Submitted:

08 July 2024

Posted:

09 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics According to the LPT

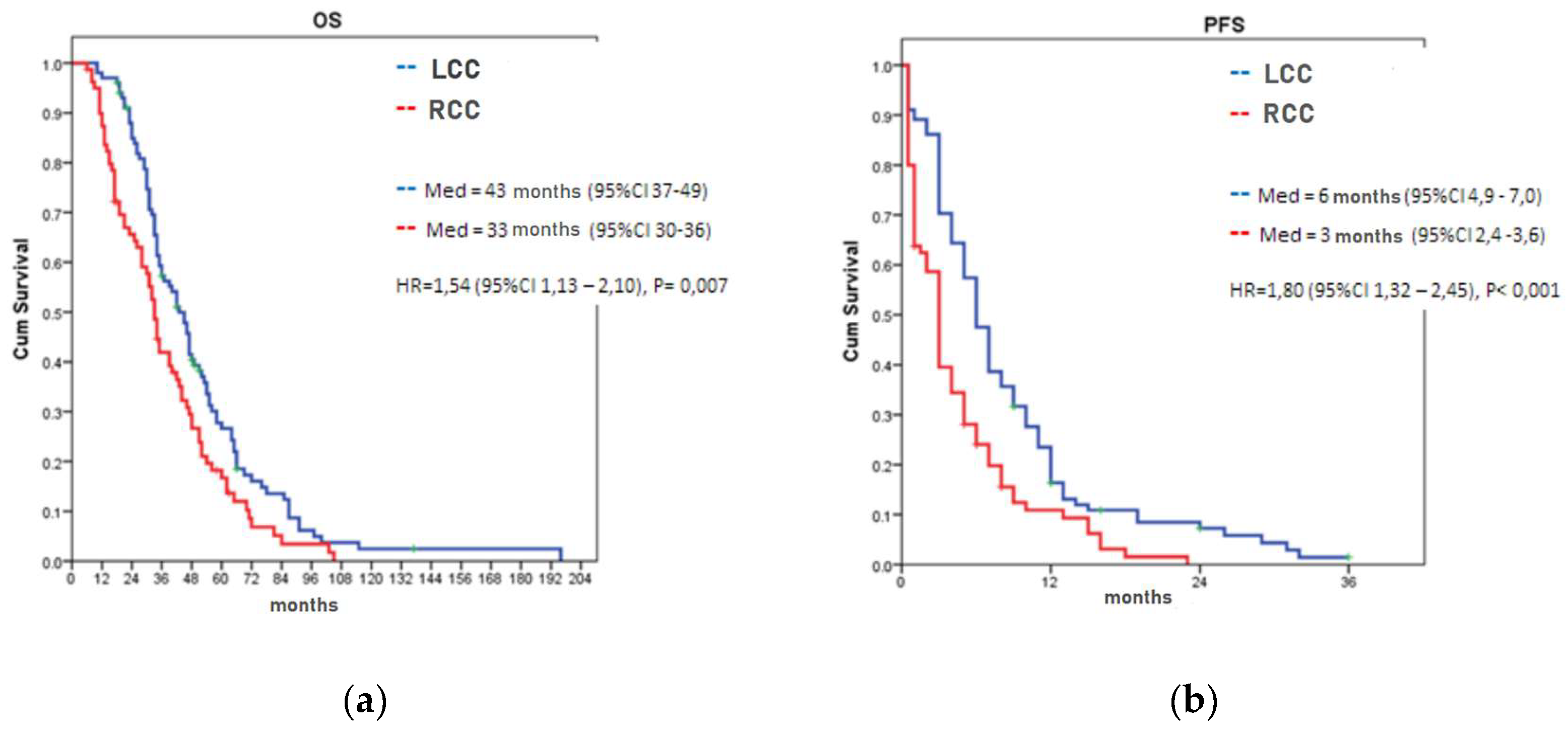

3.2. Overall and Progression-Free Survival According to the LPT

3.3. Response to the Anti-EGFR Therapy in KRAS Wild-Type mCRC Patients

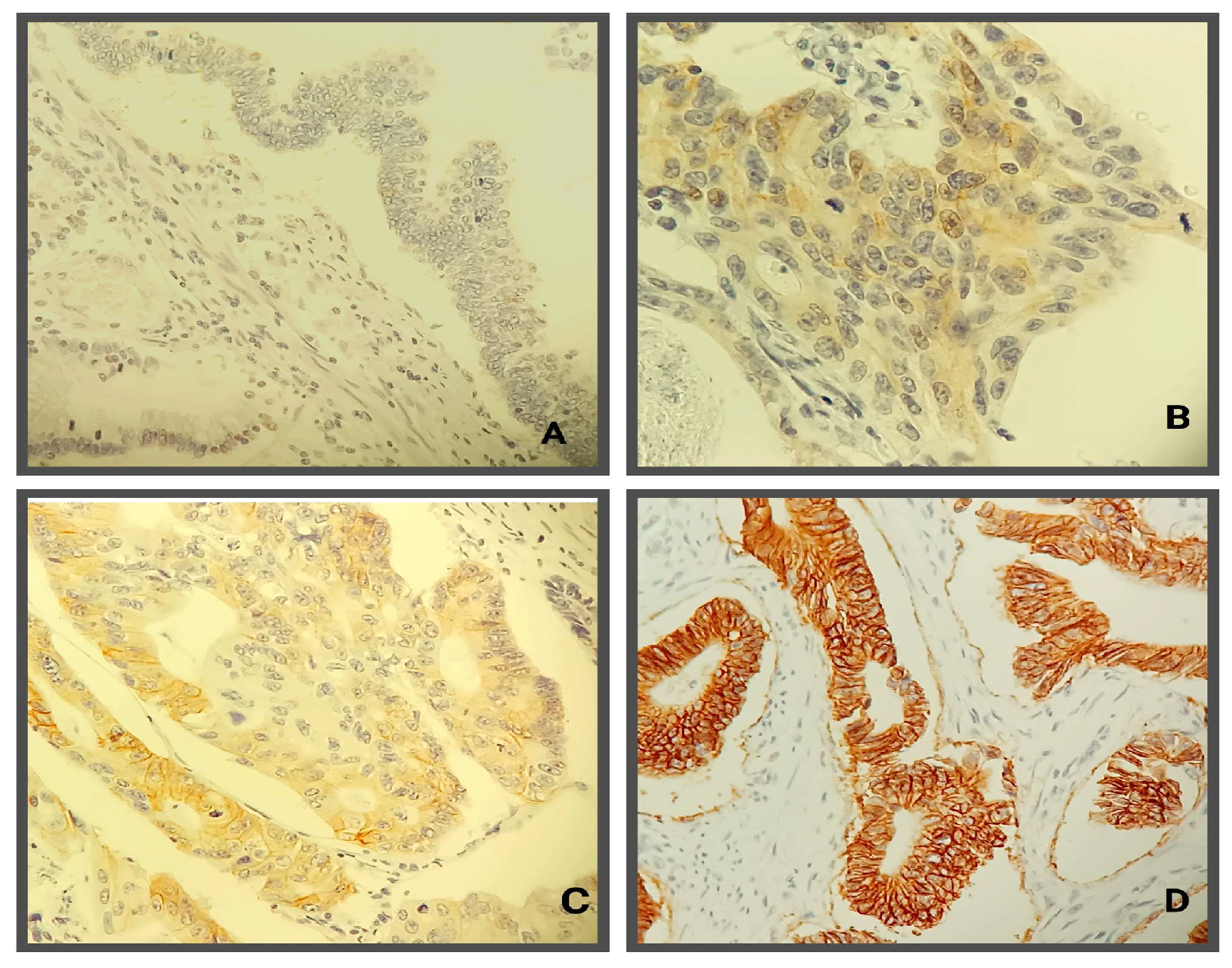

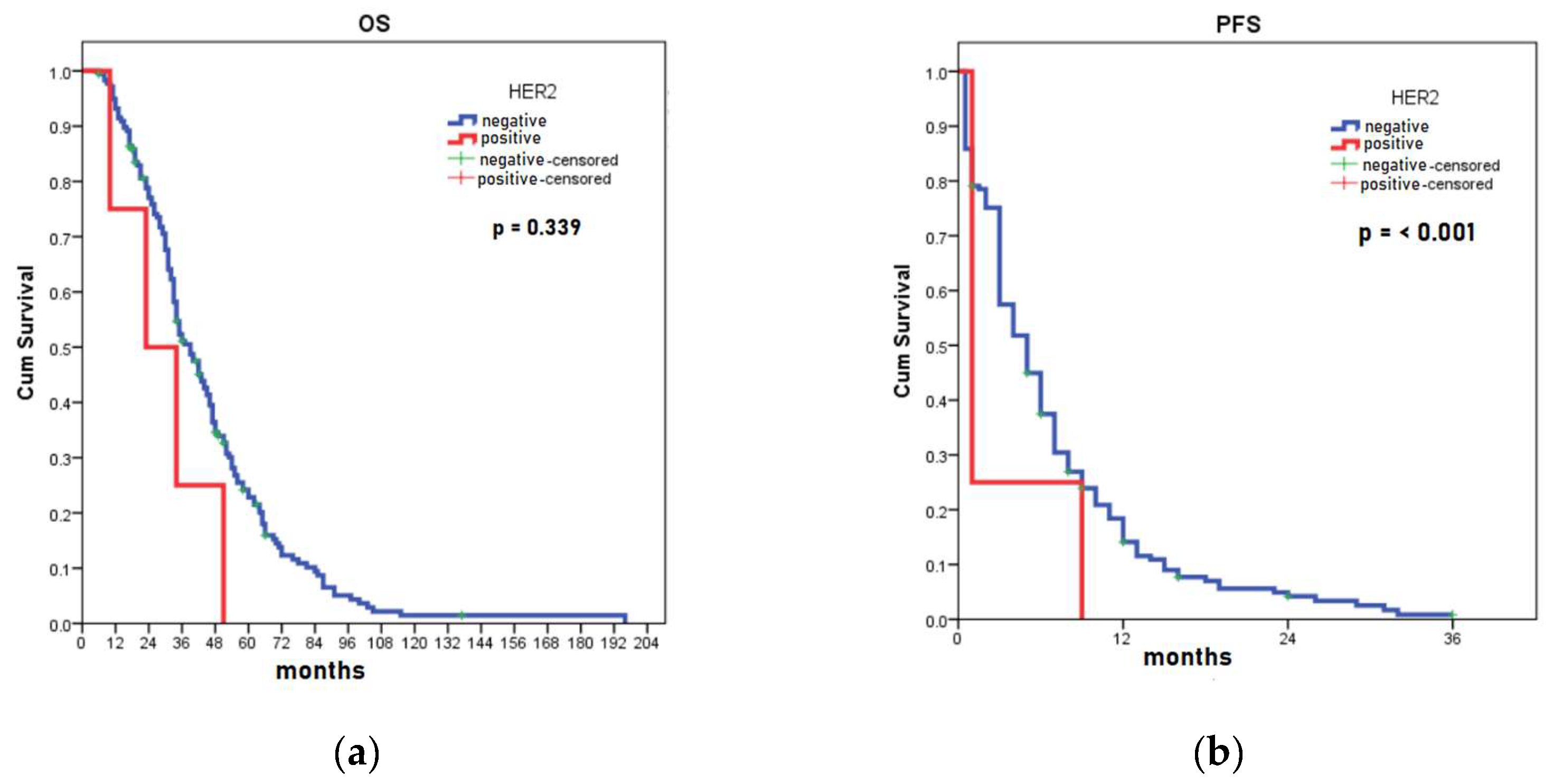

3.4. HER2 Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nagai Y, Kiyomatsu T, Gohda Y, Otani K, Deguchi K, Yamada K. The primary tumor location in colorectal cancer: A focused review on its impact on surgical management. GHM 2021;3:386–93. [CrossRef]

- Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Greene C, O’Neil BH, et al. Impact of primary (1o) tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). JCO 2016;34:3504–3504. [CrossRef]

- Li F, Lai M. Colorectal cancer, one entity or three. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2009;10:219–29. [CrossRef]

- Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, Tabernero J, Van Cutsem E, Beier F, et al. Prognostic and Predictive Relevance of Primary Tumor Location in Patients With RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Retrospective Analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 Trials. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:194–201. [CrossRef]

- Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, Feng S, Cremolini C, Zhang W, et al. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:dju427. [CrossRef]

- Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard J-Y, Peeters M, Lenz H-J, Venook A, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Annals of Oncology 2017;28:1713–29. [CrossRef]

- Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O’Connor ES, King J, LoConte N, Kennedy G, et al. Mortality by Stage for Right- Versus Left-Sided Colon Cancer: Analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare Data. JCO 2011;29:4401–9. [CrossRef]

- Lei S, Ge Y, Tian S, Cai B, Gao X, Wang N, et al. Colorectal Cancer Metastases to Brain or Bone and the Relationship to Primary Tumor Location: a Population-Based Study. J Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:1833–42. [CrossRef]

- Jess T, Horváth-Puhó E, Fallingborg J, Rasmussen HH, Jacobsen BA. Cancer Risk in Inflammatory Bowel Disease According to Patient Phenotype and Treatment: A Danish Population-Based Cohort Study. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2013;108:1869–76. [CrossRef]

- Araki K, Furuya Y, Kobayashi M, Matsuura K, Ogata T, Isozaki H. Comparison of Mucosal Microvasculature between the Proximal and Distal Human Colon. Journal of Electron Microscopy 1996;45:202–6. [CrossRef]

- Kohoutova D, Smajs D, Moravkova P, Cyrany J, Moravkova M, Forstlova M, et al. Escherichia colistrains of phylogenetic group B2 and D and bacteriocin production are associated with advanced colorectal neoplasia. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:733. [CrossRef]

- Gao Z, Guo B, Gao R, Zhu Q, Qin H. Microbiota disbiosis is associated with colorectal cancer. Front Microbiol 2015;6. [CrossRef]

- Missiaglia E, Jacobs B, D’Ario G, Di Narzo AF, Soneson C, Budinska E, et al. Distal and proximal colon cancers differ in terms of molecular, pathological, and clinical features. Annals of Oncology 2014;25:1995–2001. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer NPM, Van Der Kruijssen DEW, Hugen N, De Hingh IHJT, Nagtegaal ID, Verhoeven RHA, et al. The Impact of Primary Tumor Location in Synchronous Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Differences in Metastatic Sites and Survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2020;27:1580–8. [CrossRef]

- Petrelli F, Coinu A, Cabiddu M, Ghilardi M, Barni S. KRAS as prognostic biomarker in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with bevacizumab: a pooled analysis of 12 published trials. Med Oncol 2013;30:650. [CrossRef]

- Linardou H, Briasoulis E, Dahabreh IJ, Mountzios G, Papadimitriou C, Papadopoulos S, et al. All about KRAS for clinical oncology practice: Gene profile, clinical implications and laboratory recommendations for somatic mutational testing in colorectal cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2011;37:221–33. [CrossRef]

- Davis AA, Cristofanilli M. Detection of Predictive Biomarkers Using Liquid Biopsies. In: Badve S, Kumar GL, editors. Predictive Biomarkers in Oncology, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019, p. 107–17. [CrossRef]

- Schirripa M, Cohen SA, Battaglin F, Lenz H-J. Biomarker-driven and molecular targeted therapies for colorectal cancers. Seminars in Oncology 2018;45:124–32. [CrossRef]

- Sjoquist KM, Renfro LA, Simes RJ, Tebbutt NC, Clarke S, Seymour MT, et al. Personalizing Survival Predictions in Advanced Colorectal Cancer: The ARCAD Nomogram Project. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2018;110:638–48. [CrossRef]

- Ahcene Djaballah S, Daniel F, Milani A, Ricagno G, Lonardi S. HER2 in Colorectal Cancer: The Long and Winding Road From Negative Predictive Factor to Positive Actionable Target. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2022:219–32. [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam F, Hurwitz H, Raghav KPS, McWilliams RR, Fakih M, VanderWalde A, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer (MyPathway): an updated report from a multicentre, open-label, phase 2a, multiple basket study. The Lancet Oncology 2019;20:518–30. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal N, Iqbal N. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) in Cancers: Overexpression and Therapeutic Implications. Molecular Biology International 2014;2014:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Press MF, Bernstein L, Thomas PA, Meisner LF, Zhou JY, Ma Y, et al. HER-2/neu gene amplification characterized by fluorescence in situ hybridization: poor prognosis in node-negative breast carcinomas. JCO 1997;15:2894–904. [CrossRef]

- Sartore-Bianchi A, Trusolino L, Martino C, Bencardino K, Lonardi S, Bergamo F, et al. Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): a proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. The Lancet Oncology 2016;17:738–46. [CrossRef]

- Poston GJ, Figueras J, Giuliante F, Nuzzo G, Sobrero AF, Gigot J-F, et al. Urgent Need for a New Staging System in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. JCO 2008;26:4828–33. [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Washington: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Inc n.d. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon_blocks.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Buscarino M, Corti G, Cassingena A, Crisafulli G, et al. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med 2015;21:795–801. [CrossRef]

- Lee GH, Malietzis G, Askari A, Bernardo D, Al-Hassi HO, Clark SK. Is right-sided colon cancer different to left-sided colorectal cancer? – A systematic review. European Journal of Surgical Oncology (EJSO) 2015;41:300–8. [CrossRef]

- Baran B, Mert Ozupek N, Yerli Tetik N, Acar E, Bekcioglu O, Baskin Y. Difference Between Left-Sided and Right-Sided Colorectal Cancer: A Focused Review of Literature. Gastroenterol Res 2018;11:264–73. [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper A, Van Den Eynde M, Machiels J-P. HER2 as a Predictive Biomarker and Treatment Target in Colorectal Cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer 2020;19:65–72. [CrossRef]

- Boeckx N, Koukakis R, Op De Beeck K, Rolfo C, Van Camp G, Siena S, et al. Primary tumor sidedness has an impact on prognosis and treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from two randomized first-line panitumumab studies. Annals of Oncology 2017;28:1862–8. [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Lopez LA, Nahas SC, Nahas CSR, Pinto RA, Marques CFS, Cecconello I. IS THERE A DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RIGHT- VERSUS LEFT-SIDED COLON CANCERS? DOES SIDE MAKE ANY DIFFERENCE IN LONG-TERM FOLLOW-UP? ABCD, Arq Bras Cir Dig 2019;32:e1479. [CrossRef]

- Venderbosch S, Nagtegaal ID, Maughan TS, Smith CG, Cheadle JP, Fisher D, et al. Mismatch Repair Status and BRAF Mutation Status in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Pooled Analysis of the CAIRO, CAIRO2, COIN, and FOCUS Studies. Clinical Cancer Research 2014;20:5322–30. [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Ma C, Li W. Does overexpression of HER-2 correlate with clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis in colorectal cancer? Evidence from a meta-analysis. Diagn Pathol 2015;10:144. [CrossRef]

- Yalikong A, Li X-Q, Zhou P-H, Qi Z-P, Li B, Cai S-L, et al. A Triptolide Loaded HER2-Targeted Nano-Drug Delivery System Significantly Suppressed the Proliferation of HER2-Positive and BRAF Mutant Colon Cancer. IJN 2021;Volume 16:2323–35. [CrossRef]

- Raghav K, Loree JM, Morris JS, Overman MJ, Yu R, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. Validation of HER2 Amplification as a Predictive Biomarker for Anti–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Antibody Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JCO Precision Oncology 2019:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth JD, Meric-Bernstam F, Swanton C, Hurwitz H, Spigel DR, Sweeney C, et al. Targeted Therapy for Advanced Solid Tumors on the Basis of Molecular Profiles: Results From MyPathway, an Open-Label, Phase IIa Multiple Basket Study. JCO 2018;36:536–42. [CrossRef]

- Ingold Heppner B, Behrens H-M, Balschun K, Haag J, Krüger S, Becker T, et al. HER2/neu testing in primary colorectal carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2014;111:1977–84. [CrossRef]

- Yagisawa M, Sawada K, Nakamura Y, Fujii S, Yuki S, Komatsu Y, et al. Prognostic Value and Molecular Landscape of HER2 Low-Expressing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clinical Colorectal Cancer 2021;20:113-120.e1. [CrossRef]

- Puccini A, Lenz H-J, Marshall JL, Arguello D, Raghavan D, Korn WM, et al. Impact of Patient Age on Molecular Alterations of Left-Sided Colorectal Tumors. The Oncologist 2019;24:319–26. [CrossRef]

- Park DI, Kang MS, Oh SJ, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, et al. HER-2/neu overexpression is an independent prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:491. [CrossRef]

- Siena S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Marsoni S, Hurwitz HI, McCall SJ, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Targeting the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) oncogene in colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology 2018;29:1108–19. [CrossRef]

- Parikh A, Atreya C, Korn WM, Venook AP. Prolonged Response to HER2-Directed Therapy in a Patient With HER2-Amplified, Rapidly Progressive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017;15:3–8. [CrossRef]

| Gender | values | LCC n=75/26/101 |

RCC n=49/31/81 |

Total n=124/57/81 |

P value1 |

| Male | average (SD) | 62.9 (9.1) | 62.6 (9.8) | 62.8 (9.3) | 0.833 |

| min-max | 30 – 75 | 36 - 76 | 30 – 76 | ||

| Female | average (SD) | 57.6 (10.4) | 59.5 (12.8) | 58.6 (11.7) | 0.553 |

| min-max | 37 - 79 | 21 - 76 | 21 – 79 | ||

| All | average (SD) | 61.6 (9.6) | 61.4 (11.1) | 61.5 (10.3) | 0.902 |

| min-max | 30 - 79 | 21 - 76 | 21 – 79 | ||

| P value1 | 0.015 | 0.227 | 0.011 |

| Parameters | Values | LCC n=101 |

RCC n=81 |

P value1 |

| Pathohistological type of tumor | Mucinous | 3 (3.0%) | 15 (18.8%) | 0.001 |

| NOS | 97 (96.0%) | 63 (78.8%) | ||

| Singnet ring cell | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | ||

| Differentiation | Good | 15 (14.9%) | 7 (7.8%) | 0.031 |

| Moderate | 75 (74.3%) | 53 (66.2%) | ||

| Poor | 11 (10.9%) | 20 (25.0%) | ||

| Resection margins | R0 | 85 (84.2%) | 72 (90.0%) | 0.442 |

| R1 | 6 (5.9%) | 4 (5.0%) | ||

| palliative surgery | 10 (9.9%) | 4 (5.0%) | ||

| Tumor infiltration lymphocyte | dense | 19 (18.8%) | 11 (13.8%) | 0.176 |

| poor | 23 (22.8%) | 28 (35.0%) | ||

| moderate | 59 (58.4%) | 41 (51.2%) | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | II | 13 (12.9%) | 15 (18.8%) | 0.283 |

| III | 39 (38.6%) | 35 (43.8%) | ||

| IV | 49 (48.5%) | 30 (37.5%) | ||

| No. of examined LN | average (SD) | 14.4 (8.7) | 18,2 (9.6) | 0.003 |

| min-max | 0 – 40 | 0 - 50 | ||

| No. of positive LN | average (SD) | 4.19 (4.7) | 5.29 (5.8) | 0.414 |

| min-max | 0 - 25 | 0 - 25 | ||

| No. of metastatic sites | average (SD) | 1.37 (0.66) | 1.60 (0.79) | 0.035 |

| min-max | 1 - 5 | 1 - 4 | ||

| Lymph node involvement |

present | 6 (5.9%) | 3 (3.8%) | 0.742 |

| Lymphovascular invasion |

present | 76 (75.2%) | 55 (68.8%) | 0,332 |

| Perineural invasion | present | 64 (63.4%) | 50 (62.5%) | 0.905 |

| Ileus | present | 28 (27.7%) | 24 (30.0%) | 0.737 |

| Metastatic sites | Liver | 73.9% | 72.5% | 0.908 |

| Lung | 20,8% | 22,5% | 0.781 | |

| LN of abdomen | 12,9% | 25,0% | 0.036 | |

| local recurrence | 9.9% | 6.2% | 0.376 | |

| LN of pelvis | 5.0% | 11.2% | 0.115 | |

| Carcinosis of peritoneum | 3.0% | 8.9% | 0.091 | |

| LN of thorax | 1.0% | 7.5% | 0.062 | |

| Ovary | 3.0% | 1.2% | 0.785 | |

| Bouns | 2.0% | 1.2% | 1.000 | |

| Adrenal gland | 2.0% | 1.2% | 1.000 | |

| Brain | 1.0% | 1.2% | 1.000 | |

| Urinary bladder | 2.0% | 0.0% | 0.582 | |

| Prostate | 1.0% | 0.0% | 1.000 | |

| Pancreas | 1.0% | 0.0% | 1.000 |

| Line of therapy |

LCC n= 101 |

RCC n= 80 |

Total n= 181 |

P value1 |

| II | 3 (3.0%) | 5 (6.2%) | 8 (4.4%) | 0.162 |

| III | 88 (87.1%) | 72 (90.0%) | 160 (88.4%) | |

| IV | 10 (9.9%) | 3 (3.8%) | 13 (7.2%) |

| Predictors in CRC | B | SE | P1 | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.990 | 0.269 | <0.001 | 2.69 | 1.59-4.56 |

| Right localization of primary tumor | 0,.375 | 0.164 | 0.022 | 1.46 | 1.06-2,01 |

| Perineural invasion | 0.355 | 0.167 | 0.034 | 1.43 | 1.03-1.98 |

| Resection margins end palliative surgery |

0.518 | 0.263 | 0.049 | 1.68 | 1.02-2.81 |

| Predictors in LCC | B | SE | P1 | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

| Perineural invasion | 0.468 | 0.225 | 0.038 | 1.60 | 1.03-2.48 |

| Predictors in RCC | B | SE | P1 | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1.136 | 0.304 | <0.001 | 3.12 | 1.72-5.66 |

| Predictors in CRC | B | SE | P1 | Exp(B) | 95% CI |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 0.927 | 0.270 | 0.001 | 2.53 | 1.49-4.29 |

| Right localization of primary tumor | 0.471 | 0.165 | 0.004 | 1.60 | 1.16-2.21 |

| Parameters | Characteristics | Not responded n=79 |

Good response n=102 |

P value1 |

| LPT | right | 49 (61.2%) | 31 (30.8%) | < 0,001 |

| left | 30 (29.7%) | 71 (70.3%) | ||

| Pathohistological type of tumor | NOS, SRCC | 64 (39.3%) | 99 (60.7%) | 0.001 |

| mucionus | 15 (83.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | ||

| Differentiation | good | 7 (31.8%) | 15 (68.2%) | 0.233 |

| Moderate, poor | 72 (45.3%) | 87 (54.7%) | ||

| Stage of disease | II | 11 (39.3%) | 17 (60.7%) | 0.613 |

| III, IV | 68 (44.4%) | 85 (55.6%) | ||

| No examined LN | <11 | 18 (34.6%) | 34 (65.4%) | 0.120 |

| 12< | 61 (47.3%) | 68 (52.7%) | ||

| Involved LN | No | 16 (36.4%) | 28 (63.6%) | 0.263 |

| Yes | 63 (46.0%) | 74 (54.0%) | ||

| Resection margins and palliative surgery |

R0 |

69 (43.9%) | 88 (56.1%) | 0.541 |

| R1, R2 | 10 (41.7%) | 14 (58.3%) | ||

| LVI | No | 20 (40.0%) | 30 (60.0%) | 0.188 |

| Yes | 59 (45.0%) | 72 (55.0%) | ||

| PNI | No | 25 (37.3%) | 42 (62.7%) | 0.834 |

| Yes | 54 (47.4%) | 60 (52.6%) | ||

| TIL | Poor, moderate | 25 (49.0%) | 26 (51.0%) | 0.361 |

| Dense | 54 (41.5%) | 76 (58.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).