Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

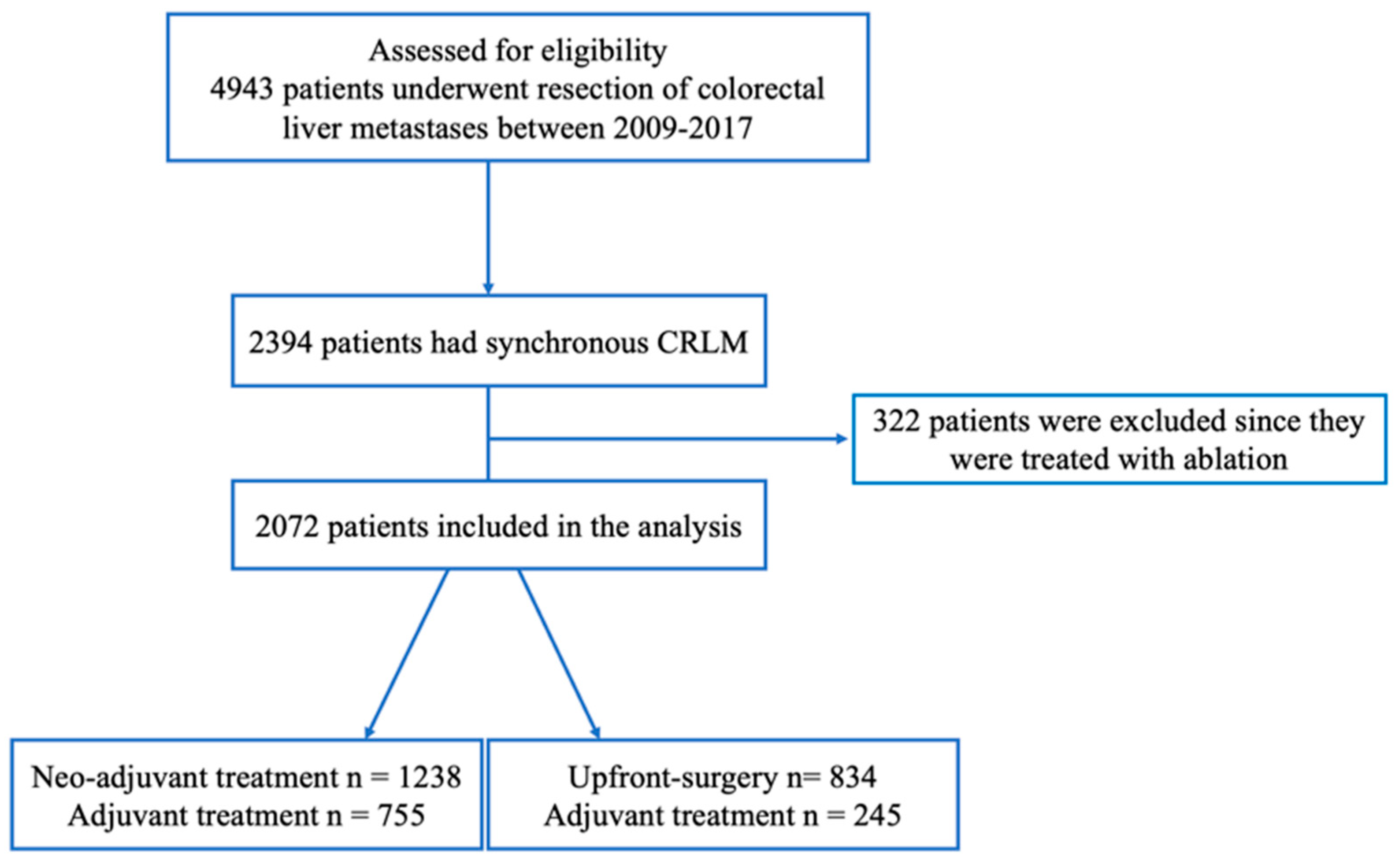

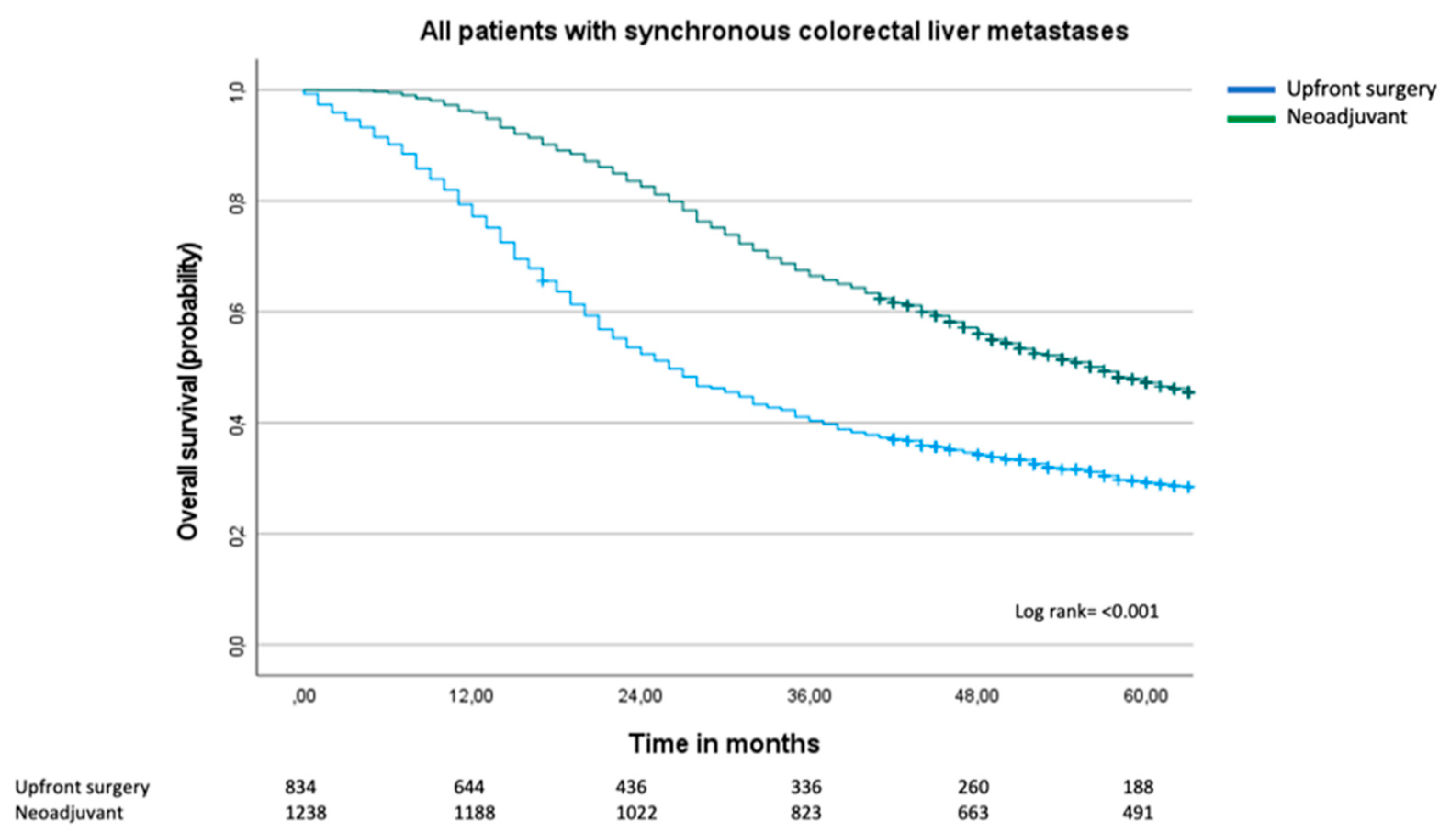

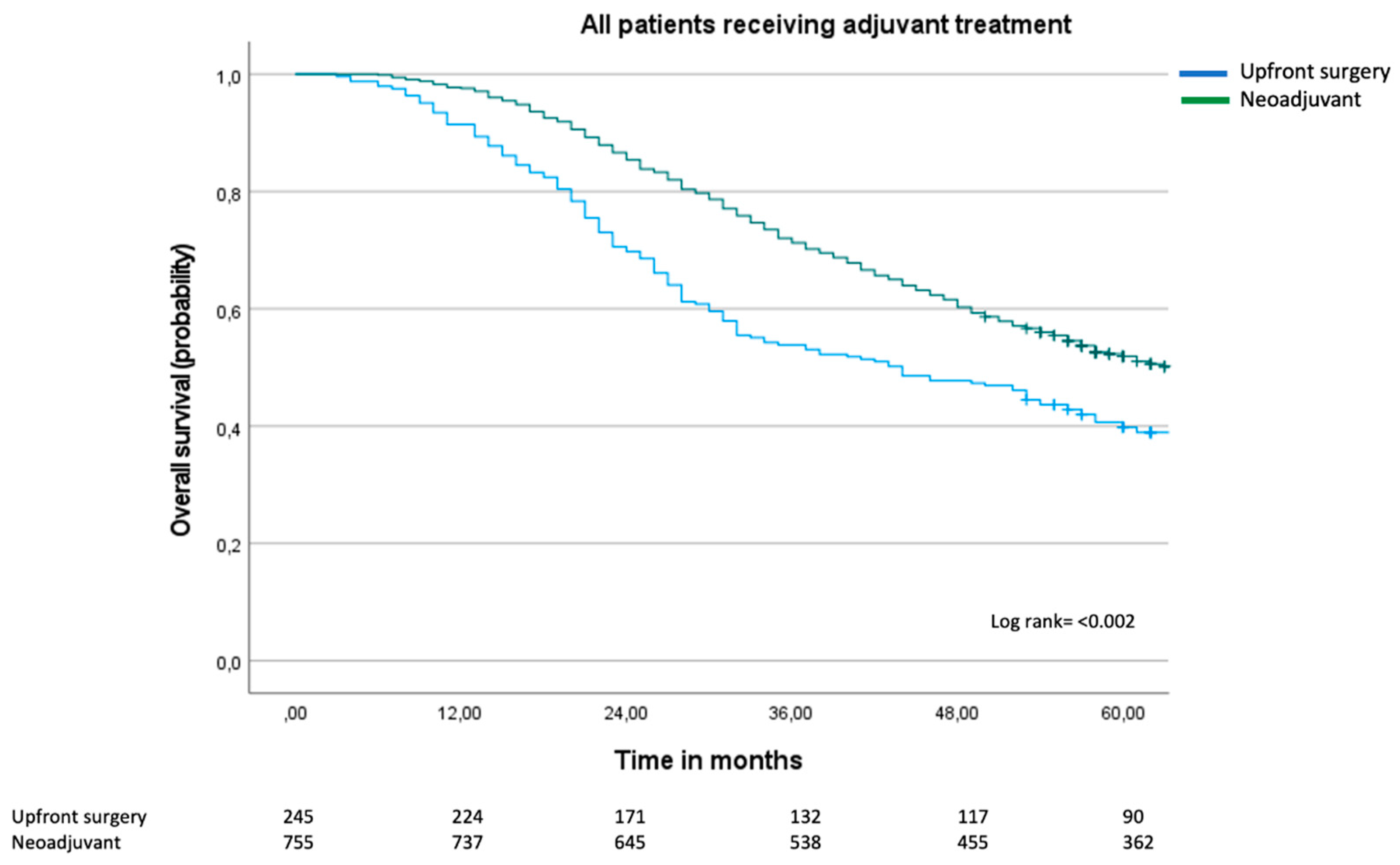

There is still no consensus as to whether patients with upfront resectable synchronous colorectal liver metastases (sCRLM) should receive neoadjuvant treatment prior to liver surgery. Two randomized controlled trials have assessed the role of peri-operative chemotherapy in sCRLM; neither have shown a survival benefit in the neoadjuvant group. The aim of this population-based study was to examine overall survival in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and hepatectomy compared to patients who had upfront surgery. This is a retrospective observational study between 2009 and 2017 containing data extracted from two Swedish national registries. Descriptive statistics and Cox regression analyses were employed. Results: 2072 patients with sCRLM were treated with liver surgery between 2009-2017. A majority (n=1238, 60%) were treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 834 patients (40%) had upfront surgery. Patients in the upfront surgery group were older (median age 70 compared to 65 years, p=<0.001). Median overall survival in the upfront surgery group was 26 months (95% CI 23-29 months) compared to 57 months (95% CI 42-48 months) in the neoadjuvant group, log rank p=<0.001. In the multivariable Cox regression analysis, age ³70 years (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.25-1.70), T category of primary cancer (HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.09-1.84), lymphatic spread of primary cancer (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.41-1.99) and number of liver metastases (six or more metastases resulted in HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.38-3.01), negatively influenced overall survival. By contrast, adjuvant therapy was protective (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0-69-0.94), whereas neoadjuvant treatment compared to upfront surgery did not influence overall survival (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.86-1.26). In conclusion, neoadjuvant treatment in sCRLM did not confer a survival benefit compared to upfront surgery.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. National Quality Registries

2.3. Work-Up of Patients

2.4. Permissions

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Surgical Results and Morbidity

3.2. Overall Survival and Cox Regression Analysis

3.3. Sub-Group Analyses

3.4. Supplemental Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Hackl, C.; Neumann, P.; Gerken, M.; Loss, M.; Klinkhammer-Schalke, M.; Schlitt, H.J. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases in Germany: a ten-year population-based analysis of 5772 cases of primary colorectal adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2014, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araujo, R.L.; Gönen, M.; Herman, P. Chemotherapy for patients with colorectal liver metastases who underwent curative resection improves long-term outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015, 22, 3070–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandi G, De Lorenzo S, Nannini M, Curti S, Ottone M, Dall'Olio FG, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colorectal cancer metastases: Literature review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Xiong, B. Peri-operative chemotherapy for patients with resectable colorectal hepatic metastasis: A meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015, 41, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC Intergroup trial 40983): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008, 371, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlinger B, Sorbye H, Glimelius B, Poston GJ, Schlag PM, Rougier P; et al. Perioperative FOLFOX4 chemotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone for resectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer (EORTC 40983): long-term results of a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2013, 14, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanemitsu Y, Shimizu Y, Mizusawa J, Inaba Y, Hamaguchi T, Shida D; et al. Hepatectomy Followed by mFOLFOX6 Versus Hepatectomy Alone for Liver-Only Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (JCOG0603): A Phase II or III Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2021, JCO2101032.

- Primrose J, Falk S, Finch-Jones M, Valle J, O'Reilly D, Siriwardena A; et al. Systemic chemotherapy with or without cetuximab in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis: the New EPOC randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primrose, J.N. Cetuximab for resectable colorectal liver metastasis: new EPOC trial--author's reply. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruhling, P.; Urdzik, J.; Isaksson, B. Chemotherapy in patients with a solitary colorectal liver metastasis - A nationwide propensity score matched study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodeda K, Nathanaelsson L, Jung B, Olsson H, Jestin P, Sjovall A; et al. Population-based data from the Swedish Colon Cancer Registry. Br J Surg. 2013, 100, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2024. Available online: https://cancercentrum.se/samverkan/cancerdiagnoser/lever-och-galla/statistik/.

- Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Azad N, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK; et al. Rectal Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022, 20, 1139–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE guideline NG151, 2020. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng151 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, Arnold D, Normanno N, Taïeb J; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitry E, Fields AL, Bleiberg H, Labianca R, Portier G, Tu D; et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy after potentially curative resection of metastases from colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of two randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008, 26, 4906–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino M, Primavesi F, Syn N, Dorcaratto D, de la Hoz Rodríguez Á, Dupré A; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Perioperative Versus Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Resectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: An International Multicentre Propensity-Score Matched Analysis with Stratification by Contemporary Risk-Scoring. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29, 6829–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.; Chee, C.E. Perioperative Chemotherapy for Liver Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng C, Yoshino T, Ruíz-García E, Mostafa N, Cann CG, O'Brian B; et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2024, 404, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatavicius P, Oberkofler CE, Chapman WC, DeMatteo RP, Clary BM, D'Angelica MI; et al. Choices of Therapeutic Strategies for Colorectal Liver Metastases Among Expert Liver Surgeons: A Throw of the Dice? Annals of surgery 2020, 272, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H. Real-world Evidence versus Randomized Controlled Trial: Clinical Research Based on Electronic Medical Records. J Korean Med Sci. 2018, 33, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazha, B.; Yang, J.C.; Owonikoko, T.K. Benefits and limitations of real-world evidence: lessons from EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, C.M.; Berry, S.R. Perioperative Chemotherapy for Resectable Liver Metastases in Colorectal Cancer: Do We Have a Blind Spot? J Clin Oncol. 2021, JCO2101972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. Patients N= 2072 |

Neoadjuvant N=1238 |

Upfront surgery N=834 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) Median (IQR) Age >70 |

66 (58-72) 747 (36) |

65 (57-70) 343 (28) |

70 (60-71) 404 (48) |

<0.001 <0.001 |

|

Sex Men Women ASA 1 2 3 4 Missing T category of primary cancer T1 T2 T3 T4 Tx/missing 592 Lymphatic spread of primary cancer N0 N1 N2 Nx/missing Tumor diameter (mm) Median (IQR) |

1269 (61) 803 (39) 289 (17) 947 (57) 419 (25) 21 (1) 396 21 (1) 137 (8) 1045 (62) 476 (29) 393 503 (30) 642 (38) 557 (32) 370 20 (13-33) |

765 (62) 473 (38) 206 (19) 631 (57) 249 (23) 12 (1) 140 13 (1) 98 (9) 692 (64) 284 (26) 151 308 (28) 449 (40) 356 (32) 125 20 (14-35) |

504 (60) 330 (40) 83 (14) 316 (55) 170 (29) 9 (2) 256 8 (1) 39 (7) 353 (60) 192 (32) 242 195 (33) 193 (33) 201 (34) 245 20 (13-30) |

0.282 0.006 0.027 0.006 0.019 |

| Number of liver metastases | ||||

| 1 2 3-5 6 >6 Missing |

666 (35) 372 (19) 502 (26) 253 (13) 118 (6) 161 |

328 (28) 249 (21) 373 (31) 181 (15) 56 (5) 51 |

338 (47) 123 (17) 129 (18) 72 (10) 62 (9) 110 |

<0.001 |

| Neoadjuvant N=1238 |

Upfront surgery N=834 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Emergency primary cancer operation Type of colorectal resection Rectal resection Left colectomy Right colectomy Colectomy, other Unspecified Laparotomy only |

144 (12) 392 (32) 423 (34) 232 (19) 62 (5) 117 (10) 42 (1) |

99 (12) 141 (17) 195 (23) 194 (23) 37 (4) 225 (27) 42 (5) |

0.059 <0.001 |

|

Major hepatectomy 3 or more liver segments Intraoperative blood loss Median (IQR) Response on neoadjuvant treatment Complete/partial Stable disease Progress Unclear Liver resection R0 R1 Unclear Missing Post-operative complications Re-admission within 30 days Clavien Dindo 3a Clavien Dindo 3b Clavien Dindo 4a Clavien Dindo 4b Clavien Dindo 5 |

527 (43) 600 (300-1100) 481 (39) 98 (8) 34 (3) 625 (50) 898 (81) 125 (11) 89 (8) 126 81 (7) 87 (7) 41 (3) 15 (1) 4 (0) 5 (0) |

50 (6) 300 (125-475) N/A 298 (80) 36 (10) 37 (10) 463 36 (4) 25 (3) 16 (2) 5 (1) 2 (0) 2 (0) |

<0.001 0.083 0.390 <0.001 <0.001 |

| a. Cox regression analyses and overall survival. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable HR, 95% CI |

P value | Multivariable HR, 95% CI |

P value | |||||

|

Age (years) <70 ≥70 Gender Women Men ASA 1-2 3-4 |

Reference 1.38 (1.26-1.56) Reference 1.05 (0.90-1.11) Reference 1.26 (1.09-1.46) |

<0.001 0.931 0.002 |

Reference 1.46 (1.25-1.70) Reference 1.03 (0.89-1.19) Reference 1.16 (0.98-1.38) |

0.007 0.719 0.087 |

||||

|

T category of primary cancer T1-T2 T3-T4 Lymphatic spread of primary cancer N0 N1-N2 Number of liver metastases 1 2 3-5 6 >6 Chemotherapy Upfront surgery Neoadjuvant No adjuvant Adjuvant |

Reference 1.91 (1.53-2.39) Reference 1.89 (1.64-2.16) Reference 1.33 (1.13-1.56) 1.40 (1.21-1.63) 1.80 (1.51-2.15) 3.04 (2.44-3.79) Reference 0.56 (0.51-0.63) Reference 0.62 (0.55-0.69) |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 |

Reference 1.41 (1.09-1.84) Reference 1.68 (1.41-1.99) 1.52 (1.26-1.84) 1.38 (1.14-1.66) 1.54 (1.22-1.96) 2.05 (1.38-3.01) 1.04 (0.86-1.26) 0.80 (0.69-0.94) |

0.010 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.681 0.007 |

||||

| b. Cox regression model for overall survival for patients with six or more than six liver metastases. | ||||||||

|

Univariable HR, 95% CI |

P value |

Multivariable HR, 95% CI |

P value | |||||

|

Age (years) <70 ≥70 Gender Women Men ASA 1-2 3-4 |

Reference 1.61 (1.25-2.07) Reference 0.99 (0.78-1.25) Reference 1.33 (0.95-1.86) |

<0.001 0.928 0.094 |

Reference 1.93 (1.30-2.87) Reference 1.21 (0.82-1.76) Reference 1.58 (1.06-2.36) |

0.002 0.335 0.026 |

||||

|

T category of primary cancer T1-T2 T3-T4 Lymphatic spread of primary cancer N0 N1-N2 Chemotherapy Upfront surgery Neoadjuvant No adjuvant Adjuvant |

Reference 3.81 (1.87-7.73) Reference 1.94 (1.33-2.83) Reference 0.301 (0.24-0.38) Reference 0.70 (0.54-0.90) |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.005 |

Reference 3.30(1.53-7.11) Reference 1.34 (0.82-2.17) Reference 1.53 (0.67-3.53) Reference 1.06 (0.72-1.54) |

0.002 0.241 0.314 0.778 |

||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).