1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) imposes a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide, with millions of new cases diagnosed annually. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 data, CRC ranks as the third most common cancer globally, with an incidence of approximately 1.9 million cases and accounting for 9.4% of all cancer-related deaths [

1,

2]. The increasing incidence of CRC has been attributed to an aging population and the widespread adoption of a Western lifestyle.

Lymph node dissection in the surgical treatment of colon cancer (CC) is not only a measure of surgical adequacy but also a critical step for accurate staging and determining the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. However, studies indicate that in approximately 30-50% of resections, this standard is not met, which is associated with lower survival rates [

3,

4]. In some patients, recurrence after curative resection has been linked to residual disease caused by inadequate lymphadenectomy. Although the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend the pathological evaluation of at least 12 lymph nodes, the number of lymph nodes evaluated in clinical studies varies widely, ranging from 7 to 40 [

5,

6]. This wide range poses challenges in determining the optimal number of lymph nodes to be examined. The pathological examination of at least 12 lymph nodes may allow the reclassification of cases initially staged as stage 1–2 to stage 3 [

3,

7]. Using the ratio of metastatic lymph nodes to the total number of lymph nodes examined, independent of the total lymph node count, offers a potential solution to this challenge [

8].

The relationship between the total number of lymph nodes removed and disease-free survival remains controversial [

9,

10]. While some authors confirm this association, others emphasize that survival outcomes are influenced not only by accurate staging but also by the extent of the radical surgical approach [

11,

12]. These ongoing debates highlight the importance of investigating the metastatic lymph node ratio (MLNR).

MLNR is defined as the ratio of metastatic lymph nodes to the total number of lymph nodes retrieved. It is considered a more sensitive prognostic tool compared to the traditional TNM classification system. For example, in two patients with the same number of metastatic lymph nodes but differing total lymph node counts, patients with a higher MLNR are predicted to have worse prognoses, even if they are staged similarly. Therefore, incorporating MLNR into clinical practice for colon cancer could provide a complementary tool to existing staging systems [

13,

14].

This study aims to evaluate the impact of the metastatic lymph node ratio on overall and disease-free survival, thereby shedding light on the prognostic value of MLNR in colon cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective, single-center study was conducted at the General Surgery Department of Hitit University Erol Olçok Training and Research Hospital. Data from all patients aged 18 years or older who underwent surgery for colon cancer between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2022, were reviewed using the hospital's information system. Exclusion criteria included patients with distant organ metastases at the time of diagnosis, those with known oncologic diseases other than newly diagnosed colon cancer, those who underwent palliative surgery, patients with incomplete data, and those under 18 years of age. Additionally, cases with rectal tumors were excluded due to differences in treatment protocols. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hitit University Faculty of Medicine (Protocol No: 2023-60) and the study protocol was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.

A total of 122 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. Data collected included demographic characteristics, tumor location, total and metastatic lymph node counts retrieved during surgery, disease stage, recurrence and mortality status during follow-up, length of hospital stay, chemotherapy treatments, postoperative complications, and follow-up durations.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize categorical variables as frequencies and percentages, while numerical variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median, depending on the distribution. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Relationships between variables were analyzed using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients based on data distribution. Comparisons of numerical variables between study groups were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test for all variables except age, which was analyzed using the Student's t-test based on a Gaussian distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test.

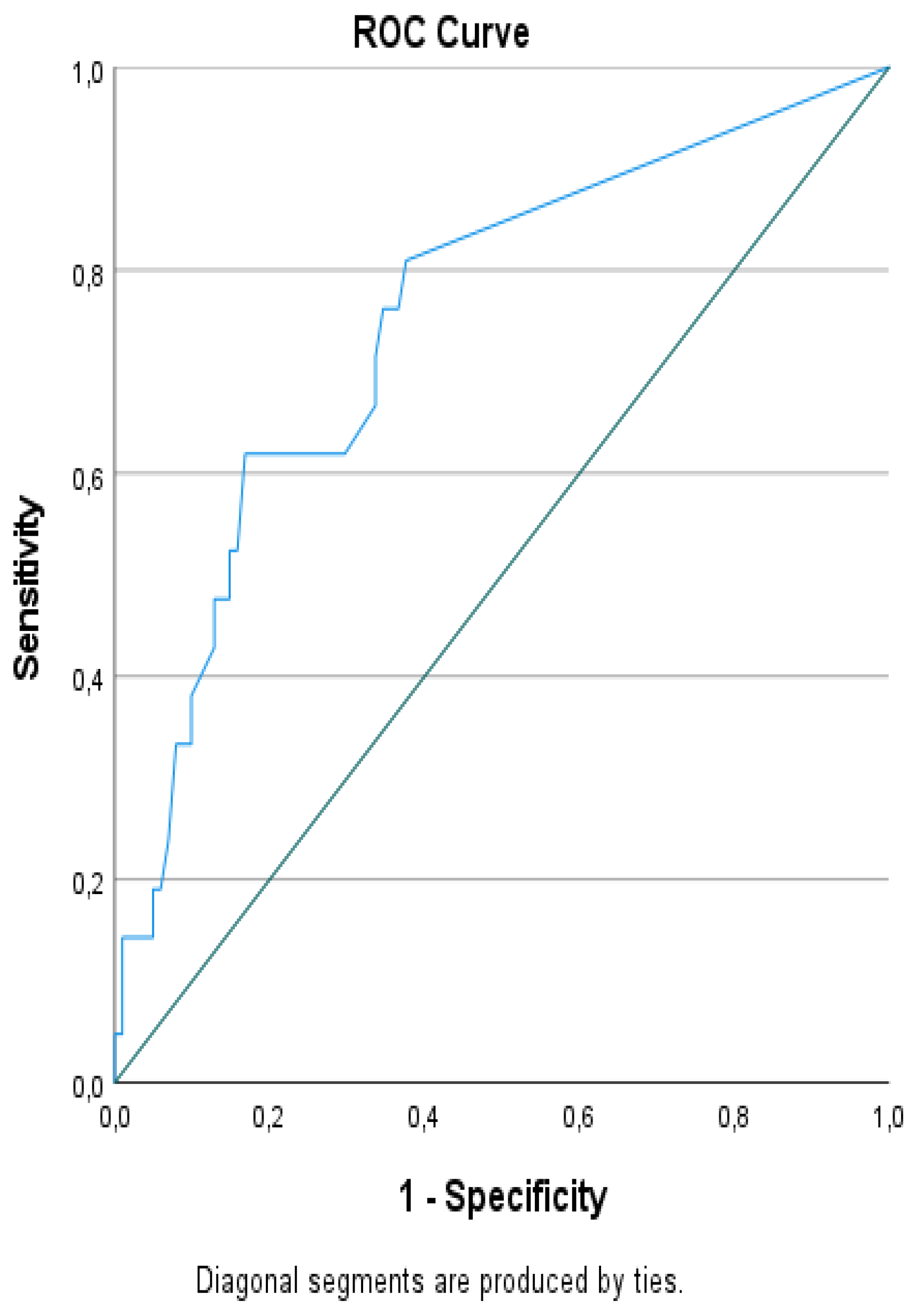

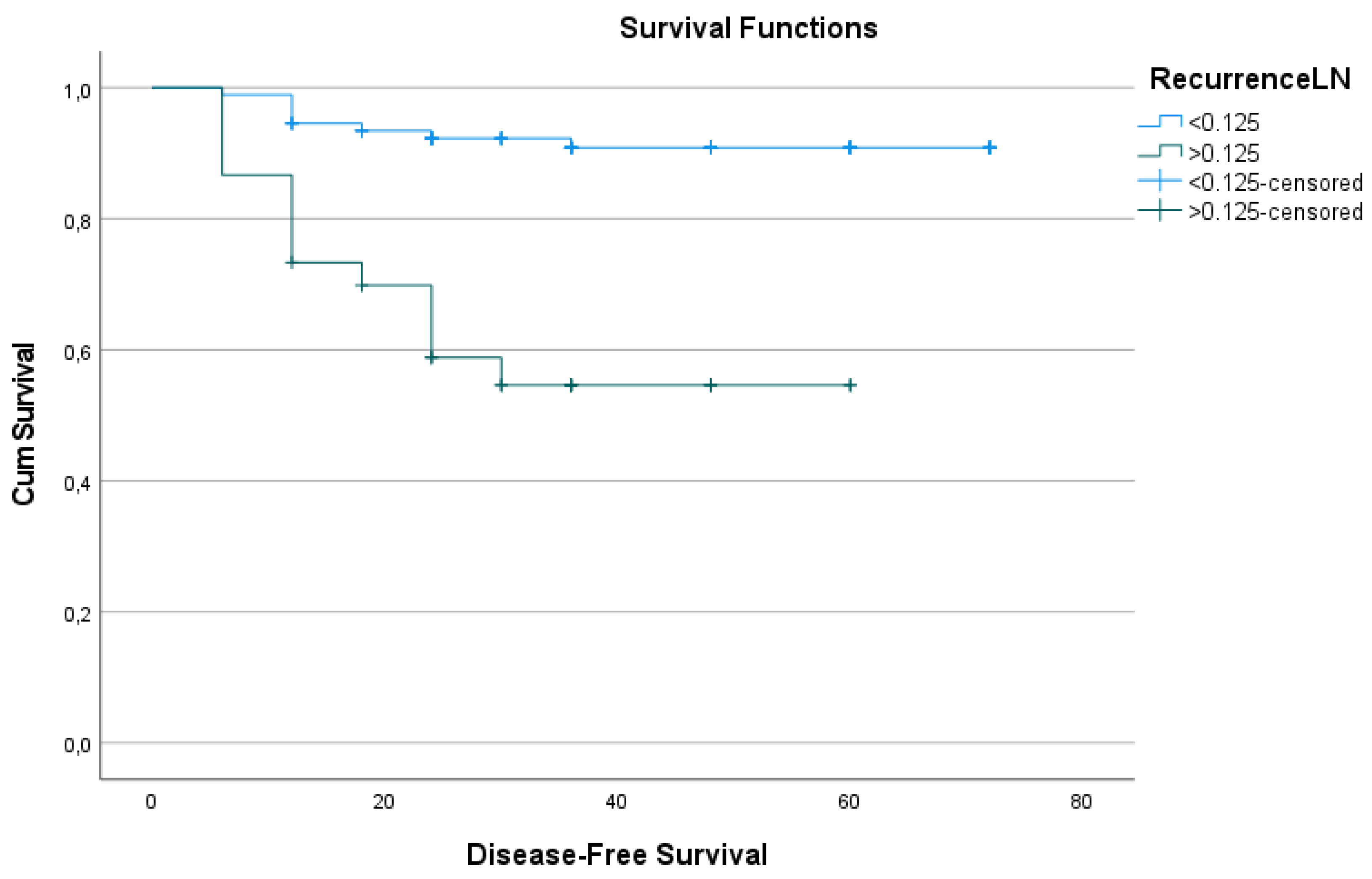

Interactions between variables were examined through binomial logistic regression analysis to evaluate the independent predictive capacity of the metastatic lymph node ratio (MLNR) for recurrence. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were used to assess the discriminative performance of MLNR. Cut-off values for MLNR were determined using the area under the curve (AUC) and the Youden index. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy were calculated based on these cut-off points. Odds ratios corresponding to these cut-off points were also calculated. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to evaluate disease-free survival, and statistical significance between groups was assessed using the Log-Rank test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results:

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The study included a total of 122 patients, of whom 44 (36.07%) were female and 78 (63.93%) were male. The median age was 68.46 ± 10.61 years. Among the patients, 73 (59.84%) underwent elective surgeries. The mean disease-free survival (DFS) duration was 36 months, ranging from 6 to 72 months. During the 60-month follow-up period, 25 patients (20.49%) died. Detailed demographic and clinical variables are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Comparison of Variables by Mortality

Patients were categorized into two groups based on survival status: alive (n=97) and deceased (n=25). While no statistically significant difference was observed in gender distribution (p=0.159), age showed a significant association with mortality. The median age of surviving patients was 66.48 ± 9.56 years, compared to 76.12 ± 11.2 years for those who had died (p<0.001;

Table 1).

Emergency surgery and tumor localization were significantly associated with mortality in univariate analyses (p=0.023 and p=0.009, respectively). However, operation type, histopathology, disease stage, and length of hospital stay did not show significant associations with mortality (p=0.108, p=0.952, p=0.836, and p=0.822, respectively;

Table 1).

Treatment and follow-up factors were also evaluated. Local recurrence, distant metastasis, and overall recurrence were significantly associated with mortality (p<0.001, p=0.008, and p<0.001, respectively). However, adjuvant therapy, the number of malignant lymph nodes, and total lymph node counts were not significant predictors (p=0.697, p=0.082, and p=0.802, respectively;

Table 1). Complications during treatment were not significantly associated with mortality (p=0.507). Contrary to our initial hypothesis, the lymph node ratio (LNR) was not significantly different between survivors and deceased patients (

Table 1).

3.3. Comparison of Variables by Recurrence

Patients were then stratified into recurrence (n=21, 17.21%) and non-recurrence (n=101, 82.79%) groups. Gender distribution did not differ significantly between the groups (p=0.199), but age was a significant factor, with older age being associated with higher recurrence rates (p<0.001). The presence of comorbidities, emergency surgery, tumor localization, and type of surgical intervention showed no significant associations with recurrence (p=0.774, p=0.444, p=0.075, and p=0.170, respectively).

Disease staging was significantly associated with recurrence (p=0.034). Adjuvant therapy was more common in the recurrence group (p=0.015), whereas complications during treatment were not significantly associated with recurrence (p=0.135). Patients without recurrence had significantly longer follow-up durations compared to those with recurrence (p=0.011), likely due to higher mortality rates in the recurrence group (11.88% vs. 61.9%, p<0.001).

The presence of malignant lymph nodes was significantly associated with recurrence (p<0.001). Although the total lymph node count was not a significant predictor (p=0.273), LNR emerged as a highly significant factor in univariate analysis (p<0.001;

Table 1).

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

In a multivariate logistic regression model incorporating age, gender, comorbidities, emergency status, operation type, adjuvant therapy, complications, and LNR, no significant associations were observed for gender, comorbidities, emergency status, operation type, or complications (p=0.247, p=0.281, p=0.588, p=0.608, and p=0.690, respectively). Although age was significant in the univariate analysis, it lost significance in the multivariate model (p=0.716;

Table 1).

Adjuvant chemotherapy and LNR remained independent predictors of recurrence after adjusting for potential confounders. Adjuvant therapy was associated with a reduced risk of recurrence (Exp(B): 0.234, 95% CI: 0.059–0.923, p=0.038), whereas an increased LNR significantly elevated recurrence risk (Exp(B): 13.072, 95% CI: 1.026–166.565, p=0.048). The binomial logistic regression model correctly classified 84.4% of cases (Nagelkerke R² = 0.278, p=0.014).

3.5. Optimal LNR Cut-Off and Survival Analysis

ROC analysis identified an optimal LNR cut-off value of 0.125 for distinguishing between recurrent and non-recurrent cases. At this threshold, LNR showed 61.9% sensitivity, 83.2% specificity, 43.3% positive predictive value (PPV), 91.3% negative predictive value (NPV), and 79.5% overall accuracy (OR: 8.028, 95% CI: 2.885–22.343, p<0.001;

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed a significant difference in DFS between patients with LNR < 0.125 and those with LNR ≥ 0.125. The mean DFS duration for patients with LNR < 0.125 was 42.13 ± 17.9 months, compared to 27.00 ± 15.66 months for those with LNR ≥ 0.125 (p<0.001). Estimated survival durations were 66.9 months and 38.7 months, respectively, for the two groups (p<0.001;

Table 3 and

Figure 2).

The overall mean estimated DFS duration for the entire cohort was 61.93 months.

4. Discussion

The assessment of prognosis in colon cancer (CC) is crucial for determining treatment strategies and long-term disease management. In recent years, many researchers have proposed that the metastatic lymph node ratio (MLNR) could be a prognostic factor in various malignancies, particularly gastrointestinal cancers [15-18]. In colon cancer, the number of metastatic lymph nodes has also been shown to be a significant prognostic factor [

19]. This study evaluates the impact of MLNR on disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) in colon cancer patients, highlighting its potential as an independent predictor of prognosis. Our findings align with existing literature and offer new perspectives.

4.1. Prognostic Significance of MLNR

MLNR emerges as a more sensitive prognostic indicator compared to the metastatic lymph node count in the TNM staging system. A meta-analysis has emphasized the prognostic value of MLNR in colon cancer, noting that patients with a higher MLNR tend to have worse survival outcomes [

20]. The current literature supports the use of lymph node ratio for colon cancer prognosis. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, increased lymph node ratio was associated with reduced OS (HR: 2.36) and DFS (HR: 3.71) [

21]. Similarly, another meta-analysis found significant associations between MLNR and both OS (HR: 1.91) and DFS (HR: 2.75) [

4]. For colon cancer, a 2020 review compiled several studies examining MLNR cut-off values (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.6) and found that exceeding these thresholds led to a decrease in both OS and DFS. Our study proposes an MLNR cut-off of 0.125, especially for stage I-III patients, which could be used in clinical practice. We demonstrated that patients with an MLNR ≥0.125 had a sevenfold higher risk of disease recurrence. Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that patients with lower MLNR had significantly longer DFS (p<0.001), suggesting that MLNR can serve as a risk classifier not only for staging but also for post-treatment follow-up.

4.2. MLNR and TNM Staging

The TNM classification system considers the number of metastatic lymph nodes as one of the main factors determining prognosis. Guidelines recommend examining at least 12 lymph nodes in colon cancer surgery. However, this approach may overlook variations in the total number of lymph nodes examined, which can be influenced by surgeon and pathologist expertise, tumor location, and the urgency of surgery [

23]. Zhang and colleagues reviewed 33 studies analyzing different MLNR cut-off values and concluded that higher MLNR independently predicted survival in colon cancer patients, suggesting its inclusion in future staging systems [

4]. This finding is supported by numerous studies showing that MLNR is a better prognostic factor than the N stage [

21,

24]. However, some studies have found that MLNR performs similarly to or less effectively than the N stage [

25,

26,

27]. Some researchers have proposed hybrid staging systems integrating MLNR with the TNM classification, which have shown superior outcomes [

20,

28,

29]. For example, Wang and colleagues demonstrated that patients classified as stage IIIB by TNM but with MLNR >30% had survival rates worse than those with MLNR ≤30%, more closely resembling stage IIIC patients. These findings suggest that integrating MLNR into TNM staging could improve prognosis prediction.

4.3. Surgical and Pathological Factors Affecting Mortality

In our study, we found that emergency surgery and tumor localization significantly influenced mortality (p=0.023 and p=0.009, respectively). However, the type of surgery, histopathology, disease stage, and duration of hospitalization were not significantly associated with survival. Although the total lymph node count did not correlate with survival (p=0.273), MLNR was found to be a significant prognostic factor (p<0.001). This suggests that MLNR should be included as a complementary metric in the staging systems alongside TNM.

4.4. Adjuvant Chemotherapy and MLNR

Adjuvant chemotherapy is a key component of colon cancer treatment and significantly impacts prognosis. The lymph node ratio (LNR) is an important determinant of both disease progression and adjuvant treatment planning. The relationship between MLNR and survival in colon cancer was first raised by Berger et al. [

30]. In another study examining 24,477 patients, MLNR was found to be a more accurate prognostic factor than the N stage. When the cut-off for MLNR was set at 0.2, patients with MLNR below this value had a survival rate of 81.1%, while those above it had a rate of 46.6%. Multivariate analysis showed that both thresholds were significant in predicting survival [

31]. Patients who received adjuvant therapy had a significantly lower risk of disease recurrence compared to those who did not (p=0.015). This indicates that adjuvant chemotherapy plays a critical role in colon cancer treatment and is effective in reducing the risk of recurrence.MLNR is a prognostic marker that can guide adjuvant therapy decisions. Patients with a high MLNR (≥0.125) were found to have approximately seven times higher recurrence risk. This finding suggests that adjuvant chemotherapy planning should be tailored more precisely for patients with elevated MLNR.Adjuvant chemotherapy decisions can be individualized by considering the MLNR cut-off value (0.125). Patients with MLNR <0.125 demonstrated better survival outcomes and lower recurrence rates. This suggests that MLNR can help identify the patient groups most likely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.In multivariate analysis, adjuvant therapy and MLNR were identified as independent prognostic factors. The reduced recurrence risk among patients receiving adjuvant therapy (Exp(B): 0.234, p=0.038) underscores the efficacy of this treatment.

Our results, supported by the literature, suggest that MLNR can guide adjuvant chemotherapy decisions, enabling more precise and individualized treatment planning.

4.5. Age and Surgical Factors

Age was found to be a significant factor for both mortality and recurrence in our study (p<0.001). Older patients are often burdened with more comorbidities and have limited surgical options, which may explain this association. However, in multivariate analysis, age was not an independent risk factor, suggesting potential collinearity with comorbidities and other factors.

The impact of emergency surgery on mortality has been previously reported in the literature. In a study by Hogan et al., it was noted that patients undergoing emergency surgery had worse prognosis, with limitations in adjuvant treatment planning [

21]. Similarly, our study found that patients who underwent emergency surgery had lower survival rates (p=0.023).

4.6. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study provides strong evidence supporting the prognostic value of MLNR. However, its retrospective design and limited sample size may restrict the generalizability of the results. Future studies with larger sample sizes could contribute to establishing a universal cut-off value for MLNR.

5. Conclusions

Metastatic lymph node ratio (MLNR) is an important marker for survival and prognosis in colon cancer. Our study demonstrates that lower MLNR is associated with better survival outcomes and suggests that MLNR could guide adjuvant treatment decisions. These findings imply that MLNR should be incorporated as a complementary metric in clinical staging systems. However, further large-scale and prospective studies are needed to validate these results and establish universal cut-off values for MLNR.

Conflicts of Interest: Authors declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantive intellectual contributions in this study to qualify as authors. OA and RT: Conception and design of study , Drafting of manuscript and/or critical revision, Approval of fi nal version of manuscript. İS: Acquisition of data (laboratory or clinical), Data analysis and/or interpretation.MAY: Conception and design of study Acquisition of data (laboratory or clinical) Data analysis and/or interpretation AKP: Drafting of manuscript and/or critical revision Approval of fi nal version of manuscript FU: Conception and design of study Acquisition of data (laboratory or clinical) Data analysis and/or interpretation Submission and Supervision. All authors have read and approved the final version of themanuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Hitit University Faculty of Medicine (Protocol No: 2023-60) and the study protocol was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration.Data were collected retrospectively from patients who were referred to the Department of General Surgery and diagnosed with Colon Adenocarcinoma and underwent surgery. Considering the retrospective design of the study, Hitit University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee granted an exemption for written consent. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the institutional review board and patient confidentiality was meticulously protected by anonymizing all patient records in accordance with ethical standards. This article was presented as an oral presentation at the 23rd National Surgery Congress and the 18th National Surgical Nursing Congress in Antalya between 24-28 April 2024. (oral presentation 293).

Funding

The study had no funding source.

Abbreviations

DFS disease-free survival

| MLNR |

metastatic lymph node ratio |

| CC |

colon cancer |

| OS |

overall survival |

| TNLC |

total lymph node count |

| HR |

hazard ratio |

| CRC |

colorectal cancer |

| NCCN |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| PPV |

positive predictive value |

| NPV |

negative predictive value |

| ROC |

receiver operating characteristic |

| AUC |

area under the curve |

| OR |

Odds ratios |

| CI |

confidence intervals |

References

- Dekker, Evelien, et al. "Colorectal cancer." The Lancet 394.10207 (2019): 1467-1480.

- GLOBOCAN. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. International Agency for Research on Cancer 2020.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (nccn). Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on day month year).

- Zhang, M.-R.; Xie, T.-H.; Chi, J.-L.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Sun, X.-F.; Zhou, Z.-G. Prognostic role of the lymph node ratio in node positive colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 72898–72907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald JR, Renehan AG, O’Dwyer ST, et al. Lymph node harvest in colon and rectal cancer: Current con siderations. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;4:9–19.

- Li Destri G, Di Carlo I, Scilletta R, et al. Colorectal cancer and lymph nodes: The obsession with the number 12. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1951–1960.

- Yilmaz, I.; Isik, A.; Peker, K.; Firat, D.; Yilmaz, B.; Sayar, I.; Idiz, O.; Cakir, C.; Demiryilmaz, I. Importance of Metastatic Lymph Node Ratio in Non-Metastatic, Lymph Node-Invaded Colon Cancer: A Clinical Trial. Med Sci. Monit. 2014, 20, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kukreja SS, Esteban-Agusti E, Velasco JM, et al. Increased lymph node evaluation with colorectal can cer resection: Does it improve detection of stage III disease? Arch Surg. 2009;144:612–617.

- Moro-Valdezate, D.; Pla-Martí, V.; Martín-Arévalo, J.; Belenguer-Rodrigo, J.; Aragó-Chofre, P.; Ruiz-Carmona, M.D.; Checa-Ayet, F. Factors related to lymph node harvest: does a recovery of more than 12 improve the outcome of colorectal cancer? . Color. Dis. 2013, 15, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huh, J.W.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.J. Factors predicting oncologic outcomes in patients with fewer than 12 lymph nodes retrieved after curative resection for colon cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 105, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeganathan AN, Shanmugan S, Bleier JI, et al. Col orectal specialization increases lymph node yield: Evidence from a national database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2258–2265.

- Lykke, J.; Jess, P.; Roikjaer, O. The prognostic value of lymph node ratio in a national cohort of rectal cancer patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2016, 42, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen SL, Steele SR, Eberhardt J et al: Lymph node ratio as a quality and prognostic indicator in stage III colon cancer. 8: Ann Surg, 2011; 253, 2011.

- Cozzani, F.; Agnesi, S.; Dell’abate, P.; Rossini, M.; Viani, L.; Pedrazzi, G.; DEL Rio, P. The prognostic role of metastatic lymph node ratio in colon cancer: a retrospective cohort study on 241 patients in a single center. Minerva Surg. 2023, 78, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bando E, Yonemura Y, Taniguchi K, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Miwa K. Outcome of ratio of lymph node metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:775-784.

- Topcu, R.; Şahiner, I.T.; Kendirci, M.; Erkent, M.; Sezikli, I.; Tutan, M.B. Does lymph node ratio (metastasis/total lymph node count) affect survival and prognosis in gastric cancer? . Saudi Med J. 2022, 43, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wal, B.; Butzelaar, R.; van der Meij, S.; Boermeester, M. Axillary lymph node ratio and total number of removed lymph nodes: predictors of survival in stage I and II breast cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2002, 28, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.C.; Watson, J.C.; Ross, E.A.; Hoffman, J.P. The Metastatic/Examined Lymph Node Ratio is an Important Prognostic Factor after Pancreaticoduodenectomy for Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Am. Surg. 2004, 70, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Choi, G. Clinical Implications of Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Ann. Coloproctology 2019, 35, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Tomiki, Y.; Goto, M.; Kotake, K.; Sugihara, K. Proposal of New Classification for Stage III Colon Cancer Based on the Lymph Node Ratio: Analysis of 4,172 Patients from Multi-Institutional Database in Japan. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 22, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceelen, W.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Pattyn, P. Prognostic Value of the Lymph Node Ratio in Stage III Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 17, 2847–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjol U, Jonnada P, Chandranath A, Cherukuru S. Lymph node ratio as a prognostic marker in rectal cancer survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2020;12:e8047.

- Hogan, J.; Samaha, G.; Burke, J.; Chang, K.H.; Condon, E.; Waldron, D.; Coffey, J.C. Emergency Presenting Colon Cancer Is an Independent Predictor of Adverse Disease-Free Survival. Int. Surg. 2015, 100, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Lv, L.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, K.; Shen, Z.; Wang, S. Comparison of metastatic lymph node ratio staging system with the 7th AJCC system for colorectal cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 139, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, F.; Tolone, S.; Allaria, A.; Napolitano, V.; Rosa, D.; Ilaria, F.; Ottavia, M.; Cesaro, E.; Docimo, L.; Fei, L. Lymph node ratio versus TNM system as prognostic factor in colorectal cancer staging. A single Center experience. Open Med. 2019, 14, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Guller, U.; Ochsner, A.; Oertli, D.; Zuber, M.; Viehl, C.T. Lymph node ratio is inferior to pN-stage in predicting outcome in colon cancer patients with high numbers of analyzed lymph nodes. BMC Surg. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffmann L, Eiken AK, Gock M, Klar E. Is the lymph node ratio superior to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM system in prognosis of colon cancer? World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:79.

- Gao, P.; Song, Y.-X.; Wang, Z.-N.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Tong, L.-L.; Zhu, J.-L.; Tang, Q.-C.; Xu, H.-M. Integrated Ratio of Metastatic to Examined Lymph Nodes and Number of Metastatic Lymph Nodes into the AJCC Staging System for Colon Cancer. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e35021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, R.; Zhu, C.; Wu, X. Proposal of a New Classification for Stage III Colorectal Cancer Based on the Number and Ratio of Metastatic Lymph Nodes. World J. Surg. 2013, 37, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.C.; Sigurdson, E.R.; LeVoyer, T.; Hanlon, A.; Mayer, R.J.; Macdonald, J.S.; Catalano, P.J.; Haller, D.G. Colon Cancer Survival Is Associated With Decreasing Ratio of Metastatic to Examined Lymph Nodes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 8706–8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Hassett, J.M.; Dayton, M.T.; Kulaylat, M.N. Lymph Node Ratio: Role in the Staging of Node-Positive Colon Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 15, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).