1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1, 2). At diagnosis, approximately 25% of patients present with metastatic disease, with the liver (55%) and peritoneum (25%) being the most frequently involved sites (3).

However, the incidence of peritoneal metastases tends to be underestimated due to the small size of peritoneal nodules, often below the resolution levels of CT scans. Radiological signs such as the presence of ascites, thickening and contrast enhancement of the peritoneum, and mesenteric effacement can aid in diagnosis. Additionally, MRI has shown to be more effective in detecting small peritoneal lesions due to its higher diagnostic sensitivity (4-6).

The formation of peritoneal metastases is based on the detachment of free tumor cells from the primary tumor and their subsequent spread into the peritoneal cavity through direct invasion, hematogenous or lymphatic routes, or surgical manipulation. The Peritoneal Carcinomatosis Index (PCI) is the most widely accepted score to quantify tumor burden and assess patient prognosis. The abdomen is divided into 13 regions, and a score from 0 to 3 is assigned in each region based on the maximum size of each peritoneal implant. Another score, the Peritoneal Surface Disease Severity Score (PSDSS), combines the PCI score with the evaluation of patient symptoms (weight loss, abdominal pain, ascites) and the histology of the primary tumor. (4, 5).

Peritoneal involvement is associated with a poor prognosis, with survival times ranging from 5 to 7 months without treatment and extending to 7-16 months with systemic chemotherapy alone.

Over the past thirty years, the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in conjunction with cytoreductive surgery (CRS) has gained traction. This procedure involves removing macroscopically visible disease via CRS to allow optimal penetration of chemotherapeutic agents into the tissue; hyperthermia (41-43°C) enhances the effects of the chemotherapeutics Mitomycin C and Oxaliplatin used in intraperitoneal administration and has a known direct cytotoxic effect (1).

The introduction of CRS+HIPEC has led to an increase in survival up to 45 months in selected groups. A careful selection of patients for this procedure is crucial. Risk factors to consider include the extent of peritoneal disease measured by the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI), the completeness of cytoreduction, lymph node status, tumor differentiation and histology of signet-ring cells; recently, mutations in KRAS and BRAF and microsatellite instability (MSI) status also seem to play an emerging role in the stratification and selection of these patients (7, 8).

While the benefit of CRS+HIPEC on the survival of selected patients operated in specialized centers is evident, there are differing opinions regarding the chemotherapeutic regimens used in HIPEC.

The PRODIGE 7 study failed to demonstrate the efficacy of the short-duration (30 min) Oxaliplatin regimen, leading to a shift towards the use of Mitomycin C with a longer administration duration (60-90 min). However, PRODIGE 7 had two biases: the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on Oxaliplatin, which induces the development of drug-resistant clones, and the suboptimal activity of the drug during the 30 minutes of perfusion, as it depends on exposure time and temperature. Further studies are needed to clarify the best HIPEC regimen, its standardization, and its actual role and impact in the treatment of peritoneal metastases (4, 9, 10).

As an additional problem, 8% of patients with advanced CRC present with both liver metastases (LM) and peritoneal metastases (PM) (11). Traditionally, the simultaneous presence of LM and PM was considered a contraindication to surgical treatment. Today, this is no longer an absolute contraindication, although the role of combined surgery remains controversial. According to some studies, combined resection of CRS+HIPEC and liver resection is associated with increased postoperative morbidity (11-13). Other studies report no increase in postoperative complications from the addition of concomitant liver resection (14-16). However, there seems to be no difference in the rate of reintervention and postoperative mortality compared with patients undergoing CRS+HIPEC alone (11, 12). Several studies have shown that CRS+HIPEC, including resection of liver metastases, can increase the survival of these patients. Careful preoperative assessment of patients combined with a tailored surgical approach (one-step vs. two-step liver surgery, laparoscopic techniques, etc.) is mandatory to achieve an increase in survival without a significant increase in morbidity (3, 14, 15).

2. Materials and Methods

Our study analyzes 41 patients who underwent liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases at our center between October 2021 and February 2024. Of these, 7 underwent concomitant CRS+HIPEC surgery because they had synchronous liver and peritoneal metastases.

The diagnosis of peritoneal carcinosis of colorectal origin was histologically confirmed in all cases by a preliminary laparoscopic exploration with a confirming peritoneal biopsy. The decision to perform CRS and HIPEC was a multidisciplinary indication provided by surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists. In all cases, the decision was shared and accepted by the patients with a complete description of the proposed intervention and possible complications.

2.1. Variables and Definitions

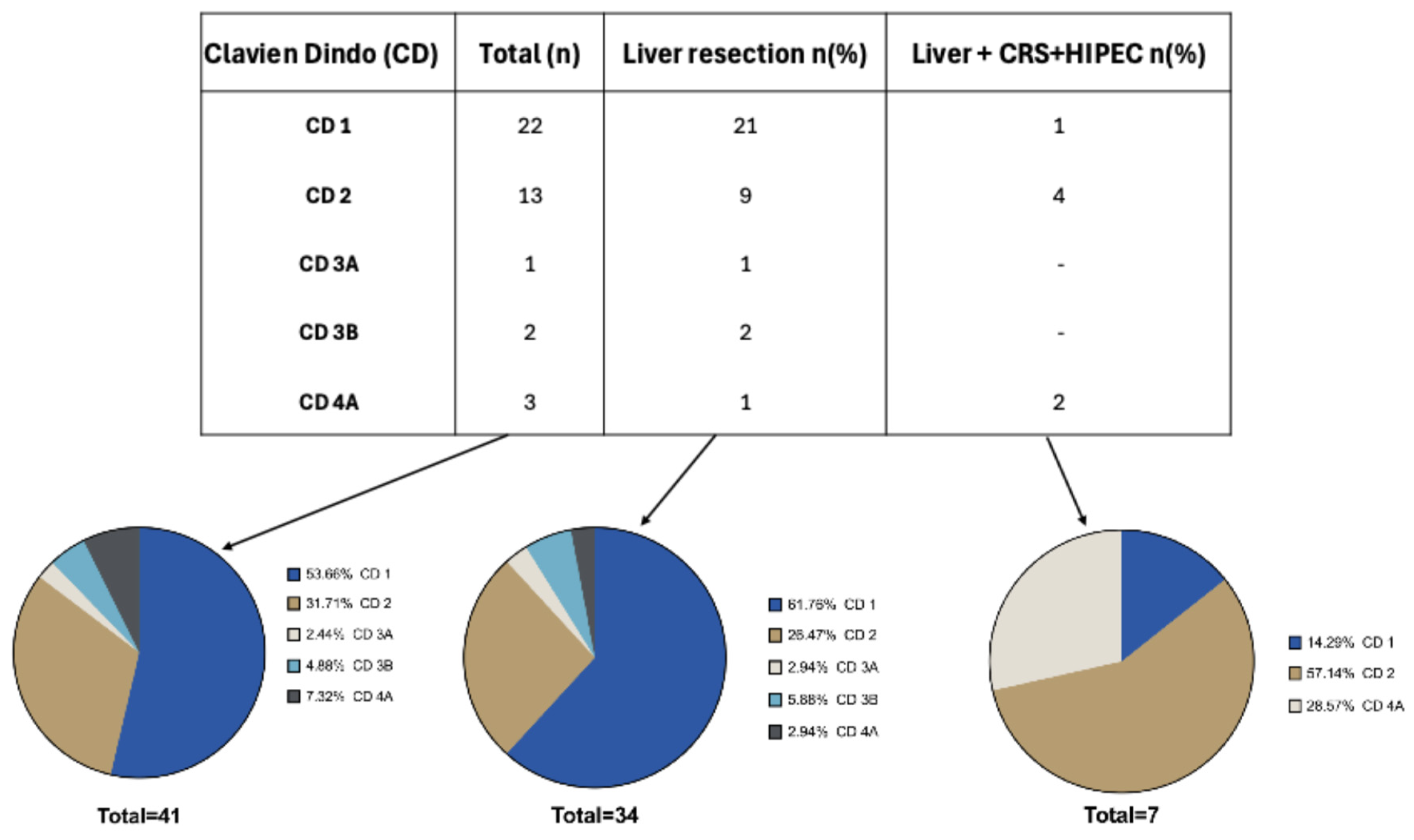

We collected patient demographics including sex, age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), date of surgery, operative time, total length of stay, metastasis characteristics (number, unilobar/bilobar location, size), the tumor’s staging according to the AJCC-TNM classification and the surgical therapies or adjuvant chemotherapy of the primitive tumor. The development of postoperative complications was documented and reported using the Clavien-Dindo classification (CD) (17, 18) (

Table 1).

2.2. Surgical Technique

Patients under general anesthesia underwent laparotomy. The first phase of the intervention was the exploration of the operative field with simultaneous contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) to confirm and conclusively evaluate hepatic metastases. Patients with peritoneal carcinosis underwent cytoreduction as the first phase of the procedure.

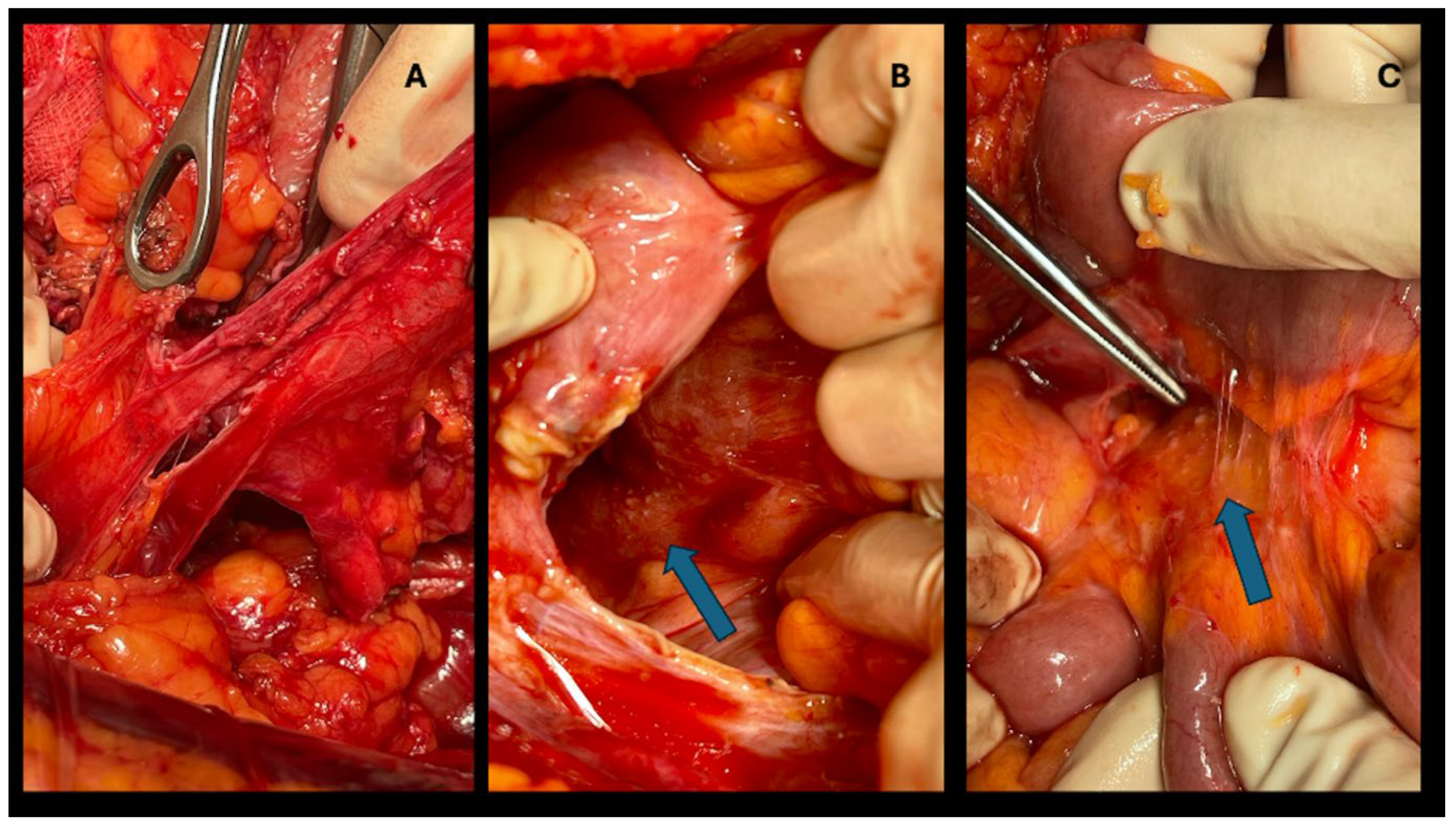

2.3. Technique of CRS + HIPEC

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) involves removing visible peritoneal disease locations and other possible secondary locations in the abdominal compartment. Typically, an omentectomy is performed, even if the omentum does not appear to be immediately involved by metastases, due to its frequent involvement (4, 19). Following CRS, HIPEC is added: this involves the intraoperative administration of a chemotherapeutic solution heated to 41-43°C, circulated in the peritoneal cavity for a variable period (30-120 minutes). There are two HIPEC techniques, open and closed, equally effective in clinical outcomes (1, 4). At our center, the closed technique is performed: the laparotomy is sutured, and inflow and outflow catheters and temperature sensors are placed through the abdominal wall. The best chemotherapeutic regimen to use is still debated, although the most commonly used drugs are Mitomycin C and Oxaliplatin (1, 4) . In this study we employed Mitomycin C with 90 minutes of perfusion. In the combined resection of hepatic and peritoneal metastases, the HIPEC procedure is performed after cytoreductive and hepatic surgery (

Figure 1).

2.4. Types of Liver Resection

Hepatic resections were all performed in an open setting. Hepatic resections in all patients were performed with ultrasound-guided technique using the Sonoca Soring ultrasonic scalpel for dissection with intermittent hilum clamping (Pringle maneuver 7/3 closed/open).

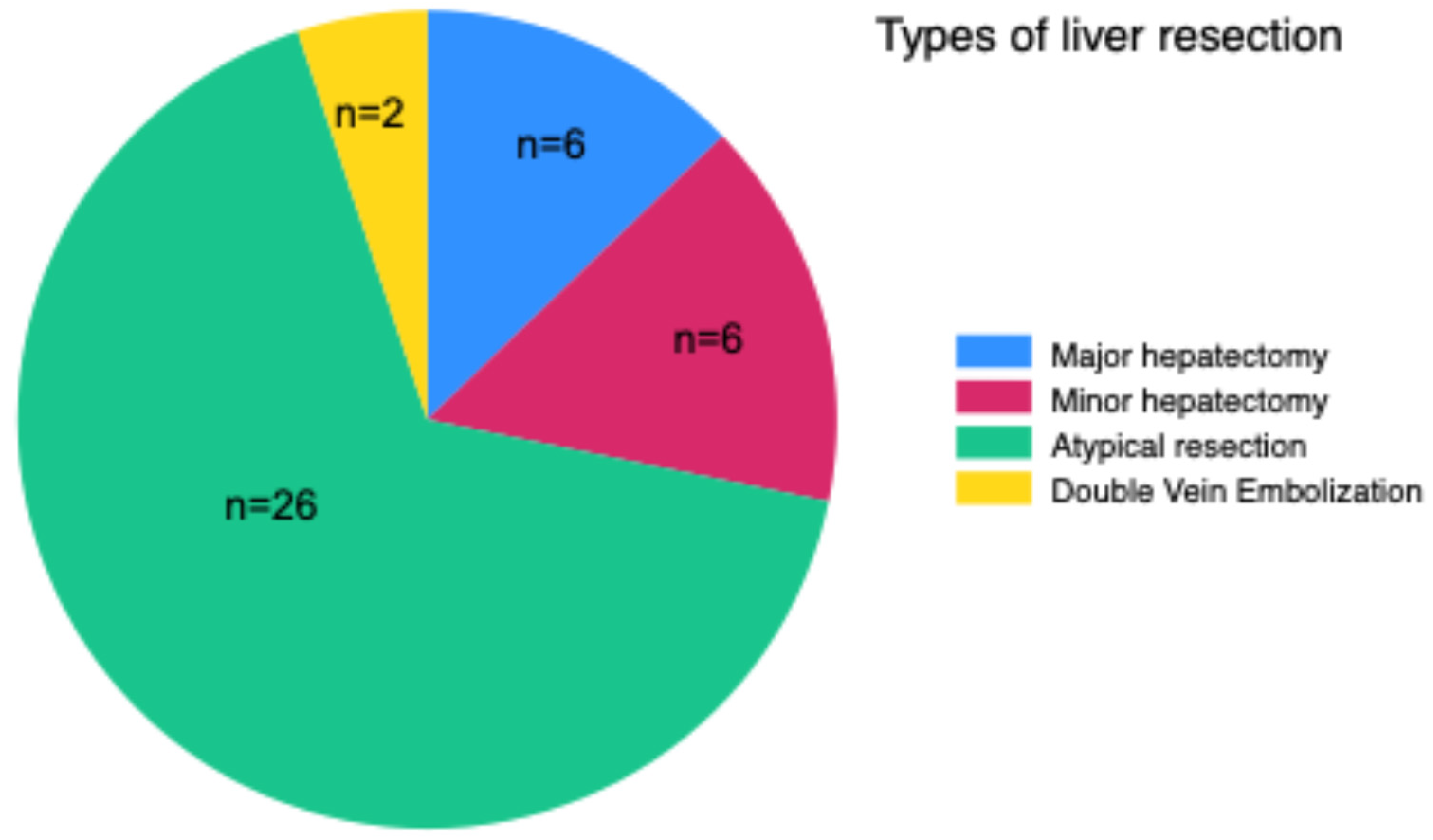

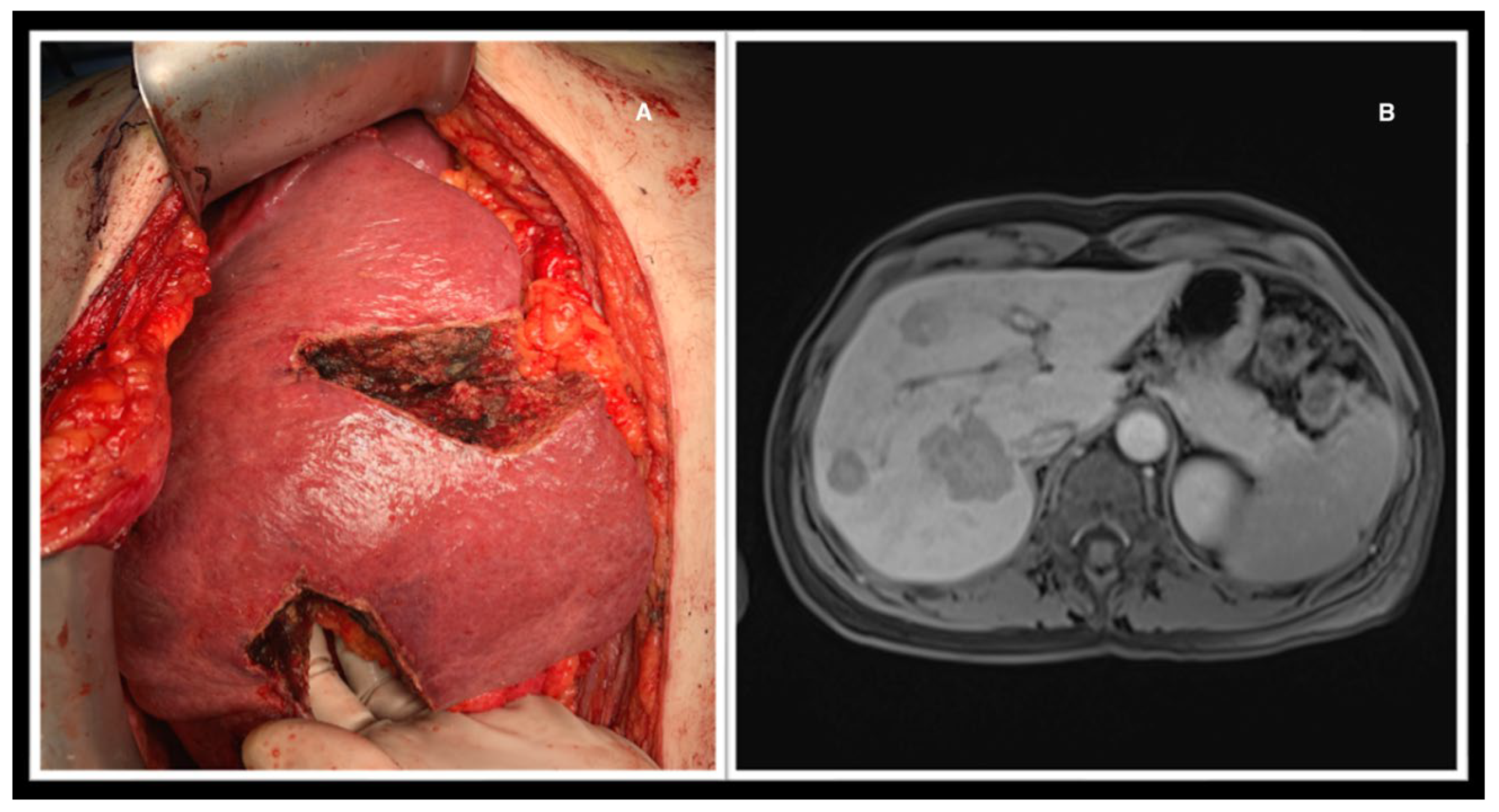

The extent of surgery to be performed was decided based on imaging examinations (CT, MRI, or both), anatomical complexity, and whether CRS+HIPEC was performed concomitantly. Operations performed included major hepatectomy (three or more liver segments; n=6), minor hepatectomy (less than three segments; n=6), atypical resection (n=26), and extended atypical resections after double-vein embolization (n=2) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). This latter procedure involves simultaneous embolization of the right portal vein and hepatic right and middle veins to induce liver regeneration and increase the chances of resectability of very extensive lesions in size, number, or bilobar localization (20) (21).

2.5. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was to evaluate the variables that could influence postoperative morbidity in our patients and determine if different types of liver surgery were significant on this outcome in isolated resections and/or in cases of concomitant CRS+HIPEC.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with StataBE18 software. Simple linear regression was used to determine which parameters influenced the development of postoperative complications (as measured by CD), with significance established at p<0.05. Multiple linear regression was then conducted to identify any independent variables affecting the CD outcome, with significance also established at p<0.05.

3. Results

Simple linear regression showed that the CRS+HIPEC procedure, operative time, and length of hospital stay significantly impacted CD outcome (p<0.05). In contrast, the type of liver resection, number and size of metastases, unilobar/bilobar location, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) were not significant. Multiple linear regression did not identify any independent variables that could influence the CD outcome (

Table 2).

3.1. Postoperative Evaluation

The majority of patients had a regular postoperative course without any significant complication: CD 1 (n=22) and CD 2 (n=13). One patient developed superficial wound dehiscence that needed an intervention under local anesthesia (CD 3A; n=1), while two patients showed respectively a biliary leak and a dehiscence requiring a surgical revision (CD 3B; n=2). Three patients had a single organ dysfunction (CD 4A; n=3) and specifically two acute kidney injury (AKI) and one acute myocardial infarction (IMA) (

Figure 4).

We documented no mortality during the first 30 days of observation after surgery.

4. Discussion

There is now evidence that the CRS+HIPEC procedure offers a survival advantage in patients with peritoneal metastases from CRC compared with chemotherapy alone, although careful patient selection is necessary (7). In recent years, there has been a shift regarding advanced CRC with concomitant peritoneal and liver metastases: liver involvement is no longer considered a contraindication to cytoreduction. Again, patient selection plays a key role in maximizing the benefits and minimizing the risks associated with this procedure (3, 14, 16). The issue of perioperative morbidity in patients undergoing CRS+HIPEC and liver resection is controversial: some studies do not show a significant difference between patients treated with combined resection and those with CRS+HIPEC alone, while others suggest it is a therapeutic alternative with increased risk of postoperative complications; some studies advocate a two-step approach with a liver-first strategy to limit disease progression between surgeries (3, 14-16) . Our study shows that the CRS+HIPEC procedure, operative time, and total length of stay influence the development of complications in the immediate postoperative period, whereas the addition of different types of liver resection does not significantly impact this outcome. Many factors likely contribute to the development of postoperative complications, which could not be accounted for due to the limited number of patients in the study. The performance of combined resection must be carefully tailored to the individual patient. Moreover, this approach requires thorough preoperative evaluation and should be performed in specialized centers, involving a multidisciplinary team of peritoneal neoplasm specialists, hepatobiliary surgeons, radiologists, oncologists and anatomic pathologists. This multidisciplinary approach is essential to achieving a survival advantage without a significant increase in morbidity.

5. Key Points and Future Directions

The addition of liver resection to a complex surgery does not necessarily impact the postoperative outcome.

The combined treatment of hepatic and peritoneal metastases should be considered in the management of patients with advanced CRC and not negatively viewed considering potential curative surgery.

The assessment of the oncological outcome is not the aim of this study.

The study has a limit in his retrospective approach and in the still limited number of subjects.

Author Contributions

Writing – original draft: O.C.; data curation: O.C.; methodology: all authors; supervision: A.L., M.MA.; validation: M.MA.; writing – review and editing: M.MA.; project administration: M.MA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- van Stein, R.M.; Aalbers, A.G.J.; Sonke, G.S.; van Driel, W.J. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Ovarian and Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, S.; Cavallaro, G.; La Rovere, F.; Usai, V.; Siragusa, L.; Izzo, P.; et al. Synchronous liver and peritoneal metastases from colorectal cancer: Is cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy combined with liver resection a feasible option? Front Surg. 2022, 9, 1006591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winicki, N.M.; Greer, J.B. Is Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy Appropriate for Colon Cancer? Adv Surg. 2024, 58, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hidalgo, J.M.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, L.; Arjona-Sánchez, Á.; Rufián-Peña, S.; Casado-Adam, Á.; Cosano-Álvarez, A.; et al. Colorectal peritoneal metastases: Optimal management review. World J Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 3484–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, R.N.; Barone, R.M.; Lucero, J. Comparison of MRI and CT for predicting the Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) preoperatively in patients being considered for cytoreductive surgical procedures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015, 22, 1708–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonello, M.; Baratti, D.; Sammartino, P.; Di Giorgio, A.; Robella, M.; Sassaroli, C.; et al. Microsatellite and RAS/RAF Mutational Status as Prognostic Factors in Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases Treated with Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29, 3405–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, R.X.; Lim, J.H.; Ly, J.; Fischer, J.; Smith, N.; Karalus, M.; et al. Long-term survival following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in Waikato, Aotearoa New Zealand: A 12-year experience. ANZ J Surg. 2024, 94, 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vlasakker, V.C.J.; Lurvink, R.J.; Cashin, P.H.; Ceelen, W.; Deraco, M.; Goéré, D.; et al. The impact of PRODIGE 7 on the current worldwide practice of CRS-HIPEC for colorectal peritoneal metastases: A web-based survey and 2021 statement by Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021, 47, 2888–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, M.; van Der Speeten, K.; Govaerts, K.; de Hingh, I.; Villeneuve, L.; Kusamura, S.; et al. 2022 Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International Consensus on HIPEC Regimens for Peritoneal Malignancies: Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024, 31, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Soriano, R.; Pineño-Flores, C.; Morón-Canis, J.M.; Molina-Romero, F.J.; Rodriguez-Pino, J.C.; Loyola-Miró, J.; et al. Simultaneous Surgical Approach with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) in Patients with Concurrent Peritoneal and Liver Metastases of Colon Cancer Origin. J Clin Med. 2023, 12, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polderdijk, M.C.E.; Brouwer, M.; Haverkamp, L.; Ziesemer, K.A.; Tenhagen, M.; Boerma, D.; et al. Outcomes of Combined Peritoneal and Local Treatment for Patients with Peritoneal and Limited Liver Metastases of Colorectal Origin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022, 29, 1952–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cloyd, J.M.; Abdel-Misih, S.; Hays, J.; Dillhoff, M.E.; Pawlik, T.M.; Schmidt, C. Impact of Synchronous Liver Resection on the Perioperative Outcomes of Patients Undergoing CRS-HIPEC. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018, 22, 1576–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Dico, R.; Faron, M.; Yonemura, Y.; Glehen, O.; Pocard, M.; Sardi, A.; et al. Combined liver resection and cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC for metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a worldwide analysis of 565 patients from the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021, 47, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Y.; Aycart, S.; Tabrizian, P.; Agmon, Y.; Mandeli, J.; Heskel, M.; et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with liver involvement. J Surg Oncol. 2016, 113, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randle, R.W.; Doud, A.N.; Levine, E.A.; Clark, C.J.; Swett, K.R.; Shen, P.; et al. Peritoneal surface disease with synchronous hepatic involvement treated with Cytoreductive Surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Ann Surg Oncol. 2015, 22, 1634–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.R.; Small, D.G.; Termuhlen, P.M. Evaluation of Charlson-Age Comorbidity Index as predictor of morbidity and mortality in patients with colorectal carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004, 8, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Doan, N.H.; Hosseini, M.; Kelly, K.; Veerapong, J.; Lowy, A.M.; et al. Is Routine Omentectomy a Necessary Component of Cytoreductive Surgery and HIPEC? Ann Surg Oncol. 2023, 30, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torzilli, G.; McCormack, L.; Pawlik, T. Parenchyma-sparing liver resections. Int J Surg. 2020, 82, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenblik, R.; Heil, J.; Smits, J.; James, S.; Olij, B.; Bechstein, W.O.; et al. Liver regeneration after portal and hepatic vein embolization improves overall survival compared with portal vein embolization alone: Mid-term survival analysis of the multicentre DRAGON 0 cohort. Br J Surg. 2024, 111, znae087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).