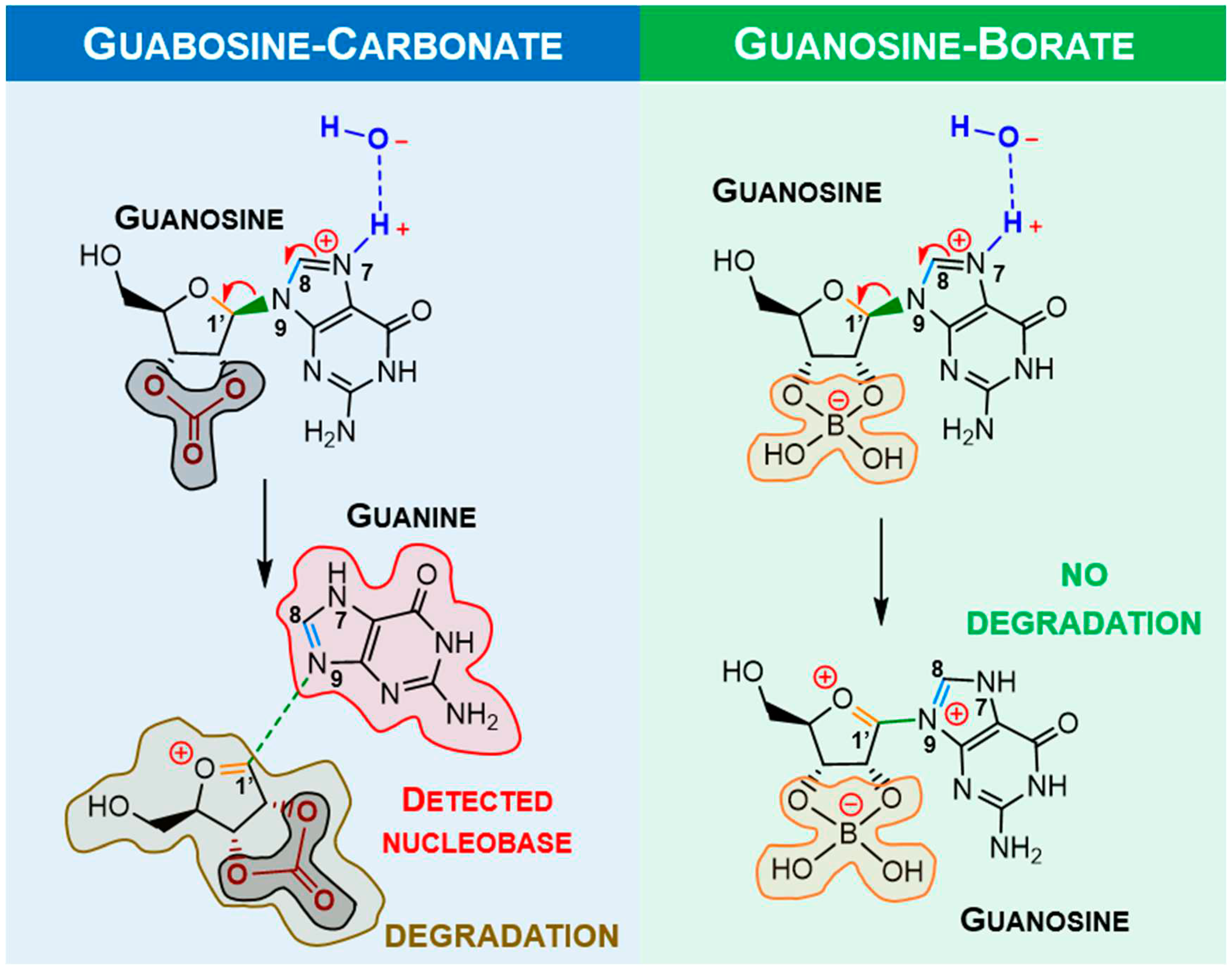

In all ribonucleosides analysed ribose fragments were chosen to have a

β conformation, which is the present in biomolecules. The glycosyl linkage introduces conformational complexity due to the possibility of tortional rotation between ribose and the nitrogenous base. For single molecule starting geometries, the X-ray structure of a π-π-stacked guanosine dimer was used as reference (S4) (Thewalt et al., 1970). In the solid state each half of the dimer depicts a different twist angle and after DFT optimisation the two stable conformers are within a 10 kJ/mol energy range (

Figure 3,

upper structures). The most interesting feature of the lower energy conformers is the existence of a hydrogen bond between a hydroxyl group and the imine nitrogen atom of the nucleobase. However, in the presence of inorganic ions such as carbonate or borate, ribose loses its

syn-hydroxyl groups, breaking the hydrogen bond, which leaves only the methoxy group available to H-bind the imine nitrogen atom (

Figure 3,

upper right).

The stereochemistry of the only conformer in borate/carbonate compounds (

Figure 3,

bottom structures) favours

β-elimination of the purine base and the formation of a double bond in the ribose 5-membered ring (E

2 type reaction). The mechanism proceeds through a saddle point in the Potential Energy Surface (PES) resulting from a proton transfer. However, the DFT energetics shows that this kind of mechanism is not favourable both kinetically and thermodynamically (

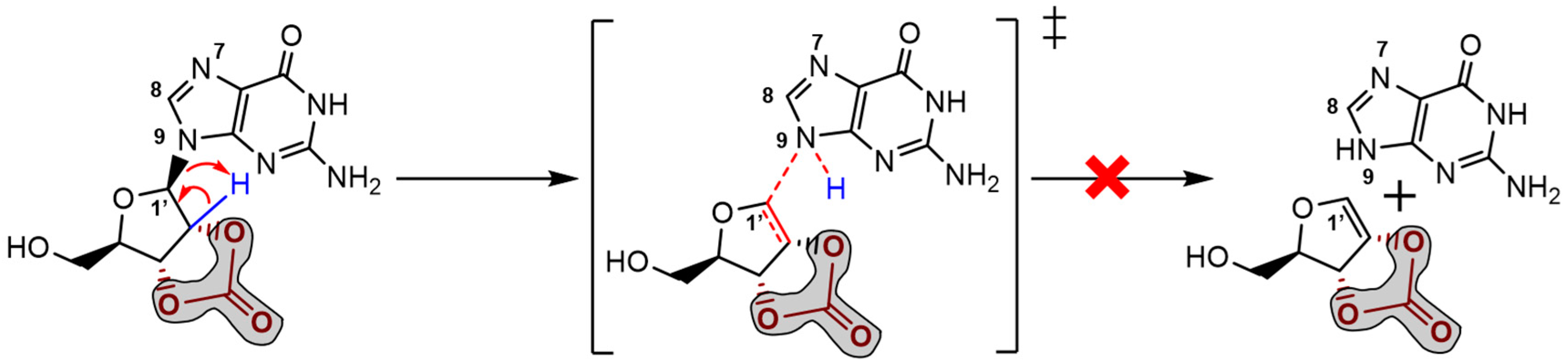

Figure 4).

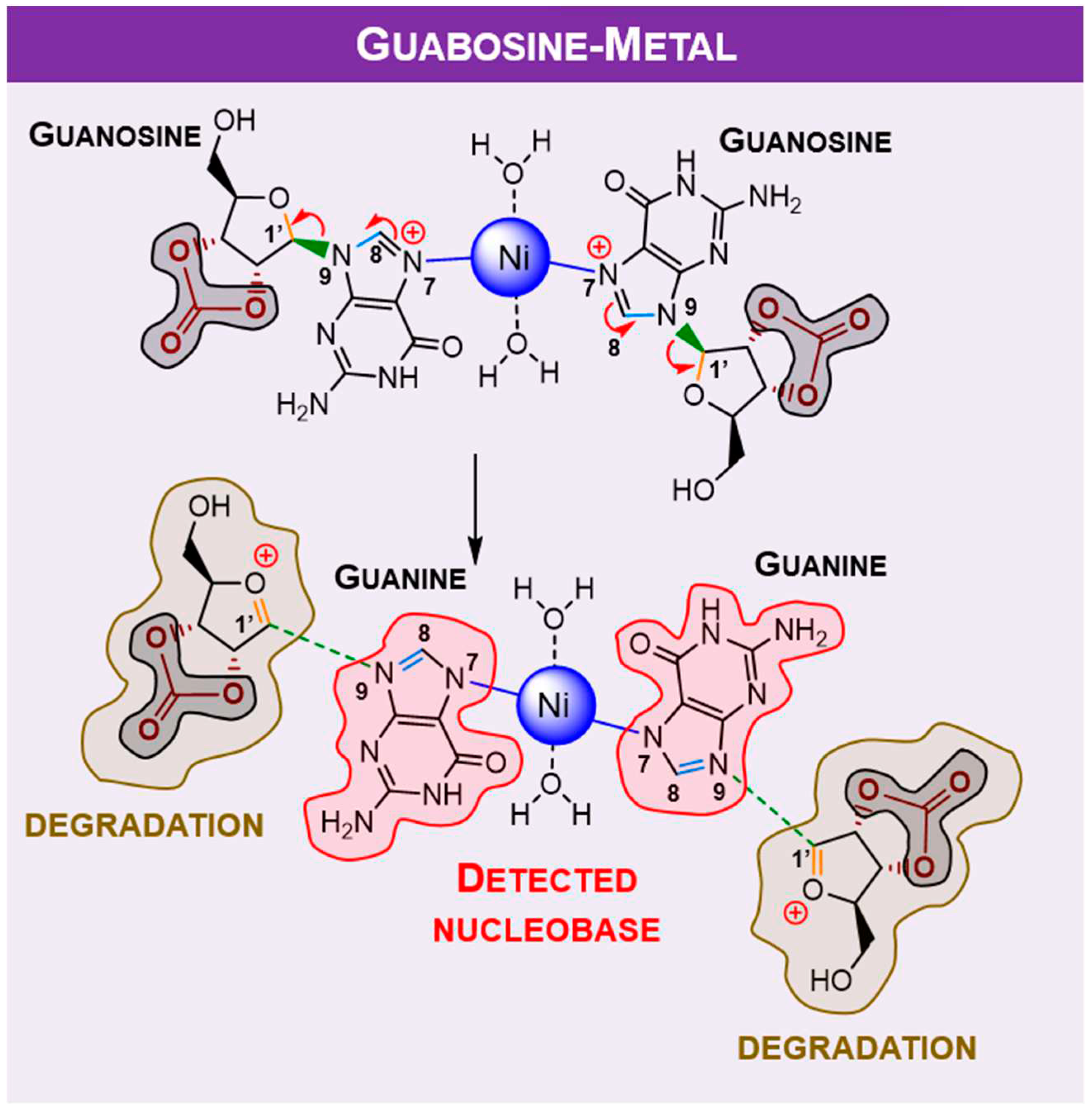

Alternatively, it was considered protonation (supplied by water) and metal assisted mechanism involving positively charged ribonucleoside. The traditional proton/metal interaction in the furanose oxygen atom followed by ring opening was found (by DFT) to be highly unfavourable when compared to identical binding at guanosine

N7 position. Some selected optimised bond lengths are shown in

Table 1, to provide evidence of labialisation of the glycosylic linkage in carbonate, opposed to borate. The observed shortening and lengthening’s of bonds are compatible with the labialisation/strengthening evolution depicted

Figure 5 and summarised in

Table 1.

Since the degradation reaction containing borate bound to the sugar moiety should not happen, metal complexation with guanosine was only calculated for carbonate moiety (

Figure 6), and summarised in

Table 2.

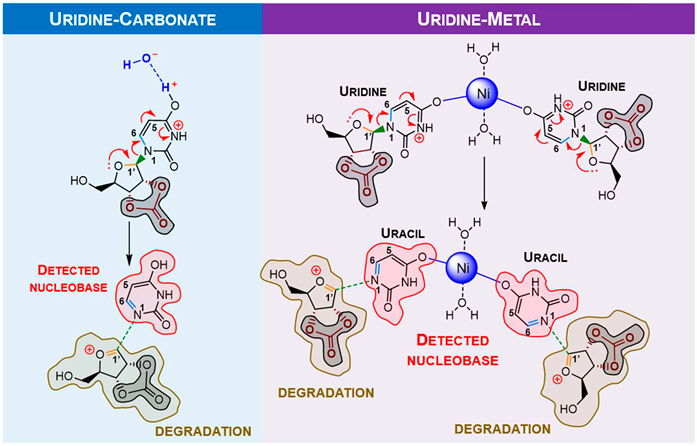

To study the observed behaviour with pyrimidine analogues, calculations for uridine were conducted. Assuming the “protective” behaviour of borate, uridine calculations were developed considering carbonate moiety. In this case, the most stable conformer is also defined by an H-bond to the sugar hydroxyl (S5).

4. Discussion

Guanosine and uridine mechanochemical degradation, in the presence of nickel chloride and sodium carbonate was achieved. Attempts with nickel carbonate, NiCO3 were performed, however, without significant results, mainly because the availability of both nickel and carbonate ions were not enough under our mechanochemical experimental conditions. Sodium chloride, NaCl, was also tested to evaluate the contribution of chloride, but a substantial degradation was not observed to both ribonucleosides (S2).

DFT predictions demonstrate that single species hydrogen (which comes from water, widely present in terrestrial and extra-terrestrial samples) or metal ion assisted degradation of ribonucleosides with nucleobase preservation is plausible, which goes along with the obtained results from mechanochemical studies. Carbonate can be considered as an “activator”, while proton (provided by water)/ nickel as ”mediators” for ribonucleoside degradation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, ribonucleoside degradation with nucleobase preservation was observed with low shock/collision energy, in the presence of nickel(II) and carbonate ions. This implies that environments with high mechanochemical activity might contribute for the degradation of organic content, where metals and inorganic ions could also have a role. Nevertheless, the applied mechanochemical energy in these experiments is nowhere near real shock/collision scenarios. We identify nickel as mediator of degradation reaction by mechanochemistry and this capacity is releated with nickel being a good Lewis acid. The other contributor is carbonate, a derivative of carbon dioxide, a molecule whose amount should decreased in order to avoid massive environment problems. Either way, the degradation of biomolecules is directly related to the complexity of the sample, therefore, many chemical entities may contribute for its degradation.

Mechanochemical degradation of polymers and pollutants is already studied (Cagnetta et al., 2016), however, further applications in the areas of chemistry and geochemistry might be worth exploring. For instance, the formation of asteroids, meteoroids and meteorites are one good example of extreme mechanochemical activity (Bischoff et al., 2006; Ryan, 2000; Silber et al., 2018), which, allied with the high chemical complexity of samples, could promote the degradation of several organic molecules. Minerals containing both nickel and carbonate have been detected among meteorites, although being direct products of sample weathering (Rubin, 1997). Nevertheless, minerals containing cationic nickel have also been detected (Goryunov et al., 2023; Rubin and Ma, 2017). This unexplored pathway could give us some insight into the astrobiology of meteorites and returned samples, as for the prebiological evolution. Since the direct condensation of ribose and nucleobase has not been yet obtained from a prebiotic standpoint, hence, this might suggest that nucleobases with extra-terrestrial origin can be the degradation product, instead of the starting material for ribonucleoside prebiological synthesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Pedro Pinheiro, from Centro de Química Estrutural, for all his availability to help us with HPLC analyses. This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Portuguese Agency for Scientific Research, through the program UIDB/00100/2020 and UIDP/00100/2020, IMS through - LA/P/0056/2020 and contract CEECIND/00283/2018.

References

- Amaral, A.F.; Marques, M.M.; da Silva, J.A.L.; da Silva, J. Interactions of D-ribose with polyatomic anions, and alkaline and alkaline-earth cations: possible clues to environmental synthesis conditions in the pre-RNA world. New J. Chem. 2008, 32, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, V.; Duarte, M.T.; Gomes, C.S.B.; Sarraguça, M.C. Mechanochemistry in Portugal—A Step towards Sustainable Chemical Synthesis. Molecules 2021, 27, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandwar, R.P.; Rao, C.P. Transition metal–saccharide chemistry and biology: An emerging field of multidisciplinary interest. Current Science 1997, 72, 788–796. [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff, A., Scott, E.R.D., Metzler, K. and Goodrich, C.A. Nature and Origins of Meteoritic Breccias, in: Lauretta, D.S., McSween, H.Y. (Eds.), Meteorites and the Early Solar System II, 2006; pp 679.

- Cagnetta, G.; Robertson, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, K.; Yu, G. Mechanochemical destruction of halogenated organic pollutants: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 313, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cataldo, F. Radiolysis and radioracemization of RNA ribonucleosides: implications for the origins of life. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 318, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; da Silva, J.A.L. Boron in Prebiological Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 10458–10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryunov, M.V.; Maksimova, A.A.; Oshtrakh, M.I. Advances in Analysis of the Fe-Ni-Co Alloy and Iron-Bearing Minerals in Meteorites by Mössbauer Spectroscopy with a High Velocity Resolution. Minerals 2023, 13, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaupp, G. Mechanochemistry: The varied applications of mechanical bond-breaking. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nagamani, C.; Moore, J.S. Polymer Mechanochemistry: From Destructive to Productive. Accounts Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2181–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, X.; Chen, N.; Bai, S.; He, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C. A Review on Mechanochemistry: Approaching Advanced Energy Materials with Greener Force. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2108327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo, A.; Carrigan, M.A.; Olcott, A.N.; Benner, S.A. Borate Minerals Stabilize Ribose. Science 2004, 303, 196–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, A.C.; Yu, H.T.; Tor, Y. Hydrolytic Fitness of N-glycosyl Bonds: Comparing the Deglycosylation Kinetics of Modified, Alternative, and Native Nucleosides. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2015, 28, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, A.E. Mineralogy of meteorite groups. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 1997, 32, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.E.; Ma, C. Meteoritic minerals and their origins. Geochemistry 2017, 77, 325–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.V. Asteroid Fragmentation and Evolution of Asteroids. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2000, 28, 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.W.; Baldridge, K.K.; Boatz, J.A.; Elbert, S.T.; Gordon, M.S.; Jensen, J.H.; Koseki, S.; Matsunaga, N.; Nguyen, K.A.; Su, S.; et al. General atomic and molecular electronic structure system. J. Comput. Chem. 1993, 14, 1347–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, E.A.; Boslough, M.; Hocking, W.K.; Gritsevich, M.; Whitaker, R.W. Physics of meteor generated shock waves in the Earth’s atmosphere – A review. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 62, 489–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewalt, U.; Bugg, C.E.; Marsh, R.E. The crystal structure of guanosine dihydrate and inosine dihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1970, 26, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.-J.; You, J.-Z. Study on the molecular structure and thermal stability of purine nucleoside analogs. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 111, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-J.; You, J.-Z. Study on the molecular structure and thermal stability of pyrimidine nucleoside analogs. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2015, 120, 1009–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Zhou, L.X.; Zhang, Y.F. Theoretical Study on the Interaction between β-D-ribose(RI) and Bivalent and Monovalent Cations. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 2002, 18, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hsu, T.; Wang, J. Mechanochemical Degradation and Recycling of Synthetic Polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).