1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic malignancy, primarily because of its late-stage diagnosis, frequent recurrence, and drug resistance [

1,

2]. Although platinum-based chemotherapy combined with taxanes is the current standard of care [

3], the long-term prognosis of advanced ovarian cancer remains poor [

4]. Recently, maintenance therapy with poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, such as olaparib, significantly improved the progression-free survival of patients with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), including those harboring BRCA1/2 mutations [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, the clinical benefit of PARP inhibitors are frequently limited by the emergence of resistance, even in HRD-positive tumors. Known mechanisms of resistance include reversion mutations that restore BRCA function, epigenetic changes, and activation of alternative DNA repair pathways [

9,

10,

11].

A promising strategy for overcoming PARP inhibitor resistance involves combination therapy with agents that impair homologous recombination or sensitize tumor cells to DNA damage. Compounds such as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors, and agents inducing replication stress or oxidative damage, have been proposed as candidates for augmenting the efficacy of PARP inhibitor in preclinical models [

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, most of these agents remain investigational and lack clinical approval, limiting their immediate translational application.

Therefore, we performed high-throughput screening of 2,334 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved compounds for olaparib-sensitizing agents. By focusing on clinically available and orally administrated drugs, we identified ixazomib, a proteasome inhibitor, as a potent olaparib sensitizer. We explored the combined effects of olaparib and ixazomib, elucidated the underlying mechanisms, and demonstrated the antitumor efficacy of this approach in vitro and in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents.

Olaparib and Ixazomib were purchased from MedChemExpress Co. (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). Each compound was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a final concentration of 10 mM for use. Anti-PARP (#9542) and anti-phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) (#2971) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-GRP78 BiP antibody (ab21685), anti-Rad51 antibody [EPR4030(3)] (ab133534), and Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) (ab150080) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Compound Library.

The compound library comprised of 2,334 compounds from an FDA-Approved Drug Library (FDA-Approved Drug Library Mini, HY-L022M, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) provided by the Yamagata University Center of Excellence (YU-COE) and Yamagata University Drug Discovery Research Center.

2.3. Cell Culture.

The Human ovarian cancer cell lines used included A2780 (by Dr. Tsuruo [University of Tokyo] and Dr. R.F. Ozols and Dr. T.C. Hamilton [National Institute of Molecular and Cellular Biology, USA]), A2780CP (by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Osaka University), Caov-3 (purchased from American Type Culture Collection [ATCC]), ES2 (by Dr. Yaegashi, Tohoku University), HAC-2 (by Dr. Nishida, University of Tsukuba), JHOS-2 (purchased from RIKEN BioResource Center [RCB1521]), KURAMOCHI (purchased from JCRB cell bank [JCRB0098], OVCAR-3 (purchased from ATCC), RMG-1 (by Dr. Shiro Nozawa and Dr. Daisuke Aoki [Keio University]), SKOV-3 (purchased from ATCC), SKOV-3ip1 (by Dr. M.C. Hung [MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA]), and TOV-21G (purchased from ATCC). A2780, A2780CP, ES2, HAC2, and RMG-1 cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). OVCAR-3, SKOV-3, and SKOV-3ip1 cells were maintained in M199:105 medium (1:1 mixture of M199 and MCDB105 media) supplemented with 10% FBS, whereas TOV-21G cells were maintained with 15% FBS. Caov-3 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. JHOS-2 cells were cultured in DMEM/Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS supplemented with 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids. KURAMOCHI cells were cultured in RPMI1640 with 10% FBS. All culture media excluding JHOS-2 and KURAMOCHI were supplemented with an antibiotic-antimycotic mixture (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 250 ng/mL amphotericin B; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The culture medium was changed every three days.

2.4. Cell Proliferation Assay.

Human ovarian cancer cell lines were seeded at 5×10³ cells per well in 96-well plates and cultured at 37°C for 24 h. The cells were cultured for an additional 72 h in the presence of drugs. Cell viability was evaluated using a Cell Titer 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (MTS assay: Promega Corporation). Absorbance signals were measured using a Thermo Scientific Varioskan® Flash (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Tokyo, Japan). The IC₅₀ values for each drug were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 10.3.1 (464) for macOS.

2.5. Drug Screening.

Human ovarian cancer cell line A2780 was selected as a representative homologous recombination (HR)-proficient ovarian cancer cell line for initial screening because of their moderate sensitivity to olaparib and suitability for high-throughput assays16. A2780 was seeded at 5×10³ cells per well in 96-well plates. On the following day, cells were treated with a combination of 1 µM olaparib and 1 µM compound. Primary screening was performed to identify compounds that achieved ≥50% growth inhibition in the cell proliferation assay. Subsequently, using compounds identified in the primary screening, IC₅₀ values were calculated combined with 1 µM olaparib. Secondary screening was performed to identify oral drugs that satisfied the relationship IC₅₀ < Cmax (maximum blood concentration) and had lower IC₅₀ values than the compound alone. Furthermore, using the compounds identified in secondary screening, other human ovarian cancer cell lines were seeded at 5,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. On the following day, the cells were treated with 1 µM olaparib and 1 µM of the identified compound. Compounds that were effective against multiple cell lines were selected as the final candidate drugs.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis.

The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for 10 min. After centrifugation at 4°C and 14,000× g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected as the extracted protein. The protein concentration was measured using a DC™ protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The extracted proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The transferred membranes were blocked with nonfat dry milk or BSA and incubated with primary antibodies (all diluted 1:1,000), followed by incubation with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (all diluted 1:5,000) and detected using ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Buckinghamshire, England).

2.7. Cell Cycle Analysis.

Cell cycle analysis was performed using protease-free RNase A, DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and propidium iodide (PI, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were seeded at 2×10⁶ cells in 100 mm dishes and cultured at 37°C for 24 h. After an additional 48 h of culture in the presence of drugs, cells were adjusted to 2×10⁶ cells. Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol, incubated with 2 mL of 0.25 mg/mL solution for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were further stained with PI at a final concentration of 50 µg/mL for 30 min and measured using FACSMelody™ (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Data were analyzed using the FlowJo software version 10.1 (Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

2.8. RAD51 Foci Formation Assay.

RAD51 foci formation was measured by staining with Anti-Rad51 antibody, Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594) antibody, and DAPI Solution (1 mg/ml) (62248) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were seeded at 2×10⁴ cells in 60 mm dishes and cultured at 37°C for 24 h. After an additional 48 h of culture in the presence of drugs, cells were immunostained with primary antibodies diluted 1:1,000 and secondary antibodies, and observed using a confocal laser microscope LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.9. Xenograft Animal Model.

A2780 cells (1×10⁷ viable cells) were suspended in 200 µL PBS after viability measurement and injected subcutaneously into 5-6-week-old female BALB/cAjcl mice (CLEA JAPAN, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) to establish a subcutaneous xenograft model. After subcutaneous implantation, general health status and subcutaneous tumor evaluation were performed. The tumor volume was calculated as 1/2 × (length) × (width)² by measuring the longest diameter of the tumor and shortest perpendicular diameter. Olaparib (50 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally once daily for 21 days, and Ixazomib (2 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally twice weekly (days 1, 5, 8, 12, 15, and 19). Mice (n=3-6) were randomly assigned to four groups: control (DMSO), olaparib administration, ixazomib administration, and olaparib and ixazomib administration. Drug administration was initiated if tumor volume reached ≥100 mm³ after subcutaneous injection of cancer cells, and the animal experiment was terminated one week after completion of the three-week drug administration period. Animal experiments were conducted according to the protocols approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Yamagata University (R5131).

2.10. Statistical Analysis.

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed using a two-tailed Student's t-test, multiple t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Dunnett’s post-hoc test. Statistical significant was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of olaparib-sensitizing compounds from an FDA-approved drug library.

To identify clinically relevant compounds that enhance olaparib sensitivity, we screened a library of 2,334 FDA-approved drugs using A2780 ovarian cancer cells. Cells were treated with 1 μM olaparib alone or in combination with 1 μM of each compound. Seventy compounds demonstrated ≥50% inhibition of cell viability compared to olaparib alone. These hits were predominantly cancer-related drugs (n = 54), followed by agents for infectious and cardiovascular diseases (n = 5 each), and others targeting metabolism, immunity, or miscellaneous categories (

Table 1).

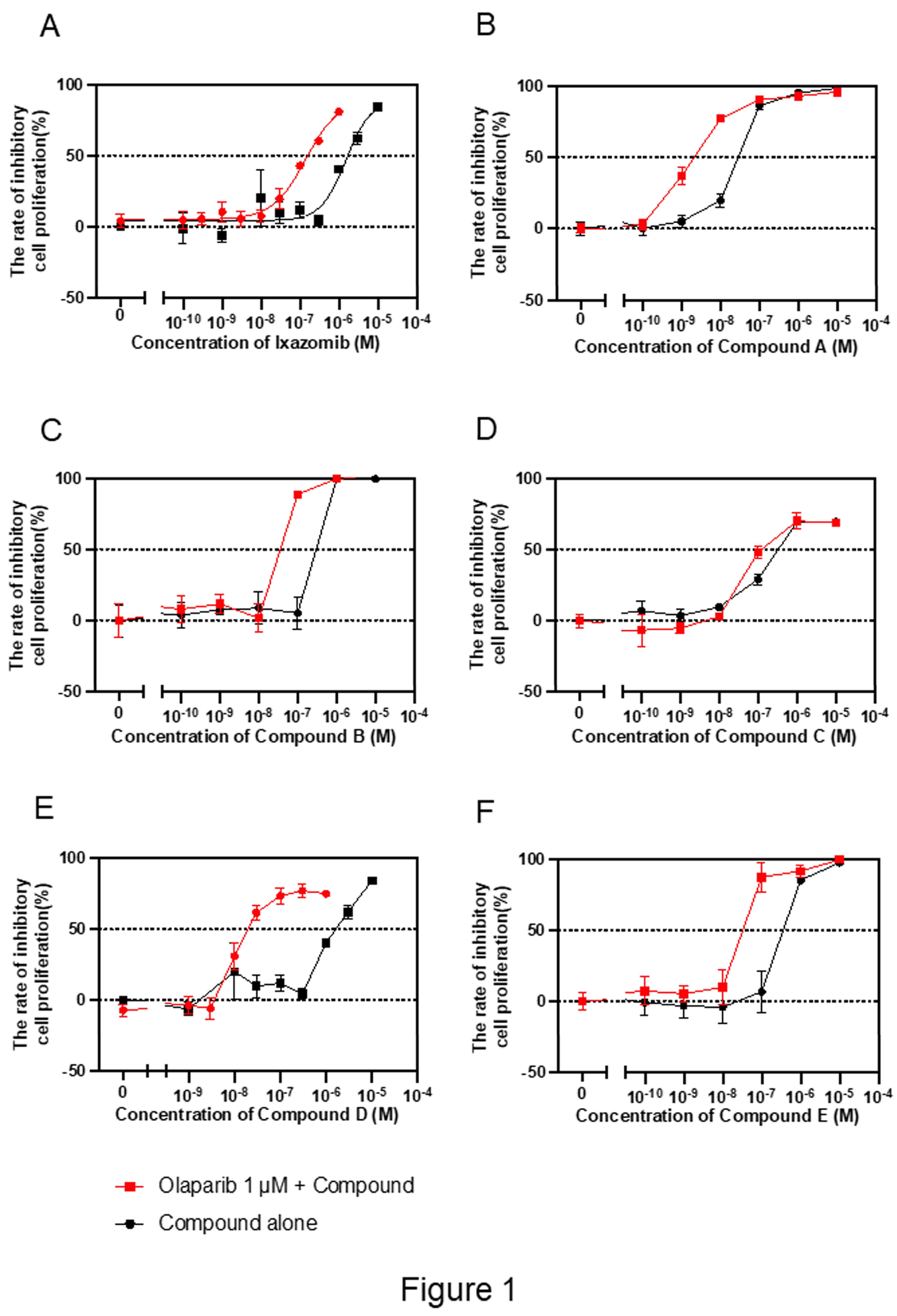

3.2. Secondary screening and selection of candidate drugs.

We evaluated dose-response effects of the 70 compounds combined with 1 μM olaparib. Fifty-four compounds exhibited synergistic or additive cytotoxicity. IC₅₀ values for these combinations were compared with clinically relevant maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) values. Seventeen compounds met the criterion of IC₅₀ < Cmax. Six orally available drugs approved in Japan were selected; ixazomib (proteasome inhibitor), and compounds A (HDAC inhibitor), B (antirheumatic), C (antimetabolite), D (microtubule inhibitor), and E (anti-alcoholism agent) (

Table 2,

Figure 1).

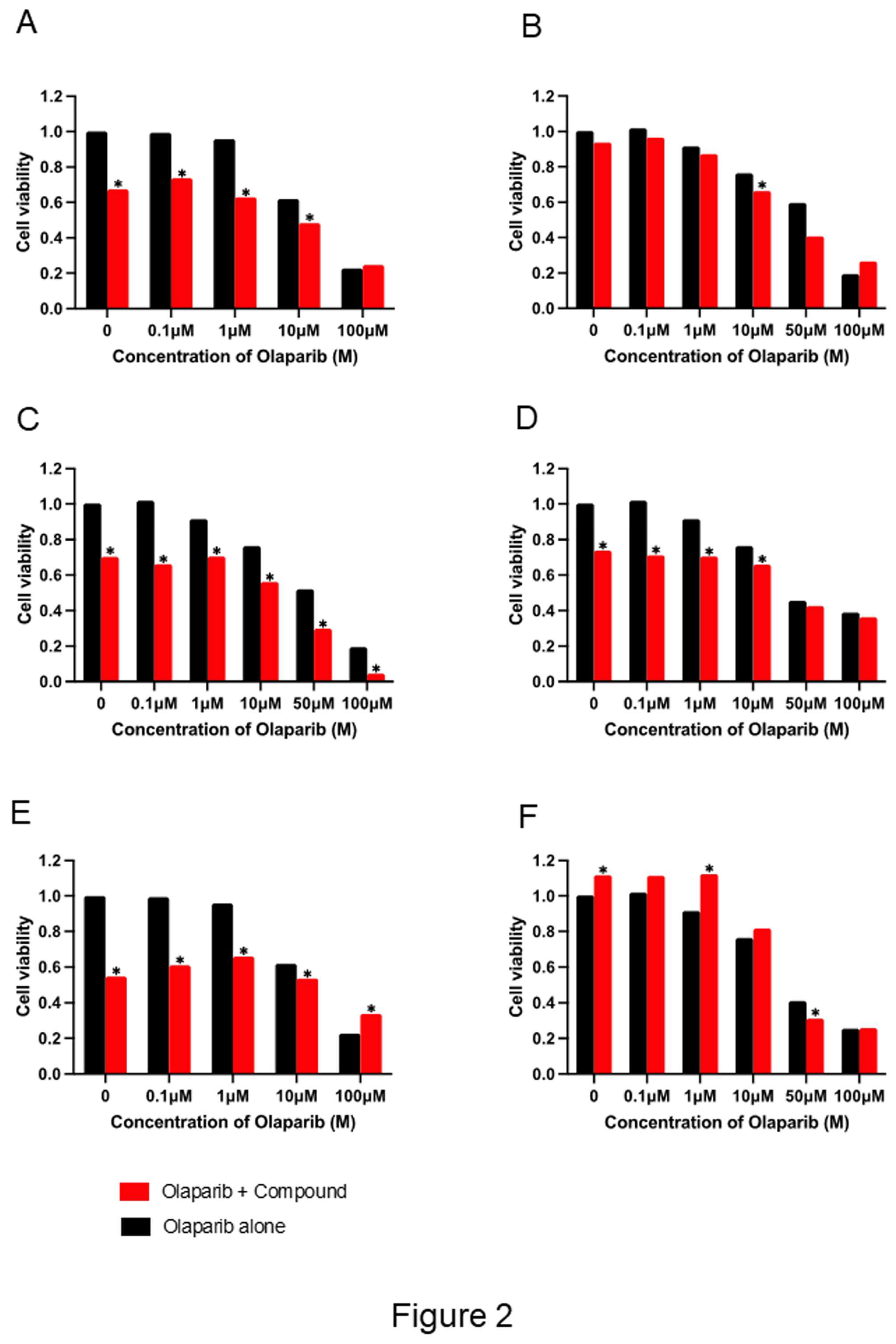

3.3. Enhanced olaparib cytotoxicity by selected drug combinations.

To validate the sensitizing potential of these compounds, A2780 cells were treated with each drug at fixed concentrations combined with varying doses of olaparib. All six combinations significantly enhanced olaparib-induced cytotoxicity compared to monotherapy (

Figure 2).

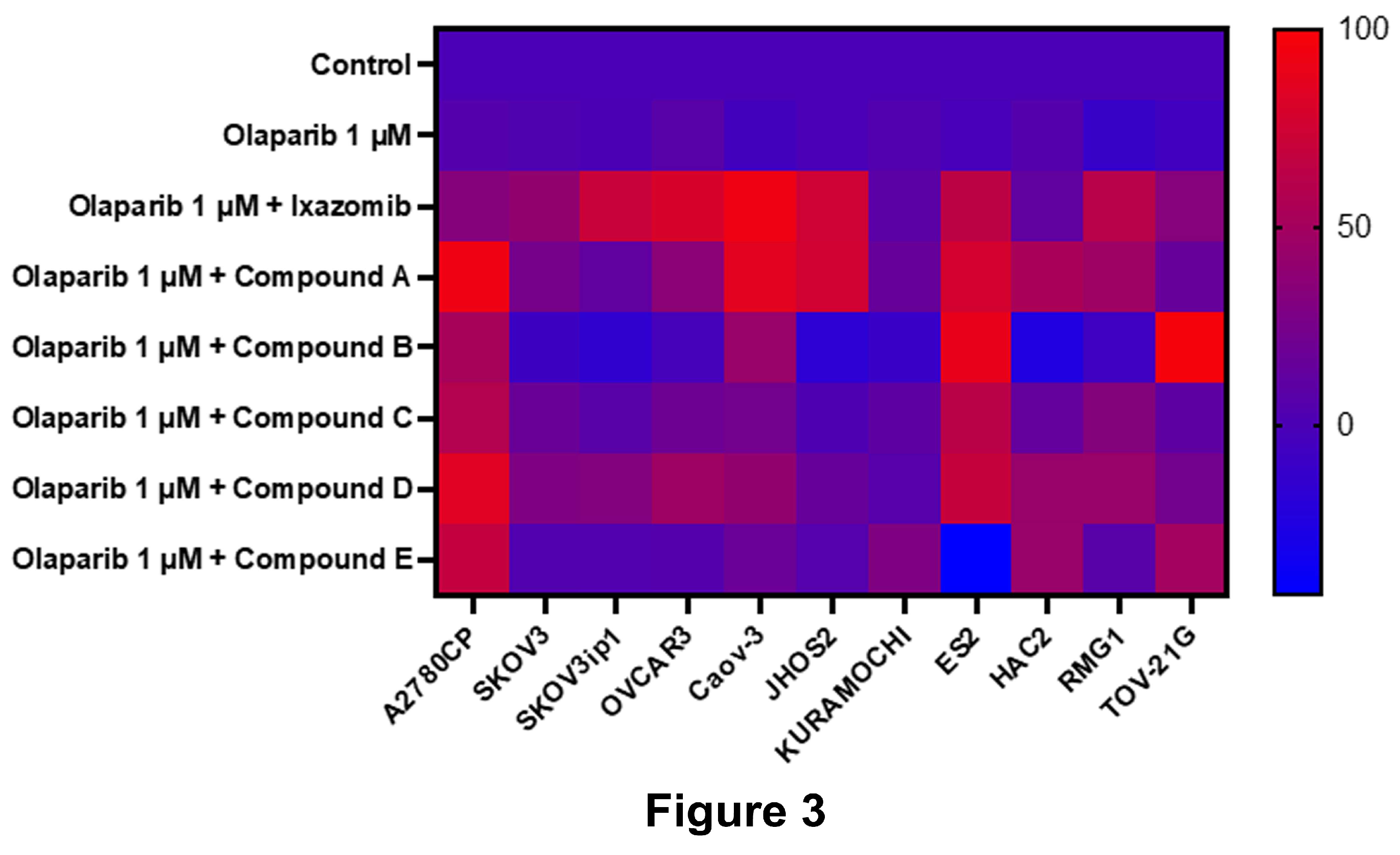

3.4. Evaluation of drug effects across multiple ovarian cancer cell lines

To assess reproducibility, 11 additional ovarian cancer cell lines were treated with 1 μM olaparib ± 1 μM of each compound. Ixazomib demonstrated the most consistent and robust sensitizing effect across all the tested lines (

Figure 3), prompting further investigation.

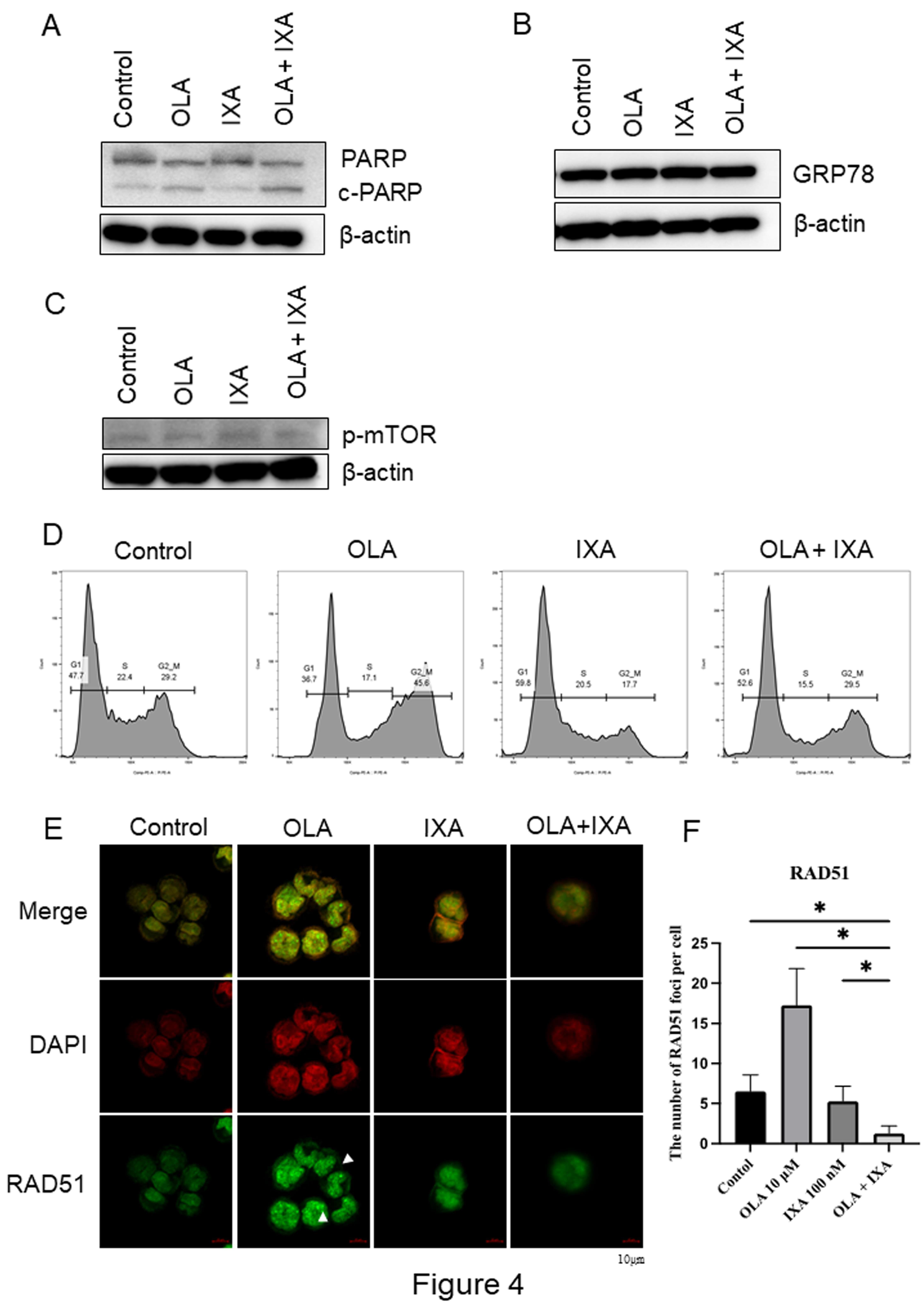

3.5. Mechanistic characterization of the olaparib–ixazomib combination.

Western blot analysis revealed that the combination of 10 μM olaparib and 100 nM ixazomib significantly increased cleaved PARP levels, indicating enhanced apoptosis compared to either drug alone (

Figure 4A). Neither GRP78 (endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress marker) nor phosphorylated mTOR levels were significantly altered (

Figure 4B and

Figure 4C), suggesting that these pathways were not involved.

Cell cycle analysis revealed that olaparib increased G2/M-phase accumulation, whereas ixazomib induced G1-phase accumulation. Their combination altered the cell cycle distribution consistent with dual checkpoint engagement (

Figure 4D).

Formation of RAD51 foci, a functional marker of homologous recombination (HR) repair, was significantly suppressed by ixazomib and further reduced by the combination treatment (

Figure 4E,

Figure 4F). As RAD51 facilitates DNA strand invasion at double-strand breaks17, decreased RAD51 foci indicate functional HR deficiency (HRD)18, providing a mechanistic basis for enhanced PARP inhibitor sensitivity.

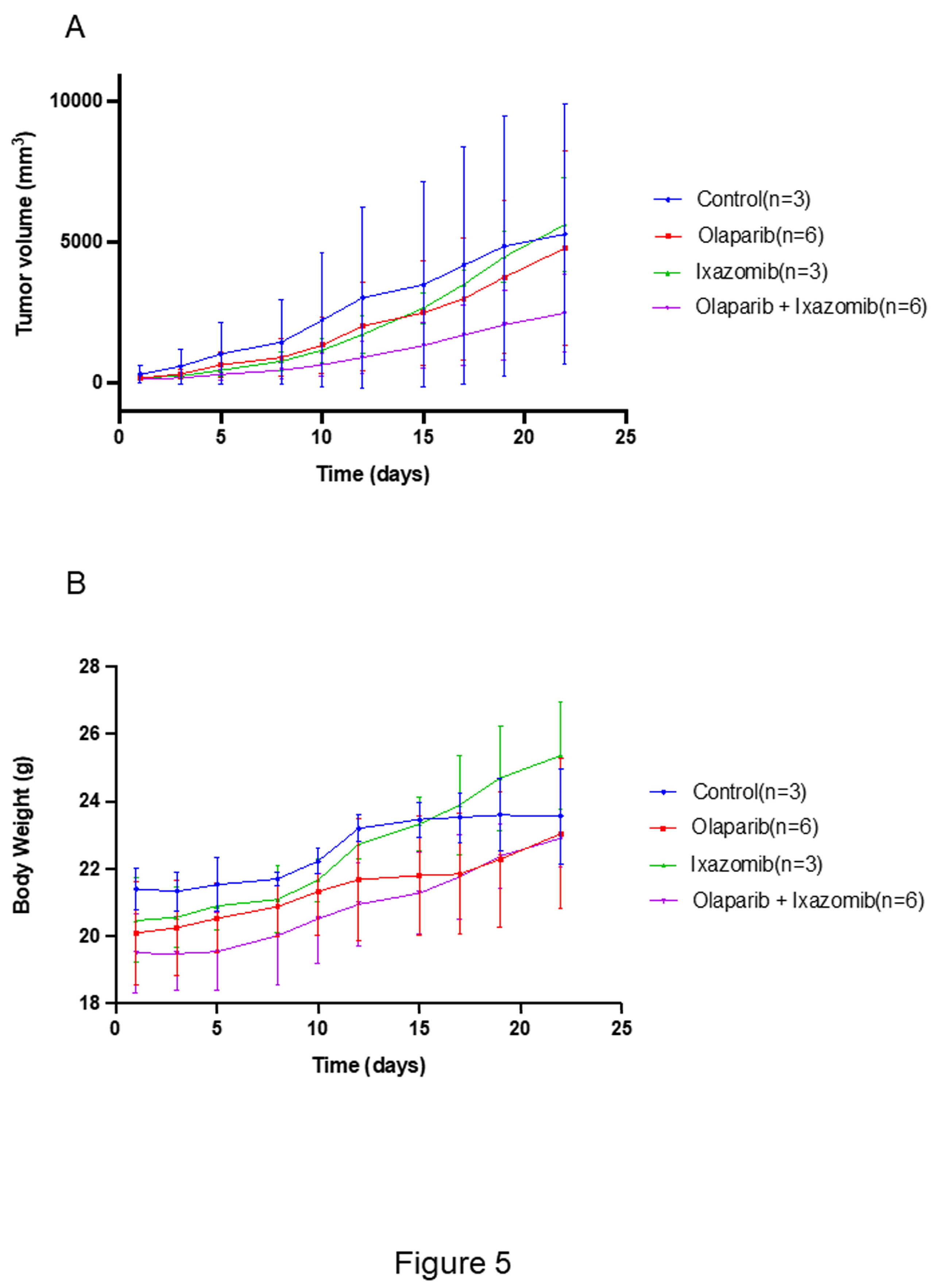

3.6. In vivo efficacy of the olaparib and ixazomib combination.

In a subcutaneous xenograft model using A2780 cells, mice treated with olaparib and ixazomib exhibited significantly reduced tumor volume compared to the monotherapy groups (

Figure 5A). The combination therapy was well tolerated, with no major toxicities and only a modest reduction in body weight (

Figure 5B).

4. Discussion

We screened a compound library composed exclusively of FDA-approved agents to identify compounds that enhance olaparib sensitivity in ovarian cancer cells—a strategy aimed at addressing the critical clinical challenge of resistance to PARP inhibitors. We identified six oral compounds that significantly augmented the cytotoxicity of olaparib (

Figure 2). These include the proteasome inhibitor ixazomib, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, antirheumatic drugs, antimetabolites, microtubule inhibitors, and anti-alcoholic agents. Several identified drugs have been previously reported to enhance the effects of PARP inhibitors through mechanisms such as impairment of homologous recombination (HDAC inhibitors)13, induction of oxidative stress and DNA damage (antirheumatic agents)15, and promotion of replication stress (antimetabolites)16. Microtubule inhibitors, including paclitaxel, have been shown to sensitize cells to PARP inhibitors19. Notably, the microtubule inhibitor identified in our study is non-cytotoxic and has not been previously reported in this context. Additionally, aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 (ALDH1A1), a target of anti-alcoholic agents, has been linked to PARP inhibitor resistance via the activation of non-homologous end-joining and, its inhibition has been reported to overcome olaparib resistance20.

Among the identified agents, ixazomib, a proteasome inhibitor, demonstrated the most potent and consistent enhancement of olaparib-induced growth inhibition across multiple ovarian cancer cell lines (

Figure 3). Thus, further analyses focused on the combination of ixazomib and olaparib. Mechanistic analysis revealed that the combination of olaparib and ixazomib increased apoptosis, as evidenced by elevated cleaved PARP expression (

Figure 4A). Proteasome inhibitors have been reported to increase ER stress, and induces apoptosis in cancer cells21, 22. Additionally, bertezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, induces apoptosis by inhibiting signal transduction pathways14. Interestingly, this enhancement was not mediated by ER stress or suppression of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway, as neither GRP78 nor phosphorylated mTOR levels were significantly altered (

Figure 4B, C). The combination treatment exerted differential effects on the cell cycle: olaparib increased the proportion of cells in the G₂/M phase, whereas ixazomib induced accumulation of cells in the G1 phase (

Figure 4D). Although olaparib and ixazomib have previously been reported to induce G2/M-phase cell-cycle arrest23, 24, our results indicated distinct arrest patterns under combination treatment. Our apoptosis and cell-cycle analyses suggest that these differences in the phase of cell-cycle arrest between olaparib and ixazomib may contribute to the observed enhancement of apoptosis. Here, formation of RAD51 foci, a marker of homologous recombination (HR) repair activity, was suppressed by ixazomib and further reduced by combination treatment, indicating that ixazomib may induce HR deficiency (HRD), thereby sensitizing cells to olaparib (

Figure 4E). RAD51 is a key protein in the early stages of homologous recombination repair, in which it forms nucleoprotein filaments at sites of DNA double-strand breaks and facilitates strand invasion and repair17. Formation of RAD51 foci is a commonly used surrogate marker for assessing HR repair activity, and its reduction is indicative of HRD18. Furthermore, RAD51 interacts with BRCA1 and BRCA2 to form a repair complex25, 26, and loss or functional inhibition of this interaction sensitizes cancer cells to PARP inhibitors27. Proteasome inhibition can impair HR function, thereby enhancing the efficacy of olaparib. These findings are consistent with previous reports showing that targeting RAD51 or its associated repair pathways can sensitize tumor cells to PARP inhibition14,18. Although RAD51 foci formation is typically used to identify the HRD status, an increase in RAD51 foci following PARP inhibitor treatment does not contradict this concept. PARPi induces replication stress and DNA double-strand breaks, which can activate HR in cells with preserved repair capacity. Accordingly, the induction of RAD51 foci under olaparib exposure indicates functional HR machinery and may represent a mechanism of PARPi resistance.

The combination therapy demonstrated significant antitumor efficacy in vivo. In the xenograft mouse model, tumor growth was significantly inhibited in the combination group compared to that in the monotherapy group (

Figure 5). Although a modest reduction in body weight was observed, no severe toxicities such as rash or diarrhea were noted, suggesting acceptable tolerability. Importantly, olaparib and ixazomib are orally administrable and have well-established safety profiles28, 29, making them attractive candidates for rapid clinical translation.

Knowingly, this is the first report to demonstrate the preclinical efficacy of a combination of the olaparib and ixazomib in ovarian cancer. Considering that both agents are orally administrated and clinically approved, this combination represents a practical and translatable strategy for overcoming resistance to PARP inhibitors. However, our study excluded models of acquired olaparib resistance. Therefore, future studies should investigate the therapeutic potential of this combination in olaparib-resistant models and assess its clinical relevance in a broader population of patients with ovarian cancer.

Overall, this study identified ixazomib as a potent enhancer of olaparib sensitivity in ovarian cancer by inducing functional HRD and promoting apoptosis. The combination of olaparib and ixazomib combination offers a promising therapeutic strategy for improving the outcomes of patients with PARP inhibitor-resistant ovarian cancer.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we identified ixazomib, an orally available proteasome inhibitor, as a potent sensitizer to olaparib in ovarian cancer cells through high-throughput screening of FDA-approved drugs. The combination of ixazomib and olaparib enhanced apoptosis, impaired homologous recombination by suppressing RAD51 foci formation, and exerted significant antitumor efficacy in vivo without severe toxicity. These findings suggest that ixazomib induces functional HRD and thereby augments the therapeutic benefit of PARP inhibition. Given the established clinical use and safety profile of both agents, this combination represents a promising and translatable therapeutic strategy to overcome PARP inhibitor resistance in ovarian cancer. Future studies should validate this approach in models of acquired resistance and explore its clinical applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.O., Y.O., and S.N.; methodology, Y.O. and T.O.; software, Y.O.; validation, T.O.; formal analysis, Y.O. and T.O.; investigation, Y.O., T.O., H.S., and M.S.; resources, Y.O., T.O., H.S., and M.S.; data curation, Y.O. and T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.O. and T.O.; writing—review and editing, T.O., Y.O., and S.N.; visualization, Y.O. and T.O.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, Y.O., T.O., and S.N.; funding acquisition, T.O. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Scientific KAKENHI (grant nos. 21K09509 to T.O. and 21K09532 to S.N.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yamagata University (Approval No. R6099).

Informed Consent Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the correspond-ing author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by YU-COE (Yamagata University Advanced Research Center Support Project) (S) Yamagata University Drug Discovery Research Center. We would like to thank Editage (

www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PARP |

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase |

| HRD |

homologous recombination deficiency |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| HDAC |

Histone Deacetylase |

| HR |

homologous recombination |

| ER |

endoplasmic reticulum |

| ALDH1A1 |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 |

References

- Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024 Jan-Feb;74(1):12-49.

- Dwivedi SKD, Rao G, Dey A, Mukherjee P, Wren JD, Bhattacharya R. Small Non-Coding-RNA in Gynecological Malignancies. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Mar 3;13(5):1085. [CrossRef]

- Bookman MA, Brady MF, McGuire WP, Harper PG, Alberts DS, Friedlander M, et al. Evaluation of new platinum-based treatment regimens in advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a Phase III Trial of the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 20;27(9):1419-25. [CrossRef]

- Kelliher L, Lengyel E. Understanding Long-Term Survival of Patients with Ovarian Cancer-The Tumor Microenvironment Comes to the Forefront. Cancer Res. 2023 May 2;83(9):1383-1385. [CrossRef]

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, et al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379: 2495-2505.

- Poveda A, Floquet A, Ledermann JA, Asher R, Penson RT,Oza AM, et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a final analysis of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021; 22(5): 620-631. [CrossRef]

- DiSilvestro P, Banerjee S, Colombo N, Scambia G, Kim BG, Oaknin A, Friedlander M, Lisyanskaya A, Floquet A, Leary A, Sonke GS, Gourley C, Oza A, González-Martín A, Aghajanian C, Bradley W, Mathews C, Liu J, McNamara J, Lowe ES, Ah-See ML, Moore KN; SOLO1 Investigators. Overall Survival With Maintenance Olaparib at a 7-Year Follow-Up in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer and a BRCA Mutation: The SOLO1/GOG 3004 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Jan 20;41(3):609-617. [CrossRef]

- Monk BJ, Barretina-Ginesta MP, Pothuri B, Vergote I, Graybill W, Mirza MR, McCormick CC, Lorusso D, Moore RG, Freyer G, O'Cearbhaill RE, Heitz F, O'Malley DM, Redondo A, Shahin MS, Vulsteke C, Bradley WH, Haslund CA, Chase DM, Pisano C, Holman LL, Pérez MJR, DiSilvestro P, Gaba L, Herzog TJ, Bruchim I, Compton N, Shtessel L, Malinowska IA, González-Martín A. Niraparib first-line maintenance therapy in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer: final overall survival results from the PRIMA/ENGOT-OV26/GOG-3012 trial. Ann Oncol. 2024 Nov;35(11):981-992. ;. [CrossRef]

- Fugger K, Hewitt G,West SC, Boulton SJ. Tackling PARP inhibitor resistance. Trends Cancer. 2021; 7(12): 1102-1118. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Liu ZY, Wu N, Chen YC, Cheng Q, Wang J. PARP inhibitor resistance: the underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol Cancer. 2020 Jun 20;19(1):107. [CrossRef]

- Goel N, Foxall ME, Scalise CB, Wall JA, Arend RC. Strategies in Overcoming Homologous Recombination Proficiency and PARP Inhibitor Resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021; 20(9): 1542-1549. [CrossRef]

- Valdez BC, Nieto Y, Yuan B, Murray D, Andersson BS. HDAC inhibitors suppress protein poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and DNA repair protein levels and phosphorylation status in hematologic cancer cells: implications for their use in combination with PARP inhibitors and chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncotarget. 2022 Oct 14;13:1122-1135. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Q, Dai Q, Zhao L, Zheng C, Li Q, Yuan Z, et al. Novel dual inhibitors of PARP and HDAC induce intratumoral STING-mediated antitumor immunity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024 Jan 5;15(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Neri P, Ren L, Gratton K, Stebner E, Johnson J, Klimowicz A, et al. Bortezomib-induced "BRCAness" sensitizes multiple myeloma cells to PARP inhibitors. Blood. 2011 Dec 8;118(24):6368-79.

- Freire Boullosa L, Van Loenhout J, Flieswasser T, Hermans C, Merlin C, Lau HW, et al. Auranofin Synergizes with the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib to Induce ROS-Mediated Cell Death in Mutant p53 Cancers. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023 Mar 8;12(3):667. [CrossRef]

- Xu J, Shen Y, Wang C, Tang S, Hong S, Lu W, et al. Arsenic compound sensitizes homologous recombination proficient ovarian cancer to PARP inhibitors. Cell Death Discov. 2021 Sep 22;7(1):259. PMID: 34552062; PMCID: PMC8458481. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya S, Srinivasan K, Abdisalaam S, Su F, Raj P, Dozmorov I, et al. RAD51 interconnects between DNA replication, DNA repair and immunity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 May 5;45(8):4590-4605. PMID: 28334891; PMCID: PMC5416901. [CrossRef]

- Cruz C, Castroviejo-Bermejo M, Gutiérrez-Enríquez S, Llop-Guevara A, Ibrahim YH, Gris-Oliver A, et al. RAD51 foci as a functional biomarker of homologous recombination repair and PARP inhibitor resistance in germline BRCA-mutated breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018 May 1;29(5):1203-1210. PMID: 29635390; PMCID: PMC5961353. [CrossRef]

- Yanaihara N, Yoshino Y, Noguchi D, Tabata J, Takenaka M, Iida Y, et al. Paclitaxel sensitizes homologous recombination-proficient ovarian cancer cells to PARP inhibitor via the CDK1/BRCA1 pathway. Gynecol Oncol. 2023 Jan;168:83-91. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Cai S, Han C, Banerjee A, Wu D, Cui T, et al. ALDH1A1 Contributes to PARP Inhibitor Resistance via Enhancing DNA Repair in BRCA2-/- Ovarian Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020 Jan;19(1):199-210. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan D, Tian Z, Zhou B, Kuhn D, Orlowski R, Raje N, Richardson P, Anderson KC. In vitro and in vivo selective antitumor activity of a novel orally bioavailable proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 against multiple myeloma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Aug 15;17(16):5311-21. [CrossRef]

- Dick LR, Fleming PE. Building on bortezomib: second-generation proteasome inhibitors as anti-cancer therapy. Drug Discov Today. 2010 Mar;15(5-6):243-9. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2010.01.008.

- Jelinic P, Levine DA. New insights into PARP inhibitors' effect on cell cycle and homology-directed DNA damage repair. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 Jun;13(6):1645-54. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly S, Kuravi S, Alleboina S, Mudduluru G, Jensen RA, McGuirk JP, Balusu R. Targeted Therapy for EBV-Associated B-cell Neoplasms. Mol Cancer Res. 2019 Apr;17(4):839-844. [CrossRef]

- Cousineau I, Abaji C, Belmaaza A. BRCA1 regulates RAD51 function in response to DNA damage and suppresses spontaneous sister chromatid replication slippage: implications for sister chromatid cohesion, genome stability, and carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2005 Dec 15;65(24):11384-91. PMID: 16357146. [CrossRef]

- Kwon Y, Rösner H, Zhao W, Selemenakis P, He Z, Kawale AS, et al. DNA binding and RAD51 engagement by the BRCA2 C-terminus orchestrate DNA repair and replication fork preservation. Nat Commun. 2023 Jan 26;14(1):432. PMID: 36702902; PMCID: PMC9879961. [CrossRef]

- Murai J, Pommier Y. BRCAness, Homologous Recombination Deficiencies, and Synthetic Lethality. Cancer Res. 2023 Apr 14;83(8):1173-1174. PMID: 37057596. [CrossRef]

- Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, Karamanesht I, Leleu X, Grishunina M, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):431-40. [CrossRef]

- Xie J, Wan N, Liang Z, Zhang T, Jiang J. Ixazomib - the first oral proteasome inhibitor. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019 Mar;60(3):610-618. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).