Submitted:

27 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. In Vivo Assays

2.3. Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.4. Immunocytochemistry

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

3. Results

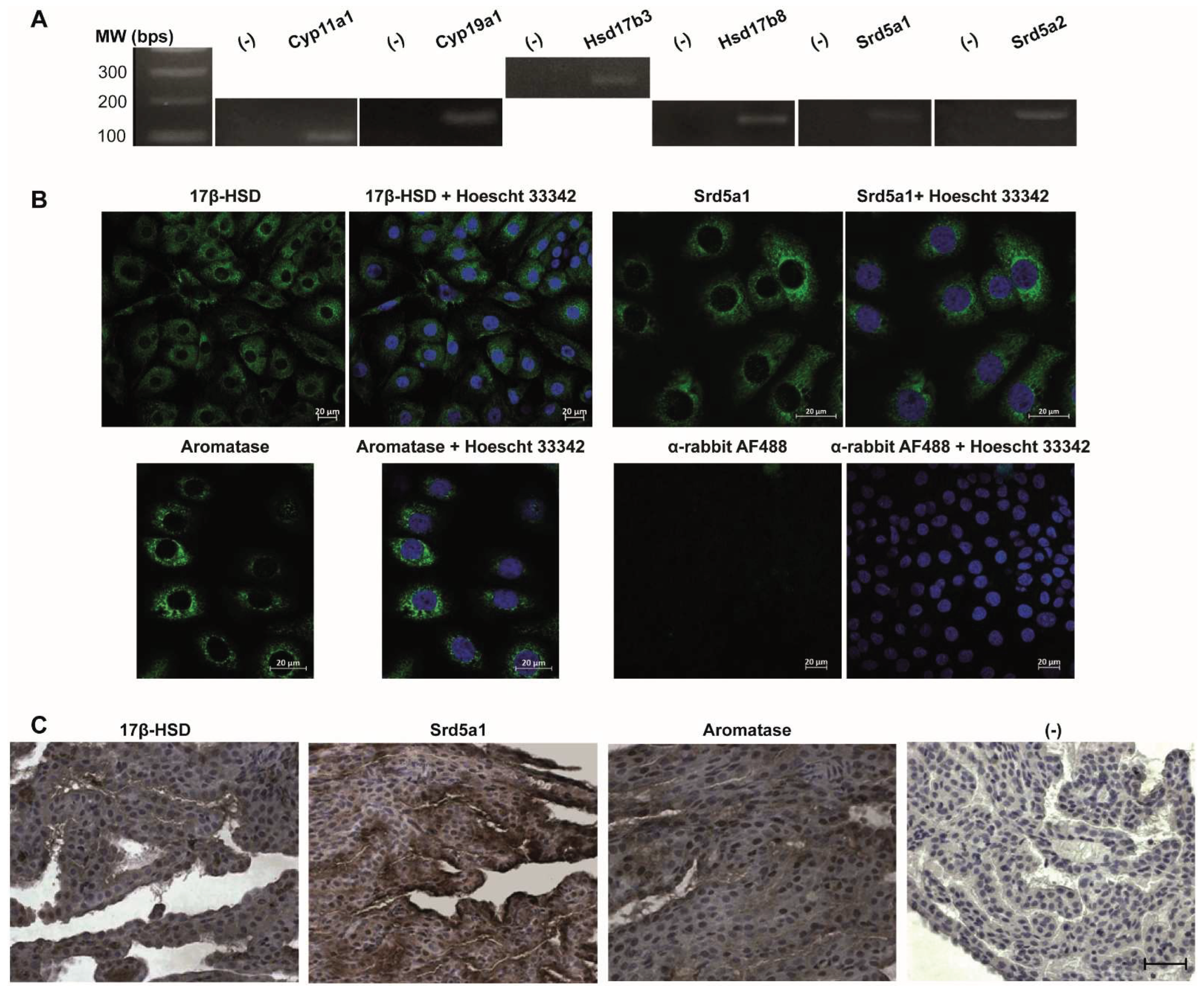

3.1. Gene and Protein Expression of Key Enzymes Involved in the Androgenic Pathway Are Found in Rat Choroid Plexus

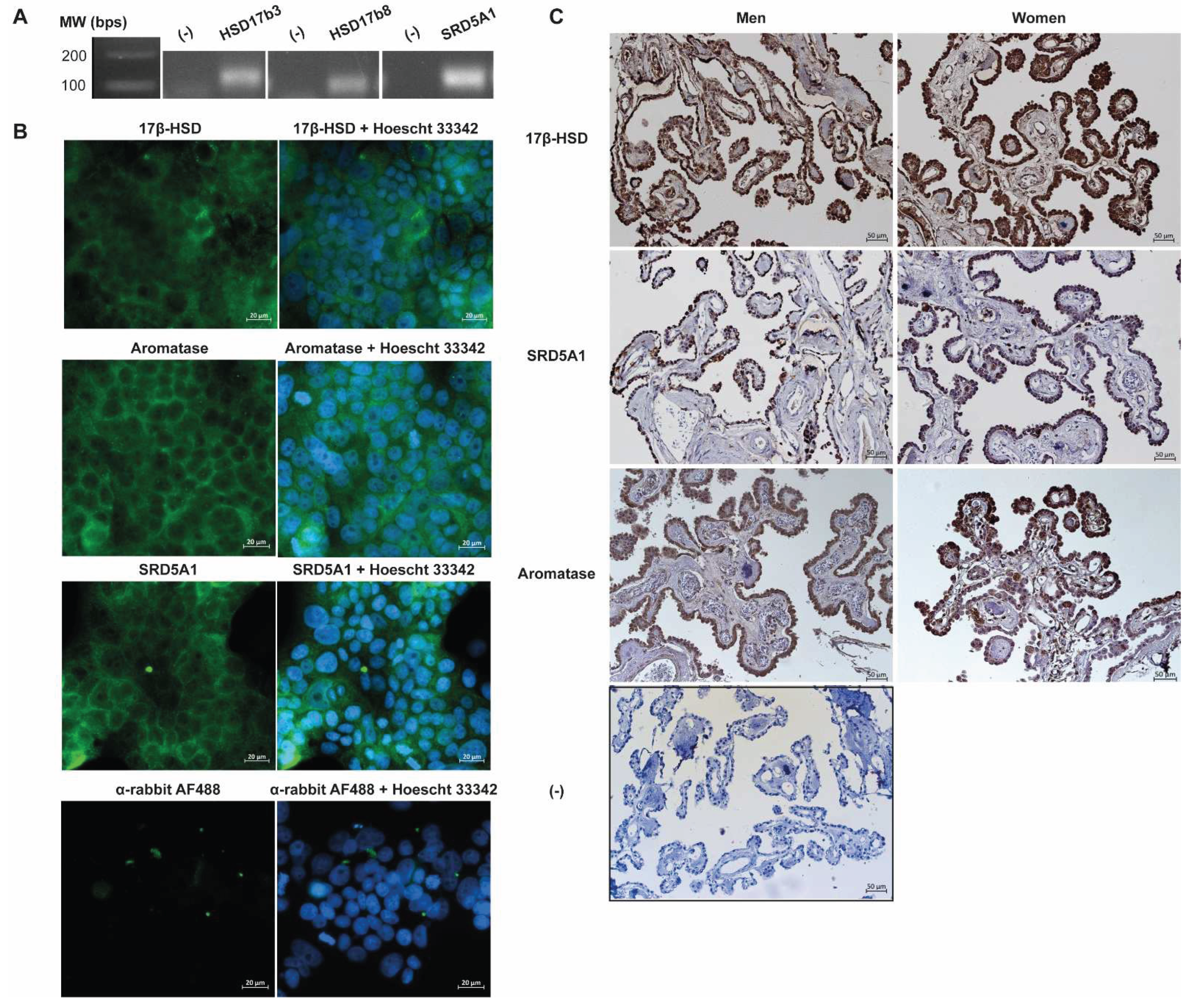

3.2. Gene and Protein Expression of Key Enzymes Involved in the Androgenic Pathway Are Found in the Human CP

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Redzic, Z.B.; Segal, M.B. The Structure of the Choroid Plexus and the Physiology of the Choroid Plexus Epithelium. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2004, 56, 1695–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.R.A.; Duarte, A.C.; Quintela, T.; Tomás, J.; Albuquerque, T.; Marques, F.; Palha, J.A.; Gonçalves, I. The Choroid Plexus as a Sex Hormone Target: Functional Implications. Front Neuroendocrinol 2017, 44, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praetorius, J.; Damkier, H.H. Transport across the Choroid Plexus Epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2017, 312, C673–C686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, R.; Robert Snodgrass, S.; Johanson, C.E. A Balanced View of the Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition and Functions: Focus on Adult Humans. Exp Neurol 2015, 273, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, T.; Ugalde, C.; Spuch, C.; Antequera, D.; Morán, M.J.; Martín, M.A.; Ferrer, I.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Carro, E. Aβ Accumulation in Choroid Plexus Is Associated with Mitochondrial-Induced Apoptosis. Neurobiol Aging 2010, 31, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerich, D.F.; Skinner, S.J.M.; Borlongan, C. V.; Vasconcellos, A. V.; Thanos, C.G. The Choroid Plexus in the Rise, Fall and Repair of the Brain. BioEssays 2005, 27, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speake, T.; Whitwell, C.; Kajita, H.; Majid, A.; Brown, P.D. Mechanisms of CSF Secretion by the Choroid Plexus. Microsc Res Tech 2001, 52, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipor, J.; Thiery, J. The Choroid Plexus Cerebrospinal Fluid System.Pdf. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 2008, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, A.M.; Marques, F.; Novais, A.; Sousa, N.; Palha, J.A.; Sousa, J.C. The Path from the Choroid Plexus to the Subventricular Zone: Go with the Flow! Front Cell Neurosci 2012, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, C.; Stopa, E.; Mcmillan, P.; Roth, D.; Funk, J.; Krinke, G. The Distributional Nexus of Choroid Plexus to Cerebrospinal Fluid, Ependyma and Brain:Toxicologic/Pathologic Phenomena, Periventricular Destabilization, and Lesion Spread. Toxicol Pathol 2011, 39, 186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodobski, A.; Szmydynger-Chodobska, J. Choroid Plexus: Target for Polypeptides and Site of Their Synthesis. Microsc Res Tech 2001, 52, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Chopp, M. Cell Proliferation and Differentiation from Ependymal, Subependymal and Choroid Plexus Cells in Response to Stroke in Rats. J Neurol Sci 2002, 193, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerich, D.F.; Borlongan, C. V. Potential of Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cell Grafts for Neuroprotection in Huntington’s Disease: What Remains before Considering Clinical Trials. Neurotox Res 2009, 15, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah-Nyagan, A.G.; Do-Rego, J.-L.; Beaujean, D.; Luu-The, V.; Pelletier, G.; Vaudry, H. Neurosteroids: Expression of Steroidogenic Enzymes and Regulation of Steroid Biosynthesis in the Central Nervous System. Pharmacol Rev 1999, 51, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel-Wagner, B. Neurosteroid Metabolism in the Human Brain. Eur J Endocrinol 2001, 145, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The Molecular Biology, Biochemistry, and Physiology of Human Steroidogenesis and Its Disorders. Endocr Rev 2011, 32, 81–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Pramanik, J.; Mahata, B. Revisiting Steroidogenesis and Its Role in Immune Regulation with the Advanced Tools and Technologies. Genes Immun 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, M.F.; Stoker, C.; Rossetti, M.F.; Lazzarino, G.P.; Luque, E.H.; Ramos, J.G. Dietary Withdrawal of Phytoestrogens Resulted in Higher Gene Expression of 3-Beta-HSD and ARO but Lower 5-Alpha-R-1 in Male Rats. Nutrition Research 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcoitia, I.; Mendez, P.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Aromatase in the Human Brain. Androgens 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, M.P.; Casti, A.; Casu, A.; Frau, R.; Bortolato, M.; Spiga, S.; Ennas, M.G. Regional Distribution of 5α-Reductase Type 2 in the Adult Rat Brain: An Immunohistochemical Analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giatti, S.; Diviccaro, S.; Garcia-Segura, L.M.; Melcangi, R.C. Sex Differences in the Brain Expression of Steroidogenic Molecules under Basal Conditions and after Gonadectomy. J Neuroendocrinol 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojo, Y.; Murakami, G.; Mukai, H.; Higo, S.; Hatanaka, Y.; Ogiue-Ikeda, M.; Ishii, H.; Kimoto, T.; Kawato, S. Estrogen Synthesis in the Brain-Role in Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2008, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimoto, T.; Ishii, H.; Higo, S.; Hojo, Y.; Kawato, S. Semicomprehensive Analysis of the Postnatal Age-Related Changes in the MRNA Expression of Sex Steroidogenic Enzymes and Sex Steroid Receptors in the Male Rat Hippocampus. Endocrinology 2010, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyokage, E.; Toida, K.; Suzuki-Yamamoto, T.; Ishimura, K. Cellular Localization of 5α-Reductase in the Rat Cerebellum. J Chem Neuroanat 2014, 59–60, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicaj, M.L.; Pasquini, L.A.; Lima, A.; Gonzalez Deniselle, M.C.; Pasquini, J.M.; De Nicola, A.F.; Garay, L.I. Changes in Neurosteroidogenesis during Demyelination and Remyelination in Cuprizone-Treated Mice. J Neuroendocrinol 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, H.; Tsurugizawa, T.; Ogiue-Ikeda, M.; Murakami, G.; Hojo, Y.; Ishii, H.; Kimoto, T.; Kawato, S. Local Neurosteroid Production in the Hippocampus: Influence on Synaptic Plasticity of Memory. In Proceedings of the Neuroendocrinology, 2007; 84. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, S.; Nishikawa, K.; Honda, Y.; Nakajin, S. Expression in E. Coli and Tissue Distribution of the Human Homologue of the Mouse Ke 6 Gene, 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 8. Mol Cell Biochem 2008, 309, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, L.; Barnard, L.; Baranowski, E.S.; Gilligan, L.C.; Taylor, A.E.; Arlt, W.; Shackleton, C.H.L.; Storbeck, K.H. Human Steroid Biosynthesis, Metabolism and Excretion Are Differentially Reflected by Serum and Urine Steroid Metabolomes: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 2019, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai-Morris, C.H.; Khanum, A.; Tang, P.-Z.; Dufau, M.L. The Rat 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type III: Molecular Cloning and Gonadotropin Regulation. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 3534–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, S.D. Effects of Testosterone on Cognitive and Brain Aging in Elderly Men. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005, 1055, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brann, D.W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Thakkar, R.; Sareddy, G.R.; Pratap, U.P.; Tekmal, R.R.; Vadlamudi, R.K. Brain-Derived Estrogen and Neural Function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolick, K.N.; Zhu, Q.; Shi, H. Effects of Estrogens on Central Nervous System Neurotransmission: Implications for Sex Differences in Mental Disorders. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science; 2018; 160. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante-Barrientos, F.A.; Méndez-Ruette, M.; Ortloff, A.; Luz-Crawford, P.; Rivera, F.J.; Figueroa, C.D.; Molina, L.; Bátiz, L.F. The Impact of Estrogen and Estrogen-Like Molecules in Neurogenesis and Neurodegeneration: Beneficial or Harmful? Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspesi, D.; Cornil, C.A. Role of Neuroestrogens in the Regulation of Social Behaviors—From Social Recognition to Mating. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2024, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luine, V.; Frankfurt, M. Estrogenic Regulation of Memory: The First 50 Years. Horm Behav 2020, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintela, T.; Gonçalves, I.; Carreto, L.C.; Santos, M.A.S.; Marcelino, H.; Patriarca, F.M.; Santos, C.R.A. Analysis of the Effects of Sex Hormone Background on the Rat Choroid Plexus Transcriptome by CDNA Microarrays. PLoS ONE 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Yano, A.; Ishimura, K. Effect of Peripherally Derived Steroid Hormones on the Expression of Steroidogenic Enzymes in the Rat Choroid Plexus. The Journal of Medical Investigation 2021, 68, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.W.; Westgate, C.S.J.; Hornby, C.; Botfield, H.; Taylor, A.E.; Markey, K.; Mitchell, J.L.; Scotton, W.J.; Mollan, S.P.; Yiangou, A.; et al. A Unique Androgen Excess Signature in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Is Linked to Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, I.; Quintela, T.; Duarte, A.C.; Hubbard, P.; Schwerk, C.; Belin, A.C.; Toma, J.; Santos, R.A. Experimental Tools to Study the Regulation and Function of the Choroid Plexus. In Blood-Brain Barrier. Neuromethods; Barichello, T., Ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 142, ISBN 9781493989461. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata, I.; Ishiwata, C.; Ishiwata, E.; Sato, Y.; Kiguchi, K.; Tachibana, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Ishikawa, H. Establishment and Characterization of a Human Malignant Choroids Plexus Papilloma Cell Line (HIBCPP). Hum Cell 2005, 18, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong-Goka, B.C.; Chang, F.-L.F. Estrogen Receptors α and β in Choroid Plexus Epithelial Cells in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci Lett 2004, 360, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.H.; Gonçalves, I.; Socorro, S.; Baltazar, G.; Quintela, T.; Santos, C.R.A. Androgen Receptor Is Expressed in Murine Choroid Plexus and Downregulated by 5α-Dihydrotestosterone in Male and Female Mice. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 2009, 38, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, T.; Alves, C.H.; Goncalves, I.; Baltazar, G.; Saraiva, M.J.; Santos, C.R. 5Alpha-Dihydrotestosterone up-Regulates Transthyretin Levels in Mice and Rat Choroid Plexus via an Androgen Receptor Independent Pathway. Brain Res 2008, 1229, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintela, T.; Goncalves, I.; Baltazar, G.; Alves, C.H.; Saraiva, M.J.; Santos, C.R. 17beta-Estradiol Induces Transthyretin Expression in Murine Choroid Plexus via an Oestrogen Receptor Dependent Pathway. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2009, 29, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintela, T.; Goncalves, I.; Martinho, A.; Alves, C.H.; Saraiva, M.J.; Rocha, P.; Santos, C.R. Progesterone Enhances Transthyretin Expression in the Rat Choroid Plexus in Vitro and in Vivo via Progesterone Receptor. J Mol Neurosci 2011, 44, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, K.A.; Harvey, A.R.; Carruthers, M.; Martins, R.N. Androgens, Andropause and Neurodegeneration: Exploring the Link between Steroidogenesis, Androgens and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2005, 62, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mellon, S.H.; Vaudry, H.B.T.-I.R. of N. Biosynthesis of Neurosteroids and Regulation of Their Sysnthesis. In Neurosteroids and Brain Function; Academic Press, 2001; Vol. 46, pp. 33–78 ISBN 0074-7742.

- Pelletier, G. Chapter 11—Steroidogenic Enzymes in the Brain: Morphological Aspects. In Neuroendocrinology: The Normal Neuroendocrine System; Martini, L.B.T.-P., Ed.; Elsevier, 2010; Volume 181, pp. 193–207. ISBN 0079-6123. [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier, G.; Luu-The, V.; Labrie, F. Immunocytochemical Localization of 5α-Reductase in Rat Brain. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 1994, 5, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, Y.; Hattori, T.; Enami, T.; Furukawa, A.; Suzuki, K.; Ishii, H.; Mukai, H.; Morrison, J.H.; Janssen, W.G.M.; Kominami, S.; et al. Adult Male Rat Hippocampus Synthesizes Estradiol from Pregnenolone by Cytochromes P45017α and P450 Aromatase Localized in Neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, M.W.; Westgate, C.S.J.; Hornby, C.; Botfield, H.; Taylor, A.E.; Markey, K.; Mitchell, J.L.; Scotton, W.J.; Mollan, S.P.; Yiangou, A.; et al. A Unique Androgen Excess Signature in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Is Linked to Cerebrospinal Fluid Dynamics. JCI Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnone, N.A.; Mellon, S.H. Neurosteroids: Biosynthesis and Function of These Novel Neuromodulators. Front Neuroendocrinol 2000, 21, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.R.; Clyne, C.; Rubin, G.; Wah, C.B.; Robertson, K.; Britt, K.; Speed, C.; Jones, M. Aromatase—A Brief Overview. Annu Rev Physiol 2002, 64, 93–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, G.; Luu-The, V.; Labrie, F. Immunocytochemical Localization of Type I 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase in the Rat Brain. Brain Res 1995, 704, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, E; Labrie, F; Luu-The, V; Pelletier, G Localization of 17 Beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase throughout Gestation in Human Placenta. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 1991, 39, 1403–1407. [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Lorena, P.D.N.; Ng, L.K.; Lim, D.; Shen, L.; Siow, W.Y.; Teh, M.; Reichardt, J.K. V; Salto-Tellez, M. Differential Expression of Steroid 5α-Reductase Isozymes and Association with Disease Severity and Angiogenic Genes Predict Their Biological Role in Prostate Cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2010, 17, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, E.D. Brain 5α-Reductase: Cellular, Enzymatic, and Molecular Perspectives and Implications for Biological Function. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 1993, 4, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, C.J.; Nguyen, T.-V. V; Ramsden, M.; Yao, M.; Murphy, M.P.; Rosario, E.R. Androgen Cell Signaling Pathways Involved in Neuroprotective Actions. Horm Behav 2008, 53, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.K.; Jones, C.K.; Newhouse, P.A. The Role of Estrogen in Brain and Cognitive Aging. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Primer Fw (5′-3′) | Primer Rv (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Annealing temperature (˚C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | ||||

| CYP11A1 | CAAAACACCACGCACTTCC | TCAATTCTGAAGTTTTCCAGCA | 125 | 54 |

| CYP19A1 | CGTCATGTTGCTTCTCATCG | TACCGCAGGCTCTCGTTAAT | 150 | 60 |

| HSD17b3 | CCAACCTGCTCCCAAGTCAT | AGGGGTCAGCACCTGGATAA | 278 | 60 |

| HSD17b8 | TTTTTCGCCCGCCATCTGTCG | TGCAGGTGCCAGGAGCTACCA | 167 | 59 |

| Srd5a1 | TGCTCGACATGCTGGTCTAC | GGCTGCAGGACGAATGTACT | 194 | 60 |

| Srd5a2 | ATTTGTGTGGCAGAGAGAGG | TTGATTGACTGCCTGGATGG | 192 | 59 |

| Human | ||||

| CYP11A1 | CACGCTCAGTCCTGGTCAAA | GGGGATCTCATTGAAGGGGC | 134 | 58 |

| CYP19A1 | CGTCGCGACTCTAAATTGCC | AAAAAGGCCAGTGAGGAGCA | 149 | 58 |

| HSD17b3 | TTCTTGCGGTCAATGGGACA | TTTTCCAGCGTCCGGCTAAT | 125 | 58 |

| HSD17b8 | TTTTCTCGCCCACCATCTGT | AAGGTGCCCTTGAGGTTGAC | 119 | 58 |

| SRD5A1 | TACGGGCATCGGTGCTTAAT | ACACTGCACAATGGCTCAAG | 139 | 58 |

| SRD5A2 | CAGGTTCAGTGCCAGCAGAG | TCTCCGTGTGCTTCCCGTAG | 112 | 58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).