Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Basics

2.2. Irrigation Treatments

- CK (control): Conventional irrigation, 16 m³·mu⁻¹ per application

- T1: 50% reduction, 8 m³·mu⁻¹ per application

- T2: 25% reduction, 12 m³·mu⁻¹ per application

2.3. Measurement Indexes and Methods

2.3.1. Plant Growth and Yield

2.3.2. Fruit Quality Analysis

- Single fruit weight: Measured using a precision balance (±0.01 g).

- Fruit firmness: Measured at the shoulder, equator, and blossom end using a GY-4 digital fruit firmness tester.

- Moisture and dry weight: Five fruits per replicate were weighed fresh, oven-dried at 120 °C for 20 minutes (enzyme inactivation), then further dried at 80 °C to a constant weight. Moisture content (%) was calculated as:

-

Nutritional quality (based on Hesheng, 2004):

- o

- Soluble solids: TD-45 refractometer

- o

- Titratable acidity: Standard titration method

- o

- Vitamin C: 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol titration

- o

- Soluble sugars: Anthrone colorimetry

- o

- Lycopene: Spectrophotometry

2.3.4. VOCs Analysis

- Qualitative analysis: Conducted using the GC-MS workstation with the following parameters: initial area cut-off = 10,000; initial peak width = 0.1; shoulder peak detection = OFF; initial threshold = 5.0. Identification was based on matches from the NIST17S library.

- Quantitative analysis: n-Hexane was used as an internal standard. VOC concentrations (μg·kg⁻¹) were calculated as:

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

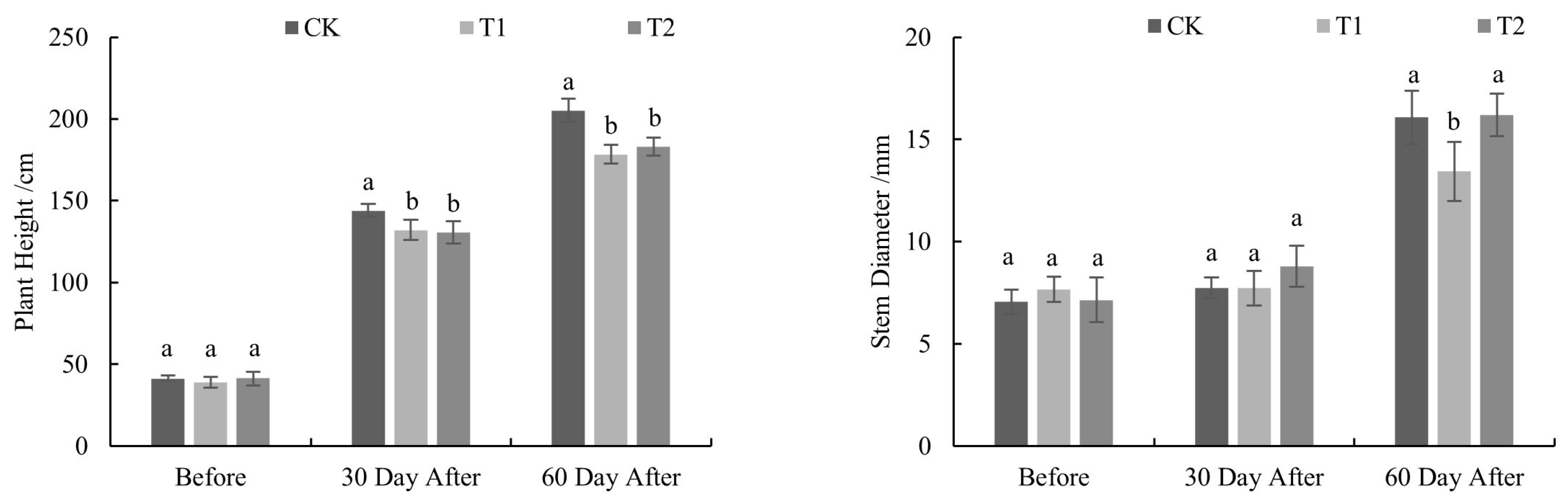

3.1. Plant Height and Stem Diameter

3.2. Fruiting Characteristics, Yield, and Fruit Cracking Rate of Tomatoes

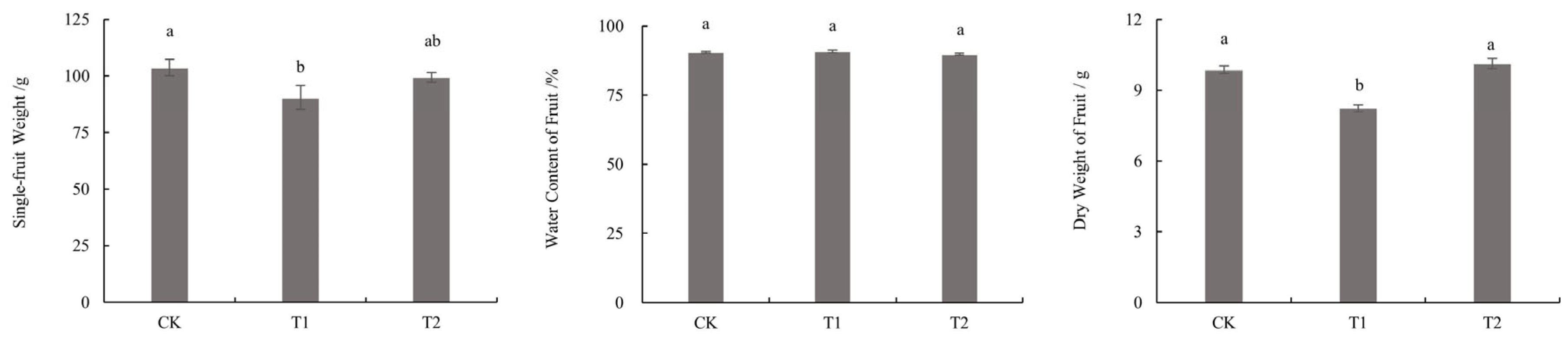

3.3. Fruit Weight, Moisture, and Dry Weight of Tomato Fruits

3.4. Hardness of Tomato Fruit

3.5. Nutritional Quality of Tomato Fruits

3.6. Volatile Organic Compounds

3.6.1. Composition and Abundance of VOCs

3.6.2. Key Aroma-Active Compounds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- A Thévenot Etienne, Aurélie Roux, Ying Xu, et al. (2015). Analysis of the Human Adult Urinary Metabolome Variations with Age, Body Mass Index, and Gender by Implementing a Comprehensive Workflow for Univariate and OPLS Statistical Analyses.. Journal of proteome research, 14(8), 3322-3335.

- Amal Ghannem, Imed Ben Aissa, & Rajouene Majdoub. (2020). Effects of regulated deficit irrigation applied at different growth stages of greenhouse grown tomato on substrate moisture, yield, fruit quality, and physiological traits.. Environmental science and pollution research international, 28(34), 46553-46564.

- Bertin Nadia, and Génard Michel. (2018). Tomato quality as influenced by preharvest factors. Scientia Horticulturae, 233(2018), 264-276.

- Brashlyanovabr B, and Ganeva G (2014). Texture quality of tomatoes as affected by different storage temperatures and growth habit. Emirates Journal of Food Agriculture, 26(9), 750-756.

- César Rodrigues Magalhães Hilton, Godoy Alves Filho Elenilson, Letícia Rivero Meza Silvia, et al. (2023). Effect of Methyl Jasmonate on the Biosynthesis of Volatile Compounds Associated with the Ripening of Grape Tomato Fruits.. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 71(11).

- Cheng Guoting, Chang Peipei, Shen Yuanbo, et al. (2020). Comparing the Flavor Characteristics of 71 Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Accessions in Central Shaanxi Frontiers in Plant Science, 11(2020), 586834-586834.

- Costa J. Miguel, Ortuño Maria F., & Chaves M. Manuela. (2007). Deficit Irrigation as a Strategy to Save Water: Physiology and Potential Application to Horticulture. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 49(10), 1421-1434.

- Cui Jintao, Shao Guangcheng, Lu1 Jia, et al. (2020). Yield, quality and drought sensitivity of tomato to water deficit during different growth stages Scientia Agricola, 77(2).

- Flavor Ingredient Library. (1999). https://www.femaflavor.org/flavor-library.

- G Deluc Laurent, R Quilici David, Alain Decendit, et al. (2009). Water deficit alters differentially metabolic pathways affecting important flavor and quality traits in grape berries of Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay.. BMC genomics, 10(1), 212.

- Gong Chengsheng, Guo Guangjun, Pan Baogui, et al. (2024). Integrating transcriptome and metabolome to explore the formation of fruit aroma in different types of pepper Food Bioscience, 62, 105157-105157.

- Hadi Muna El, Zhang Feng-Jie, Wu Fei-Fei, et al. (2013). Advances in Fruit Aroma Volatile Research Molecules, 18(7), 8200-8229.

- Hesheng Li. (2004). Guidelines for Plant Physiology Experiments. Higher Education Press.

- Jinghua Guo, Lingdi Dong, L. Kandel Shyam, et al. (2022). Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis Provides Insights into the Fruit Quality and Yield Improvement in Tomato under Soilless Substrate-Based Cultivation Agronomy, 12(4), 923-923.

- Klee Harry J, and Tieman Denise M. (2018). The genetics of fruit flavour preferences.. Nature reviews. Genetics, 19(6), 347-356.

- Klee Harry J., and Giovannoni James J.. (2011). Genetics and Control of Tomato Fruit Ripening and Quality Attributes. Annual Review of Genetics, 45(1), 41.

- Kumar P. Suresh, Singh Y., Nangare D.D., et al. (2015). Influence of growth stage specific water stress on the yield, physico-chemical quality and functional characteristics of tomato grown in shallow basaltic soils Scientia Horticulturae, 197, 261-271.

- L Rambla José, M Tikunov Yury, J Monforte Antonio, et al. (2014). The expanded tomato fruit volatile landscape.. Journal of experimental botany, 65(16), 4613-4623.

- Lahoz Inmaculada, Pérez-de-Castro Ana, Valcárcel Mercedes, et al. (2016). Effect of water deficit on the agronomical performance and quality of processing tomato Scientia Horticulturae, 200(2016), 55-65.

- Li Tong, Cui Jiaxin, Guo Wei, et al. (2023). The Influence of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizer Applications on Nitrogen Transformation and Yield in Greenhouse Tomato Cultivation with Surface and Drip Irrigation Techniques. Water, 15(20), 3546.

- Li Wenxin, Quan Jiajia, Wen Yongshuai, et al. (2024). Compost tea enhances volatile content in tomato fruits via SlERF.E4-activated SlLOX expression.. Journal of experimental botany.

- Liu Xuena, Guo Jinghua, Chen Zijing, et al. (2024). Detection of Volatile Compounds and Their Contribution to the Nutritional Quality of Chinese and Japanese Welsh Onions ( Allium fistulosumL.). Horticulturae, 10(5), 446.

- Mathilde Causse, Chloé Friguet, Clément Coiret, et al. (2010). Consumer preferences for fresh tomato at the European scale: a common segmentation on taste and firmness. Journal of food science, 75(9), S531-541.

- Nangare D.D., Singh Yogeshwar, Kumar P. Suresh, et al. (2016). Growth, fruit yield and quality of tomato ( Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) as affected by deficit irrigation regulated on phenological basis Agricultural Water Management, 171, 73-79.

- Ning Jin, Dan Zhang, Li Jin, et al. (2023). Controlling water deficiency as an abiotic stress factor to improve tomato nutritional and flavour quality. Food Chemistry: X, 19(2020), 100756-100756.

- Rivelli Anna Rita, Castronuovo Donato, Gatta Barbara La, et al. (2024). Qualitative Characteristics and Functional Properties of Cherry Tomato under Soilless Culture Depending on Rootstock Variety, Harvesting Time and Bunch Portion Foods, 13(10).

- Ruirui Li, Junwen Wang, Hong Yuan, et al. (2023). Exogenous application of ALA enhanced sugar, acid and aroma qualities in tomato fruit& Frontiers in Plant Science, 14, 1323048-1323048.

- Shewmaker Christine K., Baldwin Elizabeth A., Scott John W., et al. (2000). Flavor Trivia and Tomato Aroma: Biochemistry and Possible Mechanisms for Control of Important Aroma Components HortScience, 35(6), 1013-1022.

- Silvia Locatelli, Wilfredo Barrera, Leonardo Verdi, et al. (2024). Modelling the response of tomato on deficit irrigation under greenhouse conditions Scientia Horticulturae, 326, 112770.

- Tieman Denise, Bliss Peter, McIntyre Lauren M., et al. (2012). The Chemical Interactions Underlying Tomato Flavor Preferences Current Biology, 22(11), 1035-1039.

- Tieman Denise M., Loucas Holly M., Kim Joo Young, et al. (2007). Tomato phenylacetaldehyde reductases catalyze the last step in the synthesis of the aroma volatile 2-phenylethanol Phytochemistry, 68(21), 2660-2669.

- Tieman Denise, Zhu Guangtao, Resende Marcio F. R., et al. (2017). A chemical genetic roadmap to improved tomato flavor Science, 355(6323), 391-394.

- Wang Libin, Baldwin Elizabeth A., & Bai Jinhe. (2016). Recent Advance in Aromatic Volatile Research in Tomato Fruit: The Metabolisms and Regulations. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 9(2), 203-216.

- Wang Peiwen, Ran Siyu, Xu Yuanhang, et al. (2025). Comprehensive metabolome and transcriptome analyses shed light on the regulation of SlNF-YA3b in carotenoid biosynthesis in tomato fruit Postharvest Biology and Technology, 219, 113263-113263.

- Wu Xiaolei, Huo Ruixiao, Yuan Ding, et al. (2024). Exogenous GABA improves tomato fruit quality by contributing to regulation of the metabolism of amino acids, organic acids and sugars Scientia Horticulturae, 338, 113750-113750.

- 36. Yury Tikunov, Raana Roohanitaziani, Fien Meijer-Dekens, et al. (2020). The genetic and functional analysis of flavor in commercial tomato: the FLORAL4 gene underlies a QTL for floral aroma volatiles in tomato fruit. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology, 103(3), 1189-1204.

- Zegbe-Domı́nguez J.A, Behboudian M.H, Lang A, et al. (2003). Deficit irrigation and partial rootzone drying maintain fruit dry mass and enhance fruit quality in ‘Petopride’ processing tomato ( Lycopersicon esculentum, Mill.) Scientia Horticulturae, 98(4), 505-510.

- Zeist L.J. van Gemert. (2011). Compilations of odour threshold values in air, water and other media. Oliemans Punter & Partners BV.

- Zhang Jing, Wang Yongxu, Zhang Susu, et al. (2024). ABIOTIC STRESS GENE 1 mediates aroma volatiles accumulation by activating MdLOX1a in apple.. Horticulture research, 11(10), uhae215.

- Zhang Zhonghui, Ye Weizhen, Li Chun, et al. (2024). Volatilomics-Based Discovery of Key Volatiles Affecting Flavor Quality in Tomato. Foods, 13(6).

- Zhao Jiantao, Sauvage Christopher, Zhao Jinghua, et al. (2019). Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies provides insights into genetic control of tomato flavor. Nature Communications, 10(1).

- Zhou Xinyuan, Zheng Yanyan, Chen Jie, et al. (2025). Multivariate analysis of the effect of deficit irrigation on postharvest storability of tomato Postharvest Biology and Technology, 219, 113245-113245.

| Treatment | Number of fruitingears | Number of fruits | Yield | Split |

| pcs | g m-2 | % | ||

| CK | 6.33±2.16a | 26.67±0.67a | 5074.68±207.18a | 17.86±3.00a |

| T1 | 5.50±3.98b | 21.56±0.71b | 3195.41±210.86c | 14.74±1.50a |

| T2 | 6.00±2.98ab | 23.00±0.50b | 3727.26±121.59b | 7.67±1.50b |

| Treatment | Fruit shoulder hardness | Equatorial surface hardness | Navel hardness |

| ——————————N—————————— | |||

| CK | 10.40±0.37b | 8.77±0.24b | 9.17±0.56a |

| T1 | 12.87±0.73a | 11.03±0.40a | 8.43±0.26a |

| T2 | 12.98±0.73a | 10.47±0.29a | 7.20±0.29b |

| Treatment | Lycopene content | Vitamin C content | SolubleSolids content | SolubleSugar content | TitratableAcid content | Sugar-acidRatio |

| ———mg/100g/FW——— | —————————%/FW————————— | |||||

| CK | 3.88±0.23b | 15.69±0.04c | 7.90±0.04c | 6.65±0.01b | 0.68±0.02c | 9.77±0.05b |

| T1 | 2.97±0.07 c | 17.14±0.12b | 8.25±0.04b | 6.56±0.12b | 0.74±0.01a | 8.85±0.03c |

| T2 | 4.14±0.01 a | 22.62±0.08a | 9.05±0.01a | 7.19±0.06a | 0.72±0.01a | 9.99±0.10a |

| No. | CAS | Class I | Compounds | Aroma Description | Threshold in water,mg kg-1 | OAVa | relative content,μg kg-1 | ||

| CK | T2 | CK | T2 | ||||||

| 1 | 20125-84-2 | Alcohol | 3-Octen-1-ol, (Z)- | Dust, Toasted Nut | - b | - | - | 1125.83±48.95 | 1618.46±57.71 |

| 2 | 18409-18-2 | Alcohol | 2-Decen-1-ol, (E)- | Fruit | - | - | - | 765.87±41.57 | 1559.51±211.56 |

| 3 | 112-42-5 | Alcohol | 1-Undecanol | Mandarin | 0.700000 | 1.10 | 3.18 | 771.46±44.72 | 2227.38±86.01 |

| 4 | 104-54-1 | Alcohol | 2-Propen-1-ol, 3-phenyl- | Floral, Honey, Oil | 0.077000 | 10.82 | 14.23 | 832.92±33.67 | 1095.9±10.03 |

| 5 | 628-99-9 | Alcohol | 2-Nonanol | Cucumber | 0.058000 | 15.78 | 24.21 | 915.07±128.51 | 1403.9±27.54 |

| 6 | 100-51-6 | Alcohol | Benzyl Alcohol | Boiled Cherries, Moss, Roasted Bread, Rose | 2.546210 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 1393.78±166.62 | 1859.25±151.17 |

| 7 | 98-00-0 | Alcohol | 2-Furanmethanol | Burnt, Caramel, Cooked | 4.500500 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 1472.23±49.58 | 1690.18±50.74 |

| 8 | 1195-32-0 | Aromatics | Benzene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)- | Citrus, Pine | 0.085000 | 14.28 | 16.43 | 1213.74±38.85 | 1396.21±13.36 |

| 9 | 99-87-6 | Aromatics | p-Cymene | Citrus, Fresh, Solvent | 0.005010 | 184.81 | 417.29 | 925.9±44.9 | 2090.6±168.78 |

| 10 | 645-56-7 | Phenol | Phenol, 4-propyl- | Additives for fruit ices, jams, chewing gum | 0.107000 | 5.30 | 20.00 | 567.21±117.23 | 2139.79±104.12 |

| 11 | 97-53-0 | Phenol | Eugenol | Burnt, Clove, Spice | 0.002500 | 1625.74 | 1142.38 | 4064.35±265.06 | 2855.95±134.19 |

| 12 | 123-08-0 | Aldehyde | BenzAldehyde, 4-hydroxy- | Roast | - | - | - | 878.27±35.94 | 2301.59±137.88 |

| 13 | 53448-07-0 | Aldehyde | 2-Undecenal, E- | Bakery, Dairy, Meat, Seasoning Pickle Additives | 0.001400 | 601.17 | 1644.30 | 841.64±65.59 | 2302.03±161.4 |

| 14 | 2463-77-6 | Aldehyde | 2-Undecenal | Bakery, Dairy, Meat, Seasoning Pickle Additives | - | - | - | 810.23±30.02 | 2256.06±122.44 |

| 15 | 5910-87-2 | Aldehyde | 2,4-Nonadienal, (E,E)- | Cereal, Deep Fried, Fat, Watermelon, Wet Wool | 0.000100 | 10266.53 | 18183.86 | 1026.65±133.63 | 1818.39±139.21 |

| 16 | 100-52-7 | Aldehyde | BenzAldehyde | Bitter Almond, Burnt Sugar, Cherry, Malt, Roasted Pepper | 0.750890 | 1.48 | 1.18 | 1108.55±21.31 | 882.83±20.73 |

| 17 | 111-71-7 | Aldehyde | Heptanal | Citrus, Fat, Green, Nut | 0.002800 | 381.74 | 537.24 | 1068.87±30.31 | 1504.28±45.59 |

| 18 | 66-25-1 | Aldehyde | Hexanal | Apple, Fat, Fresh, Green, Oil | 0.061500 | 10.85 | 17.19 | 667.37±45.32 | 1057.05±27.89 |

| 19 | 3913-81-3 | Aldehyde | (E)-2-Decenal | Fat, Fish, Orange | 0.002700 | 206.48 | 775.05 | 557.48±99.61 | 2092.64±65.66 |

| 20 | 25152-84-5 | Aldehyde | 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E)- | Coriander, Deep Fried, Fat, Oil, Oxidized | 0.000077 | 16250.31 | 20052.04 | 1251.27±61.5 | 1544.01±51.11 |

| 21 | 35158-25-9 | Aldehyde | 2-Isopropyl-5-methylhex-2-enal | Floral | - | - | - | 822.05±75.88 | 1384.37±128.68 |

| 22 | 13877-91-3 | Terpenoids | .beta.-Ocimene | Floral | - | - | - | 1309.88±400.45 | 3178.73±583.19 |

| 23 | 18794-84-8 | Terpenoids | (E)-.beta.-Famesene | Spice, herb, fresh green, sweet | - | - | - | 1751.63±115.65 | 1088.94±61.17 |

| 24 | 99-85-4 | Terpenoids | .gamma.-Terpinene | Bitter, Citrus | 1.000000 | 1.14 | 1.50 | 1139.89±16.62 | 1495.44±42.78 |

| 25 | 3338-55-4 | Terpenoids | 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (Z)- | Floral | 0.034000 | 36.65 | 83.75 | 1246.21±373.83 | 2847.45±491.32 |

| 26 | 99-86-5 | Terpenoids | 1,3-Cyclohexadiene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | Lemon | 0.080000 | 14.00 | 27.65 | 1119.74±347.31 | 2211.81±382.22 |

| 27 | 99-83-2 | Terpenoids | .alpha.-Phellandrene 1 | Citrus, Fresh, Mint, Pepper, Spice, Wood | 0.040000 | 29.29 | 68.85 | 1171.55±437.16 | 2753.98±478.16 |

| 28 | 1193-18-6 | Ketone | 2-Cyclohexen-1-one, 3-methyl- | Savory | - | - | - | 1027.06±11.1 | 977.3±9.21 |

| 29 | 2497-21-4 | Ketone | 4-Hexen-3-one | Fruit | - | - | - | 1507.44±74.97 | 1728.39±26.55 |

| 30 | 30086-02-3 | Ketone | 3,5-Octadien-2-one, (E,E)- | Green | 0.100000 | 18.45 | 20.64 | 1844.87±46.97 | 2064.1±38.23 |

| 31 | 3796-70-1 | Ketone | 5,9-Undecadien-2-one, 6,10-dimethyl-, (E)- | Fruit | 0.060000 | 29.87 | 18.30 | 1792.31±113.17 | 1097.75±58.19 |

| 32 | 110-93-0 | Ketone | 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl- | Citrus, Mushroom, Pepper, Rubber, Strawberry | 0.068000 | 14.86 | 17.77 | 1010.69±10.07 | 1208.68±28.15 |

| 33 | 1072-83-9 | Heterocyclic compound | Ethanone, 1-(1H-pyrrol-2-yl)- | Bread, Cocoa, Hazelnut, Licorice, Walnut | 58.585250 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1026.21±6.3 | 963.10±22.23 |

| 34 | 18640-74-9 | Heterocyclic compound | 2-Isobutylthiazole | Green, Tomato, Tomato Leaf, Wine | 0.029000 | 17.46 | 12.24 | 506.47±8.82 | 355.03±8.21 |

| 35 | 13360-64-0 | Heterocyclic compound | Pyrazine, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | Fruit, Green | 0.016000 | 63.61 | 193.43 | 1017.71±415.87 | 3094.86±519.07 |

| 36 | 3777-69-3 | Heterocyclic compound | Furan, 2-pentyl- | Butter, Floral, Fruit, Green Bean | 0.005800 | 172.68 | 215.36 | 1001.55±61.01 | 1249.09±70.06 |

| 37 | 539-90-2 | Ester | Butanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester | Fruit | 0.009400 | 106.84 | 168.83 | 1004.3±64.62 | 1587.03±70.14 |

| 38 | 112-32-3 | Ester | Formic acid, octyl ester | Floral | - | - | - | 894.11±97.05 | 1350.55±89.24 |

| 39 | 112-06-1 | Ester | Acetic acid, heptyl ester | Floral, Fresh | 0.420000 | 2.16 | 3.23 | 905.4±70.49 | 1355.18±79.3 |

| 40 | 122-72-5 | Ester | 3-Phenyl-1-propanol, acetate | Floral | - | - | - | 577.91±184.22 | 1044.9±121.21 |

| 41 | 659-70-1 | Ester | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, 3-methylbutyl ester | Green | 0.020000 | 44.41 | 70.85 | 888.23±71.54 | 1416.91±171.11 |

| 42 | 120-51-4 | Ester | Benzyl Benzoate | Balsamic, Herb, Oil | 0.341000 | 3.86 | 2.46 | 1315.52±140.07 | 840.36±55.24 |

| 43 | 141-12-8 | Ester | 2,6-Octadien-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, acetate, (Z)- | Floral, Fruit | 2.000000 | 0.39 | 1.09 | 786.34±60.03 | 2189.92±125.53 |

| 44 | 2311-46-8 | Ester | Hexanoic acid, 1-methylethyl ester | Fresh | - | - | - | 1031.25±126.21 | 1592.28±200.12 |

| total content, μg kg-1 | 48957.05±2716.49 | 74772.15±2672.71 | |||||||

| Flavor Classification | CAS | Class I | Compounds |

| floral | 3777-69-3 | Heterocyclic compound | Furan, 2-pentyl- |

| 3338-55-4 | Terpenoids | 1,3,6-Octatriene, 3,7-dimethyl-, (Z)- | |

| 104-54-1 | Alcohol | 2-Propen-1-ol, 3-phenyl- | |

| 112-06-1 | Ester | Acetic acid, heptyl ester | |

| 141-12-8 | Ester | 2,6-Octadien-1-ol, 3,7-dimethyl-, acetate, (Z)- | |

| fruity | 539-90-2 | Ester | Butanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester |

| 13360-64-0 | Heterocyclic compound | Pyrazine, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | |

| 3796-70-1 | Ketone | 5,9-Undecadien-2-one, 6,10-dimethyl-, (E)- | |

| 645-56-7 | Phenol | Phenol, 4-propyl- | |

| green | 111-71-7 | Aldehyde | Heptanal |

| 659-70-1 | Ester | Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, 3-methylbutyl ester | |

| 30086-02-3 | Ketone | 3,5-Octadien-2-one, (E,E)- | |

| 18640-74-9 | Heterocyclic compound | 2-Isobutylthiazole | |

| 628-99-9 | Alcohol | 2-Nonanol | |

| 66-25-1 | Aldehyde | Hexanal | |

| 120-51-4 | Ester | Benzyl Benzoate | |

| Orange | 99-87-6 | Aromatics | p-Cymene |

| 99-83-2 | Terpenoids | .alpha.-Phellandrene 1 | |

| 110-93-0 | Ketone | 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl- | |

| 1195-32-0 | Aromatics | Benzene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)- | |

| 112-42-5 | Alcohol | 1-Undecanol | |

| Oil | 25152-84-5 | Aldehyde | 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E)- |

| 5910-87-2 | Aldehyde | 2,4-Nonadienal, (E,E)- | |

| 3913-81-3 | Aldehyde | (E)-2-Decenal | |

| Bitter | 97-53-0 | Phenol | Eugenol |

| 100-52-7 | Aldehyde | BenzAldehyde | |

| 99-85-4 | Terpenoids | .gamma.-Terpinene | |

| Lemon | 99-86-5 | Terpenoids | 1,3-Cyclohexadiene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- |

| bakery | 53448-07-0 | Aldehyde | 2-Undecenal, E- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).