1. Introduction

Nucleic acids, beyond their role as carriers of genetic information, have emerged as versatile therapeutic agents capable of regulating gene expression. Among these, RNA-cleaving DNAzymes are synthetic single-stranded DNA molecules that catalyse site-specific RNA cleavage, offering advantages such as chemical stability, low production cost, and modular design. DNAzymes like 10-23 and 8-17, discovered through in vitro selection, have been widely studied for their ability to downregulate specific mRNA targets in disease contexts including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and viral infections [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The BCL-2 protein family plays a pivotal role in regulating apoptosis, particularly by controlling mitochondrial membrane integrity and cytochrome c release [

5]. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic members such as BCL-2 is a hallmark of various cancers and is associated with treatment resistance [

6,

7,

8]. Although small molecule inhibitors like venetoclax [

9,

10] have been approved for BCL-2 inhibition, alternative approaches such as nucleic acid-based gene silencing offer higher specificity and tunability.

In this study, we developed a novel in vitro selection approach for evolving RNA-cleaving DNAzymes that target natural, unmodified BCL-2 mRNA. Unlike traditional strategies that employ covalently tethered RNA-DNA chimeras, our method uses Watson-Crick base pairing to allow natural hybridization between a randomized DNA library and BCL-2 mRNA immobilized on magnetic beads. This design favors the selection of trans-acting DNAzymes that mimic physiological mRNA-DNA interactions. We report two potent DNAzymes, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a, which downregulate BCL-2 expression in cancer cell lines and suppress tumor growth in a murine cancer model, thus providing a foundation for future DNAzyme-based cancer therapeutics.

2. Materials and Methods.

2.1. In Vitro Selection of Trans-Acting mRNA Deoxy Ribozymes

50 bases of 5′-Biotin tagged

BCL-

2 mRNA (500nM) (IDT, USA) was immobilized on 50µl of M-280 Streptavidin magnetic Dynabeads (Invitrogen). 1µM of ssDNA (IDT, USA) library was preheated at 95ºC for 5 minutes followed by flash chilling in ice and was added to the

BCL-

2 mRNA immobilized on Streptavidin magnetic beads [

11]. ssDNA library was incubated with immobilized mRNA for 20 min at room temperature after which unbound library molecules were removed by wash buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 1mM EDTA pH8.0, 2M NaCl). RNA cleavage reaction was performed in the buffer

(150mM KCl, 2mM MgCl

2) was added to the DNA-RNA hybrid and the reaction was further incubated for 6 h [

12]. The active DNAzyme pool was collected in the flow-through fraction and enriched by PCR using DreamTaq PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) with forward primer: 5′-GGCTGGATGGGGCGTGT-3′ and 5′ Spacer-C18 tagged reverse primer: 5′-CGCTGTCCGCACCGTG-3′ (IDT, USA). PCR was performed for 20 cycles (initial denaturation at 95ºC, 5min and cycling at 94ºC, 30s; 55ºC, 30s and 72ºC, 30s). The amplified dsDNA DNAzyme pool was separated on denaturing 12% TBE Urea-PAGE [

13]. The ssDNA band was excised from the gel and purified using the ‘crush and soak’ method [

14]. This selected DNAzyme pool was used for the next round of selection. The in vitro selection procedure was carried out for 10 iterative rounds. Incubation time for DNAzyme-mediated RNA cleavage was gradually reduced to 3h in the last round. After a tenth round of in vitro selection, the selected DNAzyme pool was PCR amplified and the amplified dsDNA PCR fragments were cloned in a TA-Cloning vector (Pure Gene) [

15]. Individual DNAzyme clones were sequenced at the 1st Base sequencing facility (Axil Scientific, Singapore).

2.2. Cell Culture and Transfection

HepG-2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma), and MCF-7 (human breast carcinoma) cell lines were purchased from the National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS, Pune, India) and mouse 4T1 (mammary carcinoma) cell line was purchased from ATCC (American Type Cell Culture, USA). HepG2 and MCF-7 were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) while 4T1 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media at 37ºC with 5% CO

2 and supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco), 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (100 units/mL of Penicillin and 100 mg/mL of Streptomycin) (Gibco) and 0.25μg/ml Amphotericin B (Gibco). Cells were harvested at ~60% confluency for transfection. All transfection experiments were performed in reduced serum media (Opti-MEM

® I, Invitrogen) with 200nM of DNAzymes(s) using Oligofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [

16,

17].

2.3. Quantitative Real Time-PCR

Cells were seeded at a density of 3 x 10

5 cells/well in 6-well culture plates in a growth medium without antibiotics one day before the experiment. Transfection with DNAzymes was performed as mentioned above. Total RNA from cells and tissues was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) reagent [

18,

19,

20] For all the qPCR experiments, 1μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using a Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Real time-PCR was performed on CFX Connect

™ Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) in a 96-well plate using a program, 95ºC 5min pre-denaturation and cycling at 94ºC, 10s denaturation, 55ºC, 5s annealing and 72ºC, 10s amplification. PCR was run for 40 cycles and all the samples were run in triplicates.

18s RNA was used to normalize

BCL-2 expression and relative fold expression values were calculated using ∆∆C

t method [

21]. Primers used for qPCR analysis are given in

Table S1.

2.4. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

For cell viability assay, 1000 cells were seeded in a 96-well culture plate one day before the experiment. After DNAzymes transfection (200nM in triplicates), 0.5mg/ml of 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) solution (Sigma) was added at time points 12, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h. Cells were incubated for 3 h at 37ºC followed by which, the supernatant was removed and 200μl of DMSO was added to dissolve formazan crystals. After 10 min, absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax

®, Molecular Devices

) [

22,

23].

2.5. Apoptotic Cell Imaging Using Confocal Microscopy

HepG2 cells (4 X 10

4) were seeded on poly-L-lysine-coated chamber slides one day before transfection. 24 h after DNAzyme transfection (200nM), cells were washed with cold 1X PBS followed by the addition of 5μl of FITC-Annexin V solution (Molecular Probes) and 100μg/ml of Propidium Iodide solution (Molecular Probes) to each chamber. Cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature after which cells were washed once with 1X Annexin binding buffer (Molecular Probes). Apoptotic/dead and live cells were imaged by Leica Microsystems confocal microscope (TCS SP8) [

24,

25].

2.6. Animal Models and Tumor Implantation

Female BALB/C mice of weight approximately 15 to 20gm were purchased from the NIN- Hyderabad with prior approval from the animal ethical committee (Regno.1996/po/s/17/CPCSEA). The animals were quarantined and acclimatized sheltered in vivo animal cages with proper temperature, light, feed, and water. Once the average weights of the animals reached 20 to 25gms the animals were divided into four groups (six animals per group). A 4T1 syngeneic Breast cancer model was developed by injecting the pre-cultured 4T1 –cells of the number 3x10

5 cells in PBS per each animal injected carefully in the 6th breast pad with 1m of the insulin syringe [

26,

27]. Tumours were visible after the 10 days of the injection 3DTumour volumes were measured and the average tumour volume of each group was recorded before and after the treatment of the DNAzymes (DNZ-15, DNZ-35A) respectively 12 animals were finally included in the present study (n=3 per group). Mice inclusion criteria were uniform tumor volume ten days post-implantation which excluded the remaining 14 animals from the study. All the animal experiments were performed based on the Institution animal ethical committee guidelines.

2.7. In Vivo DNAzymes Studies

Experimental DNAzymes suspension was made in deionized water and injected at the tumor site at a concentration of 10μg/animal. One group was injected with the 5-Flurouracil (5FU) at a concentration of 5mg/kg body weight. Control animals were injected with sterile double distilled water only. DNAzymes were administered on the 10th and 20th day after tumor induction. Animals were divided into four groups (n=3: DNZ15, DNZ35a, 5-Fluorouracil, and Control group) and tumor volumes were measured on Day 0 (treatment initiated), Day 10 and Day 21 post-treatment. After 21 days, tumors were carefully excised and washed with 1XPBS and dried on paper towels and tumor weight and volumes were measured.

2.8. In Vivo Tumor Imaging

For live-in vivo tumor imaging, mice were anaesthetized with Isoflurane in the anaesthetic chamber (Vevo LAB, Visual sonics). Animals were placed on the imaging pad with a constant circulation of 2% Isoflurane throughout the imaging process [

28,

29] Tumor were scanned using B (Bright) and CD (Color Doppler) modes and videos were captured. Vital parameters, respiration rate, and cardio functions were monitored throughout the imaging. The acquired data were analysed using Vevo LAB 3.1.1 software.

2.9. Immunohistochemistry

Tumor tissues were sliced at a diameter of 5μm with histotome. Tissue sections were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were incubated with Anti- BCL-2 primary antibody (Merck) overnight at 40C followed by incubation with HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Merck) for 2h at room temperature. BCL-2 expression was detected by adding a TMB substrate and slides were imaged in the microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

2.10. Western Blotting

Total protein was extracted from tissues and cells and was resuspended in RIPA buffer. 40μg/lane protein lysates were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) [

30]. The membranes were blocked in 3% BSA for 2h at room temperature and incubated at 4°C overnight with anti-

BCL-2 (Cell Signaling) antibody at 1: 1000 dilution. Anti-β-Actin (1:1000) (Cell Signaling) was used as an internal control. HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000) (Cell Signaling) was added at room temperature for 2h. ECL substrate (Clarity Max™, Bio-Rad) was added, and bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (Fusion FX, Vilber Lourmat, France).

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All graphs were constructed using GraphPad PRISM 8.0. Comparisons of DNAzyme transfected or treated groups were done with controls using the student t-test. The P-value of <0.05 was statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Selection of BCL-2 mRNA-Cleaving DNAzymes

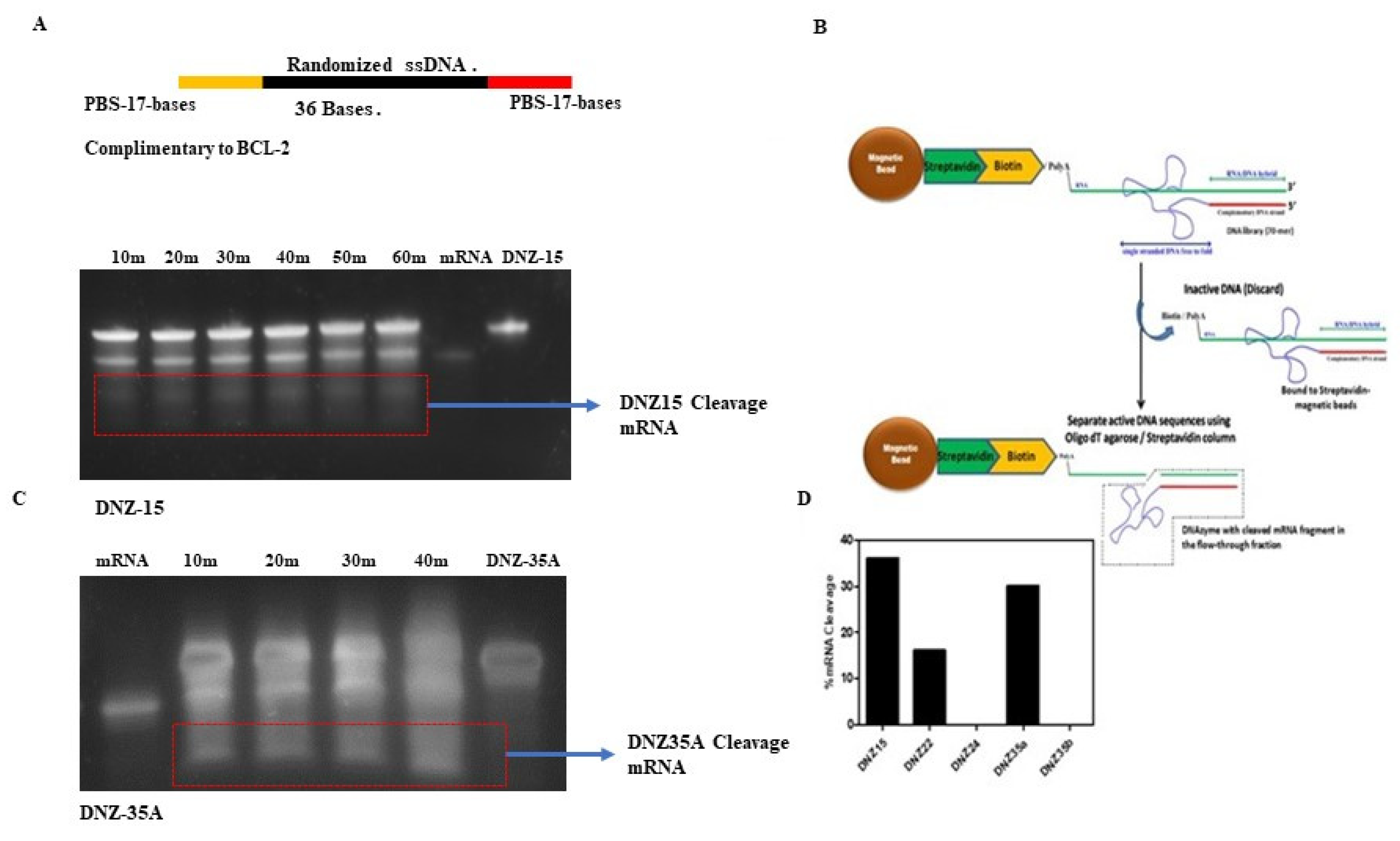

To develop DNAzymes targeting BCL-2 mRNA, we employed a novel trans-acting in vitro selection strategy designed to enrich for catalytically active DNAzymes under near-physiological conditions. This approach utilized a 70-mer single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) library, containing a central 36-nucleotide randomized region flanked by 17-nucleotide primer binding sites (

Figure 1A). The target substrate for selection was a 50-nucleotide biotinylated RNA fragment derived from the 5′ end of human BCL-2 mRNA and identical to the mouse BCL-2 mRNA, which was immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to enable selective partitioning of active DNAzymes from the inactive pool (

Figure 1B).

Unlike traditional cis-acting selection strategies, where the RNA and DNA are covalently linked, our trans-acting design allows for free interaction between the DNAzyme and RNA—more closely mimicking physiological interactions. Through ten iterative rounds of selection, washing, and amplification, we enriched a pool of ssDNA molecules with increasing catalytic activity.

After the final round, the DNAzyme pool was cloned and sequenced, resulting in the identification of five distinct DNAzyme candidates: DNZ-15, DNZ-22, DNZ-24, DNZ-35a, and DNZ-35b. These were synthesized and screened individually for trans-cleaving activity against the BCL-2 RNA substrate under in vitro conditions using denaturing PAGE analysis. Time-course assays revealed that among the tested molecules, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a demonstrated the most efficient catalytic activity, cleaving approximately 35% and 30% of the substrate RNA, respectively, within 80 minutes of incubation (

Figure 1C,D).

3.2. DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a Downregulate BCL-2 Expression in Cancer Cell Lines

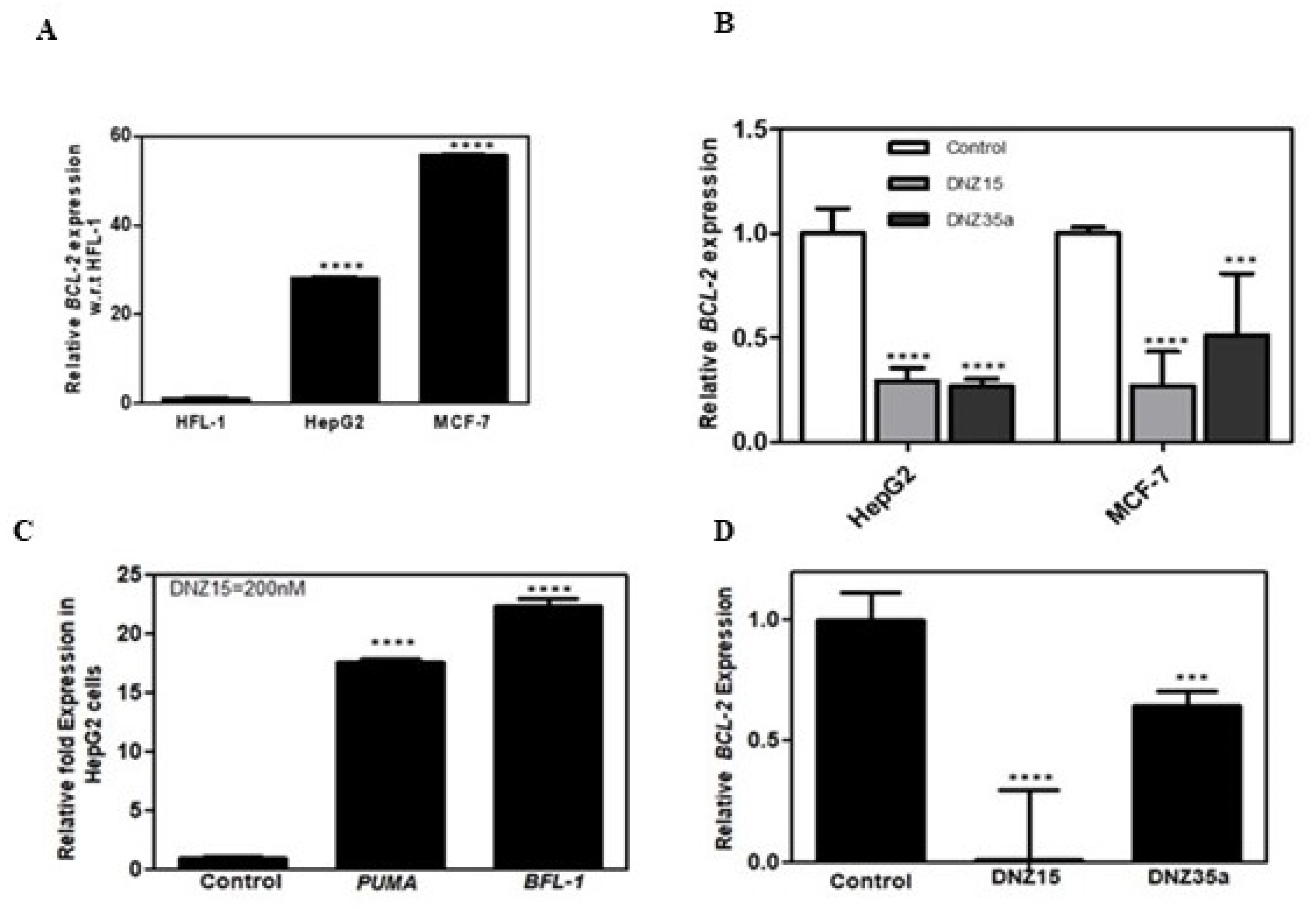

To assess the functional activity of our evolved DNAzymes in a cellular context, we evaluated the expression of BCL-2 mRNA in multiple cancer cell lines following DNAzyme treatment. Baseline expression analysis by quantitative RT-PCR revealed that BCL-2 mRNA is significantly overexpressed in MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma) and HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells relative to HFL-1 (normal human lung fibroblasts), indicating these cell lines are suitable models for investigating BCL-2-targeted gene knockdown (

Figure 2A).

Transfection of MCF-7 and HepG2 cells with DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a at a concentration of 200 nM resulted in a robust and statistically significant reduction in BCL-2 mRNA levels compared to mock-transfected controls (

Figure 2B). The degree of downregulation observed across both cancer lines underscores the catalytic efficiency and cross-cell-type applicability of the DNAzymes.

To further explore the downstream effects of BCL-2 silencing, we assessed the expression of key pro-apoptotic markers regulated by mitochondrial apoptotic signaling. Notably, in HepG2 cells, DNZ-15 treatment induced upregulation of PUMA (p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) and BFL-1 (BCL-2 related protein A1)—both of which are antagonists of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins [

31,

32,

33,

34] (

Figure 2C). These findings suggest that the decrease in BCL-2 expression translates into functional activation of apoptosis-related pathways.

In addition to human cancer cells, we extended our analysis to the murine 4T1 mammary carcinoma cell line, which was used in later in vivo studies. Upon transfection, both DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a suppressed BCL-2 mRNA expression in 4T1 cells (

Figure 2D). Together, these results demonstrate the consistent and effective knockdown of BCL-2 mRNA by DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a across multiple biologically relevant cancer cell lines, including human and murine models.

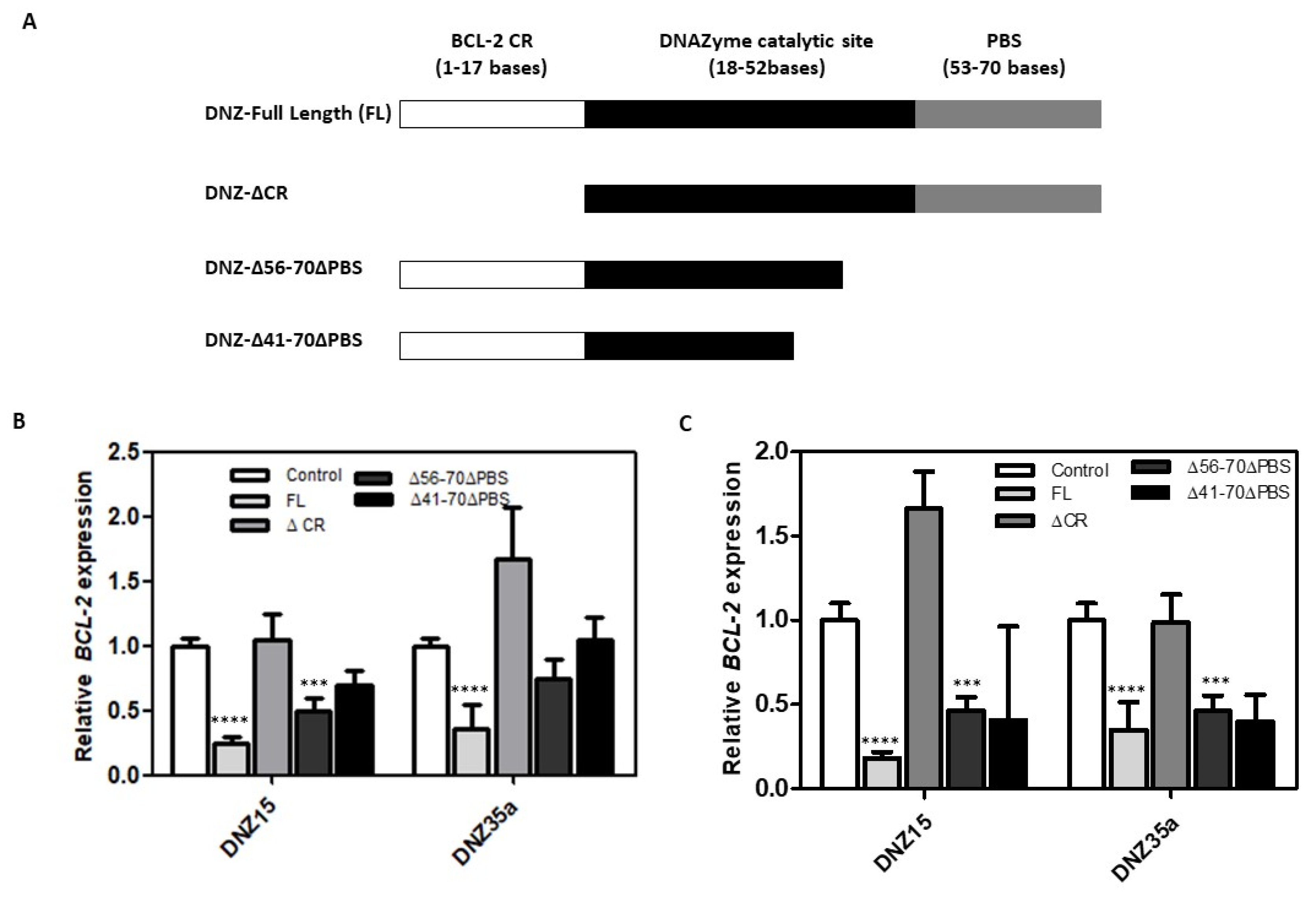

3.3. Both the Catalytic Domain and the Substrate Recognition Regions Are Needed for DNAzyme DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a Function

To better understand the structural basis for catalytic activity, we performed a detailed structure-function analysis of our lead DNAzymes, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a. Specifically, we evaluated whether truncations in either the mRNA-binding arms or the catalytic core would impact the ability of the DNAzymes to downregulate BCL-2 mRNA. Three constructs were created, 1) DNZ-ΔCR, in which 17 nucleotides from the BCL-2-complementary region were removed, effectively eliminating binding specificity, 2) DNZ-Δ56–70ΔPBS, which lacked the 3′ primer binding site and part of the structural scaffold supporting the catalytic domain and 3) DNZ-Δ41–70ΔPBS, in which a significant portion of the core catalytic domain was deleted. The functional activity of these truncated constructs was assessed in both HepG2 and MCF-7 cells by measuring BCL-2 mRNA expression levels post-transfection (

Figure 3B,C). As expected, the full-length (FL) DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a DNAzymes significantly reduced BCL-2 mRNA expression, validating their catalytic potency in cell-based assays.

In contrast, the DNZ-ΔCR variant, which lacked the BCL-2 complementary arm, showed no measurable downregulation of BCL-2 mRNA, confirming that target recognition through Watson-Crick base pairing is essential for function. The DNZ-Δ56–70ΔPBS construct, which retained the catalytic domain but lacked essential scaffold and primer regions, showed a moderate (~0.5-fold) reduction in BCL-2 mRNA, suggesting impaired structural integrity and reduced folding efficiency.

Most notably, the DNZ-Δ41–70ΔPBS variant—missing a significant portion of the catalytic core—exhibited only partial mRNA suppression, further reinforcing that both the catalytic domain and substrate recognition regions are indispensable for optimal activity.

These results provide strong evidence that our evolved DNAzymes function not as antisense oligonucleotides but as true nucleic acid enzymes, whose activity relies on precise secondary structure formation and proper alignment of catalytic residues. The observed differences in efficacy among the truncated variants highlight the importance of maintaining the full-length structural architecture to ensure correct folding and maximal RNA cleavage activity.

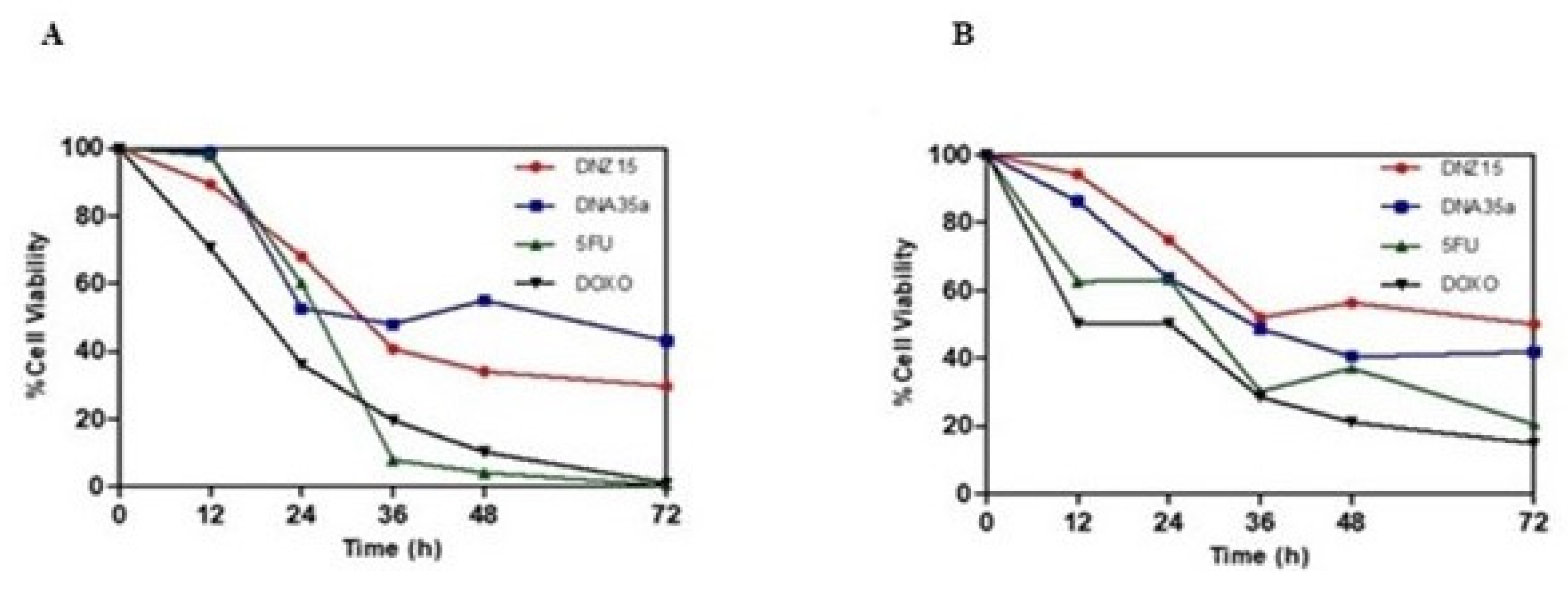

3.4. DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a Induce Apoptosis and Cell Death in Cancer Cells In Vitro

To determine whether the downregulation of BCL-2 by DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a translated into functional anti-cancer effects, we assessed cell viability and apoptosis induction in vitro. MTT cell viability assays were conducted in HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and MCF-7 (human breast cancer) cells treated with 200 nM of either DNAzyme. These experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated independently three times. The results revealed a significant, time-dependent reduction in cell viability in both cell lines over 72 hours of treatment (

Figure 4A,B).

In HepG2 cells, DNZ-15 induced the most pronounced cytotoxic response, cell death approximately 60% at 72 hours, while DNZ-35a caused about 50% cell death over the same time frame. In MCF-7 cells, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a induced 50% and 60% cell death respectively.

To further validate that the loss of viability was due to apoptotic cell death, we performed Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) staining in HepG2 cells, followed by imaging via confocal microscopy (

Figure 4D). Annexin V staining identified cells in early apoptosis (green fluorescence), while PI marked late apoptotic or necrotic cells (red fluorescence). In the merged images, DNAzyme-treated cells exhibited strong green and red staining patterns, confirming apoptosis induction as the primary mode of cell death. Control cells (mock-transfected) showed minimal staining, indicating low background apoptosis.

These results clearly demonstrate that DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a possess potent in vitro anti-cancer activity by actively inducing apoptosis in BCL-2-overexpressing tumor cells. The ability to trigger programmed cell death through BCL-2 silencing suggests that these DNAzymes function through a mechanism consistent with the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, restoring sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli by removing the anti-apoptotic blockade.

Importantly, this apoptotic response was consistent across two different cancer cell types—liver and breast cancer—further supporting the broad therapeutic applicability of our evolved DNAzymes. Taken together with the mRNA downregulation data, these results confirm that DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a are not only catalytically active in vitro but also biologically functional as therapeutic gene silencers, capable of suppressing tumor cell growth through apoptosis induction.

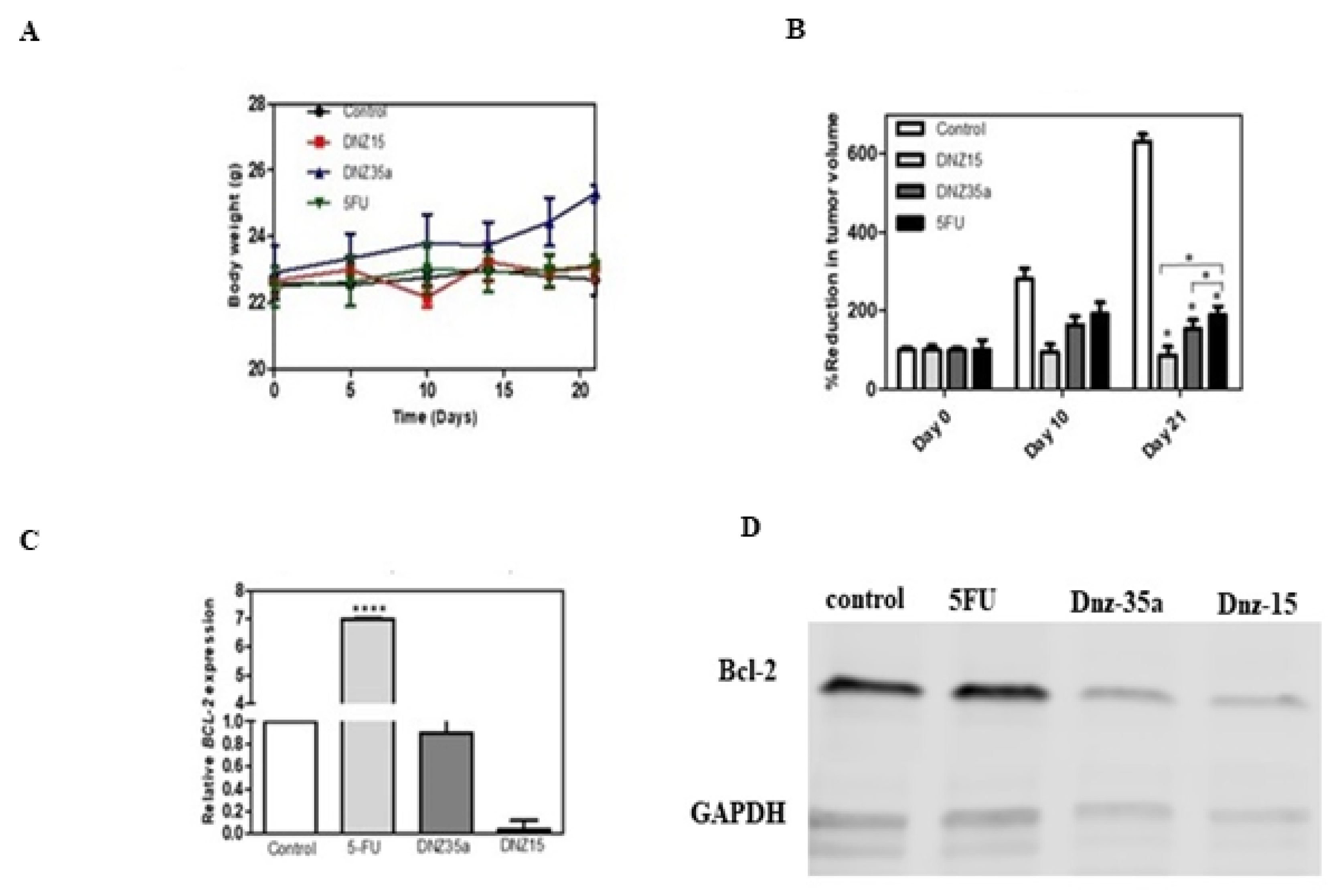

3.5. DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a Exhibit In Vivo Antitumor Efficacy

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of our evolved DNAzymes in a physiologically relevant setting, we tested DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a in a syngeneic orthotopic mouse model of breast cancer using 4T1 cells. The 4T1 model is widely recognized for its aggressive tumor growth and metastatic behaviour in immunocompetent BALB/c mice, making it a clinically relevant system for assessing both efficacy and immunological tolerance of new cancer therapeutics [

35,

36].

Ten days after tumor induction, when tumors reached a measurable and consistent volume, animals were divided into four groups and treated with DNZ-15, DNZ-35a, 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), or vehicle control. DNAzymes were administered locally at the tumor site on days 10 and 15 post-implantation. Tumor volume was monitored over 21 days to evaluate treatment effects (

Figure 5B).

Both DNAzymes significantly suppressed tumor growth compared to the control group, with DNZ-15 demonstrating the most potent antitumor activity. By day 21, the average tumor volume in DNZ-15 treated mice was reduced to below 100 mm³, compared to 600 mm³ in untreated controls. DNZ-35a also achieved substantial tumor suppression, maintaining tumor volume under 200 mm³, a result comparable to that of 5-FU-treated animals. These findings confirm that both DNAzymes are functionally active in vivo, and their antitumor efficacy is comparable to an established chemotherapeutic agent, highlighting their translational potential.

Importantly, throughout the treatment period, the body weight of the animals remained stable across all groups, indicating minimal systemic toxicity (

Figure 5A). Notably, the DNZ-35a group even showed a modest increase in body weight, further supporting the favourable safety profile of the DNAzyme treatment compared to conventional chemotherapy, which often results in weight loss due to toxicity.

To investigate whether tumor suppression was mediated by BCL-2 silencing, we performed molecular analysis on excised tumor tissues collected 21 days post-treatment. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed a significant reduction in BCL-2 mRNA levels in DNZ-15 treated tumors compared to control and 5-FU groups (p < 0.0001) (

Figure 5C). These results strongly suggest that the DNAzymes were able to access the tumor environment, enter cells, and effectively cleave the target BCL-2 mRNA in vivo.

Western blot analysis corroborated the transcriptional findings, demonstrating marked decreases in BCL-2 protein expression in tumors treated with DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a (

Figure 5D). Densitometric analysis normalized to β-actin confirmed the specificity of the suppression and further validated the post-transcriptional regulatory effect of the DNAzymes.

Additionally, immunohistochemical staining of tumor sections provided visual confirmation of reduced BCL-2 protein levels in the DNZ-treated groups (

Figure 5E). Fewer BCL-2-positive cells were observed in these tumors compared to control or 5-FU-treated tissues, aligning with the western blot data, and reinforcing the conclusion that the antitumor effects of DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a were mechanistically linked to BCL-2 knockdown.

Together, these data provide strong in vivo evidence that DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a induce tumor regression by specifically silencing BCL-2 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. The magnitude of tumor inhibition, combined with the favourable safety profile and mechanism-specific activity, positions these DNAzymes as promising candidates for further development as targeted nucleic acid therapeutics for cancer treatment.

4. Discussion

Our study presents a novel and effective strategy for the in vitro evolution and characterization of trans-acting RNA-cleaving DNAzymes specifically targeting the BCL-2 mRNA—a key anti-apoptotic gene that is overexpressed in many human cancers. Unlike traditional in vitro selection protocols that rely on covalent attachment of the RNA substrate to the DNAzyme library, we employed a more physiologically relevant trans-acting selection approach using a native, biotinylated 50-nucleotide fragment of BCL-2 mRNA. This design allowed us to select DNAzymes that bind and cleave their targets through natural base-pairing interactions, reflecting the intracellular environment more closely.

From this selection, two DNAzymes, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a emerged as potent candidates, displaying robust cleavage activity in vitro and significant BCL-2 knockdown liver carcinoma and breast cancer cells. The DNAzyme-mediated suppression of BCL-2 expression led to upregulation of pro-apoptotic markers PUMA and BFL-1 and a reduction in cell viability—demonstrating a direct functional consequence of gene silencing. Importantly, loss-of-function experiments using truncated variants confirmed that both the mRNA-complementary region and catalytic core are essential for DNAzyme activity, emphasizing the precision of these evolved molecules.

These results build upon a foundational body of work on RNA-cleaving DNAzymes, initially pioneered by Breaker and Joyce in 1994 [

37], and later refined by Santoro and Joyce with the introduction of the well-known 10-23 and 8-17 motifs [

38]. The therapeutic utility of DNAzymes has been explored in various disease contexts, including targeting VEGF in age-related macular degeneration [

39], c-Jun in skin cancer [

40], and BCL-2 in hematologic malignancies [

41]. However, despite encouraging preclinical data, few DNAzymes have progressed into advanced clinical development, often limited by delivery challenges and suboptimal in vivo stability.

Compared to prior studies targeting BCL-2, such as the 10-23 DNAzyme explored by Yang et al. [

42], which showed moderate mRNA suppression in leukemia models, our evolved DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a DNAzymes demonstrate improved catalytic efficiency (35% and 30% cleavage, respectively) under near-physiological conditions. Moreover, we extended the validation beyond cell lines to a syngeneic mouse model using 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells—an aggressive, immunocompetent model that more accurately reflects tumor-immune interactions. In vivo administration of DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a significantly suppressed tumor growth, with effects comparable to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), but potentially with fewer systemic side effects, as evidenced by stable body weight and absence of gross toxicity.

Molecular analysis of excised tumors confirmed the silencing of BCL-2 at both the mRNA and protein levels. These results highlight the potential of DNAzymes as viable alternatives to RNAi, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), or small-molecule inhibitors [

43,

44]. While siRNAs and ASOs can efficiently degrade target mRNAs via RNase H or RISC pathways, they often suffer from off-target effects, innate immune activation, and delivery barriers in vivo [

45,

46]. In contrast, DNAzymes—particularly those evolved for trans-acting activity—offer higher stability in serum, reduced immunogenicity, and a clear catalytic mechanism of action.

Importantly, our in vitro selection platform is modular and scalable. By simply modifying the complementary binding arms, it can be adapted to target virtually any mRNA sequence of interest. This provides a flexible tool not only for therapeutic development but also for functional genomics and gene validation in diverse biological systems. While further studies are warranted to optimize delivery—potentially using lipid nanoparticles, aptamer conjugation, or viral vectors—the current findings provide a compelling proof-of-concept for DNAzyme-based cancer therapeutics, particularly for genes like BCL-2, where dysregulation plays a central role in tumor survival and chemoresistance [

47,

48].

In the future, this approach may be extended to other members of the BCL-2 family, such as MCL-1 or BCL-XL, or to non-apoptotic gene targets in areas like viral replication, neurodegeneration, and inflammatory diseases [

49,

50]. The combination of trans-acting DNAzyme design with evolving delivery technologies could mark a turning point in the clinical translation of DNA-based therapeutics.

5. Conclusion

We report the successful evolution of trans-acting RNA-cleaving DNAzymes using a novel in vitro selection approach that employs natural mRNA sequences as substrates. The selected DNAzymes, DNZ-15 and DNZ-35a, effectively downregulate BCL-2 expression in human and mouse cancer models, induce apoptosis, and suppress tumor growth in vivo. Unlike conventional methods, our strategy does not require covalent substrate tethering, enabling the discovery of DNAzymes that act under more physiologically relevant conditions. This work not only demonstrates the therapeutic potential of DNAzymes targeting anti-apoptotic pathways but also establishes a scalable, generalizable framework for evolving gene specific DNAzymes for research and clinical applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

VVB, SSB, SRK, GVK and KS conceptualized and developed the idea of the proposed work. KS, UM, USK, and VVB collected the data for the work. KS, VVB and SSB formal analysis, supervision, methodology, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising the content. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Ethical Approval

Animal Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Northeast Technical Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (NETES) Registration no (1996/PO/RC/S/17/CPCSEA).

Disclosure

The funding source had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data Availability

Datasets used in this analysis are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), (Grant no: BT/PR16160/NER/95/87/2015) - and the Department of Pharmaceuticals (DOP), Government of India.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Koch, T.; Menger, M.; Sticht, H.; Jäschke, A. A Computational Approach to Identify Efficient RNA Cleaving 10–23 DNAzymes. NAR Genomics Bioinform. 2023, 5(1), lqac098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Khanna, A.; Bhatia, S. DNAzymes: Expanding the Potential of Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Silverman, S. K. Development of 8–17 XNAzymes That Are Functional in Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145(27), 14758–14763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasuntharam, I.; Yehl, K.; Carroll, S. L.; Maxwell, J. T.; Martinez, M. D.; Che, P. L.; Brown, M. E.; Salaita, K.; Davis, M. E. Catalytic Deoxyribozyme-Modified Nanoparticles for RNAi-Independent Gene Regulation. ACS Nano 2012, 6(9), 7822–7831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, J.; Osterlund, E. J.; Andrews, D. W. BCL-2 Family Proteins: Changing Partners in the Dance towards Death. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25(1), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, R. M.; Muqbil, I.; Lowe, L.; Yedjou, C.; Hsu, H. Y.; Lin, L. T.; Siegelin, M. D.; Fimognari, C.; Kumar, N. B.; Dou, Q. P.; Yang, H.; Samadi, A. K.; Russo, G. L.; Spagnuolo, C.; Ray, S. K.; Chakraborty, S.; Wang, X.; El-Deiry, W. S. Broad Targeting of Resistance to Apoptosis in Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, S78–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. M.; Cory, S. The BCL-2 Apoptotic Switch in Cancer Development and Therapy. Oncogene 2007, 26(9), 1324–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbridge, A. R. D.; Grabow, S.; Strasser, A.; Vaux, D. L. Thirty Years of BCL-2: Translating Cell Death Discoveries into Novel Cancer Therapies. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16(2), 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souers, A. J.; Leverson, J. D.; Boghaert, E. R.; Ackler, S. L.; Catron, N. D.; Chen, J.; Dayton, B. D.; Ding, H.; Enschede, S. H.; Fairbrother, W. J.; Huang, D. C. S.; Hymowitz, S. G.; Jin, S.; Khaw, S. L.; Kovar, P. J.; Lam, L. T.; Lee, T.; Maecker, H. L.; Marsh, K. C.; Mason, K. D.; Mitten, M. J.; Nimmer, P.; Oleksijew, A.; Park, C. H.; Park, C. M.; Phillips, D. C.; Roberts, A. W.; Sampath, D.; Seymour, J. F.; Smith, M. L.; Sullivan, G. M.; Tahir, S. K.; Tse, C.; Wendt, M. D.; Xiao, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, H.; Humerickhouse, R. A.; Rosenberg, S. H.; Elmore, S. W. ABT-199, a Potent and Selective BCL-2 Inhibitor, Achieves Antitumor Activity While Sparing Platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19(2), 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [10]Mitten, M. J.; Nimmer, P.; Oleksijew, A.; Park, C. H.; Park, C. M.; Phillips, D. C.; Roberts, A. W.; Sampath, D.; Seymour, J. F.; Smith, M. L.; Sullivan, G. M.; Tahir, S. K.; Tse, C.; Wendt, M. D.; Xiao, Y.; Xue, J.; Zhang, H.; Humerickhouse, R. A.; Rosenberg, S. H.; Elmore, S. W. ABT-199, a Potent and Selective BCL-2 Inhibitor, Achieves Antitumor Activity While Sparing Platelets. Nat. Med. 2013, 19(2), 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, 249(4968), 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breaker, R. R.; Joyce, G. F. A DNA Enzyme with Mg²⁺-dependent RNA Phosphoesterase Activity. Chem. Biol. 1994, 1(4), 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D. W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2001.

- Maxam, A. M.; Gilbert, W. Sequencing End-Labeled DNA with Base-Specific Chemical Cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980, 65, 499–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchuk, D.; Drumm, M.; Saulino, A.; Collins, F. S. Construction of T-Vectors, a Rapid and General System for Direct Cloning of Unmodified PCR Products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991, 19(5), 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invitrogen. Opti-MEM® I Reduced Serum Medium Protocol; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA. https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/31985070 (accessed May 9, 2025).

- Invitrogen. Oligofectamine™ Transfection Reagent Protocol; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA. https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/12252011.

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate–Phenol–Chloroform Extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162(1), 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invitrogen. TRIzol™ Reagent User Guide; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA. https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/15596018 (accessed May 9, 2025).

- Thermo Scientific. Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit Protocol; Thermo Fisher Scientific: Waltham, MA. https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/AB1453B (accessed May 9, 2025).

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt Method. Methods 2001, 25(4), 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denizot, F.; Lang, R. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cell Growth and Survival. Modifications to the Tetrazolium Dye Procedure Giving Improved Sensitivity and Reliability. J. Immunol. Methods 1986, 89(2), 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermes, I.; Haanen, C.; Steffens-Nakken, H.; Reutelingsperger, C. The Use of Annexin V Binding in the Detection of Apoptosis. J. Immunol. Methods 1995, 184(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattanzi, G.; Pugliese, L.; Fabbri, S.; Capocefalo, D.; Tontodonati, M.; D’Orazio, M.; Prati, D.; Sani, E.; Gasbarrini, A. Detection of Apoptosis by Propidium Iodide and Annexin V in HepG2 Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Anticancer Res. 2005, 25 (2A), 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Xu, W. Development of a 4T1 Syngeneic Murine Model for Study of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 123, e55206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H.; Kim, E. A.; Kim, Y. S.; Lee, J. S.; Kim, M. J.; Jeong, H. W.; Lee, K. S.; Choi, Y. K. Establishment of a Syngeneic 4T1 Murine Model for Breast Cancer Research. Cancer Res. 2012, 72(24), 6741–6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Mishra, P.; Gupta, P.; Srivastava, V.; Patnaik, S.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, S.; Sahu, A.; Deshmukh, R.; Yadav, S. In Vivo Imaging of Tumor Progression Using High-Resolution Ultrasound and Color Doppler Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8(1), 17469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L. M.; Gertz, S.; Haan, G. B.; Kuipers, H.; Hogenhuis, J.; Rink, R.; Tolkach, Y.; Venkatesan, A.; Vermeij, M.; Groeneveld, M. In Vivo Tumor Imaging with Color Doppler and High-Frequency Ultrasound. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017, 36(4), 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U. K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins During the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227(5259), 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, L.; Hwang, P. M.; Kinzler, K. W.; Vogelstein, B. ** PUMA Induces the Rapid Apoptosis of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell 2001, 7, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villunger, A.; Michalak, E. M.; Coultas, L.; Müllauer, F.; Böck, G.; Ausserlechner, M. J.; Adams, J. M.; Strasser, A. ** p53- and Drug-Induced Apoptotic Responses Mediated by BH3-Only Proteins PUMA and Noxa. Science 2003, 302, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsan, A.; Yee, E.; Harlan, J. M. ** Endothelial Cell Death Induced by Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Is Inhibited by the BCL-2 Family Member, A1. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 27201–27204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhagalov, I.; St John, A.; He, Y. W. ** The Antiapoptotic Protein Bcl-xL Is Not Required for Thymocyte Survival but Regulates the Survival of Peripheral T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulaski, B. A.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. Mouse 4T1 Breast Tumor Model. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2001, Chapter 20, Unit 20.2. [CrossRef]

- Aslakson, C. J.; Miller, F. R. Selective Events in the Metastatic Process Defined by Analysis of the Sequential Dissemination of Subpopulations of a Mouse Mammary Tumor. Cancer Res. 1992, 52(6), 1399–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Breaker, R. R.; Joyce, G. F. A DNA Enzyme That Cleaves RNA. Chem. Biol. 1994, 1(4), 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, S. W.; Joyce, G. F. A General Purpose RNA-Cleaving DNA Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94(9), 4262–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachigian, L. M. Catalytic DNAzymes as Potential Therapeutic Agents and Sequence-Specific Molecular Tools to Dissect Biological Function. J. Clin. Invest. 2000, 106(10), 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Song, C.; Lim, I. G.; Krilis, S. A.; Geczy, C. L.; McNeil, H. P. DNAzyme Targeting c-jun Suppresses Skin Cancer Growth. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4(139), 139ra82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, A. S.; Sabbagh, H.; Liddane, A.; Raufi, A.; Kandouz, M.; Al-Katib, A. PNT2258, a Novel Deoxyribonucleic Acid Inhibitor, Induces Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Hematologic Malignancies by Targeting BCL-2. Oncotarget 2016, 7(8), 10287–10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Sun, L.-Q. Selection and Antitumor Activity of Anti-Bcl-2 DNAzymes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 479(3), 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, L. M.; Pitout, I. L.; Keegan, N. P.; Veedu, R. N.; Fletcher, S. DNAzymes: Expanding the Potential of Nucleic Acid Therapeutics. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2023, 33(3), 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Silverman, S. K. Therapeutic DNAzymes: From Structure Design to Clinical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35(32), 2300374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowska, Z.; Schubert, S.; Kurreck, J.; Erdmann, V. A. Deletion Analysis in the Catalytic Region of the 10–23 DNA Enzyme. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579(2), 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, N.; Stein, C. A. Potential Roles of Antisense Oligonucleotides in Cancer Therapy: The Example of Bcl-2 Antisense Oligonucleotides. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2002, 54(3), 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S. K. Therapeutic DNAzymes: From Structure Design to Clinical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35(32), 2300374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J. Aptamer-Guided Gene Therapy for Cancer Disease. Preprints 2024, 2024091836. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202409.1836/v1.

- Zhou, J.; Rossi, J. Aptamer-Guided Gene Therapy for Cancer Disease. Preprints 2024, 2024091836. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202409.1836/v1.

- Silverman, S. K. Therapeutic DNAzymes: From Structure Design to Clinical Applications. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35(32), 2300374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).