Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

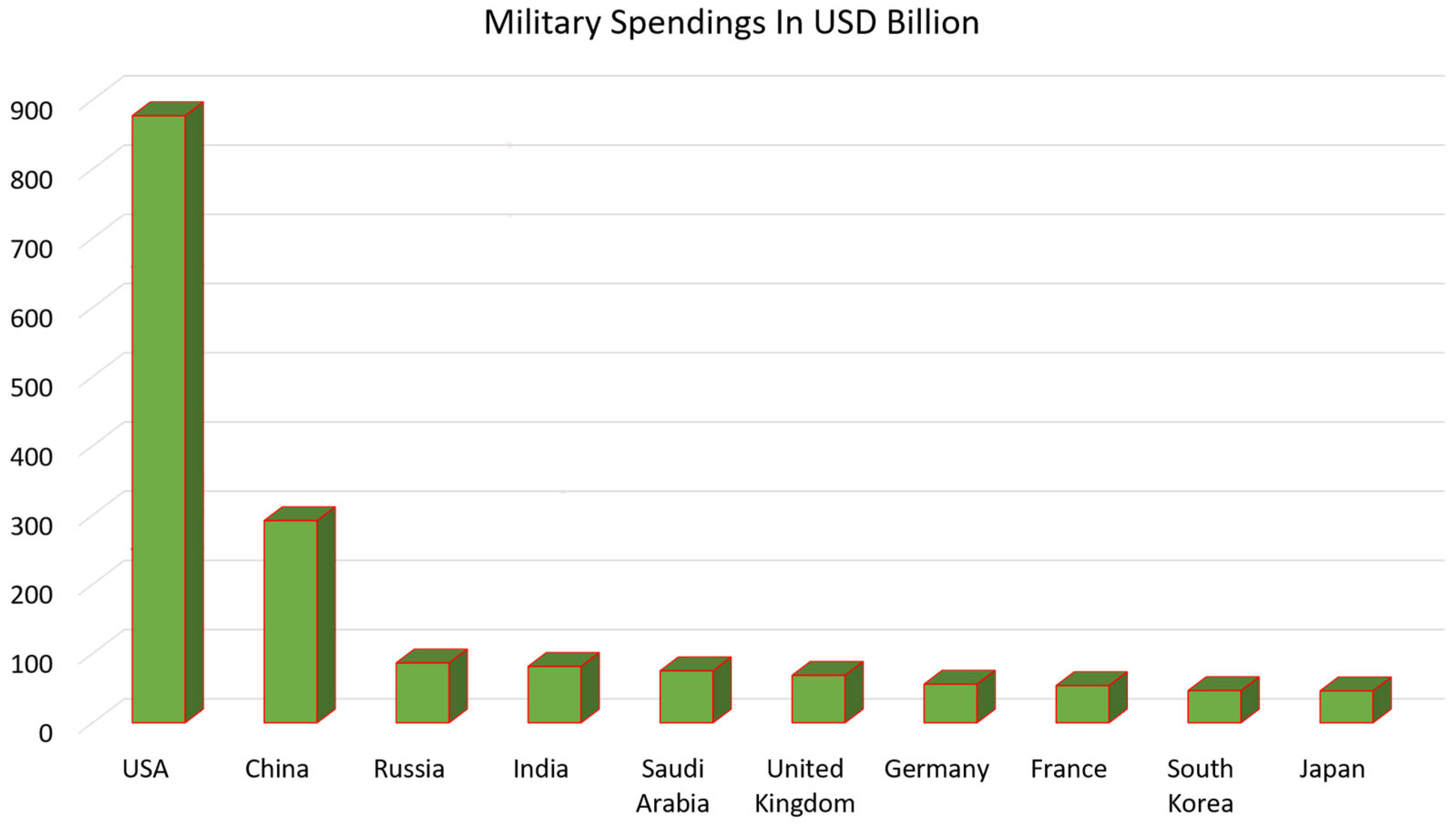

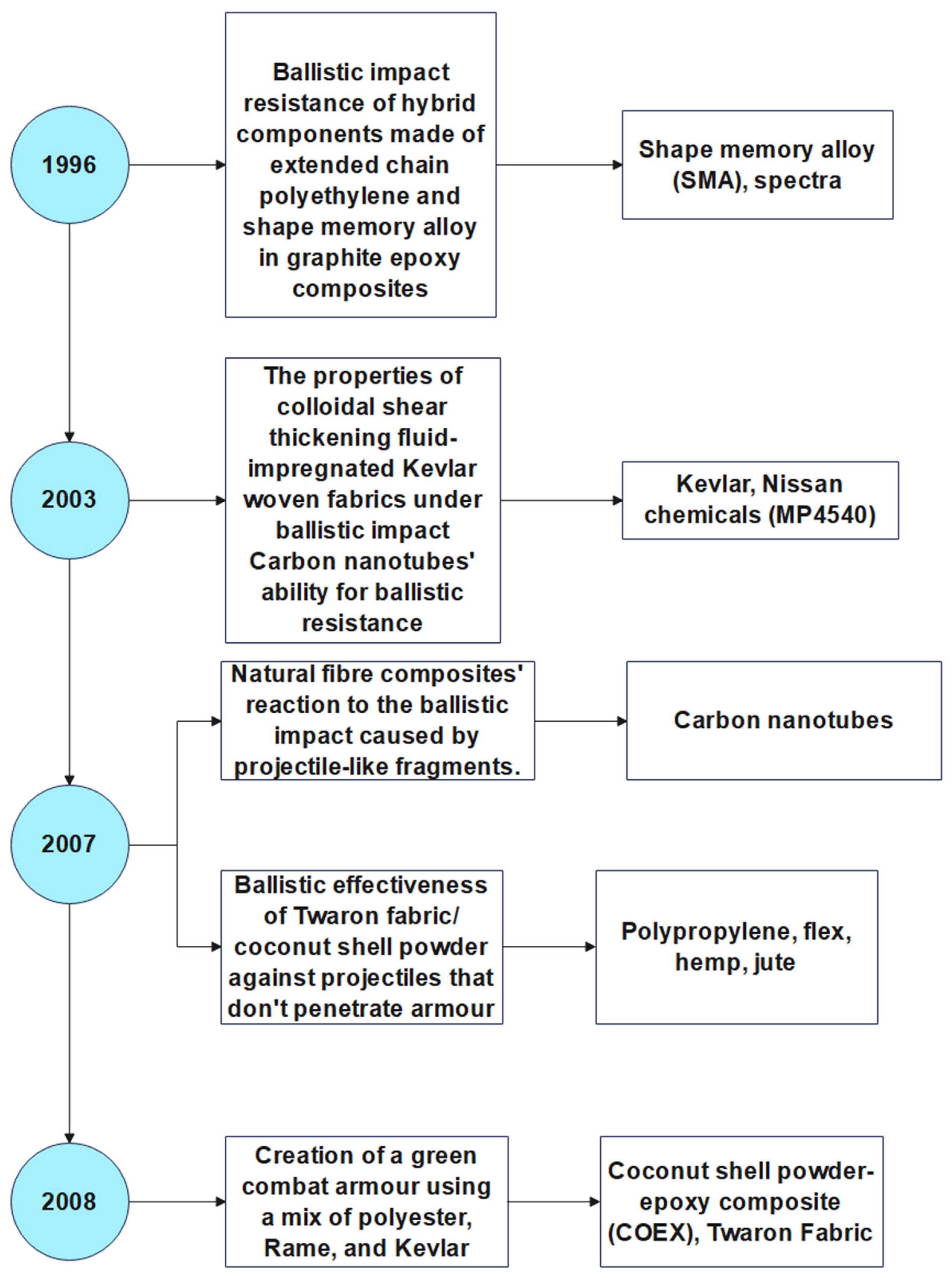

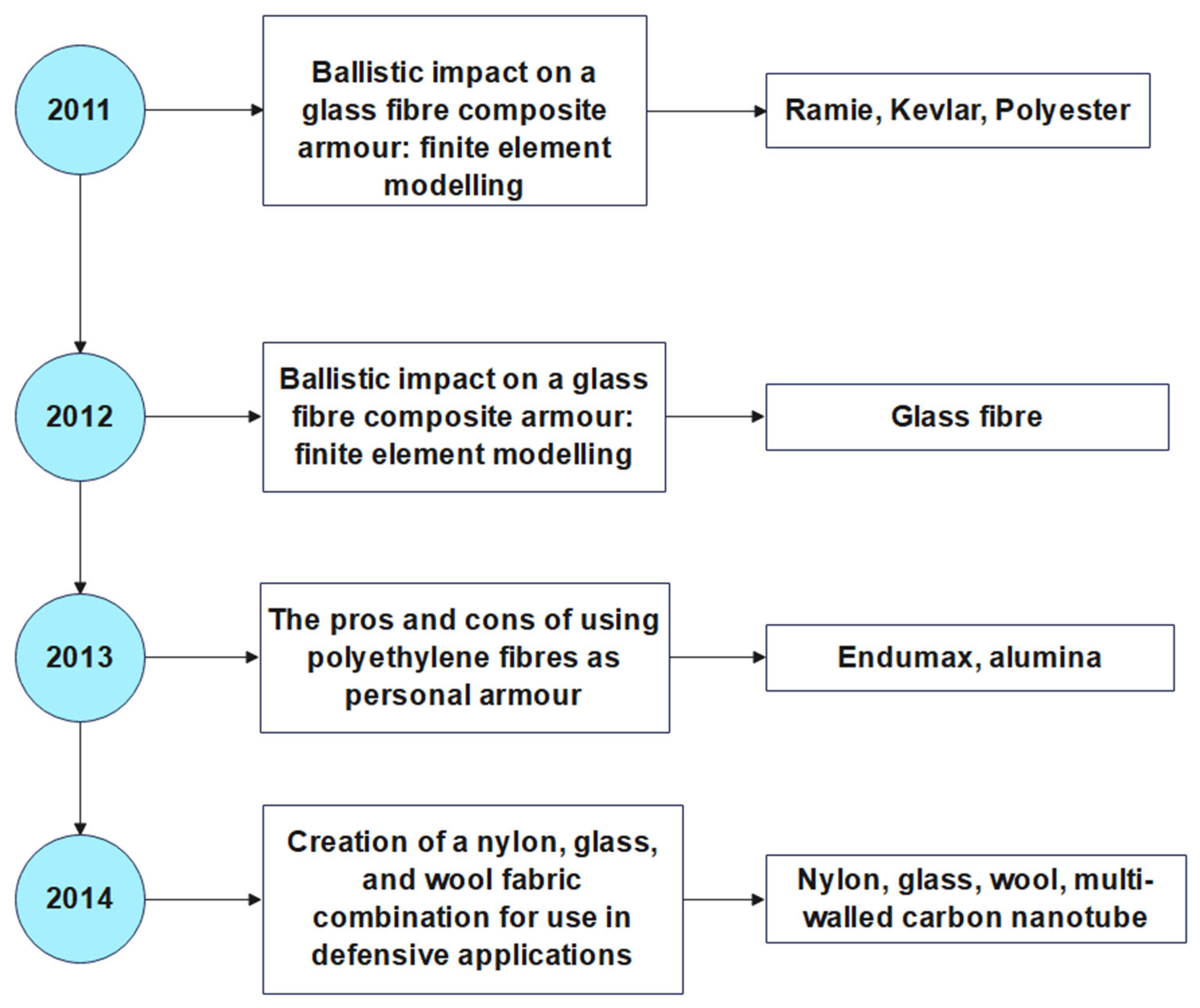

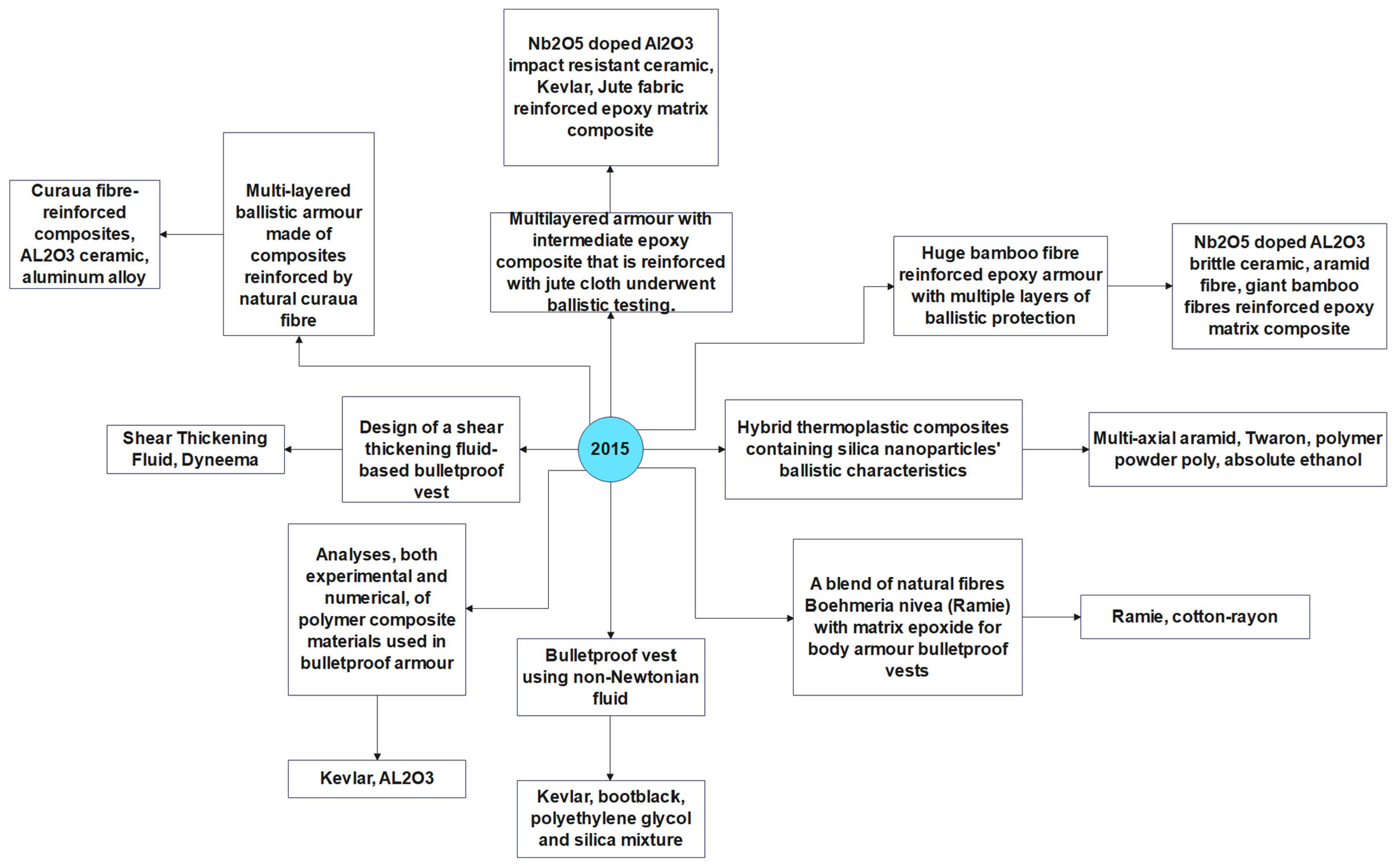

1. Introduction

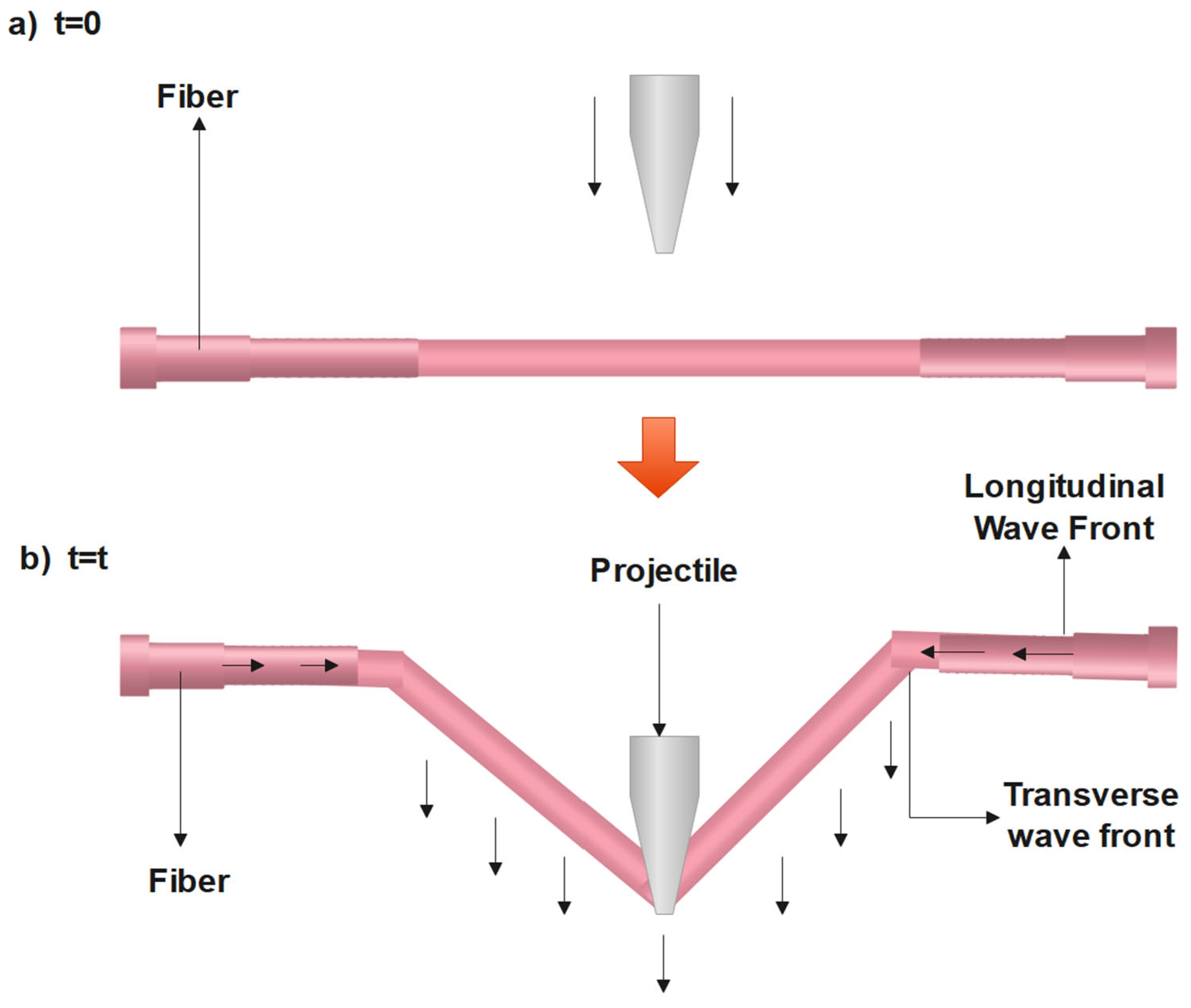

1.1. Polymer Composites

1.2. Natural Fibres

1.3. Kevlar Replacement

2. Results and Discussion

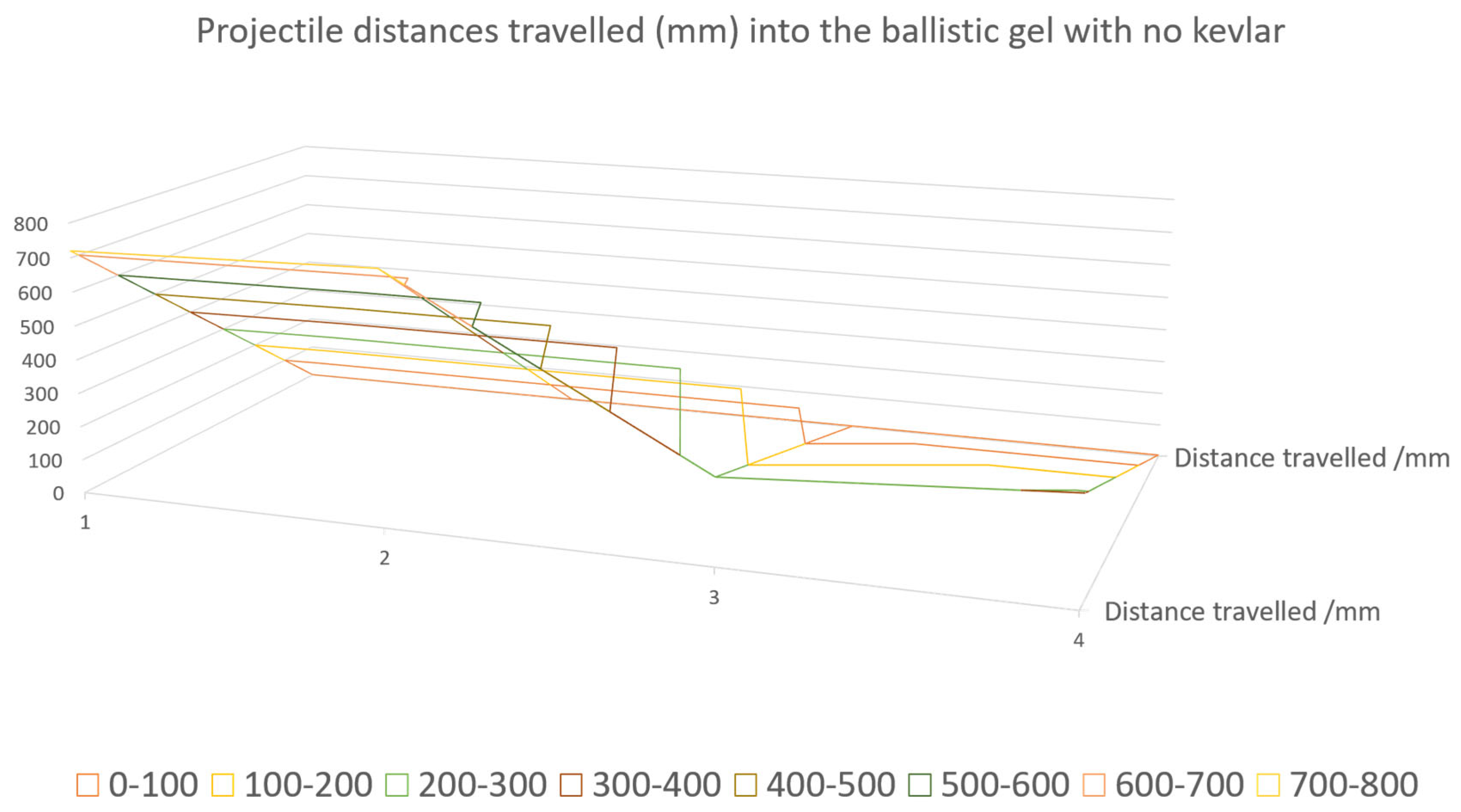

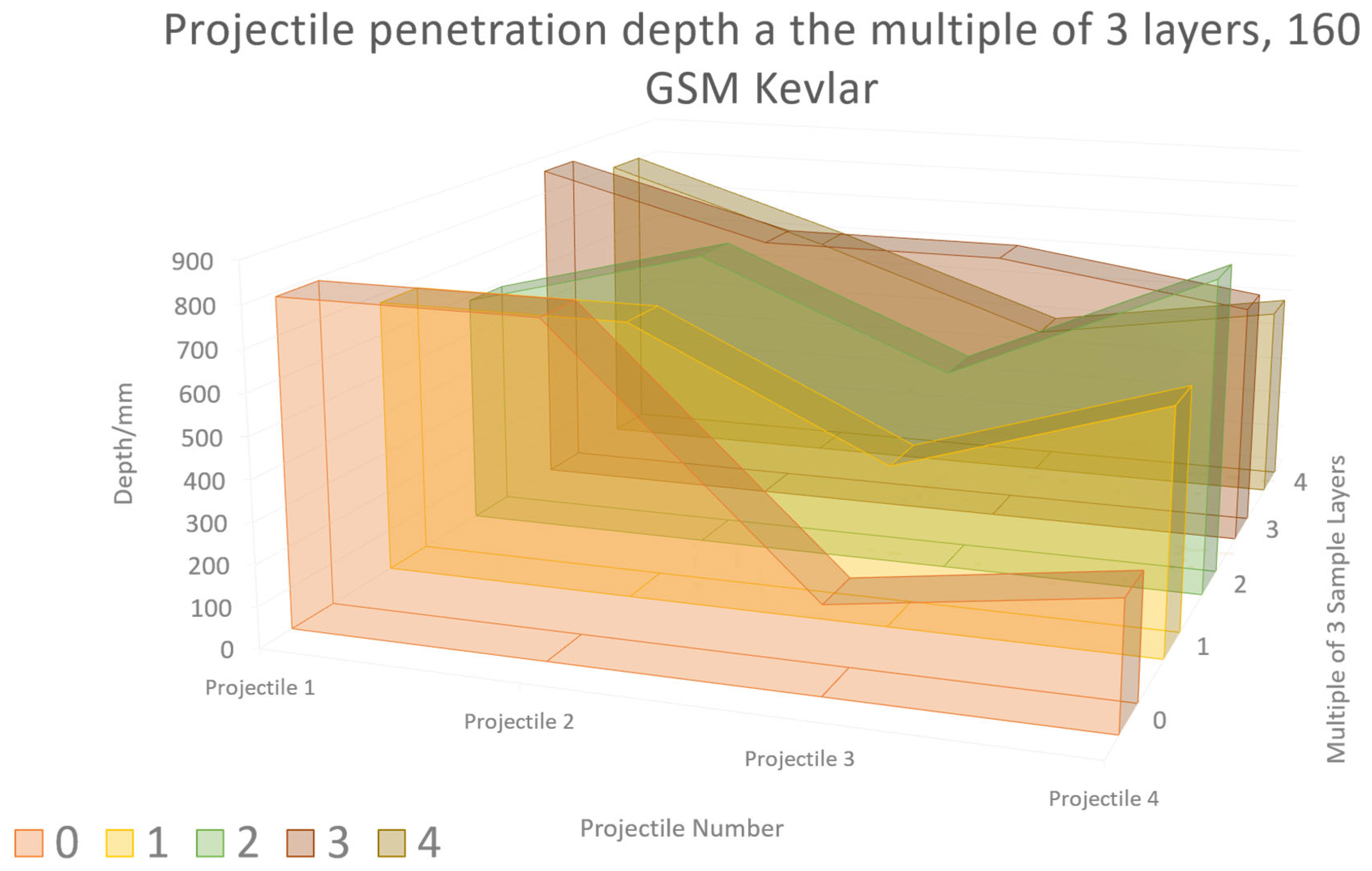

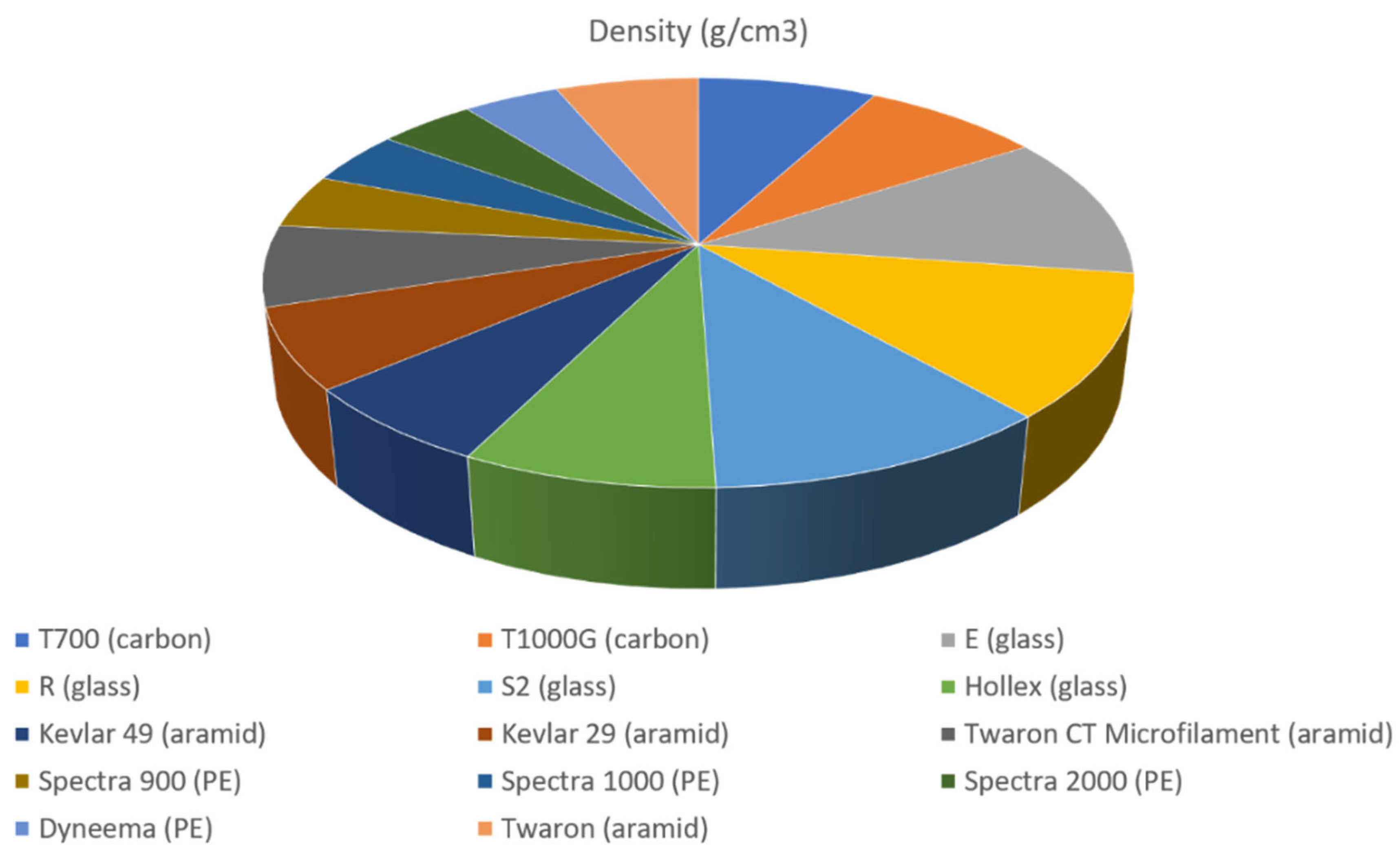

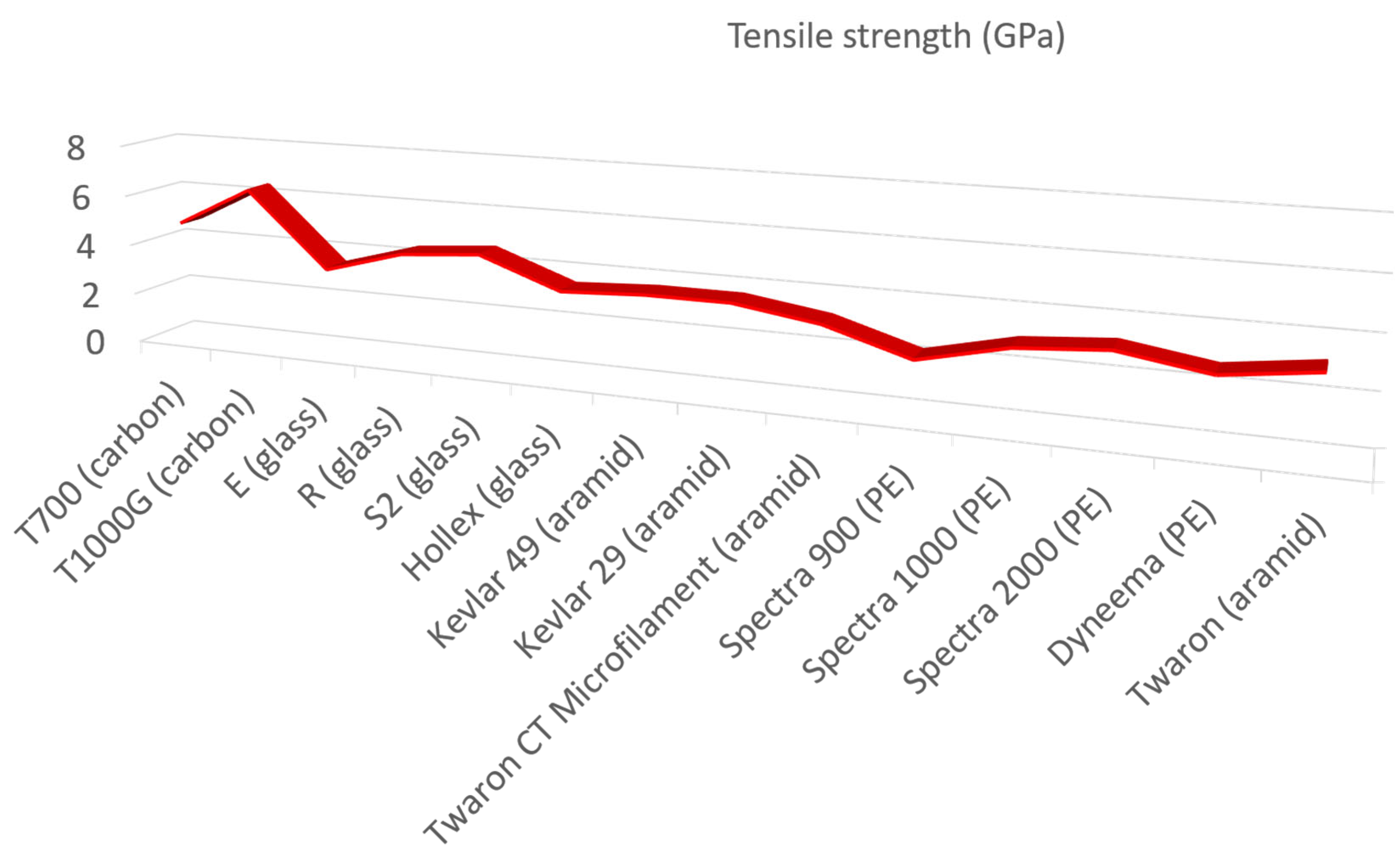

2.1. Kevlar

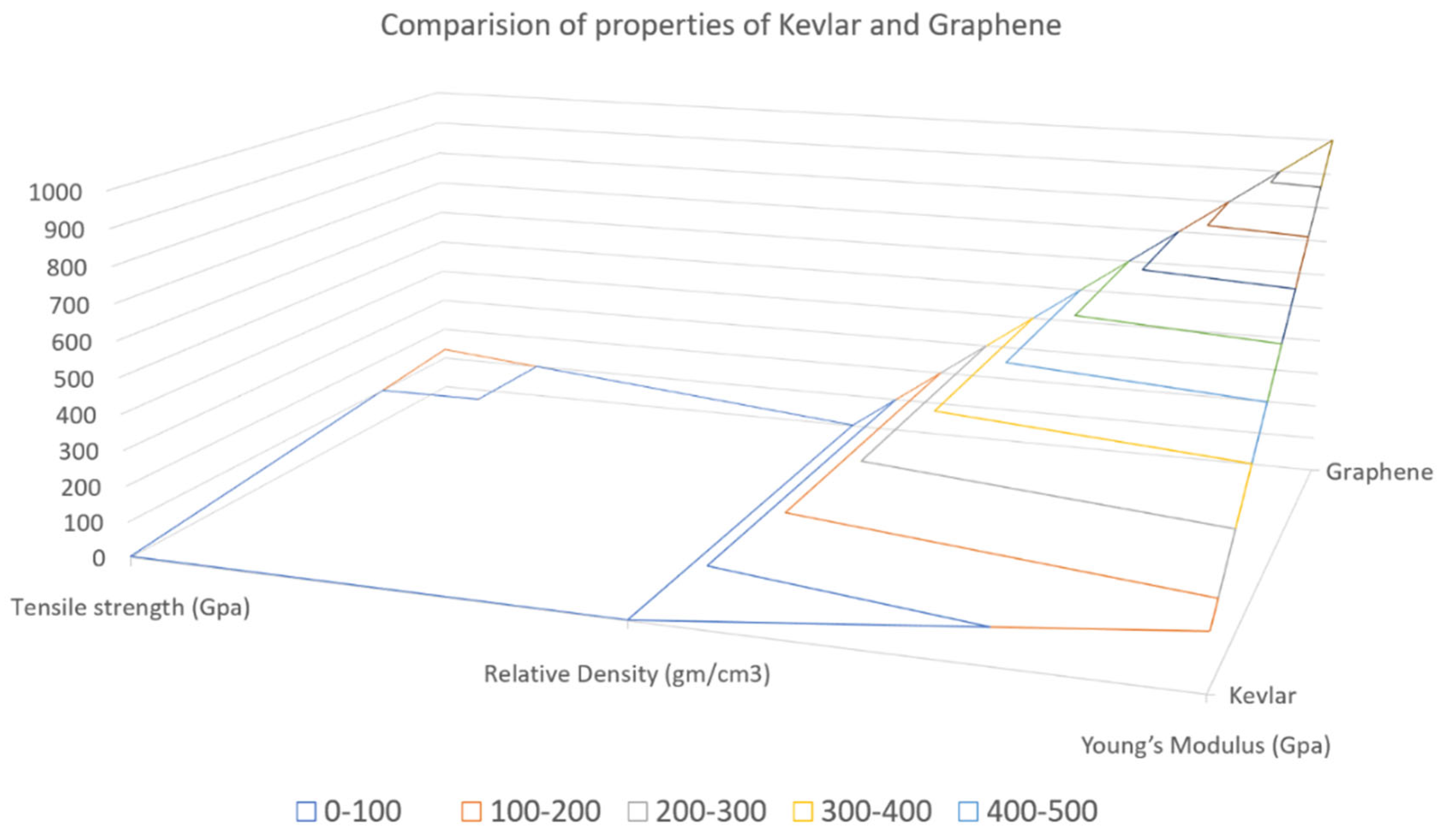

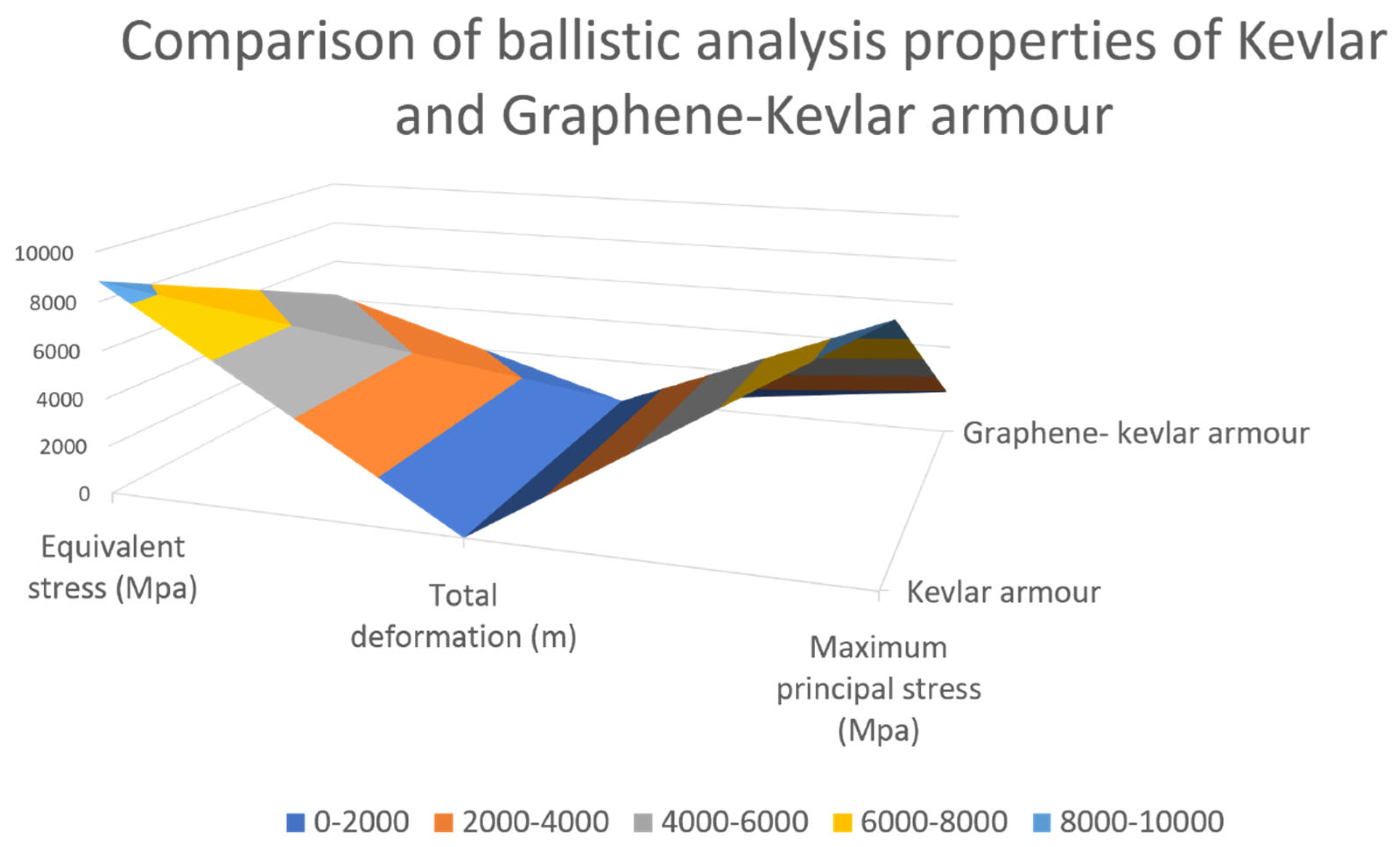

2.2. Graphene Nanosheets Reinforced Kevlar-29

2.2.1. Degradation of Kevlar Under UV Radiation and in Acidic/Alkaline Environment

2.3. Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites

2.4. Carbon Nanotube Polymer Composites

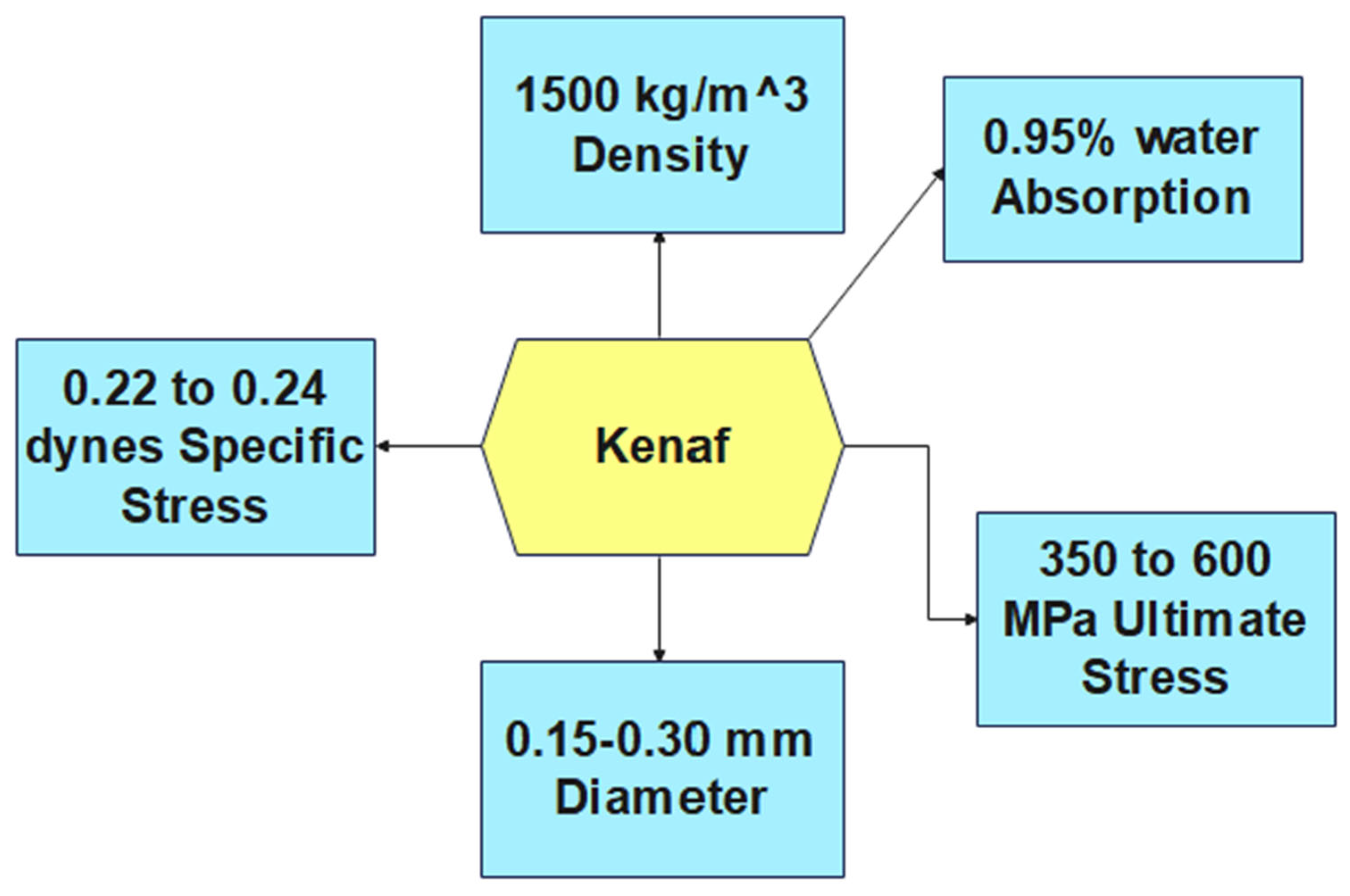

2.5 KENAF/X-Ray Film Hybrid Composites

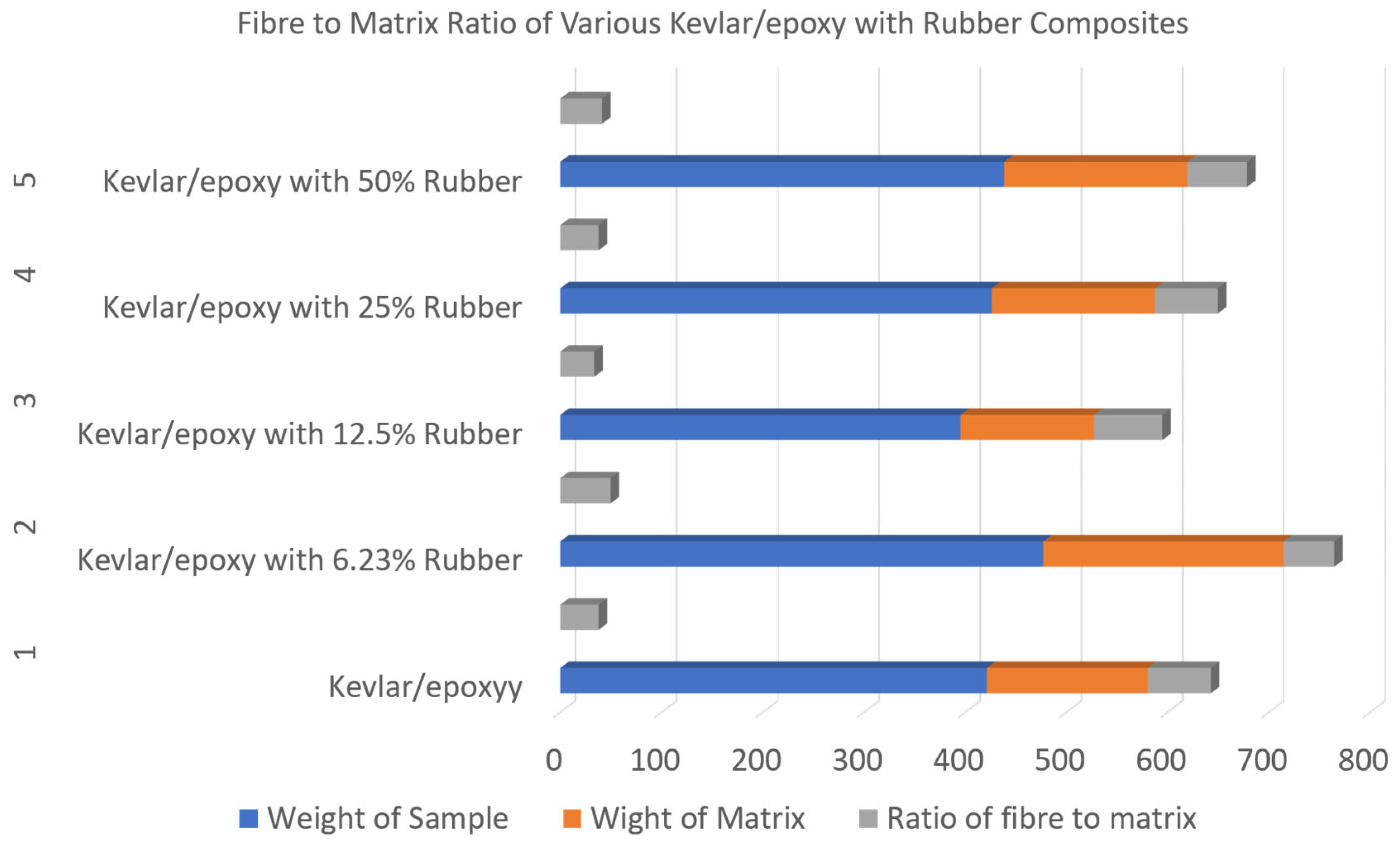

2.6. Rubber Particles in Kevlar Reinforced Polymer Composites

2.7. Polymer Laminates in Light Bullet Proof Vests

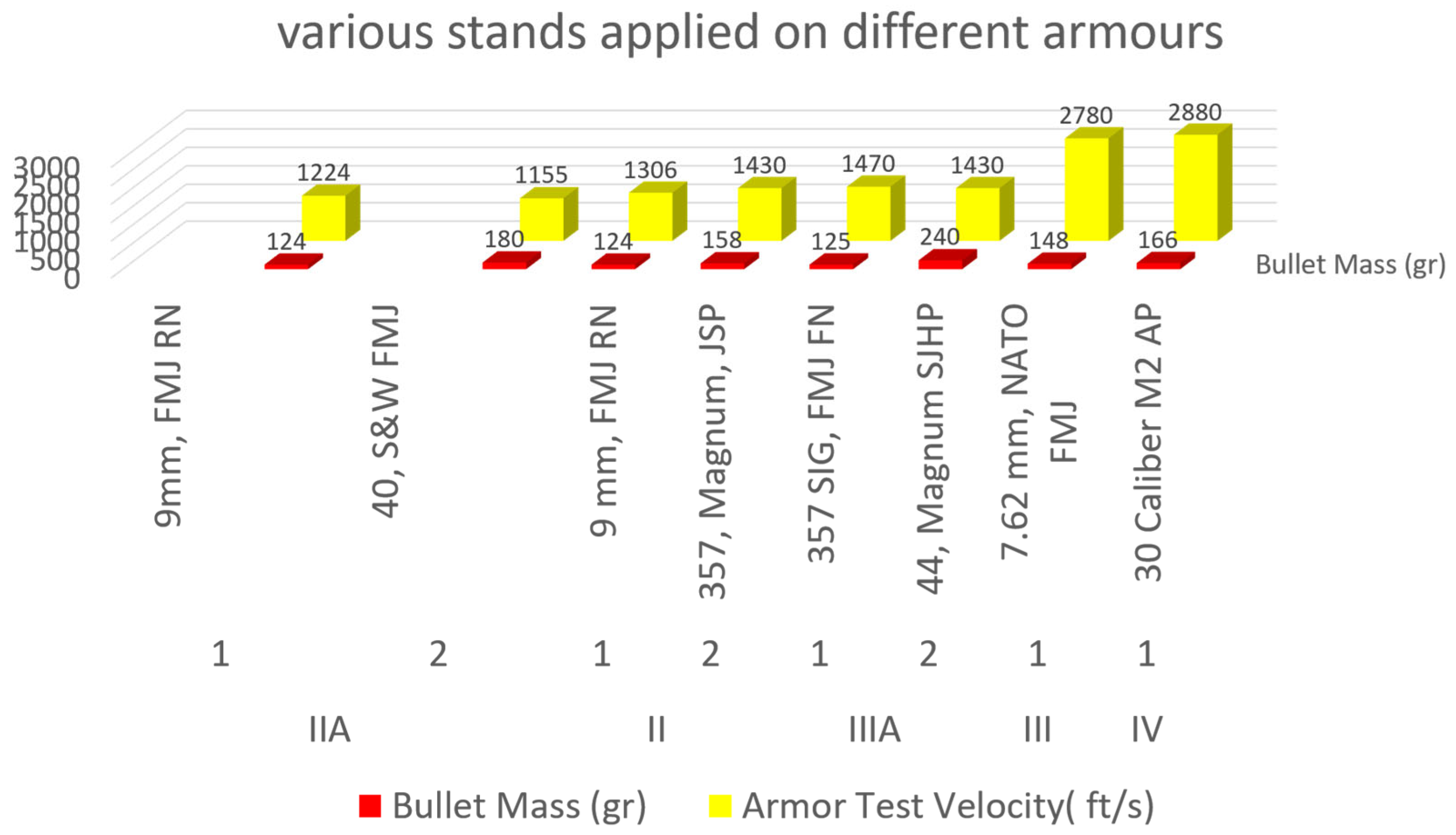

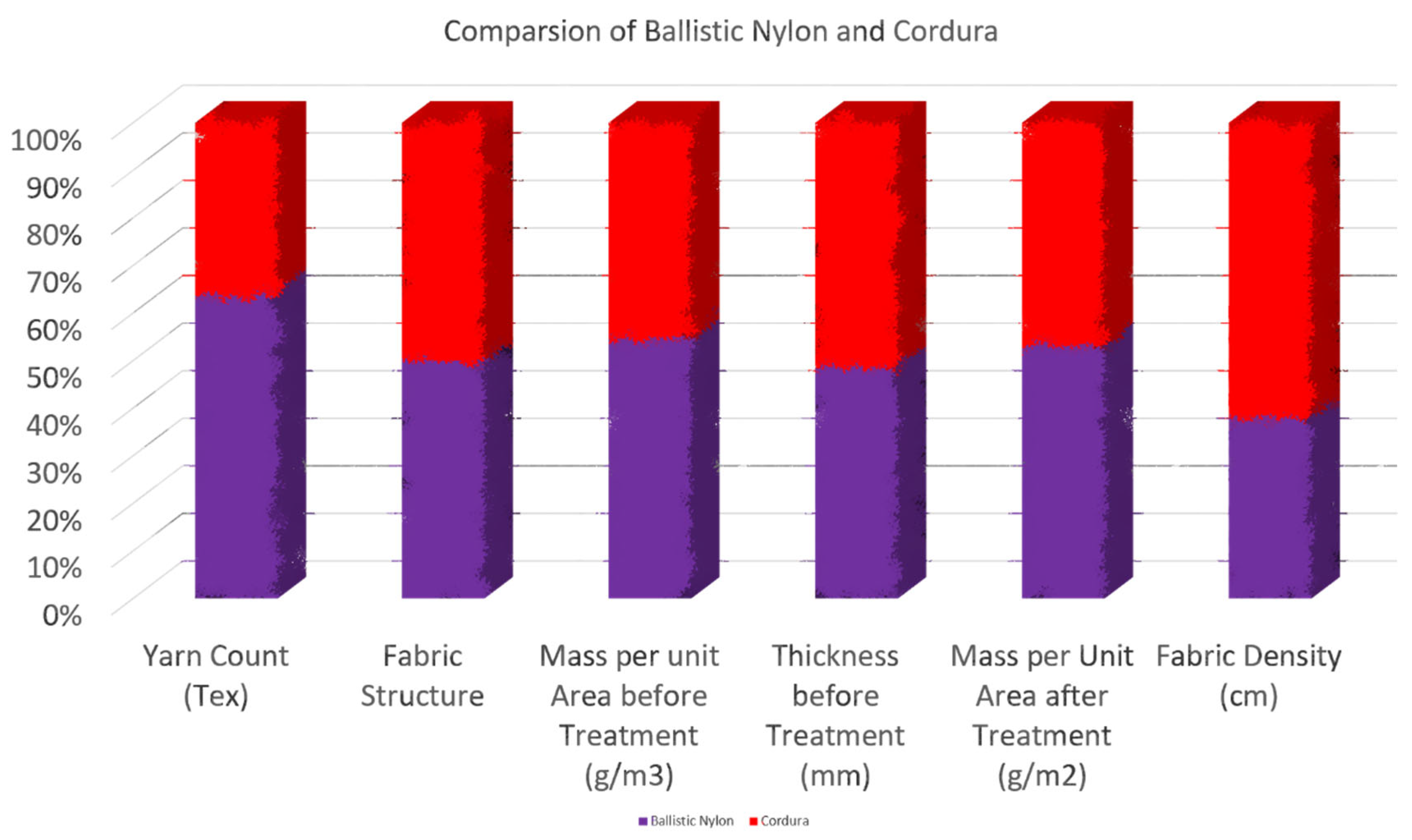

2.8. Cordura and Ballistic Nylon

2.9. Twip Steel, Water and Polymer Sandwich Composite

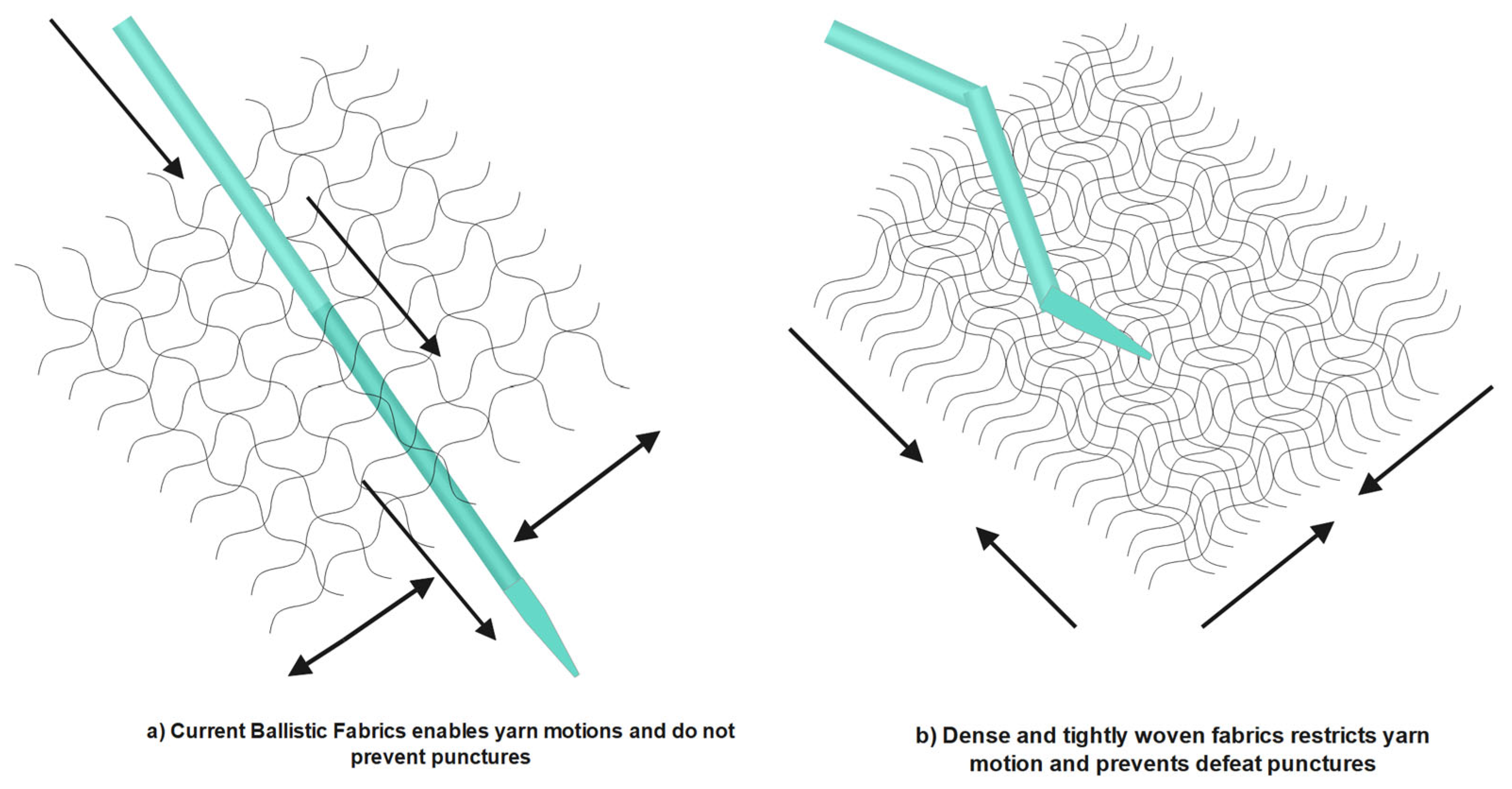

2.10. Textile Materials (Woven Fabrics)

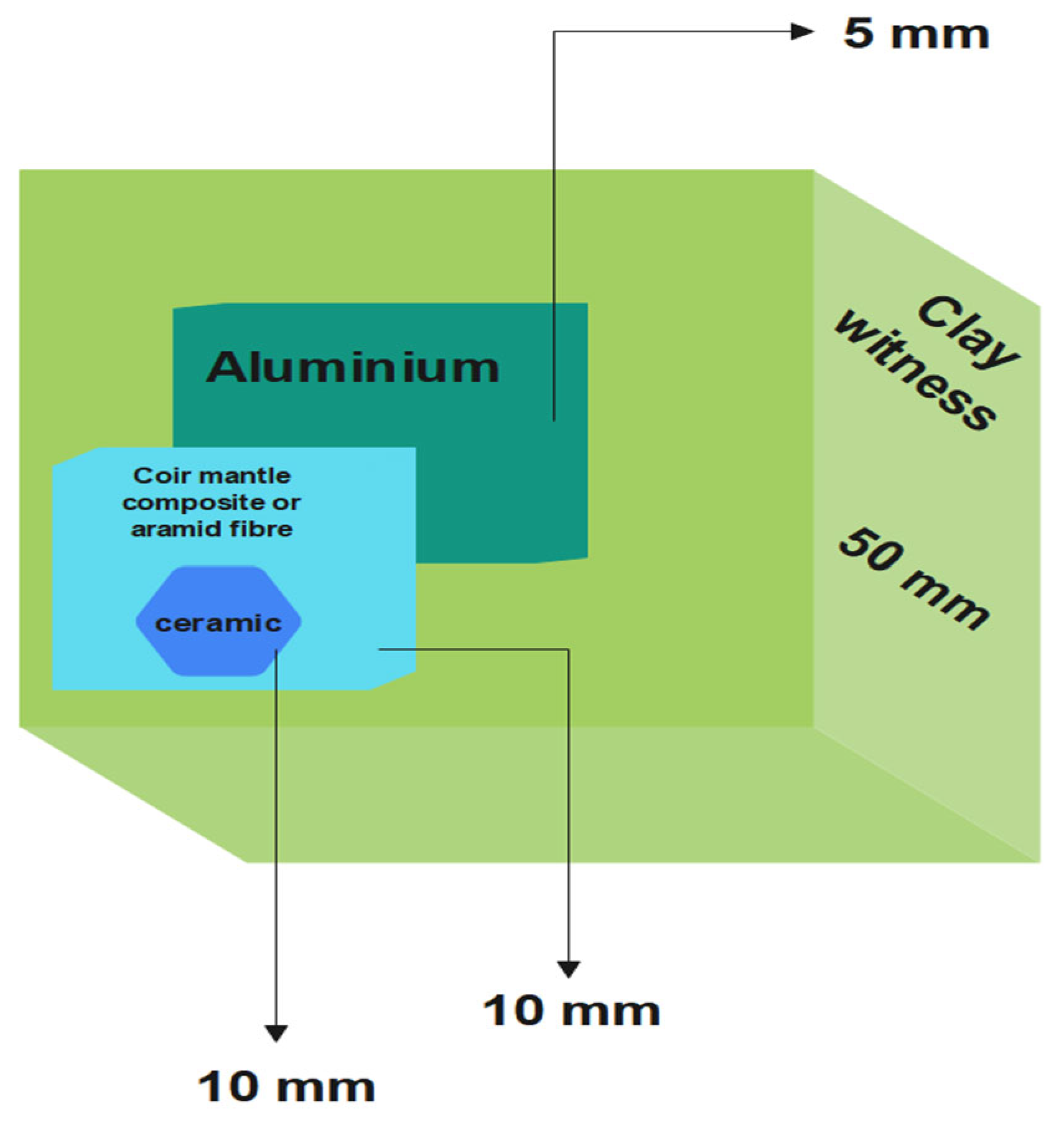

2.11. Printed Titanium Structures

2.12. Kevlar/Polyurea Composites and Shear Thickening Fluids (STF)

2.13. Natural Fibres

3. Conclusions

- 1)

- The inclusion of graphene in between Kevlar improves the strength of the vest.

- 2)

- By adding nano cellulose, thickening fluids, and rubber, the performance of natural rubber can be increased.

- 3)

- Chemically treating kenaf fibre to create composite results in the weakening of threads, but it still absorbs significant impact energy.

- 4)

- By adding rubber to Kevlar, you increase the composite’s impact resistance and ductile behaviour.

- 5)

- Laminate systems can only be used where there is less risk; hence, they are only used in lightweight bulletproof vests.

- 6)

- Cordura was more durable, whereas ballistic nylon had the highest value in abrasion resistance.

- 7)

- STF composites were 17 % lighter and thinner than Kevlar.

- 8)

- Natural fibres were the most cost-effective among all the materials.

4. Future Perspectives

- 1)

- New ultra-strong polymer nanotube materials are necessary for bulletproof vests to make them cost-efficient. It will require large quantities of CNTs (carbon nanotubes).

- 2)

- The kenaf X-ray film hybrid composites still showed some impact resistance, but we can improve the results by increasing the interfacial bond between the two.

- Materials.

- 3)

- A practical experiment with bulletproof vest inserts containing titanium structures is necessary, as most of the experiments conducted by researchers and scientists are simulations.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Ethical Approval

Consent to Participate

Consent to Publish

Authors Contribution

Availability of data and materials

References

- Aharonian, C., N. Tessier-Doyen, P. M. Geffroy, and C. Pagnoux. 2021. “Elaboration and Mechanical Properties of Monolithic and Multilayer Mullite-Alumina Based Composites Devoted to Ballistic Applications.” Ceramics International 47(3):3826–32. [CrossRef]

- Akella, Kiran. 2020. “Multilayered Ceramic-Composites for Armour Applications.” Pp. 403–33 in Handbook of Advanced Ceramics and Composites. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Albert, James S., Ana C. Carnaval, Suzette G. A. Flantua, Lúcia G. Lohmann, Camila C. Ribas, Douglas Riff, Juan D. Carrillo, Ying Fan, Jorge J. P. Figueiredo, Juan M. Guayasamin, Carina Hoorn, Gustavo H. de Melo, Nathália Nascimento, Carlos A. Quesada, Carmen Ulloa Ulloa, Pedro Val, Julia Arieira, Andrea C. Encalada, and Carlos A. Nobre. 2023. “Human Impacts Outpace Natural Processes in the Amazon.” Science 379(6630). [CrossRef]

- Ali, Mohamed Ehab, and Alf Lamprecht. 2013. “Polyethylene Glycol as an Alternative Polymer Solvent for Nanoparticle Preparation.” International Journal of Pharmaceutics 456(1):135–42. [CrossRef]

- Anggoro, Didi Dwi, and Nunung Kristiana. 2015a. “Combination of Natural Fiber Boehmeria Nivea (Ramie) with Matrix Epoxide for Bullet Proof Vest Body Armor.” P. 040002 in.

- Anggoro, Didi Dwi, and Nunung Kristiana. 2015b. “Combination of Natural Fiber Boehmeria Nivea (Ramie) with Matrix Epoxide for Bullet Proof Vest Body Armor.” P. 040002 in.

- Ashok, R. B., C. V. Srinivasa, and B. Basavaraju. 2019. “Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Composites—a Review.” Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2(4):586–607. [CrossRef]

- Asyraf, M. Z., M. J. Suriani, C. M. Ruzaidi, A. Khalina, R. A. Ilyas, M. R. M. Asyraf, A. Syamsir, Ashraf Azmi, and Abdullah Mohamed. 2022. “Development of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites Ballistic Helmet Using Concurrent Engineering Approach: A Brief Review.” Sustainability 14(12):7092. [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A. M. R., M. T. H. Sultan, M. Jawaid, and A. F. M. Nor. 2019. “A Newly Developed Bulletproof Vest Using Kenaf–X-Ray Film Hybrid Composites.” Pp. 157–69 in Mechanical and Physical Testing of Biocomposites, Fibre-Reinforced Composites and Hybrid Composites. Elsevier.

- Azmi, Ahmad M. R., Mohamed T. H. Sultan, Mohammad Jawaid, Abd R. A. Talib, and Ariff F. M. Nor. n.d. Tensile and Flexural Properties of a Newly Developed Bulletproof Vest Using a Kenaf/X-Ray Film Hybrid Composite.

- Bhat, Aayush, J. Naveen, M. Jawaid, M. N. F. Norrrahim, Ahmad Rashedi, and A. Khan. 2021. “Advancement in Fiber Reinforced Polymer, Metal Alloys and Multi-Layered Armour Systems for Ballistic Applications – A Review.” Journal of Materials Research and Technology 15:1300–1317. [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, Kadir, and Md Syduzzaman. 2022. “Protective Textiles in Defence and Ballistic Protective Clothing.” Pp. 689–749 in Protective Textiles from Natural Resources. Elsevier.

- Byrne, Michele T., and Yurii K. Gun’ko. 2010. “Recent Advances in Research on Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites.” Advanced Materials 22(15):1672–88. [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro P.V. 2011. “Soft Body Armor: An Overview of Materials, Manufacturing, Testing, and Ballistic Impact Dynamics.” Defense Technical Information Center.

- Chang, Chang-Pin, Cheng-Hung Shih, Jhu-Lin You, Meng-Jey Youh, Yih-Ming Liu, and Ming-Der Ger. 2021. “Preparation and Ballistic Performance of a Multi-Layer Armor System Composed of Kevlar/Polyurea Composites and Shear Thickening Fluid (STF)-Filled Paper Honeycomb Panels.” Polymers 13(18):3080. [CrossRef]

- Crouch, Ian G. 2019. “Body Armour – New Materials, New Systems.” Defence Technology 15(3):241–53. [CrossRef]

- Davis, Dan M. 2012. “Finite Element Modeling of Ballistic Impact on a Glass Fiber Composite Armor.” California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, California.

- Dresch, Alexander B., Janio Venturini, Sabrina Arcaro, Oscar R. K. Montedo, and Carlos P. Bergmann. 2021. “Ballistic Ceramics and Analysis of Their Mechanical Properties for Armour Applications: A Review.” Ceramics International 47(7):8743–61. [CrossRef]

- Ellis. L R. 1996. “BALLISTIC IMPACT RESISTANCE OF GRAPHITE EPOXY COMPOSITES WITH SHAPE MEMORY ALLOY AND EXTENDED CHAIN POLYETHYLENE SPECTRATM HYBRID COMPONENTS.” Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia.

- Fayed, A. I. H., Y. A. Abo El Amaim, and Doaa H. Elgohary. 2021. “Enhancing the Performance of Cordura and Ballistic Nylon Using Polyurethane Treatment for Outer Shell of Bulletproof Vest.” Journal of King Saud University - Engineering Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Fayed, A. I. H., Y. A. Abo El Amaim, Ossama Ramy, and Doaa H. Elgohary. 2023. “Assessment of the Mechanical Properties of Different Textile Materials Used for Outer Shell of Bulletproof Vest: Woven Fabrics for Military Applications.” Research Journal of Textile and Apparel 27(1):1–18. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, EASK, SN Niles, AN Morrison, P. Pranavan, IU Godakanda, and MM Mubarak. 2015. “Design of a Bullet-Proof Vest Using Shear Thickening Fluid.” International Journal of Advanced Scientific and Technical Research 434–44.

- Hu, Jinlian, Yong Zhu, Huahua Huang, and Jing Lu. 2012. “Recent Advances in Shape–Memory Polymers: Structure, Mechanism, Functionality, Modeling and Applications.” Progress in Polymer Science 37(12):1720–63. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N. 2016. “Bulletproof Vest and Its Improvement – A Review.” International Journal of Scientific Development and Research 34–39.

- Kumaravel, S., and A. Venkatachalam. 2014. “Development of Nylon, Glass/Wool Blended Fabric for Protective Application.” Journal of Polymer and Textile Engineering 5–9.

- Kushwaha, O. S., C. Ver Avadhani, N. S. Tomer, and R. P. Singh. 2014. “Accelerated Degradation Study of Highly Resistant Polymer Membranes for Energy and Environment Applications.” Advances in Chemical Science 19–30.

- Kushwaha, Omkar S., C. V. Avadhani, and R. P. Singh. 2015a. “Preparation and Characterization of Self-Photostabilizing UV-Durable Bionanocomposite Membranes for Outdoor Applications.” Carbohydrate Polymers 123:164–73. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, Omkar S., C. V. Avadhani, and R. P. Singh. 2015b. “Preparation and Characterization of Self-Photostabilizing UV-Durable Bionanocomposite Membranes for Outdoor Applications.” Carbohydrate Polymers 123:164–73. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Young S., E. D. Wetzel, and N. J. Wagner. 2003. “The Ballistic Impact Characteristics of Kevlar® Woven Fabrics Impregnated with a Colloidal Shear Thickening Fluid.” Journal of Materials Science 38(13):2825–33. [CrossRef]

- Lonkar, Sunil P., Omkar S. Kushwaha, Andreas Leuteritz, Gert Heinrich, and R. P. Singh. 2012. “Self Photostabilizing UV-Durable MWCNT/Polymer Nanocomposites.” RSC Advances 2(32):12255. [CrossRef]

- Luz, Fernanda Santos da, Edio Pereira Lima Junior, Luis Henrique Leme Louro, and Sergio Neves Monteiro. 2015. “Ballistic Test of Multilayered Armor with Intermediate Epoxy Composite Reinforced with Jute Fabric.” Materials Research 18(suppl 2):170–77. [CrossRef]

- Luz, Fernanda Santos da, Sergio Neves Monteiro, Eduardo Sousa Lima, and Édio Pereira Lima Júnior. 2017. “Ballistic Application of Coir Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composite in Multilayered Armor.” Materials Research 20(suppl 2):23–28. [CrossRef]

- Matveev, V. S., G. A. Budnitskii, G. P. Mashinskaya, L. B. Aleksandrova, and N. M. Sklyarov. 1997. “Structural and Mechanical Characteristics of Aramid Fibres for Bullet-Proof Vests.” Fibre Chemistry 29(6):381–84. [CrossRef]

- Medvedovski, Eugene. 2010. “Ballistic Performance of Armour Ceramics: Influence of Design and Structure. Part 1.” Ceramics International 36(7):2103–15. [CrossRef]

- Mylvaganam, Kausala, and L. C. Zhang. 2007. “Ballistic Resistance Capacity of Carbon Nanotubes.” Nanotechnology 18(47):475701. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Lucio Fabio Cassiano, Luane Isquerdo Ferreira Holanda, Luis Henrique Leme Louro, Sergio Neves Monteiro, Alaelson Vieira Gomes, and Édio Pereira Lima. 2017. “Natural Mallow Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composite for Ballistic Armor Against Class III-A Ammunition.” Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 48(10):4425–31. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, Lucio Fabio Cassiano, Sergio Neves Monteiro, Luis Henrique Leme Louro, Fernanda Santos da Luz, Jheison Lopes dos Santos, Fábio de Oliveira Braga, and Rubens Lincoln Santana Blazutti Marçal. 2018. “Charpy Impact Test of Epoxy Composites Reinforced with Untreated and Mercerized Mallow Fibers.” Journal of Materials Research and Technology 7(4):520–27. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Thuy-Tien N., George Meek, John Breeze, and Spyros D. Masouros. 2020. “Gelatine Backing Affects the Performance of Single-Layer Ballistic-Resistant Materials Against Blast Fragments.” Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8. [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N. M., M. R. M. Asyraf, A. Khalina, N. Abdullah, H. A. Aisyah, S. Ayu Rafiqah, F. A. Sabaruddin, S. H. Kamarudin, M. N. F. Norrrahim, R. A. Ilyas, and S. M. Sapuan. 2021. “A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite for Bullet Proof and Ballistic Applications.” Polymers 13(4):646. [CrossRef]

- Nyanor, Peter, Atef S. Hamada, and Mohsen Abdel-Naeim Hassan. 2018. “Ballistic Impact Simulation of Proposed Bullet Proof Vest Made of TWIP Steel, Water and Polymer Sandwich Composite Using FE-SPH Coupled Technique.” Key Engineering Materials 786:302–13. [CrossRef]

- Obradović, V., D. B. Stojanović, I. Živković, V. Radojević, P. S. Uskoković, and R. Aleksić. 2015. “Dynamic Mechanical and Impact Properties of Composites Reinforced with Carbon Nanotubes.” Fibers and Polymers 16(1):138–45. [CrossRef]

- Odesanya, Kazeem Olabisi, Roslina Ahmad, Mohammad Jawaid, Sedat Bingol, Ganiyat Olusola Adebayo, and Yew Hoong Wong. 2021. “Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composite for Ballistic Applications: A Review.” Journal of Polymers and the Environment 29(12):3795–3812. [CrossRef]

- Oleiwi, J. K., and Q. A. Hamad. 2018. “Studying the Mechanical Properties of Denture Base Materials Fabricated from Polymer Composite Materials.” Al-Khwarizmi Engineering Journal 100–111.

- P. Singh, R., and O. S. Kushwaha. 2017. “Progress Towards Efficiency of Polymer Solar Cells.” Advanced Materials Letters 8(1):2–7. [CrossRef]

- Parimala, H. V., and K. Vijayan. 1993. “Effect of Thermal Exposure on the Tensile Properties of Kevlar Fibres.” Journal of Materials Science Letters 12(2). [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Paulo Henrique Fernandes, Morsyleide de Freitas Rosa, Maria Odila Hilário Cioffi, Kelly Cristina Coelho de Carvalho Benini, Andressa Cecília Milanese, Herman Jacobus Cornelis Voorwald, and Daniela Regina Mulinari. 2015. “Vegetal Fibers in Polymeric Composites: A Review.” Polímeros 25(1):9–22. [CrossRef]

- Pourhashem, Sepideh, Farhad Saba, Jizhou Duan, Alimorad Rashidi, Fang Guan, Elham Garmroudi Nezhad, and Baorong Hou. 2020. “Polymer/Inorganic Nanocomposite Coatings with Superior Corrosion Protection Performance: A Review.” Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 88:29–57. [CrossRef]

- R, Seshagiri, Vinod Vivian G, and Anne Miriam Alexander. 2015. “Bullet Proof Vest Using Non-Newtonian Fluid.” International Journal of Students’ Research in Technology & Management 3(8):451–54. [CrossRef]

- Radif, Z. S., A. Ali, and K. Abdan. 2011. “Development of a Green Combat Armour from Rame-Kevlar-Polyester Composite.” Pertanika J. Sci. Technol 339–48.

- Raji, Marya, Nadia Zari, Abou el kacem Qaiss, and Rachid Bouhfid. 2019. “Chemical Preparation and Functionalization Techniques of Graphene and Graphene Oxide.” Pp. 1–20 in Functionalized Graphene Nanocomposites and their Derivatives. Elsevier.

- Risby, M. S., S. V. Wong, A. M. S. Hamouda, A. R. Khairul, and M. Elsadig. 2008. “Ballistic Performance of Coconut Shell Powder/Twaron Fabric against Non-Armour Piercing Projectiles.” Defence Science Journal 58(2):248–63. [CrossRef]

- Roy Choudhury, A. K., P. K. Majumdar, and C. Datta. 2011. “Factors Affecting Comfort: Human Physiology and the Role of Clothing.” Pp. 3–60 in Improving Comfort in Clothing. Elsevier.

- S. Kushwaha, Omkar, C. V. Avadhani, and R. P. Singh. 2013. “Photo-Oxidative Degradation Of Polybenzimidazole Derivative Membrane.” Advanced Materials Letters 4(10):762–68. [CrossRef]

- S. Kushwaha, Omkar, C. V. Avadhani, and R. P. Singh. 2014. “Effect Of UV Rays On Degradation And Stability Of High Performance Polymer Membranes.” Advanced Materials Letters 5(5):272–79. [CrossRef]

- Salman, Suhad D., and Zulkiflle B. Leman. 2018. “Physical, Mechanical and Ballistic Properties of Kenaf Fiber Reinforced Poly Vinyl Butyral and Its Hybrid Composites.” Pp. 249–63 in Natural Fibre Reinforced Vinyl Ester and Vinyl Polymer Composites. Elsevier.

- Silveira, Pedro Henrique Poubel Mendonça da, Thuane Teixeira da Silva, Matheus Pereira Ribeiro, Paulo Roberto Rodrigues de Jesus, Pedro Craveiro Rodrigues dos Santos Credmann, and Alaelson Vieira Gomes. 2021. “A Brief Review of Alumina, Silicon Carbide and Boron Carbide Ceramic Materials for Ballistic Applications.” Academia Letters. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P., and O. S. Kushwaha. 2013. “International Council of Materials Education.” Journal of Materials Education 79–119.

- Sliwinski, Michal, Wojciech Kucharczyk, and Robert Guminski. 2018. “Overview of Polymer Laminates Applicable to Elements of Light-Weight Ballistic Shields of Special Purpose Transport Means.” Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces 189(3):228–43. [CrossRef]

- Steinke, K. 2022. “Nanomaterial-Based Surface Modifications for Improved Ballistic and Structural Performance of Ballistic Materials.” Doctoral Dissertation.

- Stopforth, Riaan, and Sarp Adali. 2019. “Experimental Study of Bullet-Proofing Capabilities of Kevlar, of Different Weights and Number of Layers, with 9 mm Projectiles.” Defence Technology 15(2):186–92. [CrossRef]

- Stopforth, Riaan, and Sarp Adali. 2020. “Experimental Investigation of the Bullet-Proof Properties of Different Kevlar, Comparing.22 Inch with 9 Mm Projectiles.” Current Materials Science 13(1):26–38. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H. 2006. “Finite Element Modeling of Ballistic Penetration into Fabric Armor.” Doctoral Dissertation, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

- Vidya, Laxman Mandal, Balram Verma, and Piyush K. Patel. 2020. “Review on Polymer Nanocomposite for Ballistic & Aerospace Applications.” Materials Today: Proceedings 26:3161–66. [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S., R. Surendran, T. Sekar, and B. Rajeswari. 2021. “Ballistic Impact Analysis of Graphene Nanosheets Reinforced Kevlar-29.” Materials Today: Proceedings 45:788–93. [CrossRef]

- Walley, S. M. 2014. “An Introduction to the Properties of Silica Glass in Ballistic Applications.” Strain 50(6):470–500. [CrossRef]

- Wambua, Paul, Bart Vangrimde, Stepan Lomov, and Ignaas Verpoest. 2007. “The Response of Natural Fibre Composites to Ballistic Impact by Fragment Simulating Projectiles.” Composite Structures 77(2):232–40. [CrossRef]

- Zochowski, Pawel, Marcin Bajkowski, Roman Grygoruk, Mariusz Magier, Wojciech Burian, Dariusz Pyka, Miroslaw Bocian, and Krzysztof Jamroziak. 2021. “Ballistic Impact Resistance of Bulletproof Vest Inserts Containing Printed Titanium Structures.” Metals 11(2):225. [CrossRef]

- Zochowski, Pawel, Marcin Cegła, Krzysztof Szczurowski, Jędrzej Mączak, Marcin Bajkowski, Ewa Bednarczyk, Roman Grygoruk, Mariusz Magier, Dariusz Pyka, Mirosław Bocian, Krzysztof Jamroziak, Roman Gieleta, and Piotr Prasuła. 2023. “Experimental and Numerical Study on Failure Mechanisms of the 7.62 × 25 Mm FMJ Projectile and Hyperelastic Target Material during Ballistic Impact.” Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).