1. Introduction

Shopping malls are major energy consumers, and the major reason for this is the use of chiller-based HVAC systems in them. Operation in the conventional manner, though, leads to major energy inefficiencies and waste. It is an important question then, how can we make the operation efficient through advanced technologies? Building Automation Systems (BAS) have proven incredibly valuable in optimizing the energy efficiency of chillers. With the ability to monitor parameters in real-time and make dynamic adjustments in parameters such as temperature, flow rates, and operating schedules for equipment, BAS facilitates smarter and responsive operations. Such abilities help maintain energy usage in closer conformity with actual cooling requirements, eliminating unnecessary usage. This forward-looking control method not only increases the performance of the chiller, but it has the potential for revolutionizing the practice of energy management in the contemporary shopping center. The ramifications reach wide: from substantial cost benefits to decreasing the environmental impact. This work examines the in-practice advantages of adopting an Supervisory Control and Building Automation System (SC+BAS) for maximizing the efficiency in the chiller plants and enabling the adoption of sustainable practices in the urban, energy-hungry, built environment. Particular emphasis is given to the assessment of an off-the-shelf product—Tracer® SC+: Flexible. Open. Secure.—with the objective of providing tangible performance improvements. Tracer® SC+ works in complete harmony with existing chiller plant infrastructure through the availability of open communication protocol support, such as BACnet, Modbus, and LonTalk. Such compatibility facilitates solid interoperability among HVAC equipment for enhanced supervisory control, as well as higher operational efficiency, all while ensuring occupant comfort within desired parameters.

Supervisory Control plus Building Automatic System (SC+BAS) is the latest generation in control technology produced by the HVAC industry for the optimization of chiller plant operations. It accomplishes its task through its Chiller Plant Control (CPC) application, an advanced piece of software that facilitates the centralized, smart controlling of the system. SC+BAS offers complete function, including real-time system status and alarm notifications for both local and remote users, the ability to enable and disable chiller plants, start, stop, and monitor chilled water pumps, and calculate the individual chilled water setpoints for each chiller in multiple-series configurations. It also automates adding or removing chillers based on building load conditions, utilizing user-established logic, and supports chiller sequencing at predetermined intervals, including the conditional removal of units from sequential sequencing based on need. One of its most advanced features is the Trim/Respond (T/R) algorithm, which dynamically resets the setpoints for the system. The algorithm incrementally changes the setpoint at a preset rate until the downstream device is dissatisfied, generating a request. When the desired amount accumulates within the predetermined interval, the system reacts by altering the setpoint accordingly. It also features the ability for users to set the priority level for each zone, ensuring essential zones get consistent, adequate cooling. When the amount falls below the threshold, the system returns to its original fixed-rate adjustment. The SC+BAS monitors requests from every zone in real-time, allowing it to identify the zones responsible for the reset logic, as well as the ability to target optimization. Multiple implementations of the T/R logic can be performed in a single platform for the control of multiple setpoints. Users can use predetermined strategies, such as those described in ASHRAE Guideline 36, or create customized solutions specific to the needs of the system. Available reset strategies consist of chilled water temperature reset, chilled water enable, chilled water pressure reset, cooling discharge air temperature setpoint reset, static pressure setpoint reset, and customized reset configurations.

This case study discusses a busy shopping mall in the metropolitan Mong Kok area in Hong Kong, an urban area famous for its high number of retail shops, eateries, and entertainment facilities. In such a high-demand area, energy waste is an important consideration, and Building Automation Systems (BAS) has proven to be an efficient and innovative method for managing the same. With the incorporation of advanced control features, BAS enhances the functioning of the HVAC systems, causing waste in energy usage and overall inefficiency in the system. In 2024, the shopping mall installed a Supervisory Control and Building Automation System (SC+BAS) for maximizing the performance of its chiller plant. The system was installed with an aim towards enhancing the operational efficiency, while reducing energy usage and the cost associated with it, and decreasing the maintenance cost through the benefit of intelligent monitoring, control, and automated functions. The chiller plant consists of three 300-ton refrigeration (TR) chillers (WCPC-1 through WCPC-3), three duty and a single standby chilled water pumps, three cooling towers, and three duty and one standby condenser water pumps. In this real-world commercial application, the impact of the incorporation of SC+BAS on the efficiency in energy usage in the chillers is analyzed in this paper, together with an analysis of the resulting cost saving in the form of energy usage and the expenditure in the form of maintenance. It also identifies the important parameters affecting the efficiency of the optimization of the chiller plant in the shopping mall scenario.

2. Literature Review

Van Roosmale et al. (2024) point out the high potential of Building Automation and Control Systems (BACS) in improving energy efficiency and indoor environmental quality in buildings. BACS allows the capture of real-time data and uses automated control to facilitate informed decision-making in the facilities. This not only maximizes the use of energy, but it also improves the controlled and comfortable indoor environment. Furthermore, coupling BACS with artificial intelligence (AI) for predictive maintenance increases its benefit such that equipment failure can be detected early. Such an early intervention decreases the cost of maintenance, increases equipment life, and improves the overall sustainability of building operations in the long term. [

1]

Real-time prediction and subsequent optimization of cooling system setpoints utilizing Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Chiller Systems with Artificial Neural Network (ANN) techniques are employed by Kang et al. (2021) for significant improvement in the energy efficiency. In the work, the ANN algorithm was implemented in the actual building and the average energy saving rate of the ANN controlled chiller was 24.7% and the COP improvement rate was 28.2%. It indicates that the building management system (BAS) energy consumption can be enhanced through the operation of smart algorithms. [

2]. It is feasible to save energy in HVAC systems while not sacrificing the thermal comfort through resetting the setpoint for the chilled water temperature. Fong et al. (2005) propose a simulation-optimization based method for the determination of a reset strategy for the chilled water and the supply air temperatures for an HVAC system placed in the subway station. It used the optimization of the parameters at work through the use of evolutionary programming in order to reduce the annual energy usage. It has been identified in the findings that the energy saving can be up to 7 % in case the chilled water and the supply air temperatures can be adjusted from the operational point. [

6]

With mechanical vapor compression chiller as the control variate, Thu et al. (2017) [

7] performed experiments to analyze the effect of chilled water supply temperature (Tchws) on the performance of the chiller. The tests showed that the COP as well as the cooling capacity, both increase in a linear relationship with increasing Tchws. Specifically, for each increase in Tchws by 2°C, the COP increases about 3.5%. Their findings indicate that in HVAC systems where only sensible cooling is needed (i.e., without dehumidification), it is possible to increase the Tchws—up to about 17°C—without harming indoor thermal comfort. The change lowers the power consumed by chillers substantially. Literature identifies the promise of chilled water temperature reset as an energy-saving intervention further, pointing out that boosting the temperature setpoint for sensible cooling lowers the compressor lift, hence making the chiller efficient.

In another related experiment, Schibuola et al. (2018) [

9] performed an experimental analysis into the implementation of Variable Speed Drive (VSD) technology in a fan coil system in a public building. In the experiment, based on monitoring the system’s performance in the long term, it was shown that the incorporation of VSD technology in the fan coil system lowered the global annual energy use of pumps and fans by 38.9% compared to that in the conventional constant flow rate system. The authors noted that such an effect would only be reliably predicted via simulation models and noted that prolonged monitoring was necessary in an effort to fully evaluate the long-run advantages of the implementation of VSD.

Wang et al. (2015) [

10] studied an all-variable speed, water-cooled chiller plant supplying a laboratory building. The authors used trend data gathered from the building management system (BMS) to identify operational inefficiencies and opportunities for commissioning. A dynamic energy simulation model for the chiller plant was created in order to assess control strategies for optimizing energy performance. The results upheld the significant potential for VSD technology to increase the efficiency in the operation of chiller plants.

Collectively, these studies highlight the enormous energy-saving value in Variable Speed Drive technology for HVAC equipment, especially fans and pumps. In contrast with conventional constant-speed equipment, VSD makes motor speed dynamic in response to actual load demand, achieving very high electricity savings and reducing the energy waste in the system.

The efficiency and performance of the cooling system rely on the choice of sequencing control methods for the chillers. Most often, traditional sequencing methods assume an invariable maximum cooling capacity for each chiller, which may not be the real conditions. Liu et al. (2017) propose an ideal chiller sequencing control method taking into account the variation in the single chiller maximum cooling capacity. Existing methods assume an invariable amount, while the authors formulate the actual capacity based on the condenser water temperature, among other parameters. Optimization is then used in determining the best chiller loading along with the number of operational chillers in order to minimize power usage. The findings indicate the optimum strategy outperforms traditional methods in systems with varying speed chillers and non-dedicated pumps. With proper modeling of the chiller capacity, the optimum strategy can save up to 21.2% power compared to traditional approaches. [

11]

The gap in knowledge in evaluating the real benefits of the Supervisory Control and Building Automation System (SC+BAS) in the given shopping mall stems from the use of the single case study. The actual economic and environmental benefits resulting from the application of SC+BAS in a chiller plant can be markedly conditioned by such multifaceted contextual variables as local weather, the type of functional building use, building material choice, and local building legislation compliance.

As an example, the building envelope transmission loss is directly influenced by regulatory requirements like Overall Thermal Transfer Value (OTTV) standards. Such standards specify acceptable heat gain limits through the building envelope, in turn influencing the energy efficiency in HVAC systems. Hence, local climate variations and regulatory regimes need to be factored in while considering the performance in the case of SC+BAS systems.

In addition, variations in operating practices, occupancy, and upkeep methods can also impact the overall performance and efficiency of the SC+BAS. Therefore, an enhanced and localized approach is necessary in order to properly monitor and measure the advantages provided through these systems, such that the results will be based on the specifics regarding the traits and needs of the urban setting in which it is implemented. Addressing such variables, the potential of SC+BAS in providing tangible economic and environmental payoffs in various urban environments can be better explored in follow-up studies.

These methods underscore the need for combining AI, adaptive control, and dynamic optimization toward sustainable HVAC operations. As far as quantification of energy efficiency improvements and cost reduction goes, methodical analyses of BAS implementations in shopping mall chillers currently remain sparse. The objective of the project is to determine the impact of BAS on chiller energy efficiency as well as cost-saving in a shopping mall environment, hence offering meaningful analysis for facility managers and stakeholders.

3. Methodology

In 2023, the building owner collected log data from energy meters, chiller control panels, and MVAC switchboards. In 2024, the shopping mall installed a SC+BAS, which allows direct export of energy consumption data. The BAS records real-time energy usage of equipment and generates log files. The analysis is based on log data, electricity bills, and design and operational information of the chiller plant.

3.1. Data Collection from Various Sources

The bi-hourly log data of Chilled water inlet temperature, Tin, Chilled water outlet temperature, Tout, kWh reading from control panel, Wch,panel were collected from the control panels of chillers. To establish a baseline for energy consumption, the total electrical energy consumption of the chillers was recorded over one year. Data was collected daily from the electricity meters installed at the chiller units, including energy consumption of chiller WCPC-1, WCPC-2 & WCPC-3, measured by energy meters CH1, CH1 & CH3.

These information is acquired from the O&M manual, including chilled water flow rates of chillers WCPC-1, 2, and 3; electricity tariff from January 2023 to December 2024; and usable floor area of a Typical shopping mall.

3.2. Computation of Performance Parameters

3.2.1. Information from Control Panels of Chillers

Based on the collected and available information from the control panels of chillers, the following performance parameters were determined according to Eqs (1)-(7) as follows.

where,

r: water density (kg/m3)

: chilled water flow rate in an hour ((m3/s)×h)

cw: specific heat capacity of water with a value of 4.2 (kJ/(kg×K))

where,

i: operating hour of the jth chiller, 1 £ i £ k

j: 1 for chiller WCPC-1 and so forth, 1 £ j £ 3

k: last operating hour according to the log data of energy meter, 1 £ k £ 24

p: day of a month, 1 £ p £ n

n: 31 for September and November; or 30 for October

where:

P is the power in watts (W).

VL is the line voltage in volts (V)=380(V)

IL is the line current in amperes (A).

cos(ϕ) is the power factor=0.89

Converting to kilowatts:

To convert the three-phase power from watts to kilowatts

3.2.2. Information from Energy Meters

With the collected information from energy meters, the following performance parameters were determined according to Eqs (8)-(9) as follows.

Daily total energy consumption from energy meters CH1, CH2, and CH3, Wch,total,d (kWh)

b. Overall COP of operating chillers based on energy meters CH1, CH2, and CH3, COPch,d

3.3. Data Handling and Assumption

Daily Cooling Output

The building owner recorded operational log data in 2023 from energy meters, chiller control panels, and MVAC switchboards. In 2024, the shopping mall was equipped with a Supervisory Control and Building Automation System (SC+BAS) that allowed for the direct export of energy use data. The equipment energy use is monitored in real-time and automatically generates log files by the SC+BAS. System log data, electricity bills, and the design and operational characteristics of the chiller plant form the basis for the analysis in the current study.

3.4. Data Collection Frequency

Installed sensors and monitoring tools gathered real-time operational data on the chiller system following BAS installation. To catch the dynamic changes in the system, the data-collecting frequency was set to a high rate—every 15 minutes. The key parameters monitored include

Power Consumption: Measured by the electricity metres installed on the chillers.

Temperature: High-precision temperature sensors tracked inlet and outlet water temperatures.

Flow Rate: Flow sensors put on the pipes measured chilled water flow rates.

3.5. Preliminary Analysis and Data Organization

The data gathered was arranged and preliminarily analyzed to guarantee its correctness and completeness.

Data Cleaning: using data analysis tools to find missing values and anomalies and remove them.

Preliminary Analysis: Monthly total energy consumption, operating time, and load demand were calculated. Trends in energy consumption, operating time, and load demand were plotted to provide a preliminary understanding of the data.

3.6. The Energy Consumption of the Chiller Plant

Assessing the energy consumption of the chiller plant is crucial for optimizing its operational efficiency and minimizing operating costs. However, in 2023, direct extraction of energy consumption data from the Building Management System (BMS) was not possible, as the system had not yet been installed. As a result, alternative methods were employed to obtain energy usage data for the chiller units, including:

Manual Recording of Equipment Operation

Electricity consumption from tariff bill

Energy consumption data from switchboards of chiller plant

a. Manual Recording of Equipment Operation.

Manually documenting start and stop times for equipment, load levels, and rough estimates of energy usage based on rated power is an often-employed method in the absence of computerized monitoring systems. It is, however, very much reliant on the observation and input of humans. In practice, the actual running times and load rates recorded by operating staff will often be approximate, introducing much uncertainty. As such, the method is limited in accuracy and is best reserved for short-term usage or initial energy assessments.

The electricity bills give total energy use during a billing cycle, often monthly. The information is the total electricity use for the building or building complex, giving an overall picture of energy use patterns. Keep in mind that the amount the chiller system uses is only part of the total amount consumed, and it cannot be individually isolated from other building loads.

Switchboard data provides higher granularity and system-specific information on energy usage. For the purposes of this case, an entire year of high-resolution energy usage information—from January 2023 through December 2023—had been pulled directly off the switchboards in the chiller plants. Such information provides for higher accuracy and specificity in the analysis of the chiller plant performance.

In order to analyze the quality of electricity bill data compared with switchboard data, the two types can be compared along multiple axes, including data accuracy, resolution in time, and the capacity for the measurement of specific system usage. Switchboard data allows for system-level information with greater resolution and specificity, yet utilizes electricity bill data for only the total monthly measurement. Differences might occur if the measurement intervals between the two datasets conflict. In order to reduce such differences, it is important that the billing cycle for the electricity company align with the operating periods in the switchboard data.

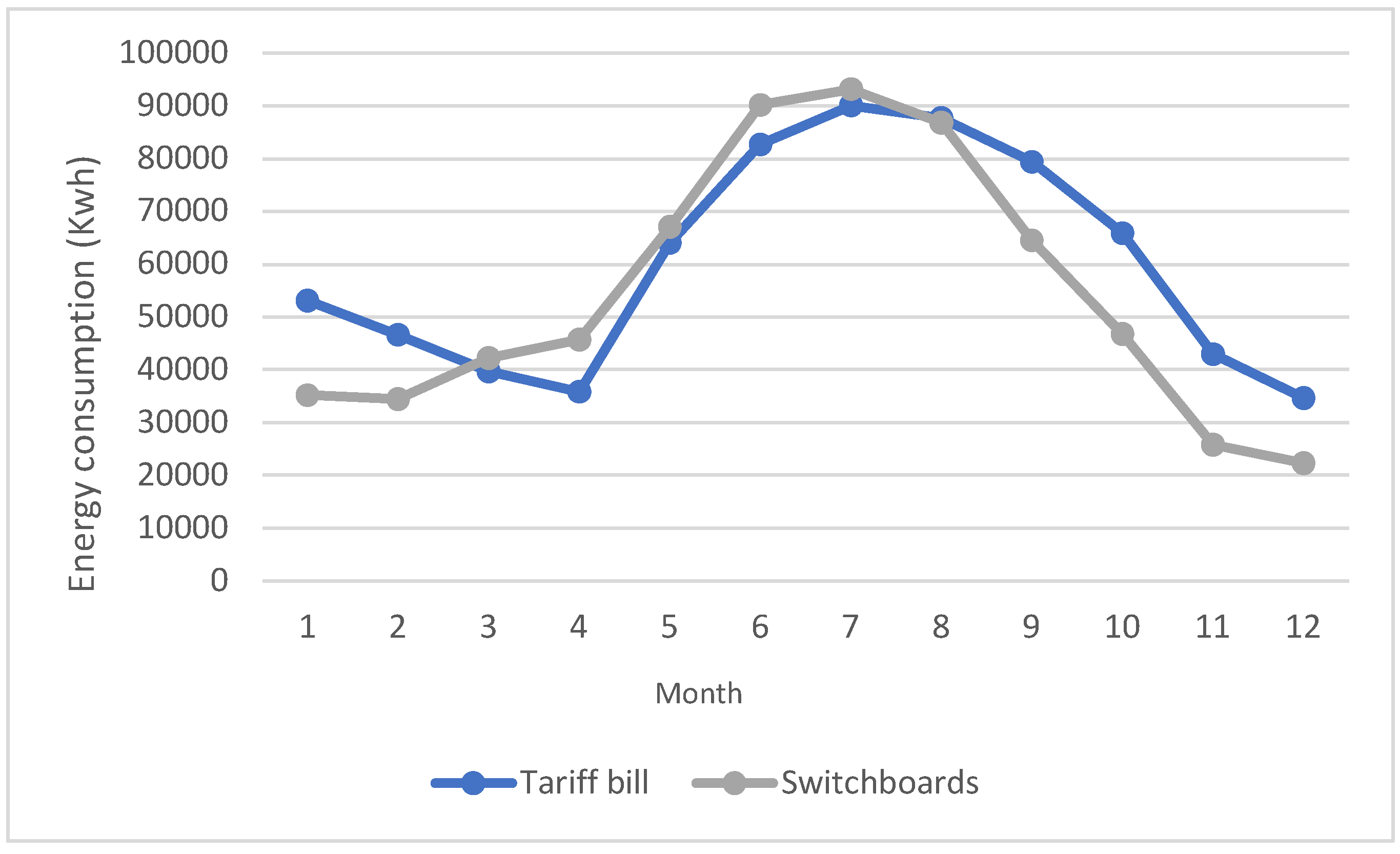

Figure 1.

2023 Annual profiles of electricity consumption from tariff bill and energy consumption from MVAC switchboards.

Figure 1.

2023 Annual profiles of electricity consumption from tariff bill and energy consumption from MVAC switchboards.

The 2023 electricity bill data were compared with the energy usage data from the switchboard in the chiller plant, and substantial differences in the annual usage patterns were noted. It is likely that the electricity bill indicates the overall power usage throughout the chiller plant room, including perhaps not just the chillers proper but auxiliary equipment such as fans for ventilation, lighting, and other non-associated systems. Conversely, the switchboard data break down into greater specificity, permitting the association and segregation of the usage into an analysis for each component in the chiller system—e.g., the chillers, cooling towers, and pumps. With greater resolution and specificity, the switchboard data represent a better and more credible source for the chiller system annual usage analysis. As such, the analysis in this report relies on the chiller switchboard data for the energy performance analysis.

4. Data Collection and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Measurement Results

4.1.1. Monthly Results and Summary

The following parameters are the key results of the chiller plant in each month:

Monthly cooling output of chiller plant, Qtotal,m (kW)

Monthly energy consumption of entire chiller plant, Wtotal,m(kW)

Monthly overall COP of chiller plant, COPm

Difference of monthly energy consumption between 2023 and 2024, DW (kW)

Difference of monthly cooling output between 2023 and 2024, DQ(kW)

Ratio of monthly 2024 energy consumption to 2023 energy consumption, Re

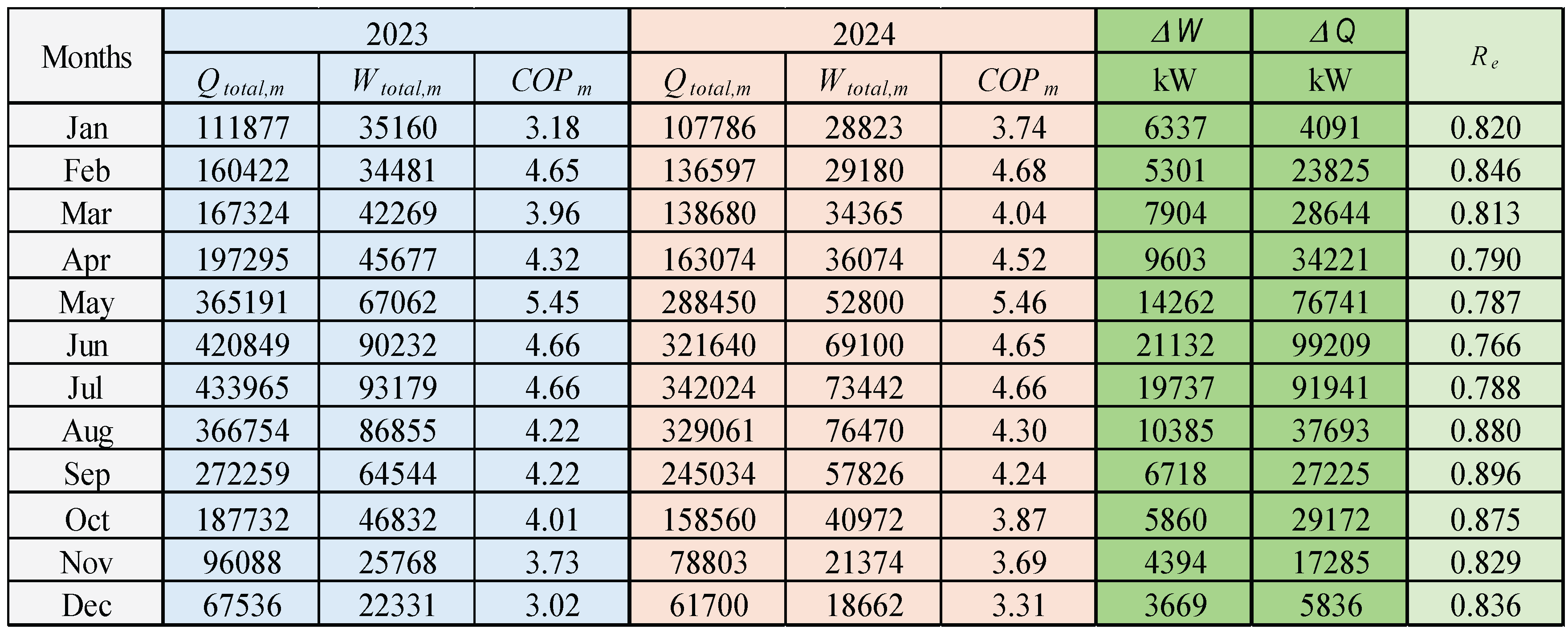

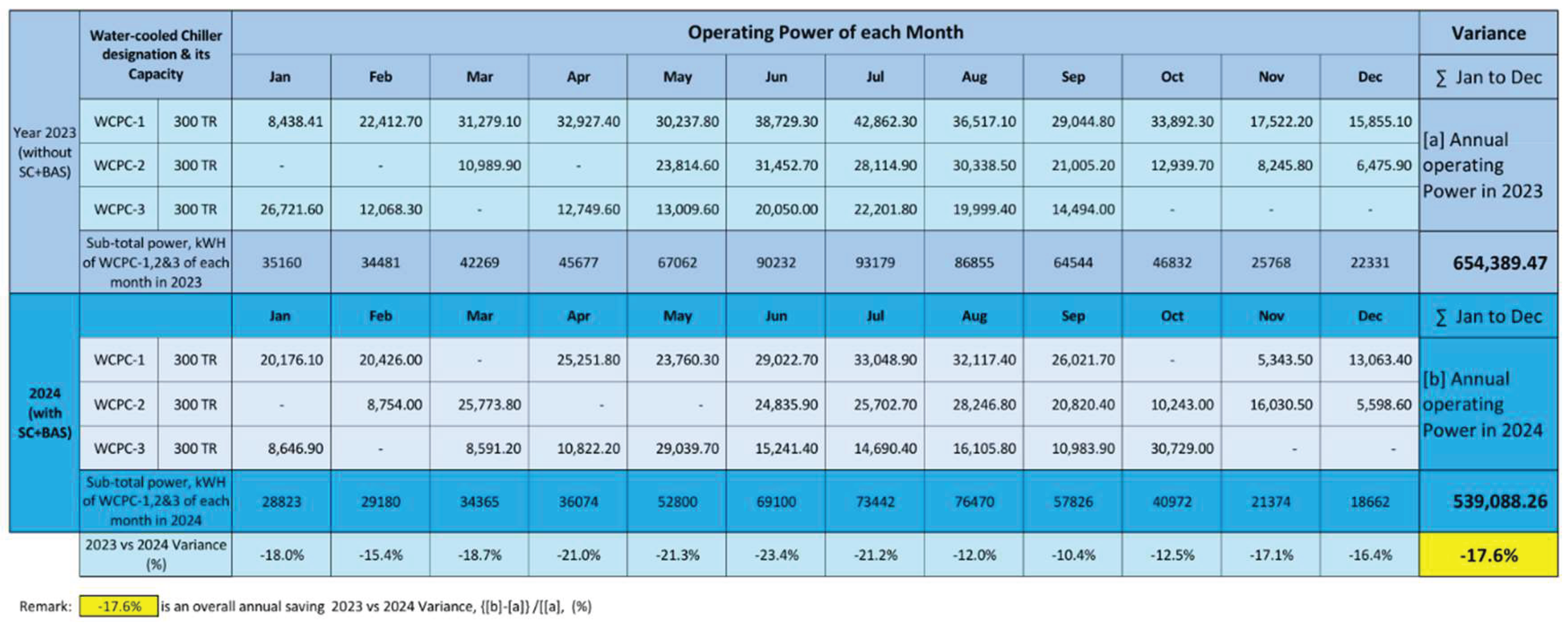

The outcomes of these parameters for the months between January and December 2023 and January and December 2024 appear in

Table 1. The trend analysis indicates sharper decreases in electricity usage and cooling load for the summer months (May through August). Conversely, the decrease in energy consumption and cooling demand is weaker for the winter months (November through February) because, by nature, these months involve lower cooling demands. Such observations indicate an acceptable seasonal shift in the cooling demand profile, following the anticipated changes in ambient conditions throughout the year.

4.1.2. Changes in Electricity Consumption

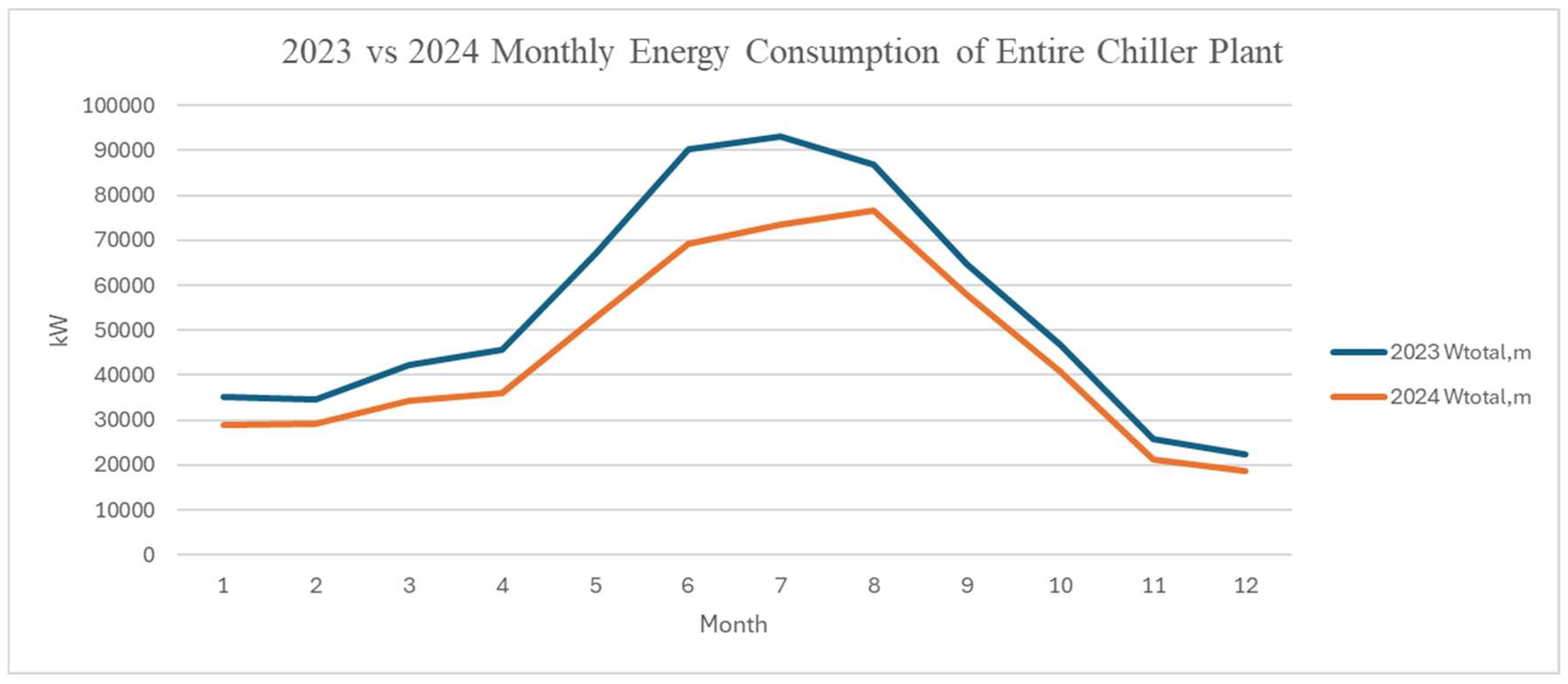

From the perspective of electricity consumption, the monthly electricity consumption (Wtotal,m) in 2024 showed a consistent reduction compared to 2023. This indicates a significant improvement in energy efficiency following the installation of the BMS. Specifically, the reduction in electricity consumption varied across months, ranging from 12% to 23.4% (calculated based on Re values). For instance, the largest reduction occurred in June (ΔW=21,132 kW), while the smallest reduction was observed in December (ΔW=3,669 kW).

Figure 2.

2023 vs 2024 Monthly Energy Consumption of Entire Chiller Plant.

Figure 2.

2023 vs 2024 Monthly Energy Consumption of Entire Chiller Plant.

4.1.3. Changes in Cooling Load

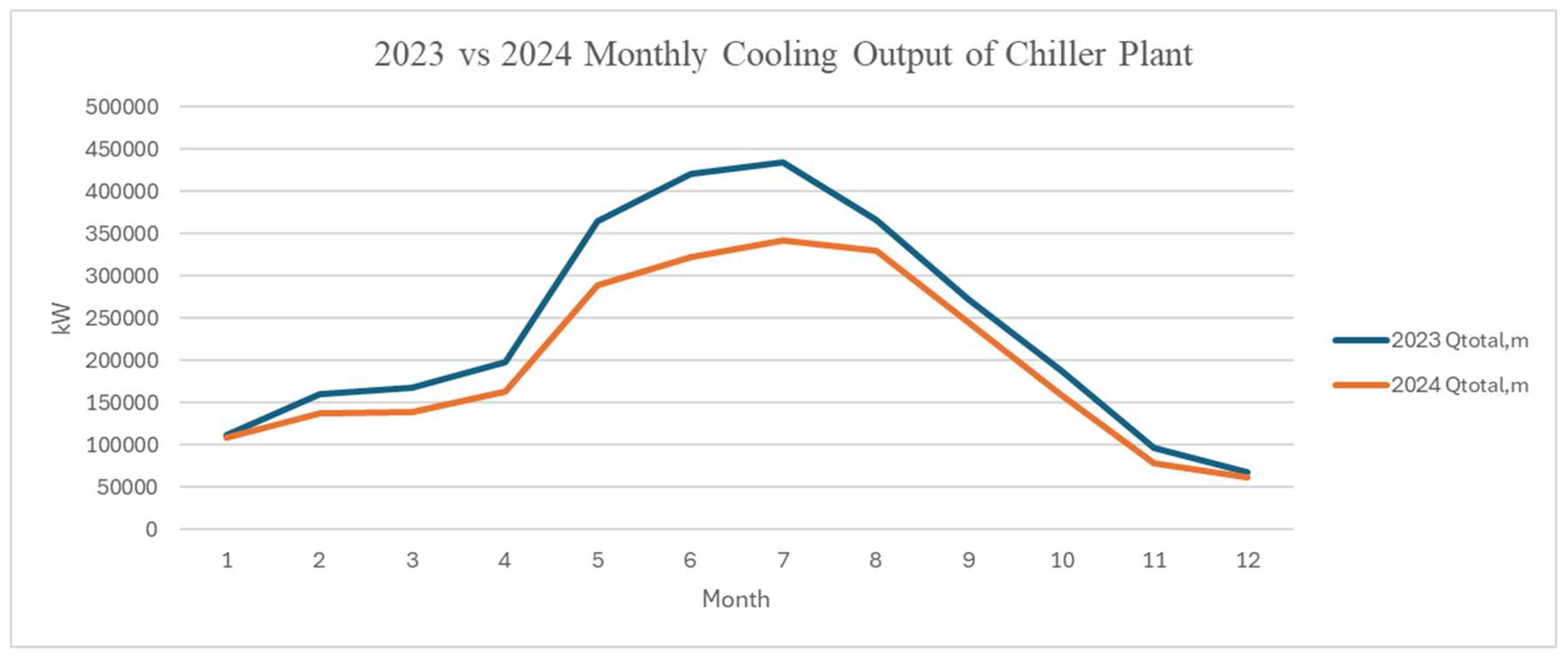

Aside from decreasing energy usage, the system showed the reduction in monthly cooling load (Qtotal,m) during 2024. This indicates that the BMS not only made the system more energy efficient, but it also optimized the cooling demand through the elimination of unnecessary loads. The minimum cooling load reduction occurred in January, with the decrease in cooling load from 111,877 kW down to 107,786 kW. The greatest drop in cooling load was seen in June, where the cooling load reduced from 420,849 kW down to 321,640 kW. It is most likely that the reduction is the result of the BMS fine-tuning the systems for smoother operations and the prevention of unnecessary overcooling, thereby maximizing overall efficiency.

Figure 3.

2023 vs 2024 Monthly Cooling Output of Chiller Plant.

Figure 3.

2023 vs 2024 Monthly Cooling Output of Chiller Plant.

4.1.4. Changes in System Efficiency (COP)

A detailed examination of the monthly Coefficient of Performance (CO Pₘ) reveals that system efficiency improved in most months of 2024, indicating enhanced energy performance of the chiller plant. For example, the COPₘ increased from 3.18 to 3.74 in January, and from 4.32 to 4.52 in April, reflecting a more efficient conversion of electrical energy into cooling output. However, in some months, the improvements were marginal—such as in June and July—or even slightly negative, as observed in October, where the COPₘ declined from 4.01 to 3.87. These findings indicate that, in general, the chiller system was more efficient under normal operating conditions in 2024, presumably aided by efficient evaporative cooling-based heat rejection methods. Variability in the efficiency of the system among different months can be explained as being influenced by external environmental conditions or varying load conditions. The COP is still an important and accepted method for assessing the operating efficiency of chillers under different demand conditions.

4.1.5. Energy Savings

ΔW is the monthly electricity savings, from 3,669 kW (December) to 21,132 kW (June), in terms of energy savings. Re, on the other hand, shows the ratio of electricity use between 2023 and 2024, from 0.766 (June) to 0.896 (September). Specifically, a lower Re value indicates more obvious energy savings. For instance, Re=0.766 in June suggests that the 2024 power use was only 76.6% of the 2023 one, resulting in 23.4% savings. On the other hand, a higher Re value indicates lower energy savings. For example, Re=0.896 in September indicates that the 2024 power use was 89.6% of the 2023 consumption, resulting in 10.4% energy savings.

4.1.6. Cost-Benefit Analysis

By comparing the power consumption and the related costs between the reference year 2023 and the year after the installation in 2024, the paper measures the energy and cost saving through the installation of the SC+BAS system. The electricity tariff rates applied in the analysis hereunder are derived from the non-residential electricity tariff schedule issued by CLP Power Hong Kong Limited, with charges per unit at 103.1 cents/kWh in 2023 and 106 cents/kWh in 2024, an increase in the cost for each unit by 2.8%.

The fuel adjustment charge, varying each month based on actual versus projected fuel expense differences, has been omitted from the electricity cost analysis. It has been omitted because it may be influenced by differences in timing, geographically, or in utility policies, that would bias the analysis.

Also left out is the energy-saving rebate, being offered only for actual metered consumption and not for estimated usage, in order for the comparison to be accurate and consistent.

Table 2 presents the outcomes of the energy and cost saving analysis. Detailed monthly calculations for the three stand-alone chillers for the two years are presented in

Table 3.

The rate of change of -17.6% is based on 2023 as a baseline. 2024 consumption at 2023 energy charge is $555,800 (i.e., 539,088.26#×1.031). Thus, actual cost savings is $118,875.54 (17.6% saved) (i.e., $674,675.54 −$555,800). Applying the greenhouse gas emissions intensity in 2024 of 0.53 kg CO2e/kWh, the carbon emission reduction is 61,109.64 kg CO2e (i.e., 115,301.21## kWh x 0.53 kg CO2e/kWh ), which is 61.11 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent in greenhouse gas emissions (t CO2e).

In short, the above analysis identifies an impressive annual cost saving of HKD $118,875, evidencing the organization’s focus on economic resilience as well as sustainable operations. At the same time, the 2024 energy use is complemented by an estimated 61.11 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent in greenhouse gas emissions. Both cost-saving and environmental performance represent combined requirements for holistic urban sustainability analysis and long-term strategy planning. The analysis identifies the imperative for further efforts in reducing emissions and green energy alternatives. As urban areas and industries transition toward decarbonization, organizations need to find balance between economic performance and environmental stewardship—meaningfully contributing toward overall sustainability objectives while reinforcing competitiveness in an increasingly green-conscious urban development model.

5. Discussion

5.1. Savings Through the Integration of SC+BAS

Since the 2024 installation of the SC+BAS system, both energy usage and the related costs decreased substantially. In particular, the annual power usage decreased 115,301.21 kWh, representing 17.6%, while actual cost saving totaled HKD 103,241.98, 15.3% less. When calculated based on the 2023 electricity rate, the cost saving would be HKD 118,875.54, which accounts for the same 17.6% reduction in energy usage. The difference reflects the effect of the 2.8% increase in the 2024 electricity rate; if the rate stayed the same, the cost saving would be even greater. The result proves the effectiveness in saving energy through the SC+BAS and its substantial contribution towards enhanced energy efficiency as well as lower operating expenses.

The significant 17.6% decrease in energy consumption noticed in an average urban shopping mall can be contributed to many important features and operational optimizations facilitated through the SC+BAS:

5.1.1. Advanced Monitoring and Control of Chiller Operations

One of the principal advantages of the SC+BAS is its capacity for detailed, real-time monitoring and control of chiller performance. Via the application of automated devices and smart control algorithms, including Trim/Respond logic, the system makes dynamic adjustments in setpoints in response to real-time feedback. This allows the chillers to respond optimally under conditions of varying loads, reducing unnecessary energy usage without impeding cooling performance.

5.1.2. Chilled Water Temperature Reset Methods

Temperature reset using chilled water is another important consideration. Dynamically manipulating chilled water temperature setpoints (CWP) through real-time data and predetermined optimization algorithms, the system minimizes compressor lift, notably in times of low cooling demand. This directly improves the coefficient of performance (COP) for the chillers, and overall system efficiency.

5.1.3. Variable Speed Drive (VSD) Technology Integration

The use of Variable Speed Drive (VSD) technology saves considerably in energy. In comparison with conventional constant-speed systems, VSDs enable motors in fans and pumps to vary their operating speeds in response to actual load conditions. This flexibility helps save power through efficient utilization, particularly under part-load conditions, reducing power usage overall.

5.1.4. Demand-Based Cooling Strategies

SC+BAS further accommodates demand-based cooling strategies. With real-time analysis of occupancy and thermal loads, the system can curtail cooling delivery in low-traffic and vacant spaces during off-peak periods. It saves energy through the targeted strategy that prevents unnecessary cooling in poorly occupied spaces, further reducing the energy wastage throughout the mall.

5.1.5. Improved Maintenance Procedures and Predictive Control

Apart from operational efficiency, the SC+BAS optimizes maintenance activities through predictive analytics. Using continuous monitoring of system performance, the system will detect the likelihood of equipment failure beforehand, allowing for predictive maintenance. This minimizes unexpected downtime, improves equipment longevity, and provides high operating efficiency consistently. The system can further distribute the load among multiple chillers such that the most efficient equipment will be reserved for partial-load operations.

In conclusion, the 17.6% energy saving measured is an outright consequence of the holistic and synergetic features of the SC+BAS, combining real-time monitoring, smart algorithms, dynamic setpoint control, VSD integration, load-responsive cooling, and upgraded monitoring and maintenance procedures. In combination, these features allow the chiller plant to maintain its efficiency in all operating conditions. The outcomes from the applied project clearly identify that SC+BAS systems can save significant energy, in particular if the system is optimized in such a manner that it dynamically adjusts in response to the real-time needs—maximizing the performance and contributing towards larger scale sustainability for urban commercial buildings.

5.2. Recommended Enhancement Initiatives

In pursuit of further enhancing the performance and efficiency of the chiller plant within the shopping mall, the following strategies are proposed:

5.2.1. Optimization of Chiller Sequencing and Load Balancing

Advanced sequencing control for the chillers can make it start, stop, and load rank the chillers in response to real-time cooling loads. It optimizes chiller usage, especially in partial loads, and minimizes the running of extra units. Dynamic load balancing through the BAS improves the performance of the system further by distributing the loads evenly, thereby eliminating overload and underutilization of the chillers.

While existing Trim/Respond logic accommodates simple start-stop control and load modulation, it mainly runs on fixed parameters and pre-programmed control procedures. This constrains its capacity for responding to uncertain future conditions and sophisticated scenarios. For instance, fixed scheduling for the activation of chillers may not be best suited in the case of varying cooling loads. To break beyond this constraint for deeper energy saving, the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) is suggested. In an AI-augmented system, the building thermal behaviour and actual operational data can be analyzed for chiller sequencing and load distribution optimization in real-time. In the pilot project carried out in the Hong Kong MTR Corporation, such AI-based predictive control realized an extra 8.7% annual energy saving through real-time optimization of the chiller operations—showcasing better performance in comparison with conventional rule-based approaches.

5.2.2. Implementation of Demand-Based Cooling Strategies

The BAS should be utilized further to enforce demand-based cooling through the modulation of chiller outputs with respect to real-time occupancy and local cooling requirements. Off-peak cooling in low-traffic areas or zones that remain vacant can be downsized using occupancy detectors or foot traffic analysis. The BAS should be combined with Variable Air Volume (VAV) systems to facilitate zonal cooling optimization for the distribution of cooling only where it is necessary. Such centralized cooling avoids wasting energy and supports smart building concepts for efficient HVAC operations.

5.2.3. Optimizing Chiller Plant Maintenance and Operation

A properly planned maintenance program is needed, according to the Electrical and Mechanical Services Department (EMSD) in its Best Practices for Operation and Maintenance Service. Preventing equipment failure induced by normal wear, neglect, and fatigue is contingent on conducting preventive maintenance. Keeping the chiller plant operating at its best efficiency and reducing unexpected repair expenses hinges on the replacement of worn parts prior to actual failure.

The shopping mall is not currently integrated with artificial intelligence. Faults in the chiller plant hence are only discovered after they occur, increasing the cost of repair and potentially leading to downtime. Preventative work is typically performed on a schedule, independent of the actual condition of the equipment, hence creating unnecessary work at times.

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and the incorporation with SC+BAS will assist in enhancing the quality and upkeep of chiller plants. Merging the two will assist in the development of predictive maintenance. AI identifies patterns for potential equipment failure utilizing real-time analysis from SC+BAS, such as temperature, pressure, and flow rates. It provides the benefit of undertaking the upkeep ahead of actual breakdown, hence decreasing the cost of repair and enhancing equipment lifespan.

In summary, the suggested improvement measures will enhance the energy efficiency of the chiller plant, increase system reliability, extend equipment life, and provide a better climate for the tenants and visitors. Moreover, the measures will maximize operational efficiency and save considerable costs, ensuring the overall sustainability and efficiency of the shopping mall.

6. Conclusion

The overall analysis of the SC+BAS deployed in the urban shopping mall offers an in-depth analysis of its effect on chiller energy efficiency and the resultant economic advantages. The analysis uncovered discernible changes in the energy usage characteristics and operating efficiency of the chiller plant after the installation of the BAS, necessitating an in-depth investigation of the performance of the system.

A comparative assessment of monthly energy usage and cooling production clearly identifies the Supervisory Control and Building Automation System (SC+BAS) as the best approach to maximize chiller operations. Significantly, in the months when cooling requirements were the highest, the energy usage was notably less, such that the chiller plant in 2024 showed a 17.6% decrease in usage as compared to 2023. At the same time, the overall Coefficient of Performance (COP) of the chillers increased in most months, reflecting greater operational efficiency. All these clearly prove the chiller plant performance in maximizing the cooling loads while reducing unnecessary usage of energy, thus contributing towards greater overall energy efficiency in the HVAC system. All these conform with conventional building performance optimization and sustainable design practices.

The cost-benefit analysis emphasizes the economic benefits accruing from the implementation of the SC+BAS. The annual electricity spending was reduced by 15.3%, presenting significant economic benefits for the shopping center. In defiance of the increase in electricity charges in 2024, the SC+BAS recorded major energy savings, resulting in net cost savings worth HKD 118,875.54. The figure reflects the economic feasibility and long-run economic returns from investing in advanced building automation systems. The recorded saving presents empirical proof for the implementation of the system as an approach towards attaining environmental and economic sustainability in the operation of commercial buildings.

In addition, the case study highlights the pivotal value of urban science for maximizing building performance in the complex framework of urban contexts. Utilizing data-driven insights together with advanced control systems, we can advance the design of smarter, more efficient urban infrastructure. The fruitful realization of the application of SC+BAS demonstrates an exemplary application of urban science concepts, promoting the minimization of energy usage and costs at the shopping mall. It provides an actionable framework for similar implementations in other urban environments, in compliance with the global goals for realizing smarter, more sustainable, and environmentally-stewardship-based urban environments. Future work need to address the scale and flexibility of such an application in varying building typologies and urban environments for maximizing related impact on urban sustainability.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to the building owner and Hang Lung Real Estate Agency Limited for their invaluable support in providing all necessary documents, drawings, and technical data related to the control panels and energy meters of the chiller plant. Their collaboration ensured access to the corresponding two-year electricity tariff in 2023 and 2024, which was essential for this analysis.

Abbreviations

| SC+ |

BAS Supervisory Control plus Building Automation System |

| COP |

Coefficient of Performance |

| VSD |

Variable Speed Drive |

| ANN |

Artificial Neural Network |

| HVAC |

Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CPC |

Chiller Plant Control |

| T/R |

Trim/Respond |

| VSD |

Variable Speed Drives |

References

- Van Roosmale, S. , Hellinckx, P., Meysman, J., Verbeke, S., & Audenaert, A. (2024). Building Automation and Control Systems for office Buildings: Technical Insights for Effective Facility Management - A Literature review. Journal of Building Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Kang, W. H. , Yoon, Y., Lee, J. H., Song, K. W., Chae, Y. T., & Lee, K. H. (2021). In-situ application of an ANN algorithm for optimized chilled and condenser water temperatures set-point during cooling operation. Energy and Buildings, 233,. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. , Zhou, S., Ding, Y., Moon Keun Kim, Bin Yang, Zhe Tian, & Liu, J. (2024). Exploring the comprehensive integration of artificial intelligence in optimizing HVAC system operations: A review and future outlook. In Results in Engineering [Journal-article]. [CrossRef]

- Yeon, S. H. , Yoon, Y., Kang, W. H., Lee, J. H., Song, K. W., Chae, Y. T., Choi, J. M., & Lee, K. H. (2023). Lower and upper threshold limit for artificial neural network based chilled and condenser water temperatures set-point control in a chilled water system. Energy Reports. [CrossRef]

- Suen, A. T. Y. , Ying, D. T. W., & Choy, C. T. L. (2022). Application of artificial intelligence (AI) control system on chiller plant at MTR station. T. L. ( 29(2), 90–97. [CrossRef]

- Fong, K. , Hanby, V., & Chow, T. (2005). HVAC system optimization for energy management by evolutionary programming. ( 38(3), 220–231. [CrossRef]

- Thu, K. , Saththasivam, J., Saha, B. B., Chua, K. J., Murthy, S. S., & Ng, K. C. (2017). Experimental investigation of a mechanical vapour compression chiller at elevated chilled water temperatures. Applied Thermal Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S. , Li, Z., Fan, D., He, R., Dai, X., & Li, Z. (2021). Chilled water temperature resetting using model-free reinforcement learning: Engineering application. In Energy & Buildings (Vol. 255, p. 111694). [CrossRef]

- Schibuola, L. , Scarpa, M., & Tambani, C. (2018b). Variable speed drive (VSD) technology applied to HVAC systems for energy saving: an experimental investigation. Energy Procedia. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. , Greenberg, S., Piette, M. A., Meier, A., & Fiegel, J. (2015). Data analysis and modeling of an all-variable speed water-cooled chiller plant. Proceedings of the ASHRAE Annual Conference, /: of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). https.

- Liu, Z. , Tan, H., Luo, D., Yu, G., Li, J., & Li, Z. (2017). Optimal chiller sequencing control in an office building considering the variation of chiller maximum cooling capacity. ( 140, 430–442. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S. , a, Zhou, S., Ding, Y., Kim, M. K., Yang, B., Tian, Z., & Liu, J. (2025). Exploring the comprehensive integration of artificial intelligence in optimizing HVAC system operations: A review and future outlook. Results in Engineering. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).