1. Introduction

Widespread climate change has worsened the frequency and extent of drought conditions which are the cause for the reduction in agricultural productivity worldwide [

1]. Limited rainfall and high temperatures often occur during key plant growing stages, exacerbating water supply issues in many agricultural regions, where irrigation resources are frequently insufficient. This is the reason why optimizing water use through improved irrigation strategies has become essential to mitigate the effects of prolonged drought periods [

2].

Plants primarily suffer drought stress when subjected to prolonged low soil moisture, triggering many physiological and biochemical responses aimed at reducing oxidative damage and preserving vital functions [

3,

4]. Water scarcity reduces plant water use efficiency, mainly by inducing stomatal closure to limit transpiration and prevent water loss, thereby altering photosynthetic efficiency and carbon metabolism, leading to a reduction in overall plant biomass [

5]. Imbalances related to photosynthesis cause a downregulation of photosystem II (PSII), resulting in an accumulation of unused electrons that are converted into reactive oxygen species (ROS), potentially damaging cellular structures [

6]. Furthermore, drought stress speed up pigment degradation, especially chlorophyll [

5], while other pigments such as carotenoids and antioxidants – including phenolic compounds and flavonoids – act as non-enzymatic defence mechanisms to cope with oxidative stress and enhance plant stress tolerance [

7,

8].

These alterations – which occur in all plants – are particularly significant when they impact horticultural crops such as tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum L.), which is one of the most economically important vegetables cultivated around the world [

9]. The growing demand for fresh and processed tomatoes in recent decades is driven by consumer interest in high-quality products with enhanced organoleptic and functional properties beneficial to human health [

10]. Together with quality considerations, an increased concern is also related to the environmental consequences of crops cultivation, especially regarding water consumption. This is the reason for implementing efficient water supply for the growth, flowering and fruit set of tomato plants, which is essential as it impacts biomass accumulation, leaf expansion, transpiration and photosynthesis. As a matter of fact, scarce water availability can alter the architecture of roots and nutrient uptake impairing transport of essential macro- and micronutrients to fruit tissues as well [

11]. Furthermore, water shortage reduces cell growth and water content in fruit, thus reducing their size and weight, putting them at risk for physiological disorders such as blossom-end rot [

12]. Conversely, fruit firmness can be enhanced by lower water content because it has a direct relation with increased dry matter accumulation and tissue density that influences the mechanical resistance of the fruit. Drought affects fruit composition by altering photosynthetic activity, sugar metabolism, and carbohydrate translocation, frequently resulting in increased concentration of sugars including glucose, fructose, and sucrose - which act as osmolytes - due to decreased water content of the fruit, enhancing sweetness, flavour, and promoting increased total soluble solids (TSS), a critical quality trait in tomato [

13,

14]. Aside from sugar accumulation, drought stress may also enhance the accumulation of antioxidant secondary metabolites including polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoid pigments such as lycopene. These compounds have a protective role against oxidative stress by stabilizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants and are also recognized for their health-promoting effects in human nutrition [

13,

14].

Considering the necessity to balance water-use efficiency, yield, and fruit quality, sustainable alternatives such as biostimulants have gained attention for their potential to promote plant tolerance to drought stress. Among biostimulants, vegetal-derived protein hydrolysates (V-PHs) have been shown to be beneficial in enhancing crop performance, especially in suboptimal growing conditions, thanks to the bioactive peptides and amino acids which are made of [

15]. When applied to plants, these compounds trigger many molecular and physiological responses under water stress conditions. For example, in a tomato experiment [

16], a plant-derived protein hydrolysate improved water status and pollen viability under drought conditions, resulting in higher yields compared to untreated plants. Furthermore, V-PH modulated antioxidants in both leaves and fruits, depending on the irrigation level used. Agliassa et al. [

17] found that applying a V-PH to

Capsicum annum L., which belongs to Solanaceae family, resulted in faster drought recovery, increased antioxidants, and a higher relative growth rate and fruit yield. Nevertheless, the efficacy of V-PHs in enhancing drought tolerance can vary in function of drought severity and duration. In a short-term experiment on tomato, the application of a Malvaceae-derived PH resulted in faster recovery after multiple water stress events, while the plant biomass, even if not significantly affected, showed a tendency to higher accumulation under stress conditions when the V-PH was applied [

18]. However, such findings must be validated in long-term experiments because the ultimate target is tomato production, and under prolonged severe drought, the damage to plant metabolism and structure may be beyond a recovery point through biostimulants, resulting in significant yield loss. In terms of application method, a short-term experiment considering only the vegetative phase of tomato plants demonstrated that root drenching was more effective than foliar spraying for PHs treatments under water stress conditions [

19]. However, the optimal timing and method of application – whether foliar spray or root drench – requires further investigation, particularly in the context of long-term experiments. These knowledge gaps need to be addressed for developing targeted recommendations that can maximize the benefits of biostimulants in commercial tomato production.

Given its demonstrated efficacy in a short-term experiment on tomato under water stress [

18], a Malvaceae-derived protein hydrolysate (PH) was considered for this long-term study. Taking these aspects into consideration, this study aimed to assess the effect of the PH applied through foliar application or soil drenching on tomato plants grown under optimal and sub-optimal water availability conditions. The main interest was to characterize any positive effects from the biostimulant application on the yield and fruit quality for understanding how the PH and its mode of application influences plant resilience, growth, productivity and if it would influence the plant’s capacity to cope and perform under water stress.

3. Discussion

In the current trial, irrigation was the most important factor influencing plant biomass accumulation, both in terms of vegetal biomass and fruit production, with stressed plants producing lower dry weights of leaves, stems, fruits, and total above-ground biomass than stressed plants. Overall, the decrease in dry weight across all parameters in stressed plants confirmed that the plant growth was strongly dependent on adequate water supply. Furthermore, there was no significant difference between the biomass accumulation of the plants treated with the protein hydrolysate (PH), applied either foliarly (PH-F) or as root drench (PH-R), and the untreated control (U), suggesting that water stress impaired severely plant metabolism limiting the PH-mediated stress mitigation activity. Similarly, Patanè et al. [

20] demonstrated a significant drop of total dry biomass in tomato plants (-56.3%) when a severe water deficit was imposed from early development stages, as in the current experiment, whereas the results obtained with a 50% reduced water rate from early stages or from flowering were comparable to 100% watered plants. These findings were also reflected in fruit yields.

Tomato yield showed a similar trend of plant biomass accumulation, clearly supporting the dominant effect of irrigation level on crop growth and productivity. All yield parameters were significantly reduced under water stress conditions, with an approximate 70% decrease in both marketable yield and total yield, indicating the importance of adequate water supply for fruit growth and development. The halving of the number of marketable fruits indicated a limited fruit set; additionally, while the average fruit weight decreased moderately, this was consistent with the observed improvement in fruit size and, as a result, higher fruit marketability under well-watered conditions. The protein hydrolysate (PH) used in this experiment was selected based on a previous study that demonstrated its efficacy in promoting recovery from water stress in a short-term trial on tomato [

18]. Additionally, other studies have shown that biostimulant products derived from vegetal sources can help plants to mitigate the negative effects of drought. For example, protein hydrolysate-based biostimulants improved tomato yield under limited water availability (50% irrigation compared to 100% irrigation) [

16], and seaweed extract from

Ascophyllum nodosum applied at 50% irrigation also enhanced tomato crop performance (higher yields when compared to untreated plants) under reduced water conditions [

21]. However, in the present experiment the expected improvements in tomato yield were not observed. This outcome could be attributed to the intensity of the water stress applied, which likely exceeded the PH’s capacity to enhance plant resilience under such severe conditions, despite the well-established potential of plant protein hydrolysates to improve water stress tolerance. [

18,

22,

23]. Undeniably, under extreme drought conditions, plant functions like photosynthesis and transpiration may be seriously hindered [

24], consequently affecting the plant’s ability to respond to biostimulants signals or properly uptake the bioactive compounds and distribute them for an effective use.

The dynamics of chlorophyll content measured non-destructively throughout the tomato crop cycle provided valuable insight into the physiological responses to both water availability and biostimulant treatments. At 20 days after transplanting (DAT), the significant interaction between irrigation and PH treatments had limited physiological relevance, as the effects of only two PH applications can be considered minimal. The higher chlorophyll content in watered plants treated with PH-R at this stage may have simply reflected initial variability rather than a meaningful biostimulant impact. At 55 DAT, stressed plants had higher chlorophyll levels than watered plants, which could be attributed to a compensatory response or to higher concentration in smaller leaves, as demonstrated by Rosa et al. [

25], who used a handheld spectroradiometer to observe changes in tomato leaf reflectance related to chlorophyll during water scarcity. PH-F-treated stressed plants showed encouraging results, suggesting that the PH-F may have started enhancing stress tolerance mechanisms at a time when water stress had not yet imposed irreversible damage to the photosynthetic system, helping to preserve chlorophyll and reduce oxidative degradation. By the end of the trial (133 DAT), the shift to lower chlorophyll content in PH-R treated plants under stress in comparison with PH-F – which resulted in the highest chlorophyll content – suggests that foliar-applied PH may have initially supported photosynthetic pigment maintenance, but was ultimately unable to prevent stress-induced damage as drought became more severe and prolonged, in favor of a slightly better response in plant treated with root drench. Destructive measurements of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids in samples harvested at the mid-crop cycle validated non-destructive measurements made during the same period. Pigments increased significantly in water-stressed plants [

26] possibly due to their higher concentrations compared to watered and more developed plants. Furthermore, among biostimulants, PH-R significantly increased levels of chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll, whereas PH-F showed lower chlorophyll content under stress, closer to levels found in watered plants. This could indicate that PH-F treated plants had a less pronounced stress response and better stress mitigation. Nevertheless, these moderate differences in chlorophyll dynamics did not translate into significant improvements in biomass accumulation or yield, further supporting that under severe and extended water stress, neither application method of PH provided a strong enough protective effect to maintain productivity.

In terms of fruit quality traits, fruits grown under water stress exhibited higher °Brix values (8.83), suggesting greater soluble sugar content due to the reduced water uptake and smaller fruit size, which typically results in enhanced fruit sweetness and flavor. Similarly, the increase in titratable acidity (4.78 vs 4.59 g L⁻¹ citric acid) in stressed fruits likely corresponded to a greater presence of organic acids, which, combined with the higher °Brix, can further improve the taste of the fruits. The lower pH in stressed fruits (4.29 vs. 4.32) was also consistent with the higher acidity, implying a higher concentration of acidic metabolites. Dry matter content, which was significantly higher under drought (9.72% vs. 9.30%), indicates a higher proportion of solids in relation to water, often associated with improved nutritional value and extended shelf life. Firmness, which is critical for transportation and shelf-life, was also higher in drought-stressed fruits (1.09 N vs. 0.95 N), likely due to reduced cell expansion and water content, which increase tissue density and resistance to deformation. These results are consistent with many studies on tomatoes, where improved quality characteristics were observed when subjected to water shortage [

12,

27,

28]. Fruit diameter observed an isolated increase for PH-R treated plants, suggesting a potential transient benefit of root drenching. However, this effect was not sustained across trusses. The lack of significant interaction between irrigation and PH treatments supports that PH applications were not sufficient to modify fruit quality outcomes under the imposed stress conditions. Overall, while drought stress reduced fruit size, it enhanced several quality traits such as sugar content, acidity, and firmness—parameters that are particularly relevant for cherry tomato market value and consumer preferences.

On the other hand, drought stress negatively affected the nutrient composition of tomato fruits, particularly potassium (K), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), which were all significantly reduced under limited water availability, potentially impacting the nutritional value of tomato fruits as source of micronutrients for human diet [

29]. This decline could be attributed to the constant low soil moisture during the crop cycle and reduced transpiration rates that may have impaired nutrient mobility and root structure and uptake, as well as compromised internal transport within the plant and to the fruits. For example, Mitchell et al. [

30] discovered that tomato fruit K levels were significantly reduced in response to soil water deficit, affecting sugar balance in sink organs rather than net carbon accumulation, while reduced Mn, Zn, and Cu concentrations may relate more to lower yields in stressed plants that likely influenced their fruit concentrations as well [

31]. This micronutrient imbalance towards lower values may have affected Fe concentration [

32], which was significantly increased by the application of PH-F in comparison with untreated or root-drenched plants (PH-R). This suggest that while water deficit can disrupt the assimilation of many essential nutrients, specific biostimulant strategies (e.g. molecular signalling) may have bypassed root-related limitations, promoting direct Fe assimilation or remobilization by the leaves and old tissues, facilitating systemic translocation to developing fruits, which function as plant sink.

The results demonstrated that drought stress significantly enhanced the antioxidant potential of tomato fruits, particularly as measured by FRAP, polyphenol, and flavonoid content. The increased FRAP values in stressed plants suggest an up-regulation of antioxidant defence mechanisms in response to oxidative stress caused by limited water availability. FRAP was also significantly stimulated in plants treated with PH-F, indicating that foliar application may have further increased antioxidant capacity, possibly by promoting the synthesis of non-enzymatic antioxidants or enhancing redox homeostasis [

16]. The increase in total polyphenols and flavonoids in fruits from stressed plants is in line with the higher FRAP values and reflects a typical biochemical response to the water deficit [

14]. These secondary metabolites are directly involved in tomato fruit nutritional and functional quality, thereby their enhancement under water stress suggests that, despite a yield reduction, fruit quality in terms of antioxidants richness can be improved.

The carbohydrate profile of tomato fruits under water stress revealed a metabolic adjustment for enhancing osmotic regulation and stress tolerance. The higher accumulation of glucose and fructose in comparison with sucrose content suggests an active conversion of sucrose in its constituents (glucose and fructose) through enzymatic processes, with a crucial role in maintaining fruit cellular turgor and protecting cells from dehydration [

33]. In particular, when observing the interaction between irrigation and PH, PH-R under stress recorded the higher values of glucose, suggesting that root drenching may further stimulate sugar metabolism, potentially influencing the expression of carbohydrate-related enzymes and enhancing the adaptive response under stress. Although fructose was not significantly affected by treatments or their combination with irrigation levels, it stayed the predominant sugar, supporting the typical sweetness profile of cherry tomato. Still, the increased levels of glucose and fructose under drought conditions may have enhanced the organoleptic quality of tomato fruits, despite the decreased yield observed in this experiment; this also indicates an adaptive response that supports the production of health-promoting antioxidants, thereby positively affecting overall fruit quality.

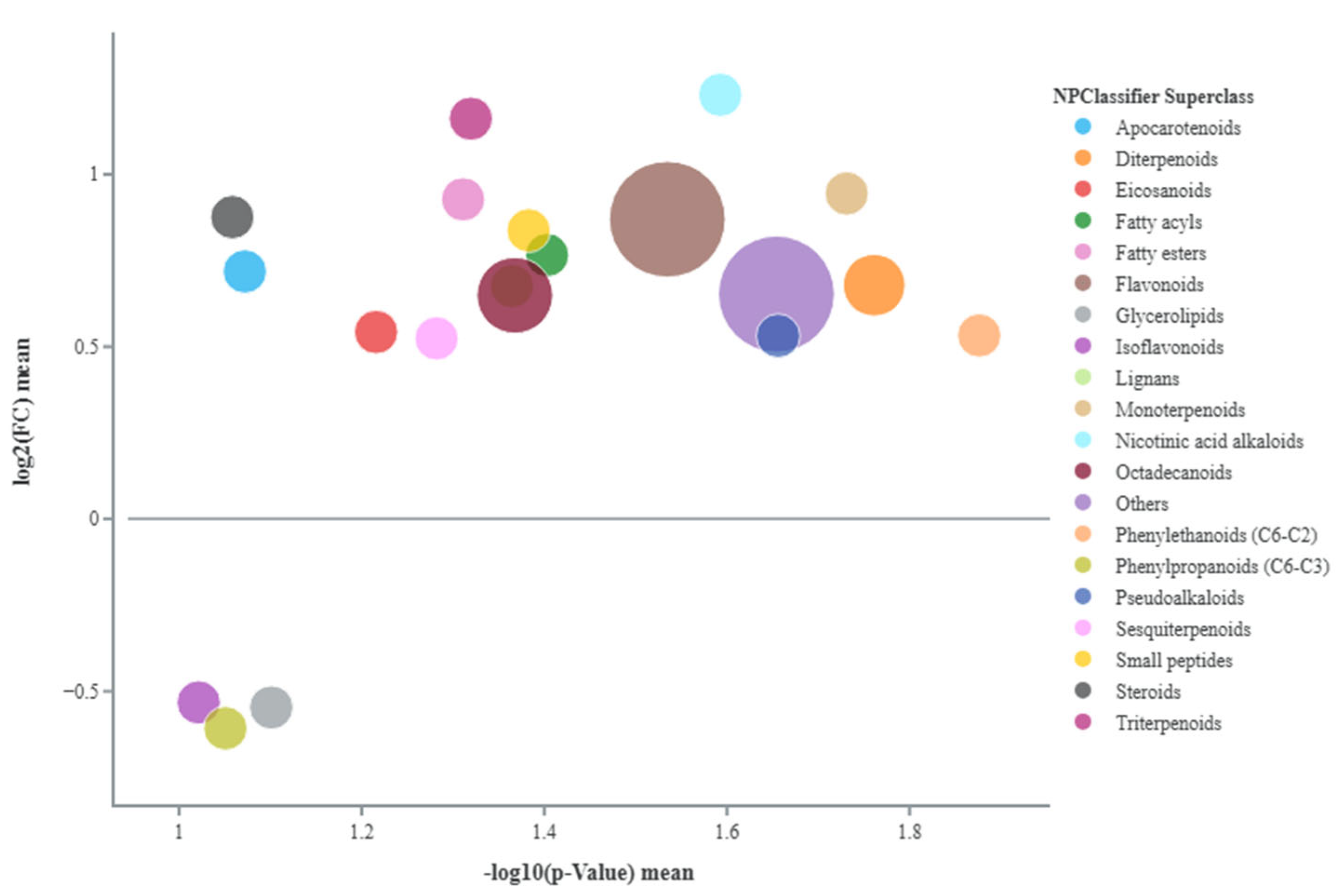

In terms of metabolic profiling, the comparison of untreated stressed fruits and well-watered fruits revealed the accumulation of key metabolite classes in the plant's adaptive response to drought and fruit quality. For instance, the increased levels of amino acids in stressed fruits suggest the activation of osmotic adjustments, reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification, and nitrogen storage, aiding to maintain the integrity of proteins and membranes during dehydration, while also serving as signalling molecules [

34,

35]. Among amino acids, proline notably increased, likely playing a role in stabilizing cell membranes and proteins, while also functioning as an antioxidant and signalling molecule that offers additional defence against water loss [

36]. L-2,3-dihydrodipicolinate was found to participates in lysine biosynthesis, which is another compound directly involved in plant stress response and development [

37]. L-arginine, one of the most versatile amino acids, was probably involved in maintaining fruit cell functions [

38] or acted as a precursor of compounds such as polyamines, which actively contribute in fruit development and ripening by indirectly affecting firmness, sugar metabolism, and antioxidant capacity [

39]. Notably, whereas anthocyanins such as cyanidin 3-O-(6-O-β-D-glucosyl-2-O-β-D-xylosyl-β-D-galactoside) may play a role in mechanisms of stress tolerance [

40], apocarotenoids like 5,6-epoxy-3-hydroxy-β-ionone and β-D-glucopyranosyl abscisate are more closely associated with the flavor and aroma of tomato fruits, in addition to acting as signal molecules in stress responses [

41,

42]. The physiological function of phlorizin, classified as a dihydrochalcone, remains not completely understood; however, it is acknowledged for its positive impact on human health [

43]. Interestingly, the increase in butein could be linked not only to higher cuticular wax production, which improves fruit protection, but also because as flavonoid-related compound may represent a beneficial phytochemical substance [

44]. Upregulation of dihydromyricetin (a dihydroflavonol), hesperetin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, and naringin (flavonones) may indicate wider flavonoid pathway activation. 1-O-feruloylglucose and 1-O-cinnamoylglucose are glycoside derivatives of ferulic and cinnamic acids, and as part of the larger class of polyphenols [

45] –together with flavonoids derivatives – further corroborate the nutritional value of tomato fruits, which may resulted improved under water deficit [

46]. Other compounds possibly contributing to tomato fruit quality included serotonin, acknowledged as a beneficial compound for human health and found to accumulate particularly in fresh tomatoes [

47]; vitamin C, which was also reported to increase under water stress by Conti et al. [

48], is known for its beneficial role in human nutrition, while phenethylamine and 2-phenylethyl β-D-glucopyranoside play a key role in flavor volatile synthesis [

49]. Conversely, the reduction of 2,3-dioctanoylglycerylceramide, a type of wax monoester, might just be linked to a transition to alternative protective mechanisms in the fruits. Some gibberellins (A23 and A34) were found to be increased, even though their reduction is usually associated with a rapid response to water stress [

50], and it could be associated to the regulation of fruit ripening [

51] and homeostasis with methylated forms (methyl gibberellin A9), which are known to play a direct role in stress tolerance [

52], along with jasmonic acid [

53]. In summary, all these metabolites highlight the potential of taking advantage from water stress to improve nutritional and organoleptic traits of tomato fruits. However, the lack of significant differences in the metabolite profiles of tomato fruits treated with PH – regardless of the application method – and untreated plants both under well-watered and stressful conditions, suggest that the PH treatments did not induce measurable metabolic changes in the fruit tissue at the time of analysis. This could relate to compromised root function which altered PH-R's potential efficacy related to overall plant stress response, while PH-F may have triggered transient changes in the plant that were not able to be captured at the fruit maturity stage. Overall, these data indicate that while PHs may change plant metabolism, the direct effects on tomato fruit biochemistry were limited under the present experimental conditions. This result reinforces the notion that sampling time and stress intensity are important factors to consider when trying to interpret the application of biostimulants, including potential changes in metabolomic analysis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

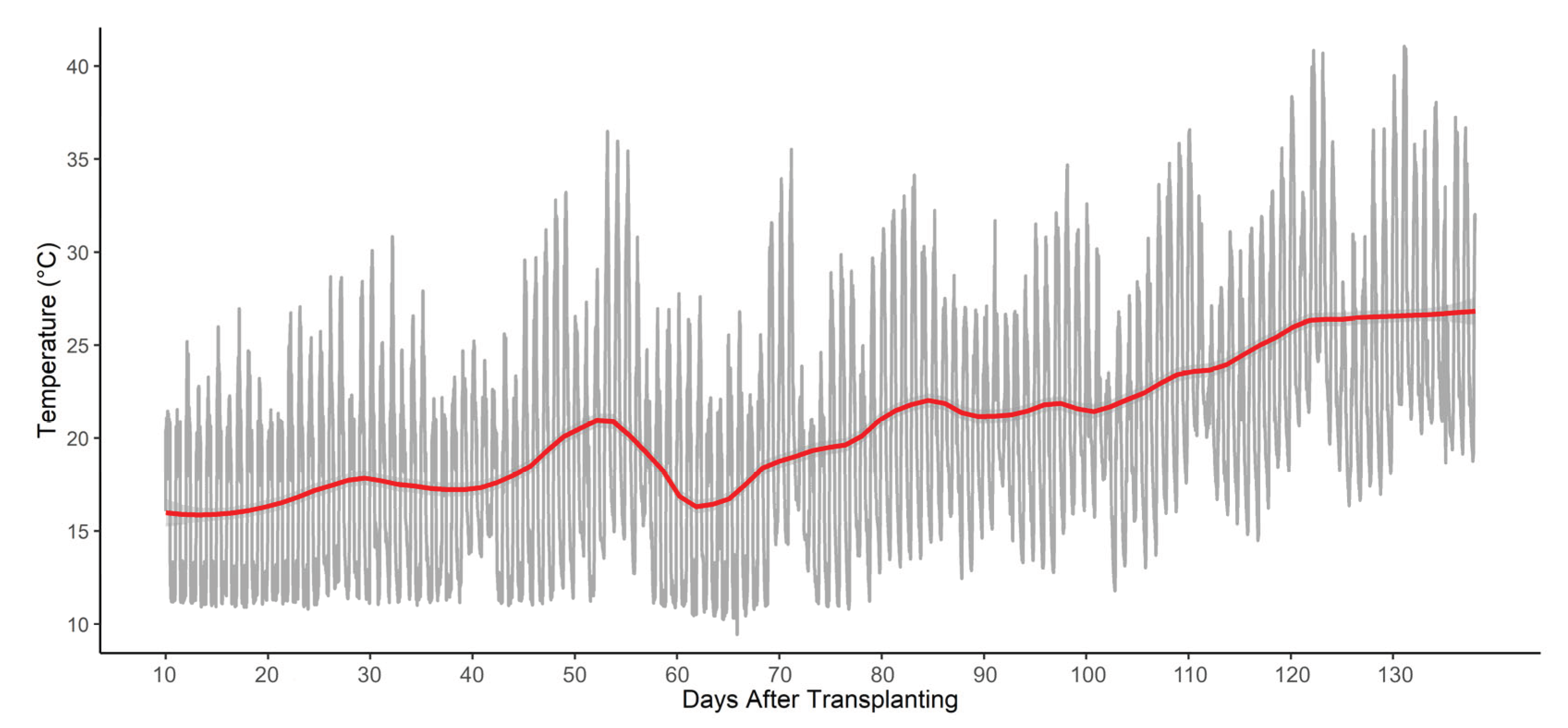

The experiment took place in a polymethyl greenhouse at the University of Tuscia's Experimental Farm (Viterbo, Italy, 42° 25' N; 12° 08' E; 310 m a.s.l.) from February 20 to July 5, 2024. During the first month, a heating system was used to keep the temperature above 20°C at night, reducing cold stress after transplantation, while a ventilation system and side openings were automatically activated to regulate the daily air temperature when it exceeded 27° C. A sensor from Toro Company (Tempus Air MS, Bloomington, Minnesota, United States) recorded temperature trends throughout the trial, as show in the

Figure 2.

Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum L. - cv Pralyna, SAIS Sementi, Cesena, Italy) have been sown in trays (170 holes/tray) filled with a commercial substrate containing primarily peat moss (Brill, Georgsdorf, Germany) and grown in a glass greenhouse at 25°C with regular watering until the second true leaf reached full expansion. After one week, the seedlings were fertigated with NPK (20% N - 8.8% P - 16.6% K) at a rate of 1 g L-1. When the plants had two fully expanded leaves, they were transplanted into 9-liter pots filled with sandy loam soil (70% sand, 30% soil). Ninety-six plants were distributed using a randomized complete block design, with 8 replicates per treatment, and were pruned at the eighth truss stage. The pots were arranged in double rows, two for the stressed sector and two for the well-watered sector, with a plant density of 3.5 plant/m².

Water soil sensors (Tempus Air MS, Toro Company, Bloomington, Minnesota, United States) were placed in pots corresponding to each irrigation sector and connected to a remote platform. The substrate's water content reading ranged from 50-80% in the well-watered sector and 30-50% in the water-stressed sector. Probe reading of 80% corresponded to water container capacity whereas 30% probe reading to the temporary wilting point.

The nutrient solution (EC of 2.0 dS m-1 and a pH of 6.0), supplied through a drip irrigation system with 4 L h-1 emitters and managed through the sensors system, consisted of: N-NO3 (10 mM), P (1m M), S (1.25 mM), K (3.5 mM), Ca (3.5 mM), Mg (1.0 mM), Fe (17.1 μM), Mn (17.4 μM), Zn (3.7 μM), B (11 μM), Cu (1.9 μM), Mo (0.5 μM).

4.2. Biostimulant Application

A Malvaceae-derived protein hydrolysate (PH) was applied to plants either foliarly (PH-F) or at the root level (PH-R), and it was compared to an untreated control in both well-irrigated and stressed sectors, for a total of six treatments. The PH contained 16.9% carbon and 4.67% nitrogen as free amino acids and peptides, as reported in the aminogram by El-Nakhel et al. [

54]. Regarding foliar applications, PH was applied by uniformly spraying leaves or drenching the soil with a diluted solution at a dose of 3 ml L

-1, whereas the control treatment was sprayed with distilled water or manually supplied in the pots. Treatments were given every 10 days starting 20 days after transplanting (DAT) and continuing until the end of the trial.

4.3. Fruit Yields and Harvest

Tomato fruits were harvested on all plants between May 27 (97 DAT) and July 3 (134 DAT) due to scalar ripening of the tomato trusses. The yield was measured as total yield, marketable yield, number and average weight of marketable fruits, and not marketable yield (rot and underdeveloped fruits). At the end of the trial, the harvested fresh biomass (leaves and stems) was recorded and oven-dried at 65°C until it reached a constant weight for dry biomass measurement.

4.4. Leaf Non-Destructive and Destructive Pigments Measurements

Throughout the crop cycle, chlorophyll was non-destructively measured using a multi-pigment meter (MPM-100, ADC BioScientific Ltd, United Kingdom), which has an integrated clip that emits a flashing light to record pigment values as absolute units.

At mid-crop cycle and immediately before pruning (86 DAT), the fourth leaf from 8 plants per treatment was sampled, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C to determine total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids as described by Wellburn [

55]. 0.1g of frozen leaf samples were extracted in acetone 80% (1:200 p/v) and homogenised using a homogenizer (IKA T10 basic UltraTurrax, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany). The extracts were centrifuged at 4800 g for 20 min. A spectrophotometer (Helios β, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, United States) measured the absorbance solution at 663, 647, and 470 nm to determine the concentration of chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids expressed as mg g-1 of fresh weight (FW). Total chlorophyll was calculated as the sum of chlorophyll a and b.

4.5. Fruit Quality Assessment

Subsamples of marketable fruits of the fourth truss were selected from each treatment to evaluate fruit quality parameters. Fruit firmness was measured on the equatorial zone of three fruits per plant (8 plants/treatment) using an automatic force transducer set to 3N for tomato fruits (Instron, Pianezza, Torino, Italy), obtaining values expressed as newtons (N). On the same fruits, dry matter (DM) content was determined by oven-drying the samples at 65 °C until constant weight. Centrifuged and filtered subsamples were used for the determination of the soluble solid content (°Brix), pH and titratable acidity (TA). °Brix were assessed on the filtered juice using a digital refractometer (Atago N1, Atago Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The pH was measured with a digital pH-meter (HI-9023, Hanna Instruments, Padova, Italy), then the juice was titrated with Stadtman et al.’s method [

56] using 0.1 N NaOH to reach pH 8.1.

4.6. Fruit Nutrient Content

Dried fruits samples of the third truss were used for the total nitrogen determination according to Kjeldahl method [

57]. 0.25 g of each treatment replicate was digested in 10 mL of 96% sulfuric acid adding Kjeldahl catalyst tablet in Pyrex tubes. The digestion was carried out for 30 minutes at 420°C in a digestor (DK6 Velp Scientifica, Usmate Velate, Italy). The distillation was then performed using the Kjeltec 2100 (Foss Analytics), adding 50 mL of 40% NaOH. Titration was conducted with 0.1N HCl, using methyl red + bromocresol green as indicator, and the titration volume was used to calculate the nitrogen percentage, which was then converted to g kg

-1 of dry weight (DW). Dried samples were also used for the elemental analysis process. Six replicates from each treatment were placed in tubes along with 65% HNO

3 and MilliQ water, then digested for 40 minutes (Multiwave GO Plus, Anton Paar GmbH, Rivoli, Torino, Italy). Following digestion, the samples were thinned with 1% HNO

3 and examined using an atomic emission spectrometer (4210 MP-AES, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) connected with SPS 4 Autosampler (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States). A standard sample was always prepared as a reference for the elemental analysis.

4.7. Fruit Antioxidants

Subsamples of tomato fruits were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C to determine antioxidant activity through Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), polyphenols and flavonoids assessment. The antioxidant capacity through FRAP and DPPH assays was evaluated through spectrophotometric measurements (Helios β, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, United States) extracting 0.5 g of fresh tomato samples with 5 mL of 80% methanol homogenizing with UltraTurrax (IKA T10 basic UltraTurrax, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany).

The FRAP determination [

58] was adapted and consisted in the incubation of 30 μL of tomato extract with 900 μL of FRAP working solution (0.3 M acetate buffer pH 3.6, 10mM 2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) in 40 mM HCl, 20 mM FeCl

3 in distilled water) at 37°C for 30 minutes. The samples’ absorbance was read at a wavelength of 593 nm based on the reduction of the ferric salt (Fe

3+-TPTZ (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine)) to ferrous (Fe

2+-TPTZ) under acidic conditions. The DPPH determination [

59] consisted in the incubation of 100 μL of extract with 800 μL of 75 mM DPPH (15 mg in 50ml 80% methanol) at room temperature for 30 minutes, and reading the extracts’ absorbance at 517 nm. For both methods the antioxidant activity was expressed as mg Trolox equivalents (TE) g

−1 FW.

The extraction for polyphenols and flavonoids was carried out on 0.5g each sample in 80% ethanol for spectrophotometric measurements. Polyphenols method ([

60] with modifications) involved the incubation of 200 μL of extract with 1 mL Folin and Ciocalteau’s reagent (1:5), 800 μL of 7.5% Na

2CO

3 at room temperature for 1h. The absorbance was recorded at 765 nm. For flavonoids quantification [

61], 700 μL of extract were mixed with 150 μL of 5% NaNO

2, 150 μL of 10% AlCl

3 and 1 mL of 1M NaOH. Samples were centrifuged due to the formation of colloids in suspension. The supernatant was read at 510 nm. In the case of polyphenols and flavonoids the results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) g

-1 FW and mg of quercetin equivalents (QE) g

-1 FW, respectively.

Lycopene determination was performed as described by Adsule and Dan [

62] with modifications on 8 mg of freeze-dried samples of each treatment ground with mortar and pestle and mixed with 2 mL 100% acetone. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes, centrifuged and diluted at 1:5, then their absorbance was read at 505 nm with a spectrophotometer (Beckman DU-50 UV-visible; Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Lycopene molar extinction coefficient was used to calculate samples’ lycopene content expressed as mg 100 g−1 FW.

4.8. Fruit Carbohydrates Composition

Non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) were measured using 10 mg of freeze-dried powder extracted in 50% ethanol maintained at 80 °C for 45 minutes under continuous shaking. After centrifugation, soluble sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) were recovered in the supernatant, and starch remained in the pellet. The pellet was washed four times with 50 mM Na acetate buffer (pH 4.5), suspended and autoclaved at 120 °C for 45 minutes in 1 mL of the same buffer. Samples were then incubated at 50 °C for 1 h with amyloglucosidase (70 U) and α-amylase (4U) to hydrolyze the starch to glucose. A spectrophotometric coupled enzymatic assay measured the glucose produced by starch hydrolysis. The supernatant containing soluble sugars was filtered through a nylon 0.2 µm PPII syringe filter (Whatman Inc., Maidstone, UK), then analyzed through high-performance anion exchange chromatography, with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD), using an ICS-6000 with a dual eluent generator cartridge (EGC) module and an analytical CarboPac™ PA200 IC column for Dual EGC Mode (all equipment was ThermoFisher Scientific Dionex™, Waltham, MA, USA). Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were quantified against a carbohydrate standard curve prepared using HPLC-grade reagents (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany).

4.9. Fruit Metabolomics

Subsamples of tomato fruits at the third truss stage were frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at -80°C for metabolomics analysis. After homogenising with UltraTurrax (IKA T25, IKA-Werke GmbH & Co. KG, Staufen, Germany), 250 mg of each treatment's samples were extracted in acidified 80% methanol for metabolites suspension, centrifuged, and filtered through a 0.22 μm cellulose membrane into vials for analysis. Untargeted metabolomic analysis and metabolite identification in sample extracts were carried out at oloBion Laboratory (Barcelona, Spain) using an ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph (UHPLC) coupled to a quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometer (UHPLC/QTOF-MS) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, United States) according with the procedure described by Bonini et al. [

63]. The detected compounds were identified and classified using the PlantCyc 16.0.2 database (Plant Metabolic Network, Michigan State University).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc test were per-formed with R packages (RStudio Team, Wien, Austria) to assess the significance of the effects and interactions between irrigation and biostimulant treatments.

Metabolic data was processed using oloMAP 2.02 developed at the oloBion Com-pany [

63].

Author Contributions

M.L.: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. M.C.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. P.B.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology. S.P.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation. S.M.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation. G.C.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Figure 1.

Metabolites classes identified through chemical enrichment in the comparison between untreated stressed and watered tomato fruits. The figure displays the log2(FC) mean and the -log10(p-value) mean of the metabolites grouped by class. Each dot's size represents the sum of the fold change (FC) of the class. A log2(FC) mean greater than 0 indicates up-regulation of the class, while a value lower than 0 indicates down-regulation. Moving to the right on the x-axis, the -log10(p-value) mean corresponds to a higher significance in metabolite changes.

Figure 1.

Metabolites classes identified through chemical enrichment in the comparison between untreated stressed and watered tomato fruits. The figure displays the log2(FC) mean and the -log10(p-value) mean of the metabolites grouped by class. Each dot's size represents the sum of the fold change (FC) of the class. A log2(FC) mean greater than 0 indicates up-regulation of the class, while a value lower than 0 indicates down-regulation. Moving to the right on the x-axis, the -log10(p-value) mean corresponds to a higher significance in metabolite changes.

Figure 2.

Temperature (°C) mesaured during the crop cycle. The grey line represents the raw temperature readings, while the red line illustrates a smoothed trend calculated as LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) by using local regression on the daily temperature recordings.

Figure 2.

Temperature (°C) mesaured during the crop cycle. The grey line represents the raw temperature readings, while the red line illustrates a smoothed trend calculated as LOESS (Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing) by using local regression on the daily temperature recordings.

Table 1.

Yield indicators (g/plant: marketable, not-marketable fruits and total yield; number and weight of marketable fruits) of tomato plants in response to irrigation and biostimulant treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 1.

Yield indicators (g/plant: marketable, not-marketable fruits and total yield; number and weight of marketable fruits) of tomato plants in response to irrigation and biostimulant treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

Yield (g/plant) |

Marketable fruits |

| Marketable |

Not marketable |

Total |

Number (n./plant) |

Mean weight (g/fruit) |

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

|

| W |

2484.32 ± 40.49 |

528.60 ± 22.26 |

3012.35 ± 51.37 |

152.98 ± 2.65 |

16.41 ± 0.16 |

| S |

1471.79 ± 23.49 |

368.83 ± 11.18 |

1798.64 ± 23.32 |

103.98 ± 1.49 |

14.39 ± 0.13 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

2078.02 ± 121.57 |

434.48 ± 19.60 |

2454.01 ± 124.56 |

131.83 ± 6.00 |

15.41 ± 0.24 |

| PH-F |

1971.25 ± 94.03 |

462.10 ± 27.88 |

2345.24 ± 106.5 |

129.41 ± 4.57 |

15.25 ± 0.23 |

| PH-R |

1915.33 ± 97.02 |

447.02 ± 29.24 |

2436.41 ± 133.11 |

125.06 ± 4.95 |

15.55 ± 0.30 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

2614.52 ± 66.40 |

471.52 ± 29.99 |

3031.71 ± 86.46 |

157.94 ± 5.40 |

16.49 ± 0.20 |

| W*PH-F |

2420.29 ± 71.90 |

567.67 ± 38.49 |

2932.55 ± 49.57 |

150.75 ± 4.44 |

16.09 ± 0.28 |

| W*PH-R |

2427.31 ± 62.47 |

547.81 ± 44.61 |

3062.80 ± 113.39 |

150.07 ± 3.66 |

16.64 ± 0.33 |

| S*U |

1452.11 ± 23.46 |

397.44 ± 22.47 |

1793.79 ± 37.98 |

102.00 ± 2.34 |

14.40 ± 0.20 |

| S*PH-F |

1492.28 ± 38.69 |

356.53 ± 15.70 |

1831.35 ± 39.04 |

108.06 ± 2.39 |

14.30 ± 0.11 |

| S*PH-R |

1467.34 ± 49.93 |

352.54 ± 18.48 |

1768.27 ± 44.58 |

101.63 ± 2.76 |

14.45 ± 0.33 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

Table 2.

Leaf pigment concentration for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids content in tomato leaves sampled at mid-crop cycle. DAT = days after transplanting; W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 2.

Leaf pigment concentration for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll, and carotenoids content in tomato leaves sampled at mid-crop cycle. DAT = days after transplanting; W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

Pigment concentration (mg/g FW) |

| Clorophyll a |

Clorophyll b |

Total Chlorophyll |

Carotenoids |

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

| W |

1.188 ± 0.013 |

0.450 ± 0.004 |

1.637 ± 0.017 |

0.333 ± 0.004 |

| S |

1.359 ± 0.021 |

0.500 ± 0.005 |

1.858 ± 0.027 |

0.365 ± 0.005 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

| U |

1.285 ± 0.022 ab |

0.479 ± 0.006 ab |

1.764 ± 0.027 ab |

0.351 ± 0.005 |

| PH-F |

1.227 ± 0.017 b |

0.462 ± 0.005 b |

1.688 ± 0.022 b |

0.341 ± 0.005 |

| PH-R |

1.305 ± 0.030 a |

0.483 ± 0.008 a |

1.788 ± 0.039 a |

0.355 ± 0.007 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

1.232 ± 0.023 bc |

0.463 ± 0.007 |

1.695 ± 0.030 bc |

0.342 ± 0.006 |

| W*PH-F |

1.151 ± 0.019 c |

0.438 ± 0.005 |

1.589 ± 0.023 c |

0.325 ± 0.006 |

| W*PH-R |

1.181 ± 0.023 c |

0.447 ± 0.007 |

1.628 ± 0.030 c |

0.332 ± 0.006 |

| S*U |

1.337 ± 0.034 ab |

0.494 ± 0.009 |

1.831 ± 0.043 ab |

0.359 ± 0.007 |

| S*PH-F |

1.306 ± 0.022b |

0.486 ± 0.006 |

1.790 ± 0.028 b |

0.357 ± 0.006 |

| S*PH-R |

1.430 ± 0.046 a |

0.518 ± 0.013 |

1.948 ± 0.059 a |

0.378 ± 0.010 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

*** |

*** |

*** |

*** |

| Biostimulant |

* |

* |

* |

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

* |

ns |

* |

ns |

Table 3.

Quality parameters (Total soluble solids - TSS, pH, titratable acidity - TA, dry matter – DM, and firmness) of marketable fruits measured at the IV truss in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, *, **, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 3.

Quality parameters (Total soluble solids - TSS, pH, titratable acidity - TA, dry matter – DM, and firmness) of marketable fruits measured at the IV truss in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. Ns, *, **, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, 0.01 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

TSS

(°Brix)

|

pH |

TA

(g/l citric acid)

|

DM

(%)

|

Firmness

(N)

|

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

|

| W |

8.55 ± 0.05 |

4.32 ± 0.01 |

4.59 ± 0.06 |

9.30 ± 0.08 |

0.95 ± 0.02 |

| S |

8.83 ± 0.04 |

4.29 ± 0.01 |

4.78 ± 0.08 |

9.72 ± 0.07 |

1.09 ± 0.02 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

8.65 ± 0.06 |

4.31 ± 0.01 |

4.61 ± 0.09 |

9.49 ± 0.08 |

1.02 ± 0.02 |

| PH-F |

8.76 ± 0.06 |

4.30 ± 0.01 |

4.78 ± 0.08 |

9.54 ± 0.10 |

1.00 ± 0.03 |

| PH-R |

8.66 ± 0.07 |

4.32 ± 0.01 |

4.66 ± 0.08 |

9.38 ± 0.12 |

1.02 ± 0.03 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

8.49 ± 0.11 |

4.34 ± 0.02 |

4.56 ± 0.13 |

9.37 ± 0.10 |

0.99 ± 0.04 |

| W*PH-F |

8.58 ± 0.07 |

4.31 ± 0.02 |

4.54 ± 0.08 |

9.39 ± 0.14 |

0.91 ± 0.04 |

| W*PH-R |

8.58 ± 0.09 |

4.33 ± 0.01 |

4.67 ± 0.09 |

9.14 ± 0.16 |

0.95 ± 0.02 |

| S*U |

8.79 ± 0.05 |

4.27 ± 0.02 |

4.65 ± 0.13 |

9.64 ± 0.13 |

1.05 ± 0.02 |

| S*PH-F |

8.94 ± 0.08 |

4.29 ± 0.02 |

5.02 ± 0.11 |

9.78 ± 0.07 |

1.12 ± 0.02 |

| S*PH-R |

8.77 ± 0.09 |

4.30 ± 0.02 |

4.66 ± 0.14 |

9.76 ± 0.13 |

1.09 ± 0.04 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

*** |

* |

* |

*** |

*** |

| Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

Table 4.

Concentrations of macronutrients (N, P, K; g/kg fruit dry weight - DW) and micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu; mg/kg DW) in tomato fruits in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 4.

Concentrations of macronutrients (N, P, K; g/kg fruit dry weight - DW) and micronutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn, Cu; mg/kg DW) in tomato fruits in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

Macronutrient concentration (g/kg DW) |

|

Micronutrient concentration (mg/kg DW) |

| N |

P |

K |

|

Fe |

Mn |

Zn |

Cu |

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| W |

21.85 ± 0.32 |

7.86 ± 0.43 |

50.64 ± 0.86 |

|

304.53 ± 10.53 |

62.74 ± 2.61 |

25.44 ± 0.83 |

5.63 ± 0.15 |

| S |

21.62 ± 0.30 |

6.85 ± 0.63 |

40.75 ± 1.26 |

|

280.66 ± 18.75 |

42.81 ± 1.45 |

18.17 ± 0.51 |

5.07 ± 0.16 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

21.49 ± 0.36 |

8.03 ± 0.64 |

43.93 ± 1.90 |

|

250.01 ± 14.36 b |

52.77 ± 3.84 |

21.93 ± 1.61 |

5.52 ± 0.24 |

| PH-F |

21.86 ± 0.44 |

7.21 ± 0.76 |

47.59 ± 2.17 |

|

325.85 ± 13.38 a |

57.71 ± 4.82 |

22.21 ± 1.49 |

5.23 ± 0.27 |

| PH-R |

21.85 ± 0.34 |

6.68 ± 0.65 |

44.98 ± 1.97 |

|

303.05 ± 19.52 ab |

51.57 ± 3.84 |

21.63 ± 1.17 |

5.25 ± 0.11 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

21.82 ± 0.59 |

8.15 ± 0.76 |

49.55 ± 1.38 |

|

266.78 ± 14.98 |

61.95 ± 4.38 |

25.15 ± 2.21 |

6.02 ± 0.13 |

| W*PH-F |

21.48 ± 0.63 |

7.83 ± 0.88 |

52.90 ± 0.48 |

|

314.57 ± 16.91 |

64.59 ± 5.20 |

25.99 ± 1.02 |

5.52 ± 0.36 |

| W*PH-R |

22.14 ± 0.56 |

7.48 ± 0.49 |

49.67 ± 1.81 |

|

325.95 ± 14.82 |

61.69 ± 4.73 |

25.19 ± 1.03 |

5.46 ± 0.09 |

| S*U |

21.15 ± 0.41 |

7.90 ± 1.09 |

39.25 ± 1.51 |

|

236.03 ± 22.81 |

43.60 ± 3.49 |

18.07 ± 0.26 |

5.19 ± 0.33 |

| S*PH-F |

22.15 ± 0.67 |

6.47 ± 1.32 |

42.28 ± 2.61 |

|

342.77 ± 21.66 |

43.95 ± 1.21 |

17.67 ± 1.09 |

4.90 ± 0.38 |

| S*PH-R |

21.57 ± 0.42 |

6.22 ± 0.96 |

40.95 ± 2.48 |

|

283.41 ± 33.44 |

41.46 ± 1.23 |

18.59 ± 1.00 |

5.10 ± 0.17 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

ns |

ns |

*** |

|

ns |

*** |

*** |

* |

| Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

* |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

Table 5.

Antioxidant capacity of tomato fruits tissues expressed as Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) in mg Trolox equivalents/g fruit fresh weight – FW, total polyphenols as mg gallic acid equivalents – GAE/g FW, and flavonoids as mg quercetin equivalents – QE/g FW. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 5.

Antioxidant capacity of tomato fruits tissues expressed as Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) in mg Trolox equivalents/g fruit fresh weight – FW, total polyphenols as mg gallic acid equivalents – GAE/g FW, and flavonoids as mg quercetin equivalents – QE/g FW. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, ***, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05 or 0.001. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

mg Trolox eq./g FW |

mg GAE eq./g FW |

mg QE eq./g FW |

| FRAP |

DPPH |

Polyphenols |

Flavonoids |

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

| W |

22.106 ± 0.593 |

11.742 ± 0.077 |

31.576 ± 0.646 |

0.252 ± 0.016 |

| S |

25.935 ± 0.437 |

11.519 ± 0.109 |

33.817 ± 0.657 |

0.304 ± 0.016 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

| U |

22.293 ± 0.582 b |

11.657 ± 0.128 |

32.141 ± 0.921 |

0.254 ± 0.021 |

| PH-F |

26.034 ± 0.891 a |

11.699 ± 0.136 |

32.844 ± 0.785 |

0.278 ± 0.025 |

| PH-R |

23.706 ± 0.496 b |

11.516 ± 0.072 |

33.104 ± 0.897 |

0.311 ± 0.011 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

19.622 ± 0.414 |

11.797 ± 0.116 |

30.864 ± 1.184 |

0.247 ± 0.039 |

| W*PH-F |

23.779 ± 1.304 |

11.753 ± 0.173 |

31.701 ± 1.014 |

0.243 ± 0.026 |

| W*PH-R |

22.581 ± 0.690 |

11.662 ± 0.106 |

32.162 ± 1.294 |

0.271 ± 0.008 |

| S*U |

24.519 ± 0.406 |

11.518 ± 0.228 |

33.418 ± 1.297 |

0.261 ± 0.020 |

| S*PH-F |

28.740 ± 0.618 |

11.645 ± 0.216 |

33.987 ± 1.078 |

0.313 ± 0.040 |

| S*PH-R |

24.831 ± 0.574 |

11.371 ± 0.082 |

34.047 ± 1.229 |

0.338 ± 0.006 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

*** |

ns |

* |

* |

| Biostimulant |

*** |

ns |

ns |

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

Table 6.

Concentration of glucose, sucrose, fructose, total soluble carbohydrates (mg/g DW) in tomato fruits in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, **, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, or 0.01. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

Table 6.

Concentration of glucose, sucrose, fructose, total soluble carbohydrates (mg/g DW) in tomato fruits in response to irrigation (watered vs. stressed) and biostimulant (untreated, foliar, root) treatments. W = watered; S = stressed; U = untreated; PH-F = foliar; PH-R = root. ns, *, **, non-significant or significant at P ≤ 0.05, or 0.01. Values are presented as mean ± standard error.

| Source of variation |

Soluble carbohydrates

(mg/g DW)

|

|

Non-structural carbohydrates

(mg/g DW)

|

| Glucose |

Sucrose |

Fructose |

Total |

|

Amid |

| Irrigation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| W |

233.62 ± 12.82 |

27.22 ± 2.30 |

296.91 ± 22.13 |

557.76 ± 34.13 |

|

6.03 ± 1.40 |

| S |

271.47 ± 7.44 |

20.20 ± 2.50 |

325.04 ± 16.22 |

616.71 ± 23.37 |

|

4.88 ± 0.58 |

| Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| U |

266.25 ± 10.88 |

18.48 ± 3.68 |

312.66 ± 24.18 |

597.34 ± 35.04 |

|

4.18 ± 0.72 |

| PH-F |

233.52 ± 12.63 |

25.50 ± 2.20 |

298.60 ± 17.56 |

557.62 ± 26.98 |

|

6.26 ± 2.10 |

| PH-R |

257.87 ± 18.68 |

27.16 ± 2.86 |

321.67 ± 31.28 |

606.69 ± 49.00 |

|

5.92 ± 0.50 |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| W*U |

272.94 ± 20.66 ab |

23.74 ± 3.52 |

331.04 ± 50.30 |

627.71 ± 71.98 |

|

3.42 ± 0.07 |

| W*PH-F |

208.40 ± 12.81 c |

27.98 ± 3.58 |

291.28 ± 34.69 |

527.65 ± 49.70 |

|

8.67 ± 3.99 |

| W*PH-R |

219.53 ± 13.80 bc |

29.97 ± 5.32 |

268.41 ± 33.74 |

517.91 ± 51.34 |

|

5.10 ± 0.79 |

| S*U |

259.57 ± 10.95 abc |

13.22 ± 5.27 |

294.29 ± 7.54 |

567.08 ± 6.31 |

|

4.95 ± 1.42 |

| S*PH-F |

258.65 ± 1.48 abc |

23.03 ± 2.29 |

305.92 ± 16.87 |

587.59 ± 16.49 |

|

3.85 ± 0.61 |

| S*PH-R |

296.21 ± 9.14 a |

24.34 ± 2.19 |

374.92 ± 30.28 |

695.47 ± 38.54 |

|

5.83 ± 0.77 |

| Significance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Irrigation |

** |

* |

ns |

ns |

|

ns |

| Biostimulant |

ns |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

ns |

| Irrigation*Biostimulant |

* |

ns |

ns |

ns |

|

ns |