Submitted:

17 August 2023

Posted:

18 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

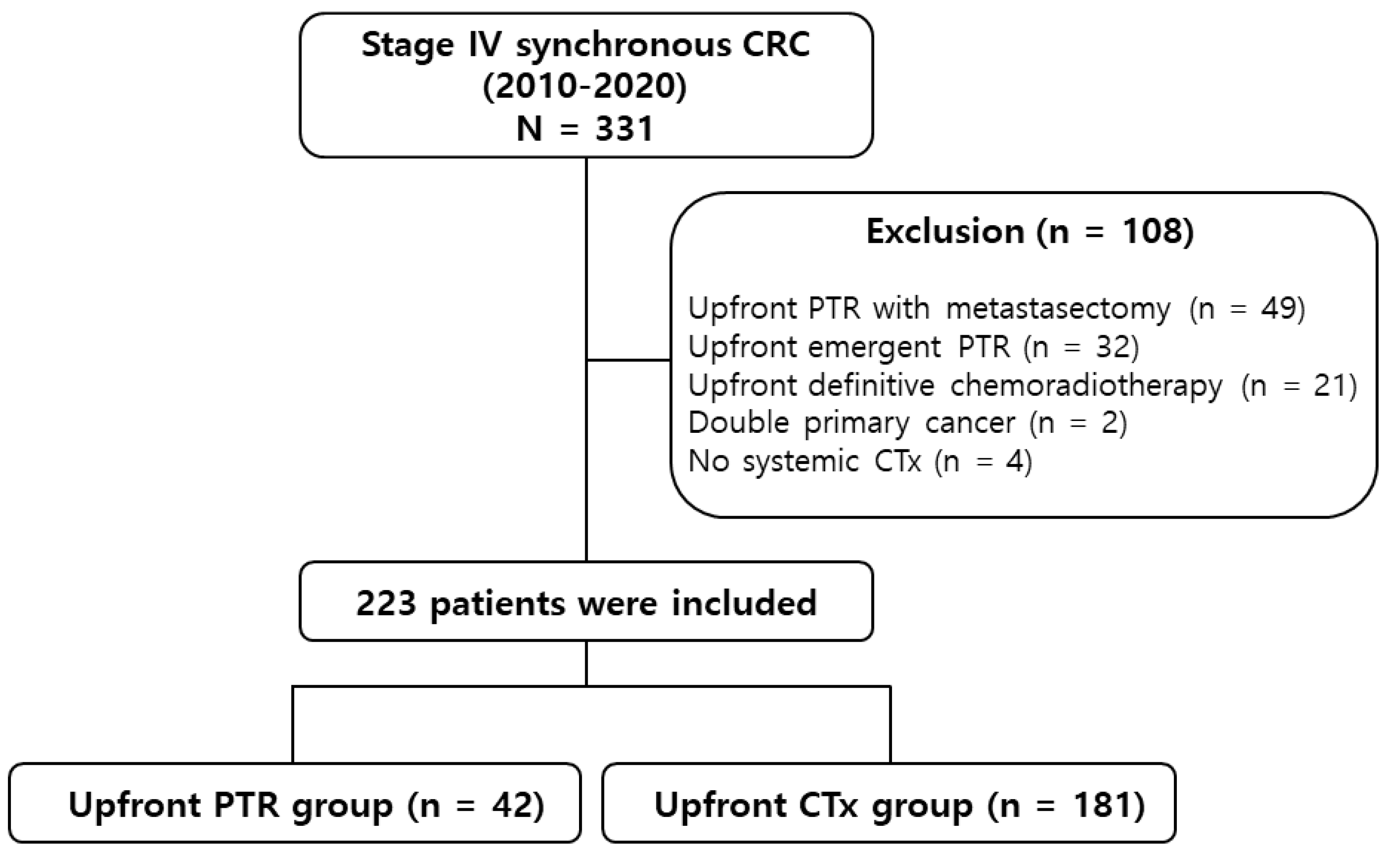

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics statements

2.2. Study design and patients

2.3. Treatment and assessment

2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

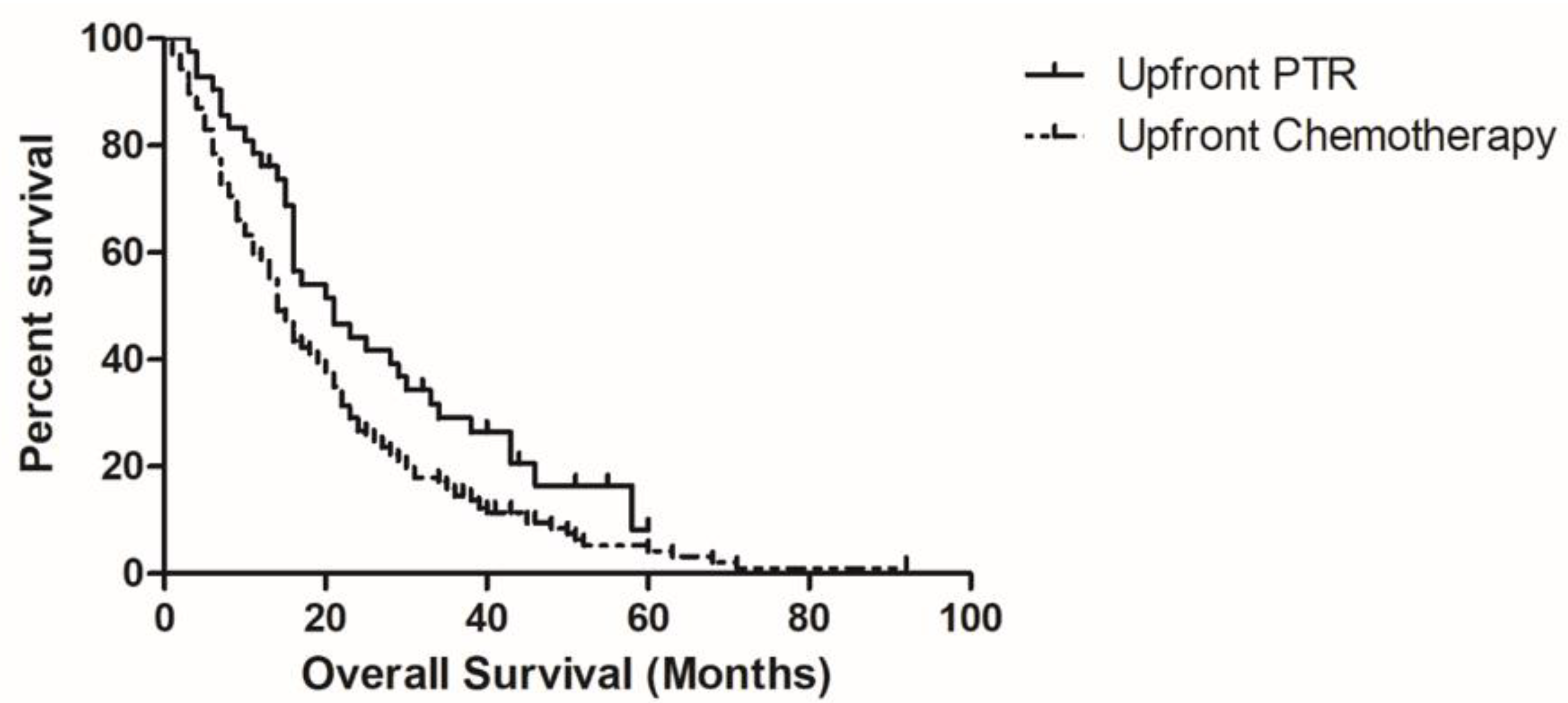

3.2. Variables associated with OS

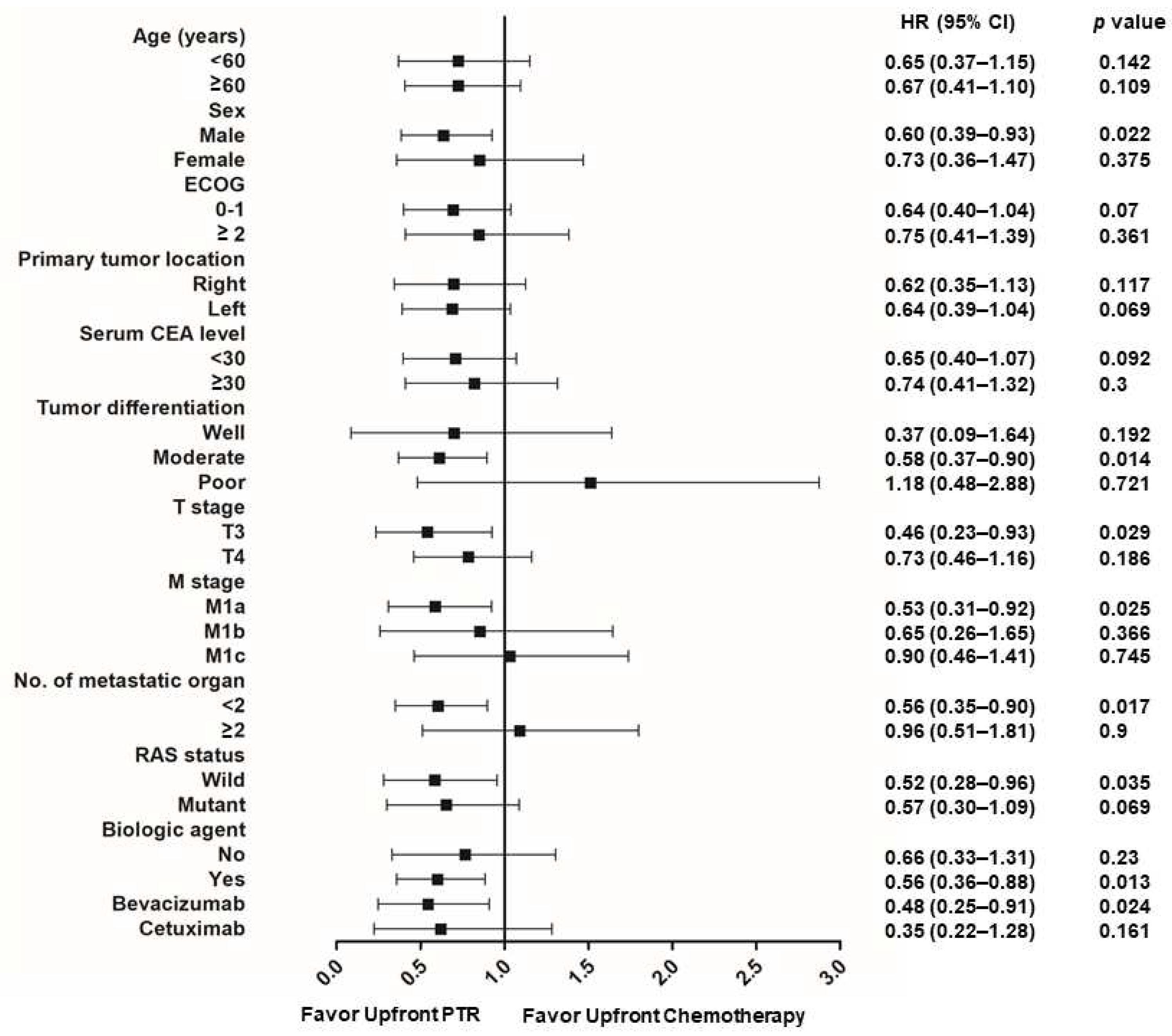

3.3. Subgroup analysis favors upfront PTR

3.4. Primary tumor-related complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Venook, A.P.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Lenz, H.-J.; Innocenti, F.; Fruth, B.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Schrag, D.; Greene, C.; O’Neil, B.H.; Atkins, J.N.; et al. Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined With Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on Overall Survival in Patients With KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mun, J.Y.; Kim, J.E.; Yoo, N.; Cho, H.M.; Kim, H.; An, H.J.; Kye, B.H. Survival Outcomes after Elective or Emergency Surgery for Synchronous Stage IV Colorectal Cancer. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Becerra, A.Z.; Aquina, C.T.; Hensley, B.J.; Justiniano, C.F.; Boodry, C.; Swanger, A.A.; Arsalanizadeh, R.; Noyes, K.; Monson, J.R.; et al. Emergent Colectomy Is Independently Associated with Decreased Long-Term Overall Survival in Colon Cancer Patients. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: Official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2017, 21, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.Y.; Oskarsson, T.; Acharyya, S.; Nguyen, D.X.; Zhang, X.H.; Norton, L.; Massagué, J. Tumor self-seeding by circulating cancer cells. Cell 2009, 139, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, M.G.; Sloots, C.E.; van der Wilt, G.J.; Ruers, T.J. Management of patients with asymptomatic colorectal cancer and synchronous irresectable metastases. Ann Oncol 2008, 19, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, H.; Hinoi, T.; Shimomura, M.; Egi, H.; Hattori, M.; Ishizaki, Y.; Adachi, T.; Saito, Y.; Miguchi, M.; Sawada, H.; et al. Up-front systemic chemotherapy is a feasible option compared to primary tumor resection followed by chemotherapy for colorectal cancer with unresectable synchronous metastases. World J Surg Oncol 2015, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloca, G.A.; Venturino, A.; Guarneri, D. Primary tumor resection in patients with unresectable colorectal cancer with synchronous metastases could improve the activity of poly-chemotherapy: A trial-level meta-analysis. Surgical oncology 2022, 44, 101820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, A.P.; Buettner, P.G.; Ho, Y.H. Meta-analysis of survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer managed with surgical resection versus chemotherapy alone. World journal of surgery 2010, 34, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Peter, M.B.; Dent, J.; Scott, N.A. Palliative excisional surgery for primary colorectal cancer in patients with incurable metastatic disease. Is there a survival benefit? A systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2012, 14, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, C.; Burke, J.P.; Barry, M.; Kalady, M.F.; Calvin Coffey, J. A meta-analysis to determine the effect of primary tumor resection for stage IV colorectal cancer with unresectable metastases on patient survival. Annals of surgical oncology 2014, 21, 3900–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, I.; Warschkow, R.; Worni, M.; Cerny, T.; Ulrich, A.; Schmied, B.M.; Güller, U. Prognostic Relevance of Palliative Primary Tumor Removal in 37,793 Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Population-Based, Propensity Score-Adjusted Trend Analysis. Ann Surg 2015, 262, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Hu, W.H.; Liu, C.C.; Chen, H.H. Meta-analysis of outcomes of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer managed with chemotherapy/radiochemotherapy with and without primary tumor resection. Onco Targets Ther 2016, 9, 7059–7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, G.W.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.R. Meta-analysis of oncologic effect of primary tumor resection in patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer in the era of modern systemic chemotherapy. Ann Surg Treat Res 2018, 95, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harji, D.P.; Vallance, A.; Selgimann, J.; Bach, S.; Mohamed, F.; Brown, J.; Fearnhead, N. A systematic analysis highlighting deficiencies in reported outcomes for patients with stage IV colorectal cancer undergoing palliative resection of the primary tumour. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018, 44, 1469–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, U.; Stöß, C.; Stecher, L.; Wilhelm, D.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. Meta-analysis of outcomes following resection of the primary tumour in patients presenting with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 2018, 105, 784–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterpetti, A.V.; Costi, U.; D’Ermo, G. National statistics about resection of the primary tumor in asymptomatic patients with Stage IV colorectal cancer and unresectable metastases. Need for improvement in data collection. A systematic review with meta-analysis. Surgical oncology 2020, 33, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanemitsu, Y.; Shitara, K.; Mizusawa, J.; Hamaguchi, T.; Shida, D.; Komori, K.; Ikeda, S.; Ojima, H.; Ike, H.; Shiomi, A.; et al. Primary Tumor Resection Plus Chemotherapy Versus Chemotherapy Alone for Colorectal Cancer Patients With Asymptomatic, Synchronous Unresectable Metastases (JCOG1007; iPACS): A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2021, 39, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Kruijssen, D.E.W.; Elias, S.G.; Vink, G.R.; van Rooijen, K.L.; t Lam-Boer, J.; Mol, L.; Punt, C.J.A.; de Wilt, J.H.W.; Koopman, M. Sixty-Day Mortality of Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Randomized to Systemic Treatment vs Primary Tumor Resection Followed by Systemic Treatment: The CAIRO4 Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA surgery 2021, 156, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbari, N.N.; Biondo, S.; Feißt, M.; Bruckner, T.; Rossion, I.; Luntz, S.; Bork, U.; Büchler, M.W.; Folprecht, G.; Kieser, M.; et al. Randomized clinical trial on resection of the primary tumor versus no resection prior to systemic therapy in patients with colon cancer and synchronous unresectable metastases. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022, 40, LBA3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, N.N.; Folkert, M.R.; Aguilera, T.A.; Beg, M.S.; Kazmi, S.A.; Sanjeevaiah, A.; Zeh, H.J.; Farkas, L. Trends in Primary Surgical Resection and Chemotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer, 2000-2016. American journal of clinical oncology 2020, 43, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xia, Z.; Jia, X.; Chen, K.; Li, D.; Dai, Y.; Tao, M.; Mao, Y. Primary Tumor Resection Is Associated with Improved Survival in Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: An Instrumental Variable Analysis. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 16516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.A.; Huh, J.W.; Park, Y.A.; Cho, Y.B.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, W.Y.; Chun, H.K. The role of palliative resection for asymptomatic primary tumor in patients with unresectable stage IV colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2014, 57, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, R.; Chen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, T. Primary Tumour Resection Could Improve the Survival of Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Receiving Bevacizumab-Containing Chemotherapy. Cell Physiol Biochem 2016, 39, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, A.; Yamazaki, K.; Kinugasa, Y.; Tsukamoto, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Shiomi, A.; Tsushima, T.; Yokota, T.; Todaka, A.; Machida, N.; et al. Influence of primary tumor resection on survival in asymptomatic patients with incurable stage IV colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol 2014, 19, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poultsides, G.A.; Servais, E.L.; Saltz, L.B.; Patil, S.; Kemeny, N.E.; Guillem, J.G.; Weiser, M.; Temple, L.K.; Wong, W.D.; Paty, P.B. Outcome of primary tumor in patients with synchronous stage IV colorectal cancer receiving combination chemotherapy without surgery as initial treatment. Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27, 3379–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, B.; Kaplan, M.A.; Berk, V.; Tufan, G.; Benekli, M.; Isikdogan, A.; Ozkan, M.; Coskun, U.; Buyukberber, S. Bevacizumab-containing chemotherapy is safe in patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer and a synchronous asymptomatic primary tumor. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013, 43, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Chung, M.; Ahn, J.B.; Kim, C.W.; Cho, M.S.; Shin, S.J.; Baek, S.J.; Hur, H.; Min, B.S.; Baik, S.H.; et al. Clinical significance of primary tumor resection in colorectal cancer patients with synchronous unresectable metastasis. J Surg Oncol 2014, 110, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebbutt, N.C.; Norman, A.R.; Cunningham, D.; Hill, M.E.; Tait, D.; Oates, J.; Livingston, S.; Andreyev, J. Intestinal complications after chemotherapy for patients with unresected primary colorectal cancer and synchronous metastases. Gut 2003, 52, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Wong, H.-L.; Tacey, M.; Tie, J.; Wong, R.; Lee, M.; Nott, L.; Shapiro, J.; Jennens, R.; Turner, N.; et al. The impact of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer with an intact primary tumor: Results from a large prospective cohort study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017, 13, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, L.; Coşkun, H.; Dane, F.; Karabulut, B.; Karaağaç, M.; Çabuk, D.; Karabulut, S.; Aykan, N.F.; Doruk, H.; Avcı, N.; et al. Kras-mutation influences outcomes for palliative primary tumor resection in advanced colorectal cancer-a Turkish Oncology Group study. Surgical oncology 2018, 27, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida, D.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ochiai, H.; Tsukamoto, S.; Takashima, A.; Boku, N.; Kanemitsu, Y. Prognostic Impact of Palliative Primary Tumor Resection for Unresectable Stage 4 Colorectal Cancer: Using a Propensity Score Analysis. Annals of surgical oncology 2016, 23, 3602–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawamura, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Yamazaki, H.; Honda, M.; Kono, K.; Konno, S.; Fukuhara, S.; Yamamoto, Y. Impact of Primary Tumor Resection on Mortality in Patients with Stage IV Colorectal Cancer with Unresectable Metastases: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. World journal of surgery 2021, 45, 3230–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrand, F.; Malka, D.; Bourredjem, A.; Allonier, C.; Bouché, O.; Louafi, S.; Boige, V.; Mousseau, M.; Raoul, J.L.; Bedenne, L.; et al. Impact of primary tumour resection on survival of patients with colorectal cancer and synchronous metastases treated by chemotherapy: Results from the multicenter, randomised trial Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive 9601. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2013, 49, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruo, L.; Gougoutas, C.; Paty, P.B.; Guillem, J.G.; Cohen, A.M.; Wong, W.D. Elective bowel resection for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: Prognostic variables for asymptomatic patients. J Am Coll Surg 2003, 196, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faron, M.; Pignon, J.P.; Malka, D.; Bourredjem, A.; Douillard, J.Y.; Adenis, A.; Elias, D.; Bouché, O.; Ducreux, M. Is primary tumour resection associated with survival improvement in patients with colorectal cancer and unresectable synchronous metastases? A pooled analysis of individual data from four randomised trials. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2015, 51, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, G.; Renouf, D.J.; Chan, M.; Kennecke, H.F.; Lim, H.J.; Brown, C.; Cheung, W.Y. Association between palliative resection of the primary tumor and overall survival in a population-based cohort of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Annals of surgical oncology 2014, 21, 3917–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, S.; Hayama, T.; Yamada, H.; Nozawa, K.; Matsuda, K.; Miyata, H.; Yoneyama, S.; Tanaka, T.; Tanaka, J.; Kiyomatsu, T.; et al. Prognostic impact of primary tumor resection and lymph node dissection in stage IV colorectal cancer with unresectable metastasis: A propensity score analysis in a multicenter retrospective study. Annals of surgical oncology 2014, 21, 2949–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Han, S.W.; Oh, D.Y.; Im, S.A.; Kang, G.H.; Chie, E.K.; Ha, S.W.; Jeong, S.Y.; et al. The beneficial effect of palliative resection in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2013, 108, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shida, D.; Boku, N.; Tanabe, T.; Yoshida, T.; Tsukamoto, S.; Takashima, A.; Kanemitsu, Y. Primary Tumor Resection for Stage IV Colorectal Cancer in the Era of Targeted Chemotherapy. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: Official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2019, 23, 2144–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.C.; Wu, C.C.; Su, C.C.; Hsieh, M.C.; Cheng, C.L.; Kao Yang, Y.H. Comparative Effectiveness of Bevacizumab versus Cetuximab in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients without Primary Tumor Resection. Cancers 2022, 14, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, Z.; Phatak, U.R.; Hu, C.Y.; Bailey, C.E.; You, Y.N.; Kao, L.S.; Massarweh, N.N.; Feig, B.W.; Rodriguez-Bigas, M.A.; Skibber, J.M.; et al. Comparative effectiveness of primary tumor resection in patients with stage IV colon cancer. Cancer 2017, 123, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooijen, K.L.; Shi, Q.; Goey, K.K.H.; Meyers, J.; Heinemann, V.; Diaz-Rubio, E.; Aranda, E.; Falcone, A.; Green, E.; de Gramont, A.; et al. Prognostic value of primary tumour resection in synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer: Individual patient data analysis of first-line randomised trials from the ARCAD database. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2018, 91, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.; Fields, A.; Pahwa, P.; Chandra-Kanthan, S.; Zaidi, A.; Le, D.; Haider, K.; Reeder, B.; Leis, A. Surgical Resection of Primary Tumor in Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic Patients With Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: A Canadian Province Experience. Clinical colorectal cancer 2015, 14, e41–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, C.W.; Lim, S.B.; Yu, C.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, T.W.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J.C. Palliative surgery in patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases: A propensity score matching analysis. J Surg Oncol 2014, 109, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Ma, W.J.; Gu, Y.T.; Zhang, T.Q.; Huang, Z.M.; Lu, Z.H.; Gu, Y.K. Primary tumor location as a predictor of the benefit of palliative resection for colorectal cancer with unresectable metastasis. World J Surg Oncol 2017, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jin, S.; Jeon, M.J.; Jung, H.Y.; Byun, S.; Jung, K.; Kim, S.E.; Moon, W.; Park, M.I.; Park, S.J. Survival Benefit of Palliative Primary Tumor Resection Based on Tumor Location in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Single-center Retrospective Study. The Korean journal of gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe chi 2020, 76, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Tian, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Peng, K.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Li, H.; Zhuang, R.; et al. An Analysis of Relationship Between RAS Mutations and Prognosis of Primary Tumour Resection for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 50, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulack, B.C.; Nussbaum, D.P.; Keenan, J.E.; Ganapathi, A.M.; Sun, Z.; Worni, M.; Migaly, J.; Mantyh, C.R. Surgical Resection of the Primary Tumor in Stage IV Colorectal Cancer Without Metastasectomy is Associated With Improved Overall Survival Compared With Chemotherapy/Radiation Therapy Alone. Dis Colon Rectum 2016, 59, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Upfront PTR | Upfront chemotherapy | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 42 (%) | n = 181 (%) | ||

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (range) | 60 (34–84) | 63 (30–82) | 0.264 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 31 (73.8) | 117 (64.6) | 0.259 |

| Female | 11 (26.2) | 64 (35.4) | |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0/1 | 29 (69.0) | 93 (51.4) | 0.038 |

| ≥2 | 13 (31.0) | 88 (48.6) | |

| Primary tumor location | |||

| Right-sided | 17 (40.5) | 46 (25.4) | 0.014 |

| Left-sided | 25 (59.5) | 135 (74.6) | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 13.32 (1.0–594) | 39.47 (0–86,002) | 0.478 |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Well | 4 (9.5) | 20 (11.0) | 0.732 |

| Moderate | 30 (71.4) | 137 (75.7) | |

| Poor | 7 (16.7) | 19 (10.5) | |

| Clinical T stage | |||

| T3 | 13 (31.0) | 100 (55.2) | 0.005 |

| T4 | 29 (69.0) | 81 (44.8) | |

| Clinical N stage | |||

| N0 | 2 (4.8) | 6 (3.3) | 0.757 |

| N1 | 10 (23.8) | 52 (28.7) | |

| N2 | 30 (71.4) | 123 (68.0) | |

| Clinical M stage | |||

| M1a | 21(50.0) | 75 (41.4) | 0.015 |

| M1b | 6 (14.3) | 66 (36.5) | |

| M1c | 15 (35.7) | 40 (22.1) | |

| No. of organ metastasis | |||

| 0 or 1 | 30 (71.4) | 81 (44.8) | 0.002 |

| ≥2 | 12 (28.6) | 100 (55.2) | |

| RAS status | |||

| Wild | 16 (38.1) | 89 (49.2) | 0.707 |

| Mutant | 15 (35.7) | 72 (39.8) | |

| NA | 11 (26.2) | 20 (11.0) | |

| Time to chemotherapy (days) | 50.4 (±5.46) | 17.3 (±1.40) | <0.001 |

| 1st line chemotherapy | |||

| Fluoropyrimidine alone | 5 (11.9) | 1 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Irinotecan doublet | 15 (35.7) | 108 (59.7) | |

| Oxaliplatin doublet | 22 (52.4) | 72 (39.8) | |

| 1st line targeted gent | |||

| Cetuximab | 9 (21.4) | 78 (43.1) | <0.001 |

| Bevacizumab | 13 (31.0) | 70 (38.7) | |

| No | 20 (47.6) | 34 (18.8) | |

| Administration of targeted agent | 29 (69.0) | 153 (84.5) | 0.021 |

| No. of lines of systemic treatment | 2 (1–7) | 2 (1–7) | 0.448 |

| Conversion resection (R0) | 9 (21.4) | 23 (12.7) | 0.004 |

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (≥ 60) | 0.001 | 1.530 (1.118–2.093) | 0.008 |

| Male | 0.160 | 1.239 (0.904–1.699) | 0.183 |

| ECOG ≥ 2 | 0.001 | 1.445 (1.072–1.948) | 0.016 |

| Right-side colon cancer | 0.038 | 1.342 (0.962–1.874) | 0.084 |

| CEA ≥ 30 (ng/mL) | 0.012 | 1.465 (1.066–2.013) | 0.019 |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.031 | 2.218 (1.217–4.040) | 0.009 |

| Clinical T4 stage | 0.782 | ||

| Clinical N1/2 stage | 0.399 | ||

| Clinical M1c stage | 0.148 | 1.595 (1.060–2.400) | 0.025 |

| No. of organ metastasis (≥2) | 0.120 | ||

| RAS mutation | 0.718 | ||

| Administration of targeted agent | 0.003 | 0.569 (0.387–0.837) | 0.004 |

| Upfront PTR | 0.019 | 0.679 (0.454–1.017) | 0.060 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).