Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Methods

- Literature review of existing digital maturity assessment models with a focus on SMEs.

- Definition of guidelines and objectives for the development of a new model tailored to industrial SMEs in the given environment.

- Conceptual design of the model.

- Development and refinement of the model with the involvement of relevant academic and industry experts.

- Validation of the model using a case study.

- Analysis of the results obtained and recommendations for future research.

2.1. Systematic Literature Review (SLR)

2.2. Definition of the Basic DMM

- Complete comprehensibility for the user in both descriptions and calculations of the DMM.

- A set of dimensions corresponding to the current state of digital maturity in Croatia and the Balkan region.

- Maturity levels adapted to the regional digital maturity landscape.

- The number and content of elements per dimension correlated with the findings from the literature and the current maturity levels.

- The total number of dimension items was limited to 70 to ensure that the assessments could be completed within 90 minutes.

- Simple determination of the importance of the dimensions using a multi-criteria decision making method (MCDM).

- Possibility to assign differentiated importance to items within a dimension.

- Easy scalability, allowing the addition of new dimensions and items.

- Use of commonly available tools (MS Office) in the initial development phase.

- Potential for future upgrades to a web-based interface.

| Maturity level | Description |

|---|---|

|

The company has no or only a minimal strategy for DT. Digitalization activities are carried out on an ad hoc basis, without a clear structure or alignment with the company’s goals. This phase is characterized by a lack of planning, informal processes and limited or non-existent digital resources. |

|

Fundamental digital initiatives are underway. There is an organizational interest in digitalization, but the activities are not yet fully integrated into the corporate strategy. In this phase, there are initial digital strategies, isolated projects and a low level of digital competence among employees. |

|

There are structured digital initiatives with clear strategies for the introduction of technology. Business processes and digital tools are gradually integrated, supported by clearly defined digitalization goals and targeted investments in technology. Formal processes are in place for the development of digital capabilities and the company aligns its digital strategies with overall business objectives, creating a solid foundation for the further development of DT. |

|

Digital strategies and technologies are fully integrated into the business processes. The company uses data and technology to optimize business performance. Leadership plays a central role in driving DT, which is characterized by a high degree of technology integration, extensive use of analytics and data-driven decisions, and a robust digital infrastructure to support business processes. |

|

Given the current average maturity level of SMEs and the significant gap between existing capabilities and the skills required for advanced Industry 4.0 maturity, this stage is intentionally omitted at this stage. |

3. Results

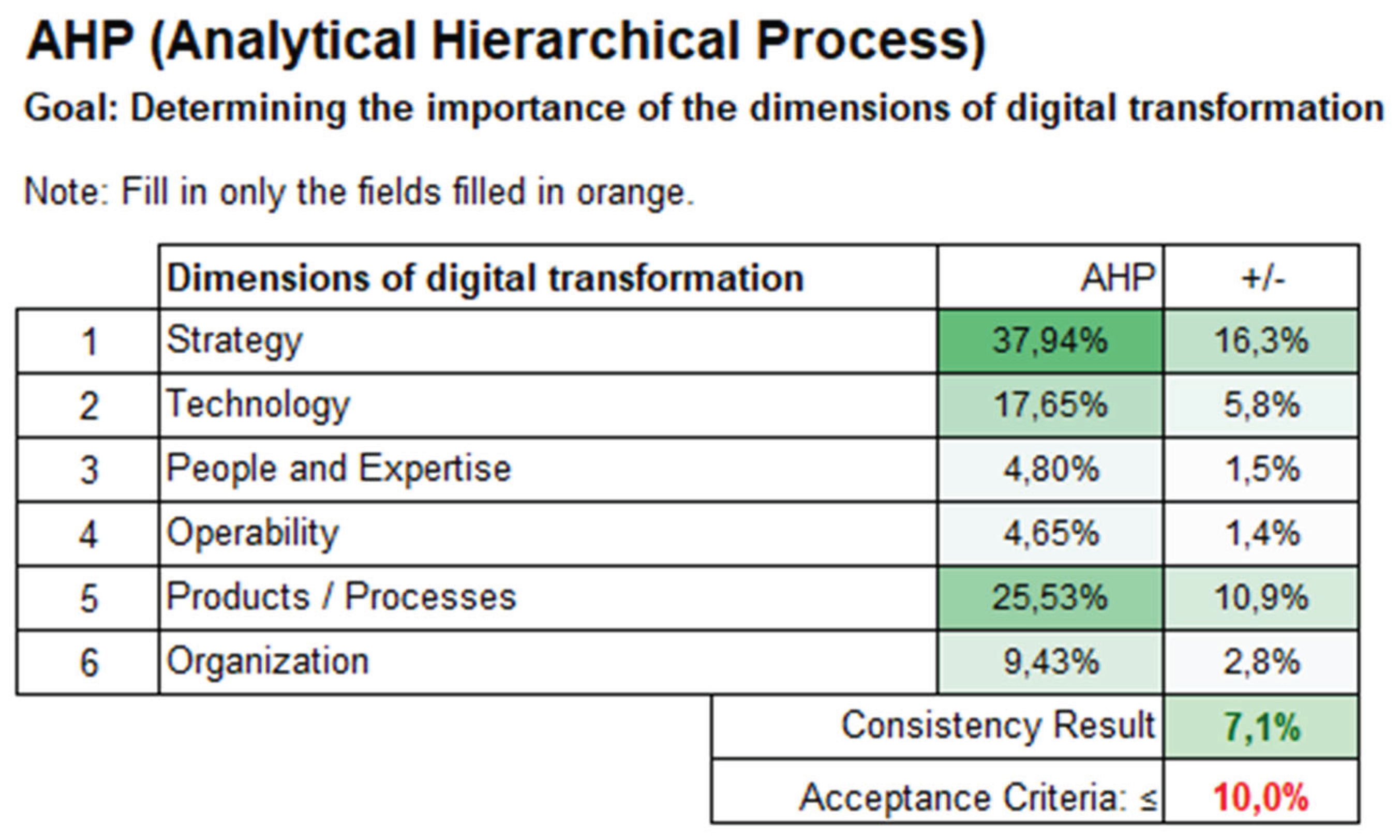

3.1. Determination of Dimension Weights

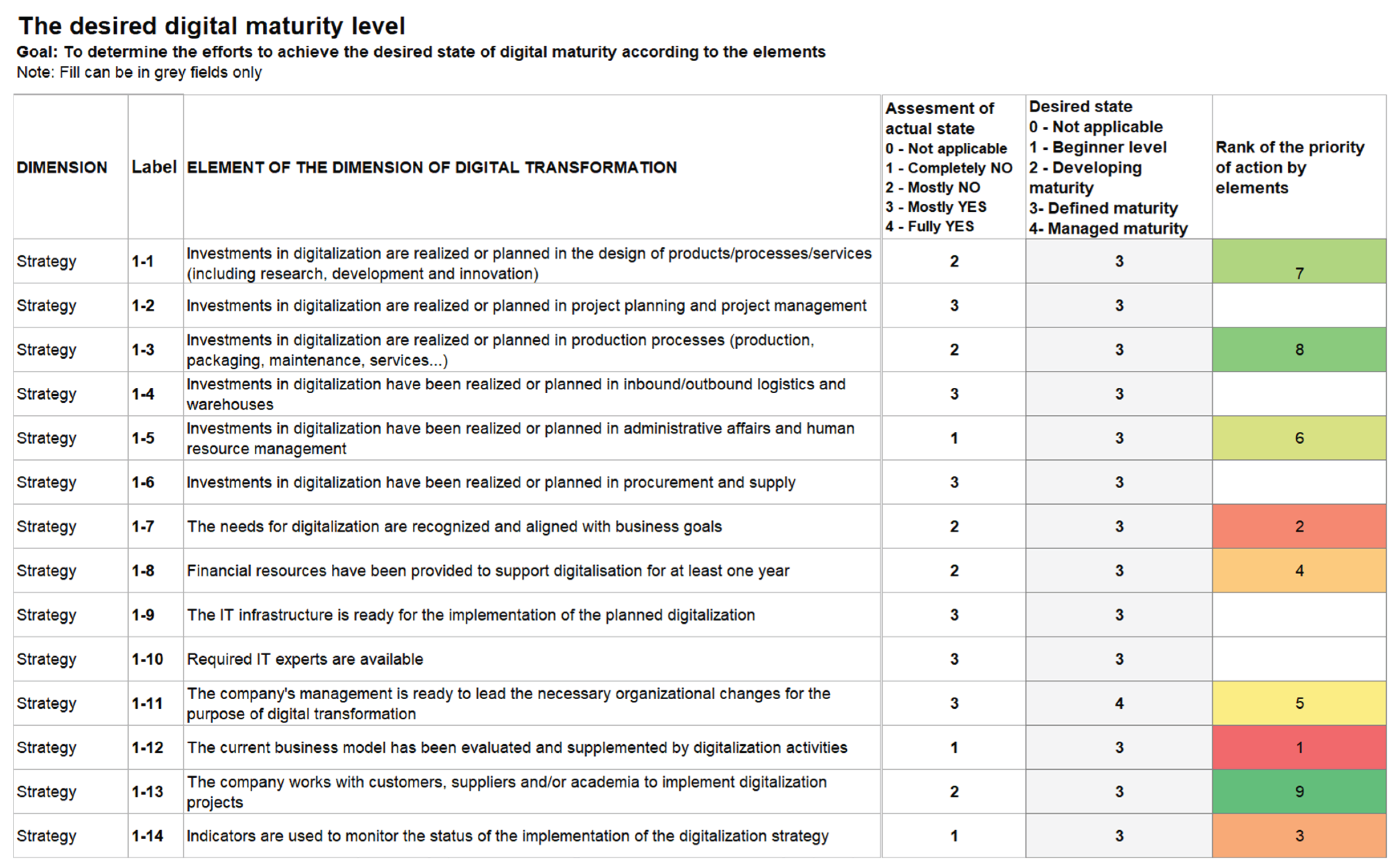

3.2. Definition of the Extended Maturity Assessment Model

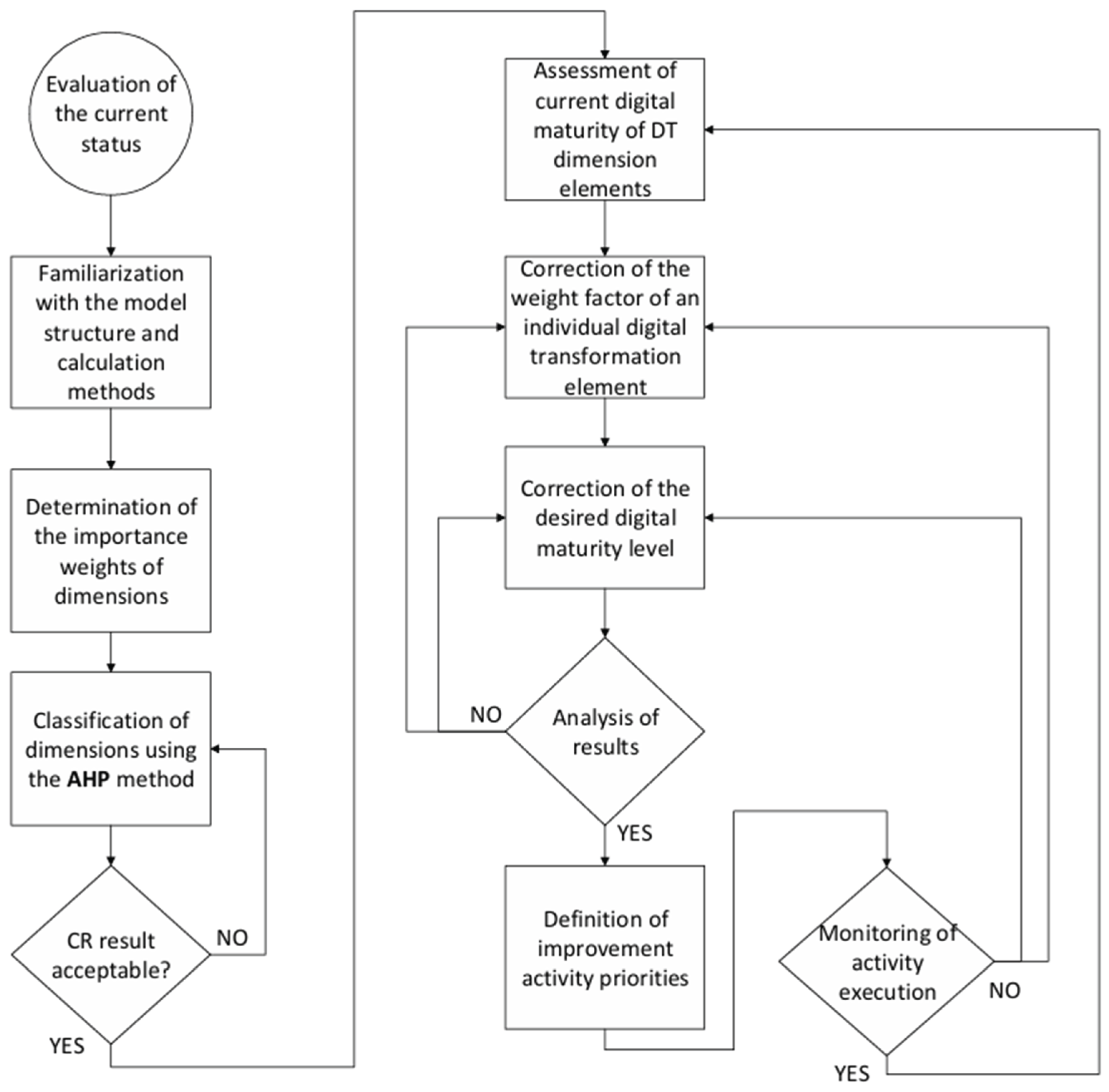

3.3. Workflow for the Application of the DAMA-AHP Model

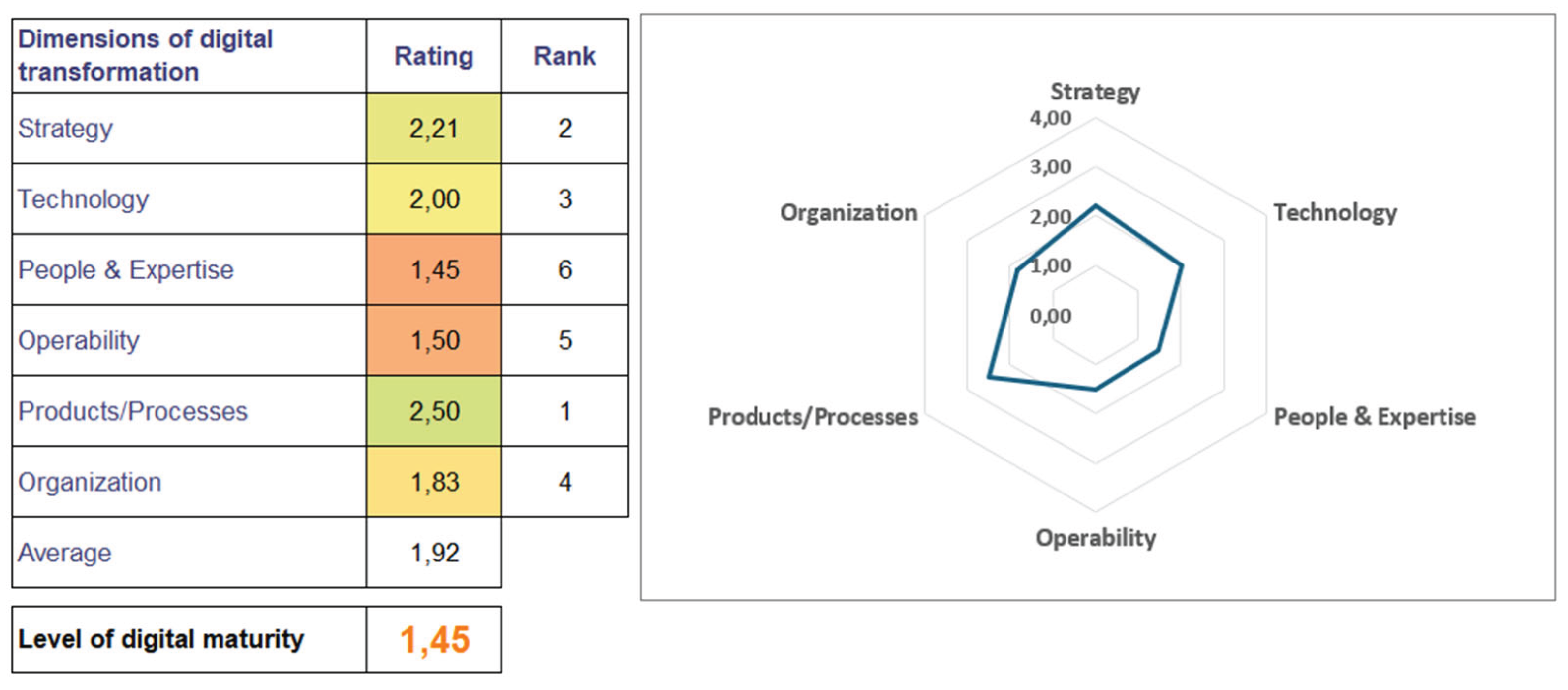

4. Model validation through Case Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kraus, S.; Jones, P.; Kailer, N.; Weinmann, A.; Chaparro-Banegas, N.; Roig-Tierno, N. Digital Transformation: An Overview of the Current State of the Art of Research. Sage Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Weyerer, J.C.; Heckeroth, J.K. Digital Disruption and Digital Transformation: A Strategic Integrative Framework. International Journal of Innovation Management 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åström, J.; Reim, W.; Parida, V. Value Creation and Value Capture for AI Business Model Innovation: A Three-Phase Process Framework. Review of Managerial Science 2022, 16, 2111–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesböck, F. Options for Formulating a Digital Transformation Strategy. MIS Quarterly Executive 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.E.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Sadreddin, A. Digitally-Enabled University Incubation Processes. Technovation 2022, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance? (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Di Bella, L..; Katsinis, A..; Lagüera-González, J..; Odenthal, L..; Hell, M..; Lozar, B.. Annual Report on European SMEs 2022/2023 : SME Performance Review 2022/2023; Publications Office of the European Union, 2023; ISBN 9789268061749.

- Nimac, P.; Boroš, S.; Bašadur, A. Structural Business Indicators of Enterprises, 2020; Zagreb, 2022;

- Meyendorf, N.; Ida, N.; Singh, R.; Vrana, J. Handbook of Nondestructive Evaluation 4.0. In; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2021; pp. 107–125 ISBN 978-3-30-73205-9.

- Lang, V. Digitalization and Digital Transformation. In: Digital Fluency. In Digital Fluency; APress Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature, 2021; pp. 1–50.

- Reis, J.; Amorim, M.; Melão, N.; Cohen, Y.; Rodrigues, M. Digitalization: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. In Proceedings of the Proceedings on 25th International Joint Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management – IJCIEOM. IJCIEOM 2019. Lecture Notes on Multidisciplinary Industrial Engineering; Springer, 2020.

- Schumacher, A.; Erol, S.; Sihn, W. A Maturity Model for Assessing Industry 4.0 Readiness and Maturity of Manufacturing Enterprises. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Vol. 52, pp. 161–166.

- Wen, H.; Zhong, Q. ; Chien-Chiang Digitalization, Competition Strategy and Corporate Innovation: Evidence from Chinese Manufacturing Listed Companies. International Review of Financial Analysis 2022, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Saunila, M.; Ukko, J. Digital Orientation, Digital Maturity, and Digital Intensity: Determinants of Financial Success in Digital Transformation Settings. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 2022, 42, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Rahman, M. Competing in the Age of Omnichannel Retailing. MIT Sloan Manag Rev 2013, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Benlian, A.; Kettinger, W.J.; Sunyaev, A.; Winkler, T.J. Special Section: The Transformative Value of Cloud Computing: A Decoupling, Platformization, and Recombination Theoretical Framework. Journal of Management Information Systems 2018, 35, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Gonçalves, H.M.; Teles, M. Social Media Engagement and Real-Time Marketing: Using Net-Effects and Set-Theoretic Approaches to Understand Audience and Content-Related Effects. Psychol Mark 2023, 40, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Fast-Berglund, Å.; Paulin, D. Current and Future Industry 4.0 Capabilities for Information and Knowledge Sharing: Case of Two Swedish SMEs. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 105, 3951–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodapp, D.; Hanelt, A. Interoperability in the Era of Digital Innovation: An Information Systems Research Agenda. Journal of Information Technology 2022, 37, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Qi Dong, J.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital Transformation: A Multidisciplinary Reflection and Research Agenda. J Bus Res 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grufman, N.; Lyons, S. Exploring Industry 4.0 A Readiness Assessment for SMEs, Stockholm Umiversity, 2020.

- Schoemaker, P.J.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, Dynamic Capabilities, and Leadership. Calif Manage Rev 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. Leading Digital: Turning Technology into Business Transformation; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, 2014; Vol. 61; ISBN 978-1-62527-247-8.

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The Digital Transformation of Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Progress, Challenges and Key Themes. Res Policy 2019, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Antunes Marante, C. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change. Journal of Management Studies 2021, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, S.; Reis, J.L.; Pereira, R.H. Digital Maturity Model for Industries SMEs: A Systematic Digital Maturity Model for Industries SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the CAPSI 2024 Proceedings Portugal (CAPSI); AIS Electronic Library (AISeL), 2024; pp. 41–55.

- European Commision Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2021 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Telecommunication Union, I. Measuring Digital Development - Facts and Figures 2021; 2021; ISBN 9789261354015.

- Dell Technologies Digital Transformation Index 2020 Executive Summary; 2020.

- Georgescu, I.; Kinnunen, J. The Digital Effectiveness on Economic Inequality: A Computational Approach. In Proceedings of the Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics ((SPBE)); Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham., 2021.

- Chanias, S.; Hess, T. How Digital Are We? Maturity Models for the Assessment of a Company’s Status in the Digital Transformation. Management report 2016, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D.; de Pablo, S. Digital Maturity Model. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/digital-maturity (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- EBD Core Development Team The Smart Industry Readiness Index Catalysing the Transformation of Manufacturing The Smart Industry Readiness Framework The LEAD Framework Available online: www.edb.gov.sg.

- Gill, M.; Vanboskirk, S. The Digital Maturity Model 4.0 Benchmarks: Digital Business Transformation Playbook. Available online: http://forrester.nitro-digital.com/pdf/Forrester-s%20Digital%20Maturity%20Model%204.0.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Geissbauer, R.; Vedso, J.; Schrauf, S. 2016 Global Industry 4.0 Survey: Industry 4.0: Building the Digital Enterprise. Available online: www.pwc.com/industry40.

- Schumacher, A.; Erol, S.; Sihn, W. A Maturity Model for Assessing Industry 4.0 Readiness and Maturity of Manufacturing Enterprises. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Vol. 52, pp. 161–166.

- Schuh, G.; Anderl, R.; Dumitrescu, R.; Krüger, A.; Ten Hompel, M. Using the Industrie 4.0 Maturity Index in Industry. Available online: https://en.acatech.de/publication/using-the-industrie-4-0-maturity-index-in-industry-case-studies/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Strategy, Not Technology, Drives Digital Transformation Available online:. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/strategy-not-technology-drives-digital-transformation (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Fitzgerald, M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing Digital Technology, A New Strategic Imperative. Available online: http://sloanreview.mit.edu/faq/.

- Valdez-De-Leon, O. A Digital Maturity Model for Telecommunications Service Providers. Available online: www.timreview.ca.

- Ochoa-Urrego, RL.; Peña-Reyes, JI. Digital Maturity Models: A Systematic Literature Review. In Digitalization; Schallmo, D.R.A., Tidd, J., Eds.; Springer, Cham, 2021; pp. 71–85.

- Rossmann, A. Rossmann, A. Digital Maturity: Conceptualization and Measurement Model. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Information Systems; ICIS 2018: San Francisco, 2019.

- De Carolis, A.; Macchi, M.; Negri, E.; Terzi, S. A Maturity Model for Assessing the Digital Readiness of Manufacturing Companies. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer New York LLC, 2017; Vol. 513, pp. 13–20.

- Haryanti, T.; Rakhmawati, N.A.; Subriadi, A.P. The Extended Digital Maturity Model. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordsen, T.; Bick, M. A Decade of Digital Maturity Models: Much Ado about Nothing? Information Systems and e-Business Management 2023, 21, 947–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruljac, Ž. Modeli Digitalne Zrelosti Poduzeća-Objašnjenje, Pregled Literature i Analiza. Obrazovanje za poduzetništvo-E4E: znanstveno stručni časopis o obrazovanju za poduzetništvo 2019, 9, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, T.; Health, Q.; Rosemann, M. Understanding the Main Phases of Developing a Maturity Assessment Model. Available online: http://www.efqm.org/Default.

- Axmann, B.; Harmoko, H. Industry 4.0 Readiness Assessment. Tehnički glasnik 2020, 14, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizam-Hanafiah, M.; Soomro, M.A.; Abdullah, N.L. Industry 4.0 Readiness Models: A Systematic Literature Review of Model Dimensions. Information (Switzerland) 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, E.; Martinez, V. Digital Transformation Capability Maturity Model Enabling the Assessment of Industrial Manufacturers. Comput Ind 2021, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhusseiny, H.M.; Crispim, J. A Review of Industry 4.0 Maturity Models: Adoption of SMEs in the Manufacturing and Logistics Sectors. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier B.V., 2023; Vol. 219, pp. 236–243.

- Spaltini, M.; Acerbi, F.; Pinzone, M.; Gusmeroli, S.; Taisch, M. Defining the Roadmap towards Industry 4.0: The 6Ps Maturity Model for Manufacturing SMEs. In Proceedings of the Procedia CIRP; Elsevier B.V., 2022; Vol. 105, pp. 631–636.

- Omol, E.J.; Mburu, L.W.; Abuonji, P.A. Digital Maturity Assessment Model (DMAM): Assimilation of Design Science Research (DSR) and Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI). Digital Transformation and Society 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubis, A.A. Digital Maturity Assessment Model for the Organizational and Process Dimensions. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalender, Z.T.; Žilka, M. A Comparative Analysis of Digital Maturity Models to Determine Future Steps in the Way of Digital Transformation. In Proceedings of the Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier B.V., 2024; Vol. 232, pp. 903–912.

- Ustundag, A.; Cevikcan, E. Industry 4.0: Managing The Digital Transformation; Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-57869-9.

- Krulčić, E.; Doboviček, S.; Pavletić, D.; Čabrijan, I. A MCDA Based Model for Assessing Digital Maturity in Manufacturing SMEs. TEHNIČKI GLASNIK 2025, 19, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Martinčević, N.Ć.; Salihić, A.; Novoselec, S.M.; Parić, A.; Jakopović, F.; Galijan, V.; Sandalić, D.; Nahić, E.; Perić, M.; Mikulaš, D.; et al. Digitalna Transformacija u Hrvatskoj. Available online: www.apsolon.com.

- Mladineo, M.; Celent, L.; Milković, V.; Veža, I. Current State Analysis of Croatian Manufacturing Industry with Regard to Industry 4.0/5.0. Machines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palčić, I.; Buchmeister, B.; Ojsteršek, R.; Kovič, K. Manufacturing Company Industry 4.0 Readiness: Case from Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia.; Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, April 13 2022; pp. 25–34.

- Palcic, I.; Ojstersek, R.; Buchmeister, B.; Kovic, K. Industry 4.0 Readiness of Slovenian Manufacturing Companies. In Proceedings of the DAAAM International Scientific Book; 2022; pp. 001–016.

- Trstenjak, M.; Opetuk, T.; Pavković, D.; Zorc, D. Industry 4.0 in Croatia– Perspective and Industrial Familiarity with the (New) Digital Concept. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 5th International Conference on the Industry 4.0 Model for Advanced Manufacturing; Wang, L., Majstorovic, V.D., Mourtzis, D., Carpanzano, E., Moroni, G., Galantucci, L.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020.

- Bajrić, H.; Vučijak, B.; Kadrić, E.; Anđelić, A. Benchmarking of Bosnia and Herzegovina to Croatia Manufacturing Industry and Industry 4.0. TEM Journal 2021, 10, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrić, T.; Cosic, M. Challenges of The Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Case Study of Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Journal of Sales Retailing and Marketing 2021, 10, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rakic, S.; Pavlovic, M.; Marjanovic, U. A Precondition of Sustainability: Industry 4.0 Readiness. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joković, J. Primena Koncepta Industrija 4.0 u Republici Srbiji. Zbornik radova Fakulteta tehničkih nauka u Novom Sadu 2020, 35, 1782–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, A.; Büyüközkan, G. Digital Transformation Journey Guidance: A Holistic Digital Maturity Model Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Systems 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtblau, K.; Stich, V.; Bertenrath, R.; Blum, M.; Bleider, M.; Millack, A.; Schmitt, K.; Schmitz, E.; Schröter, M. Industrie 4.0 Readiness. Available online: https://industrie40.vdma.org/documents/4214230/26342484/Industrie_40_Readiness_Study_1529498007918.pdf/0b5fd521-9ee2-2de0-f377-93bdd01ed1c8 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Saaty, T., L. The Analitic Hierarchy Process. New York McGraw-Hill 1980, 324. [Google Scholar]

- Krulčić, E.; Pavletić, D.; Doboviček, S.; Žic, S. Multi-Criteria Model for the Selection of New Process Equipment in Casting Manufacturing: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Tehnicki Glasnik; University North, May 8 2022; Vol. 16, pp. 170–177.

| Ranking of measures by element | Element of the digital transformation dimension | Dimension | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The current business model was evaluated and supplemented by digitalization activities | Strategy | 1-12 |

| 2 | The need for digitalization was determined and aligned with the company's goals | Strategy | 1-7 |

| 3 | Indicators are used to monitor the implementation status of the digitalization strategy | Strategy | 1-14 |

| 4 | Funding has been made available to support digitization for at least one year | Strategy | 1-8 |

| 5 | The company's management is prepared to make the necessary organizational changes for the purpose of digitalization, the management is prepared to make the necessary organizational changes for the purpose of DT | Strategy | 1-11 |

| 6 | Investments in digitalization have been made or are planned in administration and human resources | Strategy | 1-5 |

| 7 | Technologies for big data analysis and decision support systems are used | Technology | 2-15 |

| 8 | Investments in digitalization have been made or are planned in the design of products/processes/services (including research, development and innovation) | Strategy | 1-1 |

| 9 | Investments in digitalization are made or planned in production processes (production, packaging, maintenance, services ...) | Strategy | 1-3 |

| 10 | The company works with customers, suppliers and/or academia to implement digitalization projects | Strategy | 1-13 |

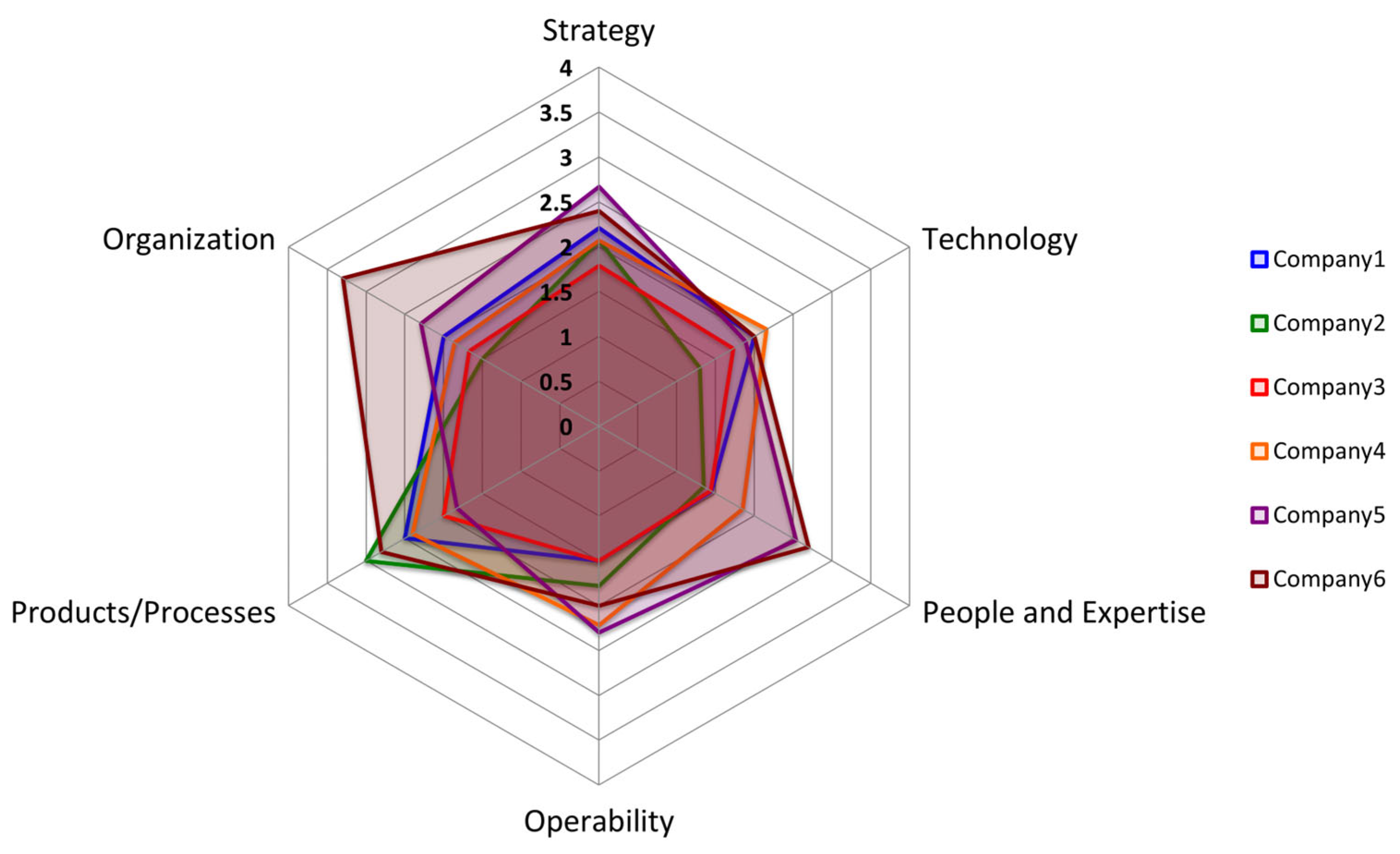

| Maturity dimensions | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | Avg | Std | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | 2.21 | 2.07 | 1.79 | 2.07 | 2.67 | 2.40 | 2.20 | 0.30 | 0.88 |

| Technology | 2.00 | 1.30 | 1.73 | 2.16 | 1.89 | 2.00 | 1.85 | 0.30 | 0.86 |

| People and Expertise | 1.45 | 1.35 | 1.44 | 1.85 | 2.54 | 2.70 | 1.89 | 0.59 | 1.35 |

| Operability | 1.50 | 1.78 | 1.50 | 2.22 | 2.30 | 2.00 | 1.88 | 0.35 | 0.80 |

| Products / Processes | 2.50 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.40 | 1.83 | 2.80 | 2.42 | 0.45 | 1.17 |

| Organization | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.67 | 1.86 | 2.29 | 3.30 | 2.10 | 0.65 | 1.80 |

| Std | 0.37 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.40 |

| Average value | 1.94 | 1.83 | 1.69 | 2.09 | 2.25 | 2.55 | 2.06 | 0.31 | 0.86 |

| Level of digital maturity | 1.45 | 1.30 | 1.44 | 1.85 | 1.83 | 2.00 | 1.65 | 0.28 | 0.70 |

| Cx-companies; Avg-average; Std-standard deviation; R-ratio | |||||||||

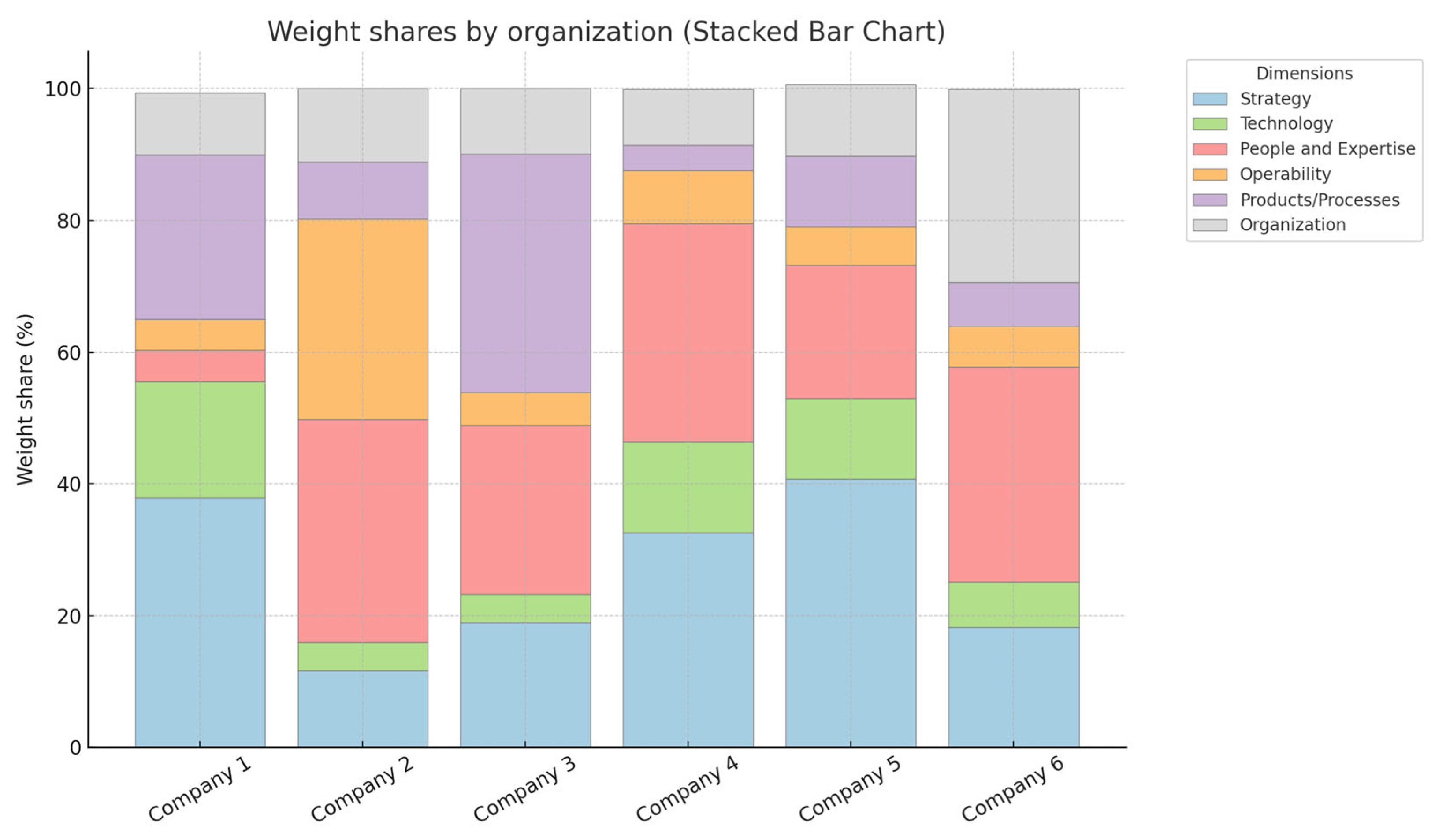

| Maturity dimensions | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | Avg | Std | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | 37.90 | 11.62 | 18.95 | 32.60 | 40.70 | 18.20 | 26.66 | 11.97 | 29.08 |

| Technology | 17.65 | 4.32 | 4.35 | 13.80 | 12.30 | 6.90 | 9.89 | 5.51 | 13.33 |

| People and Expertise | 4.80 | 33.84 | 25.54 | 33.10 | 20.20 | 32.70 | 25.03 | 11.26 | 29.04 |

| Operability | 4.65 | 30.45 | 5.06 | 8.10 | 5.90 | 6.20 | 10.06 | 10.06 | 25.80 |

| Products / Processes | 25.00 | 8.68 | 36.18 | 3.80 | 10.70 | 6.60 | 15.16 | 12.67 | 32.38 |

| Organization | 9.43 | 11.09 | 9.91 | 8.50 | 10.90 | 29.30 | 13.19 | 7.95 | 20.80 |

| Cx-companies; Avg-average; Std-standard deviation; R-ratio | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).