Submitted:

26 May 2025

Posted:

28 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Demographic Data of the Study Patients

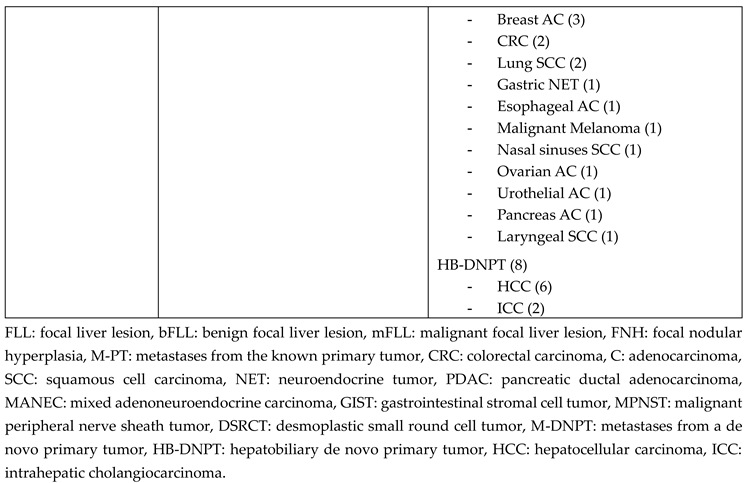

2.2. Underlying Primary Tumors in the Study Cohort

2.3. Diagnostic Workup for Focal Liver Lesions (FLL)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

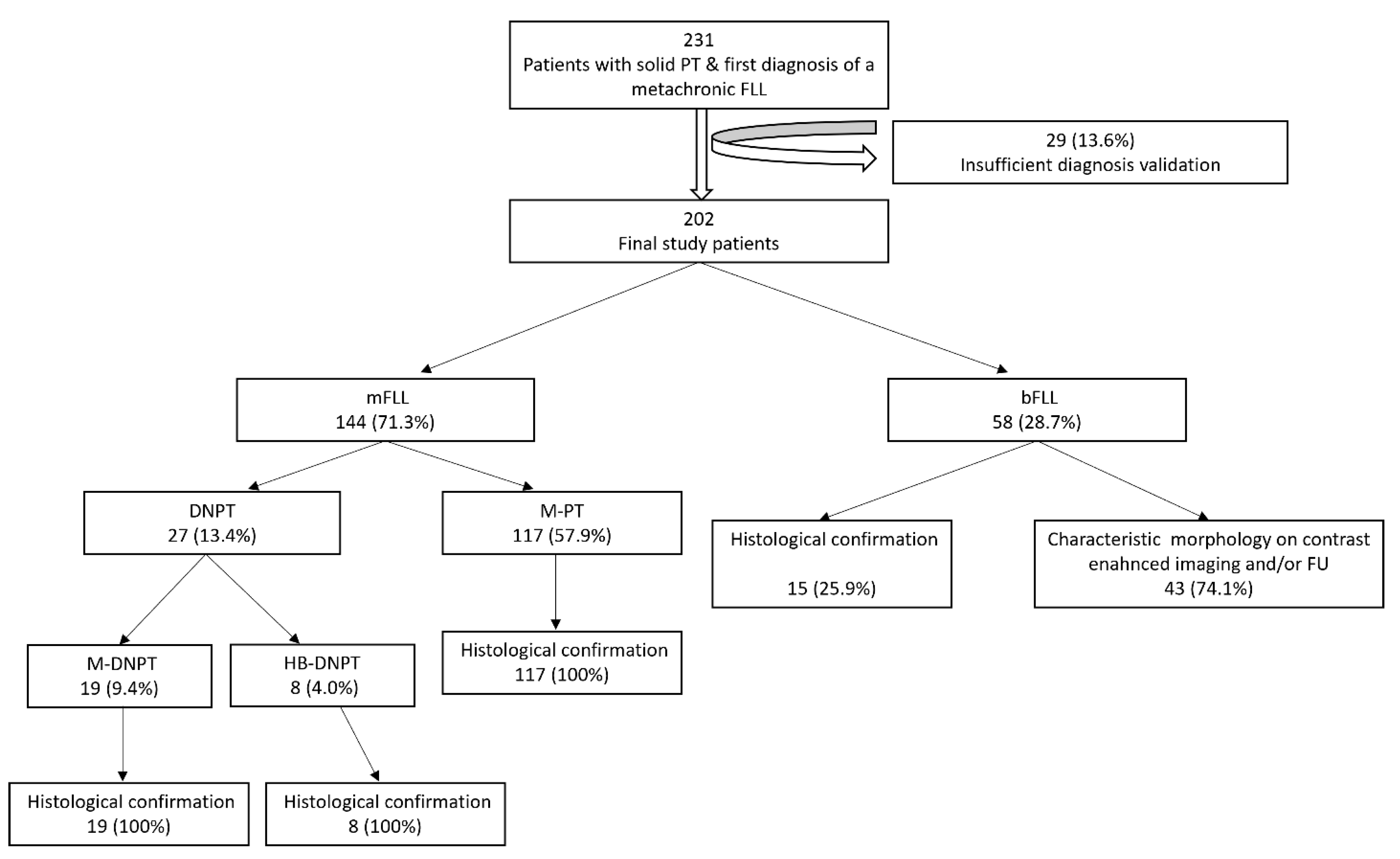

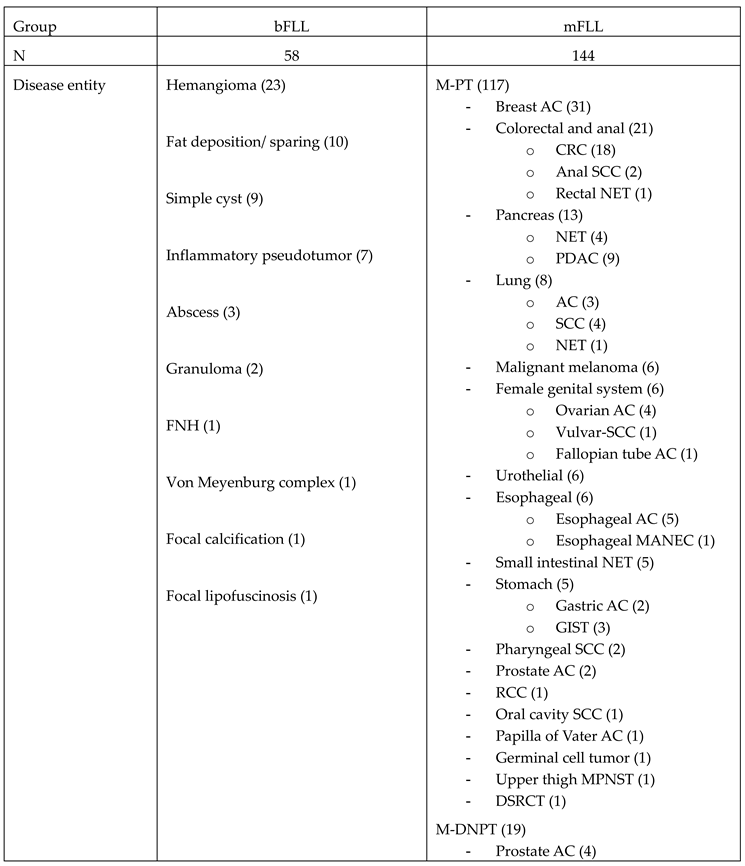

3.1. Final FLL Etiology

3.2. Clinical Features

3.3. Sonographic Features

| Group | bFLL | M-PT | M-DNPT | HB-DPT |

p-value |

| N (%) | 58 (28.7) | 117 (57.9) | 19 (9.4) | 8 (4.0) | |

| Age (years) | 61±14 | 64±13 | 70±8 | 75±8 | 0.12 |

| Males (%) | 30 (51.7) | 51 (43.6) | 13 (68.4) | 4 (50.0) | 0.79 |

| Latency period (months) |

60.3 ± 81.4 | 57.3 ± 65.1 | 80.1 ± 59.8 | 110.6 ± 117.4 | 0.16 |

| Presence of EHM (%) | 18 (31.0) | 73 (62.4%) | 12 (63.2%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.004 |

| Time of diagnosis of EHM: concurrent/ preexisting | 6/12 | 40/33 | 8/4 | 1/1 | 0.29 |

| Ascites | 2 (3.4) | 15 (12.8) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (12.5) | 0.20 |

| FLL size (cm) | 1.9±2.1 | 3.2±2.8 | 3.2±1.4 | 4.8±1.7 | 0.009 |

| Hypoechoic echotexture (%) | 28 (48.3) | 92 (78.6) | 15 (78.9) | 4 (50.0) | 0.01 |

| Multiple lesions (%) | 10 (17.2) | 65 (55.6) | 15 (78.9) | 1 (12.5) | 0.002 |

3.4. PT–FLL Concordance Rate

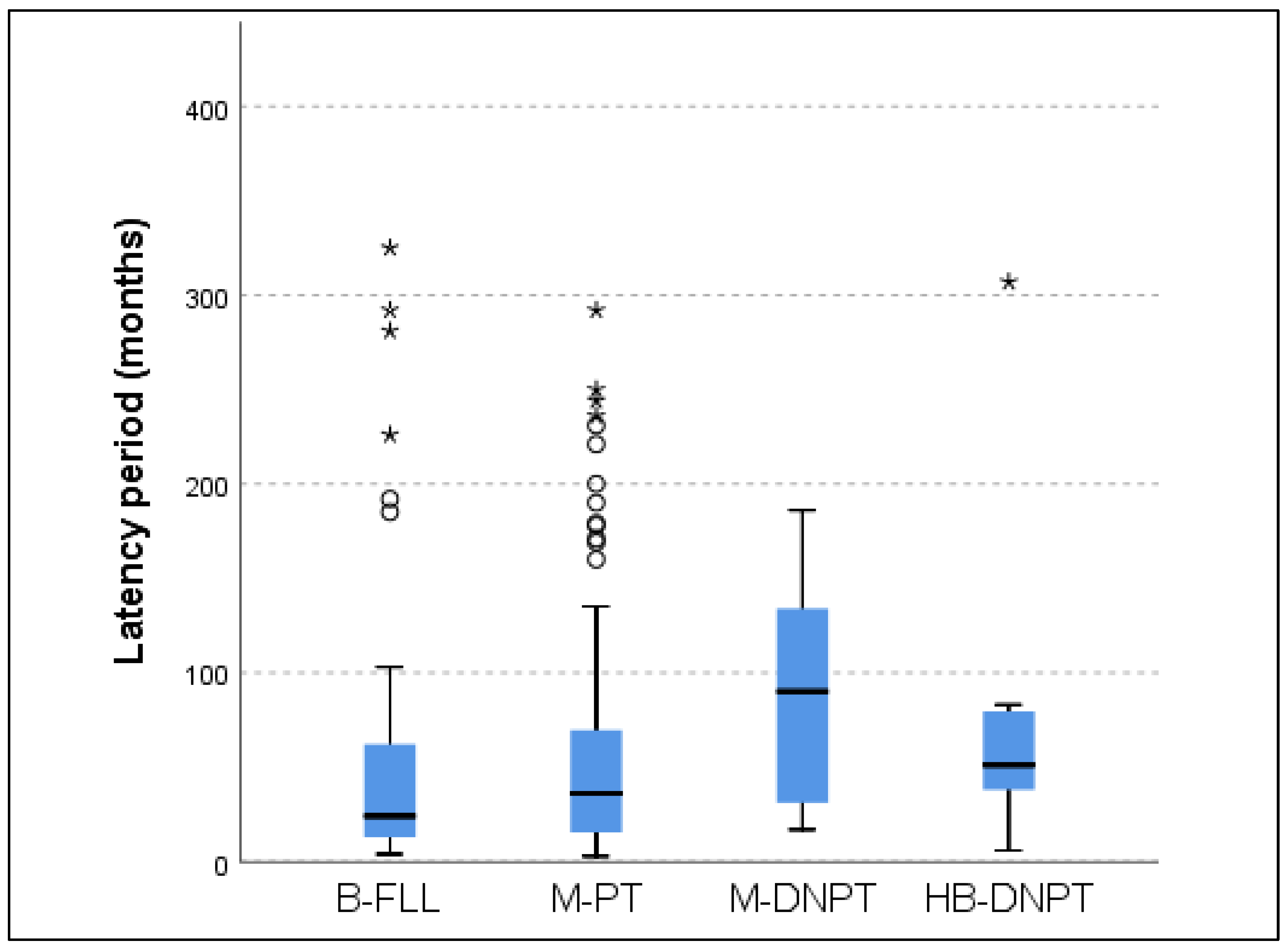

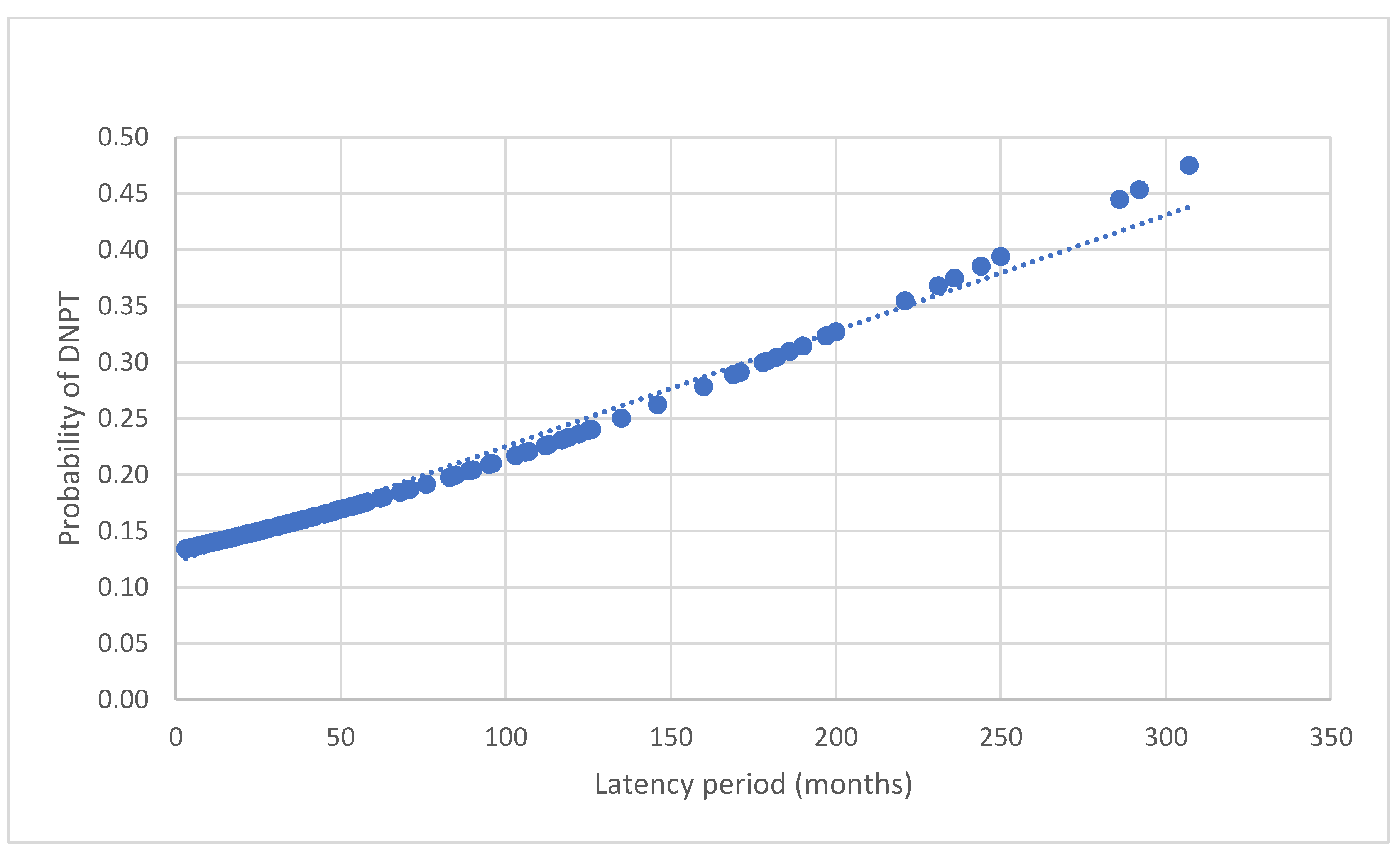

3.5. Latency Period (LP) in Malignant FLL (mFLL)

4. Discussion

|

Clinical background |

Prevalence of malignant FLL (%) |

N |

Year |

Author |

| Incidental finding in asymptomatic patients | 0.6 | 542 | 2016 | Choi et al. [28] |

| Patients with synchronous hematological malignancy | 33.0 | 61 | 2013 | Heller et al. [26] |

| Patients with a synchronous non-hematological malignancy | 59.4 | 434 | 2021 | Safai Zadeh et al. [17] |

| Patients with liver cirrhosis | 68.4 | 228 | 2022 | Alhyari et al. [18] |

| Patients with metachronous non-hematological malignancy | 71.3 | 202 | 2025 | Present study |

5. Conclusions

References

- Kow, A.W.C. Hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology 2019, 10, 1274–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltenbach, T.E.; Engler, P.; Kratzer, W.; Oeztuerk, S.; Seufferlein, T.; Haenle, M.M.; Graeter, T. Prevalence of benign focal liver lesions: ultrasound investigation of 45,319 hospital patients. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016, 41, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawatzki, M.; Husarik, D.B.; Semela, D. Assessment of focal liver lesions in non-cirrhotic liver – expert opinion statement by the Swiss Association for the Study of the Liver and the Swiss Society of Gastroenterology. Swiss Medical Weekly 2023, 153, 40099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.Y.; Hinshaw, J.L.; Borman, E.J.; Gegios, A.; Leverson, G.; Winslow, E.R. Assessing Normal Growth of Hepatic Hemangiomas During Long-term Follow-up. JAMA Surgery 2014, 149, 1266–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguram, R.; Ghonge, A.; Tse, J.; Dhanasekaran, R. Practical approach to diagnose and manage benign liver masses. Hepatol Commun 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Raghu, V.; Virmani, V.; Sheikh, A.; Al Heidous, M.; Tirumani, S. Unveiling the unreal: Comprehensive imaging review of hepatic pseudolesions. Clinical Imaging 2021, 80, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnana, M.; Sevrukov, A.B.; Elsayes, K.M.; Viswanathan, C.; Lubner, M.; Menias, C.O. Inflammatory Pseudotumor: The Great Mimicker. American Journal of Roentgenology 2012, 198, W217–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabaud, C.; Al-Rabih, W.R.; Chen, P.J.; Evason, K.; Ferrell, L.; Hernandez-Prera, J.C.; Huang, S.F.; Longerich, T.; Park, Y.N.; Quaglia, A.; et al. Focal Nodular Hyperplasia and Hepatocellular Adenoma around the World Viewed through the Scope of the Immunopathological Classification. Int J Hepatol 2013, 2013, 268625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, M.C.; Olson, M.C.; Flicek, K.T.; Patel, N.J.; Bolan, C.W.; Menias, C.O.; Wang, Z.; Venkatesh, S.K. Chemotherapy-associated liver morphological changes in hepatic metastases (CALMCHeM). Diagn Interv Radiol 2023, 29, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.J.A. The effects of cancer chemotherapy on liver imaging. European Radiology 2009, 19, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obenauf, A.C.; Massagué, J. Surviving at a Distance: Organ-Specific Metastasis. Trends Cancer 2015, 1, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudon, M.; Dietrich, C.F.; Choi, B.I.; Cosgrove, D.O.; Kudo, M.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Piscaglia, F.; Wilson, S.R.; Barr, R.G.; Chammas, M.C.; et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver--update 2012: a WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultraschall Med 2013, 34, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Sharma, M.; Gibson, R.N.; Schreiber-Dietrich, D.; Jenssen, C. Fortuitously discovered liver lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 3173–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, W.P.; Mao, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, D.; Tannapfel, A.; Meloni, M.F.; Neye, H.; Clevert, D.A.; Dietrich, C.F. Imaging Features of Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound. Ultraschall Med 2021, 42, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich-Rust, M.; Klopffleisch, T.; Nierhoff, J.; Herrmann, E.; Vermehren, J.; Schneider, M.D.; Zeuzem, S.; Bojunga, J. Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound for the differentiation of benign and malignant focal liver lesions: a meta-analysis. Liver Int 2013, 33, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantinga, M.A.; Gevers, T.J.; Drenth, J.P. Evaluation of hepatic cystic lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2013, 19, 3543–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safai Zadeh, E.; Baumgarten, M.A.; Dietrich, C.F.; Görg, C.; Neesse, A.; Trenker, C.; Alhyari, A. Frequency of synchronous malignant liver lesions initially detected by ultrasound in patients with newly diagnosed underlying non-hematologic malignant disease: a retrospective study in 434 patients. Z Gastroenterol 2022, 60, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhyari, A.; Görg, C.; Alakhras, R.; Dietrich, C.F.; Trenker, C.; Safai Zadeh, E. HCC or Something Else? Frequency of Various Benign and Malignant Etiologies in Cirrhotic Patients with Newly Detected Focal Liver Lesions in Relation to Different Clinical and Sonographic Parameters. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Nolsøe, C.P.; Barr, R.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Burns, P.N.; Cantisani, V.; Chammas, M.C.; Chaubal, N.; Choi, B.I.; Clevert, D.A.; et al. Guidelines and Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Liver-Update 2020 WFUMB in Cooperation with EFSUMB, AFSUMB, AIUM, and FLAUS. Ultrasound Med Biol 2020, 46, 2579–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatik, T.; Schuler, A.; Kunze, G.; Mauch, M.; Dietrich, C.F.; Dirks, K.; Pachmann, C.; Börner, N.; Fellermann, K.; Menzel, J.; et al. Benefit of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Follow-Up Care of Patients with Colon Cancer: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Ultraschall Med 2015, 36, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garajova, I.; Balsano, R.; Tommasi, C.; Dalla Valle, R.; Pedrazzi, G.; Ravaioli, M.; Spallanzani, A.; Leonardi, F.; Santini, C.; Caputo, F.; et al. Synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastases: impact of primary tumor location on patterns of recurrence and survival after hepatic resection. Acta Biomed 2020, 92, e2021061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safai Zadeh, E.; Prosch, H.; Ba-Ssalamah, A.; Findeisen, H.; Alhyari, A.; Raab, N.; Görg, C. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the liver: basics and interpretation of common focal lesions. Rofo 2024, 196, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șirli, R.; Popescu, A.; Jenssen, C.; Möller, K.; Lim, A.; Dong, Y.; Sporea, I.; Nürnberg, D.; Petry, M.; Dietrich, C.F. WFUMB Review Paper. Incidental Findings in Otherwise Healthy Subjects, How to Manage: Liver. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heese, F.; Görg, C. [The value of highest quality ultrasound as a reference for ultrasound diagnosis]. Ultraschall Med 2006, 27, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Byun, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Won, H.J.; Shin, Y.M.; Kim, P.N. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System v2014 With Gadoxetate Disodium-Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Validation of LI-RADS Category 4 and 5 Criteria. Invest Radiol 2016, 51, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, E.; Görg, C. [Focal liver lesions in patients with malignant haematological disease: value of B-mode ultrasound in comparison to contrast-enhanced ultrasound--a retrospective study with N = 61 patients]. Z Gastroenterol 2013, 51, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Y.; Tameda, M.; Nakagawa, H. Metachronous Liver Metastasis during Long-term Follow-up after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of a Small Rectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasm. Intern Med 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Park, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Sohn, J.H.; Chung, E.C.; Park, H.W. Focal hepatic solid lesions incidentally detected on initial ultrasonography in 542 asymptomatic patients. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016, 41, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, K.; Greis, C.; Schuler, A.; Bernatik, T.; Blank, W.; Dietrich, C.F.; Strobel, D. Frequency of tumor entities among liver tumors of unclear etiology initially detected by sonography in the noncirrhotic or cirrhotic livers of 1349 patients. Results of the DEGUM multicenter study. Ultraschall Med 2011, 32, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Wang, K.; Ding, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Ding, L. Which patients are prone to suffer liver metastasis? A review of risk factors of metachronous liver metastasis of colorectal cancer. European Journal of Medical Research 2022, 27, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.C.; Su, Y.C.; Lu, C.Y.; Hsu, H.T.; Sun, L.C.; Shih, Y.L.; Ker, C.G.; Hsieh, J.S.; Lee, K.T.; Wang, J.Y. Risk factors for the development of metachronous liver metastasis in colorectal cancer patients after curative resection. World J Surg 2011, 35, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Liang, L.; Ren, L.; Chen, J.; Wei, Y.; Chang, W.; Zhu, D.; Lin, Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, J. A specific KRAS codon 13 mutation is an independent predictor for colorectal cancer metachronous distant metastases. Am J Cancer Res 2015, 5, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.W.; Tsai, H.L.; Chen, Y.T.; Huang, C.M.; Ma, C.J.; Lu, C.Y.; Kuo, C.H.; Wu, D.C.; Chai, C.Y.; Wang, J.Y. The prognostic values of EGFR expression and KRAS mutation in patients with synchronous or metachronous metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Bakar, M.A.; Saba, A.; Khan, M.A.; Akbar, S.A.; Islam Nasir, I.U. Risk factors effecting development of metachronous liver metastasis in rectal cancer patients after curative surgical resection. Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Lahore experience. J Pak Med Assoc 2019, 69, 201–204. [Google Scholar]

- Laubert, T.; Bente, V.; Freitag-Wolf, S.; Voulgaris, H.; Oberländer, M.; Schillo, K.; Kleemann, M.; Bürk, C.; Bruch, H.P.; Roblick, U.J.; et al. Aneuploidy and elevated CEA indicate an increased risk for metachronous metastasis in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013, 28, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margonis, G.A.; Buettner, S.; Andreatos, N.; Kim, Y.; Wagner, D.; Sasaki, K.; Beer, A.; Schwarz, C.; Løes, I.M.; Smolle, M.; et al. Association of BRAF Mutations With Survival and Recurrence in Surgically Treated Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Liver Cancer. JAMA Surg 2018, 153, e180996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.D.; Peng, Y.F.; Xiao, G.; Gu, J. High levels of serum platelet-derived growth factor-AA and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 are predictors of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantaleo, M.A.; Astolfi, A.; Nannini, M.; Paterini, P.; Piazzi, G.; Ercolani, G.; Brandi, G.; Martinelli, G.; Pession, A.; Pinna, A.D.; et al. Gene expression profiling of liver metastases from colorectal cancer as potential basis for treatment choice. Br J Cancer 2008, 99, 1729–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styczen, H.; Nagelmeier, I.; Beissbarth, T.; Nietert, M.; Homayounfar, K.; Sprenger, T.; Boczek, U.; Stanek, K.; Kitz, J.; Wolff, H.A.; et al. HER-2 and HER-3 expression in liver metastases of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 15065–15076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Ren, L.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, D.; Chang, W.; He, G.; Ji, M.; Jian, M.; Lin, Q.; Yi, T.; et al. Differences in clinical characteristics and mutational pattern between synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastases. Cancer Manag Res 2018, 10, 2871–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S, D.; L, W.; B, G.Y.; F, Y.H.; H, S.X.; Q, M.Z.; Hao, C.; W, C.Q.; S, L.Z. Risk factors of liver metastasis from advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a large multicenter cohort study. World J Surg Oncol 2017, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolston, R.; Sasatomi, E.; Hunt, J.; Swalsky, P.A.; Finkelstein, S.D. Distinguishing de novo second cancer formation from tumor recurrence: mutational fingerprinting by microdissection genotyping. J Mol Diagn 2001, 3, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J.; Amunyela, O.I.; Nyantakyi, A.Y.; Ayabilah, E.A.; Tackie, J.N.O.; Kyei, K.A. Prevalence and clinicopathological characteristics of de novo metastatic cancer at a major radiotherapy centre in West Africa: a cross-sectional study. Ecancermedicalscience 2024, 18, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

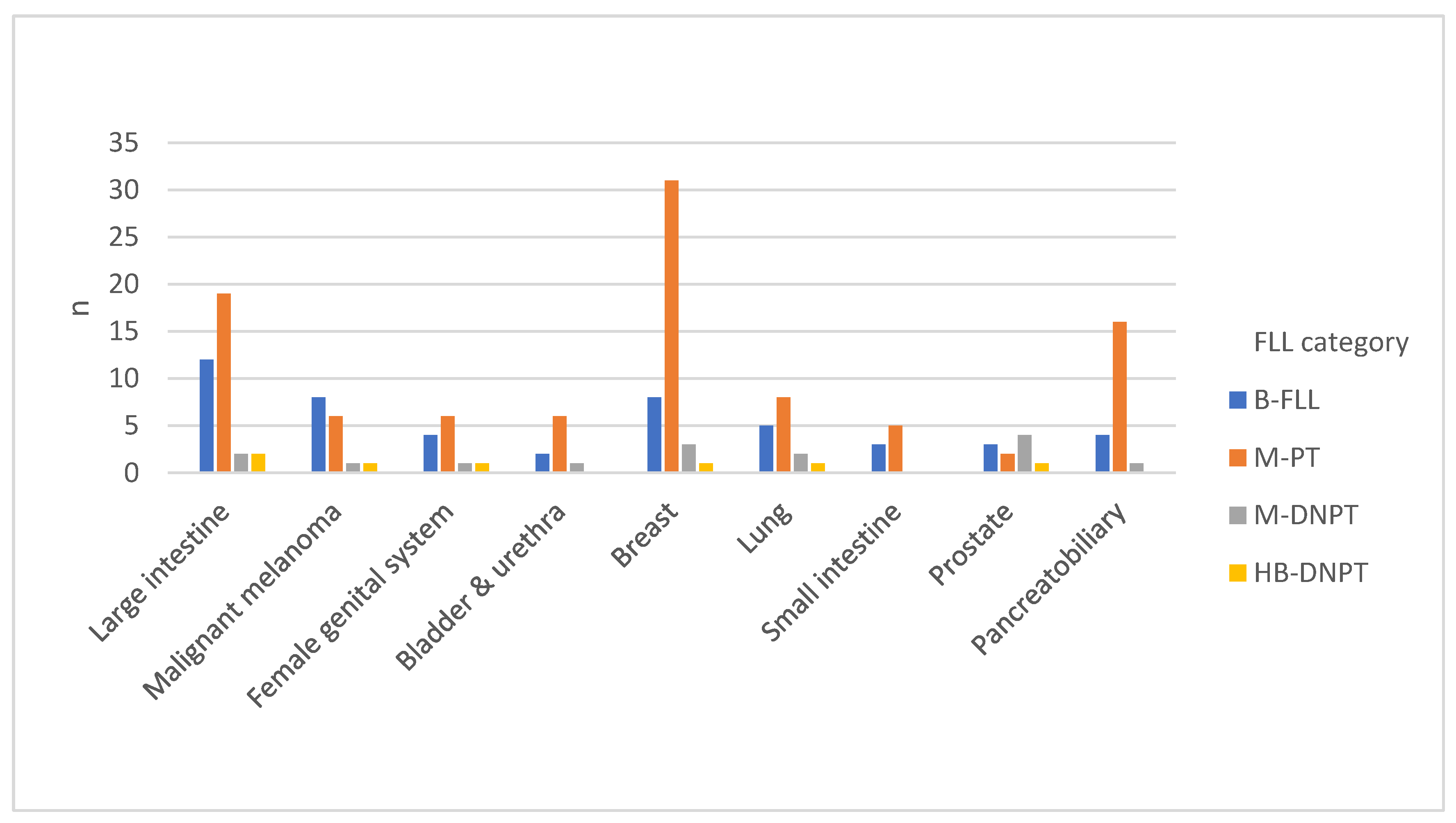

| Primary tumor anatomical site | N | Percentage (%) |

| Breast | 43 | 21.8 |

| Large intestine | 35 | 17.3 |

| Pancreatobiliary | 21 | 9.9 |

| Skin | 16 | 7.9 |

| Lung | 16 | 7.4 |

| Female reproductive organs | 12 | 5.4 |

| Prostate | 10 | 5.0 |

| Small intestine | 8 | 4.5 |

| Esophagus | 9 | 4.5 |

| Bladder & urethra | 9 | 4.5 |

| Head & neck | 7 | 4.0 |

| Stomach | 7 | 3.0 |

| Kidney | 5 | 2.5 |

| Others | 4 | 2.5 |

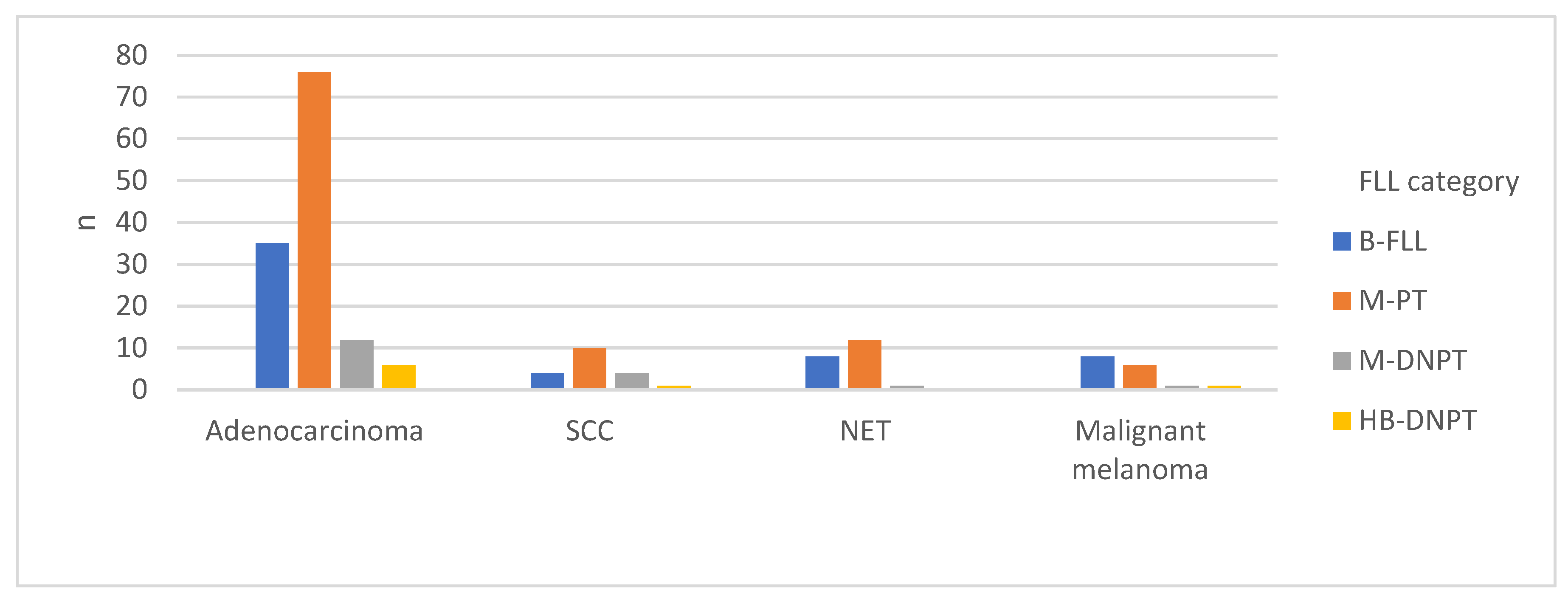

| Primary tumor histological subtype | N | Percentage (%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 129 | 63.9 |

| NET | 21 | 10.4 |

| SCC | 19 | 9.4 |

| Malignant melanoma | 16 | 7.9 |

| TCC | 9 | 4.5 |

| Sarcoma | 6 | 3.0 |

| GCT | 1 | 0.5 |

| MANEC | 1 | 0.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).